?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Rural-urban migration affects development in both the rural and urban areas of Ethiopia, particularly in southern Ethiopia. This has been assumed to be a central continuous issue in Ethiopia’s development policy. Despite the good potential of agricultural production in Ethiopia, reducing rural-urban migration is unsatisfactory. Therefore, this study attempts to investigate the determinants of rural-urban migration in southern Ethiopia, evidence from Duna district using cross-sectional field survey data was collected from 187 sample households in 2021/22. Primary and secondary data were collected in this study. Descriptive and binary logistic regression methods were employed for the data analysis. The results of binary logistic regression analysis showed that age, educational status, landholding, credit use, soil infertility, access to information, off-farm activity, attitude of rural area and distance to the nearest town were the factors significantly driving rural-urban migration. The results show that rural household food insecurity and poverty at the household level due to lower income could lead to rural-urban migration. Therefore, concerned bodies such as government organizations, non-government organizations, stakeholders and policymakers should pay considerable attention to rural-urban migration, which is a crucial base for driving food security and alleviating poverty. The summary of rural-urban migration by policymakers and plan designers could help alleviate household food insecurity and poverty in the study area.

IMPACT STATEMENT

This study investigates the determinants of rural-urban migration in Duna district, Southern Ethiopia. Several households in the Southern Ethiopia support rural-urban migration as a tactic to fight poverty and food insecurity. Migration, particularly in rural-urban, is affected by several factors and influences sending communities positively and negatively. However, this study shows that rural-urban migration is still a challenges Ethiopia in general and particularly in southern Ethiopia. Rural-urban migration, however, contributes to the spread of diseases; socio-culturally undesirable habits produce dysfunctional families and other societal ills. Particularly, to manage rural-urban migration, policymakers need analytical data on the causes and determinants of rural-urban migration. To this end, our study quantifies the issues and offers specific recommendations.

REVIEWING Editor:

1. Introduction

Rural-urban migration is a rapid, permanent or temporary geographic movement of people from rural to urban areas due to rural push and urban pull factors (Abeje, Citation2021). There are various push and pull factors compelling rural settlers to migrate (Asfaw el al., Citation2010; Fetagn, Citation2017). Push factors are the negative characteristics of the place of origin whereas pull factors are the positive characteristics at the point of destination. The poor economic opportunities, unequal landholdings, low agricultural yields, costly agriculture, inadequate household income, parenting style, low employment opportunities, large family size, insufficient educational and healthcare facilities, religious or political discrimination, marital status, and poor rural social services and amenities, and insecurity, force rural settlers to move toward cities. Nonetheless, migration theory suggests that better economic opportunities, urban job opportunities, improved infrastructure, pear influence, better urban income, education and healthcare facilities, religious or political freedom, a relatively moderate atmosphere, recreational facilities, security, better urban social services and amenities, and independent living act as the pull factors (Obijekwu et al., Citation2019). Migrants move to improve their living conditions create overcrowding of cities, suffer from urban poverty and remain unsatisfied (Ahmed & Ishrat, Citation2020). Nonetheless, studies suggest that major push factors of migration to cities include: uncertain income levels, labor demand from industry, expensive agricultural production, unequal landholdings, oppressive lifestyle and poor health conditions (Hussain, Citation2016; Rana & Bhatti, Citation2018). It is a rapid shift in the response of people to improve economic and non-economic welfare in urban areas (Dazhuan et al., Citation2020). In developing countries, including Ethiopia, rural-urban migration is an accessible employment and wage opportunity to move out of food insecurity and poverty (Eshetu & Beshir, Citation2017). For several decades, many people in Ethiopia have faced severe food insecurity and poverty challenges, particularly, in rural areas. This leads to several people migrating from rural to urban areas to search for better jobs, which in turn reduces poverty and food insecurity (FAO, Citation2019). Poverty and food insecurity in rural Ethiopia are highly related to landlessness, insufficient productivity and productive assets, low-income status, shortage of availability of food, poor educational status, marginalization, poor health and basic services and inappropriate job opportunities (Agza et al., Citation2021; Assefa & Eshetu, Citation2017). The poverty level, low income status, infertile landholding, ecological degradation, drought, inappropriate government policies and declining job opportunities are key motivators of rural-urban migration in southern Ethiopia (Zerga et al., Citation2021). In the country, the level of rural-to-urban migration during the last three decades has increased due to political instability, declining agricultural productivity, and inappropriate government policies (Assefa & Eshetu, Citation2017). In particular, Ethiopians driving food security and poverty alliance policies highly depend on the agricultural sector (Central Statistical Agency [CSA], Citation2017). Despite its potential, the agricultural sector faces low productivity (Debelo, Citation2015) and is unsatisfactory with population pressure (Central Intelligence Agency [CIA], Citation2018; CSA, Citation2018). This means that Ethiopia dominates a major portion of the population with low yield (CSA, Citation2019). Therefore, this low agricultural production and productivity drive internal migration, such as rural-urban migration, to search for food and leave poverty (CIA, Citation2018; CSA, Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2019).

In Ethiopia, with rising migration towards urban areas, various macroeconomic and socioeconomic problems such as urban poverty, overpopulation, environmental pollution, deprivation of education and health, poor sanitation, over-crowded housing, congested traffic, road accidents and crimes are increasing (Latif & Yu, Citation2020). Other urban growth challenges include the conversion of farmlands into residential schemes, squatter settlements, deficient services and the unavailability of clean drinking water (Khan et al., Citation2014). A large number of rural residents have moved to the cities, and have undergone structural changes resulting in high density and pressure on infrastructure, resources and urban land. The urban growth in Ethiopia has brought a variety of urban environmental annoyances, i.e. untreated industrial and municipal waste, uncollected solid waste, traffic congestion and vehicle exhaust posing serious health risks to the city dwellers (Malik et al., Citation2020). The cities of Ethiopia are also facing challenges of inadequate infrastructure and urban management capacities. Water supply, sanitation and waste management services are unreliable (Rana & Bhatti, Citation2018). The aquifers are also over-exploited. The housing facilities are also incapacitated by the growing population. This widespread under-performance in service delivery and incapacitation of infrastructure affect living conditions, and limit business growth reducing the productive potential of cities (Naghmana et al., Citation2021). The theoretical foundations of rural-urban migration and urbanization are based on the theories of different economists and demographers. Rural-urban migration is mostly driven by economic factors and greater economic opportunities (Fasil & Mohammed, Citation2017). The surplus labor is the driving force of rural-urban migration (Malik et al., Citation2020). However, the presence of surplus labor alone does not explain rural-urban migration. Rural-urban migrants do not need to get jobs immediately after arriving in the cities. There are chances that on entering the urban labor market, migrants either stay unemployed, semi-employed, or seek part-time jobs in the informal sector. Moreover, their expectation of a high wage differential does not come true. Socio-cultural factors at in the area of origin must be taken into account to explain the behavior of rural-urban migrants (Ahmed & Ishrat, Citation2020). Rural-urban migrants choose the destination area by making a cost-benefit analysis (Assefa & Eshetu, Citation2017). They move only if the expected future returns are positive. From the perspective of non-equilibrium models, economic factors were emphasized as the sole driver of rural-urban migration.

Rural-urban migration is common in Ethiopia because of consecutive factors such as rural push and urban pull factors. Rural push factors have been strong driving forces for the rapid shift of people from rural to urban areas (Abeje, Citation2021). In particular, there is high population pressure through birth rate, conflicts, pest infestation, drought, lack of relief assistance, lack of access to credit use, absence of non-farm, shortage of food availability, land degradation, high unemployment level, poverty, shortage of housing, poor or traditional cultural practices, high cost of living and poor access to social services is the major existed challenges (Obijekwu et al., Citation2019). Rural-urban migration is importantly expressed by rural push and urban pull factors (Birhanu & Nachimuthu, Citation2017). People are pushed by problems to leave their living places due to few job opportunities, lack of enough productive resources, conditional climatic variation related to issues such as drought, famine, degradation, and desertification, lower real income, lower cereals and cash crop yield, shortage of landholding and low level of employment opportunities or aspects which significantly presents negative rural situations that leads the rural people decision to migrates into urban areas (Birhanu & Nachimuthu, Citation2017; Markos & Gebre-Egziabher, Citation2001). While pull factors are an attraction to urban places due to high wages, high employment opportunities or perspectives, attitudes toward urban life, access to information, access to services, network in the destination, years of schooling and better availability of food (Carson, Citation2019).

Rural-urban migration is a major problem in Ethiopia and has different causes, which are attributed to rural poverty in rural areas (Atnafu et al., Citation2014). In Ethiopia, shortage of landholding, poverty, drought, and high population pressure have led to a decline in subsistence agricultural productivity, and walking in rural areas is a driver of migration. In particular, increasing the informal sector and wealth accumulation has enhanced the demand for labor and employment opportunities in urban places compared to subsistence agriculture, which has attracted significant attention from rural to urban areas (Hashim & Thorsen, Citation2011). In addition, economic and socio-cultural factors such as early marriages and gender-based abuse motivate a welfare strategy for wages, and employment in urban areas is most important to respond to poverty issues in rural areas (Baker, Citation2012; Ellis, Citation2003; Kothari, Citation2002; Skeldon, Citation2002). In their studies (Fasil & Mohammed, Citation2017), the basic characteristics of rural-urban migrants and factors affecting rural-urban migration in southern Ethiopia used 665 sample migrants. For their studies, descriptive and probit regression data analyses were employed. Their study results showed that young, educated, and unmarried people tended to be more mobile. Additionally, the probit regression results showed that age, family size, educational status and monthly income were important factors affecting rural-urban migration. (Niels et al., Citation2015), on the rural-urban migration in Ethiopia applying a descriptive data analysis approach to rural-urban migration in Ethiopia. The descriptive findings revealed that rural-urban migrants are better than their counterparts in terms of educational status and wage levels. The results also showed that more educated people migrated than non-educated people, which benefited more people from rural-urban migration. A study conducted in the Wollo Zone in the Amhara region, Ethiopia, indicated that several migrants were unmarried, and the majority of them were formally educated and males (Birhanu, Citation2011).

Understanding the determinants underlying rural-urban migration is important for reducing food insecurity and poverty through increased agricultural productivity. An important growing body of empirical literature focuses on the determinants affecting rural-urban migration (Abeje, Citation2006; Agza et al., Citation2021; Amrevurayire & Vincent, Citation2016; Assefa & Eshetu, Citation2017; Asfaw et al., Citation2010; Birhanu & Nachimuthu, Citation2017; Birhanu, Citation2011; Fasil & Mohammed, Citation2017; Markos & Gebre-Egziabher, Citation2001; World Bank, Citation2010). Particularly, several studies have significantly focused on the different aspects of rural-urban migration. However, some of these studies were limited in their ability to identify the determinants of rural-urban migration. Hence, the results have often been mixed and conflicting (Baker, Citation2012; Ellis, Citation2003; Kothari, Citation2002; Skeldon, Citation2002). Their findings showed that migrants bring back new skills, knowledge, attitudes, technologies and productivity and improve income diversification to the original rural places from which they migrated to urban areas. Therefore, this study attempts to investigate the determinants that affect rural-urban migration in the Duna district in the Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Specifically, to investigate the challenges and key determinants of rural-urban migration, migrant and non-migrant people are facing and to investigate the attitudes and trends of rural-urban migrants and non-migrants towards migration in the study area.

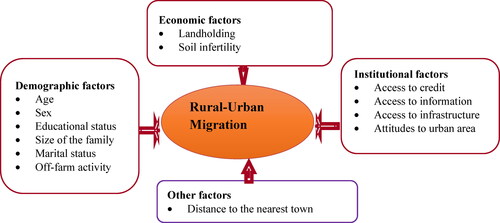

The current research study’s estimation strategy was based on a conceptual framework. The current research study’s conceptual framework was conducted and modified according to a review of the empirical literature (Ishtianque & Ullah, Citation2013). This study’s conceptual framework, presented in , revealed that rural-urban migration characteristics such as age, sex, educational level, family size, marital status, off-farm activity, economic factors such as landholding, soil infertility, institutional factors such as credit use, availability of information, access to infrastructure and attitudes of urban places; other factors such as distance to the nearest town are the most important factors that affect rural-urban migration. The presented conceptual framework showed the most crucial factors and their associations with each other, which are expected to determine rural-urban migration. The conceptual framework is shown in .

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

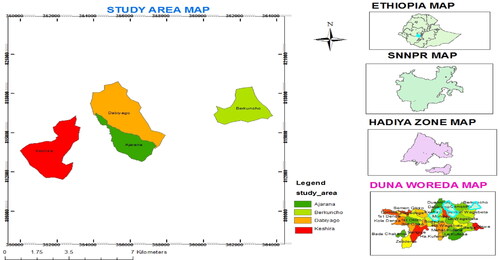

The research was conducted in the Duna district, located in the Hadiya Zone, southern national nationalities, and people region of Ethiopia. The total number of households in the study district was 18,752 (100%), of which 18,109 (95.57%) were male-headed and 643 (3.43%) were female-headed. The total number population of the study district is 148,566 (100%), out of these, 75,383 (50.74℅) are male and 73,183 (49.26%) are female. Duna District is located 270 km south of Addis Ababa, 211 km southwest of Hawassa and 42 km south of Hossana. The Duna district lies between 7° 37′19″ N latitude and 37° 37′ 14″ E longitudes. Duna district was agroecologically categorized into three categories dega (85%), weina dega (10%) and kola (5%). The mean yearly rainfall varies from 1500 to 1896 mm with a mean annual temperature of 19 °C. The total land elevation in Duna district ranges from 2970 to 1000 m asl. The total land area of the Duna district is 43,104 ha (222.57 s/km) of which 30,172.8 ha (70%) is potentially cultivated land, and the remaining part of the district is uncultivated, grazing land and forest occupied. The population density in Duna district is 619.58 per s/km. The Duna district is bordered by Soro woreda in the north and east, Doyogena woreda in the South, and Omosheleko woreda in the west. In the district, there is high rural-urban migration. In particular, in the district, many people migrate to Hossana Town and Addis Ababa City to improve their livelihoods. Agriculture is the major activity of rural farmers in Duna District, with major wheat production. Wheat is an important cereal crop that plays a key role in the economic and cultural welfare of districts. The majority of farmers in the district are young wheat cultivators with suitable wheat farming reasons, such as high potential for wheat yields, introduction and application of wheat production technologies, and widely applicable extension of wheat cultivation applied in the Duna district () (Negese & Jemal, Citation2021).

2.2. Sampling technique

Mult-stage sampling was applied to select the sample respondents. In the first stage, the Duna district was purposely selected based on the status of rural-urban migration and the introduction and application of strategies to reduce rural-urban migration. In the Duna district, rural-urban migration is higher than in the remaining district in the Hadiya Zone (CSA, Citation2019). In the second stage, the high rural-urban migrants’ kebeles such as Ajarena, Kashira, Dabiyago and Barkuncho in the district were selected on the level and status of rural-urban migration (CSA, Citation2018; CSA, Citation2019). In the third stage, the number of households in the migration year 2021/22 was identified. The total number of households (2344) was selected from the total migrant kebeles stratified by rural-urban migration status. The sample size was developed by Yamane (Citation1973).

A total of 187 respondents were selected from each kebeles using proportionate selection procedures.

where ni is the number of samples selected from each

selected kebele, Ni is the number of households from the

selected kebele, N is the number of households in the selected kebele, e is an acceptable error margin and n is the total sample size. Finally, 187 sample respondents were selected from the four kebeles by applying simple random sampling techniques () (Negese & Sanait, Citation2023). This study used simple random sampling to reduce data bias involved during data collection.

2.3. Types and sources of data

In this study, primary and secondary data sources, as well as quantitative and qualitative primary data sets were applied. Primary data were collected from the demographic, economic, institutional and other characteristics of the study population. For the primary data collection, semi-structured questionnaires were administered to 187 sample households in Duna district, Southern Ethiopia. The semi-structural questionnaires developed were prepared considering demographic, economic, institutional and other determinants that affect rural-urban migration. Responsible persons were contacted to respond to questionnaires that had good knowledge and information about rural-urban migration. The developed questionnaires for primary data were distributed and collected at a later date after completion from March to July 2021/22. Supplementary data, such as secondary data, were collected from books, unpublished materials, published articles, the Internet, and empirical literature. The study was developed using survey data from the 2021/22 main migrating season.

2.4. Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using descriptive and binary logistic regression analyses. The descriptive analysis investigated demographic, socio-economic, institutional, and other characteristics of 1 the urban migration carried out using frequency, percentages, maximum values, minimum values, tables, averages, standard deviation, t-test and χ2-test. In particular, the study conducted χ two tests to investigate the relationship between rural-urban migration status and qualitative determinants. In addition, a t-test was applied to evaluate the association between rural-urban migration status and quantitative determinants. Furthermore, the study conducted a binary logistic analysis model to provide and check more appropriate in-depth analysis and to explore determinants that influence rural-urban migration and its level as well as status (Gujarati, Citation2004; Wooldridge, Citation2013). To evaluate the empirical relationship between dependent and independent variables, the study used a binary logit model, because the dependent variable rural-urban migration is a dummy variable 1 if people migrate and 0 otherwise. A binary logit model was used to investigate the determinants of rural-urban migration (Gujarati, Citation2004). Therefore, this study primarily focuses on investigating the determinants that influence rural-urban migration, which is important in determining the livelihood of both rural and urban areas. Therefore, the probability of migration is

(1)

(1)

Representation of people who migrated

(2)

(2)

where Pi is the probability status of the ith respondent not migrated, e is the base of natural logarithms (2.718), Xi is the dependent variable, n is the number of dependent variables, i = 1, 2, 3 …, n and α and βi are parameters to be estimated.

(3)

(3)

If Pi is the probability status of the migrated and (1-Pi) is the probability of not migrating.

(4)

(4)

Forming natural logarithm

(5)

(5)

Binary logistic regression model

(6)

(6)

This binary logistic regression model becomes

(7)

(7)

where

is the rural-urban migration status of household

, which takes the value of 1 if households are rural-urban migrants and 0 otherwise;

is a vector of covariates or explanatory variables such as demographic, socio-economic, institutional and other determinants that influence rural-urban migration ();

is the stochastic or error term of the model

; and

and

are model parameters to be investigated. The dependent variable of this study is dichotomous; binary logistic models are the most commonly used models to investigate 1 urban migration and its determinants.

(8)

(8)

Table 2. Description of independent variables.

The code of the independent variables used for the binary logistic regression is given as Age is age of household head, Sex is sex of household head, Fsize is size of family, Edu is educational status, Mas is marital status, Lah is landholding, Air is access to infrastructure, Soi is soil infertility, Aua is attitude of urban area, Acc is credit use, Aif is access to information, Ofa is off-farm activity and Dnt is the distance to the nearest town.

2.5. Description of explanatory variables

The econometric model for data analysis, such as the binary logistic model, investigates the factors that affect rural-urban migration. The dependent variable for the binary logistic regression is rural-urban migration. The dependent variable, rural-urban migration is a dummy it takes 1 if rural-urban migrants and zero otherwise. The demographic, economic, institutional and other determinants such as age, sex, educational status, size of family, marital status, landholding, access to infrastructure, soil infertility, attitude to urban area, credit use, availability of information, off-farm activity and distance to the nearest town are independent variables that influence rural-urban migration ().

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Descriptive analysis

shows a summary demographic, socioeconomic, institutional and other characteristic of migrants. Most of the rural-urban migrants were between 18 and 35 years of age. Youth appeared dynamic and skilled and were more enthusiastic to improve their conditions. They strive hard to improve their economic condition and move to areas where they can get more opportunities (Ahmed & Ishrat, Citation2020). The descriptive analysis in presents a summary of the rural-urban migration status in the study district. From a given total sample of 187 (100%), about 102 (54.55%) were migrants from rural-urban areas and 85 (45.45%) were non-migrants. This summary of descriptive analysis reveals that there was relatively larger rural-urban migration 102 (54.55%) than those who did not migrate 85 (45.45%) during the 2021/22 season. According to , there is high rural-urban migration due to high food insecurity and poverty in rural areas. The descriptive analysis results indicate that the major reasons for internal migration, such as rural-urban migration, are low job opportunities, poor access to infrastructure, poor availability of information, lack of access to credit use and low agricultural production and productivity. In addition, there is no suitable market for inputs, outputs and credit owing to the low infrastructure in the study district.

Table 3. Sample rural-urban migration status.

The descriptive summary presented the means, standard deviations and minimum and maximum values of the explanatory variables by achievement status in . This study used the t–test and χ2–test to evaluate the mean of the independent variables across 1 the urban migration and did not migrate. According to the descriptive data analysis results in , the size of family, landholding and distance to the nearest town from continuous explanatory variables and educational status, marital status, soil infertility, credit use, access to information and off-farm activity from dummy explanatory variables were significantly associated with household rural-urban migration. According to the results, the majority of households were more educated (64.20%). This finding is in line with that of Laura and Elisenda (Citation2016). The mean family size (5.31) per household implies that there is a significant average variation in family size between migrant and non-migrant households. Hence, the average family size of migrant households is higher than that of non-migrant households. It shows that large family size acts as a push factor for rural-urban migration This result is similar to that of Herrera and Sahn (Citation2013). The landholding was used as an indicator of household wealth, with an average landholding of 2.27 hectares of land. The mean distance from the nearest town was 3 km. In addition, the majority (63%) of respondents were married and had access to credit (51.38%) and information (68%). This finding is similar to that of Assefa and Eshetu (Citation2017). As mentioned (54%) on average, soil infertility and (53%) households were participants in off-farm activity. This finding is consistent with the findings of (Amrevurayire & Vincent, Citation2016; Assefa & Eshetu, Citation2017; Asfew et al., 2010; Birhanu & Nachimuthu, Citation2017). Particularly, the summary of descriptive analysis results showed that rural-urban migration in the study area was largely related to average large family size, more literate household heads, married people, high soil infertility, good attitude to urban areas, appropriate credit access to use, certain information, high participation in off-farm activities and distance from town places. Furthermore, all the above-listed explanatory variables were statistically significant at the 1% probability level.

Table 4. Descriptive analysis for explanatory variables.

3.2. Econometric results

According to the binary logistic regression function, out of 13 independent variables in function nine (age, education status, landholding, soil infertility, attitude of urban area, use of credit, access to information, off-farm activity and distance to the nearest town) influenced rural-urban migration. Among all significant explanatory variables education status of the household head, soil infertility, attitude of the urban area, credit uses, access to information and off-farm activity affect rural-urban migration at a 1% statistical significance level. Rural-urban migration is also significantly influenced by age, landholding, and distance to the nearest town at a 5% statistical significance level. The rural-urban migration elasticity concerning age, education status, soil infertility, the attitude of the urban area, use of credit, access to information and off-farm activity shows that as all listed explanatory variables increase, rural-urban migration will increase. Rural-urban migration increases access to information, education status, soil infertility, credit use, distance to the nearest town and off-farm activity on average for 1 the urban migration by 1%, they can increase the status of rural-urban migration by 35.72%, 32.41%, 31.27%, 30.25%, 29.14% and 22.54%, respectively. In addition, increasing landholding and distance to the nearest town, on average, will decrease the decision to participate in rural-urban migration. This reveals that there is a high potential for rural-urban migration in the study district ().

Table 5. Estimates of determinants of rural-urban migration (n = 187).

The binary logistic regression model investigates the determinants that influence rural-urban migration decisions to improve livelihoods as presented in . Specifically, the goodness fit of the migrantsʼ status concerning predictive rural-urban migration was significantly high, with 158 (84.49%) of the 187 (100%) rural-urban migrant samples included in the binary logistic regression model perfectly predicted.

According to , from a total of 13 independent variables, nine independent variables, such as age, education status, landholding, soil infertility, attitude of urban area, use of credit, access to information, off-farm activity and distance to the nearest town, were found to have a strong association with the status of rural-urban migration. Specifically, the age of the household head was indicated to have a better positive association with rural-urban migration. Therefore, keeping all other things constant, an extra year of sample household head age is expected to be found in a 7.43% increase in the probability of rural-urban migration (p < 0.01). Moreover, migrants who are on average 10 years old are 74.3% more likely to migrate from rural to urban areas than non-migrants, and age is a scientific driver of rural-urban migration. This binary logistic regression result is similar to those of (Francesco, Citation2018; Kangmennaang et al., Citation2018; Michele & Domenica, Citation2020). As mentioned, the important reasons for migrants are the elderly household head’s experiences, knowledge, information, physical capacity, skills and abilities increase at the older age of the household head.

According to the binary logistic regression results, all explanatory variables such as age, educational status, soil infertility, attitude of urban area, use of credit, access to information and off-farm activity are expected to have strong positive associations with rural-urban migration and mostly affect rural-urban migration. Keeping all other things constant, the marginal effect of the regression shows that all significant independent variables range from 7.43% to 35.72% on average in the study area. Moreover, all else being constant, the marginal effect of the 1% significant explanatory variables ranges from 22.54% to 35.72% higher probability of rural-urban migration, on average. Furthermore, educational status and access to information are expected to be 32.41% and 35.72% higher, respectively, than those of non-migrants. Education and information are key drivers of rural-urban migration in terms of migrants’ needs by solving food security problems. People with more information in a given season in an urban area are expected to have higher migration rates than their counterparts. Specifically, there is a positive correlation between the availability of information and rural-urban migration at a 1% probability significance level. This result is similar to that reported by Redehegn et al. (Citation2019). Soil infertility degradation, agricultural production and productivity loss are also considered problems in the study area in terms of reducing incomes at the household level in the study district. This result is in line with that of Gelb and Krishnan (Citation2018). Landholding was found to be negatively associated with rural-urban migration at the 5% probability significance level. An average landholding increase at the household level decreases the rural-urban migration status by 24.62%, all other things being constant. This binary logistic regression result is similar to those of (Dazhuan et al., Citation2020; Shaoyao et al., Citation2020). The regression results indicate that there is a positive significant relationship between soil infertility and migration status in the study district and variables significant at the 1% significance level. The binary regression model expected that household head soil infertility would increase by 1% on average, and members of households would migrate 31.27% more from rural to urban areas. Therefore, in the study area, migrants were more likely to be affected by soil infertility problems than non-migrants. Rural farm households suffering from soil infertility are unable to produce enough and adequate agricultural production, which is a key issue in ensuring food security and poverty alleviation. This result is in line with those of Michele and Domenica (Citation2020). The distance of household residence from the nearest town was an important determinant of rural-urban migration and was mostly found to have a significant negative association with rural-urban migration, while citrus paribus, a greater distance in kilometers between rural and urban areas decreased migrants by 23.76%. This result is similar to that of Eshetu and Beshir (Citation2017). Further, the attitude of urban areas is another significant explanatory variable at the 1% level, which is positively related to rural-urban migration. In addition, the regression results indicate that keeping all other variables constant, the marginal effect shows that the attitude of urban areas increases by 1% on average, with a higher probability of rural-urban migration in the study district. According to the binary logistic regression, all the remaining explanatory variables, such as sex, size of family and access to infrastructure did not have any significant relation to rural-urban migration in the study area.

4. Conclusion

Rural-urban migration is a central challenge in alleviating food insecurity and poverty in rural Ethiopia, particularly in the study district. In this study, low agricultural production and productivity were key drivers of rural-urban migration. The general objective of this study is to investigate the determinants of rural-urban migration in Duna district, southern Ethiopia. The primary and secondary data were used in this study. Cross-sectional survey data were collected from 187 sample households during the 2021/22 migration season. Both descriptive and binary logistic regressions were applied for the data analysis. The data analysis revealed that rural-urban migration was affected by age, educational status, landholding, credit use, soil infertility, access to information, off-farm activity, attitude of rural areas and distance nearest to town. This study found that rural-urban migration is a central problem in alleviating food insecurity and poverty in the study district.

This study has typical limitations such as the COVID-19 pandemic during data collection time, scope and depth as it only focused on rural-urban migration, and comparisons of the study result with the results of the same topic among different countries. Therefore, further research should consider expanding the scope, depth and comparison of the same topic among different countries.

Disclosure statement

We declare no competing interests.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Table 1. Sample of households based on the level of rural-urban migration status.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Negese Tamirat

Negese Tamirat is an assistant professor of Economics and senior researcher at Jimma University. His research interests include impact analysis, efficiency analysis, financial economics, international economics, poverty, migration, monetary and fiscal policy, macroeconomic and microeconomic policy analysis and adoption of farm inputs. He has published twenty-eight papers in pre-reviewed international journals. I am Negese Tamirat in the photograph.

Sanait Tadele

Sanait Tadele completed her education at the undergraduate level in management at Jimma University. Her research interests include human capital, performance evaluation, value chain and market analysis and management practices. She has published five papers in pre-reviewed international journals.

Workalemahu Assefa

Workalemahu Assefa is a full time lecturer at Hawassa College of Teacher Education, Psychology Department. His research interests include child development, migration and adolescent emotional adjustment. He has published one paper in pre-reviewed international journals.

References

- Abeje, A. (2006). Rural-urban migration to Bahir Dar Town: A case study on daily labourers [Master’s thesis]. Addis Ababa University.

- Abeje, A. (2021). Causes and effects of rural-urban migration in Ethiopia: A case study from Amhara Region. African Studies, 80(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2021.1904833

- Agza, M., Alamirew, B., & Shibru, A. (2021). Crop producers technical efficiency and its determinants in Gurage zone, Ethiopia: A comparative analysis using rural-urban migration as a parameter. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1995996

- Ahmed, N., & Ishrat, S. (2020). Push and pull factors of internal migration in Balochistan Province: A case study. Pakistan Journal of Applied Social Sciences, 11(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.46568/pjass.v11i1.435

- Amrevurayire, O., & Vincent, O. (2016). Consequences of rural-urban migration on the source region of Ughievwen clan delta state Nigeria. European Journal of Geography, 7(3), 42–57.

- Asfaw, W., Degefa, T., & Gete, Z. (2010). Causes and impacts of seasonal migration on rural livelihoods: Case studies from Amhara Region in Ethiopia. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 64(1), 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291950903557696

- Assefa, B., & Eshetu, M. (2017). Determinants of rural out-migration in Habru district of Northeast Ethiopia. Hindawi International Journal of Population Research, 2017, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4691723

- Atnafu, A., Linda, O., & Benjamin, Z. (2014). Poverty, youth and rural-urban migration in Ethiopia, Working Paper, University of Sussex.

- Baker, J. (2012). Migration and mobility in a rapidly changing small town in Northeastern Ethiopia. Environment and Urbanization, 24(1), 345–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247811435890

- Birhanu, A. M. (2011). Causes and consequences of rura-urban migration: The case of Woldiya Town [Master’s thesis]. University of South Africa.

- Birhanu, M., & Nachimuthu, K. (2017). A review on causes and consequences of rural-urban migration in Ethiopia. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 7, 37–42.

- Carson, S. (2019). Enabling successful migration for youth in addis ababa a policy paper for save the children Ethiopia [Master’s thesis]. The fletcher School Tufts University.

- CIA (Central Intelligence Agency). (2018). The work of a nation, Ethiopian economy profile. CIA World Fact Book, January 20, 2018.

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency). (2017). Agricultural sample survey 2016/201. 7 (2009 E.C). Report on area and production of major crops (private peasant holdings, Meher season) (Vol. I). CSA, Addis Ababa.

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency). (2018). Agricultural sample survey 2017/2018. Report on area and production of major crops (private peasant holdings, Meher season) (Vol. I). CSA, Addis Ababa.

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency). (2019). Agricultural sample survey 2018/. 2019 (2011 E.C). Report on area and production of major crops (private peasant holdings, Meher season (Vol. I). CSA, Addis Ababa.

- Dazhuan, G., Long, H., Qiao, W., Wang, Z., Sun, D., & Yang, R. (2020). Effects of rural–urban migration on agricultural transformation: A case of Yucheng City, China. Journal of Rural Studies Elsevier Ltd, 76, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.04.010

- Debelo, D. (2015). Does adoption of quncho tef increases farmers’ crops income? Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 6(17), 2222–2855.

- Ellis, F. (2003). A livelihood approach to migration and poverty reduction. DFID Paper, Overseas Development Group.

- Eshetu, F., & Beshir, M. (2017). Dynamics and determinants of rural-urban migration in Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural, 12(9), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2017.0850

- FAO. (2019). FAO migration framework – migration as a choice and an opportunity for rural development (Report). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Fasil, E., & Mohammed, B. (2017). Dynamics and determinants of rural-urban migration in. Department of Economics, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia.

- Fetagn, G. (2017). Economic efficiency of smallholder wheat producers in Damot Gale District, southern Ethiopia [Doctoral dissertation], Haramaya University.

- Francesco, C. (2018). Drivers of migration: Why do people move? Journal of Travel Medicine, 25(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tay040

- Gelb, S., & Krishnan, A. (2018). Technology, migration and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SDC (Report). ODI.

- Gujarati, N. (2004). Basic econometrics (4th ed.), The McGraw-Hill Companies.

- Hashim, I., & Thorsen, D. (2011). Child migration in Africa. ZED Books.

- Herrera, C., & Sahn, D. (2013). Determinants of internal migration among Senegalese youth. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2229584

- Hussain, A. (2016). Urban sprawl, infrastructure deficiency, and economic inequalities in Karachi. Science International, 28(2), 1689–1696.

- Ishtianque, A., & Ullah, M. S. (2013). The influence of factors of migration on the migration status of rural-urban migrants in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Human Geographies, 7(2), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.5719/hgeo.2013.72.45

- Kangmennaang, J., Bezner-Kerr, R., & Lu, I. (2018). Impact of migration and remittances on household welfare among rural households in Northern and Central Malawi. Migration and Development, 7(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2017.1325551

- Khan, A. A., Arshad, S., & Mohsin, M. (2014). Population growth and its impact on urban expansion: A case study of Bahawalpur, Pakistan. Universal Journal of Geoscience, 2(8), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujg.2014.020801

- Kothari, U. (2002). Migration and chronic poverty. University of Manchester Working Paper No16, Chronic Poverty Research Centre.

- Latif, A., & Yu, T. F. (2020). Resilient urbanization in Pakistan: A systematic review on urban discourse in Pakistan. Urban Science, 4(76), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci4040076

- Laura, D., & Elisenda, E. (2016). Addressing rural youth migration at its root causes: A conceptual framework (Report). FAO.

- Malik, S., Roosli, R., & Tariq, F. (2020). Investigation of informal housing challenges and experience from slums and squatters of Lahore. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 35, 143–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-019-09669-9

- Markos, E., & Gebre-Egziabher, K. (2001). Rural out-migration in the drought-prone areas of Ethiopia: A multi-level analysis. International Migration Research, 35, 749–771.

- Michele, N., & Domenica, F. (2020). Migration, agriculture and rural development: IMISCOE research series [book]. Springer.

- Naghmana, G., Sana, F., Mehr-Un- Nisa, R., & Akbar, M. (2021). An empirical investigation of socio-economic impacts of agglomeration economies in major cities of Punjab, Pakistan. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1975915. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021

- Negese, T. M., &Sanait, T. H. (2023). Determinants of technical efficiency of coffee production in Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon, 9(4), e15030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15030

- Negese, T., &Jemal, A. (2021). Adoption of row planting technology and household welfare in southern Ethiopia, in case of wheat grower farmers in Duna district, Ethiopia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Science and Technology, 26(2).

- Niels, H., Blunch, C., & Rugeri, L. (2015). International migration, education and wages in Ethiopia. Discussion Paper Series,DP No 8926, IZA.

- Obijekwu, M. I., Muomah, R. I., & Enemuo, J. C. (2019). Migration and search for economic well-being: the dynamics of development in the third world. Journal of African Studies and Sustainable Development, 2, 2630–7073.

- Rana, I. A., & Bhatti, S. S. (2018). Lahore, Pakistan-urbanization challenges and opportunities. Cities, 72, 348–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities

- Redehegn, M. A., Sun, D., Eshete, A. M., & Gichuki, C. N. (2019). Development impacts of migration and remittances on migrant-sending communities: Evidence from Ethiopia. PLoS One, 14(2), e0210034. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210034

- Shaoyao, Z., Deng, W., Peng, L., Zhou, P., & Liu, Y. (2020). Has rural migration weakened agricultural cultivation? Evidence from the mountains of Southwest China. Journal of Agriculture, 10(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10030063

- Skeldon, R. (2002). Migration and poverty. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 17(4), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.18356/7c0e3452-en

- Wooldridge, J. (2013). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. OH South-Western Cengage Learning.

- World Bank. (2010). The Ethiopian urban migration study: The characteristics, motives, and outcomes of migrants to addis ababa (Report No 55731-ET). World Bank.

- Yamane, T. (1973). Statistics: an introductory analysis (3rd ed.). Happer & Row publisher.

- Zerga, B., Warkineh, B., Teketay, D., Woldetsadik, M., & Sahle, M. (2021). Land use and land cover changes are driven by the expansion of eucalypt plantations in the Western Gurage Watersheds, Centeral-south Ethiopia. Trees, Forests and People Elsevier, 5, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2021.100087