Abstract

The purpose of this article is to investigate the Northern Ireland tourism industry with a special focus on Dark (Troubles) Tourism. The method is two surveys one of Northern Ireland residents and one of potential tourists resident overseas, a focus group and interviews with tour-guides and a local MP. Findings suggest widespread support for Troubles Tourism from both residents and potential tourists and a supportive attitude from our interviewees. The two sides to the conflict are now working side-by-side in this new form of tourism, but it is important that each side tell only its ‘own’ story. from its own perspective, and does not speak for others. We conclude that, not over-commercialized, Troubles Tourism can educate people as well as being a source of fascination.

Introduction and historical background

General introduction

The primary aim of this article is to study the tourism industry in Northern Ireland and the attitudes of both residents and tourists towards Troubles Tourism. We view Troubles Tourism as a subset of both h and Dark Tourism, as defined and studied by Lennon and Foley (Citation2000). An early definition of Dark Tourism, specified by John Lennon and Malcolm Foley, regards Dark Tourism to be ‘the representation of inhuman acts, and how these are interpreted for visitors’. In a more recent publication, Kevin Fox Gotham defines Dark Tourism as ‘the circulation of people to places characterized by distress, atrocity, or sadness and pain’ (The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Sociology, 2007). Lennon (Citation2017) pointed out that ‘In these locations, such tourist attractions become key physical sites of commemoration, history and record. They provide the visitor with a narrative which may well be positioned, augmented and structured to engage, entertain or discourage further inquiry’. What is interesting and important to note in the present case is that tourists are presented with two narratives, one from the Loyalist perspective and one from the Republican perspective, but, in most cases, protagonists only present the story from their own perspective. Our secondary aim here is to recognize issues facing the tourism industry within Northern Ireland. We hope that, once we have identified these relevant issues, we (and other authors) can offer viable solutions and recommendations. We conclude this section with a summary of recent Northern Ireland history, commencing with ‘the Troubles’, of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and ending with the Good Friday Agreement.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland (hereafter NI) is one of the four constituent countries of the United Kingdom (officially, The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) and the only one not located on the island of Great Britain. It is the smallest country, in terms of both geography and population, and currently has a population of 1,885,444, equating to 3% of the United Kingdom’s population.

Tourism on the Island of Ireland

Tourism Ireland, Fáilte Ireland, and Tourism Northern Ireland (hereafter TNI, formerly the Northern Ireland Tourist Board or NITB) are the three independent bodies that presently plan and promote tourism in Ireland. Tourism Ireland is responsible for the marketing of the Island of Ireland overseas as a holiday and business tourist destination. It was the framework of the Belfast Agreement of Good Friday which first established Tourism Ireland as one of the six areas of co-operation in 1998. The remit of Tourism Ireland is to expand tourism to the Island of Ireland and to support NI to realize its nascent tourism potential (Tourism Ireland, Citation2018). It is responsible for promoting the island to visitors from 23 countries, including Great Britain, and reaches 800 million people globally (Tourism Ireland, Citation2018). Tourism Ireland works closely with TNI and Fáilte Ireland, but falls under the auspices of the North/South Ministerial Council, through the Department for the Economy in the North (hereafter NI) and the Department for Transport, Tourism and Sport in the South (hereafter ROI).

Tourism in Northern Ireland

Although Tourism Ireland manages overseas tourism in NI, on an all-Ireland basis, Tourism Northern Ireland (TNI), handles domestic tourism. Tourism Northern Ireland is a non-departmental public body of the Department for the Economy and is in charge of the development of tourism and the marketing of NI as a tourist destination to domestic tourists, from within NI, and to visitors from the ROI (NITB, Citation2019).Footnote1

Tourism remains vitally important for both NI and the ROI. It has obvious links to related industries, such as hospitality and transport, and has an important multiplier effect when tourist dollars are spent within a given area. Urry (Citation2002, p. 106) writes that tourism has a high multiplier compared to many other forms of expenditure, and UK studies (e.g. Williams & Shaw, Citation1988, p. 88) show that about half the tourism expenditure remains in the local area. However, it is difficult to assess the impact of any given project, and questions remain about the precise definition of a tourist and how big a local area can be.

According to the NISRA (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency)’s Annual Tourism Summer 2019 (the last post-Covid year), NI had 5.3 million overnight trips with a total estimated expenditure of £1 billion (NISRA, Citation2020) (equivalent to €1.8185 billion at 31 December 2019’s exchange rate). External visitors had 3.0 million overnight trips in 2019 and spent £731 million (NISRA, Citation2020). There were 2.4 million hotel rooms sold, which indicates an occupancy rate of 67% (NISRA, Citation2020).

If we compare NI with European countries with similar populations (Slovenia, Latvia, Estonia, Cyprus, and Luxembourg), NI still underperforms, reflecting its remote location geographically and the competition offered by England, Scotland, Wales, and the ROI. For example, nights in tourist accommodation (in brackets: inbound tourist spending) are: Slovenia 12.5 m. (€2,947 m.); Latvia 5.0 m. (€1,030 m.); Estonia 6.5 m. (€1,675 m.); Cyprus 16.8 m. (n/a); and Luxembourg 2.9 m. (n/a) (Eurostat, Citation2019). Only Latvia and Estonia are similar to NI in terms of money generated, while only Luxembourg is similar for nights in hotels/tourist accommodation. These are either geographically remote and/or countries with no significant interest for tourists. Latvia and Estonia seem to have more overnight visitors, but less spend per visitor, than NI, which is not unexpected. Tourism gross value-added (in brackets: tourist ratio) in 2019 was €1,463 m. for Slovenia (3.6%); €893 m. for Latvia (3.0%); and Estonia €845 m (3.8%) (Eurostat, Citation2019) This shows that Estonia has marginally higher domestic supply, but Latvia has marginally higher tourist value-added. These are probably realistic competitor countries, from a NI perspective, whereas Slovenia would appear to be in a different league altogether in terms of ability to attract tourist numbers and spending.

History: A dark past – the Troubles

At the same time that Westminster deployed the Army onto the streets of Belfast and Derry, a new wave of paramilitary groups began to emerge. From the Roman Catholic/Republican community, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) had split by the close of the 1960s. The IRA separated into the Official IRA, the less violent, more Marxist branch with older members, and the Provisional IRA, the younger generation of recruits, adopting an explicit aim of forced British withdrawal. The tools of their strategy were ‘bombs and bullets intended to destroy and kill’. In the Protestant/Loyalist community, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) re-emerged in 1966 as a response to the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association’s (NICRA) civil-rights movement. The UVF longed for the former times, believing that securing absolute Loyalist control was the only proper pathway forward for NI. The Ulster Defense Association (UDA) was a new association, formed in order to safeguard Loyalist areas from Republican attacks. The presence and acceptance of paramilitary organizations, against the backdrop of violence, signified a new dawn for NI. Cavanagh (1997) found that ‘levels of republican violence are most affected by organized and unorganized state repression, while loyalist violence is most affected by republican violence and activated when loyalists feel threatened’.

History: A dark past – Bloody Sunday

On Sunday, 30 January 1972, the NICRA organized a peaceful anti-internment march in Derry. British and Northern Irish authorities had enacted internment-without-trial some five months before as a response to an increased paramilitary threat in the province. The authorities interned 452 men in the first sweep of Operation Demetrius. However, most people now view Operation Demetrius as an abysmal failure. The poor intelligence surrounding the operation led to many innocent Republicans being arrested. ‘The IRA had known about it for some time and as a result virtually every senior IRA man was billeted away from home’. Internment backfired – instead of quashing the paramilitary threat, it led to a rise in support for both IRA branches. Furthermore, violence increased, ‘in the two years leading up to internment 66 people were murdered, while in the first 17 months after internment 610 were murdered’ (Dixon & O’Kane, Citation2011). Between ten to fifteen thousand men, women and children attended that peaceful anti-internment march in Derry, on that blue-skied Sunday in January 1972. Witnesses (Ziff, Citation1998) described the atmosphere as ‘carnival’. Then the British army opened fire on the crowd. Thirteen civilians were shot and injured, a further thirteen were shot and killed on the spot, and another one later died in hospital from his injuries. Bloody Sunday represented the culmination of a process of radicalization of the minority (McLoughlin, Citation2006). This effectively led to a move of Republicans away from the peaceful NICRA towards the much less peaceful IRA. Thus, many described Bloody Sunday as a ‘pleasing trauma’ for the IRA’s cause (Baumann, Citation2009). After Bloody Sunday, Westminster took control of Northern Ireland, hoping to increase stability in the North. However, 1972 still went down as the bloodiest year of the Troubles. For the rest of the 1970s, and into the 1980s, successive Westminster governments attempted to tame the creature that was Northern Ireland, but to no avail.

History: A dark past – the hunger strikes

During the height of the Troubles, Westminster imprisoned paramilitary prisoners affiliated with the Provisional IRA in Long Kesh; they viewed themselves not as prisoners, but as freedom fighters for the Republicans. Their goal was full political union with the South. In 1976, Westminster had abolished the special category status for anyone found guilty of terrorist crimes. By September of that year, many prisoners had started a ‘blanket protest’ – the refusal to wear the prison uniform. The blanket protest evolved into the ‘slop out’ protest, where prisoners tipped the contents of their chamber pots into the prison hallway, and, later, the ‘dirty protest’, when prisoners smeared their own excrement over the walls of their cells. At the core of these protests was the desire for Westminster to reinstate special category status. Despite these protests, the status of the prisoners went unchanged. In addition, by the dawn of the 1980s, a hunger strike had started within the prison. After 57 days, strikers called off the strike due to the false belief that Westminster and its adversaries had reached an agreement. Bobby Sands led the new hunger strike, which commenced on 1 March 1981. The constituency of Fermanagh South Tyrone then elected Sands to the Westminster Parliament. Sands died on 5 May 1981, 66 days into his hunger strike (Scull, Citation2016). The Westminster government granted no concessions until the strike-leaders called off the strike in October 1981.

Because of the hunger strikes, the Provisional IRA witnessed a further episode of ‘pleasing trauma’ and support for the Provisional IRA increased. Furthermore, the political wing of the Provisional IRA, Sinn Fein, noted carefully the success of Bobby Sands’ electoral victory and so they adopted the Armalite-and-ballot-box strategy, the idea of standing in elections while persisting in support for violence. Importantly, Sinn Fein proved, with the election of Bobby Sands, that it had a mandate. This fact sent shockwaves through the establishments of both London and Dublin.

History: New beginning? The peace process

Against the backdrop of Sinn Fein’s armalite-and-ballot-box strategy, the governments in London and Dublin signed the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985. In simple terms, the Treaty vowed to end the Troubles. Importantly, the Agreement recognized that ‘an Irish dimension and an agreed devolution are necessary to complete the reform of Northern Ireland’ (O’Leary, Citation1987, p. 5). Loyalists, feeling betrayed by the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, believed that the Agreement actually weakened NI’s union with Britain. According to McKittrick and McVea (Citation2012, p. 8), ‘Loyalists saw the agreement as a victory for constitutional nationalism, and constitutional nationalism agreed with them’. Loyalists were particularly bitter about the ROI having a role in the governance of NI and were fearful that this was one more step towards a United Ireland. The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) organized a campaign focused on dismantling the Treaty. Loyalists generated further support by encouraging Unionist MPs to resign from Westminster, creating civil disobedience, and organizing mass rallies. The outcome of the Treaty was not the end of the Troubles, nor did it reduce the incidents of political violence in the province. Furthermore, Loyalists halted their efforts to destroy the campaign, as they began to open talks with Westminster minsters less than two years after the agreement, in September 1987. Nonetheless, the actions of both Dublin and London in 1985 were arguably the first faltering steps towards the peace process. Both governments recognized that only they, acting collectively, could and would solve the NI issue.

The Downing Street Declaration 1993 argued for the right of people in Ireland to self-determination, and that a United Ireland would only come about if there were a majority in NI who supported such a move. The Declaration signalled London and Dublin’s move towards a policy of inclusion – enticing the IRA away from violence by bringing members of Sinn Fein to the political table, with the hope that it would have a domino effect on Loyalist paramilitary groups. Unlike the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985, both the British Prime Minister John Major and the Irish Taoisech Albert Reynolds focused on not isolating the Loyalist community. Politicians in both countries recognized that, if NI was to achieve peace, both Protestant and Roman Catholic communities needed to be fully onboard; all factions within both communities needed to feel included. Because of the Declaration, the Provisional IRA announced a ceasefire on 31 August 1994. The armed struggle of the IRA, which had been in place since the early 1970s, was over, on the condition that Sinn Fein would be included in future political talks. The world welcomed the ceasefire. On 13 October 1994, Loyalist paramilitaries announced their own ceasefire. The road to peace was underway, and, in the following year, both governments published a framework for the peace process. However, talks between the British government and Republicans failed to come to fruition. The Provisional IRA returned to violence by orchestrating the Canary Wharf bombing in 1996. It appeared that all had been lost.

The renewal of the Provisional IRA’s ceasefire in July 1997 allowed Sinn Fein to enter into political talks that September. After multi-party talks, and numerous walkouts, the relevant negotiators concluded the Good Friday Agreement on 10 April 1998. The Agreement established a framework and created three strands dedicated to formally building a trilateral relationship between the communities within NI, the relations with NI and the ROI, and NI and Great Britain. Strand 1 laid out the details of devolution, a new 108-member power-sharing assembly, and the use of proportional representation. This was seen as being ‘light-years’ away from the old Stormont regime, due to the fact that parallel consent was essential for all key decisions. This ensured that no one community could dominate the other (Ahern, Citation1998). Strand 2 dealt with North-South institutions, formally structuring NI’s relations with the ROI. Strand 3 encouraged the positive accord in the East-West institutions, Westminster, and NI. Alongside the formation of these institutions, the Agreement also secured the release of all political prisoners jailed during the Troubles. The deal’s powerbrokers asked paramilitary groups on both sides to lay down their weapons; this was in order to allow peace to thrive in the province. Furthermore, the ROI agreed to alter the 1937 Irish Constitution, whereby the Republic modified its constitutional and territorial claims to NI. The 1998 Agreement focused on the NI people’s right to self-determination – to identify themselves as either Irish, British or both. On 22 May 1998, authorities organized simultaneous referendums on both sides of the border. In the ROI, 94% of votes supported the amendments to the Irish Constitution (19th Amendment). Crucially, the people of NI also voted to support the Good Friday Agreement.

Research questions

In order to achieve the study’s aims, we attempt to answer the following four research questions: (1) what are the current limitations of the Northern Ireland tourist industry? (2) What are potential visitors’ views towards Northern Ireland as a destination, including their opinions about visiting Troubles Tourism sites? And, crucially: (3) is it time for Northern Ireland to accept its past and embrace Troubles Tourism?

Literature review

Introduction

This literature review will identify the background literature surrounding tourism in NI and similar tourism literature which can be applied to NI in order to gain a better understanding in relation to the aims and questions set out in section one. We will explore, in order, emerging-markets tourism, with a specific focus on film-induced tourism (as an example of non-traditional tourism); followed by destination image and perception; Dark Tourism; and walking and taxi tours (in London and Belfast). Lastly, we look at two approaches to Troubles Tourism (a subset of Dark Tourism) – TNI approach and the Stormont (devolved parliament) approach.

Emerging-markets: Film induced tourism

Authors of previous studies have proposed various useful definitions of this type of tourism: Movie Induced Tourism, Media Induced Tourism, Cinematic Tourism but perhaps most common, logical and straightforward is ‘Film Induced Tourism’ (Macionis, Citation2004). Busby and Klug (Citation2001, p. 316) define Film Inducted Tourism as ‘tourist visits to a destination or attraction as a result of the destination [being] featured on the cinema screen, video or television’. Morgan and Pritchard (Citation1998) describe placing a destination in a film as the ultimate in tourist product placement; while Iwashita (Citation2003) claims that film, television and literature can influence the travel preferences and destination choices of tourists.

The scope for advantage that The Lord of the Rings offered to New Zealand is in many ways unprecedented (O’Connor et al., Citation2008). The Tourist Board of New Zealand (TNZ) looked at the first Lord of the Rings film as equivalent to a promotional tool, and subsequently worked out what it would cost to access this exposure commercially. ‘Based on attendances and making a range of assumptions, they estimated the exposure was worth over $41 m US’ (New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, Citation2002). They acknowledged tourism promotion as a vital opportunity created by the film, increasing the profile and perception of New Zealand as a tourist destination (O’Connor et al., Citation2008). Tooke and Baker (Citation1996) discuss films as recurring events, with DVD and video launches, television-airings, and reruns providing opportunities for frequent viewing. This frequent viewing strengthens the association between a film and its location (Tooke & Baker, Citation1996); this is probably more relevant today than at the time of that article with the introduction of online streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon.

This type of tourism can give exposure to areas and destinations which might otherwise struggle to attract tourists. France, for instance, uses the film Chocolat to promote Burgandy and Charlotte Grey to promote the Aveyron and Lot Valley (Mintel, Citation2003, p. 8). One other major economic benefit of Film Induced Tourism is that ‘viewing film locations can often be an all-year all-weather attraction, thus alleviating problems of seasonality’ (Beeton, Citation2001, cited in Hudson & Ritchie, Citation2006, p. 387). Interestingly, Riley, Baker, and Van Doren (Citation1998) found that, although the peak interest comes after the initial release of a film, ‘a 54% increase in visitation was evident at least 5 years later in the 13 films studies and images are often retained for a long time’ (Riley, Baker, & Van Doren, Citation1998, cited in Hudson & Ritchie, Citation2006, p. 387). We could use these long-term effects to explain the successes of destinations that have redeveloped locations to make the connections between them and a film more obvious, and which have boosted tourism, even when the film is not new (Grihault, Citation2003). A good example of this would be the Titanic Belfast. NI has been the location of many film productions that could assist with the (re)branding of this destination, through developing new images to attract international tourists (O’Connor et al., Citation2008). TNI has used this approach for several years, marketing NI as the setting for local C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia. Therefore, tourist boards should never ignore the opportunities which this type of tourism can offer.

Destination image and perception

Gould and Skinner (Citation2007) understand place branding as a method for promoting a positive image based on an agreed single national identity. They liken the nation-branding strategy of NI to the metaphorical Janus whose nature symbolizes change and transition, a progression from past to future (Amujo & Otubanjo, Citation2012, p. 90). NI has had to adopt a double-edged branding strategy, promoting the ‘Irishness’ of the country to Ireland-friendly markets, on the one hand, while, on the other, promoting its ‘Britishness’ to British-friendly markets. To cite Amujo and Otubanjo (Citation2012, p. 91) about national rebranding:

It is challenging to rebrand a nation in post conflict or atrocity in the absence of an agreed single national identity, and so nation rebranding in post political conflict, genocide or atrocity should be constructively undertaken with high sense of responsibility to counteract or reformulate the myths, prejudices and stereotypes that result from negative discourse, narratives and ill-conceived judgments about the country.

Dark tourism

Several commentators view pilgrimage as one of the earliest forms of tourism (Vellas & Bécherel, Citation1999). Pilgrimages are often (but not always) associated with the death of individuals or groups, mainly in circumstances that are associated with the violent and untimely. Visiting sites connected in some way to death (e.g. murder-sites, death-sites, battlefields, cemeteries, mausoleums, churchyards, the former homes of now dead celebrities) is a significant part of tourist experience in many societies (Lennon & Foley, Citation2000). Recently, discussion has taken place in relation to the degree of ‘darkness’ of a site (Strange & Kempa, Citation2003) with Auschwitz concentration camp being seen as ‘darker’ than the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC because it was the actual site of death (Jendreas, Citation2023, pp. 17–18). In commenting upon the paradoxes and issues associated with promoting Dark Tourism and visiting its sites, Lennon (Citation2017) comments that: ‘If such dark heritage is not commemorated it may be seen, in whole or part, as some form of complicit suppression of history. Yet, if such sites are interpreted and commemorated then the content and approach may also be seen as compromised or selective in their narratives’. In the case of the Troubles, both sides of the conflict must present only the story from their own perspective, and it must avoid overt and crass commercialization. There is the real danger that such sites may inspire radicalism, but there are plenty of other avenues for radicalization, such as singing sectarian songs in pubs. Clark (Citation2014) has questioned the appropriateness of displaying for tourist purposes sites of death and misery. Furthermore, Chang (Citation2017) explains that the sites must be treated with respect and sensitivity and that tourist industry workers, tourists and residents should be aware of the moral and social aspects involved in visiting and promoting them. But visits to Troubles Tourism sites may create empathy for the victims of the conflict (Batson, Citation1990; Fennell, Citation2006, p. 41). Expanding upon this point, Kuznik (Citation2018, pp. 4077–4087, cited in Jendreas, Citation2023, pp. 20–21) lists seven motives for dark tourism as follows: empathy, horror, education, nostalgia, remembrance, and survivor’s guilt.

Walking and taxi tours

In and around London’s East End there are guided walking tours that take tourists to visit the nineteenth century murder-sites of five local working-class women: Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catharine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly (Rubenhold, Citation2019). These murders, at the hands of the media creation known as Jack the Ripper (JTR), in the late summer and autumn of 1888, are, by far, the most popular guided walking tours in the capital with estimates of up to 100,000 people consuming them per year. One must consider the question of why these tours are so popular. Walking is the prime tool for getting to know the mood of the city, its mythologies, for getting in touch with its ghosts, hidden histories, and for making new linkages between pasts and presents (Hansen & Wilbert, Citation2006, p. 3).

Walking is a habituating spatio-temporal practice. It is ‘time in-between’ (Solnit, Citation2002); walking narrates and gives a continuity of and between sites and places unlike the sudden passenger arrival by car, coach or plane. As normative as it is liberating, walking – and marching (Bryan, Citation2000) – has long been associated with resistance, social protest (Gooch, Citation2008), and occupation (Katz, Citation1985). Walking creates equality and solidarity, critiques modernity and is therapeutic (Skinner, Citation2016, p. 26); this combined with the immersion of the tours is why they remain popular. The interest in the JTR murders also reflects nostalgia for a Lost London and a Lost Empire; and the tours highlight the contradictions existing 130 years ago between the City of London’s wealth and the East End’s shocking poverty.

Like London, Belfast has had its own share of death and despair as characterized by and in the media since the 1970s. When Glasgow’s two largest football clubs, Celtic and Rangers, play each other, they bring to life ancient religious and political allegiances as seen through the prism of the Belfast of the 1970s (Murray, Citation1984, Citation1988, Citation1998). Belfast today offers immersive walking tours in the west of the city, taking in the murals at the start of the Catholic Republican Falls Road, before walking through and learning about Republican history, often from former paramilitaries who themselves spent time in prison only to be released under the Good Friday Agreement. The guide then hands over to a Loyalist tour-guide operating at the crossover gate between the two territories (Skinner, Citation2016), before heading down the predominantly Protestant and Loyalist Shankhill Road. By taking a walking tour, and hearing the stories of the struggles first-hand, the tourists on these tours are having their imaginations shaped and dictated by the tour-guide and fabulist (Skinner, Citation2016).

Dark Tourism can be a factor for engaging local communities in tourism development, but, as it stands now, most local communities do not benefit because they lack appropriate tourism infrastructure, such as hotels and restaurants (Causevic & Lynch, Citation2011). Phoenix Tourism suggests that, like a bird rising from the ashes, tourism can help conflict areas by assisting in the process of social reconciliation and urban regeneration through building infrastructure, creating a sense of pride, and helping small businesses (Murphy 2010).

Taxi tours delivered by ‘Black Hacks’ are the most popular form of political tour in Belfast. Similar to the route taken by the walking tours, these taxi tours tell a similar story, Taxi companies operate from various points of view. However, they mostly aim for neutrality in storytelling. There is an argument, however, that, unlike the walking tours, these tour operators, although from Belfast, are often from outside the local community and provide only sanitized versions of the conflict. The suggestion is that these outside tour operators exploit local communities, which receive little or no economic benefit from the tours (Causevic & Lynch, Citation2011). Therefore, to realize fully the benefits of Phoenix Tourism, local communities must be involved in the tourism industry – the tourist gaze must not simply treat local people as objects for consumption (Urry, Citation2002).

Tourism strategy in Northern Ireland

TNI/NITB approach

NI’s tourism promoters have utilized three approaches as follows: (1) ignore the Troubles completely; (2) highlight that NI is not as bad as people think; and (3) acknowledge the curiosity factor, or that some tourists are attracted to NI because of the conflict (Rolston, Citation1995, p. 37). TNI has historically adopted the first approach. The main tourism strategy of TNI, at least as until 1999, was to depoliticize culture so that it became an easily-consumable bland commodity (Thompson, Citation1999, p. 54). Alan Clarke, former chief executive of TNI, argued that while the Troubles are the reason why many people have heard of NI, they are not necessarily the reason why people want to visit (Clarke, Citation2007). By contrast, a 2001 Belfast City Council report claimed that 43 percent of tourists came to Belfast because of curiosity about the Troubles (Causevic & Lynch, Citation2011).

In recent days, TNI appears to be warming to the idea of Troubles Tourism. Jan Nugent of TNI states that she was not keen when the black cabs started because she thought that people might perceive them as Terror Tourism. By contrast, she now sees these tours as edgy things for tourists to do, and it has given communities a real motivation to spruce up their murals and local communities (NI Bauru, Citation2007, p. 8).

Stormont approach

In 2008, two members of Sein Fein, Paul Maskey and Willie Clarke, stated in the House: ‘That this Assembly calls on the Minister of Enterprise, Trade and Investment to bring forward plans to develop tourist infrastructure, particularly in areas of social need and to recognise the significant potential of political tourism’ (Hansard, Citation2008). Maskey and Clarke were looking to promote Troubles Tourism predominantly in Maskey’s own area of West Belfast, which, although overwhelmingly Irish Republican; also includes the Loyalist Shankhill Road. This statement encountered fierce opposition in the Assembly from Unionist party members.

People should resist the concept of Political (Troubles) Tourism in Northern Ireland, maintained UUP MLA Leslie Cree (Hansard, Citation2008). Cree continued by stating that NI was not ready for Political Tourism as the country was too close to the subject matter (Skinner, Citation2016). He closed by saying, ‘It can be regarded as inappropriate to make a pilgrimage to places individuals lost their lives, especially if the visits are made in order to glorify the murders’ (Hansard, Citation2008). A statement followed from the late David McClarty, a UUP politician who later became an Independent Unionist:

[t]he practice either brings rejuvenation to and regeneration to deprived and under supported parts of Northern Ireland, predominantly Belfast, or, to paraphrase, it is an unsafe and uncomfortable experience for visitors, freezes local communities in the past, glorifies acts of terrorism, disrespects victims and their families and paints Northern Ireland in a negative light (Hansard, Citation2008).

Research method

Introduction

This section will provide details on the choices made by the authors as to how to address the issues raised by the research questions. This will detail research design and the methods of data collection for analysis. This will also include ethical considerations, which were to be followed as set out by the University Ethics Committee. The study uses a mixed-methods approach and features two surveys (one for NI residents and one for non-residents) as well as interview and focus group data. The first step was to apply for and receive University Ethics Committee clearance, and this was done before the data collection commenced.

Research design

Questionnaire 1 – Northern Ireland residents

A survey was created using Qualtrics. We then distributed the survey in a variety of ways. Firstly, we sent an electronic link to participants who were known to the researchers and they further distributed the link, at the request of the researchers, to colleagues, acquaintances, etc. We also distributed the electronic link online on Reddit, on a closed group called r/northernireland in which residents were able to respond. The GPS data from this also identified the location where the subject was responding from to ensure the integrity of the findings. The second method was to use a QR code; the researchers asked participants to hold their mobile phone camera over the QR code, which then brought up the survey on their mobile phones in order for them to participate. Finally, in order not to exclude any particular demographic (e.g. those less computer-literate), a paper survey was handed to participants which was then handed back to the researchers before the results were input manually into the Qualtrics research tool.

The second and third methods required one of the researchers to travel to NI and conduct sampling in person; this researcher approached respondents and asked them to take part in the study. The survey was successful and returned a sample size of 329. Ten samples were rejected as respondents stated that they were not from NI. They were however able to participate in Questionnaire 2.

The survey first asked four questions to gain background information: age, gender, county of residence, and background. Background was important to distinguish later whether there was a difference in results between Republican and Loyalist individuals.

While there are validity issues due to the first researcher using his own social media networks, and this is a limitation of the study, this is partly overcome by handing out paper surveys and using the Reddit group that was independent of friends networks. The fact that percentages responding very closely mirrored Census data, in terms of both county and Republican or Loyalist identification should be reassuring to readers.

Questionnaire 2 – perceptions of Northern Ireland

We created a second survey also using Qualtrics. We created this survey with the intention of respondents being from outside NI to gain an insight into the perceptions of potential tourists. We distributed this survey in a number of ways. Firstly, the researchers sent it to colleagues and associates overseas and they then forwarded it to potential tourists.

Secondly, and similar to questionnaire 1, we distributed the survey online. This was again on Reddit through the subfeeds r/solotravel, r/travel and r/samplesize. This questionnaire returned 176 responses.

Semi-structured interviews

We conducted three semi-structured interviews in person in NI in 2018–19 (i.e. pre-Covid lockdowns). The first interviewee was Sinn Fein MP Paul Maskey who, at the interview date, was an abstentionist Member of Parliament for West Belfast. Prior to his appointment, Mr Maskey was a Member of the Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly for Belfast West. He has spent time as a councillor and as director of Fáilte Feirste Thiar (Welcome to West Belfast). Our 45-minute interview took place at Sinn Fein’s office in the Kennedy Centre just off the Falls Road.

The second interviewee was Mr Michael Culbert, a former IRA member, who was in prison during the Troubles. Mr Culbert is currently the Director of Coiste na n-iarchimí (Ex-Prisoners Committee), which is an organization designed to facilitate the reintegration of Republican ex-prisoners of the Troubles, many of whom now work as tour-guides. Our 35-minute interview took place at Coiste na n-iarchimí’s Falls Road office.

In order to present a balanced picture, it was important and necessary to have interviewees from both sides of NI’s historical divide. The third interviewee was Mr David Name, founder of Sandy Row tours, and a member of the Sandy Row Flute Band. David now operates the tours in Sandy Row from a Unionist/Loyalist perspective. Sandy Row was once famous for its ‘You are now entering Loyalist Sandy Row’ mural. However, in recent years, the community replaced it with a mural of King William, which commemorates 1690’s Battle of the Boyne. The first-mentioned researcher took a tour with David around Sandy Row before we embarked upon a 20-minute interview at the Sandy Row Orange Hall.

Focus group

The first-mentioned researcher held a focus group with tourists who have travelled to NI, with the inclusion of one NI resident currently living in Glasgow, to gain an insight into their experiences. The focus group took place in Glasgow and lasted for 60-minutes. It was important that these tourists represented a mix of nationalities. This researcher knew all participants prior to the focus group. Therefore, it was a convenience sample. We agree that this was not a random sample and hence we do not make generalizations from the sample results. However, we maintain that everyone’s experiences and opinions are important ().

Table 1. Focus group participants’ information.

Negotiating access

We negotiated access to interviewees via email and telephone calls. We sent several emails to various people including Unionist MPs who all declined an interview. They cited various reasons for refusal including the workload the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) had with Brexit and their opposition to our topic. We also contacted TNI but they stipulated that an interview was not something that they were looking to pursue, as they did not have anyone who was a Dark Tourism specialist. The successful interviews were arranged quite easily. However, after an emailed reply, a formal request had to be sent to Coiste na n-iarchimí in order to be approved. After this step was completed, they were happy to proceed.

Ethical issues

We made an ethical application to our University Ethics Committee in mid-2018 before collecting any primary data. This application detailed the chosen sample and provided details of interviewees. With regard to interviews, we also stated that we would allow interviewees to decide on the meeting times and places, provided that they were safe for the researcher. The questionnaire had a statement at the start stating that commencement and completion of the questionnaire would count as consent. For offline copies, the same statement appeared.

At interviews, the researcher gave a participant information sheet and a participant consent form to each interviewee. The researcher also stated that he would record and password-protect all interviews. He later sent each interviewee a transcript of the interview to ensure that they approved. He gave interviewees the opportunity to conduct the interview anonymously under a pseudonym. However, all participants chose to participate in their interview using their real names. This was also true for every focus group participant

Pilot testing

Al survey and interview questions were discussed at length between the two authors and were also pilot-tested on a small sample in the interests of ensuring validity and reliability.

Variables of interest

In terms of the quantitative arts of the study, the key dependent variables are essentially a variation on support for and interest in Troubles Tourism. The independent variables are age, gender, county-of-residence (for residents), region of the world (for non-residents), and identification as being part of Loyalist or Republican communities. Crosstab analysis allows for some analysis of the effects of independent variables on the dependent variable.

Results and findings part I

Introduction

We present and discuss the Results in two sections. Section 5 will discuss perceptions of NI as a destination and includes primary data from the focus group and Questionnaire 2 (for tourists). By contrast, Section 6 will feature primary data, plus interpretation, from the three interviews and Questionnaire 1 (for NI residents) ().

Table 2. Q1: Have you ever considered visiting Northern Ireland?.

Findings – Questionnaire 2 and focus group

The survey started by asking whether the respondent had ever considered visiting NI. Over half of the 176 respondents responded positively with a Yes reply. As the focus group members had already visited NI, it was important to understand their main reasons for visiting:

My main reason was Game of Thrones too, although I was really keen to see the murals. Coming all that way I think I would have left pretty annoyed if I hadn’t got a chance to see them – Catlin (Canada).

I was keen to see the Murals and do some of the Dark Tourism stuff. I’ve done quite a lot of reading on The Troubles etc. and it was definitely my main motivation for going to Belfast – Daniel (Great Britain).

The first time I went is when I came over to study from New Zealand and just fancied visiting Ireland, my grandparents were from Armagh so I was keen to visit there. With the other stuff, I didn’t bother with Game of Thrones but I did do a walking tour of the Falls Road – K. Harron (New Zealand).

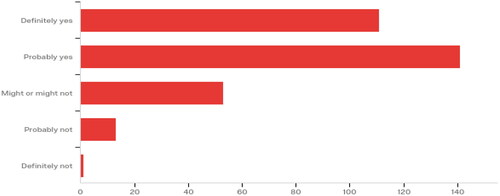

Table 3. Q5: Would you be interested in touring the sights where the (Troubles) conflict took place?.

In Question five (results for questions two to four are not reported here), we asked visitors whether they would be interested in touring the sites where the Troubles took place. This question divided the respondents with four of the five options (other than Definitely Not) being popular. Those from Great Britain and ROI responded very positively, with all ROI respondents stating that they would like to visit these sites. Mainland Europe also responded positively, with 64.71% expressing that they would like to visit these sites. A smaller percentage of North Americans (58.66%) also held this view. The number of people responding ‘Might or Might Not’ was slightly higher for North Americans and Europeans. However, most interesting is the numbers who showed no desire to visit – 22.66% of North Americans gave a negative answer compared to 13.72% of Europeans. The results from this are quite similar to the media perception question (not reported here) and a similar argument can be presented, i.e. those further away, North America, are less likely to have seen the Troubles in the media and are, therefore, less likely to be inclined to this aspect.

We asked the focus group members their opinions on the murals and the conflict sights being included in a tour. The results were all positive, as follows:

I thought it was brilliant, the murals really conveyed the history of those involved in the conflict and some were really, really well painted. The tour guide I had was great too, really informative, and spoke about his personal experiences. I would recommend it to anyone visiting Belfast or Northern Ireland for that matter – Daniel (Great Britain).

Like I said before, I couldn’t believe the size of the peace-wall, but the history side of the tour was great to learn about, parts were really sad too but I think it’s important people don’t forget their history. I felt it was really authentic too, there was no gift-shops, no selling, just total storytelling; it was just quite raw and hard-hitting – Danielle (Canada).

For me it’s really quite personal. My parents lived in Belfast and studied [there] during the Troubles and they always spoke of how difficult it was. I’m quite glad we have this, as a Republican, I don’t think I’d ever have went to these areas and heard the Loyalist story, but it’s important we learn from the past. The murals make me really proud of where I come from and where we are now – E.R. McCrory (NI Resident).

Independent variables

The researchers were unable to secure a perfect balance between male and female respondents with 113 (64.57%) respondents being men and 62 (35.43%) being women. Age is heavily weighted towards Under-44s with the two most common demographics being 18–24 (62 people, 35.23%) and 25–34 (59 people, 33.52%).

Concerning place of residence, North America had the highest rate of response (75 people, 42.61%); followed by Europe (51 people, 28.98%); Great Britain (26 people, 14.77%); and ROI (15 people, 8.52%). The researchers found it particularly difficult to access respondents from South America (1), Asia, (3) Africa (1), and Oceania (2). Given that both researchers were Scotland-based during the data-collection period, the high percentage of North American respondents (42.61%) is reassuring as these are unlikely to be part of either author’s social media friendship networks.

Results and findings part II

Introduction

The aim of this section is to analyse the results from Questionnaire 1 for residents of NI. This section will also include analysis of the three interviews conducted with those involved in the tourism industry.

Independent variables

The survey was able to provide a diverse sample, reaching people from all age-categories. The largest response group was 25–34s (117 people out of 319, 36.68%), which was expected. It is fundamental when conducting a survey that the researchers understands the age-groups being surveyed and it was apparent that the majority was in the lower two age-brackets. Gender was relevant to investigate whether there was a difference in responses between men and women and to understand whether the views they held on the matter were different. Three hundred and eighteen out of a possible 319 answered their gender and the figures were 216 men (67.92%) and 102 women (32.08%).

The Background question was important to distinguish whether the attitudes that existed with regard to Troubles Tourism were different between the two communities within NI. Drawing upon the official Census, options available were ‘Republican’, ‘Loyalist’, and ‘Prefer not to say’. In the most recent Northern Ireland Census, conducted in 2011, 40.76% of the population nominated Republican, 41.56% nominated Loyalist, and 17.68% preferred not to say. Our sample was relatively close to these percentages, in all respects, with us reaching 138 Republicans (43.40%), 120 Loyalists (37.74%), and 60 Prefer not to says (18.87%). Therefore, our sample, while not random, is representative and unlikely to yield biased conclusions due to more or less Loyalists answering the questions as compared to the NI Loyalist percentage.

As expected, the highest number of respondents came from County Antrim (130 people, 40.75%); and the lowest from County Fermanagh (25 people, 7.84%). Other respondents were from Armagh (33 people, 10.34%), Derry/Londonderry 39 people (12.23%), Down (56 people, 17.55%), and Tyrone (36 people, 11.29%). This question again allowed the researchers to investigate using cross-tabs; it also gives an indication as to whether responses differed in the more rural areas of NI. The 2011 Census stated the population proportions of each county: Antrim 34.14%, Armagh 9.65%, Derry/Londonderry 13.64%, Down 29.36%, Fermanagh 3.38%, and Tyrone 9.83%, which are fairly close to those for our study. The similarity of our sample to the general population, in terms of county, suggests that our sample is representative and results will not be biased due to urban-versus-rural divide (, ).

Table 4. Q7: Do you think overseas tourists want to visit murals and take political tours?

Attitudes towards Troubles Tourism

The participants again responded positively to this question, and it appears that there was no real divide based on background or age. Republicans did, however, respond slightly more positively in higher numbers with ‘Definitely Yes’ gaining 63 responses versus the 30 ‘Definitely Yes’ from the Loyalist community. In contrast, the Loyalist community responded marginally higher in the ‘Probably Yes’ option of the survey. Overall, this question shows that both communities believe that overseas tourists will want to visit these murals and take political tours ().

Table 5. Q8: Should these types of tours (political) be promoted by the Northern Ireland Tourist Board?

Other than the Republican community responding again in slightly higher numbers in the ‘Definitely Yes’ category, there was no real community divide for this question. This was a surprise to the researchers as parliamentary records tell a different story.

There are several reasons why the results are different from expected. There was a ten-year gap between the year of the parliamentary debate and the year of our survey. Possibly the Loyalist community softened its approach to the issue over this past decade. However, in the opinion of the researchers, it is more likely that the constant tit-for-tat opposition in the devolved parliament is not representative of the views of the electorate.

When asked directly by the researcher, in our interview, Mr Maskey responded when asked about promoting Troubles Tourism:

I’m a great believer that you can always learn from the past, but learn and move on. Don’t go back to the past but learn and move on so you don’t make the same mistakes that happened over a historical period, so you’re asking me can the executive do more, and TNI, TNI, absolutely – Paul Maskey MP.

I think if you tried to sanitise the story it’s not fair, plus it’s not factual so I think if you have to tell the story you have to tell it where it’s known. That’s why I said earlier it wouldn’t be good for anyone from the Falls to tell the story of the Shankill, they’ll have a completely different story to tell and vice-versa. I think that’s very important to tell a proper story and you tell it from your heart because you lived through it, it’s much more organic, it’s true, it’s facts – Paul Maskey MP.

Image and social attitudes

Q9: What effect do these tours have on Northern Ireland’s image?

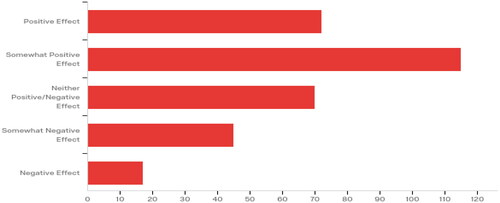

The response to how these tours affect Northern Ireland’s image produced a rather mixed result. Although mostly positive (141 people, 44.20%), a large percentage of respondents’ (91 people, 28.53%) believed it has no effect at all (, ).

Table 6. Q10: How do these tours affect society moving forwards?

This was perhaps the most important question in the survey. In reality, there would be no point in promoting Troubles Tourism if it did not have a positive effect on the host-community. Commentators emphasize the economic benefits but, in reality, they are less important than the social benefits that this type of tourism can bring. The question again showed no real disparity between the views of the two communities, and no differing in opinion between those who were older and experienced the conflict personally and those of the new generation. There is still some apprehension, as 19.44% responded negatively. However, over half (58.62%) responded in a positive way.

The first-mentioned researcher interviewed Michael Culbert, a former IRA political prisoner who now runs an ex prisoners’ organization, Coiste na n-Iarchimí, to help those who were involved in the conflict find work through tourism. When asked how this type of tourism has altered the relationship between himself and those of the Loyalist community he responded as follows:

It certainly has improved the relationship with us and the former UVF personnel. We do talks together we go to schools together, well, into schools to talk to students together. In order for young people to know the realities of what life was like, motivations for doing what was done, visions for the future and more or less explain to them how life is much, much better than it was, some people would contest that not a lot has changed, a lot hasn’t changed, but an awful lot has changed, particularly, and basically there’s nobody getting killed – Michael Culbert Coiste na n-Iarchimí.

We started an engagement process between ourselves, myself and the Shankhill tourism initiative. We started with Coiste Na l-archimí which is a Republican ex-prisoners’ organization, we went and met EPIC, which is a Loyalist ex-prisoners organization, and from that they end up doing tours, so you would have walking tours down West Belfast (Falls) which were primarily done by an ex-prisoner who would have handed over on the Shankhill side to a Loyalist ex-prisoner, so you had, I suppose, combatants who were involved in a fight against each other … are now working together and doing tours. They also work very closely together not only in tourism but on a wide range of different issues, social issues as well – Paul Maskey MP.

I actually think it’s amazing. I work a lot on the Falls Road and the Shankill and I could be walking out the office to get in my car and go somewhere or coming in from my car, and people will stop you; taxi-drivers will say oh by the way I’m from the Shankill but this tour group here are from Australia or Canada or America or wherever and you stop and have a moment or two conversation with them; people love that fact that they’re there and they’re seeing it, and they realise the drivers from the Shankill and they’re talking to a Sinner (Sinn Fein), you know what I mean, which is great. … I think tourism breaks down barriers, it breaks down social problems; it also breaks down that religious difference divide as well because when people are talking about their history and their story people appreciate it – Paul Maskey MP.

Conclusion

Conclusions and recommendations

Overall, we feel that, despite limitations in research design, the research data demonstrates conclusively that there is an interest in Dark Tourism both from residents and potential tourists. Locals want to show the sites, via tours and tour-guides, and incoming tourists mostly want to visit them, although Europeans and British seem more interested in these sites than do North Americans. Locals feel that is time to open up these sites, experiences, and stories to the tourist market, but the stories should remain authentic, whereby each side to the conflict discusses the conflict from its own perspective. Tour-guides and Paul Maskey MP believe that the tours bring people together, from both sides of the conflict, and tourists can develop and display empathy. There is also the conviction that the Troubles should never be repeated, and current tours in no way glorify the tragedy or are partisan. People want to tell their story and other people want to listen to them.

Throughout this research project, we observed a number of problems that affect the NI tourist industry. One of the largest is its geographical location, within the relatively remote Island of Ireland, combined with its constitutional status as part of the UK. As such, NI follows the tax laws of the UK and is at a disadvantage when compared to its southern neighbour. Higher rates of Air Passenger Duty (APD) and Value Added Tax (VAT) affect the tourism industry and can have a detrimental effect on the number of tourists coming north.

Potential visitors are looking towards NI favourably. The marketing campaign set out by Tourism Ireland and TNI is doing well to display the country to tourists internationally and domestically. The success of the Good Friday Agreement has allowed cross-border co-operation to grow and, in time, this should only further enhance the opportunities for NI. The remarkable transformation in tourist perceptions about Glasgow, once seen as bleak, violent, and depressing, but now viewed as a place of arts and culture (Urry, Citation2002, pp. 108–109), suggests that it is possible to be optimistic about Belfast.

Existing Troubles Tourism has brought the RC and Protestant communities closer together and broken down barriers, with former combatants now working side-by-side for the benefit of future generations. It is important that stakeholders allow this type of tourism to grow, but we hope that it does not become over-commodified.

Limitations

The main limitations are the lack of random sampling and the possibility of bias in that friendship networks on social media were in part used to distribute surveys, and that focus group participants were chosen by convenience sampling. As such, surveys are more heavily weighted towards men rather than women and younger respondents (under-44s). Thus, support for Troubles Tourism may be slightly overstated if it is generally opposed by older people. However, the percentages of residents of each county and Loyalist-versus-Republican, for our survey, arguably the two most important historic dividers in NI, mirror closely the population percentages. Another limitation is that Covd-19, and the government-imposed lockdowns, which began in the UK in March 2020, altered the picture significantly in the short-term. But, in the long-term, the issues raised here will continue to be important.

Suggestions for further research

There is little data available as to the actual economic contribution Troubles Tourism brings to NI other than visitor numbers. The authors believe that an in-depth study in this area would further enhance the argument that it is time to embrace Troubles Tourism. Researchers should also investigate the impact that Brexit is having on the NI tourist industry as part of full-length article studies. That topic remains beyond this article’s scope.

Ethics approval

The authors report that this project was approved by our University Ethics Committee.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Greg Ironside

Greg Ironside grew up in Fife, Scotland, and attended high school in Dunfermline. He graduated with 1st Class Honours in Accounting at the University of the West of Scotland, Paisley campus. His dissertation topic was on the prospects for Troubles Tourism in Northern Ireland. After finishing his degree, he secured a job with Accenture and now resides in Dublin.

Kieran James

Dr. Kieran James is a Senior Lecturer at School of Business & Creative Industries, University of the West of Scotland (Paisley campus). He researches on Fiji soccer history, Indonesian popular music and society, Singapore politics, sociology of religion, sport history, and sociology of sport. He recently published an article in Soccer & Society on race, ethnicity, and class issues in Fiji soccer, 1980–2015. He has also written two novels, Last Hong Kong Summer and The Greenock Murders.

Notes

1 Although the constitutional status of NI is as a constituent country of the UK, tourists from Great Britain (England, Scotland, and Wales) are classified as overseas tourists and not domestic.

References

- Ahern, B. (1998). The Good Friday Agreement: An overview. 22 FORDHAM INT’L L.J. 1196.

- Amujo, O. C., & Otubanjo, O. (2012). Leveraging rebranding of ‘unattractive’ nation brands to stimulate post-disaster tourism. Tourist Studies, 12(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797612444196

- Batson, C. D. (1990). How social an animal? The human capacity for caring. American Psychologist, 45(3), 336–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.3.336

- Baumann, M. (2009). Transforming conflict toward and away from violence: Bloody Sunday and the hunger strikes in Northern Ireland. Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict, 2(3), 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/17467580903440247

- Bauru, N. I. (2007). Tourism takes hold in Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland Bureau Newsbreak, 34(March 2007), 8.

- Beeton, S. (2001). Smiling for the camera: The influence of film audiences on a budget tourism destination. Tourism Culture & Communication, 3(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.3727/109830401108750661

- Bryan, D. (2000). Orange parades: The politics of ritual, tradition and control. Pluto.

- Busby, G., & Klug, J. (2001). Movie-induced tourism: The challenge of measurement and other issues. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 7(4), 316–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/135676670100700403

- Causevic, S., & Lynch, P. (2011). Phoenix tourism: Post-conflict tourism role. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 780–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.12.004

- Chang, L. H. (2017). Tourists’ perception of dark tourism and its impact on their emotional experience and geopolitical knowledge: A comparative study of local and non-local tourist. Journal of Tourism Research & Hospitality, 06(03), 169. https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-8807.1000169

- Clark, L. B. (2014). Ethical spaces: Ethics and propriety in trauma tourism. In B. Sion (Ed.), Death tourism: Disaster sites as recreational landscape (pp. 9–35). Seagull.

- Clarke, A. (2007). Tourismni.com [online]. Retrieved April 3, 2019, from https://tourismni.com/globalassets/grow-your-business/toolkits-and-resources/insights–best-practice/insights-culture-and-creative-vibe-practical-guide.pdf.

- Dixon, P., & O’Kane, E. (2011). Northern Ireland since 1969. Pearson.

- Eurostat. (2019). (Publications Office of the European Union.) Tourism satellite accounts in Europe 2019 [online]. Ec.europe.edu. Retrieved January 25, 2022, from: https://ec.europe.eu.

- Fennell, D. A. (2006). Tourism ethics. Channel View Publications.

- Gooch, P. (2008). Feet following hooves. In T. Ingold, & J. Vergunst (Eds.), Ways of walking: Ethnography and practice on foot (pp. 67–80). Ashgate.

- Gould, M., & Skinner, H. (2007). Branding on ambiguity? Place branding without a national Identity: Marketing Northern Ireland as a post-conflict society in the USA. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 3(1), 100–113. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.6000051

- Grihault, N. (2003). Film tourism: The global picture. Travel & Tourism Analyst, 5, 1–22.

- Hansard. (2008, February 19). Tourism. In Northern Ireland Assembly Private Member’s Business. Retrieved April 2, 2019, from: http://archive.niassembly.gov.uk/record/reports2007/080219.htm.

- Hansen, R., & Wilbert, C. (2006). Setting the crime scene: Aspects of performance in Jack the Ripper guided tourist walks. Merge Magazine: Sound Thought Image, 17(1), 1–14.

- Hudson, S., & Ritchie, J. (2006). Promoting destinations via film tourism: An empirical identification of supporting marketing initiatives. Journal of Travel Research, 44(4), 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287506286720

- Iwashita, C. (2003). Media construction of Britain as a destination for Japanese tourists: Social constructionism and tourism. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/146735840300400406

- Jendreas, K. (2023). Dark tourism in Auschwitz: Understanding the tourist experience, ethics and perspectives (Unpublished Honours dissertation). University of the West of Scotland.

- Katz, S. (1985). The Israeli teacher-guide: The emergence and perpetuation. Annals of Tourism Research, 12(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(85)90039-8

- Kuznik, L. (2018). Fifty shades of dark stories. Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology (4th ed., pp. 4077–4087). IGI. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2255-3.ch353

- Lennon, J. (2017). Dark tourism. In Oxford research encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice. Oxford University Press.

- Lennon, J., & Foley, M. (2000). Dark tourism. (1st ed.). Continuum.

- Macionis, N. (2004). Understanding the film-induced tourist. Paper Presented at International Tourism and Media Conference, Melbourne, Australia., Monash University:

- McKittrick, D., & McVea, D. (2012). Making sense of the troubles. Viking.

- McLoughlin, P. (2006). ‘…it’s a United Ireland or nothing’? John Hume and the idea of Irish unity, 1964–72. Irish Political Studies, 21(2), 157–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907180600707532

- Mintel. (2003). Film tourism: International (October).

- Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (1998). Tourism, promotion and power: Creating images, creating identities. Wiley.

- Murray, B. (1984). The Old Firm: Sectarianism, sport and society in. John Donald.

- Murray, B. (1988). Glasgow’s giants: 100 Years of the Old Firm. John Donald.

- Murray, B. (1998). Bhoys, bears and bigotry: The Old Firm in the new age. Mainstream.

- New Zealand Institute of Economic Research. (2002). Scoping the lasting effects of the Lord of the Rings. report to the New Zealand Film Commission.

- NISRA. (2020). Northern Ireland annual tourism statistics [online], 22 October. Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Retrieved January 25, 2022, from: https://www.nsira.gov.uk.

- NITB. (2019). TNI home [online], Tourismni.com. Retrieved Accessed April 2, 2019, from: https://tourismni.com/[].

- O’Connor, N., Flanagan, S., & Gilbert, D. (2008). The integration of film-induced tourism and destination branding in Yorkshire, UK. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(5), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.676

- O’Leary, B. (1987). The Anglo-Irish Agreement: Folly or statecraft? West European Politics, 10(1), 5–32.

- Riley, R., Baker, D., & Van Doren, C. S. (1998). Movie induced tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(4), 919–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00045-0

- Rolston, B. (1995). Selling tourism in a country at war. Race & Class, 37(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/030639689503700103

- Rubenhold, H. (2019). The five: The untold lives of the women killed by Jack the Ripper. Doubleday.

- Scull, M. M. (2016). The Catholic Church and the hunger strikes of Terence MacSwiney and Bobby Sands. Irish Political Studies, 31(2), 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2015.1084292

- Skinner, J. (2016). Walking the Falls: Dark tourism and the significance of movement on the political tour of West Belfast. Tourist Studies, 16(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797615588427

- Solnit, R. (2002). Wanderlust: A history of walking. Verso.

- Strange, C., & Kempa, M. (2003). Shades of dark tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(2), 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(02)00102-0

- Thompson, S. (1999). The commodification of culture and decolonisation in Northern Ireland. Irish Studies Review, 7(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670889908455622

- Tooke, N., & Baker, M. (1996). Seeing is believing: The effect of film on visitor numbers to screened locations. Tourism Management, 17(2), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(95)00111-5

- Tourism Ireland. (2018). About us [online], Tourismireland.com. Retrieved April 2, 2019, from: https://www.tourismireland.com/About-Us.

- Urry, J. (2002). The tourist gaze (2nd revised edition). SAGE.

- Vellas, F., & Bécherel, L. (1999). The international marketing of travel and tourism. MacMillan.

- Williams, A., & Shaw, G. (1988). Tourism: Candyfloss industry or job creator? Town Planning Review, 59(1), 81–103. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.59.1.2r72w70p330v61v0

- Ziff, T. (1998). Hidden truths: Bloody Sunday 1972. Smart Art Press.