Abstract

The existence of natural resources has a significant impact on state revenue, but it is also a criminogenic factor for crime. The exploration stage triggers violations not only of permits but also environmental damage due to the use of toxic substances, which occurs in two types of criminal acts. This research analyzes the typology of illegal mining crime and its enforcement model. Law No. 32/2009, Law No. 3/2020, as the primary legal source, with a case approach. This article argues that illegal typology is not only based on licensing but can be identified based on the mining area. Understanding the concept of illicit typology mining makes it easier for law enforcement officials to parse all elements of crime in a series of illegal mining. This article claims that illegal mining enforcement administrative prospects prioritize. The enforcement model changed based on the mining business area because this factor will distinguish the use of ecology as an element of applying criminal sanctions.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Illegal mining is a severe problem for countries with natural resources. One of the impacts of illegal mining is environmental damage. As a result, it is critical to pay close attention to the criminal law enforcement mechanism. This negative impact should not be overlooked because environmental damage can be irreversible. One way to improve the understanding of law enforcement institutions in handling illegal mining is through the approach of understanding mining area-based typology. The application of illegal mining typology based on the area starts from the investigation stage and is then outlined in the public prosecutor’s indictment; then, according to some, this approach reflects the presence of ecological justice in the criminal justice system.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Unauthorized mineral and coal mining occurs in several countries, such as Peru, India, Nigeria, and Indonesia (Lahiri-Dutt, Citation2014). Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources released that this crime occurred in 2700 locations. There are classified into two elements of natural resources: coal in 96 locations and minerals in 2645 locations spread across Indonesia (Esdm, Citation2022).

The rise of illegal mining crimes in Indonesia has multi-sectoral impacts, such as economic, environmental, and social (Resosudarmo et al., Citation2009). The economic impact is that the state suffers losses because the mineral and coal sector is one of the primary commodities that the government relies on in development. Decreased soil quality (environment) and reduced animal populations and habitats as an environmental impact. Meanwhile, indirect social impacts have the potential for horizontal conflict in the community and are dangerous for criminals because the equipment used generally does not meet standards.

As a means and source of human life, the environment should protected from any crime, including the impact of illegal mining. Protection of non-humans is a form of human behavior in realizing ecological justice. Such behavior will help future generations to enjoy a healthy environment (Stefanie & Stefan, Citation2012). Non-human factors, as one of the victims of illegal mining, need special attention. Efforts to exploit natural resources are towards the human center-oriented, and this is the anthropocentrism perspective. Nature is valuable as long as it is beneficial to humans, so that the risk to the utilization of human needs, nature can be sacrificed (Des Jardins, Citation2012).

As one of the mechanisms and processes in law enforcement, the criminal justice system becomes the central point in realizing certainty, justice, and benefit. The operation of the law will have an impact on the judge’s decision. Therefore, the components of the criminal justice system should work by the organizational order of each law enforcement institution (Crespo, Citation2016).

They are conceptualizing crime in some ways. The most common way people see crime is as a harmful act that breaks the law. However, many criminologists take a more complex view, seeing crime as breaking the law and other acts that cause harm. Typologies can also facilitate crime prevention or corrections efforts, the success of which depends on accurately identifying and addressing the specific problems underlying different types of offending behavior (Welsh et al., Citation2018).

A typology of crime and criminal behavior is a theoretical framework that can be practically applied to organize, classify, and understand various unlawful behaviors. A typology is a managed theory theoretically, clinically, or empirically constructed by listing types of crimes based on a particular theoretical framework. Criminal typologies are theoretical frameworks that can be practically applied to organize, classify, and understand a wide range of unlawful behavior. Typologies provide information for making decisions, policies, practices, and laws (Helfgott & Meloy, Citation2013).

Criminal typologies combine theory and practice by classifying criminal behavior as an organizing framework that identifies offending behavior in a way that general theories cannot. Crime typologies play a particular role in law enforcement, judicial, and correctional responses to types of offenders and offending situations.

Crime typologies are constructed in a variety of ways. Piers Beirne and Messerschmidt use a sociological typology by combining crimes typically defined in legal codes and crimes and social harms outside the law that have received much attention in the sociological and criminological literature (Messerschmidt, Citation2015). One of the most severe types of crime is environmental crime, as the impact of this type of crime is multi-faceted. Environmental crimes include several primary categories: wildlife crime, illegal mining, pollution crime, illegal fishing, and illegal logging. All of them violate environmental laws and can cause significant damage not only to the environment but also to human health.

The imposition of sanctions on offenders is an important idea that needs to be addressed in the criminal justice system in terms of the rule of law and the perpetrator’s or victim’s factors. (Jacobs, Citation2013). Criminal law recognizes responsibility for fault and strict liability, but these two concepts are mirror images of each other (Coleman, Citation1992). However, applying this criminal responsibility has generated upheaval, particularly in judging perpetrators’ guilt of unlawful mining violations. This responsibility is impacted by the growth of perspectives on nature’s existence as part of living beings with the same rights as humans (Zwart, Citation2014).

Several scholars have conducted several environmental crime studies. First, Espin and Perz (Citation2021) tend to analyze the effectiveness of environmental law enforcement using two approaches, namely the sanctions approach and the compliance or cooperation approach, which causes monolithic environmental law enforcement. Secondly, the results of Ali and Setiawan (Citation2023) research did not further mention the application of sanctions for perpetrators, even though the existence of sanctions has a particular portion for the realization of justice proportionally. Third, the research of Ali et al. (Citation2022) investigated the existence of environmental degradation as a criminal violation. One component of criminal aggravation might be applied to criminals to safeguard the environment. The quantity of the violation includes environmental damage as an aggravating factor.

In light of various literature sources, research needs to address the enforcement of illegal mining based on typology. Consequently, this article endeavors to analyze the criminal justice system’s mechanisms in enforcing illegal mining laws based on the typological identification of mining regions. The research aims to address two fundamental issues. Firstly, it seeks to explore how the category of illegal mining can be construed as a severe offense. Secondly, it aims to investigate how the enforcement model for illegal mining contributes to realizing ecological justice within the criminal justice system.

2. Methodology

A comprehensive review of pertinent and prior literature is a pivotal feature in any academic research endeavor. This literature review serves the crucial purpose of establishing a robust foundation to enhance the comprehension and focus of this research. Furthermore, developing theoretical frameworks and exploring findings from previous research studies can significantly enrich the current study’s depth of understanding regarding concepts delineated in earlier scholarly works. Hence, through this literature review, the primary objectives are to identify knowledge gaps and underscore the urgency and relevance of the ongoing research.

The critical legal resources used in this study are two legislative laws on environmental protection and management: Law No. 4 of 2009 in conjunction with Law No. 3 of 2020 and Law No. 32 of 2009. The legal materials were gathered as legislative rules from the peraturan.bpk.go.id website, which assists researchers by giving access to current and revised regulatory data. The approach used as supplemental research materials involves the classification of broad typologies of criminal activities and typologies particular to illicit mining. In addition, two cases with decision numbers 147/Pid.Sus/2022/PN.Tjs and 81/Pid.B-LH/2020/PN.Kba are incorporated as unique case methods optained from directory of judgments, Supreme Court of Indonesia.

The legislative approach analyzes the distinctions between offenses related to illegal mining and environmental harm. This method categorizes the various forms of illegal mining that result in environmental damage. Subsequently, the typology of illegal mining is applied to determine the orientation and urgency of ecological justice. Meanwhile, the case approach is analyzed to identify models for enforcing illegal mining regulations. Thus, alternative models for the enforcement of illegal mining that are oriented towards ecological values within the criminal justice system can be identified through these three approaches.

3. Results

A comprehensive understanding of the typologies of crimes is essential for identifying criminal activities and determining the legal instruments that can be employed in the criminal justice process. Law enforcement authorities perceive illegal mining primarily through the lens of permitting, precisely the administrative permits used as legal instruments to ensnare illegal mining perpetrators.

The typology of illegal mining can be identified within the realms of mineral and coal mining exploration areas. This study posits that mineral and coal mining regions can be classified into two categories: illegal mining within and outside mining areas. Each typology carries implications for applying the law and ultimately leads to sanctions against criminal offenders. In some instances, ecological justice can be achieved when instruments supporting illegal mining are meticulously scrutinized and presented by investigators then incorporated into charges. Procedurally, when environmental damage is recognized as one of the elements of wrongdoing, it can be treated as a standalone criminal offense alongside the core crime of illegal mining. Indirectly, this process accommodates ecological justice values within the criminal justice system.

To introduce ecological justice into the criminal justice system, investigators at the forefront of law enforcement must conduct thorough and diligent investigations. Sectoral egoism should be avoided during the investigative phase, as elements of environmental harm and loss can be unearthed through the engagement of experts, such as civil servants (PPNS), the Department of Energy and Mineral Resources, and the Environmental Agency, who can provide testimony to support the nature of the criminal offense.

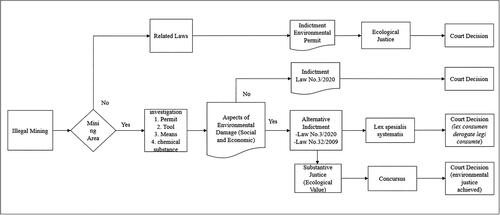

The enforcement of unpermitted mineral and coal mining from the perspective of permits does not inherently address the impact of illegal mining. Therefore, an alternative model that incorporates consequences such as environmental damage as an inseparable part of the criminal justice process is needed. To this end, this study proposes a new model for the enforcement of illegal mining from the perspective of mining regions, which introduces factors of environmental damage and loss as a basis for emphasizing prosecution against illegal mining perpetrators. For a more straightforward depiction, refer to .

Four distinct decision models for illegal mining are based on their respective characteristics. The enforcement method for illegal Mining based on mining regions can be categorized as follows:

Within Mining Areas. The prevailing concept of law enforcement against illegal mining within mining areas has traditionally focused on permits. However, illegal mining operations often involve heavy machinery and chemical substances, posing potential environmental hazards and socio-economic losses. This concept can give rise to three decision models:

Decisions are solely based on Law No. 3/2020.

Court rulings following the qualification of charges under Law No. 3/2020 and Law No. 32/2009 using the systematic lex specialis approach.

Court decisions in applying criminal charges based on the concursus realis indictment.

Outside Mining Areas. Court decisions regarding illegal mining outside mining areas utilize the lex specialis derogate legi general principle. Implicitly, single criminal acts and multiple criminal acts can be differentiated. First, offenders can be categorized as perpetrators of a single offense or multiple offenses, referred to as ‘single-crime offenders’ or ‘multiple-crime offenders.’ Second, these categories of offenders can be either ‘first-time offenders’ or ‘repeat offenders.’ The distinction between these two categories of violators is of great significance.

In deciding more specificity, the notion of lex specialist derogates legi general approached in two ways: logically (logische specialties) and systematically (systematische specialties). The dominating act can be used as an element of a person’s culpability for a criminal act under the systematic lex specialis principle, founded on the premise of lex consume derogate legi consumte, which indicates that one law supersedes another (Hiariej, Citation2021). Given that the features contained in Article 89 of Law 18/2013 contain, control, and accommodate the mining act in protected forest areas, there are many reasons why Law 18/2013 should applied to the matter at hand.

Nevertheless, the severity of punishment will largely depend on the number of violations committed (single crime vs. multiple offenses) and the offender’s criminal record (first-time offender vs. repeat offender). The difference between a ‘single crime’ and a ‘multi-offender’ is often straightforward. A single-crime offender commits a single act constituting a single violation, whereas a multi-offender engages in multiple violations, which are a consequence of several actions. Another distinction depends on (the absence of) a previous criminal record, presented in .

Table 1. Four types of offenders.

4. Discussion

In order to comprehend the typology of illegal mining crimes, it is crucial to understand the concept and typology of environmental crimes.

4.1. Typology of Environmental Crimes

Within environmental crimes, victimization often takes on a serious dimension. Because there are individual victims who suffer significant harm but rather because these crimes impact many individuals and the environment. Individual victims may only experience minimal losses, but the cumulative effects on society and the environment can be substantial.

In environmental crimes, the harm caused is not always immediately apparent, and its consequences can be widespread and enduring. These crimes often involve the degradation of ecosystems, pollution, or illegal resource extraction, all of which can lead to long-term damage to the environment and, subsequently, to the well-being of the communities dependent on these ecosystems.

Understanding the typology of environmental crimes is essential as it provides insights into the diverse ways these offenses can manifest, allowing for a more comprehensive approach to addressing and preventing them. Moreover, recognizing such crimes’ broader societal and environmental impacts underscores their significance and the need for effective enforcement and legal measures.

The typology of environmental crimes can vary widely, encompassing illegal logging, wildlife trafficking, air and water pollution, hazardous waste disposal, and, as in the context of this study, illegal mining. Each of these typologies presents unique challenges and requires tailored legal responses to mitigate their harmful effects on individuals and the environment.

In the case of illegal mining, understanding its typology is critical not only for law enforcement and the criminal justice system but also for policymakers and environmental agencies seeking to develop more robust strategies for combatting this form of environmental crime. This comprehension provides a foundation for crafting legislation and regulations that address the nuances of illegal mining practices and their environmental repercussions.

Environmental crimes can be categorized into three forms: violations related to permits, violations occurring outside regulatory frameworks, and actions conducted illegally, regardless of statutory provisions (Uhlmann, Citation2009).

Permit-Related Violations: This category encompasses crimes that involve the breach of permits or licenses granted by regulatory authorities for certain activities with environmental implications. Violations in this context typically occur when individuals or entities deviate from the terms and conditions stipulated in their permits or engage in activities beyond the scope of their authorization.

Violations Outside Regulatory Frameworks: Environmental crimes transgress established legal frameworks or regulations. Such violations often occur when individuals or organizations undertake activities not covered by existing environmental laws or regulations or operate in areas where regulatory oversight could be more effective.

Illegal Actions Unrelated to Statutory Provisions: This category includes environmental crimes committed entirely outside the purview of legal provisions and regulations. Offenders engaging in such activities do so clandestinely and unlawfully, disregarding any legal constraints. Illegal mining, for example, falls into this category when it occurs without the requisite permits and authorization and is carried out covertly to avoid detection and prosecution.

Understanding these three forms of environmental crimes is essential for crafting effective legal and regulatory responses. Differentiating between these categories allows authorities to tailor enforcement strategies to address the specific challenges posed by each type of offense. Additionally, it enables policymakers and law enforcement agencies to develop targeted interventions to prevent and combat environmental crimes while ensuring the protection of ecosystems and the well-being of affected communities (Gibbs et al., Citation2010).

Environmental crimes can be classified based on their nature. These offenses are divided into two categories based on their nature: those that apply specifically and those that apply generally. We can categorize crimes according to the type of media affected. Dumping, for example, can cause long-term damage to soil, water layers, and air quality; provides a more detailed explanation of this classification.

Table 2. Typology of environmental crimes.

On the other hand, crimes related to the environment and natural resources can also divided into primary and secondary crimes. Primary crimes result directly from the pollution and destruction of natural resource lands. Crimes such as water pollution and burning forests and grasslands are one type of crime that is as old as any other. Nevertheless, secondary crimes, which are often environmental crimes, are offenses that result from violations of environmental laws and regulations (Rabani et al., Citation2020).

Mining can also have widespread and long-term impacts, as with dumping. Picher Oklahoma/Tar Creek was once home to the world’s largest tin production mine, but the town was declared uninhabitable due to high pollution levels (Andrews & Masoner, Citation2011). The long-term impacts of pollution caused by irresponsible mining can devastate local economies and create unfavorable conditions for human life.

Responding to environmental crime and damage also requires learning from or attempting to understand previous mistakes and omissions and anticipating future risks and threats. In turn, it requires prevention or efforts to prevent or attempt to thwart environmental crime and damage before it occurs. (Brisman & South, Citation2019). How we respond to environmental crime and destruction is closely linked to how we learn about various environmental disasters or instances of habitual and ongoing environmental degradation and destruction. In contrast, some knowledge or understanding is based on our direct experience of environmental degradation and disasters.

4.2. Typology of crime in the mineral and coal sector

When referring to Law 3/2009 and Law 4/2020, management regulates the existence of mineral and coal mining licenses. This law also contains criminal sanctions for those who carry out mineral and coal mining business activities without a license. The basic policy concept contained in the law is administration, namely licensing. To understand the typology of illegal mining, the basis of this type of crime is unlicensed mining.

Unlicensed mineral and coal mining

Indonesia’s natural resources are abundant and diverse in the sea and land. The freedom to manage natural resources is often abused. They do not think about the environmental impact and are not even responsible, so the environment becomes a victim of exploitation activities. Parties that exploit natural resources and do not comply with laws and regulations include mining without a permit, known as illegal mining.

Illegal mining in Indonesia is also not new; illegal mining has often occurred in almost all areas with potential mineral resources. As with money, the activities of unlicensed miners are generally not environmentally friendly because they only conduct business activities for a limited period. A need for more awareness of environmental conservation and function causes this behavior (Nomani et al., Citation2021).

Illegal mining is a mining business carried out by individuals, groups of individuals, groups of people, or legal entities whose operations do not have permits from government agencies following applicable regulations (Soelistijo, Citation2012). Illegal mining can also be interpreted as producing minerals or coal by communities or companies without a license, not using mining principles, and harming the environment, economy, and society.

Licensing mechanisms and procedures for small-scale mining cause people to act instantly to get profitable benefits for the community. However, the business is detrimental to the state and the environment. The fact is that many small-scale miners still need to get a license from the government. The complicated issue related to this situation is that licenses are equated with companies, thus triggering illegal mining activities by the community (Prianto et al., Citation2019). In addition, the concept and mechanism of community mining licensing still need to be solved due to the lack of commitment of local governments in regulating and realizing community mining areas. The actions included in this classification are a. mineral and coal mining without IUP, IPR, and IUPK, b. holders of IUP, UPK, IPR, or SIPB submitting incorrect or false reports, and c. Exploration without IUP or IUPK.

These three types of licenses are the primary basis for managing and prosecuting this type of crime. Based on Article 158 of Law 3/2020, the license is an act classified as unlicensed mining; therefore, the act can be punished.

Misuse of Mineral and Coal Mining Licences

Misuse of mining licenses is maladministration, resulting in a violation of the law (Haris et al., Citation2023). Prior to the transfer of control of mining area management, it was not uncommon for this element to be one form of violation of the mineral and coal mining business along with the proportionality of the division of authority between the central government, provincial and regency/city regions following the Local Government Law. Article 165 of Law 4/2009 states that every person who issues an IUP, IPR, or IUPK contrary to the law and abuses his authority is subject to criminal sanctions in the form of imprisonment for a maximum of two years and a maximum fine of Rp. 200,000,000, - (two hundred million rupiah).

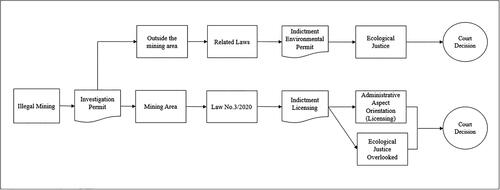

4.3. Law enforcement of illegal mining based on the existence of licenses

Based on the typology of illegal mining as described, the existence of illegal mining enforcement in realising ecological value uses the method as represented in .

Law enforcement of illegal mining based on the existence of licenses. Given that the mining concept is regulated in Law 13/2018 and Law 3/2020, to identify this type of crime in the Mining Area, then the license. Based on the norms regulated in Law 3/2020, criminal provisions are based on mining administration. Meanwhile, Law 13/2018 regulates the existence and function of forests and mining.

Every crime is not only in a single form but can also be considered a double act, so it requires the accuracy of law enforcement officials in finding and presenting elements that support both types of criminal acts. Suppose one of the criminal justice sub-systems does not unravel, especially at the investigation level. In that case, there is certainly no choice for the judge to explore the suitability of supporting elements that can determine with what law and how the perpetrator is sentenced because the judge is limited to the charges presented by the prosecutor.

As with environmental crimes, the mineral and coal mining sector often contains more than one type of criminal offense: different types of crimes and regulations. According to Angus Nurse, environmental crimes have a long-term and irreversible impact and potentially cause much broader social damage and death (Nurse, Citation2022). Future generations have a legal and moral right to protection from environmental threats and hazards (Weston, Citation2012).

Investigators should be more observant in exploring illegal mining because it is not uncommon for this type of crime to have one type of criminal act and multiple acts. Thus, all components of culpability of illegal mining criminals are stated in charges targeted toward concursus charges, particularly concursus realis. Four techniques have been taken concerning this type of indictment. The first approach uses the most severe criminal threat strategy accompanied by criminal aggravation. Secondly, each act is considered alone as a criminal act but is limited or commingled. Third, each criminal act is assessed independently with pure cumulative and without reduction of punishment, as long as the punishment imposed is balanced with the loss caused by the criminal act. Fourth, a pure punishment system without aggravation or reduction of punishment (Faisal & Rustamaji, Citation2020).

Dealing with multiple offenses is, of course, different from single offenses, as is the treatment of offenders with multiple offenses. An offender who commits multiple offenses (a continuing offense) will receive a lighter (perhaps much shorter) sentence in a single sentencing occasion than if he or she were sentenced for the same offense on two or more separate sentencing occasions. Bottoms suggests a mercy-based approach to sentencing multiple offenders, designed to avoid overly severe total sentences. Thomas believes avoiding ‘crushing’ punishment is part of the court’s rationale for the totality principle (Zedner & Roberts, Citation2012).

In terms of sentencing objectives, the approach to the totality principle takes precedence over overall proportionality. It means that where there is a choice between two applications of offense proportionality to produce cumulative sentences, restraint in detention should be applied, and overall proportionality should take precedence. However, it is possible to use the totality principle for offenses committed by more than one different offender.

The advantage of using the principle of totality for multiple offenses is that quantitatively, the criminal sanction imposed on the perpetrator is lighter than if tried consecutively. If the judge imposes two sentences for two criminal offenses consecutively, at least one of the other offenses must reduced. Concurrent sentences are, therefore, more in line with the principles of proportionality than consecutive sentences, as concurrent sentences allow judges to impose custodial sentences proportionate to the individual offenses dealt with while also complying with the totality.

The principle of proportionality refers to two reasons. Firstly, it must be distinguished from the ancient notion of lex talionis that the harm an offender inflicts must be equal (in kind or degree) to the harm he does to his victim. Ashworth opposes this view, as it is up to each criminal justice system to determine the absolute level of punishment based on various local factors. Ashworth’s concern was not to ensure that offenders were sentenced to punishment equal to the harm they did to others but rather to ensure that the punishment they suffered was proportionate to the wrong they committed. Ashworth focuses on the relative treatment of offenders in the criminal justice system. Every offender should receive the same severe punishment as those who commit offenses of the same seriousness (the parity principle). It should be more severe for those who commit less serious offenses and less severe for those who commit more serious offenses (the rank order principle).

Secondly, Ashworth’s vital proportionality principle is not the idea that proportionality should be the only factor sentencing judges consider when determining the appropriate severity of punishment (Bagaric, Citation2000). Philosophers broadly agree that criminal punishment should be proportionate to the seriousness of the offense. However, this apparent consensus must be more superficial, masking significant disagreements beneath the surface. The proposed principle of proportionality differs in several different dimensions: The nature of the offense or offender determines the ‘seriousness’ of the offense and, thus, the relatum of proportionality, Whether punishment becomes disproportionate only if it is too severe or too light, and The principle can provide an absolute or merely comparative judgment (Berman, Citation2021).

The general formulation is that punishment should be proportionate to the gravity or seriousness of the offense. However, scholars propose a wide range of offenses or offender characteristics that should be punished proportionally. Many scholars focus on characteristics that might reasonably be considered internal to the offender, such as blameworthiness, culpability, guilt, or desertion. Other scholars focus on those external to the offender, i.e. what matters most in terms of proportionality is the harm caused by the offense. Others combine the two views, treating the seriousness of the offense for proportionality purposes as a usually undetermined function of culpability (or guilt) and harm. At the adjudicative level, judges cannot avoid the need to find a firm limit to harm as long as there is a real possibility of causing damage to the legal interests to be protected. Therefore, it is not crucial whether the harm is realized or not. Thus, a factual assessment of the concrete circumstances is required (Remmelink, Citation2003). Each of these components gives rise to its principle of proportionality such that the principle of proportionality in reproach states that the amount of reprimand an offender deserves should be a function of the culpability of the offense. At the same time, the principle of proportionality in strict treatment directs that the severity of the punishment deserved by an offender should be a function of the seriousness of the offense. On the other hand, the enforcement model of illegal mining measured based on priority regarding four models of criminalization based on harm to the environment: abstract harm, concrete harm, concrete loss, and severe environmental pollution (Ali & Setiawan, Citation2023).

4.4. Mineral and Coal Mining Crimes based on area

In simple terms, the typology of mineral and coal mining crimes in terms of the location of the mining business is divided into two categories: illegal mining in the mining area and illegal outside the mining area.

Illegal Mining in the Mining Area

This type of crime is one of the phenomena and problems that are difficult to solve. Many illegal mines are carried out by small communities with large numbers as if this existence is between presence and absence. This has an impact on state losses. In 2022, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources recorded state losses due to illegal mining in mining areas of Rp. 3.5 trillion (Indonesia, Citation2023). According to Redi, this component is used as a policy for the government to formalize illegal mining into a legitimate enterprise based on cost and benefit analysis to achieve community welfare (the highest happiness of the highest principle) (Redi, Citation2016).

This formalization represents a policy shift in the regulation of small-scale mining. The legalization process is conducted in six ways: development of a conducive and complete legislative environment, access to geological data, capital, equipment, capacity building, and activation of conversation among the players involved (Sugiarti et al., Citation2021).

In some contexts, informal access to land through ancestral connections is more legitimate in the eyes of local miners than formal mining permits. Thus, more than a mining license is needed to be attractive to local miners. The lack of understanding of the livelihood dimensions of illegal small-scale mining leads to the erroneous policy assumption that people operating in mines are enterprising business people rather than breadwinners. This suggests that an adequate and accurate understanding of grassroots conditions and views on formalization is critical to its success (Kumah, Citation2022).

Not illegal mining occurs in mining areas, and the average justice system enforcement process ignores ecological justice. One case supporting this type of crime is Court Decision Number 147/Pid.Sus/2022/PN Tjs.

The mine excavation process begins with locating the gold material with an excavator to determine the material line. The samples were collected for testing after being soaked in CN (cyanide) for 5-7 days. The carbon gold material is then moistened in the soaking tub, burned, and finally shot with a brandel/blemer, revealing raw gold material. The National Police Criminal Investigation Unit’s criminalistics laboratory test No. 1926/BMF/2022 revealed that the soil excavated and used as an examination sample contained 75.6472% silica (Si), 0.4200% silver (Ag), and 0.8234% gold (Au).

The prosecutor’s facts in the indictment do not explain the existence of the influence of CN Cyanide. Although the defendant’s material, CN Cyanide, as a mixture of sifting soil content and mining types, produces gold, it can harm humans and the environment (plants, animals, and soil) if not handled properly. The toxicity of free cyanide is exceptionally high (Majalis et al., Citation2022).

The use of CN Cyanide in this case can be classified as a delict causing abstract danger. According to Jan Remmelink, the public prosecutor merely needs to prove that the harmful behavior occurred. Because a particular legal object is genuinely threatened with danger/harm as a result of dangerous behavior, as defined by Article 429 sub 3 sir (Remmelink, Citation2003). As with the mineral and coal mining management concept, the aspects that take precedence are licensing, not environmental impact. It means that the investigation mechanism is identical to ignoring environmental justice as an impact of illegal mining. In fact, following its contents, the law is a manifestation of justice, including non-human (ecological) justice. The moral responsibility of humans towards non-human organisms is not only humanitarian. However, it includes the requirements of distributive justice despite the insurmountable resistance to the idea that only moral beings can properly receive such justice (Baxter, 2005).

The indictment submitted to the judge was restrictive, with no alternate usage of Article 98 paragraph (1) of Law 32/2009 that might fit cyanide’s purpose and impact. If law enforcement officers perform poorly, there will be no systematization in the criminal justice system. Because, under the concept of law, legal requirements are interpreted and can influence which of several feasible alternatives to make the decision (Sidharta, Citation2009). The indictment constrains the judge’s movement, and the law tends to be static; logocentrism is stiff (Faisal & Rustamaji Citation2020). On the other hand, judges have authority in the form of judicial discretion (Etcheverry Citation2018). This authority determines the option that will be examined based on legal rationale and belief that an encountered act can be blamed and then sentenced, or vice versa.

The judge noted the ‘large environmental damage caused by the defendant’s actions, which can be classified as large mining as well’ based on the verdict, particularly the aggravating sentence. However, this influence could have been more emphasized or investigated in the trial facts. Because it is tied to the defendant’s large-scale mining operation, there is the possibility of state losses and environmental problems relating to the dug area and CN Cyanide used in gold ore processing. According to this example, the criminal justice system has no synchronization and harmony, particularly in aligning law enforcement employees’ cultural perceptions (Muladi, Citation1995).

Illegal Mining outside the Mining Area

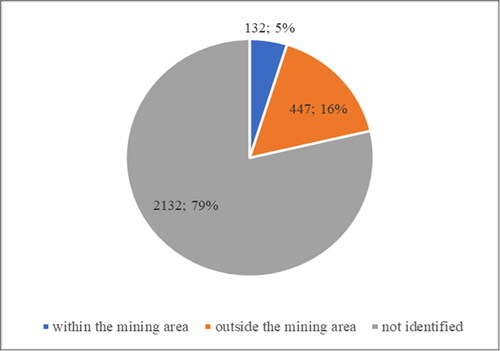

Illegal mining can not only be done in the mining area but also outside the mining area. Based on the Report of the Directorate General of Mineral and Coal of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, the location of illegal mining is spread as many as 2741, consisting of 477 outside the Mining Licence Area, 132 inside the Mining Business Licence Area, and the remaining 2132 are not identified (Dirjend Minerba, Citation2021). The percentage of illegal mining, presented in .

Figure 3. Percentage of illegal mining based on Mining Area.

Source: Annual report of Directorate General of Mineral and Coal, Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, Dirjend Minerba (Citation2021).

From the data on illegal mining in Indonesia, this type of crime can also occur outside the mining area. In this context, the criminal justice process is easier to apply ecological justice because other special regulations support this type of crime. One case that has applied ecological justice is Court Decision Number 81/Pid.B-LH/2020/PN Kba.

Azeman bin H. Maharan is the leader of a Tani Makmur Forest Farmer Group (Gapoktanhut) in Batu Beriga Village, Lubuk Besar Subdistrict, Central Bangka Regency. Activities involving ‘planting agarwood trees’ in protected forest areas resulted in: dredging and soil extraction holes with depths ranging from 2 to 7 meters, loss of top soil, sub soil, and natural vegetation.

The judge’s consideration in the case quo on the public prosecutor’s allegations, namely: Article 94 paragraph (1) letter a jo. Article 19 letter a and Article 89 paragraph (1) letter a jo. Article 17 paragraph (1) letter b of Law 18/2013, as well as Articles 98 and 99 paragraph (1) of Law 3/2009.

Of the two alternative charges presented by the public prosecutor, the judge’s decision tends to favor Article 89 paragraph (1) letter a jo. Article 17 paragraph (1) of Law 18/2013 by assessing the material act element ‘conducting mining activities in forest areas without a ministerial permit.’ The elements in the article relate to three things: every person intentionally carries out actions that result in exceeding ambient air quality standards, seawater quality standards, and standard criteria for environmental damage. The third element used as a parameter by the judge is the type of soil excavated by the perpetrator, namely color, level of weathering, texture, and excavation of three meters of soil. The indictment is addressed in the form of alternatives. However, considering that the basis of each indictment uses a particular law (lex specialis) based on the dynamic and limitative lex specialis principle, it needs to be degraded by determining the dominant act. The national legal system provides an ideal environment for applying the lex specialis principle, as it is an organized conception with a hierarchical, structured system, institutions, and an organized legal framework. Lex specialis has proven to be a valuable conflict resolution tool in the national legal order (Prud’homme 2007).

4.5. Environmental damage-based criminal law enforcement orientation

Mining can remain sustainable only if it follows the principles of ecological sustainability, economic and ecological vitality, economic vitality, and social equity at all stages of the mining life cycle. Mining becomes more environmentally friendly with measures such as reducing inputs and outputs, using sustainable equipment to reduce waste, using renewable energy resources that help save energy, and closing illegal mining.

Normatively, mineral and coal mining business arrangements have been accommodated in Article 124 paragraph (2) of Law 3/2020 with the concept of tiered licensing starting from the general investigation, exploration, feasibility study, construction, mining, processing, or refining, transportation and sales, and post-mining. The government makes administrative policies in such a way with the hope that the mining business is not only concerned with profit but also pays attention to environmental factors.

The government’s view aligns with the concept built and recognized by the anthropocentrism view of nature, where nature is only used as a tool in fulfilling human needs. The impact of mining management often results in environmental degradation, but this perspective is considered reasonable as long as the foundation of its purpose is to fulfill human needs. Hayward provides a fragmented definition of anthropocentrism: What is objected to under the heading of anthropocentrism in environmental ethics and ecological politics is a concern with human interest exclusion, or that expense, of the interest of other species (Kopnina et al., Citation2018).

All previous ethics have been founded on the concept that the individual is a member of a community of interconnected pieces. His instincts push him to compete and earn his place in that community, but his ethics push him to collaborate (apparently to make room for competition) (Paul & Baindur Citation2016). Leopold argues that land ethics expands the boundaries of a community to include soil, water, plants, and animals. Land ethics changes the role of Homo sapiens from conquerors of the land community to ordinary members and citizens. This implies respect for fellow members and also respect for the community as such (Leopold, Citation2008).

This state of affairs resulted in the emergence of the deep ecology Movement and will continue to grow regardless of what professional philosophers come up with. One of the leaders of this Movement is Arne Naess, who developed eight essential concepts: a) The flourishing of human and non-human life on Earth has inherent value. b) The richness and diversity of life forms are also valuable in themselves and contribute to the flourishing of human and non-human life on Earth. c) Humans have no right to reduce such richness and diversity except to fulfill their vital needs. d) The flourishing of human life and culture is compatible with a substantial reduction in human population. e) Based on the above, existing policies must be changed. Policy changes will affect the economy’s structure, technology, and fundamental ideology. f) The ideological change in question is primarily the appreciation of the quality of life (living in situations of inherent value) rather than adhering to an ever-higher standard of living, and g) Those who subscribe to the above points have a direct or indirect obligation to participate in efforts to implement the necessary changes (Naess, Citation2008).

The presence of law enforcers, both in terms of human resources and institutionally, is an essential component of success in implementing laws and regulations. The legislature can determine the success or failure of law enforcement implementation by establishing laws and regulations. At this policy level, the law serves to improve society. However, it is uncommon for the community to oppose the law’s rules, norms, and enforceability, putting law enforcers in an awkward position between implementing the applicable law with their power and being forceful (Raharjo, Citation2011). Indeed, law enforcement officers’ performance is frequently situational; for example, the same case is handled, but each law enforcement agency provides a different interpretation at the implementation level. Van Dorn justifies this by stating that law enforcement as a function holder in an organization is motivated by particular elements, such as disparities in interpretation amongst law enforcement agencies.

Professional behavior and attitudes significantly impact the pattern of system demands. So far, the legal system is nothing more than a conduit, a rope in our metaphor. Professional behaviors, on the other hand, have explanations. A judge will decide to fulfill the demands placed on him when it is in his best interests or when his peers or values demand it. However, such long-term remnants of social institutions indicate long-standing power and influence, and peer pressure is affected by who the peers are - for example, patterns of recruitment into the profession, a factor that is far from politically neutral. The complicated behavior of professionals, the internal legal culture, is thus not an autonomous development and is not an exception to the general thesis of society’s dominance over law (Teubner, Citation2022).

5. Conclussion

Based on the typology of crime, illegal mining impacts environmental damage. Illegal mining operations are limited to licensing, and the facilities and infrastructure used, such as toxic substances, can cause environmental damage. Thus, this type of crime is a double act because it fulfills the criminal elements in Law 3/2020 and Law 36/2009. This situation becomes problematic if the elements of each double criminal offense are not presented in the indictment. In the evidentiary process, the judge is limited to the indictment and the facts presented, which impacts the application of sanctions. Law enforcement officials can use an area-based typology of illegal mining in the criminal justice process, especially at the investigation stage, because the region’s consequences impact the rules that can be applied to the perpetrators of illegal mining.

Ecological justice is achieved in the criminal justice system if all components of illegal mining are detected during the inquiry and included in the indictment. This procedure allows judges to apply the law and impose sanctions on illegal mining perpetrators in totality and proportion.

The author recommends including all aspects of a series of illegal mining operations in the investigation and indictment processes. This type of crime has a multi-sectoral impact on achieving the same goal: realizing ecological justice in an integrated criminal justice system.

This research is limited to specific cases in two locations, namely in North Kalimantan and Bangka Belitung, so that further research can be expanded to the types of minerals and coal and conducted in several regions with different natural resources.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Directorate of Higher Education, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, and the Universitas Borneo Tarakan for allowing us to participate in the PTA scheme education program. We also thank the authors of books and journals. The references in the form of books and journals enrich the theories and findings that support this research.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interests or competing interests to declare.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arif Rohman

Arif Rohman is a doctoral student, at the Law Faculty, Universitas Sebelas Maret. He is an assistant professor at the Faculty of Law, Universitas Borneo Tarakan. This research was supervised by Hartiwiningsih focusing on environmental crimes and Muhammad Rustamaji focusing on criminal justice.

Hartiwiningsih

Hartiwiningsih is a professor of environmental criminal law at the Faculty of Law, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta. In order to support her career, several scientific works in the form of books and articles published in reputable international journal.

Muhammad Rustamaji

Muhammad Rustamaji is an associate professor at the Faculty of Law, Universitas Sebelas Maret. He is an expert in the field of criminal procedure law.

References

- Ali, M., & Setiawan, M. A. (2023). Penal proportionality in environmental legislation of Indonesia. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2009167. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.2009167

- Ali, M., Wahanisa, R., Barkhuizen, J., & Teeraphan, P. (2022). Protecting environment through criminal sanction aggravation. Journal of Indonesian Legal Studies, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.15294/jils.v7i1.54819

- Andrews, W. J., & Masoner, J. R. (2011). Changes in selected metals concentrations from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s in a stream draining the picher mining District of Oklahoma. The Open Environmental & Biological Monitoring Journal, 4(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.2174/1875040001104010036

- Audenaert, N. (2021). Prosecuting and punishing offenders for several offences in Belgium. In N. Audenaert & W. D. Bondt (Eds.), Prosecuting and punishing multi-offenders in the EU (pp. 21–53). Gompel & Svacina.

- Bagaric, M. (2000). Proportionality in sentencing: its justification, meaning and role. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 12(2), 143–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2000.12036187

- Berman, M. N. (2021). Proportionality, constraint, and culpability. Criminal Law and Philosophy, 15(3), 373–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-021-09589-2

- Brisman, A., & South, N. (2019). Green criminology and environmental crimes and harms. Sociology Compass, 13(1), e12650. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12650

- Clifford, M. (1998). Environmental crime: Enforcement, policy, and social responsibility. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Coleman, J. L. (1992). Risks and wrongs. Cambridge University Press.

- Crespo, A. M. (2016). Systemic facts: Toward institutional awareness in criminal courts. Harvard Law Reiew, 129(8), 2049–2117.

- Des Jardins, J. R. (2012). Environmental ethics: An introduction to environmental philosophy cengage learning (5 ed.). WADSWORTH Cengage Learning.

- Dirjend Minerba, E. (2021). Laporan Kinerja Ditjend Minerba. Kementerian Energi Sumber Daya Mineral.

- Esdm, D. M. (2022). Pertambangan Tanpa Izin Perlu Menjadi Perhatian Bersama. Jakarta: Kementerian ESDM Republik Indonesia. Retrieved from https://www.esdm.go.id/id/media-center/arsip-berita/pertambangan-tanpa-izin-perlu-menjadi-perhatian-bersama

- Espin, J., & Perz, S. (2021). Environmental crimes in extractive activities: Explanations for low enforcement effectiveness in the case of illegal gold mining in Madre de Dios, Peru. The Extractive Industries and Society, 8(1), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.12.009

- Etcheverry, J. B. (2018). Rule of law and judicial discretion: Their compatibility and reciprocal limitation. ARSP: Archiv für Rechts-und Sozialphilosophie/Archives for Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.18601/01229893.n38.01

- Faisal & Rustamaji, M. (2020). Hukum Pidana Umum. Thafamedia.

- Gibbs, C., Gore, M. L., McGarrell, E. F., & Rivers, L. (2010). Introducing conservation criminology: Towards interdisciplinary scholarship on environmental crimes and risks. British Journal of Criminology, 50(1), 124–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azp045

- Haris, O. K., Hidayat, S., Herman, S., Hendrawan, S. S., & Yahya, A. K. (2023). Pertanggungjawaban Pidana Penyalahgunaan IUP (Izin Usaha Pertambangan) yang Berimplikasi Kerusakan Hutan (Studi Kasus Putusan Nomor 181/Pid.B/LH/2022/PN.Unh.). Halu Oleo Legal Research, 5(1), 290–306. https://doi.org/10.33772/holresch.v5i1.240

- Helfgott, J., & Meloy, J. (2013). Criminal Psychology. Santa Barbara California: Praeger an imprint of ABC-CLIO LLC. Retrieved from http://site.ebrary.com/id/10695431.

- Hiariej, E. O. S. (2021). Asas Lex Specialis Systematis dan Hukum Pidana Pajak. Jurnal Penelitian Hukum De Jure, 21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.30641/dejure.2021.V21.1-12

- Indonesia, T. C. (2023). https://www.cnnindonesia.com. Retrieved from https://www.cnnindonesia.com: CNN Indonesia, https://www.cnnindonesia.com/ekonomi/20230321141404-85-927824/esdm-sebut-kerugian-negara-akibat-tambang-ilegal-tembus-rp35-t

- Jacobs, J. (2013). The liberal polity, criminal sanction, and civil society. Criminal Justice Ethics, 32(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/0731129X.2013.860730

- Kopnina, H., Washington, H., Taylor, B., & Piccolo, J. J. (2018). Anthropocentrism: More than Just a misunderstood problem. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 31(1), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-018-9711-1

- Kumah, R. (2022). Artisanal and small-scale mining formalization challenges in Ghana: Explaining grassroots perspectives. Resources Policy, 79, 102978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102978

- Lahiri-Dutt, K. (2016). The coal nation: Histories, ecologies and politics of coal in India. Routledge.

- Leopold, A. (2008). The ethics of the environment. (1 ed.). R. Attfield (Ed.) Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315239897

- Majalis, A. N.,Mohar, R. S.,Novitasari, Y., &Hardianti, A. (2022). Pengolahan Tailing Sianidasi Bijih Emas dengan Proses Oksidasi-Presipitasi. Jurnal Ilmu Lingkungan, 20(4), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.14710/jil.20.4.757-768

- Messerschmidt, P. B. (2015). Criminology: A sociological approach (6th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Muladi. (1995). Kapita Selekta Sistem Peradilan Pidana. Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro.

- Naess, A. (2008). The ecology of wisdom: Writings by Arne Naess. In A. Drengson, & B. Devall (Eds.). Counterpoint.

- Nomani, M., Osmani, A. R., Salahuddin, G., Tahreem, M., Khan, S. A., & Jasim, A. H. (2021). Environmental impact of rat-hole coal mines on the biodiversity of Meghalaya, India’. 1 Jan. 2021: 77–84. Asian Journal of Water, Environment and Pollution, 18(1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.3233/AJW210010

- Nurse, A. (2022). Contemporary perspectives on environmental enforcement. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 66(4), 327–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X20964037

- Paul, K. B., & Baindur, M, (2016). Leopold’s land ethic in the Sundarbans: A phenomenological approach. Environmental Ethics, 38(3), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics201638327

- Prianto, Y., Djaja, B., Sh, R., & Gazali, N. B. (2019). Penegakan Hukum Pertambangan Tanpa Izin Serta Dampaknya Terhadap Konservasi Fungsi Lingkungan Hidup. Bina Hukum Lingkungan, 4(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.24970/bhl.v4i1.80

- Rabani, H., Jalalian, A., & Pournouri, M. (2020). Typology of environmental crimes in Iran (case study: Crimes related to environmental pollution.) Anthropogenic Pollution, 4(2), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.22034/AP.2020.1903703.1067

- Raharjo, S. (2011). Penegakan Hukum: Suatu tinjauan Sosiologis. Genta Publishing.

- Rebovich, D. J. (1998). Environmental crime prosecution at the county level. In M. Clifford (Ed), Environmental crime: Enforcement, policy and social responsibility (pp. 205–228). Aspen Publishers.

- Redi, A. (2016). Dilema Penegakan Hukum Pertambangan Mineral dan Batubara Tanpa Izin pda Pertambangan Skala Kecil. Jurnal Rechtvinding: Media Pembinaan Hukum Nasional, 5(3), 399–420. https://doi.org/10.33331/rechtsvinding.v5i3.152

- Remmelink, J. (2003). Hukum Pidana: komentar atas pasal-pasal penting dari Kitab Undang-Udnang Hukum Pidana Belanda dan padanannya dalam Kitab Undang-Undang Hukum Pidana Indonesia. Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

- Resosudarmo, B. P., Resosudarmo, I. A., Sarosa, W., & Subiman, N. L. (2009). Socioeconomic conflicts in Indonesia’s mining industry. Washington, DC: The Henry L. Stimson Center. Retrieved from https://about.jstor.org/terms

- Sidharta, B. A. (2009). Refleksi tentang struktur ilmu hukum: sebuah penelitian tentang fundasi kefilsafatan dan sifat keilmuan ilmu. Mandar Maju.

- Soelistijo, U. W. (2012). Several evaluation and analytical indicators of regional autonomy implementation impacts in Indonesia: Energy and mineral resource sector development. Indonesian Mining Journal, 14(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.30556/imj.Vol14.No1.2011.504

- Stefanie, G., & Stefan, B. (2012). The relationship between intragenerational and intergenerational ecological justice. Environmental Values, 21(3), 331–335. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327112X13400390126055

- Sugiarti, S., Yunianto, B., Damayanti, R., & Hadijah, N. R. (2021). Legalization of illegal small-scale mining, as a policy of business guarantee and environmental management. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 882(1), 012077. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/882/1/012077

- Teubner, G. (2022). Substantive and reflexive elements in modern law.’ Luhmann and Law. Routledge.

- Uhlmann, D. M. (2009). Environmental crime comes of age: The evolution of criminal enforcement in the environmental regulatory scheme. Utah Law, Review(4), 1223–1252. Retrieved from https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/787

- Welsh, B. C., Zimmerman, G. M., & Zane, S. N. (2018). The centrality of theory in modern day crime prevention: Developments, challenges, and opportunities. Justice Quarterly, 35(1), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2017.1300312

- Weston, B. H. (2012). The theoretical foundations of intergenerational ecological justice: An overview. Human Rights Quarterly, 34(1), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2012.0003

- Zedner, L., & Roberts, J. V. (2012). Principles and values in criminal law and criminal justice: Essay in honour of Andrew Ashworth. Oxford University Press.

- Zwart, H. (2014). Human nature. In H. ten Have (Ed.), Encyclopedia of global bioethics (pp. 1–10). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05544-2_233-1