Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of workplace situation dimensions and individual dimensions on reducing audit quality (RAQ) with auditor burnout as a mediator. The sample consists of internal auditors who are members of the internal supervisory unit at public universities in Indonesia. Partial Least Squares (PLS) structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to test the hypotheses proposed in the study. The results found that time pressure and transactional psychological contracts have a positive effect on auditor burnout. In addition, time pressure and auditor burnout have a positive effect on RAQ behaviour, while the level of auditor satisfaction has a negative effect on RAQ. The results of testing indirect effects found that auditor burnout acts as a partial complementary mediation in the positive relationship between time pressure on RAQ, and as a full mediator of the positive relationship between transactional psychological contracts on RAQ behaviour. The theoretical implication of this study is the deepening of insight into the quality of internal audit in higher education in the scheme of the auditor’s mutual relationship with the organisation. The practical implication of this study is that internal audit departments in higher education can develop organisational situations with a supportive work environment, reduce pressure and develop programs to detect and prevent the adverse impact of internal auditor stress levels on both the quality of auditor performance and the organisation.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Internal auditors as human capital are part of the entity, so their behaviour is influenced by perceptions of situational dimensions in the work environment and individual dimensions. Internal auditors are unique and heterogeneous productive resources, which can determine audit quality differently. Internal auditors are expected to assist higher education leaders in identifying and reducing risks in the implementation of higher education activities that can interfere with the achievement of strategic goals. Waste of public resources still often occurs due to corrupt practices in public universities in Indonesia. On this basis, the theoretical contribution of this research is given to the theory of social exchange by adopting the stress paradigm because relationships in organisations in their development are becoming increasingly complex so they affect the behaviour of internal auditors. In addition, practically, this research shows the importance of internal audit departments in universities to develop a supportive work environment, and develop early detection and burnout prevention programmes for internal auditors.

1. Introduction

The increasing role of internal auditors in public sector organisations, with wider powers than the private sector, has increased the need to provide greater accountability and protect the public interest. Its role in promoting accountability and public governance makes the internal auditor as a key instrument, in generating evidence to create increased value and effectiveness of services and support public entities including higher education institutions (Langella et al., Citation2022). The added value of internal audit is becoming a focus for stakeholders due to increasing regulatory compliance requirements and the importance of governance and risk management (Al Shbail et al., Citation2022; Cohen & Sayag, Citation2010). The change in the number of public higher education institutions in 2020–2022 increased from 122 to 125. This shows an increase in the number of higher education institutions in Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik, Citation2023; Kemendikbud, Citation2020). Unfortunately, the increase in the number of higher education institutions is not followed by an increase in the quality of governance, where there are still several cases of fraud involving higher education institutions in Indonesia. This phenomenon suggests that internal audit quality plays an important role in higher education governance practices. On the other hand, many factors can influence auditor behaviour, which can even cause auditors to behave dysfunctionally, such as reducing audit quality.

Malone and Roberts (Citation1996) states that audit quality reduction behaviour that results in reduced effectiveness of audit evidence that should be collected is carried out by auditors intentionally in carrying out the audit program. Coram et al. (Citation2004) explain that in situations facing time budget pressure, auditors do not always work in accordance with standards, thereby increasing the potential for decreased audit quality. Perceptions built based on external motivation can also increase the likelihood of auditors performing dysfunctional behaviour. Perceptions or beliefs about the psychological contract between individuals and institutions will have an impact on individual performance within the institution which can lead to negative work outcomes (Arunachalam, Citation2021; Robinson & Morrison, Citation2000; Scheetz & Fogarty, Citation2019). As shown by Herrbach (Citation2001) when auditors experience dissatisfaction with organisational commitment in fulfilling the psychological contract between the auditor and the organisation, the auditor’s behavioural response leads to a decrease in audit quality. This is in accordance with Gillani et al. (Citation2021) who state that the business-to-business model is a conceptual framework that is usually used to understand the dimensions of the psychological contract between employees and organisations. In addition, internal motivation such as job satisfaction can be a determining factor for auditor behaviour in the workplace. The results of the study by Smith et al. (Citation2018) show that job satisfaction has a negative effect on the auditor’s intention to move. According to Hegazy et al. (Citation2023) the auditor’s intention to move is an indication of the auditor making unethical decisions and reducing audit quality.

Auditor behaviour in reducing audit quality is also often associated with the stress paradigm. Burnout experienced by auditors is a psychological response in the face of pressure and the current work environment. Burnout is often an indicator used to measure the role of the stress model in the work environment and its effect on auditor work outcomes (Al Shbail et al., Citation2018; Fogarty & Kalbers, Citation2006; Hegazy et al., Citation2023). Some research results show the negative effect of auditor burnout on the auditor himself, audit quality, and audit companies (Arad et al., Citation2020; Hegazy et al., Citation2023; Iswari, Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2018; Smith & Emerson, Citation2017)

Research on audit quality has so far focused on external audit quality. On the other hand, internal audit research has evaluated the effectiveness of the internal audit function (Turetken et al., Citation2020) and aspects of professional attributes such as independence, internal auditor competence, and internal audit size (Alzeban, Citation2020). According to Langella et al. (Citation2022) some researchers also highlight the social role of internal auditors in terms of safeguarding the public interest. The need to provide greater accountability and protect the public interest has led to the increased introduction of internal auditors in some public sector organisations, with broader powers than the private sector. Langella et al. (Citation2022) also confirmed that internal auditors are described as a key instrument for promoting public accountability and governance so that they can support democratic processes and outcomes by producing evidence of improving the value and effectiveness of services and supporting public entities in achieving their organisational goals.

Audit quality is often associated with ambiguities that make it difficult to prove (DeFond & Zhang, Citation2014; Herrbach, Citation2001). Most of the literature has used many proxies to measure audit quality, but there is no consensus on which measure is best and how to evaluate it. Based on the observation of DeFond and Zhang (Citation2014), none of the proxies used in the literature can provide a complete picture of audit quality. On the other hand, Roussy and Perron (Citation2018) also explain that the main weakness of the first group of academics on how to define internal audit quality is that they focus almost exclusively on independence and competence criteria. Similar to the literature on external audit quality, these studies ignored other important aspects of audit quality (Trotman & Duncan, Citation2018). Until now, there is no single definition of internal audit quality, due to the problem of diverse stakeholder perceptions (Roussy & Perron, Citation2018). Roussy and Perron (Citation2018) also assert that researchers do not have a comprehensive picture of how internal auditors perform their jobs. Therefore, it is important to examine internal audit quality starting from how auditors make ethical decisions in carrying out audit assignments.

Research on audit quality is still focused on internal audit quality studies in the private and corporate sectors (Abbott et al., Citation2016; Boskou et al., Citation2019; Singh et al., Citation2021). Some studies in the public sector focus more on internal audit effectiveness (Mahyoro & Kasoga, Citation2021; Yeboah, Citation2020). The same topic is also the focus of attention of internal audit researchers in higher education institutions (Demeke et al., Citation2020; Siyaya et al., Citation2021). Thus, research related to internal audit quality in the public sector, especially in higher education, is still lacking. Based on the results of previous research related to the quality of internal audit in higher education, especially those with state ownership involvement, has still not been adequately examined. Various proxies are used in measuring audit quality. Bello et al. (Citation2018) used auditor attributes, namely competence, independence, and internal audit size as a function of internal auditor quality, while Mihret and Yismaw (Citation2007) used the scope of internal auditor work, effective audit planning, fieldwork, and control, and effective communication. So there is no consensus to define audit quality in higher education institutions.

Previous research focused on the determinants of internal audit quality (Alzeban, Citation2015; Kai et al., Citation2022; Samagaio & Felício, Citation2022, Citation2023). These tests were also conducted by direct testing without considering the psychological responses that form before the actual behavioural responses of internal auditors. In this study, burnout is the auditor’s psychological response before manifesting into actual action. The existence of burnout indicates the low quality of the reciprocal relationship between the auditor and the organisation. This is supported by evidence from the results of research that burnout has a negative effect on the attitudes and behaviour of internal auditors in the workplace (Bernd & Beuren, Citation2021) and has a positive effect on the deviant behaviour of internal auditors (Al Shbail et al., Citation2018).

Cropanzano et al. (Citation2017) state that before individuals determine their behaviour in a reciprocal relationship, the emergence of behaviour can be informed by positive affectivity or negative affectivity. Thus the bournout response from internal auditors is a form of response due to negative affectivity. Based on the knowledge of researchers, no research attempts to reveal the ethical decision-making process of internal auditors in carrying out audits in the context of a reciprocal relationship mediated by burnout. Auditor burnout emerges as a function of auditors’ perceptions of the organisational situation and individual dimensions that help to conceptualise how time pressure, psychological contract, and job satisfaction may influence auditors’ behaviour at work (Appendix).

The literature on the use of psychological contracts in accounting is still lacking, even though these agreements are common in the workplace and are utilized in behavioral research (Young et al., Citation2021). To the best of the researcher’s knowledge, previous research related to the psychological contract has focused more on organisational breaches of the psychological contract and its direct effect on individual stress levels in the organisation (Arunachalam, Citation2021), turnover intention (Hammouri et al., Citation2022), organisational counterproductive behaviour (Ma et al., Citation2019) and individual workplace performance (Jayaweera et al., Citation2021). There are still few studies that examine the psychological contract experienced by the auditor profession in audit research. Meanwhile, research Herrbach (Citation2001) only focuses on fulfilling psychological contracts that have a direct impact on auditor behaviour to reduce audit quality. Thus, the purpose of the study is to examine the influence of workplace situational dimensions faced by internal auditors and individual dimensions in the reciprocal relationship model.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Time pressure

Previous research has proven that time pressure is positively correlated with increased stress, decreased performance and leads to dysfunctional auditor behaviour thereby reducing audit quality (Amiruddin, Citation2019; Coram et al., Citation2004; Gundry & Liyanarachchi, Citation2007). According to Coram et al. (Citation2004) time pressure increases the stress level of individuals in the organization which also has an impact on their cognitive processes. Johari et al. (Citation2019) mentioned that as a consequence of time pressure, there is a possibility to conduct superficial client document reviews in their audits.

Pierce and Sweeney (Citation2004) explain that acute time pressure has been shown to be more harmful to individual well-being than chronic time pressure, this is because time pressure can increase the level of stress faced by auditors in their assignments. The results of the study Nor et al. (Citation2017) prove that time pressure can have a detrimental effect on audit quality.

The greater the time pressure, the higher the probability of auditors performing dysfunctional behaviour such as shortening audit procedures, thus affecting the fairness and efficiency of audit judgement (Asriningpuri & Gruben, Citation2021). Different results were found by Johari et al. (Citation2019) that when auditors have less time to complete audit work, they will produce high-quality audits and improve their work performance. The results of the study (van Hau et al., Citation2023) also mentioned that audit quality is under threat when auditors become (highly) pressured by time. Although it is permissible to rely on the work of internal auditors, junior auditors do not rely too much on the work of internal auditors. Not relying on the internal auditor’s work when facing time pressure can lead to dysfunctional audit behaviour. Experienced auditors realise this risk, and hence, they rely on the internal auditor’s work (Nehme et al., Citation2022).

2.2. Psychological contract

From the perspective of social exchange theory, adequate performance is exchanged for the form of compensation received by the auditor (Herrbach, Citation2001). Dabos and Rousseau (Citation2004) refer to the psychological contract as an individual’s belief in being compensated for their loyalty to the organisation or a reciprocal obligation between the individual and the organisation. Psychological contracts range from transactional to relational, where transactional obligations are associated with short-term economic change and relational obligations are associated with long-term social change (Dabos & Rousseau, Citation2004). In addition, Santos et al. (Citation2018) state that exchange relationships rely on psychological, social, and interpersonal mechanisms.

Managers should be aware that psychological contracts are formed with or without the knowledge of employees because the impact of breaching such contracts is very serious. The consequences that can occur in research in the field of auditing are dysfunctional auditor behaviour to reduce audit quality. Given the significant impact documented in the literature, companies, organisations, and government agencies must raise awareness of psychological contracts to prevent avoidable breaches (Young et al., Citation2021).

Transactional elements were found to be related to individuals’ psychological contracts, such as the desire for tangible reward recognition, and more expected rewards and recognition in return for their job performance. The most significant reason for psychological breach was found when unmet expectations from the organisation were reflected in their low job performance and intention to move (Gulzar et al., Citation2022). The results of the study Arunachalam (Citation2021) show that violation of the psychological contract can have an impact on increasing counterproductive behaviour in the workplace. Jayaweera et al. (Citation2021) in their meta-analysis study stated that psychological contract violations affect individual behaviour in the workplace.

Psychological contract fulfilment influences employees’ intention to stay with their organisation, thereby minimising employee turnover. These results support that when employees realise effective psychological contract fulfilment meets their needs, it makes them more satisfied and increases their work productivity (Hammouri et al., Citation2022).

2.3. Job satisfaction

Positive feelings toward the work environment can increase auditor job satisfaction (Santos et al., Citation2018). The same was revealed by Piosik et al. (Citation2019) by using the term ‘taste’ in explaining the level of job satisfaction, so job satisfaction is closely related to the affective and cognitive processes of each individual. Consistent with the results Al-Shbiel (Citation2016) which shows that the level of job satisfaction affects the dysfunctional behaviour of auditors. In addition, according to Truong (2018), satisfied employees are more likely to detect and prevent severe accounting irregularities compared to minor accounting errors.

Job satisfaction is related to a person’s general attitude towards their job. Job satisfaction is also defined as a set of employee feelings about whether their job is pleasant or not (Salehi et al., Citation2020). Low levels of job satisfaction will result in negative work outcomes and will ultimately affect audit quality (Pham et al., Citation2022; Truong, 2018). According to Pham et al. (Citation2022), job satisfaction will have an impact on the intention to move auditors, where the move not only affects audit quality but also affects the efficiency of audit work. Consistent with Srimindarti et al. (Citation2020) and Truong (2018) provide the same view that the level of job satisfaction has a positive effect on auditor performance. Auditor job satisfaction has a positive effect on loyalty because auditor job satisfaction can be a pleasant feeling due to the perception of workers who are satisfied with their jobs (Muttaqin et al., Citation2021).

2.4. Auditor burnout

Stress can trigger an individual’s psychological reaction in the form of burnout. Burnout is a condition triggered by prolonged vulnerability to stress in the workplace (Lubbadeh, Citation2020). The impact of burnout is often associated with various types of unfavourable organisational outcomes including for individual employees (Lubbadeh, Citation2020). However, burnout researchers often consider job contextualisation factors more important than general dispositional factors in the development of this syndrome (Bianchi, Citation2018). Job burnout can also negatively impact audit quality and auditor performance (Hegazy et al., Citation2023). In addition, Smith and Emerson (Citation2017) mentioned that burnout acts as one of the main mediators that refine the stress paradigm among accountants’ behaviour in practice.

Work-related stress has a significant negative effect on performance, meaning that the less stress, the more employee performance increases. Work-related stress is a stressful condition that can cause physical and psychological imbalance, which in turn affects emotions, thought processes, and employee conditions. Job satisfaction is an important variable that organisations are expected to achieve. Dissatisfaction makes organisations inefficient and ineffective (Muttaqin et al., Citation2021).

2.5. Reduced audit quality

Reduced audit quality is an intentional actions taken by auditors during an engagement that inappropriately reduce the effectiveness of evidence, the effectiveness of the collected audit evidence is reduced by the auditor as a deliberate action is the definition of audit quality reduction behaviour (Malone & Roberts, Citation1996). In addition, Herrbach (Citation2001) adds that audit quality reduction behaviour is performed in audit procedures that reduce the level of evidence collected for the audit to cause adverse consequences so that the evidence collected is unreliable, incorrect or insufficient quantitatively or qualitatively.

Reduced audit quality leads to the failure of auditors to carry out appropriate audit stages and procedures. Reduced audit quality can also be defined as actions taken by auditors by reducing evidence and collecting evidence inappropriately and ineffectively, leading to the implementation of more audit programmes. Audit quality reduction behaviour occurs when auditors improperly perform audit procedures required to complete their duties (Amiruddin, Citation2019). To minimise the adverse effects of auditor behaviour to reduce audit quality, Zhao et al. (Citation2022) prove that personal and team characteristics in audit engagements can affect RAQ. Thus, auditors who practice reducing audit quality can be attributed to personal characteristics and audit situational factors (Amiruddin, Citation2019).

2.6. Hypothesis development

Organisational performance is not only related to organisational characteristics but also to individual performance (Samagaio & Felício, Citation2023). Thus, the expectations, beliefs, and feelings of individuals in the organisation also determine the direction of their behaviour in achieving organisational performance. Based on the social exchange theory, the principle of reciprocity underlies employees’ actions in the workplace, this means that when they feel their expectations of the organisation are met, they are not committed to unethical behaviour (Hazrati, Citation2017).

Social exchange theory (SET) is considered the gold standard for understanding workplace behaviour. Cropanzano et al. (Citation2017) define SET as (i) an initiation by an actor towards a target, (ii) an attitudinal or behavioural response from the target in return, and (iii) the resulting relationship. Relationships in today’s corporate world are becoming increasingly complex. Therefore, there is a need to update SETs with the increasing complexity of how organisations as actors create perceptions of individuals that can shape their behaviour in the workplace. Exchanges are not only limited to economic exchanges but also form psychological exchanges between organisations and individuals (Ahmad et al., Citation2022). Reciprocal motivation is the most important expected to occur in the social exchange model has been recognised as an important additional motivation in the workplace to facilitate employees’ willingness to cooperate for the benefit of the organization (Yang, Citation2020). Reciprocal motivation can be formed from internal and external aspects, so it can come from the organisational situation as well as from the individual’s self-dimension. In addition, Malone and Roberts (Citation1996) explain that organisational situational factors can influence auditor behaviour toward audit quality. Thus, time pressure, psychological contracts, and auditor job satisfaction are situational factors that can affect internal auditor behaviour.

Referring to the stress paradigm, burnout is a negative psychological response resulting from continuous exposure to job demands and/or interpersonal stressors. Burnout is one of the main mediators that enhance the stress paradigm among accountants (Smith & Emerson, Citation2017). On the other hand, social exchange theory only explains how targets respond to the initial actions of the organisation, but does not consider the psychological process of the situational dimensions of the organisation that can produce a psychological response in the form of burnout among internal auditors. Therefore, burnout is a function of time pressure, psychological contracts, and internal auditor job satisfaction to conceptualise the social exchange model in explaining actual internal auditors’ behavioural responses.

Working as an auditor is known as a stressful job. Responses to pressure can vary widely among auditors (Pham et al., Citation2022). The most common response that is often found when auditors are faced with time pressure is a psychological response that refers to an increase in stress to trigger burnout symptoms. Audit assignments that require prudence and are procedural in nature and the time pressure faced by internal auditors can trigger auditors to reach certain levels of stress. The results of research by Ariwibowo et al. (Citation2023) also confirm that the stress faced by auditors at work has a positive effect on the emergence of auditor behaviour to reduce audit quality.

Characterized by heavy workloads, numerous deadlines, and time pressure, internal auditing is considered a stressful job. The work of internal auditors is often under pressure to produce quality work. Larson (Citation2004) points out that job stress for internal auditors can be caused by time pressure. Time pressure refers to deadlines that become unreasonable to achieve and time demands that are imposed. For example, when employees do not have enough time to complete the tasks requested, then a worker is experiencing time pressure. On the other hand, recording how their time is spent in great detail is usually conducted by internal auditors (Larson, Citation2004).

Some supervisors create artificial time pressure as a way to motivate their subordinates (Larson, Citation2004). Consistent with Pierce and Sweeney (Citation2004), the pressure given to staff is a form of management control so that the performance of their employees can be achieved according to targets. However, as stress increases, performance increases only up to a certain point and usually decreases. In addition, time pressure is an organizational stressor that has the potential to increase job stress for auditors (Larson, Citation2004).

The most common response that is often found when auditors are faced with time pressure is a psychological response that leads to low exchange quality, causing increased stress to trigger burnout symptoms. Referring to social exchange theory, when auditors are faced with work environment conditions with time pressure, an exchange occurs that leads to negative work outcomes. The negative impact of time pressure has been proven by previous research, where time pressure is positively correlated with increased stress, and decreased performance underlying the dysfunctional behaviour of auditors to reduce audit quality (Amiruddin, Citation2019; Coram et al., Citation2004; Gundry & Liyanarachchi, Citation2007; Smith et al., Citation2018). Supported by the research of Asriningpuri and Gruben (Citation2021) and van Hau et al. (Citation2023), time budget pressure has a positive effect on auditor deviant behaviour related to audit quality. Therefore, the hypotheses in this study are:

H1: Time pressure has a positive effect on auditor burnout

H2: Time pressure has a positive effect on reducing audit quality

Transactional elements were found to be related to individuals’ psychological contracts, desire for tangible reward recognition, and more expected rewards and recognition in return for their job performance. These things will affect how they perform in the organisation (Gulzar et al., Citation2022).

Psychological contract breaches depend on specific types of economic and behavioural indicators in the workplace. In other words, the social exchange perspective predicts that employees actively restore equilibrium when a breach of the psychological contract occurs. On the other hand prospect theory would predict that this equilibrium may not exist when employees perceive the potential losses from withholding their effort as too great (Jayaweera et al., Citation2021). Thus auditor behaviour within the institution reflects how the initial actions of the organisation impact individual behavioural responses.

Individuals in organisations with transactional psychological contract perceptions are less involved in achieving the organisation’s vision and mission. Therefore, internal auditors with transactional psychological contracts do not commit to the organisation and will more easily experience burnout. The transactional and contractual motives underlying transactional psychological contracts can also have a negative impact on work outcomes such as reducing audit quality. Therefore, the hypotheses in this study are:

H3: Transactional psychological contract has a positive effect on auditor burnout.

H4: Transactional psychological contract has a positive effect on reducing audit quality

Psychological contract breaches can cause one party to feel psychologically and emotionally harmed, leading to loss of loyalty, motivation, and overall poor task performance (Ngobeni et al., Citation2022). The research results of Chan (Citation2021) show that burnout can arise from both relational and transactional psychological contracts that individuals build with organisations. However, the level of burnout will be lower if individuals have a relational psychological contract than a transactional. Gulzar et al. (Citation2022) assert that relational aspects can be reflected in individual work such as showing willingness to work without considering other things. Thus relational psychological contracts can increase behaviour that leads to positive individual performance in the organisation.

Based on the social exchange theory, when the foundation of relational psychological contracts has been built, auditors will be able to avoid burnout in their assignments because in this context internal auditors have a long-term commitment to achieving organisational goals. Thus preventing employees from acting inconsistently with the vision and mission of the organisation and violating their professional ethics. Therefore, the hypothesis in this study is:

H5: Relational psychological contract negatively affects auditor burnout

H6: Relational psychological contract negatively affects audit quality reduction

Auditor performance in institutions is positively influenced by the level of job satisfaction (Srimindarti et al., Citation2020). Based on the social exchange theory, an auditor who already has internal job satisfaction and gives higher appreciation to his current job will affect the auditor’s psychological response to the work situation he faces. Thus, the level of job satisfaction of internal auditors can reduce the potential for auditors to experience burnout and prevent auditors from engaging in dysfunctional behaviour. The research of Supriyatin et al. (Citation2019) also shows that the level of job satisfaction has a positive effect on audit quality. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated to test the negative effect of job satisfaction levels on auditor burnout and RAQ.

H7: Job satisfaction negatively affects auditor burnout

H8: Job satisfaction negatively affects audit quality reduction

Individuals who experience burnout and continue to deepen their experience may produce lower-quality work if they psychologically withdraw from the organization (Fogarty & Kalbers, Citation2006). Consistent with social exchange theory, auditors’ perceptions of their work environment will shape commitments to how they respond and behave at work. Thus, burnout, which is an individual’s response to stress, can have a negative effect on auditors’ attitudes and behaviour in the workplace such as reducing audit quality. Organisations need to create safe and supportive working conditions for internal auditors and create policies that can reduce the risk of burnout because burnout has a long-term impact on organisational performance and sustainability (Grzesiak, Citation2021). The results of the study by Hegazy et al. (Citation2023) show that auditor burnout can threaten audit quality. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated to test the positive effect of burnout on auditor burnout and RAQ.

H9: Auditor burnout has a positive effect on reducing audit quality

3. Research design and measurement variables

3.1. Research model

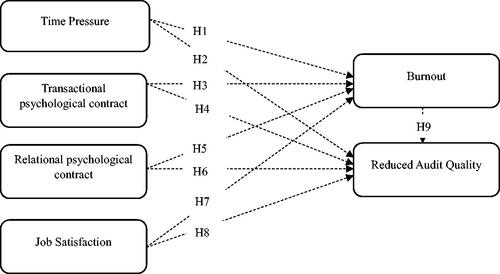

Based on the literature review and hypothesis development, this study tests nine hypotheses which are depicted in the research model in .

This study uses information from social media forums of internal supervisory units in public universities in Indonesia to find internal auditor phone numbers and other information. The Internal Control Unit forum is an association of internal auditors in internal control units in universities in Indonesia. The total number of forum members is 219, but this number is part of the members of the internal supervisory unit in state universities who serve as leaders or supervisors. Thus, not all members of the supervisory unit, including internal auditor staff, are members of the social media forum. In addition, there is no official database that shows the total population of chairpersons, secretaries, leaders/supervisors, and internal auditor staff in internal supervisory units in state universities in Indonesia. Therefore, researchers used nonprobability sampling, namely snowball sampling by sending a questionnaire link to 219 members of the internal audit social media forum at state universities in Indonesia and including directions to forward to all members in the internal supervisory unit of each institution.

Referring to the minimum sample size suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2017) with 5 independent variables, a significance value of 5%, and an R2 of 10%, the minimum number of samples is 122 samples. This study also uses G*power Software to calculate the minimum sample size. The maximum number of predictors in this study is 5, thus, with effect size, significance level, and statistical power of 0.15, 0.05, and 0.80 (Khasni et al., Citation2023), a minimum of 92 samples is required. The data collection period was carried out from August to November 2023. It found that 126 responses were valid.

3.2. Measurement variables

Reduced audit quality (RAQ) was measured using 13 items adapted from research (Samagaio & Felício, Citation2023). Questionnaire items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale, from 1 (never) to 7 (almost always). Measurement of the time pressure adapted from Pierce and Sweeney (Citation2004) which is also adapted by Samagaio and Felício (Citation2023). Time pressure questionnaire items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (very often). To examine relational and transactional psychological contracts, the psychological contract inventory developed by Rousseau (Citation2008) was used, as also adopted by Aggarwal and Bhargava (Citation2010). The item for job satisfaction was adapted from research by Smith et al. (Citation2018) using six question items. Auditor burnout was measured with nine items from the 24-item multidimensional role-specific (MROB) version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory adapted from Smith et al. (Citation2018). The burnout questionnaire items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

4. Empirical result

4.1. Characteristics of the respondents

The findings of the respondents’ characteristics are presented in . The results presented in reveal that the majority of respondents were 69% female and 57% male. Regarding the age of the respondents, the findings show that the majority of 49.2% are 30–39 years old, while 20.6% and 17.5% are 40–49 years old and 50–60 years old, respectively, and 12.7% are 20–29 years old. Most respondents have a master’s degree at 50.8%, doctorate and bachelor’s degrees at 24.6% each. The number of competency certifications that internal auditors have participated in is 71% with 1–3 types of certification, 10% with 3–5 types of certification, and 7.9% following more than 5 types of certification. This implies that internal audit departments at public universities in Indonesia have employed qualified staff who can perform their duties well. Mahyoro and Kasoga (Citation2021) stated that experience, education, and energy are important in organisational success. In addition, the findings also revealed that internal auditors who served as head of the internal audit department were 16%, internal audit secretaries were 6%, supervisors in the internal audit department were 28 and 50% for internal auditor staff positions.

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents.

4.2. Descriptive statistics

Referring to , descriptive statistical analysis shows that time pressure shows a low level, meaning that internal auditors in higher education sometimes experience time pressure during audit assignments. The relational psychological contract shows a greater average than the relational one. The average value of burnout experienced by internal auditors indicates that internal auditors also experience burnout in carrying out audit assignments. RAQ shows that sometimes internal auditors do not work according to standards so their behaviour reduces audit quality. From the 90th percentile value of the research findings, it can also be observed that some internal auditors admit that sometimes they complete audit assignments by not considering the importance of audit quality.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

4.3. Measurement model

The values of item loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE) as baseline measures for the measurement model are presented in . The convergent validity of the constructs was verified through the outer loading values and AVE values. In the measurement process of the model, indicators with an outer loading value above 0.5 are retained. In , it can be seen that overall the outer loading value is above the threshold suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2017). The AVE value of each variable is above the threshold value of 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2019). The composite reliability value of each variable is in the acceptable range of 0.8–0.958, this figure refers to the composite reliability value in the range of 0.6–0.7 which is still acceptable according to Hair et al. (Citation2019).

Table 3. Evaluation of the measurement model and collinearity.

Based on the results of the discriminant validity analysis, it can be seen from that the Fornell and Larcker criteria in this study have met the criteria, namely the square root value of the AVE for each construct must be greater than the highest correlation of other constructs (Hair et al., Citation2019). The next stage is the analysis of the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) in which shows that the HTMT ratio of all different constructs with a value of less than 0.85 (Hair et al., Citation2019) so that discriminant validity has been proven.

Table 4. Square root of AVE.

Table 5. Heterotrait-monotrait ratio.

To assess the structural model, the multicollinearity problem analysis was carried out in this study. Collinearity analysis is carried out by looking at the VIF value, it can be concluded from that there is no collinearity issue between constructs, with a VIF value of less than 5 (Hair et al., Citation2019). Analysis of the predictive quality of the model is done by calculating R2, which is used to evaluate the explanatory power of the model which measures the variance of the dependent variable explained by the independent variable. The R2 value for RAQ is 0.371 for burnout and 0.296, although it is considered a low score, Hair et al. (Citation2022) explain that values above 0.20 can be considered high in behavioral problems. The model feasibility test was analyzed using the SRMR and NFI indicators in the PLS output. The SRMR value in this study is 0.073, indicating that the model fit is acceptable because the value is less than 1. While the NFI value from the PLS output is 0.717 which indicates that the model fit is acceptable because it is still at the threshold value of 0 to 1 (Al Shbail et al., Citation2018).

Regarding the results of hypothesis testing (), the results show that RAQ is negatively and positively affected by independent variables. Time pressure has a positive effect on both auditor burnout and RAQ. Transactional psychological contracts have a positive effect on auditor burnout but no effect on RAQ. Relational psychological contracts do not affect auditor burnout and RAQ. Hypothesis testing also proves that auditor job satisfaction has a negative effect on RAQ while auditor burnout has a positive effect on RAQ.

Table 6. Structural model assessment.

The results of the analysis of the mediating effect of burnout on RAQ show that a significant mediating effect of burnout occurs in the relationship between time pressure on RAQ and transactional psychological contracts on RAQ, with the p-value of indirect testing being 0.035 and 0.005 respectively (Hair et al., Citation2022). While the p-value of the direct effect of time pressure on RAQ is significant at 0.034, the p-value of the direct effect of transactional psychological contracts is insignificant with a value of 0.461. Because the direct and indirect effects are positive, auditor burnout represents complementary mediation of the relationship between time pressure and RAQ. On the other hand, auditor burnout represents full mediation between transactional psychological contract and RAQ, due to the insignificant direct effect.

The results of testing hypotheses 1 and 2 show that time pressure has a positive effect on auditor burnout and internal auditor behaviour to reduce audit quality. The complexity of tasks and demands for internal auditor work increases the time pressure experienced by internal auditors in carrying out audit assignments. Time pressure has become a real problem faced by the auditor profession in carrying out audit programmes. According to Coram et al. (Citation2004) time pressure increases the stress level of individuals in the organisation which also has an impact on their cognitive processes. The results of hypothesis 1 and 2 are in line with the results of research by Amiruddin (Citation2019) and Nehme et al. (Citation2022), which show that time pressure has a positive effect on stress and auditor behaviour to reduce audit quality. Time pressure causes a lack of balance in the auditor’s life. Time pressure makes auditors invest their personal time, thus disrupting their psychological well-being at work and increasing the potential for behaviour that leads to violations of the code of ethics to threaten audit quality (Nehme et al., Citation2022).

The results of testing hypothesis 3 accepted, that transactional psychological contracts affect the burnout experienced by internal auditors. Jha et al. (Citation2019) state that transactional psychological contracts, on the other hand, are more related to the obligation to complete narrow tasks with limited involvement, thus reflecting the temporary nature of the relationship. This finding is in line with the phenomenon in Indonesian public higher education institutions, which are currently in the wheel of developing campus autonomy not only in terms of finance but also human resources. Recruitment in some universities can be in the form of career patterns for permanent and non-permanent employees. With the situation faced by internal auditors in a temporary psychological contract in limited involvement as non-permanent employees, this can trigger burnout experienced by internal auditors. On the other hand, the results of hypothesis 4 testing were rejected. This finding is consistent with the results of research by Jha et al. (Citation2019) which states that transactional psychological contracts have a positive impact on individual behaviour by increasing employee work attachment and allowing workers to have a structured relationship with the organisation. According to Jha et al. (Citation2019), transactional contracts actually reduce uncertainty over job demands and help increase individuals’ psychological resources, thus affecting their work engagement.

The results of testing hypotheses 5 and 6 were rejected. These results are consistent with Young et al. (Citation2021) who state that transactional psychological contracts are often opposite to expectations, so the feeling of violation of a relational psychological contract violation is not more severe than a transactional violation. In other words, internal auditors choose to react to transactional psychological contracts rather than relational ones. Thus, in this case, internal auditors do not respond to both psychological responses and behavioural responses because in general violations are more common in transactional psychological contracts than relational psychological contracts.

The results of testing hypothesis 7 are not supported in this study, where the higher level of job satisfaction has no impact on auditor burnout. This finding is supported by the results of research by Hegazy et al. (Citation2023) proving that young auditors are always looking for motivation and encouragement to advance in their work. Thus, these auditors are more focused on their level of satisfaction based on achievement than the experience of burnout. The experience of burnout among internal auditors can differ based on age groups including the tenure of internal auditors in higher education institutions. On the other hand, the results of testing hypothesis 8 show that the level of job satisfaction has a negative effect on RAQ. When auditors feel satisfaction in doing their job, it will increase their abilities and potential in the team, resulting in work effectiveness in the institution (Saat et al., Citation2021). In addition, when employees are satisfied with the intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction of their working conditions, this can lead to greater organisational commitment (Singh & Onahring, Citation2019). This finding can also be explained, where the level of job satisfaction as a positive affection can encourage positive exchanges between internal auditors and institutions in the form of a decrease in the level of RAQ.

Hypothesis 9 is supported in this study, where burnout has a positive effect on RAQ. Based on social exchange theory, when internal auditors get support in the form of a work environment that does not cause burnout, the auditors will provide a positive exchange in the form of a decrease in potential RAQ. Conversely, the higher the level of burnout faced by the auditor, the closer the auditor will be to the behavioral consequences of reducing audit quality. This finding is consistent with the results of the research by Bernd and Beuren (Citation2021) and Smith and Emerson (Citation2017).

5. Conclusion and future research

Based on the research results, direct testing of research proves that time pressure has a positive effect on auditor burnout and auditor behaviour to reduce audit quality. However, among psychological contracts, only transactional psychological contracts have a positive effect on burnout. This study also proves that the level of job satisfaction has a negative effect on RAQ and auditor burnout has a positive effect on auditor behaviour in reducing audit quality. When testing indirect effects, there is a significant mediating effect on the relationship between time pressure and transactional psychological contracts on RAQ mediated by auditor burnout. On the other hand, the test results also show that a complementary partial mediation effect occurs in time pressure on RAQ mediated by burnout. However, the full mediation effect occurs in the relationship between transactional psychological contracts on RAQ mediated by burnout.

There are several theoretical implications of our research findings. First, this study contributes to strengthening insights on internal audit quality in higher education institutions. Second, this study examines the traditional psychological contract, which has been missing in the research trend, as similar studies have focused more on psychological contract violations. Thus, this study is the first to examine the relationship between transactional and relational psychological contracts and internal audit quality in higher education institutions.

The findings of this study may also provide practical implications. First, internal audit departments in higher education to develop organisational situations to minimise the perception of transactional contracts between internal auditors and organisations. Second, there is a need for the socialisation of institutional programmes to reduce the emergence of potential burnout and increase the level of job satisfaction of auditors. Internal audit departments in higher education institutions can also take measures to prevent burnout among internal auditors by making them aware of work-related stressors (root causes of burnout) and their impact on the human psyche and emotions and showing them effective ways to reduce their impact. It is also important for internal audit departments to socialise and engage auditors in training related to resilience and coping with stressful situations. In addition, programmes that teach managers about the early detection of stress symptoms in employees and ways to prevent their development are needed (Hegazy et al., Citation2023). Organisations that have beliefs in the form of a shared psychological contract can have a major impact on organisational culture, creating a comfortable work environment for workers and reducing the level of stress faced by employees (Raiborn & Stern, Citation2019). Therefore, creating a more friendly, familiar, and personalised organisational climate will strengthen the relational psychological contract between employees and their organisations in society (Kutaula et al., Citation2020). Thus, the dark side of business-to-business relationships in the paradigm of organisational stress can be minimised, specifically by reducing auditor burnout and behaviours that can reduce audit quality.

This study also has limitations in that it focuses only on the technical and organisational dimensions without considering the organisational situation concerning ethical and cultural values. Referring to the sociocultural concept, in Asian countries, future research needs to understand the ethical and cultural dimensions as both play an important role in how employees perceive work, their attitudes and behaviours at work, and their responses to changes in work relationships.

Author contributions

The first author (Putu Prima Wulandari) contributed to the conception, research design, analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the paper. The second, third, and fourth authors (Made Sudarma, Yeney Widya Prihatiningtias, Zaki Baridwan), as supervisors in this study made their contributions to the critical refinement of the intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. All authors have reviewed and agreed to take responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgment

This journal article is written by Putu Prima Wulandari a doctoral student of accounting science, at the Accounting Department, Brawijaya University. I am very grateful to Made Sudarma, Yeney Widya Prihatiningtias, Zaki Baridwan, as supervisors who have provided input, review and constructive feedback of the writing of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Please contact the following email: [email protected], if there are questions regarding the data and questionnaire items in this study, the authors are willing to provide complete information.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Putu Prima Wulandari

Putu Prima Wulandari is an Assistant Professor in the Accounting Department of Brawijaya University who is currently pursuing a doctor of accounting programme. Her research interests include auditing, finance, and behavioural accounting. She has research papers published in national and international journals.

Made Sudarma

Made Sudarma is a professor in the Accounting Department of Brawijaya University. His interests include auditing and behavioural accounting. He has research papers published in national and Scopus-indexed international journals.

Yeney Widya Prihatiningtias

Yeney Widya Prihatiningtias is an Assistant Professor in the Accounting Department at Brawijaya University. Her interests include financial accounting and corporate governance. She has research papers published in national and Scopus-indexed international journals.

Zaki Baridwan

Zaki Baridwan is an Assistant Professor in the Accounting Department at Brawijaya University. His interests include auditing, accounting information systems, and behavioural accounting. He has research papers published in national and Scopus-indexed international journals.

References

- Abbott, L. J., Daugherty, B., Parker, S., & Peters, G. F. (2016). Internal audit quality and financial reporting quality: The joint importance of independence and competence. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12099

- Aggarwal, U., & Bhargava, S. (2010). Predictors and outcomes of relational and transactional psychological contract. Psychological Studies, 55(3), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-010-0033-2

- Ahmad, R., Nawaz, M. R., Ishaq, M. I., Khan, M. M., & Ashraf, H. A. (2022). Social exchange theory: Systematic review and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(iii), 1015921. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1015921

- Al Shbail, M. O., Alshurafat, H., Ananzeh, H., & Bani-Khalid, T. O. (2022). The moderating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between human capital dimensions and internal audit effectiveness. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2115731. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2115731

- Al Shbail, M., Salleh, Z., & Mohd Nor, M. N. (2018). Antecedents of burnout and its relationship to internal audit quality. Business and Economic Horizons, 14(4), 789–817. https://doi.org/10.15208/beh.2018.55

- Ali, H. (2020). Mutuality or mutual dependence in the psychological contract: A power perspective. Employee Relations, 42(1), 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-09-2017-0221

- Al-Shbiel, S. O. (2016). An examination the factors influence on unethical behaviour among Jordanian external auditors: Job satisfaction as a mediator. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 6(3), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARAFMS/v6-i3/2276

- Alzeban, A. (2015). The impact of culture on the quality of internal audit: An empirical study. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 30(1), 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X14549460

- Alzeban, A. (2020). The relationship between the audit committee, internal audit and firm performance. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 21(3), 437–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-03-2019-0054

- Amiruddin, A. (2019). Mediating effect of work stress on the influence of time pressure, work–family conflict and role ambiguity on audit quality reduction behavior. International Journal of Law and Management, 61(2), 434–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-09-2017-0223

- Arad, H., Moshashaee, S. M., & Eskandari, D. (2020). The study of individual resilience levels, auditor stress and reducing audit quality practices in audit profession. Accounting and Auditing Review, 27(2), 154–179. https://doi.org/10.22059/acctgrev.2020.291564.1008294

- Ariwibowo, R., Nurkholis, N., & Saraswati, E. (2023). Reduced audit quality practices among local-government’s internal auditors: What to do with stress and working condition. Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis, 18(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.24843/JIAB.2023.v18.i01.p07

- Arunachalam, T. (2021). The interplay of psychological contract breach, stress and job outcomes during organizational restructuring. Industrial and Commercial Training, 53(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-03-2020-0026

- Asriningpuri, G. P., & Gruben, F. (2021). The effect of time budget pressure and dysfunctional auditor behavior on audit quality: A case study in an audit firm in Indonesia. Diponegoro Journal of Accounting, 10(4), 1–12. http://ejournal-s1.undip.ac.id/index.php/accounting.

- Badan Pusat Statistik. (2023). Jumlah Perguruan Tinggi, Dosen, dan Mahasiswa (Negeri dan Swasta) di Bawah Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset, dan Teknologi Menurut Provinsi, 2022. Bps.Go.Id. https://www.bps.go.id/indikator/indikator/view_data_pub/0000/api_pub/cmdTdG5vU0IwKzBFR20rQnpuZEYzdz09/da_04/1

- Bello, S. M., Ahmad, A. C., & Yusof, N. Z. M, Tunku Puteri Intan Safinaz School of Accountancy Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia. (2018). Internal audit quality dimensions and organizational performance in Nigerian federal universities: the role of top management support. Journal of Business & Retail Management Research, 13(01), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.24052/JBRMR/V13IS01/ART-16

- Bernd, D. C., & Beuren, I. M. (2021). Self-perceptions of organizational justice and burnout in attitudes and behaviors in the work of internal auditors. Revista Brasileira de Gestao de Negocios, 23(3), 422–438. https://doi.org/10.7819/RBGN.V23I3.4110

- Bianchi, R. (2018). Burnout is more strongly linked to neuroticism than to work-contextualized factors. Psychiatry Research, 270(November), 901–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.015

- Boskou, G., Kirkos, E., & Spathis, C. (2019). Classifying internal audit quality using textual analysis: the case of auditor selection. Managerial Auditing Journal, 34(8), 924–950. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-01-2018-1785

- Chan, S. (2021). The interplay between relational and transactional psychological contracts and burnout and engagement. Asia Pacific Management Review, 26(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2020.06.004

- Cohen, A., & Sayag, G. (2010). The effectiveness of internal auditing: An empirical examination of its determinants in Israeli organisations. Australian Accounting Review, 20(3), 296–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1835-2561.2010.00092.x

- Coram, P., Ng, J., & Woodliff, D. R. (2004). The effect of risk of misstatement on the propensity to commit reduced audit quality acts under time budget pressure. Auditing, 23(2), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2004.23.2.159

- Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E. L., Daniels, S. R., & Hall, A. V. (2017). Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 479–516. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0099

- Dabos, G. E., & Rousseau, D. M. (2004). Mutuality and reciprocity in the psychological contracts of employees and employers. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.52

- DeFond, M., & Zhang, J. (2014). A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2–3), 275–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.09.002

- Demeke, T., Kaur, J., & Kansal, R. (2020). The practices and effectiveness of internal auditing among public higher education institutions, Ethiopia. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 10(07), 1291–1315. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2020.107086

- Fogarty, T. J., & Kalbers, L. P. (2006). Internal auditor burnout: An examination of behavioral consequences. Advances in Accounting Behavioral Research, 9, 51–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1475-1488(06)09003-X

- Gillani, A., Kutaula, S., & Budhwar, P. S. (2021). Psychological contract breach: Unraveling the dark side of business-to-business relationships. Journal of Business Research, 134(May), 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.008

- Grzesiak, L. (2021). Internal auditor burnout – an urgent area for research? Kwartalnik Nauk o Przedsiębiorstwie, 58(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.33119/KNoP.2020.58.1.5

- Gulzar, S., Hussain, K., Akhlaq, A., Abbas, Z., & Ghauri, S. (2022). Exploring the psychological contract breach of nurses in healthcare: An exploratory study. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 16(1), 204–230. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-03-2021-0102

- Gundry, L. C., & Liyanarachchi, G. A. (2007). Time budget pressure, auditors’ personality type, and the incidence of reduced audit quality practices. Pacific Accounting Review, 19(2), 125–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/01140580710819898

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (Third). SAGE Publications Inc.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M.Jr., (2017). Assessing PLS-SEM Results Part I. In Joseph F. Hair, G. Tomas M. Hult, Christian Ringle, & Marko Sarstedt (Eds.), A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hammouri, Q., Altaher, A. M., Rabaa’i, A., Khataybeh, H., & Al-Gasawneh, J. (2022). Influence of psychological contract fulfillment on job outcomes: A case of the academic sphere in Jordan. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 20(3), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.20(3).2022.05

- Hazrati, S. (2017). Psychological contract breach and affective commitment in banking sector: The Mediation effect of psychological contract violation and trust. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 7(4), 36–45. https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/psychological-contract-breach-and-affective-commitment-in-banking-sectorthe-mediation-effect-of-psychological-contract-violation-a-94397.html.

- Hegazy, M., El-Deeb, M. S., Hamdy, H. I., & Halim, Y. T. (2023). Effects of organizational climate, role clarity, turnover intention, and workplace burnout on audit quality and performance. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 19(5), 765–789. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-12-2021-0192

- Herrbach, O. (2001). Audit quality, auditor behaviour and the psychological contract. European Accounting Review, 10(4), 787–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180127400

- Iswari, T. I. (2020). Effects of organizational–professional conflict and auditor burnout on dysfunctional audit behaviour. Holistica – Journal of Business and Public Administration, 11(3), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.2478/hjbpa-2020-0034

- Jayaweera, T., Bal, M., Chudzikowski, K., & de Jong, S. (2021). The impact of economic factors on the relationships between psychological contract breach and work outcomes: A meta-analysis. Employee Relations, 43(3), 667–686. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-03-2020-0095

- Jha, J. K., Pandey, J., & Varkkey, B. (2019). Examining the role of perceived investment in employees’ development on work-engagement of liquid knowledge workers: Moderating effects of psychological contract. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 12(2), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGOSS-08-2017-0026

- Johari, R. J., Ridzoan, N. S., & Zarefar, A. (2019). The influence of work overload, time pressure and social influence pressure on auditors’ job performance. International Journal of Financial Research, 10(3), 88–106. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijfr.v10n3p88

- Kai, R., Yusheng, K., Ntarmah, A. H., & Ti, C. (2022). Constructing internal audit quality evaluation index: Evidence from listed companies in Jiangsu province, China. Heliyon, 8(9), e10598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10598

- Kemendikbud. (2020). Statistik Pendidikan Tinggi (Higher education statistic) 2020. PDDikti Kemendikbud, 5, 81–85. https://pddikti.kemdikbud.go.id/publikasi

- Khasni, F. N., Keshminder, J. S., Chuah, S. C., & Ramayah, T. (2023). A theory of planned behaviour: perspective on rehiring ex-offenders. Management Decision, 61(1), 313–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-08-2021-1051

- Kutaula, S., Gillani, A., & Budhwar, P. S. (2020). An analysis of employment relationships in Asia using psychological contract theory: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 30(4), 100707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100707

- Langella, C., Vannini, I. E., & Persiani, N. (2022). What are the determinants of internal auditing (IA) introduction and development? Evidence from the Italian public healthcare sector. Public Money & Management, 43(3), 268–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2022.2129591

- Larson, L. L. (2004). Internal auditors and job stress. Managerial Auditing Journal, 19(9), 1119–1130. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900410562768

- Lee, B., Lee, C., Choi, I., & Kim, J. (2022). Analyzing determinants of job satisfaction based on two-factor theory. Sustainability, 14(19), 12557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912557

- Liu, W., Zhao, S., Shi, L., Zhang, Z., Liu, X., Li, L., Duan, X., Li, G., Lou, F., Jia, X., Fan, L., Sun, T., & Ni, X. (2018). Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 8(6), e019525. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019525

- Lubbadeh, T. (2020). Job burnout: A general literature review. International Review of Management and Marketing, 10(3), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.32479/irmm.9398

- Ma, B., Liu, S., Lassleben, H., & Ma, G. (2019). The relationships between job insecurity, psychological contract breach and counterproductive workplace behavior: Does employment status matter? Personnel Review, 48(2), 595–610. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2018-0138

- Mahyoro, A. K., & Kasoga, P. S. (2021). Attributes of the internal audit function and effectiveness of internal audit services: evidence from local government authorities in Tanzania. Managerial Auditing Journal, 36(7), 999–1023. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-12-2020-2929

- Malone, C. F., & Roberts, R. W. (1996). Factors associated with the incidence of reduced audit quality behaviors. Auditing, 15(2), 49–64.

- Mihret, D. G., & Yismaw, A. W. (2007). Internal audit effectiveness: An Ethiopian public sector case study. Managerial Auditing Journal, 22(5), 470–484. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900710750757

- Morrison, E. W., & Robinson, S. L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. The Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 226–256. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707180265

- Muttaqin, G. F., Machfuzhoh, A., & Fazri, E. (2021). Creation of auditor loyalty: Improving competence, quality of work and job satisfaction. Jurnal Reviu Akuntansi dan Keuangan, 11(3), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.22219/jrak.v11i3.16998

- Nehme, R., Michael, A., & Haslam, J. (2022). The impact of time budget and time deadline pressures on audit behaviour: UK evidence. Meditari Accountancy Research, 30(2), 245–266. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-09-2019-0550

- Ngobeni, D. A., Saurombe, M. D., & Joseph, R. M. (2022). The influence of the psychological contract on employee engagement in a South African bank. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(August), 958127. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.958127

- Nor, M. N. M., Smith, M., Ismail, Z., & Taha, R. (2017). The effect of time budget pressure on auditors’ behaviour. Advanced Science Letters, 23(1), 356–360. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2017.7185

- Pham, Q. T., Tan Tran, T. G., Pham, T. N. B., & Ta, L. (2022). Work pressure, job satisfaction and auditor turnover: Evidence from Vietnam. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2110644. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2110644

- Pierce, B., & Sweeney, B. (2004). Cost–quality conflict in audit firms: an empirical investigation. European Accounting Review, 13(3), 415–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963818042000216794

- Piosik, A., Strojek-Filus, M., & Sulik-G, A. (2019). Gender and age as determinants of job satisfaction in the accounting profession: Evidence from Poland. Sustainability, 11(11), 3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113090

- Raiborn, C., & Stern, M. Z. (2019). The need for new psychological contracts in the auditing profession. Research on Professional Responsibility and Ethics in Accounting, 22, 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1574-076520190000022006

- Robinson, S. L., & Morrison, E. W. (2000). The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(5), 525–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200008)21:5<525::AID-JOB40>3.0.CO;2-T

- Rousseau, D. M. (2008). Psychological contract inventory. September 4. https://www.cmu.edu/tepper/faculty-and-research/assets/docs/psychological-contract-inventory-2008.pdf.

- Roussy, M., & Perron, A. (2018). New perspectives in internal audit research: A structured literature review. Accounting Perspectives, 17(3), 345–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3838.12180

- Saat, M. M., Halim, N. S. A., & Rodzalan, S. A. (2021). Job satisfaction among auditors. Advanced International Journal of Banking, Accounting and Finance, 3(7), 72–84. https://doi.org/10.35631/AIJBAF.37006

- Salehi, M., Seyyed, F., & Farhangdoust, S. (2020). The impact of personal characteristics, quality of working life and psychological well-being on job burnout among Iranian external auditors. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 23(3), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOTB-09-2018-0104

- Samagaio, A., & Felício, T. (2022). The influence of the auditor’s personality in audit quality. Journal of Business Research, 141(May 2021), 794–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.082

- Samagaio, A., & Felício, T. (2023). The determinants of internal audit quality. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 32(4), 417–435. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-06-2022-0193

- Santos, V. d., Pazetto, C. F., Wilvert, N. R., & Beuren, I. M. (2018). Efeitos do contrato psicológico na afetividade e satisfação no trabalho de auditores. Revista Catarinense da Ciência Contábil, 17(50), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.16930/2237-7662/rccc.v17n50.2546

- Scheetz, A. M., & Fogarty, T. J. (2019). Walking the talk contract venues for potential whistleblowers. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 15(4), 654–677. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-06-2018-0047

- Singh, K. S. D., Ravindran, S., Ganesan, Y., Abbasi, G. A., & Haron, H. (2021). Antecedents and internal audit quality implications of internal audit effectiveness. International Journal of Business Science and Applied Management, 16(2), 1–21.

- Singh, K. D., & Onahring, B. D. (2019). Entrepreneurial intention, job satisfaction and organisation commitment – construct of a research model through literature review. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-018-0134-2

- Siyaya, M. C., Epizitone, A., Jali, L. F., & Olugbara, O. O. (2021). Determinants of internal auditing effectiveness in a public higher education institution. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 25(2), 1–18.

- Smith, K. J., & Emerson, D. J. (2017). An analysis of the relation between resilience and reduced audit quality within the role stress paradigm. Advances in Accounting, 37, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2017.04.003

- Smith, K. J., Emerson, D. J., & Boster, C. R. (2018). An examination of reduced audit quality practices within the beyond the role stress model. Managerial Auditing Journal, 33(8/9), 736–759. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-07-2017-1611

- Srimindarti, C., Oktaviani, R. M., Hardiningsih, P., & Udin, U. (2020). Determinants of job satisfaction and performance of auditors : A case study of Indonesia, 21(178), 84–89.

- Supriyatin, E., Ali Iqbal, M., & Indradewa, R. (2019). Analysis of auditor competencies and job satisfaction on tax audit quality moderated by time pressure (case study of Indonesian tax offices). International Journal of Business Excellence, 19(1), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBEX.2019.101711

- Trotman, A. J., & Duncan, K. R. (2018). Internal audit quality: Insights from audit committee members, senior management, and internal auditors. Auditing, 37(4), 235–259. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51877

- Truong, P. (2018, September). The impact of audit employee job satisfaction on audit quality. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3257437

- Turetken, O., Jethefer, S., & Ozkan, B. (2020). Internal audit effectiveness: Operationalization and influencing factors. Managerial Auditing Journal, 35(2), 238–271. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-08-2018-1980

- van Hau, N., Hai, P. T., Diep, N. N., & Giang, H. H. (2023). Determining factors and the mediating effects of work stress to dysfunctional audit behaviors among Vietnamese auditors. Quality – Access to Success, 24(193), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.47750/QAS/24.193.18

- Yang, J. S. (2020). Differential moderating effects of collectivistic and power distance orientations on the effectiveness of work motivators. Management Decision, 58(4), 644–665. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-10-2018-1119

- Yeboah, E. (2020). Critical literature review on internal audit effectiveness. Open Journal of Business and Management, 08(05), 1977–1987. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2020.85121

- Young, K. M., Stammerjohan, W. W., Bennett, R. J., & Drake, A. R. (2021). Psychological contract research in accounting literature. Advances in Accounting Behavioral Research, 24, 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1475-148820200000024005

- Zhao, M., Li, Y., & Lu, J. (2022). The effect of audit team’s emotional intelligence on reduced audit quality behavior in audit firms: Considering the mediating effect of team trust and the moderating effect of knowledge sharing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(December), 1082889. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1082889

Appendix

Survey items used in this study

1. Time pressure adopted from Pierce and Sweeney (Citation2004)

In general, were the time budgets for jobs you worked on since last month?

How often do you achieve your time budget?

If you did not underreport any time, i.e. if you were to charge all of your chargeable time to the correct codes, how often would you meet the budget?

How often are you given a time budget for your work?

How often is the length of time you are booked to audit assignments adequate?

2. Transactional psychological contract adopted from Rousseau (Citation2008)

Perform only required tasks

Do only what I am paid to do

Fulfill a limited number of responsibilities

Only perform specific duties I agreed to when hired

Limited involvement in the organization

Training me only for my current job

A job limited to specific, well-defined responsibilities

Require me to do only limited duties I was hired to perform

I will work for this company indefinitely (reverse)

I am heavily involved in my place of work (reverse)

3. Relational psychological contract adopted from Rousseau (Citation2008)

Be loyal to this organization

Take this organization’s concerns personally

Protect this organization’s image

Commit myself personally to this organization

Concern for my personal welfare

Be responsive to employee concerns and well-being

Make decisions with my interests in mind

Concern for my long-term well-being

4. Auditor burnout adopted from Smith et al. (Citation2018)

I feel a lack of personal concern for my supervisor.

I feel I’m becoming more hardened toward my supervisor.

I feel I am becoming less sympathetic toward top management.

I feel I am an important asset to my supervisor.

I feel I satisfy many of the demands set by top management.

I feel I make a positive contribution toward top management goals.

Working with my boss directly puts too much stress on me.

I feel emotionally drained by the pressure my boss puts on me.

I feel burned out from trying to meet top management’s expectations.

5. Job satisfaction adopted from Smith et al. (Citation2018)

With the amount of recognition and respect that I receive for my work

With the opportunity in my job to achieve excellence in my work

With the extent to which I am recognized for my work

With the respect that I receive for my work

With the degree to which my work is perceived to be important by the company

With respect to my job overall

6. Reduced Audit Quality (RAQ) adopted from Samagaio and Felício (Citation2023)

Accepted poor explanations from colleagues working in other departments of the Entity

Accepted audit evidence whose relevance and/or reliability was questionable

Performed superficial revisions to the Entity’s documents

Biasing of sample selection in favour of less troublesome items

Greater reliance was placed on work performed by staff from other departments of the Entity compared to what should be done.

Failure to research the application of laws and other regulations (e.g. accounting standards)

Premature sign-off an internal audit procedure performed in a certain area

Reduction in the amount of work on an audit step below what was considered reasonable

Failure to complete procedures required in an audit programme step in ways

Reduction in the sample size specified in the audit programme without noting the reduction

Reduction in the amount of documentation below that considered acceptable by the Internal Audit Department

Failure to apply the attribute standards prescribed in the International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing

Failure to apply the performance standards prescribed in the International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing