Abstract

This article proposes a methodology for analyzing the social network behaviour of the extremist group (Al-Shabaab) within the context of ungoverned spaces in the Horn of Africa. Inkblot logic is introduced as an analytical framework that highlights the role of ‘loose bonds’ and ‘hard bonds’ in the geographical distribution of terrorists’ activities ranging from the group’s epicenter in Somalia to neighboring Kenya. Traditionally, policy analysts and researchers have studied the behavior of extremists on the basis of in situ, i.e. their static geographical position. However, the stasis approach assumes that extremist groups operate in fixed position relative to the perceived enemy. Yet the elusive group has been found to establish complex familial or fictive kinship networks beyond their country of origin, while maintaining a local presence embedded within communities. Hence, efforts to predict their movements and spatial distribution can prove difficult. The inkblot approach is of theoretical and practical use, as it illuminates possibilities of indirectly plotting the ‘ungoverned spaces’, hence, improving predictability of terrorists’ activities in time and space within the kinship networks.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Kenya’s concerns over security threats and terror-related activities rekindled by ‘ungoverned spaces’ in Somalia remain a top priority of its security initiatives in the Horn of Africa. This is not surprising, given that there has been a substantial increase in the number of actors carrying out one-sided violence in Africa since 2011 (Bakken & Rustad, Citation2018). This emerging threat to peace and security in the Horn of Africa illustrates why the presence of ‘ungoverned spaces’ raises concerns. To the extent ungoverned spaces in Somalia is a threat to national security of neighboring states, there may be insights in the nexus between absence of state authority as the main allocator of resources and stability of the region (Clunan & Trinkunas, Citation2010; Taylor, Citation2016). This makes sense, because ungoverned territories have been characterised as being under governed, ill-governed, contested spaces and exploited areas (Diggins, Citation2011).

Ungoverned space is not limited to the physical properties of nature (land, air, and sea). It is also a conceptual absence of a state’s capacity to exercise control over the space and the population within its territory (Whelan, Citation2006; See Rabasa et al., Citation2007). Simultaneously, this paradigm has been used for centuries to understand the relationship between ungoverned territories and the prevalence of conflict; the proliferation of small arms and light weapons (SALW); and thievery, ranging from cattle rustling to sea-related criminal activities such as piracy (Onwuzuruigbo, Citation2020). At the behest of the de-facto rulers of a territorial space ungoverned by the state, national stability as well as regional peace and security are being fundamentally challenged due to the ‘diffusionary’ nature of kinship traits among African societies. Social scientists have defined diffusion as a social process and activities that occur among people in response to learning of, or adoption of, a decision about an idea that the leader would like to have integrated among those who subscribe to a culture, religion, or social class (Dearing & Cox, Citation2017), such as an Islamist clarion call against so-called infidel Christian invaders. In this article, ‘diffusion’ refers to the spatial spread of terror-related activities and assets across territorial borders from ungoverned spaces in Somalia to other states, such as Kenya, in the Horn of Africa.

Al-Shabaab’s power and influence appear to be rapidly migrating into Kenya in a fashion similar to the behaviour of an ‘inkblot’ as it spreads. In this article, the logic of an ‘inkblot’ is used to describe Al-Shabaab’s networks, which diffuse from areas of high concentration in Somalia to areas of low concentration in Kenya. In many occasions, they carry (along with them) methods of warfare, ideological orientation, and tactics. The group’s penetration of Kenyan society is largely based on kinship networks and Muslim brotherhood networks. Northern Kenya, the area of the country that borders Somalia, is predominantly occupied by people of Somali origin who confess the Islamic faith. Blood kinship and religious or ideological brotherhood have been found to sustain ferocious neo-tribal behaviours (Ronfeldt, Citation1996). Some communities fight to retain their traditional clan systems, and any intrusion of market structures or unfamiliar cultural practices are violently resisted.

I argue that a group of people with similar descent (kinship) may find it beneficial to forge transnational ties of solidarity through a shared kinship lifestyle. However, the ‘export’ of terror-like behaviour from the ungoverned spaces in Somalia into Kenyan territory remains unacceptably problematic in its spreading of violent extremism and threats to national security. One reason for the persistence of the terror-related insecurity in Kenya is that the phenomenon of the ‘export’ of terror from ungoverned spaces in Somalia, though an important topic of study, has been surprisingly under-researched. Interrogation of the factors that enable terrorist activities to be exported to Kenya is useful for two key reasons. First, it potentiates a better understanding of the relationship between ungoverned spaces and the ‘export’ of terrorist activities. Second, it assesses whether and how it may implicate Kenya’s national security architecture, and can assist the Kenyan government in its development of a robust suite of potently effective counter-terrorism (CT) measures.

This article seeks to unravel the factors enabling the ‘export’ of the Al-Shabaab terrorist group’s behaviours and activities, and to examine the vulnerability of Kenya’s national security to the threats posit by the group. To this end, the article contains four sections. The first theorizes the relationship between ungoverned spaces and the notion of ink-blot diffusion network. The second describes the typologies of ungoverned spaces. The third provides an overview of how the Al-Shabaab group evolved in Somalia and the intricate relationship of the group with Kenyan territory. The final section develops propositions for understanding the association between ungoverned spaces and the diffusion of terror groups with the conclusion outlining the implication of the proposed model of studying terror groups on framing of counter-terrorism strategies in the Horn of Africa and beyond.

Theorization of inkblot diffusion network of Al-Shabaab in ungoverned spaces

When Ann Clunan and Harold Trinkunas (Ronfeldt, Citation1996) advance the concept of ungoverned spaces within the broader framework of state sovereignty, they inform the reader that the existence of such spaces should be understood as being a sign of a failed state or a suspension of what they call ‘effective state control.’ Marc Lynch (Citation2016) builds upon the duo’s conception to explain how non-state actors could exploit ungoverned spaces to form criminal gangs – or, worse still, terrorist groups. Closely related to the failed state thesis above is the category identifying weak states. Patrick Cronin (Citation2009) combines geographical and population parameters in order to frame what constitutes ungoverned spaces as being not only isolated regions of inhospitable terrain that governments cannot easily reach, but also the migrant- and immigrant-populated slums and the inaccessible border regions of well-governed states.

We cannot develop a sound conceptual framework of what an ungoverned space is without interrogating the existing debate on the subject. Among the emerging explanations attempting to address the question of the spread of terrorist activities is the argument that ungoverned spaces and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) occur in a circular spiral of causality, causing increased access to such weapons beyond the ungoverned territories (Cronin, Citation2009). The RAND Corporation (Cronin, Citation2009) refers to this phenomenon as being ‘awash in arms’, meaning that increasing non-state actors’ access to weapons creates an unhealthy competition with the state over the legitimate use of force. The alternative, and equally prominent school contends that the presence of ungoverned spaces is associated with criminal networks – a blemish, stain, or mark against the state; a stain that transiently mars and spreads in the way an ‘inkblot’ does. The ‘inkblot’ explanation cautions against the simplistic linear causality advocated by the ‘awash in arms’ school. The inkblot school’s contention is that a complex and intricate network of militant forces – acting and reinforcing each other across international boundaries – causes the ‘export’ of terror behaviours from ungoverned spaces (Okley & Proctor, Citation2012). In other words, the effects of ungoverned spaces are transient beyond their places of origin. The debate goes further to explore how weak borders fail to mitigate threats to peace and security in Africa. However, the focus has been on the effects of ungoverned spaces within the affected country’s territorial spaces. Yet, as is evident from the terrorist activities of Al-Shabaab in Somalia (emerging from within its largely ungoverned spaces) and Kenya (importing terroristic behaviours), how the behaviours and activities of a terrorist group diffuse into the neighbouring state through ‘borderless borders’; and the associated security risks remain unresolved questions.

Recently, several scholars have linked ungoverned spaces to inaccessibility, the dilapidation of spatial infrastructure, and misgovernment, all of which could invite socio-cultural and political resistance to state penetration (Teo, Citation2018). The absence of state control creates an environment conducive to the growth of terrorist groups. Here, the natural attitude, in many ways, is that of questioning the legitimacy of the state and its institutions. Accordingly, this ‘vacuum’ could easily be filled with cultural entities – clan feuds, ethnic groups, religious fundamentalists, radical youths, tribes, or loose social kinship fabrics. The maturation and diffusion of this form of networking defines society’s basic culture, including civic traditions, political organization and blood kinship. The blood kinship phenomenon is not confined to the people of Somalia by origin. Instead, it can be found in many parts of the world. For instance, the Pashtun tribe located in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan (FATA) has a long history of resistance to external authority, dating back to colonial times (Teo, Citation2018). Similarly, the Muslim inhabitants of Mindanao have contested the authority of the Manila government and its religious and cultural orientation since the Spanish colonial era. Likewise, the Caucasian and Chechen peoples in the Northern Caucasus have resisted the influence of modern Russian culture. Domitilla Sagramoso (Citation2007), for example, has observed the relationship between some Chechens’ perennial violence and the heavy-handed influence of Russia:

[A] loose network of formally autonomous violent groups or Islamic jamaats has developed throughout the region, primarily in the Muslim republics of Ingoshetia, Dagestan, Karachaevo-Cherkessia[……] and Kabardino-Balkaria.

The differences or similarities between ungoverned and governed spaces is not that simple. One does not necessarily mirror the other. In an ideal natural setting, the rule is that if I can see you, it means you are visible and present. But in the phenomenological context of existence, things are not that straightforward. The concept of governmentalism is always imperfect. The relational aspect of intergovernmentalism points precisely to the fact that it is a system akin to international treaty. In Michael Foucault’s (Cited in Barry Hindess, Citation2005) conception of government, powers of the central authority are limited; each state is obligated to observe and respect the rights and competences of other states. This relationship so far has been one of the contributing factors to the question of legitimate authority. For instance, by the virtue of Somalia’s sovereignty, Kenya cannot dictate how the former ought to be held accountable for the actions of the militant group Al-Shabaab, born and bred within Somali territory. However, as alluded to in the foregoing discussion, sustaining a governable state requires the protection of the state’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, and the building of statehood or nationhood. In part, the purpose of this article is to resolve the conceptual tensions between what constitutes ‘ungoverned spaces’ and ‘governed spaces’ – resolving this tension by framing the various perspectives into the three aforementioned propositions.

The first proposition approaches the concept of sovereignty. Within the confines of international law, the key defining elements of sovereignty are recognition, the state, authority, coercion, and territory. Stephen Krasner (Citation2001) classified sovereignty into two types – international-legal sovereignty and domestic sovereignty. In this regard, sovereignty is concerned with the inviolability of borders and freedom from external interference in a state’s domestic affairs. In this world order, states interaction cannot be determined by one sole actor. For example, even though the Al-Shabaab terrorist group’s activities in Somalia perhaps tangentially implicate Kenya’s national security Kenya cannot dictate the domestic policy of Somalia. An emerging argument is that ungoverned spaces create opportunities for organized groups to express and articulate their collective interests. Where this phenomenon is not managed by the state’s machinery and governance structures, these other groups tend to dominate the space. In such an environment, therefore, legal sovereignty belongs to the state, while political sovereignty resides in the organized group. This conflict between legal and political sovereignty implies that the efficiency of the state to deploy force and/or forces and fight against terror groups is greatly hampered. This phenomenon can be worsened by kinship networks established between the terror group and the local population. As such, ungoverned spaces can be areas that are poorly governed; or they can be areas located within otherwise viable states, yet being places where the central government’s authority does not extend (Rabasa et al., Citation2007). However, as has been pointed out by Prinz and Schetter (Citation2016), there is need for a distinction between forms of ungoverned spaces, as (particularly when viewed from a surveillance perspective,) the term is often extended to encompass virtual realms, such as the dark web, that may undermine state sovereignty.

Territorial integrity is a key component of sovereignty. Effective border controls define the territorial integrity of a state. The sum of it all is the outcome of a governable space characterized by a stable security situation. Within the doctrine of Responsibility to Protect (R2P), there are two important assumptions undergirding territorial integrity: (1) If a state is not effective, then the state’s territorial rights could come into question; and (2) any group that is able to impose order or demonstrate effectiveness could gain territorial rights in given areas (Bellamy, Citation2009). Thompson (Citation1995), emphasizes that territorial integrity therefore goes beyond sovereignty to encompass building tight linkages between the state and its people. Ungoverned spaces cannot simply be classified as physical locations where state authority functions poorly by normative standards, but also where it is altogether absent in its normative enforcement. As shown by Richard Mallet, such ‘mental spaces’ unconstrained by loyalty to a state’s governance are characterized by physical manifestations of this ideological rejection of the state’s rule of law, thereby resulting in lawless, uncontrolled territories, black markets, and places where state regulation is absent (Mallet, Citation2016).

The second proposition is territorial deprivation. Advocates of this school of thought argue that the formation of political or social movements is hinged on the need to address the prevailing conditions. Social movements have been known to metamorphosize into extremist groups with the aim of conducting terror-related activities (Hansen, Citation2013). When the initial social movements fail to reach their desired goals, they give birth to terrorist movements (Gamson, Citation1975). Whereas grievances are driven by mainly ideological factors, identity politics in Somalia have precipitated clan tensions, and distorted religious grievances have played a role in creating unity among the aggrieved group (Hassner, Citation2003). This political Islam bequeaths terror groups with the ability to interpolate long-term religious goals and a united focus on issues. On the relationship between religious ideology and diffusion of terror activities, Weinberg et al. construct grievances as representing four elements: (1) injustices, (2) political oppression, (3) identity, and (4) religious divisions (Weinberg et al., Citation2004). Indeed, modern greed-grievance theorists Regan and Norton (Citation2005) have now explained the existence of strong, direct links between identity and the spatial distribution of terror activities. In other words, the presence of violence on one side of the border can be explained by the formation of similar groups in the neighbouring localities, especially where such groups subscribe to a similar religious or cultural orientation.

On a similar note, territorial deprivations can lead to a state of grievance. The term ‘relative deprivation’ connotes the gap between what individuals hope to achieve and what they desire to achieve. If this gap is widened, then rebellion is likely to occur. Gurr avers that the more individuals feel deprived in their local setting, the more they are likely to initiate mobilization/recruitment initiatives that traverse beyond their territorial spaces. Al-Shabaab uses the internet to launch propaganda aimed at recruitment and resource mobilization, mainly in Kenya. As a result, the Somali diaspora has become impressed and has become a partner remitting an estimated 1 billion dollars a year to Al-Shabaab (Menkhaus, Citation2004). The prevailing divisive political environment in Kenya aids in the monumental diffusion of Al-Shabaab’s activities. The weak and predatory security forces of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) of Somalia, Footnote1 and a perception that the opposition has weak legitimacy (although a representative government, the TFG had, in 2004, been created in Kenya), both aid Al-Shabaab’s recruitment efforts – doing so with great alacrity. Historically, for instance, the 2007–8 period saw a great influx of foreign fighters whose main motivation was to oppose the occupation.

Third and final proposition is statehood. In Max Weber’s definition of what constitutes a state, the relationship between coercion and territory are key (Weber, Citation1970). However, the mere use of physical force within a territory does not alone adequately define what a state is. Other elements defining what constitutes a state are having a permanent population, a government, and the capacity to enter into relations with other states. The most important aspect of statehood, however, is the capacity of the state to control its borders. The lack of this control creates conditions ideal for the diffusion of terrorist groups or the formation of what Taylor (Citation2016, 7) calls ‘quasi-independent fiefdoms’. Mikulas Fabry (Citation2008) memorably refers to such formations as statelets – entities created by the dissolution of a larger state. Risse and Stollenwerk (Citation2018) clarify statehood based on the capacity of a government to have control over its territory. It is notable that the loss of legitimacy and authority over the population and space leads to the formation of an ungoverned space.

Therefore, ungoverned spaces are characterized by (1) the absence of ownership or control, and (2) the absence of state institutions (Sobrino et al., Citation2016). Invisibility or remoteness is also a key ingredient of ungoverned areas that enable terrorist groups to thrive. Ethnic homogeneity can make it difficult for the terrorists to stand out to observers, and enable them to blend easily into the general population. This is true for Al-Shabaab which remains a ‘tough nut to crack’, because its members easily sublimate into the general population whenever they are targeted in combat operations. Additionally, apart from the conceptual framework which facilitates the understanding of the concept of ungoverned spaces, the behaviours of terrorist groups must also be explained. To that end, this article utilises the relative deprivation framework to explain the evolution of Al-Shabaab and how the group ‘exports’ its terror activities from ungoverned spaces in Somalia into Kenya. This theoretical clarification uses the inkblot logic of diffusion to explain how ideas spread across territories in the Horn of Africa.

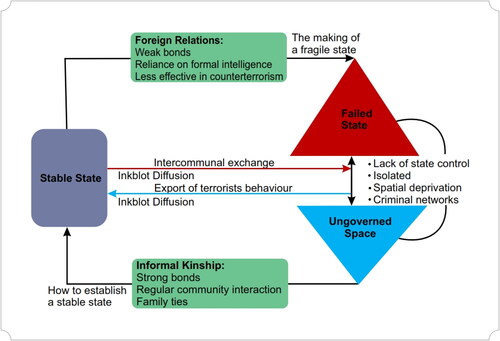

Based on the three propositions above, this article argues that the spread of Al-Shabaab terrorist ideas is likened to the spatial properties of an ‘inkblot’ as it spreads. In this article, the Rorschach Inkblot phenomenon is defined as a game-like activity that allows researchers to discover thinking patterns and the extent to which certain personality and thought processes spread across a geographical space (McGrath, Citation2008). Although the technique has been used by psychiatrists and psychologists as a tool for measuring personalities (Mondal & Kumar, Citation2021), it can also be utilised by social scientists to map out a group’s dynamics, especially, when studying social behaviour such as the recruitment and mobilization of terror-related activities across territories. Like the diffusion of ink on blank paper, terrorists’ activities in the context of ungoverned space use existing kinship networks to ‘export’ terror-like behaviour. Spatial deprivation (SD) also plays a key role in facilitating or preventing the growth and spread of terrorist activities across borders. Given the wider conception of relative deprivation which encompasses economic and political issues, it may not be an ideal framework to offer explanations for the formation of a regional network by a terrorist group, bred in ungoverned spaces. Rather, in this article I will build and utilize the notion of spatial deprivation as a model theoretical configuration to explain the connections and the push factors that enable terrorist activities to diffuse across borders from ungoverned spaces in Somalia into to Kenya as illustrated in .

Figure 1. Spatial relations between a fragile state and a stable state in the context of ungoverned spaces.

above is an illustration of why the Al-Shabaab group is one of the reasons that the country of Somalia is ranked as a failed state (Fund for Peace, Citation2018). The country has been described as one with weak state authority and a lack of functional/basic law and order (Menkhaus Citation2014). While there has been a general belief that Somali clans were acephalous (lacking headship) during the precolonial period (Menkhaus, Citation2012), there is a contention that they were indeed highly centralized bifurcated states that thrived as independent states based on clan kinship. In line with the theoretical framework in this article, the survival of clan formation is a strong indication of a state’s failure to exert control resulting in the growth of ungoverned territories. In the same vein, the regime of Siad Bare failed to initiate a nation-building exercise; rather, he continued to thrive on clan power politics. As a result, power was exercised through clan territorialisation, making Somalia operate in a more power-diffuse way in the absence of a nation-state.

As a consequence of this territorial dishonesty, Al-Shabaab exploited this incomplete governance space – a space where the state is unwilling to exercise authority in certain areas. Indeed, the group’s administrative structures are highly decentralized, taking into account the interests of various clan states. When the Somali state collapsed in January 1991, the resultant chaos brought AIAI (Al-itihaad al-Islamiya) to the centre of Somali society and gave them influence. Its first rallying call implored a society governed by Sharia law, resulting in relative peace in its territories. This early success incorrigibly endeared the people to fundamentalist groups. But, as the next section reveals, the evolution and the diffusion of Al-Shabaab is a complex phenomenon that goes beyond state fragility.

The three typologies of ungoverned spaces

Before we examine the historical development of the Al-Shabaab in Somalia, it is crucial to understand the various types of ungoverned spaces associated with state fragility. Somalia is considered fragile state based on factors such as the unavailability or the extremely poor delivery of public services; state structures that lack political goodwill; and the lack of capacity to provide the basic functions needed for poverty reduction and for the development and safeguarding of the security and human rights of its population (George, Citation2016). In a 2008 report, the RAND Corporation characterizes ungoverned spaces as being a key defining parameter of fragile states. The convergence between state fragility and ungoverned spaces is defined by the presence or absence of effective governance structures.

There are three typologies of ungoverned spaces: contestations, incomplete governance, and capability.

Contestations occur where a group contests the legitimacy of the government’s rule, instead pledging loyalty to an insurgent movement or to a tribe, clan, or other identity group that competes with the state for control. The various perspectives on formation of Al-Shabaab terrorist group point to a contested governance space. Some scholars observe that it is a remnant of Al-ittihaad al Islamiyah (Anderson & McKnight, Citation2015). Al-ittihaad al Islamiyah’s fundamental objective was to topple the Siad Barre regime and to craft an Islamic state that would unite all the Somali-speaking peoples from Kenya, Djibouti, and Ethiopia (Gartenstein-Ross Citation2009). Similarly, Menkhaus argues that after Somalia’s 1977 invasion of Ethiopia, the Somali state became like a house built on sand, as many radical groups contested its legitimacy. Indeed, President Siad Bare concentrated on survival tactics, mainly holding on to power through playing off opponents by using the aid that Somalia received during the cold war. The state’s fragility – and, hence, the evolution of contested governance space – seems to have preceded extremist organizations, as they began in the 1960s when radical Salafi and Wahhabi Islam were initiated into Somalia.

Initially, Somalis had been predominantly Sufis, who typically hold moderate views (Cannon, Citation2016). Somali Wahhabi and Salafi groups’ continued interaction with the outside world (Afghanistan) was made possible due to failed statehood in Somalia. The lack of border control and enforcement arrangements created the opportunity for extremist groups to move freely to the outside world – an opportunity they took advantage of. The political environment in Afghanistan became unconducive to the operation of the Somali Wahhabi and Salafi groups. Hence, upon returning back to Somalia, these groups aligned with the radical views of Abdulla Azam, who was a proponent of pan-Islamism. Furthermore, having plotted how to form a fundamentalist organization, they succeeded by becoming leaders of Al-Shabaab. By the year 2000, the youthful members of the AIAI group transformed into Al-Shabaab and enlisted the ICU (Islamic Courts Union) as its youth militia. It is, therefore, plausible to argue that Somalia’s failed statehood has indeed contributed not only to the terrorist group’s initial formation, but also to its continued diffusion into neighbouring states.

Incomplete governance is where the state lacks the capacity and resources to exert control over its population and space. This ‘lameness’ of the state can result in criminal syndicates, tribal groupings, or religious groupings filling the resultant territorial vacuum. When triaging limited resources in a way deliberately designed to favor its most likely supporters, a state – in a blatant abdication of proper governance – may callously refuse to provide basic infrastructure and other public goods and services in some proscribed regions on the basis of ethnic, tribal, or political biases.

The first and second typologies characterize most of the insurgency and terrorist groups in Africa. Organized groups exploiting the ungoverned spaces may take different forms – forms such as Marxist, separatist or Islamist. In the Horn of Africa, for instance, the Al-Shabaab terrorist group has been advancing its agenda as an Islamist group adhering to religious ideology. However, it is important to specify that the activities of Al-Shabaab go beyond its Islamic ideology. Its goal is to establish a caliphate to control the entire country. Hence, the discussion in this section – and indeed, in the entire article – will mainly reference the first two typologies (contested governance and incomplete governance).

There are arguments that Al-Shabaab is a recent phenomenon, having originated in 2005 when 30 extremists formed a movement that envisioned unifying all Islamic radicals, creating an Islamic state, and perpetuating jihad in the region (Jones et al., Citation2016). Despite the varied historical accounts, the common denominators here remain incomplete governance and contested space. In fact, the group continued to receive financial support from ICU and held 9 of the 97 seats that made the Shura council. As explanatory confirmation of the validity of its formative contestation of governance space, Al-Shabaab and ICU seized the port of Kismayu in September 2006 and went on to make the port financially stable (Hansen, Citation2013). From 1996 to 2000, Somalia’s poor internal governance hastened the formation of Al-Shabaab. First, AIAI was weakened by Ethiopia’s incursions after decrying its involvement with Ogaden rebels. Second, internal feuds amongst Islamic fundamentalist leadership of AIAI weakened it even further (Mohamed, Citation2010).

Capability The final typology of ungoverned space is capability. In Somalia, the states as well as various coalitions of warlords all collapsed, thus reducing their capability to control territories. Consequently, the resultant power vacuum was filled by varied courts, which adjudicated communal feuds. They later merged to form the radical ICU, which took Mogadishu in 2006. Meanwhile, the future leaders of Al-Shabaab travelled out of the country to receive training on how to wage jihad and form an Islamic state. For example, Farah Ayro went to Afghanistan, where he was hosted and trained by the Taliban regime. ICU ideology aimed to eliminate clan allegiance and galvanize the state under Sharia law, but instead inherited the rhetoric of Siad Barre on Somali state-building – thereby embracing clannism. The incomplete governance spaces in Somali accelerated the fragility of the country, and made it easily overrun by Islamic militias.

It also creates an environment in which promising contenders for legitimacy within a radicalized climate ultimately become too radical for neighbouring countries to work with. For instance, the 2000 talks in Djibouti produced a Transitional National Government in Somalia (TNG). However, the weak regime failed to receive regional support amidst fears that it had affiliations with al-Qaeda. The August 1998 attacks on the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania had both been linked to the activities of the new leaders of the Somali government. Consequently, the regional framework under the auspices of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) started a process to replace it.

How did the Al-Shabaab terror group evolve in the Horn of Africa?

Scholars who study the Horn of Africa and political Islam have attributed the terror proliferation in the Horn to several developments, including, the sprung of Sharia courts, fragility of Somalia, the growth of al-lttihad cells and development of secular factions (Tadesse, Citation2023; Also see Shinn, Citation2004; Solomon Citation2015; Menkhaus, Citation2002, Citation2005, Citation2014). All these combined, according to Ken Menkhaus (Middle East Policy Council- https://mepc.org/experts/ken-menkhaus), have facilitated the growth of collaborative networks between the Somali based Islamists and non-Somali groups such as Al Qaeda. The Al-Shabaab’s spread beyond Somali territory demonstrates how a localised conflict transforms into a regional or a global phenomenon requiring a collective security approach. Studies have pointed the spread of Al-Shabaab terrorist activities within the regional kinship networks through Kenya and Ethiopia, where the Somalia minority are perceived as weak.Footnote2 This territorial and kinship intercourse between Somalia and neighbouring states has compelled Kenya, Ethiopia, and great powers, including the US to enforce the global collective security approach against Al-Shabaab. But, how did the Al-Shabaab group evolve into a regional and international threat?

Before delving into the ‘diffusionary’ network nature of the Al-Shabaab terror group, this section provides an overview of how the domestic, regional and international forces influenced its evolution. First, since the reign of president Mohamed Siad Barre (1969–1991), Somalia remains a failed state with minimal authority and institutional discordance (The Fund for Peace, Citation2022). The effect of state failure is that various armed groups in Somalia could function by establishing economic base to the outside world through the porous seaports. Physical border porosity is an indicator of ungoverned spaces that create fertile grounds for the Al-Shabaab to thrive into the most powerful insurgency group with significant control of the country and a threat to regional and global security (The Fund for Peace, Citation2022). Secondly, the development of groups such as Al- Ittihaad al Islamiyah (AIAI) seem to have paved ways for the emergence of Al-Shabaab (Kruber & Carver, Citation2023). Although some scholars (Gartenstein-Ross Citation2009), have traced the formation of AIAI to the toppling of the Siad Barre regime in 1983, the common denominator here was the crafting of an Islamic state that would unite all the Somali speaking people in the Horn of Africa (Kenya, Djibouti, and Ethiopia). It is therefore plausible to argue that the extremist group preceded state collapse in Somalia. The collapse of the Somali state in 1991 increased the influence of AIAI in the country’s political order under sharia law. Interestingly, Sharia law ushered in relative peace in most parts of the country, albeit short-lived. The Somali youth who participated in the Afghanistan liberation war became influential in the AIAI. Some of the youth, such as Aden Ayro and Mukhtar Robow, maintained their networks with the remnants of the Afghan mujaheden, eventually becoming the face of al-Shabaab’s terror activities in the neighbouring countries such as Kenya (Williams, Citation2014).

The other phase of events that led to the evolution of Al-Shabaab in the Horn was the episodes of international intervention. The interventions that took place between 1992 to 1995, were aimed at establishing peace and stability in Somalia. The rejection of international intervention, mainly led by United Nations Operations in Somalia I (UNOSOM 1), United Taskforce (UNITAF) and UNISON II, seem to have fuelled extremism. As a response to this backlash on the so-called international intervention, the US intensified kinetic diplomacy. However, this elicited the question of whose interest was the kinetic diplomacy in Somali for? This followed a military offensive from the Khartoum based Al-Qaeda. Consequently, Osama bin Laden established networks in Kenya to facilitate resistance against US forces in the Horn (Malito, Citation2015). The final episode was marked by intractable domestic political wrangles and clandestine factions based on clan structures. No one describes the politics of clannism in Somalia than Ken Menkhaus in his 1997 article on foreign assistance:

An increasingly narrow set of clan interests drove political calculations, corruption grew rampant, and the ruling clique systematically de-institutionalized the state, rendering the large civil service little more than a bloated bureaucracy with little to do but collect very mod- est monthly paychecks and engage in ‘project hopping’ with aid agencies to make ends meet. Decision-making on virtually all matters of state was monopolized by a small circle around Barre, while ministerial positions were frequently rotated to prevent potential rivals from establishing a power base or demonstrating competence (Menkhaus, Citation1997).

Ethiopian incursion into Somalia was mainly driven by the involvement of AIAI with the Ogaden rebels, who were threatening the political stability of the former. The evolution of feuds amongst Islamic fundamentalists within Somalia created deeper cracks in the AIAI (Hansen & Gaas 2011 [2012]). As a result, the warlord coalitions collapsed further degrading the capacity of AIAI to control territories. Lack of control created a power vacuum. In 2006, the radical ICU forcefully took over Mogadishu, which made Somalia a key target of the global war on terror and the application of collective security measures by regional and external powers. Kenya’s motive to wage war against the Al-Shabaab remains inclusive. Some scholars have advanced the claim that the country’s motive was to protect its economic interest that was increasingly becoming undermined by attacks on foreign tourists (Buigut, Citation2018). However, researchers have given explanations on how a country becomes prone to terrorists activities. Such factors include: (1) inability of a country to inhibit terror activities (Crenshaw, Citation1981) if the territorial integratory of a state is compromised (Mogire & Agade, Citation2011); and (3) institutional weaknesses- fragile states can be a breeding ground for terror cells (Menkhaus, Citation2003). Although the institutional weakness thesis has been refuted by ‘root cause’ theorists, who argue that weak states with relatively functional economic systems can also experience terrorism (Newman (Citation2006; Also see Tikuisis, Citation2009). What most scholars content in the descending literature is that states with relatively strong economies such as Kenya in the neighborhood of ungoverned spaces (Somalia) is as much prone to terrorists’ activities. This is an important pointer to the current study.

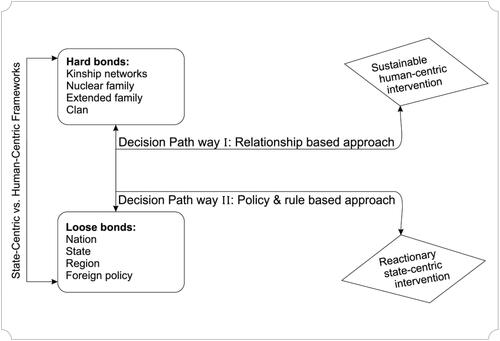

Other factors elevating Kenya’s vulnerability to Al-Shabaab attacks

The triggers for Al-Shabaab’s sustained attacks on Kenyan soil goes beyond the spatial deprivation (SD) explanation. Kenyan society sometimes lacks the kind of fervent patriotism that can be found among her neighbours such as Tanzania; and the idea of what constitutes being ‘Kenyan’ is, at times, a fluid construct (Malipula, Citation2014). Whereas the SD theoretical framework explains, to a large extent, the ‘inkblot’ network of terrorist cells in Kenya, there are other underlying causes for the growth of that network. For instance, Kenya’s high levels of bureaucratization coupled with streamlined infrastructure and ordered societies, provide anonymity to individuals who build successful terrorist cells. This adequately explains the presence of Al-Shabaab in the capital city, Nairobi. This scenario sharply contrasts with the environment in Somalia where the terrorist group originates from. Somalia has deep intricate inter-clan connections that dictate socio-political arrangements; hence, it makes outsiders easily detected or singled out. This portends danger to strangers if they don’t get local protection. However, even in situations where foreigners get local support, deep-seated kinship ties would limit their influence. Indeed, the strength of ‘hard bonds’ (nuclear family relations extended family, clannism, and ethnic affiliation) transcends that of ‘loose bonds’ (interstate relations, foreign policy, and regional security arrangements), as illustrated in . Therefore, counter-terrorism measures must prioritize the hard bonds in a bottom-top approach.

Figure 2. Proposed decision-making pathway model for framing counter-terrorism measures among transnational kinship societies.

above clearly illustrates the implications of each one of the decision pathways in tackling transnational terror activities leading to either (a) relationship-based, long-term sustainable interventions, or (b) state-centric approaches characterised by short-term, ‘knee-jerk’ reactions resulting in only temporary interventions with unsustainable outcomes. Al-Shabaab’s infiltration of Kenya’s northeastern, Somali-speaking (kinship affiliation) region remains the key factor in accelerating the diffusion of terror groups across borders. Al-Shabaab is said to be directly benefitting from Somali diaspora remittances through Kenya and Somali local businesses to finance their activities. With global remittances to Somalia averaging anywhere from USD $500 million go USD $1 billion, Al-Shabaab has managed to recruit and train youth in Kenya, making its operations more discreet and more difficult to detect. Regarding Al-Shabaab’s capitalization of kinship network ties to organize lethal attacks on Kenyan soil, a recent report on Kenya’s decade-long military incursion into Somalia had this say:

The profiling and arbitrary detentions, harassment, extortion, and even forcible relocation and expulsion, contributed to the alienation and grievances that provide rich fodder for radicalization and recruitment. Rather than attract adherents through ideology, al-Shabaab capitalized on Kenya’s response and sought to identify with the disaffected communities, mainly at the coast and in north-eastern Kenya, in the process morphing from a distant threat that could be contained in Somalia to one that is now no longer easily identifiable. (Shahow, Citation2022)

There is a clear logic to this concentration of resources within extended families and sub-clans, reflecting historical processes of migration and a continuous process whereby families are likely to focus their financial support on enabling relatives to migrate. In some cases, this is enabled by official family reunification programmes in host countries[….] but it also takes place through more informal channels. This process of migration[……] based livelihood change is understood in [terms of] resilience and vulnerability. It is a process] of social transformation, which takes place over extended periods of time.

Although state fragility, as explained through the SD, makes it easy for terrorist networks to thrive in Kenya, the state of fragility alone would not result in the transnational operations of the group. Other factors like a feeling of deprivation and the ability to appropriate the economic and logistical advantages offered by Kenyan society have made Al-Shabaab prominent in the country. Kenya’s key partners in the Global War on Terror (GTW) – i.e. France, Israel, UK, and the US – have spent significant sums on equipment and on building up the county’s capacity to thwart terrorism. The country’s security partners have aimed to equip her to smash terrorist cells on her soil and to secure western interests in the country. Moreover, these external initiatives have been reinforced by robust internal moves to enhance the capacity of counter-terrorism forces. There has been the creation of new anti-terror institutions such as the Anti-Terrorism Police Unit (ATPU), the Joint Terrorist Task Force (JTF), and the National Counterterrorism Centre (NCTC). Responses to terror attacks have been appalling. This can be accounted for by the elitists’ interests in the security forces – interests which override national security priorities; coupled with the politicization and outsourcing of the security sector (US Department of State, Citation2014).

In many of the incidences of combat operations against Al-Shabaab attacks, there has been weak coordination from the security apparatus, and various police divisions often act independently. There has also been a hiatus in command as various police divisions jostled over who should take command of the response. Astonishingly, for instance, in the Garissa attack, despite the presence of KDF soldiers who cordoned off the area, no one attempted to confront the gunmen who were shooting students in the halls of the residence. The thinking was that special forces trained to combat terrorist attacks (RECCE) would be best suited to handle the situation. But the elite combat team took a full 10 hours to arrive (United Nations Security Council [UNSC] Citation2014). Al-Shabaab was able to achieve its objectives, not because of a lack of intelligence and requisite personnel among its opposition, but because of poor communication and coordination. Moreover, Kenya security agencies have detailed emergency response measures that should be taken in the case of an attack – but such response plans are useless if they are not used. Therefore, these systemic failures make Al-Shabaab successful in their operations, with their attacks’ high casualty counts garnering headlines among the world’s media.

The inkblot diffusion theory and Kenya’s national security architecture

In this section, I utilize ‘inkblot’ diffusion logic to answer the question: What implications might the dynamical spread and penetration of the Al-Shabaab terror group have on the Kenya’s national security architecture? The phenomenon of ink diffusion and its industrial application has been studied through scientific experiments (Mirón-Mérida et al., Citation2021). Two properties are critical to the process of diffusion- dynamical spreading and penetration (Asai et al., Citation1993). Although the process of material diffusion is different from the spread of ideas and ideologies in a social setting, it can be likened to the behavior of extremist groups such as Al-Shabaab across borders. The notion of ‘spreading’ and ‘penetration’ as relates to the physical characterization of diffusion can be modified to analyze the social kinship networks and how such networks contribute to the spread of terror ideologies, weapons and fear. Closer to the study of social phenomenon is the pioneering work of Everett Rogers and his colleagues on diffusion of innovations (Rogers, Citation1962; Thoma & Rogers, Citation1995). Just like innovative ideas spread across geographical borders and population, the spread of Al—Shabaab from ungoverned spaces in Somalia to Kenya can pose a region-wide security threat.

To begin with, there are several reasons why, and several ways how, the ungoverned space is responsible for the growth and survival of Al-Shabaab terrorist group in Somalia. This phenomenon has evolved at the behest of the country’s civil war and poor governance, leaving the country in an anarchical state. The country’s judiciary system was destroyed, and the state left unwilling to provide its citizens with essential services such as security as well as adequate food, clean water, health care, and education. As a result, it leaders and militant groups arose that dedicated to governing themselves using all means deemed necessary, including inducing fear. This observation is in line with this article’s theoretical framework – the idea that state failure and, hence, the formation of grievances, is likely to attract terrorist organizations and other organized networks (Piazza, Citation2008). This is because failed states are vulnerable and are also prone to both relative deprivation (RD) and spatial deprivation (SD). Similarly, Lind et al. argue that a fragile and failed state like Somalia suits terrorist organizations in that the fragile state’s outward manifestation of sovereignty limits outside intervention (Lind et al., Citation2015). However, the controversial question of whether or not the formation and networking of such groups implicates neighboring states in complicity due to their purportedly having unwittingly potentiated the growth of the network remains unresolved. Critiques of the KDF’s (Kenya Defense Force) intervention in Somalia put up a spirited argument that this security arrangement exposes Kenya to a myriad of terror attacks and security challenges.

The RD and SD theoretical frameworks provides the foundation of understanding the general evolution of threats emanating from acts of deprivation in a society replete with inequalities. However, to gain deeper understanding of the nexus between ungoverned spaces and spread of Al-Shabaab groups into spaces they perceive inhabited by enemies, we utilize the inkblot diffusion logic. In this article, the notion inkblot diffusion network is derived from Everett Rogers theory of diffusion of innovation- which concerns the spread of an idea, practices, objects or population in space and time (Lind et al., Citation2015; Rogers, Citation1962). Although Rogers’ theory was initially developed to gauge how fast and efficient an innovative idea would be adopted in the population, its usage has been wide and rich in disciplines such as sociology and anthropology. Roger’s arguments in socio-technical fields are also quite useful in understanding the regional spread of Al-Shabaab beyond the ungoverned spaces. Likewise, Roger’s propositions offer similarly useful, explanatory insight into the ‘inkblot’-like network of the terrorist group from its nucleus (the ungoverned space) to the periphery (the neighbouring state).

In this article the movement of Al-Shabaab terror group is likened to the flow of energy when ink is dropped on a blotted paper. Depending on the micro-topography of the paper, some parts of an inkblot flow faster than others – just as different kinds of resistance can impede or speed the spread of an ideology (or military force) into and through areas of potential conquest. In the case of inkblot diffusion into virgin territory (corrupting the paper and staining its heart black as it succumbs), micro-gradients in the paper such as downward-angled channels (potential avenues of spread) can increase the rate of change by welcomingly facilitating it (in the way Soviet-era revolutionaries welcomed Stalin with open arms – not knowing they would ultimately be purged). In the case of Al-Shabaab’s diffusion across borders, acceleration in the rate of diffusion is usually the result of influential members of the social system making the decision to radicalise new members. Their decision is subsequently communicated to others who then blithely follow their leader and speed his rise to prominence – not realizing they may be doing so to their own detriment. Targeted disruption of this chain of trust can be a key strategy of counterinsurgency operations.

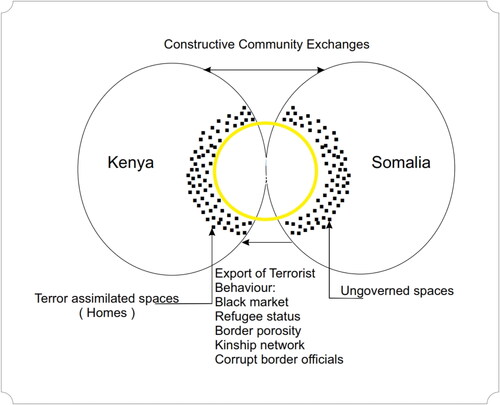

Dating from 2006, several factors facilitated the growth of Al-Shabaab as it metastasized beyond the ungoverned spaces in Somalia. First, it seized the opportunity to galvanize the local population around the hatred that they had towards the Christian invaders. Thus, it was able to near-effortlessly recruit and spread across the region, including in Kenya. Second, rather than engage in pitched conventional battles against the Ethiopian forces, it resorted to guerrilla campaigns against them, and later on waged asymmetric warfare on Kenyan soil. Third, they took the opportunity to depose the leaders of the ICU, who fled Somalia. Fourth is the social interaction among communities from both side of the border, creating what I coin ‘cross-border “homes”’ and ‘identities’, as illustrated in .

Figure 3. Formation of cross-border ‘homes’ and the export of terrorist activities.

illustrates how the Al-Shabaab group became more of a regional ‘outfit’. This is attributable in part due to their view of how to galvanize the Greater Somalia space in terms of their foreign policy. The withdrawal of Ethiopian forces in 2009 and their replacements with the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM) comprising of soldiers from Uganda and Burundi, gave Al-Shabaab reason to advance their cause beyond Somalia’s territory. It effectively fashioned itself as a Muslim liberator against Christian crusaders. For example, in October 2008, the group carried out attacks on the Ethiopian consulate and government offices – attacks which claimed many causalities. In 2009, it bombed the African Union peacekeeping mission in Mogadishu killing more than 20 people (Agbiboa, Citation2013). Moreover, in 2010, the group acknowledged carrying out attacks in Kampala that left more than 70 people (including US citizens) dead.

In 2010, the group declared war on Kenya because of Kenya’s support of the TFG, and began to carry out attacks with increased frequency. On 16 October 2011, Kenya invaded southern Somalia; and its forces were integrated into AMISOM in February 2012. The Elade attack on 15 January 2016, and the 2017 KDF camp attacks in Somalia, demonstrate that the military capabilities of the group and its acts of terror are still reminiscent of its peak days (Thomson Reuters Foundation, Citation2017). In both attacks, KDF camps were completely overrun, as hundreds of soldiers died and others fled. The following week, KDF announced its renewed attacks on the group’s positions, indicating that the KDF’s role in Somalia had completely metamorphosized from a conquering army to a reactionary peacekeeping force. From the foregoing discussion, the structural growth of Al-Shabaab as a consequence of the rejection of Sufism and the view that radical Islam offered better prospects for the Somali nation is one side of the picture. It is clear that decades of misrule and tribalism, endemic corruption, and the lack of nation-building initiatives are responsible for the formation of ungoverned spaces in Somalia, with the attendant dire consequences for Kenya’s national security architecture. It is on the basis of these developments that this article explores explanations (propositions) to the relationship between the diffusionary spread of Al-Shabaab from the epicentre- Somalia and the Kenya’s national security architecture.

The first proposition is that within the broader framework of spatial deprivation, the definition of ungoverned spaces transcends state failure or governmental absences to encompass (1) a primordial existence of ethnic and tribal hierarchies, with their embedded customs and laws; (2) land populated by traditional nomadic tribes; (3) criminals; and (4) religious authorities. Within this theoretical framing, although Kenya is not officially considered as being a failed state – and hence, the spatial absence of ungoverned spaces – the ‘inkblot’ effect of Al-Shabaab implicates the country’s national security architecture. It is therefore important to frame ungoverned space beyond its origin point – that is, beyond the nucleus of the failed state. On this point, there has been a contention that Kenya’s support for the Global War on Terror (GWT) negates the efforts that are made by the country’s counter-terrorism strategy. Kenya’s close ties with the State of Israel and the US make it susceptible to terror attacks.

This view has also been upheld by Kenya’s top government officials. For example, when the former minister of foreign affairs visited Israel, he reiterated that Kenya becomes a prized terror target not because it harbours ungoverned spaces, but due to its close ties with Israel and the US. Moreover, the former leader of the Kenya Council of Imams, Sheikh Ali Shee, warned against the government’s policy of supporting the US fight against terrorism. With the ‘fuzzy’ borders between the two countries, such a policy placed the country in the unenviable situation of receiving retaliatory blows meant for the Americans (Barkan & Cooke, Citation2001). Kenya’s unwavering support of the War on Terror simultaneously strengthens and undermines its own security – because on the one hand, doing so bolsters its defence and increases regional stability (protecting vulnerable populations); while on the other, it puts itself in the line of fire and fuels propagandistic recruitment claims that Kenya expressly apdproves of US imperialism (as framed in crusadist terms) (Anderson & McKnight, Citation2015).

Al-Shabaab’s attack in Nairobi on January 15th, 2019 – an attack that killed a dozen people, caused destruction to property, and injured hundreds of people – was done in retaliation to Kenya’s global war on terror and deep ties with Israel and America (The New York Times, Citation2019). The statements issued by Al-Shabaab confirming the responsibility for the attack claimed that the main reason for the attack was the US decision to confirm Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. As Anderson and McKnight asserted, Al-Shabaab seeks to advance its regional vision by adapting and reinventing itself. Faced with an imminent challenge from the Somali faction of ISIS (the Islamic State) which has declared war on Al-Shabaab, the latter seeks to adopt an international status by claiming to fight for the rights of Muslims not only in the Horn of Africa, but wherever they may be in the world. The significance of such a statement is twofold: firstly, to assert its ideological edge over ISIS in Somalia; and second, to please its rich donors from the Gulf states who are sympathetic to the Palestinian plight. To reach a wider audience and generate the much-needed publicity necessary to to rebrand itself, mobilize support, and appeal for more funds from international donors, Al-Shabaab launches its attacks in Kenya., Al-Shabaab is cognizant that many reputable international media houses base their correspondence from Nairobi because of the presence of a free and robust media there. Thus, launching more attacks in Kenya would propel it to the world stage while at the same time enabling it to stay relevant at home. Through such methods, Al-Shabaab remains popular in Kenya, attracting many youths who harbour grievances against the Kenyan government for the ever-increasing unemployment situation and find solitude in Al-Shabaab’s regional network.

The second proposition under the spatial derivational theoretical framework is that a country can be prone to terrorist activities if the state cannot or is not willing to inhibit terrorism. In other words, a country cannot foil terrorist activities if their security regime does not have the requisite capacity and the justice system is inefficient and incompetent (Crenshaw, Citation1981). The most plausible explanation for the continued terrorist attacks on Kenyan soil is due to institutional weaknesses (especially the laxity in immigration laws) that have been exploited by Al-Shabaab and her sympathisers (Carson, Citation2003). Although Kenya does not feature among the failed states, a combination of domestic structural weaknesses have embroiled the country into a haven and breeding ground for terror activities.

There are, however, some scholars who do not agree with the view that weak institutions are responsible for the evolution of terrorism. Newman cautions against the assumptions that a weak state would be ideal for terror groups to operate. He argues that even strong states do harbour terrorists as they appropriate to their advantage the economic and logistic avenues present. For instance, in the September 11, Al-Qaeda operatives operated freely in the US and Germany undetected (Newman, Citation2006, 483). The above structural school of thought contradicts the statehood thesis. It seems to promote the view that terrorist activities thrive in an environment of weak nationhood – that Al-Shabaab is likely to export their behaviour to Kenya if they get local support from opinion leaders such as clerics or sheiks. However, a majority of thinkers in this field seem to agree that terrorism is reinforced through weak states (Gould & Pate, Citation2016).

The Kenyan government enjoys legitimacy. However, deep corruption in state institutions, a reduced capacity to conduct border patrols, and support offered to militant groups by disaffected citizens are features that expose the country’s national security to the risks of terror attacks. Therefore, the weak states thesis as a function of SD seem to contribute to the export of terror activities from ungoverned spaces in Somalia to Kenya. Nonetheless, other underlying factors make Kenya a platform for Al-Shabaab-related activities and suggest that the weak state thesis alone is insufficient. There are weaker states than Kenya in the region, but terrorists can hardly operate there simply because of the way the society proudly upholds nationalism. At a later stage, this article argues that it is the configuration of the Kenyan society, coupled with a relatively prosperous economy in the regional context, that makes it a darling of Al-Shabaab.

The third and final proposition is that given western countries’ increasing lack of interest to intervene in terror activities in Africa (Mentan, Citation2017), there is an enormous pressure on regional powers like South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya to assume a dominant role in fighting terrorism (Solomon Citation2015). In other words, the African states are striving to address the spatial deprivation created by the global powers. Kenya is one among leading regional powers that have been in the forefront of fighting terrorism in the horn of Africa (Cannon, Citation2016). In 2011, due to continuous terrorist attacks, the Kenyan government resolved to intervene militarily in Somalia which it considered as being the heart of the Al-Shabaab terror group. However, from September 2013 to date, Kenya continues to be on the receiving end of Al-Shabaab attacks. Some of these attacks on Kenya have been devastating. These include the January 2016 attack on the KDF camp in El-Adde (located in Gedo, Somalia, the 2015 Garissa University attack, the 2014 Mandera attack, and the 2013 Westgate terror attack (Olsen, Citation2018). However, these threatsare less likely to substantially influence Kenya to withdraw troops from Somalia in the way that Black Hawk Down resulted in the US withdrawal. In any case, Operation Linda Nchi (Swahili for ‘Defend the Homeland’) that had begun in 2011, though having officially ended mid-2012, actually continues under the AMISOM umbrella. Al-Shabaab’s mutational behaviour, especially its diffusion across borders into neighboring communities, makes it difficult to erase the group using state-centric counterterrorism measures. As Negasa Debisa (Citation2021) succinctly puts it in his security-diplomacy approach to the question of terrorism in the Horn of Africa, there is no single profile of the problem – and (thus) no single solution to it. Indeed, to date, Kenya continues to face scattered threats of terror attacks.

Although, Kenya is not considered as being a fragile state, there are ‘pockets’ of peripheral extra-legal territories that experience minimal state presence and development. Such areas frown on being called Kenyan territory. Just as the whole idea of a single Somali nation can be questioned, some have argued that the country called Kenya exists without a nation. Consequently, Kenya has received challenges to its sovereignty from within. Such challenges have been posed by the Shiftas of Northern Kenya and MRCFootnote3 separatists from Mombasa. This suggests that Kenya is not an empirical statehood but rather a juridical sovereign (Engelbart, Citation2009). For example, the idea of the Kenyan state wanes as one moves away from the capital further north to the former northeastern province. Originally, the colonialists had used the area as a buffer zone against attacks from the Arabs and hostile tribes from Sudan. Consequently, they did little to introduce state structures, and their policy was not to disturb pre-colonial structures. However, after independence, this marginalization resulted in the need to belong to a more empirical state, and the inhabitants chose to join Somalia rather than to remain in Kenya. They even declared war on Kenya – a war which was brutally suppressed by the founding Kenyan president Jomo Kenyatta’s government in Nairobi (Bailey, Citation2009).

Since Kenya’s independence in 1963, the northeastern part of the country remained without infrastructural connections, with minimum to no presence of state machinery. The lack of state machinery or contestation of certain spaces, whether physical territories or non-physical spaces, coupled with the absence of effective state sovereignty and control, comprise of what political scientists have defined as being ‘ungoverned space’ (Menkhaus, Citation2016). One consequence of this territorial lawlessness is that it makes the diffusion of extremist groups into the neighbouring territory much easier. Erratic attacks along the Kenya-Somali territorial border poses threats to regional stability; there have been a number kidnapping incidents, together with trading in illicit goods. Al-Shabaab and other international terrorists spread insecurity from areas that are highly ungoverned to other regions, attacking civilians and undermining transport routes. Kenya’s border’s porosity occasioned by corruption and the lack of a unified ethnic sense of belonging, increases borders’ vulnerability to the cross-border diffusion of terror activities. As a result, Al-Shabaab attacks in these areas happens every month against the few instances of government machinery, communication installations, and those perceived as being ‘foreigners’. This is a combination of relative deprivation and spatial deprivation of the Somalis by the Kenyan state. The spatial deprivation phenomenon has particularly endeared the people of Somali origin to extremists to the point where they share information on the movements of non-Somali Christians to Al-Shabaab operatives who murder the Christians. There have been incidences where locals gather in the evenings to listen carefully to Al-Shabaab propaganda and religious rhetoric.

Conclusion

This article deployed inkblot diffusion logic to examine the dynamical spread and penetration of Al-Shabaab extremist group into neighbouring states through structural cracks such as black markets, refugee movements, border porosity, corruption among border officials, and kinship networks. The study shows that there is a likelihood of most of these factors reinforcing each other, and this article suggests ways in which these interconnections can frame counterterrorism (CT) strategies for stabilizing states. By framing CT scenarios as laid out in this article, researchers and policy actors can explore the extent to which the spatial diffusion of terror-related activities and behaviours is posing a threat to national security of Kenya and other states in the Horn of Africa. This suggests that, although inkblot diffusion logic can provide insight into the link between ungoverned spaces and the spatial distribution of certain behaviours and activities along kinship networks, this alone cannot fully explain most ideological, protracted guerilla warfare and elusiveness behaviours exhibited by the militant groups. For example, the tendency of Al-Shabaab toward carefully engaging in calculated behaviours deliberately designed to evoke Islamic empathy might not be facilitated either by the ungoverned spaces themselves or by other macro-facilitative factors such as border porosity. Rather, it is perhaps itself based on a very intuitive kinship connection.

The study finds a strong empirical support for a general association between the spread of terrorist groups through ungoverned spaces and increased security threats in Kenya in the years that followed the deployment of KDF to Somalia. In general, terrorist groups that grow and thrive in ungoverned spaces are rapidly spreading beyond these ill-governed territories; they are metastasizing into new spaces in which the state has had a relatively stable presence in the neighboring country Kenya. Due to existence of ill-governed territories in Somalia, the power and influence of Al-Shabaab has spread beyond the epicenter of terror activities and has found new spaces of operation in which to work (Mutanda, Citation2017). Indeed, since KDF’s incursion in Somalia in 2011, Al-Shabaab has conducted deadly attacks inside the Kenyan territory. This is worrisome, particularly because the freezing of borders and the ‘fuzzy’ territoriality disputes over the Kenya-Somalia border are factors which create weaker border control. Moreover, disaffected minorities exploit the vulnerabilities of porous borders to ‘export’ terrorist activities to the neighbouring country.

Accordingly, this article contributes to the growing literature on how terrorist groups spread their ideologies and weapons to areas they perceive inhabited by enemies. The literature is not devoid of this phenomenon, particularly in regard to their exploitation of global pandemics such as COVID-19 to reach their perceived enemies and the use of cyber space to spread their propaganda (Kruglanski et al., Citation2020; Also see Grobbelaar, Citation2023). This article is the first attempt to develop a methodological tool that provides the lens through which the spread and penetration of Al-Shabaab can be understood. In addition, while most studies have examined the historical evolution of terror groups, organizational structure, and formation of terror cells, (Dnes & Brownlow, Citation2017; Asal & Rethemeyer, Citation2008; also see Enders & Su, Citation2007), this research has endeavoured to examine the intervening effect of ungoverned spaces on the spread and intensity of terror groups. Basically, examination of the role of geographical space in the spread of terror groups. The triangular relationship between territorial sovereignty, one-sided violence, and statehood becomes particularly significant because of the problems posed by the fluid nature of the terrorist group with the ability to ‘export’ terror activities from ungoverned spaces to the neighbouring states. This relationship is complex. Hence, this study improves the conceptualization of counter-terrorism (CT) strategy by arguing that an effective CT strategy must contain an element of diffusion network. Ungoverned space acts as a facilitative force to the process of diffusion. However, the implication of terrorists’ activities outside the ‘epicentre’ is as corrosive as that at the ‘nuclei.’

Finally, the policy implication of the proposed theory of ‘inkblot diffusion’ is that the war on terror in Kenya cannot be won by simply focusing on remedying the ungoverned spaces in Somalia. As part of its efforts to tackle the Al-Shabaab terrorist group, Kenya’s national security architecture must be cognizant of the vulnerability of the local population who are already frustrated by the limitations of formal governance systems. Therefore, the purpose of effective sovereignty, territorial integrity, and nation building should be to manage the networks of terror groups. Ungoverned space is inevitable in fragile or failed states such as Somalia – but must this always lead to ripple effects within neighbouring states? This question forms the basis for further research on the relationship between enfeebled community institutions and spread of security threats from a failed state to relatively stable states.

Acknowledgements

I would like to sincerely thank Esther Ang’awa for taking the trouble of reading through the entire manuscript with a tooth-pick eye. Esther is an Advocate of the High Court of Kenya and a post-graduate fellow of the King’s College, London, UK.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Francis Onditi

Francis Onditi is Associate Professor of conflictology & Head of Department (HoD), School of International Relations and Diplomacy, Riara University, Nairobi, Kenya. An authority on the geography of African conflicts and their evolutionary nature, he is a distinguished research professor at the Institute for Intelligent Systems (IIS), University of Johannesburg, and was awarded the 2019 AISA Fellowship by South Africa’s Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). He was recently ranked among the World’s Top 2% scientists/researchers of the year 2022/2023/2024 listed by the Stanford University, USA. Having authored and edited 7 major volumes and over 100 articles and book chapters, in 2023, he was awarded the Erasmus Mundus Global teaching fellowship at Leipzig University, Germany.

Notes

1 TFG- Transitional Federal Government.

2 See Ken Mekhaus’ essay in the Middle East Policy Council. Available: https://mepc.org/experts/ken-menkhaus).

3 MRC - Mombasa Republican Council.

References

- Agbiboa, D. E. (2013). The ongoing campaign of terror in Nigeria: Boko Haram versus the state. Stability: International Journal of Security and Development, 2(3), 52. https://doi.org/10.5334/sta.cl

- Anderson, D. M., & McKnight, J. (2015). Understanding Al-Shabaab: Clan, Islam and insurgency in Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 9(3), 536–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2015.1082254

- Asai, A., Shioya, M., Hirasawa, S., & Okazaki, T. (1993). Impact of an ink drop on paper. Journal of Imaging Science and Technology, 37(1993), 205–207.

- Asal, V., & Rethemeyer, K. R. (2008). The nature of the beast: Organizational structures and the lethality of terrorist attacks. The Journal of Politics, 70(2), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608080419

- Bailey, C. E. (2009). Counterterrorism law and practice in East Africa Community. Brill Publishers.

- Bakken, V., & Rustad, S. (2018). Conflict trends in Africa, 1989–2017. Peace and Research Institute Oslo.

- Barkan, J. D., & Cooke, J. G. (2001). U.S. Policy towards Kenya in the Wake of September 11. can antiterrorist imperatives be reconciled with enduring U.S. Foreign Policy Goals? Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

- Bellamy, A. J. (2009). Responsibility to protect. Polity Press.

- Buigut, S. (2018). Effect of terrorism on demand for tourism in Kenya: A comparative analysis. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 18(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358415619670

- Cannon, B. J. (2016). Terrorists, Geopolitics and Kenya’s proposed border Wall with Somalia. Journal of Terrorism Research, 7(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.15664/jtr.1235

- Carson, J. (2003). What we all can do to fight and defeat terrorism. Nation. June 1.

- Clarke, W. S., & Herbst, J. (1997). Learning from Somalia: The lessons of armed humanitarian intervention. Westview Press.

- Clunan, A. L., & Trinkunas, H. A. (2010). Ungoverned spaces: Alternatives to state authority in an era of softened sovereignty (p. 17). Stanford University Press.

- Crenshaw, M. (1981). The causes of terrorism. Comparative Politics, 13(4), 379–399. https://doi.org/10.2307/421717

- Cronin, P. M. (2009). Global Strategic Assessment 2009: America’s security role in a changing world (p. 101). National Defense Press.

- Dearing, J., & Cox, J. (2017). Diffusion of innovation theory, principles and practice. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 37(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1104

- Debisa, N. G. (2021). Security diplomacy as a response to Horn of Africa’s security complex: Ethio-US partnership against al-Shabaab. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1893423. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1893423

- Diggins, C. (2011). Ungoverned space, fragile states, and global threats: Deconstructing linkages. Inquiries Journal, 3(03), PG. 1/1.

- Dnes, A. W., & Brownlow, G. (2017). The formation of terrorist groups: An analysis of Irish republican organisations. Journal of Institution Economics, 13(3), 699–723.

- Enders, W., & Su, X. (2007). Rational terrorists and optimal network structures. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51(1), 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002706296155

- Engelbart, P. (2009). Africa: Unity, sovereignty, and sorrow. Lynne Rienner.

- Fabry, M. (2008). Sessession and state recognition in international relations. In A. Pavkovic & P. Radan (Eds.), On the way to statehood. Secession and globalization (pp. 51–66). Ashgate.

- Fund for Peace. (2018). Failed states index. The Fund for Peace. http://ffp.statesindex.org.

- Gamson, W. (1975). The strategy of social protest. Dorsey Press.

- Gartenstein-Ross, D. (2009). The strategic challenge of Somalia’s Al-Shabaab: Dimensions of Jihad. Middle East Quarterly, 16(4), 25.

- Gartenstein-Ross, D. (2009). The strategic challenge of Somalia’s Al-Shabaab dimensions of Jihad. Middle East Quarterly, Fall. https://www.meforum.org/2486/somalia-al-shabaab-strategic-challenge

- George, J. (2016). State fragility and transnational terrorism: An emprical analysis. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(3), 471–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002716660587

- Gould, L. A., & Pate, M. (2016). State fragility around the world: Fractured justice and fierce reprisal. Routledge.

- Grobbelaar, A. (2023). Media and terrorism in Africa: Al-Shabaab’s evolution from militant group to media Mogul. Insight on Africa, 15(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/09750878221114375

- Hansen, S. J. (2013). Al-Shabaab in Somalia: The history and ideology of a militant Islamist group, 2005–2012. C. Hurst.

- Hansen, S. J., & Gaas, M. H. (2011 [2012]). Kapitel 12 Harakat Al-Shabaab and Somali’s current state of affairs. Jahrbuch Terrorismus, 5, 279–293.

- Hassner, R. E. (2003). To halve and to hold: Conflict over sacred space and the problem of indivisibility. Security Studies, 12(4), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636410390447617

- Hindess, B. (2005). Politics as government: Michael Faucault’s analysis of political reason. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 30(4), 389–413. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40645215. https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540503000401

- Jones, S. G., Liepman, A. M., & Chandler, N. (2016). Counterterrorism and counterinsurgency in Somalia: Assessing the campaign against Al-Shabaab. RAND Corporation.

- Krasner, S. D. (2001). Abiding sovereignty. International Political Science Review, 22(3), 229–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512101223002

- Kruber, S., & Carver, S. (2023). Insurgent group cohesion and the malleability of ‘foreignness’: Al-Shabaab’s relationship with foreign fighters. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 46(10), 1894–1911. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2021.1889091