Abstract

Government service mini-programs (GSMPs) in mobile payment have become integral to the eGovernment in China’s Greater Bay Area (GBA). The ubiquitous nature of WeChat and Alipay provides excellent flexibility for accessing public e-services. Yet, the determinants and mechanisms of adoption have not been identified. A convenience sample was collected from GBA core cities for statistical and SEM analysis. The findings suggest that service quality, trust in eGovernment, ubiquity, and social influence constitute the determinants. A structural model grounded on Self-Determination and Motivation theory is verified, where perceived value and intention contribute a high explanatory power. Benevolence, integrity, and competence are crucial indicators of trust, while social influence amplifies risk perception. Surprisingly, government support negatively moderates the impact of determinants on intention, indicating that over-intervention leads to inhibition. The mechanism illustrates the beneficial impact of GSMPs as the smart government channel and provides insights into addressing service homogeneity and policy applicability. Relevant theoretical and managerial implications are instructive to policymakers and practitioners of smart city innovation and in-depth integration in GBA.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Government service mini-programs (GSMPs) in WeChat and Alipay offer a variety of public services to China’s GBA cities, leading to a new era of digital governance. High-quality e-services are standard expectations of the public. Homogeneity, malfunctions, and latency are barriers to quality perception. Policymakers and practitioners should explore the reform scope and innovation of public e-services from various perspectives and strive to construct high-efficiency and high-level Bay Area cities. This article investigates the adoption mechanisms of GSMPs, demonstrates the significance of trust and policy support, and provides valuable insights into addressing homogeneity and promoting service integration. Only by comprehensively understanding citizens’ intrinsic motivations and external needs, as well as continuously fostering service innovation, public confidence, and social cohesion, will we be able to respond to the opportunities and challenges presented by smart city construction.

1. Introduction

Government service mini-programs (GSMPs) have become a key component of China’s smart government (Center for Digital Governance et al., Citation2021). In particular, accessing service mini-programs from WeChat and Alipay is an emerging trend in the Greater Bay Area (GBA) cities since they have always been the most effective tools with high market shares in China (iResearch Global, Citation2019; QuestMobile, Citation2021). The mini-programs are free to install and cross-platform since they are developed to be executed as internal applications of mobile payment apps. It overcomes some limitations of traditional apps, such as development for multiple platforms, installation, and configuration. Due to these benefits, mini-programs have become essential to developing smart cities and the success of the GBA’s smart government. Simultaneously, understanding the nature of GSMP adoption on mobile payment platforms is consistently reported as a major challenge for practitioners and academics. The continued development of eGovernment solutions focuses on optimizing and integrating various public services to enhance people’s willingness to consider adoption (Bureau, Citation2021). The GBA community has widely recognized mobile payment platforms, with WeChat and Alipay providing seamless connectivity. The cooperation between mobile payment and eGovernment provides a wide range of public e-services, forming a unique and innovative pattern in GBA. Improving service quality, popularizing public e-services, and enhancing their role in radiating surrounding areas are in line with the development outline of GBA.

Xu et al. argued that online and offline service quality are equally crucial to citizens nowadays; however, current service quality frameworks only apply to specific eGovernment services (Xu et al., Citation2013). Relevant constructs are complicated and difficult to apply practically to service mini-programs (Zaidi & Qteishat, Citation2012). Issues of varied quality and homogeneity remain unresolved (Center for Digital Governance et al., Citation2021). To promote acceptance and support of eGovernment, gaining citizens’ trust is the key (Zheng & Ma, Citation2022). Although Scott et al. have explained a portion of citizens’ perceptions of eGovernment success, related theories mainly focus on government trust and trust in the Internet (Alzahrani et al., Citation2017; Scott et al., Citation2016). The citizen perspective has been neglected, and the conceptualization of trust in eGovernment remains poorly detailed.

The ubiquity of mini-programs brings value in functionality and performance (QuestMobile, Citation2021), as well as potential risks to the network environment, privacy, and security (Ji & Yimin, Citation2021). It involves psychological assessment and subjective judgments of value and risk. Technology acceptance theories failed to explain such a psychological state of an individual. The interaction between ubiquity, value, and risk perception in mobile payment applications is rarely discussed. Cross-regional and cross-departmental service projects are constantly advancing, especially in the 5 G era. The scale of use depends on ubiquity and social influence, yet the theory and research in this field have been stagnant. The government needs to keep pace with the times in deepening the ICT construction and promoting policies because people with high awareness of government support are more likely to implement adoptive behavior (Kim et al., Citation2018). Government policies and measures are critical elements that influence individual behavior (Irani et al., Citation2007). Nevertheless, the non-standardized eGovernment laws at this stage still conflict with some internal regulations (Zhang, Citation2019). The applicability of policy support remains to be demonstrated.

Mini-program adoption is a series of external stimuli, perceptions, and response processes from the user’s perspective (Young, Citation2016). Demand and external factors constitute stimuli and influences that change cognition and attitude, thereby driving individuals to take subsequent behavior (Woodworth, Citation1918, Citation1958). Yet current adoption models are limited to technical explanations. Prior study has emphasized the importance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in system use, where intrinsic and extrinsic motivation represents a substantial portion of people’s experiences when involved in activities (Gerow et al., Citation2013; Khan et al., Citation2017; Malhotra et al., Citation2008). Based on the Self-Determination Theory and Motivation Theory, service quality and trust are intrinsic motivators that drive an individual’s inner motivation, whereas ubiquity and social influence are extrinsic motivators to achieve a specific goal (Davis et al., Citation1989; Deci & Ryan, Citation1985; Vallerand, Citation1997, Citation2000). By addressing the above literature gap, this work employs the extended SOR paradigm, introduces the motivators as stimuli, comprehensively examines the relationship between each stimulus and organism perception, and explores the role of government support in eGovernment implementation.

This study aims to identify the determinants from the user perspective and investigate the mechanism of GSMP adoption on WeChat and Alipay platforms in GBA cities. The construct of the empirical model provides valuable insights into the GBA’s eGovernment success, addressing current theoretical limitations. In particular, it provides evidence to solve the issues of varying quality and homogenization of mini-programs and understand the extent of trust in eGovernment. Moreover, it helps evaluate the role of government support to grasp the impact of service mini-programs on GBA. These contributions will guide the future development strategy of e-governance and smart cities in GBA.

2. Literature review

2.1. Insights from e-service quality frameworks

Service quality (SQ) plays a vital role in adopting e-services (Rifat et al., Citation2019); however, previous evidence of service quality towards eGovernment adoption is incomplete (Petter et al., Citation2008). E-service quality was regarded as the customer’s overall evaluation and judgment of the excellent service (Xu et al., Citation2013). Some theoretical models have been identified in the past and provided crucial insights (Prakash, Citation2018). E-GovQual (eGovernment Quality) introduced the reliability of measuring users’ perceived service quality and verified the significant impact of trust, efficiency, reliability, and citizen support (Papadomichelaki & Mentzas, Citation2012). The common point between E-GSQA (eGovernment Service Quality Assessment) and Hajar’s mobile government framework is to determine the service quality from the perspective of citizens, taking into account the actual quality brought by the entity supporting and network status during the service process (Hajar et al., Citation2017; Zaidi & Qteishat, Citation2012). The highlight of Hien’s model is that citizens and enterprises are regarded as customers of eGovernment, and the organization’s impact is included in the evaluation (Hien, Citation2014). EGOSQ (eGovernance Online-Service Quality) is developed using qualitative and quantitative approaches; it involves multiple levels and comprehensively discusses various service quality factors (Agrawal et al., Citation2007). Prior models focus on concerned elements and context, relying on research objectives and perspectives. From the user perspective, eGovernment service quality is defined as the extent to which users’ needs are satisfied or the degree to which service content and delivery are integrated (Lia & Shang, 2020). Due to the pros and cons of different assessments, policymakers could formulate regulations to embed SQ in public e-services to ensure the service quality of government service mini-programs and enhance the adoption (Papadomichelaki & Mentzas, Citation2012; Prakash, Citation2018).

2.2. Trust in eGovernment services

Trust in eGovernment (TR) involves complicated associations among technology, individuals, organizations, and government agencies (Alzahrani et al., Citation2018). Previous studies have linked competence, benevolence, integrity, trust in government, and trust in technology to the credibility of eGovernment (Abu-Shanab, Citation2014; Janssen et al., Citation2018; Kumar et al., Citation2018; Lian, Citation2015). Researchers categorized trust into perceptions of competence, benevolence, and integrity. Relevant elements include citizens’ perception of the government’s concern for public welfare, the ability of government to fulfill its commitments, and the professional competence and efficiency of government entity (Grimmelikhuijsen & Knies, Citation2017). Expressions of competence, benevolence, and integrity are associated with the overall evaluation of public services, which are crucial factors underpinning behaviors of intent and trust (Mayer et al., Citation1995). Integrity and benevolence have a cumulative effect on risk-taking and counterproductive behavior, whereas competence has a cumulative effect on both (Colquitt et al., Citation2007). These aspects are significantly related to behavioral outcomes. Desirable levels of competence, benevolence, and integrity in eGovernment systems guarantee the generation of trust (Gefen et al., Citation2003), suggesting a positive influence of eGovernment trust on behavior (Alzahrani et al., Citation2017; Sharma & Mishra, Citation2017).

2.3. Service availability - ubiquity

Mini-programs satisfy users’ needs anytime and anywhere. The attributes of mini-programs combined with inherent advantages of mobile payment, mobile devices, and mobile networks (Hong-Lei & Lee, Citation2017) align with the development strategy of GBA public services (iResearch Inc., Citation2019). Ubiquity represents the continuous interaction of users with wirelessly interconnected devices. It is interpreted as a synonym for ubiquitous, meaning everywhere and invisible. In e-commerce, ubiquity is defined according to different parts of the Internet, usage environment, and access points; the more significant the impact on users, the more ubiquitous it will be (Okazaki et al., Citation2012). Ubiquity allows users to receive information and perform real-time transactions anywhere. It brings value and provides users with unique functions, especially for tasks sensitive to time and location (Clarke, Citation2001). In addition, ubiquity provides users with mobile networks and functions, allowing users to access mobile payment and financial applications anytime. Related systems are no longer limited to specific locations (Junglas & Watson, Citation2003; Yan & Yang, Citation2015; Zhou, Citation2012). As the current mainstream mobile payment platforms, WeChat Pay and Alipay have the highest market share, and the attributes of ubiquity are the most salient (Cao & Niu, Citation2019), enhancing motivational beliefs and the value of customer experience (Tojib & Tsarenko, Citation2012). It relates to the user’s perception of value (Chong et al., Citation2012). Service ubiquity is a critical antecedent of willingness to use mobile services. It influences the behavior of individuals through a series of intermediary variables. Its direct influence was elaborated in the empirical model of Ltifi; ubiquity influenced the willingness to adopt mobile services of smartphones through hedonic and utility value and directly affected behavioral intention (Ltifi, Citation2018). Lee’s mobile business adoption model has suggested that ubiquitous connectivity directly influences the willingness to use and the user’s trust (Lee, Citation2005).

2.4. Social influence in the e-service context

Social influence is the extent to which an individual perceives that important others believe he or she should use the new system in an e-service context (Chen & Aklikokou, Citation2020; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). It is a vital determinant of mobile Internet, eGovernment, mobile shopping, and mobile banking adoption, significantly impacting intention to use (Liu et al., Citation2014; Venkatesh et al., Citation2012). Family, friends, and colleagues could influence an individual’s decision. In eGovernment, social influence is a factor in the extent to which citizens adopt e-services (Chen & Aklikokou, Citation2020). It is similar to subjective norms and directly determines behavioral intention (Ajzen, Citation1991; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). Due to the government’s promotion, citizens accept new technologies, social influence becomes essential, and people’s beliefs and attitudes change. These attitude changes are the general result of social influence (Alharbi et al., Citation2017; Hsu & Lu, Citation2004; John et al., Citation2018; Sharma & Mishra, Citation2017). Research findings have suggested that social influence had a positive effect on the adoption of e-services (Al-Shafi & Weerakkody, Citation2009; Lin et al., Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2014; Shaw & Sergueeva, Citation2019; Wang & Lin, Citation2011). However, several studies have obtained opposite results (Riffai et al., Citation2012; Sharma et al., Citation2018; Talukder et al., Citation2019). The adoption of mini-programs is a leading trend in the GBA society. Adopters in groups, social clubs, communities, and political associations influence each other, forming various types of social influence (Forsyth, Citation2013).

2.5. Value and risk perception from eGovernment practice

Value is an implicit standard used by individuals when making preference judgments (Sánchez-Fernández & Ángeles Iniesta-Bonillo, Citation2007). It represents an overall estimation of the chosen object, while perceived value reflects this by comparing benefits with sacrifices. Thus, perceived value indicates adopting intention (Kim et al., Citation2007). The nature of perceived value is complex and multidimensional (Sánchez-Fernández & Ángeles Iniesta-Bonillo, Citation2007). To quantify the performance of m-government in the public sector, perceived value was employed to measure the net benefit (Wang & Teo, Citation2020). The formation of user intention depended mainly on the perceived value of services (Lia & Shang, 2020). Perceived value is the component of the organism in SOR that mediates the relationship between stimulation and response (Buxbaum, Citation2016). Extant studies have revealed that perceived value has a crucial intermediary effect. It mediates the relationship between ubiquity and intention to use mobile services and the relationship between service quality and the continuous intention of citizens (Lia & Shang, 2020; Ltifi, Citation2018). GSMP is an innovative service based on a mobile payment platform. All innovations are uncertain to individuals, and uncertainty concerns the possibility of events and many options (Rogers, Citation1995). The uncertainty of behavior and environment constitutes an individual’s perceived risk (Bélanger & Carter, Citation2008), which is a subjective reality, a psychological and cognitive concept (Cano & Salzberger, Citation2017). Risk is a prerequisite for trust and creates opportunities for trust. Thus, perceived risk affects citizens’ trust and willingness to use eGovernment (Alzahrani et al., Citation2018). Technological risk, performance risk, security, and privacy are considered essential types of risk. Colesca’s research also demonstrated that risk was related to trust in eGovernment (Colesca, Citation2009). GSMPs provide services through mobile payment platforms involving online transactions, locating, information exposure, and technical issues. Perceived risk is a barrier to adopting mobile payment platforms (Cao & Niu, Citation2019; Kaur & Arora, Citation2021).

2.6. The role of government support

Government support is a crucial driver of e-services (Harfouche & Robbin, Citation2012; Mandari et al., Citation2017). It leads and facilitates the spread of information and communication technologies and significantly impacts the adoption of mobile government and mobile payments (Chen et al., Citation2019; Huang et al., Citation2021). Government support is considered a facilitative condition in which the availability of regulations, policies, and strategies could help target users to adopt specific technological innovations (Mandari & Chong, Citation2018). Reliable laws and infrastructure ensure citizens’ confidence; the higher an individual’s perceived level of government support, the more likely he or she would use online services (Hu et al., Citation2019; Nasri & Charfeddine, Citation2012). Policy, regulation, funding, and incentives from the government have a certain extent of moderating effect (Li & Atuahene-Gima, Citation2001; Petti et al., Citation2017; Zhiying & Huiyun, Citation2019). Government support significantly moderates the direct relationship between drivers and behavior (Hong et al., Citation2019); intention will be further strengthened under more favorable government policies and regulations (Lai et al., Citation2018). Policy regulation and monetary funds moderated the relationship between trust and eGovernment adoption in cloud adoption (Liang et al., Citation2017). Regarding energy-saving behaviors, government policies positively moderated attitudes and energy-saving behaviors (Hong et al., Citation2019). Kim et al. confirmed the moderating effects of financial incentives and non-financial policies on innovation adoption. Both positively moderated the relationship between perceived value and adoption of the electric vehicle, indicating that people with high perceptions of government support are more likely to implement adopting behavior (Kim et al., Citation2018).

2.7. Theoretical foundation

The GAM proposed by Shareef et al. identified key factors for eGovernment adoption at different stages of service maturity (Shareef et al., Citation2011). Later, Almaiah et al. integrated GAM and UTAUT to develop a m-government model to provide further interpretation (Almaiah et al., Citation2020). However, Dwivedi et al. argued that the original technology acceptance model was not suitable for the eGovernment environment, and proposed a Unified Model of E-Government Adoption (UMEGA), which had a high explanatory power for behavioral intentions (Dwivedi et al., Citation2017). Subsequent research modified UMEGA with trust and risk theories, highlighting the importance of citizens’ perspectives (Silas & Lizette, Citation2018). Research on mobile payment has established the effectiveness of trust, ubiquity, and government support in payment behavior, in which risk perception weakens individual willingness (Chen et al., Citation2019; Hong-Lei & Lee, Citation2017; Yan & Yang, Citation2015). On the contrary, perceived value has a positive effect on mobile payment adoption, and the effect of social influence is also supported (Cao & Niu, Citation2019; Yang et al., Citation2015). Although research on mobile payment focuses on payment scenarios, it emphasizes the evaluation and influence of risk and trust. Self-Determination Theory indicates that intrinsic motivation refers to a person’s inner motivation to do something, while extrinsic motivation refers to the performance of an activity to achieve a specific goal. In the Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation, affect, cognition, and behavior are the consequences of different motivation levels, such as global, contextual, and situational (Deci & Ryan, Citation1985; Vallerand, Citation1997, Citation2000). On this basis, service quality, trust in eGovernment, ubiquity, and social influence are the intrinsic and extrinsic motivators that constitute the stimulation in the extended SOR paradigm; value and risk perception refer to the organism, and behavioral intention is the response component. By incorporating SDT and Motivation theory, this study provides a novel perspective for model development, which considers service carriers and attributes, as well as mobile payment and eGovernment scenarios, thereby elucidating the adoption mechanisms, addressing the issues in service homogeneity, policy applicability, and conceptualization of eGovernment trust.

3. Research model and hypotheses

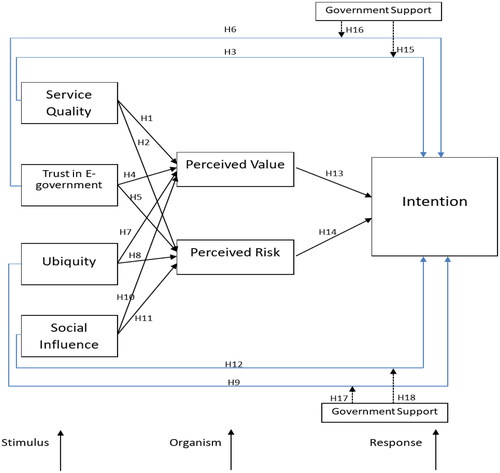

The review mentioned above establishes the foundations for the proposal of the research model (). Service quality and trust in eGovernment are introduced as intrinsic, while ubiquity and social influence are the extrinsic motivators. Both intrinsic and extrinsic motivators constitute the stimulus component in the extended SOR paradigm. Organism in SOR mediates the stimuli and response (Buxbaum, Citation2016); hence, it refers to an individual’s perceived value and perceived risk. In addition, adopting intention refers to response, which represents positive actions in adoption mechanisms (Chang et al., Citation2011). Government support acts as a regulatory variable between the stimuli factors and response for investigating the potential moderating effect in the mechanism. The conceptual model aims to explain the relationship among factors, including the direct and indirect effects on adoption behavior and the moderation effect of government support.

3.1. Impact of service quality

Service quality is essential in adopting e-services (Rifat et al., Citation2019). In addition to considering the characteristics of online services, technical environment, personalized service, security, and information are other aspects of service quality (Wang & Liao, Citation2006). High service quality leads to ideal results in e-service adoption (Xu et al., Citation2013). eGovernment involves applications of information systems and technology, and service quality is a critical determinant of system adoption (Sharma & Mishra, Citation2017), which positively influences citizens’ intention to use (Wang, Citation2008). Not only does service quality make the service experience worthwhile, but these quality components reduce perceived risk (Sweeney et al., Citation1999). If the perceived quality of eGovernment services is high enough, citizens may be willing to take reasonable risks to obtain the desired value (Rotchanakitumnuai, Citation2008). High-quality e-services facilitate citizen-government relationships and enhance perceived benefits by bridging gaps created by a lack of face-to-face interaction (Akram et al., Citation2019). Service quality significantly and positively influences the value perception of e-services, including utilitarian and hedonic value (Shih-Tse Wang, Citation2017). Thus, we hypothesize:

H1: Service Quality of GSMPs positively influences Perceived Value of users.

H2: Service Quality of GSMPs reduces Perceived Risk of users.

H3: Service Quality of GSMPs positively influences usage Intention of users.

3.2. Impact of trust in eGovernment

Citizens’ trust in government is the key to the success of eGovernment initiatives (Scott et al., Citation2016). It involves perceptions of integrity, competence, and genuine care from the government (Grimmelikhuijsen, Citation2009). Trust was the most influential predictor of intention to use (Al-Dweeri et al., Citation2018; Sharma et al., Citation2018). Suppose a citizen has high levels of trust in the government. In that case, he or she will tend to trust eGovernment and become more tolerant, attributing the negative experience to something other than a bad experience (Teo et al., Citation2009). Government service mini-programs provide a reliable online environment and service platform, reducing information leakage and privacy risks and enhancing citizens’ behavioral intentions (Wang & Lin, Citation2016). Empirical studies have shown a negative correlation between trust and perceived risk (Jayashankar et al., Citation2018). In addition, trustworthy smart government services bring value to users (Hartanti et al., Citation2021). A positive correlation has been confirmed between trust and perceived value (Jayashankar et al., Citation2018). The higher the extent of trust in eGovernment, the relative increase in the overall perception of benefit and utility; perceived value positively and significantly influences intention to use (Hartanti et al., Citation2021). These arguments lead us to postulate:

H4: Trust in eGovernment positively influences Perceived Value of users.

H5: Trust in eGovernment reduces Perceived Risk of users.

H6: Trust in eGovernment positively influences usage Intention of users.

3.3. Impact of ubiquity

Ubiquity allows users to access the network anytime and anywhere, and the use of related service systems is no longer limited to a specific location (Junglas & Watson, Citation2003). Service ubiquity is an essential antecedent of willingness to use (Lee, Citation2005) and positively impacts mobile services (Cao & Niu, Citation2019). Various mediating variables affect individuals’ behavioral intentions (Arpaci, Citation2016; Stocchi et al., Citation2019). In particular, it affects the intention of mobile services through hedonic and utility value and directly impacts behavior (Ltifi, Citation2018). Ubiquity correlates with users’ perception of value (Chong et al., Citation2012). When users believe they can use mobile services anytime and anywhere, they perceive a greater extent of utilitarian value (Nan et al., Citation2020). Since ubiquity is closely related to the adoption of mobile devices and networks, excellent and ubiquitous connectivity reduces the threat of poor signal and cyber-attacks, thereby ensuring the benefits of ubiquity (Okazaki et al., Citation2012). These arguments lead to the following:

H7: Ubiquity of GSMPs positively influences Perceived Value of users.

H8: Ubiquity of GSMPs reduces Perceived Risk of users.

H9: Ubiquity of GSMPs positively influences usage Intention of users.

3.4. Impact of social influence

Social influence is a psychosocial phenomenon (Latané & Wolf, Citation1981) that has a powerful influence on an individual’s behavior (Griskevicius et al., Citation2012) and accurately predicts the intention to perform various actions (Ajzen, Citation1991; Petrova et al., Citation2012). Social influence is the extent to which an individual considers important others think he or she should use the new system in e-services (Chen & Aklikokou, Citation2020; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). Research findings indicate that social influence positively affects e-service adoption (Lin et al., Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2014). It positively influences users’ perceived value of mobile payment services in a society with mature mobile networks and the popularization of smartphones (Lin et al., Citation2020). Research on social network behavior confirmed that social interaction ties positively affected four types of perceived values: social, information, emotional, and hedonic value (Zhang et al., Citation2017). Nevertheless, the Social Amplification of Risk theory points out that social influence amplifies and transmits risk perception (Kasperson et al., Citation1988); the more vulnerable an individual is to social influence, the higher the risk perception (Duinen et al., Citation2015). These arguments lead to:

H10: Social Influence in GBA positively influences Perceived Value of users.

H11: Social Influence in GBA positively influences Perceived Risk of users.

H12: Social Influence in GBA positively influences usage Intention of users.

3.5. Impact of perceived value

Perceived value is the preference and evaluation of citizens in the process and outcome of GSMP adoption. In the context of mobile services, it is reasonable to associate perceived value with behavioral intentions (Pihlström & Brush, Citation2008). Perceived value is an effective predictor of online personal behavior and positively impacts e-services, mobile Apps, social networks, and online consumption behaviors (Chen & Fu, Citation2018; Gao et al., Citation2021; Wu & Andrizal, Citation2021; Xie et al., Citation2021). Thus, we infer that high perceived value will facilitate willingness to employ GSMPs. In line with this reasoning, we hypothesize that:

H13: Perceived Value of users positively impacts the Intention to adopt GSMPs.

3.6. Impact of perceived risk

Risk facets are the most prominent issues in e-services adoption (Featherman & Pavlou, Citation2003). Citizens adopting government service mini-programs must consider potential uncertainties such as time, security, performance, and technological risk. They may develop doubts or even face losses. The perceived risk can negatively affect behavior under the influence of subjective or objective factors (Israel & Tiwari, Citation2011; Kaur & Arora, Citation2021), reducing their intention to adopt. In line with this reasoning, we hypothesize that:

H14: Perceived Risk of users has a negative impact on the Intention to adopt GSMPs.

3.7. Moderating effect of government support

Government support provides beneficial conditions and positively affects eGovernment adoption (Mandari & Chong, Citation2018); it guides ICT and innovative information technology (Wang et al., Citation2019). The government introduced regulations, policies, incentives, promotion, and other measures to promote eGovernment services (Mandari et al., Citation2017). From the findings of studies on individual adopting behavior (Hong et al., Citation2019; Kim et al., Citation2018), government cloud adoption (Liang et al., Citation2017), and SME performance (Petti et al., Citation2017), the moderating effect of government support has been confirmed. These arguments lead to the following:

H15: Government Support moderates the relationship between Service Quality and Intention.

H16: Government Support moderates the relationship between Trust in eGovernment and Intention.

H17: Government Support moderates the relationship between Ubiquity and Intention.

H18: Government Support moderates the relationship between Social Influence and Intention.

3.8. Mediating effect of perceived value

Perceived value fully mediates an individual’s beliefs and intention to adapt to a network environment (Kim et al., Citation2007); it is an essential mediating variable in IS adoption model (Lin et al., Citation2012). Service quality, trust in eGovernment, ubiquity, and social influence are the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that constitute the stimulus component in the proposed model (Deci & Ryan, Citation1985; Vallerand, Citation1997). They are the antecedents of perceived value and play an active role in an individual’s behavior in the eGovernment context. Perceived value refers to the organism mediating the stimuli and response in SOR (Buxbaum, Citation2016). Extant studies have indicated that perceived value mediated the relationship between intention and service quality (Li & Shang, Citation2020), trust in eGovernment (Hartanti et al., Citation2021), ubiquity (Ltifi, Citation2018), and social influence (Hai et al., Citation2019) respectively. These lead to:

H19: Perceived Value mediates between Intention and Service Quality.

H20: Perceived Value mediates between Intention and Trust in eGovernment.

H21: Perceived Value mediates between Intention and Ubiquity.

H22: Perceived Value mediates between Intention and Social Influence.

3.9. Mediating effect of perceived risk

Service quality, trust in eGovernment, ubiquity, and social influence are the intrinsic and extrinsic factors and directly affect citizens’ adoption behavior in the eGovernment context (Alharbi et al., Citation2017; Ltifi, Citation2018; Teo et al., Citation2009). However, an individual’s psychological state manifested by perceived risk from the external environment cannot be ignored because these cognitions reflect judgment and subjective feelings and directly or indirectly affect the individual’s decision-making (Bingchao et al., Citation2019). Perceived risk acts as the organism mediates the stimuli and behavior in SOR (Buxbaum, Citation2016). We infer that perceived risk plays a mediating role. These lead to:

H23: Perceived Risk mediates between Intention and Service Quality.

H24: Perceived Risk mediates between Intention and Trust in eGovernment.

H25: Perceived Risk mediates between Intention and Ubiquity.

H26: Perceived Risk mediates between Intention and Social Influence.

4. Methodology

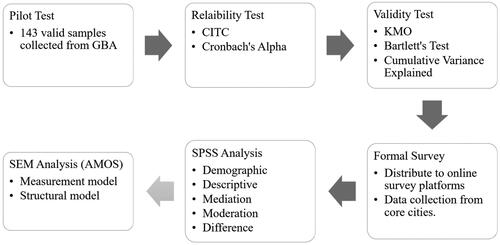

Methodology adopts an online survey approach, and the primary analysis tools include SPSS and Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) software. The Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) technique is employed to verify the research model and hypotheses. According to the «Outline of Development Plan for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area», Macau, Hong Kong, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen are defined as Core Cities, playing the role of the core engine and radiation in the GBA (State Council of China, Citation2019). The population of Core Cities is approximately 44.39 million, accounting for more than half of the GBA. Based on Core Cities’ representativeness, the sample source mainly comes from Macau, Hong Kong, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. The convenience sampling approach is employed, and the residents from the above cities are purposively invited as respondents. The measurement scales are derived from existing scales and sources as presented in . The constructs adopt a five-point Likert-scale, anchored from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 5= ‘strongly agree’. A pilot test was conducted to ensure the reliability and validity of measurement instruments, where the values of Cronbach’s alpha, CITC, KMO, and explained variances fulfilled the criterion. The formal surveys were collected for two weeks through the Tencent and WenJuanXin online survey platforms, with 609 valid samples collected. Responses have been screened for IP addresses to ensure their legitimacy and avoid duplicated answers. A sample was considered invalid if the response time was less than 4 minutes. demonstrates the flow of the overall methodology in this study.

Table 1. Measurement items of constructs.

5. Results

This section presents the statistics and Structural Equation Modelling analysis results with SPSS and AMOS software. Multiple bootstrapping approach in AMOS is employed for the estimations of mediation, while hierarchical regression models are adopted to examine the effect of moderation.

5.1. Descriptive statistics

The data in . indicates more female respondents, accounting for 51.89%. The leading age group is 20-29 years old, accounting for 58.13%, while the proportion of users over 50 is relatively low. More than 42% of the respondents are ordinary employees whose education backgrounds are mainly Bachelor, Diploma, and High school. Respondents with GSMP experience for more than four years account for 24.47%, and only 10.84% have experience of 3 to 4 years.

Table 2. Demographic information of the sample.

5.2. Measurement model

The measurement model is evaluated for internal consistency, convergent, and discriminant validity. The Cronbach’s α of eight constructs (Service Quality, Trust in eGovernment, Ubiquity, Social Influence, Perceived Value, Perceived Risk, Government Support, and Intention) ranges from 0.86 to 0.96, and the reliability test satisfies the essential criteria. Standardized factor loadings in Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) range from 0.718 to 0.946, which meets a significant level (Hulland, Citation1999). As presented in , all Composite Reliability (CR) and discriminant validity values fulfill the minimum criteria (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Measurement items of TiEG range from 0.718 to 0.813, indicating that benevolence, integrity, and competence are strong indicators of TiEG, where integrity contributes the highest factor loadings, followed by competence and benevolence. Goodness-of-fit indices are estimated with AMOS, and the most popular fit measures lead to a good model fit: χ2/df = 2.433, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.049, Standard Root Mean Residual (SRMR) = 0.034, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.874, Normed Fit Index (NFI) =0.925 (Hair et al., Citation1998; Hu & Bentler, Citation2009).

Table 3. Composite reliability & discriminant validity results.

5.3. Structural model

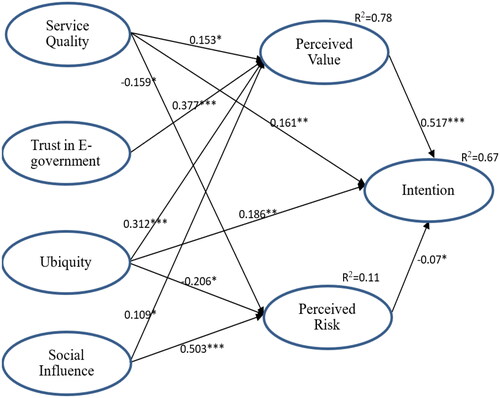

Regarding the evaluation of Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) in the structural model, the highest value of the indicators is 2.93, demonstrating no multicollinearity issue in this study (Joseph F. Hair, Citation2009). The estimates of the path coefficient, standard error, critical ratio, and p-value for the initial model are summarized in . Goodness-of-fit and modification indices (MI) meet the acceptance criterion, where χ2/df is 2.697, RMSEA is 0.053, PGFI is 0.745, and Incremental fit measures (IFI, NFI, TLI, and CFI) are between 0.926 to 0.952. Thus, the non-significant paths (Trust_in_E_government → Perceived_Risk, Trust_in_E_government → Intention, Social_Influence → Intention) are removed respectively to simplify the model in the model modification stage (Li, Citation2019).

Table 4. Initial path evaluation.

The revised path evaluation is presented in . Path coefficients of SQ to PV, IN, and PR are 0.153(t = 2.062), 0.161(t = 2.627), and -0.159 (t = −2.13), respectively. It implies that SQ promotes PV and IN but weakens PR. Likewise, UB positively influences PV and IN and negatively influences PR, where path coefficients are 0.312(t = 4.863), 0.186(t = 2.989), and −0.206 (t = −2.389). Hence hypotheses H1 to H3 and H7 to H9 are supported. TR positively impacts PV only, with a coefficient of 0.377(t = 2.979). Hypothesis H4 is supported, whereas H5 and H6 are rejected. SI positively influences both PV and PR, where coefficients are 0.109(t = 2.374) and 0.503(t = 6.823). Hypothesis H10 and H11 are supported; however, H12 is rejected. PV and PR have an opposite impact on IN, where path coefficients are 0.517(t = 6.197) and -0.07(t=-2.37). It supports hypotheses H13 and H14.

Table 5. Revised path evaluation.

All revised path evaluation estimates are significant, and goodness-of-fit meets the recommended criterion (). Therefore, the revised path diagram is the finalized structural model (). The path coefficient of PV to IN is 0.517, which is the highest in the model, followed by the coefficient of SI to PR. Independent variables SQ, TR, UB, and SI explain a high variance on PV where R2 is 0.78. However, the variance on PR is weak, where R2 is 0.11. Overall explained variance of the structural model on IN is 67%, which is acceptable.

Table 6. Model fit indices.

5.4. Mediating effect

Bootstrapping with the bias-corrected percentile method is employed to examine the mediation effect in AMOS (Effron, Citation1979; MacKinnon, Citation2008). As presented in , PR fully mediates the relationship of SQ→IN, where the indirect effect estimate is 0.011 (p = 0.012). Hypothesis H23 is supported. Since the direct effect of UB→IN is significant, PR partially mediates between UB and IN (indirect effect = 0.014, p = 0.002). Likewise, PV has partial mediation between UB and IN (indirect effect = 0.014, p = 0.002). It supports hypotheses H21 and H25.

Table 7. Estimation of mediating effect.

5.5. Moderating effect

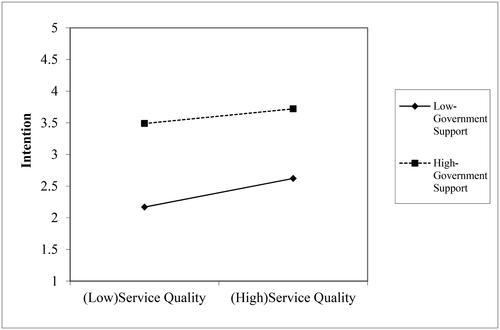

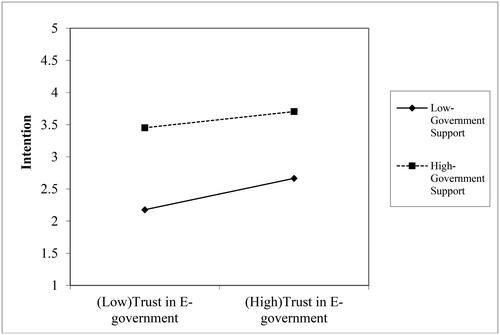

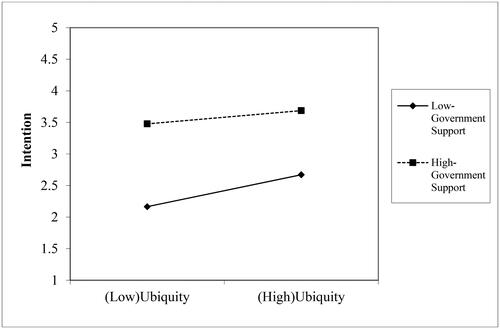

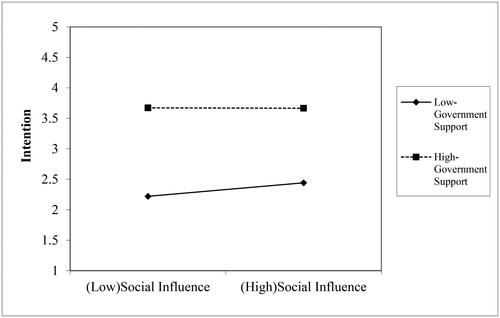

Hierarchical regression analysis is conducted in SPSS to demonstrate the moderating effect by verifying the significance of the corresponding β value, changed F value, and coefficient of determination R2 (Fairchild & MacKinnon, Citation2009; Kleinbaum et al., Citation1998). Gender and age are considered control variables and are included in Model 1 as the initial regression model (). Model 2 to model 5 examine the interactions between Government Support (GS) and Service Quality (SQ), Trust in eGovernment (TR), Ubiquity (UB), and Social Influence (SI) separately. In model 2, β of interaction item SQ x GS is -0.093, and △F is 12.448; both are significant at p < 0.001, and R2 increases to 0.629, indicating the existence of moderating effect; the moderator (Government Support) dampens the relationship between Service Quality and Intention. presents the simple slope of moderating effect, in which Service Quality generates higher Intention with low Government Support. Likewise, β values of TR x GS, UB x GS, and SI x GS are -0.098(p < 0.001), -0.0125(p < 0.001), and -0.09(p < 0.01), respectively, where the increments of △R2 and △F suggest the moderating effects of GS from model 3 to model 5. The corresponding simple slope analyses are presented in respectively. It supports hypotheses H15 to H18. Government Support is a significant moderator in the four models, which has negative interaction effects and dampens the relationships between Intention and independent variables. Among them, Government Support has the strongest moderating effect regarding the relationship of Ubiquity to Intention.

Table 8. Moderation effect estimation.

5.6. Summary of hypothesis verification

A total of 26 research hypotheses are proposed in this study, of which 18 are supported. The validation results are summarized in .

Table 9. Hypothesis summary.

5.7. Robustness checks

Additional analyses are conducted to ensure the robustness. The employed online survey platforms in this study are responsible for submitting and storing the surveys to ensure the integrity and safety of the data, thus, there is no concern about data missing. The existence of outliers will seriously affect the estimated values of statistical analysis. According to Shiffler (Citation1988), the total score of the scales is standardized, and the existence of outliers can be detected from Z values. By checking the Z values of the total score in collected surveys, all are between -3 and +3, so it is judged that there are no outliers. Multicollinearity leads to unstable estimates of individual parameters and excessive standard errors. All VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) values of the indicators range from 2.035 to 2.046, which are lower than 5.0, indicating no multicollinearity exists between the independent variables.

6. Discussion

Service quality (SQ) is the highest requirement of users in eGovernment, and it is one of the determinants of eGovernment adoption. Our findings confirmed this view and are also consistent with the study of Hu et al. (Citation2020). SQ positively affects perceived value (PV) and the GSMP intention in the adoption process. The significant effect follows the research findings of Y. Wang and Liao (Citation2006), indicating that a high level of SQ improves citizens’ PV in the G2C context and promotes the willingness to adopt. Hence, it provides insights into the limited empirical evidence between SQ and e-service acceptance (Petter et al., Citation2008). There is a significant negative correlation between SQ and perceived risk (PR), suggesting that the components of SQ reduce the risks of eGovernment (Sweeney et al., Citation1999) so that citizens can achieve ideal results and reduce the subjective expectation of suffering losses (Chen & Aklikokou, Citation2020). Indeed, GSMPs have the advantage of service attributes. The service platforms enable citizens to experience even higher service quality than traditional government services. Citizens project their offline interactions and experiences to eGovernment, and their subjective evaluations and expectations of service quality cover both online and offline.

Trust in eGovernment (TR) mainly reflects the extent of benevolence, integrity, and competence. These components are strong indicators consistent with previous studies on trust (Colquitt et al., Citation2007; Grimmelikhuijsen, Citation2009; Grimmelikhuijsen & Knies, Citation2017; Mayer et al., Citation1995; Patrick & Joao, Citation2022). It implies that GSMPs are effective, fulfill commitments, and focus on the public best interest. The effect of TR on PV is positive and robust; however, there is a gap with the expected result, of which TR has no direct effect on Intention and does not reduce PR. Several viewpoints provide insight into this issue. First, government service mini-programs are not the only channel for eGovernment services in GBA (Tianguang & Xiaojin, Citation2021); TR may not represent the overall trust. Second, the perception of local and central government trust in China is inconsistent (Liyong, Citation2014; Patrick & Joao, Citation2023), so there will be a gap in trust. Moreover, the independence of eGovernment systems in GBA cities could create measurement barriers. Nevertheless, TR delivers value to the public, highlighting PV’s significance and mediating function (Hartanti et al., Citation2021). Thus, this study helps recognize the mechanism and is different from the model proposed by Sharma and Mishra (Citation2017) and (Chatzoglou et al., Citation2015), which only consider the direct impact of trust on intention.

Ubiquity (UB) has the most significant impact on PV, followed by Intention and PR. Therefore, ubiquity is a salient determinant in eGovernment adoption. Ltifi argued that ubiquity could explain the life value of mobile services, which was considered beneficial and aligned with one’s intended needs; this viewpoint is further justified (Ltifi, Citation2018). The ubiquity of GSMPs allows users to access services anytime and anywhere. Its attributes bring great convenience, as well as incredible utilitarian and functional benefits, enabling citizens to acquire a high level of value perception, and promoting the intention to adopt. The advantages of service ubiquity come from WeChat and Alipay in nature, which effectively reduces connectivity issues and cyber-attacks during the adoption process. Compared with the findings of Cao and Niu (Citation2019), mini-programs ubiquity promotes adoption and offsets risk facets.

Social Amplification of Risk theory suggests that social influence amplifies and transmits risk perception (Kasperson et al., Citation1988); our findings support this argument. Social influence (SI) has a positive relationship with PR, which is enormously significant, suggesting that the more susceptible individuals are to social influence, the greater the risk perception (Duinen et al., Citation2015). The dissemination of information and media amplifies negative news, making it a social focus and accelerating its diffusion. The government has to pay attention to this unfavorable situation, increase transparency, and clarify issues on time. On the other hand, high SI can enhance citizens’ value perception. It is related to the improved perception of individuals in the community (Lin et al., Citation2020); Efficiency and convenience generated by service mini-programs guide users to form perceived value, and this is the process of changes in subjective feelings and values (Latané, Citation1981). The effect of SI on Intention is insignificant, and the same findings are also found in previous studies (S. K. Sharma et al., Citation2018; Talukder et al., Citation2019; Aswar et al., Citation2022). This phenomenon is similar to the studies of Venkatesh et al. (Citation2003) and (Sharma & Mishra, Citation2017); SI weakens with increasing voluntariness and gradually becomes less important to the intention over time. As mentioned above, SI indirectly influences Intention through PR. It enhances PV, while PV acts on intention as well. Our study complements the limitations of (Sharma et al., Citation2018; Talukder et al., Citation2019), of which the indirect effect of SI is discussed.

6.1. Effect of government support

Government support (GS) significantly moderates the relationship between Intention and SQ, TR, UB, and SI, with adverse effects. Various measures with government support are expected to enhance the determinants; however, the results are the opposite in this case. From the citizens’ perspective, excessive government intervention results in mandated use and inhibits citizens’ willingness to adopt; for instance, Hong Kong and Macao citizens can only access designated government services through mini-programs. Consistent with the view of Chen et al. (Citation2019), the severe intervention of the bureaucracy limits the innovation of new technologies. There is a lack of public participation in eGovernment project development. Jointly organized and co-organized service items are insufficient in GBA (Hu et al., Citation2020). Homogenization of mini-programs is not conducive to improving service quality and ubiquity. Part of eGovernment laws and regulations conflict with each other (Zhang, Citation2019), thereby weakening TR. The factors above highlight the inhibitory effect of government support.

6.2. Mediating role of organism components

Perceived value (PV) and perceived risk (PR) are integral parts of the organism. PV positively associates with the determinants, indicating that PV effectively explains intrinsic and extrinsic motivators in the SOR model. TR and UB have the highest and most significant path coefficients with PV, which implies that both are salient antecedents of perceived value and have a decisive role in promoting the value perception of citizens. PV has a high explained variance of 78% in the model. High PV brings high user intention, and its effect is strong. PV is a mediator, which partially mediates the relationship between UB and Intention. The remaining mediation hypotheses of PV are not supported. PR significantly weakens Intention, aligning with the research model of Carter et al. (Citation2016) in the United Kingdom, whereas their model in the United States is the opposite. Compared with the models of Carter et al., citizens have similar perceptions of overall risk with no significant differences in cultural norms despite the samples from different GBA cities. PR has a negative correlation with SQ and UB; their benefits significantly reduce the perceived level of risk in the adoption process. The explained variance of PR is weak and only 11%; its path coefficient with Intention is significant, but the value is low. Rifat et al. argued that PR was not crucial for eGovernment adoption behavior (Rifat et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, PR fully mediates the relationship between SQ and Intention and partially mediates the relationship between UB and Intention. Therefore, PR acts as a salient mediator in this study. We believe that the construction of the extended SOR model has comprehensively explained the impacts of independent variables on intention.

7. Conclusion

This study explored the determinants and proposed a research model based on SDT and Motivation Theory to investigate GSMP adoption mechanisms from the user’s perspective. Service quality, trust in eGovernment, ubiquity, and social influence are determinants of intention to adopt GSMPs. Service quality and trust in eGovernment refers to service experience and personal beliefs. Both acts as intrinsic motivators, while ubiquity and social influence refer to extrinsic motivators within the mechanism. Ubiquity provides unique experiences that meet individual needs; social influence is a series of social factors that drive attitude change. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivators dominate cognitive and emotional changes. In the process of internalization, individuals make judgments of value and preference, thereby generating intention through the overall estimation of benefit and risk. Service quality and ubiquity directly generate behavioral intention in addition to indirect effects. Perceived value and risk of organism act as mediators in the mechanism. Furthermore, government support plays a moderating role in which mandated use and excessive intervention dampen the influence of determinants.

Citizens’ trust in government service mini-programs is at an optimal level. WeChat and Alipay are the core mobile payment tools that provide stable platforms and support for mini-program applications. Benevolence, integrity, and competence are adequate indicators of trust. Citizens believe that mini-programs are competent, act in their best interest to fulfill their needs, keep the commitment, and do their best to help. Trust in eGovernment has no significant association with perceived risk; however, other determinants can reduce the adoption risk. Cyber-attacks, privacy disclosure, and potential internet-based fraud challenge trust. Although trust in eGovernment does not equivalently offset corresponding risks, the intrinsic stimulus motivates an individual’s decision in the context of GBA. We believe that enhancing trust will create higher utilitarian and functional values, bring more benefits to citizens, and trigger more engaging behaviors.

Policy, promotion strategy, and ICT infrastructures have all received positive reviews from GBA citizens. Under decisive intervention, public agencies have developed numerous service mini-programs to cooperate with the policy. It results in a surplus and tends to be homogenized. The overlapping of functions has weakened the attributes of ubiquity; the lack of public participation in developing service items is not conducive to improving service quality. The complexity of eGovernment laws hinders innovation, negatively influences trust, and reduces overall perception. Practitioners have to overcome and address the related issues.

The impact of GSMPs on GBA is broad and optimistic. Mini-programs provide dependable online services that satisfy citizens’ needs. Attributes of mobile payment allow access to services anytime and anywhere. The increase in overall value encourages more citizens to adopt. It results from vigorous promotion, which confirms that the government’s efforts have achieved a certain degree of public trust. Due to the gradual integration of functions and services, unnecessary duplication of development is reduced, and financial resources are saved, thereby improving the cost-effectiveness of government agencies. Core services have been classified efficiently, and the launch of cross-provincial service projects highlights future development. Since Guangdong Affairs, Guangdong Business Affairs, and Guangdong Government Affairs have become the leading service mini-programs of GBA, most of the service categories will be included. In general, service mini-programs have always played a vital role in the sustainable development stage of eGovernment in GBA.

7.1. Theoretical implications

This study integrates Self-determination and Motivation Theory and constructs a new theoretical model to explain GSMP adoption. It extends the SOR paradigm from the user’s perspective and validates a rigorous structural model. It has addressed the limitations of previous studies, such as neglected potential intermediate variables, extension of context-related factors, and excessive independent variables. The overall model’s explanatory power is ideal compared with previous mixed models (Chen & Aklikokou, Citation2020; Martins et al., Citation2014). GSMPs are designed and applied based on WeChat and Alipay. Previous eGovernment adoption models did not consider ubiquitous mobile payment features and could not comprehensively explain the adoption mechanisms. Self-determination Theory describes that human behavior is driven by autonomy, competence, and relatedness. It emphasizes that adoption behavior is self-determined and based on personal choice. Individuals are driven by intrinsic and extrinsic motivators from the environment to promote the organism’s value and risk perception, and then generate the intention to adopt. Proposed model provides strong support and better understanding for cultivating positive behaviors.

Service quality is the direct perception of access to e-government services. Citizens expect the same experience in an e-service environment as traditional face-to-face service or higher quality. They are concerned with reliability, responsiveness, and empathy (AlHadid et al., Citation2022). This work adopts a viewpoint consistent with e-GSQA and Hajar’s framework and provides evidence for the association between service quality and GSMP adoption. Ubiquity is the most salient determinant in this research model, directly promoting intention, enhancing the individual’s value perception, and reducing the overall risk perception. It describes the user’s perceived difference in mobility, portability, and accessibility. Its attribute provides citizens flexible access to government e-services anytime and anywhere, highlighting the advantages of mobile payment platforms. Gaining the trust of citizens is the key to success. At this stage, GBA citizens have a great extent of trust in eGovernment. This study explores the trust in e-government in benevolence, integrity, and competence aspects and provides evidence for the importance of the three indicators. Compared with the simple investigation of trust in government and trust in the Internet, the public interests, welfare, and citizens’ actual needs are reflected more concretely. It should be noted that according to the Social Amplification of Risk theory, the more vulnerable an individual is to social influence, the higher the perceived risk. Performance, efficiency, security, and privacy risk issues will be magnified through societal impact. This negative amplification effect will inhibit citizens’ attitudes towards service mini-programs. It provides unique insights and perspectives for social influence.

Value and risk perception are introduced as intermediaries to reveal the adoption mechanism more clearly. The empirical results suggest that there are some trade-offs between value and risk. The mediating role of both deserves attention. Value perception has high explanatory power for service quality, trust in eGovernment, ubiquity, and social influence. High-value perception promotes intention significantly, whereas risk perception negatively influences intention. In addition, government support has not been included or valued in previous e-government studies in GBA. Nevertheless, eGovernment policies, regulations, and incentives receive positive responses. Government support plays a regulatory role in GSMP adoption. We suggest that local governments’ efforts are widely recognized in GBA; simultaneously, excessive restrictions and mandatory use may weaken the effects of determinants towards adoption.

7.2. Managerial implications

High-quality e-services are standard expectations of the public. Homogenization, malfunctions, and latency are barriers to quality perception. Policymakers and practitioners should explore the scope of reform and future innovation from multiple perspectives. Constructing standards for functions, performance, stability, and traffic can optimize various service mini-programs to achieve a consistent level. More intelligent and systematical interfaces in WeChat and Alipay will provide reasonable configuration, managerial implications classification, and searching capabilities. The continuous strengthening of 5 G ICT construction can directly promote the connection between background applications and core systems, as well as the processing efficiency of cloud data. Corresponding policy support from Bay Area governments is warranted. In addition to satisfying service quality, building trust towards e-governance is the key to success in GBA. Public participation and increased policy transparency benefit policymakers, allowing development teams to understand citizens’ needs better. Government leaders are responsible for explaining specific routes and timelines to society, clarifying false information early, and promptly responding to online rumors and misleading information, ensuring social cohesion and public confidence. Mini-programs, mobile APPs, and portals seamlessly provide high-quality government e-services. Diversified channels and service access points increase public choices. Smart cities promote adoption and satisfy the needs of all ages and occupations. At this stage, specific issues have to be further addressed. For instance, to identify accessibility barriers for people with disabilities and provide an innovative solution. Provincial and co-organized service projects could be optimized to promote the integration of public services in GBA cities. In addition, the revision and adjustment of e-governance laws and regulations are necessary to fulfill the requirements of e-services. Guangdong-Macao In-Depth Cooperation Zone in Heng Qin is serving as a pilot for exploration and innovation; therefore, there will be more opportunities and challenges in smart city construction shortly.

7.3. Limitations and future research

GSMPs are not the only channel to access government e-services. We focused on several specified service mini-programs in GBA; however, mobile apps and web portals were not included. It limited the generalizability of findings. The survey considered the data collected from adopters, while responses from non-adopters were not employed. Their comments and opinions could help to formulate strategies for future research and foster the popularity of GSMPs. Researchers could consider including demographic factors as moderators to conduct further analysis. The research model could benefit from additional predictors and provide advanced explanations by extending the model for adopters. Developing independent models for GBA cities could identify the issues with model comparison and provide more specific support for improving integrated services and cross-regional cooperation.

Authorship contribution statement

Lai Chi Meng Patrick: Conceptualization, Methodology, Analysis, Writing.

João Alexandre Lobo Marques: Review, Editing, Supervision.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lai ChiMeng Patrick

Dr. Lai ChiMeng Patrick holds a PhD in Government Studies from the University of Saint Joseph Macau. He is a research scholar with 25 years of professional experience in public institutions. His research focuses on Digital Governance, Smart City Innovation, Enterprise Management, Knowledge Management, Smart Corrections, and Information System Management. To his credit, he has published scientific papers and speeches at international conferences, academic journals, forums and seminars, specializing at data analysis and structural equation modeling.

João Alexandre Lobo Marques

Professor João Alexandre Lobo Marques is the Department Head of Business Administration and Founder of the Laboratory of Applied Neurosciences at the University of Saint Joseph Macau. He holds a Ph.D. in Engineering. His research areas include Neuroscience, Business Analytics, Big Data Applications, Digital Signal Processing, Bioengineering, and Deep Learning. He has extensive experience in Project Management, Artificial Intelligence, Bioengineering, and Applied Computer Science. He has published numerous books and research papers in various reputed journals.

References

- Abu-Shanab, E. (2014). Antecedents of trust in e-government services: An empirical test in Jordan. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 8(4), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-08-2013-0027

- Agrawal, A., Shah, P., & Wadhwa, V. (2007). EGOSQ - users’ assessment of e-Governance online-services: A quality measurement instrumentation. In International Conference on E-Governance, pp. 231–244.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Al-Dweeri, R. M., Moreno, A. R., Javier, F., Montes, L., Obeidat, M. Z., & Al-Dwairi, K. M. (2018). The effect of e-service quality on Jordanian student’s e-loyalty: An empirical study in online retailing. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 119(4), 902–923. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-12-2017-0598

- Almaiah, M. A., Al-Khasawneh, A., Althunibat, A., & Khawatreh, S. (2020). Mobile government adoption model based on combining GAM and UTAUT to explain factors according to adoption of mobile government services. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM), 14(03), 199–225. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v14i03.11264

- Al-Shafi, S., & Weerakkody, V. (2009). Understanding citizens’ behavioural intention in the adoption of e-government services in the state of Qatar. In 17th European Conference on Information Systems, ECIS 2009.

- AlHadid, I., Abu-Taieh, E., Alkhawaldeh, R. S., Khwaldeh, S., Masa’deh, R., Kaabneh, K., & Alrowwad, A. (2022). Predictors for e-government adoption of SANAD app services integrating UTAUT, TPB, TAM, trust, and perceived risk. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148281

- Alharbi, N., Papadaki, M., & Dowland, P. (2017). The impact of security and its antecedents in behaviour intention of using e-government services. Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(6), 620–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2016.1269198

- Alzahrani, L., Al-Karaghouli, W., & Weerakkody, V. (2017). Analysing the critical factors influencing trust in e-government adoption from citizens’ perspective: A systematic review and a conceptual framework. International Business Review, 26(1), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.06.004

- Alzahrani, L., Al-Karaghouli, W., & Weerakkody, V. (2018). Investigating the impact of citizens’ trust toward the successful adoption of e-government: A multigroup analysis of gender, age, and internet experience. Information Systems Management, 35(2), 124–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2018.1440730

- Arpaci, I. (2016). Understanding and predicting students’ intention to use mobile cloud storage services. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.067

- Aswar, K., Ermawati, E., Juliyanto, W., Andreas, A., & Wiguna, M. (2022). Adoption of e-government by Indonesian state universities: An application of technology acceptance model. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 20(1), 396–406. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.20(1).2022.32

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Bélanger, F., & Carter, L. (2008). Trust and risk in e-government adoption. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 17(2), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2007.12.002

- Bingchao, Z., Da, S., & Ruining, L. (2019). Research on the relationship between risk perception, government trust and the willingness of local residents to participate in the construction of unique town. Journal of Yunnan Minzu University (Social Sciences), 36(4), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.I26.1.78

- Bureau, Guangdong Province Government Service Data. (2021). Guangdong Province Public Data Management Measures., Pub. L. No. 290. http://zfsg.gd.gov.cn.

- Buxbaum, O. (2016). The S-O-R-model. In Key insights into basic mechanisms of mental activity (pp. 7–9). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29467-4_2

- Cano, S., & Salzberger, T. (2017). Measuring risk perception. In G. Emilien, R. Weitkunat, & F. Lüdicke (Eds.), Consumer perception of product risks and benefits (pp. 191–200). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50530-5_10

- Cao, Q., & Niu, X. (2019). Integrating context-awareness and UTAUT to explain Alipay user adoption. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 69, 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2018.09.004

- Carter, L., Weerakkody, V., Phillips, B., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2016). Citizen adoption of e-government services: Exploring citizen perceptions of online services in the United States and United Kingdom. Information Systems Management, 33(2), 124–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2016.1155948

- Center for Digital Governance, S., School of Government, S. Y.-S. U., Center for Chinese Administration Research, S., & Tencent Research Institute. (2021). Mobile government report 2021—Mini program era and mobile government 3.0.

- Chang, H.-J., Eckman, M., & Yan, R.-N. (2011). Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model to the retail environment: The role of hedonic motivation in impulse buying behavior. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 21(3), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2011.578798

- Chatzoglou, P., Chatzoudes, D., & Symeonidis, S. (2015). S135 factors affecting the intention to use e-Government services. In Proceedings of the Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (Vol. 5, pp. 1489–1498).

- Chen, J. H., & Fu, J.-R. (2018). On the effects of perceived value in the mobile moment. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 27, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2017.12.009

- Chen, L., & Aklikokou, A. K. (2020). Determinants of e-government adoption: Testing the mediating effects of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. International Journal of Public Administration, 43(10), 850–865. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1660989

- Chen, W., Chen, C., & Chen, W. (2019). Drivers of mobile payment acceptance in China: An empirical investigation. Information, 10(12), 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/info10120384

- Chong, X., Zhang, J., Lai, K.-K., & Nie, L. (2012). An empirical analysis of mobile internet acceptance from a value-based view. International Journal of Mobile Communications, 10(5), 536–557. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMC.2012.048886

- Clarke, I. (2001). Emerging value propositions for m-commerce. Journal of Business Strategies, 18(2), 133–148.

- Colesca, S. E. (2009). Understanding trust in e-government. Economics of Engineering Decisions, 63(3), 7–15.

- Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 909–927. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.909

- MacKinnon, D. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Routledge.

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Perspectives in social psychology. Plenum Press.

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Janssen, M., Lal, B., Williams, M. D., & Clement, M. (2017). An empirical validation of a unified model of electronic government adoption (UMEGA). Government Information Quarterly, 34(2), 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.03.001

- Effron, B. (1979). Bootstrap methods: Another look at the Jackknife. The Annals of Statistics, 7(1), 1–26.

- Fairchild, A. J., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2009). A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 10(2), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-008-0109-6

- Featherman, M. S., & Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk perspective. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 59(4), 451–474.), https://doi.org/10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00111-3

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3151312 https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Forsyth, D. R. (2013). Social influence and group behavior. In I. B. Weiner (Ed.), Handbook of psychology, second edition. Volume 5. Personality and social psychology II (pp. 305–328). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Gao, Y., Wang, J., & Liu, C. (2021). Social media’s effect on fitness behavior intention: Perceived value as a mediator. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 49(6), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.10300

- Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51–90. https://doi.org/10.1021/es60170a601

- Gerow, J. E., Ayyagari, R., Thatcher, J. B., & Roth, P. L. (2013). Can we have fun @ work? The role of intrinsic motivation for utilitarian systems. European Journal of Information Systems, 22(3), 360–380.), https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2012.25

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2009). Do transparent government agencies strengthen trust? Information Polity, 14(3), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-2009-0175

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S., & Knies, E. (2017). Validating a scale for citizen trust in government organizations. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 83(3), 583–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852315585950

- Griskevicius, V., Simpson, J. A., Durante, K. M., Kim, J. S., & Cantu, S. M. (2012). Evolution, social influence, and sex ratio. In D. T. Kenrick, N. J. Goldstein, & S. L. Braver (Eds.), Six degrees of social influence : Science, application, and the psychology of Robert Cialdini (pp. 79–89). Oxford University Press.

- Hai, Z., Shun-Bo, Y., & Hui, D. (2019). Influencing factors of mobile government app users’ intention based on S-O-R theory. Information Science, 37(6), 126–132.

- Hair, F., Joseph, J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. A global perspective. Prentice Hall. https://doi.org/10.2307/1266874

- Hajar, S., Al-Hubaishi, S., Zamberi, A., & Hussain, M. (2017). Exploring mobile government from the service quality perspective. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 30(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-01-2016-0004

- Harfouche, A., & Robbin, A. (2012). Inhibitors and enablers of public e-services in Lebanon. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 24(3), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.4018/joeuc.2012070103

- Hartanti, F. T., Abawajy, J. H., Chowdhury, M., Shalannanda, W., & Hartanti, F. T. (2021). Citizens’ trust measurement in smart government services. IEEE Access, 9, 150663–150676. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3124206

- Hien, N. M. (2014). A study on evaluation of e-government service qaulity. International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering, 8(1), 16–19.

- Hong, J., She, Y., Wang, S., & Dora, M. (2019). Impact of psychological factors on energy-saving behavior: Moderating role of government subsidy policy. Journal of Cleaner Production, (232), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.321

- Hong-Lei, M., & Lee, Y.-C. (2017). Examining the influencing factors of third-party mobile payment adoption: A comparative study of Alipay and WeChat Pay. The Journal of Information Systems, 26(4), 247–284. https://doi.org/10.5859/KAIS.2017.26.4.247

- Hsu, C.-L., & Lu, H.-P. (2004). Why do people play on-line games? An extended TAM with social influences and flow experience. Information & Management, 41(7), 853–868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.08.014

- Hu, G., Liu, J., & Wu, X. (2020). Report of e-government e-services capability index (1st ed.). China Social Science Press.

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (2009). Structural equation modeling: A multidisciplinary journal cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hu, Z., Ding, S., Li, S., Chen, L., & Yang, S. (2019). Adoption intention of Fintech services for bank users: An empirical examination with an extended technology acceptance model. Symmetry, 11(3), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11030340

- Huang, Y., Li, X., & Zhang, G. (2021). The impact of technology perception and government support on e-commerce sales behavior of farmer cooperatives: Evidence from Liaoning Province, China. SAGE Open, 11(2), 215824402110156. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211015672

- Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902)20:2<195::AID-SMJ13>3.0.CO;2-7

- Irani, Z., Love, P. E. D., & Montazemi, A. (2007). e-Government: Past, present and future. European Journal of Information Systems, 16(2), 103–105. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000678

- iResearch Global. (2019). iResearch China’s third-party mobile payment structure in Q2. http://www.iresearchchina.com/content/details7_58033.html

- iResearch Inc. (2019). WeChat mini program market report 2019. www.iresearch.com.cn