Abstract

This research provides an overview of the application and practices of cultural values and customary law in preventing and correcting violations of norms and regulations, i.e. criminal acts. A qualitative approach with deep interviews, focused group discussions, and situational observations was applied, and the data was analyzed using the thematic interpretation technique. It was discovered that Digalla helped to balance the socio-cultural structures of the Afars’ way of life. Some of the significant challenges that the Afar are facing include occasional disputes between statutory law, Islamic Sharia, customary law, and state-imposed law, difficulties faced by traditional courts in enforcing their decisions, differing opinions on whether and how to record and codify indigenous customary law, and the erosion of customary law principles and practices by the current generation. It is suggested that many the non-adversarial cultural values and customary law practices in penal or reform measures may offer models for possible replication within mainstream justice and penal systems of other social groups in the country in general.

1. Introduction

Despite decades of customary law practices and administrative incorporation, their implementations were neglected by the central state administration. The Afar people, like many other pastoral communities in Ethiopia and elsewhere in Africa, have legal systems and procedures to handle and peacefully resolve disputes (Ayana et al., Citation2012; Kassa, Citation2004). A custom is an accepted and followed norm of behaviour and corrective action practised by a group of people. Customary laws are employed to resolve disputes and promote reciprocal, mutual social and economic relationships. It involves rules and norms that were developed, modified and improved over a long period used to peacefully resolve disputes (Adom, Citation2016; Wagner & Sherwin, Citation2014).

This study has found that a good number of studies have been conducted on various aspects of Afar society. For instance, survival in arid areas (Said, Citation1996), marriage type practices and the roles in socio-economic development (Yesuf, Citation1999), Afar Ethnicity, tradition, continuity and socio-economic changes (Kassa, Citation2001), indigenous governance among the Southern Afar (Hassen, Citation2011), conflicts and alternative dispute resolution among Northern (Tafere Reda, Citation2011), a critical analysis of Issa-Afar violence (Gidey Alemu, Citation2018), resource and conflicts (Kassa, Citation2004), economic adaptation and competition for scarce resources, state interventions on pastoral land (Kassa, Citation2002), settlement patterns among pastorals along Awash Valley (Kassa, Citation2004), and regional dynamics of inter-ethnic conflicts among Afar-Somali (Mohammed, Citation2010). The Afar society has been and is still known for its values and practices of sharing and mutual reciprocity in every sphere of life interactions. This has been maintained through the strict societal-wide implementation of their customary law (maa’da), the youth group (fimma), which enforces corrective measures (digalla) decided by community leaders and elders. The most frequent methods for deciding local disputes in court and enforcing the law are known as customary law practices. How to mutually keep and protect crimes, very little attention has been given to the traditional mechanisms used by the Afar society. Before now, there has been a lack of understanding of the functions of customary law practices from the perspectives of social networking analysis in managing and governing societal relationships, correcting improper behavior, and upholding cultural values.

For what makes this work novel, there are several explanations. Combinations of various research methodologies and components were used to implement the study. The methodological preferences that enable the study to identify the primary link between the traditional communication system (dagu), cultural values and customary law practice (maa’da), and the pastoral community mood of social networks (affehina and tehaluf), traditional punishment (diigalla), social behavior (sharing and reciprocity habits), and seasonal mobility and resource use (faggee) are the factor that distinguishes this research work from others. First, from at least the perspective of traditional communication and social network, the culture of the studied society relied heavily on exchanging information in a detailed and coherent manner until it was mature and convincing to the recipients. Second, target social members studying the socio-cultural elements should have given thoughtful responses to the structured interview rather than non-social members. It fills in the knowledge gaps left by earlier studies on using customary law (maa’da) and refutes them. The roles play a crucial role in micro-level society and social structure, not only in resolving conflicts but also in crime prevention, facilitating and managing “social relationships,” and using a “social networking approach.” Thus, the results of a prior study found that the general customary law applications in the Afar pastoral community varied from clan to clan. The application of customary law, however, is consistent throughout clans. The “maa’da” customary law has been given numerous names for various reasons, including settlement patterns, traditional judge’s name representations, and the location of “maa’da” court sessions. However, its applications are the same across all clan groups. The methods and severity of punishing the offenders and the methods of compensating victims varied very significantly. The quantity of animals owned by a particular clan and the state of the available livelihood are factors. It is currently an important discovery that helps to reimage the misguided perceptions of the sociocultural practices of pastoral communities in the Afar from various angles.

At this juncture, the phenomenological research assumption was applied more to assess pre-existing conditions in social relationships and customary law practices. Hence, this study aimed to investigate Afar society’s customary law or cultural mechanisms of crime prevention and the core links between peaceful regulations of societal relationships and practices of cultural values.

1.1. Significant of the study

Most of the literature that has been written about social networks has concentrated on urban and organizational levels. The study does, however, show how social networking is crucial for rural and traditional societies in facilitating and preventing crimes and deviant behavior and perpetuating social interactions among community members at the individual, social group, and societal levels. The study’s findings will, therefore, be used as additional inputs and sources of references for the literature that already exists in the fields of society, sociology, cultural studies, criminology, social work, community mobilization and cohesion, social interactions, traditional communications, and, above all, indigenous knowledge studies.

Although the state constitutional amendments acknowledged in the paper that customary law practices successfully resolve local disputes, there has yet to be a formalized effort to incorporate these practices and their contents into the current legal system. Legal professionals may incorporate the proposed customary law’s contents and procedures into their interactions with community elders and traditional judges and the court system’s use of current legal practices. For this reason, the quick customary law court decision will help the modern justice system, which has suffered from a drawn-out process in determining how to punish offenders and compensate victims. This study will, therefore, urge policymakers, the government, social groups, and other interested parties to reassess the socio-cultural traits of the target society and suggest potential actions with a new model that serves as how to successfully incorporate the common law within that state structure modern legal procedures.

2. Methods

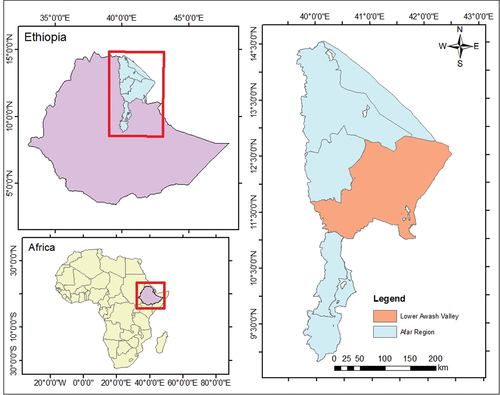

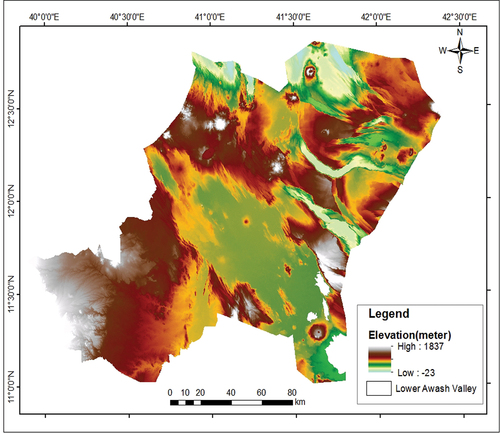

2.1. Study area description

Afar is located in northeast Ethiopia, bordering Eritrea and Djibouti. It covers 150,000 km2 and is divided into clans that share the same language, religion, tradition, culture, decision-making authority, and customary law. Clans serve as a core for administration and collaboration to conduct social activities, even if clan kinship is strong (ANRS, Citation2022)

2.2. Approach and philosophy

The qualitative research method was used to generate the subjective and intersubjective meaning of the experience of social interactions among the Afar people. The study adopted a phenomenological inquiry to explore the phenomenon of clan group networks, customary law practices, the nature of social relations and preventing anti-social behaviours and acts in the Afar society. In general, the research was conducted in both rural and urban Afar people-inhabited areas. This paved the way for openness, and the participants showed their consent to the investigation, which also helped them freely interact with the researcher. Individual interviews were the best methodology for gathering data, as the researcher spent more time with the participants at their homes during the night. However, conducting focused group discussions (FGD) was difficult due to the harsh, hot climate, high and condensed atmospheric pressure, and the mobile nature of the people.

In line with the definitions in the discussion section, this study employed qualitative methodology through extensive focus group discussions, observations, and in-depth interviews about social relationships, social or group networks, and customary law practices based on interview participants and focus group discussants information. The overall process involved gathering initial data from network assumptions with defined geographic locations, social communication and economic reciprocity systems, and settlement and mobility patterns, showing the network flow cross-checking it with the collected data, and then communicating with the network after the initial communication occurred.

2.3. Design

This study applied a qualitative ethnographic study design to select clan groups, members, and other study participants. This design is best suited to studies to determine the prevalence of a phenomenon, situation, problem, attitude, or issue.

2.4. Sampling procedures

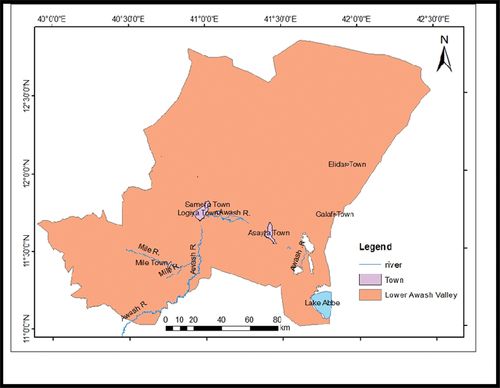

A purposive sampling technique was used to gather the necessary data from target sampling areas based on pre-selected criteria. The sample size was determined by resources and objectives. Major Afar clans and sub-clans selected were those found along escarpments and grazing zones. Thus, Awsi-Rasu (zone 1) was selected based on clan groups’ geographical proximity and settlement pattern to Lower Awash Valley, where Afambo, Asayita, Dubti, Elidar, Mille, and Samara-Logia were the major research areas.

In a similar vein, key informants and focused group discussion participants were identified based on pre-selection criteria such as duration, proximity, acceptance, communication skills, participation levels, managerial ability, and work experiences. Of course, while selecting study participants, there is always the danger of bias entering into this type of sampling technique (Cresswell, Citation2014). However, in this case, enormous care was being taken to avoid bias and make the results obtained from an analysis of a deliberately selected sample tolerably reliable.

Accordingly, Wereda (district) officials, youths, women, religious leaders, social experts, community workers, community members, community leaders, local government, justice officers, pastoral livelihood, climate, livestock, culture, tourism, and information bureau representatives were chosen for key informant interviews and focus group discussants. Study participants were given equal chances to be chosen from the Awsi-Rasu (Zone 1) settlement and grazing zone for each research setting area. Extensive efforts were made to compile trustworthy information using focused group discussions and in-depth interviewing techniques. Three field visits were made; the first two were for a preliminary pilot study to determine how to communicate with participants in the research. Through these courses of time, 96 participants with three rounds of field study were contacted.

2.5. Data collection tool

Qualitative data-gathering methods, such as key informant interviews (KII), focused group discussions (FGD), and situational observation approaches, were used to collect primary data. Furthermore, the nature of this research was exploratory and open-ended, and it needed qualitative research that “is much more subjective than quantitative research and uses very different methods of collecting information, mainly individual, in-depth interviews and focus groups” (Danielle, Citation2007, p. 419).

Focus group discussions (FGDs) create a space for participants to clarify their views and understandings from different perspectives on social relations, customary law practices, and cultural values and norms (Cresswell, Citation2014). In Lower Awash Valley, one FGD section is discussed in each of the six areas purposefully chosen in agreement with clan leaders, government office experts, community members, youth leaders, and administration workers to indicate the status of social interactions, the practices of customary law and implementations of cultural values on the ground, and crime challenges, prevention, and control systems. A small number of female but mostly male study participants were aged above 23 years. Purposive sampling was again applied to choose FGD participants. The participant number in a group is managed within a range of 8–12. This meets the ideal size to exploit mature and multiple discussions (Aspers, Citation2009). Discussion item lists were primarily structured in English and transcribed into Amharic and Afar (Afar AF) local languages. The FGDs were held by the main researcher with the support of an interpreter. Except for two remote areas in Asaita and Afambo, which were discussed only in Afar AF with the interpreter changing the ideas into Amharic to support the researcher’s continued discussion with the participants, the discussions were conducted both in Afar AF and Amharic local languages. All discussions at the six research sites were tape-recorded and later changed following each section.

Key informant interviews (KIIs) facilitate the acquisition of primary data sources give an in-depth understanding of the notion and settle in-depth explanations that secure the validity, reliability and generalizability of the research by applying various methods through examining and articulating individual concerns (Cresswell, Citation2014). Thus, this study utilized open-ended approaches to respond flexibly and transfer into further explanation and discussion. Local government, gender, Pastoral livelihoods, social affairs, and justice office representatives; and clan members, clan heads, and district administrators were key informants. Of all, 8 community and clan members and the other 2 government officials were females; the rest were male key informant participants. Informants were selected purposely, based on such pre-selected criteria as their experience and knowledge of social relationships, cultural values and customary law practices, social ties, acceptance, public participation, and clan group linkages. In this KII, the study aimed to address the research objective of exploring the custom of preventing crimes among Afar pastorals along the Lower Awash Valley through socio-cultural values and customary law practices. Using the purposive sampling technique, well-informed, experienced and knowledgeable informants were accessed. All key informants were communicated in Amharic language and even assisted the researcher in explaining issues in comparison with Afar af language so as not to miss the meanings and concepts of raised issues in detail. Accordingly, a total of 22 interviews, three informants for each research site except six for logya-samara and four for Asaita, were conducted. Arranging the key informant guides to articulate the discussion, 16 interviews took place in the key informant’s respective villages (home compounds) and the rest of the regional and district bureaus. All interviews were tape-recorded and interpreted from Amharic and Afar af to English languages.

2.6. Data analysis method

The qualitative method of data analysis was established on primary sources to triangulate the arguments provided in the discussion. The logic is that “Qualitative research is collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data by observing what people do and say” (Trochim, Citation2005). This study applied a thematic interpretation approach for analyzing tape-recorded audio files, texts and different valuable materials obtained from FGDs, KII and researchers’ situational observations as well as field visit minutes and notices. Then, meanings from participants’ responses were interpreted, triangulated and analyzed based on the themes that were prepared in groups and sub-groups.

Furthermore, based on interviewees’ assessments of the relative strengths of the various flows and relationships important for developing, articulating, and demonstrating socio-cultural values and principles, qualitatively grounded network analysis and assumptions were made. As a result, the process involved gathering initial data from network assumptions with defined geographic locations, social communication and economic reciprocity, and settlement patterns. This process showed the network flow cross-checked with the collected data and then articulated with the network after the initial communication occurred.

3. Results

3.1. The upholding and use of cultural values principles, and practices: as Afar society’s engines for continuous regulations and management of harmonious social relationships

Clans have different procedures and principles for managing social interactions, accessing and utilizing resource usage, and preventing and managing disputes. One of the principles is to obey cultural values and practices. The cultural values of Afar’s people are scenarios of mutual trust, support, reciprocity, and cooperation. These practices can manifest themselves in dispute mediation, herd management, condolences, weddings, births, public prayer, development work, security, managing and protecting environments, participating and sharing in rituals and collective action and social belongingness. The unwritten customary law “maa’da” calls up on and demands practices, and any act of action or lack of obedience may result in a series of penalties. Thus, among the different cultural practices, some are presented as follows:

3.1.1. Ibbinitina

Ibbnitina is one of the cultural values Afar society duly performs at times of inviting guests. The main goal is to respect guests and provide what is necessary. Regarding this, one of the Dahimela clan members outlines:

An Afar pastoralist is not required to bring meals or other relevant products while travelling a long distance away from home. However, if home members are present, the traveller has the right to obtain lodging under Maa’da customary law, which the host would be delighted to invite as the host may visit other locations. [C1, male-3, 52 years old, Asaita area]

The provision of hospitality and respect to guests is a basic socio-cultural value of Afar society. An appeal to the Maa’da court can come from the guest himself or any members of the host community if someone is found guilty while treating the guest. He or she will be punished if someone is found guilty of showing disrespect and devaluing hospitality to a guest. Hence, the maa’da customary law obligates cultural values in society to ensure that social relationships and clan group networks function properly. Particularly, almost all elders from all research sites reflect identically, but one of the FGD participants outlined specifically that:

The “Ibbnitina” cultural values and customs allow people to form friendships, become close relatives, and develop mutual trust. This cultural value also serves to protect and control conflicts. Respecting others is essential for maintaining accommodations and building relationships, while also acting as a bridge to contain tensions and preserve peace. [FGD6, male-2, 42 years old, Dubti area]

3.1.2. Harrayna Kurra

Harrayna Kurra is one of the cultural values that obliges clan members to social and economic support one another during marriage, birth and funerals as well as public holiday collective participation. As far as the responses are concerned, one of the interviewees firmly replied:

During marriage ceremonies, brides receive gifts that benefit their new home, and if they are financially disadvantaged, special assistance is provided. In times of death, gifts are given to express condolences. Cultural practices contribute to preserving peace and support among social groups, and if someone commits harm or causes conflict, his/her contributions and support during “Harrayna Kurra” will be considered and the level of penalty minimized. [KI9, male-4, pastoral livelihood experts, 59 years old, Logya-Samara area]

3.1.3. Edebbonta

The order of Edebbonta deals with assisting those who have lost their animals and household properties due to natural or human-made disasters. It requires clan members in particular and society at large to provide as much immediate support as possible to victims. Regarding this, one of the FGD participants firmly states that:

Clan social organizations are the primary means of support for Afar pastoralists, as no one is alone in the networks of clan groupings. Victims receive assistance from their clan members through collective responsibility initiatives, such as donations to replace lost goods. They undergo rehabilitation as long as the facility is in operation and may go without food, assistance, or support for a short period. [FGD6, male-7, 38 years old, Dubti area]

3.1.4. Aliginu

Aliginu requires each clan member and weeding participant to provide support and preserve societal connections along with ceremonial activities. If so, a male bridegroom is referred to as Aligee, while a female bridegroom is referred to as Aligeyta. Regarding this, one of the key respondents described the scenario:

To preserve solid connections, it raises the household for friendship, and the role of bridegrooms can be considered a fundamental basis for building a peaceful family. During the wedding, all clan members pitch in to help as much as they can with their efforts. For instance, all needed cattle, livestock, or other gifts will be collected before the ceremony, which is called “Digib Harra”. [KI4, male-1, 63 years old, Asaita area]

Furthermore, one of the members of the Harela clan stated the position and responsibilities of being a bridegroom:

The role of the bridegroom is essential for building strong marriage relationships, as they are the closest friends from both sides of the marriage and are the first to be informed, discuss, and resolve the problem when a female couple experiences abuse, neglect, damage, or even confrontation. They, the groomsman or bride of the groom, are more than simply a personal connection in a distant pastoral community. [C2, male-4, 44 years old, Asaita area]

3.1.5. Mugainna

Mugainna is a ritual held to establish friendship recruiting with the most preferred person or individual. This is done by giving the newborn baby’s first name to symbolize a close relationship with a chosen someone. In Dagu conversations, the communicators specify with whom the family wishes to have a relationship while naming their infant using someone else’s name. As one of the FGD participants explains the process:

This acts as a “symbol” or depiction of the person’s conduct, personality, and other statuses. The procedure for naming a child is to say, “I consider my baby using your name based on the grounds and degrees of your character”. For a family to connect with him and use his name, he must be of excellent character, ability, knowledge, and service to society and the wider world. Thus, the chosen person will be invited and food will be served in reciprocity as a sign of respect and being the chosen one. [FGD4, male-2, 45 years old, Mile Area]

As far as the importance of Mugainna relationships in enhancing different relations among the chosen persons’ family members is concerned, the member of the Arapta Asabakeri clan outlined that:

This relationship can boost the number of interactions between social groups, such as if a family names their children in a way that represents the names of ten other families. This can be used to manage conflicts in these ten households. Because giving room for discrepancies could be seen as improper and unethical. If the difference is significant, close conciliation and resolution should be offered before it gets worse. [C5, male-1, 43 years old, Eli’dar area]

3.1.6. Onee Ore

The Onee Ore cultural practice exemplifies giving water before it begins to lactate to a newborn baby by a chosen person who is preferred to maintain relationships. The water is prepared when a mother is ready to give birth, and dates, honey, or milk are used as alternative inputs. Regarding how social relations through onee ore are accomplished, the members of the Hadermo clan stated the situation:

In this context, social relationships are accomplished based on three perspectives: to commemorate a welcome notification for a bay, a wish to have and develop good behaviour, character, and manners, and to name a “symbolic” person. [C4, male-1, 49 years old, Mille area]

3.1.7. Frangainna or Araginnu

Frangainna refers to activities intended to create or establish strong social relationships with members of broader clans or supra-clan units. It is argued that, hence, the family-to-family-based relationship begins within the formal interaction of Frangainna. The family prepares to establish relationships with non-family members. After choosing the one who is supposed to be a relative, the baby is helped to sit at the chosen back. The person chosen to become a relative is expected to carry out certain responsibilities. One informant described the ritual event and activities in the Frangainna ritual as follows:

Frangaainna is the action by which, for the first time, a baby is allowed to move his or her legs to the left and right and is carried on the back of the caregiver. This allows the baby to grow, be supported by both families, be called “Son of Frangaainna,” and be called “Arguu” instead of their given name. This has economic benefits for the baby, as it receives a gift from the chosen relative, like a goat, cattle, sheep, or camel. [KI15, male-2, 61 years old, Mille area]

3.1.8. Nonegelta or Negeltinu

Nonegelta refers to the mother-daughter relationships. It is expected that they interact with each other in a mutually respectful and cooperative manner. If they enter into disputes or disagreements, they are expected to peacefully resolve them without the involvement of family members. At this juncture, one of the pastoral livelihood experts exemplifies the continuity as follows:

The most important details are that during a relief assistance distribution programme, a woman received 50 kg/s of wheat flour and distributed it to four other women. However, those living in town are disregarding these cultural values, either keeping their interests or not contributing to what is expected. This attitude has been prevailing in this area as well as in other areas of the country. (KI6, male, 3–65 years old, Asaita area)

3.1.9. Aalla

Aalla or Hindda refers to a relationship created between individuals to establish closer friendship. The process is initiated by an individual asking another individual to become a closer friend. The presence of witnesses is mandatory to ensure clear and free future interactions.

3.1.10. Affehina

The Afars have a patrilineal kinship system. They also practice patrilineal clan-to-clan marriage along with other marriage systems. Both these supports equally participate, share or reciprocate the formation of social networks and interactions between members of different (related) clans. This networking relationship is called Affehina. A stem of affiliations and cross-cousin marriage determines clan groups’ networks and members’ social relationships. According to one of the interviewees,

Affehina is a social network established among two or more clan groups out of blood-line relatives’ cases. In Affehina, marriage is forbidden due to the relationship being considered a bloodline relationship. Close interactions, mutual trust, respect, rehabilitation, and other connectivity are respected and expected more from both sides. This interaction may not support Burra, Dahala, and Kedoo, but on an individual level, the relationship is very strong. This would strengthen clan groups’ networks as well. [C1, male-1, 55 years old, Afambo area]

As representatives of their respective clans, clan heads play important roles in the administration of economic reciprocities and in resolving disputes between clan groups and members, as well as other social groups. Among FGD participants, one of them stated the overall notions as:

The strength of the established relationship between individuals is measured by the level of interactions between members including the ability to share a broader set of information sources. This provides safety for individual members of families moving different territories in search of water, pasture land, trade exchange and other activities. [FGD1, male-4, 30 years old, Logya area]

3.1.11. Tehaluf

Tehaluf refers to a form of social connection or network reached to stand together at all times as one strong clan. Such relations are not hampered by temporary disagreements on certain issues such as affinal ties facilitate the practice of supporting each other in times of territorial and border disagreements. Regarding this, one of the interviewees expressed its aim as:

Tehaluf networking aims to withstand, defend, and protect if one of the clan groups faces an attack, mainly in cases of territorial or border claims. Although each clan administered on behalf commonly acts to fulfil the collective accountability, they practice their clan structure and the foundations of the establishment. Thus, all acts are under the rule of Tehaluf. For instance, “Dibni” and “Woima”, “Dahimela” and “Segento”, “Geleela” and “Kebrito,” and other clan groups can exemplify such practices. [KI3, male-3, 66 years old, Afambo area]

3.2. Customary laws of ‘Maa’da’, ‘afree’, and ‘dintoo’: meanings and functions

The traditional customary law consists of two significant elements, namely Maa’da or Afree (traditional law) and Dintoo. They guide or administer social interactions, economic reciprocities, mutual trust, norms and regulations, and practices of the Afar community. Maa’da refers to the rules regulations and procedures accepted by the majority of the Afar community members. The term Afree too is preferred to the maa’da.

Dintoo, on the other hand, refers to the organizational structure and method of working with or interacting with non-Afar people. This governs how social interactions, living together norms, rules of agreement, and guiding principles are administered as well. An FGD participant described the reason:

As a result, the Dintoo has controlled and provided for agreements, prerequisites, guidelines, and others, from individuals to the greater society. Along with Maa’da, the customary law head, “Maa’da Abobti”, seems to control the social structures of the community, from the lower hierarchy nuclear family unit (Burra) to the higher, the Sultan. Because of this, Maa’da Abba is viewed as a legislative body in charge of overseeing the upper echelons of each social organization. [FGD5, male-6, 47 years old, Eli’dar area]

The Afree legislation governs socio-economic relations, while Adan’le sets the principles, and procedures manages regulations and guides how Afar people interact with non-Afar relatives and other social members. One of the study participants described this as follows:

Maa’da law serves two purposes: Afree, which governs all socioeconomic interactions among Afars, and Adan’le, which administers and follows economic exchanges and other social interactions or communications with non-Afars. Adan’le refers mainly to social and economic interactions between Afar and non-Afar individuals or communities. [KI11, male-2, Justice Bureau head, 48 years old, Logya-Samara area]

According to the most recent information acquired from study participants, study documents and the regional justice bureau, the implementation of maa’da rules and regulations varies from place to place. One of the study participants explained this as follows:

Maa’da customary law in Afar land varies in type and kind of punishment depending on the available natural resources and environmental conditions. There are five customary law categories called “Burr’ili maa’da”, “Budiito maa’da,” “Afaakee’ekk- maa’da”, “Bedooyta maa’da”, and “Deebnek Waaaeeiimih maa’da”, but they have functioned as alternatives to serve society based on their settlement patterns. [KI11, male-2, Justice Bureau head, 48 years old, Logya-samara area]

There are cases in which disputes are resolved without using the elder’s tribunal, i.e. Meblo. Disputes between members of families, or extended family are not taken to the elders gathering or tribunal for resolution. Such cases, but, are handled in minor or non-formal dispute resolution and resolved by one of the disputants. These cultural values have emanated from different philosophical beliefs:

1) Members of the same clan, Fiimma, Affehina, or Negeltinu, are considered as one relative, 2) the primary objective of establishing the clan “fiaqq” examines decision enforcement with organizations and other institutions. Such intra/inter-clan or family networks prevent disputes and defend and protect members from harm and external threats. Thus, it is believed that “without controlling internal disputes and creating internal unity, it is not possible to defend the group and its property from external adversaries”. [FGD3, male-8, 39 years old, Logya-Samara area]

3.3. Preventing norm violation and disputes

Clan members and elders collectively look together to prevent violation of norms and perpetrations using the Fiimma institution. Collective activities are the best attributes of both clan groups and members. According to one of the key informants,

Individuals and groups strive for effective social relations, such as protecting against theft, fighting, breaking rules, and defying cultural conventions. It is because these factors could lead to eroding trust between relatives and turning down offers of cooperation and assistance. [KI15, male-2, 61 years old, Mille area]

Furthermore, some group discussants and key informants raised their concerns that:

The traditional legal system of the Afar seems to be neglected or is being eroded through the adoption of a new legal system and urbanization. The importance of cultural values has not yet been well supported by the contemporary administration systems of some clan groups themselves. [FGD3, male-4, 41 years old, Logya-Samara area]

And support the above claims that:

Individual members’ struggles to cover many socio-economic benefits have been identified as very weak. Clan member’s collective accountability for wrongs committed by individual members makes its progress, to some extent, sluggish. [FGD6, male-6, 38 years old, Dubti area]

But others replied that the strongest side of the social relationship process is:

The Afar people are known for their unique cultural practices and values that are linked to promoting social interactions, such as the practices of sharing, reciprocities, and preventing anti-social behaviours. [KI6, male-3, 65 years old, Asaita area]

The Afar societies promote clan groups’ social and economic networks along with procedures that help to deter or prevent anti-social behaviour or violations of societal norms and rules. When someone violates or breaks rules, a thorough investigation is carried out before corrective measures are taken.

The main factor that frequently influenced the process of inter-clan peaceful relations and cooperation was and still is livestock theft committed by individuals or a group of youths. Livestock theft for the raid is a “crime” and affects established peaceful inter-clan relations and leads to insecurity. Such incidents result in causing insecurity to the entire clan group. However, immediate corrective measures are taken by clan heads and elders of the clans concerned. Elders of the perpetrator individuals and victims’ clans or it may alternatively be handled by a third party (clan) elders, for the cost of withholding and resolving the cause peacefully while resulting in perpetual conflicts and insecurity for all. Hence, in thorough investigation of the case is conducted; and the clan of the perpetrator of the theft crime is penalized or asked to compensate the victim’s clan. One of the study participants described the process as follows:

The clan head and elders instruct every clan member to find out the lost or stolen livestock and the raiders, and thefts. In other words, all clan members are informed (by dagu) about the stolen livestock and take collective responsibility for finding and returning the animals. [C1, male-4, 46 years old, Afambo-Eibno area]

The clan under observation will identify the suspected person (theft). Following this, the clan heads (elders) and Fimma follow up on the stolen animals. Doing this is the responsibility of all clan members.

Megloo is a method of investigation that requires the perpetrator and his clan members to seek protection from another clan group, called Eissie. If the suspect escapes without any guarantee of protection, his clan members must provide a limited or bound period. This reveals collective clan responsibility and accountability. Regarding this, one of the key informants expressed the case as follows:

The importance of remaining under protection as a suspected clan is to be free from revenge and control civil conflicts. The protector (Eissie) is responsible for accepting the crime and being respectful of the rule of law to ensure that no other dangerous action happens to the protected clan members. [KI11, male-2, 48 years old, Logya-Samara area]

The Eissie notified Widal (the clan under its preservation) that the suspect had been apprehended, respecting Maa’da law and the people. The head of Widal stated that Eissie had been notified. Then, the Maa’da court, with “Maa’da abobti” (judges), sees the cases to bring peace among the conflicting groups. Two alternatives have been identified for the peace talks and agreement process: an appeal is provided to the court to handle the case of the suspect by the victim’s family, or permission is given to fulfil the family interest. The same problem committed by the suspects’ clan members could lead to the same appeal being fulfilled, leading to further conflicts. This procedure is not always accepted.

The victim’s family can appeal for revenge against the suspected, but it may not be accepted if they bring similar cases against other clan members. This procedure is well-known and legally binding, but it serves no purpose other than to exacerbate conflict. [KI11, male-2, 48 years old, Logya-Samara area]

The second option is to take the matter to the court of Maa’da customary law, which can lead to a quick resolution of the conflict or payment of compensation. The guardian clan (Eissi) vigorously attempts to resolve either option, as one of the key respondents explained:

The “maa’da” customary law court is preferred by most clan members for it is not alone cost-effective and restores relationships. It is manipulated by clan leaders and cases will be seen by “Makaban” elders. If agreed upon, the victim’s family will receive compensation and the relationship will continue as before. The compensation will be paid based on the collective contributions of all clan members. [KI7, female-6, Logya-Samara area, 31 years old]

3.4. Traditional punishments and compensations

This study examined the use of penalty (Diigalla) and traditional Afar tribunal to control crime, deviation from customary practices, and social interactions in Maa’da law court practices. Punishments were identified to outline Maa’da law court practices, which are based on memories of previous decisions and knowledge of the Maa’da law.

Dorroiee is a type of punishment that involves a simple request for “pardon”, such as “please consider my mistakes,” and moral punishment. It applies when individuals or groups disagree, disregarding others’ identities, economic status, defamation, and other related cases. If the victim accepts the “sorry” request, the case will be closed.

Sillallo is a type of punishment that involves providing food in exchange for punishment. The one who is going to be punished will mobilize some of his kin collect food from the social group and invite them with provisions of prepared foods. This type of punishment is usually performed by Fiimma groups.

Ereena-Seeie-Diigalla is a punishment that applies to punished individuals who slough off the animal they love. The animal to be slaughtered is selected by the court clan councils (Makaban), not by the punished individuals.

Lahii Diigalla is a punishment paid for with animal compensation, based on the type and character of the crime committed.

Arrawa Diigalla is a punishment that involves tightening both hands and turning to the backside with the thread of the punishment until the suspect accepts the committed wrongdoings. According to one of the interviewees,

This kind of punishment has not been widely implemented these days. But in previous times, it was one of the best punishment types that were used to correct deviant behaviours and those who committed stern crimes. [KI14, male, 1–54 years old, Mille area]

Mudllino Diigalla is a punishment to pay compensation to the harmed or victimized individual through the transfer of the costs of treatments of the harmed that is survival treatment expenses, food, and other necessities until he/she recovers from the injury. However, some claimed that Mudllino was not considered a punishment. At times of FGD, one of the participants described the cases:

The punishment does not take into account the costs of medical treatment, which have a high economic impact, leading to a lack of financial resources for those who commit crimes. [FGD3, male-8, 39 years old, Logya-Samara area]

Just considering its cultural importance, a key informant states:

Anyway, this punishment has become a significant factor in bringing peace to social interaction, as it has reduced the financial costs of social interaction. [KI21, male-2, 58 years old, Dubti area]

Habtii Diigalla is a punishment sustained by clan membership. It involves confiscating the right to clan membership, called looyna (clan protection). This is an inflexible punishment because the person has passed through different types of punishment before, and if no progress has been shown, this punishment will be applied. Most key informants agreed on how difficult this type of punishment is, and one more elaborated on it:

At the time of punishment, the clan head informs the member that he or she is no longer a member of the clan and has duly confiscated his or her clan protection rights. As to my experiences, some argue that this action is equivalent to forcing someone to flee, but others firmly state that it is a practice to keep society’s social interaction going in one way or another. [KI22, male-3, 52 years old, Dubti area]

The maa’da established various forms of penalty measures to control and manage corrective measures that prevent criminal and deviant behaviour, which are seen with thoughtful care, clear arguments, and sound decision-making abilities. This is explained as follows:

Community members appeal to the court to respect the rule of customary law when a disagreement or conflict arises based on previous socio-economic interactions, even if previous decisions have prevailed in peace. [KI11, male-2, 48 years old, Logya-Samara area]

Vengeance is widely accepted and ordered when a murderer disappears but must be accepted by the criminal’s family and relatives. Punishment must not be too late, as compensations and punishments have no value when it is too late. Key informants responded the current phenomenon paves the way for exacerbating various factors. Regarding these, one of the key informants firmly states the challenges as:

The sharing habits of Afar people have been resistant to the phenomenon, but it has harmed their socio-economic status. People with poor economic income prefer to hide from social interaction networks, suggesting that the phenomenon creates challenges but not the social relation status itself. [KI12, male-5, pastoral range land expert 36 years old, Logya-samara]

3.5. Challenges to customary laws and cultural values practices

The customary rules, regulations and legal systems of pastoral peoples were and still are legally recognized and protected. Afar’s law is distinct in several respects due to its nature, scope, and differences from other customary rules. The Afar people’s determination to preserve their way of life is demonstrated by the fact that some components of this legislation have persisted despite widespread discrimination against its implications. The challenges are:

Certain aspects have persisted in preventing maa’da from being practised; mostly political interventions, internal conflicts and instability are being eroded due to developments over which the Afar Pastorals have had little or no control. [KI10, male-3, 49 years old, Logya-Samara]

Political marginalization, expropriation of common lands, rapid economic integration, disruption of social cohesion, and domination of clan heads have harmed Afar maa’da. At this point, one of the interviewees outlines the fact that:

Customary practices about land and natural resources are strongest in cases where a strong tradition recognizes customary land rights. The land is essential for Afar’s culture, but customary rules on the allocation and use of land have faced serious challenges and are at risk of being eroded. [KI9, male-4, 59 years old, Logya-Samara area]

The people were exposed to assimilation, which threatened the integrity of their customary laws and institutions. It is a recent phenomenon that, as one of the interviewees indicated:

The political partition of Afar peoples’ homelands and territories without their consent has weakened their political, social, and cultural integrity and affected customary law, such as the separation of Eritrea from Ethiopia and the recent internal conflict. [FGD2, male-3, 42 years old, Asaita area]

Furthermore, how in danger the customary law practices are:

The erosion of certain socio-cultural and religious practices, such as the observance of marriage rituals and ceremonies, is happening even in some urban areas, where females are exposed to urban life and begin to choose their life preferences (KI7, female-6, Logya-Samara area, 31 years old). As one of the FGD participants explained the situation:

Customary law has been eroded by both external and internal factors, such as conflicts between customary law and modern law, difficulties in enforcing decisions, insufficient efforts to codify indigenous laws, and the generational gap in accessing traditional customs and cultural norms. [FGD4, male, 1:39 years old, Mille area]

4. Discussion

4.1. Social network theory and social network analysis: concepts and definitions

The current state of social network theory has been influenced by many research traditions. Several studies looked at the impact of social networks on the interactions between parents and their kids (Lois, Citation2016), including social networks and fertility (Bernardi & Klärner, Citation2014), social networks related to the science of social work (Rice & Yoshioka-Maxwell, Citation2015), social networks in areas of gender roles (Ma, Citation2022), and social network analyses used to find patterns in social networks. Other researchers have also concentrated on figuring out what influences the structural balances of network relationships and what other societal barriers play in these processes.

The importance of interpersonal relationships and interaction is emphasised by the social network theory. Numerous social science study fields, including criminology, anthropology, business, psychology, and sociology, have made extensive use of it. The definition may alter depending on how the social network is viewed. In close relationships where significant others can impose sanctions, social networks may serve as a platform for the enforcement of social norms. In terms of defining the type, degree, and type of social support necessary to develop social capital among groupings, the process of the exchange of goods and services between connected individuals within a social group may be referred to as the social network.

Social network analysis, which is based on social network theory, is a cutting-edge paradigm for social science research and a vital instrument for comprehending social structure. This method in social network theory can be used to gauge how players interact in social networks. As more academics concentrate on social structure research and take into account the “network structure” of social life, some network ideas (such as centrality, density, structural hole, and clustering coefficient) are encroaching. In other words, there is a symbiotic relationship between people and content that is used to find each other (Crothers, Citation2010). Social network analysis emphasises the significance of structure in describing the social environment, according to Rice and Yoshioka-Maxwell (Citation2015).

A collection of qualitative analytical methods called social network analysis has the potential to include socio-cultural phenomena. It is based on an investigation of social actor interactions and the relationship between the structure and features of social networks. A variety of methodologies for analysing links or structures are included in social network analysis, a widely used theoretical approach to structural analysis (Ma, Citation2022). A group of nodes, or social actors, and their connections make up the social network. Social support, economic reciprocity, and interpersonal interactions are the main variables affecting these linkages. As a result, social interaction and social support network practices could be seen as the two most important social network analysis components.

Insofar as this study’s objective is concerned, the definitions of network attributes are conceptualised. A group in a network is initially just a subset of the actors who share norms and values. One clan group, for instance, could be made up of all the actors in a network of clan groups, such as clan leaders and members, who communicate with one another through social ties. Second, the term node or social actor is frequently used to refer to both individuals and clan groups. Social actors interact with others both internally and externally within established social structures. Consequently, a network consists of a group of network players who are connected by either internal or external network linkages. Thirdly, network ties act as connections among clan members.

Individuals, families, communities, and organisations can all be network participants, or “nodes,” as they are also known, in social network analysis because it can occur at different conceptual levels. The way actors interact with one another can also take many different principles. There are currently two approaches to studying social networks: ego-centric analysis, which focuses on inter-personal interaction networks, and sociometric analysis, which considers connections among the entire cast of network participants. Sociometric links, however, can focus on a variety of social interactions, including friendships, romantic partnerships, individuals with whom a person engages in criminal activity or other socially unaccepted inappropriate behaviour, or networks of collaboration between social service organisations (Roldan et al., Citation2017).

4.2. Social network analysis and qualitative network approaches

Social networks can be viewed as made up of individuals or organizations (Kiburu et al., Citation2023). At this contemporary time, ego-centric and sociometric analyses are the two approaches used to study social networks. The former focuses networks on personal interaction, and the latter considers network connections among participants. The second approach focuses on various social interactions, including friendships, romantic partnerships, individuals with whom a person engages in public works, or networks of collaboration between social service organizations (Roldan et al., Citation2017).

In social network theory, the social network analysis method can be used to gauge how players interact in social networks. It is based on investigating social actors’ interactions and the relationships between the strengths and features of social networks. A variety of methodologies identifying and analyzing links or structures are included and widely used in social network analysis (Ma, Citation2022). Academics concentrate more on social structure research and consider the network structure of social life. Besides, some network ideas (such as centrality, density, structural hole, and structural equivalence) are encroaching (Crozers, Citation2012). At this juncture, social network analysis emphasizes the significance of structure in describing the social environment (Rice & Yoshioka-Maxwell, Citation2015). The analysis may be based on a structural equivalency, indicating that a specific person may have an equal role. Furthermore, a social structure called a network links people together and ties them together within a particular social group. Thus, the concept of indirect connectivity is an important one that can be used to coordinate or govern independent social entities (Crozers, Citation2012; Nevard et al., Citation2021).

To connect the aforementioned concepts with the objective of the current study, qualitative network analysis techniques with the production approach were applied. This approach focuses on knowledge sharing between social groups and interactions within the social interactions and environment, conceived as direct and indirect interactions (De Jong et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, this production approach recognizes the importance of process factors within networks of knowledge production and is used to assess the interaction with the environment to societal impacts (Alies et al., Citation2017). Therefore, these approaches supported the study to construct the network maps of the relational processes and interactions between social groups within their local natural environment.

Bennett et al. (Citation2009) drew on previously assumed theories to understand patterns of cultural participation regarding specific individuals’ cultural practices, which were explored through a qualitative approach. Besides, Allington (Citation2016) applied social network analysis to study the importance of peer groups’ common value in operating within cultural fields. Meaning networks and interactions are connected with cultural values, many of which are also open to qualitative exploration of networks (Oancea et al., Citation2017). For instance, social network analysis can bridge the gaps between the theoretical space of objective relations and the real social world phenomenon. The networks serve as both systems of direct and indirect links, indicating maps of social ties in cultural production (Bottero & Crossley, Citation2011). Therefore, the qualitative network map analysis can combine social structural patterns, individual interactions, and network attributes connecting various cultural values.

The qualitative network analysis, as different studies developed and tested via extended interviews conducted as part of the impact study (Oancea, Citation2011) and cultural value study, used a qualitatively grounded network map or diagram based on the gathered information from respondents and assessing the relative strength of the different flows and relationships relevant to articulating and triangulating cultural value practices. This approach pays close attention to concrete interactions and individual relationships through a goal pursued through thematic and descriptive qualitative data analysis (Oancea et al., Citation2015). The qualitative features of the network maps can vividly show the content and flows of the relationships; both the interactions and connections are direct, indirect, incipient, univocal, or reciprocal. Alongside these core elements, the network maps included fundamental subjective relations, the participants’ information flow, and resource use cultural practices. Therefore, this study applied the qualitative approach that correlated and led toward participative and cultural-discursive network analysis.

4.3. Social networks and knowledge sharing : from social capital, social relationship and social structure perspectives

Knowledge sharing is an intentional act that facilitates knowledge transfer so that others can use the knowledge (Scuotto et al., Citation2020). By creating and disseminating information, users of social networks participate actively in social interactions (Zhang et al., Citation2023). The existing literature indicates that knowledge of the situation and Social Networks are positive and significant predictors of knowledge sharing. So, knowledge sharing deals with the interactions, absorptions, and invention of new knowledge, which is believed to be in two directions and occurs between two or more individuals (Boyd et al., Citation2007). By facilitating communication and collaboration between divisions, knowledge sharing creates new opportunities for understanding. It is argued that social networks significantly influence people’s behavioural intentions and improve knowledge sharing at the individual and social group levels. The former is intangible and private, including a person’s knowledge-sharing attitudes. Conversely, the latter is the collective knowledge that belongs to the organization and is shared through mutual identification and behavior (Oufkir et al., Citation2017).

According to Szreter and Woolcock (Citation2004), there are three types of social capital: bonding capital, bridging capital, and linking capital. Social capital is also defined as the goodwill that is engendered by the fabric of social relations that can be mobilized to facilitate actions (Carrillo & Riera, Citation2017). From the perspective of knowledge-sharing, the role of social capital has been understood as knowledge is manageable, meaning management is the determining factor in the process of knowledge-sharing (engineering approach). However, it is the social capital that manages the process of knowledge sharing (emergent approach). Both strategies have a place in the exchange of knowledge. The social capital and attitude-to-behaviour process model emphasizes elucidating individual knowledge-sharing behavior through various factors integrating one factor, such as situation awareness from the attitude-to-behaviour process and Social Network from social capital (Ishrat & Rahman, Citation2020).

Social Networks can assist in identifying potential losses, determining the leaders, establishing standards to differentiate knowledge diffusers from knowledge repositories, and identifying the elements of knowledge diffusion and repositories. Social connections may improve performance by increasing the ability of a family firm’s dominant coalition to rule and by granting access to priceless resources (Nevard et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, social interactions may also influence the dominant family coalition’s desire to pursue specific economic and non-economic goals. A strong sense of shared identity is essential for communal interactions, which can be influenced by birth, clan members, ethnicity, locality, shared experiences, or socialization. For instance, there are stages in building Social integrations. These stages include changes that result in negative social relations (such as fragmentation, exclusion, and polarization) to positive social relations (like coexistence, collaboration, cohesion, and others), which result in community integrations (Lois, Citation2016). From multiple perspectives, strong social interactions could contribute to utilizing natural resources.

4.3.1. Social relations at individual and group social levels

The phrase “social relations” refers to a broad range of interactions, connections, and exchanges between people and their surrounding social and physical environment (Burt, Citation2000). Social connections may improve performance by increasing the ability of a family firm’s dominant coalition to rule and by granting access to priceless resources (Nangle et al., Citation2003). On the other hand, social interactions may also influence the dominant family coalition’s desire to pursue specific economic and non-economic goals. A strong sense of shared identity is essential for communal interactions, which can be influenced by birth, clan member, ethnicity, or locality, but also by shared experiences or socialization. For instance, there are stages in building Social integrations. These stages include changes that result in negative social relations (such as fragmentation, exclusion, and polarization) to positive social relations (like coexistence, collaboration, cohesion, and others) which result in community integrations. From multiple perspectives, strong social interactions could contribute to preventing anti-social behaviours and crimes as well.

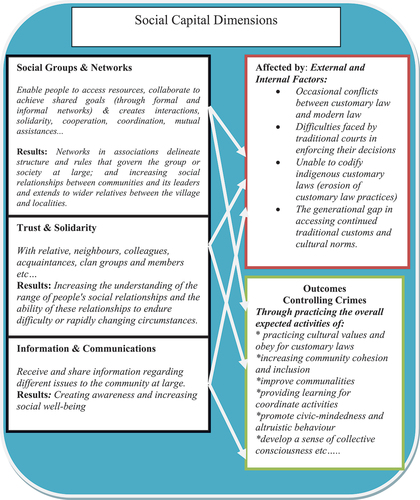

As far as the social interaction process of society, it could be exemplified in the exchange between individuals and clan group members, emphasizing their actions and reactions towards one another. Members’ social interactions discovered that they followed a shared set of norms, rules, and expectations. These functions are governed by a system of unwritten rules of customary law (maa’da) that the society interacts with. When those norms, rules or expectations are violated, the clan head (kedoo abobti), clan councils (makabantu) or customary court judges (barrow eidola) impose consequences, based on the social understanding of how anti-social deviant or criminal behaviour is. For instance, below denotes social relationships, cultural practices, and customary law status as how to develop social well-being and demonstrate social capital dimensions in preventing crimes, all of which imply a certain level of interdependent interactions and network chains. The social capital dimensions in preventing crimes in the framework present the main issues that are assumed to express Afar people’s social relationships and cultural values as well as the possible outcomes that are preventing crimes and their typical relationships with the socio-cultural issues under the mediation of maa’da customary law.

At this point, the framework is supposed to centre on people’s activities and relations within their socio-cultural relationships. Thus, its objective is to support governments and other stakeholders with different perspectives to engage in structured and coherent debate about different factors that challenge social, cultural, economic, and environmental issues, their relative importance, and how they interact. In addition, it can be used in planning, administering indigenous communities, and identifying the main factors for preventing types of crimes and wrongdoings; as well as in codifying the civil and criminal codes of customary law proceedings.

4.3.2. Social structure and traditional social networks

The central sociological concepts, such as social relations, social structure, and social change, would certainly represent the individual and group interactions of society at the Micro, Meso and Macro social levels (Crozers, Citation2012). The Afar society consists of a group of Afar people who interact in a defined territory of Afar land and share a common culture, which is a set of shared practices, values, beliefs, norms, and traditions. The existing literature typically bases the social group network on a particular social network created using characteristics of social relations. Networks of social connections are the primary channel for sharing private information. Private information sharing is the logical decision to maximize self-interest and obtain useful information in return (Crawford et al., Citation2017; Han & Yang, Citation2013). As a result of the information sharing within the social network, people will be better able to make decisions, reducing crime and promoting social cohesion. It is simpler to develop cooperative group behavior within the information network through mutual social learning (Gong & Du, Citation2023). As a result, the network maps listed in the following sections demonstrate the relationships between clan chiefs, kebele officials, and youth organization leaders.

The Afar society could be categorized in the way that it exemplifies the micro level, meso level, and macro level. Each level was explored to understand the types of behaviour that occurred at different levels and the interconnections of these levels of society. For instance, when we see the characteristics of Afar society from a micro-level perspective, we realize members’ one-to-one interactions at times of communication (dagu), resolving conflicts or sharing socio-economic reciprocities. This social level allows members to identify particular dynamics of social phenomena (Serga & Miguel, Citation2019, p. 120).

However, to consider the broader social dimensions that impact social relation processes, the Meso-level perspective leads us to examine a specific clan group and social organizations that are established within Afar society. At this social level, a network analysis approach would help to examine the patterns of social ties among people in a clan group and how these patterns affect the overall clan group, which could be identified. On the other hand, the macro level perspective was applied to examine the Afar Society, which took into account the social, economic and other livelihood potential of the study area that impact societies and individuals. According to Serga and Miguel (Citation2019), this level might not capture important factors of social interactions that occur on the micro level. This implies that the interconnectivity of the three micros, Meso and macro-social level ties determined the value of the social structure and member relationships.

This study used the network degree centrality and clustering coefficient indicators to quantitatively assess how effectively networks like clan groups and member networks spread information. The degree of centrality in the network describes the overall centrality of the network and indicates how tightly the social network is structured around specific network nodes. The network centrality identifies the network nodes that are particularly important for the spread of information. The greater the value, the more important these nodes are, and the quicker information spreads throughout the network (Xing et al., Citation2023), like members are being prepared to stop specific criminal activities or a risk that will harm the community. Ties and relationships link Social network actors together.

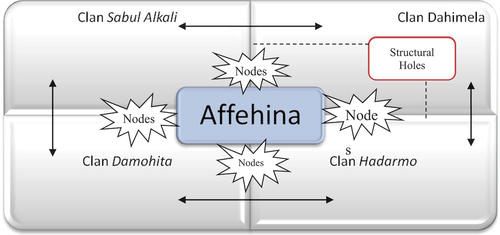

Social networking analysis is the mapping and measurement of relationships and flows between people, groups, organizations, or other information- or knowledge-processing entities. As Figure below represents, a conjunction point (black double arrow line) represents a clan member’s attitude towards other clan groups, reciprocity, or social interactions within their clan group network (Affehina). Within a clan, each member is expected to and by accepted norms, and values subjected to a reciprocate set of activities, such as conducting social relationships, helping each other at times of marriage (Harrayna Kurra), and sharing available resources at times of emergencies (Edebbonta). The components of a given clan (mostly clan heads) are responsible for the clan’s integrity and individual well-being. This is similar to how a clan connects its members or a clan union creates an assembly.

To depict clans’ networks, it is vital to see the idea of structural balance because at least one clan has one Affehina network. In zone one, Awsi-Rasu, there are currently many clan groups, but some of the clans with larger members of people are Maissera, Sidihabura, Geleila, Kebirto, Abba Koloyta, Segentu, Gawya, Masara, Hamedu Sirett, and others. From examining triads of relations, for instance, among the above-mentioned four clans’ heads and members, it can be readily seen that some triads are balanced because of the Affehina network. If Clan Sabul Alkali members communicate with heads and members of Clan Dahimela, Clan Dahimela members and heads interact with Clan Bedoiti, and Hadarmo interact with Damohita, the triad is balanced; if Clan Sabul Alkali members interact with Clan Damohita, the triad is also balanced. It can also be mentioned here that other Afar clans, such as Sebekak with Hassobu and Rakbak with Deromella, connect in such network types. This type of qualitative networking analysis is interesting in that it provides predictions about the longer-term stability of clan groups based on the characteristics of their constituent triads.

Furthermore, structural holes are the gaps in a network pattern and provide a space for some actors to take advantage of entrepreneurial opportunities for those actors in the existing pattern to move into and exploit, as the red bound in Dahimela clan territory (a person with an administrative or political post) indicates, and the dotted lines exemplify the gap (disconnection) in the network. For instance, one of the key informants in this case outlined:

The most important detail is that if one of the clan members can provide additional support to their clan members, it may provide insights into society at large, but it does not mean that the large social structure constrains his interests. Instead, his network link, in such benefits, disconnects from other clan interests. [KI10, male-3, livelihood expert, 49 years old, Logya-Samara]

The network locations of individuals change throughout social and economic reciprocity. In a given clan group, each group of people forms a network centred on that specific clan. Analysis may be based on a structural equivalency, indicating that a specific person may have a structurally equivalent role such as clan leader, elders’ council head, or youth (Fimma) leader.

In this instance, networking relationships are the bonds that are established or formed between members of the same social groups (Burra- family, Dahala-extended family or sub-clan, and Clan-Kedoo) and between linked clans. The connection of the actor is also known as intimate ties. Friendship (kataisa) relationships, within and outside one’s clan or kin, shared interests, interdependence, and other advantages are just a few of the many reasons for establishing links with other actors (Crozers, Citation2012). For instance, when advising another person (or social group), an actor can be managed by another actor in a one-directional effect (Sultanates manage clan leaders, and clan leaders administer clan members). Whether they are present or not, whether they are friends or not, actors can have a dichotomous connection with other actors based on their physical proximity to them (Nevard et al., Citation2021). In addition, a connection between ties of a particular type constitutes a social relation, and each connection of actors defines a different network with connections referred to as a networking relationship (Liu & others, Citation2017). This implies that the strength between ties will determine the value of the relationship between actors. This study found that network ties and relationships would be more commonly used to depict member interactions and clan group network structures. Therefore, clan group networking activities consist of both informal and formal connections established to promote smoother interactions and prevention of crimes based on trust and cooperation between members.

4.4. Proposed mechanisms to incorporate Afar’s customary law (maa’da) practices and procedures into state structure criminal justice system

4.4.1. Customary practices and customary laws

The present study does not attempt to define customary law, but some general comments on its character may be helpful. First, the idea of customary law that is under consideration concerns the laws, practices and customs of indigenous people and communities. Customary law is, by definition, intrinsic to the life and customs of indigenous peoples. What connects to customary law as such depends very much on how the Afar themselves perceive those questions, and on how they function as local communities. According to one definition, “custom” is the rule of conduct, obligatory on those we think its scope, established by long usage. A valid custom must be of immemorial antiquity, certain and reasonable, and obligatory through mainly derivates from the common law.

Customary law refers to an established pattern within a community that is seen by the community itself as having a bonding quality. For instance, customary laws are defined variously by some authorities as “customs that are accepted as legal requirements or obligatory rules of conduct, practices and beliefs that are so vital and intrinsic part of a social and economic system that they are treated as they were laws and established patterns of behaviour that can be objectively verified within a particular social setting. Customs acquired the force of law when they became the undisputed rule by which certain entitlements (rights) or obligations were regulated between members of a community (Swiderska et al., Citation2006). The validity of which is established by custom, in contrast to specific legislation or statutory law. Another definition sees customary law as locally recognized principles and more specific norms or rules that are orally transmitted and applied by community institutions to internally govern and guide all aspects of life (Ndulo, Citation2011).

Customary laws and practices are the very identities of many indigenous people and local communities. These laws and practices concern many aspects of their life. They can define rights and responsibilities, duties and obligations of members of local communities on important aspects of their life, culture and world view. Customary law can relate to the use of and access to natural resources, rights and obligations relating to land, inheritance and property, the conduct of spiritual ties, maintenance of cultural heritages and knowledge systems, and many other matters.

Customary law can help to define or characterize the very identity of the community itself. Furthermore, for many local communities, it may be meaningless or inappropriate to differentiate their laws and customs, suggesting it has some lesser status than other laws, it seemingly constitutes their law as such. Therefore, customary law can be crucial for the continuity and vitality of the interrelated culture, social and spiritual life and heritage of local communities. So maintaining customary laws at every level in the original community is an important concern. It is one of the key aspects of preserving the loyalty of the local community. Local communities have also called for various forms of respect and practices of their customary laws.

Although some aspects and statements of customary law do not replace the existing customary law, which is still interpreted and applied by traditional authorities and changes over time, customary law (maa’da) in the Afar context is typically subordinate to unwritten laws. The Sultanate, clan heads, council of elder members, as well as the consent of Afar communities, are all required for the modification and amendments of customary law. Customary law is administered by traditional peoples’ institutions, and at least the older members of the community elders and clan councils (Makabantu or maa’da abobti), who are generally aware of the validity of such laws, their contents, and the related procedures, that are not recorded in writing. By enacting a statute, the sultanate or clan councils can modify a customary law. Traditional courts now have legal recognition under this statute, which also incorporates them into other social institution practices (Ani, Citation2013). Afar’s customary law is given a top priority, which is intended to administer and manage people with cultural norms, laws, practises, and socio-economic interactions. For instance, it regulates customary practices, such as marriage, reciprocities, resource usage, communications, disputes, and wrongdoing. Hence, the practices are habitual behaviours that are followed for a longer period without the use of coercion (Ndulo, Citation2011).

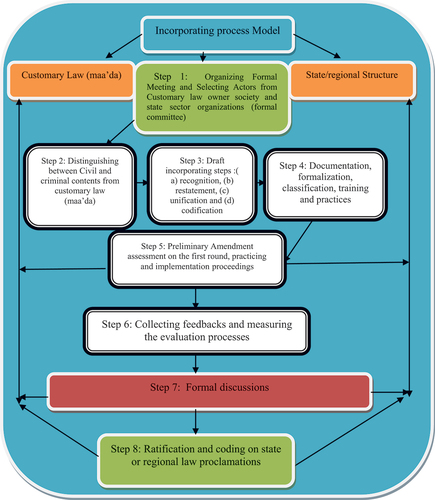

Scholars debate the benefits and drawbacks of customary law. According to Ndulo (Citation2011), customary law does not distinguish between criminal and civil cases, and a single proceeding frequently entails a payment that serves as both a partial punishment for wrongdoing and partial compensation for the harm caused to the victim who was wronged. According to Wagner and Sherwin (Citation2014), compensation may go to the family of the victim rather than the person who was harmed directly. In a communal society like Afar, compensation is differentiated and for harm is taken on by clan members instead of the perpetrator.