?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

People migrate to take advantage of the opportunities in developed countries. They also seek to improve the lives of the families they have left behind. This thought is actualized through the international remittances the migrants send back home. When individuals receive international remittances, they make expenditure decisions, which are influenced by several factors including restrictions attached to the remittance. By incorporating the free balance concept into remittance studies, the study sought to analyze the effects of restricted and unrestricted nature of international remittances on expenditure decisions in Kumasi. Most remittance studies in Ghana have not included the restrictions on international remittances in their research; hence, including them in the study broadens the understanding of remittance utilization in Ghana. The study relied on pragmatism as the philosophical underpinning and selected an inductive approach as the research approach. The research design was the explanatory design. The study employs the random sampling method to select the remittance recipients as the study’s respondents. The study gathered primary and secondary data. The primary data collection was made through a field-based questionnaire administration. A semi-structured questionnaire was selected to help the researcher narrow down some areas or topics to address. The source of secondary data was obtained largely from financial institutions, research journals, and books. With a calculated sample size of 712, at a 0.05 margin of error from total respondents of 2760, the study had a response rate of 96.77%. The findings revealed that the majority of remittances (58.02%) received came with no instructions. Most of the instructions on the restricted remittances were related to family support. The use of international remittances influences the subjective well-being of recipients of international remittances. The study has shed light on the effects of the restricted and unrestricted nature of international remittances on expenditure decisions in Kumasi. The findings indicate that unrestricted remittances have a more significant impact on the subjective well-being of the recipients. The study has also highlighted the need for policymakers and remittance service providers to develop policies and products that cater to the needs of the recipients.

IMPACT STATEMENT

This study explores the impact of international remittances on individuals and communities, focusing on the use of these funds by international migrants. The paper highlights the potential for remittances to transform lives and shape economies, enabling access to education, healthcare, and better living conditions. The research also highlights the role of social protection measures in assisting families during economic challenges. The study focuses on both restricted and unrestricted remittances, revealing how restrictions and instructions affect spending within families and communities. The findings are relevant to researchers, policymakers, and those interested in global development. The study emphasizes the importance of understanding the role of external migration and overseas remittances in an era of global mobility, highlighting the potential for positive change through international remittances.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Today, millions of people from developing countries have left their homes in search of better job opportunities and to send money to support the needs of their family members in education, purchases of clothes, food, and other daily needs. Currently, migrants make up 3.0% of world population (United Nations, Citation2017) and the remittances they send create welfare in receiving countries (Jena, Citation2015). These international remittance flows to developing countries are larger than Official Development Assistance (World Bank, Citation2017).

Though there are two types of remittances, -internal and international remittances- the type of remittance that has the biggest influence on household consumption is international remittance (Prabal & Dilip, Citation2012). International remittances are financial inflows arising from the cross-border movement of nationals of a country and involve the transfer of money and goods sent by migrant workers to their country of origin (Castles et al., Citation2013; Clemens & McKenzie, Citation2014).

During the past decades, international remittances have not only grown in importance but have also remained resilient and stable compared to other sources of foreign exchange. For example, in Sub-Saharan African countries, international remittances have overtaken several traditionally important international financial flows including but not limited to Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Official Development Assistance in some developing countries (Prabal & Dilip, Citation2012; Yang, Citation2011). In 2010, developing countries received more than 325 billion dollars in remittances (World Bank, Citation2017).

In 2020, remittances to low- and middle-income countries recorded a modest 1.7% decline to US $549 billion. According to the World Bank (Citation2021), the flow of remittances to these countries was projected to reach US $589 billion. This indicates an increase of about 7.3% in remittances to these countries. This period presented the strongest growth since 2018. The actual remittances to low- and middle-income countries reached US $605 billion in 2021 (IFAD, Citation2021). That’s a growth of more than 8 per cent compared to 2020 and it is above the initial projections. presents the estimates and projections of remittance to low- and middle-income countries.

Table 1. Estimates and projections of remittance flows to low- and middle-income regions.

A significant proportion of these remittance transfers happened at the household level when migrant workers send money to their families and friends living in their home countries (Prabal & Dilip, Citation2012). In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries in 2020 demonstrated remarkable resilience, experiencing a smaller decline than previously projected.

The amount and the potential use of remittance income are often decided upon jointly by the sender and the recipient (Prabal & Dilip, Citation2012). Unlike earned (and some forms of unearned) income, the recipients often do not have the full discretion to spend the remitted money in an unrestricted way (Adams, Citation2010). In many cases, remittance income is tied to specific uses (Prabal & Dilip, Citation2012). Nevertheless, not all remittance payments may be tied to specific uses and the recipient may treat the money in the same way as any unrestricted transfer income like gifts and pensions (Mahapatro et al., Citation2017). There are also instances where recipients ignore the instructions that come with the remittances (Prabal & Dilip, Citation2012). How do recipients make expenditure decisions on international remittances they receive? The authors argue that there is a need to separate restricted remittance from unrestricted remittances as the decision-making on these two differs fundamentally. With restricted remittance, the sender attaches the instructions. But if the remittances come with no instructions, who then makes the decision on the private international remittance received? Regardless of the importance of instruction on remittances, research on the utilization of remittances by households has received little attention from researchers in sub-Saharan Africa. The purpose of this research is to explore how households in Ghana make expenditure decisions on restricted and unrestricted international remittances. The authors argue that understanding how remittance income is utilized by households is important because it has the potential to significantly impact the economic welfare of receiving households and the country as a whole. Furthermore, the decision-making process of how to allocate remittance income is an important factor that can influence the development and implementation of policies aimed at supporting the growth and stability of remittance flows. The relevance of this research lies in its contribution to the limited literature on how remittance income is utilized by households in Sub-Saharan African countries. This is particularly important because international remittances have become a significant source of income for many developing countries, including Ghana. Additionally, remittances have been shown to contribute significantly to poverty reduction, improved access to education and healthcare, and increased investment in small businesses. This paper discusses the expenditure decisions on restricted and unrestricted remittances received by households in Ghana.

2. Literature review

In the last ten years, remittance study has gained traction, addressing a broad variety of issues such as the formalisation of money transfer transfers, the lowering of remittance transaction fees, the effects of money transfers on social inequalities, the utilisation of remittances for investment or consumerism, the externalisation of remittance expenditure, and the social impacts on the family (Kakhkharov et al., Citation2020; Rahman & Fee, Citation2012; Sunny et al., Citation2020; Wasti, Citation2017).

Remittances are usually seen to be beneficial to society. Moreover, there appears to be little question that remittances constitute a significant income source with socioeconomic advantages for those families that receive them. According to household-level research (see Le & Nguyen, Citation2019; Szabo et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2021), money received as remittances is spent by receivers in 4 primary ways: consumption (encompassing healthcare and education expenditures), accommodation, land acquisition, as well as productive investment. Remittances are monies remitted home by nationals who live abroad in the context of this research.

Remittance flows are steadier than capital flows, and they are countercyclical, rising during recessions or just after natural disasters while private capital flows fall. They are frequently a financial lifesaver to the impoverished in nations beset by political unrest. According to the World Bank, they accounted for around 31 percent of GDP in Haiti in 2017, and more over 70 percent of GDP in some regions of Somalia in 2006 (Ratha & Mohapatra, Citation2007; Uprasen, Citation2018).

During the financial meltdown, remittances from source nations including the United States and Western European countries proven to be robust. The downturn reduced migrants’ salaries, but many attempted to compensate by decreasing consumption and rental costs. People impacted by the crisis found work in different fields. Whereas the crisis limited new immigration, it also inhibited return migration since migrants were afraid of being denied re-entry into the host nation (see Kim, Citation2013; Nahar & Arshad, Citation2017). Therefore, even throughout the worldwide financial crisis, the numbers of migrants thus remittances—continued to climb, and in particular in recent years inside the face of wars and natural catastrophes including hurricanes and tsunamis (Ratha, Citation2014).

Despite COVID-19, remittance flows remained relatively resilient in 2020, declining at a slower rate than earlier anticipated. Officially registered remittance flows to developing countries totalled $540 billion in 2020, only 1.6% less than the $548 billion amount in 2019 (Kunwar, Citation2021). The drop in reported remittance transfers in 2020 was less than that experienced throughout the global economic crisis of 2009 (4.8%). It was also significantly smaller than the drop in FDI flows to developing countries, that plummeted by more than 30% in 2020 disregarding flows to China. Consequently, remittances to developing countries will exceed the total of FDI ($259 billion) and ODA ($179 billion) in 2020 (World Bank, Citation2021).

Though numbers on foreign remittance flows to Ghana are frequently debated, World Bank data from 2014 reveal that the overall annual payments flow to the country via legitimate channels was around $2 billion. This number will have more than quadrupled by 2020. Remittances have a number of beneficial socioeconomic consequences in Ghana. For example, foreign exchange through remittances contributes to the reduction of the fiscal deficit. Remittances have an influence on the Ghanaian economy via home investment. The majority of overseas financial flows to Ghana are utilised for consumption and ongoing expenses (Quartey & Adamba, Citation2015). Remittances contributed by hometown families and single migrants are utilised to fund community projects at the local level (Teye et al., Citation2016).

Remittances that households receive come restricted or unrestricted. A remittance is restricted when the sender adds instruction on the use of the remittance. An unrestricted remittance is remittance households receive with no instructions on its utilization. The households determine how they use the remittance. There exists a semi restricted remittance where there are instructions on some portions of the monies with the other half being unrestricted. Regardless of the level of restriction the recipient household decides whether to be bound by the restriction or not as they have the will to decide outside the restriction once they receive the money. It is in the absence of any restriction and excess after doing the restricted duty that the household can have a free balance.

With the issue of restrictions inherent in expenditure decisions, researchers interested in analysing expenditures of households do need to include the ‘free balance’ of the budget. The free balance essentially discusses how much money is available for use after meeting all obligations. Such funds are not immediately disposable by the household. Only unrestricted funds can be disposable. The free balance concept was developed to explain the amount of money potentially available for new investments for districts assemblies. Kroes (Citation2005) defines free balance as that part of the budget which is still disposable within the budget period by the district authority, and which is not yet restricted by (legal) obligations such as essential administration tasks, necessary maintenance and repairs, contracts etc. Within the context of this study, the free balance is the money left after the recipient has undertaken all obligations required.

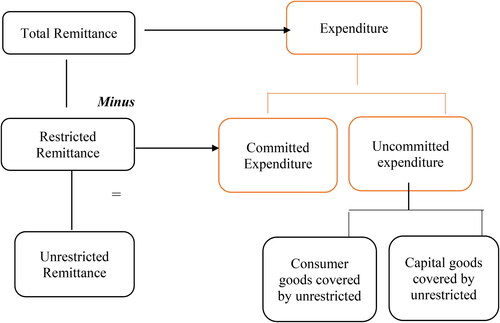

The ‘free balance’ of a household budget is the uncommitted remittance received by the household. As shown in , the unrestricted remittance is the result of subtracting restricted remittance from total remittance. The recipient of the unrestricted remittance which becomes the free balance can use the money at his or her own discretion for the provision of goods and services or capital goods.

Regardless of the restrictions on the remittance or not, the remittance is spent on consumer goods or capital goods. The study conceptualizes what consumer goods or capital goods are below.

2.1. Consumer goods

Generally, consumer goods are conceptualized as goods that directly satisfy the wants of the consumer. They are goods used for consumption. In the context of the study, consumer goods are considered final goods, as the individual does not seek to make money out of such goods. The consumer goods include food, clothing and footwear, health, transport, culture and schooling entertainment. It is expected that individuals in different socioeconomic class will treat these various consumer goods differently.

2.2. Capital goods

The study categorizes capital goods as goods an individual spends on to increase his or her income level. This can be in the form of agricultural capital goods such as tractors, machetes, plows and related materials. Capital goods can be in the form of spending the money in retailing a particular good ranging from small market stores to relatively large manufacturing facilities (Levando, Citation2020). Education is conceptualized as capital good since education offers the chance for social mobility and people in developing countries attend schools mostly for economic success. Although the general discussion of consumer and capital goods are sometimes treated as stand-alone, the study recognized all utilization of the international remittances by households as expenditure.

Petreski et al. (Citation2014) intended to study how the employment status of Macedonian adolescents varied according to their remittance-receiving status in the nation. Petreski et al. (Citation2014) addressed the possible endogeneity of remittances with regard to self-employment status using the Development on the Move (DotM) 2008 Remittance Survey and the Instrumental Variables (IV) technique. The 2008 DotM Remittance Survey included 1,211 families. Because the study was done just before the start of the global financial crisis, it was thought that the relationships analysed were unaffected by the crisis. To address the potential endogeneity of remittances with regard to self-employment status, the instrumental variables technique was adopted. There are two instrumental factors that impact remittances but not the choice to self-employ, except through remittances: a non-economic reason to move and the existence of migrants’ networks. Furthermore, Petreski et al. (Citation2014) used the Roodman’s Conditional Mixed- Process (CMP) estimator to overcome some of the constraints of IV estimation. Petreski et al. (Citation2014) discovered that adolescents in remittance-receiving homes had a much higher likelihood of starting their own business, ranging between 28 and 33 percent, as compared to non-young or non-receiving counterparts. The remittance was more likely to be spent on consumption by the elder members of the household.

Vogel and Korinek (Citation2012) investigated the usage of remittances for educational expenses for children. Vogel and Korinek (Citation2012) demonstrated the migration-development link through the use of household level data from the Nepal Living Standards Survey (NLSS II, 2003-04) to distinguish remittance impacts from general household income effects. The Nepal Living Standards Survey (NLSS II, 2003-04) is based on the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Survey methodology and includes employment, health, fertility, education, consumption patterns, migration, and remittances. Six geographic strata of the country were chosen for the NLSS II. Vogel and Korinek (Citation2012) pulled from these families to form a sample of all households with at least one kid enrolled in school in the previous year. Vogel and Korinek (Citation2012) discovered that remittances were spent in ways that aided the education of the following generation. The findings also highlighted constraints, such as remittance dollars being allocated for education that is not for everyone, since there was a higher expenditure on males’ education compared to girls’ education.

Adams and Cuecuecha (Citation2013) used the 2005–06 Ghana Living Standards Survey to find that households that received remittances spent more on health, education, and housing at the margin. Despite spending more on the three factors, families also spent on consumption items such as food. As discussed in this sub-section, households that receive international remittance tend to consume and invest the remittance based on the needs of the households. For the households, the plan appears to consume some of the remittance but not forgetting to invest the rest in areas of needs as found out in Mexico (Alcaraz et al., Citation2012) and Nepal (Vogel & Korinek, Citation2012). The findings from Petreski et al. (Citation2014) suggest that the age composition of household members could have a significant impact on remittance expenditure decisions. Specifically, younger household members tend to allocate remittance income towards investments, while older household members tend to spend more on consumption. This underscores the importance of understanding intra-household dynamics and preferences when examining the impact of remittances on household welfare and development outcomes. Having established that the use of remittances is not strict and relies on several factors, including the economic standing of households, the study discusses the use of remittances in the context of Ghana.

3. Study setting

3.1. Study setting and research participants

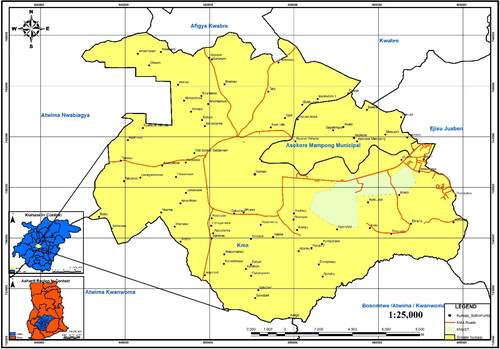

Kumasi is the study area. Being one of the administrative districts in the Ashanti region, the Kumasi metropolis was until 1995 referred to as the Kumasi City Council with its infamous greenery and well-planned layout according it the accolade of the ‘Garden City of West Africa’ as is widely known. The political geography of the city positions it between latitude 6° 41’ 18.53" N and Longitude -1° 37’ 27.95" W.

The selection of the Kumasi Metropolis as the geographic study area for this research is based on careful consideration of several factors. Firstly, the Ashanti region, of which Kumasi is a major city, has been identified as one of the top three regions in Ghana with the highest levels of international migration (Teye et al., Citation2016). Secondly, Kumasi is the second most populous city in Ghana (Ackaah & Aidoo, Citation2020), and therefore a significant recipient of international remittances sent to the Ashanti region. Finally, previous research on international remittances in the Kumasi Metropolis has focused primarily on channels and usage patterns (Ahinful et al., Citation2013), with little or no attention paid to the potential barriers and restrictions on remittance flows. These factors make Kumasi a particularly relevant and compelling case study for our investigation into the impact of regulations on international remittances.

Since the study sought answers to what people spend their private international remittances on (with relation to consumer goods and capital goods), the remittance receivers were the primary unit of inquiry because they mirrored the study’s aims. The remittance recipients were individuals that have received international remittance at least once between January 2019 and December 2019 ().

3.2. Research design

This paper forms part of a larger, original research that sought to explore the relationship between socioeconomic status of international remittance recipients and expenditure decisions. The selected research design for the study was the mixed-method research design. The choice of the mixed-method research design was influenced by the idea that combining qualitative and quantitative data is prudent in uncovering ideas and insights and allowing the consideration of several aspects of the phenomenon under study as widely acknowledged in literature (Creswell, Citation2009; Creswell, Citation2012). Also, the mixed-method research design was to ensure complementarity. The mixed-method design provided the option for qualitative and quantitative methods to be used to quantify the expenditure decisions of restricted and unrestricted remittances and explain the reasoning behind such expenditure decisions. The use of the mixed-method design was to increase the interpretability, relevance, constructs and inquiry validity by getting the most out of the quantitative and qualitative methods.

3.3. Sampling procedures

Participants of the study were men and women drawn from the 2760 recipients who had received remittances between January 2018 and December 2018 in Kumasi. With a sample size of 712, the researcher received 689 responses. Thus, there was a non-response of 23. Consequently, the response rate for the study was 96.77%. For several authors, a 60% response rate should be the goal for most researchers (see Baruch, Citation1999; Erdman et al., Citation2016). Consequently, the response rate for the study was fit for analysis.

Concerning the sample size determination, the study used the sampling model: for each of the stratum. For the first stratum, 333 recipients were sampled at 0.05 margin of error from respondents of 1996 and a 95% confidence level. Concerning the second stratum, 232 recipients have been sampled at 0.05 margin of error from respondents of 533 and a 95% confidence level. At the third stratum, 147 recipients were sampled at 0.05 margin of error from respondents of 231 and a 95% confidence level. In total, 712 respondents were to be sampled at 0.05 margin of error from total respondents of 2760. A confidence interval is a set of numbers that researchers can use to capture the true population value a given percentage of the time. The author chose 95 percent to measure the precision or correctness of the predicted statistics based on the variability of the data.

Concerning the remittance recipients, the study employed the probability sampling techniques. The simple random sampling method which is a type of probability sampling (Kemper et al., Citation2003) was employed to select the remittance recipients as the study’s respondents. The selection of the remittance recipients involved a three-step process. First, the files (which included names and locations) of the recipients of remittances were obtained from the financial institutions. Second, the simple random sampling (using random number table) was employed to randomly select the required number of respondents for the study. Third, the remittance recipients were contacted to answer questions from a semi-structured questionnaire. The questionnaire captured the socioeconomic background of respondents, restrictions on remittances, the decision-making on the use of remittances, and the use of international remittances.

3.4. Data collection methods and research instruments

To gather data on the restricted and unrestricted international remittances received, the researchers set up a semi-structured questionnaire. Study participants were contacted to answer the questionnaire. Consent were gained from the study participants before they responded to the questionnaire. This consent was attained in addition to ethical clearance obtained from the management of the financial institutions.

3.5. Data analysis methods and procedure

The household data collected for this study was subjected to rigorous statistical analysis using a combination of correlation and regression techniques in SPSS and Microsoft Excel. To ensure accuracy and consistency, the responses from the closed-ended questions were cross-referenced with the answers provided in the open-ended questions. The study employed various statistical methods to analyse household data, including frequencies, averages, and relationships. These techniques allowed for a comprehensive exploration of the data and the identification of any significant patterns or trends. To further examine the impact of the restrictions on remittance expenditure decisions, the findings from each socioeconomic category were analysed in depth. This was achieved through the use of multiple response analysis, cross-tabulation, and correlation analysis. These methods facilitated the presentation of clear and concise results on how the restrictions affect the expenditure decisions made by remittance recipients.

4. Findings and discussion

The decision to restrict the use of a remittance is influenced by several factors. The relationship between the remitter and receiver, the support the migrant had when travelling, as well as the socioeconomic status of the receiver. The paper discusses the households’ awareness of the migrant’s decision to travel, the reason for the migrants’ decision, and the support the household and respondent offered the migrant when they became aware of the intent to travel. There is also a discussion on the factors influencing the use of the restricted and unrestricted remittances.

The analysis of the data revealed in reveals that 59.36% of the respondents are male. The other 40.64% are females. Age composition is a significant factor in expenditure decisions as it is linked to the responsibilities of the individuals. Data from shows that the average age of respondents is 41 years and the median age of 38 years. The youngest respondent is 20 years while the oldest is 80 years. Inferences from the data suggest that the study respondents are middle-aged Ghanaians.

Table 2. Demography of respondents.

4.1. Income level of respondents

Due to the link between income and choice limitation in decision making, income is expected to be an important criterion in the study. The median income of the study respondents was 9,000 Ghana Cedis. The average income of the study respondents was 15,890.67 Ghana Cedis. Most of the respondents (63.13%) make between GHS 3,960 - 14,999 a year. About 29.02% of the respondents earn GHS 15,000 and above in a year ().

Table 3. Income level of respondents.

According to the Ghana Statistical Service (Citation2019), the annual average income per capital in Ghana is GH¢11,694. Urban localities recorded an annual average per capita income of GH¢16,373 while their rural counterparts have an average annual income of GH¢5,880. This indicates that the mean respondent’s average annual income is more than the national average and very close to the urban average income.

4.2. Awareness of travel

The analysis of the data from respondents reveals that majority of them (representing 78%) were aware of the migrant’s decision to travel. Only 22% of the respondents were unaware. The finding that 78% of the respondents were aware of the migrant’s decision to travel is significant as it suggests that the decision to migrate is usually a family decision, rather than an individual one. This finding is consistent with previous research conducted in Nepal by Gartaula et al. (Citation2012) and indicates that the decision to migrate is often made after consultation with close family members. The migrants-in-waiting make their intentions known to their close family members. Generally, these include the wives, parents, and children. This was true even in families where women had less autonomy (Shattuck et al., Citation2019). The finding shows that wives, parents, and children are usually included in these discussions suggests that the decision to migrate is not made by the individual alone, but rather is a collective decision-making process.

4.3. Support for migrants’ travels

Of the 530 respondents that were aware of the migrants’ decision to travel, 80% of them provided support to the migrants to aid them in their travels. About 20% of the respondents who were aware of the migrants’ travel decisions did not provide any support. However, with reference to the total population of study respondents’, 76.92% provided support to the migrants.

Literature reveals various motivations for the support for migrants (Cerdin et al., Citation2014; Hagelskamp et al., Citation2010). Previous study by Rindfuss et al. (Citation2012) revealed that family members do support the travel decisions of migrants-in-waiting, but these decisions are influenced by factors including marital status, the presence of children, and having parents in the origin household. However, in this study, respondents revealed no such motives.

4.4. Form of support to migrants

The study categorised the support for the migrants into two categories: monetary and non-monetary support. Of the 426 respondents who provided support, 90% of them provided monetary support with 10% offering non-monetary support. Compared to the larger study respondents, 61.83% of them provided monetary support to the migrants while 6.24% provided non-monetary support.

Although the evidence for monetary support for migrants is not explicit in literature, studies by Darkwah and Verter (Citation2014) in Nigeria; Adams and Cuecuecha (Citation2013) in Ghana; and Beyene (Citation2014) in Ethiopia suggest that determinants of remittance received in Sub-Saharan Africa and MENA regions are influenced by the help the migrants received when they needed it.

4.5. Reasons for supporting migrant

The decision to support someone is motivated by a myriad of reasons. The decision to support a family member’s decision to leave Ghana is also influenced by several reasons and the study sought to find those reasons. presents multiple responses of the reasons the study respondents supported the migrants. For the majority of the study respondents’ (representing 70%), the support was a duty of care to a family member. 37% of the respondents supported migrants because the regarded it as a form of investment with which they expected returns.

Table 4. Multiple responses- why did the family provide support?

The majority of the study respondents (as shown in ) described an exchange motive. According to Cox (Citation1987) and Rapoport and Docquier (Citation2005), the remittances transfers are paid to the household at home for services provided (e.g. child care). Also, the 37% of the respondents described their support for the migrants as a form of investment. For this group, the Stark (Citation1991) theory of implicit coinsurance agreement applies. Within this theory, migration of the migrants is a risk spreading strategy where household members are placed at different geographic locations as a way to hedge against risks to a sustainable livelihood. For both groups, the household members did not sit down with the migrants to draw up a contract stating their reasons and conditions. Under both reasons, if the migrant’s income increases, the remittances increase. The type of environment influences the arrangement and motivations to offer support.

A study by Loschmann and Siegel (Citation2019) in an insecure environment like Afghanistan revealed that households revealed that families establish household members at different geographic locations, usually abroad, as a way to hedge against risks to a sustainable livelihood. In Ghana, remittances are also an important coping strategy for households in dealing with economic and social risks. According to Teye et al. (Citation2016), international migration is seen as a way of coping with economic challenges in Ghana. This is because it provides households with access to additional sources of income and enhances their ability to diversify income sources, reducing their vulnerability to shocks. Additionally, as in the case of Afghanistan, households in Ghana also establish household members in different geographic locations, usually abroad, to hedge against risks to sustainable livelihoods. This is because remittances can provide a stable and reliable source of income for households, reducing their reliance on more volatile sources of income. Thus, similar to the findings in Afghanistan, the establishment of household members abroad through migration is a common coping strategy among households in Ghana to mitigate economic risks and enhance sustainable livelihoods. In an insecure environment, the risk-coping strategy may be less about having an alternative source of income and more about having an alternative location to escape to if the security situation happens to take a turn for the worse. In a relatively secure environment like Ghana, the risk-coping strategy is more about having an alternative source of income for the household as shown in this paper.

4.6. Reason for migrant travels

The decision to leave one’s home country to another is influenced by several reasons. The study respondents stated reasons the migrants left. For majority of the respondents, the migrants left for economic reasons as reflected in 76% of the respondents stating employment reasons as the main factor for the migrants’ decision. The second highest reason is the need for formal education; 13% of the respondents attributed the need for a higher education as the main reason the migrants left. This is presented in .

Table 5. Reason for migrant travels.

The employment reason being the popular reason is supported by several studies. In Nigeria, Darkwah and Verter (Citation2014), showed that lack of employment opportunities was the most significant push factor as migrants’ sough for work opportunities beyond their home country. The situation in Ghana is not much different as Adams and Cuecuecha (Citation2013) show that most of the international migrants are economic migrants. In Ghana, the talks about moving abroad as economic migrants start very early as children aged 8 years dream about transnational migration for economic reasons (Coe, Citation2012).

4.7. Decisions on remittance expenditure

Who gets to decide the use of the remittance is an essential part of the discussion on remittance expenditure. People of different ages and social status make different decisions. provides data on who makes the expenditure decision. About 47% and 46% of the decisions on remittance expenditure are made by the remitter and recipient respectively. The household head is third as they make 5% of the decisions on remittance expenditure. This finding follows the earlier evidence gathered by various researchers. The previous works have shown that the household is the first unit which takes a decision on the use of remittances (Chami et al., Citation2005; Seshan, Citation2012).

Table 6. Decision on remittance expenditure.

4.8. Implications for not following instructions

Previous studies have shown that people take advantage of information asymmetries within households to hide financial decisions they make on remittances from other members of their families (Ashraf, Citation2009; Schaner, Citation2012). This behavior may be especially prominent in migrant households that are geographically split (De Laat, Citation2008; Kagochi & Chen, Citation2013) but whose finances are linked through the sending and spending of regular remittance payments. In this study, the study respondents are given clearer restrictions. Regardless of the clearer restrictions, people do not always follow instructions and the stories about misappropriation of remittances for personal gains are abound. Receivers of remittances usually have a mental image of what is likely to happen should they fail to follow the instruction that come with the remittances. From the study analyses, 27% of the respondents believe the remitter will be angry if they fail to follow the instructions. 11% of the respondents believe the remitter will stop sending the remittances once they find out the instructions are not followed ().

Table 7. Implications for not following instructions.

4.9. An analysis of restricted and unrestricted remittances

Usually, remittances are received under imperfect information, uncertainty and with different regularity (Randazzo & Piracha, Citation2014). With these variables in place, researchers argue that households perceive the international remittances as not straightforward. The uncertainty can be partly explained by researchers ignoring the concept of free balance in the expenditure of remittances. However, within the context of the study, attention has been given to the instructions based on two categories- (1) the ones the recipients make the decision on (2) the ones where expenditure decisions come from the remitter.

As presented in , most remittances received by the remittances in the last 365 days came with no instructions. This represents 58.02% of the total remittances received in the time frame. The other 41.97% of the remittances came with instructions. The average amount of restricted remittances was GHS 1,707.22. The average amount of unrestricted remittance is GHS 2,360.50.

Table 8. Restricted and unrestricted remittance.

4.10. Use of restricted remittance

The restricted remittances come with specific instructions on how to spend it. The study analysed what these instructions are as presented in . Of all the remittances received, 17% came with specific instructions to support the family. This is followed by education, where 10% of the remittances were meant to fund. As pointed out earlier, the risk-coping strategy is more about having an alternative source of income for the household. This is buttressed by the particular instructions that come with the international remittances. They are geared towards aiding the family in carrying out its essential responsibilities and duties.

Table 9. Use of restricted remittance.

4.11. Relationship between restricted remittance and socioeconomic status

The study employed a bivariate correlation to find a relationship between restricted remittance and socioeconomic status. From there is a statistically significant association between level of formal education and restricted remittances received as the study found a negative correlation (0.-495) at a significant level of 0.05. The longer the years of formal education, the less they receive restricted remittances.

Table 10. Relationship between restricted remittance and socioeconomic status.

The study also found a positive correlation between the age of the receiver and the receipt of restricted remittance [correlation 0.454; 0.05 level (2-tailed)]. The highest correlation was between the amount of remittance sent and restricted remittance [correlation 0.693; 0.05 level (2-tailed)]. This could be that large amount of remittances are usually for more specific projects which the remitter wants to carry out. There is also a positive correlation between the age of respondent and the restricted amount of remittance received [correlation 0.521; 0.05 level (2-tailed)].

4.12. Use of unrestricted remittance

The expenditure of unrestricted remittance in shows that most of the remittances received that came with no instructions were invested by the recipients of the remittances. Also, 8% of the remittances were spent on non-durable goods. Same percentage was spent on semi-durable goods.

Table 11. Use of unrestricted remittance.

The findings of the study support the treatment of remittances as a transitory type of income. This can be explained by the income level of the study respondents. 92.15% of the study respondents are in the rich and upper middle-class category (). This finding supports earlier works by researchers such as Edwards and Ureta (Citation2003) who found out that households tend to spend them more at the margin on capital goods, human and physical capital investments, than consumer goods. Also, Adams (Citation2010) using nationally representative household data set from Gautemala found that households receiving international remittances spend marginally less on consumer goods like food and spend marginally more on capital goods such as education and housing compared to what they would have spent on these goods without the remittances (Adams & Cuecuecha, Citation2010, Citation2013).

4.13. Relationship between unrestricted remittance and socioeconomic status

The formal educational level, income level, health of respondent, and period of stay correlates with the unrestricted remittance received. Formal educational level [correlation 0.371; 0.05 level (2-tailed)], income level [correlation 0.471; 0.05 level (2-tailed)], and health of respondent [correlation 0.365; 0.05 level (2-tailed)]. However, the period of stay (after a year) has a negative correlation with the unrestricted remittance received [correlation -0.503; 0.05 level (2-tailed)]. While there was no relationship between the length of stay and the amount of restricted remittances received, as the length of the stay increased, the unrestricted remittances received decreased ().

Table 12. Relationship between restricted remittance and socioeconomic status.

5. Discussion

International remittances have the potential to change the expenditure pattern of recipients. In a world where decisions made by people are influenced by several factors, the question of what influences expenditure decisions on remittances continues to be a topic of debate. In the discussion, the issue of restricted and unrestricted remittances has received limited attention. Not all remittances come without instructions and when they do come with instructions, what do these instructions entail? For the ones without instructions, how do the recipients expend them? The paper contributes to the discussion on remittance expenditure with a focus on the restricted and unrestricted remittances received. The data allowed the researchers to discuss the types of recipients of remittances, recipients of restricted remittances, and unrestricted remittances.

The analyses of the data revealed that the instructions on restricted remittances were mostly for family support. This is consistent with the exchange motive theory of support for migrants (see Lucas & Stark, Citation1985). The majority of the recipients of the remittances supported the migrant’s travels. This was done as a form of support to the migrants. In exchange, the migrants send remittances for family support. This finding supports earlier works by Baldassar and Wilding (Citation2013) and Coe (Citation2016). The other significant restrictions on restricted remittances are for the purposes of education and building.

Remittances are classified as transitory income for the second type of remittance recipients—recipients of unrestricted remittances. Although there was support for the migrants, there was the understanding that the remittances will not keep coming forever and that they need to invest the ones they receive at the moment. The treatment of remittance as transitory income is supported by previous works by Adams and Cuecuecha (Citation2010), Bouoiyour et al. (Citation2016), and Cattaneo (Citation2012). The treatment of unrestricted remittance as transitory income can also be explained by the income level of the recipients. Many recipients are within the rich and middle-class income category and are already in the position to purchase basic necessities. Thus, the study supports the idea that when households are not guaranteed to receive the remittance tomorrow, they tend to spend the remittances mostly on capital goods.

Who chooses remittance expenditure has an impact on how the funds are spent. Pickbourn (Citation2016) found that women migrants in Ghana are more likely to transfer remittances to other women in the family. According to other research, women prefer to spend their transfers on food, clothes, schooling, and healthcare, whereas males prefer to spend their transfers on housing and consumer items (IOM, Citation2005). The bulk of the expenditure decisions in this study was made by the household head, who may be seen as the leader needed to make such decisions.

Previous research has revealed that people employ information asymmetries within households to conceal the financial decisions they make on international remittances from other members of their families (Schaner, Citation2012). In this survey, the respondents were given clearer restrictions. Regardless of the explicit limits, people do not always follow instructions, and examples of remittance misappropriation for self-gain exist. Remittance receivers commonly imagine what will happen if they do not follow the instructions that come with the remittances. According to the results, the majority of respondents believe that if the criteria are not followed, the remitter would be upset.

Seror (Citation2012) believes that demonstrating the prevalence of information asymmetries in the remittance setting has at least two effects. Firstly, it demonstrates the empirical insignificance of the unitary and communal family models. Because migrants and their relatives in their home country are considered members of the same (transnational) family, their actions should benefit the entire group. Now, because families of origins can collect monies from transfer senders using private knowledge, the presumption or forecast (based on altruism) that migrants and non-migrant relatives would always arrive at optimal intra-household allocations is inappropriate.

The majority of the restricted remittances received came with specific instructions to help the family. This might indicate that restricted remittances are mostly received when a family experiences an economic or social shock. To recover from such shocks, migrants send restricted remittances.

While the recipient’s and remitter’s ages correlate with remittance restrictions, the highest correlation was found between the volume of remittance sent and restricted remittance. This might be because significant amounts of remittances are often for more specified initiatives that the remitter wants to complete. The expenditure of unrestricted remittances shows that most of the remittances received that came with no instructions were invested by the recipients of the remittances. It may be that the households treat the private international remittance as a transitory income that they are not guaranteed to receive tomorrow, and as such spend the remittances mostly on investments.

There are social and economic implications of the study findings. For the economic implications, remittances, particularly unrestricted ones, assist in supporting initiatives in education, healthcare, and housing. This can lead to enhanced human capital in recipient households, which can assist long-term economic growth. Individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to secure higher-paying jobs, and better health can lead to increased output. Unrestricted remittances are generally treated as transitory income, which encourages recipients to invest in capital goods. This can stimulate economic growth by promoting capital accumulation, especially in areas where credit or capital is limited. Increased investment can lead to the foundation of new businesses and the creation of new job opportunities.

Concerning social implications, the predominance of restricted remittances for family assistance emphasises the value of family networks and mutual support systems. Migrants pitch in to help their families back home when they are in financial need. This helps to enhance family bonds and societal cohesiveness. the study results show that remittance recipients may not always follow the precise instructions that come with remittances. This demonstrates that information asymmetry exists within families. It implies that the assumption of optimum intra-household allocations based on benevolence may not always hold true, potentially leading to family disputes and misunderstandings.

6. Conclusion

The capacity to send money to one area and receive it in another can help recipients better their living conditions. With private international remittances demonstrated to influence spending patterns, external migration can assist recipients’ economic growth and development. Increased spending on schooling, shelter, healthcare and basic essentials all contribute to increased human capital. To maximize the impact of remittances, it is critical that policies encouraging remittances be put in place. The findings from this paper have obvious implications for Ghana with a youthful population eager to go seek greener pastures. The authors recommend a more liberal immigration policy. In an era of high mobility, labour policies should not be constrained; lowering barriers to migration may result in large gains in household welfare in receiving areas. Recognizing the critical role that external migration and overseas remittances may play in alleviating poverty in recipient families is critical for the establishment of a pro-migration policy. Furthermore, the finding that limited remittances are usually received when a family undergoes an economic or social shock may reflect the state’s poor social protection measures. Since there is no significant social insurance plan, low-income households are left on their own during economic downturns. The authors argue for the implementation of the state’s social welfare programme to aid such households.

Future studies should consider the long-term influence of remittances on economic growth, specifically job creation, and income generation at the local and regional levels. Future studies may probe deeper into the dynamics of remittance allocation and decision-making within families and how it affects family relationships and well-being.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eugene Danquah Ofori-Appiah

Eugene Danquah Ofori-Appiah holds a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Development Studies from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana. Eugene Danquah Ofori-Appiah is a part time lecturer at the University of Cape Coast College of Distance Education (CODE). His key areas of interest are Development Economics, Labor, law and Migration, finance, and Urban Development.

Kwaku Dwumor Kessey

Professor Kwaku Dwumor Kessey is a person of diverse expertise. He is a University professor, researcher, and consultant in Development Planning, and Economics with special expertise in Economic Policy and Development Finance. He has experience in Organizational leadership and Human Development as Head of Department and member of several boards and committees at KNUST and outside. His areas of interest include Economic Planning: Finance and Banking, Public Financial Management, Poverty in Developing countries, Small Scale Mining and Environmental Degradation, Credit Risk Management in banking industry, Financial inclusion and mobile Money services, Micro Credit and growth in Small, Medium Enterprise, Decentralization and local governance just to mention a few.

Eric Oduro-Ofori

Dr. Eric Oduro-Ofori obtained his PhD in Local Governance and Local Economic Development from the Faculty of Spatial Planning, University of Dortmund, Germany in 2011. He is currently a lecturer at the Department of Planning. His special interest is in local governance, local economic development and urban spatial development management.

References

- Ackaah, W., & Aidoo, E. N. (2020). Modelling risk factors for red light violation in the Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 27(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300.2020.1792936

- Adams, R. H., Jr. (2010). Evaluating the economic impact of international remittances on developing countries using household surveys: A literature review. Journal of Development Studies, 47(6), 809–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2011.563299

- Adams, R. H., Jr. & Cuecuecha, A. (2010). The economic impact of international remittances on poverty and household consumption and investment in Indonesia. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (5433). https://ssrn.com/abstract=1683904

- Adams, R. H., Jr., & Cuecuecha, A. (2013). The impact of remittances on investment and poverty in Ghana. World Development, 50, 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.04.009

- Ahinful, G., Boateng, F., & Oppong-Boakye, P. (2013). Remittances from abroad: The Ghanaian household perspective. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(1), 64–170. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334459489_Remittances_from_Abroad_The_Ghanaian_Household_Perspective

- Alcaraz, C., Chiquiar, D., & Salcedo, A. (2012). Remittances, schooling, and child labor in Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 97(1), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.11.004

- Ashraf, N. (2009). Spousal control and intra-household decision making: An experimental study in the Philippines. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1245–1277. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.4.1245

- Baldassar, L., & Wilding, R. (2013). Middle-class transnational caregiving: the circulation of care between family and extended kin networks in the global north. In L. Baldassar & R. Wilding (Eds.), Transnational families, migration and the circulation of care (pp. 251–268). Routledge.

- Baruch, Y. (1999). Response rate in academic studies-A comparative analysis. Human Relations, 52(4), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679905200401

- Beyene, B. M. (2014). The effects of international remittances on poverty and inequality in Ethiopia. The Journal of Development Studies, 50(10), 1380–1396. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.940913

- Bouoiyour, J., Miftah, A., & Mouhoud, E. M. (2016). Education, male gender preference and migrants’ remittances: Interactions in rural Morocco. Economic Modelling, 57, 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2015.10.026

- Castles, S., de Haas, H., & Miller, M. J. (2013). The age of migration-international movements in the modern world (S. Castles ed.). Guilford Pubn. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803920500434037

- Cattaneo, C. (2012). Migrants’ international transfers and educational expenditure: Empirical evidence from Albania. Economics of Transition, 20(1), 163–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0351.2011.00414.x

- Cerdin, J. L., Diné, M. A., & Brewster, C. (2014). Qualified immigrants’ success: Exploring the motivation to migrate and to integrate. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.45

- Chami, R., Fullenkamp, C., & Jahjah, S. (2005). Are immigrant remittance flows a source of capital for development? IMF Staff Papers, 52(1), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/30035948

- Clemens, M. A., & McKenzie, D. (2014). Why don’t remittances appear to affect growth? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6856, The World Bank. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2433809

- Coe, C. (2012). Growing up and going abroad: How Ghanaian children imagine transnational migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(6), 913–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.677173

- Coe, C. (2016). Orchestrating care in time: Ghanaian migrant women, family, and reciprocity. American Anthropologist, 118(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.12446

- Cox, D. (1987). Motives for private income transfer. Journal of Political Economy, 95(3), 508–546. 508547. https://doi.org/10.1086/261470

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Mapping the field of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 3(2), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689808330883

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Controversies in mixed methods research. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4(1), 269–284.

- Darkwah, S. A., & Verter, N. (2014). Determinants of international migration: The Nigerian experience. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 62(2), 321–327. https://doi.org/10.11118/actaun201462020321

- De Laat, J. (2008). Household allocations and endogenous information. CIRPEE Working Paper No. 08-27. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1268976 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1268976

- Edwards, A. C., & Ureta, M. (2003). International migration, remittances, and schooling: Evidence from El Salvador. Journal of Development Economics, 72(2), 429–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00115-9

- Erdman, C., Adams, T., & O’Hare, B. C. (2016). Development of interviewer response rate standards for national surveys. Field Methods, 28(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X15574253

- Gartaula, H. N., Visser, L., & Niehof, A. (2012). Socio-cultural dispositions and wellbeing of the women left behind: A case of migrant households in Nepal. Social Indicators Research, 108(3), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9883-9

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2019). Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS) 7, main report. Accra GSS. https://www2.statsghana.gov.gh/nada/index.php/catalog/97/study-description

- Hagelskamp, C., Suárez‐Orozco, C., & Hughes, D. (2010). Migrating to opportunities: How family migration motivations shape academic trajectories among newcomer immigrant youth. Journal of Social Issues, 66(4), 717–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01672.x

- IFAD. (2021). 12 reasons why remittances are important. Retrieved April 14, 2023, from https://www.ifad.org/en/web/latest/-/12-reasons-why-remittances-are-important#:∼:text=According%20to%20the%20latest%20World,every%20one%20to%20two%20months

- International Organization for Migration. (2005). World migration. Costs and benefits of international migration. IOM World Migration Report Series.

- Jena, F. (2015). The empirical analysis of the determinants of migration and remittances in Kenya and the impact on household expenditure patterns [Doctoral dissertation, University of Sussex]. https://sussex.figshare.com/articles/thesis/The_empirical_analysis_of_the_determinants_of_migration_and_remittances_in_Kenya_and_the_impact_on_household_expenditure_patterns/23416484

- Kagochi, J., & Chen, C. P. (2013). Are remittances to Sub-Saharan Africa altruistic or for self-interest? Evidence from Kenya. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 5(12), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v5n12p70

- Kakhkharov, J., Ahunov, M., Parpiev, Z., & Wolfson, I. (2020). South‐south migration: remittances of labour migrants and household expenditures in Uzbekistan. International Migration, 59(5), 38–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12792

- Kemper, D., Faust, H., & Kreisel, W. (2003). «Knowledge» as cultural impact factor for land use change. Findings from Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. In D. Stietenroth, W. Lorenz, S. Tarigan, & A. Malik (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Symposium «The stability of tropical rainforest margins. Linking ecological, economic and social constraints of land use and conservation», Göttingen, 19-23September 2005.-Göttingen: UniversitätsverlagGöttingen: 5859.

- Kim, M. (2013). Citizenship projects for marriage migrants in South Korea: Intersecting motherhood with ethnicity and class. Social Politics, 20(4), 455–481. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxt015

- Kroes, G. (2005). Central grants for local development in decentralized planning system, Ghana. SPRING Research Series No. 23, SPRING Center Dortmund.

- Kunwar, L. S. (2021). Impacts of migration on poverty reduction: A critical analysis. Journal of Population and Development, 2(1), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.3126/jpd.v2i1.43479

- Le, Q. H., & Nguyen, T. H. T. (2019). Impacts of migration on poverty reduction in Vietnam: a household level study. Business and Economic Horizons, 15(2), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.15208/beh.2019.16

- Levando, D. (2020). The two demands: Why a demand for non-consumable money is different from a demand for consumable goods. University Ca’Foscari of Venice, Department of Economics Research. Paper Series No. 5. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3601683

- Loschmann, C., Bilgili, Ö., & Siegel, M. (2019). Considering the benefits of hosting refugees: Evidence of refugee camps influencing local labour market activity and economic welfare in Rwanda. IZA Journal of Development and Migration, 9(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40176-018-0138-2

- Lucas, R. E., & Stark, O. (1985). Motivations to remit: Evidence from Botswana. Journal of Political Economy, 93(5), 901–918. https://doi.org/10.1086/261341

- Mahapatro, S., Bailey, A., James, K. S., & Hutter, I. (2017). Remittances and household expenditure patterns in India and selected states. Migration and Development, 6(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2015.1044316

- Nahar, F. H., & Arshad, M. N. M. (2017). Effects of remittances on poverty reduction: The case of Indonesia. Journal of Indonesian Economy & Business, 32(3), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.22146/jieb.28678

- Petreski, M., Mojsoska-Blazevski, N., Ristovska, M., & Smokvarski, E. (2014). Youth self-employment in households receiving remittances in Macedonia. Partnership for Economic Policy Working Paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2526737

- Pickbourn, L. (2016). Remittances and household expenditures on education in Ghana’s northern region: why gender matters. Feminist Economics, 22(3), 74–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2015.1107681

- Prabal, K. D., & Dilip, R. (2012). Impact of remittances on household income, asset and human capital: Evidence from Sri Lanka. Migration and Development, 1(1), 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2012.719348

- Quartey, P., & Adamba, C. (2015). Inter-linkages between international and internal remittances and financial sector development in Ghana. International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 10(3), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEBR.2015.071841

- Rahman, M. M., & Fee, L. K. (2012). Towards a sociology of migrant remittances in Asia: Conceptual and methodological challenges. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(4), 689–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.659129

- Randazzo, T., & Piracha, M. (2014). Remittances and household expenditure behaviour in Senegal. IZA Discussion Paper No. 8106. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2426860 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2426860

- Rapoport, H., & Docquier, F. (2005). The economics of migrants’ remittances. Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity, 2, 1135–1198. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0714(06)02017-3

- Ratha, D. (2014). The impact of remittances on economic growth and poverty reduction. Policy Brief, 8(1), 1–13.

- Ratha, D., & Mohapatra, S. (2007). Increasing the macroeconomic impact of remittances on development. World Bank, 3(1), 178–192.

- Ratha, D., Kim, E. J., Plaza, S., Seshan, G., Riordan, E. J., & Chandra, V. (2021). Migration and development brief 35: Recovery: COVID-19 crisis through a migration lens. KNOMAD-World Bank. CID: 20.500.12592/g204bw.

- Rindfuss, R. R., Piotrowski, M., Entwisle, B., Edmeades, J., & Faust, K. (2012). Migrant remittances and the web of family obligations: Ongoing support among spatially extended kin in North-east Thailand, 1984–94. Population Studies, 66(1), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2011.644429

- Schaner, S. (2012). Gender, poverty, and well-being in Indonesia: MAMPU background assessment. Dartmouth College Department of Economics. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/mampu-gender-poverty-wellbeing-background-assessment.pdf

- Seror, M. (2012). Measuring information asymmetries and modeling their impact on Senegalese migrants’ remittances. Mémoire de Master, Paris School of Economics.

- Seshan, G. (2012). Does asymmetric information in transnational households affect remittance flows? https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2266851

- Shattuck, D., Wasti, S. P., Limbu, N., Chipanta, N. S., & Riley, C. (2019). Men on the move and the wives left behind: the impact of migration on family planning in Nepal. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(1), 1647398–1647261. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2019.1647398

- Stark, O., & Stark, O. (1991). The migration of labour. http://class.povertylectures.com/Stark1991MigrationofLaborChapts1-3.pdf

- Sunny, J., Parida, J. K., & Azurudeen, M. (2020). Remittances, investment and new emigration trends in kerala. Review of Development and Change, 25(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972266120932484

- Szabo, S., Ahmed, S., Wiśniowski, A., Pramanik, M., Islam, R., Zaman, F., & Kuwornu, J. K. (2022). Remittances and food security in Bangladesh: An empirical country-level analysis. Public Health Nutrition, 25(10), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980022001252

- Teye, J. K., Badasu, D., & Yeboah, C. (2016). Assessment of remittances-related services and practices of financial institutions in Ghana. https://www.iom.int/ sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/country/docs/ghana/IOM-Ghana-Assessment-of-Remittance-Related-Services-and-Practices-of-Financial-Institutions-in-Ghana.pdf

- United Nations. (2017). World population prospects: the 2017 revision, key findings and advance tables.

- Uprasen, U. (2018). The impacts of international remittances on economic growth and human development of Haiti. Journal of Global and Area Studies(JGA), 2(2), 77–104. https://doi.org/10.31720/JGA.2.2.5

- Vogel, A., & Korinek, K. (2012). Passing by the girls? Remittance allocation for educational expenditures and social inequality in Nepal’s households 2003–2004. The International Migration Review, 46(1), 61–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2012.00881.x

- Wang, D., Hagedorn, A., & Chi, G. (2021). Remittances and household spending strategies: evidence from the Life in Kyrgyzstan Study, 2011–2013. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(13), 3015–3036. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2019.1683442

- Wasti, K. (2017). Remittances and long-term livelihood security in the Mountains of Nepa l55. In B. Knerr (Ed.), International labor migration and livelihood security in Nepal: Considering the household level (Vol. 22, p. 113). Kassel University Press GmbH. http://dx.medra.org/10.19211/KUP9783862199457

- World Bank. (2017). The Global Findex database 2017. World Bank.

- World Bank. (2020). Phase II: COVID19 crisis through a migration lens. Migration and development brief 33. https://www.knomad.org/publication/migration‐and‐development‐brief‐33

- World Bank. (2021). World development report 2021: Data for better lives.

- Yang, D. (2011). Migrant remittances. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(3), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.25.3.129