Abstract

This article investigates the Sebat Bête Gurage’s perceptions and engagement experiences with their cultural landscapes. Using phenomenology and landscape multifunctionality approaches, it examines the relationships between social groups and everyday landscapes as sites of dwelling, well-being, and interaction. The study utilised ethnographic in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and observations. The data was analysed qualitatively by generating themes and meanings from various data sources. Social groups such as children, youth, elderly, women, men, the disadvantaged, crafts, non-local residents and local government agents perceive and engage with landscapes based on their socio-economic and well-being associations. Non-Gurage local residents have positive perceptions and well-being associations, despite their socio-cultural backgrounds. Local government actors viewed village landscapes as public reserves for infrastructure and service expansions, despite the costs of prior landscape identities and provisions. Shared perceptions and engagement experiences exist in public landscapes, regardless of the socio-economic differences of social groups. Social groups viewed landscapes as ancestors’ gifts that stored values of man-environment interactions, memories, identities, and well-being associations. However, landscape dynamics due to intrusions, encroachments, and generation gaps regarding landscape values challenge social groups’ perceptions and landscape associations, leading to a decrease in landscape appreciation and well-being associations and a shift in perceptions. Henceforth, decision-making and interventions in village landscapes necessitate consultation of diverse interests, social demands, prior landscape provision, and long-standing landscape values as part of policy decisions in the case of micro-landscapes. An understanding of landscape dynamics among social groups is also needed to inform policy for micro-landscape decisions to balance conflicts of interests, diverse demands and ensuring landscape sustainability and multifunctionality.

IMPACT STATEMENT

This research report has the potential to look at socio-anthropological placement and multifunctionality gains of cultural landscapes in social groups’ phenomenological associations (perceptions, engagements, and experiences) and the living making of Sebat Bête Gurage in Ethiopia. Contemporary landscape research in sociology and social anthropology is more recent compared to historical engagements in cultural geography. However, socio-anthropological understanding of the landscape enables us to trace growing interests in contemporary landscape research from ethnographic, sociocultural, and humanistic viewpoints. Meanwhile, this study also helps to trace such gaps and highlights grass-roots concern for sustainable landscape governance to consider local and socially specific cultural landscape phenomenological values, associations, and multifunctionalities as everyday landscapes.

Introduction

Humans are in objective and subjective interaction with the environment. Human perceptual tools receive, organise, and interpret these encounters so that humans may learn about their surroundings, form mental representations, and behave appropriately (Khaledi et al., Citation2022). Basically, the environment, as a material world, appears to be a product of social construction, encompassing social meanings, purposes, and living conditions (Douglas et al., Citation2018). According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), the environment supports human well-being as the source of ecosystem services such as food chain, harvesting, clean water, or scenic views and as the source of cultural services such as cultural diversity, spiritual and religious values, knowledge systems, educational values, inspiration, aesthetic values, social relations, sense of place, cultural heritage values, and recreation. The symbiotic relationship between humans and landscapes promotes sustainable living, resource allocation, and essential goods and services, as well as green and social spaces and cultural expressions for individuals and collective well-being (Roe, Citation2013).

The World Heritage Committee has asserted that cultural landscapes are shaped by the continuous interaction between people and nature within indigenous societies. Cultural landscapes are the continuous adaptations made by indigenous people to the natural environment, ensuring better land use and spatial structures to meet evolving human needs (Jackson et al., Citation2020), and are essential for daily living, providing aesthetic and recreational benefits, and supplying goods and services to society (Tengberg et al., Citation2012). According to Barbara (Citation2006), understanding and engaging with landscapes requires human consciousness and active involvement. The same landscape can also hold different meanings for individuals and collectives (Howard, Citation2013).

According to Sahle and Saito (Citation2021a), Nature’s Contributions to People (NCP) highlights the role that live nature plays in enhancing people’s quality of life, identifying distinctive local viewpoints and socio-ecological contexts, and identifying multifunctional landscapes in long-term relationships. The Gurage socio-ecological landscape comprises diverse ecosystems and cultural services. The socio-ecological landscape components and their provisions are deteriorating due to socio-cultural, livelihood, and landscape changes. Consequently, landscape changes are affecting various ecosystems and socio-cultural services and potentials.

Among the Sebat Bête Gurage, landscapes have many integrating services for social groups, with a crucial role in reducing conflicting interests and addressing diverse societal demands. Landscape researchers in Gurage areas recently studied a variety of aspects of cultural landscapes, including nature’s contributions to people through the Jefore road and mapping and characterising the Gurage socio-ecological landscape (Sahle & Saito, Citation2021a, Citation2021b); the spiritual ecology of the Sebat Bête Gurage cultural landscape and aspects and dynamics of the Jefore multifunctional landscape (Shiferaw et al., Citation2023a, Citation2023b); and land use and land cover change driven by the expansion of eucalyptus plantations (Zerga et al., Citation2021). These studies provide a comprehensive understanding of the Gurage cultural landscape, including landscape aspects, provisions, and changes. However, they were not focused on the different perceptions and engagement experiences associated with village landscapes among social groups of the Gurage, non-Gurage village residents and local government agents. Moreover, previous studies did not focus on the ethnography of the Sebat Bête Gurage cultural landscapes as they relate to people’s perceptions and engagement experiences and for their broader wellbeing significance among villagers and those with specific ties to that culture.

Therefore, differently, this study explores the diverse perceptions and engagement experiences of Sebat Bête Gurage, non-Gurage residents, and local government agents around everyday village landscapes. The aim is to show how social groups (children, youth, women, men, the elderly, craftsmen, disadvantaged groups, non-local residents, and local government agents) perceive and engage in village living landscapes. The study also demonstrates the Gurage landscapes’ social and humanistic elements in addition to their ecological attributes and provisions. Phenomenological and ethnographic-based landscape understanding and the exploration of landscapes are helpful for sustaining indigenous multifunctional landscapes, their values, and human associations in the midst of landscape changes and modifications. The following research questions are designed to understand how social groups view or perceive their village landscapes and how they associate (or their engagement experiences) with village landscapes. Thus, this study explores:

How do social groups perceive and associate with village landscapes?

How do social structures affect landscape perceptions and associations?

What power relations and conflicting interests exist within village landscapes?

What observable facts exist in village landscapes as engagement landscapes?

Landscape perceptions

Cultural landscapes are defined by the European Landscape Convention (Citation2000) as places that people perceive and are shaped by both natural and human elements. They influence individuals’ thoughts, behaviours, and orientations (George, Citation2012). Landscape perception is associated with aesthetic judgement, place sense, identity, recreation, familiarity, attractiveness, livelihoods, and ecosystem services, and affordances, which are influenced by socio-cultural and biological-natural elements (Buendía et al., Citation2021; Menatti & Heft, Citation2020; Pretto, Citation2018). The phenomenology recognises the significance of socio-political and cultural elements as well as the perceiver’s embeddedness in the real world. The different socio-cultural and relational elements that affect how an individual and a group see a landscape are taken into account in the sociological and anthropological study of landscape perceptions (Menatti & Heft, Citation2020).

Perception of our surroundings influences how we interact with it, how we survive, and how much we know, claims Ingold (Citation2000). Perception of a landscape can be explicit that focusing on the observed aspects and/or the inherent view that is embedded within living practices or the subjective aspect of perception which is deeply rooted in one’s way of living and their surroundings (Johnston, Citation1998; Nakoinz & Knitter, Citation2016). Landscape perceptions are also studied from various perspectives such as demographic and livelihood characteristics as well as wellbeing aspects including examining the perceptions of various groups such as local inhabitants, experts, urban users, women, children, adults, and ethnic groups (Yang et al., Citation2021).

Landscape engagement

A sense of place refers to the quality and strength of people’s embeddedness in a place, gaining experience through use, attentiveness, and emotions towards the place (Relph, Citation1976). Landscape visual preferences and reactions in various situations can be influenced by variables including age, gender, cultural origins, psychology, and living environment (Zhang et al., Citation2022). Human well-being is also closely linked to the living landscape. However, landscapes engagement experiences are crucial for creating and acknowledging these values. The relationship between landscapes and human well-being is influenced by material environment features, socio-cultural practices and engagement experiences as well as perception of landscapes and their impact on subjective well-being also differs across social variables and biophysical contexts (Bieling et al., Citation2014).

As a product of society, landscapes are shaped by a variety of settings, observations, understandings, and interactions of different social groups, according to Ward (Citation2013), leading to a range of perceptions and experiences. Human engagement with landscapes for particular objectives, livelihoods, cultural identity, expressiveness, and memories is encouraged by landscape engagement in socio-cultural knowledge senses (Roe, Citation2013; Thompson, Citation2013).

However, due to urbanisation, food demand, agricultural abandonment, and climate change, landscapes worldwide, particularly rural ones, are changing quickly (Hedblom et al., Citation2019). The purpose of the landscape is seen differently by tourists, potential immigrants, part-time residents, and rural inhabitants, as a result of these modifications (Soini et al., Citation2012). Because of this and the fact that landscapes are changing owing to urbanisation, studies on people’s preferences for diverse landscapes have been increasingly important in recent years (Yang et al., Citation2021).

The study area

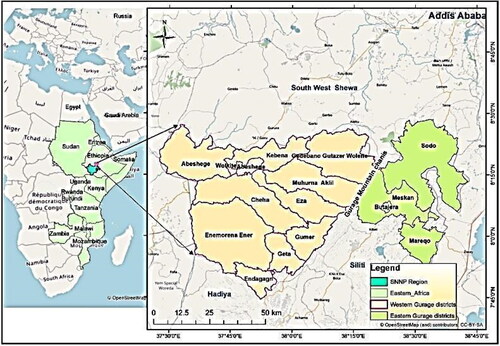

The Gurage people live in Central-South Ethiopia, in the Gurage Zone. The zone, which spans 5,932 km2, is located between 7 of 40’ and 8° 30’ North and 37° 30’ and 38° 40’ East. The zone’s varied agro-ecology makes a wide range of crops possible to cultivate. Altitudinal variations have an impact on the climate, with average temperatures varying from -3 to 28 °C. Most people reside in rural regions where they work mostly as farmers and cattle ranchers. Enset (Ensete Ventricosum), is the predominant crop and has a big influence on the Gurage’s social structures, technology, livelihood, and beliefs (Shack, Citation1966; Woldetsadik, Citation2004; Zerga et al., Citation2021).

Daily life and interactions between humans and the environment are governed by YeJoka Kitcha, a traditional Gurage governance structure. It encompasses different conventions of landscape administration (Kitchas) that structure people’s relationships with their surroundings, such YeJefore, YeSerege, and Ye-Debir. Native faiths including Waq (sky god), Bozhe (thunder god), and Demamwuit (fertility goodness) are practised in the area. These indigenous beliefs have historically shaped the region’s cultural landscapes and the ways in which people engage with the environment (Kirato, Citation2019; Mohammed, Citation2016).

According to Shiferaw et al., Citation2023b), Sahle and Saito (Citation2021a, Citation2021b) and (Shiferaw, Citation2017), the Sebat Bête Gurage’s cultural landscape is made up of forests (Debirs), home garden agroforestry (Gone), grasslands (Gero), wetlands, cultural road networks (Jefore), homesteads private space (Wereje), human settlement (Qaya), traditional dwelling (Guye), social organisations, and cultural assets. Village communities, respectively, create varied well-being engagements and perceptions for their shared and distinctive relationships with these cultural landscapes ().

Figure 1. Map of the Sebat Bête Gurage area (Source: After Sahle & Saito, Citation2021b).

Materials and methods

This research used ethnographic data collection methods such as observations, interviews, focus group discussions, and ethnographic conversations to identify patterns, themes, and insights about the research questions. The study focuses on three Sebat Bête Gurage districts, Cheha, Eza, and Gumer, representing the region’s socio-historical and ecological variables. Primary data were collected from 15 research sites selected from the three districts. With seven sites undergoing intensive interviews, focus group discussions, and observations and the rest sites served for key informant interviews and observations. The study involved sixty (60) ethnographic interviews to understand cultural landscapes, placements in people’s everyday living, perceptions and engagement experiences from community representatives, local government actors, and non-local residents. About eleven (11) focus group discussions were conducted with women, men, youth, and crafts, non-Gurage residents and local government actors to understand their views, perceptions and engagement experiences of their landscapes and dynamic experiences. About twenty (20) informal conversations were conducted to understand ordinary peoples’ views and experiences about their cultural landscape that were conducted in field and non-field settings.

The research also utilised observation as a research tool, which offers fascinating scenery that can be observed through simple observation. The Gurage landscapes present opportunities to observe a lot by just watching. The mindful watching provided insights into natural processes, socioeconomic activities, stock distributions, and ecological provisions. The Sebat Bête Gurage cultural landscapes serve as socio-ecological settings for daily living and engagement among social groups. Thus, village landscapes showcase diverse activities and interactions among various groups, providing an opportunity to observe their actions and understand the aesthetic values and non-human (livestock) activities of the landscape.

The Sebat Bête Gurage cultural landscapes are observed as natural and social settings, capturing physical features, settlements, housing traditions, home gardens, and socio-cultural practices. Photographs capture these landscape facts and their socio-economic activities. The method presents people’s engagement experiences with their socio-ecological settings, capturing important socio-ecological features and social activities, and documenting socio-cultural practices and dynamics around villages. Thus, our observations of Gurage landscapes were partially accompanied by photographs, as photos are more powerful than words in representing events and features.

The qualitative approach was employed for data analysis in order to comprehend the ethnography of the Sebat Bête Gurage cultural landscapes in terms of social groups’ views, perceptions, and engagement experiences. To better understand how social groups perceive and interact with village landscapes, a variety of data sources were consulted. Observation and photographic sources were used for result presentations and discussions. Therefore, qualitative analysis started with data collection during fieldwork, when the collected data was entered in the field note. Here, content analysis is a systematic method of categorising and classifying information from diverse data sources, identifying recurring themes, patterns, and categories. The analysis included coding and categorising information into topics and themes. The data was categorised into sub-themes and later into major themes based on research objectives, and organised and coded accordingly. The research questions were explored using content-based theme analysis to examine relationships among research issues.

Ethical considerations

This manuscript is part of the PhD project of the corresponding author. Before any field engagements, the appropriate communications and recognitions were made with concerned authorities and with research communities. At the beginning of our work, the corresponding author got a research support letter from the Wolkite University College of Social Sciences and Humanities, where the research localities were found (Ref. No. WKU-CSSH/306/2019). The study was approved by the research ethics committee of College of Social Sciences and Humanities, Wolkite University, Ethiopia. All research participants have provided informed consent. The Zone Administration wrote a support letter for research districts, whereas the research districts wrote a recognition and support letter for the primary researcher. With district support letters, the primary author made briefs about the research agenda and developed a rapport with villagers, village representatives, and elders, where we conducted intensive investigations. Interviews and photos were taken with the informed consent of the villages’ representatives, villagers, and elders. The primary research interviews and photo engagements with children were conducted based on their willingness and with the informed consent of the villagers and their parents. The primary author conducted field engagements with the informed consent of the research participants, including children, through their parents and community. By far, participants were willing to be involved in the study, including being captured by the authors in their shootings (photos) and aware of what was going on and why, including taking photos of non-human landscapes.

Results

There are three main topics in the results section. In keeping with our topic, the first section provides summaries of the cultural landscapes of the Sebat bête Gurage. The views and experiences of social groupings with village landscapes are presented in the second part. Power dynamics and conflicts in Gurage cultural landscapes are presented in the third section.

The Gurage cultural landscape: a synopsis of its major components

The broader settlement framework of the Sebat Bête Gurage is known as Qaya. It consists of diverse settlement features ranging from private to public landscapes. Here we shall summarise major components of the cultural landscape that provide a better framework for understanding our discussion. For the sake of brevity we focus on five major components.

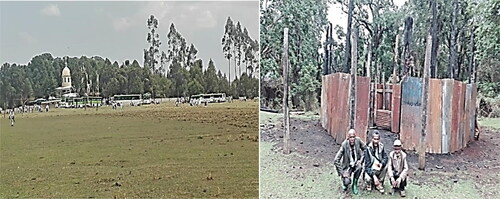

One of the most conspicuous components of the Sebat Bête Gurage’s settlement landscape is Jefore. In its literal sense, Jefore refers to the local road network and public space (See ). These culturally designed and carefully crafted spaces are what indeed make the cultural landscape of Gurage settlements unique in Ethiopia. In its essentialized and broader sense, however, Jefore refers to a village, a village membership/association, a socio-economic space, and a justice and equity space.

Figure 2. Jefore as green grass covered local road network and public space (Motta and Desene villages) left to right (Photo taken by corresponding author, August and September 2020).

In this latter sense, Jefore is an intricate concept in which various aspects of rural people’s life are embedded. It frames villagers’ attitudes, lifestyles, and interactions. Socio-culturally, it is a place where people have produced and reproduced, and continue to produce and reproduce, their personal and collective identities, memories, and histories; economically, it is a place of livelihood engagement and mutual support; ‘politically’, it affords villagers’ with space for participation in everyday social discourses, attainment of social justice and equity; and aesthetically, it is endowed with scenic settings having therapeutic values; ecologically, it is provides ecosystem gifts and qualities.

Serege is a village pastureland (e.g. ). The proportion of land that communities set-aside as Serege around settlements varies from village to village. Regardless of its size, however, Serge provides diverse services to villagers. First, as a public pastureland, Serege is a basis of livestock-related livelihood. Second, Serege also serves a social organising landscape unit as it frames cooperation along rotated collective livestock herding arrangement, which creates and sustains social and economic networks for everyday living among villagers. In the same vain, Serege, with its broader meaning as a clan pastureland, serves as a symbolic landscape through which sections of a clan who do not have direct access to pasture owing to physical remoteness, maintain their connection with the actual users of the land. Finally, some Serege, which are more endowed with diverse resources, provide villagers with opportunities to extract such resources as wood for firewood and house construction materials; woods and grass for craft products, medicinal plants, edible fruits, and hunting for their livelihood.

Figure 3. Sereges as village common or pasture in Weyeradeban village (Photo taken by corresponding author, September 2020).

Debir represents a forest reserve with different modes of ownerships, access and purposes. They are categorised under two domains. The first one is the community Debir, which is found across Sebat Bête Gurage districts with clan ownership and governance. Communities have ancestral rights to access and benefit from forest in this category (e.g. ). However, currently, timber product provisions are restricted to ensure the forest’s well-being and sustainability. The second category is the sacred forests locally named Ye-Waq Debirs (lit. god’s forest). They are the home of Waq, a sky god and/or mediator of the sky gods. Such forests, as the abode of the spirit, are governed by ritual communities through indigenous religious values. The forests are sites for sacred rituals and practices. Access is allowed for grazing, collection of non-timber forest products and for ecosystems and cultural services.

Figure 4. Debirs as community forest in Kotir village (Photo taken by the corresponding author, January 2020).

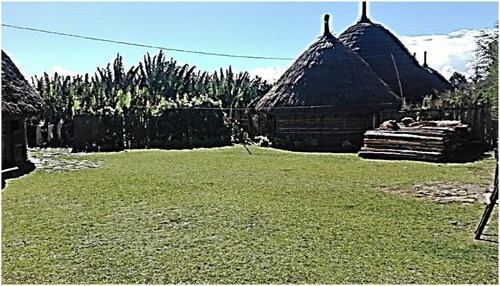

Guye is a basic dwelling unit for living, intensive social interactions, and wellbeing (). Guye is a reflection of vernacular architecture as a landmark of the Gurage countryside. The significance of Guye, in conjunction with Jefore, goes beyond being prominent cultural landscapes of the Gurage. They also are markers of Gurage’s cultural identity; expression of their cultural creativity and scenic beauty of Gurage’s countryside. In this context, one may safely claim that the popular imagination of the rural Gurage among Ethiopians at large is anchored on or influenced by Guye and Jefore.

Figure 5. Guye a traditional dwelling units of the Gurage in Denber village (Photo taken by the corresponding author, October 2020).

Guye has a range of sociocultural and ecological provisions, in addition to being a dwelling unit. It is considered a healthy setting for humans and livestock. Traditionally, it remained sound architecturally, socially, and ecologically as a living space and for intensive social interactions, wellbeing/therapeutic, cultural and ecosystem provisions.

Wereje is an open and green space between the homestead and Jefore (). Quash serves as a dividing line between this space and Jefore. Wereje is maintained for its socio-economic, aesthetic and recreational purposes of a family. It is seen as a private Jefore for its wider provisions and physical quality. The proportion of land allocated to Wereje by each household varies from 25 m2 to 200 m2.

Figure 6. Wereje: a private open space as socio-economic space in Denber village (Photo taken by the corresponding author, October 2020).

The five major components of Gurage’s cultural landscape, as briefly presented above, provide context for subsequent discussions on perception and engagement experiences of the diverse categories of people. For analytical purposes members of the Gurgae society are categorised along such structural elements as age, gender, occupation, and social status in the community. Non-Gurage residents, who have been engaging in and experiencing the Gurage’s culture and cultural landscape, have also been included as a category of their own.

Perceptions and engagements experiences of children

Brook (Citation2013) defines affordances in a child’s environment as physical, social, and cognitive experiences, as well as tangible and intangible benefits from a particular environment. Jefore is a significant place for children and teenagers, providing socio-ecological freedom, safe school journeys, and fostering interaction skills. It is a place where they develop a better personality, learn about community living and culture, and frame their imagination.

Jefore is a crucial social space for children and teenagers, serving as a safe and satisfying environment for daily activities, fostering social interaction, personal growth and active peer engagement. Sebat Bête Gurage’s children, regardless of age or sex, see Jefore as safe open spaces. Jefore is the primary playground for socialisation and personality development in Sebat Bête, where children continue to engage in social learning and engagement through home and village-based collective activities, facilitated by social networks during socio-economic practices.

Quality Jefore serves as a gathering point for village children; it also attracts children from nearby villages who are deprived of such opportunities. It serves as the main playground for children after school and on the weekends. Group discussants in school settings praised Jefore as a safe and enjoyable childhood environment, highlighting opportunities it provides for freedom and interaction. Many informants stressed that children’s participation and engagement in quality Jefore are crucial for enhancing their happiness, pleasure, and confidence. Many children and teenagers expressed Jefore’s quality from the level of satisfaction it provides them with. They stated that experiencing a degraded Jefore, one which is not well maintained or partially converted into other land use, diminishes their sense of belonging and enjoyment. This could result in children’s detachment from Jefore and confinement, to compounds due to safety and other concerns. The degradation or conversion of Jefore seems to be a concern or many children. A 12-year-old boy at Desene village expressed sadness over the decline of the Jefore at his village, stating that ‘no place is left for playground and childhood engagements’. Children also lamented that they are alienated from their Jefore in Desene due to intervention for road construction, which caused dust disturbance, traffic risk, loss of stocks and hens, and marginalisation in landscape provisions (see ).

Figure 7. Jefore as children playground and engagement place in Desene village left to right (Photo taken by the corresponding author, September and January 2020).

In addition to Jefore, according to our informants, children aged 12 and above engage in practical activities in Serege and Debir landscapes. These activities include: herding, firewood collection, edible fruit and root collection, swimming, and playing in open forest fields. However, engagement of children in these landscape categories appears to be limited due to their relative distance from settlements.

Perceptions and engagements experiences of youth

Youths (adolescents) have certain associations with village landscapes. They viewed, understood, and associated themselves with village landscapes based on their orientation. They have preferences for certain landscape types over others for certain advantages that they provide. For instance, they preferred Debir to Jefore as a private space for private activities (affection and study) and freedom. Debir also remains a site for recreation and relaxation, with good ecosystem provisions, for peers outside villages and out of the public site. On the other hand, they view Jefore common space where they enjoy public matters; as a space to observe community activities, which provides them with opportunities for learning their status and roles in the community and preparing to assume them. These perspectives continue to shape how young people perceive village landscapes.

Youth view and perceive Jefore as a collective leisure space; Serege as a collective task space and Debir as a more private space for affection. They engaged in landscape in accordance with village norms. Under normal circumstances, youth enjoy available public spaces for their private and public needs. For instance, during physical exercises and sports competitions, youth use either Jefore or Debir depending on the suitability of available spaces in these landscapes (See ). Jefore and Debir are also shared by non-villager youth for sports competitions, physical exercise, and other social activities in the absence of proper public spaces in their locality. During our observation and inventory, we have seen such opportunities across the landscape.

Perceptions and engagements experiences of women

Sebat Bête Gurage women hold a significant position in society, shaping their values, perceptions, engagements, and experiences in their socio-ecological landscape. They actively engage in village socio-economic activities and have extensive experience of its socio-ecological landscapes. Sebat Bête women value their landscapes as landmarks as of wellbeing and cultural identity; they demonstrate more active engagement and closer ties with the landscapes compared to men who tend to have frequent migration experiences. For instance, women’s engagement in and unique connection to Jefore is evident in their depiction of this landscape as a base for their domestic affairs. This demonstrates Jefore’s significance for women’s livelihood and socio-cultural life, which shapes (and is shaped by) women’s engagement experience and perception of such a landscape.

Jefore is a framework for mutual support and cooperation among women. It provides context for women to actively participate in such social networks as Wesacha (Gez) and Damada (Wejo) associations for labour and livelihood resource sharing. In this regard, women in each household have a small number of partners within a shared Jefore as an immediate social unit for collaboration and mutual support. To this effect, women often see Jefore as a source of social support and security in the event of socio-economic difficulties. Indeed, village norms dictate that each household mobilise resources through village heads or other social units to ensure the well-being of a member in need in the event of difficulties.

Besides, women view Jefore as the ‘guardian of their children’. They believe Jefore provides a safe socio-physical space for village women’s children during their absence from the village on market days and for other social occasions. Jefore is assumed to be free from holes and wild animals that could endanger children’s safety or cause physical injures; and social risks like theft and assault. Village children, who are unable to move with their parents, are taken care for by close relatives or other members of the community around their homesteads. One mother noted:

I think my birth place was very safe. Do you know why? Our Jefore provides safety for our children in our absence. There are no social or physical barriers or risks. It is very neat and green, which attracts our children for a long stay with social protection from the elderly.

Interview made with a woman age 50 at Desene village, December 2020

In sum, Jefore, as a village setting, is considered as an empowering setting for women. Women informants pointed to numerous opportunities provided to them by Jefore, including labour, social networking, cultural assets, and ritual associations, for fostering togetherness and common interests. However, it is to be noted that recent transformation occurring in and around Jefore are posing challenges to the safety aspects that many of our female informants tended to emphasise. For instance, the construction of roads passing through some Jefore and consequent increase in vehicles traffic, is posing threat to safety of the community, particularity children.

Perceptions and engagements experiences of the disadvantaged groups

Disadvantaged groups (the poor, the aged, and the disabled) viewed their Jefore as a ‘survival setting’, where they get closer support from the village community. According to informants from this category; Jefore is a basis of their livelihood in the context of which they receive diverse support from the community. Many poor people claimed that Jefore, Serege, and Debir serve as ‘home for their stock’. In this regard, households who are better endowed with farm and pasture lands forgo the use of these public commons so that the poor, who rely on them for farm and livestock productivity, can use them.

Sebat Bête villagers express the level of public attention to the disadvantaged by giving priority to them in access to communal resources particularly in the context of Jefore. This, in turn, makes Jefore a place of justice and equity in the community. Disadvantages can also receive socioeconomic support from better-off families and able bodies. In this regard, the Sebat Bête Gurage cultural landscapes are renowned for their diverse well-being contributions to disadvantaged groups, including socio-ecological resource provisions and economic benefits.

Perceptions and engagements experiences of men

Adult Gurage individuals actively participate in their villages and are responsible for maintaining their ancestors’ heritages and memories, and bringing new experiences as well. The Sebat Bête culture and identity are highly influenced by this category, as they serve as a bridge between older and younger generations. One man noted that ‘our landscapes are a result of our ancestors’ good intentions, and adults possess better knowledge and concern for village values, which they can share with younger generations’. He believes that parents have a significant responsibility to educate their children and youth to respect their culture and identity, as these have been handed down to them by their ancestors.

Most adults evidently felt responsible for sharing their experiences and life ways with younger generations. To them, Jefore serves as a reminder for them to actively participate in their culture and community., Accordingly, most informants and focus group discussants expressed that life is incomplete without long-established landscape values and norms that guide socio-ecological interactions. Adults, according to male informants, actively participate in villagers’ daily lives, serving as guardians of collective memories and promoters of village values and norms. One informant contended that adult men are actively working towards cultural survival, particularly in Jefore, to maintain and promote Sebat Bête traditions.

Jefore offers opportunities for cultural development and sustainability, with diverse observations and learning opportunities. The traditional Sebat Bête village maintains sustainable human-environment interactions. Elderly residents and adults discuss their ancestors’ traditions, preserving their values and heritage for future generations.

Perceptions and engagements experiences of elderly

According to Ward (Citation2013), the environment aids older individuals in accessing resources from their landscapes. The elderly informants emphasised that Jefore is the best space for attracting people for their social and economic activities. Older individuals hold strong memories of their ancestors’ heritage, interpreting their landscapes differently, influenced by their history, identity, heritage, and overall wellbeing in old age. Elders at Wegepecha heritage sites, recognising Jefore as their ‘eyes’, make emotional connections to the sacred through greeting and respect, often kissing and greeting sacred objects. Village landscapes have historical foundations and significance, and today’s elderly recognise and characterise their ancestors’ landscapes with their values, addressing disputes among dwellers by recalling and naming founders.

Older people associate village landscapes like Jefore and Guye with memory, physical and psychological well-being. They find emotional enjoyment and relaxation from their children’s engagement, stock distributions, and activities, preserving their past and ancestors’ memories. According to elders, what they have left behind today is their past and the memories of their ancestors. An 82-year-old man referred to Jefore as the ‘home of our memory’; while other elderly informants viewed local houses and public spaces as having health-enhancing qualities. For most elderly people, traditional houses are preferred to iron-corrugated houses for their superior living conditions, sociocultural, ecological, and health features.

Furthermore, open spaces like Wereje and Jefore offer better health through outdoor activities and relaxation. Elders believe Jefore provides space for advisory services for needy villagers, providing psycho-social and physical protection for many elderly individuals. An informant, aged 60, indicated that he frequently sought clarification on complex and unusual issues from older individuals aged 82 to 98. Data from a focus group discussion revealed that elderly individuals often seek information from more senior elders, even travelling long distances, to gain a deeper understanding on a given issue. Psychological, physical, and social protections are crucial for the elderly’s well-being in their cultural landscapes. Landscapes are often viewed as a source of reading for ancestors’ memories, histories, and contributions. For instance, an 82-year-old man shared his experience at Jefore as:

Every morning and before sunset, observing children and stock activities outdoors, I remember my participation in Jefore, a social and physical space that provides memory, energy, health, and positive emotions for life.

Interview made at Denber Village, November 2020

Perceptions and engagements experiences of craftsmen

Gurage villages consist of peasant and craft communities, with peasants considered cultured and better-off, and crafters considered less cultured, poor, and historically marginalised. A subculture group, known for their crafts, lived in farmers’ backyards as labourers, technology providers, and home-garden guardians. Service providers are now wandering villages in search of jobs and shelter, with cultural landscapes among craft communities being associated with economic rather than social aspects. The craft community perceives landscapes differently from mainstream cultural groups, with Serege and Debir landscapes considered more important for everyday livelihoods than Jefore.

This category of people have positive experiences with their everyday landscape; they use Serege as the foundation of their occupation with such provisions as wood, grass, bamboo, medicinal plants, and hunting ground. On the other hand, they use Jefore as a workshop site for craft activities and as a source of pasture for their livestock. The importance of Serege and Jefore as economic landscapes was expressed by the crafts as follows:

Jefore and Serege resources are crucial for our social base, enabling integration and support, and for our raw materials demand for craft making, medicinal plants, and hunting. While our Serege is mainly a production input source, Jefore serves as our workshop, children’s playground, and engagement.

Interview with a craft man age 55 at Sheremo village, September 2020

Figure 10. Dwelling qualities of craft verses peasant communities including spacing left to right in Zegba-Boto and Weyeradeban villages (Photo taken by the corresponding author, March 2019).

Our village lacks the presence of craftsmen, resulting in a lack of observation and proper care. They act as protectors and laborers in our homes and gardens. The labor shortage persists as most productive individuals have departed from their villages.

Interview made with a non-craftsman age 45 in Desene village, October 2020

Non-Gurage’s residents perceptions and engagements experiences

Non-Gurage observers often appreciate the socio-ecological landscape qualities of Sebat bête Gurage. People who had experienced the Sebat Bête Gurageland often emphasised the uniqueness of cultural and socio-ecological landscape qualities and provisions of Gurage villages, contrasting with their places of origin. Non-Gurage residents and visitors appreciate Sebat Bête Gurage’s village landscapes for their physical and social qualities, recognising their profound well-being contributions as culturally designed landscapes. They also express concerns regarding growing socio-ecological changes they have witnessed while living among the Gurage and their implications to people’s wellbeing. A non-Gurage high school teacher shared his perception and experiences of Gurage’s cultural landscapes, highlighting the village’s unique landscape qualities as:

The village setting and scenery differed significantly from my own culture, which was congested and unsuitable for outdoor activities or living. Here [In Gurage village], we spend our free time and weekends exploring home gardens and open fields for physical relaxation, emotional enjoyment, and quality weather. Village outdoor spaces offer socio-ecological benefits through such as socio-physical engagements, providing leisure and enjoyment through landscape crafting and care. Largely, the Sebat Bête landscapes offer a vivid depiction of a living and work environment where nature and culture coexist.

Interview with a man age 30 at Washe Village, October 2019

I have been a guardian of a home-garden left by a migrant family for three years, earning wages in the village. I have admiration for their house, local road, space, home garden, and vernacular house qualities. I also appreciate the inclusion of hospitality and social organisations in daily life and activities. Despite being from a different culture, I am not experiencing any frustration. The village’s socio-ecological landscape is exceptional, characterised by joy and quality, unlike any other places I’ve experienced.

Interview with a man age 27 at Kotir village, January 2019

The Gurage are wonderful for their vernacular and spacing. When I first saw and experienced such wonderful vernacular housing and road network (spacing), I wondered who designed it. They have great value for open space as well as for dwellings both indoor and outdoors. However, when I see Wolkite [a zone town of Gurage], things are contradictory, no sign of such a wonderful rural experience for spacing and housing; everything is congested.

Interview with a male informant, age 35, at Wolkite University, December 2019

Power dynamics and conflicts in Gurage cultural landscapes

In this section, we shall see power dynamics and conflicting interests that result in cultural landscape dynamics and new sets of relationships within the Gurage cultural landscape settings including the perceived generational divide regarding village landscapes.

Local government actors’ views and actions

Local government actors are recognising the Sebat Bête Gurage cultural landscapes as the optimal location requiring less cost for conversion into a certain infrastructure. They view village commons or landscapes as the most convenient for their intervention and encroachment interests. Local government actors in Sebat Bête Gurage villages often overlook the socio-cultural and ecological values of living landscapes, ignoring diverse wellbeing values. Experts suggest a gap in understanding these values stems from political and policy enforcement, and local actors’ ignorance, despite rural landscapes being integral to livelihood and well-being.

Local governments are transferring village landscapes to associations, investment groups, and religious institutions, which are less productive and sustainable. Many key informants have noted that the converted village commons happened to be less productive and sustainable compared to their previous values and provisions. Key informants and focus group discussants agree that the construction of roads through universal rural road access projects and other local road construction initiatives harm village landscapes and wellbeing. Many informants have noted that local government actors often fail to acknowledge the importance of landscapes, local values, and wellbeing roles.

Focus group discussants found that local government actors consistently prioritise development agendas over village cultures. Because of this fact, villagers are often compelled to make decisions between their traditional culture and the new development or infrastructure options that come to their villages. Local government agents emphasised the importance of roads for electricity, water, and town expansion but elderly people prioritise sustainable landscapes for their identity and human-environment interactions.

Interventions have significantly impacted their prior perceptions and characterisation of their landscapes and well-being, according to key informants and focus group discussants. During village meetings, we comprehended the emotions and feelings of villagers, while local government agents discussed intervention plans with them. The meeting attendees reported that the district governor had promised to preserve their heritage, Jefore, but failed to do so by destroying the village Jefore. Many villagers claim that Desene Jefore has lost numerous heritage values, potential, and socio-ecological qualities since then. Local administrators often lack awareness and concern for heritage values, leading to community competition and abuse over village landscapes due to government wrongdoing ().

Conflicting interests in village landscapes

The Gurage village landscape is characterised by competing interests and values, power relations, and conflicts among various religious institutions, particularly in the Debirs and Sereges areas. These competitions are growing among Muslims, Christians, and Christian denominations, forcing them to share a common. For example, Orthodox and Catholic churches are competing to dominate a sacred site in Wegepcha. Local officials argue religious groups compete for public landscapes, demanding access to a common. In Wegepcha, Orthodox and Catholic churches compete for a sacred site, with extremists targeting it.

The study indicates that certain interventions have led to a decline in the symbolic power, respect, and identity of sacred sites and ritual occasions. The symbolic power and identity of sacred sites have been losing following interventions, such as Orthodox Christians enjoying the temple of Wegepecha as a tourist instead of adhering to taboos. Traditional believers are angry at those who discredit sacred site values. The Orthodox Church shares a significant portion of the sacred forest with Catholics, but after conversion, they allowed the church to transform the territory. Local believers trust the Church to protect their ancestors’ heritage more than any other religious institution. Muslim followers claimed sacred forest, causing discomfort and opposition from non-Orthodox followers. Orthodox Church believed in protecting ancestors’ heritage, while non-Orthodox followers claimed forest landscapes as livelihood.

Rural-to-urban migration and competition drive cultural landscape changes in Sebat bête Gurage landscapes. This migration leads to the loss of labour and social organisations, transfer of ideas and technologies, and transformation of village socio-ecological values, vernacular houses, and supporting socio-cultural values. These changes are influenced by migrants’ material and non-material cultural competitions. Our observation reveals that the landscape transformations in villages are a significant factor in the cultural competitions between migrants, both material and non-material. In the focus group discussions, one active participant highlighted the impact of migration on village landscapes as follows ():

Figure 12. Degrading of sacred forests with competing religious values in Yesewa (shift to Orthodox Christian tradition) and Wegepecha (burning of sacred temple) left to right (Photos taken by the corresponding author, December 2020).

Our youth migration experiences have challenged long-standing traditions, marginalising socio-ecological values and norms among city children. Villages are dominated by women, elderly, and children, affecting home-garden activities and ecological and aesthetic qualities due to labor detachment.

A woman age 50 in Gulecho village, November 2019

Discussions

Humans are the primary users of space, so understanding their perceptions and the factors influencing them is crucial for creating desirable spaces (Khaledi et al., Citation2022). Sebat Bête Gurage’s cultural landscapes, influenced by long-standing values and norms, have been sustainable across generations; as cultural groups socially construct landscapes as reflections of themselves, using culturally meaningful symbols to create and reify a landscape from nature and the environment (Greider & Garkovich, Citation1994). Among the Sebat Bête Gurage’s the sustainability of landscapes is determined by successive generations’ efforts. Perception serves as the connection point between humans and landscapes, highlighting the daily interaction between humans and landscape entities (Khaledi et al., Citation2022).

Sometimes landscapes represent social power dynamics as human-landscape interactions are constructed (Spencer-Wood, Citation2010). Among the Gurage, generation gaps and contradictions in cultural landscapes are growing, with villages dominated by children, women, and older people due to youth migration. Elders emphasise the importance of ancestral home gardens as a living heritage, but youth lose interest and courage. Only the elderly, adults, and well-socialised youngsters are preserving traditions. Many young men express dissatisfaction with their village and prefer competing over scarce resources. Some stay to safeguard ancestral land for better living. Accordingly, youth’s contradictions with norms are due to their new lifestyle and cultural orientations. Sebat Bête Gurage’s cultural landscapes become contestation sites, with different interest groups competing to dominate and retain their interests.

Humans engage in both objective and subjective interactions with their environment (Khaledi et al., Citation2022). Other than socioeconomic differences of social groups, shared perceptions and engagement experiences exist in Gurage public landscapes as landscapes are crucial heritages for collective identity and well-being (Roe, Citation2013). As common understanding, social groups saw landscapes as gifts from their ancestors for sustainable uses and well-being in a region where land is scarce. They also saw landscapes as places where values of man-environment interactions, memories, identities, and associations with practical well-being are stored, along with the experiences, engagements, and orientations of successive generations. Accordingly, long-term dwelling can lead to familiar living environments and strong attachment, while moving to another location may cause rootlessness and changes in social interactions (Elo et al., Citation2011).

According to popular belief, village landscapes are the people’s histories, identities, and sources of income, as well as the mobilisation of institutional and sociocultural structures, and aesthetic and therapeutic associations in maintaining their well-being. As landscapes understood and perceived through the relationship between men and the space observed, among Gurage villagers, landscapes are considered as an everyday landscape for living, taskscape, and well-being. They serve as common polling locations for the villagers, common venues for socio-cultural and economic interactions among the villagers, and common engagement spaces that guarantee the well-being of the community by serving as therapeutic, recreational, artistic, and public meeting places. By far, landscapes reflect cultural identities, defining our understanding of nature and human relationships with the environment, as well as shaping our identity and future (Greider & Garkovich, Citation1994).

Landscape management and planning are impacted by socio-ecological characteristics such as age, gender, cultural origins, psychology, living environment, and social group orientations and affiliations (Wang et al., Citation2022). Thus, detached knowledge (intellectual and visual exercises) limits human interaction with the environment, limiting skilful coping and engagement experience with the environment and positing the material world as a prerequisite for human activities and social constructions are good for understanding landscapes (Douglas et al., Citation2018). Landscape scholars emphasise that people actively shape their perception of their place through engagements, experiences, and associations (Ilhan et al., Citation2022).

Dwelling as new phenomenology suggests that nature and culture coexist for resources, information, and a sense of living (Ingold, Citation2000). Accordingly, the Gurage acquires knowledge about their living landscapes through practical experiences, associations, and practical engagements in their dwelling and taskscape. The Sebat bête landscape, a dwelling unit, promotes mutual sustainability by interacting, sharing resources, and regulating each other’s activities. A social environment that promotes wellbeing involves receiving help, maintaining family connections, recognising friends as well-being providers, and fostering a pleasant living community (Elo et al., Citation2011). The study explores power relations, social boundaries, and differences in social structures in Gurage cultural landscapes. It highlights the challenge of maintaining diverse interests, values, and associations among social groups, as well as the shared and different well-being associations within village landscapes. The shared and different well-being associations within village landscapes are influenced by the geographical placements of Gurage and non-Gurage members and their orientations towards village landscapes. A symbolic environment that promotes well-being comprises ideal attributes, spirituality, normative attributes, and a sense of history and continuity (Elo et al., Citation2011).

According to Relph (Citation1976) a place’s knowledge is derived from human experiences, feelings, and thoughts. The Sebat bête Gurage cultural landscape offers outdoor activities for various groups. They serve as ground for sociocultural practices and venues for rituals and religious events. Howard (Citation2013) suggests that while there may be common factors among humans in their perception of their place, there are also numerous factors that create differences. Sebat bête Gurage cultural landscapes share common experiences with socio-ecological settings, with different associations perceived by different social groups based on living and social orientations.

Landscapes have typically been produced by varied, diverse, and long-term interactions between people and nature (Garau et al., Citation2023). The Gurage landscapes are part of such realities in sustaining life and well-being for villagers. They showcase the interplay between nature and culture, providing resources and information for both human and non-human living. According to Tenzer (Citation2024), landscapes are composed of physical places, affording meaning-making and value creation from everyday heritage based on personal experiences, life histories, memories, traditions and heritage practices. Among children, village landscapes are seen as a space for learning, socialisation, friendship, and community values among children. They also serve as a playground, a place for role-taking, and a reflection of ancestors’ wisdom. Youth view their village landscapes as spaces for socio-economic responsibilities, sport, and affection. For youths, village landscapes are seen by youth as a reflection of their ancestors’ wisdom, a space for socio-economic responsibilities, sports, recreation, socio-cultural practices, and a hub of friendship and affection.

Landscapes, shaped by personal experiences and traditions, create value and attachment, fostering a sense of belonging and identity among people and places (Tenzer, Citation2024). Village landscapes are seen by women as a reflection of their ancestors’ wisdom, a livelihood, a social space, a place for children’s development, a place for expressing gender rights, and a social network. Individually [a social group] held values form the basis for attachment and connection between people and places (Tenzer, Citation2024). For men, village landscapes are seen as ancestors’ gifts, a responsibility for children, a stage for futures, a learning environment, and a hub for community social networks and values. Village landscapes are also seen as a reflection of ancestors’ wisdom, memory, participation in social justice, sharing knowledge, therapeutic space, social support, and relaxation for the elderly. Among craft communities, village landscapes serve as livelihood extraction sites, socialisation grounds, medical plant extraction sites, socio-economic benefits hubs, craft workshops, village social networks, and children’s wellbeing centres. Village landscapes are seen as livelihood and wellbeing places, providing socio-economic benefits and community support for disadvantaged groups. Non-Gurage perceives Gurage landscapes as unique, attractive, and harmonious, contributing to wellbeing and aesthetics.

Cultural landscapes as a reflection of their creators, actively fostering, reproducing, and transforming social relation (Deborah & Michael, Citation1997). Generation gaps exist among dwellers, with youths growing up with socio-economic demands and modernity exposure, while adults and elderly strive to preserve long-lived village landscapes, despite competing values and interests. The craft community faces competition in exploiting public cultural landscapes, while government interests over infrastructure development distort outdoor landscapes. Women are confined to indoor activities, and women rarely engage in non-domestic activities in village landscapes, except for ritual occasions. The importance of cultural ecosystem services is influenced by spatial and social factors where some elders prioritise nature experiences and younger preferring social interactions (Riechers et al., Citation2018). There are shared perceptions about the village landscapes as common public space, for macro social and historical significance, and engagement activities that allow villagers to come together for collective actions and benefits around landscapes like public gathering, open space opportunities, common pasture, social justice and equity for village landscape benefits and participation, despite the differing perceptions and engagement experiences in line with social groups’ specific landscape association. Landscapes are recognised as communal identities characterised by allusions to ancestors and equal possibilities for socio-cultural and economic advantages regardless of the social group’s history.

By far, landscape encompasses the deceased, living, dreaming ancestors, parents, grandparents, and more (Bird, Citation2013). The Gurage also exhibit landscape orientations that align with their ancestors’ crafted landscapes. Villages often associate themselves with these landscapes, preserving their cultural and ecological associations. The Sebat bête Gurage cultural groups perceive their everyday landscapes as totalities of everyday living and memories of ancestors. The Sebat Bête Gurage villages’ cultural landscapes are evident from a dwelling and multifunctional landscape perspective. Anthropologist Colin Scott emphasises the crucial role of human-animal-plant relationships in practical empirical knowledge that informs land decision-making (Andrews & Buggey, Citation2008). In this regard, the Gurage village landscapes promote ideal and practical dwelling, allowing for the interconnectedness of nature, culture, and human-non-human living beings, promoting sustainable landscape and sustainable living. They involve the sharing of resources, energy, information, and care for sustainable landscapes. The living socio-ecological landscapes of the Gurage, which include both human and non-human species, collaborate to support village life and well-being. As an alternative to traditional epistemologies, which frequently divide people and space, the concept of dwelling, which refers to the relationship between humans and their environment and is influenced by the ‘ontology of dwelling’ and the transient nature of the landscape (Douglas et al., Citation2018).

The dwelling as landscape idea, according to Finch (Citation2013), contends that a perceiver’s engagement in the environment shapes human meaning and sense-making. Such conceptualizations of dwelling and engagement experiences are more reflective of what the Gurage social groups saw and experienced in their daily lives. Shared interactions and experiences with natural environments provide opportunities for social interaction and strengthen networks between social groups and communities (Peng, Citation2020). Our study examines the temporality of landscapes through engagement and dwelling experiences, revealing the diverse perspectives and relational experiences of social groups when interacting with their own landscapes.

Multifunctional landscape approach, take into account the diverse values of a landscape and/or landscapes across social groups in the Sebat Bête Gurage villages, support and quantify sustainable landscape maintenance and reduce conflicting interests around landscapes. People are increasingly realising that interactions with nature benefit psychological, social, and physical health and well-being (Peng, Citation2020). The Gurage village landscapes are multifunctional, with traditional dwellings, spacing units, forest, and public pasture serving diverse functions within their socio-ecological landscape frameworks. These landscapes have shared and specific functions among villagers, reflecting social structures and value associations.

According to Bolliger et al. (Citation2010), the concept of landscape multifunctionality provides a suitable framework for incorporating the effects of several environmental stressors working on the landscape. The fact that relationships with landscapes were patterned to manage fair or balanced interactions with immediate landscapes as well as accompanying diverse interests in line with potential landscape provisions for group satisfactions and livelihood and well-being orientations is also evident in the congested human-environment interactions where resources are limited. Our shared landscapes encompass biological and cultural diversity, habitats, and heritage, with cultural landscapes expressing livelihoods, spiritual meanings, traditions, and practices (O’Donnell, Citation2023). The varied landscapes of the Sebat Bête Gurage village landscapes offer a variety of options for various parties. The symbiotic relationship between humans and the landscape is increasingly promoted as an ideology for sustainable living (Kato & Ahern, Citation2009; Kidd, Citation2013).

According to Hedblom et al. (Citation2019) landscape changes impact such symbiotic relationships and landscapes wellbeing and perceptions or associations benefits. An increasing body of research shows how shifting landscapes affect social groups’ perceptions and engagement experiences in ways that differ from their previously favourable correlations. Today, due to urbanisation, food demand, agricultural abandonment, and climate change, the world’s landscapes, particularly rural ones are changing quickly (Hedblom et al., Citation2019). In line with such changes, the opinions of rural inhabitants, part-time residents, tourists, and prospective immigrants are all challenged by these changes, since they have varying expectations regarding the landscape’s function (Soini et al., Citation2012). The Sebat Bête Gurage villages’ residents’ lost common interests and values for their everyday landscapes as new values and functional orientations shaped their landscapes. Generally, landscape preferences and reactions in various situations can be influenced by a variety of characteristics, including age, gender, cultural origins, psychology, and living environment (Zhang et al., Citation2022).

Conclusion and ways forward

The 1995 Ethiopia’s constitution promotes cultures and heritages that positively impact human and environmental wellbeing (Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Citation1995). Basically, in order to build and sustain appealing environments, it is vital to take into account the views of users as well as the elements that impact human perceptions of these spaces (Khaledi et al., Citation2022). Those landscape perceptions and engagement experiences have an impact on landscape management and planning (Wang et al., Citation2022). The Gurage landscapes have strong dwelling and multifunctional aspects associated with the mutuality of landscape aspects.

The perceptions of landscapes significantly influence the way landscapes are reshaped and planned and intervened (Garau et al., Citation2023). The Sebat Bête village landscapes framed villagers’ perceptions and engagement experiences and memories within human and human-ecological interaction frameworks. Landscapes affect perceptions after interaction through experiential, cognitive, and emotional engagements and landscape socializations (Peng, Citation2020). Among the Gurage, village landscapes are places where memories, identities, and engagements are associated with respective social groups’ orientations, as well as shared understandings and experiences for the entire village communities. Roe (Citation2013) highlights landscape as a reflection of interaction, encompassing embodiment, engagement, phenomenology, mutual transformation, association, meaning, indigenous knowledge, dwelling, traditions, identity, cultural values, place attachment, quality, and sense of place. When places [landscapes] are altered, neglected or damaged, such connections can be lost, and the quality of place diminished (Tenzer, Citation2024). These facts are also remaining reflections of the Sebat bête Gurage landscapes characteristics and provisions. However, among the Gurage’s the cultural landscape assets are being threatened by conflicting demands among social groups; as society uses space to reinforce and resist power, authority, and inequality by organising the landscape to facilitate certain activities while constraining others (Deborah & Michael, Citation1997).

Landscape socialisation can enhance human-nature connections, involving experiential, cognitive, and emotional aspects and long-term structural changes, like policy interventions, can deepen these connections (Peng, Citation2020). Understanding local landscape realities is crucial for sustainable human-landscape interactions and promoting landscape sustainability as a source of living and wellbeing. As landscape scholars, our actions, based on an understanding of entangled and inseparable Nature and Culture, offer a platform for effective cultural landscape undertakings (O’Donnell, Citation2023). By large, Ethiopia’s constitution promotes cultural heritage with equal privilege for all nationalities, respecting humanity, social justice, gender equality, peaceful coexistence, and the environment (Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Citation1995). The state has the responsibility to protect and preserve these legacies, contributing to art and sport promotion. This constitutional stand is crucial for understanding local government actors’ responsibilities for heritage values in the Sebat bête Gurage areas. In the meantime, understanding public perceptions of landscapes is crucial for landscape governance. Local people’s personal stories, memories and traditions can be meaningfully and efficiently integrated into the official frameworks of planning and decision-making (Tenzer, Citation2024). Stakeholders’ decisions and interventions in Sebat Bête Gurage landscapes need to consider diverse values and associations of landscapes that have been maintained over generations. Participatory mapping is a valuable method for capturing people’s perceptions, mental models, and local knowledge of ecosystem services through spatial representation (Elo et al., Citation2011). Therefore, a sustainable landscape needs to be the aspirations and desires of the decision makers in the midst of new sets of values for human-environment interactions.

The Sebat Bête Gurage’s growing competing values and interests must be balanced with prior cultural landscape values to ensure unique traditional landscapes multifunctionality.

Respecting landscape forms and provisions help to preserve the broader cultural landscape framework multifunctionalities, as it demonstrates cultural landscape mutuality across villages.

Landscape dynamics aspects as the new face of Gurage village landscapes resulted from competing interests and aspirations of interest groups and generation gaps, so policy directions and considerations are necessary for balanced interventions around landscapes.

Effective constitutional recognition and protection of nations’ landscape heritage values is crucial for preserving multifunctional landscapes that support diverse social groups’ wellbeing and interests in both micro and macro settings.

The study’s limitations and implications for future research

The study has limitations in understanding and farming competing values, interests, social structures, and boundaries within Gurage cultural landscapes. Thus, further research is needed to understand such gaps in the midst of landscape transformation through an interdisciplinary research approach to frame social-scientific planning to respond to changes for the multifunctional landscapes.

Acknowledgements

The researchers express gratitude to Addis Ababa University College of Social Sciences for financial support for fieldwork, acknowledge Gurage informants for data contributions, and thank Mr. Habtamu Wondimu and Dr. Belay Zerga for manuscript reading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abinet Shiferaw

Abinet Shiferaw is a PhD Fellow at Addis Ababa University in the Department of Social Anthropology and a lecturer at the Department of Sociology at Wolkite University. He has over twelve years of research and teaching experience. He conducted ethnographic surveys in the peripheral regions of Ethiopia and participated in the National Intangible Cultural Heritage Inventory Collaboration with UNESCO and ARCCH. He has two published articles in reputable journals of Landscape Research and Northeast Africa Studies in Michigan State University press and he has a book chapter and ethnographic documentary on the Komo ethnic group. His research interests fall into landscape studies and sociocultural dimensions of vernacular architecture.

Mamo Hebo

Mamo Hebo and Getachew Senishaw are assistant professors (PhD) and senior advisors, researchers and lecturers at Addis Ababa University in the Department of Social Anthropology with publications and research interests on land, land governance, legal pluralism, livelihood, and indigenous knowledge.

References

- Andrews, D., & Buggey, S. (2008). Authenticity in aboriginal cultural landscapes. Journal of Preservation Technology, 39(2–3), 1–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25433954

- Barbara, B. (2006). Place and landscape. In C. Tilley, W, Keane, S. Kuechler, M. Rowlands, & P. Spyer (Eds.), Handbook of material culture (pp. 303–314). Sage.

- Bieling, C., Plieninger, T., Pirker, H., & Vogl, C. R. (2014). Linkages between landscapes and human well-being: An empirical exploration with short interviews. Ecological Economics, 105, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.05.013

- Bird, D. (2013). Fitting into the country. In P. Howard, I. Thompson, and E. Waterton (Eds.), The Routledge companion to landscape studies (pp. 9–11). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203096925

- Bolliger, J., Bättig, M. B., Gallati, J., Kläy, A., Stauffacher, M., & Kienast, F. (2010). Landscape multifunctionality: A powerful concept to identify effects of environmental change. Regional Environmental Change, 11(1), 203–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-010-0185-6

- Brook, I. (2013). Aesthetic appreciation of the landscape. In P. Howard, I. Thompson, & E. Waterton (Eds.), The Routledge companion to landscape studies (pp. 108–118). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203096925

- Buendía, A. V. P., Albert, Y. P., & Giné, D. S. I. (2021). Mapping landscape perception: An assessment with public participation geographic information systems and spatial analysis techniques. Land, 10(6), 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10060632

- Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. (1995, August 21). https://www.refworld.org/legal/legislation/natlegbod/1995/en/18206

- Deborah, L., & Michael, S. (1997). Class, gender, and the built environment: Deriving social relations from cultural landscapes in Southwest Michigan. Historical Archaeology, 31(2), 42–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25616526

- Douglas, I., Huggett, R., & Perkins, C. (2018). Companion encyclopedia of geography: From the local to the global. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203694640

- Elo, S., Saarnio, R., & Isola, A. (2011). The physical, social and symbolic environment supporting the well-being of home-dwelling elderly people. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 70(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v70i1.17794

- European Landscape Convention. (2000). [website] Council of Europe. http://www.coe.int/t/e/Cultural_Co-operation/Environment/Landscape/

- Finch, J. (2013). Historical landscapes. In P. Howard, I. Thompson, & E. Waterton (Eds.), The Routledge companion to landscape studies (pp. 143–151). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203096925

- Garau, E., Josep, P., Amanda, J., Garry, P. J., Albert, N. R., Anna, R. P., & Josep, V. (2023). Landscape features shape people’s perception of ecosystem service supply areas. Ecosystem Services, 64, 101561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2023.101561

- George, C. (2012). Landscape in mind: Dialogue on space between anthropology and archaeology. Time and Mind, 5(2), 221–224. https://doi.org/10.2752/175169712X13276628335203

- Greider, T., & Garkovich, L. (1994). Landscapes: The social construction of nature and the environment. Rural Sociology, 59(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.1994.tb00519.x

- Hedblom, M., Hedenås, H., Blicharska, M., Adler, S., Knez, I., Mikusiński, G., Svensson, J., Sandström, S., Sandström, P., & Wardle, D. A. (2019). Landscape perception: linking physical monitoring data to perceived landscape properties. Landscape Research, 45(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2019.1611751

- Howard, P. (2013). Perceptual lenses. In P. Howard, I. Thompson, & E. Waterton (Eds.), The Routledge companion to landscape studies (pp. 43–53). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203096925

- Ilhan, Ö. A., Balyalı, T. Ö., & Aktaş, S. G. (2022). Demographic change and operationalization of the landscape in tourism planning: Landscape perceptions of the Generation Z. Tourism Management Perspectives, 43, 100988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2022.100988

- Ingold, T. (2000). The perception of the environment: Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203466025

- Jackson, R., Shiferaw, A., Taye, B. M., & Woldemariam, Z. (2020). Landscape multifunctionality in (and around) the Kafa Biosphere Reserve: a sociocultural and gender perspective. Landscape Research, 46(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2020.1831460

- Johnston, R. J. (1998). Approaches to the perception of landscape. Archaeological Dialogues, 5(1), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203800001161

- Kato, S., & Ahern, J. (2009). Multifunctional landscapes as a Basis for Sustainable Landscape Development. Journal of the Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture, 72(5), 799–804. https://doi.org/10.5632/jila.72.799

- Khaledi, H. J., Khakzand, M., & Faizi, M. (2022). Landscape and perception: A systematic review. Landscape Online, 1098. https://doi.org/10.3097/LO.2022.1098

- Kidd, S. (2013). Landscape planning: Reflections on the past, directions for the future. In P. Howard, I. Thompson, & E. Waterton (Eds.), The Routledge companion to landscape studies (pp. 366–382). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203096925