Abstract

This study explored the perspectives of community members on the management and ownership of freshwater resources. A mixed-method study was conducted targeting household heads, traditional leaders, and assembly members in communities surrounding the lake. Household heads (309), and 14 focus group discussions were used in the study. There were 46.9% and 29.4% of the respondents who perceived that the lake was owned by the government and the community (chiefs and the indigene) respectively. While 48.2% and 28.8% perceived the traditional authority and the government separately as the managers of the lake. The study found out that, the community perceives the Lake as their resource and hence their traditional leaders should have control over it with support from the government and other NGOs. This implies that activities carried out concerning the Lake should have the approval of people to avoid conflict and power struggles.

1. Introduction

Freshwater resources are essential for the survival of humans and other organisms on the planet. However, the increasing demand for freshwater resources due to population growth, urbanization, and industrialization has led to significant freshwater scarcity in many parts of the world (Musie & Gonfa, Citation2023) to the extent that water is now a top global risk (World Economic Forum, Citation2023). Poor management of freshwater resources has also contributed to the deterioration of water quality, degradation of ecosystems, and loss of biodiversity (Botha et al., Citation2022; UN Water, Citation2018).

Globally, the management of freshwater resources has been a subject of debate, and various frameworks have been developed to ensure the sustainable use and management of these resources. The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognized the importance of freshwater management and included a dedicated goal, Goal 6, which aims to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all by 2030 (United Nations Development Programme, Citation2019). Additionally, the United Nations General Assembly designated 2018–2028 as the International Decade for Action on Water for Sustainable Development, to promote the sustainable management of freshwater resources (UN Water, Citation2018).

Freshwater resources are a critical component of human survival and development, and their management and ownership have become increasingly important in recent years due to population growth, urbanization, and climate change (UN Water, Citation2019). The management and ownership of freshwater resources are complex issues that require consideration of various perspectives and stakeholders, including governments, communities, and private sector actors (Krause et al., Citation2017). According to the United Nations, freshwater resources are under increasing pressure, and more than 2 billion people worldwide lack access to safe drinking water (United Nations, Citation2021) bringing about water insecurity (Musie & Gonfa, Citation2023). This has led to a growing concern for the management of freshwater resources as the global population continues to grow. Additionally, climate change has exacerbated the situation, leading to water scarcity in many regions of the world (Masson-Delmotte et al., Citation2022).

In Africa, freshwater resources are crucial for economic development, food security, and poverty reduction (Ahmed et al., Citation2022). However, the management and ownership of freshwater resources are often characterized by conflicts and tensions due to a lack of clarity regarding property rights and governance arrangements (Bosch & Gupta, Citation2022; Grafton et al., Citation2019). This situation is compounded by weak institutions and inadequate capacity at the local level (Hilson, Citation2019). Access to freshwater resources remains a challenge, with many people lacking access to safe drinking water (World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund, Citation2021). The situation is further complicated by issues such as poverty, political instability, and weak governance, which limit the development and implementation of sustainable policies and practices for the management of freshwater resources (World Bank, Citation2021).

In Ghana, the management of freshwater resources is also a significant challenge. Although Ghana has significant freshwater resources, including rivers, lakes, and underground water, these resources are under increasing pressure due to population growth, urbanization, and climate change (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Citation2020). The situation is further complicated by issues such as pollution, illegal mining, and inadequate infrastructure for water supply and sanitation (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021).

Article 106 of the Constitution grants the Parliament of Ghana the power to make laws, including laws related to water resources. The management of water resources in Ghana through the Water Resources Commission (WRC) and its Act, Act 522 derived authority from Article 269 of the Constitution (Ministry of Sanitation and Water Resources [MSWR], nd). The creation of WRC marked the formalization of a dedicated agency for water resources management. WRC is the primary regulatory body responsible for the planning, development, management, pollution control, Licensing and Regulation of Dams and Reservoirs, Conflict resolution, and protection of water resources in Ghana (Awuku, Citation2016; Owusu & Asumadu-Sarkodie, Citation2016). The WRC issues water use permits, develops water resource management plans, monitors water quality, promotes public awareness about water conservation, and issues enforcement notices (WRC, nd). However, the work of WRC has not been efficient because of the lack of offices in all the administrative districts of the country coupled with the attitude of indigenous (Asomani-Boateng, Citation2019). Many districts, even though, host lots of water resources reservoirs have access and quality problems.

The Bosomtwe District in Ghana, for instance, is home to several freshwater resources including River Oda, River Butu, River Siso, River Supan and River Adanbanwe, and Lake Bosomtwe, which serves as a critical source of livelihood for the local communities (Amofah & Kwarteng, Citation2014; Asare et al., Citation2021; Asare-Kumi et al., Citation2017). The management and ownership of freshwater resources in the Bosomtwe District have been subject to different perspectives and controversies (Amu-Mensah et al., Citation2019). While some argue that the government should have full control over freshwater resources, others advocate for community-based management models that prioritize local participation and decision-making (Bury et al., Citation2013).

Several studies have examined the issue of freshwater in Ghana from different perspectives. For example, Agyeman (Citation2017) argues that managing freshwater resources in Ghana is characterized by conflicts and power struggles between stakeholders including government agencies, local communities, and private interests. Similarly, Ansah et al. (Citation2020) point out that Ghana’s lack of clear ownership and management frameworks for freshwater resources has contributed to their overuse and degradation. Boakye et al. (Citation2021) noted that the local communities in the district have traditionally relied on Lake Bosomtwe for their livelihoods and cultural practices. However, the construction of tourist facilities in recent times has brought forth a crucial question regarding the rightful management and control of the lake. The fundamental question is who holds the authority to manage and control the lake? Is it the traditional authorities, local residents, opinion leaders, or the government? It is against this backdrop that this study seeks to explore the perspectives of the residents in the Bosomtwe District on the management and ownership of freshwater resources. The perspectives of the residents in the Bosomtwe District on the management and ownership of lake Bosomtwe as a freshwater resource is important to understand as this is critical in tackling conflict and power struggles over resource use and control. Their perspectives can inform policies and decision-making processes related to the management and ownership of freshwater resources in the district. In addition, their perspectives can help to identify areas of concern and opportunities for improvement in the management of these resources.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study setting and population

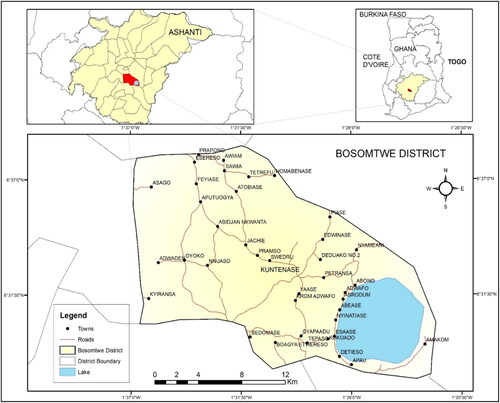

The study took place in Bosomtwe District, located at the centre of Ashanti Region in Ghana (see ). The district encompasses an area of 422.5 square kilometers and is positioned between 6° 24 South and 6° 43 North latitudes, and 1° 15 East and 1° 46 West longitudes. The district features a dendritic drainage pattern and an equatorial climate with two rainy seasons. The primary economic activities revolve around crop production and animal breeding, with agriculture serving as a major income source. The district had a population of 93,910 according to the 2010 census, but the 2021 national census reported a population increase to 165,180. In the Bosomtwe District is Lake Bosomtwe a scenic natural freshwater meteorite crater lake. This beautiful lake which serves as national tourist site is located in the Ashanti Region of Ghana (Boamah & Koeberl, Citation2007). The Lake Bosomtwe area is an important geological site because it houses the largest, young (1.07 Ma) and well-preserved complex meteorite impact crater currently known on earth.

Figure 1. is inserted to provide a visual representation of the study setting and its geographic location.

Source: Amoah-Nuamah (Citation2023).

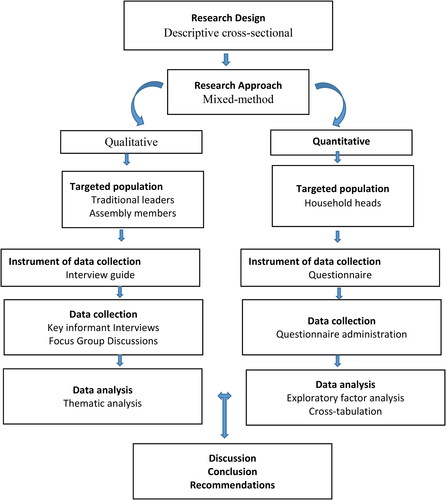

2.2. Research design

The study aimed to comprehensively understand the perspectives of residents in the Bosomtwe District regarding the management and ownership of freshwater resources. To achieve this, a descriptive cross-sectional mixed-method study was conducted. By employing both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods, a thorough and well-rounded examination of the topic was ensured. Quantitative data was collected through questionnaires, while qualitative data was obtained via interviews using an interview guide.

The rationale for utilizing a mixed-method study was its ability to explore the research topic comprehensively, offering a holistic view. Incorporating both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods allow for insights into both objective and subjective aspects of the research question. Questionnaires facilitate gathering standardized data from a larger sample size, while interviews provide more detailed and nuanced data from a smaller sample size. This approach guarantees a comprehensive understanding of residents’ perspectives in the Bosomtwe District regarding the management and ownership of freshwater resources.

2.3. Study population and sampling process

The targeted population of this study consisted of household heads, traditional leaders, and assembly members residing in the communities surrounding Lake Bosomtwe. The sampling process involved obtaining population data for each selected community from the district’s medium-term development plan (See ). The total number of households in each community was calculated by dividing the population by the average household size in the region. The sample size for each community was determined using EPI Info 7 software, a reliable tool widely used in epidemiological research for sample size estimation to ensure precise characterization of the target population.

Table 1. Unit of Enquiry sample frame and sample size.

To select households for the household survey, a simple random sampling technique was employed. This method was chosen as it provided equal opportunities for all households within the affected communities. Moreover, detailed information about the sampling frame was available, and the communities were not excessively large, making the approach suitable for the study’s objectives.

Questionnaires were employed to gather information regarding the perspectives of residents in the Bosomtwe District on the management and ownership of freshwater resources. Prior to data collection, the questionnaire underwent a pre-test to assess its face and content validity, with consultation from water resource management experts. The questionnaire primarily consisted of closed-ended questions, focusing on demographic characteristics such as gender, age, marital status, religion, level of education, and ethnicity. Additionally, respondents rated statements related to ownership and management, using a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Key informant interviews were conducted with traditional leaders and assembly members (See ), chosen specifically for their extensive knowledge of the subject matter. Focus group discussions were also carried out with residents from seven selected communities near Lake Bosomtwe, as these communities directly benefited from its ecological services (See ). The number of participants in each group followed the optimal range suggested by Manoranjitham et al. (Citation2007), with 8 to 10 participants. Participants were randomly selected from both genders and had a minimum residency of five years in the communities. An interview guide was developed for the focus group discussions and key informant interviews. Written and oral consents were obtained from all participants, and measures were taken to ensure confidentiality.

Table 2. Sample units and the number of key informants interviewed.

The discussions primarily took place in the local dialect (Twi), except participants who were comfortable expressing themselves in English, for whom the discussions were conducted in English. The interviews and discussions had an average duration of approximately 90 minutes and they concluded when saturation, the point of data redundancy, was reached. Before the main data collection, a pilot test was conducted to refine the research instruments. The role of the moderator was to facilitate the discussions rather than leading them. All interviews and discussions were audio-recorded with the participant’s consent, and field notes were taken to supplement the recordings. To ensure rigor and trustworthiness, various strategies were employed, such as pre-testing the instruments of data collection, engaging experts in water resource management, and conducting focus group discussions that included both men and women.

2.4. Ethical consideration

Engaging in research involving human subjects requires meticulous attention to ethical considerations, as social scientists often encounter ethical dilemmas (Israel & Hay, Citation2006). Accordingly, prior to commencing field data collection, we thoroughly examined and addressed several ethical issues. An introductory letter for fieldwork was obtained from the Department of Geography Education at the University of Education, Winneba, Ghana. Additionally, we sought and obtained ethical clearance from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Education, Winneba, with reference number UEWEC/19. Recognizing that our study is human-centered research, we prioritized the issue of human dignity. We acknowledged that our participants, like all individuals possess interests and integrity, which we did not disregard as researchers. We made concerted efforts to respect and safeguard the integrity and privacy of our participants, as well as protect them from harm and undue strain. Moreover, we considered participants’ autonomy and their rights to self-determination. Adequate information regarding the data collection processes and the intended use of the results for academic purposes was provided to all participants. The potential consequences of participation in the study were also disclosed. Regarding consent, oral consent was obtained from participants who were unable to read or write while those who could read and write signed the informed consent form. The researchers typically used an audio recording device (Sony ICD-PX470 Digital voice recorder) to document the verbal consent process. This allows the researchers to capture the participant’s verbal agreement or acknowledgment of their willingness to participate in the study. Consent was given freely and explicitly. Finally, confidentiality was assured by de-identifying participants’ personal data to ensure anonymity.

2.5. Data analysis

This study utilized both qualitative and quantitative methods to analyze the collected data. By employing a combination of these methods, a more comprehensive understanding of the data was achieved, enhancing the study’s conclusions.

Quantitative data analysis involved utilizing the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Software Version 26. Exploratory factor analysis and descriptive statistics were employed to provide a detailed description of the data. Descriptive statistics allowed for the presentation of data in terms of frequencies and proportionate counts, facilitating an overview of respondents’ demographics and perceptions. Cross tabulation statistical method was also utilized to explore the relationship between ownership and management of the lake.

For qualitative data, a thorough review of field and interview notes was conducted to gain insight into the collected information. All audio-recorded interviews were transcribed into English and reviewed. Thematic analysis was applied using the QDA Miner software to identify key themes and patterns within the qualitative data. Thematic analysis was chosen as it facilitated the identification of patterns and themes, enabling a deeper understanding of respondents’ perceptions and experiences.

The quantitative findings were presented in tables and direct quotations were used to present qualitative results. The direct quotations allowed readers to engage with the respondents’ exact words, lending a human touch to the findings and enhancing relatability. is the flowchart summarizing the methodological workflow of the study.

3. Result

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

shows the breakdown of respondents socio-demographic characteristics. The results indicate that 55.3% of the respondents were males, while 44.7% were females. It is evident from that age group 20 to 29 constituted the majority with 32.0% followed by age group 30 to 39 with 21.1% while those aged 60 and over were the minority with only 2.9% representation. In terms of ethnicity, most (72%) of the respondents were Akans. Christians, particularly Pentecostals/Charismatics, were the most represented religious group, comprising 64.1% of the sample (See ).

Table 3. Showing the socio-demographic data of respondents.

Regarding the years of stay, 35.9% of respondents had spent between 11 to 20 years in the area, while 16.2% had spent between 5 to 10 years. The findings suggest that the sample was skewed towards younger, working-age males, and the dominant ethnic group of the study area was the Akans. The data presented in provides a detailed overview of the socio-demographic background of the respondents and can be used to better understand the characteristics of the study population.

3.2. Residents views on management of Lake Bosomtwe

This analysis aimed to evaluate the resident’s view of management and ownership of Lake Bosomtwe. A survey was conducted among people living in towns surrounding the lake, and 13 variables were presented to the respondents to indicate the extent to which those factors influenced their perception concerning the management and ownership of the freshwater ecosystem (see ). An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on the variables to empirically assess the factors responsible for influencing the locals’ perception of management and ownership of freshwater resources.

Table 4. Variables Influencing Indigenous Perception on Community- based Freshwater management.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA), which indicates the appropriateness of the data for the factor analysis, was 0.844, indicating that the data was appropriate for factor analysis. The commonalities of the scale, which indicates the amount of variance in each dimension among the variables, was also assessed. The results showed that all variables had commonalities above 0.500 with only one item having a commonality slightly less than 0.500. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was statistically significant at x2 (n = 78) = 1330.280 (p < 0.001), supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix. It can be observed from that the PCA/VR solution performed yielded three (3) factors, which accounted for a cumulative variance of 56.117 per cent. These three (3) dimensions had eigenvalues greater than one (1).

Table 5. Factor Loadings Explaining the local’s Perception about Management and ownership of Lake Bosomtwe.

The three significant factors that influence the local perception of freshwater management are; community ownership and control, policy formulation and implementation, and community initiative in sustainable freshwater management. Based on the EFA, it was found that the respondents valued community ownership of the lake. The findings showed that the majority of the survey participants referred to water as a "common resource" and argued that it should be owned and controlled by the community (See ).

The qualitative data collected from key informant interviews and focus group discussions shed light on the perspectives regarding the management and ownership of Lake Bosomtwe. These quotations highlight different viewpoints expressed by participants:

The lake belongs to us. It is something our forefathers depended on for farming and fishing. It is our major resource. The government and stakeholders can help us to manage the lake (Male, 2022).

Even though the lake is solely owned by the chiefs and community members, the government and other stakeholders can help us manage it well. (Assembly Member, 2022).

The lake belongs to the Ashanti Asantehene (King of the Asante). The king is the ultimate owner of Lake Bosomtwe. The king of Asante and the local people are the true owners of the lake and therefore are mandated to manage it with the help of the government (Traditional leader, 2022).

The second factor, policy formulation, and implementation suggests that communities should be actively involved in the Lake’s management system, be consulted in decisions concerning the Lake’s management, and be involved in income-generating activities of Lake Bosomtwe. Below are quotations from the key informants’ interviews and focus group discussions explaining the management and ownership of the Lake Bosomtwe?

Ooh yes, any policy or initiative that is aimed at managing the lake without involving the chiefs, the opinion leaders, and the community members actively will not end well. How can you formulate a policy without involving the key stakeholder (the chiefs and community members? (Assembly Member, 2022).

We have lived with the lake for so long and everything about is known to us. The local people must be highly consulted and involved in the formulation of decision-making and policies related to the lake. The government can initiate the process but we must be an integral part of the formulation process. (Male, 2022)

Yes, the lake sustains the livelihood of some of us, so any policy and initiative about the lake should involve us (Female discussant, 2022).

These quotes provide a foundation for understanding the importance of community involvement and consultation in policy formulation and decision-making processes related to Lake Bosomtwe. Participants emphasize the significance of including the key stakeholders, such as chiefs, opinion leaders, and community members, in the policy-making process. They stress the need for their active participation and recognition of their expertise and lived experience with the lake. These perspectives contribute to the qualitative data, highlighting the call for meaningful engagement and collaboration between the government and local communities in the formulation and implementation of policies concerning Lake Bosomtwe.

The qualitative data collected in relation to the third factor, community initiative, provides insights into the perspectives regarding community-based approaches to managing Lake Bosomtwe. The following quotations exemplify participants’ viewpoints:

The best approach to manage the Lake is to establish a community base Lake management team that will comprise of the representative of the traditional authorities, assembly and most importantly the local people who are direct beneficially of the lake. (Assembly Member, 2022)

When the communities and local authorities come together with the help of other stakeholders, they can form a good committee to manage it at the local level (Male, 2022)

Yes, we benefit from the lake so we can manage well. We may need little or no help from any external person to manage the lake. We have even planted trees along the bank of the lake to protect the lake (Female discussant, 2022).

3.3. The relationship between the management and ownership of the Lake

The cross-tabulation table () provides insights into the relationship between the ownership and management of the lake based on the perceptions of 309 respondents. The highlights the count and percentage of respondents who attributed ownership or management of the lake to a particular owner or manager.

Table 6. Cross Tabulation showing relation between who owns the lake and who manages the lake.

Regarding the ownership of the lake, shows that out of the 309 respondent’s majority (46.9%) perceive that the government is the owner of the lake. Among these respondents however, 22.7% perceive that the lake is managed by the government, 19.4% believe it is managed by the traditional authority and only a percentage (1.0%) perceive that the community manages the lake. This suggests a significant sense of governmental presence and regulatory authority over the lake, reflecting formal interventions and oversight in its management.

Moreover, 91 (29.4%) respondents perceive the community (chiefs and the indigene) as the owners of the lake out of whom 20.1%, 3.2%, and 5.2% perceived the traditional authority, government, and the community as the managers of the lake respectively. This could suggest a sense of local stewardship over the resources and responsibility of the residents.

Interestingly, 56 (18.1%) of the respondents do not know who owned the lake, out of whom 8.1% also did not know who manages the lake. There were 7.1%, 2.6%, and less than a percentage (0.3%) respondents with the perception that the lake was managed by the traditional authority, government and the community correspondingly. Perhaps this could mean a potential lack of clarity or transparency in the governance structure surrounding the lake.

Generally, respondents highlight the involvement of other stakeholders in the lake ownership. While a small percentage (3.2%) of respondents perceived that the lake was owned by Water and Sanitation Management Team (WSMT) or an NGO (2.3%) (see ).

Conversely, in terms of the management of the lake, shows that the majority (48.2%) of respondents perceived that the lake was mostly managed by the traditional authorities. But within this group, while 20.1% of them perceive the community as the owners of the lake, 19.4% perceive that the ownership of the lake is in the hands of the government and yet 7.1% did not know who owned the lake at all.

Also, among the 28.8% of the respondents who perceive the government as the manager of the lake 22.7% perceive the government as the owner of the lake, only 3.2% perceive the community as the owner of the lake but 2.6% did not know who owned the lake.

A significant proportion (12.9%) of the respondents do not know who manages the lake. 7.1% of them also did not know who own the lake while 2.3% of the same respondents perceived the government as the owner of the lake and only 1.0% perceived the community as the owner.

Finally, the community was perceived to manage the lake by 6.8% of the respondents, out of whom 5.2% perceive the community and 1.0% perceive the government as the owners of the lake. While 3.2% of the respondents perceived that the lake was managed by WSMT staff only 1.6% of the respondents perceived that the lake was managed by an NGO.

The results generally show that the majority of the respondents perceive the traditional authorities as the managers of the lake but the ownership was largely perceived to be by the government. However, when looking at the relationship between ownership and management, we observed that the majority of respondents who perceived the government as the owner of the lake also perceived the government as the manager of the lake. Furthermore, many of the respondents who perceive the community as the owners of the lake also perceived the traditional authorities as the managers of the lake, and for the majority who do not know the owner also do not know the manager. Additionally, a small percentage of respondents who perceived the community as the owner of the lake also perceived the community as the manager of the lake.

4. Discussion

The research paper addresses the complex issue of conflicting ownership and management of freshwater resources, which has been highlighted in previous literature (Agyeman, Citation2017; Ansah et al., Citation2020). The study recognizes the crucial role played by Lake Bosomtwe as a vital resource for the livelihoods and cultural practices of local communities (Boakye et al., Citation2021). It delves into the implications of this issue and explores factors influencing the local perception of freshwater management.

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the factors that shape local perspectives on freshwater management. Community ownership and control, policy formulation and implementation, and community initiative emerge as significant factors that influence the way local communities perceive and approach freshwater management. These findings align with existing literature on community-based natural resource management, which highlights the importance of involving local communities in decision-making and management processes to achieve more effective and sustainable outcomes (Agrawal & Gibson, Citation1999; Berkes, Citation2004).

One key implication of this study is the recognition of the crucial role of community involvement in policy formulation and implementation related to lake management. The respondents emphasized the need for active participation of communities in the decision-making process and income-generating activities associated with the lake. This finding is in line with the principles of community-based natural resource management, which stress the significance of community participation in decision-making and management activities (Berkes, Citation2004; Fuentes-Castro et al., Citation2020). The inclusion of local communities in policy processes ensures that their knowledge, needs, and perspectives are taken into account, leading to more contextually appropriate and sustainable management strategies.

Another important implication highlighted by the study is the establishment of community-based knowledge-sharing platforms and the formation of community lake management associations. These findings align with previous studies that underscore the role of community-based organizations in natural resource management (Armitage et al., Citation2009; Ostrom, Citation1990). The creation of knowledge-sharing platforms allows for the exchange of information, experiences, and best practices among community members, enabling collective learning and capacity building. Similarly, the formation of community lake management associations provides a formal structure for community engagement, coordination, and decision-making regarding freshwater resources. These associations can enhance the community’s capacity to manage and sustainably utilize the lake’s resources by facilitating collaboration, resource mobilization, and collective action.

Regarding ownership and management of the lake, the majority of respondents perceive the government as the rightful owner, while the traditional authority is seen as the manager. This result, contrast that of Fielmua (Citation2020) who found that the community perceive community ownership of the water systems constructed for their communities in the upper west region. This finding emphasizes the significant role that local communities play in the management of the lake, reflecting their historical and cultural connections to the resource. A similar observation was made by Adjakloe (Citation2021) about the customary governance of Nsakyi River by the locals of Faase community of the Ga West Municipal. There is no doubt that there is a sense of responsibility when people perceive themselves as owners and or managers of any resource. That is why authors such as Gondo et al. (Citation2019) argue that customary governance of resources ought to be given attention as much as statutory governance. However, it is important to note that some respondents also perceive the government as the owner and manager of the lake at the same time, indicating the need for collaboration and shared responsibility between the community and the government. This suggests that a cooperative and inclusive approach to lake management, involving both the local residents and the government, can lead to more effective and sustainable outcomes. It highlights the importance of recognizing and respecting the diverse perspectives and interests of different stakeholders while working towards a common goal of ensuring the long-term sustainability of the lake and its benefits to local communities.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

This study provides comprehensive insights into the factors that shape local perspectives on freshwater management. The findings emphasize the importance of community ownership and control, active community involvement in policy formulation and implementation, and the establishment of community-based knowledge-sharing platforms and associations. These findings align with existing literature on community-based natural resource management and underscore the significance of involving local communities in decision-making and management processes. The study highlights the need for collaboration between the local communities and the government in effectively managing the lake’s resources while also emphasizes the importance of recognizing the diverse perspectives and interests of different stakeholders. By understanding these factors and implications, policymakers and stakeholders can develop more inclusive, participatory, and sustainable freshwater management strategies that address the needs and aspirations of local communities while ensuring the long-term health and resilience of the lake ecosystem.

Based on the study’s findings and conclusions, it is recommended that community ownership and control, policy formulation and implementation, and community initiative in sustainable freshwater management should be prioritized in the development of freshwater management strategies. The following recommendations are suggested: (1) Community involvement in decision-making and management processes should be encouraged and promoted. This can be achieved through the establishment of community-based knowledge-sharing platforms and the formation of community lake management associations. (2) Policies and regulations regarding the management of the lake should be formulated with the active participation of the community. This will help ensure that policies are relevant and responsive to the needs of the local community. (3) Collaboration between the community and the government should be promoted to enhance freshwater management efforts. The government should recognize and support community initiatives in freshwater management. (4) Traditional authorities should be recognized and integrated into freshwater management efforts, given their role as managers of the lake.

Author’s contributions

JAN: Conceptualization, supervision, data curation and original drafted. EYO: Project administration, methodology, and validation. KAM: Investigation and software analysis. MMA: Visualization and resource provision MOA: Writing review and editing and approval of final draft RG: Formal analysis and editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data used in this study is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

- Adjakloe, Y. D. (2021). Customary water resources governance in the Faase community of Ghana. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100228

- Agrawal, A., & Gibson, C. C. (1999). Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Development, 27(4), 629–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00161-2

- Agyeman, A. K. (2017). Power struggles over freshwater management in Ghana: A case study of the Volta River Basin. Water Alternatives, 10(1), 83–102.

- Ahmed, Z., Gui, D., Qi, Z., & Liu, Y. (2022). Poverty reduction through water interventions: A review of approaches in sub‐Saharan Africa and South Asia. Irrigation and Drainage, 71(3), 539–558. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.2680

- Amoah-Nuamah, J. (2023). Exploring the local perceptions of the ecological services of Lake Bosomtwe, Ghana. African Geographical Review, 42(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2023.2297710

- Amofah, G., & Kwarteng, A. (2014). Evaluation of the water quality of Lake Bosomtwe, Ghana, using multivariate statistical techniques. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 186(12), 8629–8643.

- Amu-Mensah, M., Stephen, B. K., Antwi, K. B., Frederick, K. A.-M., Analoui, F., Dickson, M., & Saraphina, A.-M. (2019). Knowledge relationships in freshwater governance. Sociology Mind, 09(03), 222–245. https://doi.org/10.4236/sm.2019.93015

- Ansah, E. O., Annor, F. O., & Fosu, M. (2020). Property rights and the overuse of natural resources in Ghana. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22(8), 7619–7642.

- Armitage, D., Marschke, M., & Plummer, R. (2009). Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Global Environmental Change, 18(1), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.07.002

- Asare, A., Thodsen, H., Antwi, M., Opuni-Frimpong, E., & Sanful, P. O. (2021). Land use and land cover changes in Lake Bosumtwi watershed, Ghana (West Africa). Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, 23, 100536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsase.2021.100536

- Asare-Kumi, D., Asare, R., Agyenim-Boateng, E., & Sarpong-Kumankoma, E. (2017). The political ecology of Lake Bosomtwe, Ghana: Examining conservation and development in a protected area. Environmental Science & Policy, 78, 95–103.

- Asomani-Boateng, R. (2019). Urban wetland planning and management in Ghana: A disappointing implementation. Wetlands, 39(2), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-018-1105-7

- Awuku, E. T. (2016). Indigenous knowledge in water resource management in the upper Tano river basin, Ghana [Mater’s dissertation, University of Cape Coast].

- Berkes, F. (2004). Rethinking community-based conservation. Conservation Biology, 18(3), 621–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00077.x

- Boakye, G., Ayisi-Amoako, E. A., Adu, S., Owusu-Boateng, G., & Boateng, S. (2021). The influence of community-based natural resource management on local livelihoods: Insights from selected communities around Lake Bosomtwe, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 657.

- Boamah, D., & Koeberl, C. (2007). The Lake Bosumtwi impact structure in Ghana: A brief environmental assessment and discussion of ecotourism potential. Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 42, 561–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.2007.tb01061.x

- Bosch, H. J., & Gupta, J. (2022). The tension between state ownership and private quasi-property rights in water. Wires Water, 10(1), e1621. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1621

- Botha, M., Oberholzer, M., & Middelberg, S. L. (2022). Water governance disclosure: The role of integrated reporting in the food, beverage and tobacco industry. Meditari Accountancy Research, 30(7), 256–279. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-09-2020-1006

- Bury, J., Mark, S., & Rowley, J. (2013). Community-based management and inter-organisational partnerships in Lake Bosomtwe, Ghana: Reflecting on the roles of the state and community in neoliberal times. International Journal of the Commons, 7(2), 254–277.

- Fielmua, N. (2020). Myth and reality of community ownership and control of community-managed piped water systems in Ghana. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 10(4), 841–850. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2020.099

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO]. (2020). The state of food and agriculture 2020. Overcoming water challenges in agriculture. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb1447en

- Fuentes-Castro, D., Carabias-Lillo, J., & Galaz, V. (2020). Co-management, community participation, and sustainability of common pool resources: An analysis of the literature. Sustainability Science, 15(3), 671–682.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). Ghana living standards survey round 7. Report on the district analytical report of the Bosomtwe district.

- Gondo, R., Kolawole, O. D., & Mbaiwa, J. E. (2019). Institutions and water governance in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment, 17(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10042857.2018.1544752

- Grafton, R. Q., Williams, J., Perry, C. J., Molle, F., Ringler, C., Steduto, P., Udall, B., Wheeler, S. A., Wang, Y., Garrick, D., & Allen, R. G. (2019). The paradox of irrigation efficiency. Science, 361(6404), 748–750. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat9314

- Hilson, G. (2019). Artisanal and small-scale mining, and sustainable development goals. Natural Resources Forum, 43(4), 271–281.

- Israel, M., & Hay, I. (2006). Research ethics for social scientists. Sage.

- Krause, T., Bach, M., Lindenschmidt, K. E., & Lorz, C. (2017). Perspectives on integrated water resources management–progress, challenges, and the way forward. Water, 9(10), 781.

- Manoranjitham, S. D., Rajkumar, A. P., Thangadurai, P., Prasad, J., & Jayakaran, R. (2007). Nature of suicidal ideation among rural farmers in Tamil Nadu, South India: A qualitative study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 53(5), 432–443.

- Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H. O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., & Shukla, P. R. (2022). Global warming of 1.5 C: IPCC special report on impacts of global warming of 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels in context of strengthening response to climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Cambridge University Press. https://dlib.hust.edu.vn/handle/HUST/21737

- Ministry of Sanitation and Water Resources [MSWR]. (nd). Water Resources Commission (WRC). Retrieved January 26, 2024, from http://mswr.gov.gh/water-resources-commission-wrc/

- Musie, W., & Gonfa, G. (2023). Fresh water resource, scarcity, water salinity challenges and possible remedies: A review. Heliyon, 9(8), e18685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18685

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

- Owusu, P. A., Asumadu-Sarkodie, S., & Ameyo, P. (2016). A review of Ghana’s water resource management and the future prospect. Cogent Engineering, 3(1), 1164275. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2016.1164275

- UN Water. (2018). The United Nations World Water Development Report 2018: Nature-based solutions for water. https://www.unwater.org/publication_categories/the-un-world-water-development-report-wwdr/

- UN Water. (2019). UN World Water Development Report 2019. https://www.unwater.org/publications/un-world-waterdevelopment-report-2019

- United Nations. (2021). Water facts and trends. https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/facts_and_figures.shtml

- United Nations Development Programme. (2019). Sustainable Development Goals: Goal 6—Clean water and sanitation. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-6-clean-water-and-sanitation.html

- World Bank. (2021). Ghana. World Bank Country Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ghana/overview

- World Economic Forum. (2023). The global risks report 2023. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf

- World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund. (2021). Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2020: Five years into the SDGs. WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030848