Abstract

The phenomenon of dual identity in border societies has become an increasingly critical issue in a global society that is becoming more cosmopolitan, and borders are becoming less relevant. This article investigates this issue through the lens of a case study of dual-identity citizens in Indonesia’s Sebatik Islands, an island off the eastern coast of Borneo that is part of both Indonesia and Malaysia. The study employs qualitative methods and collected data through observation, interviews, and focus group discussions. The data was analyzed by an interpretive approach. The study’s findings suggest that Sebatik citizens have a strong sense of dual identity, with their nationality and ethnicity deeply intertwined. They frequently seek privileges based on their citizenship status, such as access to basic necessities and employment opportunities driven by the communities’ socioeconomic demands. This study fills an empirical gap in border communities’ quandary in reconciling their dual identities and gaining access to resources and opportunities in an increasingly borderless world.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The possession of dual citizenship confers a multitude of benefits, however it also presents certain obstacles that necessitate thoughtful examination and strategic management. This study examines the two identities of the Sebatik Islands residents, who live in Indonesia-Malaysia border regions. The study suggests that individuals belonging to the Sebatik border regions engage in the construction of a distinct social identity as a means to obscure their civic identity. The border society engage in self-categorization, enabling them to effectively navigate their social identities as border inhabitants and concurrently maintain dual identities. The interrelation among these identities has the potential to influence an individual’s views, behaviours, and social interactions, particularly in relation to meeting their socioeconomic needs. Finally, the phenomenon of individuals residing in border regions engage in a rational decision-making process. This behaviour is observed among certain residents of Sebatik who utilise their dual citizenship status, whether publicly or covertly.

1. Introduction

The state is an organization in a region with the highest legal power that its people acknowledge and obey. Citizens have obligations to the state and rights that must be granted and protected by the state in the relationship between citizens and the state. Citizens’ rights and obligations are inextricably linked to citizenship, which is an important identity for every citizen. Regarding citizenship, identity is a fundamental requirement for a person to be recognized as a member of the nation (Tilly, Citation1995; Yani & Hidayat, Citation2018).

However, as globalization continues to permeate societies worldwide, the concept of dual identity has become more prevalent in border areas. By definition, border areas are cultural crossroads where people may identify with more than one nationality or culture. Individuals and communities in these areas face unique social, cultural, and geopolitical challenges. Accordingly, understanding the complexities and nuances of dual identity in border areas is critical for policymakers, researchers, and practitioners to address these challenges effectively.

Dual identity, or belonging to two or more national or ethnic groups, is common in many border regions worldwide. Individuals living in these areas may have familial, linguistic, cultural, or economic ties to both sides of the border, causing them to see themselves as belonging to multiple communities. Individuals living in border areas may face opportunities and challenges as they navigate their dual identities and the social, cultural, and political implications of them. Furthermore, the geopolitical implications of dual identity in border areas should be considered. Dual identity can exacerbate interethnic tensions and conflicts while also raising issues of political sovereignty and territorial claims.

In addition, dual identity challenges traditional notions of national identity and borders, emphasizing the fluidity and complexities of identity in border regions. In border communities, where individuals may feel a sense of belonging to multiple groups but also face exclusion and discrimination from both sides, dual identity can be seen as a source of strength and conflict. Studying dual identity in border regions has significant implications for understanding these regions’ social, political, and economic dynamics, as well as for developing policies and practices that promote inclusive and equitable development.

Many cases of multiple citizenship in border areas have occurred in the current global situation (Bloemraad et al., Citation2008; Dewansyah, Citation2019, Kovács, Citation2006; Pudzianowska, Citation2017; Sejersen, Citation2018). Other examples are studies of citizens in border areas in post-communist Central and Eastern European societies (Howard, Citation2005; Iordachi, Citation2004), as well as studies of border areas communities in Mexico and the United States of America (Campbell, Citation2008; Ingber et al., Citation2022; Smith & Bakker, Citation2011). As with border communities in Indonesia, multiple community identities are located in border areas. For example, Sebatik Island is in Nunukan Regency, North Kalimantan Province. Sebatik Island is one of the small islands directly adjacent to Malaysia’s Tawau region, whose territory is divided between Malaysia and Indonesia (Sangkala et al., Citation2019; Sudiar, Citation2012; Veronika, Citation2016). The dual citizenship identities cases also occur in border communities who live in Kapuas Hulu Regency, West Kalimantan Province, and Nunukan Regency, North Kalimantan (Fitriani et al., Citation2016; Mali et al., Citation2021). Some citizens who live in these areas tend to have dual Indonesian and Malaysian citizenship.

However, based on Law Number 12 of 2016 concerning the Citizenship of the Republic of Indonesia, Indonesia adheres to the principle of ius sanguinis (law of the blood) in regulating the identity of its citizens (Kaelan & Zubaidi, Citation2007). This principle determines that a person’s citizenship identity is based on heredity rather than the country of birth. This concept determines one’s citizenship based on birth country, which is imposed only on children under the provisions of this Law. Despite this, Indonesian citizenship law recognizes multiple identities, with mixed-nationality children having a maximum age limit of 25 years. The Government of Indonesia does not recognize the existence of dual citizenship identities under this legal framework. When citizens are discovered to have dual citizenship, they must give up one of their citizenship. If they refuse to release one of their citizenship identities, the sanction obtained is the loss of Indonesian citizenship.

As a result, dual citizenship is a serious identity problem in Indonesian law. Identity in the context of citizenship is a component of translating the political psychology of community groups that are losing their identity. However, we need more studies to investigate why people in border areas are willing to choose to have two citizenships and how to obtain them. To fill this empirical research gap, this study will investigate the following research question: Why did the people of Sebatik Island have dual nationality? How does that identity endure? The following section elaborates on the literature review of dual citizenship, followed by sections on the research method and study results, and discussion.

2. Literature review

Dual citizenship is a legal concept that allows individuals to be recognized as citizens of two different countries at the same time. The concept of dual citizenship is increasingly important today, especially in border areas, where people may live and work in one country while maintaining close ties to another (Howard, Citation2005; Sejersen, Citation2018; Spiro, Citation2010). Previous studies examine the historical, legal, and social aspects of dual citizenship in border areas.

In the historical context, the concept of dual citizenship is not new. It can be traced back to ancient Rome, where citizenship was granted to those who were born in the city or who had been granted citizenship by the emperor (Ashirov, Citation2005; Namadula, Citation2020). During the Middle Ages, people who lived near borders were often able to move freely between countries without the need for a passport or visa, and it was not uncommon for people to have multiple identities (Kalvelagen, Citation2015). However, with the advent of the nation-state in the 19th century, citizenship became more closely tied to a person’s nationality. It was seen as a symbol of loyalty to the state. As a result, dual citizenship is often seen as a threat to national security (Macklin, Citation2007; Olena, Citation2017).

Due to historical concerns and perceptions of divided loyalties, dual citizenship is considered a threat to nationalism, and as such, some states have restricted or suppressed it (Blatter, Citation2011; Spiro, Citation2010). Due to the difficulties, it presented for productive bilateral relations between states, dual citizenship was frequently seen unfavorably. Competing claims over people with dual citizenship caused conflicts and disagreements between governments. Some countries hold nationalist arguments to ban dual citizenship to protect their interests and control their inhabitants clearly (Bauböck, Citation2011; Spiro, Citation2010). Dual nationals may have conflicted loyalty, making it difficult for individuals to prioritize one state’s interests ahead of another in certain circumstances, such as during conflicts or diplomatic conflicts, according to the dual citizenship threatens nationalism argument (Pogonyi, Citation2011).

The legal framework for dual citizenship in border areas has evolved over time. In many cases, dual citizenship is not recognized by law, and individuals are required to renounce their citizenship in one country to become citizens of another (Dewansyah, Citation2019; Kántor, Citation2005). However, in some cases, dual citizenship is allowed under certain circumstances. For example, in the European Union, citizens of member states are allowed to hold dual citizenship, and many countries have similar policies (Guild, Citation1996; Kovács, Citation2006; Pudzianowska, Citation2017; Sejersen, Citation2018). In some cases, dual citizenship is automatically granted to individuals who are born to parents of different nationalities, while in others, it is only available to those who can prove a significant connection to the other country (Guild, Citation1996; Kovács, Citation2006; Sejersen, Citation2018).

Lastly, the social implications of dual citizenship in border areas are complex and multifaceted. On the one hand, dual citizenship can be seen as a way to strengthen ties between neighboring countries and promote cross-border cooperation (Dewansyah, Citation2019; Kovács, Citation2006; Pudzianowska, Citation2017; Sejersen, Citation2018). It can also provide individuals with increased opportunities for travel, work, and education. However, on the other hand, dual citizenship can be a source of tension between countries, particularly if one country perceives it as a threat to its national security (Askola, Citation2022; Macklin, Citation2007; Olena, Citation2017). Additionally, some argue that dual citizenship can lead to a lack of loyalty and commitment to a single country and can create conflicts of interest for individuals who hold public offices or work in sensitive industries (Askola, Citation2022; Macklin, Citation2007; Olena, Citation2017; Pogonyi, Citation2011).

In addition, dual citizenship in border areas can raise various legal, political, and social issues. First, dual citizenship can be considered a risk to national security since it can lead to conflicts of interest for people who hold public office or operate in crucial fields (Macklin, Citation2007; Olena, Citation2017). For example, a person with dual citizenship in a border area could have divided loyalties if there is a conflict between the two countries. Individuals may therefore be reluctant to serve their country when they know they could be called upon to act against the interests of another country or people they regard as their “own.” National security issues in border areas are very sensitive and need support from citizens through awareness to help address this national threat, especially citizens who live in border areas (Askola, Citation2022).

Second, border control can be challenging in regions where people have dual citizenship, as they may be able to cross borders more easily and avoid immigration controls (Ramos et al., Citation2018; Torabian, Citation2019). Dual citizenship can create challenges for border control, particularly in regions where the border is porous or has a history of illegal immigration (Bhagwati, Citation2003). People with dual citizenship may have an easier time crossing borders than others, as they can use one passport to enter one country and the other passport to enter another country. These circumstances can create challenges for immigration officials to screen individuals at the border to ensure they meet the entry requirements (Bauböck, Citation2003; Torabian, Citation2019).

In some cases, people with dual citizenship may try to take advantage of their status to enter a country illegally or to engage in criminal activities. For example, in the US-Mexico border area, there have been cases of people with dual citizenship smuggling drugs or other contraband across the border (Campbell, Citation2008; Heyman, Citation2008; Ingber et al., Citation2022). This situation can create challenges for law enforcement officials responsible for preventing illegal activity and maintaining public safety.

However, it is important to note that not all people with dual citizenship pose a risk to border control or national security. Many people with dual citizenship are law-abiding citizens who have legitimate reasons for holding citizenship in two countries (Kochenov, Citation2019; Orgad, Citation2019). Some may have family members or business interests in both countries, while others may have been born in one country and raised in another. It is important to treat each case on its own merits and to ensure that policies and procedures are in place to properly screen and vet all individuals at the border, regardless of their citizenship status.

Third, dual citizenship can create challenges when it comes to voting rights (Spiro, Citation2019; Vink et al., Citation2019). For example, a person with dual citizenship in a border area may be able to vote in both countries, which can create challenges in determining eligibility, preventing fraud, and ensuring fair and democratic elections. This case is especially true in border areas, where people may have one citizenship but reside in a country with another. With so many people living in these areas, it can be difficult for the authorities to keep track of everyone’s status, which can mean that some residents end up excluded from voting. This issue can lead to inequality and unfairness between people living in the country legally and those not allowed to vote (Spiro, Citation2019).

Fourth, dual citizenship can create challenges when it comes to taxation. This is because most countries have their tax laws and regulations, and individuals with dual citizenship may be subject to taxation in both countries. As a result, they may be required to file tax returns and pay taxes in both countries, which can be complex and time-consuming.

The tax implications of dual citizenship can be particularly challenging in border areas, as individuals may have business interests, property, or investments in both countries (Christians, Citation2017; Harpaz, Citation2019; Mason, Citation2016; Spiro, Citation2019). For example, if a person with dual citizenship in a border area owns a business that operates in both countries, they may be subject to taxes in both countries on their business income. Similarly, if they own property in both countries, they may be subject to property taxes in both countries.

In recent years, the issue of dual citizenship in border areas has become increasingly contentious (Harpaz, Citation2019). The rise of nationalist and populist movements in many countries has led to a renewed focus on the importance of national identity and the need to protect national sovereignty. This has led some countries to adopt more restrictive policies on dual citizenship, while others have relaxed their policies to attract skilled workers and investors. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased travel restrictions and border crossings, making it more difficult for individuals to maintain ties to their home countries while living and working abroad.

3. Research method

This study employs qualitative methods to analyze the dual identities of Sebatik Island and describe how the community can survive with that identity. The study was located on Sebatik Island, Nunukan Regency, North Kalimantan, one of the outermost islands directly adjacent to Malaysia. An island with minimal facilities is described as a remote area left behind regarding its infrastructure.

This study applied the qualitative method with a case study approach. The case study method is a valuable research approach in sociology that enables researchers to thoroughly examine and comprehend particular social events, relationships, and systems (Creswell, Citation2014; Priya, Citation2021). It is intensive, detailed, and in-depth about an event or activity at the level of individuals, groups of people, and institutions. Obtaining knowledge and examining exceptional cases, particularly dual citizenship issues in border areas is helpful. Thus, the case study is limited to a certain period and in a narrow (micro) region because it examines the behavior patterns of individuals, groups, institutions, and organizations in a natural, holistic, and fundamental setting (Yin, Citation2014).

The method of key informant selection involved a purposive or deliberate consideration. Informants were selected based on three main categories: government actors, community leaders, and citizens with dual citizenship. The study employs a snowball method to ensure a comprehensive representation of citizen perspectives, whereby initial informants recommended and introduced subsequent informants with relevant experiences and knowledge. This approach allowed for diverse voices and experiences to be included in the study, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and dynamics surrounding dual citizenship in the border areas while avoiding the limitations of solely interviewing elite individuals.

An interpretative approach with a thematic analysis technique analyzed the data. The acquired data were subjected to a systematic pattern, theme, meaning identification, analysis, and interpretation. Familiarization was the first step in the process, during which researchers examined the material repeatedly and immersed themselves in it. Initial codes were then created by methodically labeling and classifying different data segments. The challenges of dual citizenship in border regions were then highlighted by grouping these codes into overarching themes and sub-themes, highlighting repeating trends and important discoveries.

The participant’s well-being and ethical considerations were given priority during the research ethics method used in this study. Participants gave their prior informed consent, assuring that they participated voluntarily and that their identities would be protected by anonymization. Researchers minimized potential injury or suffering, observed tight data security, and protected privacy and cultural standards. The protocol for the study got ethical approval, confirming that it complied with rules and added useful knowledge while preserving the rights and welfare of the participants.

4. Results and discussion

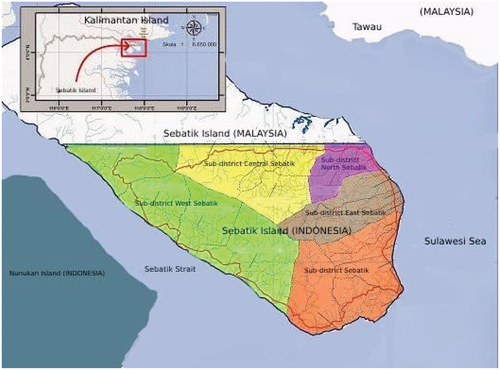

Sebatik Island is geographically located in the region far north of North Kalimantan Province. It lies directly adjacent to the State of East Malaysia (Sabah) on the northern part of Sebatik Island, as seen in Figure below. Its nearest neighbor to the west is the Nunukan Strait. The Makassar Strait and the Sulawesi Sea are adjacent to the east and south. Sebatik Island makes up about 24.6 thousand hectares, or 1.72%, of Nunukan Regency’s overall size. Central Bureau of Statistics (Citation2023) reports that 48,759 people live on Sebatik Island. Sebatik Island can only be accessed by sea and air transportation. The flight to Sebatik Island from Tarakan City, the capital of Nunukan Regency, takes about 30 minutes. Access by sea via the port in Tarakan City takes around 3 hours by speedboat.

Figure 1. Sebatik Island (www.bibit.indonesia.com, Citation2023).

Regarding administration, Nunukan Regency, North Kalimantan Province, once included all areas of Sebatik Island, was a subdistrict area. The island of Sebatik has been split into five sub-districts since 2011: Sebatik, West Sebatik, East Sebatik, North Sebatik District, and Central Sebatik. The two sub-districts of West Sebatik and East Sebatik contain most of the inhabitants on Sebatik Island. Residents of Sebatik Island typically rely on trading, fishing, and plantation sectors for their livelihood. People from various ethnic groups from Indonesian island areas, particularly from the islands of Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Java, live on Sebatik Island. The Tidung, Bugis, Flores, and Javanese groups have the biggest population. Sebatik Island has a population is virtually evenly dispersed across the entire island.

Since Sebatik Island is directly adjacent to the territory of neighboring Malaysia (Sabah), which has relatively higher economic levels, the border region of North Kalimantan has significant economic, geopolitical, defense, and security implications. This region’s natural resource potential is abundant, but it has not been utilized optimally until now (Sangkala et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, various pressing issues need to be addressed because of the large impacts and losses that can be caused.

The economic backwardness felt by North Kalimantan border communities, such as those on Sebatik Island, is also exacerbated by a lack of infrastructure and accessibility, such as road networks and land and river transportation links, which are still limited. In addition, infrastructure and communication facilities such as radio or television transmitters or transmissions and telephone facilities are in poor condition. Furthermore, basic social and economic facilities such as community health centers, schools, and markets are in short supply. Compared to the development conditions in neighboring Malaysia, border communities will increasingly feel the effects of these constraints.

Territorial borders close to Malaysia, even direct borders, could cause frequent problems involving the two countries. Isolation, underdevelopment, poverty, high prices of goods and services, limited infrastructure and public service facilities, low quality of human resources in general, uneven population distribution, and the build-up of Indonesia laborers due to their deportation from Malaysia are some of the problems faced by some people on Sebatik Island.

Citizenship issues are frequently raised. The unorganized process of moving in and out of the community at some points allowed border communities to pass through the two countries without encountering one of the root problems. The dilemma of residents’ citizenship is one that arises most frequently in the border villages located on Sebatik Island. This study identifies three critical reasons why Sebatik Island citizens have dual citizenship: meeting basic needs, having access to jobs, and poor population management. These three factors are thoroughly discussed in the following paragraphs.

4.1. Fulfilling basic needs

Community reliance on neighboring countries can reduce nationalism (Yani et al., Citation2019), but they are more concerned with economic needs than with their Indonesian citizenship. According to information obtained from several communities on Sebatik Island, particularly those near the border, they have a dual identity card. They want to improve relations with neighboring communities, which will provide numerous benefits. Meanwhile, access to communications and transportation into Indonesian territory remains limited, causing most of the population to band together and interact intensely with other residents in the Indonesian region. As a result, Sebatik needs to catch up in a variety of developments, both physical and non-physical.

The emergence of people who have dual nationality in Sebatik Island, also expressed by informant S.L., who works in the Regency Agency of the Population and Civil Registration,

Talking about dual citizenship in Nunukan Regency is very common in this area. The geographical location is very close to Malaysia or arguably the most angular districts because we are directly adjacent to Malaysia, not only bordering the ocean and even the mainland. So, the process of entry and exit of people between two countries can be spelled out very easily at several points. Residents who have two identities regularly administer their identities at the village office. At the end of 2016 yesterday, we served about five people from East Sebatik in the Civil Registration office. They are Indonesian citizens who also have Malaysian I.D.s. Actually, people who have two nationalities on Sebatik Island can say a lot, but to find out in a stable manner is quite difficult because the people certainly do not want to talk to the officers, but usually if there is something found like that, it is resolved by the informal way. Because it is normally way if we encounter any problems or reports at the immigration office or sub-district office.

According to the interview, most people who settled on the island of Sebatik have Indonesian and Malaysian citizenship. This situation shows that residents consider this common and normal even though it is legally contradictory. Officials also responded to this condition by not imposing the law because they thought that it had happened a long time ago and it would be troublesome for citizens to force them to choose one of the citizens.

Sebatik islanders are negative about their living circumstances within Indonesian territory. As a result, possessing a Malaysian identity increases their chances of finding employment without leaving their homes in Indonesia. The Indonesian administration has been working to enhance the situation at the border. President Jokowi and other ministry representatives visited Sebatik Island to observe the situation. Some locals, however, believe that progress has yet to be as expected. Considering dual citizenship, as citizens of Indonesia and Malaysia, for the people of Sebatik is a form of struggle to live comfortably, if dependent on the country so far, no real concern to people in border areas. As stated by informant SH, a resident of Sebatik Island,

Sebatik residents who have Malaysian identity cards have been going on for a long time because we are close to the Malaysia region. Thus, it will be easier for people to get treatment in the hospital if they are sick. If you want to seek treatment, we must go to Nunukan, which needs more time and cost. If it has a chronic disease, it will die in the street due to long journeys. So many people here, if they get sick, they prefer to cross over to Tawau [Malaysia territory] because it takes only fifteen minutes. Nevertheless, the problem later is that we need a family who can accompany us during treatment because people should have resident cards to get access to the service. So, to survive, the people here are more concerned about Malaysia than Indonesia.

Accordingly, people with dual nationality are very common on Sebatik Island. This situation is based on the hope that, in meeting the need for cross-border access, the community will rely on the Malaysian state for basic and economic needs. The Nunukan Regency Immigration Agency has collaborated with Malaysian officers on cross-country cards to get people in and out of the country, both from Indonesia and Malaysia. A cross-country card is issued by the immigration office to assist the public in passing and only applies for a few days. However, it is a widely misused policy used by the public, and even immigration officers frequently encounter people who are passing with dual nationality. This condition was described by informant MH, an officer of the Immigration Office at Nunukan Regency, as follows:

People who want to go to Malaysia or abroad should have a passport. But for the people in Nunukan Regency, especially those who border directly with Malaysia, such as Sebatik Island, we have cooperated with Malaysian immigration officials, namely the cross-country cards. But sometimes, some people abuse this policy; the initial reason is just to stay for a short period. However, it turned out that he finally proposed a temporary residence permit [in Malaysia]. Maybe it’s because living there is comfortable, and [they] finally forgot to come back even though the temporary residence permit period has expired. Last year, we also conducted identity checks at the Pading River Immigration Post; there were three people who came from Malaysia. Once we checked the luggage, it turned out he had an Indonesian identity card domiciled in Sebatik and also had a Malaysian identity card.

The data shows that Sebatik residents are very easy to cross the border into Malaysian territory with a cross-border card. This is certainly very helpful for residents who have long had families who have lived in Malaysian territory before the national borders were determined. In addition, this card makes it easier for citizens to carry out other activities in the territory of neighboring countries. However, some people in Sebatik Island believe that the cross-border card policy needs to provide more discretion because it is only valid for three days.

Farmers and fishermen are the primary sources of income for Sebatik Island residents, while others work as laborers, traders, public or private employees, and in other sectors. Sebatik people are very familiar with Tawau (Malaysia) daily because almost all necessities must be purchased in Tawau. Tawau, for them, is a market for all daily necessities and a market for selling all the commodities they own. This is because Tawau is the closest city to the people on the island, despite being administratively outside the Republic of Indonesia’s territory. In other words, the people of Sebatik Island must purchase their daily necessities from outside the country. The relationship between Sebatik Island and the city of Tawau is detrimental to the State of Indonesia and beneficial to the State of Malaysia.

Most of the Sebatik Island community sells their produce to Tawau, including bananas, palm oil, coconuts, fruits, kitchen spices, and other items. However, they also spend most of the proceeds from selling their commodities in Tawau. Tawau is also where most people can get cooking gas, natural stone, gravel, and other supplies. If the two regions’ trade balances are calculated correctly, Indonesia’s trade position in this region is negative. Of course, this is extremely harmful to the Indonesian people. There is a significant distance between Sebatik Island and Tawau City.

Residents on Sebatik Island can get their needs met more easily in Tawau, Malaysia, which is only about an hour away by sea, aside from the lower cost of goods such as sugar, meat, eggs, milk, and even gas cylinders for cooking. It’s no surprise that two currencies are in use there, Rupiah and Ringgit. However, locals prefer to use Ringgit due to its higher value.

Geographically, Sebatik Island is closer to Tawau, which takes only 15 minutes, than Nunukan Island, which takes 1.5 hours and costs three times as much. This difference is felt as a gap by the Indonesians on Sebatik Island, especially at night when they can see Tawau bathed in light with tall buildings. Not to mention the lack of a clean water network that is not yet adequate for all of its citizens, as well as the presence of damaged roads and limited health and education services, all of which contribute to the Sebatik people’s isolation in the face of the neighboring countries prosperity. It also demonstrates Sebatik residents’ reliance on the city of Tawau, where all kinds of daily necessities are more easily obtained. Such circumstances have significant political, social, and economic ramifications.

4.2. Access to get job

Because of the problems that the people of Sebatik Island have, many are looking for work in a foreign country such as Malaysia, which has a direct border with Indonesia. They did it because they needed help finding suitable employment in the Sebatik area. Furthermore, wages generated by workers working in Malaysia were higher than wages received on Sebatik Island.

One of the reasons many people are willing to leave their homes to find work is the large number of oil palm plantations in Malaysia that require farm labor, as well as the proximity of Sebatik Island to the city of Tawau. People looking for job opportunities in Malaysia mostly work in the plantation, trade, and labor sectors. As stated by informant R.J., who is a port official:

The main factor that brings the Sebatik people to Malaysia is to work. Because if we still stay in Sebatik, at most, it is just garden work. Meanwhile, if we cross [to Tawau, Malaysia], we can possibly do many types of jobs. Besides, many work opportunities can be accessed, and the salary value is also higher than here. [Sebatik]

However, many people on Sebatik Island who crossed into Malaysia’s territory face problems. Some of the issues they face in their work are related to their citizenship status as Sebatik Islanders with Indonesian citizenship. Their income would decline as a result, and they will only have limited access to certain Malaysian locations. Due to these circumstances, some Sebatik Island residents who are citizens of Indonesia and work in Malaysia attempt to keep their Malaysian residence cards. As stated by informant DT, Sebatik residents who worked as a speedboat on the Sebatik-Tawau track:

If [you asked if there are any] Sebatik people have Malaysia identity cards, [I will say], yes there is. Because many Sebatik people earn their living in Tawau, they work there. Some of them even have their wives and family there. So they travel back and forth to keep their Sebatik ID. The people who work like that usually have both Indonesian and Malaysian ID cards. The problem is that it is a bit difficult for us if we want to stay there [Malaysia] for a long time and then we are Indonesians. [there are] strict controls [by the Malaysia immigration] there. Due to the ongoing inspection, we cannot engage in free activity or move around. While the administrative process there is very difficult if we want to work [legally] because we are not Malaysians. Unlike my brother-in-law, he has Malaysian and Indonesian ID cards. He has a grocery shop there, sometimes he comes [to visit us in Sebatik] and brings some goods from there, and then he comes back again. He has been there for a long time, about ten years.

People on Sebatik Island who work in Malaysia are not a new phenomenon; they existed for a long time when Sebatik Island was still part of the Bulungan Regency, which has since split into Nunukan Regency, so people’s reliance on Malaysia has already become a part of Sebatik Island community life for generations.

Most people decide to sell their goods to Tawau since there are much greater prices there because it is difficult for locals to sell their seaweed harvest and other items from their gardens in the Sebatik area. In addition, most residents of Sebatik Island tend to spend more time in Malaysia because markets in Tawau are more accessible by speedboat in only 15 to 20 minutes, compared to markets in Nunukan island which will need more time.

People can easily send staple goods in Malaysia to be bought and sold in Sebatik by recognizing them as Malaysian citizens, even covering areas in Nunukan Regency. As stated by CD, who is a local trader;

Supposing we want to buy Malaysian government-subsidized goods, like gas bottles [gas cylinders]. We do not say that we will be brought to Sebatik; we must say the goods will be brought to the Malay River because it is [still] Malaysian territory. If we do not talk like that, we will not be given … . Subsidy goods cannot leave Malaysian territory. Additionally, security officers frequently help us. Because if it is prohibited, it will be impossible for us to obtain affordable and high-quality things here. Meanwhile, almost all crops, even banana leaves, are sent there [Malaysia]. Some brokers can help us with entry access. They will reject it if they discover that the products are from Indonesia. We typically claim that these things are from Malaysia to get our products accepted for sale.

The above data demonstrates how Sebatik citizens, who are also Indonesian nationals, attempt to take advantage of opportunities to acquire a Malaysian identity, such as family members with numerous employment options due to their nationality. Additionally, this region was originally home to families that later developed. However, it later split into two national boundaries, forcing each member of a particular family to separate due to state limits while attempting to maintain their familial ties. They accomplish this, among other things, by holding dual citizenship identities. If it turns out that they must select one citizen, each person will continue to make efforts to develop relationships with relatives in both Indonesia and Malaysia. If it turns out that they must select one citizen, each person will continue to make efforts to develop relationships with relatives in both Indonesia and Malaysia. One day they will be able to take advantage of the many advantageous facilities each country offers, notably job opportunities for their family members.

5. Population administration errors

With its large population, Indonesia necessitates an organized population administration from the center to the regions. Population administration is concerned with all population issues, such as civil registration, birth certificate, family registration card, and other population information management services. The population is becoming increasingly important because it is always in touch with every aspect of Indonesian community life. Among them are voter registration, vehicle documentation, land documentation, social, and economic assistance, and health insurance. If we intend to reside in a specific area, we must have a domicile sign, as evidenced by an identity card.

For some Sebatik locals, the prior civic identity needed to be more relevant. In addition to the complex management process, they believe owning an identity card offers no benefits. However, as administrative procedures for government developed, the Indonesian government eventually required the use of identity cards for all management and public services. As a result, residents of Sebatik started to become accustomed to possessing an identity card for their citizenship.

It is possible to enter Indonesia from Malaysia or vice versa through the Nunukan district (Indonesian territory). Hence Sebatik Island has a route that is often used and is simple to cross not just for Malaysians but also for citizens of Southeast Asian nations like Brunei Darussalam and the Philippines. Many migrants from other parts of Indonesia, such as South Sulawesi, routinely traveled across borders via Sebatik Island. Since 1865, the Bugis tribe has lived in Sabah, primarily in Tawau (Daud, Citation2011).

Additionally, it evolved and grew into the Sebatik region. Before Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore were formed, the Bugis tribe traveled by sea for commerce and lived on the peninsulas of Kalimantan and Sumatra (Lukito & Saat, Citation2023). The arrival of the Bugis in this area culminated in a long-standing relationship between Malaysia and Indonesia in 1967. It made the Tawau area and Nunukan City a trading center (ibid).

Due to the presence of the Bugis communities on this peninsula centuries ago, some families decided to settle in Nunukan Regency. Some formerly acquired citizenship in Malaysia now oversees the populace as Indonesian nationals. SL, an officer of the Agency of Population and Civil Registration, Nunukan Regency, revealed this:

Some people have Indonesian and foreign citizenship on Sebatik Island. Even until we have been processed. This happened because they tended to avoid the administration process of checking the files in the neighborhood unit through the village and sub-district levels. We are vulnerable here because Nunukan Regency is a border area, the entrance to the north is us. The border area between our countries here [in Sebatik] is not as strict as Malaysia. In the past, [there was] the yellow identity card, which was very easy to get. In fact, one person could get up to two or three names [in population data] because our population records were still problematic. But now we already have SIAK [Indonesia’s Population Administration Information System] that just began to be implemented. But it still cannot be said to be perfect because many Indonesian people in Malaysia have not recorded, and they have no documents. This is what borders on having problems within our community. Sometimes a person presents a certificate as [Indonesian citizen], and when we recheck administration data, it is finally known that he has a Malaysian passport.

The information shown above indicates the occurrence of double documentation of population data that does not undergo evaluation. This occurred because data collecting was done manually for a long period before the Indonesian population-based information system was integrated and centralized as it is today. Errors in population administration data are also caused by, among other things, the educational competence of Sebatik District personnel at the village and sub-district levels. According to data from the Central Bureau of Statistics Nunukan (2017), 65 percent of employees in sub-district and village offices in the Sebatik Island region had educational backgrounds, with a maximum of high school graduates. Furthermore, this study discovered that the probability of population administration problems is generated by some citizens handling population administration through brokers rather than visiting the sub-district government office in person. This circumstance may contribute to unreliable data entry, resulting in errors in population data.

Despite faults in population administration, some Sebatik locals believe that dual citizenship is necessary for their living conditions at the border. Some Sebatik residents admit to being recognized as Indonesian citizens because their relatives live in Indonesia and do not want to be separated due to different citizenship. However, it should be noted that others eventually chose to settle as Malaysian citizens. As confirmed by an informant, AR, who is a citizen of Sebatik Island,

… We here do feel more like Malaysian citizens, if you want to say, because all goods circulating here [Sebatik] can be said from there [Malaysia]. But even though some citizens have a Malaysian Identity Card and an Indonesian Identity Card, we still prefer [to be] Indonesian to Malaysian. Citizens with a Malaysian Identity Card are only for work purposes, although there may be other needs. But … I don’t know either … But if [you] asked [me which one I would prefer to be], yes, [I] definitely [will] choose Indonesia. Because of our families in Indonesia, we were born in Indonesia and grew up in Indonesia, and [we] should have also died in Indonesia.

In short, the Sebatik Island People have a common dual citizenship. They believe this is the most appropriate way to survive on Sebatik Island since the Indonesian government needs more commitment to develop their areas and neighboring countries. This situation was confirmed by informant TS, a community leader, as follows:

The dual citizenship of the people on Sebatik Island is not without reason. There must be an underlying reason for [people] behavior that occurs. The reason is that most people are looking for work [opportunities] and to meet [their] basic needs. If they can get such basic needs in their hometown [Sebatik], do they still want to go to Malaysia? I’m sure [they will] not. Here we see the actual role of the government in border areas such as Sebatik. Consider how our basic requirements can be satisfied. Meanwhile, [suitable] access to our port has yet to be created. The port I am referring to here is large, not a small port. Now this is what makes the basic needs of the Sebatik community difficult to meet if you rely on the current government [has been done]. Nunukan, the closest [city] to us, is even difficult to access. At least the road is repaired to arrive at the crossing pier.

This study offers three main prepositions based on the previously discussed factors influencing Sebatik residents to maintain dual citizenship in peripheral regions. First, the meaning of borders. The border is initially a geographical-spatial term and concept, but it becomes a social concept when referring to residents of the border area or those who cross it. The border problem in the geographical-spatial concept is much simpler, as it can be resolved if the two bordering countries agree to meet and concur on the border lines.

However, from a sociocultural standpoint, the significance of borders can be tricky to comprehend. This study explores the sociocultural significance of borders for Sebatik Island’s inhabitants. Most people residing in border regions under both Indonesian and Malaysian jurisdiction are related. Before establishing the current borders, their ancestors lived and traveled along the peninsula. Borders between nations subsequently appeared as a result of applicable laws, and the consequences have an impact on the physical mobility space of citizens, which was not previously an issue. Although there is a territorial border, the emotional connections and familial values of some Sebatik residents developed over a century, do not influence them to continue interacting physically across national borders. They adapt to the current legal climate in various ways, including manipulating identity data and violating the rules.

Nevertheless, from a sociocultural perspective, borders also cause several issues. The issue of socioeconomic disparity between two distinct regions of the country is one of the most pressing issues border residents face. The Indonesian region on Sebatik Island is situated in a remote area and is more accessible from the neighboring Malaysian region than from the neighboring Indonesian region. Accordingly, residents of Sebatik tend to maintain their dual citizenship to access social or economic services offered by the Malaysian and Indonesian administrations.

The second proposition based on the result of this study refers to citizenship identity. Citizenship is synonymous with membership in a political society, cultivating a unique foundation for one’s sense of self-identity. These repercussions include the presence of rights and obligations for citizens. In the case of dual citizenship on Sebatik Island, some citizens who decide to have two citizen statuses with various consequences show an intention to change the citizenship identity of the country into their social identity.

This phenomenon is related to an identity concept that Turner et al. (Citation1987) developed on social identity called the self-categorization theory (S.C.T.). The S.C.T. theory is a social identity theory that postulates an individual’s self-concept and identity are generated not just from the individual’s characteristics but also from the individual’s perceived membership in social groups or categories (ibid). This theory falls under the category of social identity theories. According to the S.C.T., individuals classify themselves into social groups to make sense of the social world and identify themselves concerning the other people around them. This self-categorization process shapes people’s behaviors, attitudes, and relationships with others in their social lives. According to this view, one’s social identity is fluid and contingent on their surroundings. Depending on the circumstances, individuals may identify with various social categories, which can result in many social identities. A person’s identity (at the individual level), their social category identity (at the group level), and their superordinate identity, which spans several categories, are the three degrees of inclusiveness that they may encounter in their social identity (Stets & Burke, Citation2000). In addition, individuals may experience varied levels of inclusiveness in their social identity.

In regions that straddle international boundaries, dual citizenship takes on an increased level of significance. Border regions are home to various communities, many of which have significant ties to other countries, which can lead to complicated social identities. People can identify with both their country of residence and their country of origin in these places, which blurs the lines between national identities.

Self-categorization theory can be applied in the context of dual identity on Sebatik Island to assist in explaining how the people of Sebatik Island manage their social identities as border dwellers, which allows them to have two identities. Residents of Sebatik who live in border areas may simultaneously identify with numerous social groupings, such as the identification of their nation of residence, Indonesia, and the cultural identity of their neighboring country, Malaysia. The connection between these identities can affect a person’s attitudes, behaviors, and interactions with others, particularly regarding fulfilling their socioeconomic demands.

The third proposition relates to self-awareness coupled with considering a logical choice of action expressed either openly or secretly by some residents of Sebatik who have taken advantage of dual citizenship identity. According to Weber’s (Citation1946) viewpoint, this case is rational because some people believe their needs have not been met, and it cannot be easy to obtain. This causes a community to rely on neighboring countries; people frequently cross to meet their socioeconomic needs and will continue to hold dual citizenship identities. The dual identity of any problems that follow it demonstrates its relation to Weber’s (Citation1946) instrumental thinking, namely the pattern of behavior built by society in the form of the most dominant ratio manifested in freedom to determine choices and objectives that are capitalist and merely profit.

This ratio emphasizes the efficiency and effectiveness in achieving these goals, and its application is made in two ways. First, assuming certain objectives to establish alternative routes in achieving other destinations and options that provide benefits, as illustrated in providing self-identity as an Indonesian citizen to meet his needs to double his identity into a Malaysian citizen identity. Second, suppose a perpetrator considers himself free to choose these alternatives. In that case, because the emphasis is on efficiency, this ratio prefers quantitative or number-based results over quality that respects itself as a fully Indonesian citizen with all its limitations.

Lastly, dual citizenship, which some border inhabitants on Sebatik Island experience, can have various political implications in addition to the socioeconomic ones discussed in this paper. For example, in social movements, civil society advocates to increase understanding of the difficulties faced by dual citizenship, emphasize the advantages of dual citizenship, and demand legal changes to consider the complex identities produced by cross-border experiences. The Indonesian Diaspora Network initiated this movement by urging the Government of Indonesia to legalize dual citizenship (Dilahwangsa, Citation2022). Another example is related to election dynamics. The dual citizenship issue has been crucial during elections in Indonesia and Malaysia. Some border residents have dual identity cards, allowing them to exercise their right to vote in elections in both countries (antaranews.com, Citation2017). These findings corroborate Spiro’s (Citation2010) and Vink et al. (Citation2019) studies on the possibility of dual citizens abusing their voting rights in border regions. Dual citizenship is undoubtedly increasingly common and has political implications that might be studied in greater detail in future research.

6. Conclusion

Dual citizenship in border areas can pose unique challenges and complexities due to differing laws, regulations, and cultural norms in each country. Individuals with dual citizenship need to understand and comply with the laws of both countries in order to avoid legal issues or other complications. Dual citizenship can provide numerous advantages but also entails unique challenges that should be carefully considered and navigated.

This study examines the dual identities held by residents of the Sebatik Islands, located in border regions shared by Indonesia and Malaysia. This study argues that the existence of multiple identities among certain residents of Sebatik Island is due to the inability of the government in this border region to improve the quality of public services and the local community’s economic development. In addition, there needs to be more commitment to addressing the community’s economic needs and reducing the economic gap with the adjacent country.

The research also suggests that Sebatik people living in border areas construct their own social identity to conceal their civic identity. They tend to ignore the law and know all the penalties. However, building their social identity as border citizens can further reinforce their social legitimacy over dual citizenship. The citizenship laws of both nations make it possible for citizens who have long engaged in activities that cross-national boundaries to get border cards, which facilitates their social identification as border inhabitants.

Lastly, this study outlines the rationality of the community in determining their choice to depend on neighboring countries by utilizing two citizenships to facilitate obtaining employment to meet economic demands while simultaneously supported by irregular administrative processes in managing border areas. The lack of capacity of local government in border areas leads to further marginalization and exclusion of the population. Community leaders and individuals affected are those most affected by economic and social consequences resulting from the lack of support provided by local authorities due to their dual nationality and the limited capacity to fulfill the population’s needs.

This research has limited methodology because the study was conducted only in Indonesia and did not collect data from Malaysian citizens. Due to limited resources and time constraints, it was decided to focus this study’s examination of the challenges of dual citizenship only on the Indonesian region. It is critical to make clear that this study offers insightful knowledge into the particular setting and experiences inside the Indonesian border region, even though it is acknowledged that Malaysian territory must be included for a thorough analysis.

The results of this study serve as a starting point for future investigations into Malaysian territorial dynamics and comparative analysis of the two nations to improve our comprehension of dual citizenship issues on both sides of the border. In addition, we suggest further studies about the relevance of civic participation and empowerment to promote citizen engagement, active citizenship, and a better quality of life for communities living in border areas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gustiana A. Kambo

Gustiana Kambo is an Associate Professor at Department of Political Science, Hasanuddin University. Her research focuses on political identity, gender study, and politics. She earned her doctoral degree in political science from Airlangga University, Indonesia. Andi Ahmad Yani is a senior lecturer at Department of Administrative Science and researcher at Centre of Peace, Conflict & Democracy (CPCD), Hasanuddin University, Indonesia. His academic works relates to citizenship, public governance and post-conflict governance. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in Dept. of Strategic & International Study, Malaya University, Malaysia.

References

- Administrasi Map of Sebatik Island. (2023). Retrieved 17 July 2023, from https://www.bibitindonesia.com/peta-aksesibilitas-pulau-sebatik-indonesia/peta-administrasi-pulau-sebatik/

- Antaranews.com. (2017) Warga Perbatasan Indonesia - Malaysia Miliki KTP Ganda. Retrieved July 23, 2023, from https://kalbar.antaranews.com/berita/351909/warga-perbatasan-indonesia-malaysia-miliki-ktp-ganda

- Ashirov, B. (2005) Dual nationality acquired under bilateral treaties: The case study of the dual citizenship arrangement between Russia and Turkmenistan [ Master Thesis of Public International Law]. Lund University.

- Askola, H. (2022). Discrimination against dual nationals in the name of national security: A Finnish case study. The International Journal of Human Rights, 26(9), 1630–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2022.2057952

- Bauböck, R. (2003). Towards a political theory of migrant transnationalism. International Migration Review, 37(3), 700–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00155.x

- Bauböck, R. (2011). Temporary migrants, partial citizenship and hypermigration, in citizenship Rights. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 14,665–693.

- Bhagwati, J. (2003). Borders beyond Control. Foreign Affairs, 82(1), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/20033431

- Blatter, J. (2011). Dual citizenship and teories of democracy. Citizenship Studies, 15(6), 769–798.

- Bloemraad, I., Korteweg, A., & Yurdakul, G. (2008). Citizenship and immigration: Multiculturalism, Assimilation, and challenges to the nation-state. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 153–179. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134608

- Campbell, H. (2008). Female drug smugglers on the U-S.-Mexico border: Gender, crime, and empowerment. Anthropological Quarterly, 81(1), 233–267. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2008.0004

- Central Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Regional Statistics of Nunukan Regency 2023.

- Christians, A. (2017). Buying in residence and citizenship by investment. Saint Louis University Law Journal, 62(1), 51–72.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. SAGE Publications.

- Daud, R. (2011). Budaya dan Persoalan Identiti dalam Kalangan Komuniti Bugis di Persempadanan Pulau Sebatik, Sabah (Kajian ke atas Kampung Sungai Aji Kuning, Sebatik Malaysia dan Desa Sei Aji Kuning, Sebatik Indonesia) [ Master thesis]. Universiti Malaysia Sabah.

- Dewansyah, B. (2019). Indonesian Diaspora movement and citizenship law reform: Towards ‘Semi-dual citizenship. Diaspora Studies, 12(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09739572.2018.1538688

- Dilahwangsa, Z. (2022). The conception of dual nationality discourse by the Indonesian Diaspora community in the perspective of social identity theory. Kajian, 27(1), 43–55.

- Fitriani, N. N., Winoto, S. H., & Tyesta, A. L. W. L. (2016). Implikasi Identitas Ganda Penduduk Perbatasan Indonesia-Malaysia di Kabupaten Kapuas Hulu, Kalimantan Barat dalam Perspektif Hukum Internasional. Diponegoro Law Journal, 5(2), 1–12.

- Guild, E. (1996). The legal framework of citizenship of the European Union. In D. Cesarani & M. Fulbrook (Eds.), Citizenship, nationality and migration in Europe (pp: 30–54). Routledge.

- Harpaz, Y. (2019). Compensatory citizenship: Dual nationality as a strategy of global upward mobility. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(6), 897–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1440486

- Heyman, J. M. (2008). Constructing a virtual wall: Race and citizenship in the U.S.–Mexico border policing. Journal of the Southwest, 50(3), 305–333. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsw.2008.0010

- Howard, M. M. (2005). Variation in dual citizenship policies in the countries of the E.U. International Migration Review, 39(3), 697–720. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2005.tb00285.x

- Ingber, M., Muth, C., Hall, N., & The Migrant Crisis at the U.S. Southern Border. (2022). Immigration scholarship: History, trends, and development in global immigration. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/immigrationscholarship/6

- Iordachi, C. (2004). Dual citizenship in post-communist Central and Eastern Europe: Regional integration and inter-ethnic tensions. In O. Ieda & U. Tomohiko (Eds.), Reconstruction and interaction of Slavic Eurasia and its neighboring world (pp. 105–139). Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University.

- Kaelan, & Zubaidi, A. (2007). Citizenship education for higher education. Paradigm Publisher.

- Kalvelagen, A. (2015). Dual citizenship or dual nationality: Its desirability and relevance to Namibia. Dissertation at University of South Africa.

- Kántor, Z. (2005). Reinstitutionalizing the nation – status law and dual citizenship. Regio-Minorities, Politics, Society, 8(1), 40–49.

- Kochenov, D. (2019). The tjebbes fail. European Papers, 4(1), 319–336.

- Kovács, M. M. (2006). The politics of dual citizenship in Hungary. Citizenship Studies, 10(4), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020600858088

- Lukito, L., & Saat, I. (2023). The implications of the Anglo-Dutch treaty of 1824 on the demarcation and economy of Sebatik Island. Melayu, Jurnal Antar Bangsa Dunia Melayu, 16(2), 237–270. https://doi.org/10.37052/jm.16(2)no4

- Macklin, A. (2007). The securitization of dual citizenship. In T. Faist & P. Kivisto (Eds.), Dual citizenship in global perspective: From unitary to multiple citizenship (pp. 42–66). Palgrave.

- Mali, M. G., Suwarjo, S., & Amos, T. R. (2021). Peran Pemerintah Kabupaten Nunukan Dalam Penanganan Identitas Kewarganegaraan Ganda Di Kecamatan Lumbis Ogong Kalimantan Utara. Populika, 9(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.37631/populika.v9i1.349

- Mason, R. (2016). Citizenship taxation. Southern California Law Review, 89(2), 169–237.

- Namadula, B. (2020). An Exploration of the implementation of the dual citizenship act in selected governance institutions of Zambia’s Lusaka District [ Master thesis of School of Education]. The University of Zambia.

- Olena, M. (2017). Security and unsecurity of dual citizenship. Strategic Priorities, 44(3), 29–35.

- Orgad, L. (2019). The citizen-makers: Ethical dilemmas in immigrant integration. European Law Journal, 25(5), 524–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12338

- Pogonyi, S. (2011). Dual citizenship and sovereignty. Nationalities Papers, 39(5), 685–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2011.599377

- Priya, A. (2021). Case study methodology of qualitative research: Key attributes and navigating the Conundrums in its application. Sociological Bulletin, 70(1), 94–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038022920970318

- Pudzianowska, D. (2017). The complexities of dual citizenship analysis. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 6(1), 15–30.

- Ramos, C., Lauzardo, P., & McCarthy, H. (2018). The symbolic and practical significance of dual citizenship: Spanish-Colombians and Spanish-Ecuadorians in Madrid and London. Geoforum, 93(6), 67–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.05.007

- Sangkala, Burhanuddin, A., & Yani, A. A. (2019). An Environmental analysis of Human security at border communities in Sebatik Island of Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 343(1), 012093. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/343/1/012093

- Sejersen, T. B. (2018). I vow to thee my countries–the expansion of dual citizenship in the 21st Century. International Migration Review, 42(3), 623–649. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2008.00136.x

- Smith, M. P., & Bakker, M. (2011). Citizenship across borders: The political transnationalism of El Migrante. Cornell University Press.

- Spiro, P. J. (2010). Dual citizenship as human right. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 8(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mop035

- Spiro, P. J. (2019). The equality paradox of dual citizenship. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(6), 879–896. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1440485

- Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695870

- Sudiar, S. (2012). Kebijakan Pembangunan Perbatasan dan Kesejahteraan Masyarakat di Wilayah Perbatasan Pulau Sebatik, Indonesia. Jurnal Paradigma, 1(3), 389–401.

- Tilly, C. (1995). Citizenship, identity, and social history. International Review of Social History, 40(S3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859000113586

- Torabian, P. (2019). Look at Me! Am I a Security Threat?!”: Border Crossing Experiences of Canadian dual citizens post 9/11 [ Thesis at the University of Waterloo]. Received on 25th of March 2023 http://hdl.handle.net/10012/15049

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell.

- Veronika, N. W. (2016). Regional Economic Integration for Improving Cross-Border Area in Sebatik Island. International & Diplomacy, 2(1), 69–82.

- Vink, M., Schakel, A., Reichel, D., Luk, N. C., & Groot, G. (2019). The International diffusion of expatriate dual citizenship. Migration Studies, 7(3), 362–383. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnz011

- Weber, M. (1946). Essays in sociology. Oxford University Press

- Yani, A. A., & Hidayat, A. R. (2018). What is the citizenship quality of our community? Measuring active citizenship. Public Administration Issue, 12(6), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.17323/1999-5431-2018-0-6-119-133

- Yani, A. A., Sangkala, S., AT, M. R., Burhanuddin, A., & Ahmad, B. (2019). Youth and nationalism in Indonesian border community. Journal of Humanity and Social Justice, 1(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.38026/journalhsj.v1i1.3

- Yin, R. (2014). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.