Abstract

This study examined how online hate discourses following the attempts of regional parish administration in Oromia and Tigray regions have deteriorated peace, unity and harmony among Tewahedo Church (EOTC) Christians. The growth of hate speech, which is connected to religious undertones and also contributed to racial and political differences has tamped down the new digital platform. To examine users’ comments gathered from the Facebook pages and YouTube channels of EOTC TV, Oromia and Nations Nationality Synod (ONNS) and Omega TV, the study used a qualitative conceptual content analysis research design. Using the social media analysis, it was discovered that there is a substantial occurrence of hate speech on social media that poses a threat to peace and degrades unity and harmony within the EOTC. Hatred tendencies going towards and going against the three organisations’ social media networks were identified. Neutral comments were also dealt with as they were important in strengthening unity and harmony within the church. Most of the hate speeches were amplifying existing disagreements and divisions within the EOTC. The results of the study indicate that different factions or groups used some social media platforms to spread their narratives, demonise opposing viewpoints, and further polarise the community. The religious fathers need to address the concerns about the schism and its potential consequences on the EOTC’s reputation, followers, and religious practices to minimise the spread of hate speech.

Social media is primarily influencing and defining public discourses and human communications among global citizens in our modern day. It is impossible to separate social media from aspects of our daily lives like politics, religion, ethnicity, internet marketing, and academic platforms (Adamu, Citation2020). Social media networking sites are evolving into the most alternative platforms for youth, activists, and politicians to express themselves freely and to mobilise around issues of human rights, corruption, and social, political, and economic injustices under political and religious hegemonies (Adamu, Citation2020). Social media posts unquestionably affects people’s lives in both good and bad ways.

To maintain peace and harmony among religious people from deteriorating, these posts, comments, blogs, and shares must be properly addressed (Daba, Citation2023). It is less well-recognised that many religious individuals and communities are moving on a different path (Alger, Citation2002). Social media can be a platform for productive discussions about these concerns, but it can also be used to disseminate rumours and intolerance. Therefore, it is crucial to make sure that dialogues are productive to uphold peace and togetherness. Religion has always had a better potential to be used as a tool for peace than for conflict, at least intellectually speaking. Religion is re-emerging as a force that is acknowledged as a significant component of modern social connections in the process of establishing peace (Haynes, Citation2020). Religion also plays an important role in shaping of public and private spheres. This comprises promoting harmony, peace-making, and conflict resolution (Daba, Citation2023). While religious institutions and actors do play a significant role in promoting peace, they underutilise their resources when it comes to preventing and addressing violent extremism (Daba, Citation2023). Social media platforms become sites that enable online users to easily interact with others who share their views or values about religious institutions (Al Serhan & Elareshi, Citation2019).

The foundations of peace and harmony in society are often derived from religious institutions, which instil values like empathy, nonviolence, compassion, and truthfulness (Belachew & Midakso, Citation2023). These values can help people understand each other’s perspectives and points of view, and resolve conflicts peacefully. Such values shape individuals and communities, creating a more justice, peaceful and a more harmonious society that is better equipped to tackle problems, build trust, and create a more equitable and sustainable world. Moreover, religion plays an important role in developing critical values related to peace, such as embracing and even loving strangers, avoiding insults and maltreatment of others, including disbelievers, suppressing egos and acquisitiveness, forgiveness, and humility (Gopin, Citation2000). Keeping their followers from telling lies and refraining from evil and wrongdoings is another role religious institutions can play in fostering truth, justice, and mercy over deception and division (Devine, Citation2017).

Literature review

Historical context of the study

The recent complaints around church administration issues in the EOTC were not the first of its kind in the church. Evidence indicated that the EOTC had been claiming independence from the Coptic Church of Egypt beginning from 1924 to 1951 (Ancel, Citation2011). According to Ancel (Citation2011), the Ethiopian royal power had been trying to persuade the Coptic Church to permit Ethiopian monks to be consecrated as Ethiopian archbishops and bishops. After a longer period, Baselyos was eventually consecrated as the first Ethiopian archbishop in 1951. This was a major step towards the recognition of the Ethiopian church as a legitimate denomination in the Christian world. The new archbishop quickly gained the support of Emperor Haile Selassie and the people, and the church flourished under his leadership (Ancel & Ficquet, Citation2016). Baselyos continued to encourage the growth of the church and to improve relations with other denominations. His tenure as archbishop spanned three decades and he was highly respected by both the church and the people of Ethiopia which left him behind a lasting legacy of faith and service to his people and became the first patriarch of Ethiopia in 1959 (Ancel, Citation2011). According to Ancel (Citation2011), he was a beloved leader who brought harmony and understanding to the region and was the major contributor to the growth of the church in Ethiopia. Baselyos was an inspiration to many and was a leader of great faith (Ancel, Citation2011). Thus, a unilateral declaration of independence from Egypt was made to ignite the burgeoning religious nationalism of Ethiopia in opposition to Alexandrian dominance and simultaneously separate it from Egypt and Jerusalem, where British influence was strong and where many Ethiopian refugees had gathered (Larebo, Citation1988).

Hence, Ethiopia’s Patriarchate gained control of the entire ecclesiastical scene in 1959 when a centralised ecclesiastical administration was created (Ancel, Citation2011). This made the Patriarchate the highest governing body of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church which created a unified liturgy and centralised rules and regulations. This unified system of governance allowed the Church to maintain a strong presence in Ethiopia which also enabled the Church to continue to provide spiritual guidance to the people of Ethiopia. During the reign of Haile Selassie (1930–1974), the centralisation trend had its major opening. The royal ideology had previously asserted an almighty authority over the Church before this process. It was possible to view the ecclesiastical system more as a dispersed rather than a centralised one since it was so incredibly intricate. Every element of the religious society had to remain within the jurisdictional bounds established by agreement or custom. To build a consolidated ecclesiastical administration, Haile Selassie’s acts and judgments about the EOTC were nonetheless (Ancel, Citation2011).

The church’s legal autonomy, to be led by its Ethiopian patriarchate, in the twentieth century was its most noteworthy and long-awaited accomplishment during this time (Ancel, Citation2011; Asale, Citation2016; Larebo, Citation1988). Since it had always been subject to the Coptic Church, the Church technically had never had the right to hold its important council before this time (Ancel, Citation2011; Ancel & Ficquet, Citation2016). The Church, however, managed to uphold its distinctive collection of Scriptures and to carry on its distinctive traditions despite its reliance and isolation (Asale, Citation2016). This enabled the church to maintain a unique identity and spiritual focus. As a result, the church was able to remain strong and resilient during difficult times. However, various cultural and linguistic backgrounds of the people of Ethiopia dominantly the Oromos and Tigrayans began to question the administrative discrepancies in the EOTC that became the driving force of schisms in 2023.

On 1 September 2019, an ad hoc committee of Oromo clergy announced the creation of a new regional parish administration entity under the EOTC in response to complaints against administrative imbalances with the church (Chala, Citation2019). The ad hoc committee stated that the new entity would be responsible for administering and managing all ecclesiastical affairs in the region, including the appointment of clergy, distribution of resources, and management of church properties (Chala, Citation2019). The committee also announced the formation of a new regional synod, which would be responsible for governing the church in the region and demanded to establish a local ‘episcopacy’ that could serve the Oromo Orthodox community’s linguistic, administrative, and spiritual demands (Chala, Citation2019). Accordingly, three Orthodox archbishops led by Abuna Sawiros constituted a new Orthodox synod in Oromia on 22 January 2023 and ordained 26 new bishops without the consent of the EOTC Holy Synod (Haustein et al., Citation2023). The three Holy Fathers announced that throughout church services, including the liturgy and the sermon, the Oromo people used to ask to use their language.Footnote1 Their query could be reasonable and accurate from a democratic perspective as it was one of the major claims of the Oromo Orthodox Christians. However, the EOTC Holly Synod excommunicated all the newly ordained episcopates including the three archbishops and the schismatic on 26 January 2023 (Haustein et al., Citation2023).

On the other hand, the administrative relationship between the EOTC and Tigrayan Orthodox clergy was also affected negatively during the Tigray War (Haustein et al., Citation2023). During the war, the Tigrayan clergy was unhappy with ETOC as a result of the intention of the church was to support the war both financially and morally. According to Ademe and Ali (Citation2023), the major reason that led the Tigrayan Orthodox clergy to suggest a schism was that the EOTC did not blame the war announced on the people of Tigray as expected from such the strongest religious organisation in the country. This schism was conceived in December 2021 by the International Orthodox Association of Tigray Clergy which was founded in March 2021 as a result of the EOTC’s position on the war (Haustein et al., Citation2023). The Holy Synod condemned Abuna Mathias’ stance on the war, which led to his isolation and silence (Ademe & Ali, Citation2023; Pellet, Citation2021). The Tigray Orthodox Tewahedo Church released a fresh statement in February 2022 announcing the creation of a local patriarchate (Haustein et al., Citation2023). Following the announcement of local parish administration and schismatic in Oromia in 2023, the Tigrayan church leaders have also agreed on establishing an independent TOTC as a result of the discomfort they felt with the EOTC’s Holy Synod during Tigray wartime (Ademe & Ali, Citation2023). The idea was initiated by some Tigrians residing in the West who named their churches after members of their families, Philadelphia’s Debre Selam Kidist Silassie Tigrian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (Yohannes, Citation2023). Consequently, the Tigrayan Orthodox Tewahedo Church ordained 9 Episcopates on 16 July 2023. As a result, it is a dishonour for the EOTC Holy Synod that Tigray’s TOTC was founded independently from its mother church (EOTC), and the EOTC Holy Synod excommunicated them on 2 August 2023.Footnote2

Since the attempts made to establish a local episcopacy and parish administration that can serve in the local language in Oromia,Footnote3 Tigray and other regions of the country,Footnote4 hate discourses towards and against the EOTC and the intended local parish administrations have been escalated on online media platforms. The opportunity that the people enjoyed relatively better freedom of expression through every kind of mass media platform since PM Abiy came into power in 2018, appeared to be abused when it comes to religious discourses (Chekol et al., Citation2023). The expansion of hate discourses and fake news on online platforms excreted and affected the lives of millions of people in Ethiopia (Jacobson, Citation2019; Kiruga, Citation2019). This freedom of the press and freedom of expression has enabled citizens to voice their opinions and speak out on issues that otherwise would not have been considered in the EOTC.

Hate speech, religion and human rights

Hate speech is defined as any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language concerning a person or a group based on who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor (Cohen-Almagor, Citation2011; McGonagle, Citation2001; United Nations, Citation2020). Other scholar defines it:

The term ‘hate speech’ could mean something like speech or other expressive conduct which insults, degrades or defames negatively stereotypes or incites hatred, discrimination or violence against persons or groups of persons based on their race religion or sexual orientation or gender identity or disability and which is intimately connected with feelings, emotions or attitudes of hate or contempt or despisement (Brown 2017: 564–565).

Such hate discourses are becoming influential and leading towards to threat to peace deterioration and harmony in religious institutions as a result of political, ethnic, and linguistic diversities among the followers. In connection with religious tensions are provisions rooted in colonial laws that limit speech and incite disorder and violence that threaten national security (Pohjonen & Udupa, Citation2017). These laws have been used to suppress religious minorities and stifle freedom of expression hurting the right to freedom of religion, belief and expression, which are fundamental human rights. According to Degol and Mulugeta (Citation2021), hate speech in the course of exercising this right has the potential to pose threats to the peace and security of nations and the well-being of individuals.

A progressive human rights approach contends that the dominant group in a diverse society does not require the law to protect it from insult or intellectual assault if its religion or culture is already prevalent (George, Citation2015). The approach focuses on protecting minorities and ensuring that they are not discriminated against because of their racial, ethnic, gender, sexual orientation, or religious identity. It also seeks to ensure that everyone has access to the same rights and opportunities regardless of their background. In India, Pakistan, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka, online media is often subject to regulation under legal measures intended to prevent hate speech based on religious harmony and public safety (Pohjonen & Udupa, Citation2017). Following the arrival of refugees, widespread racism and xenophobia on Facebook in Europe has once again brought the contentious discussion about the boundaries of free speech and steps to stop online hostility to the forefront (Pohjonen & Udupa, Citation2017; Rowbottom, Citation2022). In Ethiopia, because of its unregulated user-generated content, social media sites have recently become a channel of hate speech (Chekol et al., Citation2023).

Due to the resistance of EOTC to accept worship’s translatability to all cultures and languages, it has slowly become a source of competition between members of the same broad church of different ethnic backgrounds (Sonessa, Citation2020). This has led to a divide in the church between different denominations, with some believing that certain linguistic differences should be accepted and others believing that services should be done in the language of the people with minimal and regulated proportions. This divide caused tension and disagreement which was further complicated by the inquiry of language, by making it difficult for the top leaders and followers to agree on a single Holy Synod of the ETOTC.

The role of religion in fomenting and alleviating conflict has evolved within the context of decades-old debates about religious peace-building (Hayward, Citation2012). Religion has been seen as a source of division and conflict, as well as a source of reconciliation and peace. Several scholars argue that religious institutions do have the potential for two contradicting cultures: peace-making and warmongering both of which are dependent on the interests of their leaders (Abu-Nimer, Citation2001; Alger, Citation2002). Religion-based peace-building efforts have been focused on fostering dialogue and creating understanding between groups. Religious organisations advocate for peace and justice and work to end injustices based on religious discrimination and conflict (Abu-Nimer, Citation2001; Palm-Dalupan, Citation2005). They have also been promoting the rights of religious minorities, and advocating for religious freedom that provides humanitarian assistance to those in need and have worked to build resilient communities (Abu-Nimer, Citation2001).

This has been informed by the more extensive legal discussions surrounding speech limitations (Warner & Hirschberg, Citation2012). A recurrent theme running across the discourse is that hate speech entails disparaging other groups based on their membership in a particular group of collective identity, notwithstanding disparities between legal traditions and academic discussions. According to Waldron (Citation2012), this type of discourse has two important traits: first, it dehumanises members of other groups, and second, it strengthens the boundaries between the in-group and the out-group by disparaging the members of the latter group. The regulatory justification for hate speech is therefore one of control and containment because hate speech predefined the impacts of hate speech as harmful and destructive (Udupa, Citation2023). Online discourses and social media platforms have created their terms of service to identify, control, and outlaw hate speech in response to concerns raised by civil society, legislative directives, and international treaties on the subject (Udupa, Citation2023). Posts that disparage someone for their real or perceived colour, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sex, gender, sexual orientation, handicap, or sickness are not allowed on Facebook, among other platforms (Gracia-Calandín & Suárez-Montoya, Citation2023; Pohjonen & Udupa, Citation2017).

Related work

In light of recent studies by Workneh (Citation2019, Citation2021) showing a high incidence of hate speech on social media in Ethiopia, scholars contend that ethnic politics and EPRDF official rhetoric are to blame. Critics have cautioned that such ethnic politics could degenerate into ethnic prejudice and ethnically motivated violence (Gagliardone et al., Citation2014). The use of social media has increasingly been used by racists and other racialised groups to engage in new and old forms of oppression (Matamoros-Fernández & Farkas, Citation2021). Nowadays, it is more common to see racial discourses being moulded and reoriented in Ethiopia’s various ethnic groups, and these discourses are commonly seen on social media platforms. For these and other reasons, research demonstrates that social media acts as a platform for bullying, bigotry, discrimination, prejudice, and intolerance based on social identities like race, religion, country, sex, colour, and others (Chekol et al., Citation2023; Cohen-Almagor, Citation2011; McGonagle, Citation2001). In comparison to personal information, messages about people’s country, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, occupation, gender, or handicap have a greater impact (Chetty & Alathur, Citation2018). Hate speech against religion is more detrimental than hate speech against an individual since religions contain groups of individuals (Chetty & Alathur, Citation2018). Because of this, opponents have expressed concern that such ethnic politics could degenerate into ethnic prejudice and violent acts with an ethnic motivation (Gagliardone et al., Citation2014).

The effects of online hate speech and misinformation on the social, economic, and political development of modern Ethiopia in contrast to freedom of expression have been the subject of a significant number of studies. According to Assen (Citation2023), the liberation of social media has resulted in an explosion of information, deception, fake news, and hate speech, which have all become part of Ethiopia’s everyday life. Ayalew (Citation2022) also issued a similar warning, stating that the spread of hate speech online threatens human and democratic rights as well as enduring societal cohesion and may ultimately result in political and socio-physiological disorders. Others have also noted that the increased freedom of social media is being abused and that the spread of hate speech and fake news has had an impact on millions of people’s lives, commercial activities, and civic movements. In the same vein, millions of people are being evicted, and hundreds have died in Ethiopia as a result of disinformation and fake news on social media platforms (Chekol et al., Citation2023; Jacobson, Citation2019; Kiruga, Citation2019). According to Chekol et al. (Citation2023), factors that are associated with political history, ethnicity and land resources were exacerbating the hate speech observed on online social media platforms in contemporary Ethiopia.

Workneh’s (Citation2021) study focuses on the importance of social media platforms in mobilising marginalised Ethiopians towards political reforms during and after Abiy Ahmed’s election as Ethiopia’s Prime Minister. His study has found that social media were a powerful tool for mobilising citizens, with Facebook being the platform of choice. Through social media platforms, youth can express their views, share news, and connect with others in a shared safe space (Gagliardone et al., Citation2016; Workneh, Citation2021). This gives them a voice and platform to help shape the public debate, while also allowing them to form meaningful connections with others. However, the rise of hate speech on social networking sites in our contemporary era demands close follow-up regulations (Assen, Citation2023; Ayalew, Citation2022; Degol & Mulugeta, Citation2021; Workneh, Citation2019). According to Abu-Nimer (Citation2001), although religions frequently provide significant political capital to the cause of maintaining peace, they may also act as a catalyst for conflict, especially considering how frequently religious identity is tied to ethnic identities. Hayward’s (Citation2012) study also verifies that although many religious organisations have long been involved in their efforts to promote peace, justice, and development, the birth of the secular field of peace-making has encouraged religious communities to formalise and institutionalise their efforts at interfaith peace-building. This institutionalisation has enabled religious leaders to capitalise on their shared values of love, compassion, and justice, and use them to build bridges between communities. It has also provided a platform for religious communities to collaborate on projects and initiatives that have a lasting impact as religious organisations could play both in conflict aggravation and conflict resolution (Abu-Nimer, Citation2001).

Despite having been some research that addresses social media hate speech in Ethiopia, the studies were lean analysing a sample of related Facebook page posts. The studies ignore social media posts and users’ comments that focus on religious institutions. Since none of the studies examined how hate speeches can affect harmony within a religious institution like the Ethiopian Orthodox church (Chekol et al., Citation2023), it is crucial to study how hate discourses can be mitigated and avoided to protect religious institutions and foster harmony. Both historical and contemporary evidence show that EOTC is a religious majoritarianism that consists of culturally and linguistically diversified (Haustein et al., Citation2023). However, recently there has been a deep sense of distrust as a result of linguistic, ethnic and cultural backgrounds among some of its followers. Hence, it is argued that a peaceful society must protect religious freedom and respect for linguistic and cultural diversity in the religion. This lack of research is particularly considering the potential negative consequences of hate discourses on religious institutions. Nonetheless, it is critical to investigate whether the social media platforms exaggerate conflicts in the EOTC are the primary cause of this societal discord in Ethiopia.

The purpose of this study is, therefore, to investigate how social media discourses have contributed to deteriorating unity and harmony among Ethiopian Orthodox Christians during attempts to establish Oromia and other Nations’ Nationalities Synod and Tigrayan Orthodox Synod.Footnote5,Footnote6 and how these attempts and their responding mechanism were treated by the EOTC Synod have been marked by ethnic tensions.

Methodology

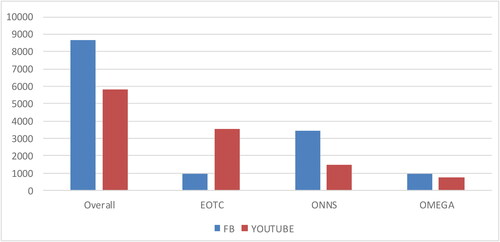

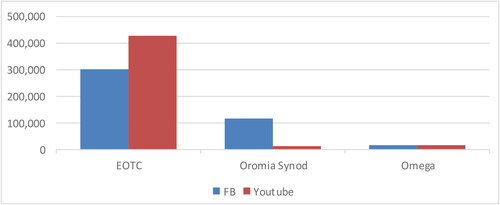

The design of the study was a qualitative conceptual content analysis of the social media network sites of EOTC TV, ONNS, and Omega TV that were purposefully selected. The posts and comments considered for collecting data publications were based on the EOTC TV’s FB page which has 303,000 FB followers and 429k YouTube subscribers, the Oromia Synod FB page having 116,000 followers and 15k YouTube subscribers, and the Omega TV FB page having 17,000 followers and 17k YouTube subscribers during the time of data collection as indicated in . All of them were purposefully determined as they had a significant number of followers (17,000–303,000) on FB followers and (15k–429k) on YouTube subscribers during the time of writing this paper. These posts and comments were used to determine the public opinion on the matters discussed. They were also used to gain insights into how the followers of the religion felt about certain issues and topics. Finally, the data was collected and analysed to gain a better understanding of the public’s opinion based on these social media networks.

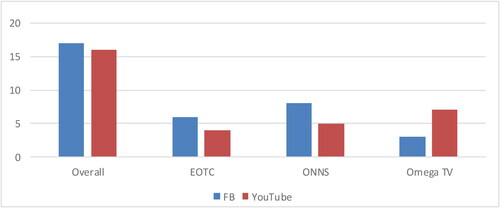

Figure 1. Occurrences of overall hate discourses by social media network categories (Facebook and YouTube).

The dates ranged from 1 September 2019 to 31 August 2023 were selected for data collection because the duration was specifically eventful in terms of relevant debates, conflicts and issues of linguistic and cultural diversity within EOTC. These include the request of an ad-hoc committee to establish the Oromia Synod under the umbrella of the EOT church on 1 September 2019 followed by tens of thousands of comments, debates, posts, and opinions; the 26 Episcopates Ordaining for Oromia and other Nations Nationalities at Woliso on 22 January 2023, the 9 Episcopates ordained for the Tigray Orthodox church on 23 July 2023. Both of the events were followed by an emergency meeting and were eventually excommunicated by the Holy Synod of the EOTC.

Data collection, classification and coding procedure

By using manual coding for analysing the data, 8,662 contents of Facebook users’ comments from 17 posted religious stories were published and 5,820 contents of YouTube users’ comments from 16 uploaded stories accounting for a total of 14,482 individual users’ comments on the 33 purposefully selected religious stories published on the three selected organisations’ online platforms (see ). The data collection was conducted from 1 August 2023 to 31 August 2023. 22 January 2023 to 29 February 2023 and 1 June 2023 to 31 August 2013 were the months when the highest comments on religious conflicts were assumed to be at their peak or highest in connection with the ordaining of ONNS Episcopates and Tigray Episcopates. For the analysis of this particular study, the stories posted and comments on the Facebook pages of Oromia Nations Nationalities’ Synod (ONNS), EOTC television and Omega television dealt with major religious conflicts incidents such as claiming of church services by own linguistic and cultural backgrounds of Episcopates and other religious experts, churches resources administration and utilisation, and schisms of regionally based parishes administrations. Accordingly, 14,482 users’ comments from the 33 stories around three major events posted on three media’s Facebook pages and YouTube channels have been collected from 1 August 2023 to 31 August 2023 shown in . All the comments were collected using the data extraction method (copying and pasting) into the datasheet prepared for the purpose of this study. Copying and pasting data from social media network platforms into a spreadsheet has been applied by several studies (Abramson et al., Citation2015).

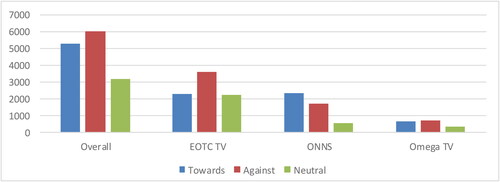

The unit of analysis did not focus on the non-verbal resources (such as like, share, dislike, images and other feeling expressions) of the comments. The verbal resources of the users’ generated comments on the conflicts around the religious issues in EOTC on the three social media networks were manually coded for analysis by to two annotators (the researcher and the recruited PhD student). Coding and annotating data manually has been recommended by various literature sources (Chekol et al., Citation2023; Jikeli & Soemer, Citation2023; Kennedy et al., Citation2018). This coding frame was used to identify and categorize the different types of expressions used in each sentence. A binary analysis was carried out first to determine what constitutes hate and what does not (Chekol et al., Citation2023). The binary analysis was first made after having a common understanding between the two annotators through discussions and by considering a few examples of comments copied and pasted from the organizations social media networks. The coding procedure was first to determine each comments either as hate or not hate, and then followed by the determination of the hate comments as going forward (positive) to the story posted and going against (negative) to the stories posted. As a result, each comment was annotated in accordance with three labels defined as follows: (1) Going forward (hate but positive to the story posted), (2) going against (hate but negative to the story posted), (3) neutral (not hate at all).

Thus, the coded comments were generally classified as positive (going towards), neutral (negotiations) and negative (going against) the original stories posted by the three social media networks of the organisations. For this particular study, comments that attack or against the stories posted or uploaded on social media networks by disparaging, challenging, annoying, provoking, bantering with them malevolently, or openly intimidating them were coded as ‘going against’. Comments that help initiate, maintain, and/or build a communicative relationship, for example acknowledging the position of stories posted or uploaded were coded as ‘going towards’ (Gagliardone et al., Citation2016, p. 16). While ‘going towards and going against is not about agreeing or disagreeing, but more about the tendency to take a viewpoint seriously and engage with it, or, on the contrary, to dismiss it and directly attack a person for his/her affiliation with a specific group’ (Gagliardone et al., Citation2016, p. 16). The textual user’s comments that dealt with reconciliations, peaceful ways of negotiation, win-win approaches, and faithful prayers were all coded as the presence of neutral comments. The textual users’ comments that dealt with derogatory terms, insults, discriminatory and pejorative terms in support of the original stories were all coded as the presence of negative comments, while textual users’ comments that neither carry supportive nor discouraging spirits were coded as the presence of neutral comments.

This study adopted hate speech classifications based on various literature. Accordingly the employed definitions of hate speech provided by Article 19 (Citation2015); Federal Negarit Gazette (Citation2020), and Press Unit (Citation2023). As shown in , 14,482 textual users’ comments in Amharic, Afaan Oromo, Tigrigna, and English were manually coded and analysed. Out of these, 8,167, 4,609, and 1706 comments, respectively, were gathered from EOTC TV, Oromia and other Nation Nationalities Synod, and Omega TV social media networks.

In order to determine inter-annotators’ agreement (IAA), we randomly sampled 150 comments from the three social media network sites comprising 25 comments from each site to inspect their content. That is, 75 comments from the FB pages of the organizations and 75 comments from the YouTube channels of the organizations were randomly chosen for the initial computation of the inter-annotators’ agreement. Using the simplest approach to measuring annotators’ agreement recommended by Artstein (Citation2017) we counted the items for which we each supplied the same label and presented that number as a percentage of the entire amount that has to be annotated. We, therefore, conducted intercoder reliability checks through the calculation of percent agreement and obtained a high agreement rate (89.3%) that confirms the internal consistency and validity of this study. Of the total 150 comments, 89.3% were placed in the same categories by two annotators.

This study is purely relied on publicly available data (users’ generated comments of FB and YouTube channels) that it does not require informed consent. According to Abramson et al. (Citation2015), neither Page owners nor users were required to provide consent to analyze their posts because Facebook posts are publicly accessible. ‘Facebook wall posts are publically accessible and therefore consent to analyse the posts was neither required nor obtained from either Page owners or users’ (Abramson et al., Citation2015, p. 238).

Ethical consideration

All the addresses the analysed samples (labelled as Example 1 to 11) from the FB pages and YouTube channels anonymised for the purpose of confidentiality. This study followed the guidelines of the American Psychological Association’s research ethics committee (American Psychological Association, Citation2017). This study is purely relying on publicly available data (users’ generated comments on Facebook pages and YouTube channels) and it does not require informed consent. The usernames and images after Facebook and YouTube logos were purposely blackened to de-identify the individual people for confidentiality. The process of de-identifying users’ usernames or images is crucial to protecting the privacy of that individuals and securing their personal information. As a result, the researcher de-identified and masked the individuals’ identifier usernames and images represented by Examples 1–11 for protecting individuals’ privacy to complying research ethics that enables to sharing responsible data.

Results

Occurrence of social media hate speech in Ethiopia

By examining the users’ comments found on selected YouTube channels and Facebook page groups, the study found out the extent of hate discourses within the EOTC on the social media sphere.

From the categorical manual annotation of the total 14,482 comments by users, 11,311 (78.1%) of those comments were hateful from the three YouTube channels and Facebook pages of the selected organisations either by going towards or going against. The remaining 3171 (21.9%) comments were not hate-related. By far, the greatest number of hate speech incidents was reported on social media by EOTC, as shown in . The hate discourses on users’ comments towards, against and neutral to the stories posted on the social media network sites of the organisations are all significant. Overall FB and YouTube users’ comments indicated that the attempts to establish Oromia and other Nation Nationalities’ Synod and the Tigray Orthodox Tewahedo Synod were targeted by the followers of EOTC and vis-à-vis. The commenters refer to schisms in the EOTC that integrated into the Ethiopian political history, church administration, resource allocations, and lack of support that offend mainly the Oromo, Amhara, and Tigre ethnic groups.

In their Facebook and YouTube accounts, Ethiopian social media users commented on selected media stories using hate words and phrases. The size of each violent, negotiation and offensive comment is identified using these hate comments. The analysis of these comments helps to provide a better understanding of how negative online comments can affect the unity and harmony the EOTC had and how the positive comments can contribute to the church’s role in peacebuilding. As shown in , among the coded comments of users on the intended social media sites, comments going against the stories were recorded as the highest with 6030 (41.64%). The total size of users’ comments going towards the stories posted on the selected social media sites media was 5281 (36.47%). In both directions, going against and going towards user comments threatened peace and deteriorated the EOTC’s unity and harmony. The neutral category of the users’ commentaries on YouTube channels and Facebook pages was also important for this particular study. They all carry prayer messages that encourage peace, solidarity, unity, harmony, negotiations, and discussions on differences and discourage conflicts and enmity within the church. These prayer messages also emphasise the importance of forgiveness, understanding, and compassion. They call on us to be mindful of our actions and words and to be open to learning and growing together to create a more peaceful and just world.

Furthermore, indicates hostile user comments predominate in both the pros and cons directions on EOTC’s Facebook and YouTube channels. On ONNS’s Facebook and YouTube pages, users left the next-highest amount of positive and negative comments; nevertheless, Omega TV’s social media pages had the fewest positive and negative user comments. Social media networks give people a forum to post their complaints and ideas, which can spark contentious discussions or even violent altercations. They also make it easier for people to spread false information or misinformation, which can lead to misinterpretation of facts and further conflict. As shown in , going towards and going against the comments of the followers were highest which either encouraged one faction or degraded the other faction without the total comments of 78.1%.

How social media platforms exacerbate intra-conflicts within the EOTC

Hate discourse on social media can indeed deteriorate unity and harmony within EOTC. This study identified that when individuals engage in hate speech or spread divisive narratives on social media platforms, it exacerbates conflicts within the church encouraging the existing schisms and divisions within the church. Hence, social media platforms can be a platform for people to spread hate discourses or offensive language, which can further degrade the EOT church’s ability to spread its message and reach its intended audience. Some examples of hate comments that support the quantitative results appeared on the Facebook pages and YouTube channels pertinent to each Synod that may jeopardise the unity and harmony within the Church and aggravate the intra-conflict of EOTC are presented hereunder.

Example 1

Example 2

The commenter with the YouTube address presented on Example 1 comment going against the ONNS story posted describes the Episcopates of ONNS as ‘ኦርቶ ኦነግ ጳጳሳት’Footnote7 literarily translated as ‘OLF Orthodox Bishops’ to associate with the political party of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF). Many non-Oromos and few political parties used the word OLF to render Oromos who struggle against oppression, injustice, and disproportionate in every aspect of social life as killers and terrorist groups to demoralise the Oromos. On the contrary, the other commenter with the YouTube address indicated on Example 2 comment went toward the story posted on ONNS and described the non-supporter of ONNS as ‘Neftegan is a killer’.Footnote8 The word ‘Neftegna’ is a derogatory term used to describe the Amharas as gunslingers who often yarns old order or the feudal system that used to kill the Oromos and other nations in Ethiopia to secure Amhara supremacy and dominance. The two words OLF and Neftegna represent contradicting terms to highlight the disagreement between the Oromos and the Amharas in Ethiopian politics that has been reflected in the EOTC. The enthusiasm for religion that has shaped Ethiopian history has concealed this ambition for political domination (Sonessa, Citation2020). It has prevented the nation from reaching its full potential. This desire for power has to be addressed if the country is going to move forward. It is essential that all citizens, regardless of ethnicity or religion, are treated equally and given the same opportunities. The following comments on social media platforms also signify these realities.

Example 3

Example 4

Example 5

The above comment on Example 3 is a comment going against a story posted on the ONNS Facebook page favouring the EOTC. It describes the Oromia and other Nation Nationalities’ ordained Episcopates and the Tigray Orthodox ordained Episcopates as OLF’s and TPL’s bishops respectively.Footnote9 The commenter prays to God to comfort the church, as if it lost its members. In contrast to this comment an individual represented by Example 4 whose comment is going against the topic posted on EOTC’s TV Facebook page describes the EOTC’s Holy Synod as worshipers of Satan and war preachers.Footnote10 The comment is full of emotion that degrades the respect the Holy Synod and Holy Fathers have in the history of EOTC. The other comment presented on Example 5 whose comment was going toward the ONNS being against the EOTC uploaded on its Facebook page. The commenter expressed his feeling that the disrespectful Amhara Synod recently handed over the seat of Finfine to the Oromo Synod and will move to Bahir Dar.Footnote11 This comment intends to address that the EOTC’s Holy Synod is dominated by the Amhara ethnic background. All three comments could be linked to the offensive categories of hate speech according to Article 19 (Citation2015) and Press Unit (Citation2023) hate speech classifications. According to this classification, the below comment is dangerous and highly contributes to the threats to the unity and harmony within the church.

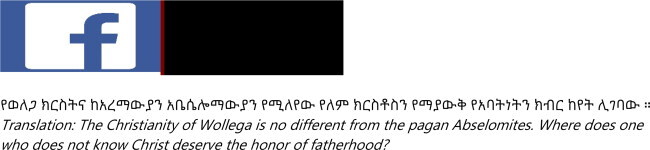

Example 6

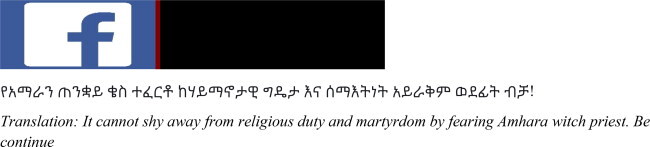

The user-generated comment replaced with Example 6 is a dangerous speech that demoralises the followers of Orthodox Christians in Oromia zones (Wollega) found on the ONNS Facebook and appears in response to the attempts to establish Oromia regional parish administration under EOTC. The commenter equates Orthodox Christianity in Wollega with Abeselomites pagans who do not know Christ.Footnote12 The commenter is against the selection of Episcopates from Oromo ethnic background (Wollega). Contrary to this, priests who come from Amhara are often blamed to be involved in evil deeds that cannot be preferred by the local religious fathers. The commenter indicated in Example 7 signifies that the Holy Synod is dominated by the Amhara ethnic group and does not like Afaan Oromoo services in the Church. The commenter demoralises the Holy Fathers by equating them with witches who are involved in evil deeds.Footnote13 In both incidents, the reputation of the EOTC and its place on the national and international stage is damaged and leads to conflict that deteriorate unity and harmony within the church. This confirms that having a difference of understanding when it comes to religious and ethnic issues, coupled with a crisis of leadership, often fuels ethnic tensions that do more than sour believers’ relationship with each other, but also damage the church’s reputation (Sonessa, Citation2020). This can cause people to distance themselves from the church, leading to a decrease in church attendance and a decrease in donations. The next examples of commenters’ hate discourses signify the historical narratives that could activate conflicts between Oromo and Amhara.

Example 7

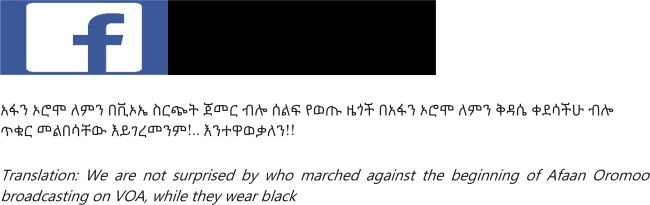

Example 8

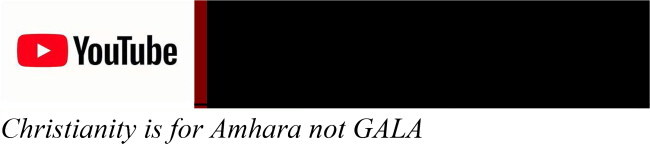

Example 9

The comment assigned by Example 8 was in response to EOTC Christians who wore black by protesting against the establishment of ONNS and the ordaining of the 26 Episcopates. The commenter stated how one can expect liturgy services in Afaan Oromoo from the people who marched against the broadcasting services in Afaan Oromoo on VOA.Footnote14 As a result, it is not surprising while they were wearing black against the liturgy service conducted in Afaan Oromoo. The commenter is clearly against the black wearers and the Holy Synod that excommunicated the ordained episcopates. It can be noted that the Holy Synod of EOTC called all Christians Orthodox to fast Nineveh by wearing black in 2023 (Human Rigths, Citation2023). In contrast, the second commenter assigned in Example 9 targets the Oromo ethnic group by describing Christianity as for Amhara, not for Galla.Footnote15 The comment not only discourages Oromo Orthodox Christianity but also demoralises them by calling them a pejorative name. These settings can provide insight into the prevalence of hate speech in a certain nation that could lead to a breakdown in communication between Oromo and the Church, as well as the potential for a schism.

Perception of social media users regarding schisms in the EOTC

From the user-generated comments on social media platforms, the study attempts to understand the perceptions of social media users by analysing social media conversations related to the schism in the EOTC. It can be noted that the committee to establish the Oromia clergy service argues that establishing the church’s administration based on state structure would assist in bringing the church closer to the Oromo people and that in turn would help the EOTC to fulfil its apostolic vocation, in addition to attempts to institutionalise the usage of Afaan Oromoo in the church (Chala, Citation2019). Oromo clerics claim that the EOTC wants Oromos to worship in either Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia, or Ge’ez, the church’s liturgical language, in contrast to Protestant churches that provide Afaan Oromoo services (Chala, Citation2019). This has caused tension among Oromo believers, as they are uncertain about their status and place in the church. Furthermore, they provide an alternative to the EOTC for Oromos who are not comfortable with the EOTC’s stance on Afaan Oromoo. The new administrative unit, according to a different member of the ad hoc committee, will aid in re-engaging those who left the church out of alienation (Chala, Citation2019). I argue that the absence of appropriate responses to the question of the religious followers, and fathers among the Ethiopian Orthodox church would not only deteriorate solidarity among the followers but also contribute to the economic, political and cultural influence and voices of the church would be deteriorated. The following examples can indicate the perception of social media users’ generated comments.

Example 10

Example 11

The comments above show the association of ethnicity and religion among the three dominant ethnic groups in Ethiopia (Oromo, Amhara and Tigre). These comments were offered on Omega TV’s and ONNS’s YouTube channels going against the stories about the excommunication of the Holy Synod of EOTC upon the ordaining of the 9 Episcopates of the Tigray Orthodox Tewahedo Church at Axum Tsion Mariam Monastery in the Tigray region. The first comment on the YouTube channel of Omega TV identified as Example 10 says that ‘You satanic fathers met together to destroy the people of Tigray and campaigned on us but the real God will destroy these Goliaths and believe me we will repeat the story of David with the help of God.Footnote16 The second comment in Example 11 above was uploaded on ONNS’s YouTube channel dehumanising the supporters of breaching the Bible in Afaan Oromoo. The commenter perceived that it was Emperor Menelik who gave them the chance Oromos to become Orthodox Tewahedo’s Church followers bringing them from wearing skin and worshipping trees by saying ‘Thanks to Menelik, who freed you from being a skin-wearer and a tree-worshipper, and who freed you from slavery’.Footnote17 This is a dangerous comment which not only threatens peace but also threatens unity and harmony within the EOTC’s followers of Oromos and Amhara ethnic backgrounds. Menelik II, the Emperor of Ethiopia from 1889 to 1913, is a figure who evoked mixed reactions among different Ethiopian ethnic groups. The reasons behind the differing views of Menelik II among Oromos and Amharas are complex and rooted in historical, political, and social factors. This historical context shapes the perspectives of both Oromos and Amharas (Hussein, Citation2006; Jalata, Citation2010; Kelecha, Citation2023; Steyn & Hendrickx, Citation2020). The Church’s unwelcoming atmosphere and forcing attendance are perceived as shortcomings by some inactive followers (Bekele, Citation2021). Many followers could be tempted to drift away from the Church due to comments such as these, which would be an enormous loss to the Church since these followers would be beneficial both to their spiritual growth and to the Church as a whole if they were present.

Conclusions

Hate speech on social media in Ethiopia in the EOTC exhibited an upward tendency mainly after the introduction of establishing Oromia regional parish administration. As indicated in , among the coded users’ comments on the intended social media sites, comments going against the stories were recorded as the highest with 6030 (41.64%). The total size of users’ comments going towards the stories posted on the selected social media sites media was 5281 (36.47%). In both directions, going against and towards user comments threatened peace and deteriorated the EOTC’s unity and harmony.

The data demonstrates that hate speech on social media was significantly more common in religiously oriented media platforms. Out of 14,482 user comments, it was discovered that 6030 (41.64%) users’ comments incited hostility by criticising the stories that the organisation’s chosen social media networks posted. This finding indicates the highest hate discourse occurrences compared to the previously conducted studies. For example, the study conducted on the social media hate speeches in the walk of Ethiopian political reforms by Chekol et al. (Citation2023) found 2834 (33.2%) out of 8525 users’ comments and the finding of the Mechachal project indicates 0.4% out of the total 13,000 hate speech that discriminates individuals based on their political and religious preferences and ethnic backgrounds (Gagliardone et al., Citation2016). The finding of this study seems to indicate that as the people of Ethiopia relatively enjoyed the freedom of expression from the media, the prevalence of hate discourses on social media networks increased as the study focused on groups of religious-focused social media platforms.

The study also analyses the key elements that incite hate speech on social media in Ethiopia that are integrated into religious-based networks. Most frequently, historical issues, language issues and the intersection of ethnicity and religion occurrences and the claim of institutionalising Afaan Oromoo service in the church. These issues often lead to complex and difficult conversations, as the topics are often controversial and sensitive. To have productive discussions, it is important to approach the conversations with an open mind and respect for all sides. It is also important to remain focused on the facts and to avoid personal attacks or inflammatory language. Because hateful and dividing speeches are a result of current events like tensions between Holy Fathers who have an interest in establishing regional parish administration and the Holy Synod of EOTC and their supporters. Inter-communal conflicts, and ethnic or religious leaders attempting to schism by inciting their followers against one another, particularly after the fall of authoritarian central governments aggravated the prevalence of hate speech (Benesch, Citation2014).

According to the study findings, schisms within the EOTC are intensifying tensions that could negatively affect unity and harmony within the church due to the high levels of ethnic tensions and social media network posts and comments. It is therefore crucial that the intra-religious conflict in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church be addressed to ease identity tensions before it contributes to identity politics that may provoke severe harm. This can be achieved by engaging in constructive dialogue and promoting understanding between the different factions within the Church.

It was hypothesised that upholding human rights and allowing people to practice their religion freely in their language preferences, all of which are acknowledged as signs of tolerance, could aid in preventing the use of religion as a justification for conflict and violence while also fostering peace and reconciliation in areas where such violence has historically been fuelled by religion. Religious leaders should also take a lead role in helping to bridge the gaps between the different factions and work towards a shared understanding. Ethiopia requires crucial institutional arrangements that enable a truly intra-religious dialogue within the Orthodox Church to address the issues of acknowledging the linguistic and cultural diversity of religious adherents to maintain peace and harmony in society. We need to be aware of the power of social media and use it responsibly to maintain a safe online environment religious institutions should be supported and empowered to take measures to combat hate discourses.

Future research

There are some limitations to the methodology that should be addressed in future studies. First, the study relied on solely the analysis of users’ comment of the FB pages and YouTube channels of EOTC TV, ONNS, and Omega TV respectively were heavily relied upon in this study because it focused exclusively on hate speech on social media network sites. The study’s results were not representative of the entire religious population, as the analysis was based limited users generated comments uploaded. Future can also benefit hate speech discourse analyses of the organizational social media platform posts. Second, as this study focused on users’ comments, it did not engage the views of key actors in the EOTC and other religious institutions to mitigate online hate speech. In future research, it will be crucial to look at a broader range of actors, including the views of religious fathers and servants, and other religious communities through interviewing participants. These interviews would provide a more holistic understanding and could help to shed light on the complexities of hate speech among religious organizations. Finally, it would be beneficial for future studies to include comparative studies with other religious communities or to incorporate intervention strategies to mitigate hatred. Such studies could provide more in-depth insight into the underlying causes of religious hatred, as well as more effective strategies to address it.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge my beloved wife, Mrs Chaltu Olana and my daughter Miranol Geremew and my son Raji Geremew for their unreserved courage and moral support in writing this article. My acknowledgment goes to journal editors and all anonymous reviewers for their constructive and critical comments that could immensely benefited the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Geremew Chala

Geremew Chala is an assistant professor of journalism and communication in the Department of Afaan Oromoo, Literature and Communication at Haramaya University, Ethiopia. He is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Communication at University of South Africa. His research interest include media studies, public relations, political communication, social media and decoloniality.

Notes

1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AAAGSnkfyOk

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XlFjeta6ysw&t=300s

4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UolcSaIoxKM&t=2130s.

5 https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=205151505360183&set=a.179584377916896

6 https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=259318246610175&set=a.179584377916896

7 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EPvXpSwGduI&t=759s

8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3ueuf7COps&t=247s

9 https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=sinoodoosii%20oromiyaa

11 https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=sinoodoosii%20oromiyaa

12 https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=sinoodoosii%20oromiyaa

13 https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=sinoodoosii%20oromiyaa

14 https://www.facebook.com/eotctvchannel

15 https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=sinoodoosii%20oromiyaa

16 https://www.youtube.com/@omegatv12

17 https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076713486929

References

- Abramson, K., Keefe, B., & Chou, W. Y. S. (2015). Communicating about cancer through Facebook: A qualitative analysis of a breast cancer awareness page. Journal of Health Communication, 20(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.927034

- Abu-Nimer, M. (2001). Conflict resolution, culture, and religion: Toward a training model of interreligious peacebuilding. Journal of Peace Research, 38(6), 685–704. https://www.jstor.org/stable/425559 https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343301038006003

- Adamu, M. A. (2020). Role of social media in Ethiopias recent political transition. Journal of Media and Communication Studies, 12(2), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.5897/JMCS2020.0695

- Ademe, S. M., & Ali, M. S. (2023). Foreign intervention and legacies in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church. Heliyon, 9(3), e13790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13790

- Al Serhan, F., & Elareshi, M. (2019). University students’ awareness of social media use and hate speech in Jordan. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 13(2), 548–563. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3709236

- Alger, C. F. (2002). Religion as a peace tool. Global Review of Ethnopolitics, 1(4), 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/14718800208405115

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. APA. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520234277.003.0001

- Ancel, S. (2011). Centralization and political changes: the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the ecclesiastical and political challenges in contemporary times. Rassegna Di Studi Ethiopici, Nuova Serie, 3(46), 1–26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23622761%0AJSTOR

- Ancel, S., & Ficquet, É. (2016). The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC) and the challenges of modernity. In G. Prunier & E. Ficquet (Eds.), Understanding contemporary Ethiopia: Monarchy, revolution, and the legacy of Meles Zenawi (pp. 65–91). Hurst. https://www.academia.edu/download/54268021/ANCEL_FICQUET-2015-EOTC.pdf

- Article 19. (2015). “Hate speech” explained “a toolkit”. https://www.article19.org/data/files/medialibrary/38231/Hate_speech_report-IDfiles–final.pdf

- Artstein, R. (2017). Inter-annotator agreement. In N. Ide & J. Pustejovsky (Eds.), Handbook of linguistic annotation (pp. 297–313). Springer.

- Asale, B. A. (2016). The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church canon of the scriptures: Neither open nor closed. The Bible Translator, 67(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/2051677016651486

- Assen, M. D. (2023). Challenges of governance in an age of disinformation and hate speech in Africa: A lesson from the post-2018 Ethiopian experience. APSA.

- Ayalew. (2022). The disparity of Ethiopia’s hate speech and disinformation prevention and suppression proclamation in light of international human rights standards. Hawassa University Journal of Law, 6, 75–100.

- Bekele, B. (2021). Ethiopian Orthodox church leadership support of youth from Ethiopian immigrant families in the United States (vol. 148). Seattle University. https://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&context=eoll-dissertations

- Belachew, A., & Midakso, B. (2023). Social factors affecting religious institutions in the maintenance of peace and harmony in East Hararghe Zone: The case of selected religious institutions. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2175765

- Benesch, S. (2014). Countering dangerous speech: new ideas for genocide prevention. SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3686876

- Chala, E. (2019). A proposed administrative shift in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church stokes ethnic, religious tensions. GlobalVoices. https://globalvoices.org/2019/09/13/a-proposed-split-in-the-ethiopian-orthodox-church-stokes-ethnic-religious-tensions/

- Chekol, M. A., Moges, M. A., & Nigatu, B. A. (2023). Social media hate speech in the walk of Ethiopian political reform: Analysis of hate speech prevalence, severity, and natures. Information Communication and Society, 26(1), 218–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1942955

- Chetty, N., & Alathur, S. (2018). Hate speech review in the context of online social networks. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 40, 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.003

- Cohen-Almagor, R. (2011). Fighting hate and bigotry on the internet. Policy & Internet, 3(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.2202/1944-2866.1059

- Daba, M. (2023). Role of the inter-religious council of Addis Ababa in peacebuilding and conflict resolution. https://jliflc.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Moti-Daba_January-2023-1.pdf

- Degol, A., & Mulugeta, B. (2021). Freedom of expression and hate speech in Ethiopia: Observations (Amharic). Mizan Law Review, 15(1), 195–226. https://doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v15i1.7

- Devine, P. (2017). Radicalisation and extremism in Eastern Africa: Dynamics and drivers. Journal of Mediation & Applied Conflict Analysis, 4(2), 612–627. https://doi.org/10.33232/jmaca.4.2.9086

- Federal Negarit Gazette. (2020). March) Proclamation no. 1185/2020 hate speech and disinformation prevention and suppression proclamation. Federal Negarit Gazette, 26(26), 12339.

- Gagliardone, I., Patel, A., & Pohjonen, M. (2014). Mapping and analysing hate speech online. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2601792

- Gagliardone, I., Pohjonen, M., Zerai, A., Beyene, Z., Aynekulu, G., Bright, J., Bekalu, M. A., Seifu, M., Moges, M. A., Stremlau, N., Taflan, P., Gebrewolde, T. M., & Teferra, Z. M. (2016). Mechachal: Online debates and elections in Ethiopia-from hate speech to engagement in social media. SSRN 2831369.

- George, C. (2015). Hate speech law and policy. In R. Mansell & P. H. Ang (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of digital communication and society (1st ed., pp. 1–10). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118767771.wbiedcs139

- Gopin, M. (2000). Between religion and conflict resolution: Mapping a new field of study. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0364009403441007

- Gracia-Calandín, J., & Suárez-Montoya, L. (2023). The eradication of hate speech on social media: a systematic review. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 21(4), 406–421. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICES-11-2022-0098

- Haustein, J., Idris, A. K., & Malara, D. (2023). Religion in contemporary Ethiopia: History, politics, and inter-religious relations. Rift Valley Institute. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315762302-38

- Haynes, J. (2020). Introductory thoughts about peace, politics and religion. In J. Haynes (Ed.), Peace, politics, and religion (pp. 1–8). MDPI. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78905-7_31

- Hayward, S. (2012). Religion and peacebuilding: Reflection on current challenges and future prospects. http://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR313.pdf

- Human Rigths. (2023). The Holy Synod of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church declared to protest by wearing for three days. ZeHabesha. https://zehabesha.com/the-holy-synod-of-the-ethiopian-orthodox-tewahedo-church-declared-to-protest-by-wearing-black-for-three-days/

- Hussein, J. W. (2006). A critical review of the political and stereotypical portrayals of the Oromo in the Ethiopian historiography. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 15(3), 256–276.

- Jacobson, A. S. (2019). Social media and journalism in Ethiopia – setting the scene for reform. Fecha de Publicación.

- Jalata, A. (2010). What is next for the Oromo people? Sociology Publications and Other works. 4th Annual International Conference on Human Rights. https://trace.tennessee.edu/uk_socopubs/11

- Jikeli, G., & Soemer, K. (2023). The value of manual annotation in assessing trends of hate speech on social media: was antisemitism on the rise during the tumultuous weeks of Elon Musk’s Twitter takeover? Journal of Computational Social Science, 6(2), 943–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-023-00219-6

- Kelecha, M. (2023). Political and ideological legacy of Ethiopia’s contested nation-building: A focus on contemporary Oromo politics. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 002190962311610. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096231161036

- Kennedy, B., Kogon, D., Coombs, K., Hoover, J., Park, C., Portillo-Wightman, G., Mostafazadeh, A., Atari, M., & Dehghani, M. (2018). A typology and coding manual for the study of hate-based rhetoric. University of Southern California.

- Kiruga, M. (2019). Ethiopia struggles with online hate ahead of telecoms opening. https://www.theafricareport.com/19569/ethiopia-struggles-withonline-%0Ahate-aheadof-telecoms-opening/

- Larebo, H. M. (1988). The Ethiopian Orthodox Church and politics in the twentieth century: Part II. Northeast African Studies, 10(1), 1–23.

- Matamoros-Fernández, A., & Farkas, J. (2021). Racism, hate speech, and social media: A systematic review and critique. Television & New Media, 22(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420982230

- McGonagle, T. (2001). Wresting (racial) equality from tolerance of hate speech. Dublin University Law Journal, 23, 21–54.

- Palm-Dalupan, M. L. (2005). The religious sector building peace: Some examples from the Philippines. In G. Terr Harr & J. J. Busuttil (Eds.), Bridge or barrier: Religion, violence, and visions for peace (1st ed., pp. 225–274). Brill.

- Pellet, P. (2021). Understanding the 2020–2021 Tigray conflict in Ethiopia – background, root causes, and consequences. Kki Elemzések, 39, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.47683/KKIElemzesek.KE-2021.39

- Pohjonen, M., & Udupa, S. (2017). Extreme speech online: An anthropological critique of hate speech debates. International Journal of Communication, 11(312827), 1173–1191.

- Press Unit. (2023). Hate speech (pp. 57–80). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139042871.007

- Rowbottom, J. (2022). A thumb on the scale: measures short of a prohibition to combat hate speech. Journal of Media Law, 14(1), 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/17577632.2022.2088074

- Sonessa, W. L. (2020). Rethinking public theology in Ethiopia: Politics, religion, and ethnicity in a declining national harmony. International Journal of Public Theology, 14(2), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1163/15697320-12341609

- Steyn, R., & Hendrickx, B. (2020). The controversial Anoole and Haile Selassie monuments as reflecting the religious and political tensions between Christians and Muslim Ethiopians. Pharos Journal of Theology, 101, 1–5.

- Udupa, S. (2023). Extreme Hate. In C. Strippel, S. Paasch-Collberg, M. Emmer, & J. Trebbe (Eds.), Challenges and perspectives of hate speech research (Vol. 12, pp. 233–248). Digital Communication Research. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/86272/ssoar-2023-strippel_et_al-Challenges_and_perspectives_of_hate.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&lnkname=ssoar-2023-strippel_et_al-Challenges_and_perspectives_of_hate.pdf

- United Nations. (2020). United Nations strategy and plan of action on hate Speech: Detailed guidance on implementation for United Nations field presences. United Nations.

- Waldron, J. (2012). The harm in hate speech. Harvard University Press.

- Warner, W., & Hirschberg, J. (2012). Detecting hate speech on the world wide web. Proceeding LSM ‘12 Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Language in Social Media (LSM 2012) (pp. 19–26). http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2390374.2390377

- Workneh, T. W. (2019). Ethiopia’s hate speech predicament: Seeking antidotes beyond a legislative response. African Journalism Studies, 40(3), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2020.1729832

- Workneh, T. W. (2021). Social media, protest, & outrage communication in Ethiopia: toward fractured publics or pluralistic polity? Information Communication and Society, 24(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1811367

- Yohannes, H. (2023). The Tigray crisis and the possibility of an Autocephalous Tigray Orthodox Church. https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/handle/2066/249797