?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Although leadership determines the performance of farmer organizations, the leadership styles used by farmer organizations in Uganda and factors influencing such styles have received limited attention in empirical studies. The available studies have focused mainly on the influence of leadership on performance, effectiveness, accountability, and transparency. This study determined: (1) leadership styles used by farmer organizations in Uganda; (2) differences in farmer organizational characteristics across the styles; and (3) factors that influence such styles. This study contributes to the understanding of leadership styles used by farmer organizations in Uganda and the factors that influence the choice of such styles. In order to collect quantitative data, a cross-sectional survey of 272 systematically selected farmer organizations was conducted in 12 districts of central and northern Uganda. 59.56% of farmer organizations used both democratic and autocratic leadership styles, according to the findings. Furthermore, savings and loan scheme, leadership passion, farm management training, leadership and management training, leaders’ expertise, and leadership committee numbers varied across leadership styles. The logit results showed that the savings scheme, number of organizational departments, leadership passion, usage of market outlets, total costs, and leadership and management training influenced the use of both democratic and autocratic leadership styles. However, the use of solely the democratic leadership style was influenced by committee size, total income, and value-added training. Farmer organizations should continue to use both democratic and autocratic leadership styles for efficiency and effectiveness. Governments and other development partners should strengthen leadership and management training for farmer organizational leaders.

SUBJECTS:

1. Introduction

Over one-third of the world’s population relies on agriculture for a living (Alston & Pardey, Citation2014; FAOSTAT, Citation2013). The majority of them are smallholders who face a variety of challenges that prevent them from experiencing consistent agricultural growth (Abraham & Pingali, Citation2020; Woodhill et al., Citation2020). They continue to live in substandard conditions, which ultimately lowers their earnings potential (Abraham & Pingali, Citation2020; Fan & Rue, Citation2020). To overcome these obstacles, smallholder farmers have been urged to create farmer organizations over the years to successfully and efficiently transition from subsistence to commercially focused farming (Frank & Penrose Buckley, Citation2012; Bizikova et al., Citation2020).

Worldwide, farmer organizations are renowned for assisting smallholder farmers in transitioning from subsistence to commercial production (Adong et al., Citation2013; Ampaire et al., Citation2013; Latynskiy & Berger, Citation2016; Owusu et al., Citation2013). They are significant ways to unite farmers behind a shared goal and are viewed as ways to implement policies and deliver services effectively (Frank & Penrose Buckley, Citation2012; Lin et al., Citation2021). Additionally, they help smallholder farmers overcome past obstacles that prevent them from maintaining agricultural growth. Farmer organizations minimize transaction costs, facilitate the adoption of new technologies, increase access to markets for inputs and outputs, and strengthen the bargaining position of smallholder farmers (Sinyolo & Mudhara, Citation2018). Furthermore, farmer organizations help mobilize and distribute financial capital, create solidarity schemes, and generate employment and income opportunities.

With the emphasis on the group approach to agricultural extension services provision in most of Sub Saharan Africa (SSA), numerous farmer organizations have sprouted up in response to the appeal, with Uganda being no exception. In the past, farmer organizations in Uganda belonged to the state and were managed by village chiefs (Barungi et al., Citation2015). The chiefs took advantage of their power to compel farmers to adopt new technologies and boost their agricultural productivity. Historically, progressive farmers have offered technical assistance, input, and financing to other farmers. The method and similar methods became unsuccessful and unsustainable because of conflicts among farmers (Barungi et al., Citation2015). Member-owned farmer organizations arose as a result of this.

Currently, farmer organizations in Uganda are self-governing and member-owned. In addition, they operate as profitable and self-sufficient businesses (Latynskiy & Berger, Citation2016). The establishment of farmer organizations in Uganda is based on the common interests of farmers. Members pay a subscription fee to join the organization, and membership is voluntary and available to everyone (Latynskiy & Berger, Citation2016). Leadership normally comprises a chairman, vice-chairperson, secretary, and treasurer, all of whom are democratically elected by farmers. However, there are significant obstacles that farmer organizations must overcome to succeed (Adong et al., Citation2013; Latynskiy & Berger, Citation2016; Mwaura, Citation2014). These limitations include: lack of member commitment, inadequate organizational structures, lack of coordination among farmer organizations, poor mobilization, inadequate information and training, and insufficient leadership assistance (Ampaire et al., Citation2013; Wouterse & Francesconi, Citation2016). If farmer organizations adopt effective leadership philosophies, the aforementioned challenges could be successfully managed.

1.1. Literature review

Leadership is a process in which one person guides, coordinates, and supervises others as they perform a common task (Khan et al., Citation2015). Effective leadership involves directing individuals towards shared objectives and giving them the freedom to take the necessary steps. It involves the capacity to persuade someone or a group to work towards a common objective (Khan et al., Citation2015). Leadership plays an important role in determining the performance of farmer organizations (Latynskiy & Berger, Citation2016). According to Lin et al. (Citation2021), the leadership of an organization determines its transparency and effectiveness. The flow of resources, adoption of new technologies, sanctioning of behavior, upholding of the group’s mission, and handling of internal conflicts depend heavily on leaders (Decuypere & Schaufeli, Citation2020; Lin et al., Citation2021). Leaders also connect their members to high-value marketplaces to increase the margins of their produce, advocating for institutional services such as marketing, extension services, and credit services. Leaders have a significant impact on members’ willingness to selflessly contribute to achieving desired results (Decuypere & Schaufeli, Citation2020). Consequently, performance and organizational goals can be achieved more easily.

Different types of leadership can be used. A leader may practice any style of leadership, including democratic, autocratic, and laissez-faire, as may be deemed necessary (Crosby, Citation2021; Martin, Citation2015). In a democratic leadership style, the leader of an organization allows members of the organization to participate in decision-making (Crosby, Citation2021). This style fosters power-sharing, understanding, holistic learning, and a sense of agency, and addresses power imbalances. This consequently promotes the innovation and performance of the organization. However, this style is time-consuming (Khan et al., Citation2015).

In the autocratic leadership style, the leader has the most control and decision-making authority (Goleman, Citation2017; Khan et al., Citation2015). Employees are not allowed to offer any input or consult with the leader. Employees are expected to follow instructions without any explanation. This style uses rewards and penalties to motivate organizational members. However, compared to other organizations, those with authoritarian leaders typically have greater absenteeism and turnover rates.

In the laissez-faire style, the leader does not actively participate in decision making (Goleman, Citation2017; Khan et al., Citation2015). The leader entirely allows workers as much latitude as possible while offering limited and/or no direction to the employees. Employees are given complete control, and they are required to set their own objectives, make decisions, and deal with issues. However, the laissez-faire style of leadership can easily cause misunderstandings and fights within an organization (Crosby, Citation2021). In addition, it may lead to suboptimal results or a lack of harmony in the organization.

Literature is replete with the factors that influence leadership styles that an organization chooses. The region of operation, organizational age, original purpose, type of business conducted, amount of value added by a farmer’s organization, savings, and committee size are a few of these factors that may be taken into consideration (Crosby, Citation2021; Goleman, Citation2017; Khan et al., Citation2015; Martin, Citation2015). Additional factors that may affect the leadership style used in an organization include the number of departments within it, the age of its members, the leader’s other sources of income, the channels through which it is distributed, the costs involved, the worth of its physical assets, the amount of money it brings in, and its financial dependence (Martin, Citation2015; Stempel et al., Citation2015). Doraiswamy (Citation2012), Smith (Citation2015), and Srivastava (Citation2016) contend that the behavioral traits of individual leaders, such as propensity to mentor, train, or develop team members, propensity to delegate, and enthusiasm for leadership, can have an impact on the types of leadership practices utilized in an organization.

According to Crosby (Citation2021), leaders can combine these styles. As organizational members gain more experience, leaders must gradually revert to a democratic leadership style after adopting an autocratic style. Using a laissez-faire approach with highly skilled employees may be necessary, but leaders must be careful not to go overboard. However, there is scarcity of literature about the influence of such factors on leadership styles used. Leadership-related concerns continue to affect sustainability of farmer organizations in Uganda (Barungi et al., Citation2015; Wouterse & Francesconi, Citation2016). While the principles of leadership and leadership styles have been extensively examined worldwide, there has been little research on the leadership styles used by farmer organizations in Uganda. Furthermore, the factors that influence the styles used by farmer organizations, as well as the extent of their influence, have scarcely been researched. Miriti (Citation2012) and Mutmainah (Citation2014) investigated the impact of leadership style on the effectiveness of farmer organizations. Lin et al. (Citation2021) investigated the impact of leadership on technology adoption, while, Omotesho et al. (Citation2019) investigated the impact of member characteristics on leadership effectiveness. Peterson et al. (Citation2012) researched the influence of a leader’s characteristics and behaviors on the performance of an organization. On the other hand, Ampaire et al. (Citation2013), researched the influence of a leader’s dedication, respect and commitment on effectiveness of a farmer organization. In their study, Ampaire et al. (Citation2013), measured effectiveness of a farmer organization by the number of farmers who sell their output through the organization, and not by leadership styles used by the organization. In addition, their paper does not show how a leader’s dedication, respect and commitment influence effectiveness of a farmer organization. Achdiyat (Citation2018) also assessed the influence of leaders’ behaviors and characteristics, on effectiveness of farmer organizations. However, Achdiyat (Citation2018) measured effectiveness of a farmer organization in terms of organizational productivity, moral and member satisfaction. In addition, his study used Spearman’s rank correlation for analysis. Omotesho et al. (Citation2019) researched and found out that limited knowledge of roles and poor cooperation from members hindered leadership effectiveness. However, Omotesho et al. (Citation2019) did not highlight how the factors influence the leadership style used. Lin et al. (Citation2021) researched the influence of leadership on accountability and transparency in organizations. However, in their study, Lin et al. (Citation2021) also did not look at the determinants of leadership styles used. Ellitan (Citation2022), also, only looked at the importance of organizational governance and leadership structures in farmer organizations.

This study, therefore, aimed to determine: (1) leadership styles used by farmer organizations in Uganda; (2) differences in farmer organizational characteristics across the styles; and (3) factors that influence the styles used. Specifically, this study addressed the following research questions: (1) What leadership styles are used by farmer organizations in Uganda? (2) What are the differences in farmer organizational characteristics across leadership styles used? and (3) What factors influence the choice of leadership styles by farmer organizations in Uganda? In this study, a farmer organization is a group of farmers who work together in any agricultural activity. This study contributes to the understanding of the styles of leadership used by farmer organizations in Uganda and the factors that influence the choice of the styles used. Such information supports the leadership of farmer organizations in selecting appropriate leadership styles that effectively facilitate efficient operations and competitiveness. In addition, this information can guide policymakers in developing appropriate management and leadership interventions to support the performance of farmer organizations.

1.2. Theoretical framework

This study is premised on the Vroom-Yetton-Jago model, which emphasizes that no single decision-making procedure fits every situation (Vignesh, Citation2020). Several theories exist to explain the different leadership styles (Situational Leadership Theory, the Path-Goal Theory, the Vroom-Yetton-Jago model). The Situational Leadership Theory was developed by Hersey and Blanchard (Citation1969). The theory proposes that effective leaders adapt their leadership styles based on the maturity level of their followers and the task (Thompson & Glasø, Citation2015). With subordinate maturity, the theory refers to work maturity (education and experience) and psychological maturity (self-esteem and confidence). However, this theory concentrates only on the demands of the task and maturity of subordinates and pays little attention to many other factors that can influence choice leadership styles.

The Path-Goal theory was invented by Robert House in 1971 (Bans-Akutey, Citation2021). This theory is primarily concerned with how the leader influences the perceptions of subordinates’ job goals, personal goals, and approaches to goal attainment. According to this theory, a leader employs a leadership style that supports followers in accomplishing their goals by providing proper direction, support, and incentives (Bans-Akutey, Citation2021). The theory suggests that the type of leadership chosen is determined by the characteristics of the followers and nature of the work. However, this theory focuses on the characteristics of followers and the environment. Little consideration has been given to the relevance of the decision or characteristics of the leader.

On the other hand, the Vroom-Yetton-Jagon model suggests that the best method to make a decision is to base it on the current scenario or problem rather than on the decision maker’s particular attributes or style (Vignesh, Citation2020). To establish the right level of follower involvement in decision making, the Vroom-Yetton-Jagon model suggests that a leader must examine numerous situational elements, such as the relevance of the decision, the leader’s expertise, and the followers’ capabilities and commitment (Vignesh, Citation2020). Consequently, a leader may adopt an autocratic or democratic leadership style. For example, if haste and divisiveness are desired, it points to an authoritarian procedure. If collaboration is required, this will lead to a more democratic approach. The Vroom-Yetton-Jagon model considers various aspects of the situation, that is, the nature of the decision to be made, the leader and followers. This study was therefore premised on this theory because it considers the leader, followers, task/relevance of the decision, and environment. The theory informed the model specification and guided the development of data collection tools for situational factors. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the methodology, Section 3 presents the results and discussion and Section 4 presents the conclusions and recommendations.

2. Materials and methods

A multi-stage sampling procedure was used to conduct a cross-sectional survey in two contrasting regions of Uganda, that is; northern and central. In the first stage, the two regions were purposively selected out of five regions. This was because, the northern region has the highest number of farmer organizations, is predominant in the production of annual crops (cereals, legumes, pulses, and oil seed crops), and has a history of political and civil unrest. On the other hand, the central region has fewer farmer organizations (Adong et al., Citation2013; Mwaura, Citation2014; Uganda Bureau of Statistics [UBOS], Citation2010), produces both annual and perennial crops (coffee, vanilla, and cocoa), and has enjoyed relative political stability. In terms of institutional support, the northern region receives relatively more support from both government and non-government organizations, as a way of relieving the region from poverty and food insecurity caused by the political instability (Birner et al., Citation2011). This enabled the study to obtain comparable findings about the leadership styles of farmer organizations in two diverse geographical regions of Uganda. In the second stage, 12 districts were randomly selected; seven from the northern region and five from the central region. The seven districts included Arua, Koboko, Yumbe, Gulu, Agago, Apac, and Amolatar, whereas, the five districts included Nakasongola, Mityana, Gomba, Buikwe, and Kayunga. In the third and last stage of sampling, lists of farmer organizations per district were obtained from the District Farmers Associations (DFAs) of the respective districts, and every fifth farmer organization was selected.

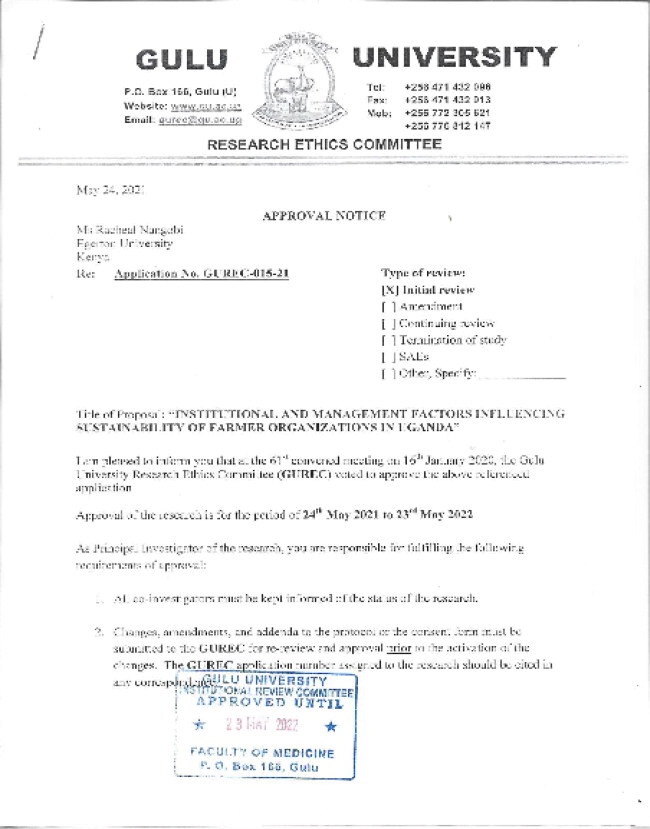

For moral justification, the study sought ethical clearance from the Gulu University Research and Ethics Committee (GUREC) (Appendix A). Furthermore, before interviewing farmer organizations, permission was obtained from District Farmers’ Associations (DFAs) and community leaders. Informed consent was also obtained from all study participants. A researcher-administered pre-tested questionnaire was used to obtain quantitative primary data for the study from 272 farmer organizations (Fawcett, Citation2015; Santos et al., Citation2017). The sample size was determined using Cochran’s (Citation1963) formula in EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) :

(1)

(1)

where n is the sample size, Z2 is the abscissa of the normal curve that cuts off an area at the tails, e is the desired level of precision, P is the estimated proportion of an attribute present in the population. Z is 1.96, and e2 is 0.05. To obtain the sample size for farmer organizations, this study assumed P to be 0.23, as there are few farmer organizations that have good leadership and are thus able to survive in an ever-changing environment (Barungi et al., Citation2015; Latynskiy & Berger, Citation2016; Wedig & Wiegratz, Citation2018). Substituting 0.23 in the formula generated 272.

The 272 farmer organizations were distributed proportionately between the northern and central regions (EquationEquation 2(2)

(2) ).

(2)

(2)

represents the number of farmer organizations interviewed per region,

represents the approximate number of farmer organizations per region,

represents the approximate total number of farmer organizations in the two regions, and

represents the total number of farmer organizations interviewed for the whole study (272).

The northern region had approximately 18,644 farmer organizations, while the central region had approximately 7,177 (; UBOS, Citation2010). Altogether, there were approximately 25,821 registered farmer organizations across the two regions ().

Table 1. Total number of farmer organizations and those sampled per region.

However, due to Covid-19 restrictions, only 177 farmer organizations were interviewed in northern Uganda. The discrepancy was, however, compensated for in central Uganda, where, 95 farmer organizations were interviewed, to achieve a target sample size of 272. Trained research assistants administered questionnaires to collect the data.

SPSS 24 was used for data entry and STATA 13 software was used for analysis. The data were examined for multi-collinearity among variables using a correlation matrix (Appendix B). To determine the leadership styles used by farmer organizations and the differences in characteristics of farmer organizations across the styles, descriptive statistics (chi-square and t-tests) were generated (Waller & Johnson, Citation2013). Guided by the Leadership Practices Inventory (Kouzes & Posner, Citation2003), three statements were utilized to examine the leadership styles used by farmer organizations. To the three statements, the leaders would react with justifications. The statements included: (1) ‘I discuss with my followers what to do, how to and when to do’, (2) ‘I tell my followers what to do, how to do and when to do’, and (3) ‘My followers decide on what to do, how to do and when to do’.

To determine the factors influencing the choice of leadership style used by farmer organizations, a logit regression was used for analysis. A logit regression was used because, the dependent variable leadership style was binary in nature (0= only democratic style, 1= both democratic and autocratic styles) (Del Hoyo et al., Citation2011; Minah, Citation2021). Logit regression is suitable for estimating the probabilistic relationship between one or more explanatory factors and a binary response variable that can, in essence, take values of zero and one (e.g., whether an organization has only a democratic leadership style or both democratic and autocratic leadership styles) (Promme et al., Citation2017; Suvedi et al., Citation2017).

The characteristics of a farmer organization and the leader were the independent variables and included: organization age, marketing purpose, savings scheme, organization departments, leadership committee size, organization coverage, leadership passion, leader’s other sources of income, use of outlets for distribution, organization costs, organization revenue, receipt of value addition training, receipt of farm management training, receipt of leadership and management training, leaders’ expertise, tertiary value addition, and value of physical resources (). In general, the model was expressed by EquationEquation 3(3)

(3) :

(3)

(3)

where

= Response variable, ‘leadership style (0 = only democratic, 1 = both democratic and autocratic)’,

Table 2. Logistic model variables for factors influencing choice of leadership styles.

= Constant,

…

= Parameter estimated,

= Stochastic error term; and

Explanatory variables as named in .

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Descriptive statistics

shows that the majority of farmers who used both democratic and autocratic leadership styles, had a saving and loan scheme, and were headed by passionate leaders who expressed interest in leadership, and won the election. The majority of farmer organizations interviewed pursued marketing purposes, and received farm management, leadership, and management training. However, many of the farmer organizations did not engage in the tertiary value addition of further processing of flour into other products (). This means that many organizations either added value to their produce at the primary level of just drying, sorting, and grading or at the secondary level of processing their produce into flour. The majority of the farmer organizations did not use marketing outlets other than the farm gate to sell their produce (). Lastly, many of the farmer organizations interviewed did not receive value addition training from their partners ().

Table 3. Chi square results for organizational leader’s characteristics with leadership styles.

From , the following farmer organizational characteristics were found to have significant relationships with the style of leadership used by a farmer organization: Savings and loan schemes had a significant (p ≤ 0.05) relationship with leadership styles used by farmer organizations (). The majority of farmer organizations with savings and loan schemes used both democratic and autocratic leadership styles. This implies that savings and loan schemes need more serious control than the democratic leadership style. This is because savings are always contributed to by members with the purpose of making profits through the interests earned. Thus, serious accountability, caution, and care are required to ensure the safety of members’ money (Jain & Chaudhary, Citation2014).

Leadership passion was significantly (p ≤ 0.01) related to leadership styles used by farmer organizations (). Most farmer organizations that were headed by leaders who had passion for leadership used both democratic and autocratic leadership styles. This implies that passion for leadership calls for all the necessary leadership styles for effectiveness. Leaders with passion for leadership are always fully committed and have the courage to pursue the intended purposes of a farmer organization in all ways that the leader may deem necessary (Sirén et al., Citation2016). This may include full participation in the day-to-day running of the organization and encouraging and supporting members to participate in organizational decision-making. This finding is in agreement with Ho and Astakhova (Citation2020), who found that leaders with love for leadership tend to use several leadership styles that encourage innovation, allowing feedback to acquire social acceptance, and to keep members on track.

Farm management training was significantly (p ≤ 0.01) related to styles of leadership used by farmer organizations (). Most farmer organizations that received farm management trainings used both democratic and autocratic leadership styles. This finding implies that farm management training requires an autocratic leadership style, especially during the knowledge transfer process, in which an expert guides farmers on what to do. According to Durmus and Kirca (Citation2020), an autocratic leadership style is effective in guiding inexperienced followers.

Leadership and management training were significantly (P0.05) related to leadership styles used by a farmer organization (). Many farmer organizations that received leadership and management training used both democratic and autocratic leadership styles. This finding implies that leadership and management training widens leadership knowledge. According to Seidman et al. (Citation2020), leadership training improves leaders’ knowledge and skills, which helps them use appropriate and practical leadership styles for different situations.

From , it was revealed that farmer organizations that were interviewed, on average, had been in existence for 7.2 years, had a leadership committee of six members, and had two departments. In addition, the organizations, on average, operated in one sub-county, were headed by leaders who had expertise in two fields and at least, had one other source of income than farming (). Further, reveals that the interviewed farmer organizations, on average, owned physical resources worth UGX4,406,975.00, earned UGX2,511,283.00, and incurred total costs of UGX891,575.40 annually.

Table 4. T-test results comparing means of organizational leader’s characteristics and choice of leadership styles.

From , the following differences were observed in organizational characteristics across the two categories of leadership used: leadership committee size of farmer organizations was significantly (p ≤ 0.01) different across the two categories of leadership styles used (). Farmer organizations with larger committee sizes used only the democratic style of leadership compared to organizations with smaller committee sizes. This implies that a larger committee size effectively supports a democratic style of leadership. This could be because a larger committee size brings together members with different knowledge and skills, which leads to quality decision making (Elmaghrabi, Citation2021). Golensky and Hager (Citation2020) also supported the idea that a larger committee size improves the capacity to make quality decisions.

Leaders’ expertise differed significantly (p ≤ 0.01) across the two categories of leadership styles used by farmer organizations (). Organizational leaders with expertise in more fields, such as production, marketing, leadership, and financial management used both democratic and autocratic leadership styles, as compared to those who had expertise in one field. This implies that having expertise in more fields increases leaders’ autocracy power. This is because leaders with expertise in more than one field have diverse knowledge and skills, which puts them in better control of organization members (Goleman, Citation2017). This finding is also supported by Khan et al. (Citation2015), who also suggest that more knowledgeable leaders tend to be autocratic as a way of guiding organizational members on what to do.

3.2. Logistic regression results for factors influencing leadership styles used by farmer organizations

From , passion for leadership, use of market outlets (marketing stores and shops in different trading centers), total costs incurred (transportation, administrative, registration, farm, coordination, facilitation, and processing, among others), savings and loan schemes, number of organizational departments, and receipt of management and leadership training by a farmer organization positively influenced the leadership styles used by a farmer organization. On the other hand, leadership committee size, total revenue earned (sales, asset rent, earnings from savings, fines, registration, and subscription), and receipt of value addition training had a negative influence on leadership styles used by a farmer organization ().

Table 5. Logit results for factors influencing leadership styles used by farmer organizations in Uganda.

also presents tests for model fit and confirms that the model fits the data. This is shown by the Prob > chi2 figure, and, further confirmed by the sensitivity, specificity, and overall classification of the model.

The savings and loan scheme had a significant (p ≤ 0.01) positive influence on the leadership style used by a farmer organization (). Holding other factors constant, having a savings and loan scheme increases the probability that a farmer organization uses both democratic and autocratic styles of leadership by 22.25%. This implies that savings require tighter control measures to prevent defaulting and ensure the safety of members’ money, which cannot be attained by using only a democratic style of leadership. According to Eken et al. (Citation2014), an autocratic leadership style offers more supervision and control to followers, which can help control savings. This idea is also supported by Jain and Chaudhary (Citation2014) and Mohammad et al. (Citation2017), who suggest that an autocratic leadership style can support situations that involve serious safety risks. As the democratic style ensures effectiveness in an organization, the autocratic style can help control money-handling activities and ensure proper accountability, responsibility, and avoid loan defaulting by organization members.

The leadership committee size of a farmer organization had a significant (p ≤ 0.01) but negative influence on the leadership styles used (). Other factors held constant: an increase in the leadership committee size of a farmer organization reduces the probability that the organization would use both democratic and autocratic leadership styles by 6.25%. The implication of this is that larger committee sizes reduce the power of a leader as a central decision maker, as it brings together a wide range of skills, knowledge, and expertise, which can effectively support quality decision-making (Golensky & Hager, Citation2020). This finding is supported by Jouber (Citation2020), who posits that committee diversity improves organizational decision making.

The number of departments in a farmer organization had a significant (p ≤ 0.05) positive influence on leadership styles used by the organization (). An increase in the number of departments of a farmer organization by one department, increases the likelihood that the organization uses both democratic and autocratic leadership styles by 6.87%, holding other factors constant. This indicates that, as an increase in organization departments increases specialization and, consequently, quality of work done, the farmer organization leader may still need supervision, guidance, check progress against goals, and keep members on track. This finding is supported by Aldoshan (Citation2016), who also suggests that leaders dealing with many departments must use a combination of styles because different departments pause a diversity of skills, knowledge, and culture that cannot be managed by one leadership style.

Leadership passion significantly (p ≤ 0.01) and positively influenced the leadership styles used by farmer organizations (). Ceteris paribus, passion for leadership increases the likelihood that a leader of a farmer organization uses both democratic and autocratic leadership styles by 13.46%. The implication of this is that passion for leadership brings about full engagement and commitment in a leader, to achieve his/her goals and help members achieve their goals too. Thus, a leader uses a combination of leadership styles, depending on the situation and task at hand, to ensure that organizational goals are attained (Sirén et al., Citation2016). According to Sirén et al. (Citation2016), passion for leadership makes a leader clearly communicate the vision of a group, inspire innovative thinking, and seek feedback from group members, thereby using a democratic style. However, in an attempt to keep group members on track, pursue personal agendas, acquire social acceptance, and improve their self-esteem, the leader must use an autocratic style. This finding is in agreement with Ho and Astakhova (Citation2020), who found that leaders who have love for leadership tend to use several leadership styles that encourage innovation, allowing feedback to acquire social acceptance, and to keep members on track.

Market outlets were found to have a significant (p ≤ 0.05) positive influence on the leadership styles used by farmer organizations (). Other factors remaining constant; the use of market outlets such as market stores and shops in trading centers and towns, for selling organizational products increases the probability that a leader uses both democratic and autocratic leadership styles by 12.33%. This indicates that the use of market outlets requires serious control measures that can regulate marketing activities and marketers’ behaviors and minimize costs incurred by the organization (Okeke, Citation2019). Mihai (Citation2015) also supports this finding, suggesting that autocratic and democratic leadership styles work better when used jointly to control organizational costs than when only the democratic leadership style is used.

The total costs incurred by a farmer organization significantly (p ≤ 0.05) and positively influenced the leadership styles used (). Keeping other factors constant, an increase in the total costs incurred by a farmer organization by one Uganda shilling increases the probability that a leader would use both democratic and autocratic leadership styles by 4.59%. This implies that the autocratic leadership style, if combined with the democratic style, can offer more effective control measures that can help to minimize costs than the democratic style if used alone. Farmer organizations incur costs, that may include, transportation, administration, facilitation, processing, farm-related, meeting-related, maintenance, registration, and subscription costs; which may not be effectively controlled by only the democratic leadership style (Mihai, Citation2015). According to Todorova and Vasilev (Citation2017), farmer organizations that incur high costs tend to use an autocratic leadership style. The autocratic leadership style helps to keenly and critically guide and monitor organizational operations in a bid to control costs and ensure efficiency for the organization.

Total revenue incurred by a farmer organization was found to have a significant (p ≤ 0.05) and negative impact on the styles of leadership used (). An increase in the total revenue earned by a farmer organization by one shilling decreases the probability that a leader uses both democratic and autocratic leadership styles by 6.19%, holding other factors constant. This finding implies that earning higher revenues attracts members’ vigilance, which increases their chances of using only the democratic leadership style. This is because the revenue earned by farmer organizations is earned out of investments that are primarily financed by members’ contributions and efforts (). Thus, any money earned by the organization should be clearly reported and jointly decided upon. This finding contradicts those of Geddes et al. (Citation2014) and Ahmed et al. (Citation2020), who suggest that higher revenues/incomes increase the probability of adopting an autocratic leadership style. Bentzen et al. (Citation2017) also posit that leaders in organizations with more revenues are less likely to use democratic leadership styles alone due to their selfish interests. The contradictions in this finding could be due to the fact that farmer organizations mostly operate on members’ contributions and savings as capital, which increases members’ alertness about earnings and thus leaves the leader with only the democratic leadership style as an option.

Value addition training had a significant (p ≤ 0.05) but negative effect on leadership styles (). Other factors held constant: receiving value addition training by a farmer organization reduces the probability that a leader uses both democratic and autocratic leadership styles by 12.15%. This finding implies that a democratic style of leadership provides a conducive environment for effective learning. According to Clinton (Citation2015), the democratic leadership style allows for participation from members, which can increase members’ morale and commitment to value-addition training and consequently lead to higher learning outcomes. Del Maestro Filho et al. (Citation2015) support the finding, as they suggest that a democratic leadership style leads to effective learning because it attracts harmony from members and allows them to participate in the learning process.

Management and leadership training significantly (p ≤ 0.05) and positively influenced the leadership styles used by farmer organizations (). Ceteri paribus, receiving management and leadership training in a farmer organization increases the probability that the leader uses both democratic and autocratic leadership styles by 17.59%. This finding implies that leadership and management training widens leaders’ knowledge and skills. According to Mutale et al. (Citation2017), leadership and management training improves leaders’ management capabilities and enables them to effectively face more difficult situations. This finding is also supported by Seidman et al. (Citation2020), who suggested that leadership and management training improve leaders’ knowledge and skills, that they can use to apply different leadership styles which are appropriate and practical for different situations.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

This study aimed to determine the leadership styles used by farmer organizations in Uganda, the differences in the characteristics of farmer organizations across styles, and the factors that influence such styles. While the principles of leadership and leadership styles have been extensively examined, the leadership styles used by farmer organizations in Uganda, as well as the factors that drive them, have received less attention. Due to leadership issues, farmer organizations in Uganda continue to struggle with sustainability. Therefore, analyzing these elements contributes significantly to the understanding of the leadership styles used by farmer organizations in Uganda, as well as the factors that influence the styles. According to the findings, most farmer organizations in Uganda employ both democratic and autocratic leadership approaches. The findings also show that farmer organizations differed in the following areas across the two leadership styles: savings and loan schemes, leadership passion, farm management training, leadership and management training, leaders’ expertise, and leadership committee size. The logit regression results showed that the savings scheme, number of organizational departments, leadership passion, usage of market outlets, total expenditures incurred, and leadership and management training influenced the use of both democratic and autocratic leadership styles. However, committee size, total income collected, and value-addition training influenced the use of a solely democratic leadership style. To achieve efficiency and effectiveness, we advocate that farmer organizations continue employing both democratic and autocratic leadership approaches rather than just a democratic approach. While the democratic approach improves organizational members’ innovation, well-being, skills, and knowledge, the autocratic approach protects organizational resources and products, keeps members on track, and directs all ideas generated by members towards the achievement of the intended goals. Government and other development partners working with farmer organizations may increase the number of leadership and management trainings available, to improve the leadership abilities of farmer organization leaders.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a larger study funded by the CESAAM project at Egerton University, supported by the World Bank, for which the authors are grateful. Great thanks to the Uganda National Farmers Federation, especially Madam Ayebare Prudence, for connecting the researcher to the District Farmer Associations, from where the farmer organizations were identified. To all the leaders of farmer organizations interviewed, thank you for your time and cooperation. Great thanks to Karani Charles, for the time invested in proofreading this work.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this study.

Data availability statement

Data sharing may not be applicable to this specific article as the manuscript is part of a larger study. Data will be shared later once all the work has been published.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nangobi Racheal

Ms. Nangobi Racheal is a doctoral student at Egerton University pursuing a Ph.D. in Agribusiness Management. She researched about Institutional and Management Factors Influencing Sustainability of Farmer Organizations in Uganda. Racheal also works as an assistant lecturer with the Faculty of Agriculture and Environment of Gulu University.

Mshenga Patience Mlongo

Mshenga Patience Mlongo is a Professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness Management, and the Dean of Faculty of Agriculture of Egerton University, Kenya.

Mugonola Basil

Mugonola Basil is an Assoc. Professor in the Department of Rural Development and Agribusiness in the Faculty of Agriculture and Environment of Gulu University, Uganda.

References

- Abraham, M., & Pingali, P. (2020). Transforming smallholder agriculture to achieve the SDGs. In S. Gomez y Paloma, L. Riesgo, & K. Louhichi (Eds.), The role of smallholder farms in food and nutrition security (pp. 1–17). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42148-9_9

- Achdiyat, D. G. (2018). Relationship between leadership of the board with the effectiveness of farmer organisation. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(7), 573–582. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i7/4400

- Adong, A., Mwaura, F., & Okoboi, G. (2013). What factors determine membership to farmer groups in Uganda? Evidence from the Uganda census of agriculture 2008/9. Journal of Sustainable Development, 6(4), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v6n4p37

- Ahmed, F. Z., Schwab, D., & Werker, E. (2020). The political transfer problem: How cross-border financial windfalls affect democracy and civil war. Journal of Comparative Economics, 49(2), 313–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2020.10.004

- Aldoshan, K. (2016). Leadership styles promote teamwork. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 5(06), 1–4.

- Alston, J. M., & Pardey, P. G. (2014). Agriculture in the global economy. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(1), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.1.121

- Ampaire, E. L., Machethe, C. L., & Birachi, E. (2013). The role of rural producer organizations in enhancing market participation of smallholder farmers in Uganda: Enabling and disabling factors. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 8(11), 963–970. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR12.1732

- Bans-Akutey, A. (2021). The path-goal theory of leadership. Academia Letters, 748, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL748

- Barungi, M., Guloba, M., & Adong, A. (2015). Uganda’s agricultural extension systems: How appropriate is the Single Spine Structure? (Vol. 16). EPRC Research Report.

- Bentzen, J. S., Kaarsen, N., & Wingender, A. M. (2017). Irrigation and autocracy. Journal of the European Economic Association, 15(1), 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeea.12173

- Birner, R., Cohen, M. J., Ilukor, J., Muhumuza, T., Schindler, K., & Mulligan, S. (2011). Rebuilding agricultural livelihoods in post-conflict situations: What are the governance challenges? The case of Northern Uganda. USSP Working Paper, 07. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3902463.

- Bizikova, L., Nkonya, E., Minah, M., Hanisch, M., Turaga, R. M. R., Speranza, C. I., Karthikeyan, M., Tang, L., Ghezzi-Kopel, K., Kelly, J., Celestin, A. C., & Timmers, B. (2020). A scoping review of the contributions of farmers’ organizations to smallholder agriculture. Nature Food, 1(10), 620–630. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-00164-x

- Clinton, B. N. (2015). Incorporating democratic leadership for career center instructors and staff: An action research study [Doctoral dissertation]. Capella University.

- Cochran, W. G. (1963). Sampling techniques (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Cosh, A.,Fu, X., &Hughes, A. (2012). Organisation structure and innovation performance in different environments. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9304-5

- Crosby, G. (2021). Lewin’s democratic style of situational leadership: A fresh look at a powerful OD model. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 57(3), 398–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886320979810

- Decuypere, A., & Schaufeli, W. (2020). Leadership and work engagement: Exploring explanatory mechanisms. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift für Personalforschung, 34(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002219892197

- Del Hoyo, L. V., Isabel, M. P. M., & Vega, F. J. M. (2011). Logistic regression models for human-caused wildfire risk estimation: Analysing the effect of the spatial accuracy in fire occurrence data. European Journal of Forest Research, 130(6), 983–996.

- Del Maestro Filho, A., Dias, D. V., de Almeida Borges, K. M., & Maduro, M. R. (2015). Organizational modernization and innovative training practices: A relational model of study. Business Management Dynamics, 4(12), 1.

- Doraiswamy, I. R. (2012). Servant or leader? Who will stand up please. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(9), 178–182.

- Durmus, S. C., & Kirca, K. (2020). Leadership styles in nursing. In S. C. Durmus (Ed.), Nursing – New perspectives. Intechopen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.89679

- Eken, İ., Özturgut, O., & Craven, A. E. (2014). Leadership styles and cultural intelligence. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics, 11(3), 154.

- Ellitan, L. (2022). Assistance for strengthening farmer group leadership 3g-ago village todo, satar mese north district manggarai-nusa tenggara timur. Jurnal Pengabdian Masyarakat, 1(2), 260–266.

- Elmaghrabi, M. E. (2021). CSR committee attributes and CSR performance: UK evidence. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 21(5), 892–919. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-01-2020-0036

- Fan, S., & Rue, C. (2020). The role of smallholder farms in a changing world. In S. Gomez y Paloma, L. Riesgo, & K. Louhichi (Eds.), The role of smallholder farms in food and nutrition security (pp. 13–28). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42148-9_2

- FAOSTAT. (2013). A database of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Retrieved January 2013 from http://faostat.fao.org.

- Fawcett, J. (2015). Invisible nursing research: Thoughts about mixed methods research and nursing practice. Nursing Science Quarterly, 28(2), 167–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318415571604

- Frank, J., & Penrose Buckley, C. (2012). Small-scale farmers and climate change. How can farmer organizations and Fairtrade Build the Adaptive Capacity of Smallholders? IIED.

- Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2014). Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: A new data set. Perspectives on Politics, 12(2), 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592714000851

- Goleman, D. (2017). Leadership that gets results. In Leadership perspectives (pp. 85–96). Routledge.

- Golensky, M., & Hager, M. (2020). Strategic leadership and management in nonprofit organizations: Theory and practice. Oxford University Press.

- Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1969). Life cycle theory of leadership. Training and Development Journal, 23(2), 26–34. Human resources (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Ho, V. T., & Astakhova, M. N. (2020). The passion bug: How and when do leaders inspire work passion? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(5), 424–444. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2443

- Jain, A., & Chaudhary, S. (2014). Leadership styles of bank managers in nationalized commercial banks of India. PURUSHARTHA-A journal of management. Ethics and Spirituality, 7(1), 98–105.

- Jouber, H. (2020). Is the effect of board diversity on CSR diverse? New insights from one-tier vs two-tier corporate board models. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 21(1), 23–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-07-2020-0277

- Khan, M. S., Khan, I., Qureshi, Q. A., Ismail, H. M., Rauf, H., Latif, A., & Tahir, M. (2015). The styles of leadership: A critical review. Public Policy and Administration Research, 5(3), 87–92.

- Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2003). The leadership practices inventory (LPI): Self instrument (Vol. 52). John Wiley & Sons.

- Latynskiy, E., & Berger, T. (2016). Networks of rural producer organizations in Uganda: What can be done to make them work better? World Development, 78, 572–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.014

- Lin, T., Ko, A. P., Than, M. M., Catacutan, D. C., Finlayson, R. F., & Isaac, M. E. (2021). Farmer social networks: The role of advice ties and organizational leadership in agroforestry adoption. Plos One, 16(8), e0255987. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255987

- Martin, J. (2015). Transformational and transactional leadership: An exploration of gender, experience, and institution type. portal. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 15(2), 331–351. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2015.0015

- Mihai, L. S. (2015). The particularities of leadership styles among Dutch small and medium business owners. Annals of ‘Constantin Brancusi’ University of Targu-Jiu. Economy Series (6).

- Minah, M. (2021). What is the influence of government programs on farmer organizations and their impacts? Evidence from Zambia. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 93(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12316

- Miriti, O. M. (2012). Factors influencing the effectiveness of farmer groups in the cereals market: The case of Imenti North District, Kenya [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Nairobi.

- Mohammad, I., Chowdhury, S. R., & Sanju, N. L. (2017). Leadership styles followed in banking industry of Bangladesh: A case study on some selected banks and financial institutions. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Business, 3(3), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtab.20170303.11

- Mutale, W., Vardoy-Mutale, A. T., Kachemba, A., Mukendi, R., Clarke, K., & Mulenga, D. (2017). Leadership and management training as a catalyst to health system strengthening in low-income settings: Evidence from implementation of the Zambia Management and Leadership course for district health managers in Zambia. Plos One, 12(7), e0174536. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174536

- Mutmainah, R. (2014). The leadership role of farmer groups and effectiveness of the farmers empowerment. Sodality: Jurnal Sosiologi Pedesaan, 2(3), 182–199.

- Mwaura, F. (2014). Effect of farmer group membership on agricultural technology adoption and crop productivity in Uganda. African Crop Science Journal, 22, 917–927.

- Okeke, V. I. (2019). Leadership style and SMEs sustainability in Nigeria: A multiple case study [Doctoral dissertation]. Walden University.

- Omotesho, K. F., Akinrinde, A. F., Laaro, K. A., & Olugbeja, J. O. (2019). An assessment of leadership training needs of executive members of farmer-groups in Oyo State, Nigeria. Agricultura Tropica et Subtropica, 52(3–4), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.2478/ats-2019-0013

- Owusu, F. Y., Sseguya, H., Mazur, R. E., & Njuki, J. M. (2013). Determinants of participation and leadership in food security organizations in Southeast Uganda: Implications for development programs and policies. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 8(1), 77.

- Peterson, S. J., Galvin, B. M., & Lange, D. (2012). CEO servant leadership: Exploring executive characteristics and firm performance. Personnel Psychology, 65(3), 565–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2012.01253.x

- Promme, P., Kuwornu, J. K., Jourdain, D., Shivakoti, G. P., & Soni, P. (2017). Factors influencing rubber marketing by smallholder farmers in Thailand. Development in Practice, 27(6), 865–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2017.1340930

- Santos, J. L. G. D., Erdmann, A. L., Meirelles, B. H. S., Lanzoni, G. M. D. M., Cunha, V. P. D., & Ross, R. (2017). Integrating quantitative and qualitative data in mixed methods research. Texto and Contexto-Enfermagem, 26(3), 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1590/010407072017001590016

- Seidman, G., Pascal, L., & McDonough, J. (2020). What benefits do healthcare organisations receive from leadership and management development programmes? A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Leader, 4(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1136/leader-2019-000141

- Sinyolo, S., & Mudhara, M. (2018). Farmer groups and inorganic fertiliser use among smallholders in rural South Africa. South African Journal of Science, 114(5/6), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2018/20170083

- Sirén, C., Patel, P. C., & Wincent, J. (2016). How do harmonious passion and obsessive passion moderate the influence of a CEO’s change-oriented leadership on company performance? The Leadership Quarterly, 27(4), 653–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.03.002

- Smith, P. O. (2015). Leadership in academic health centers: Transactional and transformational leadership. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 22(4), 228–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-015-9441-8

- Srivastava, P. C. (2016). Leadership styles in western and eastern societies and its relation with organizational performance. Pranjana. The Journal of Management Awareness, 19(1), 69–76.

- Stempel, C. R., Rigotti, T., & Mohr, G. (2015). Think transformational leadership–Think female? Leadership, 11(3), 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715015590468

- Suvedi, M., Ghimire, R., & Kaplowitz, M. (2017). Farmers’ participation in extension programs and technology adoption in rural Nepal: A logistic regression analysis. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 23(4), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2017.1323653

- Tallam, S. J., Tanui, J. K., Muller, A. J., Mutsotso, B. M., & Mowo, J. G. (2016). The influence of organizational arrangements on effectiveness of collective action: Findings from a study of farmer organizations in the East African Highlands. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, 8(8), 151–165.

- Thompson, G., & Glasø, L. (2015). Situational leadership theory: A test from three perspectives. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 36(5), 527–544. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-10-2013-0130

- Todorova, T., & Vasilev, A. (2017). Some transaction cost effects of authoritarian management. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 24(3), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13571516.2017.1322258

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Uganda census of agriculture 2008/09, Kampala, Uganda. Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

- Vignesh, M. (2020). Decision making using Vroom-Yetton-Jago model with a practical application. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology, 8(10), 330–337. https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2020.31876

- Waller, J. L., & Johnson, M. (2013). Chi-Square and T-Tests using SAS®: performance and interpretation. Retrieved January 3, 2014, from https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings13/430-2013.pdf

- Wedig, K., & Wiegratz, J. (2018). Neoliberalism and the revival of agricultural cooperatives: The case of the coffee sector in Uganda. Journal of Agrarian Change, 18(2), 348–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12221

- Woodhill, J., Hasnain, S., & Griffith, A. (2020). Farmers and food systems: What future for small-scale agriculture. Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford. https://www.foresight4food.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Farming-food-WEB.pdf

- Wouterse, F., & Francesconi, G. N. (2016). Organizational health and performance. An empirical assessment of smallholder producer organizations in Africa. Journal on Chain and Network Science, 16(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.3920/JCNS2016.x002

Appendix A:

Ethical approval