Abstract

Several interethnic violent conflicts have escalated in Ethiopia over the last few years. Particularly in the southern regional state of Ethiopia, the conflict between the Konso and Ale ethnic groups has its roots in intercommunal crises. This study examines the role of customary institutions (CIs) in the transformation of violent conflict between the Konso and Ale ethnic groups in southern Ethiopia. The study employed a case-study research design with a qualitative approach. The data are organised and analysed thematically. The 1991 federalism and the autonomy of ethnic groups led to conflicts between the two communities. The study reveals that prior to the 1991 Ethiopian regime, the Konso and Ale ethnic groups had robust CIs used to transform conflicts ranging from personal to criminal issues. However, currently, CIs have not been able to end the ongoing conflict due to sociopolitical factors like the complex nature of conflict, erosion of traditional values due to modernization, government interventions, youth and religious misunderstandings of CIs, and the limited authority of customary systems. The new state structure and formal institutions that have replaced traditional ones with politically motivated institutions have also reduced the significance of the system.

IMPACT STATEMENT

In 1991, Ethiopia established an ethnic federal structure to prevent future violent interethnic conflicts however, this redefining of the country along ethnic lines has become the source of conflicts, causing great harm to the citizens in general and the Konso-Ale ethnic groups in particular. CIs have lost their previous authority and become weaker and unable to effectively transform such conflicts across the country, and this is true for the Konso and Ale cases. This article aims to examine the role of CIs in transforming the violent conflict between the Konso and Ale ethnic groups in southern Ethiopia. The low status of customary institutions is attributed to factors such as the establishment of a new state structure, erosion of traditional values, modern practices, youth and religious misunderstandings of CIs, and limited authority of CIs. The government and all stakeholders should work together to strengthen CIs and address ethnic conflicts.

1. Introduction

Conflict is a global phenomenon that can occur within states, ethnic groups, clans, villages, families, and other small units (Appiah-Thompson, Citation2020). Around one-third of the world’s countries face persistent violent conflicts based on resource, political, and ethnic lines (Mboh, Citation2021; Kariuki, Citation2015). Ethnic conflicts best serve multi-ethnic Africa. Though the general political and economic crisis exacerbates African conflicts, ethnicity plays a significant role in these conflicts. The mid-1960s were a significant period of long-term ethnic violence in Africa, resulting in multiple acts of violence (Kassa, Citation2020).

Ethiopia’s history indicates that it is generally a conflict-ridden country (Siyum, Citation2021). Authoritarianism and the unequal distribution of power and natural resources are the primary causes of conflicts in Ethiopia. Discrimination and oppression have also led to the formation of organised rebellions, which have further aggravated inter-ethnic tensions across the country (Gezu, Citation2018). The overthrow of Dergue in 1991 was the turning point for ethnic uprisings and regional autonomy movements, with diverse ethnic groups working towards institutional repair and power sharing. The 1995 constitution emphasised ethnicity as a fundamental principle for state organisation, representation, and political mobilisation, aiming to resolve disputes and promote national reconciliation. However, disputes over borders and ethnic clashes still exist. Against the expectations of many analysts of Ethiopian political landscapes, inter-ethnic conflicts were exacerbated, particularly after the 2018 change and anticipated stabilisation and democratisation, which, of course, won the Nobel Peace Prize for the Prime Minister in 2019. At odds with the expectations of many, security problems have intensified into civil wars and inter-ethnic clashes, and consequently, the country has experienced the highest rate of internal displacements in the world (Yusuf, Citation2019; Siyum, Citation2021).

Self-government and the current political system, which separates people who formerly lived in the same administrative region, are the main factors contributing to ethnic conflicts. Moreover, inequitable power sharing, undefined boundaries, small arms, fear of insecurity, and dominance by a certain group also contribute to these conflicts (Siyum, Citation2021; Helen, Citation2018). For instance, in the previous few decades, confrontations have taken place in different parts of the country, near the borders of Oromia and Somalia, Afar and Issa, Garre and Borana, Oromia and Gumuz, Guji and Gedeo, Anuak and Nuer, Sidama and Guji, Kereyu and Afar, Qimant-Amahara, and Wolayita-Sidama (Wondimu, Citation2013; Siyum, Citation2021).

Among the several conflicts in Ethiopia, the ongoing and violent conflict between the Konso and Ale communities in the southern part of the country is perhaps the most concerning issue. Before 1991, Ale ethnic groups were governed by the Konso and Derashe administrative authorities. Accordingly, they have consistently collaborated on accessing and utilising available resources together. However, since 1991, the new administrative structure has led the Ale ethnic group to seek self-administration rights based on their ethnic identities (Demissew, Citation2016). This has resulted in hostilities with the neighbouring ethnic communities, mainly with the Konso ethnic groups. Conflict in the study area has also increased in scale and cost, creating insecurity and tension between them. The increasing number of populations with scarce resources and small arms also perpetuates the conflict between them.

The Joint Multi-Agency Emergency Need Assessment (JMAENA) (Citation2020) revealed that the Konso-Ale conflict resulted in over 66,711 people being displaced from 7 kebeles of the Konso zone and dispersed within host communities. Moreover, the same conflict resulted in the displacement of 22,167 people from Ale Woreda, of whom 15,027 were displaced from the adjacent kebeles of the Konso zone due to fear and insecurity. At the same time, 7140 people from six kebeles of Ale were displaced and settled in other nearby kebeles. Therefore, regarding contemporary large-scale violent conflicts, the study needs to examine the roles of CIs in transforming conflicts in the area.

The study primarily focused on conflict transformation through customary institutions while also considering conflict resolution. According to Lederach and Maiese (Citation2009), conflict transformation and resolution are often interconnected, with transformation serving as a foundation for resolving post-violent conflicts. In terms of reaching a long-lasting and mutually acceptable solution among the conflicting parties, the current study of peace and conflict emphasises conflict transformation over conflict resolution (Psaltis et al., Citation2017). Conflict transformation involves addressing the root causes, historical patterns, and social conflicts, understanding their dynamics, and generating positive change processes beyond resolution. The study primarily examines the role of customary institutions in conflict transformation, based on the provided justifications.

Customary institutions (CIs) have been significant in being used by societies and have also played a vital role in preventing and transforming conflicts. African societies in particular have deeply rooted cultural institutions that played an essential role before and during colonial administration (Mengesha, Citation2016; Ali & Bukar, Citation2019). African CIs, such as the Gacaca courts in Rwanda, the Karamajong and Teso courts in Uganda, the traditional Akan courts in Ghana, the Kpelle people in Liberia, and the Yoruba and Igbo traditional institutions in Nigeria, are well-organized institutions that effectively resolve disputes (Akinola & Uzodike, Citation2018). However, Zuure (Citation2020) argues that African norms and practices are often misunderstood as irrational and incompatible with current standards for socioeconomic development and governance challenges. The study carried out in South Africa revealed that traditional leaders have not been treated with the respect they merit during peace talks and are not included in the formal decision-making process in conflict resolution (Mboh, Citation2021, p. 39–40).

In Ethiopia, after 1991, the multi-national federation implemented ethnically-based constituent units to reduce armed conflicts and prevent future violent interethnic conflicts through state-ethnic restructuring and devolution of power. This redefining of the country along ethnic lines has become the very source of conflicts, particularly over the delineation of the boundaries of the diverse federal units. There are currently no definite indications that the federal and regional governments will be successful in resolving these conflict dynamics permanently. The ethnically diverse southern part exhibits this tendency just as much as the other parts of the country (Kinfemichael, Citation2014). In this sense, the shift in interethnic relations (from formerly stable to conflictual) between the Konso and the Ale ethnic groups is not unusual. Since the country’s federalization, border tensions between these two groups in the south first emerged in the 1990s, similar to other ethnic groupings across the country.

Based on the aforementioned reasons, solely depending on legal measures cannot be considered an adequate response to the changing nature of inter-ethnic conflicts. Traditionally, the Ale and Konso ethnic groups have their own customary conflict resolution mechanisms called Atta in Ale and Moora in Konso. In 1991, a new political system that appreciates and promotes the multi-culturalism and self-governance of Ethiopian (cultural and linguistic-based) nations and nationalities was established. Some Ethiopian cultural and linguistic groups and many scholars argued that it was in the Ethiopian political system before 1991 that customary systems had great authority and substantial influence. Nevertheless, the new system diminishes the power and authority of CIs, and this is true for the customary systems of Konso and Ale, which are currently less or no longer autonomous. The clan and traditional leaders who had a measure of control over their public began to lose it. Hence, many researchers argue that it is important to emphasise the trend of eroding customary institutional power in the period after 1991 (Enyew, Citation2014; Ghebretekle & Rammala, Citation2018). The Konso and Ale ethnic groups’ customary systems are comparable to other cultural practices across various regions of the country. However, the area is understudied despite the ongoing violent conflict. Therefore, the overall objective of this study is to examine the role of CIs in conflict transformation between the Konso and Ale ethnic groups. The study also particularly attempts to critically study the challenges these institutions have been facing in recent times.

2. Methodology

2.1. The study areas

The Konso and Ale communities are selected for this study not because Ethiopia’s violent inter-ethnic conflict is limited only to them or their areas but for three big reasons. Firstly, these two communities had a peaceful relationship until 1991, the moment they began to ‘enjoy cultural freedom’,’self-governance’, and revitalization and strengthening of their systematically ‘weakened’ cultures, one of which was their age-old, influential CIs. Indeed, it was logical to think or expect otherwise, ie stronger CIs and more peaceful relationships. Secondly, the CIs of these two communities are very similar, and one might have logically expected easy and sustainable transformation conflicts. The third important feature of these communities is that both are minorities, and they used to feel they were both victims of other majorities or common repressive systems of the pre-1990s. Thus, the Konso-Ale conflicts are the subject of interest for researchers seeking a comparative understanding of fundamental causal factors and meanings of inter-ethnic conflicts in theIr specific, historical, and contemporary context.

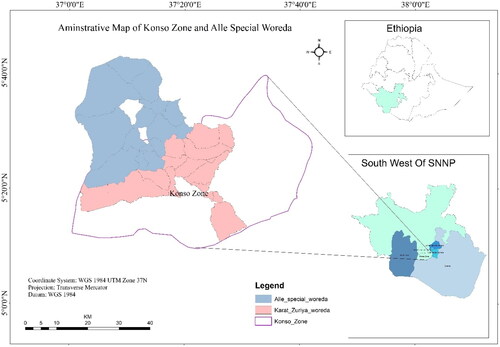

Geographically, the scope of the study focuses on the Konso Zone and Ale special district/Wereda, which share common political boundaries in the southern region. The Konso and Ale ethnic groups are the two distinct ethnic groups living in the adjacent areas called the Konso Zone and the Ale Special Wereda/District. The two ethnic groups have coexisted for centuries, and the areas are named after the ethnic groups that inhabit them. Both ethnic groups have a Kushtic background. The Konso are located about 600 km south of Addis Ababa and live in and around a small mountain range (Gelebo, Citation2016). The Ale Special Woreda is located 650 kilometres southwest of Addis Ababa and 422 kilometres southwest of Hawassa city. The Ale people share cultural and geographic connections with the Konso people. These villages rely on pastoralism and agro-pastoralism for subsistence. They maintain a variety of animals and crops ().

2.2. Research design

As was discussed above, the unique features of the Konso-Ale communities’ conflicts and the common cultural, historical, and political features of these communities call for a case study. A case study is one type of qualitative research design used to examine one or more situations in a limited environment (Mohajan, Citation2018). In other words, case study design allows the researchers to conduct longer and more frequent non-participant observation and dialogue and an in-depth understanding of the conflict in its historical-social context, adopting a qualitative approach. Therefore, for the appropriate attainment of the study objectives, the qualitative method was employed.

2.3. Sample size and sampling technique

A total of 38 participants were purposefully selected from Ale Special Wereda and Konso Zone. Moreover, a total of four more conflict-prone kebeles were selected: two kebeles (ie Gewada and Kerkerte) from Ale Special Wereda, and Galebo and Arfayide from Konso Zone. Eight key informants were selected to participate in the interviews. Four of them were from Konso, and the remaining four were from Ale. The key informants were chosen from four categories, namely clan leaders, community leaders, religious leaders, and local government officials. They possessed unique knowledge of the subject matter being investigated. Additionally, 14 individuals (7 from each site) who had unique knowledge of the topic were selected for in-depth interviews with community members. For qualitative research, selecting a sample requires understanding the central ideas of the phenomenon (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017). Two focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in Gewada Kebele of Ale District and Arfayide Kebele of Konso Zone with various community members. A total of sixteen individuals participated in the discussions, including kebele administrators, women, youth, and community elders. They provided crucial data related to the topic being discussed. To ensure confidentiality, the respondents’ identities were anonymized by assigning alphanumeric code numbers to each (for instance, KKI-2 designates a Konso Key Informant number 2; KII-2 labels a Konso In-depth Interview; II-2 Ale designates an In-depth Interview made with an Ale respondent number 2; and AKI-2 designates an Ale Key Informant number 2).

2.4. Data collection

Field data was collected during consecutive fieldwork conducted in February 2022, March 2022, April 2022, and November 2022. The data was generated through in-depth interviews, key informant interviews, and focus group discussions (FGDs). Each FGD, in-depth interview, and key informant interview were fully recorded for later transcription and analysis. To address research questions, both semi-structured and unstructured interviews were employed. Moreover, the diverse participants who represented the community to be studied were purposefully selected for the key informants and FGDs.

2.5. Data analysis

To address the study objectives, qualitative techniques of data analysis, namely thematic analysis, content analysis, and review of empirical studies, were used. Thematic and content analysis techniques were applied simultaneously to the in-depth interview transcriptions, key informant interview transcriptions, and FGD transcriptions. Moreover, the content analysis technique was used to analyze the qualitative data that was obtained from the document review, such as the 1995 EFDR Constitution. Content analysis involves finding concepts and patterns in the data, while thematic analysis involves close examination of the data to identify common themes—topics, ideas, and patterns—of meaning that come up repeatedly (Given Citation2008). Throughout the analysis process, inductive reasoning was adopted (Given, Citation2008). Inductive reasoning was crucial in identifying patterns and regularities in the Konso-Ale conflict, formulating some tentative hypotheses for further exploration, and developing some explanations and interpretations about the holistic picture of the conflicts and the role of their CIs in transforming the recurrent conflicts between them. An overview of empirical studies from sources that have been published was also analysed.

2.6. Ethical consideration

In both data collection and analysis, ethical issues were considered. In the first place, participants were provided with clear information about the study’s objective. They were given the choice to voluntarily participate or decline. To respect participants’ privacy and confidentiality, informants were described anonymously in the write-up and analysis of the study. Informants took part in the study without having their identities disclosed. Since they requested anonymity due to sensitive topics, their names were withheld for security concerns.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The role of the Konso-Ale customary institutions

The study aims to examine the role of CIs in the Konso and Ale communities. Based on the collected data, it can be concluded that the customary systems of the Ale and Konso, including clans and traditional leaders, are responsible for transforming conflicts between their communities. These systems also played a crucial role in promoting socio-economic development within the local community and ensuring justice is administered fairly. In-depth interviews (II) revealed that the Konso and Ale customary systems have a greater capacity to transform conflicts, maintain order, and restore social harmony than the modern legal systems (II-1, Konso, 2022). Labović (Citation2014) asserts that CIs foster economic, social, and political growth, safeguard human rights through informal networks, and promote justice and community relationships. However, because of the region’s ongoing conflicts, the ability of CIs is becoming weak, and the reality of today is not as it was previously described.

The Ale and Konso communities have their customary methods called Atta and Moora, which means the rule. Informants from both ethnic groups stated that a supernaturally endowed tribal chief—Bogolha for Ale and Poqohalla for Konso—had substantial authority over their members. Local communities exercised strong CIs prior to 1991, but modernization, religion, government meddling, and youth culture caused them to lose influence and become weaker (II-2, Konso; II-2, Ale). In support of this, Assefa (Citation2012) stated that earlier traditional leaders in Ethiopia had sovereign powers within their jurisdictions. Historically, the CIs in the Konso and Ale ethnic groups have played a significant socio-economic role in the community. Most respondents stated that the replacement of CIs by politically oriented institutions followed by ethnic federalism has significantly weakened the role of the customary system. Besides religion and modern education, the impartiality of traditional figures affects the process of conflict transformation (II-2, Konso; II-2, Ale). Although the Konso and Ale customary institutions have made significant contributions to promoting interethnic relations and peaceful coexistence, the system is currently fragile and unable to effectively address ethnic conflicts. The CIs of Konso and Ale have played important roles in providing social and security protection to their communities throughout history. The study will provide a detailed explanation of the roles and functions of these institutions in achieving their respective goals.

3.1.1. Social and security role of customary institutions

The question of how the two societies in focus foster their collective security issues is worth examining. This is because the general notion is that transforming conflicts through customary means contributes significantly to the well-being of the community. After all, by addressing conflicts through traditional means, people do not face security issues. Informants in Ale revealed that customary systems can work to transform conflicts and maintain order and peace to restore social harmony and relationships more than modern judicial systems (II-7, Ale). In support of the above idea, Achieng (Citation2015) revealed that despite limited documentation on peace initiatives, traditional institutions in Africa have played an important role, from the crisis in Angola to the post-genocide reconciliation process in Rwanda and Liberia. One of the leaders of the Konso clan reported that:

In the process of reconciliation, we focus not only on addressing the problem but also on how to bring conflicting people back to their previous relationships and how to maintain adequate compensation for those who were injured in the conflict. But at the moment, a number of reasons mean that the standard system isn’t functioning as it once did (KKI-3, Konso).

3.2. The process of conflict transformation through ritual practices

One of the fundamental questions concerning this study is how the two societies transform or attempt to transform their conflicts. The customary institutions of the Konso and Ale ethnic groups facilitated social and cultural interactions between local communities. To prevent damage and loss of human life and property, ceremonial processes are believed to be involved in restoring peace after violent conflict through traditional actors (clan leaders and traditional elders).

It is essential to understand and use customary strategies that both ethnic groups can accept and respect. Both Konso and Ale informants have experienced spiritual practice, and there are considerable similarities between them, particularly in their efforts to transform conflict and promote peace. In traditional spiritual practices, the oath is administered through various stages and settings to achieve the goal of conflict transformation. The process involves various actors, such as witnesses, accusations without evidence, both sides of the dispute, elders, and all suspected members (II-3, Konso; II-3, Ale). According to Pankhurst and Assefa (Citation2016) and Epple and Assefa (Citation2020), there are many kinds of ceremonies and spiritual practices of swearing and cursing practiced in different geographical settings of the country. For example, the expressions of the kakuu of the Oromo, the kuaar Muon of the Nuer, the moticha and gudumaalee of Sidama, and the chako of the Wolayita people are an oath and one of the spiritual elements of the customary systems carried out during the reconciliation process.

Traditional elders and clan leaders play a significant role in performing ritual ceremonies. Ali and Bukar (Citation2019) state that taking an oath and swearing are traditional strategies to reduce social negligence and crime in communities. To this end, the interviewee stated that, based on their respective cultures, the following rituals were used depending on the type and severity of the conflict: Oaths and swearing are mostly done for serious cases such as land disputes, theft, killing, and other serious issues. Respondents outlined the basic processes of conflict transformation that were practiced in the Konso and Ale ethnic groups.

3.2.1. Conflict-halting using sacred or ritual sticks

Traditional and clan leaders, rituals, and traditional beliefs play a significant role in transforming conflicts between their communities. The key informants of Konso and Ale reported that the conflict between clans in the neighbouring communities was settled by the messengers of clan leaders called Sarko (for Ale people) and Sara Poqohalla (for Konso people). Clan messengers first go to the site of the conflict with a leaf called ‘Besana’ (for Ale) and Hnsabita (for Konso) and place the leaf between the people who are fighting. One of the Ale key informants, (AKI), narrated that:

Once the messengers arrive, the conflict is stopped, and the messengers then return to the tribal leaders and report the conflict situation to their respective clan leaders. The messengers further reported that they arrived at the site of the conflict, pacified their respective parties, prevented damage, and then suggested to the leaders that they better go there and investigate the cause of the conflict and begin the process of reconciliation. Therefore, the clan leaders also go to the conflict area together to assess injuries and calm people down. They then begin the reconciliation process to prevent further casualties (AKI-3, Ale).

3.2.2. Swearing and cursing

This system is used as one of the ways to transform conflicts in the area. Respondents from the Konso and Ale ethnic groups agreed that the main objective of traditional and clan leaders is to investigate the root cause of the conflict and return the community to its previous peaceful relationship through ritual practices (oath or curse). Moora and Moorite are places of justice where cursing and swearing are held for the Konso and Ale ethnic communities. Respondents during an in-depth interview stated that lying to justice and clan leaders and elders has negative consequences for the property and lives of individuals, including the offending clan members (II-5, Konso). The insights from the results show that the truth-seeking process in the history of the traditional reconciliation process of the two communities did not remain a story but was seen in practice. One key informant in Konso recounted that:

‘If someone lies, denies the truth, and swears falsely, he enters a house with a curse, and God will punish him with death or he will soon face trouble. Moreover, if the conflicting parties break their agreement and oath and return to the conflict after they have agreed, they will be formally and ceremonially imprecated and excommunicated from the community’ (KKI-1, Konso).

Assefa (Citation2012) revealed that in the process of transforming the conflict among the Sidama and Afar peoples, lying after swearing at the place of justice and before the elders will have negative effects on the individual, their property, and the whole family. People who take the oath fear the same curse to re-enter the conflict; instead, both individuals and groups in conflict revert to their previous relationships. Therefore, the above swearing process can be generalised because CIs are more effective in transforming conflicts.

3.2.3. Slaughtering animals and blood cleansing

According to the discussion group participants, the process of purifying and blessing criminals is almost similar in both ethnic groups. Slaughtering animals and purifying the blood are other steps in performing the rites of compensation, which include pacifying the land in places where people have been killed during the fighting and purifying criminals by sacrificing animals (FGD-1, Konso). However, the amount and degree of strife determined the type of cattle to be obtained for scarification. This purification process is called Tibatte (for the Ale people) and Dhigan Dhaqta (for the Konso people). Conflicted people are believed to be cleansed of sin and revenge. One of the leaders of the Ale clan reported that:

In the usual system of Ale’s conflict resolution, the purification ceremony is called Tibatte, and it takes place after people confess their guilt. The process is done when a cow or goat is slaughtered, and its blood and stomach contents are sprinkled on the ground. This ceremony is performed to purify the land where blood has been spilled. All the bad deeds of the past are henceforth washed away with blood. After this process, there will be no complaints among the disputants, and they will live peacefully as before (AKI-3, Ale).

In the 1980s, there was a conflict between Konso and Borana that caused great damage to human life and property. An action that was implemented in the reconciliation system was that a bull was slaughtered at the bordering place of conflict, and then two people, one man from Konso and one man from Borana, were made to hold the leg bone of the bull and break it in the middle. Next, the bone on the Konso man’s hand was buried on the Borana side, and the bone on the Borana man’s hand was buried on the Konso side. This means that Borana and Konso are inseparable communities, and no conflict will arise between them in the future (KKI-2, Konso).

These processes and procedures are compatible with Alula and Assefa’s (Citation2012) investigation of the Amhara and Somali clans in eastern Ethiopia. They learned from their research that the Amhara and Somali clans slaughter two oxen—one for Christians and one for Muslims—as part of the ceremony to settle disputes. As a gesture of goodwill, each party holds the ox’s head while it is being slaughtered. Then they would swear an oath, make a promise, break the legs of the other cattle as a symbol of the oath, and declare that if they broke the agreement, the same would happen to them. Conducting this ceremony is crucial to transform conflicts, pave the way for reconciliation, and assist parties in returning to their previous partnership status.

3.2.4. The ceremony of burring things

Another ceremony performed during reconciliation after sacrifices have been made is the burial of objects used as signs of the culmination of enmity. In addition, it is a system of burying an object or parts of an animal’s body in the ground to signify an end to enmity and violence and to remind a person who breaks his oath and becomes the source of conflict that he will face the same fate as the buried thing. One of the Konso traditional leaders stated:

An action was taken to resolve the Konso-Borana conflict, in which both sides came out with a spear and buried it in a dug pit. So, the people on the Borana side turned the sharp side of the spear to themselves and buried it, and the people on the Konso side also turned the sharp side of the spear to themselves and buried it. This means that if anyone tries to cause conflict between the two sides by violating this agreement, the spear will pierce him and his whole family (KKI-2, Konso).

In the 1970s, there was a conflict between us over farmland. The traditional and clan leaders of the time transformed the conflict and built a marker on the border of the two communities. The place is called ‘Haredi,’ where an oath was carried out. The oath was taken to ensure the possession of the land and the end of hostilities. This was confirmed by the fact that burying a donkey and a cow’s leg together is the end of conflict and avoiding future claims of land possession in the area (AKI-4, Ale).

3.2.5. The ceremony of blessing and eating together

Decision-making and dispute transformation depend on extensive deliberation to create an agreement, following which the leaders summarise their viewpoints. As the respondents stated, eating together is the last step in the reconciliation process, which guarantees the restoration of the previous relationship between the feuding parties. According to the interviewee, the disputing revellers baked and consumed the slaughtered animal. The process involves combining the food and drinks that the disputing parties have brought, and then the leaders force them to eat and drink together. This suggests that the conflicting parties show their determination to work together to transform disputes and establish peace by eating a jointly sacrificed animal. All these activities demonstrate the traditional and tribal leaders’ sense of responsibility towards their community and cultural system and their desire to bring peace to the community (II-5, Ale). One of the Konso clan chiefs recounted that:

Following the reconciliation ceremony, leaders perform cleansing work to prevent resentment and revenge from lingering between conflict participants and causing future issues. To this end, the meat of the slaughtered animal is divided equally between the disputing parties, and the meat is reunited and roasted at the place where the reconciliation took place. All conflicting parties must eat the slaughtered meat together, which indicated that they first quarrelled and separated, and now they have reconciled and are back to their previous positive relationship (KKI-3, Konso).

3.3. The challenges and changing patterns of the customary institutions

The present study addresses the challenges and changing patterns of customary institutions in both the societies of Konso and Ale. There are various perspectives on the impact of the loss of the independent power of CIs on the emergence of violent inter-ethnic conflicts. Jalata (Citation2012) and Tesfaye (Citation2012) stated that the state-building project, the arrival of missionaries, and the infusion of socialist doctrine all contributed to the worsening circumstances that eventually caused the decline of the CIs in Ethiopia. However, key informants from Wereda and zonal officials (WOIs) and ZOIs, asserted that the low status of CIs can be due to the newly-appearing ethnic-based administration, which has set up conflicts in the area. They also agreed that the current nature and dynamics of conflicts and modernization hinder customary systems from independently transforming conflicts (KKI-4 Konso and AKI-4 Ale).

The study found that the 1991 ethnic-based political structure led to a division between the Konso and Ale ethnic groups, who had previously shared the same administrative boundaries, and caused a significant conflict. The complexity of this inter-communal dispute made it challenging for CIs to transform the persistent conflicts. In addition, the spillover of limited resources indicates the potential for serious disputes between the two ethnic communities since the 1991 regime. The study of Oladipo (Citation2022) showed that complex ethnic issues pose challenges to the efficiency of current traditional techniques of conflict resolution. Assefa (Citation2012) stated that, despite not being included in formal law before the 1991 government regime of Ethiopia, CIs played a vital role in conflict transformation. However, their role has significantly eroded since the establishment of the new state structure in 1991.

In like manner, participants in the FGDs repeatedly emphasised that CIs had had significant authority and influence in the Ethiopian political system before 1991. The participants generally hold the view that the post-1991 as well as the post-2018 attempts to replace CIs with newly established government structures at various echelons (e.g., Zone and Wereda) have lowered the status, values, and power of customary systems. Moreover, at present, other politically motivated formations (e.g., Joint Peace Committees, ‘1:5 Group Structure, and Kebele/Sub-municipality Development Committees), which, according to the informants, are subservient to the ruling party, have been replacing the CIs in the area (FGD-1 Konso and Ale). Assefa (Citation2012) stated that there is no precise law governing the state of affairs in customary systems, either at the regional or federal level. This refers to the authoritarian style of the ruling parties (including the former EPRDF and the current Prosperity Party) of forcibly licking the communities into the shape of rank-and-file in countless 5-to-1 groups, bottom-up as well as top-down, across the entire country, including school students and teachers. Each group is led and spied by one person who is selected as an ardent supporter and, hence, a beneficiary of the ruling party’s assets. Therefore, due to their limited power, CIs are no longer autonomous enough to address inter-ethnic conflicts.

Respondents argued that the formation of the Konso-Ale Joint Peace Committee and its attempt to resolve their conflict is another effort to suppress CIs in their communities. This is because the committee’s plan was essentially a showpiece to guarantee the will of the government in contrast to the interests of the people (FGD-1, Konso). Designating the committee as a remedial measure did not bring about major changes for local communities. Instead, it caused a lack of trust in CIs and the loyalty of traditional actors. One of Ale’s key informants recounted that:

The current situation is surprising to us. The younger generations have shown disrespect towards the clans, traditional leaders, and ritual practices of the Ale ethnic groups. Moreover, the government and the 1:5 group arrangement are attempting to replace customary systems by establishing joint peace committees to handle everything internally. As traditional systems often fail for the reasons explained, elders tend to become dissatisfied (AKI-3, Ale).

In the past, fathers and forefathers utilised their indigenous knowledge to address personal and criminal issues within the community without government intervention. However, traditional and clan leaders are losing control over their public, while government-appointed traditional leaders gain more power due to their political necessity (II-1, Ale).

Many clans and traditional leaders are strict and still follow conservative practices and rituals that go against their belief in God. As a result, the majority of communities converted to Christianity; thus, the traditional system of reconciliation is no longer widely accepted. They have abandoned the practices they used to follow. Therefore, the customary institutions of Konso are currently unable to fulfill their traditional duties (KKI-1, Konso).

Based on the findings, in the history of both communities, clans and traditional leaders had sovereign power over their communities. However, in the post-1991 system of governance, the sovereign authority of traditional judges as well as the role of their CIs were severely diminished and rendered ‘outdated’ by the regimes. The post-1991 constitution advocates a policy of cultural self-determination for the country’s multilingual communities, aiming to reduce ethnic conflicts. For instance, Art. 9 (1), Art. 34(4), and Art. 78(5) addressed the applicability of customary laws in the nation (Epple & Assefa, Citation2020). Accordingly, the constitution acknowledged that issues only related to family and personal matters could be resolved through customary and religious courts. As a result, the state legal system continues to dominate public law domains and reduces the responsibilities of CIs to personal and family matters. Moreover, unawareness among the young generations about the traditional values and norms and the interest of governmentally appointed traditional leaders in land possession also led to a loss of status and authority for CIs.

4. Conclusion

The objective of the study was to thoroughly analyse the role of CIs in transforming the Ale-Konso conflict in southern Ethiopia and the challenges they have been facing, specifically since 1991. In summary, we have shown in the present study that the Konso and Ale ethnic groups have CIs that have existed as long as humans have existed. The institutions undoubtedly existed long before they were subjected to formal state institutions and laws and were responsible for addressing different types of conflicts. They utilised various rituals and techniques to bring the opposing sides together to negotiate and promote reconciliation, communal practices, peaceful coexistence, forgiveness, and respect based on accepted values, norms, cultural settings, and traditions. However, despite Ethiopia’s 1991 federal government’s promotion of cultural self-determination for ethnolinguistic communities, allowing religious and customary law to address personal disputes, criminal matters require formal legal systems, which is true for the Konso and Ale CIs.

Having limited authority lack of attention from legal systems and formal state institutions, and the replacement of traditional courts by politically oriented local institutions, challenges the legitimacy and authority of the customary institutions of the Konso and Ale communities in transforming conflicts. The new state structure since the 1991 era, the erosion of customary cultural settings, norms, and values, and the complexities of current ethnic conflicts and changing realities also affect the sustained effectiveness of CIs. The growing influence of modern education and practices, especially among the younger generations, has overshadowed customary practices.

Moreover, due to the politicisation of ethnicity, traditional leaders often face bias in safeguarding their respective ethnic groups’ interests, rendering CIs ineffective. Moreover, the spread and introduction of Protestantism and the growing influence and identity controversy among the Ale ethnic group have had negative effects on customary practices, hence leading to the institution’s existence being called into question. The sum of all challenges has led to a decline in traditional values, morals, norms, and respect for societies. If conditions continue on current trends and no action is taken, the already disturbed customary systems of Konso and Ale will soon be missed.

5. Recommendations

Recent literature highlights that the political regime of Ethiopia’s post-1991 period overshadowed the traditional values and norms of the society’s different ethnic groups. The study findings show that, despite having centuries-old CIs, the Konso-Ale conflict has worsened due to inter-communal polarisation, which has been brought about by the introduction of a new ‘ethnic-based’ undemocratic federalism framework that is actually aimed at ensuring the right to self-rule. Unfortunately, due to the complex nature of the conflicts, the anticipated roles of CIs in addressing the Konso-Ale dispute and promoting harmony between the two ethnic communities were not achieved. Utilising CIs to transform the complex conflict sparked by politicised ethnicity and structural-led administrative boundary issues has been difficult. Hence, the government needs to reconsider the current political structure in the country and ensure its effective implementation. This is necessary to maintain clear awareness among the communities regarding using the existing resources, which is commonly essential for the peaceful coexistence between the two ethnic groups.

Many modern educational institutions, religious organisations, and even some modern societies, including young people, often perceive traditional and clan leaders as conservative, outdated, and irrelevant in today’s modern world. The youth’s and religious communities’ gradual abandonment of cultural practices led to a significant shift in customary systems. It is crucial to educate younger generations about their community’s cultural values and their importance to overcome the current conflict between Konso and Ale. Educated and religious groups are also reevaluating the effective role of CIs in promoting cultural values of conflict transformation.

The study reveals that the people of Konso and Ale have deep-rooted customary mechanisms with strong social bonds based on understanding and psychological strength. The dominance of government actors and the discriminatory process of reconciliation by excluding the right victims and traditional figures is one of the most challenging issues for existing CIs. It is essential to involve all relevant parties to create a more comprehensive and effective conflict transformation approach. Therefore, the regional and local governments must let the key stakeholders, especially the traditional and clan leaders who represent their communities and make decisions based on reality, participate in the process of conflict transformation.

The Konso and Ale issues have become a challenge for both the CIs and state legal systems, and both were unable to bring about a lasting solution. Therefore, it is crucial to strengthen and enhance the capabilities of CIs in the modern era, just as it was necessary in the pre-1991 era. To restore their previous authority and uphold their sacred indigenous beliefs, the government should give clear authority to CIs to address the ongoing Konso-Ale ethnic conflict through the constitution and other policies. By rebuilding trust and sharing resources as they did before, the regional government should play a vital role in legally resolving the land claims between the two ethnic groups. This can be accomplished by following well-established procedures and policies for the effective implementation of a federal system, resource allocation, utilisation, and distribution.

List of Key Informant Interviewees

(II), stands for In-depth Interviewees

(KII) stands for Konso In-depth Interview

(KKII) stands: for Konso Key Informant Interview

(AII) stands for Ale In-depth Interview

(AKII) stands for Ale Key Informant Interview

(FGDs) stands for Focus Group Discussion

oass_a_2294553_sm0083.docx

Download MS Word (13.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We want to express our gratitude and respect for the study participants. We gratefully acknowledge Haramaya University Research Affairs and the Ministry of Education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mulumebet Major

Mulumebet Major, is a Ph.D. candidate in Peace and Development Studies at Haramaya University, Haramaya, Ethiopia. She is also a lecturer in the Department of Governance and Development Studies at Hawassa University, Ethiopia. Her research interests are in the role of customary institutions, ethnic conflict, and conflict transformation.

Fekadu Beyene

Fekadu Beyene, Ph.D., Professor of Institutional and Resource Economics, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Africa Centre of Excellence for Climate Smart Agriculture and Biodiversity Conservation, Haramaya University.

Gutema Imana

Gutema Imana, Ph.D. is an associate professor of sociology in the Department of Sociology at Haramaya University.

Dereje Tadesse

Dereje Tadesse, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of English, Literacy, and Critical Social Science at the College of Social Science and Humanities at Haramaya University.

Tompson Makahamadze

Tompson Makahamadze, Ph.D., Conflict Analysis and Resolution, School of Peace and Conflict Resolution, George Mason University

References

- Achieng, A. S., 2015. The role of women in conflict management: an assessment of Naboisho conservancy in Kenya [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Nairobi.

- Akinola, A. O., & Uzodike, U. O. (2018). Ubuntu and the quest for conflict resolution in Africa. Journal of Black Studies, 49(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934717736186

- Ali, M. A., & Bukar, H. M. (2019). Traditional institutions and their roles: Toward achieving stable democracy in Nigeria. Journal of Public Value and Administrative Insight, 2(3), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.31580/jpvai.v2i3.899

- Appiah-Thompson, C. (2020). The concept of peace, conflict and conflict transformation in African religious philosophy. Journal of Peace Education, 17(2), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2019.1688140

- Assefa, A. G. (2012). Customary laws in Ethiopia: A need for better recognition? A women’s rights perspective. Danish Institute for Human Rights.

- Assefa, G. (2020). Chapter 2. Towards widening the constitutional space for customary justice systems in Ethiopia. Culture and Social Practice, 43–62.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

- Demissew, B. (2016). Inter-ethnic conflict in South Western Ethiopia: The case of Alle and Konso [Doctoral dissertation]. Addis Ababa University.

- Enyew, E. L. (2014). Ethiopian customary dispute resolution mechanisms: Forms of restorative justice? African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 14(1), 125–154.

- Epple, S., & Assefa, G. (2020). Legal pluralism in Ethiopia: Actors, challenges, and solutions (p. 414). Transcript Verlag.

- Gelebo, T. T., 2016. Clanship identity formation among the Konso of Southern Ethiopia [Doctoral dissertation]. Arba Minch, Ethiopia.

- Gezu, G., 2018. Assessment of factors affecting interregional conflict resolution in federal Ethiopia: The case of Oromia and Somali Regions [Doctoral dissertation, MA Thesis]. College of Law and Governance Studies, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

- Ghebretekle, T. B., & Rammala, M. (2018). Traditional African conflict resolution: The case of South Africa and Ethiopia. Mizan Law Review, 12(2), 325–347. https://doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v12i2.4

- Given, L. M. (2008). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage.

- Helen, G., 2018. Response of federal institutions to the Oromo Somali Ethnic Conflict In 2017: Ministry of federal and pastoral development affairs and house of federation [Doctoral dissertation].

- Jalata, A., 2012. Gadaa (Oromo democracy): an example of classical African Civilization. Journal of Pan-African Studies, 5, 126–152.

- Joint Multi-Agency Emergency Need Assessment (JMAENA). 2020. Report. SNNPRS, Ethiopia

- Kariuki, F. (2015). Conflict resolution by elders in Africa: Successes, challenges, and opportunities. Challenges and Opportunities. Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates Publisher.

- Kassa, S. A. (2020). Managing land conflicts in plural societies: Intergroup land governance in Ethiopia. Universiteit van Amsterdam.

- Kinfemichael, G., 2014. The quest for resolution of Guji-Gedeo conflicts in southern Ethiopia: A review of mechanisms employed, actors and their effectiveness. Ethiopian Journal of the Social Sciences and Humanities, 10(1), 59–100.

- Kirby, J. P. (2006). The earth cult and the ecology of peacebuilding in Northern Ghana. African knowledge and sciences: Understanding and supporting the ways of knowing in Sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 129–148). COMPAS.

- Labović, V. V., 2014. The role and importance of integrated communications in local government. Tehnika, 69(1), 139–144.

- Lederach, J. P. and Maiese, M., 2009. Conflict transformation: A circular journey with a purpose. New Routes, 14(2), 7–11.

- Mboh, L. (2021). An investigation into the role of traditional leaders in conflict resolution: The case of communities in the Mahikeng Local Municipality, North West Province, South Africa. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 21(2), 33–57.

- Mengesha, A. D. (2016). The role of Sidama indigenous institutions in conflict resolution: in the case of Dalle Woreda, southern Ethiopia. American Journal of Sociological Research, 6(1), 10–26.

- Mohajan, H. K., 2018. Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. Journal of Economic Development, environment, and People, 7(1), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.26458/jedep.v7i1.571

- Okpevra, U. B., 2023. Nature of conflict and the prospect of traditional institutions of conflict resolutions in contemporary Africa: The Nigeria example. International Journal of Institute of African Studies, 24(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.53836/ijia/2023/24/1/009

- Oladipo, I. E., 2022. Traditional institutions and conflict resolution in contemporary Africa, African Journal of Stability & Development, 21(1), 224–244 https://doi.org/10.53982/ajsd.2022.1401_2.10-j

- Pankhurst, A., & Assefa, G. (2016). Grass-roots justice in Ethiopia: The contribution of customary dispute resolution. Centre Français des Études Éthiopiennes.

- Psaltis, C., Carretero, M., & Čehajić-Clancy, S. (2017). History education and conflict transformation: Social psychological theories, history teaching, and reconciliation. Springer Nature.

- Siyum, B. A. (2021). Underlying causes of conflict in Ethiopia: Historical, political, and institutional? Diamond Scientific Publishing.

- Tesfaye, F. (2012). The D’irasha and the collapse of their indigenous institutions: The study of a community in south-western Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa. Global Institute for Research and Education.

- Wondimu, H., 2013. Federalism and conflicts’ management in Ethiopia: Social psychological analysis of the opportunities and challenges. IPSS/AAU.

- Yusuf, S., 2019. What is driving Ethiopia’s ethnic conflicts? ISS East Africa Report, 2019(28), 1–16.

- Zuure, D. N. (2020). Indigenous conflict resolution and peace-building among the Nabdam of Ghana. Conference on Multidisciplinary Research (MyRes) (p. 181). https://doi.org/10.26803/MyRes.2020.13