?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines whether and how political uncertainty affects the returns of the TUNINDEX index. The impact of the main political events is supported by parametric and non-parametric tests with an event-driven approach as well as regression analysis. These events are then classified into a typology at different levels to later conduct separate analyses on increasingly homogeneous types. To our knowledge, this work constitutes the first work that tries to tackle the impact of political uncertainty on the Tunisian stock market from this perspective. Our empirical results show that the market response varies according to event type. Thus, the popular uprising has a destructive effect on stock market returns. Democratic transition positively affects the market. The announcement of the election results leads, on average, to a positive reaction and stipulates, among other things, that the market prefers secularists rather than Islamists. Partisan conflicts are destructive to stock market returns. Tunisia offers us a real and rare field of experimentation for a battery of major political events, with the persistence of the state and its institutions. The results of our study are of direct interest to financial authorities and decision-makers who wish to assess the role of political uncertainty in triggering or exacerbating stock price movements and contribute to a better understanding of investor behavior.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Elections, wars, and terrorist attacks are some examples of political uncertainty, but in certain developing countries, such as the MENA area, civil protests, and revolutionary movements are the key political events that have direct repercussions for the country’s future political and economic paths. Hence, for both domestic and international investors, they constitute significant sources of risk and uncertainty.

Four years after initiating the Arab Spring, Tunisia can still boast of a successful transition. The old regime, a symbol of injustice, is no more and the democratic advances are real. In the aftermath of the revolution, there was a certainty that a democratic transition could succeed in pulling the Tunisian economy out of the abyss of the political crisis. Suddenly, the institutional vagueness, the political uncertainty, the rise of political violence, the political appointments, and the hateful and populist discourse shared by almost all political parties (Boubekeur, Citation2016), have shaken the doubt, the uncertainty, the distrust, and the mistrust of the stock market.

The political events that followed the revolution were huge and unprecedented. However, a major political event like the revolution has an explosive effect on the financial market for its economic and social implications. On the one hand, the revolution offers the opportunity to develop more transparent and efficient governance, thus releasing economic potential. On the other hand, the political uncertainty caused by the protests and demands may affect financial market returns and increase volatility by shaking investor confidence. Tunisia offers us a real and rare field of experimentation of a battery of major political events with the persistence of the state and its institutions. Our study is unique from previous research and contributes to the existing literature on three levels. The first is the use of a database, incorporating 256 political events affecting the Tunisian market, the result of a personal effort drawn from several media sources. Second, the impact of each event is supported by parametric and non-parametric empirical tests with an event-driven approach that estimates cumulative abnormal returns over a four-day window. Moreover, we employ regression analysis as an alternative approach by including control variables to detect market reactions in response to political events. Third, to conduct separate analyses, the response of the Tunisian stock market is examined according to a typology at different levels, namely popular uprising, democratic transition, elections, partisan conflicts, strikes of a political nature, drafting of the Constitution, establishment of democratic institutions of the Second Republic and terrorist attacks. To our knowledge, this work constitutes the first work that tries to tackle the impact of political uncertainty on the Tunisian stock market from this perspective. Thus, we provide a granular analysis of the Tunisian market’s response alongside the occurrences of the political events over the period 2010–2015. Moreover, the results of our study are of direct interest to financial authorities and decision makers who wish to assess the role of political uncertainty in triggering or exacerbating stock price movements and contribute to a better understanding of investors’ behavior.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the literature review. Section 3 describes the methodology. Section 4 discusses the data and preliminary statistics. Section 5 reports and discusses the empirical results. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Review of the literature

Domestic financial markets become more exposed to international market crisis risks as a result of market integration (Abdi et al., Citation2023; Athari, Citation2022; Kondoz et al., Citation2019). Although political events are not directly related to stock markets, they are considered to be one of the factors that have a strong effect on returns and trading volume in financial markets (Frey & Waldenström, Citation2004; Smales, Citation2015; Souffargi & Boubaker, Citation2022) and can lead to the interruption or suspension of stock market trading (Jorion & Goetzmann, Citation1999). Diamonte et al. (Citation1996) argue that political risk is a more important determinant of stock market returns in emerging markets than in developed markets. Indeed, the authors find that emerging markets with low political risk offer an 11% higher average return per quarter compared to emerging countries with high political risk. In contrast, the difference is only 2.5% per quarter for developed markets. Alexakis and Petrakis (Citation1991) seek to identify the basic factors that affect stock price behavior. To capture the effects of socio-political instability, the authors use two variables: the number of hours lost due to strikes and the degree of participation of ‘left’ parties in the Greek parliament. The results suggest that the behavior of the market index is more related to alternative investment opportunities and socio-political factors than to corporate earnings and economic activity. To extend the study and empirically examine the relationship between stock market development, political instability, and economic growth. Asteriou and Siriopoulos (Citation2000) extend the study and construct an index that captures the occurrence of events related to political violence. Their empirical results indicate the existence of a strong negative relationship between uncertain socio-political conditions and the general index of the Athens stock market and conclude that uncertain socio-political conditions negatively affect economic growth. In their study, Souffargi and Boubaker (Citation2022) examine the impact of political uncertainty on the volatility of the Tunisian stock market from November 2010 to February 2016. Their study focused on sudden changes in volatility, using the Iterated Cumulative Sums of Squares (ICSS) and the modified ICSS algorithms, as well as the asymmetric GARCH models to consider volatility regime shifts. The results indicate that the volatility of the Tunisian stock market is amplified by both local political events and international events. Furthermore, significant changes in the market tend to occur during periods of civil unrest and political instability, especially during the democratic transformation, suggesting that the correlation between volatility and returns is influenced by political factors.

Azzimonti (Citation2018) constructed a partisan conflict index (PCI) using a semantic search methodology to measure the frequency of newspaper articles reporting lawmakers’ disagreements about policy. The study found a negative relationship between the PCI and aggregate investment in the US. Furthermore, the decline is persistent, which may help explain the slow recovery observed since the end of the 2007 recession. Partisan conflict is also associated. Lower investment rates are observed at the firm level, especially in companies that heavily rely on government spending and those that actively participate in campaign contributions through corporate political action committees (PACs). Prukumpai et al. (Citation2022) examine the correlation between political uncertainty and the behavior of the Thai stock market. The study employs the political uncertainty index (PUI) developed by Luangaram and Sethapramote (Citation2018). Their results indicate that market volatility rises during periods of high political uncertainty, but the impact on short-term stock returns is not significant. Political uncertainty in Thailand has a significant negative impact on the stock market, particularly during coups. Surprisingly, protests have a negative but insignificant effect on the market in the long run. The study shows that political uncertainty increases the equity risk premium, with the strongest impact observed at the lower quantiles of return distributions.

Bechtel (Citation2009) points out that a stable political situation translates into low systematic investment risk, which encourages growth and capital investment, and improves the performance of the overall economy. Arin et al. (Citation2013) test the robustness of political variables in explaining stock returns and volatility in a panel of 17 OECD parliamentary democracies. Their results prove that although the influence of political variables on returns is small, some political variables manage to explain the volatility of returns, such as Single party minority government, Surplus coalition, minimal winning coalition, and government party alignment. Recently, Wisniewski and Moro (Citation2014) analyze the content of communications that result from European Council meetings. They find that investors react favorably when the conclusions and statements issued by heads of state give a positive sentiment and demonstrate a position of moral rectitude. However, returns tend to be negative when communications are overshadowed by excessive use of abstract words and when they are focused on regional rather than global themes.

Among the many political events followed by market participants, political elections occupy a significant portion of the literature. Drawing on the partisan theory proposed by Hibbs (Citation1977), some studies have attempted to examine the link between the political orientation of the elected government and the value of equity. Chiu et al. (Citation2005) show that political elections in South Korea changed the behavior of foreign investors in the capital markets. Nazir et al. (Citation2014) investigate the relationship between uncertain political events and Pakistani market performance between the two styles of governments, i.e. autocratic and democratic. The empirical results provide evidence that political events affect stock market returns and highlight that the KSE is inefficient in the short run. The authors find that the political situation is more stable during autocratic than democratic government. Jones and Banning (Citation2009) examine the association between stock market performance and U.S. elections using monthly returns for a study period spanning 104 years. They find that combinations of White House and/or U.S. Congressional control do not have a systematic effect on stock markets. The results of Colón De Armas and Rodríguez (Citation2012) suggest that fund managers prefer domestic investments when the president is a Republican, and favor international markets when the incumbent president is a Democrat. They find that such behavior, however, does not appear to benefit the shareholders of these funds, since risk is higher, albeit slightly, during the Democratic administration.

The empirical study by Do et al. (Citation2013) provides evidence that connections between corporate managers and politicians through social networks have a strong positive influence on firm value. Moreover, these political associations are more viable for a higher level of regulation and corruption in small firms, and those dependent on an external funding source. Firms connected with winning governments invest more, perform better, hold more liquidity, and enjoy significantly better stock market performance. In the same context, Milyo (Citation2012) raises similar political connections in the United States and finds that firm values are too exaggerated and this explains market overreactions to political events.

International conflicts are another important type of political event that has attracted the attention of several researchers. Frey and Waldenström (Citation2004) find that although financial markets in politically neutral countries, such as Sweden and Switzerland, react to specific large-scale political shocks during World War II. Berkman and Jacobsen (Citation2006) show that conflicts destroy the value of equity capital and increase the volatility of stock markets. They find that wars decrease global stock returns by about 4% per year. Rigobon and Sack (Citation2005) argue that the war in Iraq has a significant impact on several US variables and document that war risk caused, among other things, a fall in Treasury yields and equity prices. For the case of Pakistan, the study of Javed and Ahmed (Citation1999) is considered as the pioneer study in the field and this by focusing on the consequences of the two nuclear detonations (the first one took place on 11 May 1998 in India and the second one on 28 May 1998 in Pakistan) on Karachi Stock Exchange. The results reveal that the trading volume and the level of volatility have increased on the KSE but the response to these two events is different in terms of performance. Indeed, the Indian nuclear tests had a significant negative impact on returns while the Pakistani nuclear tests had no effect. The authors attribute this decline to the reaction to the Indian detonation as well as to the pessimism that prevailed while waiting for Pakistan’s response. Masood and Sergi (Citation2008) find that Pakistan’s political uncertainty has a risk premium ranging from 7.5 to 12%. Guidolin and La Ferrara (Citation2010) examine the effect of 112 internal conflicts (civil wars) and find that many of these conflicts have had a significant impact on market indices and commodity prices.

Zhou et al. (Citation2022) are now investigating the temporal and frequency domain spillover effects between major importers and exporters’ political risk (PR) and the stock returns of China’s rare earths (REs). The overall spillover between (PR) and (REs) is 35.55%, according to their research. They claim that during major financial and political events, such as the global financial crisis, the Russia-Ukraine crisis, the China-European debt crisis, the announcement of WTO dispute resolution regarding rare earths (REs), and the US presidential election, the spillover index rises significantly.

The influence of terrorism on financial markets is the topic of a growing amount of literature. Some research, such as Aslam and Kang (Citation2015), and Barros et al. (Citation2009), confirm the detrimental impact of terrorism on stock market returns. These studies include Carter and Simkins (Citation2004), Drakos (Citation2004, Citation2010), and Nikkinen and Vähämaa (Citation2010). Other study back up the inconsistent influence of terrorist acts on markets. Indeed, Gaibulloev and Sandler (Citation2019) explore the empirical literature on the political economics of terrorism following 9/11 severely. They are concerned with five primary issues: the evolving nature of terrorism, terrorist groups’ roles and organization, the success of counterterrorism strategies, the origins and foundations of terrorism, and the economic implications of terrorism.

Except in tiny terrorist-affected nations, their study demonstrates that terrorism has had little or no influence on economic development or GDP. Karolyi and Martell (Citation2010) examine the impact of terrorist acts on a sample of public companies from 11 different markets. According to the authors, the attacks have the greatest impact on the wealthiest and most democratic countries. Nikkinen et al. (Citation2008) investigate the impact of the 9/11 attacks on returns and volatility in 53 markets. Their findings indicate that the impact of terrorist acts differs by region: the regions with the least integration into the global economy (the Middle East and North Africa) are the least sensitive to terror shocks. Market size and maturity, according to Kollias et al. (Citation2011), are possible predictors of investor reactions. According to Arif and Suleman (Citation2014), stock prices have a mixed bag of considerable positive and negative effects following terrorist operations. The Karachi Stock Exchange, they feel, is still vulnerable to long-term terrorist strikes. In a recent article, Souffargi and Boubaker (Citation2023) examined the effect of the growing terrorist threat on the performance of a small capitalization market—the Tunisian stock market. They conclude that terrorist acts have a detrimental impact on the Tunisian stock market. The decrease—which can be severe in some situations—is, however, short lived: the market rebounds from terrorist shocks in a single day. Second, oil and gas, insurance, and telecommunications are the most harmed industries. Third, different terrorist tactics have varying stock market effects, prompting us to assume that the sort of attack, weapon type, target type, and gravity of the attack may all have an impact on market reactions.

Market integration increases the danger of international market crises for domestic financial markets (Abdi et al., Citation2023; Athari et al., Citation2023; Kondoz et al., Citation2019). The domestic markets are more volatile due to global and local political developments (Smales, Citation2015; Souffargi & Boubaker, Citation2022). Athari (Citation2021) demonstrates that political and global risk factors are crucial to the profitability of the banking industry since countries are less susceptible to political and economic threats. Recently, the findings of Athari and Irani (Citation2022) show that an increase in political and economic risks leads to higher risk-taking in the banking sector internationally, owing to the cumulative negative impact of political uncertainty on non-performing loans. Consistent with earlier research, Saliba et al. (Citation2023) demonstrate that more political instability within a country has the most positive impact on the banking industry in nations with higher credit risk.

Based on the above literature, eight hypotheses are formulated according to the type of events:

Hypothesis 1: Consistent with Chau et al. (Citation2014), the announcement of the popular unrest and demands negatively impacts stock prices

Hypothesis 2: The announcement of events, which surround the transition process, has a positive impact on stock prices.

Hypothesis 3: According to Azzimonti (Citation2018), the announcement of partisan conflicts negatively impacts the market.

Hypothesis 4: The announcement of the adoption of the new constitution has a positive impact on stock market returns.

Hypothesis 5: Consistent with Alexakis and Petrakis (Citation1991), politically motivated strikes negatively impact stock prices.

Hypothesis 6: Consistent with Nazir et al. (Citation2014), the change in the political regime has a positive impact on stock prices.

Hypothesis 7: According to Chiu et al. (Citation2005), Pantzalis et al. (Citation2000), elections have a positive impact on stock market returns.

Hypothesis 8: Consistent with Arin et al. (Citation2008), Drakos (Citation2010), Souffargi and Boubaker (Citation2023), terrorist attacks negatively impact stock market returns.

3. Methodology

3.1. Event study methodology

We adopt the event study methodology to assess the impact of major political events on stock returns. The daily returns for the general index TUNINDEX are defined as follows:

(1)

(1)

Where , is the closing price of the index for the trading session t,

is the closing price of the index for the previous session.

The daily abnormal returns of the general index are calculated as follows:

(2)

(2)

Where is the abnormal return of the stock index at time t,

is the observed current rate of return of the index, and

is the average of daily returns during the estimation period.

We choose an event window of 4 days. It includes the event day disclosed by the media, and 3 days after. For the quality of the study, we did not choose a longer window to avoid the overlapping of two or more events. The choice of the estimation window is designed to neutralize the effect of the post-revolution period (see Souffargi & Boubaker, Citation2023). The length of the estimation window is 200 days/yields.

The statistical significance of individual abnormal returns from the event period was calculated for each sample using the test statistics described by Brown and Warner (Citation1985).

(3)

(3)

The cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) are estimated using the following equation:

(4)

(4)

In the financial literature, several statistical tests are used to measure the significance of abnormal returns. We use the following parametric tests: Time-Series t-test, Cross-sectional t-test, Patell (Citation1976) test or Standardized Residual test, Boehmer et al. (Citation1991) test or standardized cross-sectional test, and Kolari and Pynnönen (Citation2010) test or adjusted standardized cross-sectional test. Non-parametric tests are Corrado (Citation1989) Rank Test and Cowan (Citation1992) Generalized Sign test.

3.2. Regression analysis

Political events can be divided into eight distinct categories: popular uprisings, democratic transitions, elections, partisan conflicts, political strikes, elaboration of the constitution, establishment of the democratic institutions of the Second Republic, and terrorist attacks. There is a dummy variable for each particular type of political event. As a result, the eight dummy variables are as follows:

(5)

(5)

where i = Popular uprising(

, Democratic transition (Transition), Elections, Partisan conflicts (Conflicts), Political strikes (Strikes), Elaboration of the Constitution (Constitution), Establishment of the democratic institutions of the Second Republic (Democratic) and Terrorist attacks (Terrorism). It is commonly acknowledged in the empirical literature that high frequency daily financial series exhibit a set of statistical properties. One of these phenomena is volatility clustering, which shows that days with high variability (vs. low variability) tend to be followed by days with comparable characteristics, regardless of the sign of the fluctuations. Volatility clustering implies the presence of a conditional variance that is variable (with time) and autocorrelated. To account for this autoregressive heteroscedastic conditional variance, we employ Bollerslev’s (Citation1986) GARCH specification. EquationEquation (6)

(6)

(6) estimates market reaction based on the type of political events.

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

where

,

are parameters to be estimated and

is an error term. All the eight day’s dummy variables are regressed in the same regression model. The conditional volatility model is also used. EquationEq. (7)

(7)

(7) is a GARCH (1,1) model where

> 0,

> 0,

> 0 are the required conditions for the variance to be positive while

is the stability condition.

4. Description of the data

The main objective of this study consists of highlighting the existence and then measuring the influence of political events on the evolution of stock prices. To meet this objective, a methodological protocol is constructed and detailed as follows. To investigate the impact of political uncertainty on stock returns, we have tried to build a database incorporating all major political events that have occurred in Tunisia since the ‘Tunisian revolution’. Political events are collected from several media sources. In total, we collected 256 events. The study period is from 17 December 2010 to 16 September 2015.

These events are then classified into a typology at different levels to later conduct separate analyses on increasingly homogeneous types. The distribution of the events in the sample in this typology is as follows:

Types of political events:

Popular uprising = Tunisian Revolution (37 events)

Democratic transition (44 events)

Elections (six events)

Partisan conflicts (30 events)

Political strikes (three events)

Elaboration of the Constitution (six events)

Establishment of the democratic institutions of the Second Republic (15 events)

Terrorist attacks (115 events)

If numerous political events occur on the same day, they are treated as a single event. This brought the total number of events down to 114. If the dates of the political events coincided with days when the Tunis Stock Exchange was closed, these dates are replaced by the first consecutive trading day.

5. Results

5.1. Impact of the popular uprising on stock market returns

Examination of shows that the market showed no significant reaction either on the day of Bouazizi’s immolation or on the following days. The lack of a significant reaction, albeit negative, continued until 28 December 2010. On this date, the abnormal returnsFootnote1 of the TUNINDEX recorded a drop of 1.23% statistically significant at the 1% threshold. The turn of events prompted Ben Ali to intervene for the first time on television. He denounced ‘a minority of extremists who act against the interests of their country’. The next day, 29, a government reshuffle forced the Minister of Communication to leave his post. The TUNINDEX recorded a significant negative abnormal return at the 10% threshold. On the 30th, the dismissal of the governor of the Sidi Bouzid region created a relative lull. Abnormal returns recover and show a moderate performance until 7 January 2011.

Table 1. Average abnormal returns of TUNINDEX following popular uprising.

On 9 January 2011, in the west of the country, clashes between demonstrators and the forces of order in Thala, Kasserine, and Regueb resulted in fourteen deaths according to the authorities. This is the highest human toll since the ‘bread riots’ in December 1983–January 1984. On 10 January 2011 and for the three subsequent days, the abnormal returns of the TUNINDEX recorded a downward trend by showing a highly significant decline of 2.83, 3.88, 3.62, and 4.29%, respectively. The CAR (0.3) is −14.62%.

On January 13, while the International Federation of Human Rights Leagues reported a death toll of sixty-six since the beginning of the violence, President Ben Ali spoke again. He declared that he had been ‘misled’ in his analysis of the situation, and promised not to seek a sixth term in the presidential election scheduled for 2014, to stop firing live ammunition at demonstrators, and to restore freedom of information, including access to the Internet. The message appears to have a calming effect on the stock market. Abnormal returns, although not significant, recovered for the 14 January 2011 trading session. The same day, the capital was again the scene of violent demonstrations demanding the departure of President Ben Ali. A few hours later, Mohamed Ghannouchi announced that he would assume the duties of interim head of state. The news of the flight of President Ben Ali, who had taken refuge in Saudi Arabia, spread. As a first reaction, the Tunis Stock Exchange suspended trading for the first time in its history from 17 to 30 January to prevent investors from panicking.

During the closure of the stock market, political events continued to occur daily. On the 30th, the leader of the Islamist movement Ennahda returned to Tunis after twenty years of exile in London. After its opening on 31 January 2011, the market recorded a highly significant negative abnormal return of 2.81%. From 3 February 2011 until 7 February 2011, a wind of optimism blew on the market. The ARs reached 2.48, 2.99, and 2.68%, respectively. The cumulative ARs gained 8.09% for a four-day event window.

On 6 February 2011, the transitional government announced the suspension of the Democratic Constitutional Rally. From 14 February 2011, the crisis of confidence regained the market with a successive abnormal decline of the index TUNINDEX −0.085, −1.39, −1.16, and −1.17%. On 20 February 2011, thousands of demonstrators gathered at the Kasbah Square in Tunis to demand the resignation of Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi—who already held this position under President Ben Ali. The accumulation of abnormal returns, over a window of four days, then shows a decline of 8.16% highly significant at the threshold of 1%. On the 25th, while the largest demonstration since the fall of the former president was held in Tunis, the abnormal returns of the market index showed a counter performance of −2.77% significant at the threshold of 1%. Following this regression, the financial market council, for the second time, suspended the quotation from 28 February to 4 March to protect savings invested in securities, financial products negotiable on the stock exchange, and any other investment giving rise to a public appeal for savings.

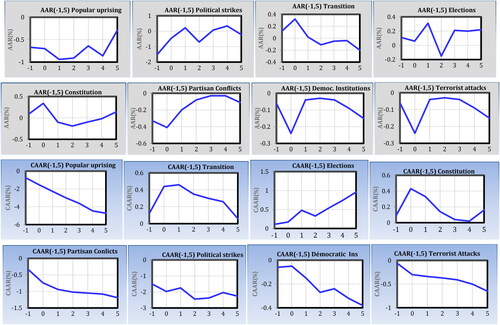

Examination of reveals that the average abnormal returns calculated for the sample of 24 events, on the event day and subsequent days, is negative and massively significant. The cumulative average abnormal returns CAAR over four days event window (0,3) is significantly negative at −0.28%. Thus, the results prove that the revolution has a destructive effect on stock returns. This confirms our hypothesis H1.

5.2. Democratic transition

Following demonstrations on 27 February 2011, Mohammed Ghannouchi resigned from office. Interim President Fouad Mebazaa appointed Béji Caïd Essebsi as Prime Minister. On 1 March 2011, the Islamist movement Ennahdha was legalized. The next day, several hundred political prisoners were released under the general amnesty decreed in January after the fall of President Ben Ali. As soon as it opened on 5 March 2011, the market recorded a highly significant abnormal appreciation at the 1% threshold, i.e. a CAR, over a four-day event window, of 7.02% on 7 March 2011. Since then, the market has followed a bullish trend. This improvement comes as a reaction to the appointment of Béji Caïd Essebsi a third provisional government composed of technocrats.

On 8 August 2011, demonstrations broke out in Tunis to demand independent justice following the release of former ministers and the impunity granted to ex-dignitaries. The decline of the TUNINDEX is pronounced. Indeed, the AR shows a counter performance of −0.85% and reaches −2.17% the next day. The ARs show a counter performance on 6 September 2011 of 0.93% significant at the threshold of 5%. This decline is due, in particular, to the government’s announcement of the strict application of the state of emergency and the prohibition of all police union activity, after the violence that has shaken disadvantaged regions. The TUNINDEX was able to recover gradually until mid-2012, but political instability caused it to fall back to a lower level than before the revolution due to the vagueness surrounding the transition process and the failure of the National Constituent Assembly (ANC) to adopt the Fundamental Law and to define a clear and consensual roadmap on the next political deadlines.

On 20 May 2013, after the government decided to ban the congress of the Salafist movement Ansar al-sharia (‘Partisans of Sharia’), clashes broke out between police and Salafists in the city of Ettadhamen, in the western suburbs of Tunis. As a result of this event, the TUNINDEX recorded a drop in AR of 0.95% significant at the 5% threshold. As part of the national dialogue initiated in October 2013, the political forces agreed, on 14 December 2013, on the appointment of the Minister of Industry Mehdi Jomaa (independent) as Prime Minister, replacing Ali Larayedh (Ennahda). Following this governmental change, the TUNINDEX followed a downward trend by recording, on 17 December, a negative AR of −0.85% significant at the threshold of 10% or a CAR (0, 3) of −2.08%. The new apolitical government, made up of independent technocrats, is responsible for leading the country into elections expected at the end of the year.

shows that the democratic transition is positively affecting the stock market as evidenced by the AAR on the event day however the CAAR over a four-day window is not significant. This reaction is not too pronounced, which invalidates the H2 hypothesis.

Table 2. Average abnormal returns of TUNINDEX following democratic transition.

5.3. Partisan conflicts

In July 2012, the TUNINDEX was able to gradually recover to above the level of late 2010. However, the worsening political tensions and partisan conflicts since mid-2012 reversed this trend. Each party was interested in finding the best positioning on the political chessboard, alliance, and opposition tactics, considerations on the strategies to follow to impose itself on the political scene, oppose or support the transitional government, push the demands of the street, or on the contrary make them disappear.

Partisan conflicts took a very large scale on 6 February 2013, the day of the assassination of the lawyer Chokri Belaïd general coordinator of the Party of Democratic Unified Patriots and leader of the Popular Front (radical left), and 25 July 2013, the constituent and general coordinator of the popular movement Mohamed Brahmi. The AARs visualized in reveal that partisan conflict is too destructive to stock returns. Indeed, a conflict between the different parties leads to an average decline in returns of 0.41% significant at the 1% threshold. The CAAR (0,3) is significantly negative at −0.72%. These results confirm hypothesis H3.

Table 3. Average abnormal returns of TUNINDEX following partisan conflicts.

5.4. Constitution-making

In addition to the unrest attributed to the deteriorating security situation, the delays in drafting the new constitution and organizing new elections have increased political uncertainty and investor distrust. The submission of the draft Constitution and all related documents to the order desk of the National Constituent Assembly on 14 June 2013, marks the Tunis stock exchange with a positive abnormal return of around 0.38%. On 26 January 2014, three years after the start of the revolution and two years after its election, the National Constituent Assembly finally adopted the new Constitution establishing the Second Tunisian Republic by 200 votes for, 12 against, and four abstentions. The new constitution provides for a two-headed executive composed of an elected president and a prime minister responsible to the parliament. shows that the development of the Constitution for the entire sample positively affects stock market returns. On the day of the event, i.e. 27 January 2014, the stock market recorded an abnormal appreciation of 1.35% significant at the 1% threshold. The adoption of the Constitution reassures investors which confirms our hypothesis H4.

Table 4. Average abnormal returns of TUNINDEX following constitution-making.

5.5. Political strikes

Of the three strikes studied, only the General Strike in Siliana has produced a significant reaction from the stock market. Indeed, the TUNINDEX recorded an abnormal counter performance of 1.33% on the day of the strike. The CAR over the first four days is negative by about 2.8% statistically significant at the 1% threshold. Besides, no statistically significant effect is recorded for the other strikes. Examination of shows that strikes of a political nature negatively affect stock market returns but have no significant impact, which rejects our hypothesis H5.

Table 5. Average abnormal returns of TUNINDEX following political strikes.

5.6. Impacts of the establishment of the democratic institutions of the Second Republic on the returns

After the terrorist attack perpetrated on 7 January at the premises of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris, the head of the provisional government Mehdi Jomaa participated on 11 January 2015, in the ‘Republican march’ against terrorism in Paris. The next day, the abnormal returns of TUNINDEX show a very appreciable increase of 1.15% significant at the threshold of 5%. This is the only event that has generated a significant reaction out of all 15 selected events.

shows that the average abnormal return on the day of the event is positive by about 0.01% but not significant. This invalidates hypothesis H6 and proves that the establishment of democratic institutions did not significantly affect stock market returns. The fact can be explained by two reasons. On the one hand, the Constitution of the Second Republic provides for a quasi-parliamentary system, which implies the responsibility of the winning party in the elections to lead the government and the state policy, according to the program that was submitted to the voters. However, Nidaa Tounès, the political party that emerged from the elections, has set up a new government governed by a heterogeneous coalitionFootnote2: Nida Tounes, Ennahdha, Afek Tounes, and the Free Patriotic Union. Thus, Ennahda is the second largest party represented in Parliament.

Table 6. Average abnormal returns of TUNINDEX following establishment democratic institutions.

On the other hand, the political life in Tunisia is still a scene of many agitations and tensions of a rhythmic pace: Violent dissensions within the winning party in the elections, social demands, liberticide laws, suspicions of corruption, and terrorism. As a result, the political crisis and its manifestations have made investors anxious and disturbed by the turn of events: security risks combined with the deterioration of the economic situation with a non-encouraging outlook, and a very worrying social situation.

5.7. Elections

After the popular uprising, Tunisia entered a phase of democratic transition. The transition from an authoritarian or totalitarian system to a democratic regime is ensured by free and transparent elections. The election campaign for the election of the constituent assembly, to draft the new constitution, was launched on 1 October 2011. This event did not provoke an obvious response from the market. The election was held on Sunday, 23 October 2011. The party Ennahdha ‘the Renaissance’ won the elections with 89 seats out of a total of 217 with 41.4% of the vote. The day after the election, the Tunis stock exchange recorded an abnormal depreciation of 2.09% highly significant at the threshold of 1%.

26 October 2014, was the date of the parliamentary elections. With a turnout is 69%, the main anti-Islamist formation Nidaa Tounès, of Béji Caïd Essebsi, won the first legislative elections with 39.6% of the vote and 86 seats. The Islamist party Ennahda, in power since its victory in the previous elections in October 2011, is in decline, with 31.8% of the vote and 69 deputies. On 27 and 28 October, the TUNINDEX ARs recorded a very significant increase of 1.38 and 1.46%, respectively. The cumulative abnormal returns reached a performance of 3.83% significant at the 1% threshold. These results come to confirm that the stock market prefers seculars rather than Islamists. For the first round of the presidential election on 24 November 2014, the market showed a positive but insignificant AR, following the victory of Béji Caïd Essebsi, leader of the anti-Islamist party. For the second round of the presidential election, the TUNINDEX exhibits a very appreciable increase of 1.33% highly significant two days before the election deadline. The presidential election was won by Béji Caïd Essebsi with 55.7% of the vote, ahead of the outgoing president Moncef Marzouki.

An examination of shows that five elections have a positive impact on stock market returns. Indeed, despite the absence of a significant reaction, the AAR(0) of the total sample is 0.06% on the day of the event and 0.31% the day after. The completion of this political process has provided reassuring and positive signals and restored confidence to local and foreign investors by providing them with better visibility on market and country performance. For a four-day event window, the cumulative average abnormal returns are also positive but non-significant which invalidates our hypothesis H7.

Table 7. Average abnormal returns of TUNINDEX following elections.

5.8. Impacts of terrorist attacks

As depicted in , on the day of the attack, TUNINDEX showed negative and significant average abnormal returns (AAR). Except for the fifth day, which has significantly negative returns, the days following the attack are characterized by non-significant negative average abnormal returns (see Souffargi & Boubaker, Citation2023). The cumulative average abnormal returns CAAR over a six-day event window (0, 3) is 0.39%, which is significantly negative (). This finding supports our H8 hypothesis. Terrorist attacks are destructive and have a significant impact on the financial market. Our findings are consistent with previous research (Aslam et al., Citation2015; Aslam & Kang, Citation2015; Mukerji & Tallon, Citation2001). Following a terrorist act, stock market returns fall. Investors are hesitant because of ambiguity and uncertainty. Terrorist events elicit strong emotional responses.

Figure 1. Average abnormal returns and cumulative average abnormal returns of TUNINDEX following major political events during the period 2010–2015, event window (−1, 5).

Table 8. Average abnormal returns of TUNINDEX following terrorist attacks.

5.9. Impact of political events type on stock returns

As shown in , the statistical analysis of the Lagrange multiplicator test reveals that the heteroscedasticity is highly significant at 1%, leading to the huge rejection of the null hypothesis of no ARCH effect. These findings suggest the presence of an autoregressive heteroskedastic conditional variance, which is characterized by volatility clustering periods. As a result, we will retain a GARCH (1, 1) model.

Table 9. Descriptive statistics of the Tunisian stock market returns.

depicts the impact of political events on TUNINDEX returns by kind of political event. According to the regression results, the TUNINDEX has a performance of 0.06% in the absence of political events significant at the 1% threshold. The three types of events that devastate the market are popular uprisings, political conflicts, and terrorist attacks. In fact, popular uprising are really considerable, resulting in a market underperformance of 0.36%. Partisan conflicts have a significant negative impact on TUNINDEX performance; the coefficient (β4 = −0.0029) indicates that each extra Partisan conflict is related to a 0.29% drop in TUNINDEX, which is significant at the 1% level. The negative coefficient value (β8 = −0.0018) is highly significant at the 1% level, indicating that each terrorist attack results in a 0.18% decrease in returns.

Table 10. The impact of political event type on the TUNINDEX returns during 2010–2015.

Despite their detrimental effects, political strikes have no statistically significant effect on the veracity of their impact. The events surrounding the drafting of the constitution have had a significant positive influence, resulting in a market performance of 0.39% above the 1% threshold. Elections, the democratic transition, and political regime change all have beneficial effects on stock returns, while they are still not statistically significant (). The diagnostic tests show there is no longer ARCH effect in the standardized residuals. The results of the Nyblom stability test for the GARCH (1,1) model, reported in , confirm globally the null hypothesis that the parameters are stable. These findings further support our hypotheses H1, H3, H4, and H8 and reject hypotheses H2, H5, H6, and H7.

Table 11. Nyblom test for parameter stability.

Institutional uncertainty has plagued the business climate since 2011. Political conflicts have undermined the security climate and blocked major reforms. Tunisia’s rating has been downgraded to speculative grade by Standard and Poor’s since May 2012, by Fitch Rating since December 2012, and by Moody’s since February 2013. However, the unanimous adoption of the new constitution and the ANC’s vote of confidence in the new, independent government have generated a shock of confidence and reversed the outlook for the Tunisian economy. The financial market is beginning to recover. Foreign lenders have lowered the barriers to external financing, enabling the country to emerge from its financial impasse. The culture of consensus has taken hold, enabling the formation of a government of national unity in which secular groups coexist with the Islamist party Ennahdha. All these factors led Moody’s to confirm Tunisia’s sovereign rating at BA3, with the outlook upgraded from negative to stable. However, this change in outlook did not improve the country’s sovereign rating. The main reasons for this caution lie in the delay in reforms (banking sector, taxation, etc.), the growing number of security problems and economic fundamentals (banks’ heavy dependence on BCT financing, an alarming current account deficit, a budget riddled with wage increases, weak private investment). The economic situation remains worrying. In addition, the security situation in 2015 had a heavy impact on the tourism sector and foreign direct investment, which explains the 33.8% drop in tourism receipts compared with their 2014 levels of 2249MDT. While the change in outlook represents a step towards normalizing Tunisia’s rating, its implications remain insignificant. A wait-and-see attitude remains the order of the day. The government faces a major challenge: to respond to the legitimate demands of workers, to halt the development of the informal sector—including smuggling, to rapidly implement reforms that will restore the confidence of economic players, and to pursue democratization at regional and local levels. all in a polarized political context.

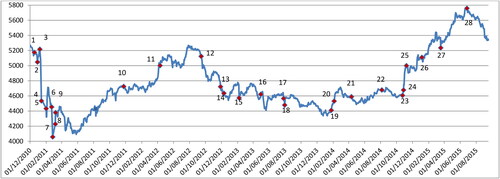

Figure 2. Time series plot of the TUNINDEX alongside the occurrences of major political events. Notes: 1-Immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, 2-demonstrations spread to provincial towns, 3-Violent repression of demonstrators resulting in 14 deaths, 4-Flight of Ben Ali, 5-Rached Ghannouchi, leader of the Islamist movement Ennahda returned to Tunisia, 6-Request extradition of Ben Ali and his wife, 7-Demonstrations demanding the resignation of the prime minister, 8-Nomination of the third provisional government, 9-Legalisation of Moncef Marzouki’s party, the Congress for the Republic, 10-election of the National Constituent Assembly, 11-violent clashes between police and demonstrators, 12-attack on the premises of the US embassy, 13-General Strike in Siliana called by The Tunisian General Labour Union, 14-Feriana attack, 15-Chokri Belaid assassination, 16-Bomb explosion in Chaambi Mount, 17-Mohamed Brahmi assassination, 18-Death of 8 soldiers following an ambush, 19-Adoption of the new Constitution of the Tunisian Republic, 20-Violent confratations of Raoued, 20- and 21-Explosion of two landmines in Chaambi Mount, 22-Sbeitla, Hydra and Sammama Attacks, 23-Violent confrontations of Chabaou, 24-Beji Caïd Essebsi, leader of the anti-Islamist party Nidaa Tounès, won the first legislative election, 25-Nibber Attack, 26-President Beji Caïd Essebsi instructs the former minister to form a new government, 27-Bardo museum attack, 28-Sousse attack.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we have focused on identifying the weight of political uncertainty on stock market returns. We use a database integrating 256 political events affecting the TUNINDEX returns. These events are then classified into a typology at different levels to later conduct separate analyses on increasingly homogeneous types. To our knowledge, this study is unique in its nature as it examines the impact of political uncertainty on the Tunisian stock market from this perspective. Based on the empirical results, we find that the market response varies according to the type of event. Thus, several lessons can be drawn:

The revolution has the most destructive effect on the returns of the Tunis stock market. Each event conducted during the waves of popular protests significantly reduces market returns. Interestingly, we found that political conflicts are more harmful than terrorist attacks. The strikes with political characters affect negatively the stock market returns but their effect is not significant. The democratic transition positively affects the stock market. However, this reaction is not too pronounced. The events surrounding the drafting of the constitution have had a significant positive influence. The announcement of the establishment of democratic institutions does not lead to any statistically significant reaction in the market returns. Despite the lack of a significant reaction, the announcement of the election results leads, on average, to a positive market reaction. Indeed, the completion of this political process has provided reassuring and positive signals and restored confidence to local and foreign investors by providing them with better visibility on market and country performance. The market’s reaction to the parliamentary elections is noteworthy. The abnormal performance, on the day of the announcement of the gain of the anti-Islamist party, is statistically significant. These results confirm that the Tunisian stock market prefers the secular rather than the Islamist.

Our results have important implications for investors and policymakers. From the investors’ perspective, political events represent a growing business risk that investors must now consider to predict properly how events can impact future stock market volatility and consequently manage its effects on capital flows, international trade, and the whole economy. The political events during the revolution and post-revolution were enormous and unprecedented. They must have shaken the panic and distrust of investors. However, the Tunis Stock Exchange has resisted relatively well thanks to ‘emergency measures’, in consultation with the profession and market authorities, taken to avoid panic investors and disproportionate collapse of the market. Communication campaigns, workshops, and press conferences have been organized to raise awareness among business leaders and politicians on the virtues of the market. The Tunis Stock Exchange hosted the main actors of the political scene, parties in power and in opposition. At each meeting, the message was the same: the stock market is a lever of financing that remains largely underutilized in Tunisia. The Tunis Stock Exchange must now attract more institutional investors, local and foreign, to consolidate its path to development. A major challenge that can succeed only through major reforms and a strong political will.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Wafa Souffargi

Wafa Souffargi, PhD, University of Sousse, Higher Institute of Management of Sousse, Tunisia. Her research interests are Behavioral Finance, Financial Risk Management, Financial Economics and Corporate Finance. She is an associate researcher at International Finance Group Tunisia IFGT lab of University of Tunis El Manar, Tunisia.

Adel Boubaker

Adel Boubaker, a full professor of finance and accounting at University of Tunis El Manar, Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management of Tunis. His research interests are Financial Analysis, Finance Banking, Financial Risk Management, Financial Accounting, Corporate Finance, international financial institutions in the process of reducing development disparities between countries and in the issue of supporting sustainable development green finance.

Notes

1 Abnormal returns and CAR(0,3) for each political event are available upon request.

2 The first version of the government, presented in January, with only ministers from the anti-Islamist party Nidaa Tounès and the Free Patriotic Union, did not have the prior approval of parliament.

References

- Abdi, A., Souffargi, W., & Boubaker, A. (2023). Family firms’ resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from French firms. Corporate Ownership and Control, 20(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.22495/cocv20i3siart12

- Alexakis, P., & Petrakis, P. (1991). Analysing stock market behaviour in a small capital market. Journal of Banking & Finance, 15(3), 471–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(91)90081-V

- Arif, I., & Suleman, T. (2014). Terrorism and stock market linkages: An empirical study from Pakistan (No. 58918). University Library of Munich.

- Arin, K. P., Ciferri, D., & Spagnolo, N. (2008). The price of terror: The effects of terrorism on stock market returns and volatility. Economics Letters, 101(3), 164–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2008.07.007

- Arin, K. P., Molchanov, A., & Reich, O. F. (2013). Politics, stock markets, and model uncertainty. Empirical Economics, 45(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-012-0601-5

- Aslam, F., & Kang, H. G. (2015). How different terrorist attacks affect stock markets. Defence and Peace Economics, 26(6), 634–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2013.832555

- Aslam, F., Rafique, A., Salman, A., Kang, H. G., & Mohti, W. (2015). The impact of terrorism on financial markets: Evidence from Asia. The Singapore Economic Review, 63(5), 1183–1204. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590815501118

- Asteriou, D., & Siriopoulos, C. (2000). The role of political instability in stock market development and economic growth: The case of Greece. Economic Notes, 29(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0300.00037

- Athari, S. A. (2021). Domestic political risk, global economic policy uncertainty, and banks’ profitability: Evidence from Ukrainian banks. Post-Communist Economies, 33(4), 458–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2020.1745563

- Athari, S. A. (2022). Financial inclusion, political risk, and banking sector stability: Evidence from different geographical regions. Economics Bulletin, 42(1), 99–108.

- Athari, S. A., & Irani, F. (2022). Does the country’s political and economic risks trigger risk-taking behavior in the banking sector: a new insight from regional study. Journal of Economic Structures, 11(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-022-00294-4

- Athari, S. A., Kirikkaleli, D., & Adebayo, T. S. (2023). World pandemic uncertainty and German stock market: Evidence from Markov regime-switching and Fourier based approaches. Quality & Quantity, 57(2), 1923–1936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01435-4

- Azzimonti, M. (2018). Partisan conflict and private investment. Journal of Monetary Economics, 93, 114–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2017.10.007

- Barros, C. P., Caporale, G. M., & Gil‐Alana, L. A. (2009). Basque terrorism: Police action, political measures and the influence of violence on the stock market in the Basque Country. Defence and Peace Economics, 20(4), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242690701750676

- Bechtel, M. M. (2009). The political sources of systematic investment risk: Lessons from a consensus democracy. The Journal of Politics, 71(2), 661–677. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381609090525

- Berkman, H., & Jacobsen, B. (2006, February). War, peace and stock markets. In EFA 2006 Zurich Meetings.

- Boehmer, E., Musumeci, J., & Poulsen, A. B. (1991). Event-study methodology under conditions of event-induced variance. Journal of Financial Economics, 30(2), 253–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(91)90032-F

- Bollerslev, Tim. (1986). Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. Journal of Econometrics, 31(3), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(86)90063-1

- Boubekeur, A. (2016). Islamists, secularists and old regime elites in Tunisia: Bargained competition. Mediterranean Politics, 21(1), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2015.1081449

- Brown, S. J., & Warner, J. B. (1985). Using daily stock returns: The case of event studies. Journal of Financial Economics, 14(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(85)90042-X

- Carter, D. A., & Simkins, B. J. (2004). The market’s reaction to unexpected, catastrophic events: The case of airline stock returns and the September 11th attacks. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 44(4), 539–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2003.10.001

- Chau, F., Deesomsak, R., & Wang, J. (2014). Political uncertainty and stock market volatility in the Middle East and North African (MENA) countries. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 28, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2013.10.008

- Chiu, C. L., Chen, C. D., & Tang, W. W. (2005). Political elections and foreign investor trading in South Korea’s financial markets. Applied Economics Letters, 12(11), 673–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504850500190097

- Colón De Armas, C. A., & Rodríguez, J. (2012). Do U.S. politics influence investment decisions? Evidence from global mutual funds. Working paper.

- Corrado, C. J. (1989). A nonparametric test for abnormal security-price performance in event studies. Journal of Financial Economics, 23(2), 385–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(89)90064-0

- Cowan, A. R. (1992). Non parametric event study tests. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 2(4), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00939016

- Diamonte, R. L., Liew, J. M., & Stevens, R. L. (1996). Political risk in emerging and developed markets. Financial Analysts Journal, 52(3), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v52.n3.1998

- Do, Q. A., Lee, Y. T., & Nguyen, B. D. (2013). Political connections and firm value: Evidence from the regression discontinuity design of close gubernatorial elections. Available at SSRN 2190372.

- Drakos, K. (2004). Terrorism-induced structural shifts in financial risk: airline stocks in the aftermath of the September 11th terror attacks. European Journal of Political Economy, 20(2), 435–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2003.12.010

- Drakos, K. (2010). Terrorism activity, investor sentiment, and stock returns. Review of Financial Economics, 19(3), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rfe.2010.01.001

- Frey, B. S., & Waldenström, D. (2004). Markets work in war: World War II reflected in the Zurich and Stockholm bond markets. Financial History Review, 11(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0968565004000046

- Gaibulloev, K., & Sandler, T. (2019). What we have learned about terrorism since 9/11. Journal of Economic Literature, 57(2), 275–328. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20181444

- Guidolin, M., & La Ferrara, E. (2010). The economic effects of violent conflict: Evidence from asset market reactions. Journal of Peace Research, 47(6), 671–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310381853

- Hibbs, D. A. (1977). Political parties and macroeconomic policy. American Political Science Review, 71(4), 1467–1487. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961490

- Javed, A. Y., & Ahmed, A. (1999). The response of Karachi Stock Exchange to nuclear detonation. The Pakistan Development Review, 38(4II), 777–786. https://doi.org/10.30541/v38i4IIpp.777-786

- Jones, S. T., & Banning, K. (2009). US elections and monthly stock market returns. Journal of Economics and Finance, 33(3), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-008-9059-x

- Jorion, P., & Goetzmann, W. N. (1999). Global stock markets in the twentieth century. The Journal of Finance, 54(3), 953–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00133

- Karolyi, G. A., & Martell, R. (2010). Terrorism and the stock market. International Review of Applied Financial Issues and Economics, 2(2), 285.

- Kolari, J. W., & Pynnönen, S. (2010). Event study testing with cross-sectional correlation of abnormal returns. Review of Financial Studies, 23(11), 3996–4025. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhq072

- Kollias, C., Papadamou, S., & Stagiannis, A. (2011). Terrorism and capital markets: The effects of the Madrid and London bomb attacks. International Review of Economics and Finance, 20(4), 532–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2010.09.004

- Kondoz, M., Bora, I., Kirikkaleli, D., & Athari, S. A. (2019). Testing the volatility spillover between crude oil price and the US stock market returns. Management Science Letters, 9(8), 1221–1230. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.4.019

- Luangaram, P., & Sethapramote, Y. (2018). Economic impacts of political uncertainty in Thailand (No. 86). Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research.

- Masood, O., & Sergi, B. S. (2008). How political risks and events have influenced Pakistan’s stock markets from 1947 to the present. International Journal of Economic Policy in Emerging Economies, 1(4), 427–444. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEPEE.2008.021285

- Milyo, J. (2012). Do state campaign finance reforms increase trust and confidence in state government? In Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

- Mukerji, S., & Tallon, J. M. (2001). Ambiguity aversion and incompleteness of financial markets. The Review of Economic Studies, 68(4), 883–904. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-937X.00194

- Nazir, S. M., Younus, H., Kaleem, A., & Anwar, Z. (2014). Impact of political events on stock market returns: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 30(1), 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEAS-03-2013-0011

- Nikkinen, J., & Vähämaa, S. (2010). Terrorism and stock market sentiment. Financial Review, 45(2), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6288.2010.00246.x

- Nikkinen, J., Omran, M. M., Sahlström, P., & Äijö, J. (2008). Stock returns and volatility following the September 11 attacks: Evidence from 53 equity markets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 17(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2006.12.002

- Pantzalis, C., Stangeland, D. A., & Turtle, H. J. (2000). Political elections and the resolution of uncertainty: The international evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance, 24(10), 1575–1604. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(99)00093-X

- Patell, J. M. (1976). Corporate forecasts of earnings per share and stock price behavior: Empirical test. Journal of Accounting Research, 14(2), 246–276. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490543

- Prukumpai, S., Sethapramote, Y., & Luangaram, P. (2022). Political uncertainty and the Thai stock market. Southeast Asian Journal of Economics, 10(3), 227–257.

- Rigobon, R., & Sack, B. (2005). The effects of war risk on US financial markets. Journal of Banking & Finance, 29(7), 1769–1789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.06.040

- Saliba, C., Farmanesh, P., & Athari, S. A. (2023). Does country risk impact the banking sectors’ non-performing loans? Evidence from BRICS emerging economies. Financial Innovation, 9(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-023-00494-2

- Smales, L. A. (2015). Better the devil you know: The influence of political incumbency on Australian financial market uncertainty. Research in International Business and Finance, 33, 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2014.06.002

- Souffargi, W., & Boubaker, A. (2022). Structural breaks, asymmetry and persistence of stock market volatility: Evidence from post-revolution Tunisia. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 14(9), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v14n9p51

- Souffargi, W., & Boubaker, A. (2023). The effects of rising terrorism on a small capital market: Evidence from Tunisia. Defence and Peace Economics, 34(3), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2021.2007338

- Wisniewski, T. P., & Moro, A. (2014). When EU leaders speak, the markets listen. European Accounting Review, 23(4), 519–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2014.884931

- Zhou, M. J., Huang, J. B., & Chen, J. Y. (2022). Time and frequency spillovers between political risk and the stock returns of China’s rare earths. Resources Policy, 75, 102464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102464