Abstract

This study aims to explore the values and conservation threats of Nazugn Mariam monolithic rock-hewn church, a typical instance not only show the country’s long forgotten, ill-considered and endangered ancient rock-hewn churches in the rural areas but also its underdeveloped heritage management system. The study employed both primary and secondary sources which were collected through field observation, interviews and review of written sources. The result of the study showed that the monolithic rock-hewn church of Nazugn Mariam entails significant environmental, spiritual, historical, and architectural values which are not known due to its remoteness. However, this important hypogeum is continually deteriorated due to natural agents such as torrential summer rainfall at one time and sunlight at the other time. Besides, locally practiced repairing works are unwise which neither restore lost architectural features nor effective in sustaining the hypogeum in its current situation. New retrofitted materials like concreted basaltic stone are completely uninformed interventions that not only could not have restored lost values but also endangering this important hypogeum, calling for urgent collaborated restoration work. The conservation problems of this hypogeum attest the country’s poorly developed cultural heritage management system that couldn’t reach out cultural heritage in the remote areas.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Many developing countries like Ethiopia have great aspirations to support their fragile economies through the profit of the fast-growing tourism industry, which is mainly reliant on heritage resources. However, this industry is still at its infant level since the aspiration is not usually backed by the documentation, conservation, and promotion activities of the basic resources of the industry. The destruction of cultural heritage due to unmanaged deteriorative factors threatens the basic resources of the industry, as evidenced at the monolithic rock-hewn church of Nazugn Mariam. Therefore, due attention is needed from the government and other stakeholders to properly protect these priceless cultural values. This needs creating an enabling environment that supports the development of cultural heritage at the national level, and then the return will be gaining profit from the industry.

1. Introduction

The desire of humans to own, conserve, and use cultural heritage among communities emanates from its multitude of values, which can be generalized into two unfurled categorizations: socio-cultural value (which includes historical, symbolic (cultural), social, spiritual, aesthetic, and political values) and economic value, in which heritage can be marketed to generate economic significance (Mason, Citation2002, p. 10). Managing cultural heritage becomes important as these values are irreplaceable and multidimensional. However, in most developing nations, sustaining heritage values is thwarted by a poorly developed cultural heritage management system that encounters different awful or untoward constraints such as a lack of funds, technologies, and skilled manpower in the field of heritage management. The priority given to heritage values is also low, and the usage of resources is mainly unplanned and haphazard (Mabulla, Citation2000, p. 212; Chirikure, Citation2010, Citation2013, pp. 1–2; Ndoro, Citation2016 −396;, pp. 394; Keitumetse, Citation2016, pp. 1–2). The statement under Letellier (2007), “the destruction of cultural heritage is faster than it can be documented”, reflects how the conservation of cultural heritage is serious at global level.

Ethiopia is endowed with an enormous cultural heritage that ranges from the world’s earliest human stone tools, which date back to 3.1 million years ago (McPherron et al., Citation2010) to the monumental and obelisk structures that marked the architectural apogee of the country (Mercier & Lepage, Citation2012; Phillipson, Citation2009). However, the country lacks a well-developed cultural heritage management system. The use and sustainability of its cultural endowments for tourism development are thwarted by the limitations in the practices related to exploration, promotion, and conservation of its potential cultural values. These limitations are partly associated with the impracticality of cultural heritage management strategies due to the lack of skilled manpower and financial support (Ebabey, Citation2019, p. 86; Feseha, Citation2012, p. 3). Moreover, the absence of an emphasis on cultural heritage management at the country level is another problem for the underdeveloped condition of cultural heritage management. This problem is associated with the country’s administrative structure, which grants protection of cultural heritage to federal and regional governments. The management of most of the country’s cultural heritage (except for those registered as world heritage) is given to regional governments (Federal Negarit Gazeta, Citation2000, p. 7517). This structure is forged along ethnic lines, which has affected the valorization and management of cultural heritage as a shared value. Due to this, the national identity of Ethiopian cultural heritage no longer exists because of the extolling of ethnic-based identities (Blanc & Bridonneau, Citation2016, p. 15). The existing political stream is an impediment to the conservation of cultural heritage as a shared national value, and this has a direct contribution for the underdeveloped stage of the tourism industry at the national level.

Simultaneously, the regional and local culture and tourism bureaus are not empowered with financial and skilled manpower resources to explore, document, conserve, and promote cultural heritage in remote areas of the country. Due to this, incredible cultural heritage in rural areas of the country is ill-considered and left for destruction because of different causes. In other words, the management of cultural heritage sites in remote areas of the country is compromised by their remoteness (for the sake of this study, remoteness implies an area that is inaccessible, far from urban centers, and that lacks basic infrastructure such as roads). Negligence in the management of cultural assets compromises the economic benefits that the country can gain from the tourism industry and bereaves priceless cultural values due to the absence of protection practices (Ebabey, Citation2019 −87;, pp. 86; Gebreegziabher et al., Citation2019, pp. 2–3). The absence of viable cultural heritage research and conservation practices is the main challenge for cultural sites found in remote areas of the country. The condition of cultural heritage management at the Nazugn Mariam rock-hewn church (Meket District, North Wollo) is a typical example of a long-forgotten, ill-considered, and endangered cultural heritage in Ethiopia. A preliminary record has been reported by the author (Ebabey, Citation2018). However, there is a gap in providing detailed explanations of its values and conservation practices in a wider context, and the conservation problem of such a remote heritage value is still beyond the capacity of the local communities, who are calling for potential stakeholders to support local initiatives to rescue this endangered rock-hewn church.

By examining the country’s policy perspective in protecting and using cultural heritage, this inquiry, therefore, focuses on the cultural heritage management issues of Nazugn Mariam (Nazugn St. Marry) rock-hewn church as a case study for some reasons. First, it is the only surviving monolithic hypogeum, but is now found to be an endangered remote cultural value found in a rural area in Meket District, Northern Ethiopia. Second, the rock-hewn church bears significant but little-known values. Third, its values change continuously because of different deteriorative factors than other rock-hewn churches that have been surveyed in South Gondar and North Wollo. As a case study, this site signals the nature of deteriorative causes and consequent damage to ancient rock-hewn churches, as well as the gaps and impacts of unwise conservations taken to cure damages. Fourth, the hypogeum is still actively used as a worshiping center for local communities. Finally, it is a good example to show the impact of the absence of governmental or other stakeholders’ support on locally initiated and conducted conservation endeavors in the management of the cultural heritage of the country. Thus, this article assumed the message to reach out to the wider academic and heritage management communities, looking for a collaboration to safeguard Nazugn and other endangered cultural sites to sustain such sites for the benefit of local communities as a center of spiritual practices and destination of domestic and international tourists.

2. Ethiopian Rock-hewn Churches

2.1. General characteristics

Different travelers and scholars have left their observations of ancient Ethiopian churches from their historical, liturgical, and architectural perspectives. Most of the observations are fascinated with churches and monasteries that are hewn out of solid rocks (Alvarez, Citation1881; Findlay, Citation1943; Buxton, Citation1947; Bidder, Citation1959; Pankhurst, Citation1960; Gerster, Citation1970; Heldman, Citation1992; Schuster, Citation1994; Plant, Citation1995; Finneran, Citation2007; Phillipson, Citation2009; Gobezie, Citation2012; Mercier & Lepage, Citation2012, to mention few). Most of these works are concentrated on the rock-hewn churches of Tigray, Lasta, and Shewa. However, as the author’s fieldwork (since 2013) shows, there are other groups of rock-hewn churches that have escaped the notices of scholars in the Meket, Lay Gayint (South Gondar), Wadla, and Dawnt (North Wollo) districts. Spatially, various numbers and types of rock-hewn churches dominate the Christian landscapes of northern and central Ethiopia. Distribution decreases as one moves to the southern part of the country. Some of the reasons for the northern concentration of these kinds of churches are the inaccessible rugged landscape that is suited for monastic habitation and the availability of easily excavating rocks (Gobezie, Citation2012, pp. 35–36; Phillipson, Citation2009, p. 87).

The excavation of churches from rock was well established until the fifteenth century, when the tradition began to have been replaced by round masonry (built) churches (Binns, Citation2017, p. 74, 77). Typologically, Ethiopian churches that are hewn out of bedrock are referred to as hypogea (hypogeum for single), which means rock-hewn features, which can be used interchangeably (Phillipson, Citation2009, pp. 87–88, 206). Based on their degree of detachment from the main rock and excavation system, these types of churches can be categorized into monolithic, semi-monolithic, and caves (Finneran, Citation2007, p. 215; Gobezie, Citation2012, p. 37). Monolithic churches are freely standing monuments “just rising from an excavated court” (Phillipson, Citation2009, p. 87). Semi-monolithic churches are also partially excavated from rock faces of various degrees (Gobezie, Citation2012, p. 37) and they have varied architectural elements on their modified sides. Caves are features that are cut inward from rock faces with little modification of their exterior rock (Gobezie, Citation2012, p. 37; Phillipson, Citation2009, p. 87). Ethiopian cave churches, unlike most of their counterparts in Byzantine, are not karstified caves; they are completely representative of human workmanship (Ebabey, Citation2020, p. 235). Churches built under natural caves or on mountain tops are grottos or ordinary buildings (Gobezie, Citation2012, p. 37). They are also referred to as conventional types but can be seen in the context of rock-hewn churches as long as they resemble the similar architecture and liturgical function as hypogea (Phillipson, Citation2009, p. 87). From their religious symbolical perspective, cave and monolithic churches represent Christ’s cave birthplace at Bethlehem and the rock-hewn tomb at Golgotha, respectively (Gobezie, Citation2018, p. 43).

Historically, Ethiopian rock-hewn churches have a special character, mainly because of their religious symbolism, long history, cultural continuity, prolongation, and uninterrupted spiritual service. The construction of churches from rock traces their roots to the early tradition of Christianity. In the course of the history of Christianity, the birth and burial caves of Jesus Christ, among others, were symbolic (biblical) instruments for the expansion of rock hewn churches out of bedrock. Ethiopian rock hewn churches have also grown out of this symbolic and religious connection (Gobezie, Citation2012, p. 35).

The construction of churches in Ethiopia has a long history. The earliest evidence of ancient church buildings traces back to the official conversion of King Ezana into Christianity in the fourth century A.D. One of the earliest churches constructed during this period was the Aksum Tsion Mariam, the Ethiopian mother church (Phillipson, Citation2009, p. 30, 38, 39, 195). A recent study reveals that Aksumite’s official adoption of Christianity was second in the world; only Armenia preceded it. This situation characterized the expansion of Christianity in the form of a top-down process (Finneran, Citation2007, p. 181). It inspired the construction of churches and the transformation of pre-Christian Aksumite cultural elements (such as the architectural features of the Aksumite steles) into Christianized elements that continued to be used as sacred architecture of Ethiopian Christianity (Finneran, Citation2007, p. 183, Citation2012, pp. 248–249). Hence, the architectural elements (false windows and doors, monkey heads, beams, and top arches) of the famous Aksumite stele were frequently reproduced during and after the Christian Aksumite period’s cultural developments.

In the late fifth and sixth centuries, the expansion of Christianity and the construction of churches took place as far as South Arabia, where a short-lived Aksumite Christian rule was established by King Kaleb (Henze, Citation2000, pp. 40–41). The coming into the Aksum of the Nine Saints led to the expansion of ascetic life, which was dominantly practiced in inaccessible rocky environments where churches have been excavated. Most have established monasteries that are still flourishing and bearing their names. Unlike Byzantine monasticism, which was practiced in natural caves (Finneran, Citation2012, p. 257), monastic activity in Aksum was characterized by the excavation of rock-hewn churches and chapels that are still flourishing (Finneran, Citation2012, pp. 257–264; HableSellasie, Citation1972, pp. 118–120; Henze, Citation2000, p. 38; Weyer, Citation1973, p. 10). Most of the churches are excavated from hard sandstones and are characterized by the extensive adaptation of pre-Christian Aksumite cultural elements, such as wall beams, arches, and wooden framed windows and doors (Phillipson, Citation2009, pp. 106–107).

The excavation of churches from the rock continued during the post-Aksumite period in a special manner. Following the shift of the Aksumite center somewhere in the south in the 10th century A.D., construction and excavation of churches resumed under the leadership of the Zagwe rulers (c.930–1270) (Negash, Citation2006, pp. 128–132). This period was historically significant for its contribution to the famous rock-hewn churches of Lalibela and many others found in the area. These churches are important evidence for understanding the history of extensive Christianization during the Zagwe period (Henze, Citation2000, pp. 52–53). The apogee of rock-hewn-oriented architectural and engineering legacies belonged to this period (Finneran, Citation2007, p. 267; Gobezie, Citation2012, p. 91). Since the 16th century, several travelers and scholars have moved towards these wonders, which were registered as the first 12 world heritages of UNESCO in 1978 (Bosc-Tiessé et al., Citation2014, p. 142; Phillipson, Citation2009, pp. 199–202).

The churches of Zagwe bear Aksumite architectural elements, such as basilica plans, monkey heads, beams, and false windows. For instance, it has been shown that Bete Medhane Alem at Lalibela follows the plan of the original church of Aksum Tsion Mariam (Buxton, Citation1947, p. 28; Heldman, Citation1992, pp, 230–231). Moreover, the church of Yimrhane Kirstos that precedes Lalibela is the finest replica of the Debre Damo monastery, in light of the architectural excellence of Lalibela churches (Buxton, Citation1947, p. 8, 18–19). After the 13th century, in the era of the Solomonic dynasty, unlike the extensive development of monasticism and literature, the excavation of churches continued to decline (Ebabey, Citation2020, p. 234; Gobezie, Citation2012, pp. 93–94). However, the tradition was not fully forgotten as in some examples (such as Genete Mariam, a replica of Bete Medhane Alem, Lalibela), even though some Aksumite cultural elements have been found in different parts of the country (Phillipson, Citation2009, pp. 112–118). The caves of Abba Giyorgis of Gascha in South Wollo and the cave church of Abba Aron in Meket, southwest of Lalibela, are also worth mentioning (Ebabey, Citation2020, pp. 238–250; Wright, Citation1957, pp. 7–13). By contrast, conventional buildings began to dominate the culture of the post-Zagwe period (Phillipson, Citation2009, p. 25). However, we have rare examples of these types because of their exposure to destructive agents such as war.

2.2. Conservation practices and problems

As reviewed above, a number of studies have revealed ancient Ethiopian rock-hewn churches from historical, archaeological, and art perspectives. However, literature on the cultural heritage management aspect of these sites is scant. This does not mean that the rock-hewn churches are not subjected to conservation-related problems. Of course, most of the surviving ancient Ethiopian churches are of the rock-hewn type. There are several reasons for this. First, as Rewerski (Citation1995, p. 12) mentions, rock caves were an “impregnable form of shelter;” the rocks from which the churches were excavated were initially indomitable and relatively durable to resist natural and man-made threats than their contemporary building materials. Second, most rock hewn churches are established in a relatively stable (rocky) environment, which is less vulnerable to natural hazards, such as landslides, earthquakes, and floods. Third, most rock-hewn churches and some conventional types are constructed in inaccessible areas that hide churches from raiders during a war. Finally, Ethiopian rock-hewn churches are living monuments that still serve as main centers of worship (Gerster, Citation1970, p. 51). This may have contributed to the increase in the number of churches.

Despite this, apart from the bondage of time, impregnable ancient rock-hewn churches are now subjected to destruction because of different factors. Here, the review focuses on conservation problems and practices based on available literature, which are mainly concentrated on Lalibela rock-hewn churches (see Delmonaco et al., Citation2010, pp. 138–146; Gemeda et al., Citation2018, pp. 1–12; Gobezie, Citation2012, pp. 114–120; Negussie, Citation2010, pp. 76–81). The discussions by Delmonaco et al. (Citation2010, pp. 138–146) show the negative impact of weathering processes (including biological elements) on the architectural and structural features of rock-hewn churches. Negussie (Citation2010, p. 78) also showed the impact of erosion and water infiltration into rock-hewn churches and the need for management, and proposed a management plan integrating multi-stakeholder involvement to bring progress in heritage protection, tourism, and community development in Lalibela.

Gobezie (Citation2012, pp. 114–122), on the other hand, discussed the factors contributing to the conservation problems of Lalibela rock-hewn churches as natural and man-made agents. He indicated that salt crystallization formed on the rock surface and that sunlight, rainfall, insects, tree roots, algae, mosses, and lichen are among the natural factors contributing to the deterioration of churches. Gemeda et al. (Citation2018, pp. 3–11) also conducted detailed research showing the threat of biological agents, such as the growth of lichens and other microorganisms on the facades of churches. The conservation problems of rock-hewn churches in Lalibela and Tigray (such as Wukro Kirqos) were also assessed by Weldegiorgis (Citation2018). He discussed the conservation problems from different perspectives, including the identification of the sources and degree of deterioration, assessing the knowledge of local communities about the sources of deterioration of the rock-hewn churches, and the local practices in conserving deteriorated sites.

Despite the lack of specifically categorized discussions, Weldegiorgis stated that poor management, rainfall, bad conservation, and biological elements such as algae, lichen, and mold were factors in the conservation problems of the rock hewn churches in the aforementioned areas. He also adds that the neglect to take immediate and appropriate management activities and unwise local interventions worsen the conservation status of churches.

The other point is conservation practices intended to protect rock-hewn churches from deteriorative agents and maintain the lost values of churches. In relation to this, Gobezie (Citation2012) and Weldegiorgis (Citation2018) attempted to show the practice of heritage conservation of rock-hewn churches, mainly in Lalibela. According to Gobezie (Citation2012), the previous interventions made on Lalibela rock-hewn churches tend to have more negative impacts on sustaining them. Most of the interventions were unwise and made at the cost of the aesthetic values of the churches, as has been clearly seen in Bete Amanuel, one of the famous rock-hewn churches of Lalibela. Until this day, shelters constructed over the roofs of monolithic rock-hewn churches were found to be a great risk to church survival. Weldegiorgis (Citation2018) similarly showed the negative impact of unwise intervention in the rock-hewn churches found in Lalibela and Tigray. Most of the problems related to intervention practices are related to the absence of support for local initiations to conserve or repair damaged rock-hewn churches.

Recently, a preliminary study on the conservation problems of long-forgotten rock-hewn churches found in South Gondar, North Wollo, and Shewa was conducted by Ebabey (Citation2018, Citation2019). These records attempted to reveal the conservation problems of rock-hewn churches (including Nazugn Mariam), which are mainly found in the rural areas of the country. However, the values that are compromised due to conservation problems and the seriousness of their conservation status are not discussed in detail. This study, therefore, aims to illustrate the multitude of values and the existing challenges of conservation activities of Nazugn Mariam as a case study and recalls the need for the support of governmental authorities in the local management efforts on remote cultural heritage in the country.

3. Methodology of the study

3.1. Location and geographical context

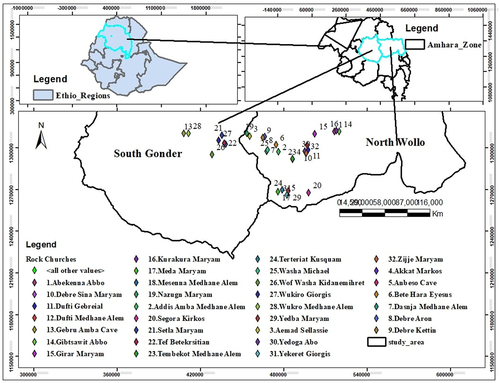

The rock-hewn church of Nazugn Mariam is one of the remote cultural sites found in the Meket District in North Wollo, Northern Ethiopia. It is located 105 km west of Lalibela, and 645 km north of Addis Ababa. Physically, the vicinity of the church is characterized by an impressive rugged topographical setting that formed the western part of the upper course of the Tekeze River (Ebabey, Citation2018). The Checheho chain, which extends from Checheho Medhane Alem in South Gondar to North Wollo as far as the head of the Zhita River, a tributary of Beshilo that flows towards the Abbay River, overlooks the church and its vicinity. The area was the main corridor and encampment of Gondarine rulers in their march to Wollo (Allen, Citation1943, p. 2; Crummey, Citation1975, p. 2). Hidden under cliffs and mountains, more than 30 rock-hewn churches (of which 19 are found in Meket) are found across the Checheho escarpment that covers different districts, such as Lay Gayint, Meket, and Wadla (See Figure ).

Figure 1. The distribution of rock hewn churches across the Checheho escarpment.

Demographically, Meket is the most populous district in the North Wollo Zone. According to CSA (2007), its population is 226,644, constituting 15.1% of the zone’s total population. Most of the population (95.25%) adhered to Orthodox Christianity. Economically, over 87% of the population lives in rural areas, depending on the traditional subsistence farming system, which relies on less productive and degraded farmlands. Therefore, local communities are exposed to seasonal famine and food shortages. Infrastructure, including rural roads, is poorly developed in the area (Aklilu, Citation2013, p. 4; Kassa, Citation2012, pp. 19–20).

3.2. Data collection techniques and analysis

This study employed a qualitative research approach with a descriptive research design. The study data included both primary and secondary sources. The primary sources of the study included data related to the physical features (architectural and structural features, as well as treasures) of the Nazugn Mariam Church. These sources were collected through field observations that covered a survey of rock-hewn churches across the Checheho escarpment in South Gondar and North Wollo. The data used in this study were collected between September 2013 and June 2021. In recent years, more than 30 new rock-hewn churches have been explored across this area. During fieldwork, instruments such as GPS, photography, and notebooks were used to record the observation results. In the fieldwork at Nazugn Mariam in 2021, the visit was accompanied by two interested visitors who were probably the first foreign visitors to the area. Discussions were held with the local communities regarding how the project undertaken to shelter the church was challenging.

The secondary sources of the study included data related to the historical and conservation practices of the church. These data were collected through interviews and examination of written sources (both published and unpublished). Interviews were conducted with informants who were selected purposefully for their better knowledge of the historical and conservation practices of the church. Officers from the culture and tourism bureau of the district, as well as other individuals who participated in the repairing works, were also interviewed to collect data related to the conservation practices of the church. To obtain a wider picture of the study, literature related to the general features and conservation issues of Ethiopian rock-hewn churches were also reviewed. In addition, the available archives found in this area were consulted. Gedle Abune Muse (Life of Our Father Moses) provides hints about the history of Nazugn Mariam and many other churches. For this purpose, copies of this parchment book were accessed at Nazugn Mariam and Addis Amba Medhane Alem in the Meket District. The source collected using the different methods were described and analyzed qualitatively.

4. The Rock-hewn Church of Nazugn Mariam: the values and challenges of its remoteness

4.1. Values of the Rock-hewn Church

4.1.1. Environmental values

Unlike its remoteness, the rock-hewn church of Nazugn Mariam has value, including its topographical features. As mentioned above, the church is located along the upper western course of the Tekeze River. The vicinity of the church is characterized by a reddish and uneven topography (dominantly hills and gorges), which is part of the gorge of the Zoga River that flows towards Tekeze. Its vicinity reflects the impressive physical landscape occupied by small rural villages. The area is part of a temperate ecological zone and hosts one of the few protected groups of indigenous trees and bushes that are concentrated around churches and monasteries (see Figure ). In this context, Nazugn Mariam has significant environmental value, including its topographical setting and its role in preserving local old-growth trees, protecting land degradation, and reserving underground springs that are used as sources of water and holy springs for local communities.

4.1.2. Religious and social values

In the case of Ethiopia, churches and monasteries are closely related to their local communities, who frequently gather in churches for spiritual, social, economic, and health purposes. Nazugn Mariam is still used as a place of worship by local Christians. In addition to its everyday rituals and mass practices, the church has annual and monthly religious ceremonies in memory of St. Mary’s rest, which was celebrated annually on January 29. Such celebrations are usually accompanied by social gatherings such as zikir (a feast in the memory of a saint), which are considered sources of social bonds that strengthen social development and harmonious relationships among local communities. The church also has a special place in the hearts of the locals, because it is where their ancestors’ bodies are laid to rest. In addition, for Ethiopian Christian communities as a whole, a rock hewn church is cherished for its symbolic value, which has biblical references. As mentioned earlier, these features symbolize the rock-hewn grave of Jesus Christ, as Matthew (27, 60) tells us: “When Joseph had taken the body, he wrapped it in a clean linen cloth and lay in his new tomb that he had hewn out of the rock.” From this perspective, the rock-hewn church of Nazugn Mariam is considered to have religious values.

4.1.3. Historical values

Relying on the records of local traditions, the church of Nazugn Mariam has an important historical narration. The local oral sources acquaint that Nazugn Mariam was one of the churches built by Abune Muse during the reign of King Ezana in the fourth century A.D (Ebabey, Citation2018). The life of Abune Muse also mentions that the church was constructed by Abune Muse, as it reads: “ወእምዝ አደወ ፈለገ ዞጋ ወሐነፀ በደብረ ናዙኝ… [And then, he (Muse) crossed the River of Zoga and carved on the hill of Nazugn…]” (Gedle Abune Muse, page 151).

Despite the absence of more substantial sources, it is possible to provide some descriptions of the life of the church’s hewer based on available local sources. The local oral tradition and Gedle Abune Muse confirm that Abune Muse (also Selama Kal’e or Selama II) was a bishop who succeeded Abba Selama or Frumentius, the first bishop in the Aksumite Kingdom. He was anointed by Athanasius, Patriarch of Coptic church, in the fourth century A.D. (Gedle Abune Muse, p. 149), as indicated in the life of the bishop as quoted as follow:

ወሶበ ሰምዐ ሊቀ ጳጳሳት ዕረፍቶ ለአቡነ ሰላማ ኀዘነ ዐቢየ ኀዘነ፡፡ —ወእምዝ ኀሠሠ መንገለ አስቄጥስ ብእሴ መንፈሳዌ ዘይከውን ለሢመት ወኀረየ እምነ መነኰሳት ዘገዳመ አስቄጥስ ወበህየ ረከቦ ለዝንቱ ብፁዓዊ ሙሴ ጻድቅ፡፡ ወመነኰሳትሂ ሠምሩ በሢመተ አቡሁ ወበዘዚአሁ፡፡ [When the patriarch (Athanasius) heard the death of our Father Selama, he felt much melancholy. … After this, he inquired about a strong spiritual man among the monks of the monastery of Scetis who could suffice for the appointment. He found Muse the truthful whose appointment was acknowledged by the monks]. (Gedle Abune Muse, p. 148)

According to Gedle Abune Muse, the bishop was born to early Christian families named Yostos and Soliana, whose wedding was blessed by the presence of Jesus Christ, St. Marry, and the Apostles at Cana of Galilee (John 2, 1–11). According to this tradition, Abune Muse was the Hebrew of his origin. His life also mentions that Muse became the governor of Egypt, where he later took a preferred monastic life at the monastery of Scetis (Macarius). However, in most scholarly sources other than mentioning his name Minas, it is difficult to find detailed information about the historical background and deeds of the bishop in Ethiopia. The available literature has relied on local traditions. In the bishop order of Ethiopia, Minas is mentioned as the second bishop (Nosnitsin, Citation2007, p. 971; Tamrat, Citation1972, p. 110; HableSellasie, Citation1972, p. 7). Muse is also available in some literature (Balicka-Witakowska, Citation2010, p. 1150; Fiaccadori, Citation2007, pp. 1080–1081; Zeleke, Citation1975, p. 85). As Frumentius’ had different names, Abune Selama and Kesate Berhan, Abune Muse was also known by his other names, Selama Second and Minas. We have little information about the contribution of Muse and other bishops after Frumentius.

The churches that bear Abune Muse were excluded from the research scholarship on Ethiopian rock hewn churches. First, unlike Frumentius, who grew up in Aksum and experienced the culture of the local society, most other bishops lived as strangers and had no exposure to understanding the culture of local communities. This would create a problem in engaging in translation works by which Frumentius (and even some others) became well known. However, Muse might have spent his time constructing rock-hewn churches, which are now found bearing his name. This exploration of the local narration that places the hypogeum during the Aksumite period is significant and will be another destination for researchers engaged in establishing the chronology of Ethiopian rock hewn churches and tourists who are fascinated with historic and religious monuments. Second, most of the rock-hewn churches that are locally ascribed to Abune Muse are located in remote and inaccessible areas, which might have obscured these sites from scholars and visitors. According to HableSellasie (Citation1970, p. 110), the fifth-century history of Ethiopian Christianity is unclear. This period might have been partly associated with Abune Muse’s heading of the Ethiopian Church.

4.1.4. Architectural values

4.1.4.1. Exterior architectural features

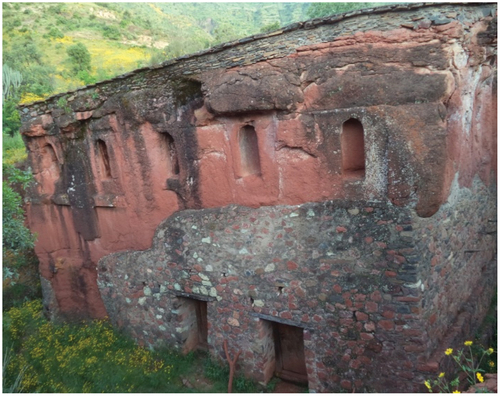

Nazugn Mariam is the only obvious monolithic rock-hewn church identified in the Meket District. The church was excavated from a reddish bedrock. It stands freely out of a deeply excavated court (Figure ). It had a rectangular shape measuring 15 × 10 m and a height of 10 m. The trenches are excavated in two directions: the draining system and gateways for people. The courtyard of the church was formed as a result of the downward excavation process to attain a monolithic feature sunken into the ground.

Despite the profound deterioration, the hypogeum has four facades that are well decorated with different architectural frames. The facades bear similar architectural elements, including false and framed windows and horizontal and vertical beams, which are quite common in other rock-hewn churches, such as Bete Abba Libanos in Lalibela (see Figures ). All the facades shared similar architectural characteristics, resembling good workmanship. They are refined with vertical pilasters and a single horizontal beam that surrounds the mid-part of the rock-hewn wall and windows framed with Aksumite styles. However, in its current situation, the western façade of the church lacks architectural elements because of the structural and architectural deteriorations it faces. The eastern facade of the church is found to be in good condition, and it gives a general picture of the architectural elements of the rock-hewn church in its original context (see Figures ).

The church has three doorways on its southern and northern facades. They have rectangular shapes but lack frames such as corner posts, which are common in Aksumite and post Aksumite rock-hewn churches. They are repaired, and it may be difficult to state the original architectural features of these doorways. There were also 16 false (blind) results and one open window. The remaining windows imitate false window features, which are typically Aksumite. These windows were carved integrals into the rock, and no wooden elements were introduced as enclosures or frames. Five of the false windows were projected along the northern facade, and five additional windows were similarly carved along the southern facade. Three blind windows were also carved on the western side, and the other three were carved along the eastern side.

All windows have a rectangular shape at the bottom, an arch, and pointed features at the top. However, these windows lack Aksumite “monkey head” styles (corner-protruding features). The style of these windows is akin to the architectural features of Bete Abba Libanos in Lalibela, Zoz Amba Giorgis in Belesa, North Gondar (See Gervers et al., Citation2014, pp. 198–120; Phillipson, Citation2009, pp. 143–144) and Gibtsawit Abbo in Meket, despite the fact that the windows of the first two churches are not false.

4.1.4.2. Internal divisions and features

The hypogeum was designed internally in a basilic style. It is partitioned into liturgical rooms in an eastward arrangement, which is a common tradition in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. As described by Phillipson (Citation2009), this internal division is based on the liturgical services performed in the Orthodox Christianity of Ethiopia. The internal divisions of this church include kine-mahlet (chanting-room), kidst (holy), and mekdes (sanctuary), which are used to sing hymns, provide Holy Communion to believers, place the altar of the Ark of the Covenant, and sing the mass. These partitions are composed of rows of rock-hewn pillars that form aisles between them. The columns were thick and rectangular. However, unlike pillars in most rock-hewn churches of the country, they lack capital, arcades, and entablatures, which are the predominant decorative features of pillars.

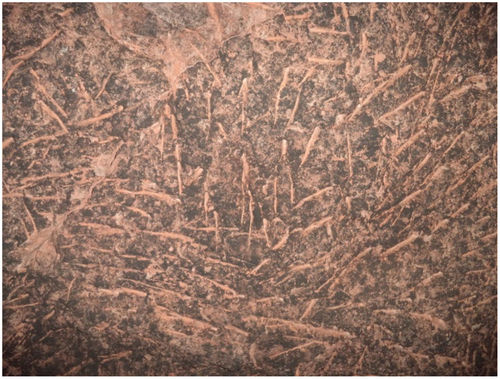

Internally, the roof of the church is predominantly characterized by recurring marks of chiseling (see Figure ), which show the employment of local excavation instruments such as an ax. These marks are common in the rock-hewn churches of Meket and other areas. These tool marks are important for understanding the construction technologies employed to carve rock-hewn churches in Ethiopia. Very rarely, the roof of the sanctuary is better decorated with amde work, a circular protruding feature carved on the roof immediately above the altar. Generally, it is plausible to conclude that the hypogeum manifests significant architectural value that contributes to the historical development of Ethiopian architecture.

4.2. Threats and Local Conservation Practices of Nazugn Mariam Hypogeum

The monolithic church of Nazugn Mariam, as discussed above, has significant environmental, religious, historical, and architectural value. However, the hypogeum has profoundly deteriorated, and it can be considered an endangered rock-hewn church that tattles the poor cultural heritage management system of Ethiopia. This deterioration appeared in terms of architectural and structural damage. Natural and anthropogenic factors contribute to the deterioration, of which the former appears to be the major contributor.

4.2.1. Natural Factors: Weathering process (rainfall and sunlight) and the impacts thereof

The weathering process (high rainfall at one time and sunlight or dryness at the other time) is the main natural factor for the deterioration of this incredible hypogeum. During the summer season, rainfall droplets fell on the church and gradually hollowed out different parts of the rock. Because of the heavy rainfall in the region during the summer season, water collects on the roof and trickles through the cracks, aggravating the deterioration. Except for the eastern side, all facades were affected by the process. The impact is not confined to the hypogeum; it also causes destruction of the courtyard cliff. The dry season, which follows the torrential summer rainfall, further causes flaking and fracturing on the exterior part of the church. Facades that directly face sunlight are profoundly damaged. Moreover, the rock of the hypogeum is less resistant to weathering.

The impact of these threats is evident on all facades to varying degrees. The immediately unmasked features of the church to be exposed to deterioration are its aesthetic and architectural elements, including the refined motifs of the walls and frames of the windows. Most of these features, with some exceptions, are partly or completely lost on the eastern facade of the church. The most serious damage occurred on the western façade (see Figure ). Almost all architectural (aesthetic) features of the church are extremely eroded; their windows and beams rarely survive as ruins. The structural layer of the rock wall across this façade was seriously degraded, and its original plan was confused. The water that seeps into the internal part of the roof also causes cracking.

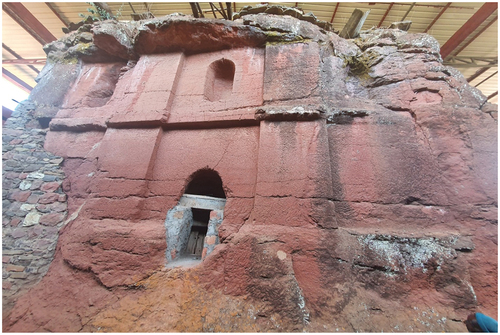

4.2.2. Local Conservation Practices and Challenges

Local people have made efforts to repair the damage that appears as a result of climatic factors. Repair work was conducted to save the church from complete destruction. The repairs aimed to fill the degraded facades of the church and to protect water from leaking into the roof of the church. The church roof is covered by stone paves (mainly black basaltic stones), which are concreted using modern cement (see Figure ). The materials used to fill the damaged wall sides were the same stones plastered with cement (see Figure ). The repairs were made by the initiation of local communities.

Figure 11. Unwise repairing that replaced the original feature, southern façade.

However, these repair works were not effective in sustaining the rock-hewn church. Recently, another initiative was initiated by the local communities. Two years ago, an iron sheet shelter was constructed to protect the rock hewn church from further damage caused by high rainfall and sunlight (Figure ). This initiation was the result of local voices regarding the profound deterioration of the ancient church. This construction project was initiated and led by the local communities. Regarding the construction of this shelter, an officer from the district’s Culture and Tourism Bureau stated the following:

The local communities were many times reporting to concerned stakeholders bout the conservation problem that Nazugn Mariam church was facing. However, it took long time to get some portion of the financial source from Amhara Regions’ Culture and Tourism Bureau for the construction of a shelter to the church. Most of the financial source of the construction was the local communities. The construction was made by a local construction contractor (Informant: Shiferaw Kefyalew).

Figure 14. The author with guests and local communities visiting the current conservation practice.

From the local communities’ perspective, the process of sheltering the church was challenging, mainly due to the absence of support from governmental offices. One of the servants of the church and members of a committee engaged in searching for funding narrated the issues as follows:

The believers and the priests of the church were warring about the conservation problem of this ancient church. We are responsible to transfer this heritage to our children. However, the church at its current situation is engendered due to sunlight and rainfall. We were reporting to federal culture office but we did not get a response for the request. We wander to collect the necessary resources for the construction of the shelter from believers in Addis Ababa by organizing a committee. We received some financial support from Amhara region. The transportation of construction materials such as steel and cement was difficult due to the absence of road after Debre Zebit. The local communities paid a lot in transporting the materials into the church (Informant: Destaw Tsegaye).

According to the contractor leading the process of shelter construction, the ongoing construction is aimed at protecting the church from further deterioration due to rainfall and sunlight. However, it has no role in maintaining the lost architectural values of the church, and it needs professional conservation practices to restore those values lost and deteriorated in the past (Informant: Deacon Meseret Asrese).

The conservation practices that are conducted at Nazugn Mariam are merely locally initiated and lack the support of potential stakeholders, such as governmental culture and tourism bureaus. The main challenge is the absence of professional support for local efforts to conserve endangered heritage sites in rural areas. The repair works are already uninformed reconstructions that are not advised by cultural heritage management protocols and professionals. The lack of support from the government in providing conservation professionals as well as conservation guidelines has led to haphazard methods being tried, causing structural problems and changing the aesthetic values of the church. This case is a good example of the lack of collaboration between local communities and stakeholders in the area of cultural heritage conservation in Ethiopia.

In general, uninformed interventions in Nazugn Mariam have caused various problems. First, new materials such as hard stone and concrete (cement) are used in the repair work. The insertion of these concreted stones caused further structural problems because the original rock of the church was softer than that of the new insertion. It also distorts the original aesthetic, architectural, and historical values of the church, which are inculcated in red rock. The church is unique in that it is rock-hewn, and the reconstructions have changed these values as stone and mortar have been added to the facades. Second, the repair work could not restore the lost architectural and structural elements. The process completely removed or obscured architectural and structural elements that were subjected to deterioration. The repairs were merely replacements made to fill the damaged parts of the rock wall (see Figures ). Due to a lack of professional support, impact assessment and restoration of lost values at all stages of the repair work were not performed. Intervention cluttered the present condition of the hypogeum.

Recent shelter construction is better than repairing works made on rock-hewn churches. It protects the church from further impacts from rainfall and sunlight. The construction process is made using cement, construction steals, and iron sheets, and an attempt is made to make the process contextual with the color characteristics of the rock from which the church is excavated. The shelter is stipulated to protect the rock church from rainfall and sunlight, but the previous damages remain critical, endangering the survival of the hypogeum, which calls for urgent expert-backed conservation activities. Moreover, the pillars erected to shoulder the shelter obscured the hypogeum, allowing easy observation of the facades of the church. Construction work was conducted to maintain and secure the courtyard of the church. However, the process is noted by keeping in mind the context of the rock from which the church is carved.

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

This paper has brought to light the major heritage values of Nazugn Mariam monolithic rock-hewn church, which are far from the insight of academicians, heritage management, and tourism development stakeholders, mainly due to a lack of information about its presence in such a remote area. Despite its values, the hypogeum is deteriorating due to the different factors described above. Local conservation practices are still ineffective in maintaining the lost architectural elements of churches. This hypogeum, therefore, is one of the endangered ancient rock-hewn churches tattling the absence of an effective cultural heritage management system in the country. Beyond describing its heritage values and conservation challenges, it is important to point out what should be done in relation to maintaining the values and using these values for tourism development, integrating other tourist sites that still have untapped resources. With regard to its conservation challenges, the local communities, as the nearest custodian and user for spiritual purposes, are exerting their efforts solely to rescue the endangered church. However, it requires the support of the government at the federal level to rescue it through collaborative conservation work. Because, though it is not little known, the church merits to be considered a national heritage given the values described in this study. As one of the main stakeholders in the management of cultural heritage, the government at all levels is responsible for conserving the history and culture of each community and sustaining the potential values for the tourism development plan, which requires promotion of the heritage values through the use of different means of communication. In such ways, not only the local communities but also the government can acquire economic benefit by enabling and integrating such untapped sites into the stream of the tourism industry at the national level. By taking these points into account, this study recommends the following issues, which are expected to respond to threatened cultural heritage that is not noticed due to its remote location:

First, given its multitude of values, recognizing the rock-hewn church of Nazugn Mariam as a national heritage has to be done by the Culture and Sport Ministry. In relation to this, holistic and inclusive heritage management practices are needed to identify significant cultural values in rural areas of the country at the national level. To this end, the regional and federal culture and tourism offices can collaborate to record and recognize such remote cultural sites. It should apply national heritage documentation mechanisms to enable the identification of national cultural heritage, which will help prioritize further conservation practices and developmental plans.

Second, the current shelter may contribute to protecting the hypogeum from further deterioration caused by rainfall and sunlight. However, the impact of previous unwise interventions continues to pose a potential threat to the hypogeum. To minimize this problem and restore the deteriorated parts of the church, professionally guided restoration work is needed.

Third, local conservation practices should receive support from experts working in cultural and tourism offices. More specifically, the federal-level office, which has better financial and manpower resources than bureaus at the regional level, is expected to respond to local voices demanding the conservation of public cultural values. Giving priorities to activities for the endangered church of Nazugn Mariam is needed. In order to protect such invaluable cultural heritage on the country side, capacitating local cultural heritage management offices has to be done. The federal government is also required to establish mechanisms to identify the most endangered cultural heritage for the employment of proper conservation practices.

Finally, archaeological work around the church may provide more evidence to better understand the historical aspects of the church. Gedle Abune Muse, which has different copies in different churches, is not considered by linguistic or philological scholars. Its translation into international languages and analysis of its text may contribute to a further understanding of the history of Abune Muse and his churches, including Nazugn Mariam.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tsegaye Ebabey Demissie

Tsegaye Ebabey Demissie is an Assistant Professor of Archaeology in the Department of Anthropology, Hawassa University. His areas of research interest are historical archaeology, cultural heritage management, and tourism development in Ethiopia. He has published different articles both in national and international peer-reviewed journals. He also has published books related to rock-hewn churches in Amharic, a widely spoken language in Ethiopia.

References

- Aklilu, T. (2013). A history of Mäqét Wäräda, 1941-1991. MA Thesis. Addis Ababa University.

- Allen, W. E. D. (1943). Ethiopian highlands. The Geographical Journal, 101(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/1790117

- Alvarez, F. (1881). Narrative of the Portuguese embassy to Abyssinia: During the years 1520-1527. (Lord Stanley, Trans.). The Hakluyt Society. Alderley

- Balicka-Witakowska, E. (2010). Waša Mikaʼel. In S. Uhlig (Ed.), Encyclopedia Aethiopica (Vol. 4, pp. 1150–1151). Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Bidder, I. (1959). Lalibela: The monolithic churches of Ethiopia. DuMont.

- Binns, J. (2017). The Orthodox church of Ethiopia. A history. I.B. Tauris.

- Blanc, G., & Bridonneau, M. (2016). Making heritage in Ethiopia/Faire le patrimoine en Éthiopie. Annales d’Ethiopie, 31, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.3406/ethio.2016.1621

- Bosc-Tiessé, C., Derat, M., Bruxelles, L., Fauvelle, F., Gleize, Y., & Mensan, R. (2014). The Lalibela rock hewn site and its landscape (Ethiopia): An archaeological analysis. Journal of African Archaeology, 12(2), 141–164. https://doi.org/10.3213/2191-5784-10261

- Buxton, D. (1947). The Christian antiquities of northern Ethiopia. Archaeologia, 92, 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261340900009863

- Chirikure, S. (2013). Heritage conservation in Africa: The good, the bad, and the challenges. South African Journal of Science, 9(1–2), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2013/a003

- Chirikure, S., Manyanga, M., Ndoro, W., & Pwiti, G. (2010). Unfulfilled promises? Heritage management and community participation at some of Africa’s cultural heritage sites. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16(1–2), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441739

- Crummey, D. (1975). Çäçäho and the politics of northern wällo and bägémder border. Journal of Ethiopian Studies, XIII(1), 1–9.

- Delmonaco, G., Margottini, C., & Spizzichino, D. (2010). Weathering processes, structural degradation and slope–structure stability of rock hewn churches of Lalibela (Ethiopia). In D. Calcaterra & M. Parise (Eds.), Weathering as a predisposing factor to slope movements (pp. 131–147). Geological Society of London.

- Ebabey, T. (2018). The rock-hewn church of Nazugn Maryam: An example of the endangered antiquities in North Wollo, Ethiopia. Journal of African Cultural Heritage Studies, 1(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.22599/jachs.34

- Ebabey, T. (2019). Threats to cultural monument in Ethiopia: Based on evidences of causes and problems of some forgotten rock-cut churches. Journal of Heritage Management, 4(1), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/2455929619866301

- Ebabey, T. (2020). Däbrä Aron: A rock-cut monastic church, mäqet District of northern Ethiopia. Warszawskie Studia Teologiczne, XXXIII(1), 230–254. https://doi.org/10.30439/WST.2020.1.11

- Federal Negarit Gazeta. (2000). Proclamation, no. 209/2000: A proclamation to provide for research and conservation of cultural heritage, 6th Year, no. 39. Addis Ababa.

- Feseha, M. (2012). The fundamentals of community based tourism in Ethiopia. Spanish Technical Cooperation.

- Fiaccadori, G. (2007). Muse. In S. Uhlig (Ed.), Encyclopedia Aethiopica (Vol. 3, pp. 1080–1081). Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Findlay, L. (1943). The monolithic churches of Lalibela in Ethiopia. La Société d’.

- Finneran, N. (2007). The Archaeology of Ethiopia. Routledge.

- Finneran, N. (2012). Hermits, saints, and snakes: The archaeology of the early Ethiopian monastery in wider. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 45(2), 247–271.

- Gebreegziabher, A., Getaneh, S., Aregu, Y., & McKay, S. (2019). Sustaining Ethiopian heritage sites: The case of gemate burial site in Dejen. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1603001

- Gemeda, B., Lahoz, R., Caldeira, A. T., & Schiavon, N. (2018). Efficacy of laser cleaning in the removal of biological patina on the volcanic scoria of the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela, Ethiopia. Environmental Earth Sciences, 7(36), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-017-7223-3

- Gerster, G. (Ed.). (1970). Churches in rock: Early Christian Art in Ethiopia. Phaidon Press Ltd.

- Gervers, M., Balicka-Witakowska, E., & Fritsch, E. (2014). Zoz Amba. In A. Bausi (Ed.), Encyclopedia Aethiopica (Vol. 5, pp. 198–200). Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Gobezie, M. (2012). Lalibela: A museum of living rocks. Master Printing Press.

- Gobezie, M. (2018). The Church of Yimrhane Kirstos: An Archaeological Investigation. Ph.D Dissertation, Lund University, Media Tryck.

- HableSellasie, S. (1972). Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270. United Printers.

- Heldman, M. E. (1992). Architectural symbolism, sacred geography and the Ethiopian church. Journal of Religion in Africa, 22(3), 222–241. https://doi.org/10.1163/157006692X00158

- Henze, P. (2000). Layers of time: A history of Ethiopia. Palgrave.

- Kassa, K. (2012). Impact of community-based tourism initiative on highland communities in the Meket Woreda, Ethiopia. MA thesis. Royal Roads University.

- Keitumetse, S. O. (2016). African cultural heritage conservation and management: Theory and practice from southern Africa. Springer.

- Mabulla, A. Z. P. (2000). Strategy for cultural heritage management (CHM) in Africa: A case study. African Archaeological Review, 17(4), 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006728309962

- Mason, R. (2002). Assessing values in conservation planning: Methodological issues and choices. In M. de la Torre (Ed.), Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage (pp. 5–30). The J. Paul Getty Trust.

- McPherron, S. P., Zeresenay, A., Curtis, W. M., Wynn, J. G., Read, D., Geraads, D., Bobe, R. & Béarat, H. A.(2010). Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia. Nature, 466(12), 857–860.

- Mercier, J., & Lepage, C. (2012). Lalibela wonder of Ethiopia: The monolithic churches and their treasures. Paul Halberton Publishing.

- Ndoro, W. (2016). World heritage sites in Africa: What are the benefits of nomination and inscription? In W. Logan, M. N. Craith, & U. Kockel (Eds.), A Companion to heritage studies (pp. 55–68). Willey Blackwell.

- Negash, T. (2006). The Zagwe period and the zenith of urban culture in Ethiopia, ca. 930-1270 A.D. Africa: Rivista trimestrale di studi e documentazione dell’Istituto italiano per l’Africae l’Oriente, 61(1), 120–137.

- Negussie, E. (2010). Conserving the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela as a world heritage site: A case for international support and local participation. In Elene Negussie (Ed.), Proceedings of the ICOMOS scientific symposium (pp. 76–81). ICOMOS.

- Nosnitsin, D. (2007). Minas. In S. Uhlig (Ed.), Encyclopedia Aethiopica (Vol. 4, pp. 971–972). Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Pankhurst, R. (1960). The monolithic churches of Lalibela: One of the wonders of the world. Ethiopia Observer, 4, 214–228.

- Phillipson, D. (2009). Ancient churches of Ethiopia: Fourth-fourteenth centuries. Yale University Press.

- Plant, R. (1995). Architecture of the tigre, Ethiopia. Ravens Educational and Development Service.

- Rewerski, J. (1995). Life below ground. In Troglodyties: A hidden world (pp. 9–14). UNESCO Courier. Available at. www.cranberry.ovh>217/06/pdf

- Schuster, H. M. (1994). Hidden sanctuaries of Ethiopia. Archaeology, 47(1), 28–35.

- Tamrat, T. (1972). Church and State in Ethiopia: 1270-1527. Oxford University Press.

- Weldegiorgis, E. T. (2018). Heritage Conservation Challenges on the Rock Churches of Tigray, Ethiopia. Ph.D. Dissertation. Hokkaido University.

- Weyer, R. V. (1973). The monastic community of Ethiopia. Ethiopia Observer, XVI(1), 8–14.

- Wright, S. (1957). Notes on some cave churches in the province of Wallo. Annales d’Ethiopie, II, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.3406/ethio.1957.1255

- Zeleke, K. (1975). Biography of the Ethiopic hagiographical equestrian saints in Ethiopia. Journal of Ethiopian Studies, XIII(2), 57–102.