?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Socioeconomic hardships are often advocated as the drivers of radicalization, but the existing research shows mixed evidence for this relationship. This study argues that socioeconomic hardships should increase the likelihood of radicalization only for sufficiently religious people, thereby implying a non-linear relationship. The study suggests that as a result of the lower opportunity costs of extreme acts during socioeconomic hardships, the likelihood of committing or supporting such acts for obtaining religiously inspired mental rewards should be the highest for the economically disadvantaged, religious individuals. The study tests this hypothesis through the non-linear threshold regression method developed by Hansen (2000), using survey data from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Results indicate that radicalization has a statistically significant positive relationship with indicators of the individual level socioeconomic conditions such as the perceptions of poor economic prospects, individual relative deprivation, injustice, and inequality only above the religiosity threshold. These findings support the hypothesis that socioeconomic hardships (or the perception of these) drive radicalization only in sufficiently religious people. This implies that apart from security-centric approaches, radicalization can also be deterred by increasing the opportunity costs of political violence through socioeconomic improvements. Moreover, promoting balanced/diverse religious views may also help check radicalization.

1. Introduction

Radicalization is a threat to the security and stability of nations. Radicalization is defined as the support/endorsement that one renders to the use of violence for accomplishing political or religious goals (Rink & Sharma, Citation2018). This definition is in line with the various definitions of the phenomenon provided by prominent scholars in the field as well as with the definitions advanced by various governmental agencies that emphasize radicalization as a process that entails justifying violence for attaining certain goals (Crossett & Spitaletta, Citation2010; McCauley & Moskalenko, Citation2008; Wilner & Dubouloz, Citation2010). Given the global rise in radicalization, it is imperative to ask which factors drive this process. The existing literature attribute radicalization to a diverse mix of psychological, economic, social, and political factors. Among these, economic factors receive considerably large attention from academics, policymakers, and journalists. The presumed link between economic factors and terrorism also plays a major role in international security and counter-terrorism policies. However, the empirical analysis of this relationship reveals a complicated picture.

Studies investigating the relationship between socioeconomic factors and radicalization can be grouped into three categories. The first strand detects no relationship between radicalization and socioeconomic factors such as poverty, economic disparity, inequality, discrimination, and economic marginalization (e.g., Bhui et al., Citation2014; Blair Graeme et al., Citation2013; Groppi, Citation2018; Rink & Sharma, Citation2018). The second strand finds that socioeconomic hardships such as economic marginalization, inequality, exclusion, and deprivation are instrumental in catalyzing radicalization (e.g., Bäck Emma et al., Citation2018; Ceder et al., Citation2011; Holla, Citation2020; Lindekilde et al., Citation2016; Macdougall et al., Citation2018). In contrast, the third strand finds that instead of the poor and marginalized, individuals from affluent backgrounds are more likely to radicalize and commit extremist violence (e.g., Bhui et al., Citation2014; Blair Graeme et al., Citation2013; Delia Deckard & Jacobson, Citation2015).

The existing literature tests a wide range of economic variables as plausible determinants of radicalization. Yet, there is no real consensus on the relationship between socioeconomic factors and radicalization. Most empirical studies on the phenomenon assume a linear relationship between radicalization and socioeconomic factors (Franc & Pavlović, Citation2021b). However, the linearity assumption may not hold up in all cases (Arin et al., Citation2021). For instance, Andreas et al. (Citation2011a) studied the relationship between real GDP per capita and terrorism in 110 countries. They found that up to a certain level, an increase in per capita GDP results in more terrorism since higher income enhances the state’s repressive capacity, allowing only for clandestine (terrorist) activity instead of open rebellion. Afterward, more per capita income means less terrorism due to a rise in the opportunity cost of terrorism. Such “switch points” could also be salient in the relationship between individual-level socioeconomic factors and the individual decision to support or commit terrorist acts. However, most studies test this relationship through linear models using data on terrorist activity and aggregate socioeconomic indicators. Ignoring the potential switch points restrict studies to only one coefficient for the explanatory variable when there should be separate coefficients delimited by the range of the switch point (Arin et al., Citation2021).

This study proposes an alternative non-linear mechanism for the relationship between radicalization and the individual-level perceptions of socioeconomic conditions/prospects based on opportunity costs and the mental rewards of extreme acts. Socioeconomic hardships (or the perception of these) reduce the opportunity costs of extreme acts, making it attractive to gain mental rewards by supporting or participating in such acts (Andreas et al., Citation2011b). However, subscription to mental rewards of extreme acts may depend upon the degree of personal religiosity since religion bestows ideology and purpose. This is to say that a certain level or threshold of religiosity must be reached to perceive extreme acts as avenues of mental rewards during socioeconomic hardships. In other words, this study hypothesizes that socioeconomic hardships should drive radicalization only in sufficiently religious people.

To test the above hypothesis, this study uses the non-linear threshold regression method developed by Hansen (Citation2000) that, splits the data, and searches for the existence of multiple regimes. Hansen’s (Citation2000) method endogenously detects the presence of the possible switch points from the data when their existence is not known a priori. It further allows the coefficients to vary across regimes that lay below or above the switch points or threshold values. Several studies have used this method to investigate the existence of switch points in the relationship between different economic variables. Some examples include investigating the relationship between trade and economic growth using trade openness as a threshold variable (Papageorgiou, Citation2002), the relationship between economic growth and financial development using institutional quality as a threshold variable (Law et al., Citation2013), and the relationship between foreign direct investment and economic growth using financial market development as a threshold variable (Azman-Saini et al., Citation2010). Drawing on these, this study splits the data into different regimes or classes using religiosity as a threshold variable and estimates the effect of the varying degrees of religiosity on the relationship between socioeconomic factors and radicalization.Footnote1

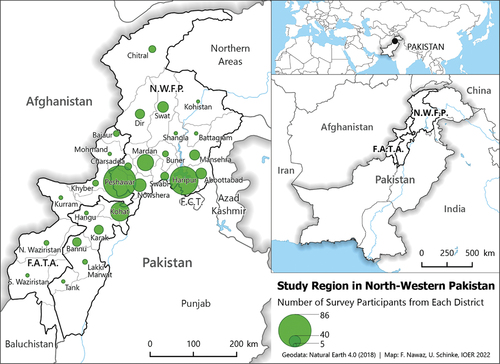

This study contributes to the literature in two ways. First, it uses novel survey data from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (K.P) province of Pakistan. K.P is one of the most marginalized and economically disadvantaged regions of Pakistan. It has also been the key recruitment ground for several Islamist militant groups such as the Afghan Taliban, Al-Qaeda, and the Pakistani Taliban. Moreover, it is currently experiencing a surge in various types of religious violence, such as suicide attacks, targeted killings of religious minorities, sectarian clashes, and blasphemy vigilantism. Given these factors, this study provides empirical evidence from a region that exhibits a unique combination of socioeconomic hardships, militant groups motivated by supreme values, and a high degree of religious violence. Second, it demonstrates the existence of a non-linear relationship between socioeconomic factors and radicalization using Hansen’s (Citation2000) methodology. For instance, the study finds a statistically significant positive relationship between radicalization and the individual perceptions of economic prospects, relative deprivation, injustice, and inequality only above the religiosity threshold. This supports the hypothesis that socioeconomic hardships drive radicalization only in sufficiently religious people. This suggests that apart from security-centric approaches, radicalization can also be deterred by increasing the opportunity costs of political violence through socioeconomic improvements.

2. Socioeconomic hardships & radicalization in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: a brief overview

Pakistan faces serious challenges posed by radicalization and religiously inspired extremism. This is evident from the scores of terrorism incidents faced over the past two decades. For instance, from 9/11 to date, Pakistan suffered 29,721 terrorism incidents, including 597 suicide attacks, and received 65,271 fatalities. However, these losses are disproportionately spread across Pakistan, with K.P., which houses 17% of the country’s population, receiving the biggest brunt (“Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.”, Citation2017). Out of the total terrorism incidents 13,265 (44.5%) occurred in K.P, coupled with 362 (60.6%) of all suicide attacks and 45,975 (70.4%) of all fatalities (South Asia Terrorism Portal, Citation2022).

The uneven impact of terrorism goes hand in hand with the relatively dismal state of socioeconomic development in K.P. For instance, in terms of gross regional product, K.P. ranks third among Pakistan’s four provinces, indicating a lower level of economic activity. In terms of provincial per capita income, K.P. ranks third, 9.3 % below the national average. Corollary to these economic facts, K.P. also exhibits a relatively poor state of human development. This is indicated by the low Human Development Index (H.D.I) score, which ranks K.P. third among the four provinces (Pasha, Citation2021). Likewise, K.P. further manifests the second-highest incidence of multidimensional poverty among the four provinces of Pakistan (Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, Citation2021).

K.P. also has a long history of religious mobilization. People from this region recruited into Jihadist movements during various epochs. For instance, in 1826, Syed Ahmed Barelvi, an Islamic revivalist from India, came to N.W.F.PFootnote2 (now K.P) and urged the local populace to join him in establishing an Islamic state and waging Jihad against the then neighboring Sikh empire. After securing the support and participation of the local Pashtun tribes, he launched his Jihadist campaign against the Sikh army in 1831 (Z. Khan & Ullah, Citation2018). In 1948, Pakistan and India fought their first war over the disputed territory of Kashmir. Instead of regular troops, Pakistan entered the war using Pashtun tribesmen from N.W.F.P. who joined the conflict against the “Hindu India” under Jihadist motivations (Yousaf, Citation2019). In 1979, the then-U.S.S.R. invaded Afghanistan. Under the aegis of the United States, Pakistan undertook the recruitment, indoctrination, and training of the anti-Soviet MujahideenFootnote3 fighters predominantly in K.P (Ahmad, Citation2013). After 9/11, K.P became the recruitment ground, sanctuary, and launching pad of Al-Qaeda and the Afghan Taliban in their fight against the N.A.T.O forces in Afghanistan (Gunaratna & Nielsen, Citation2008). Currently, K.P is facing a surge in various types of religious violence, such as suicide attacks, targeted killings of religious minorities, sectarian clashes, and blasphemy vigilantism.

The above discussion indicates that the socioeconomic disparities are seemingly in tune with the religious mobilization in K.P. This line of reasoning is advocated by several studies that posit a link between socioeconomic hardships and radicalization in Pakistan (e.g., Ahmed et al., Citation2018; Yusuf, Citation2008). However, most studies propose such linkages primarily on the basis of macro/aggregate level data on socioeconomic indicators. Nevertheless, macro-level variables indicate the state of the overall social context surrounding the individuals. Moreover, numerous studies argue that the social context can greatly moderate the relationship between individual-level perceptions/variables and political beliefs (e.g., Federico & Malka, Citation2018; Jasko et al., Citation2020). This could also be salient in the case of K.P, which exhibits a confluence of poor socioeconomic conditions and a high degree of religious violence. Despite receiving considerable attention, there is a dearth of studies that test the linkages between individual-level socioeconomic conditions/perceptions and the individual decision to commit or support extreme acts. This study empirically tests these linkages using survey data from the K.P province of Pakistan.

3. Theoretical background

This study adopts the theoretical framework of Freytag et al. (2011), who explained the emergence of terrorism from the rational choice perspective. Terrorism is seen as a consequence of the socioeconomic conditions of the terrorists or their Umfeld. Terrorists and their supporters are assumed to be rational actors whose behavior is directed by the costs, benefits, and opportunity costs of extreme acts. Likewise, terrorism or its support is viewed as one of the many choices influenced by economic constraints. Of particular importance are the opportunity costs, which indicate the alternatives that one needs to sacrifice while committing or supporting extreme acts.

Under the opportunity costs framework, radicalization results from a trade-off between material and mental rewards. Material rewards, such as income, are obtained by refraining from extreme acts and participating in activities that produce material well-being. Conversely, mental rewards like social recognition, feelings of significance, power, and martyrdom are collected from supporting or committing extreme acts. Individuals opt for extreme acts to seek mental rewards as long as the resulting benefits exceed the (opportunity) costs. The socioeconomic conditions of individuals may significantly influence these cost-benefit calculations. For instance, economic hardships indicate low material rewards from non-violence. This renders the mental incentives associated with extreme acts attractive prospects for individuals.

In the case of religious (Islamist) radicalization, the opportunity cost considerations are likely to be influenced by the degree of individual religiosity since religion bestows ideology, purpose, and mental rewards/incentives. It is therefore intuitive to assume that a higher degree of religiosity would presumably translate into a greater propensity to political violence when faced with economic hardships. In other words, a certain level or threshold of religiosity must have to be reached to perceive extreme acts as avenues of mental rewards during socioeconomic downturns. This study tests this prediction using survey data of undergraduate students from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Specifically, it tests whether socioeconomic hardships drive radicalization only in sufficiently religious people. This is accomplished using a diverse range of variables drawn from the existing literature, such as economic prospects, relative deprivation, perceived inequality, and perceived oppression, etc. A systematic review of the relevant scholarly literature was conducted to identify various socioeconomic factors considered to be the pivotal drivers of radicalization by scholars in the field. Next, through consultation with local academics aware of the radicalization landscape in Pakistan, the most plausible of these variables were selected for empirical testing. These questions/items used to construct these variables measure aspects related to rational choice and collective social identity. The study also uses religiosity as a variable to account for the ideological component underlying radicalization. The study thus draws insights from three different perspectives which are considered to be complementary (James & Dawson, Citation2023). These variables are discussed in detail below. All variables measure the respondents’ perceptions regarding the situations depicted in the questions/construct used to construct these.

3.1. Economic prospects

Literature on the phenomenon frequently mentions that poor economic prospects can considerably influence the radicalization process. For instance, Lehmann and Tyson (Citation2022) developed a model of the strategic interaction between the state and radical groups. Specifically, they theorized the effects of the mutual anticipation of each another’s choices on the consequent responses. They argued that the government’s policy to enhance economic growth improves the economic prospects of the citizens, which significantly deters the radicalization process. Freytag et al. (2011) studied the socioeconomic determinants of terrorism in 110 countries and found that economic development and improvements in future prospects can significantly reduce terrorism. Holla (Citation2020) studied the relationship between the perception of economic marginalization and radicalization through a correlation research design using survey data of Somali Muslims in Kenya. The study found that the perception of marginalization is related to a rise in radicalization. However, unlike the current study, Holla (Citation2020) did not study the conditional effect of religiosity on this relationship. Yusuf (Citation2008) studied the process of youth radicalization in Pakistan and considered the lack of socioeconomic opportunities to be an important catalyst of this process. Ahmed et al. (Citation2018) assessed the determinants of terrorism in Pakistan based on the opinions of university students. A considerable number of students were of the view that the lack of socioeconomic development is associated with susceptibility to terrorism. Drawing on these accounts, this study tests the relationship between the perception of poor economic prospects and radicalization in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan.

3.2. Political marginalization

Opportunities for political participation increase the likelihood of economic success, which reduces the need to resort to extreme acts for voicing dissent (Andreas et al., Citation2011b; Wahl, Citation2019). Conversely, political marginalization deters the chances of economic prosperity and makes political violence more likely (H. E. Hansen et al., Citation2020). Choi and Piazza (Citation2016) tested the relationship between political marginalization and terrorism using data from 130 countries. They found that countries where certain ethnic groups are politically excluded, are more likely to suffer from domestic terrorism. Meierrieks et al. (Citation2021) studied terrorism in 99 countries and found political exclusion associated with terrorist activity. Dalacoura (Citation2006) studied Islamist terrorism in the Middle East and argued that political exclusion contributes to the adoption of terrorist methods. Zeb and Shahab Ahmed (Citation2019) also found political exclusion as an important factor behind terrorism in Pakistan. Drawing on these accounts, this study tests the relationship between radicalization and political marginalization in K.P.

3.3. Relative deprivation

Another factor that may drive individual radicalization through socioeconomic differences is the perception of relative deprivation. Relative deprivation is a situation when one considers himself subjected to unfair treatment or disadvantage. This generates anger, resentment, and a desire for revenge against the depriver (Bergen Diana et al., Citation2015; Obaidi et al., Citation2019). Macdougall et al. (Citation2018) analyzed survey data from the U.S. and Netherlands and found that relative deprivation predicts willingness to join violent groups. Obaidi et al. (Citation2019) assessed the relationship between relative deprivation and violent extremism among Muslims in Western countries. They found group-based relative deprivation associated with the endorsement of extremism. Pearson (Citation2016) also found socioeconomic deprivation as an important catalyst for the actions of Roshonara Choudhry—a British lone-wolf terrorist who attacked a parliament member in 2010. Drawing on these accounts, this study tests the relationship between radicalization and measures of individual and collective relative deprivations in K.P.

3.4. Injustice

Socioeconomic differences may catalyze the perception of injustice among individuals, which can provoke anger and violence as compensatory reactions (Al-Saggaf, Citation2016; Van Brunt et al., Citation2017). Doosje et al. (Citation2013) studied the process of radicalization in Dutch Muslims and found perceived injustice to be an important predictor of the radical belief system. Pauwels and Heylen (Citation2017) studied Belgian adolescents and young adults and found that perceived injustice wields a significant impact on right-wing extremism. Based on semi-structured interviews with right-wing, left-wing, and religious extremists in Belgium, Schils and Verhage (Citation2017) also found perceived injustice as a starting point of radicalization. Drawing on these accounts, this study includes perceived injustice in the empirical analysis.

3.5. Exclusion

The mental rewards of extreme acts may be particularly attractive for individuals experiencing social or economic exclusion. Exclusion induces significance loss which inspires a quest for significance seeking. In such a situation, subscription to extremist ideologies and groups contributes to personal significance and the incremental ingress into radical schemas. Bäck Emma et al. (Citation2018) tested this in Swedish university students and found that social exclusion, and a subsequent inclusion by radical groups, results in the adaption of the group’s attitudes. Lindekilde et al. (Citation2016) studied Danish Islamist foreign fighters and found exclusion as an important factor in their radicalization. Moreover, Hansen et al. (Citation2020) examined sub-national terrorist violence and found that regions with excluded ethnic groups exhibit a higher risk of terrorism. Given the prevailing perception of exclusion in the study setting, this variable is included in the empirical analysis.

3.6. Inequality

An individual’s perception of socioeconomic inequality may also act as an important factor in the opportunity cost calculations underlying the radicalization process. Franc and Pavlović (Citation2021)a reviewed the relevant literature and argued that the perception of social inequality is related to radical attitudes. Ceder et al. (Citation2011) studied global horizontal inequalities and found that unequal societies face violent conflict more often than relatively equal ones. Ahmed et al. (Citation2018) assessed the domestic triggers of terrorism in Pakistan and found inequality as an important factor in pushing individuals towards militant groups. By studying the 13 Daesh-affiliated Bulgarian Imams, Panayotov (Citation2019) also found that individuals from unequal regions may be highly susceptible to radicalization. Drawing on these accounts, this study includes perceived inequality in the empirical analysis.

3.7. Oppression

The perception of oppression may also stem from the lack or access to the opportunities of economic prosperity. Such a perception is likely to make the mental rewards of political violence particularly attractive. Milla et al. (Citation2013) studied Bali bombers and found the oppression of Muslims as a key motivation for their bombings. Manuel and Trujillo (Citation2014) studied radicalism intentions in Spanish Muslim and Christian school students. They found perceived oppression and radicalism correlated in Muslim students. In K.P, people widely perceive that they are being oppressed by the dominant ethnic groups. Given this, the current study includes perceived oppression in the empirical analysis.

3.8. Religiosity

Since the mental rewards of religiously motivated extremist acts stem primarily from religion, religiosity can therefore play an important role in the radicalization process. For instance, Coid et al. (Citation2016) investigated the population distribution of extremist views in a sample of young men (18–34 years) from England, Scotland, and Wales. They found a significant relationship between religiosity and anti-British extremist views. Dawson (Citation2018) conducted interviews with Western foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq and their friends and families. They found that religiosity plays a substantial role in terrorism, particularly in the case of Jihadism. Rink and Sharma (Citation2018) studied the determinants of religious radicalization using survey data from Kenya. They found religiosity to be an important predictor of radicalization. Beller and Kröger (Citation2018) studied the predictors of support for extremist violence among Muslims from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Egypt, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Malaysia, and Russia. They found support for extremist violence strongly associated with social religious activities. Drawing on these accounts, this study includes religioisity in the empirical analysis.

4. Material design and methods

4.1. Participants of the study

It is generally believed that radicalized individuals in Pakistan come from poor and highly religious backgrounds. They are also believed to be either illiterate or educated in religious seminaries, called Madrassahs. This stereotypical narrative is reiterated by journalists, security officials, and policymakers alike (Delavande & Zafar, Citation2015). While it was relatable to earlier generations of extremists, it is evident from recent incidents that the radicalization landscape in Pakistan has considerably evolved and transformed (Dawn, Citation2017). For instance, in the year 2015, several Al-Qaeda-affiliated militants attacked and killed 43 members of the Ismaeli Shia community traveling in a bus. It was later found out that these militants are highly educated individuals possessing university degrees (Zahid, Citation2015). Likewise, in 2017, a medical student from Pakistan, Naureen Leghari, left home and visited Syria for joining the militant Islamia State (IS) group. She received militant training there and came back to Pakistan to conduct a suicide attack on a Church on Easter (Firdous, Citation2017). In another incident in 2017, a journalism student, Mashal Khan, was alleged by fellow students of posting blasphemous content against Islam on Facebook. Over these allegations, he was later lynched inside the university campus by other students (Singay, Citation2020). In 2018, Faheem Ashraf, a college student killed his college principal who had reprimanded him for being absent from the college for several days to attend the rallies supporting the strict blasphemy laws of Pakistan. The student later admitted the murder without remorse claiming that his action was aimed at safeguarding the honor of the Prophet Muhammad (Yilmaz & Shakil, Citation2022). Similarly, in 2019, another student, Khateeb Hussain, killed his teacher on accusations of blaspheming against Islam and for supporting un-Islamic culture (Imran, Citation2019). From these incidents, it could be deduced that instead of the illiterate and impoverished, the highly educated individuals are increasingly becoming radicalized, and educational institutes are seemingly contributing to this process (Iqbal & Mehmood, Citation2021). Hence, university students appear as a relevant sample to study the drivers of radicalization. Therefore, primary data was collected from undergraduate students of 19 universities in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan through a survey conducted between December 2019 and March 2020. The study region can be seen in the map given in Figure .

It was initially planned that a pen-and-paper survey would be conducted. However, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the worsening security situation amid the U.S-Taliban peace deal, it was not possible to travel to the study region. Therefore, Google Forms was used to administer the survey remotely. The questionnaire was pasted into Google Forms and its web link was generated. Afterward, through personal contacts, the university teachers in the target region were approached and requested for the implementation of the survey. Due to the pandemic, physical classes were on a halt. Therefore, the faculty members reached the participants via phone and obtained verbal consent after explaining that the survey is conducted solely for academic research and that their responses will remain anonymous since no personal information like name and address are collected. The questionnaire link was then shared with participants primarily through WhatsApp which they filled remotely. This procedure ensured the safety of the interlocuters and also helped mitigate the response bias since nobody was watching the participants filling out the online questionnaires. To ensure data security, the participants were not shown their or other partcipants’ responses after they submitted the survey form upon completion.

In total, 510 respondents took part in the survey. All participants identified themselves as Muslims. Nearly half of them are female (52%). Only a few of them are married (5.3%). In terms of age, most participants (92%) are between 18 and 23 years old. Complete descriptive statistics are given in Appendix 2.

4.2. Radicalization measure

Most studies on radicalization in Pakistan usually assess the phenomenon from a historical perspective and are mostly of descriptive nature. Hence, they do not contain a scale elaborate enough to empirically measure radicalization. Nevertheless, three studies are an exception to this general pattern.

The first of these studies is undertaken by Fair et al. (Citation2012), who analyzed whether religiosity predicts support for political violence in Pakistan. The second study is undertaken by Blair Graeme et al. (Citation2013), who assessed whether poverty is associated with militant support in Pakistan. These studies solicited the participants’ views regarding support for militant Islamist organizations to construct their dependent variables. The third study is undertaken by Bélanger et al. (Citation2019), who assessed the predictors of ideologically-based violence in four countries, namely Pakistan, Canada, the U.S, and Spain. They constructed their dependent variable using a set of six questions/items for all the aforementioned countries. While these studies offer valuable information about the phenomenon, their radicalization scales/measures, nevertheless, miss certain important issues that are of crucial importance in understanding radicalization in contemporary Pakistan. Some of these issues are persecution/vigilantism over blasphemy allegations, the widespread resentment against members of the Ahmadiyya community, military operations inside Pakistan, and the U.S occupation of Afghanistan—all potentially serving as important catalysts of radicalization in Pakistan. Moreover, unlike the current paper, these three studies also lack a simultaneous focus on socioeconomic variables and religiosity. For instance, Fair et al. (Citation2012) studied the relationship between religion and political violence but did not include economic variables in the empirical analysis. Likewise, Blair Graeme et al. (Citation2013) assessed the relationship between poverty and militant politics but did not study the role of religiosity. On the other hand, Bélanger et al. (Citation2019) focused entirely on psychological variables without including the economic and religious dimensions in their empirical analysis.

To build a comprehensive scale for measuring radicalization, nine items/questions are drawn from the questionnaire of Rink and Sharma (Citation2018) who studied the drivers of religious radicalization in the Kenyan case. These nine items measure support for militant groups and violent behavioral intentions. Four main reasons inspired the choice of using Rink and Sharma’s (Citation2018) survey instrument as a baseline. First, Rink and Sharma (Citation2018) chose their survey participants from the Eastleigh district in Kenya. Eastleigh houses Somali immigrants and recruiters of the Somalia-based terrorist group, Al-Shabaab, in large numbers. Such parallels also exist in the context of K.P which too consists of a large number of Afghan refugees and recruiters of the Pakistani and Afghan Taliban. Second, poor socioeconomic conditions are viewed as one of the key drivers of radicalization in Eastleigh (Chepkong’a, Citation2020). Likewise, several scholars consider the dismal state of socioeconomic conditions in KP as one of the important catalysts of radicalization and violent extremism (e.g. Khan & Ahmed, Citation2017a; Naz et al., Citation2013; Wahab & Hussain, Citation2021). Third, Rink and Sharma (Citation2018) drew on the inter-religious tensions existing between the Christians of Muslims of Kenya to assess the predictors of religious radicalization. Such tensions among the followers of different Islamic sects are also considered one of the main drivers of radicalization in Pakistan. Finally, Rink and Sharma (Citation2018) operationalized and tested their radicalization scale in Eastleigh, Kenya, which exhibits religious violence as a recurring feature. Religious violence is an increasing phenomenon in K.P as well which currently faces a surge in suicide bombings, target killings, and persecution over allegations of blasphemy. Given these reasons, the questionnaire of Rink and Sharma (Citation2018) appeared as an optimal choice for the current paper.

Considering the specific context of Pakistan, six additional items, that measure support for blasphemy vigilantism, are constructed and added to build the radicalization index. The radicalization scale of this study, which consists of 15 items, measures support for militant groups, violent behavioral intentions, and support for persecution/vigilantism under the allegations of blaspheming against Islam.

These 15 items/questions are combined and standardizedFootnote4 to create the dependent variable of this study, i.e. the radicalization index (Cronbach’s alpha: .78). The survey questions are given in Appendix 1. A table containing full descriptive statistics regarding the responses to the survey questions is given in Appendix 2.

5. Method

This study hypothesizes that socioeconomic hardships increase the likelihood of radicalization for obtaining mental rewards only in sufficiently religious people. In other words, the relationship between socioeconomic factors and religious radicalization may be non-linear, and only after a certain point will religiosity make the mental rewards of political violence attractive while facing socioeconomic hardships. To test this hypothesis, this study uses the non-linear threshold regression approach developed by Hansen (Citation2000). Using religiosity as a threshold variable, this technique splits the sample into two regimes or classes, which allows testing the relationship between socioeconomic factors and radicalization at different degrees of religious adherence. The empirical model of this study in the linear form takes the following shape:

where is the dependent variable for individual i,

represents the socioeconomic variables and

is a vector of controls (gender, age, marital status, family size, and family income).

To test the non-linearity assumption discussed above, the threshold regression model is written as follows:

where Religiosity is the threshold variable used to split the sample into two regimes, and is the unknown threshold parameter. First, the null hypothesis of linearity (H0: β1 = β2) is tested against the threshold model (equation 2) using the fixed bootstrap procedure.

6. Results

Results of the threshold regression are given in Table . Since religiosity is co-linear with several explanatory variables, it is used only as a threshold variable. The results of the pairwise correlation test are reported in Appendix 3.

Table 1. Threshold regression

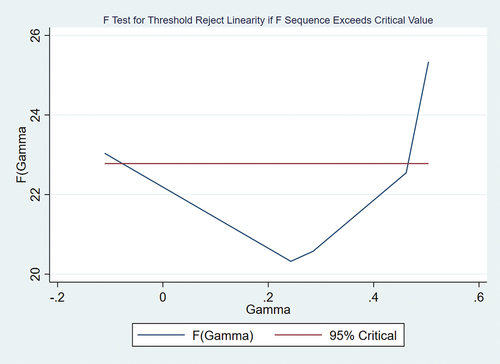

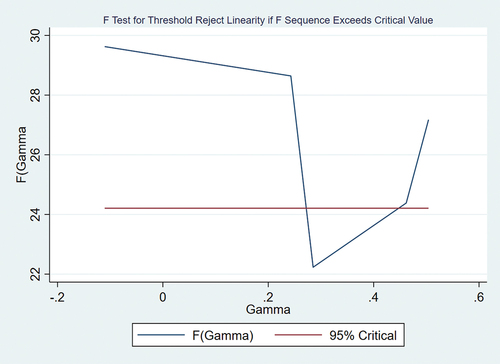

The statistically significant bootstrap p-value in Table signifies the rejection of the linearity/no-threshold assumption. This p-value corresponds to 5000 replications and a 15% trimming percentage. The existence of the threshold effect is also confirmed in Figure , where the F Sequence exceeds the critical value, thereby indicating the rejection of the linearity assumption.

For comparison, an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model was also estimated, which showed that radicalization has a statistically significant positive relationship with the perception of poor economic prospects, individual relative deprivation, perceived injustice, perceived inequality, gender, and marital status. The results of the OLS model are given in Appendix 4. However, Hansen’s (Citation2000) method provides more nuanced conclusions, as discussed in the following sections.

6.1. Economic prospects

The respondents’ perception of poor economic prospects is measured using three survey questions/items. The first of these items is drawn from Rink and Sharma (Citation2018), while the rest are designed specifically for this study. Responses to these questions were obtained on a five-point Likert scale which ranged from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. All three items are combined and standardized to create the index of poor economic prospects (Cronbach’s alpha: .48). The survey questions are given in Appendix 1.

Table indicates that the perception of poor economic prospects has a statistically significant positive relationship with radicalization only above the religiosity threshold. This supports the hypothesis of this study that poor economic prospects fosters radicalization only in highly religious individuals. This loosely relates to Freytag et al. (2011), who studied the determinants of terrorism in 110 countries and found that depressed socioeconomic conditions reduce the opportunity costs of terrorism and are thus instrumental in catalyzing terrorism.

6.2. Political marginalization

Political marginalization is measured using three survey questions adapted from Rink and Sharma (Citation2018). Responses to both items were obtained on a five-point Likert scale which ranged from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. These two items are combined and standardized to create the political marginalization index (Cronbach’s alpha: .18). The survey questions are given in Appendix 1.

Table indicates that political marginalization lacks a statistically significant relationship with radicalization below and above the religiosity threshold. This finding is in line with Rink and Sharma (Citation2018), who found a null relationship between political marginalization and radicalization in Kenya. It contests Rathore and Basit (Citation2010), Basit (Citation2015), and Naseer et al. (Citation2019), who argued that political marginalization is a crucial driver of radicalization in Pakistan.

6.3. Relative deprivation

Individual relative deprivation is measured using six survey questions adapted from Doosje et al. (Citation2013). Responses to these questions were obtained on a five-point Likert scale which ranged from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. All six items are combined and standardized to create the individual relative deprivation index (Cronbach’s alpha: .85). Likewise, collective relative deprivation is also measured using six questions adapted from Doosje et al. (Citation2013). Responses to these questions were obtained on a five-point Likert scale which ranged from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. All six items are combined and standardized to create the collective relative deprivation index (Cronbach’s alpha: .87). The survey questions are given in Appendix 1.

Table shows that individual relative deprivation has a statistically significant positive relationship with radicalization only above the religiosity threshold, indicating that relative deprivation drive radicalization only in highly religious individuals. This is in line with the relative deprivation hypothesis of Gurr (Citation2015), which considers relative deprivation to be an important impetus for political violence. It also supports the propositions of Khan and Kiran (Citation2012) and Khan and Ahmed (Citation2017b), who considered deprivation a major cause of radicalization in Pakistan.

On the other hand, a statistically significant negative relationship is detected between collective relative deprivation and radicalization below the religiosity threshold. From this, it could be deduced that for less religious individuals, collective relative deprivation does not act as a catalyst for radicalization.

6.4. Injustice

The perception of injustice is measured using seven survey questions adapted from Doosje et al. (Citation2013). Responses to all these questions were obtained on a five-point Likert scale which ranged from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. All seven items are combined and standardized to create the perceived injustice index (Cronbach’s alpha: .80). The survey questions are given in Appendix 1.

Table indicates that perceived injustice has a statistically significant positive relationship only above the religiosity threshold, indicating that injustice catalyzes radicalization only in sufficiently religious people. This relates to Doosje et al. (Citation2013) and Pauwels and Heylen (Citation2017), who found perceived injustice significantly related to radicalization in Dutch and Belgian samples, respectively. It also supports Hussain et al. (Citation2014), Khan (Citation2015), and Tanoli (Citation2018), who considered injustice as an important cause of radicalization in Pakistan.

6.5. Exclusion

The respondents’ perception of exclusion is measured using six survey questions adapted from Rich et al. (Citation2013). Responses to all these questions were obtained on a five-point Likert scale which ranged from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. All six items are combined and standardized to create the exclusion index (Cronbach’s alpha: .87). The survey questions are given in Appendix 1.

Table indicates that exclusion lacks a statistically significant relationship with radicalization below and above the religiosity threshold. Therefore, this study departs from Renström et al. (Citation2020) and Bäck Emma et al. (Citation2018), who found exclusion and radicalization empirically related.

6.6. Inequality

The respondents’ perception of socioeconomic inequality is measured using five survey questions specifically designed for this study. Responses to all these questions were obtained on a five-point Likert scale which ranged from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. All five items are combined and standardized to create the inequality index (Cronbach’s alpha: .48). The survey questions are given in Appendix 1.

Table indicates that perceived inequality has a statistically significant positive relationship with only above the religiosity threshold. This suggests that inequality drives radicalization only in highly religious individuals. This finding supports the propositions of Azam and Aftab (Citation2009) and MALIK (Citation2009), who in their theoretical studies, considered inequality to be an important driver of militancy in Pakistan.

6.7. Oppression

Perceived oppression is measured using 10 survey questions adapted from Lobato (Citation2017). Responses to all these questions were obtained on a five-point Likert scale which ranged from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. All 10 items are combined and standardized to create the perceived oppression index (Cronbach’s alpha: .92). The survey questions are given in Appendix 1.

Table indicates that perceived oppression has a statistically significant negative relationship with radicalization only above the religiosity threshold. This means that oppression reduces the likelihood of radicalization in highly religious individuals. This is in line with the widely held belief among Muslims that considers oppression a test of faith from Allah, which entails great rewards for steadfastness. The Quran mentions that Allah will reward the oppressed in the hereafter if they maintain righteousness while suffering and pardon the oppressor instead of retribution (Vasegh, Citation2009). Likewise, the HadithsFootnote5 also promise significant rewards in the hereafter for facing oppression, such as loading the sins of the oppressed onto the oppressor (al-Bukhari, Citation846). This suggests that highly religious individuals may find greater meaning in oppression.

6.8. Sociodemographic controls

Among the sociodemographic controls, gender has a statistically significant positive coefficient only above the religiosity threshold in Table . This means that highly religious men are more prone to radical world views. Conversely, age lacks a statistically significant relationship with radicalization below and above the religiosity threshold. All the participants of the study are university-going undergrad students. Studying at the university allows individuals to form pro-social bonds as well as improve future prospects. These reasons may have rendered the effect of younger age less effective on the prospects of becoming radicalized. Moreover, marital status has a statistically significant positive relationship with radicalization only above the religiosity threshold. This implies that for highly religious couples, the marital relationship act as a mutually reinforcing echo chamber for transmitting concerns, ideology, and dissent. Marriage allows couples to push each other to think and act more radically than each would do on their own (Alexander, Citation2015). Family size has a statistically significant positive relationship with radicalization only below the religiosity threshold. This relates to Rodermond and Weerman (Citation2021), who studied the impact of family characteristics on susceptibility to terrorism using data of 226 individuals suspected of terrorist intent in the Netherlands. They found that terrorist suspects, on average, come from larger families than individuals from the rest of the population. The current study finds that susceptibility to radicalization prevails only in less religious larger families. It is intuitive to assume that highly religious families are more tightly knitted since they are generally concerned about transmitting their ideology and groupthink, ensuring control and integration. Conversely, families with large size and lower religiosity indicate lower parental control and commitment, thereby increasing the risk of radicalization. Finally, income has a statistically significant negative relationship with radicalization only above the religiosity threshold. This suggests that economic improvements decrease the likelihood of radicalization even in highly religious individuals.

6.9. Robustness check

As a robustness check, Model 2 is re-estimated by adding religiosity as both threshold and explanatory variable. Religiosity is measured using the two-item scale adapted from Rink and Sharma (Citation2018). These two items are combined and standardized to create the religiosity index (Cronbach’s alpha: .03). The survey questions are given in Appendix 1.

The existence of the threshold effect is also confirmed in this specification, as shown in Appendix 5. The results are given in Appendix 6. Compared to the previous results (i.e., Table ), this specification brings no new insights. The only changes that occur are in the linear regression. For instance, in the linear regression, perceived inequality now has a statistically significant positive relationship with radicalization. Conversely, family income is negatively related to radicalization. Moreover, marital status now lacks a statistically significant relationship with radicalization. However, linear regression is not the main focus of this study. On the other hand, no major change is detected in the threshold regression, and results remain nearly the same in terms of signs and statistical significance. The only exception is religiosity, which as an explanatory variable, has a statistically significant negative relationship with radicalization only above the threshold value. This suggests that higher religiosity tends to instill greater tolerance among individuals. This is in line with Clingingsmith et al. (Citation2009), who observed greater tolerant and peaceful attitudes in Pakistani Muslims after they performed Hajj,Footnote6 an indicator of serious devotion and adherence to religion.

6.9.1. Squared terms

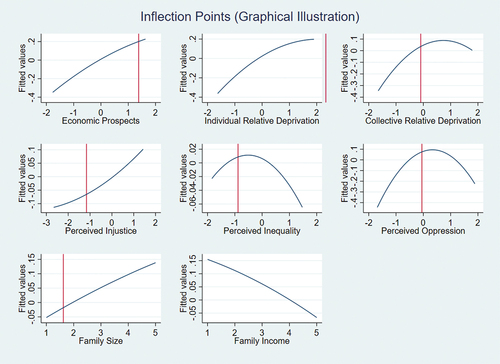

As a robustness check for non-linearity, squared terms are added in the linear regression for all the variables with thresholds. Squared terms allow for checking the existence of switch points in quadratic relationships. The table in Appendix 7 confirms the presence of such switch points, which are called inflection points. These are also shown graphically in Appendix 8. However, since squared terms capture only one type of switch point (i.e., inflection points), therefore Hansen (Citation2000) is preferred since it can detect more than one type of unknown switch points (Arin et al., Citation2021).

7. Discussion and conclusion

This study tests the relationship between socioeconomic factors and radicalization using survey data from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. The study finds a statistically significant positive relationship between radicalization and the indicators of the individual level socioeconomic conditions, such as the perceptions of economic prospects, individual relative deprivation, injustice, and inequality above the religiosity threshold. These findings indicate that socioeconomic hardships (or the perception of these) drive radicalization only in sufficiently religious people. Moreover, the study detects a statistically significant negative relationship between family income and radicalization. This implies that apart from security-centric approaches, radicalization can also be deterred by increasing the opportunity costs of political violence through socioeconomic improvements. Moreover, promoting balanced and diverse religious views may also help check the radicalization process. Apart from these main findings, two takeaways from the results merit discussion.

First, as discussed above, the study detects a positive relationship between radicalization and the perceptions of poor economic prospects, relative deprivation, injustice, and inequality only above the religiosity threshold. The participants of this study come from a region that exhibits a dismal state of aggregate socioeconomic conditions and a high degree of religious violence, as outlined in Section 2. Hence, it can be argued that a mutually constitutive relationship may exist between regional contextual factors and individual perceptions. This relates to Federico and Malka (Citation2018) and Jasko et al. (Citation2020), who argued that the relationship between individual-level variables and political beliefs is moderated by the surrounding social context. This suggests that policies that foster regional development, diversity, and inclusion may also reduce the risk of radicalization. The significance of socioeconomic factors above the religiosity threshold also indicates that their relationship with radicalization is far from simple, and therefore needs further investigation through future research.

Second, the study finds that the explanatory variables are associated with the outcome variable in a threshold-dependent way. The threshold parameter (i.e., religiosity) acts as a change point, enabling the modeling of the non-linearity in the relationship between radicalization and independent variables. From this, it can be deduced that instead of religiosity per se, a certain degree of religious adherence may be required to subscribe to the mental rewards of religiously motivated political violence while facing economic hardships.

For future research, two possible directions are suggested. First, this study tests the relationship between radicalization and perceived socioeconomic conditions. Hence, it furnishes evidence on the link between socioeconomic factors and support for political violence from the micro perspective. However, the aggregate/regional socioeconomic conditions may greatly influence these individual-level perceptions. Since the current study is based on individual-level/micro data from a single region, it cannot capture the effect of aggregate socioeconomic factors on individual (radical) perceptions. To better understand the impact of the context on the individuals, future studies may combine the micro data of individual-level support for violent groups/acts with indicators of aggregate socioeconomic conditions. Second, to test the generalizability of these results, future studies may empirically test the framework of this paper in other regions with considerable degrees of religious radicalization.

Submission

This manuscript is submitted to Cogent Social Sciences.

Appendices.docx

Download MS Word (265.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Professor Dr. Marcel Thum, Faculty of Business and Economics, Technische Universität Dresden (TUD), for reading several drafts of this paper and providing useful comments, suggestions, advice, and encouragement. The author is also grateful to Professor Dr. Kerim Peren Arin, Zayed University Abu Dhabi, for providing valuable advice and comments on the methodological aspects of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2286042

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fahim Nawaz

Fahim Nawaz was a doctoral candidate and scholarship holder at the Dresden Leibniz Graduate School (DLGS), which is a joint interdisciplinary facility of the Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development (IOER), and the Technische Universität Dresden (TUD), Germany. He currently works as a Lecturer at the Department of Economics, University of Peshawar, Pakistan

Notes

1. Before applying the method developed by Hansen (Citation2000), squared terms were added in the linear regression which confirmed the existence of inflection points. However, squared terms capture only one type of switch point (i.e., inflection points), therefore Hansen (Citation2000) is preferred since it can detect more than one type of unknown switch points. The results of the regression with squared terms in given in Appendix 7.

2. North-West Frontir Province.

3. A term used by Muslims in religious context for individuals engaged in a holy struggle for serving Islam, such as Jihad.

4. The procedure employed here involves adding the scores of all items and then dividing them by the number of items inovled in creating the index.

5. Hadiths refer to the sayings and traditions of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad. Hadiths are considered an important source of Shariah (Islamic law), ranking second only to the Quran.

6. Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca.

References

- Ahmad, M. (2013). Insurgency in FATA: Causes and a way forward. Pakistan Annual Research Journal, 49, 11–44. http://pscpesh.org/PDFs/PJ/Volume_49/02-Insurgency%20in%20FATA%20by%20Manzoor%20Ahmad.pdf

- Ahmed, Z. S., Yousaf, F., & Zeb, K. (2018). Socio-economic and political determinants of terrorism in Pakistan: University students’ perceptions. International Studies, 55(2), 130–145. SAGE Publications India https://doi.org/10.1177/0020881718790689

- Al-Bukhari, M. I. I. A. (846). Sahih Al-Bukhari (Vol. 3). https://www.sahih-bukhari.com/Pages/Bukhari_3_43.php

- Alexander, A. (2015). “Couples make each other more radical. That’s very bad for fighting terrorism.” The Washington Post, December 21. https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/12/23/couples-make-each-other-more-radical-thats-very-bad-for-fighting-terrorism/.

- Al-Saggaf, Y. (2016). Understanding online radicalisation using data science. International Journal of Cyber Warfare and Terrorism, 6(4), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCWT.2016100102

- Andreas, F., Krüger, J. J., Meierrieks, D., & Schneider, F. (2011a). The origins of terrorism: Cross-country estimates of socio-economic determinants of terrorism. European Journal of Political Economy, 27(December), S5–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2011.06.009. Special Issue:Terrorism.

- Andreas, F., Krüger, J. J., Meierrieks, D., & Schneider, F. (2011b). The origins of terrorism: Cross-country estimates of socio-economic determinants of terrorism. European Journal of Political Economy, 27(December), S5–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2011.06.009. Special Issue:Terrorism.

- Arin, P., Minniti, M., Murtinu, S., & Spagnolo, N. (2021), December. Inflection points, kinks, and jumps: A statistical approach to detecting nonlinearities. In Organizational research methods, p. 10944281211058466. SAGE Publications Inc, https://doi.org/10.1177/10944281211058466.

- Azam, M., & Aftab, S. (2009). Inequality and the militant threat in Pakistan. Pakistan Institute for Peace Studies.

- Azman-Saini, W. N. W., Hook Law, S., & Halim Ahmad, A. (2010). FDI and economic growth: New evidence on the role of financial markets. Economics Letters, 107(2), 211–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2010.01.027

- Bäck Emma, A., Hanna, B., Niklas, A., & Holly, K. (2018). The quest for significance: Attitude adaption to a radical group following Social exclusion. In H. Scheithauer, V. Leuschner, N. Böckler, B. Akhgar, & H. Nitsch (Eds.), International Journal of developmental Science12 (1–2) (pp. 25–36). https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-170230

- Basit, A. (2015). Countering violent extremism: Evaluating Pakistan’s Counter-radicalization and de-radicalization initiatives. IPRI Journal, 15(2), 44–68.

- Bélanger, J. J., Moyano, M., Muhammad, H., Richardson, L., Lafrenière, M.-A. K., McCaffery, P., Framand, K., & Nociti, N. (2019). Radicalization leading to violence: A test of the 3N model. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(February), 42. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00042

- Beller, J., & Kröger, C. (2018). Religiosity, religious fundamentalism, and perceived threat as predictors of Muslim support for extremist violence. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 10(4), 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000138

- Bergen Diana, D., van Allard, F., Feddes, B. D., & Pels, T. V. M. (2015). Collective identity factors and the attitude toward violence in defense of ethnicity or religion among Muslim youth of Turkish and Moroccan descent. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 47(July), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.026

- Bhui, K., Warfa, N., Jones, E., & Dang, Y.-H. (2014). Is violent radicalisation associated with poverty, migration, poor self-reported health and common mental disorders? PloS One, 9(3), e90718. Public Library of Science: e90718 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090718

- Blair Graeme, C., Fair, C., Malhotra, N., & Shapiro, J. N. (2013). Poverty and support for militant politics: Evidence from Pakistan: POVERTY and SUPPORT for MILITANT POLITICS. American Journal of Political Science, 57(1), 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00604.x

- Ceder, L.-E., Weidmann, N. B., & Skrede Gleditsch, K. (2011). Horizontal inequalities and ethnonationalist Civil war: A global comparison. The American Political Science Review, 105(3), 478–495. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055411000207

- Chepkong’a, M. (2020). Community policing: An approach for Countering youth radicalization in Eastleigh area of Nairobi County. East African Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 2(September), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.37284/eajis.2.1.212

- Choi, S.-W., & Piazza, J. A. (2016). Ethnic groups, political exclusion and domestic terrorism. Defence and Peace Economics, 27(1), 37–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2014.987579

- Clingingsmith, D., Ijaz Khwaja, A., & Kremer, M. (2009). Estimating the impact of the hajj: Religion and tolerance in Islam’s global gathering*. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1133–1170. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.3.1133

- Coid, J. W., Bhui, K., MacManus, D., Kallis, C., Bebbington, P., & Ullrich, S. (2016). Extremism, religion and psychiatric morbidity in a population-based sample of young men. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(6), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.186510

- Crossett, C., & Spitaletta, J. A. (2010). Radicalization: Relevant psychological and sociological concepts. US army asymmetric warfare group. Prepared by the John Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory, 10–11. https://info.publicintelligence.net/USArmy-RadicalizationConcepts.pdf

- Dalacoura, K. (2006). Islamist terrorism and the Middle East democratic deficit: Political exclusion, repression and the causes of extremism. Democratization, 13(3), 508–525. Routledge https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340600579516

- Dawn. 2017. “Extremism in Universities.” DAWN.COM. July 17. https://www.dawn.com/news/1345738.

- Dawson, L. L. (2018). Debating the role of religion in the motivation of religious terrorism. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society, 31(2), 98–117. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1890-7008-2018-02-02

- Delavande, A., & Zafar, B. (2015). Stereotypes and madrassas: Experimental evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 118(October), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.03.020

- Delia Deckard, N., & Jacobson, D. (2015). The prosperous hardliner: Affluence, fundamentalism, and radicalization in Western European Muslim communities. Social Compass, 62(3), 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0037768615587827

- Doosje, B., Loseman, A., & van den Bos, K. (2013). Determinants of radicalization of Islamic youth in the Netherlands: Personal uncertainty, perceived injustice, and perceived group threat. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 586–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12030

- Fair, C., Christine, N. M., & Jacob, N. S. (2012). Faith or doctrine? Religion and support for political violence in Pakistan. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(4), 688–720. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs053

- Federico, C. M., & Malka, A. (2018). The contingent, contextual nature of the relationship between needs for security and certainty and political preferences: Evidence and implications. Political Psychology, 39(S1), 3–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12477

- Firdous, M. A. (2017). Counterterrorism in cyberspace. CISS Insight Journal, 5(4), 43–61.

- Franc, R., & Pavlović, T. (2021). Inequality and radicalisation - systematic Review of quantitative studies. Terrorism and Political Violence, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2021.1974845

- Groppi, M. (2018). Islamist Radicalisation in Italy: Myth or nightmare?: An empirical analysis of the Italian case study. King’s College London.

- Gunaratna, R., & Nielsen, A. (2008). Al Qaeda in the tribal areas of Pakistan and beyond. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 31(9), 775–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100802291568

- Gurr, T. R. (2015). Why men rebel. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315631073

- Hansen, B. E. (2000). Sample splitting and threshold estimation. Econometrica, 68(3), 575–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00124

- Hansen, H. E., Nemeth, S. C., & Mauslein, J. A. (2020). Ethnic political exclusion and terrorism: Analyzing the local conditions for violence. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 37(3), 280–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894218782160

- Holla, A. B. (2020). Marginalization of ethnic communities and the rise in radicalization. Traektoriâ Nauki= Path of Science, 6(7). https://doi.org/10.22178/pos.60-7

- Hussain, S., Hussain, B., Zada Asad, A., & Khan, W. (2014). Theoretical analysis of socio-economic and political causes of terrorism in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Criminology, 6(2), 53.

- Imran, M. (2019, March 20). Bahawalpur student stabs Professor to death over ‘anti-Islam’ remarks. DAWN.COM. https://www.dawn.com/news/1470814

- Iqbal, K., & Mehmood, Z. (2021). Emerging trends of on-campus radicalization in Pakistan. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism, 16(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/18335330.2021.1902551

- James, K., & Dawson, L. L. (2023, March). Understanding involvement in terrorism and violent extremism: Theoretical integration through the ABC model. Terrorism and Political Violence, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2023.2190413

- Jasko, K., Webber, D., Kruglanski, A. W., Gelfand, M., Taufiqurrohman, M., Hettiarachchi, M., & Gunaratna, R. (2020). Social context moderates the effects of quest for significance on violent extremism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(6), 1165–1187. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000198

- Khan, A. U. (2015). De-radicalization of Pakistani society. Journal of Research in Social Sciences, 3(2), 55.

- Khan, G., & Ahmed, M. (2017a). Socioeconomic deprivation, fanaticism and terrorism: A case of Waziristan, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of History and Culture, 38(2), 65–83. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Manzoor-Ahmed-19/publication/330874023_Socioeconomic_Deprivation_Fanaticism_and_Terrorism_A_Case_of_Waziristan_Pakistan/links/5c5950b2299bf12be3fd2a48/Socioeconomic-Deprivation-Fanaticism-and-Terrorism-A-Case-of-Waziristan-Pakistan.pdf

- Khan, G., & Ahmed, M. (2017b). Socioeconomic Deprivation, Fanaticism and Terrorism: A Case of Waziristan, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of History and Culture, 38(2), 65–83.

- Khan, K., & Kiran, A. (2012). Emerging tendencies of radicalization in Pakistan. Strategic Studies, 32(2/3), 20–43.

- Khan, Z., & Ullah, R. (2018). Historical roots of radicalization in Pashtun’s society. Al-Idah, 36(2), 59–65.

- Law, S. H., Azman-Saini, W. N. W., & Ibrahim, M. H. (2013). Institutional quality thresholds and the finance – growth nexus. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(12), 5373–5381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.03.011

- Lehmann, T. C., & Tyson, S. A. (2022). Sowing the seeds: Radicalization as a political Tool. American Journal of Political Science, 66(2), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12602

- Lindekilde, L., Bertelsen, P., & Stohl, M. (2016). Who goes, why, and with what effects: The problem of foreign fighters from Europe. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 27(5), 858–877. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2016.1208285

- Lobato, R. M. (2017, September). Cuestionario de Opresión Percibida Reducido (R-OQ).

- Macdougall, A. I., van der Veen, J., Feddes, A. R., Nickolson, L., & Doosje, B. (2018). Different strokes for different folks: The role of psychological needs and other risk factors in early radicalisation. In H. Scheithauer, V. Leuschner, N. Böckler, B. Akhgar, & H. Nitsch (Eds.), International journal of developmental science (pp. 37–50). https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-170232

- MALIK, S. M. (2009). Horizontal inequalities and violent Conflict in Pakistan: Is there a link? Economic and Political Weekly, 44(34), 21–24. Economic and Political Weekly.

- Manuel, M., & Trujillo, H. M. (2014). Intention of Activism and Radicalism among Muslim and Christian Youth in a Marginal Neighbourhood in a Spanish City/Intención de Activismo y Radicalismo de Jóvenes Musulmanes y Cristianos Residentes En Un Barrio Marginal de Una Ciudad Española. Revista de Psicología Social, 29(1), 90–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02134748.2013.878571

- McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2008). Mechanisms of political radicalization: Pathways toward terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 20(3), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546550802073367

- Meierrieks, D., Krieger, T., & Klotzbücher, V. (2021). Class warfare: Political exclusion of the poor and the Roots of Social-Revolutionary terrorism, 1860-1950. Defence and Peace Economics, 32(6), 681–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2021.1940456

- Milla, M., Noor, F., & Ancok, D. (2013). The impact of Leader–follower interactions on the radicalization of terrorists: A case study of the bali bombers. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 16(2), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12007

- Naseer, R., Amin, M., & Maroof, Z. (2019). Countering violent extremism in Pakistan: Methods, challenges and theoretical underpinnings. NDU Journal, 33, 100–116.

- Naz, A., Khan, W., Daraz, U., Hussain, M., & Khan, T. (2013). Militancy: A myth or reality - an exploratory study of the socio-economic and ReligiousForces Behind Militancy in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Bangladesh E-Journal of Sociology, 10(2), 25–40. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Arab-Naz/publication/283243328_Militancy_A_Myth_or_Reality_An_Exploratory_Study_of_the_Socio-economic_and_Religious_Forces_Behind_Militancy_in_Khyber_Pakhtunkhwa_Pakistan/links/562ee45d08ae518e348388e8/Militancy-A-Myth-or-Reality-An-Exploratory-Study-of-the-Socio-economic-and-Religious-Forces-Behind-Militancy-in-Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa-Pakistan.pdf

- Obaidi, M., Bergh, R., Akrami, N., & Anjum, G. (2019). Group-based relative deprivation Explains endorsement of extremism among Western-Born Muslims. Psychological Science, 30(4), 596–605. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619834879

- Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. (2021). Global MPI country briefing 2021: Pakistan (South Asia). University of Oxford. https://ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/CB_PAK_2021.pdf

- “Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.”. 2017. Final Results (Census-2017). https://www.pbs.gov.pk/content/population-census.

- Panayotov, B. (2019). Crime and Terror of Social exclusion: The case of 13 imams in Bulgaria. European Journal of Criminology, 16(3), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370819829650

- Papageorgiou, C. (2002). Trade as a threshold variable for multiple regimes. Economics Letters, 77(1), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1765(02)00114-3

- Pasha, H. A. (2021). Charter of the Economy: Agenda for economic reforms in Pakistan. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES). https://pakistan.fes.de/e/charter-of-the-economy

- Pauwels, L. J. R., & Heylen, B. 2017, June. Perceived group threat, perceived injustice, and self-reported right-wing violence: An Integrative Approach to the explanation right-wing violence. In Journal of interpersonal violence, p. 0886260517713711. SAGE Publications Inc, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517713711.

- Pearson, E. (2016). The case of Roshonara Choudhry: Implications for theory on online radicalization, ISIS women, and the gendered Jihad: Gender and online radicalization. Policy & Internet, 8(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.101

- Rathore, M., & Basit, A. (2010). Trends and patterns of radicalization in Pakistan. Conflict and Peace Studies, 3(2), 15–32.

- Renström, E. A., Bäck, H., & Knapton, H. M. (2020). Exploring a pathway to radicalization: The Effects of Social exclusion and rejection sensitivity. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 23(8), 1204–1229. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220917215

- Rich, G., Adrienne Carter-Sowell, C. N. D., Ryan, E. A., Carboni, I., & Carboni, I. (2013). Validation of the Ostracism Experience Scale for Adolescents. Psychological Assessment, 25(2), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030913

- Rink, A., & Sharma, K. (2018). The determinants of religious radicalization: Evidence from Kenya. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(6), 1229–1261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002716678986

- Rodermond, E., & Weerman, F. (2021). The families of Dutch terrorist suspects: Risk and protective factors among parents and siblings. Monatsschrift für Kriminologie und Strafrechtsreform, 104(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1515/mks-2021-0133. De Gruyter.

- Schils, N., & Verhage, A. (2017). Understanding How and why young people enter radical or violent extremist groups. International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV), 11(June), a473–a473. https://doi.org/10.4119/ijcv-3084

- Singay, K. A. (2020). Social Marginalisatin and Scapegoating: A Study of Mob Lynching in Pakistan and India. Pakistan Social Sciences Review, 4(2), 526–536. https://doi.org/10.35484/pssr.2020(4-II)42

- South Asia Terrorism Portal. (2022). https://www.satp.org/

- Tanoli, F. (2018). SOCIO-ECONOMIC FACTORS BEHIND RADICALIZATION: EVIDENCE FROM PAKISTAN. NDU Journal, 32(January), 80–88.

- Van Brunt, B. Murphy, A. & Zedginidze, A. (2017). An exploration of the risk, protective, and mobilization factors related to violent extremism in college populations. Violence and Gender, 4(3), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2017.0039

- Vasegh, S. (2009). Psychiatric treatments involving religion: Psychotherapy from an Islamic perspective. In H. G. Koenig & P. Huguelet (Eds.), Religion and spirituality in psychiatry (pp. 313–314). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511576843.020

- Wahab, S., & Hussain, A. (2021). Causes & consequences of terrorism in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. International Journal of Research, 8(2), 234–245.

- Wahl, F. (2019). Political participation and economic development. Evidence from the rise of participative political institutions in the late Medieval German lands. European Review of Economic History, 23(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/ereh/hey009

- Wilner, A. S., & Dubouloz, C.-J. (2010). Homegrown terrorism and transformative learning: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Understanding radicalization. Global Change, Peace & Security, 22(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781150903487956

- Yilmaz, I., & Shakil, K. 2022. “Religious Populism and Vigilantism: The Case of the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan.” Deakin University.

- Yousaf, F. (2019). Counter-terrorism in Pakistan’s ‘tribal’ districts. Peace Review, 31(4), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2019.1800940

- Yusuf, M. (2008). Prospects of youth radicalization in Pakistan. The Saban Center for Middle East Policy at BROOKINGS, 14(7), 1–27.

- Zahid, F. (2015). Tahir Saeen Group: Higher-Degree Militants. Pak Institute for Peace Studies.

- Zeb, K., & Shahab Ahmed, Z. (2019). Structural violence and terrorism in the federally administered tribal areas of Pakistan. Civil Wars, 21(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2019.1586334

Appendix 1:

Questionnaire/Survey Instrument

Dear Participant,

This survey will be used in a university research project purely for academic purposes. Your participation is completely voluntary, and you will not be asked for personal information like your name, address, etc. Please note that your responses will not be shared with anyone else. We will be thankful for your participation.

Sociodemographic Controls

Radicalization

Instruction: For each of the statements below, please indicate how much you agree or disagree by choosing the appropriate option using (✓).

1=Strongly Disagree 2=Disagree 3=Undecided 4=Agree 5=Strongly Agree

Economic Prospects

Instruction:

The statements given below relate to your perception regarding yourself in various situations. You are requested to tell us how much you agree or disagree by choosing the appropriate option using (✓).

1=Strongly Disagree2=Disagree3=Undecided4=Agree5=Strongly Agree

Political Marginalization

1=Strongly Disagree 2=Disagree 3=Undecided 4=Agree 5=Strongly Agree

Individual Relative Deprivation

1=Strongly Disagree 2=Disagree 3=Undecided 4=Agree 5=Strongly Agree

Collective Relative Deprivation

Injustice

Exclusion

Inequality

Oppression

Religiosity

1. If you had to choose one label to describe yourself from the following options, which would it be?

Male

Female

Muslim

Caste/Tribe

Pakistani

2. How often do you visit your place of worship to offer prayers?

Daily

Weekly

Monthly

Sometimes

Rarely

Appendix 2:

Descirptive Statistics

Appendix 3:

Pairwise Correlation Results

Appendix 4:

Linear Regression

Appendix 5:

Threshold Test (Robustness Check)

Appendix 6:

Threshold Regression (Robustness Check)

Appendix 7:

Linear Regression with Squared Terms and Inflection Points

Appendix 8:

Inflection Points (Graphical Illustration)