?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper examines formal sector employees’ choices of urban agriculture (UA) practices and their implications for sustainable food supply in sub-Saharan Africa’s urban landscape with specific reference to urban Wa, Ghana. A cross-sectional survey research design was adopted with questionnaires as the main data collection instrument. A total of 364 formal sector employees were randomly selected from four public sector institutions in urban Wa. The multinomial logit regression was employed to analyse the factors determining formal sector employees’ choices of urban agriculture practices. The findings show that only 37.9% of formal sector employees contacted participate in UA in the form of food crops and/or animal production. Employees within the Teacher and Education Directorate engage more in UA than those from other sectors. The likelihood of a formal sector employee choosing food crop production and/or animal production is influenced by household size, household income, average household expenditure and farm income. The findings underscore the need for policy attention on formal sector employees’ increased participation in UA as it contributes significantly to food supply and improved wellbeing of households. The study recommends that the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) should encourage and support formal sector employees to embrace at least one, but preferably both, of Ghana’s current agricultural sector policies: Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ), Rearing for Food and Jobs (RFJ) and Planting for Export and Rural Development (PERD) for increased and sustained food production in Ghana’s urban communities. The study broadly contributes to the attainment of Sustainable Development Goal 2—Zero Hunger in developing countries.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Worldwide, between 100 and 200 million urban farmers supply the urban markets with fresh agricultural products (Orsini et al., Citation2013). Urban agriculture (UA) deals with cultivating crops and/or rearing livestock within the urban and peri-urban landscape (Nicholls et al., Citation2020; Omondi et al., Citation2017; Orsini et al., Citation2013; van Veenhuizen, Citation2006; Xie et al., Citation2020). Urban agriculture is projected to positively transform living standards in urban centres since about 85% of the entire household incomes is spent on food (Orsini et al., Citation2013). Urban agriculture is critical because of the pivotal role it plays in social inclusion, specifically bridging the gender inequality gap (Orsini et al., Citation2013; Sanyé-Mengual et al., Citation2018). Importantly, about 65% of the global urban farmers are women (Orsini et al., Citation2013), suggesting that urban agriculture presents a livelihood option for the marginalised in society. Urban agriculture also contributes to enhancing global ecosystems (urban waste reduction, biodiversity conservation, air purification and water storage systems) in cities (Omondi et al., Citation2017; Sanyé-Mengual et al., Citation2018; Xie et al., Citation2020).

The United Nations (Citation2017) projected that the global population would increase from 7.5 billion in 2017 to 9.8 billion by 2050. It further revealed that countries in southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are likely to record much of the global population increase with implications on food security. Nevertheless, the World Bank (Citation2018) reported a decline in agricultural output of 0.8% in Ghana within the past two decades and associated decline in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 29.8% to 18.9% in 2010. These statistics have dire consequences for urban centres in Ghana where the majority of the youthful population prefer to live in the cities (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020). The increasing population in urban centres is characterised by preferences and changes in consumption patterns–increasing demand for fresh agricultural products such as fruits and vegetable, milk, egg, fish and meat (Cofie et al., Citation2003; Orsini et al., Citation2013). Many of these products are supplied by rural farmers supplemented by imports from other countries. Consequently, the production of some of these products in urban areas may help to meet the urban food demand by providing fresh vegetables to the urban dwellers. The position of UA in meeting the food needs of the growing urban population in developing countries is unclear, with some scholars arguing that UA is left in the hands of the poor, the unemployed and people with limited investment capital at the expense of those employed and – creditworthy (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020; Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019) often leading to limited urban agricultural production (Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019).

International and national policy platforms across countries have emphasised the need to support UA as a channel for promoting food security among urban households (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020; Nicholls et al., Citation2020; Olumba & Onunka, Citation2020; Omondi et al., Citation2017). For example, in Ghana, the Medium-Term Agricultural Sector Investment Plan (METASIP I) (2011–2015) had among its six main components, one component specifically targeting ‘support to urban and peri-urban agriculture’ (MoFA, Citation2010), highlighting the role of urban agriculture in supplying the food needs of Ghana’s increasing population in the cities. Thus, METASIP I could serve as a springboard for urban dwellers to fully embrace urban agriculture. However, it has failed to clearly differentiate the relationship between urban agricultural practitioners and their counterparts in rural areas with respect to the contribution towards addressing urban households’ food insecurity (Ayerakwa, Citation2017). Ayerakwa et al. (Citation2020) argued that urban agriculture has not been elevated within Ghana’s agricultural policy. The authors based their argument on the fact that the revised METASIP II (2014–2017) policy document only highlighted urban agriculture once in a paragraph concerning food safety but with little interest in supporting urban agricultural growth.

Consequently, in order to reverse the continuous decline in Ghana’s agricultural productivity, the government rolled out many policies to improve food production across the length and breadth of the country. Notable among them are the Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ), Rearing for Food and Jobs (RFJ) and Planting for Export and Rural Development (PERD). In addition, the ‘One village, One dam’ programme, which seeks to promote all year round cropping among smallholder farmers in water stressed areas was formulated (MoFA, Citation2017). The PFJ policy specifically focused on scaling up home-grown food production thereby enhancing food security, and scaling down the country’s food import bill (MoFA, Citation2017; Tanko et al., Citation2019). The target crops under the PFJ programme include sorghum, maize, rice, soybeans and vegetables such as pepper, onion and tomato (Tanko et al., Citation2019). These crops constitute the main food consumed by the urban dwellers in Ghana. Besides, these crops fall squarely under the Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy (FASDEP II) target, supported by the METASIP I and II (Tanko et al., Citation2019). Unfortunately, the contradiction here is that the government’s policy directions in the agriculture sector are largely focused on supporting rural farmers with little attention on urban agriculture, although a large body of the abled-labour force that could contribute to the national food basket lives in the urban centres of Ghana (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020).

Recent studies have looked at the contribution of UA to addressing food insecurity in the developing world (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020; Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019; Olumba & Onunka, Citation2020; Omondi et al., Citation2017). In the specific study of Ayerakwa et al. (Citation2020), the focus was on the association between urban dwellers’ participation in UA and their households’ food security status. These authors found that urban dwellers who practice any form of agriculture – urban or rural agriculture - were food secured in medium-sized cities. Bolang and Osumanu (Citation2019) similarly assessed formal sector employees’ participation in UA and found that about 62.1% of formal sector employees in the Wa Municipality were not engaged in any form of UA. A formal sector worker or employee is someone who is employed in a formalized governmental, non-governmental or a private firm (Wamuthenya, Citation2010).

In this study, the formal sector employees who participated in the survey were drawn from the public sector. According to Bolang and Osumanu (Citation2019), the likelihood of a formal sector employee participating in UA is influenced by his or her personal characteristics such as age, sex, educational status, income, household size and workload. However, urban dwellers participate in UA either as food crop producers or livestock farmers, or a combination of both. While this may have implications on Ghana’s agricultural policies, the factors that determine formal sector workers’ choice of UA practices has received limited scholarship. It is against this background that this study seeks to fill the literature gap by examining the factors that influence formal sector employees’ choice of UA practices in Wa Municipality.

Indeed, urbanisation took several decades to gain attention in the policy discourse of Ghana. It was not until the 2010 population and housing census that it became apparent that about 51% of Ghana’s population live in urban centres (Ghana Statistical Service [GSS], Citation2012). Although the Wa Municipality was not listed among the most urbanised cities in Ghana, the literature has indicated that Wa has transitioned over time to become the major urbanised city in north-western Ghana (Ahmed et al., Citation2020; Osumanu et al., Citation2018). Our study is significant in contributing to the literature on addressing urban households’ food needs in developing countries (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020; Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019; Lal, Citation2020; Olumba & Onunka, Citation2020; Omondi et al., Citation2017; Sanyé-Mengual et al., Citation2018; Siegner et al., Citation2018) through increased participation of formal sector employees in agricultural production. On this note, the paper posited that attaining food security, which is fundamentally explained as a situation ‘when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’ (FAO, Citation2008), demands that governments, Non-Governmental Organisations, Civil Society Organisations, and academics focus on encouraging the majority of the populace (including urban dwellers) to participate in agricultural production. Furthermore, we argue that meeting the United Nations SDG 1 (Target 1.1 – eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere) and SDG 2 (Target 1 – end hunger and ensure assess by all people) by 2030 (UN, Citation2019) stands to be adversely affected if urban areas that host a massive labour force are not brought into the food production trajectory.

The study sourced data from 364 formal sector employees across four sectors (Wa Municipal Assembly, Teachers and Education Directorate, Municipal Agricultural Directorate (MAD) and Regional Coordination Council) through a questionnaire survey for a nuanced understanding of the factors that influence their choice of urban agriculture practices. The paper is organised into six major sections. After the introduction section, the next section (section two) presents the conceptual framework, followed by the materials and methods in the third section; the fourth section presents the results, whereas the fifth section presents the discussion. The sixth section presents the conclusion and policy implications.

2. Conceptual framework

Empirical studies (e.g. Nkegbe et al., Citation2017) have noted that northern Ghana suffers more from food insecurity than other parts of the country. In tackling the phenomenon of food insecurity, a study by Nkegbe (Citation2012) indicated that access to land in northern Ghana is not problematic but the small capital base of smallholder farmers limits their production efforts. It has been noted that smallholder farmers’ efforts to scale up food production are largely hindered by limited capital and the lack of credit supporting institutions (Ansah et al., Citation2016). Besides the lack of credit, the challenge of access to urban and peri-urban agricultural land for agricultural production is also a hindrance (Abdulai et al., Citation2022). Studies have pointed out that women are largely marginalised in accessing land for agricultural purposes in both the rural and urban agricultural landscapes (Azumah et al., Citation2022). A related study conducted by Okello et al. (Citation2017) in Kenya acknowledged the effect of limited access to credit as a major drawback to smallholder food crop farmers’ productivity. The farmers suggested the use of improved and certified seeds as a means to increase productivity and thereby enhance food security in food insecure areas. The adoption of leguminous cover crop and high yield varieties are other policy options suggested toward enhancing food security in developing countries (Raizada & Small, Citation2017). Moreover, some scholars are of the view that the surest ways to increase food production and to feed the growing population, particularly amongst urban areas across SSA, is to encourage the formal and informal working class to contribute their quota to food production including food markets (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020; Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019; Orsini et al., Citation2013). Earlier, Orsini et al. (Citation2013) emphasised supporting and encouraging the participation of the youth and women in UA production to address urban food insecurity in developing countries.

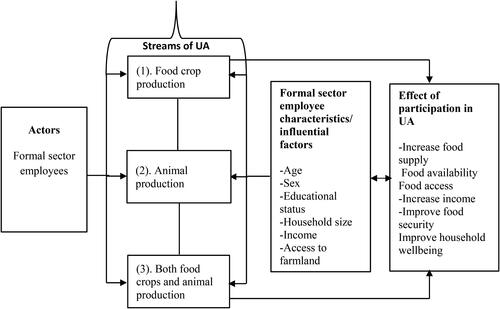

While the aforesaid scholarly contributions to attaining food security in underprivileged societies are important, how to get formal sector employees involved in agriculture production, the type of agriculture they are engaged in, and the determinants of their choice of UA practices, remain opaque in the extant literature. In the literature, it has been established that people who are creditworthy participate less in agricultural production in developing countries. They are also less motivated to invest in agriculture and associated sectors (Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019). On this premise, production levels in agriculture remain subsistent, thwarting efforts to bridge the food insecurity gap in the developing world. outlines the relationship between formal sector employees’ characteristics and choice of UA practices towards meeting the food needs of their households. Indeed, food insecurity in urban areas in the Global South remains a topical issue in the policy discourse (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020). This study, therefore, argues that formal sector employees’ engagement in any form of UA agricultural activity (food crop production and/or animal rearing) inures to the benefit of urban households to increase food supply, food availability, food accessibility, and incomes, and to improve food security and the wellbeing of the entire household (). However, to take steps towards getting formal sector employees to increase participation in agricultural production, answers to the following research questions are indispensable in guiding policy and major decision-making bodies on urban food supply: (1) to what extent do formal sector employees participate in urban agriculture? (2) What factors influence formal sector employees’ choice of urban agricultural practices? (3) What are the constraints to formal sector employees’ participation in urban agriculture?

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study area

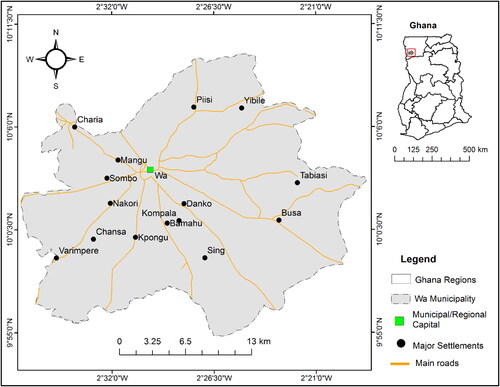

The study was conducted in the Wa Municipality (). The Wa Municipality is one of the 11 District/Municipal Assemblies that make up the Upper West Region (UWR) of Ghana. The Wa Municipality shares administrative boundaries with Nadowli District to the North, Wa East District to the East and South and the Wa West District to the West and South. It lies within latitudes 1°40’N–2°45’N and longitudes 9°32’–10°20’W (GSS, Citation2013). The Wa Municipality has its capital as Wa, which also serves as the regional capital of the Upper West Region. It has a landmass of approximately 234.74 square kilometres, which is about 6.4% of the region (GSS, Citation2014). Of the 11 MMDAS in the Upper West Region, the Wa Municipality recorded the highest population in the Upper West Region of 107,214 persons, constituting 15.3% of the total population in the region (GSS, Citation2013).

Figure 2. Map of Wa Municipality. Source: Adapted from Ghana Statistical Service (Citation2014).

The population is youthful and economically active. Demand for fresh agricultural products such as vegetables is on the increase in the Municipality. The economy of the Municipality, previously dominated by the agriculture sector, has witnessed a paradigm shift from the hitherto agrarian economy to a services, market and commence driven economy. As it stands, the services sector employs about 51.3% of the working population, followed by agriculture 30.2% and industry 18.4%. This indicates that the majority of the dwellers are outside agriculture, hence urban UA is an object of interest (GSS, Citation2012). Other key sectors of the economy are transport, tourism, communication, and energy. Under the agricultural sector, most of the farmers are engaged in peasant farming and the main staple crops grown include millet, sorghum, maize, rice, cowpea, and groundnut cultivated on a subsistence basis. Others include soya beans, groundnuts, and bambara beans largely cultivated as cash crops. However, the majority of the farming is done outside the urban frontier with the peri-urban communities and rural areas largely depended on for the food needs of the urban populace. Thus, increased participation of formal sector employees in urban agriculture in the Wa Municipality may supplement the food supplies from the peri-urban and rural areas.

3.2. Study design and data collection

The study was a cross-sectional survey that employed mixed methods and multiple sampling techniques in selecting the study respondents across four (4) formal sector institutions – the Wa Municipal Assembly, Teachers and Education Directorate, Municipal Agricultural Directorate (MAD) and the Regional Coordination Council (RCC). These categories of formal sector employees were chosen to participate in the study because they are classified as non-essential service providers and so do not respond to emergencies or time demands. Also, these employees are the majority in Wa Municipality and are perceived to be creditworthy (Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019). They could access capital from both formal and informal sources for agricultural production. In all, 3,980 staff were selected from the aforementioned formal sector institutions constituting the sampling frame of the study (). The selection of the study participants was done devoid of gender bias – both males and female formal sector employees were involved in the survey. Based on the sampling frame of 3,980, the study sample size was calculated following Yamane (Citation1967:688) as follows:

(1)

(1)

where, n = Sample size; N = Sampling frame, e = error.

(2)

(2)

Table 1. Proportionate distribution of respondents.

Furthermore, the sample size (n = 364) was proportionally distributed among the selected categories of formal sector employees (). We ensured that the study participants fully consented to participate in the study by assuring them of the confidentiality of the data elicited from them and that the information they give will be sued only for the purpose of this study. Thus, all ethical standards in connection with the study data collection were duly observed and the respondents consented verbally to participate as well as give further information in support of the survey. The questionnaire was designed to capture issues relating to the respondents level of participation in urban agriculture, the type of agriculture they practice in the form of food crop farming and/or animal rearing, and the challenges they face in participation in UA. The questionnaire also captured their socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and formal educational qualification.

3.2.1. Data analysis

The data analysis involved coding and entering the data into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) (version 21). Descriptive statistics involving cross tabulations were used to analyse respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics and their implications on formal sector employees’ participation in UA. The challenges facing formal sector employees’ participation in UA were analysed using Kendall’s W concordance test. Further, the factors that explain formal sector employee’s choice of UA activity were analysed using a regression model. The various categories of agricultural activities include food crop production and animal rearing.

3.3. Analytical framework

The study sought to identify the factors influencing formal sector employees’ choice of agriculture activities and contribution to their household livelihoods. The various categories of agricultural activities include food crop production and animals rearing. Therefore, we employed the multinomial logit model to analyse the formal sector employees’ choice of urban agricultural practices. Multinomial logit (mlogit) is ideal for predicting single categorical variables and determining the numerical relationship between sets of variables. Because the dependent variable (participation in UA) is categorical (), the multinomial logit is appropriate for this analysis. In the application of the multinomial logit model, key challenges including outlier effects and multicollinearity were addressed. The multinomial logit model adopted in this study follows that of Green (Citation2005) and is specified as follows: An ith individual will participate in a jth category of agricultural activity that yields maximum utility. The probability of participating in a jth category is estimated using the multinomial logit. Following from Green (Citation2005), the conditional probability of the multinomial logit is specified as:

(3)

(3)

Table 2. Definition and measurement of variables.

The empirical specification of the multinomial logit model for the choice of participating in agriculture is specified as:

(4)

(4)

The variables definition and measurement are shown in .

Furthermore, we employed the Kendall’s coefficient of concordance test to analyse the constraints faced by formal sector employees in participating in UA. Here, we analysed the respondents’ level of agreement on the most persistent constraints they faced in participating in UA. Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W) is a measure of the agreement among several (−) judges who are assessing a given set of n objects (constraints) (Legendre, Citation2005). W is an index that measures the ratio of the observed variance of the sum of ranks to the maximum possible variance of the ranks. The idea behind this index is to find the sum of the ranks for each constraint being ranked. If the rankings are in perfect agreement, the variability among these sums will be maximized (Mattson, Citation1986). The Kendall’s concordance coefficient (W) is therefore given by the relation:

(5)

(5)

Where W denotes the Kendall’s Concordance Coefficient, P denotes the number of constraints, n denotes the number of respondents (sample size), T denotes the correlation factor for tied ranks and S denotes the sum of square statistic. The value of W lies between 0 and 1, where 1 indicates perfect concordance or agreement and 0 indicates perfect disagreement among the rankers of the rankings. The sum of a square statistic (S) is given as:

(6)

(6)

where Ri = row sum of ranks, R = the mean of Ri

The correlation factor for tied ranks (T) is given as:

(7)

(7)

where tk = the number of ranks in each (k) of m groups of ties.

The test of significance of the Kendall’s concordance was done using the chi-square (X2) statistic, which is computed using the formula;

(8)

(8)

where n = sample size, p = number of constraints, W = Kendall’s coefficient of concordance.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

The survey results () show that the majority (56.9%) of the formal sector employees in the Wa Municipality were within the youthful age cohort of 31–40 years whereas the smallest age group was 61 years and above. However, males dominated the survey making up 70.3% of the participants. Additionally, the results show that the majority (92.3%) of the survey participants had tertiary education qualifications, 73.4% were married, 52.2% were Muslims and 47.8% were Christian. For household size, 50.8% of the respondents had household sizes of 6–10 members.

Table 3. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents (N = 364).

4.2. Formal sector employees’ participation urban agriculture (UA) practices

Results from the survey () show that the majority (62.1%) of the study respondents have not participated in any form of UA. Of the 37.9% who participated in UA, males dominated (44.1%) as against their female counterparts (23.1%). The respondents’ choice of UA practice revealed more males practice food crop farming (78.9%), animal farming (81.8%) and a combination of both food crop and animal farming. Furthermore, the survey results revealed that the majority (83.3%) of the respondents who practice UA are teachers and education workers (Teachers/Education Directorate).

Table 4. Relationship of socio-demographic variables with respondents’ choice of UA practice.

4.3. Determinants of formal sector employees’ choice of UA practices

Formal sector employees who engage in UA produce either food crops, animals, or both. The multinomial logistic regression was used to determine the factors influencing participation in crop or animal production. Participation in crop and animal production was regressed on different explanatory variables. The variables include marital status, ease of getting land, youth, credit, household income, formal workload, age, household size, average expenditure on farming, and farm income ().

Table 5. Multinomial Logit estimates of formal sector employees’ choice of urban agricultural production.

The Likelihood Ratio (LR) statistics (115.82) were significant at 1% (). Three out of the ten independent variables were found to have a significant influence on participation in crop production, and another three out of ten were significant for animal production. The base category in the multinomial logit model was a category of respondents who produce both crops and animals. The results further indicate that household income has a significant influence on participation in crop production. From the results (), the coefficient of household income is negative and significant at 10%. This means that people with high incomes are less likely to participate in only crop production than in both crops and animals. The marginal effect of 0.0002 means that an increase in income by GH¢1.0 will attract a 0.02% probability of engaging in both crops and animal production. Several justifications could account for this finding. First, people may want to diversify their income by engaging in both crops and animal production. The risk associated with crop production, particularly climate factors in the study area, such as low rainfall, floods, drought and prevalence of pests and diseases, may be a reason for diversification.

It was also discovered that household size has a significant influence on formal sector employees’ participation in agriculture. The multinomial logistic regression estimates () revealed that the coefficient of household size was positive and significant at 1% for the category of animal production. What this implies is that households with more members are more likely to participate in animal production alone than in both crop and animal production. The marginal effect of 0.0035 implies that an additional member of a household will increase the likelihood of participating in animal production by 0.05%. In recent times, people, especially those in the formal sector, have discovered the relative convenience of keeping farm animals, even at home. Such people can take advantage of excess labour at homes (households) such as children and the aged who can easily feed the animals. However, such labour may not be able to work on crop fields because of the tedious activities involved. This probably is the justification for larger households participating in animal production. Besides, in the Wa Municipality, people keep their farm animals at home either under intensive or semi-intensive systems. As a result, they can effectively combine animal rearing with their formal sector work. However, except for backyard gardens, crop production is often done far away from the farmers’ residences; thus, making it difficult for the farmer to combine both crop production and the formal work commitment.

The survey identified average expenditure on production as a significant determinant for participation in crop production on one hand and animal production on the other. From , the coefficient of average expenditure is positive for crop production but negative for animal production and all were found to be significant at 1%. This means that an increase in average expenditure of production will increase the likelihood of participating in crop production; but on the other hand, it will have a corresponding decrease in the likelihood of participating in animal production. This means that higher expenditure on production will encourage formal sector employees’ participation in crop production, but discourage the production of animals. As expenditure on crop production increases, the more the farmer is shifting towards commercialization. It could be that such people have obtained the benefits of investment; hence their desire to participate in crop production. On the other hand, people may be keeping the animals just as a hobby and do not invest much in their activities. This explains why an increase in expenditure decreases the likelihood of participating in animal production. Additionally, farm income was observed to have a similar influence as farm expenditure. It was discovered that farm income has a negative and significant influence on crop production but a positive and significant influence on animal production at 1% in either case (see ). This suggests that people with greater earnings are more likely to engage in animal production than producing both crop and animals. On the other hand, an increase in farm income will reduce the probability of engaging in both crop and animal production more than in producing only crops.

4.4. Constraints to formal sector employees’ participation in urban agriculture

Formal sector employees who engaged in urban agriculture face challenges like full time urban farmers. Kendall’s W value of 0.679 was significant at 1% and suggests that there is 67.9% agreement among the respondents on the ranking of the challenges confronting them in their UA production process. The major challenges include poor rainfall, pests and diseases, and poor soils ().

Table 6. Descriptive statistics and Kendall’s W on challenges formal sector employees face in participating in UA.

The results suggest that despite the efforts by formal sector employees to participate and contribute to urban food security, their efforts have been challenged by several factors. The challenges differ from one another in terms of intensity as reported by Kendall’s coefficient of concordance test. The findings show that the dominant challenges faced by urban farmers as ranked by the respondents include the effects of pests and diseases, poor soil fertility and limited access to fertilizer. This means that for all the farmers, these are key challenges since they appear as most pressing in their ranking. Hence, the efforts of formal sector employees in contributing to urban food security may not yield the maximum results given the current constraints they faced in participating in UA.

5. Discussion

Urban agriculture holds great potential for urban dwellers to contribute to food production and bridge the food insecurity gap in developing countries (Ayerakwa, Citation2017; Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020; Cofie et al., Citation2003; Orsini et al., Citation2013). It is therefore incumbent upon urban dwellers to buy into the idea of increasingly participating in UA production to feed the ever-increasing urban population. Therefore, the working class who are deemed to be creditworthy (Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019) are expected to embrace UA by investing and participating in it. Unfortunately, findings from our study showed that formal sector employees’ participation in urban agriculture is very low (37.9%). This comes as no surprise because extended studies have pointed out the low participation of formal sector employees in agricultural production (Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019; GSS, Citation2014). The GSS (Citation2014) reported that about 71.1% of the agricultural labour force in the Wa Municipality is provided by rural dwellers. On this premise, it can be argued that agriculture is left in the hands of the peri-urban and rural smallholder farmers whose production is largely on a subsistence basis. However, the findings from this study bring to the fore the fact that more men are likely to participate in UA than their female counterparts. This contradicts the findings of Orsini et al. (Citation2013) who posited that females constitute the majority (65%) in terms of participation in UA production. The issue of males dominating the UA landscape in this study may be attributed to the constraints females face in accessing land for agricultural purposes in northern Ghana. The customary land tenure regime of northern Ghana limit women opportunities and access to land and limits their engagement in agriculture in general and urban agriculture in particular (Azumah et al., Citation2022).

Formal sector employees in the Teaching and Education sector participate more in UA than the remaining three sectors surveyed. This may be explained by the fact that teachers have extra working hours out of school, which can be spent on other livelihood activities from which UA is not precluded. However, formal sector employees need to be motivated and encouraged to participate more in agricultural production. To better understand the factors that explain formal sector employees’ participation and choice of UA practices, we set out to examine a plethora of factors including the formal sector employees’ marital status, easy access to farmland, access and availability to credit, household income, formal sector workload, age, household size, average expenditure on farming, and farm income by employing the multinomial logistic regression analytical framework. The results suggested that the variables jointly explain formal sector employees’ choice of UA practice in the form of food crop production and/or animal rearing by a Likelihood Ration (LR) of 115.82, significant at 1%. Formal sector employees are engaged in both food crop and animal production; however, the majority are engaged in food crop farming, which is a major household requirement. Access to food at the household level is a significant means of improving households’ wellbeing (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020; Nicholls et al., Citation2020; Olumba & Onunka, Citation2020; Omondi et al., Citation2017).

In urban Wa, food crops such as grains (e.g., maize, rice, yam, cassava) and vegetables (tomatoes, pepper, pumpkin leaves lettuce, cabbage, okra, etc.) are cultivated by urban farmers and constitute the daily meals of the urban dwellers. Participation in UA agriculture by formal sector employees will come as a boost to bridging the food insecurity gap, and the combination of both food crop and animal production should be encouraged since animal production is a significant means of balancing the household diet and a means to increasing household income (Abdulai, Citation2022). Droppings (excreta) from the animals (cattle, goat, sheep, and poultry) reared within the urban and peri-urban frontiers can be used as manure to improve soil fertility and increased crop yield. However, food crop production is faced with unfavourable climatic conditions such as low rainfall, drought and the prevalence of pests and diseases, making it prudent for urban farmers to complement food crop production with animal rearing.

Findings from our study also suggest that households with more members are more likely to participate in animal production than a combination of food crop and animal production. However, the combination of both food crop and animal production goes a long way to support formal sector employees to feed their households. Thus, formal sector employees with large household sizes are encouraged to increase participation in both food crop and animal production. This is because a large household size may offer supporting labour to formal sector employees to participate in agricultural production with ease. Thus, average expenditure on agriculture production may be reduced if more family labour is committed to agricultural production. Importantly, formal sector employees in urban areas are knowledgeable about the prospects of producing their own food but may be constrained by time and other factors to engage in any form of urban agriculture.

Multiple factors affect formal sector employees’ participation in any form of agricultural production. Prominent among them are poor rainfall, outbreak of pests and diseases and poor soil fertility. These are factors that have been highlighted in the extant literature as drawbacks to agricultural production (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020). The findings from the survey show that limited access to farm credit largely reported by extant literature (Nkegbe et al., Citation2017) as a drawback to agricultural production in northern Ghana has limited effect on formal sector employees’ participation in UA. This buttresses the literature that posits that formal sector employees have no major problem with regards to raising capital to engage in agriculture production (Bolang & Osumanu, Citation2019). This suggests that policy options to increase formal sector employees’ participation in agricultural production should be focused on addressing issues relating to climate variability and improving access to agricultural land and spaces within the urban frontier (Ayerakwa et al., Citation2020). However, the availability of open spaces in the urban and adjoining sub-urban communities of the Wa Municipality that can be used for agriculture activities has been highlighted (Osumanu et al., Citation2018). In addition, increased participation of formal sector employees in agricultural production is possible because Wa is still a growing city with several patches of unbuilt land (Ahmed et al., Citation2020; Osumanu et al., Citation2018).

6. Conclusion and policy implications

The paper examines formal sector employees’ choices of urban agriculture (UA) practices and their implications for sustainable food supply in sub-Saharan Africa’s urban landscape with specific reference to urban Wa, Ghana. The findings show that a large proportion of formal sector employees do not engage in any form of UA activity. Formal sector employees who participate in UA contribute in different ways to ensure food security in the Wa Municipality. Their activities are limited to small-scale food crops and animal production. Thus, formal sector employees chose to engage in only food crop production, animal production and or both. Employees within the category of teachers/educational directorate participate more in UA than in the other categories. Several socio-demographic factors (household income, average household expenditure and farm income and household size, average household expenditure, and farm income) were found to influence formal sector employees’ choice of UA in the form of crop production and animal production, respectively. The finding underscores the need to adopt different approaches in appraising formal sector employees’ choice and participation in UA.

Nonetheless, there exist some consistencies in the factors explaining the choice of agricultural production. For example, those with large household sizes are likely to participate in animal production, probably because of the availability of excess labour. Besides, the cost and benefits of production; measured by average expenditures and farm income, respectively, influence agriculture production, suggesting that farm economics play a significant role in farm management decision-making. Thus, as the farmer experiences increases in expenditures, he moves away from crop production to animal production. Besides, increases in farm income attract investment in animal production. Moreover, the multitude of constraints encountered by formal sector employees in this study may be responsible for most of them not participating in UA. On the premises of these findings, the study recommends that policy options should be skewed toward educating formal sector workers on the prospects of UA in providing the food needs of urban areas in Ghana and other developing countries. Furthermore, Ghana’s agriculture policies such as the Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ), Rearing for Food and Jobs (RFJ) and Planting for Export and Rural Development (PERD) under MoFA should support and encourage formal sector employees to embrace UA towards meeting their food supply and eliminating hunger as envisioned by the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG2).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Peter Dery Bolang

Peter Dery Bolang holds a Ph.D. in Social Administration. His research interest centres on urban agriculture, urban sustainability, climate change and sustainable livelihoods. He has published in high-impact journals.

Issah Baddianaah

Issah Baddianaah holds a Ph.D. in Environmental Management and Sustainability. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, College of Arts and Sciences, William V.S. Tubman University, Liberia. He has several publications in the areas of environmental sciences and geography.

Issaka Kanton Osumanu

Issaka Kanton Osumanu is a professor of Geography. He specializes in geography. He has published in top-tier journals such as Land Use Policy, Urban Forum, and Habitat International among others.

References

- Abdulai, I. A. (2022). Rearing livestock on the edge of secondary cities: examining small ruminant production on the fringes of Wa, Ghana. Heliyon, 8(4), 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09347

- Abdulai, I. A., Ahmed, A., & Kuusaana, E. D. (2022). Secondary cities under siege: examining peri-urbanisation and farmer households’ livelihood diversification practices in Ghana. Heliyon, 8(9), e10540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10540

- Ahmed, A., Korah, P. I., Dongzagla, A., Nunbogu, A. M., Niminga-Beka, R., Kuusaana, E. D., & Abubakari, Z. (2020). City Profile: Wa, Ghana. Cities, 97, 102524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102524

- Ansah, I. G. K., Toatoba, J., & Donkoh, S. A. (2016). The effect of credit constraints on crop yield: Evidence from soybean farmers in Northern Region of Ghana. Ghana Journal of Science. Technology and Development, 4(1), 51–14. https://doi.org/10.47881/78.967x

- Ayerakwa, H. M. (2017). Urban households’ engagement in agriculture: Implications for household food security in Ghana’s medium-sized cities. Geographical Research, 55(2), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12205

- Ayerakwa, H. M., Dzanku, F. M., & Sarpong, D. B. (2020). The geography of agriculture participation and food security in a small and a medium-sized city in Ghana. Agricultural and Food Economics, 8(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-020-00155-3

- Azumah, F. D., Onzaberigu, N. J., & Adongo, A. A. (2022). Gender, agriculture and sustainable livelihood among rural farmers in northern Ghana. Economic Change and Restructuring, 56(5), 3257–3279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-022-09399-z

- Bolang, D. P., & Osumanu, I. K. (2019). Formal sector workers’ participation in urban agriculture in Ghana: perspectives from the Wa Municipality. Heliyon, 5(8), e02230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02230

- Cofie, O. O., van Veenhuizen, R., & Drechse, P. (2003). Contribution of urban and peri-urban agriculture to food security in sub-Saharan Africa [Paper presentation]. Paper Presented at Africa Session of WWF, Kenya, 17th March 2003.

- FAO. (2008). An introduction to the basic concepts of food security. FAO.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). 2010 Population and housing census: district analytical report: Wa Municipality. GSS.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2012). 2010 Population and housing census analysis of district data and implications for planning. GSS.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2013). 2010 Population and housing census. Regional analytical report, Upper West Region, Wa. GSS.

- Green, W. H. (2005). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Lal, R. (2020). Home gardening and urban agriculture for advancing food and nutritional security in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Security, 12(4), 871–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01058-3

- Legendre, P. (2005). Species associations: The Kendall coefficient of concordance revisited. Journal of Agricultural, Biological, and Environmental Statistics, 10(2), 226–245. https://doi.org/10.1198/108571105X46642

- Mattson, G. A. (1986). The promise of citizen coproduction: Some persistent issues: Public Productivity Review. Public Productivity Review, 10(2), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/3380451

- MoFA. (2010). Medium-Term Agriculture Sector Investment Plan (METASIP): 2011-2015. Ministry of Food and Agriculture.

- MoFA. (2017). Planting for food and jobs strategic plan for implementation (2017-2020). Ministry of Food and Agriculture.

- Nicholls, E., Ely, A., Birkin, L., Basu, P., & Goulson, D. (2020). The contribution of small-scale food production in urban areas to the sustainable development goals: A review and case study. Sustainability Science, 15(6), 1585–1599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00792-z

- Nkegbe, K. P. (2012). Technical efficiency in crop production and environmental resource management practice in Northern Ghana. Environmental Economics, 3(4), 43–51.

- Nkegbe, K. P., Abu, M. B., & Issahaku, H. (2017). Food security in the savannah accelerated development zone of Ghana: an ordered probit with household hunger scale approach. Agriculture & Food Security, 6(35), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/540066-017-0111-y

- Okello, J. J., Zhou, Y., Kwikiriza, N., Ogutu, S., Barker, I., Schulte-Geldermann, E., Atieno, E., & Ahmed, J. T. (2017). Productivity and food security effect of using of certified seed potato: The case of Kenya’s potato farmers. Agriculture & Food Security, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-017-0101-0

- Olumba, C. C., & Onunka, C. N. (2020). Banana and plantain in West Africa: Production and marketing. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 20(02), 15474–15489. https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.90.18365

- Omondi, S. O., Oluoch-Kosura, W., & Jirström, M. (2017). The role of urban-based agriculture on food security: Kenyan case studies. Geographical Research, 55(2), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12234

- Orsini, F., Kahane, R., Nono-Womdim, R., & Gianquinto, G. (2013). Urban agriculture in the developing world: A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 33(4), 695–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-013-0143-z

- Osumanu, I. K., Nyaaba, A. J., Tuu, N. G., & Owusu-Sekyere, E. (2018). From patches of villages to a municipality: Time, space, and expansion of Wa, Ghana. Urban Forum, 30(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-018-9341-8

- Raizada, N. M., & Small, A. A. F. (2017). Mitigating dry season food insecurity in the sub-tropics by prospecting drought-tolerant, nitrogen-fixing weeds. Agriculture & Food Security, 6(23), 1–14.

- Sanyé-Mengual, E., Specht, K., Krikser, T., Vanni, C., Pennisi, G., Orsini, F., & Gianquinto, G. P. (2018). Social acceptance and perceived ecosystem services of urban agriculture in Southern Europe: The case of Bologna, Italy. PloS One, 13(9), e0200993. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200993

- Siegner, A., Sowerwine, J., & Acey, C. (2018). Does urban agriculture improve food security? Examining the nexus of food access and distribution of urban produced foods in the United States: A systematic review. Sustainability (MDPI), 10(9), 2988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092988

- Tanko, M., Ismaila, S., & Sadiq, S. A. (2019). Planting for food and jobs (PFJ): A panacea for productivity and welfare of rice farmers in Northern Ghana. Cogent Economics & Finance, 7(1), 1693121. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2019.1693121

- United Nations. (2017). World population prospects: The 2017 revision. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, New York.

- United Nations. (2019). Goal 2: Zero hunger. Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/hunger/.

- van Veenhuizen, R. (2006). Cities farming for the future. In R. van Veenhuizen (Ed.), Cities farming for the future-urban agriculture for green and productive cities—Urban agriculture for green and productive cities. RUAF Foundation, International Development Research Centre and International Institute of Rural Reconstruction.

- Wamuthenya, W. R. (2010). Determinants of employment in the formal and informal sectors of the urban areas of Kenya. AERC research paper, 194. African Economic Research Consortium.

- World Bank. (2018). Third Ghana economic update: Agriculture as an engine of growth and jobs creation (English). World Bank Group.

- Xie, M., Li, M., Li, Z., Xu, M., Chen, Y., Wo, R., & Tong, D. (2020). Whom do urban agriculture parks provide landscape services to and how? A case study of Beijing, China. Sustainability, 12(12), 4967. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124967

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics: An introductory analysis (2nd ed.). Harper and Row.