Abstract

The Blackboard learning management system (LMS) is one of the online platforms for teaching a range of subjects. This study explores the perceptions of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) instructors regarding Blackboard for teaching English language skills. It also identifies the advantages and disadvantages of Blackboard compared to face-to-face (F2F) instruction. To collect data, the study employed a convergent/parallel mixed-methods (QUAN-QUAL approach) design. First, a total of 47 instructors from a Saudi university participated in completing a 7-item closed-ended questionnaire. Then, 14 teachers provided feedback through an open-ended questionnaire on the pros and cons of Blackboard versus face-to-face instruction. Data analysis techniques included descriptive statistics and thematic analysis and comparing the results. The findings demonstrate that EFL instructors have mixed responses. They favor Blackboard as an effective medium for teaching listening, reading, speaking, and pronunciation. However, they suggest that writing and grammar skills are taught face-to-face better. This research contributes to understanding Blackboard as an LMS with its pros and cons in EFL teaching and its implications for language instruction to inform decision-making processes.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Discover exciting insights into online language teaching with our paper, ‘Exploring Pedagogical Perspectives of EFL Instructors: Advantages, Disadvantages, and Implications of Blackboard as an LMS for Language Instruction’. This study focuses on the perceptions of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) instructors regarding using Blackboard, a popular learning management system (LMS), for teaching English language skills.

Through a comprehensive mixed-methods approach, we gather input from 47 instructors using a questionnaire and 14 teachers through open-ended feedback. Our findings reveal diverse opinions among EFL instructors, with Blackboard being favored for teaching listening, reading, speaking, and pronunciation. However, face-to-face instruction is more effective for writing and grammar skills.

By highlighting the advantages and disadvantages of Blackboard as an LMS, our research contributes to a deeper understanding of its implications for language instruction. This knowledge empowers decision-makers in shaping effective and engaging learning experiences for language learners.

Introduction

Technology and its application to teaching have grown in importance recently (Nasim et al., Citation2022). The sudden global switch from face-to-face (F2F) or traditional classrooms to remote and virtual teaching modes necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic was not only a transference of ‘brick and mortar’ to online space. It was a complete paradigm shift that transformed the educational landscape, eventuating many unforeseen issues and potentials (Assaiqeli et al., Citation2023). This situation affected all educational stakeholders, e.g., learners, teachers, administrators, parents, policymakers, and material developers and suppliers in many ways. Although online education (in its myriad forms) was the exclusive and only teaching mode, educators were not ready to take its implementation for granted. Globally, multiple studies were conducted to evaluate the efficacy of this ‘emergency adoption’ and forced virtual immersion.

The debate about the effectiveness of virtual learning environments (VLE) has led to bifurcating perspectives among scholars, i.e., the promoters of online instruction, such as Moser et al. (Citation2021) and Gacs et al. (Citation2020), who assert that online instruction could be a viable substitute for F2F teaching. On the other hand, the champions of traditional learning contend that virtual learning environments (VLE) have multiple issues and do not produce the desired effect (Al-Nofaie, Citation2020; Klimova, Citation2021; Pustika, Citation2020; Ramli et al., Citation2022; Rido & Sari, Citation2018). Nevertheless, Higgins et al. (Citation2007) caution us against overgeneralizing the superiority of F2F courses over online courses. Therefore, it is crucial to examine and evaluate the pros and cons of VLE for future educational practices and strike a balance between online and traditional classroom experiences.

Moreover, the failure or success of any innovations or changes in educational settings does not depend only on their induction and integration but also on how their stakeholders perceive the transformations. In the case of e-learning or online instruction, teachers’ perceptions are critical for promoting or constraining it (Azizpour, Citation2021; Bozorgian, Citation2018; Kayzouri et al., Citation2021). An instructor with robust optimism will positively affect the learning process, development, and implementation. Conversely, a faculty member with an unfavorable attitude will influence the program negatively (Azizpour, Citation2021; Moskal & Cavanagh, Citation2014). Alsaied (Citation2016), Gilakjani and Leong (Citation2012), and Mohsen and Shafeeq (Citation2014) also noted that teachers’ opinions impact how they adopt technology in the classroom. Therefore, understanding their perceptions of teaching in a VLE may be fruitful.

Context of the present study

Like the rest of the world, Saudi Arabia also had Hobson’s choice of online instruction when COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. The country adopted the Blackboard Learning Management System (LMS) as its online platform to impart education during the lockdown. Surprisingly, this adoption was slightly different in the country since sociocultural factors customized the form of online instruction, which restricted instructors and learners from using cameras, especially in girls’ colleges. They made mutual concessions and compromises, and the teaching and learning process was limited to ‘oral reciprocity’. As a result, teaching and learning the English language became somewhat difficult and different in this setting. The students might have felt more isolated and disconnected from their classmates and teachers, which could have resulted in decreased motivation and engagement, making online instruction less effective.

Since it is the teacher who carries the primary responsibility for bringing about changes in learners’ linguistic or non-linguistic behavior, his beliefs regarding teaching via Blackboard (BB) could offer valuable insights for enhancing education beyond the confines of the classroom (Washington, Citation2019). Therefore, this study aims to explore EFL instructors’ perspectives on whether teaching English language skills via Blackboard Collaborate benefits learners. The following are the research questions:

RQ1: What are EFL instructors’ beliefs towards teaching English via Blackboard (LMS)?

RQ1.1: What are EFL instructors’ beliefs towards teaching Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing (LSRW) skills via Blackboard (LMS)?

RQ1.2: What are EFL instructors’ beliefs towards teaching Vocabulary, Grammar, and Pronunciation (VGP) sub-skills via Blackboard (LMS)?

RQ2: What are the pros and cons of teaching English via Blackboard (LMS) compared to face-to-face teaching as perceived by EFL instructors?

RQ2.1: What are the pros and cons of teaching Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing (LSRW) skills via Blackboard (LMS) compared to face-to-face teaching as perceived by EFL instructors?

RQ2.2: What are the pros and cons of teaching Vocabulary, Grammar, and Pronunciation (VGP) via Blackboard (LMS) compared to face-to-face teaching as perceived by EFL instructors?

Literature review

Virtual learning environments (VLE) and English language instruction

Several studies have accounted for both the positive and negative sides of VLE and its various forms in educational contexts. For example, research by Mishra et al. (Citation2020), Chahkandi (Citation2021), and Assaiqeli et al. (Citation2023) reported that instructors had a lack of motivation, meaningful interaction, participation, engagement, and immediate feedback. Failure to understand students’ facial expressions and moods made online education uninteresting. Without F2F interaction, certain abstract subjects had more problems than others. Some of them were not sure whether their students actually participated (Mishra et al. Citation2020). Apart from a reluctance to teach online and a preference for F2F classes, glitches such as poor internet quality and malfunctioning devices caused disturbances in the course delivery. Furthermore, conducting safe and valid exams, i.e., without cheating and plagiarism, and ensuring the smooth progression of teaching were very difficult in VLE (Chahkandi, Citation2021). In addition, ELT instructors found course design for online instruction problematic and time-consuming, increasing their workload (Assaiqeli et al., Citation2023; Chahkandi, Citation2021).

Chahkandi (Citation2021) noticed some teachers shared techniques they used to solve these problems, e.g. providing online language resources for using break-out groups in LMS for speaking tasks for students’ participation and interaction, reducing the class duration, and conducting workshops for teachers. Assaiqeli et al. (Citation2023) discovered that most teachers agreed that students were at ease asking questions online, thus facilitating the teaching and making instructors aware of their needs. Therefore, despite being forced to adopt one or the other mode of online teaching as there was no alternative and having multiple issues, many teachers found online education worthwhile as this was the only choice for them to continue education during the crisis. With the help and cooperation of the management, many problems were resolved, and after some time, teachers performed their duties better.

While studying university EFL instructors’ perceptions of virtual teaching and their relationship with instructional practices using a mixed method during COVID-19, Hendrajaya et al. (Citation2023) also produced similar results to the studies of Mishra et al. (Citation2020), Chahkandi (Citation2021), and Assaiqeli et al. (Citation2023). They found that instructors had mixed attitudes, i.e. problems as well as benefits in the ‘academic cyberspace’. Those who had earlier exposure to online teaching perceived fewer difficulties, although they improved over time. Although these studies are significant, they did not shed as much light specifically on the English language teaching context as they aimed, nor did they explore any EFL teachers’ challenges in teaching language skills.

Online English language instruction via Blackboard (LMS): practices and perceptions

There are pedagogical differences between content-based subjects, i.e. sciences and arts, and skill-based subjects, i.e. languages. Teaching (English) language is more than just transferring or delivering material to learners. In other words, it is a continuous exchange of linguistic, non-linguistic, and extra-linguistic elements within a planned framework. The absence of human interaction, body language, facial expressions, or other social indicators further complicates this transition, making online instruction more demanding for EFL teachers (Almekhlafy, Citation2020; Chahkandi, Citation2021; Mishra et al., Citation2020). Therefore, EFL instructors must adjust their methods and strategies to the unique demands of online instruction.

Learning management systems (LMS) such as Blackboard Collaborate were used to teach English around the world during the pandemic. It was the official platform for teaching in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Like other VLEs, BB was also under criticism when used for teaching language skills. However, several researchers argued in favor of it. Hakim (Citation2020) surveyed EFL instructors’ beliefs about integrating BB in teaching English. The findings showed that instructors believed using Blackboard helped improve students’ language competencies. Similarly, after analyzing EFL teachers’ perceptions in five Saudi universities, Khafaga (Citation2021) found that they recognized teaching English via Blackboard Collaborate positively, i.e. participants were slightly more in favor of teaching English via Blackboard than face-to-face. In addition to these findings, Sawafta and Al-Garewai (Citation2016) and Kashghari and Asseel (Citation2014) believed that Blackboard enhances students’ academic achievement and language skills. However, Zayed (Citation2022) recently disclosed that instructors in Saudi and Egyptian universities did not like using BB at all. They thought BB did not enhance students’ language skills. The reason they implemented it was because their students were in favor of it.

Alsowayegh et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that using BB tools augmented the listening skills of Arab learners. The success of teaching listening online is also backed up by Khafaga and Shaalan (Citation2021), Khafaga (Citation2021), Hamouda (Citation2020), Gördeslioğlu & Yüzer (Citation2019), and Kashghari and Asseel (2014). They said that learners’ listening skills improved via Blackboard despite the problems they faced. Rifiyanti (Citation2020) maintains that listening skills were the most arduous task for the students to develop via BB.

Through a systematic literature review, Alanazi (Citation2023) weighed the usefulness of BB for teaching speaking skills. The findings were in favor of BB for teaching speaking skills, where students can practice in online discussions, pairs, and groups using multimedia resources. Students had personalized feedback. Similarly, Rusmiyanto et al. (Citation2023), Khafaga and Shaalan (Citation2021), Gördeslioğlu and Yüzer (Citation2019), and Hamouda (Citation2020) found that students speaking abilities and pronunciation improved if they were taught via BB. The reason is that BB is equipped with many features needed to enhance speaking skills, such as presentations, resources, teamwork, active listening, and online discussions. Students have less anxiety and shyness when practicing speaking online (Al Mahmud, Citation2022). Contrarily, Kashghari and Asseel (Citation2014) and Bich and Lian (Citation2021) found Blackboard unsuitable for improving speaking abilities. Yaumi (Citation2018) and Ivanec (Citation2022) also discovered less interaction during online speaking activities, which might have stressed learners.

Nasr (Citation2021) tested the effectiveness of BB in teaching reading and writing skills to Saudi EFL learners. The results indicated that students studying reading skills via BB were more successful than those who did not integrate BB. The study also concluded that male and female students did not have any difference while using BB to improve their reading skills. That is why teaching reading via Blackboard is the favorite skill of teachers.

Bikowski and Vithanage (Citation2016) and Motlhaka (Citation2020) analyzed L2 students’ writing experience utilizing BB to enhance their writing skills. The results showed that BB instruction within the framework of Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory (1978) improves engagement and exchange of ideas and facilitates peer and instructional feedback, which leads to improved writing skills in L2 learners. Pereira et al. (Citation2020) also had the same opinions about the merits of BB. However, they noticed plagiarism in write-ups, non-participation, the reluctance of weak learners, and that giving feedback to students takes time and effort. Therefore, these researchers maintained the superiority of the F2F writing instruction over Blackboard -based instruction. They suggested a mixed mode of both approaches to improve students’ writing skills. i.e. blended learning.

Besides, Hussein (Citation2016) demonstrated that BB is beneficial for improving Saudi learners’ vocabulary. In the same vein, Al-Qahtani (Citation2019) and Vega-Carrero et al. (Citation2017) confirmed the usability of BB for increasing vocabulary. However, according to Alamer (Citation2020), the use of BB had a minimal impact on the attitude and performance of Arab students in vocabulary learning.

Some researchers also paid attention to the use of BB for teaching pronunciation and grammar. For example, Jahara and Abdelrady (Citation2021) showed that BB improved the pronunciation skills of undergraduates with repeated drills, constant motivation, and willingness. Hamouda (Citation2020) attributed online classes’ success partly to their being fascinating, easy to access, and featuring direct feedback for EFL learners. On the other hand, disruptions at home and technical problems were mentioned by Al-Nofaie (Citation2020). In their quasi-experimental study, Elbashir and Hamza (Citation2022) discovered that teaching via Blackboard benefits the grammatical performance of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners. They further advocated the implementation of a hybrid mode for the effective teaching of grammar.

Existing research has tended to focus mainly on (EFL) students’ perceptions and (EFL) teachers’ views without giving any account of major language skills, i.e. LSRW (listening, speaking, reading, and writing), and minor skills, e.g. grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation (VGP). Furthermore, there was no discussion about which mode of teaching is more effective for teaching English. In other words, an analysis comparing teaching English via F2F and BB is missing. Therefore, to fill the gap, an attempt is made to explore EFL instructors’ views on whether teaching English language skills to EFL learners via Blackboard Collaborate is beneficial.

Methodology

Research design

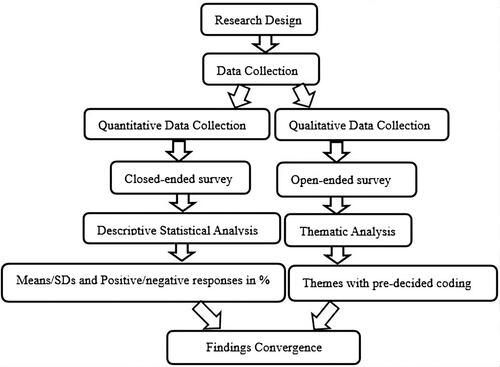

The methodology draws inspiration from similar studies that explored the effectiveness of virtual learning environments (VLEs) in language instruction (Enkin & Mejías-Bikandi, Citation2017; Gacs et al., Citation2020; Moser et al., Citation2021). Additionally, this study employed Creswell and Clark’s (Citation2018) convergent/parallel mixed methods (QUAN-QUAL approach) design to analyze both the quantitative and qualitative data to weigh EFL instructors’ perceptions of Blackboard’s usefulness for teaching English language primary skills (LSRW) and sub-skills (VGP). According to Dörnyei (Citation2007), mixed-method research is used to add meaning to numbers, and these numbers may be used to add precision to words (p. 45). In other words, quantitative and qualitative methods are combined in one research project to use the best parts of each method, i.e. their strengths (Dörnyei, Citation2007). In mixed-methods research, different data collection strategies are used—for example, interviews, surveys, observation, focus group discussion, etc. Then, these techniques are integrated to support, explain, or maximize to get a better and more precise picture of the responses of the sample(s). This procedure is called triangulation (Creswell & Clark, Citation2018). Adopting this methodology ensures a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter and promotes informed decision-making.

The researchers used two surveys in this study: closed-ended and open-ended questionnaires. The first survey consisted of seven items on a Likert scale to obtain quantitative data on teachers’ opinions about the usability of Blackboard. This data was analyzed and summarized to identify instructors’ opinions, trends, and patterns about ‘EFL Teachers’ Beliefs about Teaching English via Blackboard vs. Face-to-face’. A second tool for eliciting qualitative data to answer the question ‘What are the advantages and disadvantages of teaching EFL skills via Blackboard’, comprising seven open-ended questions was also used for richer, more nuanced insights into instructors’ experiences and perspectives. These open-ended questions were studied for common themes and used to explain the quantitative data further. displays the research design.

Figure 1. Convergent/parallel mixed methods design: a(QUAN-QUAL) approach based on Creswell and Clark (Citation2018).

Participants

All male and female EFL teachers working at the English language unit, Preparatory Year Deanship, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia, were given the closed-ended questionnaire first. They were told the research objectives and assured that the results would be utilized only for research purposes. The survey was distributed by the researchers’ representatives among both male and female WhatsApp groups. Only forty-seven EFL instructors (22 males and 25 females) responded to it. They were both native and non-native English speakers, aged 27–58. Their experience teaching English varied from 3–20 years. They had been using Blackboard (LMS) for at least one year. Most of them did not have any training to carry out academic activities using BB. A test of normality was performed on the sample’s beliefs about using Blackboard (LMS) for teaching English to EFL learners. The respondents’ Shapiro-Wilk value (as n ≤ 50) was 0.608, indicating that the distribution of the sample data was normal.

For the second research tool, 14 out of the 47 instructors were chosen through purposive sampling to receive their responses to seven open-ended questions, and respondents freely expressed their views on teaching EFL skills via Blackboard (LMS). By selecting a cross-section of participants from different backgrounds and experiences, the study aimed to generate more comprehensive and diverse findings. Their views were analyzed using thematic analysis. Researchers’ representatives helped collect data at this stage, too.

Instruments and data collection procedure

A closed-ended questionnaire created by the researchers was administered to EFL instructors to gather data on their perceptions of Blackboard’s usefulness in teaching English language skills and sub-skills to EFL learners. It consisted of seven statements asking them to express their opinions on a five-point Likert scale, i.e. ranking them from ‘Strongly Agree’ to ‘Strongly Disagree’. In other words, number ‘1’ was given the highest disagreement score, and number ‘5’ was given the highest agreement score. The ‘uncertain’ was marked with a ‘3’. ‘Disagree’ and ‘Agree’ were numbered as ‘2’ and ‘4’, respectively. This questionnaire was created on Google Forms and sent to all participants via WhatsApp in the first phase. The Cronbach’s alpha test was utilized to evaluate the reliability of the questionnaire. The coefficient of (r) was 0.89, indicating high reliability. Since the validity coefficient is the square root of the reliability coefficient, the validity coefficient would be 0.79, which is quite good.

In the second phase, the researcher instructed the participants to answer seven open-ended questions, i.e. to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of teaching English through Blackboard compared to F2F instruction. Out of 47, only 14 selected instructors were emailed these questions in a Word file. They responded to the open-ended survey within three days.

Two English-language instructors reviewed and validated both sections of the data collection tool. One of them was a Ph.D. with more than 15 years of experience. The other had a master’s degree in English, post-graduate ELT certification, and 11 years of teaching experience. Some linguistic and technical modifications were made according to their suggestions.

Data analysis procedures

The collected quantitative data was subjected to descriptive statistical techniques such as percentages, frequencies, standard deviations, and mean scores using the statistical software SPSS version 27. EFL instructors’ preferences were interpreted by following the rules mentioned in . The frequencies of ‘Strongly Agree’ and ‘Agree’ were combined to represent positive responses, and ‘Strongly Disagree’ and ‘Disagree’ were combined to show negative answers to respond to the research questions.

Table 1. Score ranges for low, moderate, and high.

Subsequently, the qualitative data obtained from the open-ended questions was analyzed using thematic analysis. The results of this qualitative analysis are presented in , which outline the prominent themes that emerged from teachers’ responses, such as the pros and cons of teaching reading, writing, listening, speaking, vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation via BB.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of EFL teachers’ beliefs about teaching english via blackboard.

Table 3. Pros and cons of teaching listening skills via blackboard (LMS).

Table 4. Pros and cons of teaching speaking skills via blackboard (LMS).

Table 5. Pros and cons of teaching reading skills via blackboard (LMS).

Table 6. Pros and cons of teaching writing skills via blackboard (LMS).

Table 7. Pros and cons of teaching vocabulary skills via blackboard (LMS).

Table 8. Pros and cons of teaching grammar skills via blackboard (LMS).

Table 9. Pros and cons of teaching pronunciation skills via blackboard (LMS).

Finally, the quantitative and qualitative strands were analyzed separately, and then the results were merged during the interpretation phase to obtain a complete understanding of teachers’ perspectives. Combining both closed-ended and open-ended data collection tools allowed for comparisons between the quantitative predetermined scale responses and qualitative themes to determine if participants responded similarly across methodologies regarding their beliefs about Blackboard versus face-to-face teaching.

Findings

The present study set out to answer two primary questions. There were two subsidiary and associated questions, with each main question concerning the EFL instructors’ beliefs about using BB and their perceived advantages and disadvantages of teaching English using the platform compared to F2F instruction. The individual mean scores in were compared with the values in to answer the first main and the two subsidiary research questions.

EFL instructors’ beliefs towards teaching English via Blackboard compared to face-to-face teaching

All mean scores in show moderate levels. The individual mean scores indicated the degree of perceived improvement in English with their skills when taught via Blackboard. Specifically, respondents perceived that listening (M = 3.28, SD = 1.08) and reading (M = 3.23, SD = 1.01) could be improved more than other skills if taught via Blackboard. Following these skills is vocabulary. The average score is 3.15, and the standard deviation is 0.98. Pronunciation comes in fourth with a mean score of 3.09 and a standard deviation of 1.16. After that, speaking comes in with a mean score of 3.04 and an SD of 1.14. Grammar skill is next, with a mean score of 2.98 and a standard deviation of 1.09. The lowest mean on writing skill (M = 2.66, SD = 1.24) implies that this is the most minor improvable skill if taught via Blackboard.

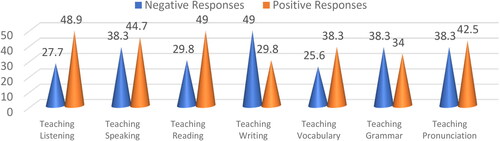

Furthermore, in analyzing the data on the total agreement and disagreement on the usefulness of Blackboard (LMS) for improving LSRW (Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing) and VGP (Vocabulary, Grammar, and Pronunciation), the positive and negative preferences of the respondents were combined and presented in .

From the combined positive and negative preferences in , it is evident that the respondents were divided into two groups in terms of opinions on teaching English language skills (LSRW) and subskills (VGP) via Blackboard (LMS). They had both negative and positive preferences, apart from being uncertain. For example, 48.9% of the respondents held a positive view about teaching listening, while 27.7% held an opposing view. Similarly, 49.0% of the respondents had a positive outlook on reading skills, whereas 29.8% held a negative opinion. Regarding speaking skills, 44.7% of the respondents exhibited a positive attitude, while 38.3% had a negative perception. When it came to the teaching of writing skills, they had 29.8% positive and 49% negative responses. The responses for teaching vocabulary showed 38.3% positivity and 25.6% negativity, while teaching grammar received 34% positive and 38.3% negative preferences. Lastly, teaching pronunciation received 42.5% positive and 38.3% negative attitudes. Overall, these findings demonstrate the mixed opinions and preferences of the respondents when it comes to teaching English language skills and subskills through the use of Blackboard.

EFL instructors’ perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of teaching English through Blackboard in comparison to F2F instruction

Below are the tables that summarize EFL instructors’ answers to seven open-ended questions centered on the pros and cons of teaching English via Blackboard compared to F2F instruction. In particular, these seven questions concern listening, speaking, reading, writing, vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation when using Blackboard to learn English. They can also provide valuable insights into their mixed views about online teaching.

summarizes that many instructors conveyed that improved listening skills were evident when utilizing Blackboard as the instructional platform. They highlighted that teaching listening through Blackboard offered flexibility, reduced interruptions, and enabled more focused attention on individual learners. Moreover, they found it convenient to access relevant materials online. The synchronous and asynchronous availability of learning resources also fostered learner autonomy and facilitated self-paced learning.

On the other hand, the instructor shared their views on the problems associated with using the Blackboard. These are difficulties in managing the classrooms , less interaction between student-teachers, a low bandwidth of internet connectivity, and a low quality of devices used by students. Also, they argued that it was not easy to know who was attentive during the classes. Occasionally, external distractions at home were also a negative factor.

The responses to teaching speaking skills () revealed that some instructors reported that their students were more confident behind the screen compared to when classes were conducted F2F. Perhaps it helped them lower their anxiety or affective filter. Break-out groups allowed shy and introverted students to practice speaking without fear or feeling nervous. Using the feature, they shared that they could select, talk to, or mute an individual student without interrupting other participants. This option cannot be found in F2F teaching, and therefore, it assisted them in creating a conducive online learning environment. Consequently, more personalized feedback was given to students.

Nevertheless, teaching speaking skills through Blackboard suffered some drawbacks as well. Instructors believed speaking was less effective than in a traditional classroom without eye contact, body language, facial expressions, and gestures. Off-camera students needed help supervising and controlling during role play and group activities. Internet disruptions and microphone malfunctions negatively impacted speaking flow. Some students became dominant during group activities, which might have been demotivating for weaker students.

Blackboard was also the most suitable medium for teaching reading, as instructors expressed stronger beliefs about it. Teachers used online tools to teach reading and found that the learners’ overall involvement in learning improved, and their skills improved. Their responses are displayed in .

Teachers had book-sharing options and other online reading material that could be read by voice. They had books on their screens and did not have any diversions. Students needed to focus on the screen and what the teacher instructed; as a result, they developed a sense of responsibility and independent reading habits. This proved better for shy and introverted students, who were prone to making more mistakes under pressure. The instructors also provided personalized feedback. As it was impossible to monitor them off-camera, students’ non-participation could not be noticed. Some students did not like reading on Blackboard because they liked reading hard copies of the books. Instructors felt that error correction was better in face-to-face mode. Overall, teaching reading via Blackboard, according to the respondents, was preferred.

Instructors’ choices also showed moderate support for teaching writing skills via Blackboard. In comparison to other skills, instructors perceived teaching writing skills to be complex, as shown in .

Although there were some benefits to teaching students writing skills online, such as automatic correction tools, paraphrasing, finding a problematic word and translation, and more model paragraphs, many instructors believed that students should be taught writing face-to-face. According to these instructors, the downsides of teaching writing via Blackboard were difficulty correcting mistakes online, monitoring, cheating, and guiding students along every step of the writing process. Ideas generation exercises such as brainstorming were challenging via Blackboard. Further, typing slowed down writing activities and discouraged some students. They used to take screenshots instead of writing, which hampered their cognitive involvement.

The results also demonstrate that teaching via Blackboard Collaborate improves learners’ vocabulary skills more than face-to-face teaching. It means teachers noticed the overall improvement in learners and their curiosity towards improving vocabulary learning. The instructors mentioned the pluses of teaching vocabulary via Blackboard. They believed instructors and students could use multiple resources while teaching vocabulary items. Pronunciation, synonyms and antonyms, idioms, parts of speech, and example sentences can be taught easily via Blackboard. Instructors can use illustrations and pictures to help students understand complex words. Students can receive immediate feedback using this method. Students have more time to research the vocabulary online, making them autonomous. The auto-correction option helps students learn to spell. Weaker learners are more convenient for clarification. Online vocabulary games can enhance students’ vocabulary.

The teaching of vocabulary via Blackboard has limitations, too. The participants stated that using natural objects to teach vocabulary is difficult, especially with no camera. In face-to-face English, the teacher introduces new vocabulary quickly and checks students’ understanding by watching their faces, which is impossible in Blackboard teaching. While teaching vocabulary in a classroom, teachers and students can act out concepts and make meanings evident to all because everyone can see and understand. Teaching English via Blackboard in this context does not offer such an opportunity. It is more accessible to teach vocabulary face-to-face because vocabulary teaching requires physical interactions and physical efforts like reading newspapers, books, articles, research papers, etc. The merits and demerits of teaching vocabulary via BB and F2F have been listed below in .

Teaching grammar online is also favored by instructors. They believed that teaching grammar via Blackboard was better than F2F. The positivity outweighed the negativity in this case, too. Teachers noticed that more examples of grammar activities can be shared with students on the internet, and grammar activities can be done quickly. Illustrations and pictures also helped students understand grammar points. It can be taught by preparing quizzes on Blackboard, where students can enhance their skills. These points develop motivation and interest. Students improve their grammar and become more involved in learning. On the other hand, weaker learners may be reluctant to ask for more clarification. They will get examples online instead of creating their own answers. It is challenging and time-consuming for teachers to prepare and share grammar tasks with students. These responses are summarized in .

Among the three subskills, pronunciation is the second subskill, which instructors believed improved the most when students were instructed via Blackboard (LMS). They mentioned that teaching pronunciation through this mode benefits instructors and students. For example, teachers can use several resources, such as online dictionary websites and YouTube software for sound contours and oral cavities, to understand the pronunciation of words. There are American and British accents available online. This way, identifying stress and intonation markers in exercises is easier for learners than face-to-face. Blackboard is an excellent platform for teaching pronunciation to shy students, as they may feel more confident participating. They can improve their pronunciation by being given a task daily and multiple times or by using drilling activities and shadowing techniques to help them speak up since being in a virtual learning program requires less effort.

While the advantages of teaching pronunciation online are noteworthy, the teaching of pronunciation online is not free from shortcomings. Many instructors believed some students might find learning pronunciation via Blackboard difficult, as face-to-face teaching provides more opportunities to model and imitate various sounds. They need help understanding the place of articulation and the work of different speech organs. Teachers cannot see how their students pronounce the word. Many students may have external distractions that hinder their progress and divert their attention from pronunciation learning. Technical problems with the microphone or the students’ devices might interfere with learning the pronunciation of a word. These pros and cons are summarized in .

Discussion

The participants’ responses elicited by means of a closed-ended survey and an open-ended descriptive analysis underscored the viewpoints of EFL instructors concerning the effectiveness of BB in teaching primary skills (LSRW) and subsidiary English language skills (VGP). Moreover, the instructors spelled out the pros and cons of teaching English language skills via Blackboard compared to F2F.

The results from the Likert scale indicated that instructors believed that BB moderately impacted boosting learners’ language skills. In other words, using BB enhanced their English proficiency. This trend was indicated by teachers’ positive and negative outlooks on using BB in teaching English. A large number of participants thought reading, listening, and speaking skills were enhanced via BB. Yet, almost a quarter of participants said teaching reading and listening skills via BB was not a good idea. However, many of them did not find BB suitable for teaching speaking. Also, most teachers did not want to teach writing skills via BB. Only less than one-third of instructors expressed interest in teaching writing using BB. Similar to the primary skills, the majority of the instructors were in favor of teaching pronunciation and vocabulary, but only a quarter number of teachers did not approve of BB for teaching vocabulary. Moreover, the number of teachers who did not want to teach grammar using BB was higher than those who thought grammar could be taught effectively using BB.

Another noticeable display of instructors’ beliefs in the study was their being neutral or unable to decide what to choose. Many choices (16.1–25 on a Likert scale) are in the uncertain column. Pusuluri et al. (Citation2017) and Al-Nofaie (Citation2020) found the same about learners’ preferences for Blackboard learning over face-to-face learning. Inferring from that, it can be said that this indeterminate state could have resulted from instructors’ lack of preparedness, less exposure to online teaching, and not letting the administration know that they were unaware of this novel mode of education, which might have cost their jobs. Herman (Citation2013) and Gufron and Rosli (Citation2020) also confirmed these in their studies.

Many previous studies conducted during COVID-19 and earlier support the use of online and BB, as mentioned in the literature review. At the same time, they also acknowledge the undeniable significance of F2F mode. However, in this study, it is revealed by the descriptive statistics that EFL instructors were more inclined toward utilizing the BB for teaching English language skills, except for writing and grammar. Consequently, it may be inferred that each teaching mode possesses its own unique set of advantages and disadvantages. The polarized findings motivate Chiasson et al. (Citation2015) to declare that replicating the F2F classroom experience is only possible in an online setting with some adjustments.

Even though more and more people are gearing towards using e-learning, virtual learning, and online teaching, face-to-face mode retains its significance. F2F interactions conventionally bring more human values and direct social interaction between fellow students-students and students-teachers. Besides that, students and teachers face obstacles in internet accessibility, the availability of hardware and software, and the cost of maximizing online learning resources. Rahman (Citation2023) argues that face-to-face is not only difficult but irreplaceable; however, LMS enhances traditional learning. The limitations of teaching English online or via Blackboard could be overcome by face-to-face teaching. Similarly, Ng (Citation2007) states that online instruction should enhance face-to-face interaction, not replace it. These mixed views of the participants have ruled out the possibility of face-to-face teaching being replaced by online education.

This situation brings up a hybrid approach called blended learning, where both modes of teaching converge. A group of researchers has supported using the blended method in teaching. According to Barnett and Aagaard (Citation2005), the outcome hinges on objectives, methods, and mediums, with teachers’ skills and the nature of activities playing a crucial role. In English language teaching, reliance should not be solely placed on Blackboard or F2F instruction. Students expect online learning to be combined with face-to-face learning (Elbashir & Hamza, Citation2022; Gufron & Rosli, Citation2020; Pereira et al., Citation2020). In other words, a hybrid or blended teaching mode will boost the efficacy of educational instruction (Itmazi & Tmeizeh, Citation2008). Consequently, the researchers recommend the adoption of blended learning as a strategy to overcome the identified obstacles.

Conclusion

Overall, the current study’s findings broadly support the work of other studies elaborating on the advantages and disadvantages of using BB compared to F2F instruction among EFL instructors in language teaching and learning. One mode does not have superiority over the other. Accordingly, Streat (Citation2014) posits that there is a common misconception that online English language classes are inferior to traditional classroom-based learning. However, this is a myth. Online English language classes can be as practical as learning from a tutor in a classroom setting, although the learning experience may differ. It is important to note that online language study may only be suitable for some, and individuals have different learning preferences and needs.

Similarly, Higgins et al. (Citation2007) argue that good teaching remains effective regardless of whether it is delivered through technology. Blake (Citation2013) suggests that each instructor’s talents and limitations and the quality of learning materials are more significant indicators of student learning than the course format. In other words, the effectiveness of a language course cannot be determined solely by its delivery format. It should be evaluated based on other factors, such as teaching quality and learning materials. To make an informed decision about language courses, it is crucial to consider various factors, e.g. the instructor’s abilities, the quality of the course materials, and the learning environment, rather than solely focusing on the delivery format.

Limitations and recommendations

One limitation of the study was that the subjects’ views were mostly theoretical and anecdotal rather than purely statistical. Thus, further research could help identify the advantages and disadvantages of BB collaboration on subjects with a more substantial and practical awareness of the learning process. As such, this study provides only perceptual data showing that teaching via BB enhances the learners’ language skills and subskills. Since the study had a limited number of respondents, the generalizability of these results should be avoided. To improve the findings, research, including larger samples, is needed.

Moreover, the research tools were not pilot-tested. Nasim and Mujeeba (Citation2024) argued that ‘piloting the research instruments prior to implementation helps identify issues, refine them, and improve data reliability’. In future studies, using standardized and validated tools will enhance comparability across different research contexts.

In the new normal, the inclusivity of this method has grown (Mohamed et al., Citation2023). Preparing for disasters (such as the COVID-19 pandemic), according to Fageeh (Citation2011), is critical. Therefore, Nasim and Mujeeba (Citation2021) propose ‘changing the gears as per the requirement to produce effectiveness’. For example, before COVID-19, classes had to be canceled if there were any situations where students could not attend college physically due to weather turbulence such as heavy rain, sandstorms, or something else. Nevertheless, the adaptation to these new modes of instruction, such as Blackboard (LMS), made education possible without any interruptions. This may, however, present significant challenges for EFL teachers, such as a lack of access to technology, poor internet connectivity, and language barriers.

Finally, more research should be conducted to discover the impact of BB learning on students’ English language skills. The results of the current study help academic institutions, faculty, decision-makers, and students improve the essential skills needed for online/Blackboard learning and teaching English language skills and subskills.

Ethical approval

We hereby declare that this manuscript is the result of our creation. The manuscript does not contain any research that has been published or written by other individuals or groups. We are the genuine authors of this manuscript. The legal responsibility of this statement shall be borne by us.

Informed consent

Participants provided informed consent, understanding the study’s purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits. Participation was voluntary, and withdrawal was possible at any time without consequences. Confidentiality and privacy of participants’ data were ensured.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data and materials used in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Saleem Mohd Nasim

Saleem Mohd Nasim is a dedicated researcher and educator currently affiliated with Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia. With a Ph.D. in English from India and a strong academic background, he holds the National Eligibility Test (NET-English) and the State Eligibility Test (APSET-Education) certifications. With over fifteen years of teaching experience in India and Saudi Arabia, Nasim’s expertise lies in English Language Teaching (ELT), testing and evaluation, teaching of literature, stylistics, and educational technology. His research activities encompass various topics, focusing on enhancing language instruction through technology integration. His work explores using learning management systems, such as Blackboard, to optimize language learning experiences for students and instructors. This research contributes to the broader discourse on educational technology and pedagogical practices in English language education by investigating the advantages and disadvantages of Blackboard as an LMS for language instruction.

Syeda Mujeeba

Syeda Mujeeba is an English language instructor at the English Language Unit, Preparatory Year Deanship (PYD), Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, AlKharj, Saudi Arabia. She holds an M.A. (English), a PGCTE, and a PGDTE from India. She is also a PhD scholar at UMPSA, Malaysia. She has 10 years of teaching experience in India and Saudi Arabia. Her research interests are issues in ELT and educational technology.

Shadi Majed AlShraah

Shadi Majed AlShraah is currently a lecturer at Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Kharj, Saudi Arabia. He has 14 years of experience in teaching. He holds a PhD in linguistics from the University of Sains Islam Malaysia (USIM). His interests revolve around pragmatics, socio-pragmatics, and teaching English as a second or foreign language (EFL or ESL).

Irshad Ahmad Khan

Irshad Ahmad Khan was awarded an MA (Linguistics) in 2001 from AMU, India. He is a qualified English teacher with 15 years of experience with English language learners. He taught at Najran University, KSA, and now serves at Jizan University, KSA. Eager to learn and participate in research projects within the approachable terrain of global researchers.

Amir

Amir Khan is an assistant professor with a solid foundation in applied linguistics. He has completed his doctoral studies at Aligarh Muslim University, where he demonstrated a keen intellect and a commitment to pushing the boundaries of English language teaching. His research interests are ELT, modern testing and evaluation, and educational technology.

Zuraina Ali

Zuraina Ali works as an associate professor at Universiti Malaysia Pahang al-Sultan Abdullah. She has been an educator for twenty-six years. With an emphasis on ESL and EFL instruction, her areas of expertise include research methodology, adult English instruction, and the use of technology in language teaching. She can be contacted at [email protected].

References

- Al Mahmud, F. (2022). Teaching and learning English as a foreign language speaking skills through Blackboard during COVID-19. Arab World English Journal, 8, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/call8.15

- Alamer, H. (2020). Impact of using Blackboard on vocabulary acquisition: KKU students’ perspective. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 10(5), 598. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1005.14

- Alanazi, S. A. (2023). A systematic review of the Blackboard in teaching the speaking skill during the Corona pandemic COVID-19. Migration Letters, 20(S3), 773–797.

- Almekhlafy, S. S. A. (2020). Online learning of English language courses via Blackboard at Saudi universities in the era of COVID-19: perception and use. PSU Research Review, 5(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/PRR-08-2020-0026

- Al-Nofaie, H. (2020). Saudi university students’ perceptions towards virtual education during Covid-19 pandemic: A case study of language learning via Blackboard. Arab World English Journal, 11(3), 4–20. volume https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol11no3.1

- Al-Qahtani, M. H. (2019). Teachers’ and students’ perceptions of virtual classes and the effectiveness of virtual classes in enhancing communication skills. Arab World English Journal (Special Issue: The Dynamics of EFL in Saudi Arabia). 223–240. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/efl1.16

- Alsaied, H. I. K. (2016). Use of blackboard application in language teaching: Language teachers’ perceptions at KAU. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 5(6), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.5n.6p.43

- Alsowayegh, N. H.,Bardesi, H. J.,Garba, I., &Sipra, M. A. (2019). Engaging students through blended learning activities to augment listening and speaking. Arab World English Journal, (5), 267–288. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/call5.18

- Assaiqeli, A., Maniam, M., Farrah, M., Morgul, E., & Ramli, K. (2023). Challenges of ELT during the new normal: A case study of Malaysia, Turkey and Palestine. International Journal of Arabic-English Studies, 23(1), 377–400. https://doi.org/10.33806/ijaes2000.23.1.20

- Azizpour, S. (2021). A probe into Iranian EFL university lecturers’ perspectives toward online instruction during the coronavirus pandemic. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 9(39), 117–140. https://jfl.iaun.iau.ir/article_683978_4a974d119a7c5bd11668a7be0634bfbb.pdf

- Barnett, D., & Aagaard, L. (2005). Online vs. face-to-face instruction: Similarities, differences, and efficacy. Faculty Research at Morehead State University, 872, 1–29. https://scholarworks.moreheadstate.edu/msu_faculty_research/872

- Bich, T. N. C., & Lian, A. (2021). Exploring challenges of major English students towards learning English speaking skills online during Covid 19 pandemic and some suggested solutions [Paper presentation]. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 621, 135-144. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.211224.014

- Bikowski, D., & Vithanage, R. (2016). Effects of web-based collaborative writing on individual L2 writing development. Language Learning & Technology, 20(1), 79–99. http://llt.msu.edu/issues/february2016/bikowskivithanage.pdf

- Blake, R. (2013). Best practices in online learning: Is it for everyone? In F. Rubio, J. J. Thoms, & S. K. Bourns (Eds.), AAUSC 2012 Volume--Issues in language program direction: Hybrid language teaching and learning: Exploring theoretical, pedagogical and curricular issues, 10 (Chapter 2, pp. 10–26). Boston: Heinle. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/69708

- Bozorgian, H. (2018). Teachers’ attitudes towards the use of MALL instruction in Iranian EFL context. The International Journal of Humanities, 25(3), 1–18. http://eijh.modares.ac.ir/article-27-44331-en.html

- Chahkandi, F. (2021). Online pandemic: Challenges of EFL faculty in the design and implementation of online teaching amid the COVID-19 outbreak. Foreign Language Research Journal, 10(4), 706–721. https://doi.org/10.22059/JFLR.2021.313652.774

- Chiasson, K., Terras, K., & Smart, K. (2015). Faculty perceptions of moving a face-to-face course to online instruction. Journal of College Teaching & Learning (TLC), 12(3), 321–240. https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v12i3.9315

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Oxford University Press.

- Elbashir, R. M., & Hamza, S. M. A. (2022). The impact of virtual tools on EFL learners’ performance in grammar at the times of COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 19(3), 7. https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol19/iss3/07 https://doi.org/10.53761/1.19.3.07

- Enkin, E., & Mejías-Bikandi, E. (2017). The effectiveness of online teaching in an advanced Spanish language course. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 27(1), 176–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12112

- Fageeh, A. I. (2011). EFL students’ readiness for e-learning: Factors influencing e-learners’ acceptance of the Blackboard in a Saudi university. The JALT CALL Journal, 7(1), 19–42. https://doi.org/10.29140/jaltcall.v7n1.106

- Gacs, A., Goertler, S., & Spasova, S. (2020). Planned online language education versus crisis-prompted online language teaching: Lessons for the future. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 380–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12460

- Gilakjani, A. P., & Leong, L. M. (2012). EFL teachers’ attitudes toward using computer technology in English language teaching. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(3), 630–636. http://dx.doi.org/10.4304/tpls.2.3.630-636

- Gördeslioğlu, N. G., & Yüzer, T. E. (2019). Using LMS and blended learning in designing a course to facilitate foreign language learning. KnE Social Sciences, 3(24), 10–25 https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v3i24.5164

- Gufron, & Rosli, R. M. (2020). The transition in learning English from face to face to online instructions in higher education level in Indonesia: A view from students’ perspective. American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS), 12(3), 101–112. https://www.arjhss.com/wp-content/uploads/ 2020/12/L312101112.pdf

- Hakim, B. M. (2020). EFL teachers’ perceptions and experiences on incorporating blackboard applications in the learning process with modular system at ELI. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 12(2), 392–405. https://www.ijicc.net/images/vol12/iss2/12230_Hakim_2020_E_R.pdf

- Hamouda, A. (2020). The effect of virtual classes on Saudi EFL students’ speaking skills. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation, 3(4), 175–204. https://doi.org/10.32996/ijllt.2020.3.4.18

- Hendrajaya, M. R., Hongboontri, C., & Boonyaprakob, K. (2023). EFL teachers perceptions of online education amidst Covid-19 pandemic in Thailand. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences, 15, 377–390. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23097.34

- Herman, J. H. (2013). Faculty incentives for online course design, delivery, and professional development. Innovative Higher Education, 38(5), 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-012-9248-6

- Higgins, S., Beauchamp, G., & Miller, D. (2007). Reviewing the literature on interactive whiteboards. Learning, Media and Technology, 32(3), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439880701511040 https://doi.org/10.59670/ml.v20iS3.3819

- Hussein, H. E. G. M. (2016). The effect of Blackboard collaborate-based instruction on pre-service teachers’ achievement in the EFL teaching methods course at faculties of education for girls. English Language Teaching, 9(3), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n3p49

- Itmazi, J. A., & Tmeizeh, M. J. (2008). Blended eLearning approach for traditional Palestinian universities. IEEE Multidisciplinary Engineering Education Magazine, 3(4), 156–162.

- Ivanec, T. P. (2022). The lack of academic social interactions and students’ learning difficulties during covid-19 faculty lockdowns in Croatia: the mediating role of the perceived sense of life disruption caused by the pandemic and the adjustment to online studying. Social Sciences, 11(2), 42. MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020042

- Jahara, S. F., & Abdelrady, A. H. (2021). Pronunciation problems encountered by EFL learners: An empirical study. Arab World English Journal, 12(4), 194–212. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol12no4.14

- Kashghari, B., & Asseel, D. (2014). Collaboration and interactivity in EFL learning via Blackboard collaborate: A pilot study [Paper presentation]. Conference Proceedings. ICT for Language Learning (p. 149).

- Kayzouri, A. H., Mohebiamin, A., Saberi, R., & Bagheri-Nia, H. (2021). English language professors’ experiences in using social media network Telegram in their classes: A critical hermeneutic study in the context of Iran. Qualitative Research Journal, 21(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-02-2020-0008

- Khafaga, A. F. (2021). The perception of Blackboard collaborate-based instruction by EFL majors/teachers amid COVID-19: A case study of Saudi universities. Dil ve Dilbilimi Çalışmaları Dergisi, 17(2), 1160–1173. https://doi.org/10.17263/jlls.904145

- Khafaga, A. F., & Shaalan, I. E. N. A. W. (2021). Mobile learning perception in the context of COVID-19: An empirical study of Saudi EFL majors. Asian EFL Journal, 28(13), 336–356.

- Klimova, B. (2021). An insight into online foreign language learning and teaching in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Procedia Computer Science, 192, 1787–1794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.08.183

- Mishra, L., Gupta, T., & Shree, A. (2020). Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 1, 100012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100012

- Mohamed, A. M., Nasim, S. M., Aljanada, R., & Alfaisal, A. (2023). Lived experience: Students’ perceptions of English language online learning post COVID-19. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 20(7), 12. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.20.7.12

- Mohsen, M. A., & Shafeeq, C. P. (2014). EFL teachers’ perceptions on blackboard applications. English Language Teaching, 7(11), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n11p108

- Moser, K. M., Wei, T., & Brenner, D. (2021). Remote teaching during COVID-19: Implications from a national survey of language educators. System, 97, 102431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102431

- Moskal, P. D., & Cavanagh, T. B. (2014). Scaling blended learning evaluation beyond the university. In A. G. Picciano, C. D. Dziuban, & C. R. Graham (Eds.), Blended learning: Research perspectives (Vol. 2, pp. 34–51). Routledge.

- Motlhaka, H. (2020). Blackboard collaborated-based Instruction in an academic writing class: Sociocultural perspectives of learning. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 18(4), 336–345. https://doi.org/10.34190/EJEL.20.18.4.006

- Nasim, S. M., AlTameemy, F., Ali, J. M. A., & Sultana, R. (2022). Effectiveness of digital technology tools in teaching pronunciation to Saudi EFL learners. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 16(3), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.51709/19951272/Fall2022/5

- Nasim, S. M., & Mujeeba, S. (2021). Learning styles of Saudi ESP students. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 13(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v13n4.55

- Nasim, S. M., & Mujeeba, S. (2024). Arab EFL students’ and instructors’ perceptions of errors in mechanics in second language paragraph writing. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 18(1).

- Nasr, M. A. A. N. (2021). The effectiveness of the blackboard technique in integrating SAUDI university students’ English-language reading and writing skills. Jordan Journal of Educational Sciences, 17(4), 663–674. https://doi.org/10.47015/17.4.12

- Ng, K. C. (2007). Replacing face-to-face tutorials by synchronous online technologies: Challenges and pedagogical implications. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 8(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v8i1.335

- Pereira, E. A., Manaf, N. M. A., & Thayalan, J. X. M. X. (2020). Effectiveness and efficiency in assessing students writing skills via selected Blackboard tools. International Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 2(4), 76–83. https://myjms.mohe.gov.my/index.php/ijeap/article/view/11424

- Pustika, R. (2020). Future English teachers’ perspective towards the implementation of e-learning in Covid-19 pandemic era. Journal of English Language Teaching and Linguistics, 5(3), 383–391. https://jeltl.org/index.php/jeltl/article/view/448/pdf https://doi.org/10.21462/jeltl.v5i3.448

- Pusuluri, S., Mahasneh, A., & Alsayer, B. A. M. (2017). The application of Blackboard in the English courses at Al Jouf University: perceptions of students. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 7(2), 106. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0702.03

- Rahman, P. (2023). An investigation into EFL students’ experiences toward the use of moodle and its implementation challenges at institut parahikma indonesia. ETERNAL, 9(01) https://doi.org/10.24252/Eternal.V91.2023.A4

- Ramli, K., Assaiqeli, A., Mostafa, N. A., & Singh, C. K. S. (2022). Gender perceptions of benefits and challenges of online learning in Malaysian ESL classroom during COVID-19. Studies in English Language and Education, 9(2), 613–631. https://doi.org/10.24815/siele.v9i2.21067

- Rido, A., & Sari, F. M. (2018). Characteristics of classroom interaction of English language teachers in Indonesia and Malaysia. International Journal of Language Education, 2(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.26858/ijole.v2i1.5246

- Rifiyanti, H. (2020). Learners’ perceptions of online English learning during COVID-19 pandemic. Scope: Journal of English Language Teaching, 5(1), 31–35. https://doi.org/10.30998/scope.v5i1.6719

- Rusmiyanto, R., Huriati, N., Fitriani, N., Tyas, N. K., Rofi’i, A., & Sari, M. N. (2023). The role of artificial intelligence (AI) in developing English language learner’s communication skills. Journal on Education, 6(1), 750–757. https://doi.org/10.31004/joe.v6i1.2990

- Sawafta, W., & Al-Garewai, A. (2016). The effectiveness of blended learning, based on the learning management system "blackboard," in the direct and delayed achievement of physics and learning retention among the students of health colleges at king Saud university. Journal of Educational and Psychological Studies, King Saud University, 10(3), 476–479. https://doi.org/10.24200/jeps.vol10iss3pp476-497

- Streat, S. (2014). Learning English online is as good as learning English face to face. Here’s why. | English with a Twist. English With a Twist. https://englishwithatwist.com/2014/04/07/learning-english-online-is-as-good-as-learning-english-face-to-face-heres-why/

- Vega-Carrero, S., Pulido, M., & Ruiz-Gallego, N. E. (2017). Teaching English as a second language at a university in Colombia that uses virtual environments: a case study. Revista Electrónica Educare, 21(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.21-3.9

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Harvard University Press.

- Washington, G. Y. (2019). The learning management system matters in face-to-face higher education courses. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 48(2), 255–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239519874037

- Yaumi, M. (2018). Media dan teknologi pembelajaran. Prenadamedia Group.

- Zayed, E. (2022). Perceptions of EFL instructors towards features of blackboard and smartboard tools. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results, 13(7), 5290–5306. https://doi.org/10.47750/pnr.2022.13.S07.653.