Abstract

This study investigated how youth in Community 8 in Tema, Ghana, used social media and how that affected their interpersonal and communication skills. The study used a combined framework of the Social Learning Theory and Media Richness Theory, as well as an exploratory descriptive design and a qualitative technique, to investigate how youth in Ghana’s Tema Community 8 perceive and use media. Thematic analysis was used to identify the main themes and patterns in the data acquired from a sample of 16 youths between the ages of 15 and 25 using semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and observation. Based on the findings of the study, for young people, social media is the preferred method of contact over face-to-face encounters. Some individuals believed that a more deliberate balance between digital and bodily interactions was necessary. When it comes to effects on the ability to communicate face-to-face, there is a reduction in abilities but some apparent advances in expressiveness. Comparing platforms, advantages included increased networks and innovation, but overuse led to social anxiety and distraction. The study demonstrates the need for parental mediation, digital literacy programs that enable youth to use technology intentionally and responsibly, partnerships between legislators, policymakers, and technology companies, and guidance and interventions to help young people be able to balance offline interactions with online interactions.

Introduction

The emergence of social media technology during the past 10 years has had a significant impact on people’s lives, especially the lives of young people. Social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, TikTok, and WhatsApp are now connected to how people develop their identities as well as their sociality, discourses, and peer connections (Shaw, 2020). While there are some advantages to using these applications, there are also some drawbacks, primarily in the form of negative psychological and developmental effects from heavy usage, particularly among vulnerable teenagers (Orben & Przybylski, Citation2019).

Although it is important to understand the multifaceted impacts of constant exposure to social technology, there is little information on non-Western cultures in the present literature (Wartella et al., Citation2021). According to Asare (Citation2022), the conditions are favorable in Ghana because young people are increasingly using social media and internet connection is widely available both in urban and rural areas. However, there is still a dearth of data on the results of this use. For the purpose of developing digital literacy policies and educational programs to advance skills, it is crucial to examine how social media usage affects Ghanaian adolescents’ communication abilities and competences.

Based on data from the Ghana Statistical Service (Citation2021), 89% of young adults between the ages of 18 and 35 are actively using social media platforms, up from 63% in 2015. This indicates that social media is widely accepted by Ghanaian youth. Additionally, the number of smartphones in use has doubled, resulting in widespread mobile access. In terms of the most popular social media sites, WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat stood out, with WhatsApp having the highest user penetration at 84%. There is also a gender viewpoint on social media use, with the men gravitating toward gaming platforms while the women favoured graphic platforms like Instagram (Owusu, Citation2022).

In Ghanaian universities, it is seen that over half of the students spend more than three hours every day engaging with social media platforms (Biney, Citation2022). Even though it has become more accepted, they continue to weigh the dangers and psychosocial benefits of them. Numerous research have looked into the effects of teenage social media use on their academic and developmental goals. While some participants reported perceived advantages such as relationships and social capital (Ampah-Mensah, Citation2021), other participants reported mental health problems, addictions, and declines in academic performance (Osei-Frimpong, Citation2019; Quaicoe et al., Citation2020). As a result, students consider social media technology to be a two-edged sword. Students in universities who spend more over five hours per day on social networking platforms, like Tanzania, tend to receive lower scores, but those who spend less than two hours do well (Lukonga, Citation2022).

Overall, the cause of increased anxiety and depression among university students is still unknown, whether it is due to isolation or psychologically to social pressures and influences (Baruah et al., Citation2022; Lukonga, Citation2022). According to a study, over 27% of university students in Ghana exhibit symptoms of social media addiction, including excessive misuse, preoccupation, and withdrawal when they can’t access the sites (Quaicoe et al., Citation2020). These individuals have less success with their academic endeavors and psychosocial integration. Similar to this, students who obsessively followed their friends’ feeds experienced unhappiness and stress due to their "fear of missing out" (FOMO) (Chinelo et al., Citation2022; Tandon et al., Citation2021). However, other studies have noted some psychological advantages of social media use, such as improved social skills, vocal presence, discovering identity, and self-confidence (Aidoo, Citation2021; Githinji & Mueke, Citation2020). Continuous screen use has been shown to replace physical exercise in terms of physical health, however there are few studies on this in the African context (Lewis et al., Citation2021). Other studies (Owusu-Appiah, Citation2022) noted that Ghanaian adults linked high social media usage to insufficient exercise, but further research is required to determine the impact on young people. In Ghana, young people use social media extensively, which shapes them as new trends emerge.

The usage of social media has both beneficial and negative effects on young people’s communication skills, according to the data (Baidoo & Baiden, Citation2020; Brink, Citation2021). Understanding the various facets is crucial since social media technology can promote the growth of young people both in Ghana and around the world. In order to fill important gaps, this study examined the complicated effects of social media on young people’s communication skills and competency in the understudied setting of urban Ghana.

Since it is becoming more and more popular, with over 4.2 billion users worldwide as of July 2022 (Pellegrino et al., Citation2022), particularly among young people, it is important to understand any negative effects it may have on their communication skills and general wellbeing. This is true even if there are some benefits that are ostensibly associated with its use. According to a number of studies, there is a complex relationship between social media use and communication skills among young people. For example, Baidoo and Baiden (Citation2020) in Ghana found that university students used social media for interpersonal communications because it was quick and convenient, but some of them found it uncomfortable to interact in person because of their constant social media engagement. Adu-Gyamfi and Brenya (Citation2020), Quaicoe et al. (Citation2020), and Osei-Frimpong (Citation2019) all noted significant levels of social media addiction that made it challenging for Ghanaian youth to have appropriate in-person contact. The National Communication Authority (Citation2020) issued a warning against Ghanaian youth using social media excessively because it was making them impulsive, despondent, and socially isolated. Mingle and Adams (Citation2015) and Nurudeen et al. (Citation2023), which found a link between excessive social media use and poor academic performance, divided attention, distraction, and decreased interest in academic work, support this.

There are many studies shedding light on the complex relationship between social media use and communication skills among young people in Ghana, but there is little information on how these problems affect young people in rural and underprivileged areas because most studies focused on urban youth in secondary and tertiary institutions. It will be valuable to learn how their social media use can affect their face-to-face communication and public speaking abilities using Tema Community 8 in Ghana, a less developed area with many youths who are school dropouts and unemployed but who use social media heavily. Less is known about that topic. Given that communication abilities are closely related to academic success, employability, and socioeconomic mobility, this knowledge gap is alarming. This study seeks to fill a significant gap in the literature by concentrating specifically on how social media affects young people in Community 8. The study specifically examined the relationship between communication competency markers as self-expression, social confidence, and face-to-face conversational abilities and interpersonal social media use against problematic addiction behaviour use. To achieve the purpose of this study, the following research questions guided the study?

What factors drive social media preference for interaction among the youth?

Are the youth employing social media to improve interactions?

Literature review

Social media usage patterns among youth

Social media, as defined by Kaplan and Haenlein (Citation2010), are internet-based platforms that allow users to interact, create, and share content. Examples include social networking sites like Facebook, microblogging services like Twitter, and content-sharing websites like YouTube. As of 2022, there will be more than 4.2 billion users of social media (DataReportal, Citation2022), especially among the youthful population (Anderson & Jiang, Citation2018).

It is widely used by young people in Africa, and studies have found that high school and university students in countries like Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya use social media the most frequently, with other research revealing trends in both their urban and rural areas (Sibanda, Citation2020; Umar & Mohammed, Citation2022). Even though social media is widely used, there are differences in usage between younger and older youth, males and females, and urban and rural locations. Age and gender so have an impact on how social media programs are used and preferred (Amoah, Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

In most studies, youth spend between two and four hours every day on social media platforms. This demonstrates active participation, but the pervasive nature raises questions about how they impact communication skills and competences. Studies have shown that social media has improved communication abilities, and some people in Ghana who used Facebook reported that their shyness was gone and they had confidence and self-expression (Aidoo, Citation2021). In a similar vein, Sibanda (Citation2020) found that in South Africa, 112 youths reported improved confidence as a result of online contacts, whereas fewer expressed decreased confidence as a result of social media interactions. According to the findings, Githinji and Mueke (Citation2020) found that undergraduate students’ high levels of confidence were a result of how simple it was to use digital spaces. While the aforementioned research revealed certain advantages, some have noted a deterioration in interpersonal and communication abilities. In 28 interviews with Ghanaian parents, Ankrah and Oduro (Citation2021) discovered that more than 50% of teens said that the prolonged use of social media had negatively impacted their linguistic and public speaking abilities. Le Roux and Chetty (Citation2022) also found that as teenagers’ use of social media increased, there was a corresponding decline in conversational competence, eye contact, and confidence when engaging in face-to-face communication. The longitudinal study followed the changes in social skills among 97 South African teenagers over a period of more than two years. They came to the conclusion that offline interactions were impacted by the online immersion. In a study of 100 Ghanaian high school students, Amoah (Citation2021a, Citation2021b) discovered similar results, concluding that regular usage of the WhatsApp app had negatively impacted the students’ ability to read nonverbal cues and listen to others during physical interactions. Githinji and Mueke (Citation2020) discovered that Kenyan undergraduates were proficient online communicators but struggled to comprehend gestures, facial expressions, and tone in person.

Students’ academic disciplines offer varied analyses on social media’s influence. Yeboah-Obeng and Kyeremeh (Citation2022) found that social media use in Ghana resulted in decreased English test scores and overall academic performance since so much time was spent on the sites. Similar to this, Lukonga (Citation2022) found in Tanzania that students’ grade point averages were lower for those who spent more than 5 h per day on social media than for those who spent fewer hours. Githinji and Mueke (Citation2020) state that the situation is the same in Kenya. Sibanda et al. (Citation2019) discovered that university students’ use of social media in South Africa caused distractions and had an impact on their academic performance. On the other hand, a study conducted in Nigeria revealed no connection between the use of social media and academic achievement (Okere et al., Citation2021). Numerous studies found a negative correlation between heavy social media use and superior academic achievement (Lukonga, Citation2022; Sibanda et al., Citation2019; Yeboah-Obeng & Kyeremeh, Citation2022). According to Sibanda et al. (Citation2019), despite the fact that social media offers easy access to learning opportunities, students struggle to balance these chances, which leads to misaligned priorities.

Social media has an impact on kids’ mental health in addition to their academic performance and communication skills. There are contradictory results in this field. There have been some reports of alleged advantages such increased social capital and support, higher social well-being, the growth of friendships, and increased confidence (Githinji & Mueke, Citation2020; Joubert & Suleman, Citation2022; Sibanda, Citation2020). Other research has documented depressive impacts of social media use, including increased anxiety, sleeplessness, loneliness, problems with body image, and peer pressure behaviours (Aidoo, Citation2021; Githinji & Mueke, Citation2020; Sibanda, 2019; Sunday et al., Citation2022).

Cultural differences in social media use and effects on communication skills among the youth in Africa

The relationship between cultural differences in individuality and power distance and social media communication methods was discovered through a comparison study of university students in Ghana and South Africa (Coleman, Citation2021). As they were more self-focused, open about their own opinions, and informal in tone regardless of audience, Ghanaians were perceived as more collectivistic with a higher power distance than the more individualistic, egalitarian South Africans. Ghanaian youth avoided dispute in online interactions with lecturers because of the high-power distance. South Africans freely debated academics. The authors came to the conclusion that different social media communication patterns and cultural orientations are related.

Researchers in Tanzania and Kenya looked at young people’s social media preferences via the cultural prism of masculinity and femininity (Juma & Kamere, Citation2022). Traditional gender roles, competition, and achievement are valued in masculine cultures like Tanzania while gender equality, teamwork, and quality of life are valued in feminine cultures like Kenya. According to research, Tanzanian youth preferred social media sites like Twitter that promoted political and news debates in line with traditional macho norms of rivalry. Youth in Kenya favoured platforms with a feminine slant, such Instagram and TikTok, which concentrated on relationships, lifestyle, and creativity. Each nation’s usage was also influenced by traditional gender expectations. This reveals how cultural values influence young people’s social media usage and communication styles.

Achebe (Citation2021), focusing on Nigeria, looked examined how disparities in collectivism and individuality between the Igbo and Yoruba ethnic groupings were represented in the usage of social media by young people. Youth social media use in the collectivist Igbo culture was primarily focused on preserving strong family and community ties. Social media provide channels for developing these connections. Online self-expression and self-presentation were prioritized by more individualistic Yorubas. Other people’s responses came second. While both groups used social media often, the ways they communicated differed based on their cultural perspectives.

Oládele et al. (Citation2022) investigated how social media affects communication skills over the course of a year among 14–16-year-old children with varying levels of individualism–collectivism in a rare longitudinal study in Nigeria. Social media increased opportunity and decreased incentive for interpersonal relationships outside of their community for collectivistic youth while strengthening social ties inside their own group. Their communication channels and capacities become more regional. However, through social media, individualistic teenagers expanded their social networks and enhanced their communication skills with a variety of groups (Kankam, Citation2023). The authors draw the conclusion that cultural values influence how social media either enhances or focuses on young people’s communication skills.

Sylla (Citation2022), looking at Senegal, examined social media communication abilities via the prism of high versus low context cultural variations. Senegalese culture places a heavy emphasis on environmental clues and implicit meanings in communication. The author discovered that high context kids had difficulty understanding complex social media messages lacking non-verbal clues, leading to misunderstandings. American children who were exposed to less context were better in gestural and contextual-free explicit online communication. It was proposed that the challenges of social media interaction will increase with high-context culture. Youth social media use in Rwanda, where there is a high degree of uncertainty avoidance, closely resembles traditional values and conventions, with online behaviours mirroring offline hierarchical relationships (Umubyeyi, Citation2021). Youth in Namibia showed higher exploration and identity experimentation on social media with lower adherence to conventions (Shihepo, Citation2023). Namibia has a low uncertainty avoidance rate. According to the scientists, youth communication patterns were impacted by social media deviance from norms due to degrees of uncertainty avoidance.

Omollo (Citation2022), focusing on time orientation, looked studied how young people use social media differently in Kenya, which has fixed time orientation, and Tanzania, which has fluid time orientation. Kenyan youth used social media for event preparation and took advantage of features like calendars and reminders. Tanzanian teenagers engaged in more impromptu networking on social media. Communication patterns reflect these divergent time preferences.

Theoretical framework

The study used a framework that combined elements of the Media Richness Theory and the Social Learning Theory. Albert Bandura created the social learning theory, which describes how people pick up behaviours, values, attitudes, and skills through imitating significant role models in their social environment (Bandura, Citation1977a). According to the social learning hypothesis, knowledge and skills are acquired through diligent observation and exposure to social models, which act as norms. An important framework for studying how increased social media use can affect adolescents’ interpersonal communication skills and competence is provided by the social learning theory. People learn relational skills primarily by imitating the behaviour of powerful people in their environment (Holland & Holland, Citation2018). The media richness theory, on the other hand, looks into how communication technologies and media vary in their richness, or their capacity to transmit sophisticated nonverbal and emotional elements. The capacity of the medium to convey social meaning depends on its richness.

The Media Richness Theory states that communication channels have a set of objective traits that establish their ability to transmit rich information and guarantee successful interactions (Daft & Lengel, Citation1986). For the objectives of this study, social media is mapped to the communication channel as described by the theory; hence, the theory is used to characterize social media’s capacity to convey rich information in order to promote its continuous usage to enhance interactions (Shim et al. Citation2007). Prior research has successfully applied this theory to examine the impact of media richness on social presence in online environments, such as social media (Ghosh et al., Citation2021; Ogara et al., Citation2014; Tseng & Wei, Citation2020).

Before developing observational learning, people went through a series of cognitive processes including attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation, according to the Social Learning Theory, which states that people perceive and interact with each other and reproduce behaviors observed during the communication process (Bandura, Citation1977b). This study used the theory’s definition of motivation—which is the willingness to imitate a behavior—to investigate the variables that led young people to use social media for interactions. It is noteworthy to mention that this theory has been extensively applied in previous research to comprehend how people use social media for interactions and other behaviors (Hoffner & Buchanan, Citation2005; Le & Hancer, Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2013)

A useful combined framework for examining the effects of intense social media use during critical developmental phases on the development of holistic communication skills and interpersonal competence among adolescents and young adults was created by integrating key elements of the theories of social learning and media richness.

Methodology

The study used a qualitative approach and an exploratory descriptive design to examine how young people in Tema Community 8, Ghana, utilize social media in connection to their motives, difficulties, and effects on interpersonal communication skills (Kankam, Citation2020). The qualitative approach, according to Creswell (Citation2022), is important for understanding people’s experiences and the meanings they assign to behaviours and social problems. Due to the paucity of earlier research on this topic in the particular setting of Community 8, a low-income urban area in Tema with significant unemployment, school dropout rates, and poverty, an exploratory descriptive approach was utilized (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021).

Although 22 respondents were selected for the study through convenience sampling to satisfy the study’s inclusion requirements, ultimately, 16 participants were actively involved, and the other 6 respondents were not interviewed. This adjustment occurred because, after the ninth person was interviewed, which included an initial focus group discussion with seven individuals (Appendix 1) that yielded a great deal of detailed information, saturation was reached. Consequently, the 6 remaining participants received gratitude for their agreement to participate in the study. According to the theory of saturation, a stage known as saturation happens in qualitative research and warns researchers about the prospect of ceasing data collecting when no new information is found from the data and the same discoveries keep coming up (Kankam & Baffour, Citation2023).

With the use of 16 young people in Tema Community 8 between the ages of 15 and 25 as participants, data were gathered through the use of semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and observation. The semi-structured interview format meticulously included open-ended responses, which allowed participants to express their views and experiences in depth, while still guiding the conversation towards the key research questions, ensuring both the richness of qualitative data and its relevance to the study’s objectives (Owusu & Kankam, Citation2020).

Through peer interactions and self-discovery, adolescence and the early years of adulthood are crucial times for establishing interpersonal competence (Steinberg, Citation2020). Tema Community 8 is expected to have around 5000 youth, although the focus was on those aged 15–25. To choose the individuals who satisfied the inclusion criteria and were available, a convenience sample procedure was used. Prior to participating in the study, the participants were asked for their informed consent. Before any participants under the age of 18 entered the study, their parents’ permission was obtained. The participants were given additional information and were able to leave the study at any time. While focus groups revealed shared perceptions and norms and observation provided additional contextual information about social media use behaviour and communication dynamics, semi-structured interviews were helpful in obtaining the participants’ detailed, personalized use of social media patterns, influences, and communication experiences (Shaw, Citation2022).

The impact of the participants’ social media interactions on their conversational, public speaking, and interpersonal competency was examined using thematic analysis to identify relevant patterns and meanings. Text passages linked to each theme were categorized into categories in the transcripts (Williams & Moser, Citation2019). We looked for broad trends in the codes’ analysis of usage motivations, problematic behaviours, benefits and challenges of related skills, mediating factors, and variations by age and gender. The accuracy of the interpretations was confirmed among the participants. The NVivo analysis software was employed to improve and visualise the presentation of the results.

Results

Following a thematic analysis of the participant data, five main themes were found. According to the data analysis, there were nine (56%) male participants and seven (44%) female participants. Participants were assigned a G1 through G16 code (see Appendix 1)

RQ1: What factors drive social media preference for interaction among the youth?

There must be some underlying elements that motivate young people to use social media more frequently. Due to their accessibility and convenience, they have become the norm for communication and have largely replaced face-to-face contacts, according to the study’s findings. A small number of participants, meanwhile, were conscious of their propensity to rely too much on technology-mediated communication and stated a wish to strike a better balance with meaningful face-to-face encounters.

For me and most of my friends, it’s just so much easier to use social media like WhatsApp or Snapchat all the time to chat instead of seeing each other face-to-face. You can send messages, reactions, photos, videos, anything really, whenever it’s convenient for you on social media. You don’t have to coordinate schedules or make time to actually meet up in-person like you do with face-to-face hangouts. Social media allows you to have conversations on your own schedule, like when you’re commuting or lying in bed at night. It takes extra effort to physically get together with friends, whereas on social media you can interact casually whenever - it’s always available. That constant accessibility makes social media the convenient choice most of the time over in-person hangouts for me and my peers. (G8, 20 years, male).

I’ve really realized just how frequently I end up casually interacting with friends on different social media platforms like Snapchat or Instagram without even consciously thinking about it. Chatting via social media has become such an automatic habit for me instead of talking face-to-face during school or intentionally arranging to meet up somewhere in-person. It’s so easy to just send funny videos, respond to stories, post updates, and have conversations through messaging or group chats rather than making plans to see each other offline. The seamless, informal flow of connecting through social media apps like WhatsApp is always available right at my fingertips. So more often than not, I default to those digital options without considering taking the extra steps to interact in-person. Social media is so conveniently interwoven into my daily routines as a main way to communicate that I engage with it on autopilot at this point. (G5, 21 years, male).

One of the main advantages I see of interacting through social media versus face-to-face is that it allows me to have an ongoing, continuous conversation in our Instagram group chat or DM [direct message] my friends anytime about random thoughts or quick updates. That keeps us perpetually connected in the loop about each other’s lives. It’s not as logistically convenient to physically see all my school friends every day outside of class to have the same level of constant communication. Social media provides a channel where I can get rapid responses, share things as they happen, and stay in touch regularly at a high frequency that would be a lot harder to maintain just talking in-person. Having that constant connectivity through the digital platforms makes them much more convenient for frequent conversations and close contact with my friend group. (G2, 20 years, female).

Lately I’ve noticed that I often catch myself mindlessly scrolling and messaging friends for long stretches of time throughout the day on social media instead of taking some of those interactions offline by actually talking with them face-to-face at university or over a phone/video call to have a real two-way conversation. The constant non-stop availability of connecting through social platforms makes it so easy to just passively react to posts and fall into drawn-out digital chatter versus proactively initiating quality catch-up time in-person or over voice/video chat. While social media definitely makes casual communication convenient, I think it’s important I don’t let it fully replace more meaningful, engaged human interactions. Moving forward, I want to be more intentional about balancing my social media contact with in-person hangouts and deep talks on the phone to nurture my close friendships. (G11, 21 years, female)

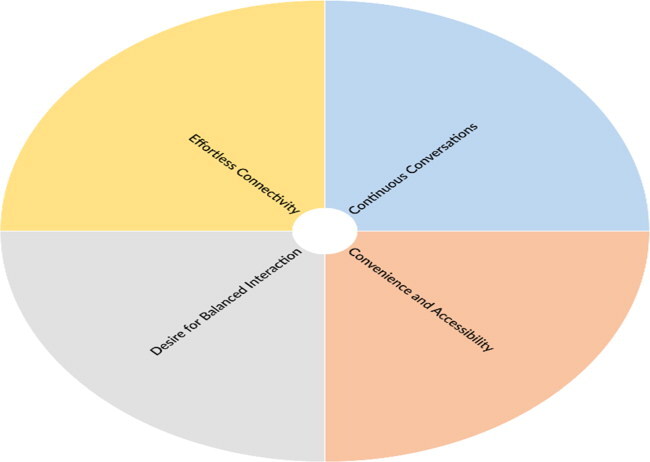

Through the use of NVivo 14, the pie chart below provides a summary regarding the first research question based on the analysed data

RQ2: Are the youth employing social media to improve interactions?

Perceived impacts on face-to-face conversational competence

Overuse of social media has been linked to decreased face-to-face talking skills. The study sought to understand how it affects the participants, and it was discovered that a large percentage of youth unmistakably believed that regular, heavy usage of social media had harmed their ability to converse. They discussed how early exposure to technology-mediated communication had altered early social norms and expectations in ways that made face-to-face interactions uncomfortable. However, a number of the participants were of the opinion that using particular social media platforms had improved their confidence in speaking with others, especially in group settings. Overall, youth overwhelmingly shared that constant digital immersion had led to noticeable declines in core social skills required for successful face-to-face interactions, such as reading non-verbal cues like tone and body language, listening attentively without interruptions, expressing empathy, and reciprocating conversation in a balanced back-and-forth flow. However, a small group of participants believed that specific types of social media use strengthen these skills.

I’ve realized that I’ve gotten so habituated to short snippets of messages, reactions, memes, and quick video clips on platforms like WhatsApp or TikTok that I’ve lost some fluency for longer, more detailed real conversations face-to-face. My speaking vocabulary feels more limited and I struggle with how to keep an in-person discussion flowing. I end up relying a lot on short responses rather than reciprocating meaningfully. When I’m expected to have a full back-and-forth conversation in-person, especially with people I’m not super close with, I don’t know how to hold my end naturally anymore. The predominantly non-verbal forms of constant micro-communication on social media have degraded my skills for engaged verbal interactions in real life. (G3, 17 years, male).

After growing up engaging on highly visual platforms like Snapchat and TikTok every day for years, chatting via text, emoji, filters, and playful photos just feels significantly more normal to me than talking face-to-face for an extended interaction. When I’m in a situation now that requires having a full verbal conversation in-person, I immediately feel some nervousness creep in because I’m just not habituated to that mode of communication like I am with social media. The thought of having to sustain a real back-and-forth conversation feels foreign compared to the short casual commenting I’m used to online. I think my constant daily use of visual dominant social media since I was young has made me lose some fluency with in-person interactions because it’s outside my comfort zone of communication. (G9, 17 years, female)

I think interacting extensively in fast-paced group conversations about trending topics on platforms like Twitter and TikTok has actually helped me become more confident when talking or presenting in front of my classmates. Composing interesting tweets, funny memes, and engaging TikTok videos requires creatively capturing an audience’s attention and reacting quickly. Learning those skills from actively participating in online groups has boosted my abilities to contribute thoughts spontaneously when we have roundtable discussions in my college courses. My classroom participation has improved because I learned how to read groups, inject humor appropriately, and connect with audiences through trial-and-error on social media. While social technologies can have downsides, I believe immersing myself in Twitter and TikTok specifically has strengthened my public communication and interjecting abilities in face-to-face group settings. (G15, 19 years, male)

We don’t get as much practice with real social skills anymore because so much happens online. (G2, 20 years, female)

Benefits versus risks of social media use

Many participants expressed serious concerns about the risks they perceived from excessive use of social media, including declines in communication abilities and face-to-face relating skills, distraction and time displacement from academic work, while others cited a variety of perceived benefits, including expanding social networks, convenience, creativity, and access to entertainment and information. Most participants conveyed a nuanced perspective in weighing the pros and cons, acknowledging both the benefits of social media for entertainment, self-expression, and social connections as well as the risks of potential overuse, including distraction from priorities, declines in vital face-to-face communication abilities, increased depression and anxiety, and relationships harmed by miscommunication.

One of the main benefits I see of social media is that it allows me to connect with a way wider range of people from different schools, cities, or even different countries based on shared interests. I can directly share my rap songs and lyrics easily online via Instagram or YouTube to collaborate and build my music profile in ways that wouldn’t be possible offline. That helps me express my creativity and gives me access to a big audience. I also follow sports highlights and funny videos from so many channels on apps like YouTube and WhatsApp that I would never regularly watch on traditional media. So I think social media enables convenience through doing a lot on my phone instantly, plus it lets me be creative and reach a broader audience. (G1, 18 years, male)

One of the biggest downsides I’ve realized from my high social media usage is that I end up aimlessly browsing different apps on my phone for hours, which eats up a lot of time during the day that I should be spending on schoolwork or being present with people around me. I’ve noticed my grades dropping over this past semester because I’m constantly getting absorbed into mindlessly scrolling Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, and YouTube when I should be studying, doing assignments, or even just having real conversations with roommates. Social media draws me into this addictive digital loop that distracts me from everything else going on. I know my overuse of it has started to negatively impact both my studies and my personal life. (G7, 22 years, male).

One psychological challenge I’ve noticed is that being on apps like Facebook and Instagram a lot ends up exposing me to all these perfectly staged photos projecting how awesome and beautiful everyone’s lives are. But I logically know those are idealized highlights, not real. Still, seeing images of people travelling, partying, and just looking perfect all the time makes me start negatively comparing myself and feeling bad that I don’t measure up, even though it’s an illusion. Social media selectively amplifies the positive while hiding the normal struggles. Consuming all that causes me to often feel inadequate or like I’m missing out because my own life doesn’t seem as glamorous. The inevitable social comparison that comes with seeing those curated projection feeds definitely breeds anxiety, insecurity, and sometimes even depression. (G6, 18 years, female)

One negative aspect of overly relying on social media for communication that I’ve noticed is that there tends to be lots of unnecessary, exaggerated drama that gets sparked online but wouldn’t happen as much face-to-face. When you can’t hear someone’s vocal tone or see their facial expressions, it’s easy for text messages to be misconstrued based on whatever mood the receiver is in. Then it spirals into a whole back and forth controversy because subtle meanings got lost over text. I’ve seen friendships strained because sarcasm got interpreted as being serious through messages or a harmless joke caused offense since the tone didn’t come across. Lacking those non-verbal cues on predominantly text-based social platforms definitely fuels miscommunication that damages social relationships unnecessarily. (G16, 17 years, female).

The Central role of smartphones

The majority of participants named smartphones as the crucial gateway technology that allowed constant access and significantly influenced their communication norms and behaviors when asked what facilitated their high-frequency social media habits. Other young people spoke about how having a smartphone that can access the internet and run apps drastically changed peer relationships. However, a few participants described making an attempt to control their smartphone use more deliberately by turning off distracting alerts during study hours and making a conscious effort to put their phones away when engaging in face-to-face social interactions.

The main reason social media is such a big part of my life is that having constant access to the internet and apps through my smartphone means I can use it 24/7 easily. Social media is always right there in your pocket. (G4, 19 years, female)

I remember when I first got an iPhone a couple years ago it completely changed my social media use. I went from only checking Facebook every once in a while on my old phone to being on apps like TikTok and Twitter way more regularly throughout the day, just because they were always readily available on my new smartphone. It became a habit to scroll through feeds or share content whenever I had a free minute. So, I think smartphones are the real game-changer that enabled social media to become a dominant part of my communication because the constant connectivity makes it so easy to use all the time. (G12, 18 years, male).

Now that all my friends have smartphones in their pockets, I’ve noticed when we hang out together the whole group still spends a lot of time distracted on our own devices even when we’re physically together. People don’t engage as intently with the conversations or activities happening in real-life because they’re preoccupied checking the endless stream of updates and responding to messages on various social media apps. It’s ironic but also kind of sad that the technology that enables us to communicate virtually anytime also ends up disrupting communication when we’re face-to-face because everyone stays glued to their phones. The ubiquitous smartphones diminish real presence. (G2, 20 years female).

I started turning off all app notifications except for calls and texts so I check it less reflexively. And I try to put my phone away more when hanging out live. (G8, 20 years, male).

Gender differences

There are certain gender disparities in how young people perceive and experience how social media use affects their communication abilities and proclivities. A recurring concern among young women was feeling more pressure on their appearance as a result of social media’s constant exposure to idealized representations of female beauty and the prominence of visual self-presentation on websites like Instagram. The males, on the other hand, talked about how their real-world social interaction and presence decreased as a result of becoming overly engrossed in sports, gaming, and entertainment content on websites like YouTube, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Twitch. The pathways diversified based on gendered incentives and demands, despite the fact that both young men and women reported losses in certain social competences including sustaining concentration and reciprocity in talks due to excessive technological immersion. Some participants, however, also made the obvious observation that gender-specific motivations vary and that overt stereotypes frequently simplify complex reality, both online and offline.

The popularity of image-focused apps like Instagram means I’m constantly seeing flawless photos of models and influencers looking perfect, as well as all my friends posting their best selfies and outfit pics. Even though I know those are the highlights, not reality, being surrounded by so many hot girls on social media makes me obsess over my own looks and whether I measure up. When I’m interacting face-to-face with guys at school or even just friends, I get super self-conscious about my appearance because of beauty pressures from the perfect images all over my social media feeds. It’s really hard to stay focused on the actual conversation when I’m preoccupied worrying about how I look after seeing endless ‘pretty’ on Instagram. (G6, 18 years, female).

As a huge basketball fanatic, I follow and watch so many sports channels, analysts and athletes on YouTube that I sometimes end up going down an endless rabbit hole of game highlights and call-outs even when I’m physically hanging out with friends. The non-stop stream of sports content online is addictive. My guy friends share lots of funny sports videos and debate players on Twitter or WhatsApp too, so we end up showing each other posts and getting caught up in that digital world rather than being fully present in whatever we’re doing together offline. Our shared obsession with athletes and teams on social media pulls us into our phones even during in-person hangouts. (G14, 20 years, male)

There are feminine guys and masculine girls whose interests don’t fit assumptions. (G2, 20 years, female).

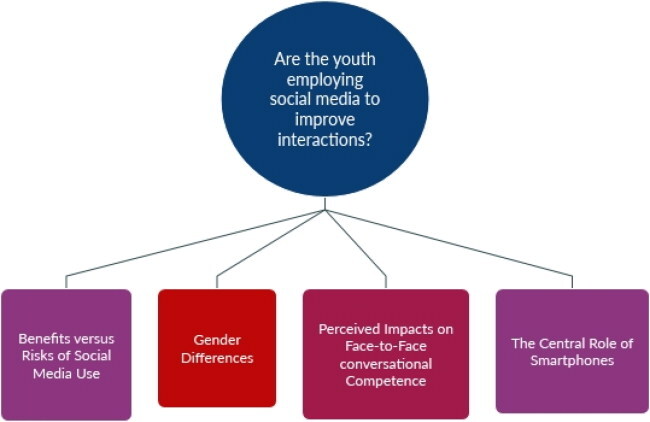

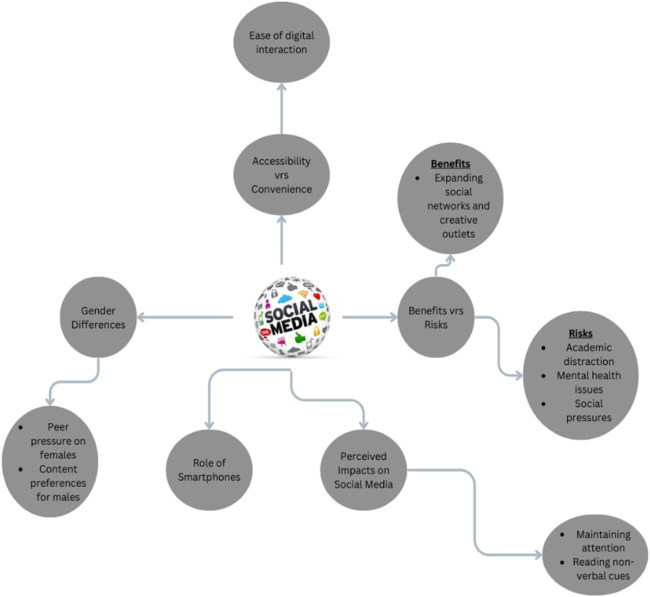

The mind map above was developed based on findings from data analysed through the use of the NVivo 14. The map presents a summary of the second research question based on the generated themes from the data analysis

Summary of findings

The findings demonstrate how social media’s ease of use and 24-h availability influence its preference over face-to-face encounters. In addition, the findings highlight worries about the reduction of face-to-face conversational skills as a result of over reliance on social media. The findings also raise concerns about the social connectivity and creative expression options that social media provides versus its downsides, such as distraction and the influence on mental health. The findings also stress smartphones as a portal to constant social media access and their consequences on communication norms, as well as how social media use and perceived impacts varied between genders, with a focus on pressures and content engagement patterns.

Discussion

This qualitative case study investigated how young people between the ages of 15 and 25 in the underprivileged urban community of Community 8, Tema, used social media to improve their communication skills and competency. The main goals were to determine what influences youth’s choice for social media engagement over face-to-face interaction, how to increase youth’s communication skills for in-person interacting, and how youth perceive social media compared to face-to-face interaction.

The motivation element of the Social Learning Theory guided the study in looking into factors that drive the use of social media among the youth for interaction. Convenience, accessibility, and habitual use dominated the factors that influenced social media use for interaction among the youth. This collaborates the findings of Al-Menayes (Citation2015), Kircaburun et al. (Citation2020), and Balakrishnan and Gan (Citation2016). The constant accessibility of connecting through apps on cellphones draws interaction into the digital world, as Acheampong (Citation2021) discovered in Ghana. Youth explained how social media made it possible to stay in touch with pals perpetually, wherever they were, without having to arrange meetings in person or coordinate schedules. Digital engagement has become the default, more practical option over in-person discussion thanks to mobile technology’s seamless integration of social networks into daily routines. According to research by Owusu-Acheaw and Larson (Citation2015), accessibility and convenience are the main factors luring Ghanaian adolescents to social media over face-to-face encounters. Similar findings have been reported by studies conducted in various African nations, with face-to-face interaction being replaced by the portability of mobile social media (Sibanda, Citation2020). As highlighted in previous studies by Décieux et al. (Citation2019) and Hampton et al. (Citation2017), some young people did, however, indicate a desire for a better balance between online and offline interactions, revealing their understanding of the dangers of choosing convenience above effective communication.

The Media Richness Theory was employed to ascertain whether the youth were employing social media to improve interactions. Based on this theory, ability of a channel (in this case social media) to convey rich information will ensure effective interactions. As to increasing in-person proficiency, it was widely believed as found in the analysed data that intensive social media use was linked to deteriorating skills. This finding aligns with Dhir et al. (Citation2018), who pointed out not only that intensive social media use can lead to the deterioration of users’ skills but also may contribute to depression. The majority of young people who participated in the study talked about how being constantly immersed in technology led to less time spent connecting with others in person, which produced uneasiness and deficits in speaking in person, especially with those who weren’t close friends. This finding complements the findings of Twenge et al. (Citation2019). According to their study, as social media usage increases, in-person social interactions decline. Reading non-verbal clues, paying attention without becoming sidetracked, demonstrating empathy, and maintaining reciprocal conversation flow were major areas of difficulty. According to Baidoo and Baiden (Citation2020), frequent social media users have trouble using their digital skills in real-world settings. Similar trends of teens using too much technology to replace face-to-face interactions and impair their ability to communicate holistically are documented throughout Africa (Brink, Citation2021; Mensah, Citation2021; Sibanda, Citation2020). Participants in this study made clear the need for further instruction on how to balance technology use with deliberate face-to-face contacts to preserve key abilities. Peer modelling of effective communication and a decrease in repetitive digital behaviours were advised. This is consistent with Aidoo and Boateng’s findings from 2022 about the preferred methods for satisfying teenagers’ desire to become more competent (Aidoo & Boateng, Citation2022).

On perceptions of social media versus in-person communication, views from the participants were mixed. Self-expression, widened networks, and creative chances were among the advantages mentioned, as also highlighted by Ogibi (Citation2015) and Choi and Sung (Citation2018). But frequent use led to apathy toward offline encounters. The patterns of Owusu-Acheaw and Larson (Citation2015) Ghanaian study are mirrored in these intricate conflicts between risks and benefits. The risks mentioned here, such as social comparison pressures escalating anxiety and broken relationships due to online miscommunications, replicate widespread worries expressed in Africa (Githinji & Mueke, Citation2020; Joubert & Suleman, Citation2022). Overall, young people maintained complex viewpoints, respecting social media’s benefits but also acknowledging how unchecked use can harm mental health, relationships, and interpersonal skills. This is consistent with a Kenyan study by Omollo from 2022 that demonstrates advanced trade-off evaluation. The pressing need for greater social media literacy was confirmed by research from South Africa (Sibanda et al., Citation2019). When the major trends in this sample are combined, it is possible to infer that excessive passive social media use during these critical developmental years increases the likelihood of communication skill decreases and psycho-social issues. Active participation combined with academic and social priorities, however, may have advantages. For instance, Talaue et al. (Citation2018) highlights that young people can interact with their colleagues and discuss issues relating to their studies. The difficulties however, highlight how crucial it is for future study to evaluate dosage effects and set sensible usage guidelines in order to optimize benefits and reduce risks.

Additional information regarding modern youth experiences with social media and communication in the underprivileged urban Ghanaian setting emerged from the qualitative data. Young women reported stronger appearance-focused motivations and demands on visually dominant platforms like Instagram that induced anxiety. This finding was also highlighted by Perloff (Citation2014), who indicated that social media can influence the perceptions of body image especially women. Gender disparities reflected some existing societal norms. Young males spoke of being lost in online sports, gaming, and entertainment material rabbit holes that diverted them from being present offline. While certain routes were altered by gender, there was a risk for both sexes that excessive immersion might supplant meaningful interaction. This also align with studies by Ogibi (Citation2015) and Talaue et al. (Citation2018). Gender differences are complicated, according to Serwaa (Citation2021), and no one gender is clearly more adversely impacted than the other.

Additionally significant were peer and parental impacts, which matched trends seen throughout Africa (Gitonga, Citation2020; Mbamba et al., Citation2021). Consistent with findings by Boateng et al. (Citation2021), parents’ mediation strategies had an impact on outcomes, with restrictive controlling methods being connected to worse communication skills than constructive direction. According to study on the effects of mobile technology across the continent, cellphones play a crucial role as the doorway permitting permanent access (Joubert & Suleman, Citation2022).

The uses and gratifications theory corresponds with gender disparities in motivational factors. Perloff (Citation2014) underscores this, noting that the data reveal a tendency among young women to frequently cite concerns over amplified beauty norms on social media platforms, which provoke anxiety over appearance and diminish self-assurance during in-person interactions. Young males more frequently highlighted their online sports or gaming habits, which cut them off from their offline presence. However, hazards from excessive use that replaces valuable social time were felt by both sexes. This emphasizes how crucial it is to think beyond prejudices when contemplating diverse gender pathways.

The high reliance on smartphones noted here confirms widespread African trends of mobile social media radically changing young people’s communication practices and interpersonal connections (Boateng et al., Citation2021). However, indications that some teenagers were self-reporting their usage offer optimism for improving youths’ digital literacy to make the most of technology while minimizing hazards. The trend toward "conscientious connectivity" is consistent with research trends that support deliberate, independent usage of social technologies (Rae & Lonborg, Citation2015).

Conclusion

Social media’s emergence has significantly changed how young people connect and communicate in the twenty-first century. In Community 8, Tema, this study examined the complicated effects of technology-mediated communication versus face-to-face interaction on the growth of interpersonal skills in teenagers and young adults. While it is well-known that social media platforms can help young people find their identities, develop their skills, and network, unchecked and excessive use can undermine fundamental interpersonal skills, concentration, and mental health at this crucial life stage due to the displacement of human-to-human relating. Before high levels of digital involvement become entrenched, there is a limited window for action. It will continue to be crucial to encourage youth to use technology responsibly for creativity, knowledge, and social connections before detrimental overdependence and skill atrophy take hold.

Through specialized digital literacy instruction, constructive mediation of teenage technology use, alternative social engagement programs, and training in sustaining focus, empathy, and presence, schools, parents, healthcare providers, governments, and youth themselves all have responsibilities to play. Collaboration will be necessary to take use of social media’s advantages while avoiding its drawbacks. The opportunity for substantial change is still present. With imaginative yet watchful advice based on young people’s actual experiences, this generation can learn the wisdom to wisely combine the virtual and physical worlds, increasing their relationships and personal growth. The future has not yet been written.

Implications of the study

The study’s ramifications include the following. First of all, it is evident that young people prefer social media contact to in-person encounters due to its convenience and accessibility. Thus, it is clear that young people use digital technology on a daily basis and frequently engage in online conversations using smartphones. Additionally, there is a deterioration in in-person communication skills as a result of youths’ inability to interpret non-verbal signs, pay attention to others, and carry on a discussion in-person. This demonstrates the need for direction and interventions to help young people balance offline contacts with online connection so they can develop essential communication skills. In addition, youth need to be empowered by digital literacy initiatives to utilize technology purposefully and responsibly.

Additionally, there are disparities between genders in social media usage and its impacts, with females being more drawn to visual platforms that have a major impact on their physical outlooks and anxiety while males were more drawn to games and sports. This suggests that interventions should be customized to reflect the prevailing social norms. Again, programs that support young people’s agency development are crucial, and they include guided self-monitoring of usage behaviors and impacts, reflective discussion groups, and access to extracurricular activities that foster social skills development away from screens. Additionally, in order to enact meaningful laws on social media design aspects and usage patterns that protect young health, it is imperative that partnerships between lawmakers, policymakers, and technology corporations be established. Finally, parental mediation strategies are crucial because they can encourage young people to use social media in a way that is both balanced and responsible.

Limitations

The study’s limitations stem from its exclusive focus on Community 8 youths and the role social media plays in improving youth interactions. A more comprehensive examination of the phenomena among all Tema youth will yield more insightful findings. Further research is advised to examine the occurrence among all young people in Tema and Accra, as well as potentially extending to other regions of Ghana, when funds and other resources become available.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Priscilla Kwekie Tetteh

Priscilla Kwekie Tetteh is a practicing communication specialist who has gained experience in the field. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Agricultural Science and is very interested in the use of communication tools such as social media in agricultural activities. She also holds a Master of Arts in Communication Studies from the African University College of Communications.

Philip Kwaku Kankam

Philip Kwaku Kankam is an information professional with several years of experience in librarianship and information studies. He holds a PhD in information studies from the University of KwaZulu Natal as well as BA and MA degrees in information studies from the University of Ghana. He is currently a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Information Studies, University of Ghana.

References

- Acheampong, R. (2021). Social media use and its perceived impact on the communication skills of university students in Ghana. Journal of Pedagogical Sociology and Psychology, 3(1), 1–17.

- Achebe, N. C. (2021). Social media communication styles through a cultural lens: Comparing youth Facebook use in collectivist Igbo versus individualist Yoruba ethnic groups. Africa Media Review, 29(1), 73–92.

- Adu-Gyamfi, S., & Brenya, P. (2020). Social media, academic performance and social life of students in selected senior high schools in Ashanti region of Ghana. Journal of Media and Communication Studies, 12(5), 42–57.

- Aidoo, E. (2021). Perceptions of the impact of social media on communication skills among university students in Ghana. Journal of Media and Communication, 4(2), 48–56.

- Aidoo, F., & Boateng, R. (2022). We want someone to listen and advise, not control. A qualitative study exploring adolescents’ perspectives on parental mediation of social media to build communication skills in Ghana. Computers & Education, 167, 104200.

- Al-Menayes, J. J. (2015). Motivations for using social media: An exploratory factor analysis. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 7(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v7n1p43

- Amoah, P. (2021a). Effects of WhatsApp usage patterns on the conversational competence skills of senior high school students in Ghana. Education and Information Technologies, 26(2), 2047–2062.

- Amoah, P. (2021b). WhatsApp groups and peer pressures: Implications for social cohesion among senior high school students in Ghana. South African Journal of Education, 41(4), 1–9.

- Ampah-Mensah, A. (2021). University students’ use of social media and perceived gains in social skills. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 11(3), 76–86.

- Anderson, M., & Jiang, J. (2018). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center, 31(2018), 1673–1689.

- Ankrah, A., & Oduro, G. (2021). Parent and youth social media perceptions: A qualitative parental mediation study from Ghana. Journal of Children and Media, 15(4), 524–541.

- Asare, O. (2022). The “social media obsessed” peer culture and its perceived influence on face-to-face interactions among high school students in Ghana. Journal of Adolescent Research, 37(5), 621–640.

- Baidoo, P. K., & Baiden, B. K. (2020). Students’ paradox: Assessing the impact of WhatsApp on the communication skills of students – A case study of four selected tertiary institutions in Ghana. Journal of Communications, 15(1), 22–33.

- Balakrishnan, V., & Gan, C. L. (2016). Students’ learning styles and their effects on the use of social media technology for learning. Telematics and Informatics, 33(3), 808–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.12.004

- Bandura, A. (1977a). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1977b). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

- Baruah, C., Saikia, H., Gupta, K., & Ohri, P. (2022). Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety and stress among nursing students. Indian Journal of Community Health, 34(2), 259–264. https://doi.org/10.47203/IJCH.2022.v34i02.021

- Biney, I. K. (2022). Exploring the perceived impacts of social media addiction on face-to-face communication skills among Ghanaian teenagers - A qualitative study. Adolescent Research Review, 7(1), 67–79.

- Boateng, R., Neil, L., Tennyson, R., & Adjei, O. (2021). Parent-child social media co-use and perceived effects on communication competence: An exploratory study of urban Ghanaian adolescents and parents. Journal of Black Studies, 52(3), 243–263.

- Brink, S. (2021). Associations between adolescent social media addiction and communication competence in Cape Town, South Africa. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19(5), 1635–1650.

- Chinelo, I. E., Chambers, C., & Okoye, F. (2022). Problematic social media use and interpersonal communication competence among adolescents in Lagos metropolis. Nigeria. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 42(4), 245–256.

- Choi, T. R., & Sung, Y. (2018). Instagram versus Snapchat: Self-expression and privacy concern on social media. Telematics and Informatics, 35(8), 2289–2298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.09.009

- Coleman, E. P. (2021). Individualism-collectivism and social media communication: A comparative study of Ghanaian and South African university students. Journal of Global South Studies, 38(1), 168–195.

- Creswell, J. W. (2022). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications.

- Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Management Science, 32(5), 554–571. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.32.5.554

- DataReportal. (2022). Digital 2022: Global overview report. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report

- Décieux, J. P., Heinen, A., & Willems, H. (2019). Social media and its role in friendship-driven interactions among young people: A mixed methods study. YOUNG, 27(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308818755516

- Dhir, A., Yossatorn, Y., Kaur, P., & Chen, S. (2018). Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing—A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. International Journal of Information Management, 40, 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.01.012

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). 2021 Population and Housing Census – Tema Metropolitan. https://statsghana.gov.gh/gsscommunity/adm_program/Modules/Parish/Reports/2020%20PHC%20-%20District%20Analytical%20Report%20-%20Tema%20Metropolitan.pdf

- Ghosh, T., Sreejesh, S., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2021). Examining the deferred effects of gaming platform and game speed of advergames on memory, attitude, and purchase intention. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 55, 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2021.01.002

- Githinji, E. W., & Mueke, M. M. (2020). Impact of social media on communication skills of university students in selected Kenyan universities. The African Journal of Information Systems, 13(1), 88–115.

- Gitonga, P. W. (2020). The influence of peer social media engagement on youth communication competence in Nairobi. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(10), 1398–1416.

- Hampton, K. N., Shin, I., & Lu, W. (2017). Social media and political discussion: when online presence silences offline conversation. Information, Communication & Society, 20(7), 1090–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1218526

- Hoffner, C., & Buchanan, M. (2005). Young adults’ wishful identification with television characters: the role of perceived similarity and character attributes. Media Psychology, 7(4), 325–351. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0704_2

- Holland, G., & Holland, S. (2018). Interpersonal skills: The foundation for relationships and learning. Family Relations Journal, 5(2), 22–34.

- Joubert, J., & Suleman, F. (2022). The social impact of social media on South African university students. Education and Information Technologies, 27(2), 1487–1508.

- Juma, L. S., & Kamere, E. W. (2022). Social media platform preferences by gender: Comparing Kenyan and Tanzanian undergraduate students. Sage Open, 12(3), 21582440221105327.

- Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

- Kankam, P. K. (2020). Approaches in information research. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 26(1), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2019.1632216

- Kankam, P. K. (2023). Information literacy development and competencies of high school students in Accra. Information Discovery and Delivery, 51(4), 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1108/IDD-10-2021-0114

- Kankam, P. K., & Baffour, F. D. (2023). Information behaviour of prison inmates in Ghana. Information Development, 026666692311786. https://doi.org/10.1177/02666669231178661

- Kircaburun, K., Alhabash, S., Tosuntaş, Ş. B., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: A simultaneous examination of the Big Five of personality traits, social media platforms, and social media use motives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9940-6

- Le Roux, L. J., & Chetty, Y. B. (2022). The longitudinal impact of increased social media usage on adolescent interpersonal skills in Cape Town. South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 52(1), 99–109.

- Le, L. H., & Hancer, M. (2021). Using social learning theory in examining YouTube viewers’ desire to imitate travel vloggers. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 12(3), 512–532. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-08-2020-0200

- Lewis, R., Roden, L. C., Scheuermaier, K., Gomez-Olive, F. X., Rae, D. E., Iacovides, S., Bentley, A., Davy, J. P., Christie, C. J., Zschernack, S., Roche, J., & Lipinska, G. (2021). The impact of sleep, physical activity and sedentary behaviour on symptoms of depression and anxiety before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample of South African participants. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 24059. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02021-8

- Li, D. D., Liau, A. K., & Khoo, A. (2013). Player–avatar identification in video gaming: concept and measurement. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.09.002

- Lukonga, I. M. (2022). Social media addiction and academic performance of undergraduate students of Saint Augustine University of Tanzania (Doctoral dissertation, The Open University of Tanzania).

- Mbamba, K. U., Mfaume, H., & Mtuy, T. (2021). Parental mediation and social media effects on psycho-social development of children in Congo. Journal of Educational Media & Technology, 7(1), 1–15.

- Mensah, A. D. (2021). Social networking and interpersonal communication: assessing effect on communication competence among senior high school students in selected schools in Greater Accra Region (Doctoral dissertation, University of Ghana).

- Mingle, J., & Adams, M. (2015). Social media network participation and academic performance in senior high schools in Ghana. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1(1), 3.

- National Communication Authority. (2020). A survey on child online safety in Ghana.

- Nurudeen, M., Abdul-Samad, S., Owusu-Oware, E., Koi-Akrofi, G. Y., & Tanye, H. A. (2023). Measuring the effect of social media on student academic performance using a social media influence factor model. Education and Information Technologies, 28(1), 1165–1188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11196-0

- Ogara, S. O., Koh, C. E., & Prybutok, V. R. (2014). Investigating factors affecting social presence and user satisfaction with mobile instant messaging. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 453–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.064

- Ogibi, J. D. (2015). Social media as a source of self-identity formation: Challenges and opportunities for youth ministry.

- Okere, C. O., Anyanwu, J. I., & Akande, T. F. (2021). Use of social media and academic performance of undergraduates in selected Nigerian universities. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 11(3), 76–86.

- Oládele, R. A., Oladokun, S. A., & Moronfolu, J. A. (2022). Individualism, collectivism, and social media: A one-year longitudinal study of Nigerian youth communication skills. Journal of Adolescent Research, 37(1), 149–172.

- Omollo, R. O. (2022). Cultural orientations toward time and youth social media communication patterns: A comparative study of Kenya and Tanzania. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 51(3), 240–260.

- Orben, A., & Przybylski, A. K. (2019). The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(2), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0506-1

- Osei-Frimpong, K. (2019). Examining social media addiction among youth in Ghana. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 22(4), 265–282.

- Owusu, C., & Kankam, P. K. (2020). Information seeking behaviour of beggars in Accra. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 69(4/5), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-07-2019-0080

- Owusu, S. (2022). Social media addiction and self-reported face-to-face communication skills among Ghanaian university students: A mixed methods study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(1), 191–213.

- Owusu-Acheaw, M., & Larson, A. G. (2015). Use of social media and its impact on academic performance of tertiary institution students: A study of students of Koforidua Polytechnic. Ghana. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(6), 94–101.

- Owusu-Appiah, R. K. (2022). A qualitative gender analysis of social media addiction and face-to-face communication skills among Ghanaian youth. Adolescent Research Review, 7(4), 515–531.

- Pellegrino, A., Stasi, A., & Bhatiasevi, V. (2022). Research trends in social media addiction and problematic social media use: A bibliometric analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 1017506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1017506

- Perloff, R. M. (2014). Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles, 71(11-12), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6

- Quaicoe, E., Pata, K., & Jeladze, E. (2020). Examining the relationship between problematic social media use and interpersonal communication competence. Contemporary Educational Technology, 12(3), ep295.

- Rae, J. R., & Lonborg, S. D. (2015). Trends in counseling center utilization by gender, age and ethnicity. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 29(4), 296–311.

- Serwaa, B. (2021). Differences in the perceived influence of social media on communication competence between male and female high school students in Ghana. Journal of Adolescent Research, 36(4), 481–509.

- Shaw, C. (2022). Is your research project ethical? Here’s how to find out. The Qualitative Report, 27(12), 2633–2641.

- Shihepo, E. (2023). Social media and youth identity in the Namibian context. Journal of African Media Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1386/jams_00056_1

- Shim, J. P., Shropshire, J., Park, S., Harris, H., & Campbell, N. (2007). Podcasting for e‐learning, communication, and delivery. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 107(4), 587–600. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570710740715

- Sibanda, G., Tinashe, M., & Vaida, M. (2019). #Social media: Creating, destroying or reconstructing social bonds. Contemporary Social Science, 15(2), 244–256.

- Sibanda, L. (2020). The influence of social media on interpersonal communication competence of adolescent youth in Gauteng. South Africa. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 32(3), 133–140.

- Steinberg, L. (2020). Adolescence. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Sunday, A. M., Oludele, J. S., & Omiola, M. A. (2022). Social media addiction and mental health of undergraduates in selected universities in Ogun State. Nigeria. FUTA Journal of Management and Technology, 3(1), 129–142.

- Sylla, A. (2022). High context culture: Implications for social media communication competence in youth. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 17(2), 201–216.

- Talaue, G. M., AlSaad, A., AlRushaidan, N., AlHugail, A., & AlFahhad, S. (2018). The impact of social media on academic performance of selected college students. International Journal of Advanced Information Technology, 8(4/5), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.5121/ijait.2018.8503

- Tandon, A., Dhir, A., Talwar, S., Kaur, P., & Mäntymäki, M. (2021). Dark consequences of social media-induced fear of missing out (FoMO): Social media stalking, comparisons, and fatigue. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 171, 120931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120931

- Tseng, C.-H., & Wei, L.-F. (2020). The efficiency of mobile media richness across different stages of online consumer behavior. International Journal of Information Management, 50, 353–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.08.010

- Twenge, J. M., Spitzberg, B. H., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Less in-person social interaction with peers among US adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(6), 1892–1913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519836170

- Umar, Y., & Mohammed, Z. (2022). Peer social media groups for communication skills enhancement among Nigerian youth. Telematics and Informatics, 61, 101724.

- Umubyeyi, G. (2021). Social media usage within cultural orientation of uncertainty avoidance by Rwandan youth. Journal of African Media Studies, 13(3), 365–379.

- Wartella, E., Pila, S., Lauricella, A. R., & Piper, A. M. (2021). The power of parent attitudes: Examination of parent attitudes toward traditional and emerging technology. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(4), 540–551. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.279

- Williams, M., & Moser, T. (2019). The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. International Management Review, 15(1), 45–55.

- Yeboah-Obeng, W., & Kyeremeh, T. A. (2022). Social media use and academic performance: Does WhatsApp make a difference? Education and Information Technologies, 27(3), 3779–3797.