Abstract

Restorative justice is a theoretical framework used to address the issue of juveniles involved in criminal activities. This notion is prevalent in the Gampong settlement of Aceh region. The study investigates the efficacy of the Gampong settlement in mitigating the involvement of minors in criminal activities. The principles governing the resolution of criminal offenses within indigenous communities are comparable to the notion of restorative justice, which is currently implemented within the juvenile criminal justice system of Indonesia. The investigation was conducted at Langsa. Additionally, interviews were conducted with respondents and informants who were relevant to the subjects of the study. As stated in Qanun No. 9/2008 regarding the Progress of Traditional Way of Life and Customs in Aceh Qanun No. 10/2008 concerning customs institutions pertains to qanuns who honor and impart local knowledge in Langsa through the administration of customary criminal justice procedures involving minors involved in unlawful activities, as resolved through Gampong. Prior to undertaking legal settlement efforts, the settlement reached in the Gampong was the primary resolution. In the event that law enforcement officials resolve the case, they are still obligated to return it to the Gampong apparatus for further settlement. Gampong facilities continue to have a vibrant presence in the Langsa region in Aceh Province. By employing consensus deliberation, also referred to as restorative justice, a settlement based on local knowledge in Langsa achieves harmony through a win-win resolution.

Introduction

Children are the next generation of a nation and have a significant role in the progress of a nation in the future. A strong and healthy generation will form a strong country, and the destruction of the generation will damage the future of the country (Jabareen & Zlotnick, Citation2023). The role of the younger generation is in the struggle and progress of the nation in the future; therefore, increasing the role and importance of the younger generation must be accompanied by the goals, expectations, and desires of the state. The growth and development of a generation in the future is determined by the participation of all components of society, and Indonesia is a unitary state based on law (Rechtstaat) and not based on power alone (Ruhr & Jordan Fowler, Citation2022). Indonesia is a state of law that must be based on justice for its citizens. This means that all authorities and actions of state equipment or authorities are based solely on the law, so that they can reflect justice for the association of the life of its citizens (Bidandi & Williams, Citation2020). Restorative justice is a concept that resolves children in conflict with the law. This concept exists in the lowest legal communities led by an administrator Keuchik in the Aceh region called Gampong and examines the success of the Gampong settlement in reducing children in conflict with the law.

The results imply that restorative initiatives confront major obstacles. Bottom-up initiatives may find it difficult to gain acceptance and incorporation into other state agencies because they frequently lack the resources that come with institutional recognition. They run the danger of upsetting the communities from which they originated, if they were successful in their integration (Hobson & Payne, Citation2022).

Previous research has shown that community involvement in the resolution of children in conflict with the law is very important because children who commit delinquency can be influenced by their background in the community (Birckhead, Citation2016). The background of a child’s life that is not good in the family will cause anxiety for the child in living his life, such as a lack of affection in his life (Klebanov et al., Citation2023). Research suggests that children who experience trauma in society are more likely to blame themselves for their lives (Jabareen & Zlotnick, Citation2023). These findings provide an understanding of the excessive psychological impact experienced by certain victimized children experience (Klebanov et al., Citation2023).

The community’s role in resolving children is through deliberation. Settlement through deliberation is not new in Indonesia, because almost all cases can be resolved by deliberation (Gerson, Citation2022). The mediator in deliberation can be taken from trusted community leaders, and if the incident is at school, it can be done by the principal or teacher (Hobson & Payne, Citation2022; Kirkwood, Citation2022; Seo & Kruis, Citation2022). The main requirement for settlement through deliberation is the confession of the perpetrator and the consent of the perpetrator, his family and the victim to settle the case through deliberation (Ab Aziz et al., Citation2017; Gavrielides, Citation2008; Muhammad Hakim Nyak Pha, Citation1990).

Customs and customary law are among the most effective ‘directive tools’ in determining attitudes and behavior within the limits that have been justified by their customary law. There is Hadih Maja which reads: ‘Lampoh meu pageue umong meu ateueng (fenced garden fenced paddy field); Nanggroe meu syara’, maseng-maseng na Raja (The country has rules and each has a King)’ means that every thing has its institutional customs, and each field of work has certain rules according to its respective field (Muhammad Hakim Nyak Pha, Citation1990). Thus, customs and customary laws have become powerful tools for social control. In fact, some Acehnese, especially those who live and reside in rural areas far from public (official) judicial institutions, resolve almost every legal case and dispute between their fellow citizens through customary legal services. (Rahmi & Rizanizarli, Citation2020) throughout the legal journey shows that positive law is always left behind (Dupret, Citation2022) there is a strong tendency in society to obey the law because of the fear of negative sanctions if the law is violated (Kaufman, Citation2023). In Acehnese customary law, Hadih Maja Adat Bak Peteu Meureuhom is known as Acehnese customary philosophy, and in its writing, there are two versions:

Customs such as Poteu Meureuhom, Law like Syiah Kuala, Kanun like Putroe Phang, Reusam like Laksamana, and Lagee Zat ngon Sifeut Customary Law (Muhammad Hakim Nyak Pha, Citation1990).

Adat is like Poteu Meureuhom, Law is like ulama, Kanun is like putroe phang, Reusam is like Bentara, and Hukom ngon Adat is lagee alat ngon sifeut (Muhammad Hakim Nyak Pha, Citation1990). Hadih Maja Adat bak Poteu Meureuhom contains symbolic meaning regarding the content and implementation of Acehnese Customs (Muhammad Hakim Nyak Pha, Citation1990).

Literature review

Local wisdom of the acehnese people

Local wisdom is the cultural identity or personality of a nation that causes it to be able to absorb and even process culture originating from outside/other nations into its own character and abilities (Syafitri et al., Citation2019). This identity and personality certainly adapt to the worldview of the surrounding community, so that there is no shift in values. Local wisdom is a means of cultivating culture and defending oneself from bad foreign culture (Jahrir, Citation2020).

Local wisdom is a view of life and science, as well as various life strategies in the form of activities carried out by local communities in response to various problems in meeting their needs. In foreign languages, it is often conceptualized as local wisdom, knowledge, or genius (Syafitri et al., Citation2019). Local communities have implemented various strategies to maintain their culture.

Local wisdom is defined as a view of life and knowledge as well as a life strategy in the form of activities carried out by local communities in meeting their needs (Kartikawangi, Citation2016; Yang, et al., Citation2022) Local wisdom is customs and habits that have been traditionally carried out by a group of people for generations that are still maintained by certain customary law communities in certain areas (Rathnayake & Grodach, Citation2022; Sauri et al., Citation2022) Based on this understanding, it can be interpreted that local wisdom can be understood as local ideas that are wise, full of wisdom, good value, which are embedded and followed by members of the community (Dimyati et al., Citation2021).

Children in conflict with the law

Law No. 11/2012 on the Juvenile Justice System Article 1, Point 3. Children are 12 years old, but not yet 18 years old. In Article 1 of the Children’s Convention, the definition of a child is formulated as ‘every human being under the age of 18 years unless the law applicable to children provides that the age of majority is attained earlier’ (Cappa et al., Citation2023; Collins & Wright, Citation2022)

In Indonesia, the problem of children starts with the definition of a child, which concludes that a child is a human being who has not reached 18 years of age, including children who are still in the womb and are unmarried (Baumont et al., Citation2020; Wismayanti et al., Citation2019, Citation2021).

According to R. A. Kosnan, ‘Children are young people at a young age in their soul and journey of life because they are easily influenced by their surroundings’ (Cermak & Stanford, Citation2023). Therefore, children need to be taken seriously, but as the most vulnerable and weak social beings, they are often placed in the most disadvantaged position, do not have the right to a voice, and are often victims of acts of violence and violations of their rights (Mathuna et al., Citation2018).

Settlement of children against children in conflict with the law according to Qanun 9 of 2008 concerning the development of customary life and Gampong customs

The Indonesian legal system contains several main forms of law in its existence to realize dignified justice, which is a complementary law, as is the case in Aceh, which is part of the national legal system, whose relationship with one another is subject to legislation. In addition to these norms, the people of Aceh are also subject to customary provisions, which characterize the customary law that has existed since the Sultanate’s time. This can be seen in the philosophy of community life, namely ‘Adat bak po teumuruhom, hukom bak syiah kuala’, which means that laws and customs must go hand in hand in their application. This characteristic has generated strong interest from the community and local governments to make it a strong legal basis for the application of customary law, especially in Aceh. To fulfill this desire, Prime Ministerial Decree No. 1/Missi/1959 to the Province of Aceh, Aceh, was given the status of a Special Region in the fields of worship, religion, and education, meaning that worship is adat istiadat. The decree gave greater authority to the local government to develop, enforce, and maintain Adat/customs and institutions in Aceh’s social life. To implement the decree, the government issued Regional Regulation No. 2 of 1990 on the fostering and development of Adat Istiadat, community customs, and Adat institutions in the Special Region of Aceh. The development and nurturing of adats is left to the Gampong and Mukim, as well as existing and future adat institutions. Regulations concerning the application of adat are based on Law No. 44 of 1999 on the Implementation of Aceh’s Privileges, which according to article 3 (2) includes the organization of religious life, customary life, education and the role of the ulama in the establishment of regional policies.

Gampong itself is a legal community unit under the mukim and is led by a keuchik who has the right to organize his own household affairs (UU Republik Indonesia No.11 Th. 2006, Citation2006) The Keuchik of Gampong is elected directly from and by members of the community for a term of office of 6 (six) years and can be re-elected for another term of office. Langsa City has five sub-districts, consisting of 66 Gampongs:

West Langsa (13 villages)

Langsa City (10 villages)

Langsa Lama (15 villages)

Langsa Baro (12 villages)

East Langsa (16 villages)

Gampong is authorized to resolve disputes based on Law No. 11/2006 on the Government of Aceh, PERDA No. 7/2000 on the Implementation of Customary Life, Qanun No. 5/2003 on the Government of Gampong in the Province of Nangroe Aceh Darussalam, and the Joint Decree (SKB) between the Governor, Police Chief, and Aceh Customary Council No. 189/677/2011 dated 20 December 2011, on the Implementation of Gampong and Mukim Customary Courts.

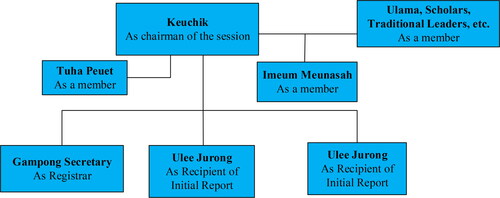

The leadership structure and role of customary justice organizers in the Gampong are as follows ().

This relates to judges’ decisions in cases of children in conflict with the law, especially theft. Keuchik decides the case based on the principle of kinship and considers the appropriate punishment for the child based on customary values and Islamic law. On the one hand, the child must be punished for his actions and, on the other hand, protected. Therefore, Keuchik as a judge is certainly required to be able to make a wise decision in deciding the dispute (Firman Zakaria et al., Citation2023).

Educational punishment is a form of punishment for children who violate law. For example, advice, reprimands, apologies, fines, compensation, being returned to the family and community for guidance, staying in dayah or similar institutions to study for a certain amount of time, cleaning meunasah, mosques, or other public facilities in the Gampong, becoming mu’azzin in the mosque or meunasah for a certain amount of time, memorizing Juz’Amma one part of Quran in a certain amount, if the child is transferred from the original Gampong to another place for educational purposes (Ikhsan, Citation2021).

Methodology

Object studied

The rules of law that exist in indigenous communities when resolving criminal offenses relate to the concept of restorative justice in the existing juvenile criminal justice system in Indonesia. This study was conducted at Langsa. Interviews were conducted with informants and respondents regarding the research topic.

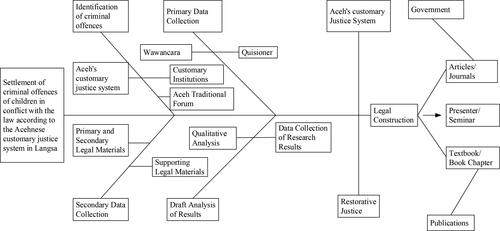

The research steps taken follow the research stages in the following flowchart image ().

Figure 2. Conceptual framework on Gampong settlement in restorative justice (April et al., Citation2023; Kirkwood, Citation2022).

The development, especially regarding the implementation of Customary Courts in Aceh, although the names of customary courts are not specifically found in settlements in villages, in reality, the people of Aceh continue to apply and maintain customary law to resolve customary issues or offenses. The existence of customary criminal courts in Aceh is evident from the existence of Qanun No. 9/2008 on the Development of Customary Life and Customs, and Qanun Aceh No. 10/2008 on Customary Institutions. Furthermore, at the district level, in the application of customary law, indigenous peoples use different legal bases from one another based on their respective cultural differences.

Data collection

In this study we sought information from the Aceh community that has long been using Gampong-level discourse as a custom when dealing with legal cases involving children as perpetrators. Before meeting the Gampong leaders in the city of Langsa, East Aceh, we have obtained permission to conduct interviews and data collection of restorative justice activity by the Gampong apparatus of each institution orally with the prior submission of A research assignment from the Universitas Sumatera Utara No.: 12/UN5.2.3.1/PPM/SKP/2021 including everything requested later. A few days before we arrived at the site, the scan letter of permission for research was sent to the head of the Gampong institute and waited until obtained leter permit/acceptance to come to meet for the necessary information as stated in letter No.971/261/2020 issued by the Pemerintah Kota Langsa Dinas Pemberdayaan Perempuan Perlindungan Anak Pengendalian Penduduk dan Keluarga Berencana (Langsa City Government, Women’s Empowerment Service, Child Protection, Population Control and Family Planning) as permission for the meeting. After that approval by Pemerintah Kota Langsa Kecamatan Langsa Baro Gampong Geudubang Jawa (Langsa City Government, Langsa Baro District, Gampong Geudubang Jawa) No. 470.1/917/2020. The results of the meeting with the Gampong leader are recorded and displayed in the results of this study. In terms of ethical considerations, the researchers also affirmed that all information provided in this research has been approved by the informants.

Before sending a letter to conduct research and visit we searched for Gampong data that is still applying restorative justice consistently. The information was obtained through friends and colleagues working in the field of Hisbah province enforcement Qanun, where the data was collected in the government of Aceh.

The respondent’s consent is to be published on the basis of a previously granted research permit containing the information required by the researcher from the respondent. After the visit and interview with the respondents, the Gampong apparatus will issue a statement that it has done research. The consent of the respondents was obtained in writing in accordance with the research permit letter which was answered by the respondent before carrying out the interview. Verbal consent was obtained at the time a few moments before conducting the interview and stating that the results of the study would be published in a journal that would be determined afterwards. The privacy of participants is rigorously protected. All data collected, including responses to surveys and any identifiable information, were anonymized and securely stored. Confidentiality measures were implemented to prevent the disclosure of individual identities or sensitive information.

Results and discussion

In Acehnese society, there is a wise saying or narit maja, which relates to the resolution of disputes in the legal context, namely ‘nyang rayek ta peu ubeuet, nyang ubeuet ta peu gadoeh’. In other words, complicated problems must be simplified, and simple problems must be eliminated. Instead of meupake goet ta meugoet, tanyoe laagee soet deungoen syedara, beule saba dalam hate, poe rabbol kade han geupeu deca. This means that instead of arguing, it is better to make peace, and we return to living as brothers and sisters. We must have a lot of patience, God the owner of nature forgives our sins.

Living in harmony with the Gampong community is like living with one father and one mother, and this sense of brotherhood is always reflected in the Gampong residents, so that disputes or disputes that occur in their midst are always sought to be resolved with the customary law that applies in the region. In formal juridical terms, customary dispute resolution in the Gampong has a legal umbrella that is firm and strong:

Law No. 44/1999 on the Implementation of the Specialty of the Special Province of Aceh

Law No. 11/2006 on the Government of Aceh

Law No. 6/2014 on Villages (Article 103)

Qanun No. 4 Year 2003 on Mukim Government

Qanun Number 5 Year 2003 on Gampong Government (Ps 3–4),

Aceh Qanun No. 9/2008 on the Development of Customary Life and Customs,

Aceh Qanun No. 10/2008 on Customary Institutions,

Aceh Governor Regulation No. 25/2011 on General Guidelines for the Implementation of Gampong Governance

Aceh Governor Regulation No. 60/2013 on the Implementation of Dispute Resolution of Adat and Istiadat.

Joint Decree (SKB) between the Governor of Aceh, the Aceh Regional Police, and the Aceh Customary Council No. 189/677/2011, dated December 20, 2011, on the Implementation of Gampong and Mukim Customary Courts.

The dispute resolution mechanism in the village in accordance with adats and customs, as mentioned above, is resolved in stages (Article 13, paragraph 2). This means that, as far as possible, the cases listed in Qanun Aceh No. 9/2008 on the Development of Customary Life and Customs Article 13 are settled first at the Gampong judicial level by officials of Gampong. It should also be mentioned that legal issues that can be resolved in the Gampong according to the qanun include disputes or disagreements. The term dispute refers to civil cases, while dispute refers to criminal cases. This is understandable because, from the perspective of Customary Law, there is no distinction between criminal law and civil law, as known in the Law of Legislation.

Based on the results of interviews with the community in Teukan Langsa village, it is stated that every criminal offense committed by children will be resolved based on existing customs in the village. The keuchik’s duty to conduct customary justice to resolve disputes is also regulated by Aceh Qanun No. 10/2008 on Customary Institutions. Article 15, paragraph (1), letters j and k of this qanun state that the Keuchik is in charge of leading and resolving social community problems and being a reconciler for disputes between residents in the Gampong. With the above provisions, it is clear that the head of the village in Aceh (Keuchik) has legal and official authority that is strictly regulated in the legislation (qanun) and elaborated upon in the governor’s regulation.

Technically operational procedures for customary dispute resolution in the village include disputes that occur at the village level, and police officers provide an opportunity for any disputes referred to in the first dictum to be resolved first through the Gampong and Mukim Customary Courts or other names in Aceh. All parties should respect the implementation of the Gampong and Mukim Customary Courts or other names in Aceh. The Gampong and Mukim Customary Courts or other names in Aceh for resolving and providing decisions are based on the norms of Customary Law and customs prevailing in the local area. Trials of the Gampong and Mukim Customary Courts or other names in Aceh are attended by the parties, witnesses, and are open to the public, except for certain cases that, according to custom and propriety, may not be open to the public and are free of charge. Decisions of the Gampong and Mukim Customary Courts or other names in Aceh are final and binding, and cannot be submitted again to the general court. Every decision of the Gampong and Mukim Customary Courts or other names in Aceh shall be in writing, signed by the Chairperson and Members of the Tribunal, as well as both parties to the dispute, and shall be copied to the Head of the Sector Police, the Sub-District Head, and the Aceh District Customary Council.

In the case of minor crimes committed by children, the stage of case settlement is reported by the victim or both parties to the head of the Jurong where the legal incident occurred, and then the head of the Jurong reports to the Keuchik. As soon as Keuchik receives the report from the head of the Jurong or from the victim, the holds an internal meeting with the secretary to determine the hearing schedule. The report should not be made in any place, such as a coffee shop or market, but must be made in a closed place, such as at home or in a meunasah. Before the trial is held, Keuchik and his apparatus (secretary keuchikatau secretary Gampong, imuem meunasah, and heads of jurong) approach both parties, aiming to determine the real situation of the case and, at the same time, ask for their willingness to be resolved amicably. During this approach, customary court administrators would use various methods of mediation and negotiation to resolve the case.

Approaches are not only made by the keuchik and his officials but can also be made by anyone who is considered close and respected by the parties. In cases where the victim is a woman or young person, the approach is usually taken by the keuchik’s wife or other female Tuha Peut members who are close to the victim or both parties.

If both parties agreed to an amicable settlement, the keuchikakan secretary formally invited them to attend the hearing on the set day and date.

At the time of hearing, parties may be represented by their guardians or other relatives as spokespersons.

The trial is formal and open for major cases, which are usually held in meunasahats or other places that are considered neutral for both parties.

The time required for completion cannot exceed 9 days. win-win solution decision If, within the time limit determined by the keuchik as head of the Gampong, the case does not follow up, then the disputing parties are allowed to take formal legal action. The pattern of resolving disputes/disputes based on Acehnese legal culture, as stated above, has implications, on the one hand, for strengthening Gampong autonomy and at the same time reducing the workload of law enforcement officers.

The exceptions to criminal acts that are not carried out are rape and murder, because they cause very serious victims, so cases of rape and murder must be legally included. The following are data on cases that were still pending before the Langsa customary court.

The data in show that children who committed serious offences were resolved in the Gampong process but proceeded to the general court for their offences. In . Rape cases were an exception, with one case resolved in the Gampong and not proceeding to the formal legal process.

Table 1. Children in conflict with the law.

From cases elsewhere handled by the Gampong, a number of children were processed for theft and did not proceed to the formal legal process. Skills such as deliberation, careful listening, speaking clearly, and ensuring effective communication between all parties are essential for all parties involved in adat justice.

Conclusion

Qanun No. 9/2008 on the Development of Customary Life and Customs and Aceh Qanun No. 10/2008 on Customary Institutions are qanuns that provide and honor local wisdom in Langsa by implementing customary criminal justice processes for children in conflict with the law in the settlement of Gampong. The settlement in the Gampong is the main settlement that must be done before legal settlement efforts are made, even when the case has been handled by law enforcement officials must return it to the Gampong apparatus for settlement. The Gampong courts in Langsa are alive. Settlement with local wisdom in Langsa uses a restorative justice approach, better known as consensus deliberation, to realize peace with a win-win solution.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Marlina: Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Mahmud Mulyadi: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the funders of the Universitas Sumatera Utara, the City Government of Langsa Aceh, Keuchik Gampong, Wilayatul Hisbah and citizen participants who assisted in data collection. We thank them for the encouragement and contribution to our thinking on this important issue.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. The data obtained by interviews from sources has been approved for distribution, because before conducting interviews the author has first shown a letter of permission to conduct interviews and collect data from the Universitas Sumatera Utara as an institution that funds this research. The research permit letter shown to the interviewee is in the appendix of the document in the form of a scanned document. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Marlina, upon reasonable request. Research data can be obtained on the Google Drive link with the URL: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1sL-nmsQI_mkjqCBUfbl-SSLN7_vAvy_C?usp=sharing

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marlina

Marlina is a lecturer and researcher in Faculty of law Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia. Completed his doctorate in 2006 from Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia. His research interests relate to criminal law, criminal law policy, child diversion, restorative justice and the juvenile criminal justice system. Email: [email protected].

Mahmud Mulyadi

Mahmud Mulyadi graduated with a doctorate in 2006 from Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan Indonesia. He is a lecturer in Faculty of law Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia. His research interests relate to criminal law and criminal law policy. Email: [email protected].

References

- Ab Aziz, N., Mohamad Amin, N., & Ab Hamid, Z. (2017). Restorative justice as an alternative criminal dispute resolution for the offence of theft. IJASOS- International E-Journal of Advances in Social Sciences, III(7), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.18769/ijasos.320061

- UU Republik Indonesia No.11 Th. 2006. (2006). 1 Statue 21. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.20120011

- April, K., Schrader, S. W., Walker, T. E., Francis, R. M., Glynn, H., & Gordon, D. M. (2023). Conceptualizing juvenile justice reform: Integrating the public health, social ecological, and restorative justice models. Children and Youth Services Review, 148(November 2021), 106887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.106887

- Baumont, M., Wandasari, W., Agastya, N. L. P. M., Findley, S., & Kusumaningrum, S. (2020). Understanding childhood adversity in West Sulawesi, Indonesia. Child Abuse & Neglect, 107(October 2019), 104533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104533

- Bidandi, F., & Williams, J. J. (2020). Understanding urban land, politics, and planning: A critical appraisal of Kampala’s urban sprawl. Cities, 106(July 2020), 102858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102858

- Birckhead, T. (2016). The racialization of juvenile justice and the role of the defense attorney. Boston College Law Review. Boston College. Law School, 58(2), 379. https://ezp.waldenulibrary.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=122552222&site=eds-live&scope=site

- Cappa, C., Cecchetti, R., & Jijon, I. (2023). Ending violence against children: A new international standard to foster data availability. Child Abuse & Neglect, 144(June), 106330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106330

- Cermak, T. L., & Stanford, M. (2023). The impacts of cannabis on adolescent psychological development. In B. Halpern-Felsher (Ed.), Encyclopedia of child and adolescent health (1st ed., pp. 211–221). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818872-9.00072-8

- Collins, T. M., & Wright, L. H. V. (2022). The challenges for children’s rights in international child protection: Opportunities for transformation. World Development, 159, 106032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106032

- Dimyati, K., Nashir, H., Elviandri, E., Absori, A., Wardiono, K., & Budiono, A. (2021). Indonesia as a legal welfare state: A prophetic-transcendental basis. Heliyon, 7(8), e07865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07865

- Dupret, B. (2022). The concept of positive law and its relationship to religion and morality. In M.-C. Foblets, M. Goodale, M. Sapignoli, & O. Zenker (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of law and anthropology (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198840534.013.22

- Firman Zakaria, C. A., Mahmud, A., & Mulyana, A. (2023). Legal protection for child victims of sexual assault in a restorative justice perspective. Jurnal Penelitian Hukum De Jure, 23(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.30641/dejure.2023.V23.59-70

- Gavrielides, T. (2008). Restorative justice-the perplexing concept: Conceptual fault-lines and power battles within the restorative justice movement. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 8(2), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895808088993

- Gerson, J. C. (2022). Restorative justice and alternative systems. In L. R. Kurtz (Ed.), Encyclopedia of violence, peace, & conflict (3rd ed., pp. 125–136). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820195-4.00161-8

- Hobson, J., & Payne, B. (2022). Building restorative justice services: Considerations on top-down and bottom-up approaches. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 71(September), 100555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2022.100555

- Ikhsan, M. (2021). Role and action of Tuha Peut in guiding children with the law in north Aceh regency. JICOMS, 1(1), 38–52. https://journal.iainlhokseumawe.ac.id/index.php/jicoms/article/view/275/152

- Jabareen, R., & Zlotnick, C. (2023). The personal, local and global influences on youth sexual behaviors in a traditional society. Children and Youth Services Review, 149(March), 106947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.106947

- Jahrir, A. S. (2020). Character education of Makassar culture as a local wisdom to streng then Indonesian diversity in schools. In. Multicultural Education, 6 Issue(1), 10–165.

- Kartikawangi, D. (2016). Symbolic convergence of local wisdom in cross – cultural. Public Relations Review, 43(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.10.012

- Kaufman, W. R. P. (2023). Introduction. In Beyond legal positivism: The moral authority of law (pp. 1–26). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43868-4_1

- Kirkwood, S. (2022). A practice framework for restorative justice. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 63, 101688.

- Klebanov, B., Tsur, N., & Katz, C. (2023). “Many bad things had been happening to me”: Children’s perceptions and experiences of polyvictimization in the context of child physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 145(March), 106429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106429

- Mathuna, P. O D., Dranseika, V., & Gordijn, B. (2018). Disaster: Core concepts and ethical theories. In Advancing global bioethics (Vol. 11). Springer. http://www.springer.com/series/10420

- Muhammad Hakim Nyak Pha. (1990). Pedoman Umum Adat Aceh. LAKA Aceh, 171.

- Rahmi, I., & Rizanizarli, R. (2020). Penerapan Restorative Justice Dalam Penyelesaian Tindak Pidana Pencurian Oleh Anak Dalam Perspektive Adat Aceh. Syiah Kuala Law Journal, 4(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.24815/sklj.v4i1.16876

- Rathnayake, S. R., & Grodach, C. (2022). Transformation and tensions in the Sri Lankan brassware industry: Lessons for craft industry clusters in the global South. City, Culture and Society, 31(September), 100476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2022.100476

- Ruhr, L. R., & Jordan Fowler, L. (2022). Empowerment-focused positive youth development programming for underprivileged youth in the Southern U.S.: A qualitative evaluation. Children and Youth Services Review, 143(September), 106684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106684

- Sauri, S., Gunara, S., & Cipta, F. (2022). Establishing the identity of insan kamil generation through music learning activities in pesantren. Heliyon, 8(7), e09958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09958

- Seo, C., & Kruis, N. E. (2022). The impact of school’s security and restorative justice measures on school violence. Children and Youth Services Review, 132(October 2020), 106305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106305

- Syafitri, E. M., Indrasari, F., Lisdiantini, N., Thousani, H. F., Muarief, R., & Setiawan, A. D. (2019). Character education based-on local wisdom in excellent service course. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 354(iCASTSS), 365–368. https://doi.org/10.2991/icastss-19.2019.76

- Wismayanti, Y. F., O’Leary, P., Tilbury, C., & Tjoe, Y. (2019). Child sexual abuse in Indonesia: A systematic review of literature, law and policy. Child Abuse & Neglect, 95(May), 104034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104034

- Wismayanti, Y. F., O’Leary, P., Tilbury, C., & Tjoe, Y. (2021). The problematization of child sexual abuse in policy and law: The Indonesian example. Child Abuse & Neglect, 118(May), 105157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105157

- Yang, S., Kuo, B. C. H., & Lin, S. (2022). Wisdom, cultural synergy, and social change: A Taiwanese perspective. New Ideas in Psychology, 64, 100917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2021.100917