?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

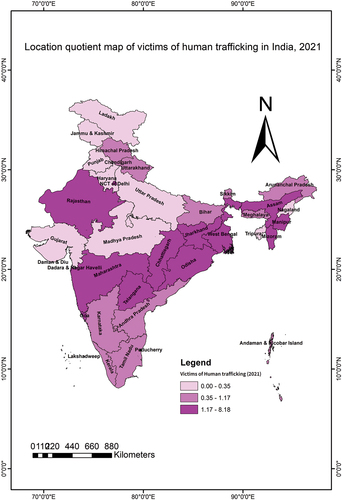

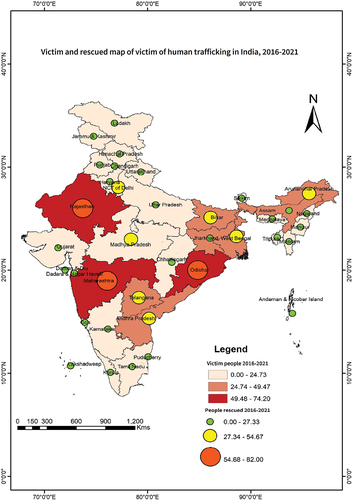

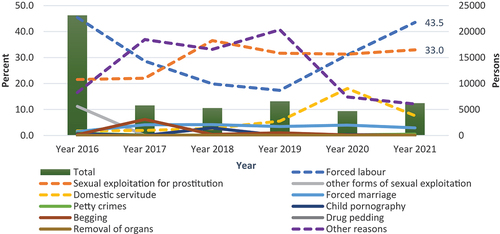

Human trafficking is one of the most rapidly increasing forms of transnational crime. Globally, an estimated 25 million adults and children are subjected to modern slavery or human trafficking. In India, approximately 7 thousand cases of human trafficking have been reported as of 2021 (ILO, 2022). The present study aims to contextualize the changing levels and patterns of human trafficking by integrating demographic and spatial dimensions by considering the dynamics of human trafficking with space, population, time, and circumstances in India. The study uses information from human trafficking cases reported by police records data accessed from Indiastat (www.Indiastat.com), an online repository supervised by the Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India. The present study deploys descriptive statistical techniques to accomplish the objectives, as the descriptive design provides a detailed and accurate data representation. Location quotient (LQ) mapping is used to detect the degree of victimization by human trafficking for 2021. The volume of human trafficking remained stagnant (above five thousand) until 2017, but it decreased in 2020 due to the COVID-19 lockdown restricting human mobility. Forced labor (43%) and sexual exploitation (33%) are the leading causes of trafficking in India. Rajasthan (80.8%) male victims and Maharashtra (94.0%) female victims reported the highest reported cases of human trafficking by gender. The highest concentration of human trafficking concerning its population is in Goa LQ value: 8.18). Child rights protection measures and robust anti-trafficking policies should be established as major policy measures for the Indian government.

1. Introduction

1.1. General context in broad terms

Human trafficking constitutes an illicit endeavour characterized by exploiting individuals as a commodity, resulting in adverse repercussions for both individuals and the broader societal and communal fabric. The United Nations human trafficking definition (Palermo Protocol, Citation2000) provides a vital tool for the identification of victims, whether men, women, or children, and for the detection of all forms of exploitation that constitute human trafficking. It also urges countries to criminalize human trafficking and develop anti-trafficking laws in line with the Palermo Protocol’s legal provisions (Naujoks, Citation2020; Sigmon, Citation2008). Traffickers control victims through various processes, such as physical or sexual assault, extortion, emotional blackmail, and destruction of official documents. However, the degree of exploitation varies by type of trafficking, location, and environment (Uddin & Igbokwe, Citation2020). Governments at the local and international levels have formulated numerous strategies and diverse remedial measures to prevent and mitigate the prevalence of human trafficking. However, the practice still persists, particularly in lower- and middle-income nations (Deane, Citation2010). Both physical and socio-economic factors, including vulnerability to climate change, induced displacement leading to homelessness, chronic poverty, patriarchal societal norms, gender inequality, and unemployment, contribute to individuals becoming ensnared in the web of human trafficking. According to a report on Global Estimates of Modern Slavery, Forced Labor, and Forced Marriage (ILO, Citation2022), nearly 25 million individuals worldwide are victims of human trafficking. Specifically, 20.1 million are forced labor victims, and 4.8 million are victims of sex trafficking.

Moreover, almost 6.3 million women across the globe are subjected to various forms of forced commercial sexual exploitation daily. Among them, 1.7 million are children, constituting a quarter of the total involved in commercial sexual exploitation. Nevertheless, it is crucial to note that the occurrence and scale of human trafficking vary significantly around the globe. A regional disparity in the incidence of human trafficking is evident, with the Indian subcontinent emerging as a prominent hotspot, accounting for 15.3 million cases, with India alone contributing 11.1 million victims (Joffres et al., Citation2008). Human trafficking represents one of the most rapidly increasing forms of transnational crimes and refers to the modern-day manifestation of enslavement (Wooditch et al., Citation2009). The time-series analysis shows that more Western and Central European nations had declining human trafficking trends (Junger-Tas et al., Citation2001).

Conversely, a more significant proportion of Eastern Europe and Central Asia nations have witnessed an increase in convictions in recent decades (Bhattarai, Citation2007; Fihel et al., Citation2006). Additionally, previous studies have indicated that the majority, approximately 1.5 million victims annually, originate from South Asia alone (Khan et al., Citation2022; Sharmin et al., Citation2017). To combat human trafficking, authorities at the national and international levels have established several frameworks to prevent human trafficking, protect victims, and bring traffickers to justice. Examples include the Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking (GIFT), the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) by the United Nations (Wooditch et al., Citation2009), and the Anti-Trafficking Directive Bill (ATDB) by the European Union (Jana et al., Citation2002). These measures included provisions for victim support and assistance and increased offender penalties.

1.2. The context in the Indian setting

Among LMICs, India introduced the Immoral Traffic Prevention Act (1956), which establishes penalties for violators and criminalizes all forms of human trafficking, including forced labor and trafficking for sexual exploitation (Bhatty, Citation2017). Over time, the Anti-human trafficking bill was amended several times in India. For instance, the Trafficking of Persons (Prevention, Protection, and Rehabilitation) Bill provides the legal framework for combatting human trafficking and offers victim protection (Kotiswaran & Rajam, Citation2023). The Nirbhaya Fund was established in 2013 to support initiatives to enhance women’s safety and security, including countertrafficking efforts. The horrifying gang rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi, which caused widespread anger and protests, led to the fund’s establishment. It strives to address the structural problems that underpin violence against women and offer assistance to survivors (Baruah & Nalbo, Citation2021). Despite several laws, regulations, and initiatives to protect human trafficking, it remains a burning issue in LMICs, particularly in India (UNODC, Citation2018). The literature mainly focuses on the nature, extent, and identification of human trafficking survivors in India (Fargnoli, Citation2017; Ryon et al., Citation2012). A nexus between geographical aspects and the nature of human trafficking was explored by a previous study conducted in Bangladesh (Cockbain et al., Citation2022). The hotspots of human trafficking are identified in areas characterized by porous international borders, coastal harbors, and geographically remote areas. Furthermore, several studies conducted in Asia and Africa have linked climate change and environmental variabilities with human trafficking crimes (Hidayati, Citation2020; Uddin & Igbokwe, Citation2020).

Geographical regions with a high propensity for floods, cyclones, and drought inclines livelihood vulnerability, which stems from out-migration. Furthermore, migrants at destinations face several challenges, including housing and social security, which are positively linked to the risk of human trafficking (Basit Naik, Citation2018). Apart from geographical aspects, several socio-cultural factors, including patriarchal societal practice, gender-based violence, persecution, and cross-regional marriage, have also been recognized by several studies to explain the mechanism of human trafficking from Indian perspectives (Balakrishnan, Citation2002). However, economic backwardness is the leading factor of human trafficking worldwide. Therefore, regions with chronic poverty are more vulnerable to human trafficking incidents (Bhalla & Hazell, Citation2003).

2. Rationale of the study

Although previous studies have explored the multidimensional mechanisms and dynamics of human trafficking and associated drivers, the complexity of the pathways of human trafficking has failed to draw a comprehensive conclusion about the reasons behind human trafficking (Balakrishnan, Citation2002). As a result, the level, patterns, and determinants of human trafficking change with space, population, time, and circumstances (Dingle & Drake, Citation2007). The present study aims to contextualize the changing levels and patterns of human trafficking by integrating demographic and spatial dimensions by considering the dynamics of human trafficking with space, population, time, and circumstances. The research will help us grasp the challenges of human trafficking in India by looking at factors such as time, age, sex, and location. It will also show how the COVID-19 pandemic affects the occurrence of human trafficking.

3. Method

3.1. Data source

The study uses secondary data from Indiastat (www.Indiastat.com), supervised by the Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India. The data provide gender dimensions of trafficking, broad age-groupwise victims of trafficking, the purpose of trafficking, and the number of anti-trafficking units. The data are purely based on the reporting of cases at the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) by the anti-trafficking units across the states of India. Data from 2016 to 2021 and three types of information, i.e., victim, rescue, and antitrafficking units, were considered for the current study.

3.2. Methodology

The present study applied descriptive statistical techniques to accomplish the objectives. The descriptive design focuses on providing a detailed and accurate representation of the data. It is helpful in generating hypotheses, exploring trends, and identifying patterns in the study. The percentage distribution presents the victim and purpose of trafficking by age-sex distribution of human trafficking in India. Location quotient mapping was carried out to detect the degree of victimization by human trafficking for 2021. Location quotient helps to quantify the concentration of a phenomenon or an event in a particular demographic group (population) within an area compared to the country. The application of the Location quotient in the current study aims at spatial mapping of human trafficking to detect the vulnerable states in India. Utilizing the location quotient is a powerful way to identify growth opportunities and perform comparative regional analysis.

3.3. Statistical analyses

Location quotient (LQ) formula:

Here,

hti: Victim of human trafficking in each state 2021,

ht: Total population in the state 2021,

HTi: Total victims of human trafficking in India 2021,

HT: Total population of India in 2021.

The location quotient value is determined in the current study using the formula above. The LQ calculation includes the total number of victims in a state, the state’s population, the overall number of victims of human trafficking throughout India, and the country’s population. In contrast, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) provides only statewise information on the number of human trafficking victims. As a result, the location quotient value aids in determining whichever Indian state has the highest or lowest concentration of victims of human trafficking relative to the state’s overall population. While the NCRB data simply offer a numerical value, they lack information regarding the proportion of victims to the overall population.

4. Results

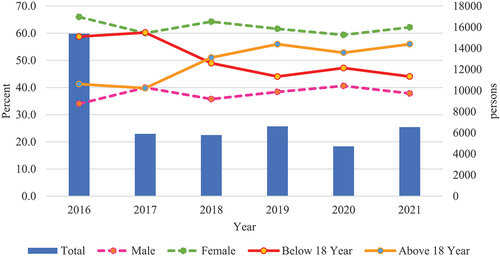

The volume of human trafficking has been found to fluctuate over time, but the number of victims remained stagnant (above five thousand) until 2017. Furthermore, the study showed that the volume of trafficking decreased in 2020 due to the COVID-19 lockdown restricting human mobility, negatively affecting the risk of trafficking in India. Moreover, the current study also finds a persistent gender gap in human trafficking, i.e., females are 30% more victims of trafficking than males (Figure ). There was a continuous increase in the number of trafficking victims from 2017 to 2018 and from 2018 to 2019. Although a slight drop was noticed in 2019–2020, the number further rose in 2020–2021. Surprisingly, the volume of human trafficking decreased during 2019–2020, which can be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown situations. Additionally, it has been discovered that people over 18 years have seen a rise in the number of trafficking victims in the past five years in India.

Figure 1. Trends of human trafficking victims in India (2016–2021).

Regarding the reason/purpose of trafficking, a study found that forced labor (43%) is the main purpose of human trafficking in India. This is followed by sexual exploitation (33%), domestic servitude, forced marriage, begging, removal of organs, child pornography, etc. Furthermore, Figure shows the rise of trafficking cases for other reasons for human trafficking. Moreover, it has also been found that the prevalence of domestic servitude in India has increased over time, reaching approximately 20 percent in 2020.

Figure 2. Volume (parsons) and purpose (percentage) of victims in India (2016–2021).

There has been a total of 6035 victims in Rajasthan (see Table ). A total of 80.8% of these victims are men, while 19.2% are women—the high proportion of male victims in Rajasthan points to a gender gap in the data on victimization. Regarding the total number of victims, 93.8% were adults, while 6.2% were children. Adult males were more vulnerable to trafficking in Rajasthan, Bihar, and Delhi. In contrast, in West Bengal, teenage girl victims outnumbered their teenage boy counterparts. In Maharashtra, there were 5021 victims in total in 2021. Here, most victims are female (94.0%), while a smaller proportion are male (6.0%). A relatively minor portion of the victims (11.7%) were below 18 years of age, and a substantial proportion (88.3%) were above 18. These statistics highlight the alarming percentage of females over 18 affected by trafficking. A quasi equal distribution of victims is male (54.5%) and female (45.5%). While a sizeable percentage of the victims (31.6%) are under 18, most (68.5%) are over 18.

Table 1. Top 10 states with age-sex distribution of human trafficking in India (2016–2021)

Rajasthan, with 6035 victims of trafficking (4821 higher than the national average of above 1214), comprises 13% of the nation’s total trafficking victim population (see Figure ). A total of 80.8% of the trafficking victim population in the state is male, while 19.2% is female. Furthermore, Goa has recorded the highest concentration of the victim population (LQ value: 8.18), followed by Delhi, Odisha, Mizoram, West Bengal, Rajasthan, Telangana, Manipur, Maharashtra, Jharkhand, and Assam with high concentration (LQ value 1.17–8.18). The states such as Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Sikkim, and Uttarakhand, however, show a relatively lower concentration (LQ value 0.35–1.17).

Figure shows that Odisha, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan had a higher percentage (49.5% to 74.2%) of trafficking victims. The states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Jharkhand, Bihar, West Bengal, Assam, and Arunachal Pradesh were moderate (24.74% to 49.5%). The remaining states of India show a lower percentage (≤24.7%) of human trafficking victims. Figure also depicts people rescued from human trafficking. Similarly, the number of victims of trafficking in Odisha, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan was also high (54.7% to 82.0) among rescued people. Furthermore, states such as Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, and Arunachal Pradesh have a medium percentage (27.34% to 54.67%) of rescued people. However, the remaining states of India stand with a lower percentage (27.3% and below) of rescued people.

5. Discussion

The present study found substantial temporal, spatial, and demographic variation in human trafficking in India. The temporal changes in human trafficking in India show that the volume of human trafficking drastically decreased after 2016 in India. After that, there was a discernible decline in the identification of trafficking victims, notably due to a decrease in the number of cases of bonded labor victims (Sarkar, Citation2014). Additionally, there has been a significant reduction in reported cases related to bonded labor, with 22 out of India’s 36 states and union territories failing to report any identified bonded labor victims or file cases under the Bonded Labor System Abolition Act (Kaur, Citation2023). However, it is essential to acknowledge that this decline in trafficking victim identification has exposed significant shortcomings in the provision of protection services for child trafficking victims; these inadequacies have persisted in India without sufficient attention from the government (Parks et al., Citation2019). The current findings demonstrate a significant decline in the volume of human trafficking during the 2020. Moreover, with the gradual removal of lockdown restrictions in 2021, there was a subsequent increase in the volume of human trafficking. These trends unequivocally underline the impact of human mobility and commercial constraints on the risk of human trafficking. The current study aligns with prior research (Mahato et al., Citation2020), showing reduced cases of trafficking victims during lockdowns due to comprehensive restrictions. It underscores the intricate interplay between societal mobility, economic activity, and the prevalence of human trafficking. In the current study, a striking and persistent gender disparity of over 20% in human trafficking has endured throughout 2016–2021, with females consistently trafficked more than their male counterparts.

The gender imbalance of human trafficking in India is attributed to the broader context of limited women’s rights and empowerment in the country (Waris & Viraktamath, Citation2013). The literature further substantiates this observation by highlighting a concerning practice: many parents arrange early-age marriages for their daughters to save dowry expenses (Paul, Citation2019). Tragically, a significant number of these cases eventually fall under the grim umbrella of human trafficking in India (Sarkar, Citation2016). While the purpose of forced marriage as a form of trafficking has decreased by less than 10 percent over the past five years, it persists in certain states such as Assam, Odisha, and West Bengal (Kakar & Yousaf, Citation2022). Notably, in states with low sex ratios, such as Haryana and Punjab, girls are still trafficked to become cross-region brides (Deb et al., Citation2005; Gibbs et al., Citation2015; ILO, Citation2017). This practice involves the trafficking of women from distant and economically disadvantaged states such as Assam, the Sundarban region of West Bengal, Jharkhand, Bihar, and Odisha to address the scarcity of brides in the villages and cities of Haryana and Punjab (Kukreja, Citation2018). Despite the overall decline in this form of trafficking, the persistence of such practices highlights the ongoing challenges and vulnerabilities women face in regions with imbalanced sex ratios (South & Trent, Citation2010). The result underscores the urgent need to address deep-rooted societal issues, promote gender equality, and empower women to combat this persistent and troubling gender-based disparity in human trafficking.

Current research identifies Rajasthan as having the highest incidence of human trafficking, followed by West Bengal and Maharashtra. However, it is essential to note that when the volume of trafficking is high in a state, the demographic profile of victims also varies significantly (Soley, Citation2014). Rajasthan sees a higher prevalence of male-child trafficking, whereas West Bengal and Maharashtra are more susceptible to girl-child trafficking. This difference underscores the spatial variability in the context of human trafficking. Previous studies have attributed the high prevalence of male-child trafficking in Rajasthan to a long-standing practice of forced and bonded labor migration. In contrast, in West Bengal, Maharashtra, and Goa, the prominence of girl-child trafficking is primarily linked to sexual exploitation and involvement in illegal commercial sexual activities (Surtees, Citation2008). Notably, Mumbai in Maharashtra and Kolkata in West Bengal have emerged as hotspots for the transit routes of female trafficking, connecting the route from national to international human trafficking networks (Deb et al., Citation2005; Ghosh, Citation2014). Current research also shows that in Odisha, Bihar, and Delhi, young males are more vulnerable to human trafficking.

Vulnerability stems from the complex interplay between unemployment, poverty, labor migration, and human trafficking (Paul, Citation2019). The current study also highlights that the northern, southern, northeastern, and western states exhibit the lowest numbers of rescued individuals in India. The frequency of rescues primarily depends on the number of people trafficked in a given region and effective anti-trafficking units in that area (D’Souza & Marti, Citation2022). The lack of antitrafficking units in many states, including Kerala, Arunachal Pradesh, and Haryana (with no antitrafficking units), underscores significant infrastructural deficiencies in combating human trafficking (Dixit, Citation2017; Nair IPS, Citation2002). Addressing these structural gaps is vital in strengthening the fight against human trafficking in India. The study findings also shed light on the intricate regional variations in the dynamics of human trafficking in India, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions and policies tailored to the specific challenges faced in each state.

6. Limitations and strengths of the study

The study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, this study provides valuable insights into the patterns of human trafficking in India; however, it does not delve into the underlying “why” and “how” aspects of this complex issue. A qualitative study is warranted to understand an in-depth overview of human trafficking in India by interviewing victims and representatives from government and nongovernmental organizations actively combating human trafficking in India. Second, the study relies on reported cases of trafficking, which inherently presents a limitation, as many instances of human trafficking go unreported, resulting in an underestimation of the actual volume of such cases in India. Third, this study is descriptive and does not establish causality between human trafficking and explanatory factors. It is important to note that this limitation restricts studies’ ability to identify causal relationships.

Despite these limitations, the present study offers valuable insights into the spatial and temporal variations in human trafficking in India. These knowledge serves as a foundation for future research, enabling the exploration of area-specific human trafficking issues and challenges within India, building upon the current study’s findings.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, the current comprehensive study on human trafficking in India has illuminated five pivotal dimensions that warrant attention and action. First, it elucidates the nuanced fluctuations in the volume of human trafficking over time, despite several policy initiatives. Moreover, a persisting gender imbalance in human trafficking emerges, with females constituting 30% more victims than males. The exceptional reduction in trafficking during the tumultuous year of 2020, attributed to COVID-19 lockdown measures, underscores the influence of restricted human mobility on diminishing the risk of trafficking. Second, the study pinpoints forced labor (43%) and sexual exploitation (33%) as the primary drivers of trafficking. Third, an examination of age groups spotlights states such as Rajasthan, West Bengal, Delhi, Bihar, and Jharkhand as having the highest number of trafficking victims below the age of 18. Emphasizing the urgent need to fortify child rights protection measures in these regions. Fourth, Goa has recorded the highest concentration of the victim population (LQ value: 8.18), followed by Delhi, Odisha, Mizoram, and West Bengal. Finally, states such as Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Odisha lead in rescuing trafficking victims. Signaling the importance of robust policies focused on rehabilitation, employment opportunities, and mainstreaming programmes. Incorporating these findings into policy and practice is paramount to effectively combatting human trafficking in India and safeguarding the rights and well-being of its vulnerable populations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Balakrishnan, R. (2002). The hidden assembly line: Gender dynamics of subcontracted work in a global economy (pp. 1–11). Kumarian Press.

- Baruah, N., & Nalbo, M. (2021). Optimizing screening and support Services for gender-based violence and trafficking in Persons victims (pp. 1–5). The Asia Foundation

- Basit Naik, A. (2018). Impacts, causes and consequences of women trafficking in India from human rights perspective. Social Sciences, 7(2), 1–76. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ss.20180702.14

- Bhalla, G. S., & Hazell, P. (2003). Rural employment and poverty: Strategies to eliminate rural poverty within a generation. Economic & Political Weekly, 38(33), 3473–3484. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4413911

- Bhattarai, R. (2007). International migration, multilocal livelihoods, and human security: Perspectives from Europe, Asia and Africa panel 5 International migration, citizenship, identities, and cultures. Open borders, closed citizenships: Nepali labor migrants in Delhi.

- Bhatty, K. (2017). A Review of the Immoral Traffic Prevention Act. Policy brief, centre for policy research.

- Cockbain, E., Bowers, K., & Hutt, O. (2022). Examining the geographies of human trafficking: Methodological challenges in mapping trafficking’s complexities and connectivity. Applied Geography, 139, 139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2022.102643

- Deane, T. (2010). Cross-border trafficking in Nepal and India-violating women’s rights. Human Rights Review, 11(4), 491–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12142-010-0162-y

- Deb, S., Srivastava, N., Chatterjee, P., & Chakraborty, T. (2005). Processes of child trafficking in West Bengal: A qualitative study. Social Change, 35(2), 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/004908570503500208

- Dingle, H., & Drake, A. (2007). What is migration? BioScience, 57(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1641/B570206

- Dixit, M. (2017). Cross-border trafficking of Bangladeshi girls. Economic and Political Weekly, 52(51), 26–30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26698370

- D’Souza, R. C., & Marti, I. (2022). Organizations as spaces for caring: A case of an anti-trafficking Organization in India. Journal of Business Ethics, 177(4), 829–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05102-4

- Fargnoli, A. (2017). Maintaining stability in the face of adversity: Self-care practices of human trafficking survivor-trainers in India. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 39(2), 226–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-017-9262-4

- Fihel, A., Kaczmarczyk, P., & Okólski, M. (2006). Labor mobility in the enlarged European Union International migration from the EU8 countries. CMR Working Papers, No. 14/72, www.migracje.uw.edu.pl

- Ghosh, B. (2014). Vulnerability, forced migration and trafficking in children and women: A field view from the plantation industry in West Bengal. Economic and Political Weekly, 49(26), 58–65.

- Gibbs, D. A., Hardison Walters, J. L., Lutnick, A., Miller, S., & Kluckman, M. (2015). Services to domestic minor victims of sex trafficking: Opportunities for engagement and support. Children and Youth Services Review, 54, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.04.003

- Hidayati, I. (2020). Migration and rural development: The impact of remittance. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 561(1), 012018. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/561/1/012018

- ILO. (2017) . Global estimates of modern slavery forced labor and forced marriage. International Labor Organization.

- ILO, I. L. O. (2022). Global estimates of modern slavery forced labor and forced marriage. International Labor Organization.

- Jana, S., Bandyopadhyay, N., Dutta, M. K., & Saha, A. (2002). A tale of two cities: Shifting the paradigm of anti-trafficking programmes. Gender & Development, 10(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070215887

- Joffres, C., Mills, E., Joffres, M., Khanna, T., Walia, H., & Grund, D. (2008). Sexual slavery without borders: Trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation in India. International Journal for Equity in Health, 7(1). 1–11 https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-7-22

- Junger-Tas, J., Boutellier, J. C. J., Board, A., Albrecht, H.-J., Bartsch, H.-J., Bottoms, A. E., Van, J. J. M., Kerner, H.-J., Levi, M., Wikstrm, P.-O., Assistant, E., & Baars, A. H. (2001). Ethnic diversification and Crime. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 9(1), 1–2. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12832/298

- Kakar, M. M., & Yousaf, F. N. (2022). Gender, political and economic instability, and trafficking into forced marriage. Women and Criminal Justice, 32(3), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2021.1926403

- Kaur, B. (2023). Rehabilitation of bonded laborers in India: An analysis. Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 3(1), 1–8.

- Khan, Z., Kamaluddin, M. R., Meyappan, S., Manap, J., & Rajamanickam, R. (2022). Prevalence causes and impacts of human trafficking in Asian countries: A scoping review. F1000research, 11, 1021. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.124460.2

- Kotiswaran, P., & Rajam, S. (2023). When hyper criminalization falls afoul of the constitution: The need to rethink the trafficking in Persons (Prevention, care and Rehabilitation) Bill 2021. Indian Law Review, 7(3), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/24730580.2023.2235937

- Kukreja, R. (2018). Caste and cross-region marriages in Haryana, India: Experience of dalit cross-region brides in Jat households. Modern Asian Studies, 52(2), 492–531. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X16000391

- Mahato, S., Pal, S., & Ghosh, K. G. (2020). Effect of lockdown amid COVID-19 pandemic on the megacity Delhi, India air quality. Science of the Total Environment, 730, 730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139086

- Nair IPS, P. (2002). A report on trafficking in women and children in India. Action Research on Trafficking in Women and Children.

- Naujoks, D. (2020). Multilateralism for mobility: Interagency cooperation in a post pandemic world. In COVID-19 and migration: Understanding the pandemic and human mobility (pp. 183–193). Transnational Press London. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345816129

- Palermo Protocol. (2000). Protocol on trafficking. General Assembly resolution, 55/25 of 15.

- Parks, A. C., Zhang, S., Vincent, K., & Rusk, A. G. (2019). The prevalence of bonded labor in three districts of Karnataka state, India: Using a unique application of mark-recapture for estimation. Journal of Human Trafficking, 5(3), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2018.1471576

- Paul, P. (2019). Effects of education and poverty on the prevalence of girl child marriage in India: A district–-level analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 100, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.02.033

- Ryon, S. B. P., Keith, E., & Brown, M. P. A. (2012). Trafficking in Persons Symposium Final Report. (April 10-13, 2012, SALT LAKE CITY, UT) (pp. 1–100). Annotation.

- Sarkar, S. (2016). Child marriage trafficking in India: Victims of sexual and gender-based violence. Anthropology Now, 8(3), 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/19428200.2016.1242911

- Sharmin, S., Mohammad, A., & Rahman, A. (2017). Challenges in combating trafficking of human beings in South Asia. Journal of the Indian Law Institute, 59(3), 264–287. https://doi.org/10.2307/26826607

- Sigmon, J. N. (2008). Combating modern-day slavery: Issues in identifying and assisting victims of human trafficking worldwide. Victims and Offenders, 3(2–3), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564880801938508

- Soley, A. (2014). Give and take: The struggle of being a part of the System you want to change. In Childline: Solving and perpetuating child vulnerability in Bikaner. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection.

- South, S. J., & Trent, K. (2010). Imbalanced sex ratios, men’s sexual behavior, and risk of sexually transmitted infection in China. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(4), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510386789

- Surtees, R. (2008). Trafficked Men as Unwilling Victims. Review, 4(1), 16–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/26225803

- Uddin, I. O., & Igbokwe, E. M. (2020). Effects of international migration and remittances on edo state, Nigeria rural households. Human Geographies, 14(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.5719/hgeo.2020.141.6

- UNODC. (2018). Global report on trafficking in persons: In the context of armed conflict, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

- Waris, A., & Viraktamath, B. C. (2013). Gender gaps and women’s empowerment in India-issues and strategies. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 3(9). www.ijsrp.org

- Wooditch, A. C., DuPont-Morales, M. A., & Hummer, D. (2009). Traffick jam: A policy review of the United States’ trafficking victims protection Act of 2000. Trends in Organized Crime, 12(3–4), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-009-9069-x