Abstract

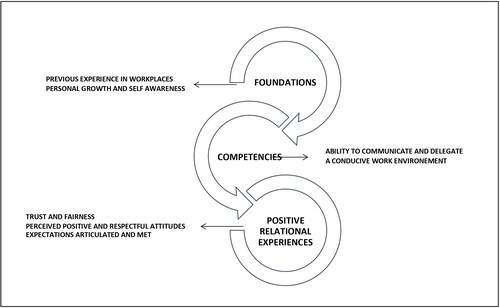

As dairy production on Irish farms increases and there is an increased demand for labor, a shift from traditional family centric employment structures to an increased dependency on hired labor outside the family is occurring. This paper presents the results of a multi-disciplinary study on farm management and dairy production from a social science perspective. In-depth narrative interviews were conducted with six employers (ER) and seven employees (EE) to explore their farm employment experiences. Three theoretical lenses (psychological contract, agency theory, and pluralist frame) were used to generate themes from the narratives in the development of a conceptual model delineating the key factors that influence employment relations. The conceptual framework includes ‘foundational aspects’ and competencies that influence employees’ and employers’ farm employment experiences. Foundational aspects are shaped by past experiences and personal growth, underpinning how farm employment is experienced by employers and employees. Competencies such as effective communication and task delegation influenced how a sense of trust and fairness were experienced and determined how the expectations of both employers and employees were met in farm employment. The conceptual model offers a clear framework demonstrating how these elements interact to shape a constructive environment for actors involved in farm employment and is of interest to policymakers and initiatives supporting farm employment in agriculture.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the dairy industry in the developed world has been characterized by a notable increase in herd size and a shift away from the traditional family run model to one heavily reliant on external labor (Barkema et al., Citation2015). The paradigm whereby family members play a significant role in assisting with the labor requirements of the farm is shifting due to various factors, such as challenges in farm succession and a growing inclination of family members towards diverse career paths (Barclay et al., Citation2007; Chiswell & Lobley, Citation2018). As reliance on family labor has diminished, the need to hire farm employees has increased. This shift has brought about challenges for dairy farmers, including difficulties in recruiting, retaining, and effectively managing the workforce on their farms (Eastwood et al., Citation2020; Mugera & Bitsch, Citation2005; Nettle et al., Citation2006). Despite changes in work productivity through mechanization and automation (Roche et al., Citation2017), there is a growing need for agricultural employees (Dufty et al., Citation2019; Ryan, Citation2023). Although the importance of employment relationships in farm management has been highlighted in previous studies (Deming et al., Citation2020; Moore et al., Citation2020; Nettle et al., Citation2011), in general, there is still limited research on managing employees external to the farm family. This study aims to increase our understanding of employment by investigating employers’ and employees’ experiences in the Irish dairy farming sector.

While labour and skills shortages are a major concern in the agricultural sector in the OECD, overall employment numbers in the sector has been decreasing (Ryan, Citation2023). From 2005 to 2020, the EU’s agricultural workforce decreased by 4.5 million people, equating to 36% of the total workforce (Eurostat, Citation2022). A declining workforce in agriculture directly impacts farmers by heightening the workload pressure on existing labor, often leading to increased stress, longer working hours, and challenges in effectively managing farm operations (Nettle et al., Citation2005; Ryan, Citation2023). Human Resource Management (HRM) supports employers’ responsiveness to the needs and preferences of employees and is vital for maintaining the existing workforce (Armstrong & Taylor, Citation2020). In some dairy sectors, such as Sweden and Australia, efforts have been made to enhance HRM practices, employment relations, and health and safety (Kolstrup, Citation2012; Nettle, Citation2018). When it comes to recruiting personnel to the agriculture sector, identified constraints include competition from other sectors (Hostiou et al., Citation2020) and a declining interest in farming among the younger generations (Beecher et al., Citation2022). Therefore, ‘people management’ is becoming increasingly important for dairy farms worldwide, including Ireland (Eastwood et al., Citation2020; Kelly et al., 2020).

The dairy industry is one of the most prominent sectors of Irish agriculture with the production of circa 8.7 billion litres of milk annually (Bord Bia, Citation2022), and is an important source of employment supporting 54,000 jobs (Ernst & Young, 2023). Irish dairy farming is characterized by small-scale family farms (relative to countries such as New Zealand and the US) operating seasonal calving pasture-based production systems (Dillon et al., Citation2005). There has been rapid growth in dairy production over the past decade (Ramsbottom et al., Citation2020) as evidenced by an increase in average herd size, from 58 cows in 2010 (CSO, Citation2020) to 93 cows in 2022 (NFS, Citation2022), necessitating more workers (Kelly et al., 2020). Growth in dairy production presents both opportunities and challenges, and people management is becoming increasingly important. There is a shift away from traditional family farms where farm labor is predominantly supplied by household members to one where external labor is increasingly required (Deming et al., Citation2018; Madelrieux & Dedieu, Citation2008; Nye, Citation2020; Ryan, Citation2023), meaning that many farmers employ staff for the first time (Stup et al., Citation2006). According to the FRS (Citation2022), almost 70% of the Irish dairy farmers surveyed required external labor for either milking duties or general farm work, and 9 out of 10 farmers expect this reliance on external labor to either increase or remain at current levels over the next three years.

All family run businesses, including dairy farms, are concerned about business tensions and relational conflicts when workers are employed from outside the family (Amarapurkar & Danes, Citation2005). Many farmers do not have formal training in employee management or struggle with HRM (Bewley et al., Citation2001). Communication between employers and employees has been identified as a success factor in farm employment relationships in previous research that explored the challenges of managing large herd sizes (Durst et al., Citation2018). A successful relationship between employees and employers can positively affect satisfaction, longevity, and recruitment (Moore et al., Citation2020). When employees and employers have a good working relationship, they are more willing to perform tasks beyond their regular duties (Deming et al., Citation2020). Conversely, poor employee relations affect business performance and result in high employee turnover (Blyton & Turnbull, Citation2004). Understanding employment relations involves analyzing interactions between different individuals or groups in the workplace (Rose, Citation2008) and to date, there is limited research on employment relationships and the experience of people working on farms (Hostiou et al., Citation2020).

The aim of this study is to explore employers’ and employees’ experiences of employment relations through an examination of narrative data. This study focuses on a sector in which farm employment is relatively new and provides insights into how norms are established. Our findings provide guidance regarding the nature of policy, education, and extension interventions that can assist in making farm employment more sustainable.

2. Theoretical framework

In examining employment relations in the Irish dairy sector, this study adopts a theoretical approach that draws upon diverse perspectives from the literature on management, agency, and psychology. The interplay between employers and employees in dairy farm workplaces necessitates a framework that accommodates various paradigms. This study integrates Fox’s frames of reference (FoR) model (Fox, Citation1966; Citation1974), which categorizes divergent viewpoints on employment relations, along with agency theory (Mitnick, Citation1975; Ross, Citation1973) and psychological contract theory (Rousseau, Citation1989). By intertwining these theoretical lenses, we can seek to understand the experiences of employment relationships of employers and employees and develop the key themes that frame these experiences.

The FoR model was first introduced by Fox in 1966 to understand employment relations. Fox (Citation1966) proposed two main ways to view employment relationships. The unitarist FoR portrays the organization as a harmonious entity, where all members share common goals and interests, and conflicts are easily resolved (Fox, Citation1966). The unitarist frame tends to align with a management-centric approach, emphasizing the importance of maintaining organizational stability and cohesion (Fox, Citation1966). On the other hand, pluralist FoR posits that the employment relationship is a negotiated, contractual relationship that exists to satisfy the interests of separate but interdependent groups and acknowledges the diverse interests and perspectives of individuals (Fox, Citation1966). The pluralist lens advocates structured mechanisms, such as collective bargaining and employee representation, to address and mediate conflicts (Fox, Citation1966). The pluralist framework facilitates an understanding of how conflicts, negotiations, and collaborations manifest among diverse actors in any industry’s employment relations landscape (Fox, Citation1966). In 1974, Fox proposed a third frame, the radical frame, which perceives the workplace as a site of inherent inequality and contends that the interests of capital and labor are fundamentally at odds (Fox, Citation1974). The radical perspective often advocates transformative change and worker empowerment to address imbalances (Fox, Citation1974). The triad within Fox’s framework provides an interrogative lens that supports a critical analysis of the nature of the environment in which experiences of employment and of employing play out. The framework is particularly useful for understanding the evolving employment environment of dairy farms in Ireland and how nascent experiences of employment are shaped by and shaping this environment.

Additionally, agency theory serves as a useful lens for investigating employment experiences within the dairy sector. Jensen and Meckling (Citation2019) put forward a management-oriented perspective of agency that highlights the potential for employees (agents) to act in self-interest (agency) while employed by ‘principals’ (employers). The interests of employers and employees do not always align (Bendickson et al., Citation2016) and agency theory recognizes how asymmetry between the interests of principals and agents influences employment relationships (Jensen & Meckling, Citation2019). It pays attention to the importance of formal and informal contracts (e.g., norms) in how the interests of involved parties shape actions and behaviors in employment relationships. In light of lack of knowledge in the area of formal employment contracts (Durst et al., Citation2018) and low levels of compliance with employment laws on Irish dairy farms (Lawton et al., Citation2021) agency theory may help in understanding the importance of informal norms in furthering actors’ interests in farm employment relationships.

The psychological contract theory examines implicit and unwritten expectations within employer/employee relationships (Rousseau, Citation1989). It encapsulates the nuanced mutual understanding of mutual obligations and perceptions of entitlements, transcending explicit forms of formal employment contracts (Rousseau, Citation1989). Human Resource Management and psychological contract researchers acknowledge the importance of context, defined as the setting that surrounds the obligations of the psychological contract in the transformation of workplace relationships (Cooke, Citation2018). This perspective is consistent with Fox’s (Citation1974) framework and provides a lens to further investigate the environmental dynamics that shape normative understandings of obligations and entitlements and to accommodate the potential for conflict and negotiation to arise, as highlighted in management perspectives on agency.

Overall, the three theories outlined provide a helpful theoretical lens to assist in the analysis of narrative interview data with employers and employees in Irish dairy farming, paying attention to the importance of context, informal and formal contracts and norms, and how different expectations arise and are played out in farm employment relationships.

3. Material and methods

Approval for this study was sought and received an exemption from the Human Research Ethics Committee of University College Dublin (reference number LS-E-20-160-Lawton) via email. Our research necessitated a method for delving into the personal experiences of employers and employees working on dairy farms. Consequently, we chose a qualitative narrative interviewing approach that is suitable for exploring participants experiences in-depth (Punch, Citation2005). Each interview participant was issued with a written consent form outlining the purpose of this research, interview details, data privacy and confidentiality. Each participant was required to sign and return this form giving their consent to participate in this study. All particpants consented that the findings of this research would be published or presented in professional meetings.

Different disciplines influence the methodological approach taken in this study. A qualitative narrative interview approach associated with the disciplines of sociology and psychology was used. The framework used for the analysis of the narrative data collected study is informed by an interpretivist approaches (focusing on individuals’ agency) using concepts from the theoretical frameworks to analyse the data and develop themes. Narrative (and particularly biographical) datasets contain rich stories of subjective experiences, which include accounts of how environmental phenomena are experienced, together with the revelation of individuality and agency. Narrative data can be comprehensively analyzed using approaches such as the seminal approach of Wengraf (Citation2011). Dean et al. (Citation2018) point to the deeper and richer analysis that can occur when a diverse research team is involved and in this case the four authors each brought their different disciplinary and methodological backgrounds to the analysis of the narratives to provide insights that will be relatable, used, and impactful in how policy, extension, and education initiatives address important HRM issues in Irish dairy farming.

3.1. Employer interviewee selection

Narrative interviews were conducted with six farm employers, who had different characteristics with respect to herd size, number of employees, age, and level of education (). Interviewees were selected from a database of 315Footnote1 farmers who participated in a survey of HRM practices conducted in 2018/2019 as a separate part of this study (Lawton et al., Citation2021). For this study, farmers were required to have at least one full-time or part-time employee (to accommodate a focus on their farm employment experiences). Therefore, based on the survey results, farmers with no employees (n = 112) and non-responses (n = 11) were excluded. The remaining 192 survey respondents had an average herd size of 149 cows, ranging from 25 to 700. Purposive sampling was used to select interviewees based on key characteristics (see ) to ensure a diverse range of employment scenarios. Responses to eight questions related to perceptions about employing people in a survey on HRM practices were also taken into consideration (Appendix A) to represent diverse views on employment (Lawton et al., Citation2021). Responses to employment-perceptions questions were based on a five-point Likert scale. These answers were converted to a numerical value and used to calculate an employment perceptions score for each farmer (Strongly Agree = 2, agree = 1, Neither Agree nor Disagree = 0, disagree = -1, or Strongly Disagree = -2). Scores ranged from +12, to -4. Two farmers were selected from the positive end of the scoring scale, two from the negative end of the scale, and two from the middle.

Table 1. Characteristics of interview participants.

The selected farmers had herd sizes ranging from 82 to 380 cows, with an average of 245 cows. The average herd size in Ireland in 2018 was 78.6 cows (NFS, Citation2018). The average age of the dairy farmers in Ireland was 52 years of age (CSO, 2021), the participants in this study had an average age of 44 yrs. years (range 25-80 yrs.). Thus, interviewees had large herds and were younger than the average Irish dairy farmers, which reflects the population of dairy farmers who hire employees. The educational level of participants ranged from QQIFootnote2 Level 3 (primary school level) to QQI Level 8 (honors bachelor’s degree). The number of employees working on the employers’ farms ranged from one to four. The interviews were conducted at home or on the farms of the interviewees. All the interviewees were male. No interviews were conducted with a female farmer, as it was challenging to find a female farmer within the selection criteria for the study. This reflects national statistics, where less than 14% of all farm holders are female, and only 7.8% of specialist dairy farms are owned by women (CSO, 2021).

3.2. Employee interviewee selection

Based on the interviews conducted with farm employers, a profile of farm employees was established, illustrating the variety of people employed on farms. Interviews were conducted with seven farm employees selected to represent diverse criteria, including employment status, age, and educational level (). None of the participants interviewed (employers or employees) had experience in working with each other. This was to ensure that employers and employees could speak freely about the knowledge that employers and employees on the farms on which they worked were not included in the study. Finding farm employees to participate in this study was more difficult than gaining access to employers. We first used purposive sampling to source employees, and when we had exhausted all avenues using that method, we then used snowball sampling to find the remaining participants by asking interviewed employees to recommend other farm employees who might be willing to be interviewed. Snowball sampling is appropriate for hard-to-find populations.

3.3. Interview method

The data were collected using narrative interviews, an approach that has been previously used to study farmer behavior and wider sociological issues in Irish agriculture (Cush & Macken-Walsh, Citation2016; Deming et al., Citation2019; McAloon et al., Citation2017; McDonald et al., Citation2014). Following Wengraf’s (Citation2011) methodology, a two-phase interview process was followed. Informed by the Biographic Narrative Interpretive Method (BNIM) (Wengraf, Citation2011), at the beginning of the interview a ‘Single Question to Induce Narrative’ (SQUIN) is posed, to elicit a narrative from an interviewee, who tells their own story, uninterrupted by the interviewer. This may be followed by a second session in which the interviewer may ask, if needed, probing questions in relation to the narrative that has been elicited. The third sub-session of interviewing, if employed, involved the interviewer asking the participant questions about unexplored topics in the latter’s original narrative.

The SQUIN used for this study, following the format set out by Wengraf (Citation2011) was: “As you know, I’m researching how people work together on farms. Can you please tell me your story of working with others? All events and experiences that were important to you. I will listen; I will not interrupt. I will just take notes in case I have any questions after you have finished. Please take your time. Begin wherever you like.”

In sub-session two, once the participant elicited their narrative in response to the SQUIN, the interviewer used probing questions to guide the interviewee for Personal Incident Narratives (PINs) (Wengraf, Citation2011). PINs describe specific events and experiences that have occurred in interviewees’ lives, which they recall and narrate in detail. PINs were particularly rich sources of information for identifying the details and substances of important and significant experiences for the interviewees. All interviewees participated in the second part of the two-phase interviews. A third interview session was not conducted in this study. For research ethics purposes, interviewees were issued a participant information sheet that explained the research objective and consent form. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and anonymized for analysis. The average duration of the 13 interviews was 94 minutes, ranging from 51 minutes to 237 minutes.

3.4. Data analysis

Data were evaluated using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Thematic analysis can be effectively used to identify, analyze, and report patterns on themes within interview data (Jackson & Bazeley, Citation2019). Members of the multi-disciplinary research team read the transcripts to familiarize themselves with the material and actively participated in reading and synthesizing the narrative data. The authors met regularly to discuss thoroughly, reflect on and interpret the data, fostering a collaborative approach to analyze complex narratives. Reflective thematic analysis is a qualitative research approach that emphasizes the critical role of reflexivity throughout the research process which involves researchers actively engaging with their own biases, assumptions, and perspectives, recognizing how these factors influence the interpretation of data (Saunders et al., Citation2019). This approach encourages a continuous process of self-reflection and critical examination, enabling authors to challenge taken-for-granted assumptions and consider alternative perspectives (Dean et al., Citation2018; Saunders et al., Citation2019). Consistent with the thematic analysis approach, we first analyzed the data using each of the three theoretical lenses separately. Subsequently, we examined how these lenses intersect and interact, to provide a holistic understanding of the factors influencing employment relations in the agricultural context. The collective analysis involved a collaborative effort between the four authors to analyze the narrative data from diverse perspectives through dialogue, synthesis of findings, and peer review, integrating insights, identifying patterns, and refining interpretations iteratively. It emphasized transparency, rigor, and the leveraging of collective expertise to enhance the credibility and depth of the analysis. Applying theoretical lenses to the discussion of the data allows us to develop topics/points of emphasis/themes that were iteratively refined. Thematic analysis was selected due to its ability to identify patterns across individual participant stories enabling researchers to uncover similarities, differences, and nuances in experiences or perspectives. This approach contributes to theory development by refining existing frameworks and/or generating new hypotheses, while also offering practical insights. Throughout the inductive coding early on, sub-codes were also developed, which assisted in exploring thematic patterns in the data (Punch, Citation2005) and intersections between patterns. Overall, the process of coding and sub coding helped to guide the identification of the main themes under which the data could be organized and presented.

4. Results

By interrogating the narratives through the three chosen theoretical lenses (the psychological contract, agency theory, and pluralist frame), we sought to gain insight into the intricacies of employment relations and factors influencing and shaping employment relationships on Irish dairy farms. Insights are presented under themes developed in the thematic analysis process as follows. Data pertaining to employers and employees are presented under each theme, illustrating their sometimes diverging and converging perspectives and experiences in relation to the themes. presents a highlight of results.

Table 2. Highlights of themes identified which impacted on employment relationships.

4.1. Foundations of good employment relations

Two themes were developed from the narrative data as foundations that underpin good employment relationships, shaping the dynamics and expectations that employers and employees have. Previous experiences in the workplace and personal growth and self awareness were found to form the foundations of good employment relations. Employers who had diverse professional backgrounds or family legacies in farming tended to emphasize collaboration and the development of structured systems. Employees compared their current jobs with past experiences, influencing their satisfaction and perceptions. This aligns with psychological contract theory, as both parties shape their expectations based on past experiences influencing their views and interactions.

4.1.1. Previous experiences in workplaces

Previous employment relationships and experiences recurred in narrative interviews with both employers and employees. Employers reflected on their individual experiences, be it as former employees or through family legacies, and how this shaped their perspectives and strategies in managing their employees. ER1 explained why he valued the diversity of knowledge and skills and the need for collaboration and partnership:

‘I was a professional in another sphere for a long time, working in groups that were intricate and worked well together. And different expertise coming from different directions and making sure that you were an expert in one direction, but you needed four other experts in their field that were able to contribute into the system you’re working. So, for me it was logical to come back and try creating that system on the farm. So, basically whether it’s the guy who does the steel fittings, whether it’s the vet, whether it’s your guy who’s an expert on heating water, I don’t believe or want to be an expert or leader in everything.’ ER1.

Interviewees who had grown their farming operations and increased their number of employees explained their journeys from taking stewardship of their farm to developing a vision for change and then seeking to implement it with their employees. In the case of ER1, the transition to working with (or hiring) employees prompted a specific vision for change, which was centered on the implementation of a streamlined farming system.

‘So many things that weren’t happening…best practice wasn’t happening. So basically, I had to come in and try to change that. And it was a slow thing to change. And if I’d come back as a 20 yr old or a 21 yr. old or 22 yr. old, I shudder to think what I would have done because I wouldn’t have had the knowledge or the where of it all or the self-confidence or experience.’ ER1

Employers interviewed with experience of working elsewhere consistently emphasized the use of a straightforward farming system that was clear and comprehensible for everyone involved. These employers also prioritized a structured approach so that all employees understood the tasks required to accomplish farm goals. For instance, it was perceived that a transparent system and defined roles contribute to a more efficient and harmonious employer-employee dynamic.

‘I worked in Australia with R and N so they would have a pretty good reputation out there…they had massive clarity on the farming system that they wanted to run. There was no deviation from it…I suppose they were very good at…they just set out the system that never changed. If you ever had a question in your mind, you kind of always knew the answer because they just stuck to it, they had a way in their head of doing things and that’s the way everything revolved around that.’ ER5.

This employer now seeks to ensure that he has a clearly defined farming system in which employees have clarity. By establishing clear systems and roles, the employer promotes a unified approach to farm operations, fostering cohesion and reducing conflict.

Many of the interviewed employees evaluated their current work environment against their past experiences. In the following example, the employee reflects on their current farm job by comparing it with their past job in a retail setting. The narrative data showed how employees’ past experiences shaped their perceptions of their current job and overall job satisfaction.

‘My old job was a bit easier I think. But yeah, so the good thing about my job now I suppose, it’s not dealing with people coming into the shop everyday wanting this, wanting that and being contrary or whatever…But it’s nice to be at the farm. I like the job.’ EE12.

4.1.2. Personal growth and self-awareness

The interviewees highlighted the importance of employers recognizing their individual needs in relation to preferred working conditions and those that reflect personal/family circumstances and career aspirations. Employees appreciated when employers had a genuine concern for their well-being and satisfaction

‘I like being finished early just so I can get home because of my situation at home…where I work now, he (the farmer) is happy to see us out of the yard as early as we can. So, we’d start milking cows at three o’clock in the evening whereas other farms I know, they’re not starting milking until half four, five o’clock and sure it’s seven o’clock by the time they’re leaving the yard.’ EE1.

This reflects the psychological contract, in particular the implicit agreements and expectations between employers and employees. When employers demonstrate concern for employees’ personal circumstances and accommodate their needs, it fosters a positive psychological contract, enhancing job satisfaction and loyalty.

The interviewees recognized the importance of engaging their employees in decision-making processes and operational improvements in relation to the farm. By affording employees the opportunity to contribute their ideas and propose more efficient approaches to tasks, employers foster a culture of innovation and continuous improvement. This collaborative environment also enriches the psychological contract by aligning individual interests with the collective success of dairy enterprises.

‘I’ve kind of a policy this last couple of years, if I’m doing a job and it could be done 2 ways, (for example) if we’re bedding this shed with straw and that shed with straw, I might say which one do you think we should do first or which way would you think we should. And if he says then I think we should do it, I’ll let him do it his way within, if it’s not changing the outcome of the job I’ll let him do the job the way he thinks it should be done and I find that fellas are kind of more satisfied at the end of the day if they think they’ve had a bit of input and responsibility.’ ER4.

This example of a collaborative approach enriches the psychological contract. When employees feel their opinions are valued and their contributions matter, it reinforces their commitment to the farm’s goals, reducing the potential for conflict and increasing overall job satisfaction.

4.2. Competencies for good employment relations

A person’s ability to communicate and delegate were found to be key competencies for fostering good employment relations. Employers and employees with good communication skills tended to create a more cohesive and motivated workforce. An employer who had the ability to delegate tasks to employees empowered them in their roles and increased trust and overall job satisfaction. Good communication and delegation resonates with agency theory, which stresses the importance of clear communication and alignment of goals to minimize conflicts and enhance productivity.

4.2.1. Ability to communicate and delegate

When employers were able to effectively address employee needs and concerns, employees were more likely to identify with the farm’s interests. By fostering open communication and promoting inclusivity, farmers can align their workforce with a common business purpose. When the interviewed employers succeeded in creating a cohesive and unified workplace, where collective interest and goals were emphasized, a unitarist approach emerged with greater emphasis on shared organizational values and common goals. The quote below is from an employee who identified with the goals of the farm business, speaking of how ‘we’ carry out farm tasks.

‘We’d always be trying to make things more efficient like. With roadways, with the cows and stuff, we’d make them more efficient for them walking on it, we took all the bends out of it. We did a lot of maintenance on it.’ EE1.

Both the employees and employers emphasized the importance of communication in fostering a healthy and productive working relationship. By actively listening, employers can understand employee experiences and aspirations, and create an inclusive environment in which collaboration and cooperation thrive. The interviewed employees highly valued routine meetings and opportunities for discussions. In one case, using a WhatsApp group and rosters facilitated better communication and coordination among team members, promoting a sense of inclusivity and teamwork.

‘We would have set up a WhatsApp group between us. You know between the lads, the three of us working on Farm A. Like communication is really important. We would have done up rosters, you know just a case of making up a template in excel and everyone’s name appeared in a different colour, so you know your days on and days off…you have these things that will happen sporadically like your TB test or milk recording or someone calling or whatever. And you know we all need to be there, there’s something big going on.’ ER5.

Open honest communication creates an atmosphere of trust in which feedback can easily be given.

‘That everybody is, there’s nobody talking behind others backs, there’s none of that nonsense going on, you’re up front, you tell the fella or the girl what you think is being done wrong or whatever and she the same…Rather than going home in bad humour and its festering into something that’s going to end up with them leaving, talk about it, talk about it, have a window to talk about things like this’. ER4. In another example, one employer asked for an employee’s opinion regarding a large capital investment project and because of that, the employee felt a sense of pride and value. ‘We talked about the parlour a lot. Because he’s either extending our herringbone or putting in a rotary. But obviously it’s a big investment and he’s humming and hawing. So, we talked about it a lot and he actually asked me too. Because I milked in a rotary in America before.’ EE9.

Delegation is key in any employment relationship, and clear communication is a contributing factor to the success of delegation. A clear delegation of responsibilities ensures that employees know what is expected of them and where they fit into the operations of the farm. Effective delegation empowers employees to perform their duties efficiently.

‘I was shown the machinery, and I was shown how to drive the machinery. I was shown what way the cows came in and out of the place, how the milking machine worked and everything, and that was it then, I was just left there to do it.’ EE1.

When delegation is not conducted effectively, employees can be left uncertain and frustrated. Frustration can further escalate if employees cannot meet expectations because of a lack of guidance or appropriate resources. In the following case, the employee was frustrated by the employer’s inability to delegate.

‘It was like everyone did the weanlings, okay stop, everyone go get the cows, okay stop, everyone do the cows. It was so annoying.……that’s partly a reflection on him but I think it’s because he just can’t let it up like, he’s so insecure in himself. And maybe it’s the stress of the whole situation. But he’s also a very nervous character, like in general.’ EE2.

4.2.2. Work environment

Creating a conducive work environment emerged as a key theme in all the interviews. Employers with smaller herd sizes were more likely to invite employees into their homes for meals, whereas those with larger herd sizes and more employees generally transitioned away from this practice. Interviewed employers with larger herd sizes believed that it was important to provide decent facilities for employees and protect family privacy.

‘I think from my mother’s stage and my wife’s, right, the day is now gone to feed employees in the house. And it took a little while for that to adjust with me because it was tradition for years on so many farms and maybe it still is in some’. ER4.

The interviewees acknowledged the importance of having appropriate facilities to optimize employee performance and achieve farm goals. Employers prioritized the provision of adequate facilities combined with training to enable employees to execute their tasks effectively and align their efforts with the broader objectives of the farm. By investing in the physical and operational infrastructure that supports task completion, employers adhere to agency theory principles, aiming to minimize the costs associated with inefficiencies and suboptimal performance, ultimately fostering a mutually beneficial relationship between the employer and employees.

‘So, I actually believe in a combination of getting on well with the staff but having facilities, whether it’s the milking parlour or the machinery that they work in a good environment.’ ER4.

Equally, the employees interviewed appreciated good facilities. One employee described how one farmer that they worked for and admired had really thought about how to set up his farm for ease.

‘I’ve milked there for four or five years. But like he spent money on the place, he measured the place, and he spent time in it like. He’d drive you demented sometimes the amount of time he spends picking out his dinner in the shop or anything and the same with the (milking) parlour. But he thinks ahead like…the place itself now that anyone could walk in that morning there and, you know, start.’ EE2.

Interviewees perceived poor organizational skills to signify the employer’s lack of respect for their employees. Poor organization can lead to confusion, affecting the productivity and morale of employees.

‘Lack of organisation is a lack of respect for the person coming in, is the way I see it now. You know, I’m giving up my time, fair enough you’re paying me for it, but I’m going to do the best I can here for these two hours or whatever it is. And it should work both ways. Like if I’m good enough to turn up on time and make an effort to leave your yard the way I found it, it’s only fair that you’d be decent enough and organised enough to be polite and helpful and show me how you want things done rather than giving out to me when I don’t do them your way.’ EE2.

This relates to the psychological contract theory where employees expect a certain level of organization and respect from their employers. When these expectations are not met, it can lead to dissatisfaction and decreased motivation.

4.3. Relational outcomes

From the narratives it was possible to pick out three key themes that were considered as indicative of positive employment relationships.

4.3.1. Trust and fairness

Trust and fairness were important to both the employers and employees. The interviewed employers trusted employees who would take ownership of their actions and be honest when admitting mistakes or reporting incidents. When this occurred, it reinforced a sense of trust and integrity within the employer-employee relationship, reflecting psychological contract theory. One employer told of an incident where an employee was not upfront about a mistake, but how he used the opportunity to make the expectation of honest communication explicit.

‘I say to A “A did you forget to tell me something yesterday?” “no”, well said I “there’s a post out there lying on the ground that was standing up yesterday morning, you know what about that”, “oh yeah, oh yeah that”. “You were on the phone, were you?”, “yeah, I was on the phone”…Anyway, in the heel of the hunt I told her no matter what she broke the next day or any day in the future tell me straight up. So, she did’. ER4

Employees appreciated and valued when employers shared information about the farm business with them as it signified trust in the person, aligning with agency theory by promoting transparency and reducing information asymmetry. This allowed employees to understand the economic/operational aspects and challenges faced by the farmer. This transparency enhances a sense of trust and shared purpose and improves employee commitment and motivation.

‘If I wanted to do it, I could do it and the farmer would let me. Like he’d always bring out the books for the bulls and he’d ask you “ah pick which ones you’d want to use” and I don’t know, he just does it for the sake of doing it, I’d say, for the students and stuff like that. But the attitude of the farmer that I work for now, if you had an opinion about anything like, you could take it to him, and he’d point you in the right way or he’d tell you, you were wrong. But there’d be no hard feelings about it like.’ EE1.

The interviewees emphasized the significance of fair treatment in all aspects of their employment, which is consistent with a unitarist frame of reference that stresses harmony and a shared interest in fair treatment and equitable workload distribution.

‘He sees what a person is capable of. And yea he gives a thought of what a person could actually do. If a person can be relied on and, based on that, he’s making a decision.’ EE4.

When everyone’s needs are considered and met, everyone has a sense of equitable sharing of workload, which promotes a positive employment relationship. The employers who had more experience in managing employees were very much aware that new employees in particular required close attention and training early in the relationship to ensure that tasks were completed effectively. These employers understood that inadequate task completion not only disrupts farm operations but can also lead to frustration and conflict.

‘If they go in milking, I’d bring them in and show them the milking parlour. And then before that introduces them to R, the milker and R would know he’s to be looked after. Within a week I’d be saying to R “how is he getting on?”. And generally speaking, the chap would be, most of the time, flying’. ER4.

4.3.2. Positive and respectful attitudes perceived

Both employers and employees perceived that the attitude of the other person played a pivotal role in shaping their employment relationship. An empathetic, respectful, and constructive attitude from the employer fosters a positive and supportive work culture, encouraging open dialogue and collaboration, aligning with psychological contract theory.

‘Like he’s always calm, like he won’t go mad or crazy or anything. Like he’s calm, like he will keep a cool mind, like he will figure out the things. He will figure out the solution, like he won’t be panicking, or anything like. And as well like even after a hard day, he does understand that for example, if we have done a lot of jobs, he understands we did a lot on that day. So, and yea, always he’s, he doesn’t forget to tell thank you, like and that’s quite a quite good for the staff. Because like I worked in other places and stuff and the attitude from the managers and stuff just have been s***e.’ EE4.

Conversely, a perceived negative or autocratic attitude leads to misunderstanding and negatively influences employee morale and satisfaction.

‘I couldn’t work with him because of his attitude, the way he was speaking to people. He spoke to everyone like that. If he had a problem with anyone, even lorry drivers or anyone that came into the yard, he’d just f******g flip on them.’ EE1.

The employers interviewed valued employees with a proactive and optimistic attitude that contributed to a harmonious work environment, motivating employers to invest additional effort in the employer-employee relationship, reflecting a unitarist frame of reference.

‘Pay them well, give them their time off and a bonus at Christmas. Any time he was in trouble financially, a number of times I’ve had to give him money because there was something came up, his wife crashed the car and the insurance had gone through the roof and stuff, out of the blue stuff…I didn’t actually think ever it was over and above, you know because of the nature of the chap, he had a heart of gold. And I think that’s what brings that out in people. If they see goodness in an employee or fairness in an employee they’re going to respond accordingly’. ER4. Conversely, when the employer perceives a negative attitude, it is difficult to overcome. ‘I didn’t like their attitude towards me, which I suppose…probably stayed with me with my own relationship with employees. After that I feel you have to treat people fairly’. ER3.

4.3.3. A functioning psychological contract

The psychological contract emerged in all interviews, but was more pertinent among employers and employees working with smaller herd sizes. The close-knit setting may have fostered greater reliance on the psychological contract. Throughout the interviews, both employers and employees had expectations from one another. Employers expected employees to be enthusiastic and have a positive attitude towards their work, farm, and farmer. When expectations are met, their relationship is strengthened, and the employer’s sense of reciprocal responsibility to employees is reinforced. However, ambiguous or poorly communicated expectations have resulted in conflict and frustration. Without the explicit articulation of roles, responsibilities, and performance criteria, misunderstandings arose, leading to discord and dissatisfaction for both parties.

‘He milked one evening for us…I was at a wedding. He left the gate open at the top so the first row of cows went out, walked out, so (they) were standing in the yard eating a bit of silage and he rang me, “what will I do?”. I’m in Kerry, get them back in like you know, what do you want me to do like. He just didn’t have that initiative or whatever, and you can’t teach that.’ ER2.

The employees interviewed expected to have adequate equipment to carry out their duties on the farm. When the equipment was not available, it led to frustration, a breakdown in trust and cooperation, impeding productivity, and increasing dissatisfaction. The example shows an employee’s frustration with the employer’s perceived meanness about a small item (handles on electric fences) not in place.

‘I’m terrified of electric wires. Like it’s a small thing but I don’t like them at all. Now I know they’re a necessary evil, but I wouldn’t be a fan of getting shocks like. And…he’s tight like (farmer does not/is slow to invest in equipment)….But every handle for the strip wire was a bit of baler twine and some of them were fine and some of them very not fine. So, I’d be going round with my boot trying to kick them up off the stake and then with a small stick trying to put them back over it. Like that just drives me absolutely mad.’ EE2.

The results underscore the critical role of effective communication and delegation in enhancing farm productivity and employee satisfaction, aligning with agency theory principles. Trust and fairness emerged as fundamental to maintaining a harmonious work environment, resonating with the psychological contract theory by emphasizing the importance of meeting mutual expectations. Additionally, the attitudes of both employers and employees significantly influenced the quality of their relationship, reflecting the frames of reference theory by illustrating the impact of managerial style on employee morale and cooperation.

5. Discussion

With limited literature regarding people working in agriculture (Hostiou et al., Citation2020), this study provides valuable insights into the area of employment relations within the agricultural sector, specifically focusing on dairy farms in Ireland. Nettle et al. (Citation2001) highlighted that for a successful working relationship on a dairy farm, it is necessary for employers and employees to be aware of the factors influencing the relationship, especially with the decline of the agricultural workforce across Europe and elsewhere (Dufty et al., Citation2019; Ryan, Citation2023). There is a need to focus not only on the discrete perspectives of employers and employees, but also on the relationships between them, and this study contributes to understanding how dynamics between employers and employees on dairy farms are currently being shaped. The results of this study allowed us to propose a conceptual model that describes the foundational elements and critical competencies essential for creating successful employment relations between employers and employees in the Irish dairy industry (). The foundational elements required for a successful outcome include a dynamic process of learning from past experiences, self-awareness, and personal development, without which employers and employees struggle to adapt to the changing needs of each other. Effective people managers hone their key competencies, such as effective communication, delegation, and the establishment of a conducive work environment to ensure positive relational outcomes. Both competencies and foundational elements serve as pillars influencing positive relational outcomes, encompassing mutual trust, a sense of fairness, clear expectations, and positive attitudes. The model describes the dynamic process of employment relations and how foundational elements and competencies synergistically contribute to fostering harmonious and effective working relationships between employers and employees.

5.1. Relational outcomes

Relational outcomes refer to the quality and nature of the interactions between employers and employees. Key relational outcomes identified in this study include trust, fairness, clear expectations, and positive attitudes. These positive relational outcomes are what can be expected when both employers and employees bring positive foundations to the employment relationship and have the competencies for good communication.

Our findings suggest that as dairy farmers grow their operations and scale of employment, there is a move from largely relying on the psychological contract towards embracing more formal principles akin to those of agency theory. Initially, with fewer employee numbers, the psychological contract plays a central role, where mutual expectations are implicitly understood (Rousseau, Citation1989). As farms grow and develop employers invest more in training, align employee goals with farm objectives, and seek to stabilise their workforce, reflecting agency theory’s principles. In this shift to more formalised management, a sense of trust and fairness is critical in maintaining positive employment relationships. When employees felt trusted and fairly treated, their job satisfaction and morale significantly increased, consistent with previous research (Cable & Graham, Citation2000; Herscovitch & Meyer, Citation2002). The pluralist FoR comes into play, especially in larger farms with more employees, where recognising and valuing diverse employee needs and perspectives becomes more important. Employers who become effective managers are seen to draw from their own experiences, learn from both successes and challenges, and enhance their self-awareness. This continuous reflection and learning behavior helps employers create a harmonious work environment, minimize conflicts, and optimize productivity and satisfaction for all.

This study found that a functioning psychological contract is essential to ensure successful employment relationships. According to the psychological contract, both employers and employees have expectations of each other (Rousseau, Citation1989) and in this study, past employment experiences influenced these expectations, and when expectations were not met the relationship suffered. When employees’ expectations were not met or when duties were not adequately communicated or delegated, employees experienced frustration with their employers, impeding trust, cooperation, productivity, and job satisfaction on the farm. Employee expectations mostly focused on payment, general treatment by employers, and work-life balance, which concurs with the findings of Nettle et al. (Citation2005).

Under the psychological contract, trust between employers and employees is essential for creating a sustainable, meaningful relationship (Rousseau, Citation1989). In this study, all employees highly valued being trusted and treated fairly, which increased their job satisfaction and morale. Previous research also found that treating people well improves job satisfaction and morale (Guest, Citation2016). In any business, the quality of relationships between employees and employers can be measured by the level of trust developed between them (Sadia et al., Citation2016). Trust and a sense of fairness allow both employers and employees to work in harmony and without fear of reprisal if either party makes a mistake or makes a poor decision. Employers who build and maintain trust, as well as ensure fairness in their interactions with employees, recognize that such efforts not only contribute to immediate positive outcomes such as increased job satisfaction and morale but also lay the foundation for sustained, mutually beneficial relationships that can enhance overall farm success and resilience in the long term.

More experienced employers were more comfortable and more inclined to trust employees with tasks and responsibilities and allow them to prove themselves. In line with agency theory, experienced employers invest more in training and development, aligning their employees’ goals with the farm’s objectives (Mitnick, Citation1975; Ross, Citation1973). This delegation of responsibility not only benefited employers by allowing them more time off but also improved their work-life balance, enhancing the attractiveness of a career in dairy farming. Employees interviewed in this study appreciated when employers discussed farm business details with them, leading to increased trust, shared purposes, and positive attitudes. Deming et al. (Citation2020) also found that when farmers are open with their employees, trust between them increases.

This study identified that when each person demonstrated a positive and respectful attitude, it formed the foundation of a good employment relationship, resulting in a supportive work culture and open dialogue. Developing good employment relationships is a dynamic process. We suggest that future research explore interventions or strategies that foster open communication and positive relationships between employers and employees, contributing to a more harmonious and productive work environment on dairy farms.

5.2. Foundations of positive employment relations

Foundational elements are the underlying attributes and processes that support the development of competencies which lead to positive relational experiences. The ability to take positive lessons from past experiences, personal growth, and self-awareness emerged as foundational elements for both employers and employees realtionships. Employers who reflected on and learned from their experiences could better address the diverse needs of their workforce, leading to enhanced job satisfaction and a positive work environment (Christensen Hughes & Rog, Citation2008; Torrington et al., Citation2014). The pluralist frame recognizes that employers and employees have different needs and interests that need to be addressed if HRM is to be robust and sustainable (Mahapatro, Citation2022; Van Buren, Citation2022; Vance, Citation2006).

Employers managing larger herds with more employees showed greater self-awareness and commitment to continuous learning. This enabled them to understand and meet their employees’ needs and aspirations more effectively, promoting respect, inclusivity, and personal development. Recognizing the moral obligation to consider employees as valuable contributors, employers who foster a culture of self-awareness and continuous learning can create supportive and thriving workplaces (Nettle et al., Citation2011). Our findings highlight the importance of cultivating a culture of self-awareness and continuous learning for employers to foster thriving and supportive workplaces. Agricultural extension agencies should use the findings of this study to develop training programs to increase the self-awareness of people working together.

5.3. Competencies for good employment relations

Competencies are the specific skills and behaviors that effective people managers need to develop to foster positive employment relationships. This study identified several essential competencies, including effective communication, delegation, and the creation of a conducive work environment. Effective communication facilitates mutual understanding, resolves conflicts, and builds trust (Cush & Macken-Walsh, Citation2016; Thomas et al., Citation2009). This study highlights the value of routine meetings and opportunities for discussion, which foster an inclusive workplace culture. Prioritizing these communication skills is essential for retaining a workforce and enhancing workplace relations (Deming et al., Citation2020), in line with the pluralist frame, which values diverse perspectives.

Delegation involves entrusting employees with responsibilities, which empowers them and aligns their actions with the businesses objectives (Cournut et al., Citation2018; Walton, Citation1985). Clear delegation of responsibilities ensures that employees understand their roles and tasks, leading to increased job satisfaction and efficiency (Hesse et al., Citation2017). Conversely, vague or insufficiently guided delegation frustrates employees, highlighting the need for clear and effective delegation methods. This practice reflects agency theory principles, where clear roles and expectations enhance efficiency and satisfaction. This study found that more experienced employees appreciated autonomy and understood their significance in achieving farm goals. When delegation of tasks was not done correctly or communicated vaguely without sufficient guidance, the employees were frustrated. Lack of guidance, organization, or appropriate resources hindered employees from meeting their employer expectations, exacerbating frustration. The implications of these findings highlight the importance of clear delegation in promoting employee understanding, empowerment, and satisfaction in farm businesses. Future research could investigate strategies for enhancing delegation in farming contexts to optimize work efficiency and employee satisfaction.

In this study, both employers and employees acknowledged the essential role that a conducive work environment with appropriate facilities plays in achieving a positive employment relationship. Farm facilities are linked to attracting and retaining employees (Groome, Citation2019) and enhancing labor efficiency (Bewley et al., Citation2001; Hogan et al., Citation2022). Employers recognized their responsibility to provide a conducive work environment. Their investment in farm facilities is aimed at creating a supportive atmosphere for employees and reducing inefficiencies. Future research could explore how providing suitable facilities, particularly in larger farming operations, impacts employee attraction and retention in dairy farming, while also examining methods to improve overall workplace well-being.

This study provides a detailed snapshot of employment relationships within Irish dairy farms, identifying the foundations and competencies necessary for positive relational experiences. Our findings highlight the transition from reliance on the psychological contract to the principles of agency theory and ultimately employers adopting pluralist approach to managing employees as farmers expanded operations and developed their management skills. While this study offers valuable insights into the employment dynamics on Irish dairy farms, future research should explore strategies to foster open communication, improve delegation methods, and provide suitable facilities to enhance workplace well-being. One limitation of this study is the small sample size inherent to the BNIM methodology, which may not be statistically representative. A longitudinal study, similar to Nettle et al. (Citation2005), could provide additional and diverse insights.

6. Conclusion

Managing employment relationships on dairy farms has taken on greater importance as farms transition away from dependence on family labor and towards the employment of staff, in a context where recruitment and retention of staff is challenging. This study provides valuable insights into employment relationships within Irish dairying farming, highlighting the key factors influencing these relationships from an employee and employer perspective.

This study identified that foundational factors for good employment relationships are shaped by experiences of both employers and employees and how they have used these past experiences for learning, growth, and self-improvement. This learning helps with an appreciation of the needs and perspectives of employees and supports the development of competencies such as the ability to communicate and delegate. This in turn leads to positive relational outcomes demonstrated through high levels of trust between employers and employees, where expectations are clearly articulated and both parties perceive positive problem-solving attitudes from each other. Trust and communication are important for building sustainable positive relationships in the workplace.

Employers who provided development opportunities for their employees were more likely to be those who had really reflected on and learned from their own previous experiences as both employees and employers. Experience has also shaped employee expectations. When these expectations are not met, they have a detrimental effect on the relationship.

This study highlighted that, for working relationships to be experienced positively, clear communication, alignment of expectations, trust, and positive attitudes are required to build a work environment conducive to productivity, job satisfaction, and long-term commitment.

Author contribution statement

Thomas Lawton: Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Project administration. Monica Gorman: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - review and editing, Supervision, Project administration. Áine Macken-Walsh: Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing - review and editing. Marion Beecher: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

oass_a_2378135_sm3523.docx

Download MS Word (21.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thomas Lawton

Thomas Lawton is a PhD candidate at University College Dublin. He has a Bachelors of Business Studies and a Master of Business from Cork Institute of Technology. His research interests focus on human resource management and employment relations within agricultural workplaces.

Monica Gorman

Monica Gorman is Associate Professor in agricultural extension and innovation in UCD’s School of Agriculture and Food Science. She holds a Bachelors of Agricultural Science, Masters in Agricultural Science and PhD from UCD. Her research interests focus on agricultural extension such as trust in farmer/advisor relations and agricultural education such as identifying strategies for engagement of students in agricultural education and competency development for agricultural extension and education.

Áine Macken-Walsh

Áine Macken-Walsh is a Senior Research Officer at Teagasc’s Rural Economy and Development Programme (REDP). She is a sociologist, using narrative and action research methodologies to explore farmers’ and other actors’ subjective values, knowledges and practices. She works in transdisciplinary contexts, addressing societal challenges relating to diverse issues such as human cooperation, gender, animal health, climate change, and the bioeconomy. She uses sociological insights and participatory methods to support multi-actor co-design of policy and extension interventions. She holds a BA Sociology & Political Science (NUI, Galway), MA Human Rights and Democratisation (Padova) and PhD Sociology (NUI, Galway).

Marion Beecher

Marion Beecher is Research Officer at Teagasc, Animal & Grassland Research and Innovation Centre Moorepark, Fermoy Co. Cork. Marion has a Bachelor of Agriculture Science, and PhD both from University College Dublin. Marion’s research interests focus on dairy farm labour productivity and efficiency Labour efficient technologies, e.g. infra-structure, facilities and practices and work organisation and human resource management within dairy farm businesses.

Notes

1 From 6,668 farmers who granted permission for their details to be made available for research purposes, 520 farmers were selected (based on herd size and location, to be representative of dairy farmers in Ireland) and 315 completed the survey (Lawton et al., Citation2021).

2 Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) is the Irish state agency responsible for maintaining the National Framework of Qualifications (NFQ) in Ireland.

References

- Amarapurkar, S. S., & Danes, S. M. (2005). Farm business-owning couples: Interrelationships among business tensions, relationship conflict quality, and spousal satisfaction. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 26(3), 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-005-5905-6

- Armstrong, M., & Taylor, S. (2020). Armstrong’s handbook of human resource management practice. Kogan Page.

- Barclay, E., Foskey, R., & Reeve, I. (2007). Farm succession and inheritance – comparing Australian and international trends. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. https://hdl.handle.net/1959.11/4072

- Barkema, H. W., von Keyserlingk, M. A., Kastelic, J. P., Lam, T., Luby, C., Roy, J. P., LeBlanc, S. J., Keefe, G. P., & Kelton, D. F. (2015). Invited review: Changes in the dairy industry affecting dairy cattle health and welfare. Journal of Dairy Science, 98(11), 7426–7445. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2015-9377

- Beecher, M., Ryan, A., & Gorman, M. (2022). Exploring adolescents’ perceptions of dairy farming careers in Ireland: views of students studying agricultural science in secondary school. Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research, 61(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15212/ijafr-2022-0008

- Bendickson, J., Muldoon, J., Liguori, E., & Davis, P. E. (2016). Agency theory: the times, they are a-changin. Management Decision, 54(1), 174–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-02-2015-0058

- Bewley, J., Palmer, R. W., & Jackson-Smith, D. B. (2001). An overview of experiences of Wisconsin dairy farmers who modernised their operations. Journal of Dairy Science, 84(3), 717–729. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74526-2

- Blyton, P., & Turnbull, P. (2004). The dynamics of employee relations. Palgrave Macmillan. https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/32423

- Bord Bia. (2022). Vision for the Irish dairy sector. Retrieved January 29, 2024, from https://www.bordbia.ie/industry/irish-sector-profiles/dairy-sector-profile/.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cable, D. M., & Graham, M. E. (2000). The determinants of job seekers’ reputation perceptions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(8), 929–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200012)21:8%3C929::AID-JOB63%3E3.0.CO;2-O

- Chiswell, H. M., & Lobley, M. (2018). It’s definitely a good time to be a farmer: Understanding the changing dynamics of successor creation in late modern society. Rural Sociology, 83(3), 630–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12205

- Cooke, F. L. (2018). Concepts, contexts, and mindsets: Putting human resource management research in perspectives. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12163

- Cournut, S., Chauvat, S., Correa, P., Santos Filho, J. C. D., Diéguez, F., Hostiou, N., Pham, D. K., Servière, G., Sraïri, M. T., Turlot, A., & Dedieu, B. (2018). Analysing work organisation on livestock farm by the work assessment method. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 38(6), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-018-0534-2

- CSO. (2020). Statistical yearbook of Ireland 2020 - dairy farming [Online]. Central Statistics Office. Retrieved October 29, 2023, from https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-syi/statisticalyearbookofireland2020/agri/dairyfarming/.

- Cush, P., & Macken-Walsh, Á. (2016). The potential for joint farming ventures in Irish agriculture: A sociological review. European Countryside, 8(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1515/euco-2016-0003

- Dean, J., Furness, P., Verrier, D., Lennon, H., Bennett, C., & Spencer, S. (2018). Desert island data: An investigation into researcher positionality. Qualitative Research, 18(3), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794117714612

- Deming, J., Gleeson, D., O’Dwyer, T., Kinsella, J., & O’Brien, B. (2018). Measuring labour input on pasture-based dairy farms using a smartphone. Journal of Dairy Science, 101(10), 9527–9543. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-14288

- Deming, J., Macken-Walsh, Á., O’Brien, B., & Kinsella, J. (2020). ‘Good’ farm management employment: Emerging values in the contemporary Irish dairy sector. Land Use Policy, 92, 104466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104466

- Deming, J., Macken-Walsh, Á., O’Brien, B., & Kinsella, J. (2019). Entering the occupational category of ‘Farmer’: new pathways through professional agricultural education in Ireland. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 25(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2018.1529605

- Dillon, P., Roche, J., Shalloo, L., & Horan, B. (2005). Optimising financial return from grazing in temperate pastures. In Utilisation of grazed grass in temperate animal systems (pp. 131–147). International Grassland Congress. https://doi.org/10.3920/978-90-8686-554-3

- Dufty, N., Martin, P., & Zhao, S. (2019). Demand for farm workers: ABARES farm survey results 2018. Australian Bureau of Argicultural Resource Economics and Science, research report, Canberra, 1447–8358. https://doi.org/10.25814/5d803c3de3fad

- Durst, P. T., Moore, S. J., Ritter, C., & Barkema, H. W. (2018). Evaluation by employees of employee management on large US dairy farms. Journal of Dairy Science, 101(8), 7450–7462. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-14592

- Eastwood, C. R., Greer, J., Schmidt, D., Muir, J., & Sargeant, K. (2020). Identifying current challenges and research priorities to guide the design of more attractive dairy-farm workplaces in New Zealand. Animal Production Science, 60(1), 84–88. https://doi.org/10.1071/AN18568

- Ernst and Young. (2023). Economic contribution of the dairy processing industry to the Irish economy and the processor’s forecasts to 2030. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwj3xdjdw-WDAxVNS0EAHXEjBQsQFnoECCgQAQ&url=https%3A//www.ibec.ie/-/media/documents/media-press-release/economic-contribution-of-the-dairy-processing-industry-to-the-irish-economy–processor-forecasts-to.pdf%3Fla%3Den%26hash%3DE713F8336121CF9EA175E4EBE1602A32&usg=AOvVaw3l9Qs3zDLXKoT98UFP3FHu&opi=89978449.

- Eurostat. (2022). Farmers and the agricultural labour force - statistics [Online]. Eurostat. Retrieved October 28, 2023, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Farmers_and_the_agricultural_labour_force_-_statistics#Agriculture_remains_a_big_employer_in_the_EU.3B_about_8.7_million_people_work_in_agriculture.

- Fox, A. (1966). Industrial sociology and industrial relations: an assessment of the contribution which industrial sociology can make towards understanding and resolving some of the problems now being considered by the Royal Commission. H.M.S.O.

- Fox, A. (1974). Beyond contract: Work, power and trust relations. Faber & Faber.

- FRS. (2022). Research report on the outlook of external farm labour support in Ireland. Farm Relief Service. Retrieved January 16, 2024, from https://www.frsnetwork.ie/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/FRS-Farm-Labour-Report-2022-Online-spread-final.pdf.

- Groome, S. (2019). Profiling dairy farm employers and employees. What characterises a satisfactory employment relationship? [Master’s thesis]. University College Dublin.

- Guest, D. E. (2016). Trust and the role of the psychological contract in contemporary employment relations. In P. Elgoibar, M. Euwema, & L. Munduate (Eds.), Building trust and constructive conflict management in organisations. Industrial relations & conflict management. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31475-4_8

- Herscovitch, L., & Meyer, J. P. (2002). Commitment to organizational change: extension of a three-component model. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 474–487. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.474

- Hesse, A., Bertulat, S., & Heuwieser, W. (2017). Survey of work processes on German dairy farms. Journal of Dairy Science, 100(8), 6583–6591. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-12029

- Hogan, C., Kinsella, J., O’Brien, B., Gorman, M., & Beecher, M. (2022). An examination of labour time-use on spring-calving dairy farms in Ireland. Journal of Dairy Science, 105(7), 5836–5848. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2022-21935

- Hostiou, N., Vollet, D., Benoit, M., & Delfosse, C. (2020). Employment and farmers’ work in European ruminant livestock farms: A review. Journal of Rural Studies, 74, 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.01.008

- Hughes, J. C., & Rog, E. (2008). Talent management: A strategy for improving employee recruitment, retention and engagement within hospitality organizations. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(7), 743–757. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110810899086

- Jackson, K., & Bazeley, P. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (2019). Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure. Corporate Governance. Gower.

- Kelly, P., Shalloo, L., Wallace, M., & Dillon, P. (2020). The Irish dairy industry - Recent history and strategy, current state and future challenges. International Journal of Dairy Technology, 73(2), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0307.12682

- Kolstrup, C. L. (2012). What factors attract and motivate dairy farm employees in their daily work? Work (Reading, MA), 41 Suppl 1, 5311–5316. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-0049-5311

- Lawton, T., Gorman, M., Kinsella, J., Markey, A., & Beecher, M. (2021). A study of human resource management practices on Irish dairy farms. International Symposium on Work in Agriculture. . Retrieved June 14, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marion-Beecher/publication/377108344_A_study_of_Human_Resource_Management_practices_on_Irish_dairy_farms/links/659572436f6e450f19c88a0c/A-study-of-Human-Resource-Management-practices-on-Irish-dairy-farms.pdf.

- Madelrieux, S., & Dedieu, B. (2008). Qualification and assessment of work organisation in livestock farms. Animal: An International Journal of Animal Bioscience, 2(3), 435–446. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175173110700122X

- Mahapatro, B. B. (2022). Human resource management. PG Department of Business Management. New Age International Pvt Ltd.

- McAloon, C. G., Macken-Walsh, Á., Moran, L., Whyte, P., More, S. J., O’Grady, L., & Doherty, M. L. (2017). Johne’s disease in the eyes of Irish cattle farmers: a qualitative narrative research approach to understanding implications for disease management. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 141, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2017.04.001

- McDonald, R., Macken-Walsh, Á., Pierce, K., & Horan, B. (2014). Farmers in a deregulated dairy regime: Insights from Ireland’s new entrants scheme. Land Use Policy, 41, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.04.018

- Mitnick, B. M. (1975). The theory of agency: The policing paradox and regulatory behaviour. Public Choice, 24(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01718413

- Moore, S. J., Durst, P. T., Ritter, C., Nobrega, D., & Barkema, H. W. (2020). Effects of employer management on employee recruitment, satisfaction, engagement, and retention on large US dairy farms. Journal of Dairy Science, 103(9), 8482–8493. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2019-18025

- Mugera, W. A., & Bitsch, V. (2005). Managing labour on dairy farms. A resource based perspective. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 8, 79–98. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.8140

- Nettle, R. (2018). International trends in farm labour demand and availability. In Moorepark dairy levy research update international workforce conference (pp. 8–16). Teagasc.

- Nettle, R., Paine, M., & Petheram, J. (2001). Dairy farm employment relationships and the challenge to the work of extension. The Regional Institute Ltd. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from http://www.regional.org.au/au/apen/2001/non-refereed/NettleR.htm.

- Nettle, R., Paine, M., & Petheram, J. (2005). The employment relationship - a conceptual model developed from farming case studies. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 30, 19–35.

- Nettle, R., Paine, M., & Petheram, J. (2006). Improving employment relationships: Findings from learning interventions in farm employment. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 31, 17–36.

- Nettle, R., Semmelroth, A., Ford, R., Zheng, C., & Ullah, A. (2011). Retention of people in dairy farming – what is working and why? Gardiner Foundation.