Abstract

This exploratory inquiry examined how a recent national external staff audit carried out on behalf of the Ghanaian government is perceived by the teaching staff of Ghanaian Technical Universities (TUs); particularly, in terms of the assessors, the assessment processes, and the effects on the TUs and the individual staff within them. The population for the study was all the teaching staff of the TUs. However, a total number of 212 teaching staff from seven out of the eight TUs in the country were selected to answer the semi-structured questionnaire using simple stratified random sampling techniques. The quantitative data was evaluated using descriptive statistics and factor analysis while the qualitative data was analyzed using thematic analysis. The quantitative and qualitative results were then triangulated at the discussion section. The main highpoints of the study were that the assessors were definitely not from the (sister) TUs and that their neutrality and training could not be guaranteed. Of course, the audit led to a new sense of concern for enhancing teaching, learning, research; and an increase in the number of policies, higher qualifications and promotions. Nevertheless, it impacted negatively on the health, job satisfaction and social life of individual staff. For policy makers and practitioners, the importance of extensive consultations with stakeholders for instance, in the selection of assessors, standards and the realism of an appropriate level of compliance is suggested.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The Ghanaian government has been keenly interested in higher education quality especially, within the Technical Universities (TUs) space. This interest stems from the recognition that, strengthening Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) is the key to meeting the technical and skilled human resource needs of the country; a key objective of the industrial development agenda of the country (Ansah & Ernest, Citation2013). Accordingly, the government through the National Council for Tertiary Education (NCTE), mandated to advise and recommend to the Minister of Education, national standards and norms on staff, conducted a staff audit in all newly converted Ghanaian TUs from the 3rd – 14th of October, 2018. Although the exercise was part of efforts meant to migrate staff of the TUs onto the conditions of service for public universities; it was also, aimed at enhancing quality within the TUs. This study therefore, looked into how the NCTE’s staff audit was viewed by the teaching staff of the Technical Universities in terms of the inputs and the processes (e.g., the assessors, standards, transparency, involvement) and its impact on both the TUs (e.g., policies, staff unrest, cost) and the individuals (health, social life, promotions) within them.

1. Introduction

External Quality Assessment (EQA) continues to be used in universities worldwide despite strong criticisms and advocacies against it (Cooper & Poletti, Citation2011; Houston & Paewai, Citation2013). The three most popular methods of gauging the quality of higher education (HE) across time have been quality assurance, quality control, and quality audit (Tam, Citation2000). In order to ascertain whether or not accepted standards of education, scholarship, and infrastructure are being fulfilled, maintained, and improved, an institution or programme must undergo a structured and systematic evaluation process known as quality assurance (QA), according to Materu (Citation2007, p. 3). Quality control refers to a system used to determine if delivered goods or services meet predetermined standards. However, it ignores the notion that total quality extends beyond pupils and focuses primarily on students (Frazer, Citation1992). On the other hand, a quality audit can be described as a systematic and independent examination to determine whether quality activities and results comply with planned arrangements and whether these arrangements are implemented effectively and/or are suitable for achieving objectives (Shah, Citation2012). The interest of this study however lies in quality control given the context of this study and the fact that, external audit is often used across the world to improve quality, transparency in the use of public funding and accountability in higher education. Woodhouse (Citation2003) further acmes the following as the basis for external quality audits, the need to:

Establish and maintain a framework of qualifications;

Steer higher education institution in particular directions;

Provide a report on the higher education institution as a basis for (government) funding;

Check the institution’s compliance with legal and other requirements (compliance).

Advocates of External Quality (EQ) mechanisms reason that they make significant positive contributions toward quality by engendering: Information on quality/standards to the public, public accountability (standards achieved for the use of public money) and planning processes in HE. They further claim that recommendations made may stimulate internal responses (Billing, Citation2004; Carr et al., Citation2005). These notwithstanding, external quality mechanisms have strongly been criticized, with some advocating for its abolishment because of the perception that the government uses them to “intervene in matters of institutional autonomy by setting rules and defining how institutions should be governed” (Huisman, Citation2007). No wonder most teaching staff see external quality measures as an indictment on their autonomy (Carr et al., Citation2005). Besides, such exercises are often seen as time-consuming, arrogantly bureaucratic and an attempt to impose its will on HE institutions (Akalu, Citation2014; Ryan, Citation2015). Evidence in support of the view that EQ mechanisms improves quality on the other hand has been scarce. A literature search shows that, empirical research on external quality audit and staff audit in particular have remained very few worldwide and almost none existent in the Ghanaian tertiary context (Carr et al., Citation2005; Cheng, Citation2010, Citation2011; Shah, Citation2012). What is further interesting is that, most previous studies in this respect have largely focused on the overall impact of the value of the audit on institutions (transformation, improvement) or changes in teaching and learning rather than its effect on the individuals within them (Fourie & Alt, Citation2000; Ryan, Citation2015). For these reasons, the current inquiry investigated how the recent staff audit carried out by the NCTE is viewed by staff of the Technical Universities, the factors that probably, account for their views; and the effect of the exercise on both the institutions and their teaching staff. The research questions guiding the study were:

How was the staff audit conducted by the NCTE viewed by the TUs and their teaching staff, and what factors possibly, informed their views?

What were the associated individual and institutional effects and challenges?

Overall, this study is expected to provide evidence on how external quality assessment mechanisms such as a staff audit is viewed by staff of Ghanaian TUs and the possible factors that inform their acceptance or rejection of the recommended quality changes. Thus, this study is expected to provide a record of how external audits can affect both institutions and their staff in terms of their work performance in the university setting. To stakeholders in the higher education sector, the study is expected to inform how quality measurement by external or regulatory bodies can be improved to the desired levels while ensuring accountability at the same time.

1.1. Context of the study

The development and utilization of effective approaches to quality management in the Ghanaian tertiary sector was until quite recently, in the hands of the National Accreditation Board (NAB) and the National Council for Tertiary Education (NCTE) legally established (the Provisional National Defense Council Law 317, 1993) to serve as the government’s agency under the Ministry of Education, responsible for the regulation, supervision and the accreditation of tertiary institutions (Abukari & Corner, Citation2010). According to Effah and Mensa-Bonsu (Citation2001), the NAB was specifically, tasked with overseeing the provision of high-quality HE through peer reviews, visits to institutions, and reviews of institutional self-assessment reports; reviewing the quality of programmes, staff, and students; and examining physical facilities like libraries, labs, and lecture halls. The NCTE, on the other hand, was tasked with providing national standards and norms on personnel, costs, accommodations, and time usage as well as monitoring and recommending compliance at the institutional level to the Minister in charge of Education. Currently, the Ghana Tertiary Education Commission (GTEC) made up of the NCTE and the NAB is in charge of higher education. Thanks to the new Education Regulatory Bodies Act, 2020 (Act 1023). The Commission’s goals include, among other things, regulating all types of tertiary education in order to advance:

The provision of consistent quality of services by tertiary institutions in the country and

Advancement and application of knowledge through teaching, scholarly research and collaboration with industry and the public sector.

TVET has been an integral part of Ghana’s education system since the 19th century. In fact, by the year 1925, five technical schools offering courses in woodwork, metalwork and brickwork were already established (Foster, Citation1965). From there, TVET has respectively metamorphosed to technical institutes, non-tertiary and tertiary polytechnics and now technical universities. Per the recommendations of the Technical Committee set up by the government to develop a roadmap for the conversion of the then Polytechnics into Technical Universities (TUs), the TUs are to (1) Have a strong collaboration with industry (a crucial distinguishing feature of the TUs from the traditional universities); (2) Involve industry and employers in their teaching, organization of workplace experiential training for a smooth transition into the world of work (evidenced by signed partnership agreements), (3) Have structured and supervised internships or work place experiential learning for students, and (4) Lead the application of technology in the various fields of learning. Per their mission (Act 745 amended, 2017). The TUs are also, to develop skills in the fields of manufacturing, commerce, science, technology, applied social science and applied arts at various levels including PhDs. In line with this, lecturers in the TUs are to hold both academic (PhD) and professional qualifications and have at least, three years industry experience (Afeti et al., Citation2014).

Since the conversion of the Polytechnics to TUs in 2016, the Ghanaian government has been particularly, attentive to quality in the TUs. This interest stems from the recognition that TVET contributes to national progress. Hence, regulatory bodies have focused on: (a) Helping the TUs sculpt a niche for themselves in their mandated niche areas, instead of mimicking the traditional universities; (b) Improving the public image of TVET and (c) Ensuring that a good and quality foundation is built from the start for TVET. For instance, there has been the general perception that TVET is for the academically poor. As such, some perceive the TUs as “baby universities” or “poor cousins” of the traditional universities (Hayward, Citation2008). These, together with the state’s free Senior High School (SHS) policy which has significantly increased enrolment in the tertiary sector (also in the TUs), have given the Government the obligatory incentive to be interested in quality issues within the TUs. Accordingly, NCTE on behalf of the government conducted a staff audit from 3rd − 14 October 2018 in all newly converted TUs in the country. Although the exercise was part of efforts meant to migrate staff of the TUs onto the conditions of service for public universities; the exercise was also, meant to improve staff quality within the TUs. In the assessment, the NCTE required that, the administration of the TUs (Registrar’s Offices) make available to the audit team for inspection, filled individual staff profile forms (provided by the NCTE) of all staff within the university, their original certificates and transcripts of certificates.

2. Literature review

2.1. Quality and quality assessment in higher education

In general, the concept of quality in education is inexpressible and takes on several interpretations depending on the circumstances. As a result, it has been described using a variety of concepts, including efficacy, efficiency, and/or equity (Abukari & Corner, Citation2010). However, in the context of higher education, it is frequently discussed in terms of how well teaching, research, service, and other fundamental university activities meet societal demands. It is in this sense that quality assessment is viewed as a diagnostic review and evaluation of teaching, learning, and outcomes based on a thorough analysis of curricula, structure, vision/goals, expertise of teaching staff, libraries and laboratories, access to the internet, governance, leadership, relevance, value added, employability, student satisfaction, employer satisfaction, and a host of other factors (Effah & Mensa-Bonsu, Citation2001). Other definitions identify specific indicators that reflect the desired inputs (e.g., responsive faculty and staff) and outputs (e.g., employment of graduates). See Schindler et al. (Citation2015); Tam (Citation2010), also.

When it comes to approaches to quality measurement in HE, the three most dominant approaches are quality control, quality audit and quality assurance. Nonetheless, quality assurance is favoured by many because it is based on the premise that everyone in an organization is responsible for maintaining and enhancing the quality of educational services in an institution (Jingura & Kamusoko, Citation2019; Ryan, Citation2015). Interestingly, global increases in tertiary student numbers have brought about a growing demand for quality assurance (Alves & Tomlinson, Citation2021; Hou et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). This is because QA can be a driver for excellence in HE (Ryan, Citation2015). According to the International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE) QA is the process of establishing stakeholder confidence that, the input, process and the outcomes of an institution, meet minimum expectations or requirements. QA of course, could be an internal or an external evaluation process (Vroeijenstijn, Citation2004). Internal quality evaluations involve quality review processes undertaken within the specifics of institutional context, resources and capacities (Aithal, Citation2015; Paintsil, Citation2016). Institutions become primarily responsible for this by engaging both faculty and administrative staff throughout the process. External quality assurance on the other hand, is a review undertaken by a third-party in order to determine whether agreed or predetermined standards are met (Martin & Stella, Citation2007). Normally, internal QA is considered part of the external QA, as both activities are inextricably interrelated (Hou et al., Citation2018; Vroeijenstijn, Citation2008).

Quality assurance systems in higher education play a key role in supporting and improving the quality of educational services provided by Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). Hence, since the early 1980s, several governments have attempted to give universities more autonomy while directing from a distance (Huisman, Citation2007; Van Vught & Westerheijden, Citation1994). Attacks against institutional autonomy, which is generally understood to represent universities’ freedom to conduct their own affairs without direction, influence, or interference from outside players, particularly, governments, are sometimes hidden under the guise of accountability (Taiwo, Citation2011). In Africa, specifically Ghana, this experience is relatively new, at least practically speaking. But opposition to these outside evaluations persists (Fisher et al., Citation2003; Ryan, Citation2015; Lomas, Citation2003)

2.2 Staff audit

According to Pauli and Pocztowski (Citation2019), a staff audit entails an organised, independent, and thorough investigation into and/or evaluation of the management of human resources from the standpoint of monitoring and adherence to established standards. The overall goal is a complete and exhaustive diagnosis of the situation. This is accomplished through an analysis and assessment of the current situation and the formulation of improving hypotheses (audit’s control function). Next is the identification of procedures and the elimination of phenomena associated with identified deviations (audit’s advisory function) (Lisinski et al., Citation2011). Simply put, staff audit typically provides stakeholders with data on: Employee numbers, categorized by the:

Type of employment e.g., permanent full-time/part-time

Operational or social criteria e.g., location, job title, function, salary grade

Employee skills e.g., an assessment of employee functional or technical skills;

The requirements for staff audit have been justified for a variety of reasons. For example, Jeliazkova and Westerheijden (Citation2002) contend that staff audit is essential when there are significant concerns regarding educational standards, the effectiveness of a higher education system, institutional culture, the capacity for innovation and quality assurance. One cannot, however, overstate the significance of carefully considered and well-developed laws on conflicts of interest and methods to promote openness and uphold the legitimacy of the process. The same is true for the quantity of policies, standards of accountability, how decisions are made, and staff and students’ awareness of their roles in the activity (Carr et al., Citation2005). As stressed by Hayward (Citation2008), the legitimacy of the whole process and its subsequent results depends on:

The fairness, fastness and the efficiency of the entire process.

The severity of externally imposed regulation or conditions and the extent to which compliance work against quality development in the university.

The extent of stakeholder involvement especially, in contentious issues.

The extent to which they foster a new sense improving teaching, learning, research, public service and competition in today’s knowledge environment.

According to Al-Maskari (Citation2014), external quality methods like staff audits are typically used in academic institutions to promote change and enhance teaching and learning. On the impact of staff audit, opinions have remained divided. Positively, more policies that result in greater transparency in university processes are mentioned by Carr et al. (Citation2005). For instance, the University of Otago’s quality management systems were strengthened by the establishment of policies on staff advancement and scholarship development. The newly hired and other staff members for instance, frequently referenced these policies in their day-to-day work (Ryan, Citation2015). According to Carr et al. (Citation2005), management changes, distributed leadership structures, and measures to enhance the university’s academic management and quality systems have all been noted.

In a negative light, staff audit is viewed as not enhancing student learning or helping to improve the institution. For instance, Shah (Citation2012) examined how much external audits had boosted university quality in Australia during the last ten years (from 2001 to 2010). Forty (40) individuals had discussions that formed the basis for the analysis. The study also looked at 60 external quality audit reports and came to the conclusion that while external audits help Australian institutions to improve their HE systems and processes, they do not always result in better student experiences. Cheng (Citation2011) examined the perceived effects of quality audit on academics’ work using interview data from 64 academics and document analysis. The study found that internal audit procedures built within the organisation performed more reliably and effectively than external ones. Cheng (Citation2010) carried out research with scholars from seven English institutions. Through capturing their opinions and experiences with quality audits, the study looked at how the work of academics is affected. The findings of Cheng’s study showed that quality audits continue to be a contentious topic. The audit, in the opinion of two thirds of the respondents, was pointless and cumbersome. According to Cheng, this indicates that academics desire to maintain their independence. In reality, academics frequently show opposition to quality audits and adopt “game-playing” attitudes towards external quality systems due to worries about control and power (Cheng, Citation2010). It is therefore understandable that the academics in Cheng’s study felt no ownership or responsibility for external quality audit processes; and that they had a remote relationship with the EQA authority at their universities.

2.3. Conceptual framework

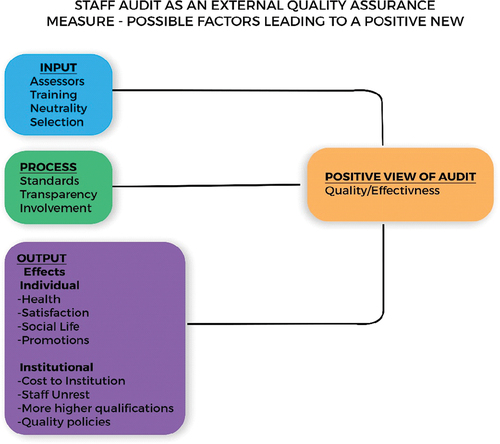

The study is based on an adaptation of the input-process-output-context framework by Creemers and Scheerens (Citation1992). The validity of the framework is evidenced by its used by several researchers’ examining quality issues in education (e.g., The Education for All (EFA) Global Monitoring Report, (Citation2002) (2002); Fuller and Clarke (Citation1994); Heneveld and Craig (Citation1996); Lockheed and Verspoor (Citation1991)). Inputs, according to Creemers and Scheerens (Citation1992) consist of all kinds of variables connected with the characteristics of the assessors. Context describes guidelines and regulations for the exercise (not examined in this case). Process denotes factors within the control of the external assessors that make a difference between whether the exercise will be perceived as positive or negative. Output includes the effect of the exercise on the institutions and individual staff within them. Overall, the framework aided the selection of variables for the study (see Figure ). Worth noting also, is the fact that the conceptual framework adapted for this study is only meant to guide the study and not to make causal or substantive claims. This is because this investigation basically seeks to lay the grounds for future research that may have stronger basis for making substantive claims.

3. Methods and materials

3.1. Research design

The design of the study was most appropriately exploratory given that this is the first time ever that a staff audit has been carried out in the TUs. This study therefore sought to document the perceptions of lecturers on an external staff audit conducted by the national regulator of tertiary education in Ghana and its effect on the concerned institutions and the teaching staff within them. The approach taken is the gradualist approach. The gradualist approach taken is meant to provide an initial record and understanding of the issues examined in this study thereby laying the groundwork for future research into emerging issues. This limitation is duly acknowledged as making substantive claims such as causal effects were not the focus of this study. Concurrent mixed method approach which facilitated the examination of the issues from different perspectives was used to collect both quantitative and qualitative data. This was based on the pragmatism philosophy which advocates for methods that better fit the circumstances of a study. This approach improved the quality of the collected data by enriching it with different perspectives. The inquest was principally guided by the following research questions:

How was the staff audit conducted by the NCTE viewed by the TUs and their teaching staff, and what factors possibly, informed their views?

What were the associated individual and institutional effects and challenges?

3.2. Population and sampling

The population for the study was all teaching staff within the eight TUs in Ghana. However, only seven of them actually took part in the study (there was no response from one TU). The teaching staff (at least, those with a master’s degree and above) were the focus of the study. The reason was that, they are important input for teaching and learning in higher education. The respondents from each TU were selected using stratified random sampling techniques. The staff in each TU was thus, grouped into males and females using the staff list collected from the Human Research Directorates (HRD) of the universities. The staff were randomly selected from the staff list. After an initial random selection of the first staff (male and female), every other second person was selected and contacted electronically (institutional email, what sup). Those who first responded, facilitated the contact of their colleagues for the study. The details of the population of each university by gender, the sample size selected by gender is presented on Table . The total population of staff in the selected universities was 2108; made of 1627 (77.2%) males and 481 (22.8%) females.

Table 1. The population and sample size for the study by gender

Table shows that TU1 had the highest number of respondents (24%). The least response of 9% was obtained from TU7.

3.3. Procedure and data collection

The study employed a semi-structured questionnaire (an electronic instrument because of how wide the TUs were spread across the country and the limited resources available for the study). The instrument was developed from literature, peer reviewed by two senior colleagues and piloted using the two-teaching staff from two of the TUs. This instrument was used to collect the data only after the suggested corrections were made (e.g., confusing or ambiguous questions, question repeated in different forms). The piloting of course, enhanced the reliability and validity of the instrument. The final instrument used for the data collection had the following four sections: Background information, the nature of the audit, the effects (at the individual and institutional levels) and the associated challenges. The first three aspects were quantitative/coded while the last part was qualitative. In all, there were 44 items on the instrument. The scale used for the quantitative aspect were: Definitely (= 1), possibly (= 2) and definitely not (= 3).

Collecting data for the study started a year after the completion of the staff audit (November, 2019). This was necessary to ensure that all issues related to the staff audit (input and processes), implications for both institutions and individuals within them (subsequent effects) were clear (not speculative) at the time of the data gathering. To formally start the data collection, the institutions were first written to, through the Human Resource Directorate of each university for onward submission to the appropriate ethical clearance committee or body in the University. The permission letter clarified the purpose of the study and the use of any data collected. Specific ethical issues stressed in the letter were informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality and voluntary participation. This was followed by a verbal discussion (on phone) with the heads of the HRD to find out the state of the application and to answer questions raised until the final approvals were received. The period for the data gathering was six months. However, only a few responded to the initial call for participation in the study. The few who responded however were asked to recommend others who were willing to participate in the study (e.g., provided colleagues working emails/telephone numbers and/or spoke to them on our behalf to assist with the data collection). Of those recommended, 90% responded to the instrument. The completed instruments were returned though the same means of receipt (email or WhatsApp). In all, 212 (10.8%) staff from the TUs consisting of 118 (56.6%) males and 93 (43.4%) females responded to the instrument. According to Israel (Citation1992), for a precision of 5% for a population of 20,000, the sample size (n) should be 204. So, for the current study with a population of 2108, a sample size of 212 was considered appropriate.

3.4. Data analysis techniques

After the completed instruments were returned, the data (both quantitative and qualitative aspects) were cleaned. For instance, incomplete answered questionnaires were excluded and follow-ups were made on responses that were not clear. Afterwards, the quantitative data was coded and evaluated using descriptive (mainly means and frequencies) and factor analysis with the aid of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Software (SPSS). Factor analysis was chosen because it is an exploratory tool meant to guide researchers in making decisions about which factors are important to an issue under investigation (Field & Golubitsky, Citation2009). As earlier mentioned, this study is exploratory given that this is the first time a staff audit has been carried out in the TUs. Besides, the most practical use of factor analysis is typically when researchers are interested in factors that cannot be observed directly, such as achievement, intelligence, or beliefs; in this example, the teaching staff’s perceptions or feelings towards a staff audit carried out by an outside regulator. The overall purpose of the factor analysis therefore, was to measure the different aspects of what influenced the lecturer view (positive of otherwise) of the entire staff audit exercise. Although there are many applications for factor analysis (confirmatory and exploratory), the technique was employed in this analysis to examine the covariation among the observed variables and reduce the number of observable variables into a smaller number of latent variables. Strictness was obtained in describing the most frequent variation in a correlation matrix by employing a reduced number of explanatory contrasts by narrowing the dataset from an interrelated variable to a smaller collection of factors.

On the other side, theme analysis was used to analyse the qualitative component. The discussion segment then included a triangulation of the quantitative and qualitative findings. Thematic analysis, which falls under the category of qualitative descriptive design, is employed to examine textual data and elaborate on the theme. The key characteristics are the systematic processes of coding, the examination of meaning and the provision of descriptions (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2003; Vaismoradi et al., Citation2013). The theme as used in this article, describes an attribute, descriptor, element or a concept that implicitly organises a group of repeating ideas to help us answer the research questions of this study (Ayres et al., Citation2003). Within-case and across-case approaches to qualitative data analysis. Qualitative health research, 13(6), 871–883. Each team had a sub-theme. Both the theme and the sub-themes were coded. The codes were common points of reference which had high degree of generality (unified ideas regarding a subject). Simply put, they were elements of the subjective understandings of the participants’ underlying views (meanings) indirectly discovered at the interpretative level by the researchers. In order to see the data in its whole and identify trends in the participants’ responses, the sub-themes were used (Bradley et al., Citation2007; Ryan & Bernard, Citation2003). In all, the following two main themes emerged—the benefits of the audit and the associated challenges.

4. Results

The results of the study are presented in line with the research questions – (1) The perceptions of the selected TUs regarding the staff audit and the factors possibly, informing their perceptions and (2) the effects and challenges associated with the audit. The conceptual framework which shows how the assessment inputs, processes and effect (outcomes), associate with the lecturer’s views is used as the basis for the result presentation.

4.1 The teaching staff’s perception of the audit and possible factors informing it

4.1.1 The teaching staff’s perception of the audit

Table shows (1) the inputs into the assessment in terms of the assessors’ characteristics (selection, training and neutrality) and (2) the processes of the assessment (the standards used, the extent of institutional involvement and transparency) as depicted on the conceptual framework. Regarding the assessors as inputs, the general view was that the assessors were definitely (2.58) not selected from the technical universities. In fact, to some respondents, the assessors were possibly (1.87), only given rating sheets and other practical information to work. They also, lacked adequate training (1.97). Nevertheless, they were considered possibly (2.16) neutral in the assessment. With respect to the audit processes, it was mentioned that possibly (2.43), it started with extensive consultations with stakeholders. The exercise was considered to have possibly (1.73) over relied on externally imposed regulations and international standards. This might have possibly (1.86), been due to the absence of clearly defined guidelines on how the assessment should be done. The perception that the panel possibly, (1.97) had difficulty agreeing on the appropriate levels of compliance was therefore not surprising. The definition and interpretation of the standards used were however, considered possibly (2.34), flexible. The audit processes were also possibly considered transparent (2.17), open and free of non-academic influences. The Standard Deviations (SD) were between .45 and .75 indicating that the views of the lecturers, were quite wide.

Table 2. How the audit was perceived by the teaching staff of the TUs

4.1.2 Possible factors contributing to the lecturer’s perception of the audit

This issue was addressed using factor analysis. To run the factor analysis, first there was data screening and assumptions testing using the correlation matrix, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s measures. In the correlation matrix, none of the variables had the majority of the significance greater than .05. Also, a correlation coefficient of .90 was recorded which implies that there was no problem with singularity in the data. The determinant of the correlation matrix was .06 - a value greater than the necessary value .00001. As a result, the data did not have a problem with multicollinearity. Simply expressed, there was no need to delete any question because all the questions connected very well. The range of 0 to 1 is anticipated for the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy statistic. Indicating diffusion in the pattern of correlations or that the variables were completely independent of one another (in which case factor analysis would probably not be suitable), a value of 0 shows that the sum of partial correlations is large relative to the sum of correlations. When the correlation patterns are somewhat compact and the value is near to 1, factor analysis will produce distinct and trustworthy factors. This statistic’s value for the data was.80, demonstrating the suitability of factor analysis. The original correlation matrix’s identity matrix is the null hypothesis that is being tested by Bartlett’s measure. The R-matrix is not an identity matrix, which means that there are some links between the variables we wished to include in the study, according to a significant test. Factor analysis was appropriate because Bartlett’s test was extremely significant for these data (p .001).

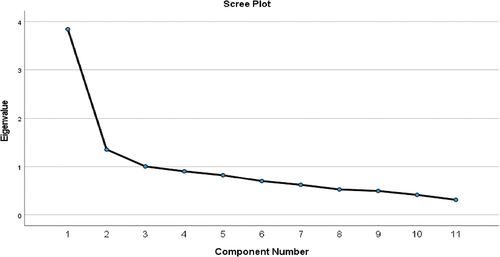

The eigenvalues associated with each linear component (factor) before extraction, after extraction, and after rotation are listed in the SPSS output of the total variances explained. Each factor’s eigenvalues correspond to the variance that is explained by that specific linear component; this is also expressed as a percentage of variance explained. Three factors were extracted by the analysis as indicated on Table . Factor 1 explained 34.60%, factor 2 explained 12.29%, and factor 3 explains 9.12% of the total variance. Overall, the model explained 56.37% of the total variance. Although the model explained more than half of the total variance, the suggestion is that other factors (about 44%) apart from those examined by the study might account for the perception of the lecturers. See Table .

Table 3. Total variance explained

After the extraction, the communalities show how much of each variable’s variance can be explained by the kept factors. Both the communalities prior to and following the extraction are displayed in the communalities output. All deviations were first thought to be common (1). However, the extraction column demonstrates the extent to which the extracted factors explain for the variance in the variables. For example, we can say that 32.10% of the variance associated with item 1 (i.e., the standard used was based on international bench-marks) was common or shared. See Table .

Table 4. Communalities

The screen plot, which plots the eigenvalues against each of the factors, is depicted in Figure . Due to the curve’s tendency to tail off after two components and drop again after a fourth, it is frequently challenging to interpret. However, depending on where the graph begins to flatten, it is helpful in deciding how many elements to keep. Kaiser’s criterion dictates that all factors with Eigen values above 1 should be kept if there are less than 30 variables and the extracted communalities are greater than.70; or if the sample size is greater than 250 and the average communality is greater than.60. When the sample size is big (about 300 cases or more), a Scree Plot can be utilised if none of the aforementioned scenarios apply. According to the general rule, the scree plot is useless in this situation.

The loadings of the variables on the factors extracted are displayed in the component matrix below. The factor contributes to the variable more when the absolute value of the loading is bigger. Every loading below 0.1 is considered suppressed. The following factors nonetheless, loaded on component 1: (1) Extensive consultations with stakeholders were made before the exercise; (2) The processes were transparent, open and free of non-academic influences; (3) Some of the auditors were from the technical universities; The auditors were neutral parties in the process; (4) There was flexibility in defining and interpreting the standards; (5) It appeared the auditors lacked adequate training; (6) The standard used was based on international benchmarks; (7) The assessors were merely provided with rating sheets and other practical information; (8) The exercise overly relied on externally imposed regulations; (9) The panel had difficulty agreeing on appropriate level of compliance; and (10) There was lack of clear guidelines on how the assessment should be done. Component 2 loaded the following factors: (1) The auditors were neutral parties in the process; (2) The standard used was based on international bench-marks; (3) Some of the auditors were from the technical universities; (4) Extensive consultations with stakeholders were made before the exercise; (5) The exercise overly relied on externally imposed regulations and (6) The assessors were merely provided with rating sheets and other practical information. Component 3 loaded the factors: (1) The process was transparent, open and free of non-academic influences; (2) The standard used was based on international benchmark; (3) There was lack of clear guidelines on how the assessment should be done; (4) Extensive consultations with stakeholders were made before the exercise; (5) It appeared the auditors lacked adequate training; (6) The exercise overly relied on externally imposed regulations; and (7) The assessors were merely provided with rating sheets and other practical information. Common factors loaded by all the three components were as follows: (i) The process was transparent, open and free of non-academic influences; (ii) Some of the auditors were from the technical universities; (iii) There was flexibility in defining and interpreting the standards; (iv) It appeared the auditors lacked adequate training the panel had difficulty agreeing on appropriate level of compliance; and (v) there was lack of clear guidelines on how the assessment should be done.

The rotated component matrix (reduced the number factors to only those with high loadings to make the interpretation easier) had the following as common to all the three components: The standard used was based on international benchmarks; extensive consultations with stakeholders were made before the exercise; and the assessors were merely provided with rating sheets and other practical data (Table ).

Table 5. The effects of the staff audit

4.2 The effect and the associated challenges

4.2.1 The effect of the audit on the TUs and the individual teaching staff

Generally, the effect of the staff audit was considered possibly, positive. However, for individual lecturers, the following three areas were examined: health, job satisfaction and the social life. In terms of their health, the average view was that the exercise has certainly (1.44) resulted in personal and family stress with possible (1.69) worsened health conditions such as high blood pressure. The SD was between .55 and .62 indicating little differences in the opinions of the lecturers. With respect to job satisfaction the following four perspectives were definitely affected: Job insecurity, employee commitment, change in intentions and plans, and position. Specifically, the audit definitely resulted in job insecurity, low employee commitment, change in plans and intentions and official positions (1.49–1.88, SD = .55–.73). Obviously, there were some differences in the lecturers’ opinions as indicated by the SD. Regarding the social life of the staff, it perceived that the exercise possibly, strained relationship with colleagues and superiors (1.73 and 1.94; SD = .58 and .63 respectively).

4.2.2 The challenges associated with the audit

The qualitative analysis produced two main themes—the benefits of the audit and its associated challenges. Regarding the benefits of the staff audit, it was acknowledged that it helped foster a new sense of concern about enhancing the quality of teaching, learning, research, and general public services in the TUs. The audit had also, encouraged quality improvement meant to move the TUs in the direction of world-class institutions. The potential of lowering standards was further believed to have been reduced leading to the propensity of making graduates from the TUs more competitive, effective and able in contemporary times. The use of peer reviewers in particular, had many unintended benefits. The following were some of their comments:

Int1: “They have helped foster a new sense of concern about improving teaching, learning, research, and public service in many TUs.”

Int2: “Have had a significant impact on the institutions by encouraging quality improvement and moving the institutions in the direction of world-class standards.”

Int3: “The procedures have helped to reduce the potential of lowering standards.”

‘It has made the institutions and their graduates more competitive and able to operate

effectively in the knowledge environment of the contemporary era.’

It appeared that intrinsically, the TUs were more accustomed to their autonomy and the tradition of peer evaluation. Others believed the assessors had no training at all or that they were only given rating sheets and other useful details about the activity. Some believed that selecting assessors from various academic fields and institutions was the best course of action. Even said, discussions with the institutions to provide them the chance to offer feedback on the parameters created by the panel should have taken place before the exercise. Others questioned if the activity was worthwhile and whether it would result in improvement. Some even questioned the legitimacy of the whole exercise and its possible consequence in areas such as funding, the continuous functioning of the university and the broadcast of the staff audit outcome. Some of their comments were:

Int4 ‘Intrinsically, the TUs are accustomed to autonomy and are more oriented towards the tradition of collegial peer evaluation’

Int4 ‘The questions are: Whether or not the exercise resulted in quality improvement; Do the external agencies have the power to close down institutions as a result of the exercise;Will the outcome of the exercise be publicized; Will the exercise affect funding?’

Int5 “I felt there was lack of preparation on their part”.

‘There was no training at all—were merely providing rating sheets and other practical information about the visit.

‘It should have been preceded by meetings with the institutions and opportunities for them to provide feedback on the guidelines prepared by the panel should have been given’.

`Int6 ‘One approach is to pick representative samples from different academic areas (sciences,

humanities, social sciences, professions) for review at each institution.’

5. Discussion

This study has provided evidences in support of the view that external quality mechanisms such as a staff audit can be a two-edged sword given that it can have both positive and negative effects. Further highlighted, by this study are some concerns about the assessors used for the external audit and the audit process itself. This study has also interestingly brought to the fore some crucial factors informing how an external audit could be perceived by academics as well as the effects of a staff audit on both institutions and the individual staff within them. Based on these highlights, the following three key issues are discussed: (1) How external staff audit is generally perceived by academic staff; (2) The probable effects of staff audit on staff and institutions; and (3) Possible factors influencing the view of lecturers.

Regarding how an external staff audit is seen by the teaching staff of the TUs, the general view from both the quantitative and qualitative results was that perhaps, the staff were intrinsically accustomed to internal, rather than external evaluations or had issues with external assessments. For instance, the quantitative results indicated the following concerns about the assessors: The assessors were not from the (sister) TUs and their neutrality, training and having the necessary practical information to carry out their work effectively could not be guaranteed were raised. The same was true of the audit processes, which they only probably, considered transparent, open and free of non-academic influence. The exercise further described as lacking flexibility, extensive consultations, clear guidelines on how the assessment should be done, and over relying on externally imposed regulations/international standards. The qualitative results additionally, indicated that the assessors were viewed as not having been trained at all or that they were only given rating sheets and other useful details to conduct the exercise. Some even questioned the legitimacy of the whole exercise.

These feelings might imply a lack of confidence in how the entire procedure was conducted. However, given the claim made by Harvey and Williams (Citation2010) that academics view external quality systems as burdensome and not a part of their daily work, these attitudes are not at all surprising. For instance, in the UK, the Quality Assurance Agency’s (QAA) external reviews are frequently viewed with suspicion (Cheng, Citation2009). One example is Cheng’s (Citation2011) research. Cheng came to the identical conclusion that the internal audit mechanism established within the university performed more successfully and was perceived as more legitimately than the external one utilising interview data from 64 academics and document analysis in the UK. The causes of this could be numerous; however, past research has suggested that academic staff continue to oppose quality processes because they: (a) do not passively accept change or the specifics of quality assurance requirements (policies or systems), (b) perceive external evaluations as incompatible with the sense of autonomy associated with professionalism, a special type of occupational control that permits professionals to only promote and facilitate occupational changes without interference, and (c) see external evaluations as a reduced form of occupational control.

With respect to the probable effects of the audit, evidence from both the quantitative and qualitative analyses showed that external quality mechanism such as staff audit can lead to both improvements and drawbacks. The audit at the institutional level was thought to have contributed to the development of a new sense of care for enhancing teaching, learning, research, and general public services in the TUs, notwithstanding some discrepancies in the lecturers’ viewpoints. Other beneficial outcomes included promoting quality improvement and guiding TUs towards becoming world-class institutions; minimizing the possibility of lowering standards and increasing the likelihood of making graduates more capable and competitive globally. These findings go to buttress the earlier arguments of Al-Maskari (Citation2014) that external quality mechanisms can stimulate change and improve teaching and learning in academic institutions. Carr et al. (Citation2005) further explain that the implementation of increased policies emanating from external quality measures can result in more transparency in university processes and lead to staff promotion, scholarship, development and orientation as they regularly refer to these documents in their day-to-day work (Ryan, Citation2015). These notwithstanding, the audit exercise was perceived as a contributing to the increases in staff attrition, unrest, unionism and the financial burdens on the TUs. Such financial burdens possibly included expenditure on staff development to get the necessary qualification(s) and training and living cost of the assessment team during the exercise (The Technical universities staff Audit Report, Citation2018).

At the individual level, a more negative effect on health, job satisfaction and social life was observed. For instance, the audit possibly brought about personal and family stress, high blood pressure (health wise), job insecurity, low employee commitment, change in plans and intentions and official positions and strained relationship with colleagues and superiors (socially). These finding were as expected. For example, even before the start of the exercise, the Ghanaian Graphic Online of NaN Invalid Date , reported that the planned exercise had created fear and anxiety in some of the TUs since there were fears that some staff did not have the requisite qualifications to be at post. Besides, the exercise become a major topic for discussion (NCTE begins nationwide audit of staff of Technical Universities—Graphic Online). Naturally, these emotions typically work against an employee’s job satisfaction, which is a good perception of their professional life based on anticipation, experience, and options (Hülsheger et al., Citation2013). It’s interesting to note that motivation and performance rise when job satisfaction is high. However, without job satisfaction, an employee’s commitment to their work and to the organization’s goals declines (Panaccio et al., Citation2014; Richardson, Citation2014; Ridzuan, Citation2014).

With respect to the factors that informed the perception of the lecturers regarding the audit, the rotated component matrix put the spotlight on the following three factors: The standard used was based on international benchmarks; extensive consultations with stakeholders before the exercise; and the assessors were merely provided with rating sheets and other practical data. These finding confirm the earlier augments of Hayward (Citation2008) that the legitimacy of quality audit processes depends on: The severity of externally imposed regulation or condition, the extent of stakeholder involvement especially, in contentious issues and the extent to which compliance work against quality development in the university. Other studies have underscored the need to pick representatives from different academic areas and institutions as assessors and precede the exercise with meetings that give institutions the opportunity to provide feedback on guidelines prepared. The importance of the quality, dedication and integrity of the people who serve as the assessors have also been emphasised (Akalu, Citation2014; Shah, Citation2012).

6. Implications for policy and practice

Regulatory bodies may seek and appreciate the balance between desirable levels of autonomy for academics and accountability at the same time.

Regulatory bodies could have extensive consultations and consensus with stakeholders regarding how an external quality measurement as a staff audit should be done. This would evidently make stakeholders see the exercise as transparent, open and free of non-academic influences.

Regulatory bodies may provide clear guidelines on how external staff audit should be done, the standards to be used and consequences thereafter before the start of the exercise to instill trust in stakeholders.

The assessors used for external staff audits may be carefully selected, well trained by the regulatory bodies and provided with relevant information necessary for the smooth facilitation of the assessment and its processes.

Technical university managers could establish and sustain an effective internal quality measure that promotes shared perspectives, values, procedures, practices and approaches that promote quality internally.

The universities could pillow the personal pains and challenges of staff who suffered as a result of the audit by providing emotional and social support as well as scholarships for higher degrees.

Future research may look at the extent of improvement in quality of staff within the TUs from the time of the audit to date.

7. Conclusions

This study set out to examine the following three key issues: lecturers’ perception of a recent staff audit conducted by the NCE on behalf of the Ghanaian government, the factors that contributed to how the audit was perceived and the effect of the audit on the universities and the individual teaching staff within them. Of course, the findings of this study have stressed the importance of stakeholder consultations and having a shared view about how an external audit should be conducted in terms of the assessors selected, the assessment processes and the subsequent effects. Granting that academics generally resist external assessment as professionals; the value of an external staff audit that is transparent, free of non-academic influences, flexible, shared and balanced can be priceless especially in gaining the trust of academics and in leading to the desired quality improvement. This study has looked at the issue of external staff audit from only the perspective of teaching staff. Future research could investigate the same issue from the perspective of non-teaching staff and the national quality assurance regulatory bodies.

8. Limitations and suggestions for further studies

In Ghana public university are made up of traditional and technical universities. Unfortunately, this study focused on only the technical universities (seven out of the eight TUs in Ghana) although the same exercise was later conducted in the traditional universities too. This limitation is duly acknowledged as limiting the findings of this study to only the participating TUs. To improve the generalizability of the study findings in the future, the inclusion of the traditional universities is recommended for future research.

AUTHORS BIO REVISED.docx

Download MS Word (12.9 KB)Title Page with Author Details NEW.docx

Download MS Word (13.3 KB)Acknowledgments

Authors will like to acknowledge the support of Mr. Ronald Osei Mensah, Social Development Section, Takoradi Technical University for his constant support through submission and formatting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2286667

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maame Afua Nkrumah

Maame Afua Nkrumah researches mainly in Educational Quality Assurance and Institutional Effectiveness. She is an Associate Professor at the Social Development Section of the Centre for Languages and Liberal Studies of the Takoradi Technical University (TTU). She has over thirty-two publications to her credit. Currently, she teaches Precision Quality, Social Psychology and Research Methods at TTU and has over 15 years’ teaching experience.

Esther Gyamfi

Esther Gyamfi is a Senior Assistant Registrar at the International Programmes and External Linkages Office of the Takoradi Technical University. She has four articles to her credit and is currently pursuing a PhD programme in Human Resource Management at the Durban University of Technology, South Africa.

Pearl Aba Eshun

Pearl Aba Eshun is a Senior Technician at the International Programmes and External Linkages Office at Takoradi Technical University. She holds a Bachelor of Technology in Hospitality Management and is currently pursuing MPhil in Hospitality and Tourism at Durban University of Technology.

References

- Abukari, A., & Corner, T. (2010). Delivering higher education to meet local needs in a developing context: The quality dilemmas? Quality Assurance in Education, 18(3), 191–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684881011058641

- Afeti, G., Afun, J., Aflakpui, G., Combey, A. K. S. C. R. J., Nkwantabisa, M. D. D., Duwiejua, M. … Ankomah-Asare, E. T. (2014). Report of the technical committee on conversion of the polytechnics in Ghana to technical universities. Ministry of Education:

- Aithal, P. S. (2015). Internal quality assurance cell and its contribution to quality improvement in higher education institutions: A case of SIMS. GE-International Journal of Management Research, 3, 70–83.

- Akalu, G. A. (2014). Higher Education in Ethiopia: Expansion, quality assurance and institutional autonomy. Higher Education Quarterly, 68(4), 394–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12036

- Al-Maskari, A. (2014). Does external quality audit make a difference? Case study of an academic institution. ASCI Journal of Management, 43(2), 29–39.

- Alves, M. G., & Tomlinson, M. (2021). The changing value of higher education in England and Portugal: Massification, marketization and public good. European Educational Research Journal, 20(2), 176–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904120967574

- Ansah, S. K., & Ernest, K. (2013). Technical and vocational education and training in Ghana: A tool for skill acquisition and industrial development. Journal of Education & Practice, 4(16), 172–180.

- Ayres, L., Kavanaugh, K., & Knafl, K. A. (2003). Within-case and across-case approaches to qualitative data analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 13(6), 871–883. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303013006008

- Billing, D. (2004). International comparisons and trends in external quality assurance of higher education: Commonality or diversity? Higher Education, 47(1), 113–137. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HIGH.0000009804.31230.5e

- Bradley, E. H., Curry, L. A., & Devers, K. J. (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42(4), 1758–1772. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x

- Carr, S., Hamilton, E., & Meade, P. (2005). Is it possible? Investigating the influence of external quality audit on university performance [1]. Quality in Higher Education, 11(3), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320500329665

- Cheng, M. (2009). Changing academics: Quality audit and its perceived impact. VDM Verlag.

- Cheng, M. (2010). Audit cultures and quality assurance mechanisms in England: A study of their perceived impact on the work of academics. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(3), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562511003740817

- Cheng, M. (2011). The perceived impact of quality audit on the work of academics. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(2), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.509764

- Cooper, S., & Poletti, A. (2011). The New ERA of journal ranking: The consequences of Australia’s fraught encounter with ‘quality’. The Australian Universities’ Review, 53(1), 57–65.

- Creemers, B. P., & Scheerens, J. (1992). Developments in the educational effectiveness research programme. International Journal of Educational Research, 21(2), 125–140.

- EFA Global Monitoring Report. (2002). Is the world on track? (UNESCO www.unesco.org/education/efa/monitoring/monitoring_2002.shtml

- Effah, P., & Mensa-Bonsu, J. A. N. (2001). Governance of tertiary education institutions in Ghana. National Council for Tertiary Education.

- Field, M. & Golubitsky, M. (2009). Symmetry in chaos: A search for pattern in mathematics, art, and nature. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

- Fisher, W. W., Kelley, M. E. & Lomas, J. E. (2003). Visual aids and structured criteria for improving visual inspection and interpretation of single-case designs. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis, 36(3), 387–406.

- Foster, P. (1965). The vocational school fallacy in development planning. Education and Economic Development, 32(1), 142–166.

- Fourie, M., & Alt, H. (2000). Challenges to sustaining and enhancing quality of teaching and learning in South African universities. Quality in Higher Education, 6(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/713692737

- Frazer, M. (1992). A New approach to quality assurance for higher education. Quality Assurance in Higher Education, 9(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.1992.tb01587.x

- Fuller, M., & Clarke, P. (1994). Raising school effects while ignoring culture? Local conditions and the influence of classroom tools, rules, and pedagogy. Review of Educational Research, 64(1), 119–157. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543064001119

- Harvey, L., & Williams, J. (2010). Fifteen years of quality in higher education. Quality in Higher Education, 16(1), 3–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538321003679457

- Hayward, F. M. (2008). Strategic planning for higher education in developing countries. Society for College and University Planning.

- Heneveld, W., & Craig, H. (1996). Schools count: World Bank project designs and the quality of primary education in sub-Saharan Africa (Vol. 303). World Bank.

- Hou, A. Y. C., Hill, C., Justiniano, D., Lin, A. F. Y., & Tasi, S. (2022). Is employer engagement effective in external quality assurance of higher education? A paradigm shift or QA disruption from quality assurance perspectives in Asia. Higher Education, 1(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00986-7

- Hou, A. Y. C., Hill, C., Justiniano, D., Yang, C., & Gong, Q. (2021). Relationship between ‘employability’ and ‘higher education’ from global ranker and accreditor’s perspectives—does a gap exist between institutional policy making and implementation in Taiwan higher education? Journal of Education & Work, 34(3), 292–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2021.1922619

- Hou, A. Y. C., Kuo, C. Y., Chen, K. H. J., Hill, C., Lin, S. R., Chih, J. C. C., & Chou, H. C. (2018). The implementation of self-accreditation policy in Taiwan higher education and its challenges to university internal quality assurance capacity building. Quality in Higher Education, 24(3), 238–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2018.1553496

- Houston, D., & Paewai, S. (2013). Knowledge, power and meanings shaping quality assurance in higher education: A systemic critique. Quality in Higher Education, 19(3), 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2013.849786

- Huisman, J. (2007). The anatomy of autonomy. Higher Education Policy, 20(3), 219–221. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300162

- Hülsheger, U. R., Alberts, H. J., Feinholdt, A., & Lang, J. W. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: The role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 310. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031313

- Israel, G. D. (1992). Determining sample size (fact sheet PEOD-6). University of Florida.

- Jeliazkova, M., & Westerheijden, D. F. (2002). Systemic adaptation to a changing environment: Towards a next generation of quality assurance models. Higher Education, 44(3/4), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019834105675

- Jingura, R. M., & Kamusoko, R. (2019). A competency framework for internal quality assurance in higher education. International Journal of Management in Education, 13(2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMIE.2019.098186

- Lisinski, M., & Szarucki, M. (2011). Internal audit in improving the organization. PWE. ISBN 978-83-208-1914-4.

- Lockheed, M. E., & Verspoor, A. M. (1991). Improving primary education in developing countries. Oxford University Press for World Bank.

- Martin, M., & Stella, A. (2007). External quality assurance in higher education: Making choices. Fundamentals of Educational planning 85. International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP) UNESCO. 7-9 rue Eugene-Delacroix, 75116.

- Materu, P. N. (2007). Higher education quality assurance in sub-Saharan Africa: Status, challenges, opportunities and promising practices.

- Paintsil, R. (2016). ‘Balancing internal and external quality assurance dynamics in higher education institutions: a case study of University of Ghana’, Doctoral ThesisUniversitetet Oslo.

- Panaccio, A., Vandenberghe, C., & Ben-Ayed, A. K. (2014). The role of negative affectivity in the relationships between pay satisfaction, affective and continuance commitment and voluntary turnover: A moderated mediation model. Human Relations, 67(5), 821–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713516377

- Pauli, U. & Pocztowski, A. (2019). Talent management in SMEs: An exploratory study of polish companies. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 7(4).

- Richardson, F. W. (2014). Enhancing strategies to improve workplace performance ( Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3669117).

- Ridzuan, Z. (2014). Relationship between job satisfaction elements and organizational commitment among employees of development finance institution in Malaysia Master’s Thesis, University Utara Malaysia, 20144. Retrieved from https://etd.uum.edu.my/4164/1/s811774.pdf

- Ryan, T. (2015). Quality assurance in higher education: A review of literature. Higher Learning Research Communications, 5(4), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.v5i4.257

- Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2003). Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 905–923. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303253488

- Schindler, L., Puls-Elvidge, S., Welzant, H., & Crawford, L. (2015). Definitions of quality in higher education: A synthesis of the literature. Higher Learning Research Communications, 5(3), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.v5i3.244

- Shah, M. (2012). Ten Years of external quality audit in Australia: Evaluating its effectiveness and success. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(6), 761–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.572154

- Taiwo, E. A. (2011). Regulatory bodies, academic freedom and institutional autonomy in Africa: Issues and challenges–the Nigerian example. Journal of Higher Education in Africa/Revue de l’enseignement supérieur en Afrique, 9(1–2), 63–89. https://doi.org/10.57054/jhea.v9i1-2.1574

- Tam, M. (2000). Constructivism, instructional design and technology: Implications for transforming distance learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 3(2), 50–60.

- Tam, M. (2010). Quality assurance policies in higher education in Hong Kong. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 21(2), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080990210208

- The Technical universities staff Audit Report. (2018). Available Final report_web version_Universities 2018 audits.pdf (nsw.gov.au)

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

- Van Vught, F. A., & Westerheijden, D. F. (1994). Towards a general model of quality assessment in higher education. Higher Education, 28(3), 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01383722

- Vroeijenstijn, T. (2004). International Network for quality assurance Agencies in higher education: Principles of good practice for an EQA agency. Quality in Higher Education, 10(1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/1353832242000195851

- Vroeijenstijn, T. (2008). Internal and external quality assurance: Why are they two sides of the same coin? Available at http://www.eahep.org/web/images/Bangkok/28_panel_ton.pdf.

- Woodhouse, D. (2003). Quality improvement through quality audit. Quality in Higher Education, 9(2), 133–139.