?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Inter-firm relations plays a significant role in business performance especially within the international context. Several studies have attempted to understand how inter-firm relational adaptation is shaped through the use of various theoretical frameworks. What has been missing from the current understanding is the degree to which contextual (institutional) dynamics (variations) influence inter-firm adaptation, a subject which this paper intends to address. This study has used a setup of data from two distinctive emerging markets which have different institutional arrangements to examine how institutions determine inter-firm relational adaptation. The framework of the research uses business-to-business relationships, which have existing formal transactional governance setup. We use transactional, relational, and institutional theories in developing the paper. The study used manufacturing firms in Poland, focusing on the buying side of the relationship. Surveyxact software was used to collect the responses. Firms were selected from a targeted sample frame of 1800 respondents. A sample of 201 respondents was used, which is about 33% response rate (computation of response rate included the partially completed questionnaires). In Tanzania the questionnaires were delivered physically to a targeted sample frame was 750 firms and a final sample extracted with completed questionnaires received was 240 making a response rate of around 31%. Findings has indicated that the institutional dynamics/variations influences the inter-firm relational adaptation. Specific findings indicated that the effect of supplier asset specificity on inter-firm relational adaptation is stronger in less structured than in structured emerging markets. Volume uncertainty decreases strongly the effect of asset specificity on adaptability in structured than in less structured emerging markets. The study is limited due to the fact that it used few dimensions from transaction cost theory and relational governance perspectives. In addition, we employed data from a single context. This study provides a unique approach in understanding the influence of institutions on the inter-firm relational adaptation in the context of heterogeneous emerging markets. The unique contribution of this study is in two folds. First is that it uncovered the influence of transactional dimensions of inter-firm relational adaptation and second is that it used institutional differences in emerging markets.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Understanding the Interfirm relational adaptation is of strategic relevance because a significant amount of money is spent in business relations. Industry 4.0 (14.0) permits production firms to move ‘production back to increase flexibility and reduce lead time’ (Dachs et al., Citation2019). Current gap which exist in the literature is how collaboration affects the implementation of I4.0 technology to achieve efficiency and effectiveness in production and how home and host environmental characteristics shape this linkage (Awan et al., Citation2022). Pressure which push firms to think beyond boundaries to achieve stability due to dynamic environmental forces, particularly in emerging markets is increasingly prevalent (Gölgeci et al., Citation2019).

Flexible organizational models are important avenue for driving smallholder competitiveness (Adetoyinbo & Mithöfer, Citation2023). Relational factors are important in managing inter-organizational operational hazards (Shahzad et al., Citation2018; Wood, Citation2018). Further, inter-firm conflict resolution (Shahzad et al., Citation2020) and costs saving can be achieved when firms can adapt to unanticipated changes (Anderson et al., Citation1994; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). Research shows that relational governance can enhance a firm’s competitive position (Powell, Citation1990) and inhibits opportunistic behaviors by building strong mutual commitment and trust (Brown et al., Citation2000). Relational governance can also reduce production and transaction costs by converting strengthened partnerships into stable and loyal strategic alliances (Hewett & Bearden, Citation2001).

There has been increasing attention to exploring the relational view of a firm adaptation climate (Canevari et al., Citation2020; Qian, 2021; Yang et al., Citation2021) as well as understanding institutional sensitivity when conducting interfirm relational studies (Voldnes & Kvalvik, Citation2017).

Several studies have attempted to understand how relational governance is shaped by using general terms which may be limited in wider context. The aim of developing theory is to provide a generalized understanding. When it comes to inter-firm relational adaptation, the classical understanding is that institutions play a significant role in shaping how firms respond inrelations. Often the dimension of culture in most of such studies is the one which is given an overall high attention. What has been missing from the current body of knowledge is how instituional dynamics influence inter-firm adaptation. Institutional ssumptions are often taken for granted (Canevari et al., Citation2020; Voldnes & Kvalvik, Citation2017) but much insights can be acquired by studying their dynamics.

We have used the term dynamic in this study to emphasize the fact that nations experience periods of drastic changes within the context of institutions and such dynamics or variations will have implied effect on relational governance. We have explored the two countries under this study to see how they have moved in drastic waves of time and show institutions have been shaped in the same duration. Often theories are developed under the context of stable assumptions but one of the key challenges within this thinking is that if we do not set aside specific conditions for their application, they could be miss leading.

Lables such as emerging markets has been used to infer a homogeneous group of markets which display similar characteristics. When such lables are taken for granted this could also mislead our capacity to predict relational governance and we may also have limited explanation for variations found in studies which are performed across the variying contexts. This paper has filled this gap by bringing the concept of dynamics using the ‘advanced/structured and less advanced/structured markets’ within the framework of institutional variations of emerging markets with the aim of understanding whether we will be able to find differences in predicting interfirm-relational. In this study, we choose to use the context of emerging markets which have two different stages of development to examine how the institutions shape such a relationship. We used the terms advanced/structured (advanced emerging markets) and less structured (less advanced emerging markets) to separate the two emerging economies used i.e. Poland and Tanzania to represent advanced/structured and less structured emerging markets respectively. The reason for the separation of the two economies in terms of structures is the difference that exists in the level of transactional arrangements when economies advance (Peng et al., Citation2008).

Theoretical perspectives

This study specifically seeks to understand how inter-firm relational adaptation is influenced from the institutional dynamic point of view. A bland of theories has been selected based on their contribution to establishing this understanding. The transaction cost theory is a well-grounded theory within this context because it addressed the mechanism that we try to govern inter-firm relations. The theory wishes to explain how firms address the issue of governance by addressing the challenges of opportunism, uncertainty, and bounded rationality. Relational exchange theory focuses more on addressing the limitations of contractual governance which often is incomplete and leaves room for opportunism. From a relationship perspective, the theory provides a mechanism for how firms collaborate to ensure a sustained relationship. The institutional perspective is being added to this equation by addressing the issue of environmental differences when it comes to different institutional conditions.

Transaction cost analysis

Interfirm formal governance relations are often explored within the context of transaction cost analysis (TCA) (Rindfleisch et al., Citation2010) but when it comes to relational perspectives increasing attention has been on firm adaptation climate (Canevari et al., Citation2020) as well as understanding of cultural sensitivity (Voldnes & Kvalvik, Citation2017).

Bounded rationality, self-interest, and foresight have been the major assumptions behind TCA (Williamson (Citation2003). The assumption of feasible foresight ‘assumes that parties can foresee, detect hazards, establish the means through which they operate, and use these in the designing of governance’ (Williamson, Citation2003, p. 922). This third assumption means that the exchange partners can specify the unforeseen outcomes and establish the means for handling them. Kim et al. (Citation2020) suggested that the presence of specific assets especially from the supplier side, calls for the informal contractual governance.

TCA perspectives propose that a contract will be reflected by the key characteristics of the transaction. The most important characteristics are asset specificity, behavioral uncertainty, and environmental uncertainty. Asset specificity has been defined as the ‘durable investments that are undertaken in support of transactions, the opportunity cost of which investments is much lower in best alternative uses should the original transaction be prematurely terminated’ (Williamson, Citation1985, p. 5). When specific assets are not involved, we anticipate a sport-market transaction for which classical contract law would be used. If a transaction is composed of specific investments there is often a give-and-take (Jap, Citation1999). Asymmetrical investments made by one of the exchange partners may, however, lead to a lock-in position, and raise the possibility that the other party will behave opportunistically (Mesquita & Brush, Citation2008). Such asymmetrical specific investments lower the available legal protections (Argyres et al., Citation2007). It is also important to include the adaptability dimension in a contract—prescribing how the exchange partners should deal with problematic contingencies that could occur, can represent one mechanism of safeguarding (Jap & Ganesan, Citation2000). The specific asset in a relationship will often call for a safeguard, but due to challenges of bounded rationality, formal governance is not a sufficient mechanism that will ensure optimal safeguard of specific assets. In such a situation firms always turn to other alternative forms of safeguards such as relations. We expect that that prescence of specific assets will also enforce the need for adaptability much more in nations where formal institutions a weaker.

Environmental uncertainty has been defined as ‘unanticipated changes in circumstances surrounding an exchange’ (Noordewier et al., Citation1990, p. 82). Technological and volume uncertainty are the common ways of categorizing environmental uncertainty (Geyskens et al., Citation2006). Adaptation pressures arise from unpredictable environmental changes. Unexpected changes in the environment create a need to renegotiate the original contract, which involves increased transaction costs. Such renegotiations should be governed by a norm of flexibility, expecting that the parties will adapt to changing circumstances (Macneil, Citation1978) if the relationship shall continue fruitful (Gulati et al., Citation2005). If the exchange parties are anticipating high environmental uncertainty, it will be likely to include in the contract the procedures by which adaptations should be made, and shared expectations regarding future behavior. When there is no power imbalance the volume uncertainty generates the need for relational governance (Yang et al., Citation2021). Relational norms could, however, be opportunistically violated, especially when one of the transacting parties is in a lock-in condition due to unilateral specific investments (Wathne & Heide, Citation2000). Volume uncertainty creates the situation that demand flexibility between partners. Relationship partners need to have a need for high level of trust and understanding to be able to work with the situation which are highly dynamic. The effect of assets on the interfirm relationship is expected to increase when there is volume uncertainty. The pressure to ensure that the specific assets are safeguarded and the volume variations are met, will require partners to increase their level of collaboration. In structured markets where there is high degress of formal safeguard, such will not be sufficient to handle the challenges brought by volume variations and thus they will optimize the use of inter-firm relational adaptation.

Behavioral uncertainty is the uncertainty that may be present due to the opportunistic tendency of parties in the transaction (John & Weitz, Citation1988). Behavioral uncertainty thus results from the possibility for the ‘strategic nondisclosure, disguise or distortion of information’ by the transacting parties (Williamson, Citation1985, p. 56), thus leading to governance challenges.

Williamson (Citation1985, p. 79) matches behavioral uncertainty to different governance structures. According to this alignment of transactions and governance structures, the market is efficient for standardized transactions irrespective of the uncertainty, because economic actors can switch to another contracting party without a serious economic loss. When uncertainty increases, specific transactions are better organized in the hybrid form. When there is a larger degree of behavioral uncertainty, the match with the internal organization is more efficient

Relational exchange theory

Ralationships have always play a main role when it comes to alternative safeguard mechanism in inter-firm relations. Inter-firm conflict resolution (Shahzad et al., Citation2020) and costs saving can be achieved when firms have delveloped good relations. The researchers have shown that relational control (norm or personal relations) is often an effective means of governance as opposed to contracts (Dwyer et al., Citation1987). Relational exchange relies on relational contracts or norms (Macneil, Citation1980). These norms can be translated into behaviours such as consistency, flexibility, information exchange, mutuality, solidarity and replace or supplement more formal governance mechanisms such as contracts. Relational exchange is often characterized by high levels of cooperation, joint planning, and commitment and mutual adaptation to the partners’ needs in the exchange (e.g. Gundlach, Citation1994; Hallén et al., Citation1991). In the increasingly turbulent business market, firms look to build intensive relationships with their business partners to leverage the relationship-oriented governance mechanism (Geyskens et al., Citation1998; Macneil, Citation1980).

Macneil (Citation1980, Citation1981) identified several specific contracting norms and the most central relational norms are (1) the expectation of sharing benefits and burdens and (2) restraints on the unilateral use of power. Dwyer et al. (Citation1987), Kaufmann (Citation1987), and Kaufmann and Stern (Citation1988) provide an in-depth discussion of these and other norms. Opportunism under relational contracting means that particular relationship-specific contracting norms are being violated (Macneil, Citation1981).

Relational contracts may also address new circumstances, specifically where there is a need to update some dimensions of the relationship (Macneil (Citation1978) and Williamson (Citation1991a)). This process of updating changes in new circumstances in relational contracting is within the perspective of a norm of flexibility (Macneil, Citation1980; Noordewier et al., Citation1990). The norm of flexibility is the shared belief and anticipation that the parties will adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Parties may act opportunistically when showing inflexibility if the conditions call for parties to adapt (Anderson & Weitz, Citation1986). Rather than refuse to adapt, parties may use this opportunity to build a relationship by showing the willingness to adapt to the changing circumstances (Masten, Citation1988; Muris, Citation1981).

Relational factors are important in managing inter-organizational operational hazards (Shahzad et al., Citation2018; Wood, Citation2018) because they can be used as substitute for formal contractual governance especially in paces where institutions are weak. To any transaction which involve specific asset there is a particular degree of relationship. Such a relationship will often be driven by the level of assets and the context in which such a relationship takes place. The contextual elements of the relationship includes the institutional and specific operational forces such as volume and technological variations. We expect different institutional structures, volume and technological variation will have implication on the way the relational governance operates.

Institutional theory

According to Jackson and Deeg (Citation2008), institutional theory, which describes how an organization adopts practices that are considered acceptable within its organizational field, is widely used to understand business differences across nations. From this perspective, institutions can be described as ‘social structures that have attained a high degree of resilience’ and are ‘composed of cultural-cognitive, normative, and regulative elements (Scott, Citation1995, p. 33). New institutionalism provides a clear distinction between formal and informal institutions. According to Peng and Luo (Citation2000), formal institutions are represented by political rules, legal decisions, and economic issues. On the other hand, Estrin et al. (Citation2009, p. 1175) viewed informal institutions as ‘humanly devised constraints that are not formally codified but embedded in the shared norms, values, and beliefs of a society.

To investigate the impact of institutions, it is important to take a close look at the dynamics of formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions may have an impact on the formation of informal institutions. For example, culture provides a foundation by which formal institutions are developed (Holmes et al., Citation2011; Peng et al., Citation2008). On the other side, a contract including Inter-firm relational adaptability may promote common norms between the exchange partners.

The institutional climate is likely to differ between nations. Williamson (Citation1991) considers the institutional environment as a set of parameters—property rights, contract law, reputation effects, and uncertainty, and explored how changes in these parameters can impact the costs of governance.

In recent years there has been an increased focus on emerging markets. These markets have been described as ‘low-income, rapid-growth countries using economic liberalization as their primary engine of growth’ (Hoskisson et al., Citation2000, p. 249). The concept of emerging economies and transition economies have been used interchangeably, although transition economies often are used for the former communist countries in East Asia and Central and Eastern Europe (Meyer & Peng, Citation2005; Peng, Citation2003) and as such represent emerging economies. Empirical studies have found that business transactions in emerging economies to a large extent are based on relational exchanges building on mutual trust and cooperative norms (Gezhi et al., Citation2020, Liu et al., Citation2008), mainly due to a ‘lack of formal legal and regulatory frameworks, which are known as institutional voids’ (Zhou & Peng, Citation2010, p. 357). It has been suggested that as the formal markets that support institutions develop in these nations, there will be a shift from relational exchanges to arm’s length transactions (Peng, Citation2003; Zhou & Peng, Citation2010). Arm’s length transaction is a ‘rule-based, impersonal exchange with third-party enforcement’ (Peng (Citation2003, p. 280). Institutions influences how relationships are shaped and they also play a very essential role when it comes to alternative safeguard of inter-firm relations. Contextual factors such as power asymmetry and (dis)trust shape the way relations are formed (Adetoyinbo et al., Citation2023; Eckerd et al., Citation2021; Odongo et al., Citation2017; Owot et al., Citation2022).

The need for specific assets safeguard and flexibility in responding to fluctuations of technology and volume will often influence the way relational governance is organized. Specifically we expect that the weak formal institutional environment which is often found in less advanced emerging markets will call for a higher level of inte-firm relations. The technology variations often decrease the need for long-term relations but such a decrease is expected to be high in advanced emerging markets where level of technology development tends to be more dynamic and progressive. Volume variations on the other hand will call for long-term relations and flexibility and such a need will be relatively high in advanced/structured emerging markets because such high level of variations will also required a combination of both high safeguard and relations.

Research hypotheses

Buyer asset specificity and seller asset specificity

Specific investment of assets between supplier and buyer determines the course of governance but also defines the power balance of the relationship. Contextual factors such as power imbalance and (dis)trust influence how values are created and appropriated, as well as the relational and resource composition (Adetoyinbo et al., Citation2023; Eckerd et al., Citation2021; Odongo et al., Citation2017; Owot et al., Citation2022). When both buyer and supplier make specific investments there will be a mutual hostage (Williamson, Citation1985). This acts as a credible sign of each party’s commitment and may prevent both parties to behave opportunistically. Kim et al. (Citation2020) found the investment in specific assets especially on the supplier side to influence informal agreements. The need for elaborating contingencies and negotiating procedures and rules to be followed may be reduced because both parties expect a willingness to solve the adaptation problems when they occur. Accordingly, we expect bilateral specific investments to reduce Inter-firm relational coverage in the contract, compared to unilateral specific investments. Williamson (Citation1993) and Henisz and Williamson (Citation1999), suggested the need for transaction-specific safeguards (including contracts) to vary with the institutional environment within which transactions are located (Gezhi et al., Citation2020, Liu et al., Citation2008). Less structured emerging markets tend to have a high degree of informal and relational structures to support weak institutions (Zhou & Peng, Citation2010). Due to less developed formal legal and regulatory frameworks, we expect the effect of such reciprocal specific investments in reducing inter-firm relational adaptability to be greater in less structured emerging economies, than in more structured emerging economies. Thus:

Hypothesis 1a: The positive relationship between buyer asset specificity and Inter-firm relational adaptability will decrease with increased supplier asset specificity.

Hypothesis 1b: The positive relationship between buyer asset specificity and Inter-firm relational adaptability will decrease more in less structured than in more structured emerging economies, with increased supplier asset specificity.

Buyer asset specificity and technological uncertainty

Technology variations provides a critical challenge for adaptation within the framework of inter-firm relations, but its impact is often regulated by the conditions of asset specificity. As noted earlier, environmental uncertainty represents an adaptation problem, while asset specificity leads to a safeguarding problem. Empirical studies testing for interaction effects between asset specificity and environmental uncertainty have, however, provided mixed results (David & Han, Citation2004). Yang et al. (Citation2021) argued that environmental uncertainty affects relational adaptation when there is the absence of power imbalance, which is often generated by the absence of specific asset investment in a relationship. We will argue that there are important differences between environmental uncertainty caused by rapid technological development and environmental uncertainty due to fast-changing demand.

Suppose that the buyer has made extensive specific investments on behalf of the supplier and the relationship is confronted with high technological uncertainty. The supplier will ask for adjustments if the new technology can be more cost-efficient than the present one. The buyer will, however, face a safeguarding problem: If s/he makes new specific investments and the technological uncertainty still rests high, these new investments will soon be obsolescent. In other words, there will be a conflict between the need for adaptations and safeguarding. A high level of technological uncertainty combined with unilateral asset specificity may force the exchange partners to less hierarchical arrangements (Santoro & McGill, Citation2005). Buvik and Grønhaug (Citation2000) found that substantial asset specificity combined with high environmental uncertainty leads to less degree of vertical co-ordination in buyer-seller relationships. Poppo and Zenger (Citation2002) argue that exchange partners are less able to solve contract issues when specialized assets and technological uncertainty are present. We expect this effect on technological uncertainty to be stronger in advanced/structured emerging economies because such economies will wish to capitalize on a high level of formalization and less degree of adaptation. For the less structured economies, some degree of adaptation is tolerated because there is a tendency to take time before responding to technological changes as compared to the advanced emerging economies. Furthermore, based on the assumption of less technological stability in the more structured emerging economies, we propose:

Hypothesis 2a: The positive relationship between buyer asset specificity and Inter-firm relational adaptability will decrease with increased technological uncertainty.

Hypothesis 2b: The positive relationship between buyer asset specificity and Inter-firm relational adaptability will decrease more in the advanced structured than in less structured emerging economies, with increased technological uncertainty.

Buyer asset specificity and volume uncertainty

Previous studies have emphasized that the impact of volume uncertainty on governance mechanisms is conditioned by the level of asset specificity (Walker & Weber, Citation1984). When the buyer has made extensive specific investments, volume uncertainty is believed to be a more significant determinant of vertical integration due to the costs and possibilities for opportunistic behavior from the supplier (Sutcliffe & Zaheer, Citation1998). For instance, when re-negotiations of terms of trade are warranted due to peak demand, the supplier could claim extremely higher prices for goods delivered. The supplier could, however, agree upon including terms of trade under different demand conditions in the contract. From the supplier’s point of view, such terms would reduce the re-negotiation costs. Another reason could be set-up costs in case of establishing a relationship with a new buyer. A buyer who has made specific investments is likely to emphasize more on how demand volatility should be handled in the contract, than in a situation without specific investments. We predict:

H3a: The positive relationship between buyer asset specificity and Inter-firm relational adaptability will increase with volume uncertainty.

Hypothesis 3b: The positive relationship between buyer asset specificity and Inter-firm relational adaptability will increase more in structured emerging economies than in less structured emerging economies, with increasing volume uncertainty.

Research methods

Research context

Comparative research is a research methodology that aims to make comparisons across different social entities, including nations or cultures. The underlying goal of comparative analysis is to explore the insights from institutional influences on the governance mechanism. We are using ‘more structured’ and ‘less structured’ emerging economies for respectively Poland and Tanzania. This is done solely to indicate differences in the two countries’ development and level of institutional arrangements. We have followed the guidelines provided by Jowell (Citation1998) concerning comparative research methodology. First, we selected nations that we had some knowledge about. In other words, we used a purposive sampling method concerning the choice of the nations. Secondly, we limited the number to two countries. The two countries belong to different continents, which should ensure different environments. Thirdly, we have explicitly included analyses of contextual variables.

Based on a global competitiveness index, the report from World Economic Forum (Citation2020) categorize Tanzania to belong to Stage 1 (Factor-driven economy) while Poland is classified as transitioning from Stage 2 (Efficiency-driven economy) to Stage 3 (Innovation-driven economy). Concerning the formal/legal/regulatory framework, property rights and protection and juridical independence was better in Poland than in Tanzania. The extent of irregular payments/bribes was highest in Tanzania. Concerning the other pillars of competitiveness elaborated by the World Economic Forum, considerable differences (Poland more structured) were found concerning infrastructure, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, technological readiness, and market size.

In terms of culture, the dataset from Hofstede Centre (Citation2014) showed similar power distance in Tanzania (score 70) and Poland (score 68). Individualism is different between Tanzania (score 25) and Poland (score 60), indicating that Poland is more individualistic while Tanzania is a relatively collectivistic country. Masculinity indicated that Poland is a more masculine country (score 64) than Tanzania (score 40). Poland is considered to be a high uncertainty avoidance country (score 93) compared to the low uncertainty avoidance of Tanzania (score 50). Long-term orientation was quite similar between the two countries, indicating that both were relatively short-term oriented.

Sample and data collection

We used a survey of buying manufacturing firms with two different data collection methods for the two countries. The reason for this was based on differences in the two countries’ level of technological transformation: In Poland, 65 percent (%) of the inhabitants are using the internet, while in Tanzania there is only 13 percent (%) (World Economic Forum, Citation2020). SurveyXact was used to collect the responses in Poland. The advantage of this software is low cost, and that it provides fast responses. The firms were contacted by email, and if they indicated a willingness to participate, an email containing the questionnaire was sent to them via SurveyXact. The informants who completed the questionnaires were the supply managers or purchase managers of large firms and, for the small firms, the manager or someone with knowledge of the purchase function in the organization. Out of 1,800 firms initially contacted (taken from a 2011 directory of Polish companies), 400 completed the questionnaire partially and 201 fully, making the response rate (including the partially completed questionnaires) 33 percent (%). The partially completed questionnaires were not used because the amount of information missing was substantial. Thus, the final sample used for analysis was 201, with an effective response rate of about 11 percent (%).

We used direct personal contact in Tanzania based on the belief of a high preference for physical communication in this country (Molony, Citation2006). Firms were first contacted by phone before personal delivery of a paper-based questionnaires. Follow-ups were also made in person to collect the questionnaires, to ensure a higher response rate. The number of companies targeted was 750 (from companies listed in the Tanzania Revenue Authority, 2011). The final number of completed questionnaires received was 240 making a response rate of around 31 percent (%).

For both nations, we instructed the informants to select either the first, second, or third largest supplier in answering the questionnaire. This was done to control for potential biases caused by only choosing the largest supplier, but also to ensure that the selected relationship consisted of a supplier that the informant had good knowledge about (Rokkan et al., Citation2003).

Response bias is a common problem in survey studies. This study is prone to common-method bias because data were provided by the same respondents (Lindell & Whitney, Citation2001). We used Armstrong and Overton (Citation1977) procedure to test the extent of response bias, with an ANOVA test for subsamples of early and late responses in both countries. We also analyzed the sample by evaluating the survey’s extent of non-response bias as well as to see early and late respondents’ differences (Werner et al., Citation2007). No significant (p < 0.05) were found, although we admit that this procedure does not preclude response bias.

Measures

Questionnaire items were measured using a seven-point Likert scale. A list of the measures employed in this study is presented in the Appendix A, which also provides information on loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted for both countries. To ensure reliability, an exploratory followed by a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted. Most of the constructs used had been developed and tested previously in other studies, including the control variables. However, some of the measures had to be adjusted to fit the new context.

Inter-firm adaptability (ADAPT)

The measurement items are based on Luo (Citation2002), but we have added arbitration procedures and renegotiation periods. These items were added because we believe they may play an important part in an Inter-firm relational plan. Buyer asset specificity (BUASP) was adapted from Stump and Heide (Citation1996). The concept reflects the degree to which the buyer has specific assets involved in the relationship. It was measured using five items, reduced to three items for further analysis. Supplier asset specificity (SUASP) was measured using two items; based on Buvik and John (Citation2000). Technological uncertainty (TECHUNC) reflects the degree to which there are variations in technology or an inability to forecast technological requirements (Geyskens et al., Citation2006). The concept was measured with three items, mainly adapted from Anderson (Citation1985). Volume uncertainty (VOLUNC) reflects the degree to which volume requirements fluctuate or there is an inability to forecast (Geyskens et al., Citation2006). The concept was measured using two items, based on Buvik and John (Citation2000).

Control variables

The following controls that might impact the dependent and independent variables were included in the analysis. First, large firms may follow different procedures in outlining contracts; therefore we included firm size as a control. The second is the length of the relationship may have an impact on Inter-firm relational adaptability (Luo, Citation2002).

Invariance test

Testing for the equivalence of measures (or measurement invariance) has increasingly become important in cross-cultural research because it allows the researcher to assess whether the participants in different groups associate the same meanings to scale items (Fischer et al., Citation2009; Gouveia et al., Citation2009). Measurement invariance needs to be tested for cross-group comparisons (especially for mean comparisons); structural invariance is optional and researchers need to decide whether the further restrictions are theoretically meaningful (Milfont & Fischer, Citation2010). Models that test relationships between measured variables and latent constructs are measurement invariance tests. Four common models that fall into this category are: configural, metric, scalar, and error variance invariance (Milfont & Fischer, Citation2010). We follow the general succession of tests proposed by Vandenberg and Lance (Citation2000). Several are used to report results from structural equation modeling. We have followed the improved fit indices that are suggested by Hu and Bentler (Citation1999). Results from below are used to summarize the key results from the invariance test.

In the first step, we tested whether the proposed two-factor model fits the empirical data from each group (Poland and Tanzania). In each country we obtained two models; the freely estimated and constrained model. The freely estimated model for Poland [chi-square= 306 (df = 125, p < 0.000), NFI= 0.89, TLI= 0.91, CFI= 0.93, RMSEA= 0.085, PCLOSE = 0.000] and Tanzania [chi-square= 613 (df = 250, p < 0.000), NFI= 0.89, TLI= 0.91, CFI= 0.93, RMSEA= 0.06, PCLOSE= 0.003] performed poorly, while the constrained model for Poland [chi-square= 185(df = 122, p < 0.000), NFI= 0.93, TLI= 0.97, CFI= 0.98, RMSEA= 0.05, PCLOSE= 0.44] and Tanzania [chi-square= 371 (df = 244, p < 0.000), NFI= 0.93, TLI= 0.97, CFI= 0.98, RMSEA= 0.036, PCLOSE= 0.999] fitted well the data.

The second step was to move from single-group CFA (confirmatory factor analysis) to MGCFA (multigroup confirmatory factor analysis) to cross-validate the two-factor model across the two groups (Cheung & Rensvold, Citation2002; Jöreskog’s Citation1993; Steenkamp & Baumgartner, Citation1998). The results for MGCFA are provided in . Model 1 tested whether the proposed structure would be equal across the two groups. Configural invariance is tested by running individual CFAs in each group. However, even if the model fits well in each group, it is still necessary to run this step in MGCFA, since it serves as the comparison standard for subsequent tests (Milfont & Fischer, Citation2010).

The full configural model 1 constrained the factorial structure to be equal. As one could expect the constrained model was not supported in CFA, the same case appeared for MGCFA in model 1. The next stage was to relax the equality of factor loadings starting with the highest MI (modification index). The results indicated a significant improvement in model 2 (χ2 = 386.7; df = 256; χ2/df = 1.51; RMSEA = 0.036, TLI= 0.95; CF1 = 0.965) compared to model 1. This indicates that the factorial structure of the construct is equal across the two countries. As the configural invariance was supported, the factor pattern coefficients were then constrained to be equal to the test for metric invariance (Model 3). The results from model 3 indicated a good fitness (χ2 = 455.7; df = 269; χ2/df = 1.69; RMSEA = 0.042, TLI= 0.93; CF1 = 0.95). This suggests that the two countries responded to the items in the same way; that is, the strengths of the relations between specific scale items and their respective underlying construct are the same across the two countries.

The scalar invariance test (equality of intercept across the two countries) was conducted. The constrained model 4 was not supported. The next step was to release the equality of intercept constraints by starting with those items with the highest MI. There was the goodness of fit in the results from model 5 (χ2 = 531.3; df = 243; χ2/df = 2.2; RMSEA = 0.055, TLI= 0.88; CF1 = 0.92), suggesting a significant improvement compared to model 5. Support for scalar invariance indicates that the latent means can be meaningfully compared across the two countries. This scalar model is the last model necessary to compare scores across the two countries. All additional tests are optional (covariance, factor, and error invariance tests) and may be theoretically meaningful in specific contexts (Milfont & Fischer, Citation2010), however, in this study, we decided to do further tests so to enhance the justification for comparing the two countries.

We continued by testing the full factor covariance in model 6 by constraining all the factor covariance to be equal. The results from model 6, showed a poor goodness fit. In the next step, we tested for partial factor covariance by relaxing the equality of factor covariance constraint (in model 7). The results from model 7 had a good fit (χ2 = 342.2; df = 242; χ2/df = 1.4; RMSEA = 0.32, TLI= 0.96; CF1 = 0.97). This implies that all latent variables have the same relationship in the two countries. After establishing factor covariance, we constrained all the factor variance to be equal and tested the full factor variance in model 8. The results from model 8 did not show a good fit. In the next stage, we released the constraint on equal factor variance by starting with those factor variances with the highest MI. The results from model 9 had good fit (χ2 = 423.4; df = 263; χ2/df = 3.9; RMSEA = 0.039, TLI= 0.94; CF1 = 0.96). The results indicate that the range of scores on a latent factor does not vary across the two countries. In the next stage, we constrained all the error variances to be equal and tested for error variance. The results from model 10 showed a poor fit. We then released the equality of error variance constraint and the results from model 11 had a good fit (χ2 = 350; df = 251; χ2/df = 1.4; RMSEA = 0.039, TLI= 0.96; CF1 = 0.97). This suggests that the same level of measurement error is present for each item between the two countries. The results from the invariance tests suggest that the two countries can be compared.

Measurement validation

We assessed the adequacy of the measurement model through an examination of individual item reliabilities, convergent validity, and discriminant validity using Fornell and Larcker’s (Citation1981) approach. We tested for reliability using two mechanisms (Hair et al., Citation2012): First, we tested for the item-to-total correlation (should exceed 0.50 by the rule of thumbs) and inter-item correlations (should exceed 0.30) (Gotz et al., Citation2010). We deleted items with factor loadings smaller than 0.70. For the remaining items, we used Fornell and Larcker’s (Citation1981) internal consistency measure to check convergent validity. All factor loadings and construct reliability fulfilled the rule of thumb which requires construct validity and reliability to be greater than 0.50 and 0.70 respectively (Gotz et al., Citation2010). In testing for discriminant validity, we used Fornell and Larcker’s (Citation1981) criterion comparing the average variance extracted with the correlations among constructs. An inspection of and reveals that the diagonal elements of the matrixes are significantly higher than the off-diagonal elements, indicating discriminant validity.

Descriptive statistics

Results

Three regression models were used (). Model 1 (Poland: R2Adj = 0.26, F (195, 6) =12.3, p < 0.001; Tanzania: R2Adj = 0.26, F (234, 6) =12.2, p < 0.001) included the main effects.

Model 2 (Poland: R2Adj=.28, F (191, 10) =8.8, p < 0.001; Tanzania: R2Adj = 0.28, F (230, 10) =11.9, p < 0.001) interactive effects were added. Model 3 (Poland: R2Adj = 0.28, F (188, 13) =7.0, p < 0.001; Tanzania: R2Adj= 0.28, F (227, 13) =9.4, p < 0.001) added the control variables, the controls and, the main effects. The incremental R2Adj of M2-M1 (Poland: ΔR2Adj = 0.04, p < 0.10; Tanzania: ΔR2Adj = 0.01, p < 0.001) was significant but that of M3-M2 (Poland: ΔR2Adj = 0.01, p > 0.05; Tanzania: ΔR2Adj = 0.01, p > 0.05) was not significant.

Model 3 was used to report the results of the hypotheses. In addition to an independent sample t-test and z-test for regression coefficient to confirm whether there was a significant difference between the regression equations for the two countries.

To test for multicollinearity, VIF values were calculated and were in the range of 1.37–2.4, suggesting that the study does not suffer from multicollinearity problems (Hair et al., Citation2012). Generally, the dependent variable is different for the two countries but the conclusions will be based on the regressive model for z-test ().

The table below provides a comparative analysis of the regression weights observed between the two countries. We first provide the formula on how the Z-scores were computed. SEb - difference =

Thus; Z=

Where: bG1&G2 represent standardized regression weights (β) for group 1(Poland) and group 2 (Tanzania) respectively. SEb= Standard error

Effects

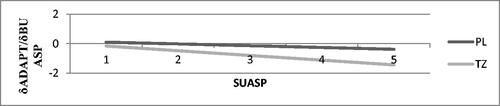

H1a suggested that the effect of buyer-specific assets on adaptability would decrease with supplier asset specificity. This hypothesis was supported ( and ) in Poland (β = −0.12, t = −1.88, p < 0.01) and in Tanzania (β = −0.31, t = −5.21, p < 0.01). H1b suggested that the effect of buyer asset specificity on adaptability would strongly decrease with supplier asset specificity in less structured than in the advanced structured emerging markets. This hypothesis was also supported by results from and , which indicate that the regression weights observed in H1a (Z = 2.40, p < 0.05) were significantly different in the two countries.

Figure 1. Effect of supplier asset specificity on relationship between adaptability and buyer asset specificity.

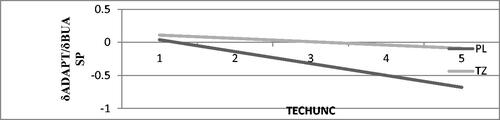

H2a suggested that the effect of buyer asset specificity on adaptability would decrease with technological uncertainty. This hypothesis was supported ( and ) in Poland (β = −0.21, t = −2.35, p < 0.01) but not in Tanzania (β = −0.06, t = −1.05, p > 0.05). H2b, which suggested that the effect in H2a would be stronger in advanced structured emerging economies compare to less structured ones, was also supported. The results from and , indicate that the regression weights observed in H2a (Z = −0.15, p < 0.05) were significantly different in the two countries.

Figure 2. Effect of technological uncertainty on relationship between adaptability and buyer asset specificity.

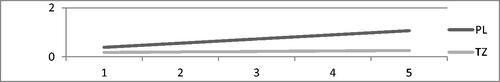

H3a suggested that the effect of buyer asset specificity on adaptability would decrease with volume uncertainty. This hypothesis was supported ( and ) in Poland (β = 0.17, t = 2.2, p < 0.01) but not in Tanzania (β = 0.04, t = −.68, p > 0.05). H3b suggested that the effect of buyer asset specificity on adaptability will strongly decrease in a more structured than in a less structured emerging market. This hypothesis was not supported. The results from and , indicate that the regression weights observed in H7a (Z = 0.61, p > 0.05) were not significantly different in the two countries.

Figure 3. Effect of volume uncertainty on relationship between adaptability and buyer asset specificity. NB: The interaction term was not significant in Tanzania.

The figures below describe the interactive effects observed for the two countries.

Discussion

It is generally understood that institutions influence inter-firm relations (Adetoyinbo et al., Citation2023; Eckerd et al., Citation2021; Owot et al., 2023) but the degree to which such influence is shaped across various institutional environments is missing in the literature. The concept of emerging markets which is applied in general terms to define the nations which are progressing towards maturity tends to be a general label but there are dynamics which are taking place within and across those markets. The close examination of 20 years of institutional shift in the two countries which are used in this study have indicated a quite dynamic institutional activities but most theories are developed with a static environment assumption. This study aimed at incrementing our understanding on the influence of institutional context and how it can influence interfirm relational adaptation using transactional cost drivers. In addressing the gap found in previous studies, this paper is brining the concept of advanced and less advanced markets within the framework of institutional variations of emerging markets.

From the transaction cost perspective, the general understanding is that there is a limitation in safeguarding assets and thus relational governace becomes important in dealing with transaction hazards (Shahzad et al., Citation2018; Wood, Citation2018).

When there is a presence of specific assets, there will be high incentives for structuring contractual governance with less degree of flexibility. The findings align with the view that relational adaptation responds to risk climate (Canevari et al., Citation2020) which tends to vary with institutional structures. The findings also suggest that when there is bilateral specific assets investment from both the seller and the buyer, parties will tend to provide high term-specificity and leave little room for flexibility. In other words, when specific assets have been invested, there is less appetite for adaptation, a situation that calls both parties to rely more on contractual governance. Findings from Kim and colleagues, 2020) suggested that supplier asset specificity improves the use of informal contracts while the use of formal contracts undermines the effect on the supplier. The authors also suggest that firms with weak ties with their partners in the network are more likely to use both formal and informal contracts than those with strong ties. These findings suggest the adaptation to be a one-sided specific investment (supplier side) as opposed to a bilateral form of investment.

When institutions are brought into perspective, the findings indicate that for the less structured emerging economies (which are highly volatile), there is a need for more emphasis on relational adaptation compared to advanced structured emerging economies which is relatively stable in terms of the institutional dimensions required for safeguarding contracts. Another explanation that would push for a high degree of relational adaptation in less structured economies is that there is more incentive for parties to resolve their differences compared to when such will be handled by other institutions such as courts because the time and cost burden can be enormous.

The effect of buyer asset specificity on relational adaptation has been found to decrease with technological uncertainty. This impact was stronger in advanced structured emerging economies compare to less structured ones. From the earlier argument, we have seen that the buyer asset specificity will require a significant degree of flexibility for the safeguarding mechanism. This is clearly understood from the fact that no degree of contractual specificity can overcome the loopholes of contractual governance. High technological variations will reduce the influence of buyer asset specificity on relational adaptation due to the risk of being trapped with old technologies. Technology variations tend to have advantages and disadvantages for both sides of the relationship Poppo and Zenger (Citation2002). For a buyer having a technological change, it means the opportunity to improve efficiency and lower cost. Other suppliers in the market may come up with good and alternative technologies and if the buyer is stuck with one supplier who may not be able to move with those changes, this can cause problems to the buyer. This is the reason that asset specificity when combined with technological variations will tend to harm relational adaptation. The best solution in this situation is to have short-term contractual agreements which will provide room for adjusting to the technological needs without much barrier in the process. We expect this effect on technological uncertainty to be stronger in more structured emerging economies because such economies will wish to capitalize on a high level of formalization and less degree of adaptation. For the less structured economies, some degree of adaptation is tolerated because there is a tendency to take time before responding to technological changes as compared to the advanced emerging economies.

Findings also suggested that the effect of buyer asset specificity on relational adaptation will decrease with volume uncertainty. There was no support that the effect will strongly decrease in a more structured than in a less structured emerging market. The same effect with technological variation was expected with the volume variation but when it comes to the national differences it is quite clear that the impact of technological variation is stronger than that of volume variation. The reason that we do not anticipate the variation of volume across the institutions is that this is one of the components of uncertainty that can easily be specified in contracts than other dimensions. Yang et al. (Citation2021) findings suggested that volume and technology uncertainty affects relational adaptation when there is an absence of power imbalances. Uncertainty (technological and volume) also decrease the effect of buyer asset specificity on adaptation, because of exposure to risks that appears to be out of control. These findings provide additional evidence from the observations made by Voldnes and Kvalvik (Citation2017) on the need to understand institutional sensitivity when conducting inter-firm relational studies.

Conclusion

Several studies have attempted to understand how relational governance is shaped by using general terms which may be limited in wider context. The aim of developing theory is to provide a generalized understanding. When it comes to inter-firm relational adaptation, the classical understanding is that institutions play a significant role in shaping how firms respond in dynamic environment. Often the dimension of culture in most of such studies is the one which is given an overall high attention. What has been missing from the current understanding is the degree to instituional variations influence inter-firm adaptation. Lables such as emerging markets has been used to infer a homogeneous group of markets which display similar characteristics. When such lables are taken for granted this could mislead our capacity to predict relational governance and we may also have limited explanation for variations found in such studies when performed across the various contexts. This paper has filled this gap by brining the concept of advanced/structured and less advanced/structured markets within the framework of institutional variations of emerging markets with the aim of understanding whether we will be able to find differences in predicting interfirm-relational. Our findings have clearly shown that such differences in emerging markets exist and they do influence

Limitations and future research

Study limitations

The study used a limited set of variables from transaction cost theory. Other variables from relevant theories can provide alternative explanations for the studied phenomena. Our approach to context did not render the analysis of individual institutional factors like culture. To do this it will require a dataset that involves two levels (individual firms and countries) variables. Further, emerging markets are composed of a heterogeneous and complex set of firms and institutions. Our approach provides elementary levels of studying the concept

Theoretical implications

The study has contributed to the understanding of relational governance within the contextual differences of institutions. Adaptation as a form of response to governance challenges will respond to the nature and context of interfirm relations. Often the international perspectives of governance are viewed from the dimension of culture, but we expanded this reasoning by including the institutional setup. From an economic perspective, nations can be clustered based on the stage of their development which is often found in the global economic reports of the world bank. From this clustering, some economies are efficiency driven as opposed to those that are effective-driven or in transition. Further studies can be done to explore how such differences in the economic stages could react to cultural differences.

Practical implication

The study has provided some thoughts on the need to consider the differences in the institutional structures when developing interfirm relational governance. For example; technology and volume variations are expected to play a dominant role such as the one the world has experienced recently. Continuous global changes are expected to be a norm. What needs to be addressed is not about how to avoid dynamics in environment, volume, or technology in an international context but how to devise resilient relational governance that can withstand such pressure. The study has provided food for thought along these lines. The most important note to take home is that the institutional differences can be challenging but can also be rewarding when parties understand how to careful examine and plan well in advance.

Implication for future research

Future research can examine the contribution of other theories and perspectives in explaining relational adaptation within the context of varying institutional setups. The interaction between the various institutional dimensions can also provide a rich source of knowledge in understanding the efficient relational governance modes that apply to different setups. The use of institutional-level data in the analysis can also give depth knowledge of the role of specific institutional variables. Most relations take time to evolve, future studies can use longitudinal-based analysis. This will capture the process and historical aspect of interfirm relational governance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emmanuel Chao

Emmanuel Chao is affiliated to Mzumbe University since 2007. He holds a PhD (from 2014) and Msc (International Business and Management) (2010) from Norway. He is currently a senior lecturer at Mzumbe University at school of business and he holds other senior positions in several enterprises. He is a chair for Tanzania marketing science association (www.tmsa.or.tz) and chair of CEOs and Scholars forums (www.csforum.co.tz). In his contribution to expand research and governance in emerging markets, Dr Chao is a founder and a chair of the international conference of business and management in emerging markets (ICBMEM)(www.icbmem.org). ICBMEM is an international academic networks which have representatives from Europe, Asia, Middle East and Africa. Apart from academics and research, Dr Chao is a regional coordinator for Tanzania institute of bankers and a General secretary of Efatha church, an international faith organization that have several projects, thousands of leaders and branches in Africa, Europe, Asia and North America. Dr Chao is currently an affiliate researcher at Agder University school of Business and Law in Norway, coordinator of doing sustainable business in Africa Program at BI-Norwegian Business School (Oslo Norway). Further, he is a coordinator for Sustain Project (sustainable business development and supply chain) that is coordinated by Jima University (Ethiopia), Mzumbe University (Tanzania) and BI-Norwegian Business School (Norway). Dr Chao has impacted hundreds of start-up organizations through the incubation and mentorship programs. Dr Chao has also coordinated the international start-up initiative with Fontys University of Netherlands where the students from Tanzania and Netherlands studied together remotely and leveraged the potential for international business networks. Dr Chao has also impacted about a hundred young business leaders through the annual young CEOs mentorship programs that he runs in partnership with senior CEOs. Through the television programs, Dr Chao has provided some insights on building sustainable enterprises to a wider group of stakeholders and organizations. Dr Chao has significantly contributed in building the professional marketing ecosystem in Tanzania by introducing the marketing awards and annual marketing congress, the programs which both recognize the best performers in the field of marketing as well as building up strong marketing leaders. Dr Chao has actively participated in leading academic platforms of his field such as Academy of Marketing (UK), European Academy of Marketing (Portugal, Slovenia), Marketing science/ World Marketing Congress (France), Info Marketing (USA), Society of Behavioral scientists (Canada), Industrial marketing Association (China), Business and information management (Japan), Achieving Youth Specific SDGs (India), Corporate Social Responsibility and Ethics (Norway) and several others. He has published several papers in a wide international outlets such as International Business research, Journal of Global marketing, Journal of business to business relations, Journal of knowledge management and practice, Journal of relationship marketing, International journal of Business and Management, International Journal of Business research and management and several others. Dr Chao has also provided consultation and research services to local and international organizations such as IIE (International Institute of Education) (funded by USAID), UNDP, IAGRI (USAID funding), Government of Tanzania and others.

References

- Adetoyinbo, A., & Mithöfer, D. (2023). Inter-firm relations and resource-based performance: a contingent relational view of small-scale farmers in Zambia. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-06-2023-0134

- Adetoyinbo, A., Trienekens, J., & Otter, V. (2023). Contingent resource-based view of food netchain organization and firm performance: A comprehensive quantitative framework. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 28, (6), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-11-2022-044

- Anderson, E. (1985). The salesperson as outside agent or employee: A transaction cost analysis. Marketing Science, 4(3), 234–254. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.4.3.234

- Anderson, E., & Weitz, B. A. (1986). Make-or-buy decisions: Vertical integration and marketing productivity. Sloan Management Review, 27(Spring), 3–19.

- Anderson, J. C., Håkansson, H., & Johanson, J. (1994). Dyadic business relationships within a business network context. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251912

- Argyres, N., Bercovitz, J., & Mayer, K. J. (2007). Complementarity and evolution of contractual provisions: an empirical study of IT service contract. Organization Science, 18(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0220

- Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377701400320

- Aubert, B. A., Houde, J. F., Party, M., & Rivard, S. (2006). The determinants of contractual completeness: An empirical analysis of information technology of outsourcing contracts.

- Brown, J. R., Dev, C. S., & Lee, D. J. (2000). Managing marketing channel opportunism: The efficacy of alternative governance mechanisms. Journal of Marketing, 64(2), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.64.2.51.17995

- Buvik, A., & Grønhaug, K. (2000). Inter-firm dependence, environmental uncertainty and vertical co-ordination in industrial buyer-seller relationships. Omega, 28(4), 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-0483(99)00068-7

- Buvik, A., & John, G. (2000). When does vertical coordination improve industrial purchasing relationships? Journal of Marketing, 64(4), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.64.4.52.18075

- Canevari, L. L. M., Berkhout, F., & Pelling, M. (2020). A relational view of climate adaptation in the private sector: How do value chain interactions shape business perceptions of climate risk and adaptive behaviours? Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(2), 432–444. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2375

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

- Craig, C. S., & Douglas, S. P. (2005). International marketing research. John Wiley & Sons:New York.

- Dachs, B., Kinkel, S., & Jäger, A. (2019). Bringing it all back home? Backshoring of manufacturing activities and the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies. Journal of World Business, 54(6), 101017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2019.101017

- Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (1996). Risk types and inter-firm alliance structures. Journal of Management Studies, 33(6), 827–843.

- David, R. J., & Han, S. K. (2004). A systematic assessment of the empirical support of the transaction cost economics. Strategic Management Journal, 25(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.359

- Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251126

- Eckerd, S., Handley, S., & Lumineau, F. (2021). Trust violations in buyer-supplier relationships: spillovers and the contingent role of governance structures. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 58(3), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12270

- Estrin, S., Hanousek, J., Kočenda, E., & Svejnar, J. (2009). The effects of privatization and ownership in transition economies. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(3), 699–728. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.3.699

- Fischer, R., Ferreira, M. C., Assmar, E., Redford, P., Harb, C., Glazer, S., Cheng, B.-S., Jiang, D.-Y., Wong, C. C., Kumar, N., Kärtner, J., Hofer, J., & Achoui, M. (2009). Individualism- collectivism as descriptive norms: Development of a subjective norm approach to culture measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(2), 187–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022109332738

- Fornell, C., &Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Geyskens, I., Jan-Benedict, E. M. S., & Nirmalya, K. (2006). Make, buy or ally: A transaction cost theory meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 519–543. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.21794670

- Geyskens, I., Jan-Benedict, E. M S., & Nirmalya, K. (1998). Generalizations about trust in marketing channel relationships using meta-analysis. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 15(3), 223–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8116(98)00002-0

- Gotz, O., Liehr-Gobbers, K., & Krafft, M. (2010). Evaluation of structural equation models using the partial least squares (PLS) approach. In V. E. Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Chin, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods, and applications (pp. 691–711). Springer.

- Gereffi, C., & Fernandez-Stark, K. (2011). Global value chain analysis: A primer. Center on Globalization, Governance and Competitivness (CGGC). Duke University.

- Gezhi, C., Jingyan, L., & Xiang, H. (2020). Collaborative innovation or opportunistic behavior? Evidence from the relational governance of tourism enterprises. Journal of Travel Research, 59(5), 864–878. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519861170

- Gouveia, V. V., Milfont, T. L., Fonseca, P. N., & Coelho, J. A. P. M. (2009). Life satisfaction in Brazil: Testing the psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) in five Brazilian samples. Social Indicators Research, 90(2), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9257-0

- Gölgeci, I., Gligor, D. M., Tatoglu, E., & Arda, O. A. (2019). A relational view of environmental performance: What role do environmental collaboration and cross- functional alignment play? Journal of Business Research, 96, 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.058

- Gulati, R., Lawrence, P. R., & Puranam, P. (2005). Adaptations in vertical relationships: beyond incentive conflict. Strategic Management Journal,26(5), 415–440.

- Gundlach, G. T. (1994). Exchange governance: The role of legal and nonlegal approaches across the exchange process. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 13(2), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569401300206

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

- Hallén, L., Johanson, J., & Seyed-Mohamed, N. (1991). Interfirm adaptation in business relationships. Journal of Marketing, 55(2), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252235

- Hendrikse, G., & Windsperger, J. (2011). Determinants of contractual completeness in franchising. In New developments in the theory of networks: Franchising, alliances and cooperatives (pp. 13–30).

- Henisz, W. J., & Williamson, O. J. (1999). Comparative economic organizations - within and between countries. Business and Politics, 1(3), 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1515/bap.1999.1.3.261

- Hewett, K., & Bearden, W. O. (2001). Dependence, trust, and relational behavior on the part of foreign subsidiary marketing operations: Implications for managing global marketing operations. Journal of Marketing, 65(4), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.4.51.18380

- Hofstede Centre. (2014). Cultural tools. Retrieved January 20, 2014, from http://geert-hofstede.com/countries.html.

- Holmes, R. M., Jr., Miller, T., Hitt, M. A., & Salmador, M. P. (2011). The interrelationships among informal institutions, formal institutions, and inward foreign direct investment. Journal of Management, 39(2), 531–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310393503

- Hoskisson, R. E., Eden, L., Lau, C. M., & Wright, M. (2000). Strategy in emerging economies. The Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 249–267.

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Jackson, G., & Deeg, R. (2008). Comparing capitalisms: Understanding institutional diversity and its implications for international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4), 540–561. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400375

- Jap, S. D. (1999). Pie-expansion efforts: Collaboration processes in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(4), 461–475.

- Jap, S. D., & Ganesan, S. (2000). Control mechanisms and the relationship life cycle: Implications for safeguarding specific investments and developing commitment. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.37.2.227.18735

- Jowell, R. (1998). How comparative is comparative research? American Behavioral Scientist, 42(2), 168–177.

- John, G., & Weitz, B. (1988). Forward integration into distribution: An empirical test of transaction cost analysis. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 4(2), 337–356.

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1993). Testing structural equation models. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 294–316). Sage.

- Kaufmann, P. J. (1987). Commercial exchange relationships and the negotiator’s dilemma. Negotiation Journal, 3(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1571-9979.1987.tb00393.x

- Kaufmann, P. J., & Stern, L. W. (1988). Relational exchange norms, perceptions of unfairness, and retained hostility in commercial litigation. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 32(3), 534–552. http://www.jstor.org/stable/174217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002788032003007

- Kim, M., Cho, H., & Ryu, S. (2020). The relationship between mutual TSI and interfirm contracts: The moderating effect of strong ties. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 27(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051712X.2020.1713566

- Liu, Y., Li, Y., Tao, L., & Wang, Y. (2008). Relationship stability, trust and relational risk in marketing channels: Evidence from China. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(4), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.04.001

- Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114

- Luo, Y. (2002). Contract, cooperation, and performance in international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 23(10), 903–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.261

- Macneil, I. R. (1978). Contracts adjustments of long-term economic relations under classical, neoclassical, and relational contract law. Northwestern Law Review, 47, 691–816.

- Macneil, I. R. (1980). The new social contract: An inquiry into modern contractual relations (pp. 134–137). Yale University Press.

- Macneil, I. R. (1981). Economic analysis of contractual relations: its shortfalls and the need for a ‘rich classificatory apparaturs’. Northwestern University Law Review, 75, 1018–1063.

- Masten, S. E. (1988). Equity, opportunism, and the design of contractual relations. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE)/Zeitschrift Für Die Gesamte Staatswissenschaft, 144(1), 180–195. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40751062.

- Mesquita, L. F., & Brush, T. H. (2008). Untangling safeguard and production coordination effects in long-term buyer-seller relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 51(4), 785–807.

- Meyer, K. E., & Peng, M. W. (2005). Probing theoretically into Central and Eastern Europe: transactions, resources, and institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(6), 600–621. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400167

- Milfont, T. L., & Fischer, R. (2010). Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.857

- Molony, T. (2006). “I don’t trust the phone; it always lies”. Trust and information and communication technologies in Tanzanian micro- and small enterprises. Information Technologies & International Development, 3(4), 53–66.

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252308

- Muris, T. J. (1981). Opportunistic behavior and the law of contracts. Minnesota Law Review, 65, 521–590.

- Noordewier, T. G., John, G., & Nevin, J. R. (1990). Performance outcomes of purchasing arrangements in industrial buyer - vendor relationships. Journal of Marketing, 54(4), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299005400407

- Odongo, W., Dora, M. K., Molnar, A., Ongeng, D., & Gellynck, X. (2017). Role of power in supply chain performance: evidence from agribusiness SMEs in Uganda. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 7(3), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-09-2016-0066

- Owot, G. M., Olido, K., Okello, D. M., & Odongo, W. (2022). Farmer–trader relationships in the context of developing countries: a dyadic analysis to understand variations in trust perceptions. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 13(4), 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-11-2021-0303

- Peng, M. W., & Luo, Y. (2000). Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 486–501. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556406

- Peng, M. W. (2003). Institutional transitions and strategic choices. The Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040713

- Peng, M. W., Wang, D. Y., & Jiang, Y. (2008). An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5), 920–936. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400377

- Poppo, L., & Zenger, T. (2002). Do formal contract and relational governance function as substitutes or complements? Strategic Management Journal, 23(8), 707–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.249

- Powell, W. W. (1990). Neither market nor hierarchy: Network forms of organization. In B. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 295–336). JAI Press.

- Rindfleisch, A., Antia, K., Bercovitz, J., Brown, J. R., Cannon, J., Carson, S. J., Ghosh, M., Helper, S., Robertson, D. C., & Wathne, K. H. (2010). Transaction costs, opportunism, and governance; contextual considerations and future research opportunities. Marketing Letters, 21(3), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-010-9104-3

- Rokkan, A. I., Heide, J. B., & Wathne, K. H. (2003). Specific investments in marketing relationships: expropriation and bonding effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(2), 210–224. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.40.2.210.19223

- Santoro, M. D., & McGill, J. P. (2005). The effect of uncertainty and asset co-specialization on governance in biotechnology alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 26(13), 1261–1269. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.506

- Shahzad, K., Ali, T., Kohtamäki, M., & Takala, J. (2020). Enabling roles of relationship governance mechanisms in the choice of inter-firm conflict resolution strategies. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 35(6), 957–969. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-06-2019-0309

- Shahzad, K., Ali, T., Takala, J., Helo, P., & Zaefarian, G. (2018). Thevarying roles of governance mechanismsonex post transaction costs and relationship commitment in buyer-supplier relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 71, 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.12.012

- Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Sage.

- Steenkamp, J.-B E. M., & Baumgartner, H. (1998). Assessing measurement invariance in cross- national consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(1), 78–107. https://doi.org/10.1086/209528

- Stump, R. L., & Heide, J. B. (1996). Controlling supplier opportunism in industrial relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 33(4), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379603300405