?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Entrepreneurship is frequently seen as a motivation to raise people’s standards of living, maintain a healthy economy, and preserve the environment. This paper empirically investigated factors influencing farm entrepreneurship among emerging farmers under the land restitution program in Limpopo Province, South Africa, a topic that has not yet been sufficiently explored. Using a stratified sampling procedure, data was collected using a structured questionnaire from a sample of 200 emerging farmers. The farm entrepreneurship index was created using principal component analysis and used as a dependent variable to determine factors influencing farm entrepreneurship in an OLS model. The results showed that there is low farm entrepreneurship among emerging farmers in Limpopo Province. In addition, farm entrepreneurship is negatively influenced by the age of the farmer, while location, enterprise farming, innovation technology, extension services, market information and farmer association positively influence farm entrepreneurship. The study recommends that government develop policies that focus more on the provision of extension services, the support of farmer associations, skill trainings, market connections and supportive policy environments for the growth of business mindset among the emerging farmers.

1. Introduction

The land restitution program deals with the Restitution of Land Rights Act 22 of 1994. In order to restore land rights to people or communities who had lost them after June 19, 1913, as a result of historically racist laws or practices, the Restitution of Land Rights Act of 1994 was established (Restitution of Land Rights Act 22, Citation1994). The main objective of this program is to support the processes of development and reconciliation by providing people who have been evicted due to racially discriminatory laws and practices with land back and other remedies (Department of Land Affairs (DLA), Citation1997). The people eligible to claim, according to the Restitution of Land Rights Act 22, Citation1994, are those whose descendants were forcibly evicted from their land following the legislation of the Native Land Act of 1913. The program excludes the people whose land was taken before 1913. Possible explanation for exclusion is that those who have been evicted before 1913 wouldn’t be able to prove in court that the land belonged to their forefathers (Chitonge, Citation2022).

Land restitution in South Africa advanced in numerous ways such as settlement through cash compensation, restoration of previous land, provision of substitute land, provision of other development opportunity or a grouping of the above. The first phase of land restitution program began in 1994, with the passage of the Land Restitution Act, and beneficiaries were permitted to file claims until the end of 1998. During this phase, only 80 000 claims were lodged, by the end of 2000, the program had resolved approximately 3 916 claims (Commission on the Restitution of Land Rights (CRLR), Citation2000). The second phase started in July 2014, after the signing of the Restitution of Land Rights Amendment (RLRA) Act No. 15 of 2014. The Restitution Act was amended to speed up the process because the land restitution program has historically been cumbersome. During this phase, 71 000 claims had been settled by December 2015, and 5 084 claims remained unresolved (CRLR, Citation2016). According to the President of South Africa (2019), the country’s land restitution program transferred 3.5 million hectares of land to people with limited access in 2018. South African government provided post settlement support to the most complying land restitution beneficiaries to enhance the better usage of the land. In line with National Development Plan 2030, one of the objectives was to intensify, transform and commercialise emerging agriculture while advancing farmer’s entrepreneurial competencies (Department of Agriculture and Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF), Citation2011).

The goal of entrepreneurship is frequently viewed as being to raise people’s standards of living, maintain a healthy economy, and protect the environment. In developing areas, the perception of entrepreneurship is as a strategic development intervention that could speed up the rural development process. Moreover, government, private institutions and individuals agree on the urge to promote rural businesses. Various institutions view entrepreneurship differently; farmers perceive it as an instrument to improve their farming income, development agencies view entrepreneurship as a key strategy to create jobs, while politicians see it as key to prevent rural unrest and crime (Chandramouli et al., Citation2007). Entrepreneurship can be defined as an ability of an entrepreneur to become market oriented and profitable (de Wolf & Schoorlemmer, Citation2007). According to Filion (Citation2011), an entrepreneur is someone who seizes opportunities, takes calculated risks that may result in the efficient use of resources, and consistently engages in value-adding activities. The current study defines an entrepreneur as someone who manages a business or farm with the intention of growing it and who possesses the managerial and leadership skills necessary to achieve business goals (Gray, Citation2002). The definition, according to Sinyolo et al. (Citation2017), is relevant for the smallholder farmers in South Africa’s rural areas because it includes businesses that are still in the early stages of development or are currently not profitable. Entrepreneurships are made up of two distinct components, such as the abilities needed to launch and operate a successful business and the entrepreneurial spirit needed to do so. Many emerging farmers in South Africa still do not view farming as a business. According to Kahan (Citation2013), this is due to their conventional production method, which is based on their abilities or knowledge. According to Kahan (Citation2013) and Sinyolo et al. (Citation2017), young farmers have little chance of succeeding unless they adopt an entrepreneurial mindset and run their farms like businesses.

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor South Africa (GEM SA) 2019/2020 report states that South Africa’s Total Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) rate decreased in 2019 and was less than the global average of 12.1%. In 2019, there were 4.9% more business closures than the establishment of business ownership (3.5%). These results showed that more businesses are being sold or closed. The results showed that entrepreneurs only made a small contribution to GDP growth. Despite rising from 2.2% in 2017 to 3.5% in 2019, the rate of founded business ownership is still subpar when compared to other developing nations (Bowmaker-Falconer & Herrington, Citation2020). This low performance in entrepreneurship and the nation’s rising unemployment rate demonstrate that few people attempt to launch their own businesses, which may be due to a lack of funding, lack of profit from the business, inadequate skills, lackluster entrepreneurial attitudes or lack of new opportunities. Moreover, South Africa generally lacks an entrepreneurial spirit (Herrington et al., Citation2015). The business discontinuance rate has increased from 4.5% in 2016 to 6.0% in 2017 in South Africa, with Limpopo, Gauteng, and Western Cape being the lead provinces. The latter highlights that the country is essentially progressing backwards regarding the entrepreneurial activity (Bowmaker-Falconer & Herrington, Citation2020).

Several studies, including McElwee (Citation2006), Chandramouli et al. (Citation2007), Vesala and Pyysiäinen (Citation2008) concurred that if farmers in rural areas adopted more entrepreneurial farming practices, it will lead to the eradication of poverty, increased food security, and jobs in their specific areas. Farmers in rural areas should develop an entrepreneurial mindset and skills because doing so will enable them to endorse industrialisation in their communities using forward and backward integration as well as to become more alluring and successful business owners and attract potential investors (Khayri et al., Citation2011). Rural farmers have a significant impact on lowering rural unemployment and halting migration from the countryside to the city (Chandramouli et al., Citation2007).

Although the different studies have indicated the benefits of developing a business mindset and skills, others contend that numerous entrepreneurs are resulting in low productivity. The context of entrepreneurship has not been fully investigated from the viewpoint of rural farming in South Africa, including Limpopo Province. Most of the studies conducted focused on non-agricultural entrepreneurship, omitting farm businesses. Therefore, the study on the factors influencing farm entrepreneurship in South Africa still needs to be addressed. Furthermore, the empirical and conceptual relations among farm entrepreneurship and the land restitution programs among rural emerging farmers have not been absolutely assessed in the literature. Although some existing literature addresses factors influencing entrepreneurship, the majority are international (e.g. Chandramouli et al., Citation2007; Darmadji, Citation2016; Alvarez-Risco et al., Citation2021; Schröder et al., Citation2021; Saghaian et al., Citation2022), and very few are from South Africa (e.g. Sinyolo et al., Citation2017). Moreover, none of these studies has directly investigated the possible contribution of the land restitution program to the farm entrepreneurship development of rural emerging farmers. The null hypothesis of the study states that land restitution programs measured by land size do not influence farm entrepreneurship among emerging farmers under the land restitution program in Limpopo Province. The objective of the study was to identify factors influencing farm entrepreneurship among emerging farmers under the land restitution program. This study intends to contribute to the policy development and improvement to enhance sustainable, profitable, and market-oriented farm businesses in South Africa.

2. Factors influencing entrepreneurship

Successful entrepreneurship refers to the attainment of two major goals, namely financial and non-financial (Orser et al., Citation2000). Financial goals are based on the ability to maximize profits, settle business loans, reinvest in the business, and remunerate business employees, whereas non-financial goals refer to customer satisfaction, personal growth, entrepreneurs’ awareness and many more. These goals are judged to be effective and productive (Masuo et al., Citation2001).

The level of entrepreneurial activity differs by demographic factors, such as age, experiences, education, and gender. Age negatively influences entrepreneurship. Old people are less likely to start a new business compared to young people. Females are more entrepreneurial in farming sectors than male farmers because of the lack of options or alternatives from outside farming (Saghaian et al., Citation2022). Conversely, conventional theory indicates that men have the capital to enhance business development (Rijkers & Costa, Citation2012). Education positively affects entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Alvarez-Risco et al., Citation2021). It is essential for the success of entrepreneurship because it has a significant effect on the growth of entrepreneurship, innovation and self-employment capabilities. Additionally, it takes the lead in the attainment of certain qualifications, and it stimulates characteristics regarding individual initiative and self-control to get motivated and courageous to implement new ideas. The transfer of skills, knowledge, and attitude about entrepreneurship is through education. Furthermore, through education, entrepreneurial mindsets and talents are nurtured and is prominent to a lessening of entrepreneurial barriers and failure (Schröder et al., Citation2021).

Socio-economic variables, such as farming experiences, interest rates, land holdings, the total amount of investment, and many more, have an impact on entrepreneurship success. Farming experience is positively associated with farm entrepreneurship. Farmers become more entrepreneurial and competent with increased farming experience (Man et al., Citation2008). An increase in an entrepreneur’s farm experience results in an increase in entrepreneurial success. Additionally, according to the general index of entrepreneurial success, business owners who have managerial experience, practical knowledge, and employees with specialized skills perform better than those without (Staniewski, Citation2016). Entrepreneurial success is inversely correlated with interest rates. Entrepreneurs believe that the interest rate significantly affects the likelihood of entrepreneurial success. They contend that as interest rates rise, the likelihood of successful entrepreneurship declines because rising interest rates may reduce business profits and incentives. Given that government policy determines interest rates, the government should create policies with appropriate rules and regulations that encourage new producers and entrepreneurs by reducing the risks associated with their initial investment returns (Alvarez-Risco et al., Citation2021). Land size stimulates farm entrepreneurship. The view is that farmers with adequate land are risk-takers compared to those who occupy small pieces of land. Greater land size enables households to produce more for consumption and for sale (Chandramouli et al., Citation2007).

Institutional factors, such as market access, credit financing, extension services, other government incentives and support, and infrastructure, have significant effect on the success of entrepreneurship. Market access positively influences farm entrepreneurship. Market access refers to minimal transaction costs and opportunity for the farmers to experience satisfactory returns from their produce. Therefore, the most immediate need that must be met to encourage entrepreneurship in rural areas is a guaranteed market. Secondly, access to credit is a requirement for farm entrepreneurship because it structures rural farmers’ capacity to become self-sufficient, invest in long-term projects, and take calculated risks for their businesses, ultimately fostering the growth of entrepreneurship. Furthermore, access to extension services, such as training, market information about modern technologies and markets, positively influences farm entrepreneurship (Sinyolo et al., Citation2017). Government incentives and programs include financial and technical support, workshops and training sessions, as well as resources for advice and information (Jill et al., Citation2007). These favourable incentives should inspire entrepreneurship through programs that offer financial access for new and young entrepreneurs, because entrepreneurship is an essential factor in economic development and growth. Programs should lower entry barriers, endorse development and growth and offer an improved entrance to credit facilities to promote entrepreneurial opportunities in rural areas (Alvarez-Risco et al., Citation2021). Enterprise development and sustainability are hampered by a lack of infrastructure. This unfavourable correlation between infrastructure and farm entrepreneurship was reported by Sinyolo et al. (Citation2017). Elements such as poor roads and storage inaccessibility act as barriers to market participation, hence low level of entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurs are driven to start innovative businesses for a variety of reasons, including motivational factors like achieving a healthier business environment and having competitive goods or services (Robichaud et al., Citation2001; Stefanovic et al., Citation2010). Entrepreneur performance is influenced by things like business type, risk-taking, customer focus, human capital, and the calibre of the goods produced and sold.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study design

To evaluate the effects of the land restitution program on farm entrepreneurship among emerging farmers in Limpopo Province, a cross-sectional design was used. In a cross-sectional study, participants are chosen based on inclusion and exclusion criteria (Setia, Citation2016). From three components of land reform, such as restitution, redistribution, and land tenure, the study focused on land restitution beneficiaries because the permission to conduct the study was granted by the Limpopo Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development (DALRRD). According to Setia (Citation2016), cross sectional study measures the outcomes and exposures of the selected population at the same time. Cross-sectional studies aim to attain trustworthy data that can be utilized to create robust conclusions from the research findings and generate research questions that can be addressed by future research (Zangirolami-Raimundo et al., Citation2018). It allows the researcher to recruit the desired respondents of the study and from these respondents, the primary data can be collected to answer the research objectives (Tourangeau et al., Citation2000).

3.2. Study area, sampling procedure and data collection

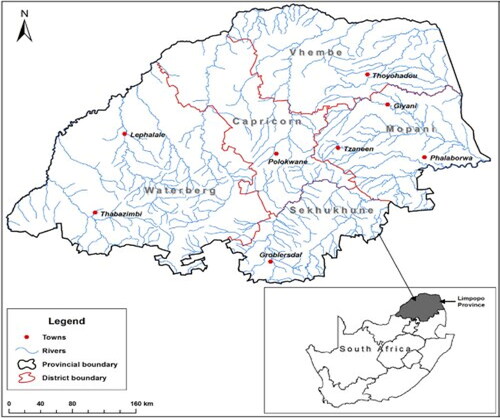

Limpopo Province is distinguished by its large number of farming-related rural households. According to the Limpopo Provincial Government (Citation2022), the province produces 75% of mangoes, 65% of papaya, 60% of avocados, 36% of tea, 25% of citrus, and many of the rural areas are devoted to cattle and game ranching. The study was conducted in the three districts of the province (see ) namely, Sekhukhune, Capricorn, and Waterberg because of the larger number of emerging farmers who are still following traditional ways of participating in agricultural activities. Most farmers in this district perceive farming as a cultural norm and not as a business. The list of emerging farmers was provided by the DALRRD. A sample of 200 emerging farmers using a stratified sampling procedure was used. The two groups of emerging farmers in the Capricorn district and one group of emerging farmers in the Waterberg and Sekhukhune districts were sampled; each stratum was made up of 50 emerging farmers, making a total of 200 respondents. The targeted participants were categorized based on their characteristics as beneficiaries of the land restitution program. Data was collected from January 2021 and January 2022 due to COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdowns, using a pre-tested structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was managed by skilled enumerators who could communicate in the local language known as Sepedi. The questionnaire’s first section asked about the farmers’ demographics, production and marketing practices for crops, vegetables, and livestock, including their institution and infrastructure preferences. Part two of the questionnaire captured information about farmer’s competencies and skills. Farmers were asked to rate the extent to which they have a variety of skills and competencies in relation to operating and managing their farming business using a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) for competencies and 1 (very low) to 5 (very high) for skills.

Figure 1. Map of Limpopo Province.

Source: Cai et al. (Citation2017).

3.3. Conceptual approach

The competency approach was used in this study to comprehend the entrepreneurial traits of rural farmers. Several literatures have adopted the competency approach to investigate entrepreneurship levels (Bergevoet et al., Citation2005; Man et al., Citation2002, Citation2008; Phelan & Sharpley, Citation2012; Sánchez, Citation2012; Vesala & Pyysiäinen, Citation2008). This approach is appropriate to small-scale producers dominated by the entrepreneur (Phelan & Sharpley, Citation2012). The competency approach places a lot of emphasis on the higher-level abilities or competencies needed by entrepreneurs to operate successfully and effectively. It calls for the capacity to carry out specialized tasks, including the fundamental comprehension, abilities, experiences, individual characteristics, and understanding of how these contribute to efficient task completion (Bergevoet et al., Citation2005). Additionally, competencies cover a wide range of tasks, including market orientation, long-term planning, environmental scanning, and many more. The competency approach places many emerging farmers at one end of the farm entrepreneurship spectrum and commercial farmers at the other, both of whom lack these competencies (Sinyolo et al., Citation2017).

3.4. Empirical framework

The study used the two factors score regression (FSR): that is regression and Bartlett FSR, a single equation score-based latent variable regression, to identify the factors influencing the farm entrepreneurship of the emerging farmers under the land restitution program. Several literatures (Devlieger et al., Citation2015; Grice, Citation2001; Lu & Thomas, Citation2008; Sinyolo et al., Citation2017) used Bartlett factor score regression because the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) method is less intuitive and simple to use than single equation regressions. Furthermore, Miss specification errors do not occur with single equation when compared to SEM (Lu & Thomas, Citation2008). According to Skrondal and Laake (Citation2001) and Croon (Citation2002), biasness can be escaped or reduced while regressing factor scores. Skrondal and Laake (Citation2001) further reported that Bartlett FSR combined with regression, and it was called ‘bias avoiding’ approach, which resulted with consistent parameter estimates in some circumstances. Therefore, two factor score regression was used in this study because it can generate impartial estimates when factor score is used as an outcome variable, as in these studies (Devlieger et al., Citation2015; Lu & Thomas, Citation2008; Skrondal & Laake, Citation2001). Furthermore, the model is selected because factor scores are generated using maximum likelihood estimates, ‘a statistical procedure that produces estimates that are the most likely to represent the "true" factor scores’ (DiStefano et al., Citation2009). The procedure perfectly fits the study data because researchers intended to withdraw some components for the purpose of data reduction and treat the remaining components as latent variables. Last but not least, two-factor score regression meets the needs of the study objective, which is to identify the factors influencing farm entrepreneurship. The model is split into two stages: the first stage uses principal component analysis (PCA) to create an index of farm entrepreneurship. PCA is used because it has unique determinants and creates factor scores that are unique to avoid the problem of indeterminacy. Additionally, PCA is known for generating higher values of multiple correlation, which suggest better validity and determinacy evidence for factor scores (Grice, Citation2001). The second stage computes the index as a dependent variable in linear regression (OLS).

3.4.1. The principal component analysis

The Bartlett FSR’s initial strategy focuses on using PCA to create an index of farm entrepreneurship. Several studies used an index to measure entrepreneurship (Ács & Szerb, Citation2007; Marcotte, Citation2012; Sinyolo et al., Citation2017). Various studies adopted PCA to create different indices (Boubker et al., Citation2022; Marijana et al., Citation2013; Mensah & Dadzie, Citation2020; Sinyolo et al., Citation2017; Zhao-Hui, Citation2018). Thus, this present study followed above-mentioned literature and adapted the use of PCA to combine the entrepreneurship indicators and determine the appropriate weights to construct many common entrepreneurship indices.

Starting with the first set of n correlated variables, PCA generates uncorrelated components, with each component being a linear, weighted combination of the initial variables (Jolliffe, Citation2002; Norman & Streiner, Citation2008).

PCA model is as follows:

(1)

(1)

where The weight for the dth principal component (PCd) and the nth variable is denoted by the symbol βdn.

The eigenvectors provide the weights for each principal component (PC) of the covariance matrix. The covariance matrix is used if the original data is measured in reasonable comparable units or scales (Morrison, Citation2005; Vyas & Kumaranayake, Citation2006). In contrast, the correlation matrix is chosen when the variables are measured using different scales or units (Morrison, Citation2005). The conforming eigenvalue of the conforming eigenvector displays the variance (λ) for each PC. The PCs are arranged, and PC1 can, with the following limitations, explain most of the variation in the initial data:

(2)

(2)

In the OLS model, PC1 was chosen as the dependent variable and is described below.

3.4.2. Variable descriptions and ordinary least squares regression used in the model

OLS identified factors influencing farm entrepreneurship. The estimate of OLS is:

(3)

(3)

where B0 and Bi are the vectors of parameters to be estimated, χi is a vector of explanatory variables, and εi is the residual term. U*i is the farmer’s entrepreneurship index.

For comparison purposes, Hoff (Citation2007) suggested that EquationEquation (3)(3)

(3) can be projected in a similar manner using the 2 limit Tobit model (Greene, Citation2003). The PCA-produced entrepreneurship index may be viewed as a turning justification, be it guaranteed on its higher and smaller limits. This makes the Tobit model relevant (Sinyolo et al., Citation2017). There was no evidence of selection bias when B1 and εi were correlated using Heckman’s two-stage approach (Heckman, Citation1979). To examine any potential endogeneity between χI and εi the Hausman test was carried out (Hausman, Citation1978). Variables such as farming experience, education level, extension services and other demographic characteristics were included in the model because they influence farm entrepreneurship.

portrays variables included in the OLS and the summary statistics of the sampled emerging farmers. The farmers were male in majority (about 58%) and had an average age of 47. Furthermore, about 56% of the emerging farmers had tertiary qualifications and 6 years farming experience. Approximately 49% of the farmers were residing in Capricorn district and survived by social grants as their main source of income. About 49% of the farmers raised livestock, and they owned an average of 2 ha of land. While 48% of emerging farmers had access to extension services that included access to credit and market information, over 90% of farmers agreed to be using modern technology and 40% of them owned transport for agricultural purposes. Very few farmers, about 25%, were members of the farmers’ association and only 15% had non-farm businesses.

Table 1. Variables included in the OLS model.

4. Results

4.1. Summary statistics on the entrepreneurial abilities and skills that emerging farmers possess

and show frequency of the entrepreneurial competencies and skills possessed by emerging farmers. The results revealed a low level of farm entrepreneurship because less than 60% of farmers agreed or strongly agreed that they possessed these traits. Results further indicated that 50% of farmers were more passionate about their farm businesses and made use of advanced technology to improve their productivity. In addition, less than 50% of them were market orientated and able to recognise market gaps. Only 39% indicated they were risk takers, with 34% being able to scan the environment pertaining to farm businesses. Nonetheless, farmers indicated they possessed communication and persuasive competencies, as well as willingness to learn new things, and were good at negotiating deals concerning their farm business. Furthermore, over 60% of respondents indicated they take accountability of everything concerning their farm businesses, and cope well emotionally.

Table 2. Frequencies of entrepreneurship competencies.

Table 3. Frequencies of entrepreneurship competencies.

4.2. Principal component analysis used to determine farm entrepreneurship index

The correlation matrix’s findings showed that the entrepreneurship variables were correlated to varying degrees. The correlation matrix clearly met the prerequisite for a successful factor extraction because all of the correlation coefficients except for financial skills and goal setting were greater than 0.3 and 0.2 (Morrison, Citation2005; Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2001). According to the Bartlett’s test of sphericity, which demonstrated high significance (χ2=15.8695, P = 0.0000), it is extremely unlikely that the correlation matrix was obtained from a population with zero correlation (Sinyolo et al., Citation2017). The measure of sampling adequacy, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO), was 0.712 greater than 0.5 which is regarded appropriate (Boubker et al., Citation2022), indicating good inter-relationship among the variables. A valid principal component analysis was completed according to the Bartlett test and correlation matrix. The three principal components (PC) with Eigen values greater than one were kept using the Kaiser Criterion Field (Field, Citation2005) and accounted for roughly 71% of the data variance. shows the entrepreneurship index generated by PCA. The first principal component (PC1) accounted for 52% of the variation and all variables in PC1 were positively correlated. This shows how these 25 entrepreneurship competencies and skills vary when taken as a whole, emphasizing the idea that as one rises, so do the others. Few variables were loaded heavily in PC2 and PC3, then PC1 consequently developed the entrepreneurship index used in OLS.

Table 4. Entrepreneurship index generated by PCA.

4.3. Factors influencing farm entrepreneurship of emerging farmers under the land restitution program

Factors influencing farm entrepreneurship amongst emerging farmers under the land restitution program are shown in . These factors were estimated using ordinary least square (OLS). The dependent variable was the entrepreneurship index produced by PCA. The OLS model correctly predicted the data (F value = 0.0033), showing the independent variables’ significant impact on farm entrepreneurship. Based on the results of the variance inflation factors (VIF), which ranged from 1.07 to 2.99 and averaged 1.64, there was no absolute correlation. The results of the OLS model did not encounter sample selection bias because the Heckman’s two-step method did not reveal any evidence of selectivity bias. The Hausman test found no evidence of endogeneity between farm entrepreneurship and the land restitution program (land size).

Table 5. Factors influencing farm entrepreneurship: OLS model.

Seven of the fifteen explanatory variables included in the regression model had a statistically significant effect on farm entrepreneurship. The variables were the age of the farmer (AGE), location (LOCATI), enterprise produced (ENTPRI), innovation technology (INNTEC), extension services (EXTSER), market information MRKINF, and association membership (ASSOCI).

5. Discussion

Successful farmer-entrepreneurs are normally competent, innovative, and able to plan ahead so they can steer their farm businesses through the different stages. Less than 60% of the emerging farmers believed they possessed entrepreneurial competencies and skills, with the exception of communication and persuasion, willingness to learn new things, negotiation, emotional coping, and accountability, which is why the results showed low levels of farm entrepreneurship. The results concur with Sinyolo et al. (Citation2017) who reported that competencies and skills barely over 60% are regarded as low levels of farm entrepreneurship. There are numerous reasons and factors contributing to low level of farm entrepreneurship in the developing countries. Basic reasons include lack of capital to start and maintain businesses and inaccessibility to target markets, which may result in business failures even before getting started or a year after the first investment.

The findings showed a negative relationship between farmers’ age (AGE) and farm entrepreneurship, emphasizing that each additional year of a farmer’s age may cause the level of entrepreneurship to drop. This implies that older farmers are less entrepreneurial than younger farmers. The results of Man et al. (Citation2008) and Rudmann (Citation2008) agree with the finding. The finding may be explained by the fact that young farmers are more tenacious, adaptable, and receptive to novel ideas than their more experienced counterparts (Rudmann, Citation2008). Farmers’ location (LOCATI) variable suggests that location and farm entrepreneurship have a positive relationship. This finding suggests that emerging farmers located in the Capricorn district are more entrepreneurial than those in the Sekhukhune and Waterberg districts. The reason might be that Capricorn district is close to Polokwane, the capital city of Limpopo Province, where numerous agricultural markets are located for farmers to sell their produce.

Farm entrepreneurship was positively correlated with the variable enterprise (ENTPRI). This implies that livestock emerging farmers are more entrepreneurial due to their participation in livestock auctions, which is their main source of market. The belief is auction markets are more profitable than any other market in the commodity marketing system because there are less middlemen involved. Sinyolo et al. (Citation2017) also found that livestock production has a favourable impact on rural farmers’ farm entrepreneurship. Similarly, innovation technology (INNTEC) positively influenced farm entrepreneurship at 5% level of significance. Emerging farmers using modern technology are more entrepreneurial than their counterparts. This finding is accurate because there were advanced technologies introduced into agricultural sector to improve and increase agricultural production to enable emerging farmers to become more entrepreneurial by participating in output markets.

Access to support services is important in stimulating farm entrepreneurship in the farming sector. The results also show a positive relationship between farm entrepreneurship and support service factors such as extension services (EXTSER), market information (MRKINF) and farmer association membership (ASSOCI) at 1%, 5%, and 10% significant levels respectively. This implies that emerging farmers having access to this support services are more likely to be entrepreneurs. Kahan (Citation2013) supports these findings and claims that effective use of extension services can improve rural entrepreneurship and that extension is essential in promoting rural farm entrepreneurship. With regards to farmers association membership, associations offer a platform for emerging farmers to share knowledge, skills, and opportunities in agriculture; this is where farmers learn how to become more entrepreneurial and to treat their farming as a business rather than just a practice.

6. Conclusions and recommendations

Entrepreneurship is often seen as a drive to improve the standard of living for individuals, households and communities and sustain a well-functioning economy and environment. This paper empirically investigated the factors influencing farm entrepreneurship of emerging farmers under the land restitution program in Limpopo Province, South Africa, a topic that has not yet been sufficiently explored. The findings show low farm entrepreneurship amongst emerging farmers in the Limpopo Province. The OLS findings revealed that age of the farmer negatively influenced farm entrepreneurship, while location, enterprise farming, innovation technology, extension officers, market information, and farmer associations positively influenced farm entrepreneurship. Based on the findings, the null hypothesis should be accepted because the results from the OLS model showed no significant statistical relationship between land size and farm entrepreneurship.

The study calls for the establishment of supportive policy environments for the growth of business mindset among emerging farmers. Market information, extension services and farmer association remain the most sensitive and vital factors affecting farm entrepreneurships. Since extension services and farmer association are regulated by government policy, this implies that government policies and interventions are considered as vital factors motivating entrepreneurship success in rural areas. Therefore, the study recommends that government develops policies that focuses more on the provision of extension services to emerging farmers and support of farmer associations. Extension services should incorporate appropriate and focused entrepreneurship training informed by skills and competency shortages among farmers in rural areas and market support to enhance farm entrepreneurship amongst the farmers in rural areas. Policies to improve farmer ‘s entrepreneurial competencies by government have an effective role in improving and expanding entrepreneurship in farming sectors to enhance sustainable, profitable, and market-oriented farm businesses in South Africa. The study suggest that future research look at the impact of post settlement support on farm entrepreneurship using comparative study about farm entrepreneurship among land restitution beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries.

Institutional review board statement

The Ethics Committee of Tshwane University of Technology approved the study’s conduct on November 12, 2020 (FCRE 2020/10/012) (FCPS 02) (SCI), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s rules.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Limpopo DALRRD for the support provided for this project. There is also appreciation given to the Tshwane University of Technology and NRF for the scholarships and the financial assistance.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The corresponding author can provide the data presented in this study upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lesedi Molefe Maesela

Ms. Lesedi M. Maesela is currently a doctoral student at the Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria Campus, South Africa. Her research interests include land reform, farm entrepreneurship, food security, marketing, and value addition.

Grany Mmatsatsi Senyolo

Dr Grany M. Senyolo is an agricultural economics lecturer at the Tshwane University of Technology. Her research interests include underutilized plant species, food security, agricultural and rural development, and agro-processing.

Abenet Belete

Prof Abenet Belete is a Professor at the University of Limpopo. His research focus is on production economics, economics of agricultural research, farmer decision making, mathematical programming, and rural development.

References

- Ács, Z. J., & Szerb, L. (2007). The Global Entrepreneurship Index (GEINDEX). Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 5(5), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000027

- Alvarez-Risco, A., Mlodzianowska, S., García-Ibarra, V., Rosen, M. A., & Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S. (2021). Factors affecting green entrepreneurship intentions in business university students in COVID-19 pandemic times: Case of Ecuador. Sustainability, 13(11), 6447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116447

- Bergevoet, R. H. M., Giesen, G. W. J., Saatkamp, H. W., van Woerkum, C. M. J., & Huirne, R. B. M. (2005). Improving entrepreneurship in farming: The impact of a training programme in Dutch dairy farming. Paper Presented at the 15th Congress – Developing Entrepreneurship Abilities to Feed the World in a Sustainable Way, Sao Paulo, Brazil, August 2005.

- Boubker, O., Naoui, K., Ouajdouni, A., & Arroud, M. (2022). The effect of action-based entrepreneurship education on intention to become an entrepreneur. MethodsX, 9, 101657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2022.101657

- Bowmaker-Falconer, A., & Herrington, M. (2020). Igniting startups for economic growth and social change: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor South Africa (GEM SA) 2019/2020 report. Stellenbosch University and Global Entrepreneurship Monitor South Africa (GEM SA).

- Cai, X., Magidi, J., Nhamo, L., & van Koppen, B. (2017). Mapping irrigated areas in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. International Water Management Institute (IWMI). Working Paper. 172, 37.

- Chandramouli, P., Meti, S. K., Hirevenkangoudar, L. V., & Hanchinal, S. N. (2007). Comparative analysis of entrepreneurial behaviour of farmers in irrigated and dry land areas of Raichur District of Karnataka. Karnataka Journal of Agricultural Science, 20(2), 320–222.

- Chitonge, H. (2022). Resettled but not redressed: Land restitution and post-settlement dynamics in South Africa. Journal of Agrarian Change, 22(4), 722–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12493

- Commission on the Restitution of Land Rights (CRLR). (2000). Annual report. Department of Agriculture and Land Affairs, South Africa.

- Commission on the Restitution of Land Rights (CRLR). (2016). 2015/2016 annual report. CRLR.

- Croon, M. (2002). Using predicted latent scores in general latent structure models. In Marcoulides, G.A. & Moustaki, I. (eds.), Latent variable and latent structure models. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Darmadji, P. 2016. Entrepreneurship as new approach to support national agriculture development program to go self sufficient food. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia, 9, 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aaspro.2016.02.128

- de Wolf, P., & Schoorlemmer, H. (Eds.). (2007). Exploring the significance of entrepreneurship in agriculture. Research Institute of Organic Agriculture.

- Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF). (2011). South African agricultural production strategy. Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF).

- Department of Land Affairs (DLA). (1997). The white paper on South African land policy. South Africa.

- Devlieger, I., Mayer, A., & Rosseel, Y. (2015). Hypothesis testing using factor score regression: A comparison of four methods. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 76(5), 741–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164415607618

- DiStefano, M., Zhu, D., & Mîndrilã, C. (2009). Understanding and using factor scores: Considerations for the applied researcher. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 14(20), 1–11.

- Field, A. (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS. Sage.

- Filion, L. J. (2011). Defining the entrepreneur. In Dana, L.-P. (ed.), World encyclopedia of entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar.

- Gray, C. (2002). Entrepreneurship, resistance to change and growth in small firms. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 9(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000210419491

- Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Grice, J. W. (2001). Computing and evaluating factor scores. Psychological Methods, 6(4), 430–450.

- Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46(6), 1251–1271. https://doi.org/10.2307/1913827

- Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912352

- Herrington, M., Kew, J., & Kew, P. (2015). GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor) South Africa Report 2014. South Africa: The Crossroads – A Goldmine or a Time Bomb? http://www.gemconsortium.org/country-profile/108

- Hoff, A. (2007). Second stage DEA: Comparison of approaches for modelling the DEA score. European Journal of Operational Research, 181(1), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2006.05.019

- Jill, K. R., Thomas, P. C., Lisa, G. K., & Susan, S. D. (2007). Women entrepreneurs preparing for growth: The influence of social capital and training on resource acquisition. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 20(2), 169–181.

- Jolliffe, I. T. (2002). Principal component analysis (2nd ed.) Springer Verlag.

- Kahan, D. (2013). Farm management extension guide: Entrepreneurship in farming. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- Khayri, S., Yaghoubi, J., & Yazdanpanah, M. (2011). Investigating barriers to enhance entrepreneurship in agricultural higher education from the perspective of graduate students. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 2818–2822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.195

- Limpopo Provincial Government. (2022). About Limpopo: Provincial economy and investment. http://www.limpopo.gov.za/?page_id=3396.

- Lu, I. R. R., & Thomas, D. R. (2008). Avoiding and correcting bias in score-based latent variable regression with discrete manifest items. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 15(3), 462–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510802154323

- Man, T. W. Y., Lau, T., & Chan, K. F. (2002). The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises: A conceptualization with focus on entrepreneurial competencies. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00058-6

- Man, T. W. Y., Lau, T., & Snape, E. (2008). Entrepreneurial competencies and the performance of small and medium enterprises: An investigation through a framework of competitiveness. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 21(3), 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2008.10593424

- Marcotte, C. (2012). Measuring entrepreneurship at country level: A review and research agenda. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(3–4), 174–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2012.710264

- Marijana, Z. S., Natasa, S., & Sanja, P. (2013). Combining PCA analysis and artificial neural network in modelling entrepreneurial intensions of students. Croatian Operational Research Review, 4(1), 306–317.

- Masuo, D., Fong, G., Yanagida, J., & Cabal, C. (2001). Factors associated with business and family success: A comparison of single manager and dual manager family business households. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 22(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009492604067

- McElwee, G. (2006). Farmers as entrepreneurs: Developing competitive skills. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 11(03), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946706000398

- Mensah, A. C., & Dadzie, J. (2020). Application of principal component analysis on perceived barriers to youth entrepreneurship. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 9(5), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20200905.13

- Morrison, D. F. (2005). Multivariate statistical methods (4th ed.). Duxberry Press.

- Norman, G. R., & Streiner, D. L. (2008). Biostatistics: The bare essentials. Pamph.

- Orser, B. J., Hogarth-Scott, S., & Riding, A. (2000). Performance, firm size and management problem solving. Journal of Small Business Management, 38(4), 42–58.

- Phelan, C., & Sharpley, R. (2012). Exploring entrepreneurial skills and competencies in farm tourism. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 27(2), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094211429654

- Restitution of Land Rights Act 22. (1994). South Africa. Government Gazette of Republic of South Africa.

- Rijkers, B., & Costa, R. (2012). Gender and rural non-farm entrepreneurship. World Development, 40(12), 2411–2426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.017

- Robichaud, Y., McGraw, E., & Alain, R. (2001). Toward the development of a measuring instrument for entrepreneurial motivation. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 6(45), 189–197.

- Rudmann, C. (Ed.). (2008). Entrepreneurial skills and their role in enhancing the relative independence of farmers. Results and recommendations from the research project developing entrepreneurial skills of farmers. Research Institute of Organic Agriculture.

- Saghaian, S., Mohammadi, H., & Mohammadi, M. (2022). Factors affecting success of entrepreneurship in agribusinesses: Evidence from the city of Mashhad, Iran. Sustainability, 14(13), 7700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137700

- Sánchez, J. (2012). The influence of entrepreneurial competencies on small firm performance. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 44(2), 167–177.

- Schröder, L. M., Bobek, V., & Horvat, T. (2021). Determinants of success of businesses of female entrepreneurs in Taiwan. Sustainability, 13(9), 4842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094842

- Setia, M. S. (2016). Methodology series module 3: Cross-sectional studies. Indian Journal of Dermatology, 61(3), 261–264. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5154.182410

- Sinyolo, S., Mudhara, M., & Wale, E. (2017). The impact of social grant-dependency on agricultural entrepreneurship among rural households in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of Developing Areas, 51(3), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.2017.0061

- Skrondal, A., & Laake, P. (2001). Regression among factor scores. Psychometrika, 66(4), 563–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296196

- Staniewski, M. W. (2016). The contribution of business experience and knowledge to successful entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5147–5152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.095

- Stefanovic, I., Prolix, S., & Rankovic, L. (2010). Motivational and success factors of entrepreneurs: The evidence from a developing country. Journal of Economics and Business, 28(2), 251–269.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate analysis. Allyn and Bacon.

- Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge University Press.

- Vesala, K.M.; Pyysiäinen, J. (Eds.). (2008). Understanding entrepreneurial skills in the farm context. Research Institute of Organic Agriculture.

- Vyas, S., & Kumaranayake, L. (2006). Constructing socioeconomic status indexes: How to use principal component analysis. Health Policy and Planning, 21(6), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czl029

- Zangirolami-Raimundo, J., Echeimberg, J. O., & Leone, C. (2018). Research methodology topics: Cross sectional studies. Journal of Human Growth and Development, 28(3), 356–360. https://doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.152198

- Zhao-Hui, G. (2018). Etrepreneurial competency evaluation of knowledge-intensive teams based on PCA method. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 423, 012076. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/423/1/012076