Abstract

In response to global calls for environmentally sustainable and socially equitable agriculture, this study examines the socio-psychological factors influencing smallholder farmers in Sikkim, India, to adopt sustainable agricultural practices (SAP). Traditional agricultural methods prioritize productivity over ecological sustainability. SAP addresses this challenge holistically by considering environmental, social, and economic factors. The factors that influence smallholder farmers’ SAP adoption, especially in unique regional contexts, are poorly understood. This study uses the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and social norms theory to examine SAP adoption’s socio-psychological aspects. Sikkim’s sociocultural and agroecological characteristics are studied. Findings show that attitudes (ATs), social norms and perceived behavioral control (PBC) shape SAP adoption intentions (INs), with gender-specific dynamics, age-related nuances and complex socioeconomic factors. This study answers the comprehensive question: ‘What socio-psychological factors influence smallholder farmers in Sikkim, India, to adopt Sustainable Agricultural Practices?’ using quantitative surveys and PLS-SEM analysis of 407 smallholder farmers. In broader conclusion, the study suggests local governments, NGOs, development practitioners, researchers and stakeholders tailor sustainability interventions. This socio-psychological study addresses critical SAP adoption gaps by shifting from behavioral analyses. The main takeaway is that interventions must consider smallholder farmers’ diverse motivations and contextual factors when adopting SAPs. This study advances regional literature and sustainable agriculture discourse, promoting a socially equitable agricultural future.

Impact Statement

Our study explores why smallholder farmers embrace sustainable agricultural practices (SAPs) in the heart of Sikkim’s landscapes. Beyond local horizons, it contributes to the global shift toward eco-conscious farming. Our insights are not confined to academia; they guide policymakers, local authorities and NGOs, shedding light on factors influencing farming decisions and paving the way for sustainable practices. Our study is a valuable resource for fellow researchers and sustainability enthusiasts, bridging disciplines and expanding perspectives on sustainable agriculture. In essence, it is a sociological journey, a call to action and a harmonious melody echoing the dreams of small farmers and envisioning a sustainable agricultural future.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Sustainable agricultural practices (SAP) have emerged as a focal point for creating agricultural systems that harmonize ecological resilience, economic viability and societal well-being (Yang et al., Citation2022). Techniques encompassing crop residues, water and soil conservation, crop rotations, improved seed types and the utilization of animal manure aim to foster climate-friendly and sustainable agricultural systems (Setsoafia et al., Citation2022). In this context, SAP refers to a set of environmentally conscious, socially equitable and economically viable farming methods and techniques farmers adopt to promote agricultural ecosystems’ long-term health and resilience. SAP encompasses a holistic approach that considers ecological, economic and social dimensions to ensure the sustainability and resilience of agricultural systems, particularly in the context of Sikkim, India (Meek & Anderson, Citation2019; Serebrennikov et al., Citation2020).

Despite significant efforts by research and development organizations to bolster the sustainable development of smallholder agricultural systems (Mutyasira et al., Citation2018; Shi & Gill, Citation2005; Teklewold et al., Citation2013), the widespread adoption of conservation methods, particularly among smallholder farmers globally, remains a challenge (Bopp et al., Citation2019; Fielding et al., Citation2008; Knowler & Bradshaw, Citation2007). This highlights a critical knowledge gap concerning the factors influencing farmers’ acceptance of SAP.

While extant literature has explored various social, structural, and agricultural production factors influencing farmers’ farm-level adoption decisions, there has been a conspicuously limited focus on assessing farmers’ willingness to engage in SAP and the underlying variables shaping their conservation behavior (Ahnström et al., Citation2009; Neill & Lee, Citation2001; Pham et al., Citation2021). Traditional economic theories, which often underpin such analyses, fail to comprehensively explain farmer conservation behavior, as these decisions are not solely driven by economic rationality (Serebrennikov et al., Citation2020; Stern, Citation2000).

The crucial role of non-economic and intrinsic factors, such as attitudes (ATs), norms and stewardship motives, is increasingly evident in farmers’ decision-making processes. Consequently, interventions targeting farmers’ behavior are deemed necessary to promote the adoption of SAP (Sok et al., Citation2021). Behavioral approaches have gained prominence in studying farmers’ pro-environmental behavior, adoption of conservation technologies, organic farming and perceptions of SAP (Sok et al., Citation2021).

This study addresses the nuanced interplay between ecological, economic and human factors in adopting SAP. It moves beyond traditional economic paradigms, delving into the intricate human dynamics that shape agricultural decisions. Guided by the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the research explores the influential factors of ATs, subjective norms (SNS) and perceived behavioral control (PBC; Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). Beyond TPB, the study incorporates social norms theory, capturing shared perceptions regarding SAPs within social groups.

Sikkim, India, known for its diverse agricultural practices, provides the backdrop for this significant study, marking a distinctive contribution in the region’s research landscape (Bhujel & Joshi, Citation2023). Employing a three-stage sampling technique, the survey instrument aligns with TPB constructs, capturing ATs, social norms and PBC. Demographic factors enrich the analysis, providing a nuanced perspective. Analytically, the study employs Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), offering a socio-psychological lens.

Within the rich tapestry of literature on SAP, a noticeable gap emerges – the sidelining of behavioral variables in understanding adoption dynamics. This study advocates for inclusivity by incorporating social norms, a critical socio-psychological dimension often overlooked. By bridging past limitations, integrating behavioral variables and introducing the socio-psychological dimension of social norms, this study broadens the methodological scope, positioning itself within a socio-psychological framework.

Moving beyond a traditional behavioral analysis, this article situates itself within a socio-psychological framework, recognizing the pivotal role of norms in guiding behavior. It aims to unravel the complex interplay between individual ATs, PBC and normative influences. In navigating the terrain of sustainable agriculture, this study is the first of its kind in Sikkim, addressing the gap in regional literature. Departing from behavior-centric analyses, the study recognizes gaps in socio-psychological dimensions and the limited exploration of collective influences. Seamlessly integrating TPB and social norms theory, this research offers a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted forces influencing SAP adoption, contributing significantly to the broader landscape of social science.

1.2. Background of the study: unveiling the complexities of SAP adoption

The exploration of SAPs adoption has been a focal point of extensive research, marked by diverse perspectives and methodological approaches. Within this expansive landscape, studies have predominantly gravitated toward economic and agronomic facets, leveraging statistical models to elucidate macro-level determinants like economic incentives and environmental conditions (Ghimire et al., Citation2015; Long et al., Citation2016; Manda et al., Citation2016; Piñeiro et al., Citation2020; Teklewold et al., Citation2013; Van Thành & Yapwattanaphun, 2015).

In contrast, a distinct strand of research, rooted in behavioral economics or psychology, has delved into the intricate human dynamics inherent in SAP adoption. These studies, anchored in models, such as the TPB, investigate ATs, SN and PBC to offer a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted factors influencing farmers’ decisions (Cakirli Akyüz & Theuvsen, Citation2020; Daxini et al., Citation2018; Lalani et al., Citation2016; Mutyasira et al., Citation2018; Nguyen et al., Citation2021).

However, a notable gap persists in integrating these diverse perspectives comprehensively. This study endeavors to bridge this gap by adopting a socio-psychological lens enriched by TPB and social norms theory (Elahi et al., Citation2021; Zeweld et al., Citation2018). In acknowledging the strengths of both approaches, the research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of SAP adoption in the distinctive context of Sikkim, India. The socio-cultural fabric of Sikkim introduces unique nuances, necessitating a more profound exploration to inform targeted and effective interventions, aligning with the broader objective of fostering a socially equitable agricultural future in the region.

The identified gap in existing research on SAP adoption is particularly significant in the underrepresentation of sociological dimensions. While studies have made valuable contributions by predominantly focusing on economic and agronomic facets or delving into behavioral economics and psychology, there’s often a notable omission of a robust sociological perspective (Zeweld et al., Citation2018).

The sociological dimension encompasses factors, such as community dynamics, social norms and broader contextual variations that play a crucial role in shaping individual behaviors and decisions. The relative lack of attention to these sociological aspects in the existing body of literature creates a gap in our understanding of SAP adoption. This gap hinders a comprehensive grasp of the interplay between macro-level determinants, individual-level behavioral factors and the sociocultural fabric within which these decisions unfold (Serebrennikov et al., Citation2020; Zeweld et al., Citation2018).

Our research seeks to address this gap by deliberately incorporating a socio-psychological lens enriched by both the TPB and social norms theory. By doing so, our study aims to contribute to the broader literature by providing insights into the sociological nuances of SAP adoption, particularly in the specific context of Sikkim, India. This approach is vital for a holistic understanding of the complexities surrounding farmers’ decision-making processes and aligns with the broader goal of fostering socially equitable and SAPs.

The subsequent sections will intricately explore the theoretical background, conceptual framework and hypotheses, marking a methodological and conceptual shift toward a socio-psychological perspective. The literature review, methods, results, discussion and conclusion will further unravel the complexities surrounding SAP adoption, enriching the discourse on sustainable agriculture in the region.

2. Research question

This study aims to uncover the socio-psychological factors influencing the adoption of SAPs among smallholder farmers in Sikkim, India. The central research question guiding this investigation is: ‘What socio-psychological factors influence smallholder farmers in Sikkim, India, in their adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices?’

Within the unique regional context of Sikkim, where cultural and agroecological intricacies shape agricultural practices, this research seeks to comprehensively understand the complex dynamics that drive or impede the adoption of SAP. By employing the TPB enriched with social norms theory, the study aims to explore the ATs, social norms and PBC that play pivotal roles in shaping farmers’ intentions (INs) to embrace SAPs. The investigation encompasses a diverse range of factors, including gender-specific dynamics, age-related variations and the socio-economic landscape, contributing to a detailed and context-specific understanding of SAP adoption among smallholder farmers.

3. Objectives

This research aims to comprehensively explore factors influencing the adoption of SAP among smallholder farmers in Sikkim, India, integrating insights from the TPB and sociopsychological dynamics. The objectives are as follows:

Evaluate SAP adoption intentions and influential factors: Assess smallholder farmers’ INs to adopt SAP, concurrently examining the impact of ATs, social norms and PBC. Analyze direct relationships and how demographic factors moderate these relationships within the TPB framework and sociopsychological dynamics.

Understand the mediation role of social norms: Specifically explore the mediating role of social norms in shaping the relationship between individual ATs and INs, as well as PBC and INs. This comprehensive examination will contribute to a nuanced understanding of the sociological underpinnings of the adoption process.

Explore demographic variations: Conduct a multi-group analysis to assess variations in direct relationships across different demographics, exploring nuanced responses to the TPB framework and the moderating effects of demographics. Provide tailored insights for diverse population segments, aligning with sociological underpinnings.

4. Literature review

4.1. Theoretical framework

4.1.1. Adoption and diffusion of sustainable agricultural practices (SAP)

Before delving into the theoretical underpinnings, clarifying the concepts of Adoption and Diffusion within the SAPs context is essential.

Adoption refers to farmers’ deliberate and sustained integration of SAP into their farming systems (Wangithi et al., Citation2021). It involves the conscious decision to implement and persist with ecologically sustainable, economically viable and socially equitable agricultural methods. In this study, SAP adoption encompasses the acceptance and consistent application of these practices (Lastiri-Hernández et al., Citation2020; Mishra et al., Citation2018; Syan et al., Citation2019; Tey et al., Citation2014; Zeweld et al., Citation2017).

Diffusion in the context of SAP pertains to spreading and disseminating these practices among farmers in a specific region or community. It involves how other farmers communicate, accept and adopt SAP knowledge, innovations and techniques beyond the initial adopters. In this study, diffusion captures how SAP knowledge and practices proliferate among farmers, contributing to the broader adoption landscape (Myeni et al., Citation2019).

4.1.2. Choice of theoretical framework

With a clear understanding of SAP adoption and diffusion, selecting an appropriate theoretical framework becomes crucial. Several existing theories could inform the understanding of behaviors related to SAPs, including the Theory of Reasoned Action, Diffusion of Innovations Theory, Social Cognitive Theory, Health Belief Model, Innovation-Decision Process, Ecological Rationality and various Environmental Psychology theories. Each theory offers unique insights into human behavior, but the choice depends on the specific nuances of the behavior under investigation (Anibaldi et al., Citation2021; Cakirli Akyüz & Theuvsen, Citation2020).

The TPB emerges as the preferred theoretical framework for this study. TPB is chosen for its well-established psychological foundations and robust predictive power. Its adaptability to pro-environmental behavior, incorporation of social norms and versatility in accommodating diverse contextual factors align closely with the intricacies of SAP adoption (Ajzen, Citation2020; Atta‐Aidoo et al., Citation2022; Savari & Gharechaee, Citation2020).

TPB aligns seamlessly with the objectives of this study, providing a suitable framework for delving into the multifaceted factors influencing SAP adoption. By emphasizing the psychological determinants of behavior, TPB offers a lens to explore the motivations, ATs and social influences shaping farmers’ decisions in Sikkim (Borges et al., Citation2019; Nguyen et al., Citation2021).

Recognizing the significance of social influences, social norms theory is integrated with TPB to enhance the study’s analytical depth. This combination captures the communal context, emphasizing the role of social norms in shaping behavioral INs, especially within the context of SAPs (Daxini et al., Citation2018; Fielding et al., Citation2008; Menozzi et al., Citation2015; Nguyen et al., Citation2021).

In conclusion, the chosen theoretical framework, primarily anchored in TPB and supplemented by social norms theory, lays the groundwork for a comprehensive exploration of SAP adoption in Sikkim. The subsequent sections on methodology and analysis will build upon this theoretical foundation to unravel the nuanced dynamics of farmers’ decision-making processes.

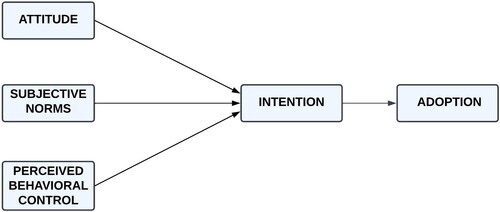

4.1.3. Theory of planned behavior (TPB)

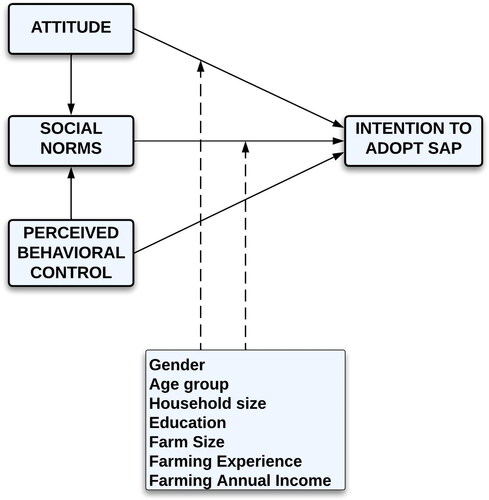

The theoretical framework guiding this study draws on the TPB shown in , developed by Ajzen (Citation1991). TPB posits that individual INs to adopt specific behaviors, such as SAPs, are shaped by three core constructs: ATs, SN (referred to as social norms in our conceptual model) and PBC (Ajzen, Citation2020; Savari & Gharechaee, Citation2020; Wang & Lin, Citation2020).

Figure 1. Theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991).

Attitudes (ATs): ATs reflect individuals’ positive or negative behavior evaluations. Farmers’ ATs encompass perceptions of the benefits and costs associated with sustainable practices in the context of SAP adoption. Positive ATs are anticipated to foster higher INs to adopt SAP (Mishra et al., Citation2018; Waseem et al., Citation2020).

Subjective norms (SNS): SNS represent the influence of perceived social norms on INs. As integral components of this study, social norms are shared expectations within a community regarding appropriate behavior. In agriculture, SNS include perceived expectations from family, friends and the community regarding adopting sustainable practices (Dessart et al., Citation2019; Govindharaj et al., Citation2021).

Perceived behavioral control (PBC): PBC refers to individuals’ perceptions of the ease or difficulty of performing a behavior. The SAP adoption context encompasses knowledge, skills and resource accessibility. Farmers’ perceptions of their ability to integrate sustainable practices into their routines influence their INs (Roesch‐McNally et al., Citation2017; Savari & Gharechaee, Citation2020).

4.1.4. Social norms theory

Complementing TPB, this study incorporates social norms theory to emphasize the role of communal influence on individual behavior (Fielding et al., Citation2008).

Observational learning: social norms theory acknowledges observational learning, where farmers observe and learn from others who have successfully adopted SAP. Positive outcomes and visible successes motivate adoption, highlighting the influence of observational learning in the agricultural community (Waseem et al., Citation2020).

Social norms as social capital: Social norms are considered a form of social capital, aligning with social norms theory. Strong social norms within a community act as catalysts for collective action, fostering collaboration among farmers and promoting the adoption of sustainable practices as a shared endeavor (Yaméogo et al., Citation2018; Zhou et al., Citation2023).

4.1.5. Sociological perspectives

To enrich the sociological dimensions of the study, the theoretical framework incorporates influential sociological perspectives.

Symbolic interactionism: Rooted in Mead and Blumer’s work, symbolic interactionism examines how individuals attribute meaning to symbols and engage in social interactions. In the context of SAP adoption, symbolic meanings associated with sustainable practices influence decisions, demonstrating that the adoption of SAP is not merely a practical decision but one imbued with symbolic significance (Tey et al., Citation2014; Waseem et al., Citation2020).

Social exchange theory: Social exchange theory, developed by Homans and expanded by Blau, frames social interactions as transactions characterized by reciprocity. In SAP adoption, farmers’ decisions may be influenced by perceived benefits received from the community in return for adopting sustainable practices, emphasizing the importance of reciprocal relationships (Foguesatto et al., Citation2020; Tiefigue Coulibaly et al., Citation2021).

Social constructionism: Social constructionism focuses on how shared meanings construct social realities. In SAP adoption, the study considers how shared interpretations of sustainability influence adoption behaviors. The decision to adopt SAP is shaped collectively, highlighting the role of shared understanding within the community (Foguesatto et al., Citation2020; Tiefigue Coulibaly et al., Citation2021).

4.1.6. Integration of social norms as mediators

Extending TPB, this study considers social norms as mediators between ATs and INs and between PBC and INs. This nuanced approach acknowledges the sociological underpinnings of TPB. It explores the interplay between individual ATs, community norms and perceived control in shaping farmers’ INs to adopt SAP (Anibaldi et al., Citation2021; Mutyasira et al., Citation2018).

In summary, the integrated theoretical framework of TPB and social norms theory, enriched by sociological perspectives, provides a comprehensive lens for analyzing the psychological and sociological factors influencing farmers’ decisions to adopt SAPs in Sikkim. The following section will delve into the conceptual literature, exploring the principles and practices associated with sustainable agriculture and the role of social norms as a form of social capital.

4.2. Conceptual framework

illustrates our conceptual framework, centering on the TPB as the foundational psychological framework, emphasizing individual ATs, PBC and SN. This framework seamlessly integrates social norms theory, introducing a communal dimension that underscores the mediating role of social norms between individual ATs and INs and PBC and INs. This integration recognizes the communal nature inherent in decision-making processes.

Furthermore, influential sociological perspectives, including symbolic interactionism, social exchange theory and social constructionism, enhance the framework by contributing to a broader socio-cultural context. These perspectives deepen our understanding of symbolic meanings, reciprocal relationships and shared interpretations within the community, broadening the study beyond individual psychological factors. This nuanced approach appreciates the sociological underpinnings of TPB, facilitating a comprehensive exploration of the intricate interplay between individual and communal factors in shaping farmers’ INs to adopt SAPs.

The conceptual framework positions social norms as mediators between ATs and INs and between PBC and INs. This nuanced approach acknowledges the sociological underpinnings of TPB, delving into the complex interplay between individual ATs, community norms, and perceived control in shaping farmers’ INs to adopt SAP. This framework will guide the empirical data analysis, offering a comprehensive lens to understand the multifaceted factors influencing SAP adoption in Sikkim, India’s distinctive agricultural and cultural context.

4.3. Hypotheses development

4.3.1. Research hypotheses

4.3.1.1. Attitudes (ATs)

ATs reflect an individual’s overall evaluation and emotional disposition toward SAP adoption. Prior research has consistently affirmed the pivotal role of positive ATs in shaping behavioral INs (Ajzen, Citation1991; Tama et al., Citation2021). Farmers with favorable ATs are more likely to embrace SAP, considering the positive correlation between ATs and behavioral INs (Atta‐Aidoo et al., Citation2022; Mutyasira et al., Citation2018).

Hypothesis 1

(H1): Positive ATs significantly influence the adoption IN of SAP (IN), indicating that farmers with more favorable ATs are expected to demonstrate a higher propensity to adopt these practices.

Hypothesis 2

(H2): Positive ATs significantly influence social norms (SN), with farmers perceiving social pressure and encouragement being more likely to engage in SAP.

4.3.1.2. Perceived behavioral control (PBC)

PBC indicates an individual’s belief in their ability to control and engage in SAP adoption. The research underscores the significance of perceived control in influencing behavioral INs (Ajzen, Citation1991; Tama et al., Citation2023). Farmers who feel more control over engaging in SAP adoption are expected to have a higher tendency to adopt these practices (Atta‐Aidoo et al., Citation2022; Senger et al., Citation2017).

Hypothesis 3

(H3): Positive PBC significantly influences the adoption IN of SAP (IN), as farmers who perceive a higher degree of control are expected to have a higher tendency to adopt these practices.

Hypothesis 4

(H4): Positive PBC significantly influences social norms (SN), indicating that farmers with a higher perceived control are more likely to perceive societal encouragement and pressure to adopt SAP.

4.3.1.3. Social norms (SN)

Social norms represent the perceived social pressure compelling an individual to engage in SAP adoption. Extensive literature suggests that societal expectations and normative influences are crucial in shaping behavioral INs. Farmers who perceive societal encouragement and pressure to adopt SAP are likelier to engage in these practices (Cakirli Akyüz & Theuvsen, Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2018).

Hypothesis 5

(H5): Positive social norms (SN) significantly influence the adoption of SAP (IN), with farmers perceiving social pressure and encouragement being more likely to engage in these practices.

4.3.2. Additional hypotheses

In addition to the direct effects, the study explores mediation effects to unravel the nuanced dynamics of SAP adoption.

4.3.2.1. Mediation hypotheses

Hypothesis 6

(H6): ATs influence IN through the mediation of social norms. Farmers with positive ATs are expected to have higher IN scores, and the influence of social norms mediates this relationship (Anuar et al., Citation2019; Xilin et al., Citation2022).

Hypothesis 7

(H7): PBC influences IN through the mediation of social norms. Farmers with a higher sense of control are expected to have higher IN scores, and the influence of social norms mediates this relationship (Wollast et al., Citation2021).

5. Methods

Our research methodology unfolds through a meticulously crafted sequence of four strategic steps; each systematically devised to unveil the intricacies of the sociopsychological landscape.

5.1. Description of the study area

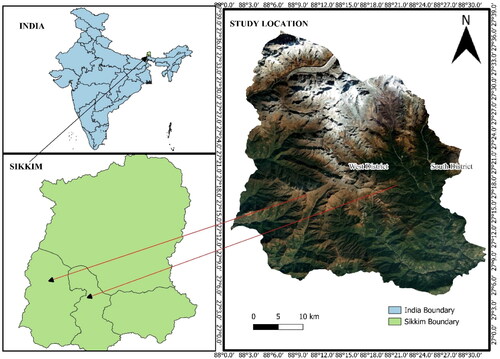

Step 1: Study location definition

The research is centered in Sikkim, India, chosen for its diverse agricultural landscape and notable sustainability initiatives. Sikkim’s socioeconomic and ecological nuances provide an ideal backdrop for examining the adoption of SAPs. The study location shown in is approximately 27.36° N latitude and 88.39° E longitude, capturing the central coordinates of the state (Meek & Anderson, Citation2019).

5.2. Sampling methods

Step 2: Three-stage sampling process

Utilizing a meticulous three-stage approach, the first stage involved the purposeful selection of districts within Sikkim to encompass regional diversity. In the second stage, villages were randomly chosen within the selected districts. In the third stage, farming households were selected using a simple random sampling technique comprising a sample size of 407 farmers. This method ensures representation across various geographical and socio-cultural contexts.

5.3. Data collection methods

Step 3: Farmer selection criteria

Farmers within the chosen villages constitute the study participants. To capture a broad spectrum of perspectives, selection criteria encompass age, gender, education, farming experience and annual income. This step is essential for creating a comprehensive cross-sectional view of the diverse farming community.

Step 4: Informed consent and exclusive reliance on quantitative surveys

The survey, undertaken to gain insights into the inclinations of farmers toward embracing SAPs, utilized a multistage sampling technique. The sample consisted of 407 farmers, chosen to ensure diversity across geographical locations and farm sizes. The data collection process involved personal visits to the chosen households, where the researcher conducted face-to-face interviews with the farmers using a structured questionnaire.

5.4. Survey sampling

The journey into understanding sustainable agriculture practices (SAP) adoption involved a meticulous approach to survey sampling, recognizing the need for a comprehensive and representative study (Arif et al., Citation2019).

Stage 1: Selection of districts

The first stage unfolded with a strategic selection of districts, utilizing a stratified random sampling method. Two districts were chosen based on agroecological zones, a crucial consideration given Sikkim’s diverse agricultural landscape comprising four districts in total.

Stage 2: Selection of villages

Moving forward, the study delved into the heart of Sikkim’s rural communities. Eight villages were randomly chosen from the two previously selected districts, employing a proportional allocation approach. This ensured that the chosen villages represented the diversity inherent in these districts, laying the groundwork for a nuanced exploration.

Stage 3: Selection of farmers

With districts and villages identified, the next stage focused on the heart of the study – the farmers. A simple random sampling method was employed within each selected village to choose 407 households with smallholder farmers. A list of households, meticulously obtained from local administrative authorities, formed the basis for this selection. To ensure an unbiased and representative sample, a random starting point within each village was determined, guaranteeing that every smallholder farmer had an equal chance of being part of the study.

In essence, our survey sampling strategy was a thoughtful and systematic process, ensuring that the selected districts, villages and farmers collectively contributed to a rich and diverse tapestry of insights into SAP adoption in the regional context of Sikkim, India.

5.5. Questionnaire development

In the meticulous process of developing the questionnaire, we embarked on a journey of precision and relevance, ensuring that every item resonates with the intricacies of SAPs adoption.

A comprehensive pool of items emerged, meticulously crafted to measure each component of the TPB. Leveraging established scales from the scholarly works of Nguyen et al. (Citation2021) and Tama et al. (Citation2021), we adapted these measures to the unique context of SAP adoption in our study area. The process was not only grounded in academic rigor but was also enriched by expert reviews and pilot testing, ensuring that the content was not only valid but also deeply relevant to the nuances of our research context.

The Likert scale was used, through which respondents expressed their sentiments. Spanning a 5-point spectrum, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), this scale provided the participants with the means to articulate their agreement or disagreement with the statements provided. This nuanced approach allowed us to capture the subtleties of their perspectives, enriching our understanding of the intricate psychological factors underpinning SAP adoption INs.

In this narrative of questionnaire development, each element is meticulously crafted, ensuring that the instrument becomes a reliable and insightful guide in unraveling the complexities of farmers’ perspectives on embracing SAPs.

5.6. Data analysis methods

Embarking on the phase of data analysis, this research strategically employs PLS-SEM as its analytical framework. This sophisticated approach serves as a powerful lens through which the intricate interplay of psychological factors and socio-demographic influences within the realm of sustainable agriculture comes into focus.

The path model:

At the heart of our analytical endeavor lies the path model, a foundational construct delineating the relationships among key components – AT, PBC, social norms (SN) and IN. This model becomes the intricate map guiding us through the psychological landscape of sustainable agriculture adoption.

Ensuring reliability and validity:

To fortify the robustness of our findings, we meticulously assess construct reliability and validity. Cronbach’s alpha, Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT), and the Fornell–Larcker criterion emerge as our compass, ensuring that our measurements are both internally consistent and externally valid.

Bootstrapping for rigorous evaluation:

The journey of scrutiny extends to the implementation of bootstrapping techniques. This method becomes our magnifying glass, allowing for a meticulous examination of our model’s direct and mediation effects. Through this lens, we scrutinize the hypothesized relationships, ensuring the integrity and depth of our analytical insights.

Unveiling moderation effects:

Delving deeper, we explore moderation effects using interaction terms, unraveling the impact of these moderating factors across different subgroups. This granular analysis allows us to dissect the complexities of our data, understanding how various factors shape and influence the dynamics of sustainable agriculture adoption.

As we navigate this analytical journey, every step is infused with a commitment to precision, integrity and a comprehensive understanding of the intricate factors guiding farmers’ INs toward SAPs.

5.7. Ethical considerations

From inception to completion, ethical considerations served as the guiding compass, ensuring the integrity, transparency and welfare of all participants in this study.

Informed consent:

Prior to embarking on data collection, a foundational step was securing informed consent from every participating farmer. This process involved providing clear and comprehensive information about the study’s purpose, the voluntary nature of participation, and the absolute confidentiality of responses. Participants were empowered with knowledge, enabling them to make informed decisions about their involvement.

Confidentiality safeguards:

The collected data, regarded as a trust bestowed by participants, was treated with the utmost confidentiality. Personal identifiers were rigorously anonymized to shield the privacy of each participant. This commitment to confidentiality not only complied with ethical standards but also fostered an environment of trust, encouraging open and honest contributions from participants.

Respect for participants’ rights and well-being:

Central to the ethical framework was the unwavering commitment to prioritizing the rights and well-being of every participant. Throughout the study, the research team remained vigilant and responsive to any concerns raised by participants. A respectful and supportive research environment was cultivated, ensuring that participants felt valued, heard, and respected throughout their engagement in the study.

Adherence to ethical principles:

The study’s ethical compass extended beyond procedural considerations to a broader commitment to established ethical principles in social research. Every facet of the research, from conceptualization to dissemination, adhered to principles of integrity, transparency and a steadfast dedication to the welfare of participants. This ethical grounding not only fortified the study’s credibility but also underscored the moral responsibility inherent in social research.

6. Results

6.1. Demographic profile of participant farmers

delves into the demographic profile of participant farmers, offering insights into contextual factors that may influence SAPs. Most participants are male (69.3%), and the age distribution is diverse, with 45.7% falling between 34 and 49 years. The education levels, farming size and experience further depict the heterogeneous nature of the participant pool, providing a foundation for understanding the subsequent analyses.

Table 1. Showing demographic profile of participant farmers.

6.2. Descriptive statistics of key variables

provides a comprehensive overview of the descriptive statistics for key variables in our study. Examining the mean scores, social norms (SN) present a moderate score of 2.97, suggesting a balanced perception within the sample. PBC reflects a moderate level at 2.72, highlighting individual variability in perceived control. AT and IN scores indicate relatively positive ATs (M = 3.35) and moderate INs (M = 3.32), aligning with established psychological theories.

Table 2. Showing descriptive statistics of key variables.

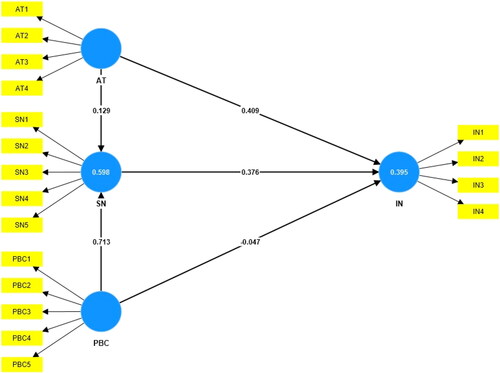

6.3. Path model

To visually represent the intricate relationships between key variables explored in our study, we employ a path model shown in . This graphical representation, a path diagram, is a valuable tool for elucidating the direct and indirect effects among the variables under consideration. The path model visually encapsulates the structural relationships embedded in our empirical findings.

6.4. Construct reliability and validity in PLS-SEM analysis

The study adhered to established criteria and guidelines to assess construct reliability and validity in the PLS-SEM analysis.

Construct reliability, measured by Cronbach’s alpha, demonstrated acceptable levels across the constructs: 0.659 for AT, 0.622 for IN, 0.927 for PBC and 0.775 for social norms (SN). These values align with the recommended thresholds, indicating satisfactory internal consistency within each construct (Chin, Citation1998; Hair et al., Citation2017; Hair et al., Citation2020; Henseler et al., Citation2015).

Discriminant validity, a critical aspect of construct validation, was evaluated using the (HTMT) (Henseler et al., Citation2015). The HTMT values, in matrix and list form, were well below the recommended threshold of 0.85 (Henseler et al., Citation2015), confirming discriminant validity. This aligns with prior research emphasizing the importance of discriminant validity in structural equation modeling (Hair et al., Citation2017).

The Fornell–Larcker criterion further supported discriminant validity by comparing the average variance extracted (AVE) square root with the correlations (Henseler et al., Citation2015). The AVE square roots for each construct (AT: 0.704, IN: 0.542, PBC: 0.398, SN: 0.415) exceeded the correlations between the constructs, providing evidence for the distinctiveness of each construct (Hair et al., Citation2020; Henseler et al., Citation2015).

Cross-loadings were examined, indicating the extent to which an item loads on its intended construct versus other constructs. All items are predominantly loaded on their respective constructs, with minimal cross-loadings, affirming the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement model (Chin, Citation1998).

Collinearity statistics were measured by the variance inflation factor (VIF) to detect multicollinearity. VIF values for the indicators of each construct were well below the conventional threshold of 5, indicating the absence of severe multicollinearity (Hair et al., Citation2017).

In summary, the PLS-SEM results demonstrate robust construct reliability and validity, aligning with established guidelines and contributing to the study’s methodological rigor.

6.5. Goodness-of-fit and explanatory power

The SRMR, a measure of the average absolute covariance residual, yielded identical values of 0.063 for both the saturated and estimated models, indicating an excellent fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

Additionally, the R2 values for the endogenous variables, IN and social norms (SN), were examined. The R2 value for IN was 0.398, suggesting that the model accounts for 39.8% of the variance in IN. The R2 value provides insights into the model’s explanatory power for the respective endogenous variables (Hair et al., Citation2017).

In summary, the goodness-of-fit indices and R2 values collectively indicate that the estimated model adequately represents the data, with a satisfactory fit and substantial explanatory power for the endogenous variables.

6.6. Direct hypotheses testing results

presents the outcomes of direct hypothesis testing. Accepted hypotheses (H1, H2, H4 and H5) emphasize the impactful roles of AT, PBC and SN in shaping IN. The rejected hypothesis (H3) prompts a nuanced understanding of the relationship between PBC and IN, suggesting potential moderating or mediating factors.

Table 3. Summary of direct hypothesis testing results.

6.7. Mediation hypotheses testing results

Mediation pathways are explored in . Accepted hypotheses (H6 and H7) underscore the mediating influence of SN in the relationships between AT and IN and between PBC and IN, respectively. These findings highlight the complex interplay of psychological constructs in influencing behavioral INs.

Table 4. Summary of mediation hypothesis testing results.

6.8. Moderation testing results

unravels the nuanced influence of socio-demographic factors. Noteworthy findings include the moderating impact of Education and Age on the relationships between AT and IN and SN and IN, respectively. Farming Experience also reveals a significant moderating effect on the SN and IN relationship.

Table 5. Summary of moderation testing results.

6.9. The multi-group analysis results

Multi-group analysis shows distinctive patterns and significances within different socio-demographic categories in , underscoring the need for tailored approaches in promoting SAPs.

Table 6. Showing multi-group analysis in SEM.

Gender dynamics:

Male farmers: The analysis uncovered a statistically significant association between positive ATs and INs to adopt sustainable practices among male farmers (p < 0.05). This indicates that personal beliefs strongly influence male participants’ inclination toward sustainable agriculture.

Female farmers: In contrast, ATs alone did not significantly predict INs among female farmers. The study suggests that, for female farmers, social norms play a more pivotal role in shaping INs toward sustainable agriculture.

Age as a determinant:

Younger participants (18–33): ATs alone were insufficient to predict INs among younger participants, suggesting the potential influence of external factors like peer networks and technological interventions.

Older participants (34–49 and 50+): Positive ATs significantly correlated with INs for older participants, emphasizing the role of traditional values and experiences in driving sustainable agriculture adoption.

Socioeconomic factors and behavioral control:

Household size: Farmers with larger household sizes showed a stronger link between positive ATs and INs, indicating the influence of collective decision-making within families.

Education: While SN played a significant role for those with primary education, individuals with a high school education and above exhibited a stronger link between positive ATs and INs.

Farm size and experience as determinants:

Farm size: Small-scale farmers exhibited a stronger association between positive ATs and INs, emphasizing the need for targeted support for this demographic.

Farming experience: Varied motivations were observed between novice and seasoned farmers, prompting the need for differentiated educational approaches.

Farming annual income:

Income below 200,000 Rupees: A significant link was observed between positive ATs and INs for farmers with an income below 200,000 Rupees, emphasizing the need for support tailored to this income bracket.

These outcomes underscore the importance of recognizing diverse psychological and social factors influencing different demographic groups. A uniform strategy for promoting sustainable agriculture may not be effective. Instead, interventions should be nuanced, considering various groups’ unique characteristics and influences. This study emphasizes the value of multi-group analysis in uncovering these subtleties. It guides the formulation of targeted strategies for a more effective promotion of SAPs.

7. Discussion

7.1. Navigating complexities in sustainable agricultural practices adoption

Our study presents a comprehensive exploration of the factors influencing the adoption of SAPs, employing a synthesis of the TPB and social norms theory. The findings offer nuanced insights into the interplay of psychological constructs, socio-demographic factors and farmers’ INs. This discussion contextualizes our results within the broader landscape of existing literature, highlighting both alignments and departures.

Our research aligns intricately with existing literature on SAP adoption, acknowledging and building upon the foundation laid by prior studies. However, our departure from traditional economic-centric paradigms signals a paradigm shift. Economic incentives have conventionally dominated the discourse, with financial gains considered the primary driver of SAP adoption (Lastiri-Hernández et al., Citation2020; Mutyasira et al., Citation2018; Syan et al., Citation2019; Waseem et al., Citation2020). Our study challenges this narrow viewpoint, recognizing the limitations of exclusively economic models in capturing the multifaceted nature of adoption decisions (Montes de Oca Munguia et al., Citation2021; Syan et al., Citation2019). The infusion of behavioral variables – ATs, social norms and PBC – introduces layers of complexity that extend beyond economic rationality (Serebrennikov et al., Citation2020).

Integrating behavioral economics into our study enriches our understanding, acknowledging that financial gains do not solely drive farmers’ decisions. This broader perspective empowers us to explore the intricate interplay between cognitive processes, social influences and individual motivations (Dessart et al., Citation2019; Menozzi et al., Citation2015). Our study, thus, addresses critical gaps in the existing literature by bringing attention to intrinsic factors that significantly shape adoption decisions (Prokopy et al., Citation2019).

While past literature has recognized the influence of sociological factors, such as social norms, ATs and PBC, our study elevates these elements from the periphery to the forefront (Atta‐Aidoo et al., Citation2022; Zhou et al., Citation2023). Rather than relegating them to the shadows within economic-centric models, our research places a spotlight on these crucial factors, underscoring their pivotal role in shaping community-level dynamics related to the adoption of sustainable practices (Tega & Bojago, Citation2023; Tschopp et al., Citation2020). In doing so, we build upon existing acknowledgments of these sociological factors and provide a more nuanced and emphasized understanding of their significance in the complex landscape of sustainable agriculture adoption.

By addressing these sociological factors, our study contributes to understanding community-level dynamics, shedding light on the influence of social interactions and community expectations. Considering the broader socio-cultural context, this holistic perspective is crucial for designing interventions beyond individual motivations (Bathaei & Streimikiene, Citation2023; Janker et al., Citation2019).

Our empirical analysis unveils intricate mediation and moderation dynamics within the TPB framework. Social norms act as influential mediators, bridging the gap between individual ATs and INs (Delaroche, Citation2020; Fielding et al., Citation2008). This underscores the communal context as a decisive factor in shaping behavioral INs. Additionally, moderation analyses reveal interactions between demographic factors and TPB constructs, emphasizing the need for tailored interventions based on contextual nuances (Bagheri et al., Citation2019; Sok et al., Citation2021).

The multi-group analysis findings further enrich our understanding by highlighting distinctive patterns and significances within different socio-demographic categories. This underscores the importance of recognizing diverse psychological and social factors influencing different demographic groups. A uniform strategy for promoting sustainable agriculture may not be effective. Instead, interventions should be nuanced, considering various groups’ unique characteristics and influences. This study emphasizes the value of multi-group analysis in uncovering these subtleties. It guides the formulation of targeted strategies for more effective promotion of SAPs (Boufous et al., Citation2023).

These findings extend the existing literature by unraveling the complexity within TPB relationships. While TPB has been widely applied, our study emphasizes the necessity of considering contextual variations and highlights the role of social norms as crucial mediators in the adoption process (Delaroche, Citation2020; Fielding et al., Citation2008).

Our study’s departure from economic-centric approaches aligns with a broader trend in the literature that recognizes the limitations of exclusively economic models in comprehending the diverse and context-specific nature of SAP adoption (Ehiakpor et al., Citation2021; Setsoafia et al., Citation2022). Integrating behavioral economics and sociological perspectives broadens our understanding by acknowledging the intricate nature of farmers’ decisions (Menozzi et al., Citation2015). This departure represents a significant contribution to the field, addressing past limitations and paving the way for a more comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach (Velten et al., Citation2015).

7.2. Practical implications

The practical implications of our findings are profound. Recognizing the limitations of economic-centric models, our study advocates for interventions that acknowledge the intricate interplay of motivations, community dynamics and contextual variations (Dessart et al., Citation2019). The nuanced insights gained from our investigation provide a roadmap for policymakers, extension services, and development practitioners to craft interventions that align with the diverse motivations of farmers across different segments (Roesch‐McNally et al., Citation2017).

Given the significant influence of social norms on farmers’ INs, interventions should prioritize community engagement strategies. Building supportive social environments through community-based initiatives and knowledge-sharing platforms can amplify the positive impact of individual ATs toward SAP adoption. The study highlights the importance of targeted educational programs that address the diverse demographic characteristics influencing SAP adoption. Tailored interventions considering age, education and gender can effectively address the specific needs and challenges faced by different segments of the farming community (Lastiri-Hernández et al., Citation2020; Mutyasira et al., Citation2018).

As we look to the future, integrating behavioral economics and sociological perspectives promises a more holistic understanding of SAP adoption (Puntsagdorj et al., Citation2021). Our study lays the foundation for a comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach, bridging the disciplines of economics, psychology and sociology (Jeerat et al., Citation2022). This integration offers a potent framework for unraveling the complexities inherent in farmers’ decision-making processes (Garforth et al., Citation2003).

7.3. Linking implications with sustainable development goals (SDGs)

Our study’s findings bear significance not only in the realm of theoretical understanding but also in their practical implications for addressing global challenges. Aligning with the broader agenda of sustainable development goals (SDGs), the implications drawn from our research offer actionable insights that contribute to the pursuit of a sustainable and equitable future. Below, we delineate the connections between our study’s practical implications and key SDGs, highlighting the transformative potential of adopting SAPs.

SDG 2: Zero Hunger Promoting the adoption of SAPs directly contributes to SDG 2 by enhancing agricultural sustainability, improving crop yields, and ensuring food security. Sustainable practices foster resilience in agricultural systems, mitigating the impact of climate change and promoting long-term food production (Foguesatto et al., Citation2020). By aligning interventions with SDG 2, our study supports global efforts to eradicate hunger and achieve food security.

SDG 4: Quality Education The recommended tailored educational programs align with SDG 4, emphasizing inclusive and equitable quality education. Empowering farmers with knowledge and skills related to SAP adoption enhances their capacity to make informed decisions, fostering SAPs (Myeni et al., Citation2019). By supporting SDG 4, our study contributes to advancing education as a catalyst for sustainable development, ensuring that agricultural communities are equipped with the necessary knowledge for informed and sustainable decision-making.

SDG 5: Gender equality the study’s consideration of demographic factors, including gender, aligns with SDG 5 by addressing gender equality concerns. Analyzing how demographic factors moderate the relationship between ATs, social norms and PBC provides insights into gender-specific dynamics in SAP adoption. By promoting gender equality, our study contributes to fostering inclusivity and equity in sustainable agricultural development (Setsoafia et al., Citation2022).

SDG 12: Responsible consumption and production adopting SAPs aligns with SDG 12 by promoting responsible consumption and production. By encouraging sustainable and efficient use of resources in agriculture, our study contributes to the broader goal of ensuring sustainable production patterns. This supports efforts to minimize the environmental impact of agricultural activities and promote adopting sustainable production practices (Adenle et al., Citation2018; Piñeiro et al., Citation2020).

SDG 13: Climate action the study’s emphasis on SAPs aligns closely with SDG 13 by addressing climate-related challenges. SAP adoption contributes significantly to climate resilience, efficient resource utilization and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, fostering sustainable agricultural systems (Makate et al., Citation2017). Our findings contribute to the global agenda for environmental sustainability and climate resilience by promoting climate action.

SDG 15: Life on land SAPs contribute to SDG 15 by promoting life on land. The study’s focus on environmentally friendly practices, including soil health and reduced environmental impact, aligns with goals to protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems. By endorsing practices that preserve biodiversity and enhance ecosystem services, our findings support global initiatives for land sustainability (Krauss, Citation2021).

7.4. Limitations and future directions

Our investigation into the determinants of SAPs adoption in Sikkim, India, has yielded valuable insights. However, we acknowledge several limitations that influence the applicability and generalizability of our findings.

A principal constraint of our study is its exclusive focus on Sikkim, India. Sikkim’s distinctive socio-cultural and environmental context may introduce variances in SAP adoption dynamics, limiting the extrapolation of our results to other regions or nations. Subsequent research endeavors should contemplate cross-cultural inquiries to unravel divergences in social norms and individual INs pertinent to SAP adoption across diverse geographical settings.

Broadening the scope of our inquiry to encompass cross-cultural dimensions holds promise for a more comprehensive understanding of how social norms and individual INs manifest in distinct cultural contexts. Comparative studies have the potential to elucidate the variations in these factors across regions, taking into account diverse agricultural landscapes, community structures and cultural nuances (Bhujel & Joshi, Citation2023).

Our study offers a snapshot of ATs and social norms at a specific moment in time. In future research, introducing a temporal dimension through longitudinal studies would facilitate tracking changes in ATs, social norms, and adoption INs over time. This temporal perspective is essential for comprehending the evolution of these factors and their implications for sustained SAP adoption.

While our study examines demographic factors and their moderating effects, future research could delve deeper into the intersectionality of socioeconomic and demographic variables. A more nuanced exploration of how factors such as income levels, educational backgrounds and landholding sizes intersect with ATs and social norms would enhance the granularity of our understanding.

Our reliance on the TPB and sociopsychological dynamics constitutes a primary focus. Future research could adopt a more multi-dimensional approach by integrating additional theoretical frameworks. Incorporating sociological theories, for instance, could provide a richer contextualization of the social dynamics influencing SAP adoption.

An avenue for future research lies in investigating the practical applicability of our insights. Exploring how the nuanced findings from our study can be translated into effective policy interventions and on-the-ground practices would bridge the gap between research and action, fostering the actualization of sustainable agricultural initiatives (Sengupta et al., Citation2022).

Future research endeavors could embrace interdisciplinary collaboration to comprehensively address the complexities of SAP adoption. Integrating insights from behavioral economics, sociology and agronomy could offer a more holistic understanding, enriching the discourse on sustainable agriculture.

While our study significantly contributes to the local context of Sikkim, future research could explore the global relevance of SAP adoption. Comparative analyses across regions with diverse agricultural systems and challenges would further enhance the broader implications of our findings.

In conclusion, our study provides a robust foundation for understanding SAP adoption in Sikkim. The highlighted limitations underscore directions for future research, expanding scholarly discourse and offering actionable insights for stakeholders engaged in promoting SAPs on a global scale. Our commitment to advancing knowledge encourages ongoing exploration and collaboration for a sustainable agricultural future.

8. Conclusion

In the conclusion of this research journey, our exploration into adopting SAPs has intricately woven together theoretical underpinnings, empirical revelations and sociological insights. This study examines the myriad factors influencing farmers’ decisions, unveiling the multifaceted nature of SAP adoption that transcends simplistic economic models. The complex interplay of individual motivations, societal expectations and the broader agricultural landscape unfolds through a sociopsychological lens.

Firmly grounded in the TPB and adorned with sociological perspectives, charting our exploratory course has been instrumental. Integrating the sociopsychological construct social norms (SN) expands the traditional boundaries of behavioral theories, navigating the complexities of SAP adoption and recognizing the deep embedding of personal ATs in the social fabric.

Empirical findings underscore the diverse sociopsychological dynamics influencing SAP adoption, revealing intricate relationships between AT and IN, PBC and IN, and the mediating role of social norms. Social norms emerge as pivotal determinants, acting as direct influencers and mediators in the adoption decision-making process. This study’s unique contribution seamlessly integrates sociological insights with established behavioral frameworks, transcending limitations and enhancing its sociological significance.

Beyond academic discourse, our study offers actionable insights for policymakers, local governments, researchers and stakeholders. Recommendations advocate for longitudinal studies, cross-cultural investigations and in-depth analyses of social capital’s role, shaping the future research landscape and becoming a catalyst for sustained advancements in sustainable agriculture.

The study’s findings suggest the need for tailored sustainability interventions, recognizing the diverse motivations and contextual factors influencing smallholder farmers’ decisions. Policymakers, local governments, and NGOs can leverage these insights to design interventions that align with the sociocultural fabric influencing agricultural practices.

While this research provides valuable insights, it is not without limitations. Future studies should consider addressing these limitations and further explore the dynamics of social capital in SAP adoption. Additionally, longitudinal studies and cross-cultural investigations can offer a more comprehensive understanding of the evolving landscape of sustainable agriculture.

The journey toward sustainable agriculture is recognized as a collective effort as we navigate the path forward. Each farmer, influenced by ATs, norms and perceptions, is a unique contributor to the harmonious transition. Our study’s sociopsychological orientation amplifies individuals’ voices within the collective narrative of agricultural transformation.

Ethical approval

KH Manipal (MAHE), with approval number IEC-2021-494, provided ethical clearance for the whole PhD of which this project is a part. Informed consent was collected from participants.

Author contributions

R.R. Bhujel (RB) and H.G. Joshi (HJ) conceptualized and designed the study. RB gathered the data and conducted the statistical analysis. RB drafted the initial manuscript. HJ supervised the study, offered significant input and substantially reviewed and refined the manuscript. All authors have endorsed the final manuscript for submission.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt appreciation to our research colleagues for their invaluable insights and to the farmers whose active engagement in this study was indispensable. We also express our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers whose constructive feedback significantly contributed to the refinement of this research.

Disclosure statement

The authors state that they have no competing interests to disclose.

Data availability statement

The dataset associated with this study is available at the following DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.24003591.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Roshan Raj Bhujel

Roshan Raj Bhujel and Harisha G. Joshi are dedicated researchers in sustainable agriculture, bringing a wealth of expertise and commitment to their exploration. Their academic pursuits extend beyond conventional boundaries, driven by a shared passion for unraveling the intricate dynamics of societal and environmental systems. With a foundation built on rigorous research acumen and a commitment to positive change, the authors bring diverse perspectives to the forefront. Their collaborative efforts transcend traditional academic boundaries, drawing from a rich tapestry of experiences to delve into the complexities of sustainable practices. As engaged scholars deeply committed to exploration, their journey goes beyond theoretical frameworks. Motivated to understand and illuminate the factors shaping sustainable agricultural practices, they embark on a collective journey that ventures into the heart of communities, seeking insights that resonate with diverse stakeholders in the agricultural landscape. Beyond the confines of this study, their commitment extends to the broader tapestry of societal and environmental well-being.

H.G. Joshi

Roshan Raj Bhujel and Harisha G. Joshi are dedicated researchers in sustainable agriculture, bringing a wealth of expertise and commitment to their exploration. Their academic pursuits extend beyond conventional boundaries, driven by a shared passion for unraveling the intricate dynamics of societal and environmental systems. With a foundation built on rigorous research acumen and a commitment to positive change, the authors bring diverse perspectives to the forefront. Their collaborative efforts transcend traditional academic boundaries, drawing from a rich tapestry of experiences to delve into the complexities of sustainable practices. As engaged scholars deeply committed to exploration, their journey goes beyond theoretical frameworks. Motivated to understand and illuminate the factors shaping sustainable agricultural practices, they embark on a collective journey that ventures into the heart of communities, seeking insights that resonate with diverse stakeholders in the agricultural landscape. Beyond the confines of this study, their commitment extends to the broader tapestry of societal and environmental well-being.

References

- Adenle, A. A., Azadi, H., & Manning, L. (2018). The era of sustainable agricultural development in Africa: Understanding the benefits and constraints. Food Reviews International, 34(5), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2017.1300913

- Ahnström, J., Höckert, J., Bergeå, H. L., Francis, C. A., Skelton, P., & Hallgren, L. (2009). Farmers and nature conservation: What is known about attitudes, context factors and actions affecting conservation? Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 24(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170508002391

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195

- Anibaldi, R., Rundle-Thiele, S., David, P., & Roemer, C. (2021). Theoretical underpinnings in research investigating barriers for implementing environmentally sustainable farming practices: Insights from a systematic literature review. Land, 10(4), 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10040386

- Anuar, S. N. A., Mokhtar, N. F., & Set, K. (2019). Teachers behavior toward digital education. Journal of Information System and Technology Management, 4(13), 32–47. https://doi.org/10.35631/10.35631/JISTM.413004

- Arif, M., Rao, D. S., & Gupta, K. (2019). Peri-urban livelihood dynamics: A case study from Eastern India. Forum Geografic, XVIII(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.5775/fg.2019.012.i

- Atta-Aidoo, J., Antwi-Agyei, P., Dougill, A. J., Ogbanje, C. E., Akoto-Danso, E. K., & Eze, S. (2022). Adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices by smallholder farmers in rural Ghana: An application of the theory of planned behavior. PLoS Climate, 1(10), e0000082. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000082

- Bagheri, A., Bondori, A., Allahyari, M. S., & Damalas, C. A. (2019). Modeling farmers’ intention to use pesticides: An expanded version of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Environmental Management, 248, 109291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109291

- Bathaei, A., & Štreimikienė, D. (2023). A systematic review of agricultural sustainability indicators. Agriculture, 13(2), 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13020241

- Bhujel, R. R., & Joshi, H. G. (2023). Understanding farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture in Sikkim: The role of environmental consciousness and attitude. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1), 2261212. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2261212

- Bopp, C., Engler, A., Poortvliet, P. M., & Jara-Rojas, R. (2019). The role of farmers’ intrinsic motivation in the effectiveness of policy incentives to promote sustainable agricultural practices. Journal of Environmental Management, 244, 320–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.04.107

- Borges, J. A. R., Domingues, C. H. F., Caldara, F. R., Rosa, N. P. D., Senger, I., & Guidolin, D. G. F. (2019). Identifying the factors impacting on farmers’ intention to adopt animal friendly practices. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 170, 104718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2019.104718

- Boufous, S., Hudson, D., & Carpio, C. E. (2023). Farmers’ willingness to adopt sustainable agricultural practices: A meta-analysis. PLoS Sustainability and Transformation, 2(1), e0000037. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pstr.0000037

- Cakirli Akyüz, N. C., & Theuvsen, L. (2020). The impact of behavioral drivers on adoption of sustainable agricultural practices: The case of organic farming in Turkey. Sustainability, 12(17), 6875. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176875

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Daxini, A., O’Donoghue, C., Ryan, M., Buckley, C., Barnes, A. P., & Daly, K. (2018). Which factors influence farmers’ intentions to adopt nutrient management planning? Journal of Environmental Management, 224, 350–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.07.059

- Delaroche, M. (2020). Adoption of conservation practices: What have we learned from two decades of social-psychological approaches? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 45, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.08.004

- Dessart, F. J., Barreiro-Hurlé, J., & van Bavel, R. (2019). Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: A policy-oriented review. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 46(3), 417–471. https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbz019

- Ehiakpor, D. S., Danso-Abbeam, G., & Mubashiru, Y. (2021). Adoption of interrelated sustainable agricultural practices among smallholder farmers in Ghana. Land Use Policy, 101, 105142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105142

- Elahi, E., Zhang, H., Lirong, X., Khalid, Z., & Xu, H. (2021). Understanding cognitive and socio-psychological factors determining farmers’ intentions to use improved grassland: Implications of land use policy for sustainable pasture production. Land Use Policy, 102, 105250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105250

- Fielding, K. S., Terry, D. J., Masser, B. M., & Hogg, M. A. (2008). Integrating social identity theory and the theory of planned behaviour to explain decisions to engage in sustainable agricultural practices. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 47(Pt 1), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466607X206792

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research (p. 27). Addison-Wesley, Co.

- Foguesatto, C. R., Borges, J. A. R., & Machado, J. A. D. (2020). A review and some reflections on farmers’ adoption of sustainable agricultural practices worldwide. The Science of the Total Environment, 729, 138831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138831

- Garforth, C., Angell, B., Archer, J., & Green, K. (2003). Fragmentation or creative diversity? Options in the provision of land management advisory services. Land Use Policy, 20(4), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(03)00035-8

- Ghimire, R., Wen-Chi, H. U. A. N. G., & Shrestha, R. B. (2015). Factors affecting adoption of improved rice varieties among rural farm households in Central Nepal. Rice Science, 22(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsci.2015.05.006

- Govindharaj, G., Gowda, B., Sendhil, R., Adak, T., Raghu, S., Patil, N., Mahendiran, A., Rath, P. C., Kumar, G. A. K., & Damalas, C. A. (2021). Determinants of rice farmers’ intention to use pesticides in eastern India: Application of an extended version of the planned behavior theory. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 26, 814–823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.12.036

- Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109(1), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Janker, J., Mann, S., & Rist, S. (2019). Social sustainability in agriculture – A system-based framework. Journal of Rural Studies, 65, 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.12.010

- Jeerat, P., Kruekum, P., Sakkatat, P., Rungkawat, N., & Fongmul, S. (2022). Developing a model for building farmers’ beliefs in the sufficiency economy philosophy to accommodate sustainable agricultural practices in the highlands of Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. Sustainability, 15(1), 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010511

- Knowler, D., & Bradshaw, B. (2007). Farmers’ adoption of conservation agriculture: A review and synthesis of recent research. Food Policy. 32(1), 25–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2006.01.003

- Krauss, J. E. (2021). Decolonizing, conviviality and convivial conservation: Towards a convivial SDG 15, life on land? Journal of Political Ecology, 28(1), 945–967. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.3008

- Lalani, B., Dorward, P., Holloway, G., & Wauters, E. (2016). Smallholder farmers’ motivations for using Conservation Agriculture and the roles of yield, labour and soil fertility in decision making. Agricultural Systems, 146, 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2016.04.002

- Lastiri-Hernández, M. A., Álvarez-Bernal, D., Moncayo‐Estrada, R., Cruz-Cárdenas, G., & García, J. T. (2020). Adoption of phytodesalination as a sustainable agricultural practice for improving the productivity of saline soils. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(6), 8798–8814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00995-5

- Liu, T., Bruins, R. J. F., & Heberling, M. T. (2018). Factors influencing farmers’ adoption of best management practices: A review and synthesis. Sustainability, 10(2), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020432

- Long, T. B., Blok, V., & Coninx, I. (2016). Barriers to the adoption and diffusion of technological innovations for climate-smart agriculture in Europe: Evidence from the Netherlands, France, Switzerland and Italy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.06.044

- Makate, C., Makate, M., & Mango, N. (2017). Smallholder farmers’ perceptions on climate change and the use of sustainable agricultural practices in the Chinyanja Triangle, Southern Africa. Social Sciences, 6(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6010030

- Manda, J., Alene, A. D., Gardebroek, C., Kassie, M., & Tembo, G. (2016). Adoption and impacts of sustainable agricultural practices on maize yields and incomes: Evidence from rural Zambia. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 67(1), 130–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12127

- Meek, D., & Anderson, C. (2019). Scale and the politics of the organic transition in Sikkim, India. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 44(5), 653–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2019.1701171

- Menozzi, D., Fioravanzi, M., & Donati, M. (2015). Farmer’s motivation to adopt sustainable agricultural practices. Bio-based and Applied Economics Journal, 4(2), 125–147. https://doi.org/10.13128/bae-14776

- Mishra, B., Gyawali, B. R., Paudel, K. P., Poudyal, N. C., Simon, M. F., Dasgupta, S., & Antonious, G. (2018). Adoption of sustainable agriculture practices among farmers in Kentucky, USA. Environmental Management, 62(6), 1060–1072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-018-1109-3

- Montes de Oca Munguia, O. M., Pannell, D. J., Llewellyn, R., & Stahlmann-Brown, P. (2021). Adoption pathway analysis: Representing the dynamics and diversity of adoption for agricultural practices. Agricultural Systems, 191, 103173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103173

- Mutyasira, V., Hoag, D., & Pendell, D. (2018). The adoption of sustainable agricultural practices by smallholder farmers in Ethiopian Highlands: An integrative approach. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 4(1), 1552439. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2018.1552439

- Myeni, L., Moeletsi, M., Thavhana, M., Randela, M., & Mokoena, L. (2019). Barriers affecting sustainable agricultural productivity of smallholder farmers in the Eastern Free State of South Africa. Sustainability, 11(11), 3003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113003

- Neill, S. P., & Lee, D. R. (2001). Explaining the adoption and disadoption of sustainable agriculture: The case of cover crops in northern Honduras. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 49(4), 793–820. https://doi.org/10.1086/452525

- Nguyen, T. P. L., Doan, X. H., Nguyen, T. T., & Nguyen, T. M. A. (2021). Factors affecting Vietnamese farmers’ intention toward organic agricultural production. International Journal of Social Economics, 48(8), 1213–1228. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-08-2020-0554

- Pham, H. G., Chuah, S. H., & Feeny, S. (2021). Factors affecting the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices: Findings from panel data for Vietnam. Ecological Economics, 184, 107000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107000

- Piñeiro, V., Arias, J., Dürr, J., Elverdin, P., Ibáñez, A. M., Kinengyere, A., Opazo, C. M., Owoo, N., Page, J. R., Prager, S. D., & Torero, M. (2020). A scoping review on incentives for adoption of sustainable agricultural practices and their outcomes. Nature Sustainability, 3(10), 809–820. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00617-y