Abstract

In this study, we categorized art collectors based on their motivations to purchase contemporary artworks in the Japanese art market. Applying the 14 art purchase motivations proposed by Zolfagharian and Cortes, we conducted a large-scale quantitative online survey and clustering analysis, which resulted in identifying four types of Japanese contemporary art collectors (balanced/harmonious, geek, immature, and intelligent). The characteristics of each type were examined in terms of purchasing behavior and psychographic characteristics and analyzed using a regression model, then their impact on the art market was quantified. As a result, we concluded that the intelligent type of art collector not only drives a larger amount of art consumption in the Japanese contemporary art market but also leads to the innovative image of collectors’ diversity values. It is also noted that immature collectors are important because they can be promoted to become the intelligent type. This paper is the first study to explore the purchase motivations of the Japanese contemporary art collectors based on the large-scale quantitative data which include detailed psychographic characteristics. In addition to find the four art collector types, we examine their economic and innovative value for developing practical solutions to expand the Japanese art market.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Despite a short-term downturn due to COVID-19, the global art market continues to expand (McAndrew, Citation2023). However, the trading volume of the Japanese art market has been staying low. Because of the lack of accurate statistical data on the industrial structure, the Japanese contemporary art market has not been fundamentally studied. Thus, this study aims to clarify the situation surrounding contemporary art in Japan, particularly the types and characteristics of Japanese contemporary art collectors. To further explore the problems facing the Japanese contemporary art market, we categorize the psychographic characteristics of consumers who have purchased contemporary artworks in Japan based on their motivations for purchasing, in addition to examining their market values and revealing a part of the black box nature of the Japanese art market. As it would be outside the scope of this study to discuss the definition, the term ‘contemporary art collector’ is practically defined as ‘a person who has purchased artworks by living artists at least once and has purchased artworks more than once’, and the judgment of whether those works are considered ‘artworks’ or not depends on the subjects (the art collector in this study) reporting the purchase.Footnote1

This study examines, firstly whether the framework for evaluating the motivations to purchase artworks presented by Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) can be applied to contemporary art collectors in Japan through qualitative research and interviews.Footnote2 We then, secondly conducted a large-scale online quantitative survey and a clustering analysis with consideration of psychographic and lifestyle characteristics, in addition to demographics, such as gender and age.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. After reviewing previous research in Section 2, we present the framework for this research. Section 3 reports the research method of the quantitative survey, and Section 4 presents the results for four types of contemporary art collectors identified by a clustering analysis on purchasing motivations. Then, we discuss the results of each type of artwork purchasing behavior and verify the factors affecting purchase decisions using a multivariate linear regression analysis in Section 5. Finally, we conclude the importance of each type of collectors to enlarge the Japanese contemporary art market.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Japanese art market

The European Fine Art Foundation (Citation2017, p. 205) stated that ‘Japan’s large share of the world’s art trade has not re-emerged to the extent that it was at the end of the 1980s, over the past quarter of a decade’. It also noted that Japan does not play a major role as a seller or buyer in the global art market. Since fundamental data, such as the number of galleries in the Japanese art market are difficult to obtain, annual worldwide art market reports by Deloitte and ArtTactic (2019) considered the Asian region limited to South and Southeast Asia, particularly China and India, without any mention of the Japanese art market from a financial perspective.

Although there are few surveys and reports on the Japanese art market, Watae (Citation2014) conducted a survey on art buyers’ attributes, purchase amounts, purchase purposes, purchase channels, and first purchase intentions, and estimated the art purchase experience rate in Japan to be 12.1%. He found that art buyers’ age, household income, and individual income showed significant correlations with their purchase experience rate, and suggested that buyers who start purchasing art at their younger age tend to buy more expensive artworks. However, all of its results were limited to presenting superficial aspects of Japanese art buyers, without examining their detailed characteristics.

ART FAIR TOKYO,Footnote3 the largest art fair facilitator in Japan, conducted a large-scale market survey on the purchase of artworks and art-related items in 2020. The results of the survey showed that only 16.0% of Japanese people purchased artwork in all categories, with 4.2% of the purchase experience being of contemporary art. In particular, the rate of purchased art within the past three years was 5.4%, and the purchase rate of contemporary art was 1.6%. It was also found that the purchase rate was higher among men and those in their 30s. Furthermore, the total art market volume in Japan was estimated at 236.3 billion yen (∼1.8 billion USD). They also reported that the artwork genre of the Japanese art market sales consisted of western-style paintings (18.0%), Japanese-style paintings (16.3%), ceramic arts (14.8%), scroll pictures/folding screens (10.4%), and craftworks (10.1%), whereas the contemporary arts were accounted for 17.4% of the whole market in 2020. The report also noted that the unique aspect of the Japanese art market was that department stores have played as one of the important trading channels, which ran up to 22.4% of all the channel sales, compared with art galleries, 37.9% as the largest channel. However, the scope of their study was limited from a macro perspective and did not reveal any analysis of the actual situation of specific artwork buyers.

2.2. Studies of the motivation for artwork purchase behavior

Studies of the motivation of consumers’ purchase behavior have typically started from McClelland’s four categories: achievement, affiliation, power, and uniqueness/novelty (McClelland, Citation1955, Citation1961; McClelland et al., Citation1953). However, several studies have suggested that it is difficult to apply these four classifications directly to art consumption behavior (Hirschman & Holbrook, Citation1982; Joy & Sherry, Citation2003; Schindler & Holbrook, Citation2003). Moreover, art consumption behavior through art galleries and auctions is frequently considered similar to risky sports consumption (Arnould & Price, Citation1993; Bourriaud et al., Citation2002; Celsi et al., Citation1993; Hopkinson & Pujari, Citation1999; Richins, Citation1994). Recent studies focus on investigating the collectors’ motivations at their entry points, they suggest that the community and social values through personal relationship with artists and other collectors may be one of the important motivation to become a sophisticated art collector (Kossenjans & Buttle, Citation2016; Lazzaro et al., Citation2015; Rojas & Lista, Citation2022). But they conducted only the qualitative interview survey for the limited number of art collectors.

In this study, we apply the approach of Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) based on the motivation similarities between risky sports consumption behavior and art consumption behavior. They proposed a holistic framework comprising seven motivations for purchasing artworks, compared with the other studies which investigated only a part of the motivations and obtained fragmented results. In the following sections, we will examine each of the seven motivations and discuss whether those can be applied in this study for Japanese art collectors.

2.2.1. Economic motivations

In the 1960s and the 1970s, art consumers were considered to be motivated by the economic value of art to diversify their financial portfolios by adding art as an investment (Bates, Citation1983; Keen & Norman, Citation1971; Rush, Citation1961; Stein, Citation1973). On the other hand, Stein (Citation1973) verified using mathematical models that oil paintings are not as financially attractive as other investment products. In addition, Mandel (Citation2009) analyzed price changes in art investments over the last 50 years and reported that the returns on art investments have been lower than those on other financial investments. Other comparative studies of economic returns with other investment products have also failed to provide evidence of the superiority of art investment (Angello, Citation2002; Bates, Citation1983; Ekelund et al., Citation2000; Flores et al., Citation1999; Rengers & Velthuis, Citation2002). Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) found that among the economic motivations for art consumption, the motivations for value appreciation and values preservation of the art were stronger than those regarding the economic value and diversifying capacity of the art. They also concluded that art consumers who purchased expensive artworks had a stronger economic motivation for value appreciation.

2.2.2. Normative motivations

Studies of the risky sport consumption have revealed that consumers’ major motivations for the risky sports at the first challenge were the need and pressure for ‘compliance’ with others (Celsi et al., Citation1993). Moreover, group polarization led to increased risk acceptance in the context of group decision (Celsi et al., Citation1993; Wallack et al., Citation1962; Winter, Citation1973). Referring to the above, Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) indicated that high-value art consumers had stronger motivations for social acceptability and group identification.

2.2.3. Uniqueness motivations

The motivation to achieve substantial or symbolic differentiation can trigger consumers to obtain goods in general. Therefore, the stronger the social and cultural ties among consumers, the stronger their motivation to establish a firm identity in their society or groups. Although Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) applied these findings to art consumption, they did not find correlations between the amounts of consumers’ spending on artworks and the magnitude of the motivation regarding self-identity of the art. Thus, we will not apply the uniqueness motivations of art further for our analysis of the Japanese art market in this study.

2.2.4. Hedonic motivations

Many studies of the consumer behavior of the risky sports have identified motivational factors for hedonic consumption, such as enjoyment, self-expression, communitas, addiction, danger, competition, thrill, pleasure, and flow (Celsi et al., Citation1993; Hopkinson & Pujari, Citation1999). Moreover, Joy and Sherry (Citation2003) found aesthetics, immersion, and fantasizing as factors associated with the hedonic consumption of art. Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) conducted a focus group survey and found that aesthetics, pleasure, immersion, and captivation were highly related to the hedonic motivations for art consumption, with the first three motivations being more prevalent among frequent art buyers.

2.2.5. Intellectual motivations

From the medieval era, the main consumers of performing arts have been those among the royalty and aristocracy with high intellectual and cultural levels (Andreasen & Belk, Citation1980). Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) assumed that this also applies to the purchase of contemporary artworks. They classified three intellectual motivations for art collecting: curiosity, history (the desire to explore elements of works associated with specific historical characters, events, and facts), and culture (the desire to explore the backgrounds of works containing information or symbols of cultures), and reported that only the motivation for culture was significantly stronger among consumers who frequently purchased artworks.

2.2.6. Good cause motivations

Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) regarded art purchases as a bidirectional exchange of values, unlike donations which are unidirectional gifts from donors to recipients, in which consumers purchase artworks for some economic value and provide support for a specific artist or an art genre in return. Nevertheless, in the same survey, no significant correlation was found between the amount of art purchases and the strength of good-cause motivations.

2.2.7. Harmony motivations

Art consumption behavior encompasses the desire for harmony with nature and communion, which is synonymous with separation from ‘civilization’ (Arnould & Price, Citation1993). Although Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) analyzed whether harmony motivations lead to an increase in art consumption, such as the frequency and number of artworks purchased, they did not find significant correlations among them.

The overview of the above studies of art purchase motivations in the existing literature and this research is summarized in . No existing studies have considered all the above seven purchase motivations other than Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011). In this study, we will not treat the uniqueness motivation by itself but will regard it as a component of normative motivations along with motivations for social acceptance and group identification. Furthermore, we will take Japanese art collectors’ purchasing behaviors and their psychographic characteristics into account, which will enable us to examine their economic and innovative value for developing practical solutions to expand the Japanese art market.

Table 1. Overview of prior research on the art purchase motivations.

3. Research method

We conducted a large-scale quantitative survey and an analysis using an Internet panel to categorize the types of Japanese contemporary art collectors and examined the psychographic and lifestyle characteristics of each type. The survey was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Dissertation Committee of Keio University (ref.#: 002592330KEI01-3210) for studies involving humans. All the participants collected written informed consent online from participants before the survey. We applied the framework of Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) and the results regarding three types of Japanese contemporary art collectors derived from our former interview survey and qualitative research included in the Online Supplement. It is noted that our research was not a hypothesis-testing study, but an exploratory research. Due to the limitation of available information and data about the Japanese art collectors, we could not construct specific assumptions on their artwork purchase behaviors, in advance. However, we had an assumption that the artwork-purchasing motivations between European and Japanese art collectors would be similar. In fact, we have replicated the same motivation values as those of the previous studies which have used European subjects by a factor analysis in our former qualitative research. Then, we tried exploratorily classifying the Japanese contemporary art collectors into construable subcategories based on the common artwork purchasing motivations by applying a hierarchical cluster analysis for a large-scale quantitative survey.

3.1. Quantitative survey of Japanese art collectors

The survey was conducted in two phases: a pre-survey and a main survey. The pre-survey included about 10,000 panelists associated with an Internet research company. There were ∼400 subjects who had purchased artworks created by living artists more than once in the past 10 years and who had purchased multiple artworks more than once, regardless of whether they were by living artists. Furthermore, 16 subjects were excluded due to zeros in their purchase frequencies and purchase amounts in the last five years. Thus, 386 subjects remained for further analyses.Footnote4 The survey was conducted as follows. However, the details of the pre-survey are not listed because of space limitations.

Survey period: 12–17 July 2017

Selection conditions: Those who have purchased artworks created by living artists in the past 10 years and have purchased at least two artworks.

Analyzed subjects: 386 (male: 234; female: 152/average age: 51.7)

Survey questions: Gender, occupation, education, marital status, residence status, individual annual income, household income, age when purchasing the first artwork, reasons for the first purchase, attributes of purchasing artworks in the past five years, annual average purchase amount in the past five years, annual average purchase frequency in the past five years, information sources at the time of purchasing artworks, attributes of artists’ information when purchasing artworks, information diffusion behavior after purchasing artwork, motivations at the time of purchasing artworks, psychographic characteristics, needs for interaction with artists

As in , a median household income of the analyzed subjects was between 3-5million yen (∼20K–33.3K USD), which was consistent with the statistics of the whole Japanese population. A median annual purchase amount of artworks was between 30,000 and 100,000 yen (∼200–667 USD) and a median artwork purchase frequency was 1–3 times per year. ART FAIR TOKYO also reported the same result that the largest volume of artwork buyers (71% of their 24,959 subjects) purchased <100,000 yen in 2021. Based on these descriptive statistics, the analyzed subjects were not high-end art collectors who have frequently bought extremely expensive artworks, but they were general art collectors with an average level of living among all the Japanese consumers. Note that the questionnaire about psychographic characteristics included 10 items regarding social awareness, lifestyle awareness, information sensitivity, and outlook on life. In addition, details of the survey questions regarding art purchase motivations are presented later in .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of analyzed subjects.

Table 3. Results of multiple comparisons of purchasing motivations in each cluster pairs.

3.2. Categorizing contemporary art collectors

We conducted a hierarchical cluster analysisFootnote5 using the WARD method on the 386 samples by all the 14 purchasing motivations as the non-transformed indicators described above and found four clusters: Clusters 1, 2, 3, and 4 contained 179, 50, 68, and 89 subjects, respectively. A chi-square test was performed to examine the differences in the ratios, showing statistical significance (χ2 = 101.938, df = 3, p < .001). As the goodness of fit measures for the cluster analysis, the within the sum of square measure of the clusters distances seemed to be flattened after the fourth cluster and the optimal number of clusters was four based on the Gap statistic. Then, we conducted a one-way analysis of variance with the four clusters as independent variables and purchase motivations as the dependent variables. We then performed multiple comparisons using Tukey’s HSD method (5% significance level).

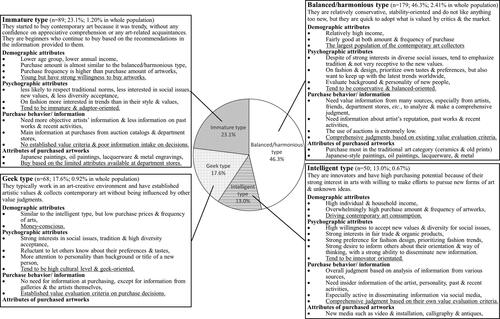

The multiple comparisons results showed that Cluster 1 (n = 179) had high average scores on all the purchasing motivation questions and was presumed to correspond to the ‘balanced/harmonious type’ in our former qualitative research resultsFootnote6 in the Online Supplement; Cluster 2 (n = 50) had high average scores for questions on intellectual motivations and normative motivations, presumably corresponding to the ‘intelligent type’ in the former results; Cluster 3 (n = 68) had lower average scores on questions about hedonic consumption motivations, economic motivations, and normative motivations, and was estimated to correspond to the ‘geek type’ in the same above. On the other hand, we concluded that Cluster 4 (n = 89) was an unknown type that did not appear in our former qualitative research, and had features of low average scores on overall motivation questions and relatively high economic motivations, especially in terms of E-VP (a motivation for value preservation as an economic value). We now proceed with further examination of these four clusters regarding their attributes related to demographics, purchasing behaviors, and psychographic characteristics.

4. Data analysis and results

For the four clusters obtained above, the following analyses were conducted to identify their detailed characteristics.

4.1. Analysis of demographic attributes

A one-way analysis of variance and multiple comparisons using Tukey’s HSD method were performed with age as the dependent variable and the previously mentioned four clusters as the independent variables. For the other categorical dependent variables, namely gender, marital status, residential area, and residence type, multiple comparisons were also performed by residual analysis after conducting a chi-square test. No differences were found among the clusters in terms of gender, marital status, area of residence, or residence type; however, in terms of the average age, Cluster 4 (unknown type) was significantly lower than Cluster 1 (balance/harmonious type) and Cluster 3 (geek type) at the 95% significance level. The average age of each cluster was 55.1, 50.2, 52.7, and 45.1 for Clusters 1 (balanced type), 2 (intelligent type), 3 (geek type), and 4 (unknown type), respectively.

Subsequently, a one-way analysis of variance was performed using individual annual income and household annual income as dependent variables and the four clusters as independent variables, and multiple comparisons were performed using Tukey’s HSD method. In terms of average personal income, Cluster 2 (intelligent type) was the highest, and Cluster 1 (balanced/harmonious type) tended to be relatively high, but there were no significant differences among clusters. In terms of average household income, Cluster 2 (intelligent type) was higher than Cluster 4 (unknown type) at the 95% significance level.

4.2. Analysis of purchasing behaviors

In the same way as the above, a one-way analysis of variance was performed with the four clusters as independent variables and the averages of the annual purchase amount and purchase frequency of artworks in the last five years as dependent variables. Then, multiple comparisons among them were performed using Tukey’s HSD method. Both the average purchase amount and purchase frequency were significantly higher in Cluster 2 (balanced/harmonious type) than in the other clusters. In Cluster 4 (unknown type), the purchase frequency tended to be higher than in Cluster 1 (intelligent type), but the purchase amount did not.

A chi-square test and residual analysis were then conducted, using the attributes of artworks purchased in the last five years as the dependent variable and the four clusters as the independent variables. Cluster 2 (intelligent type) tended to have considerably high purchase ratios across artwork attributes, especially works with relatively new styles of art, such as photography, drawing, sculpture, video, and installations. Compared to Cluster 3 (geek type) and Cluster 4 (unknown type), Cluster 1 (balanced/harmonious type) tended to purchase more Japanese paintings, oil paintings, ceramics, lacquerware, calligraphy, and antiques, but less photography, drawing, and sculpture, regarded as being more conservative. In contrast, Cluster 3 (geek type) and Cluster 4 (unknown type) were more likely to purchase fewer artworks in the past five years than the other clusters.

Similarly, a chi-square test and residual analysis with the four clusters as independent variables for each question item of the important information sources at the artwork purchase including the 14 items (gallery, auction company catalogs, department stores, magazines, newspapers, art purchase consultants, artists, collector friends, critics, the Internet, social media, friends and acquaintances, family and relatives, and none) as the dependent variable, were conducted. Cluster 2 (intelligent type) actively utilized the overall resources of information gathering for purchases, such as auctions and collector friends, which suggests that this type of cluster has a deeper commitment to art through aggressive information-gathering approaches to art purchasing. Cluster 1 (balanced/harmonious type) had a strong tendency to focus on interpersonal information sources, such as friends and acquaintances, artists, and information from department stores, which suggests a preference for information intake (information exchange) as a part of interpersonal relationship building over information from newspapers, magazines, and the Internet. Cluster 3 (geek type) was likely to deny information when purchasing artworks, suggesting a preference for contact with limited information resources, such as galleries and the artists themselves. Following Cluster 3, Cluster 4 (unknown type) was the second highest in terms of denying the need for information, and fewer needs for information from galleries, which was the main source of information in other clusters, stressing a relatively limited number of information sources, such as department stores and art purchase consultants.

Subsequently, we conducted a chi-square test and a residual analysis with the four clusters as independent variables and 13 attributes of artists’ information (age, hometown, education, awards, past works, gallery affiliation, recent activities, fame, humanity, communication skills, presentation skills, others, and no information needed) as the dependent variable. There was a high tendency for all clusters to seek objective information on artists, such as their education and awards. However, the need for information related to the artists’ production activities, such as past works and recent activities, was particularly emphasized in Cluster 1 (balance-oriented type) and Cluster 2 (intelligent type); moreover, the need for information on the artist’s personality, such as the artist’s humanity and communication skills, was significantly higher in Cluster 2 (intelligent type). The overall need for artist information was the lowest in Cluster 3 (geek type), with very little interest in the objective evaluation of artists, showing a slight tendency to value information on recent activities and past works. This may reflect the fact that Cluster 3 (geek type) had already acquired some knowledge and basic information on artists or artworks of their interest. Similar to Cluster 3, Cluster 4 (unknown type) did not need information about artists; however, it showed a low need for subjective information on artists, such as past works and recent activities, and higher needs for objective information on artists, such as age, education, and awards. This suggests that Cluster 4 (unknown type) may consist of immature art collectors who have not acquired detailed information and an objective evaluation of the artist before purchasing the artworks since such buyers tend to require only basic information about the artist due to limited information-collecting ability.

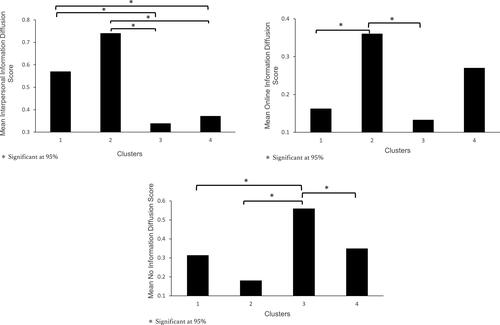

Finally, a one-way analysis of variance was performed with the four clusters as independent variables, with art-orientation questions, such as purchased artworks, art appreciation, love for art, and information dissemination behaviors as dependent variables, and Tukey’s HSD method was used for multiple comparisons. We used three categories of information dissemination behaviors: in-person diffusion to friends and acquaintances, online diffusion via social media/blogs, and other diffusion-oriented behaviors. We found that Cluster 1 (balance-oriented type) and Cluster 2 (intelligent type) were more active in information dissemination behaviors after purchasing artworks. In addition, Cluster 2 (intelligent type) and Cluster 4 (unknown type), which included younger people, had a relatively positive attitude toward information diffusion online. A summary and other results on information diffusion behaviors are illustrated in .

4.3. Analysis of psychographic characteristics

A one-way analysis of variance was performed with the four clusters as independent variables and the psychographic characteristics as dependent variables. The mean values of each motivation for each cluster and the significant results of multiple comparisons using Tukey’s HSD method are presented in . Overall, the average scores of Cluster 2 (intelligent type) were the highest on almost all psychographic characteristic questions. Furthermore, Cluster 1 (balance-oriented) showed differences from the other two clusters. Considering the social awareness attributes, Cluster 2 and 3 were generally more interested in social issues regardless of whether they are relevant and in learning about new ways of thinking and values. Thus they were more tolerant of diversity and had a higher desire for acceptance of diversity. Whereas, Cluster 4 had lower scores on the social awareness attributes, especially the lowest acceptance of social norms. In terms of their lifestyle attributes, although there was no difference in the financial sense of purchasing behaviors, Cluster 2 and 3 were more likely to prioritize their sense of fashion and design in their shopping. Cluster 2 tended to find organic and fair-trade lifestyles more attractive than other clusters. Cluster 2 was also more likely to share new information with others than to ask for it from others in terms of the information sensitivity attribute. For the interactions-with-others attributes, Cluster 3 tended to want people to know their own thoughts and preferences and tended to care more about people’s personality than their background when meeting for the first time, while Cluster 4 focused more on their background; Cluster 1 and 2 cared about both in a balanced way. A summary of the results for psychographic characteristics is shown in .

5. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the characteristics of the four clusters obtained in the above-mentioned quantitative analysis in a comprehensive manner and compare them with the collector types obtained in our former qualitative research. We summarize and illustrate the characteristics of the four types of Japanese contemporary art collectors in .

5.1. Discussion of the four types of contemporary art collectors

Cluster 1 (n = 179) showed balanced and high values for all aspects of art purchase motivations, corresponding to the balanced/harmonious type obtained in our former qualitative research. This type of collectors may represent a unique aspect of the Japanese contemporary art market since they tend to rely on sales personnel of department stores for buying artworks. In fact, compared to the other countries, the artwork sales volumes through the department stores are almost equivalent to those of galleries in Japan (see ART FAIR TOKYO reports).

Cluster 2 (n = 50) had high scores for intellectual and normative motivations, corresponding to the intelligent type obtained in our former qualitative research. The analysis of variance with economic motivations as independent variables and the four clusters obtained in the quantitative survey as independent variables showed no significant difference at the 95% level. However, regarding economic motivations, there was a little discrepancy between the results of the quantitative analysis and our earlier qualitative research.

Cluster 3 (n = 68) had high hedonic consumption motivations and low scores in economic motivations and normative motivations. Thus, we determined that this cluster corresponds to the geek type obtained in our former qualitative study.

Cluster 4 (n = 89) featured low values for art purchasing motivations in general and relatively high scores for economic motivations, especially the E-VP motivation in . Moreover, this cluster did not appear in the qualitative results. Compared to the other types, art collectors belonging to this cluster were younger, and their main sources of art information at purchase were solely through market channels, such as department stores and auction company catalogs. In addition, there was a strong tendency for a need for objective evaluation information regarding artists, and little need for information about the artist’s productions, such as past works and recent activities, that was emphasized by the other types. Because of these atypical results as contemporary art collectors, we presume that collectors of this type have not yet established their own judgment criteria for purchasing contemporary artworks. The results of the psychographic characteristics analysis also suggested that they were immature as contemporary art collectors. Although their average annual purchase amount was not as high as that of the intelligent type, it was at the same level as the balanced type, with a tendency to purchase many relatively low-priced artworks. Therefore, this type of collector may become a promising buyer of artworks and cannot be ignored as a factor in the future growth of the Japanese contemporary art market.

5.2. Verifying art purchasing factors of the four types of contemporary art collectors

Finally, for each of the four categories of contemporary art collectors, a multivariate linear regression analysis was conducted to investigate the factors associated with their purchase of artworks. The dependent variable was the frequency of purchasing artworks per year by each art collector type, and the explanatory variables were such factors as triggers for the first purchase, genre of the purchased artwork, important information sources at the purchase, important attributes of artist information, attitude toward information dissemination, psychographic characteristics, purchase motivations, and demographic information. The results showed that all the clusters except the balanced type had a high degree of fit in terms of the R-squared and adjusted R-squared. The normality of our dependent variables was validated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and the Shapiro-Wilk statistics, since all the p-values were more than .05. lists the results of the standardized regression coefficients from the multivariate linear regression analysis of the art-purchasing factors for each collector type.

Table 4. Results of multivariate linear regression analysis of factors for purchasing artworks in each cluster (standardized partial regression coefficient).

These results were consistent with those described in the analysis of purchasing behavior in Section 4.2. However, for the balanced and immature types, factors of life stage changes, such as job change, occupation, marriage, and childbirth, were significantly associated with the frequency of purchasing artworks, while for the intelligent type, gifts for others were significantly related to purchase frequency. In terms of collectors’ demographic attributes, in the intelligent and geek types there was a relationship between an academic background of graduating from art schools and the frequency of purchasing artworks. We also found that the frequency of art purchasing was higher among those with professional (possibly design-related) occupations in the intelligent type. In summary, the most effective factors for each collector type were as follows: ceramic artworks of the purchased genre (.275) for the balanced type, art consultants of the information source (.737) for the intelligent type, collector colleagues of the information source (.906) for the geek type, and triggers of the first purchase as job-change (.402), childbirth (.396), and wedding (.390) for the immature type.

As we noted above, for the intelligent type, with the highest purchase frequency and purchase amount, showed a tendency to be significantly influenced by the information from art consultants at the purchase. As an empirical marketing implication, galleries and auctioneers may effectively use art consultants to transmit art-related information to promising art collectors of the intelligent type. In addition, the results also revealed the importance of the communication skills of the artists themselves, which suggests that creating more opportunities for the interaction of collectors and artists may be effective in increasing the purchase of artworks.

6. Conclusions and further research

Since the Japanese contemporary art market has not been fundamentally studied, this research is the first study to explore the purchase motivations of the Japanese contemporary art collectors based on the large-scale quantitative survey. We verify the purchase motivation framework of Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) for the Japanese art collectors and find it applicable through minor revisions. Then based on the results of analyzing the quantitative data, we conclude that Japanese contemporary art collectors can be categorized into four types according to their motivations for purchasing artworks: balanced/harmonious, intelligent, geek, and immature types. We find that art collectors in the intelligent type drive a large amount of art consumption and are the core consumers in the Japanese contemporary art market, not only in terms of their outstanding purchasing amount and frequency but also through the innovator image with which they may lead the Japanese art market by exemplifying their diversity values and communicating in the society. These social and community values are also found in recent studies (Kossenjans & Buttle, Citation2016; Rojas & Lista, Citation2022). In spite of playing an important role in the contemporary art market, the intelligent type collectors in this study made up only 13.0% among Japanese contemporary art collectors, which is estimated to be less than ∼0.67% of the entire population in Japan. Therefore, it is necessary first and foremost to increase the number of intelligent collectors to ensure the future growth of the contemporary art market. In addition, we may also need to motivate balanced-type collectors, who also have enough purchasing power to support the market of traditional artworks, to purchase more contemporary artworks as well. Finally, some of the immature type collectors can be promoted to become the intelligent type, since they are relatively younger and on the way to learning the diversity value of contemporary art. We speculate that it may be effective to let the immature type collectors know about fundamental information of artists and galleries, such as where and when they can see artworks and interact with artists, through the internet and the social networking services, since they are currently not pay much attention to those fundamental information. Although it will be one of our future research directions, it can be expected to serve as an entry point to arouse their intellectual curiosity about the contemporary art and turn them into the intellectual type collectors.

We have realized that this study has several limitations. More detailed analyses of the psychographic characteristics of each type are needed to implement effective marketing measures for the growth of the contemporary art market, and thus more detailed analyses of the psychographic characteristics of each type are needed. In addition, although we conducted a large-scale quantitative survey of art purchase motivations and categorized art collectors in the Japanese contemporary art market for the first time, we could not develop an entire picture of the collectors’ art purchasing road map from the trigger of their initial purchase of artworks to the motivating and inhibiting factors to keep purchasing artworks for each type of contemporary art collector. Therefore, a longitudinal survey should also be necessary in the future. Since we focused on studying the motivations for artwork purchase behavior, it might be limited to apply our results and those motivation values only to investigate related product categories, such as purchasing art goods (art accessories, postcards, etc.) or collecting hobbies (antiques, trading cards, etc.).

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Dissertation Committee of Keio University (ref.#: 002592330KEI01-3210) for studies involving human participants.

Author contributions

Yuki Wasano was mainly involved in the conception and design, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the drafting of the paper; and the final approval of the version to be published. Hiroshi Onishi contributed to the conception and design, the additional analysis and interpretation of the data; the revision of the draft critically for intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. We ensure that all listed authors meet the criteria for authorship as per the ICMJE guidelines.

Online Supplement_240112.docx

Download MS Word (37.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants in the 2nd Meeting of Art in Business Workshop 2020 and the 6th Marketing Conference 2017 at Waseda University, Japan Marketing Academy for providing insightful comments on this paper. Also we are grateful to Associate Professors Tomohiko Nakao, Masahiko Maeda, Keita Nishimura and other professors for their insightful guidance in the Course of Arts Management, Department of Aesthetics and Science of Art, Keio University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Hiroshi Onishi, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yuki Wasano

Yuki Wasano is currently working as an Art communicator/Medical Doctor. She graduated from the Faculty of Medicine, Tokyo Medical and Dental University. While working as a doctor, she also completed a master’s degree in arts management at the Department of Aesthetics and Science of Art, Keio University. Her research specializes in marketing research on the purchasing behavior of contemporary art collectors, as well as in practical research on the valuation of artists through various methods in fields such as business, education, medicine and other proximate fields. She has also been serving as a Director of P ROJECT501 in Tokyo, which promotes the new appeal of art from the perspective of art collectors. She produced the residency studio fish market in Kanazawa, co-created by contemporary artist Hiraki Sawa and British architect AB Rogers.

Hiroshi Onishi

Hiroshi Onishi is an associate professor in the Graduate School of Business Administration at Keio University, Japan. He obtained Ph.D. degree of Business Administration from the Ross School of Business at University of Michigan. His area of expertise is statistical data analysis. He leads the Art in Business project at the Japan Marketing Academy, focusing on research of the Japanese art market and its practical applications to business industries.

Notes

1 The definition of the contemporary art collectors varies among existing research and it is difficult to find a well-documented definition. In this study, we followed the definition by Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) and revised their selection condition to accommodate for the Japanese contemporary art collectors. In addition, we conducted a pre-survey for more than 10,000 subjects to verify our selection condition of the contemporary art collectors.

2 Due to space limitations, more information on the art collector qualitative research and interviews is presented in the Online Supplement.

3 ART FAIR TOKYO is the largest art trade show in Japan, which is held in Tokyo for about four days in mid-March every year. The annual survey on the Japanese art market has been conducted since 2016. Their survey reports are available at https://artmarket.report/2021/en.

4 We ensure that the sample size of 386 is sufficient enough, which is surpassed the theoretically required sample size of 280 by the G*Power result for ANOVA of four groups.

5 Although we first conducted a factor analysis, even after trying several selection conditions, we were unable to identify statistically appropriate factors; thus, we adopted a clustering analysis without factor decomposition as a typing method.

6 In our former qualitative research, we named the obtained three subgroups based on the results of their characteristics. Firstly, the ‘intelligent type’ represented their unique characteristics of their artwork purchases mainly motivated by the intellectual motivations which were defined in the same manner as Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011). In addition, among the normative motivations, they prioritized constructing relationships within their community to enhance their intellectual fulfillment through purchasing artworks while seeking harmony with society. Secondly, we named the ‘geek type’, because they predominantly exhibited the hedonic motivations, particularly related to aesthetic pursuit, pleasure, immersion, and captivation. Many subjects of this type belonged to the creative industry, and they purchased artworks solely on the desire to find works that align with their intrinsic and aesthetic values. Thirdly, the ‘balanced type’ was named from a balanced emphasis on their purchase motivations among the economic motivations, the good cause motivations and the harmony motivations. Especially, their strong good cause motivations distinguished them from the other collector types, as Zolfagharian and Cortes (Citation2011) pointed out that some art collectors had motivations both to support artists through their purchases and to acquire artworks with their economic value.

References

- Andreasen, A. R., & Belk, R. W. (1980). Predictors of attendance at the performing arts. Journal of Consumer Research, 7(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1086/208800

- Angello, R. J. (2002). Investment return and risk for art: evidence from auctions of American paintings. Eastern Economic Journal, 28(4), 443–461. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40325391

- Arnould, E. J., & Price, L. L. (1993). River magic: Extraordinary experience and extended service encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 24–25. https://doi.org/10.1086/209331

- Bates, C. S. (1983). An unexpected international market: The art market. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 11(3), 240–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/009207038301100304

- Bourriaud, N., Pleasance, S., Woods, F., & Copeland, M. (2002). Relational aesthetics. Presses du reel.

- Celsi, R. L., Rose, R. L., & Leigh, T. W. (1993). An exploration of high-risk leisure consumption through skydiving. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1086/209330

- Deloitte, A. (2019). Art & finance report 2019 (6th ed.). Deloitte Luxemburg.

- Ekelund, R., Ressler, R., & Watson, K. (2000). The death-effect in art prices: A demand-side exploration. Journal of Cultural Economics, 24(4), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007618221648

- Flores, R., Ginsburgh, V., & Jeanfils, P. (1999). Long- and short-term portfolio choices of paintings. Journal of Cultural Economics, 23, 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007515710962

- Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1982). Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods, and propositions. Journal of Marketing, 46(3), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298204600314

- Hopkinson, G. C., & Pujari, D. (1999). A factor analytic study of the sources of meaning in hedonic consumption. European Journal of Marketing, 33(3/4), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569910253053

- Joy, A., & Sherry, J. F. (2003). Speaking of art as embodied imagination: A multisensory approach to understanding aesthetic experience. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 259–282. https://doi.org/10.1086/376802

- Keen, G., & Norman, G. (1971). Money and art: a study based on the Times-Sotheby Index. G. P. Putnum.

- Kossenjans, J., & Buttle, F. (2016). Why I collect contemporary art: Collector motivations as value articulations. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 15(2), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1362/147539216X14594362873811

- Lazzaro, E., Moureau, N., & Vidal, M. (2015). What drives the VIPs of the art world? Collectors in the light of textual analysis. Universidad de los Andes. https://repositorio.uniandes.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/c1f46883-0cb3-4459-998d-f4ab72025e97/content

- Mandel, B. R. (2009). Art as an investment and conspicuous consumption good. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1653–1663. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.4.1653

- McAndrew, C. (2023). The art market 2023. Art Basel & UBS.

- McClelland, D. C. (1955). Studies in motivation. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- McClelland, D. C. (1961). Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. The achieving society. The Free Press.

- McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R. A., & Lowell, E. L. (1953). The achievement motive. New York 5.

- Rengers, M., & Velthuis, O. (2002). Determinants of prices for contemporary art in Dutch Galleries, 1992–1998. Journal of Cultural Economics, 26(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013385830304

- Richins, M. L. (1994). Valuing things: The public and private meanings of possessions. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(3), 504–521. https://doi.org/10.1086/209414

- Rojas, F., & Lista, P. (2022). A sociological theory of contemporary art collectors. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 52(2), 88–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2021.2014010

- Rush, R. H. (1961). Art as an investment. Prentice Hall.

- Schindler, R. M., & Holbrook, M. B. (2003). Nostalgia for early experience as a determinant of consumer preferences. Psychology & Marketing, 20(4), 275–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10074

- Stein, J. P. (1973). The appreciation of paintings [PhD dissertation]. Department of Economics.

- The European Fine Art Foundation (2017). TEFAF art market report 2017 (R. A. J. Pownall, Ed.). TEFAF.

- Wallack, M. A., Kogan, N., & Bem, D. J. (1962). Group influence on decision making. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 65(8), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044376

- Watae, A. (2014). The current state of art purchases in Japan and challenges for expanding the market size [Master’s thesis]. Keio University.

- Winter, D. G. (1973). The power motive. The Free Press.

- Zolfagharian, M. A., & Cortes, A. (2011). Motives for purchasing artwork, collectibles and antiques. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 9(4), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.19030/jber.v9i4.4207