Abstract

Purpose

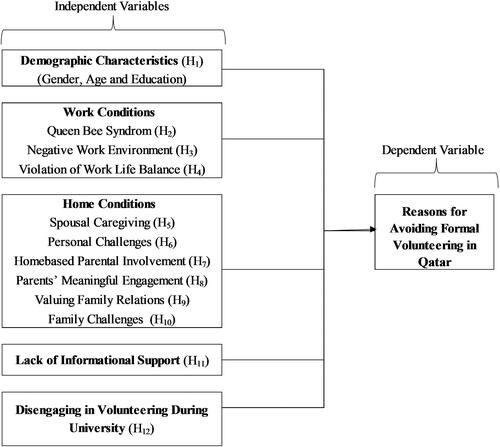

This paper aims to identify key factors influencing the lack of formal volunteering among married Qatari youth.

Methodology

Utilizing data from the Qatar Youth Survey with a sample of 598 married individuals, factor analysis and multiple regression were employed for analysis.

Findings

The principal findings highlight significant associations with non-volunteerism, including a negative work environment, preference for a male boss, parents’ engagement with food and play, home-based parental involvement, and spousal caregiving responsibilities.

Practical Implications

The proposed study is expected to assist policymakers and decision-makers in Qatar draw strategies based on volunteers’ rebuttals when calling for community service and unpaid helpers from local youth.

Originality

This research contributes to existing knowledge as the first study in Qatar exploring the causes of non-volunteerism using multiple observed statements derived from previous research.

1. Introduction

Qatar, a very small country in the GCC, is developing rapidly. As part of this development, Qatar is hosting major mega events such as the FIFA World Cup™ 2022 and Expo 2023, which may require a substantial number of volunteers. Volunteerism plays a pivotal role in shaping the lives of individuals and contributing to Qatar’s broader development. Engaging in volunteer activities not only provides valuable experience and skills but also fosters a sense of community and civic responsibility, promoting social cohesion, personal growth, and national pride (Manadili, Citation2023).

According to the National Council for Voluntary Organizations, ‘[V]olunteering is when someone spends unpaid time doing something to benefit others. Volunteering can be formal and organized by organisations, or informal within communities’ (National Council for Voluntary Organizations, Citation2022, p.1). This research specifically focuses on formal volunteering.

According to Barron and Rihova (Citation2011, p. 202), ‘[V]olunteering as an economic activity has recently acquired a prominent role in government strategies and population surveys’. Pirani et al. (Citation2022, p. 933) believe that ‘the use of volunteers is one of the approaches to capacity building’, but it is important to note that behavioral theories suggest the motivation to volunteer work can be attributed to both personal and social reasons, with various influences driving one’s intent to engage in volunteerism. Internally, individuals are often motivated by self-actualization needs, which are situated at the pinnacle of Maslow’s hierarchy, where engaging in service to others without expecting material gain is linked to self-actualization in the form of social responsibility (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019). Notably, Jo Stuart (Citation2019, p. 2) reported that ‘marriage has been found to increase social contacts and networks, opening up opportunities to be asked to volunteer’. By participating in meaningful and impactful activities, volunteers can develop new skills, gain experiences, and make connections that benefit them (Manadili, Citation2023).

Despite the recognized benefits, there is a noticeable scarcity of studies focusing on volunteering in the GCC in general and Qatar in particular (Diop et al., Citation2022). Research on volunteering is crucial to further promoting a culture of volunteerism in Qatar, especially among youth. The youth represent an essential component of society and are seen as future leaders, constituting a significant proportion of Qatar’s population (Al-Marri, Citation2023). Qatar’s youth can contribute to achieving the national vision as they embody qualities of effectiveness, activity, and accountability (Al-Marri, Citation2023). However, Yotopoulos (Citation2022) identified three reasons for individuals to decline volunteer opportunities: (1) limited free time, (2) a lack of information about volunteer opportunities, and (3) a lack of solicitation for volunteering roles.

From a sociological perspective, several theories shed light on why individuals may opt not to volunteer despite potential societal benefits. According to the role strain theory, the more roles individuals take on, the more burden they experience (Cho et al., Citation2018). This theory posits that the stress and strain from fulfilling responsibilities such as work, caregiving, and family obligations can limit the capacity for additional commitments like volunteering. ‘Parents of very young children tend to volunteer less than people with no children or people with school-age children’ (Einolf & Chambré, Citation2011, p. 300). Similarly, time constraint theory posits that individuals’ availability for volunteering is constrained by their work obligations, suggesting a negative relationship between work responsibilities and volunteer engagement (Qvist, Citation2021). ‘People who work multiple jobs or jobs with in-flexible hours have less time available to volunteer’ (Einolf & Chambré, Citation2011, p. 300). While, social integration theory proposes a more nuanced perspective, suggesting an inverse U-shaped relationship where paid work can simultaneously limit free time while enhancing social connections and integration within society, resulting in more volunteering (Qvist, Citation2021).

That said, a research team from Qatar University conducted a mixed-methods study on youth engagement in social change, as well as related challenges and solutions (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019). The study focused on youth, and it included two age groups: 13–17- and 18–29-year-olds, totaling 277 youth, of which 173 were Qatari (70.9%), 83 were married, and six were divorced (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019, p. 25). Only 19.1% of the sample reported engaging in volunteerism in the six months prior to study participation, and the most common activities that participants identified as volunteering were helping the needy and people with disabilities, followed by environmentally driven initiatives, such as cleaning public spaces, and participating in initiatives led by charities, such as Qatar Charity and Red Crescent (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019). The researchers believe these directions may be influenced and guided by the strong religious beliefs of the participants and the ongoing campaigns conducted by the aforementioned charities (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019, p. 34). When asked how to improve community engagement, participants indicated ‘the need for advertised diverse opportunities’ (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019, p. 35). Regarding diversity among volunteer interests (environmental, sports, tech, crisis and charity, academic, health, national-oriented, and helping the elderly), times (more evening opportunities), and places (outside of Doha city), participants also expressed the need for more female-oriented volunteering opportunities (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019). Moreover, the Qatari Human Development Report (Al Nabit, Citation2012) found that Qatari youth are a force shaping the national development strategy, as well as that empowerment and civic engagement are essential to youth development. Therefore, initiatives must be designed to include youth in all aspects of community development (Al Nabit, Citation2012), one way being through volunteering.

Understanding the barriers to volunteering among married Qatari youth is crucial for policymakers, festival and event organizers. However, there is a notable lack of comprehensive research on this specific subject in Qatar. As such, this paper aims to address and fill this significant gap in research by delving into the unique challenges faced by married Qatari youth concerning volunteering. By shedding light on these barriers and proposing strategies to overcome them, this research endeavor strives to contribute valuable insights that can enhance the effectiveness of volunteer programs and foster a more inclusive and participatory environment in Qatar.

2. Study rationale

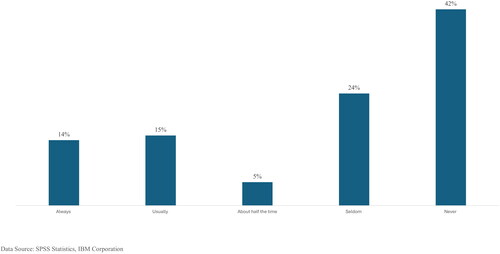

In this study, one of the initial observations that that piqued the researchers’ interest was the responses to the following prompt: ‘please tell me how often you engage in volunteering for an event, charity or association’. illustrates that a significant majority of respondents (66%) reported never or seldom volunteering, despite volunteerism holding great significance in Qatar, particularly considering the country’s desire to host many festivals and events.

Figure 1. PartLabel-upper engagement levels of married Qatari youth in volunteering.

Data Source: SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation.

Qatar, a country with a population of less than three million, was granted the privilege of hosting the global 32-team FIFA World Cup™ competition in 2022. Thereafter, the nation underwent significant transformations in preparation for this monumental event (Hamza, Citation2022). ‘FIFA Tournament Time Demand Model (TTDM) forecasts indicate that upwards of 1.7 million people could visit Qatar during the tournament, with approximately 500,000 visitors in the country on the busiest days’ (ICAO, Citation2019, p. 3). The influx of spectators introduced numerous volunteer opportunities, leading to the mobilization of 20,000 volunteers through the 2022 FIFA World Cup™ Qatar unpaid helper program, which played a pivotal role in the tournament’s operations and left a lasting volunteering legacy in the region (The Peninsula, Citation2022). In addition to the 2022 FIFA World Cup™ Qatar event, the State of Qatar has ambitious plans to host numerous mega events, all of which will demand a substantial number of formal volunteers. ‘Expo 2023 Doha has opened the applications for their volunteer program… volunteering at Expo 2023 Doha presents an unparalleled opportunity to create memories that will last a lifetime’ (Doha Guides, Citation2023). Moreover, Qatar has recently hosted the 2023 AFC Asian Cup from January 12 to February 10, 2024. According to Mair and Weber (Citation2019, p. 209), ‘the rapid growth of the events/festival industry in the past few decades has not always been matched with the level of research devoted to investigating it’.

What is more, according to the 2030 Qatar National Vision 2030, the state of Qatar is aiming to achieve long-term social impact, offering a high standard of living to its citizens and future generations (Government Communication Office, Citation2022). That said, studies conducted on Qatari youth are imperative as they will shape the nation’s future. As suggested by Ishac and Swart (Citation2022, p. 01), ‘[T]he youth were the target population for this study given that they have been identified as the custodians of the next generation and as an essential force in molding national development’. Furthermore, the focus on youth is particularly important for Qatar, because 82.44% of the population is between the ages of 15 and 54 years (Index Mundi, Citation2022). Moreover, mega events such as the FIFA World Cup™ and the Asia Cup require the active participation of youths due to the physical demands inherent in various roles essential for the successful execution of the events such as standing for long hours, assisting with event setup and navigating large crowds. Most importantly, ‘[Time] availability is a key concept in relation to volunteering… and those without partners or children, are the groups most likely to have time to spare’ (Warburton & Crosier, Citation2001, 295). The demands of managing household tasks, childcare, and maintaining a work-life balance contribute to the reduced availability of time for married individuals to volunteer.

Keeping this in mind, it has become important to identify the factors hindering volunteering of married youths in Qatar, as advocated by researchers. Eburn (Citation2015, p. 155) believed that ‘modern emergency management policy is built around the concepts of shared responsibility and the development of resilient communities’, whereas Choi et al. (Citation2007, p. 99) recommended that ‘future studies need to examine in more depth the effect of spousal caregiving on volunteering’. Finally, O’Reilly et al. (Citation2017) suggested that further research is required to understand which types of volunteering are most effective, for whom, and under which circumstances. This paper explicitly answers the following research question: What are the factors significantly associated with the reasons behind avoiding formal volunteering in Qatar?

3. Literature review

3.1. Volunteering in Qatar

The Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy (SC) in Qatar and the 2022 FIFA World Cup™ Qatar worked hard to identify ways of encouraging more volunteers to participate in the 2022 FIFA worldwide event. They announced, ‘FIFA and Qatar are recruiting 20,000 volunteers for the first FIFA World Cup™ in the Middle East and Arab world, which will be held in eight state-of-the-art stadiums from 21 November, 2022, to 18 December, 2022. Volunteers will be at the heart of tournament operations, supporting 45 functional areas and more than 30 different roles’ (News Hub, Citation2022).

The set criteria for inclusion in volunteering included an age of 18 years or older, able to speak English, and being available to commit to a minimum of 10 shifts (Al Mogaiseeb, Citation2022). With the goal of embedding volunteerism into its social legacy, the Supreme Committee constructed a volunteering strategy led by pioneers in youth engagement and volunteering in Qatar, one of whom is Nasser Al Mogaiseeb, the Volunteer Strategy Manager at the SC. The Supreme Committee interviewed 58,000 candidates at the volunteer center in Doha, Qatar, reaching their goal of selecting 20,000 volunteers from 150 nationalities. Local volunteers comprise 17,000 of these volunteers, representing a diverse range of nationalities. The volunteer program focused on training volunteers, both local and international, during an orientation event at Lusail Stadium on September 2, 2022, followed by general and role-specific training modules (Al Mogaiseeb, Citation2022). Over 750 volunteers actively participated in more than 350 training sessions daily, covering a wide range of topics including sustainability, cultural awareness, customer service, role-specific modules, venue-specific training, and volunteer management (Al Mogaiseeb, Citation2022). Special attention was paid to volunteers, allowing them the flexibility to choose between day or night shifts, their preferred stadium or facility for volunteering, and the type of role they wish to undertake (Al Mogaiseeb, June 2023). Gender-based considerations were also made, with female volunteers assigned tasks that respected their privacy, such as roles and placements segregated by gender (Al Mogaiseeb, June 2023). As this World Cup tournament marked the first Arabic tournament held in the MENA region, the volunteering program introduced the Hayahum Programme, an initiative focused on preparing 454 Qatari and Arab volunteers of both genders. In addition, it aimed to equip non-English speaking volunteers with the skills necessary to welcome guests in Arabic and showcase the cultural aspects of Qatar during the tournament (Al Mogaiseeb, Volunteer Strategy Manager, Personal Communication, June 2023).

Various factors could deter individuals from volunteering, and the upcoming literature review will delve into these:

3.1.1. Demographic characteristics

Einolf and Philbrick (Citation2014, p. 13) noted that ‘marriage may increase giving and volunteering in the long term, but it may decrease it in the short term.’ Previous research on marriage and volunteering has focused on the phenomenon that marriage can lead wives to spend more time with their children and can lead husbands to spend less time with their friends. Additionally, Einolf and Philbrick (Citation2014, p. 7) affirm that ‘on average, men, and women differ in their volunteering and giving behavior, and these differences can be traced to gender differences in the variables that predict giving and volunteering’. Staetsky and Mohan (Citation2011, p. 19) assert that ‘age, sex, and educational level proved to be significantly associated most consistently with volunteering’. A study conducted by Diop et al. (Citation2022) reveals that education level has a notably higher association with Qatari citizens’ expressions of interest in volunteering for the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022. Moreover, Diop and colleagues’ (2022) study reveals that younger Qatari respondents were more likely to express interest in volunteering for the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed (H1 serves as the overarching hypothesis, while H1a, H1b, and H1c break down the broad hypothesis into specific demographic variables examined in this research paper):

H1: Demographic characteristics are associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work (Staetsky & Mohan, Citation2011).

H1a: There is a significant association between gender and the reasons for avoiding volunteer work.

H1b: There is a significant association between age and the reasons for avoiding volunteer work.

H1c: There is a significant association between education level the reasons for avoiding volunteer work.

3.1.2. Queen bee syndrome (preferring male bosses)

Historically, ‘Qatar is a male-dominant society in which the Qatari females enjoy fewer freedoms and less social power than the males’ (Esra, Citation2013, p. 5). However, recent years have witnessed changes that favor the status of women, leading to an increase in women’s representation in management. These changes are attributed to modernization and the consistent support of Her Highness Sheikha Mozah bint Nasser, who has served as an inspiration for Qatari women. Despite her significant role in driving civil, educational, economic, and governmental developments in Qatar, remarkably, ‘society continues to judge the female’s actions, using the old values and rules’ (Esra, Citation2013, p. 10).

It is noteworthy that building corporate values and encouraging volunteerism will boost employees’ morale, though a question that may arise is whether employees prefer a male manager or a female manager. A study by Warning and Buchanan (Citation2009, p. 131) argued that ‘the female manager was seen as being more nervous and more aggressive than a male manager. It was also discovered that female preference for male supervisors increased with greater numbers of years in the workforce’.

Furthermore, Moneim Elsaid and Elsaid (Citation2012, p. 81) found that ‘in the Egyptian sample, both males and females held negative views of women managers. However, in the US sample, women held more favorable views of women managers than did their male counterparts’. A different argument presented by Sharkey (Citation2018) warns against ‘queen bee syndrome’, arguing that ‘the concept of queen bee syndrome first came to light in the 1970s. A 1974 study found that women who were successful in male-dominated industries were sometimes capable of hindering the progress of others’. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Preferring male bosses is associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work (Esra, Citation2013; Moneim Elsaid & Elsaid, Citation2012; Sharkey, Citation2018; Warning & Buchanan, Citation2009).

3.1.3. Negative work environment

Work environment and workload can significantly impact the participation in voluntary work among employed individuals. Past research has demonstrated that a lack of supervisory support contributes to avoiding volunteer work, with Cha et al. (Citation2019) arguing that ‘overall, the findings suggest that firms led by CEOs with active civic engagement are more likely to support various philanthropic efforts’ (Cha et al., Citation2019, p. 1054). In addition, a lack of coworker support could be another reason for avoiding volunteer work, with Ocampo et al. (Citation2018, p. 821) and his colleagues arguing that ‘firms have started to look into the behavior exhibited by employees as a means of achieving competitive advantage’.

On the other hand, people could escape the noncooperation of supervisor and coworker to find satisfaction in volunteerism. According to data from the Swiss Household Panel, volunteering can alleviate compatibility issues and enhance work-life balance (Brauchli & Wehner, Citation2015). Additionally, worker volunteers tend to express higher satisfaction with their work-life balance compared to non-volunteers (Ramos et al., Citation2015). Consequently, work environment, workload, and work-life balance collectively exert a substantial influence on an employee’s likelihood of participating in volunteer activities. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Negative work environment is associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work (Cha et al., Citation2019; Brauchli & Wehner, Citation2015).

3.1.4. Violation of work–life balance

Training sessions or meetings scheduled during holidays or outside regular working hours may hinder staff and employee participation in volunteer activities. As noted by Carmichael (Citation2015), the former executive editor at Harvard Business Review, ‘regardless of our reasons for working long hours, overwork does not help us’. In addition, a study conducted by Cook et al. (Citation2022) revealed that several employees mentioned being volunteers outside of work, but the increased workload reduced their capacity to engage in volunteerism. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Work–life imbalance is associated with the reasons behind avoiding voluntary work (Cook et al., Citation2022).

3.1.5. Spousal caregiving

Work commitments are the most commonly cited reason for not volunteering, followed by childcare commitments (Southby et al., Citation2019). Previous research has shown that individuals with caregiving responsibilities are less likely to engage in volunteer work, and Choi et al. (Citation2007, p. 99) concluded that ‘spousal caregiving was not significantly associated with the likelihood of formal or informal volunteering for men; however, female caregivers were found to be less likely than non-caregivers to have engaged in formal or informal volunteering to a certain extent, thus lending partial support to the role overload hypothesis’. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5: Spousal Caregiving is associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work (Choi et al., Citation2007; Southby et al., Citation2019; Stuart, Citation2019).

3.1.6. Personal challenges

Family-related responsibilities and high academic expectations can serve as barriers to parental and student participation in volunteerism. As noted by Al Olimat et al. (Citation2019, p.45), ‘Community service and volunteering can be difficult to balance with substantial familial responsibilities and circumstances, and volunteering timeframes often clash with youth work or study schedules’. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6: Experiencing personal challenges is associated with reasons for avoiding volunteer work (Stuart, Citation2019).

3.1.7. Home-based parental involvement

Engaging in voluntary work poses a significant challenge for parents, given their myriad family responsibilities. As articulated by Al Mogaiseeb, Volunteer Strategy Manager, in a personal communication in June 2023, ‘As parents, we want to maintain a good relationship with our kids and be in their lives, especially when they are younger and require more parental presence’. Consequently, the following hypothesis is put forth:

H7: Home-based parental involvement is associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work. (Stuart, Citation2019).

3.1.8. Parents’ meaningful engagement in food and play

‘When a new baby is born, volunteering dips due to the time and attention needed to look after younger children’ (Stuart, Citation2019, p. 2). It is understandable that when parents have more obligations to care for their younger children, less time will be allocated for formal and informal volunteering for men and women. On the other hand, Einolf reports that: ‘[T]he arrival of children often affect their parents differently…. Having children can cause middle-class couples to intensify their specialization into caretaker and breadwinner roles, so that one partner works longer hours for more pay, while the other works less in the labor market and more at home. Specialization into roles can spread to volunteering’ (Einolf, Citation2018, p. 398). Thus, this hypothesis is proposed:

H8: Parents’ meaningful engagement in food and play is associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work (Stuart, Citation2019).

3.1.9. Valuing family relationships

Valuing family relationships significantly impacts one’s ability to commit to volunteering, especially when parents play a significant role in their children’s lives, including driving to school or taking care of infants. Volunteering demands a considerable commitment of both time and effort, similar to other roles (Al Mogaiseeb, Volunteer Strategy Manager, Personal Communication, 2023). Volunteer parents may even face challenges when trying to maintain a positive image for the volunteering agency, as their familial responsibilities and unexpected emergencies can sometimes conflict with their volunteering commitments. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H9: Valuing family relationships is associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work. (Southby et al., Citation2019).

3.1.10. Family challenges

Non-volunteering individuals are more likely to perceive personal barriers as limiting their ability to engage compared to those who actively seek volunteer opportunities (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019). Despite the frequency of volunteerism, family-related circumstances can pose challenges for those dedicated to volunteering and serving their community. Al Olimat et al. (Citation2019, pp. 45–47) identified four such challenges: placement far from home with limited transportation options, a lack of social and financial support when volunteering at no cost, negative connotations and assumptions surrounding available opportunities, and family disapproval of engagement in volunteerism. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H10: Experiencing family challenges is associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019).

3.1.11. Informational support

Providing information support for the volunteers can help them better understand the event and its management, leading to a better experience and potential repeat volunteering. The success of mega events depends heavily on the participation of volunteers who handle many operations and administrative tasks (Lockstone & Baum, Citation2009). Fee and Gray (Citation2022) highlighted that the performance of volunteers is significantly influenced by emotional and informational support, highlighting the importance of fostering a supportive environment for volunteers to enhance their effectiveness in their roles. Moreover, Dong (Citation2015) pointed out that a lack of sufficient training and support from the organization are sources of risk in volunteering. Al Olimat et al. (Citation2019, p.45) identified organizational challenges related to youth participation in volunteerism, including ‘…limited preparation and training for volunteers, volunteers’ inability to select their own tasks or placements, a lack of recognition and appreciation for volunteers, volunteer burnout due to being assigned a substantial number of administrative or technical tasks, and the role of the volunteer not being clear’. Providing volunteers with information, support, and a comfortable environment is essential to helping them manage their responsibilities and overcome challenges. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H11: A lack of informational support is associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019; Stirling et al., Citation2011).

3.1.12. Volunteering during university

Some studies have indicated that university students are less likely to participate actively in community volunteer work. Moore et al. (Citation2014) found that while 88.2% of students reported having a history of volunteerism, only 22.9% were currently active volunteers. Despite awareness of the benefits of volunteering, young people often face difficulties engaging in volunteer work due to their demanding university obligations. Furthermore, some research has shown that youth may perceive volunteering as an unenjoyable activity. According to Bernstein, two factors contribute to the discontinuation of volunteerism: a lack of time and the burden that can come with long-term commitments, as well as the realization that not all volunteer tasks are enjoyable (Bernstein, Citation2010). As a result, students often struggle to balance their university commitments with their volunteer responsibilities. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H12: Disengaging in volunteerism during university is associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work (Moore et al., Citation2014).

4. Survey design and methodology

4.1. Population and sample selection

The Social and Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI) maintains a comprehensive national telephone database of Qatari households (El-Kassem, Citation2024), updated every two years in collaboration with a telephone provider. From this database, SESRI’s sampling experts used advanced statistical methods to draw a representative sample, reflecting the demographic and socio-economic diversity of the Qatari population. Moreover, interviewers were selected from the SESRI’s existing pool of telephone interviewers who had undergone extensive training in the survey instrument and Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) techniques. Each phone number in the sample was called seven times at various times of the day and on different days of the week to maximize the chance of reaching respondents. Similar to other surveys, the sampling plan for this project could result in varying response rates and selection probabilities among different subgroups. Therefore, a weighted dataset was employed for analysis and reporting. This paper is a part of the larger SESRI Qatar Youth Survey, and it focuses on 598 married youth out of the 1,989 participants surveyed by the SESRI in Qatar. The survey targeted a large sample of Qatari citizens aged 18 to 29 who resided in Qatar during the time of the survey. Verbal consent was obtained from each participant, as the survey was conducted via phone. Participants were informed about the purpose of the survey and were assured that their data would only be presented in aggregate format (El-Kassem, Citation2024); their names would neither be presented nor used in the study. Each participant voluntarily agreed to take part before the study commenced. The study excluded individuals outside the specified age range, non-Qatari citizens, Qatari citizens not residing in Qatar during the survey period, those who did not provide informed consent, and individuals with potential conflicts of interest that could influence their responses. These criteria were implemented to maintain the study’s relevance and uphold ethical standards by focusing on the intended demographic. Among the 598 participants, 114 (19.1%) were under 24 years old, while the remaining 484 (80.9%) were between 24 and 29 years old. The survey included 285 (47.7%) females and 313 (52.3%) males; only 288 (48.2%) hold a university degree or higher education qualification; and most respondents 425 (71.1%) reported working full-time.

4.2. Instrumentation (questionnaire construction)

In preparation for the survey, the project team, based on findings from the literature review and two panel discussions with experts in the field of Qatari youth, developed an initial English-language draft of the survey instrument, which was subsequently translated into Arabic. The questionnaire was developed based on validated tools and scales, omitting any sensitive questions or statements. The survey was administered in both English and Arabic. Prior to the main survey, a pretest involving approximately 30 randomly selected Qatari youth respondents was conducted, based on the results of which the survey instrument was modified. The research team then utilized the final revised questionnaire to update the programming script used for data collection. Subsequently, the instrument underwent multiple rounds of debugging by the research team to address any programming issues.

4.3. Factor analysis and construct validation

The questionnaire designed for this research consisted of 85 scaled items, numbered from 1 to 85. Out of these, 36 scaled items were utilized in factor analysis. The statements in the questionnaire were rated on 4-point Likert scales, with the following parameters: Agreement (including options for strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree); Frequency (including always, often, seldom, and never); Comfort (including very comfortable, somewhat comfortable, somewhat uncomfortable, and not comfortable at all); Concern (ranging from very concerned, somewhat concerned, somewhat unconcerned, to not concerned at all); Importance (including very important, somewhat important, slightly important, and not at all important); and Satisfaction (ranging from very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, to very dissatisfied). In addition, the dependent variable statements were measured using a 4-point Likert barrier scale, including options for not a barrier, somewhat a barrier, a moderate barrier, and an extreme barrier.

Considering the unexpected findings, which indicated that a minority of married Qatari youth respondents volunteer, as previously mentioned in the study’s rationale, the researchers proceeded to conduct exploratory factor analysis to delve deeper into the factors strongly associated with the reasons for avoiding volunteer work. Two statistical tests were conducted to evaluate the appropriateness of the exploratory factor analysis. First, a score of 0.596 was obtained for the Kaisers-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test of sample adequacy, which is much higher than the recommended limit of 0.50 as shown in . Second, the 36 valid items had sufficient inter-correlations to support factor analysis, according to Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (chi-square = 1,646.740, P = 0.00). Further, the rotation method was oblique, and the extraction method was primary axis factor, and finally, 12 factors (dimensions) were extracted using a factor loading larger than 0.531, where the 12-factor exploratory solution accounted for 67.113% of the total variance. The Cronbach alpha were used to measure the internal consistency of the 12 factors. Saidi and Siew (Citation2019, p. 654) cited George and Mallery (Citation2003), who defined Cronbach’s alpha values as follows: ‘Above 0.90 indicates excellent internal consistency, above 0.80 is good, above 0.70 is acceptable, above 0.60 is questionable, above 0.50 is poor, and below 0.50 is unacceptable’.

Table 1. KMO and Bartlett’s test.

The twelve dimensions of the factor analysis were simple to label:

The first dimension was labeled ‘Personal Challenges’ (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.677), accounting for 10.031% of the total variance and defined by the following five items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.618 to 0.760. These items are: (1) family conflict, (2) coping with stress, (3) school or study problems, (4) lack of family support, and (5) financial instability.

The second dimension was labeled ‘Home-Based Parental Involvement’ (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.773), and it accounted for 9.257% of the total variance and was defined by the following four items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.531 to 0.862. These items are: (1) putting child/children to bed, (2) changing child/children nappies or clothes, (3) bathing child/children, and (4) reading for the child/children.

The third dimension was labeled ‘Informational Support,’ (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.838). This factor accounted for 7.657% of the total variance and was defined by four items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.593 to 0.833. The items explored participants’ level of comfort in asking for information from the following: (1) a community agency, (2) the school counselor, (3) the teacher, and (4) the telephone hotline.

The fourth dimension was labeled ‘Volunteerism during University’ (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.721), and it accounted for 6.879% of the total variance. It was defined by four items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.673 to 0.809. The items measure the level of engagement in the following activity: (1) participate in student clubs during my time at university, (2) involvement in internships during my time at university, (3) participate in volunteering during my time at university, and (4) participate in student council during my time at university.

The fifth dimension was labeled ‘Reasons for Avoiding Volunteering in Qatar’ (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.563). This factor accounted for 5.583% of the total variance and was defined by three items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.531 to 0.770, These items are: (1) lack of time due to work and family commitments, (2) lack of information about opportunities for volunteering and participation, and (3) lack of communication channels between Qatari youth and the authorities.

The sixth dimension was labeled ‘Family Challenges’ (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.362), and it was deleted from the multiple regression analysis for unreliability. This factor accounted for 5.197% of the total variance and was defined by three items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.681 to 0.748. These items are: (1) concerned about financial stability, (2) concerned about job security, and (3) concerned about physical and mental health.

The seventh dimension was labeled ‘The Queen Bee Syndrome (preference for a male boss)’ (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.611). This factor accounted for 4.824% of the total variance and was defined by three items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.733 to 0.783. These items are: (1) in general, I prefer my boss at work to be a man rather than a woman, (2) when it comes to politics, I would rather vote for men than women, and (3) men are naturally better at leadership than women.

The eighth dimension was labeled ‘Violation of Work–Life Balance’ (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.515). This factor accounted for 3.999 of the total variance, and it was defined by two items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.756 to 0.794. These items are: (1) meetings outside of official working hours and (2) trainings outside of official working hours.

The ninth dimension was labeled ‘Caregiving Responsibilities’. This factor accounted for 3.707 of the total variance, and it is defined by one item with a factor loading of 0.739. The item was as lack of dependent care services (childcare or elder care). Notably, it is not possible to calculate Cronbach’s alpha for this factor, as it is a measure of internal consistency, which entails a minimum of two statements for it to be calculated).

The tenth dimension was labeled ‘Parents’ Meaningful Engagement in Food and Play’ (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.580). This factor accounted for 3.471 of the total variance and was defined by two items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.699 to 0.741. These items are (1) eating with your child/children and (2) playing with your child/children

The eleventh dimension was labeled ‘Negative Work Environment’ (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.617). This factor accounted for 3.438 of the total variance, and it was defined by four items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.569 to 0.820. These four items were as follows: (1) heavy workload, (2) long working hours, (3) lack of coworker support and (4) lack of supervisor support.

The twelfth dimension was labeled ‘Family Relations’. This factor accounted for 3.073 of the total variance, and it was defined by one item which is ‘Value family relationships’ with a factor loading of 0.877.

5. Findings of the study

Multiple regression result shows that age, gender, income, and education level were found to be insignificantly associated with the reasons that married youth in Qatar refrain from engaging in voluntary work (see and ). Moreover, valuing family relations, personal challenges, lack of informational support, volunteering during university and violation of work life balance were also found to be insignificantly associated with the reasons that married youth in Qatar abstain from participating in voluntary work. Associations with other interesting factors, such as a negative work environment, preference for a male boss, home-based parental involvement, parents’ meaningful engagement with food and play, and caregiving responsibilities, were found to be significantly associated with the reasons married youth in Qatar do not volunteer (R2=0.294, F = 4.124, p-value = 0.000).

Table 2. ANOVA.

Table 3. Regression coefficients.

6. Discussion

The study investigates the reasons behind the lack of volunteering among married Qatari youth. The results showed no significant associations between volunteering and the factors: demographic characteristics (H1), valuing family relations (H9), personal challenges (H6), informational support (H11), volunteering during university (H12), and violation of work-life balance among married youth in Qatar (H4). The results contrary to what is considered true in prior research (Al Olimat et al., Citation2019; Einolf & Philbrick, Citation2014; Staetsky & Mohan, Citation2011).

The findings of the study support five hypotheses: H2 (preference for a male boss), H3 (negative work environment), and H5 (spousal caregiving responsibilities), H7 (home-based parental involvement) and H8 (parents’ meaningful engagement in food and play). The findings reveal that factors hindering the volunteerism among Qatari married youth are classified into the following categories: (1) home-based variables (include spousal caregiving responsibilities, home-based parental involvement, and parents’ meaningful engagement with food and play) and (2) work-based variables (include preferring a male boss and negative work environment.

The findings of this study were found consistent with previous research in which a strong relationship (p = 0.001) existed between ‘caregiving responsibilities’ and ‘reasons for avoiding volunteering’. As mentioned by Claxton-Oldfield and Claxton-Oldfield (Citation2012, p. 528), ‘When asked, what would make you want to stop volunteering? The most common response—mentioned by volunteers was a family crisis or commitment (e.g. trying to care for your own family and do things with your own family)’. As Al Mogaiseeb, a Qatari Volunteer Pioneer, said in a personal communication (2023), ‘[T]he less volunteer commitment there is in terms of time and placement (volunteering virtually and project-based volunteering), the easier it is to balance family and volunteering expectations’.

Further, an intense relationship was found to exist between a ‘negative working environment’ (p = 0.001) and ‘reasons for avoiding volunteering in Qatar’. This relationship was found negative and consistent with previous research (Brauchli & Wehner, Citation2015; Ramos et al., Citation2015) signifying that people escape the noncooperation of supervisor and coworker to find satisfaction in volunteerism. The increase in volunteering might be the consequence of a toxic work environment, such that volunteering improves one’s happiness and well-being. Through volunteering, people develop social connections that might be useful for networking or finding a job (Meier & Stutzer, Citation2008).

Notably, a weaker relationship (p = 0.02) was observed between ‘home-based parental involvement’ and ‘reasons for avoiding volunteering in Qatar’, consistent with previous research findings (Southby et al., Citation2019). Similarly, another weaker relationship (p = 0.035) was identified between ‘preferring a male boss, i.e. queen bee syndrome’ and ‘reasons for avoiding volunteering in Qatar,’ aligning with previous studies (Esra, Citation2013; Moneim Elsaid & Elsaid, Citation2012; Sharkey, Citation2018; Warning & Buchanan, Citation2009).

Lastly, a negative relationship (p = 0.031) was found to exist between ‘parents’ meaningful engagement with food and play’ and ‘reasons for avoiding volunteering in Qatar’. The results reveal that parents who actively engage in meaningful activities with their children are more inclined to value community involvement and model this behavior for their children. As shown by previous research findings (Einolf, Citation2018), this active engagement fosters a sense of belonging and responsibility that extends beyond the family, making them more likely to find time and motivation for volunteering. Consequently, this dynamic aligns with the concept that having children can lead to role specialization, where one partner might take on more community-focused activities, including volunteering, as an extension of their caretaking role. This modeling of community engagement helps instill similar values in their children, reinforcing the importance of volunteering and community involvement.

7. Recommendations

In Qatar, it is crucial for officials to emphasize to the public the benefits of volunteerism and engagement in community service. This may involve sharing stories that showcase the positive impact of voluntary work on individual’s lives, while also highlighting the specific ways citizens can get involved. Furthermore, building a sense of community and inspiring citizens to participate can be achieved by honoring and commemorating the contributions of individuals engaged in voluntary work. Event organizers should also consider providing flexible volunteer options to married Qatari youth to increase their engagement. These options could include part-time volunteer opportunities, and remote volunteer tasks that can be carried out virtually, such as social media management. Moreover, event organizers should include family-friendly activities that welcome parents and children. ‘When parents volunteer they are acting as role models for their children (Caputo, Citation2009)’ (Wilson, Citation2012, p.188). Such engagement fosters a supportive community environment and cultivates the next generation of empowered youth. Additionally, involving married Qatari youth in voluntary work can provide Qatar as a whole, particularly its valuable pool of skills, perspectives, and experiences to address local challenges and enhance community well-being. Policymakers can take several actions to encourage businesses in Qatar to offer volunteer incentives, including promoting collaboration between businesses and local community organizations to create meaningful and engaging volunteer opportunities for employees. Addressing such issues as the ‘queen bee syndrome’ through training and education can foster a more inclusive work environment. Furthermore, policymakers should educate companies on the benefits of encouraging their employees to engage in volunteerism, as they can lead to an improved workplace culture. Lastly, policymakers can provide incentives to companies that implement recognition programs or incentives for employees engaged in formal voluntary work.

8. Practical implications

The practical insights of this study for Qatar are significant, and they can inform various stakeholders, including policymakers, community organizations, and businesses. It’s noteworthy that there are limited articles published on volunteerism in Qatar. This underscores the importance of this research in filling this knowledge gap and providing valuable insights for the nation. The practical implications are as follows:

Policymakers may leverage the findings of this study to design and implement awareness campaigns that emphasize the benefits of voluntary work. These campaigns can showcase real-life success stories and provide specific ways for citizens to get involved.

Community organizations may draw upon this research findings to design volunteer opportunities that are attractive and accommodating for diverse individuals, specifically married youth. This might involve family-friendly activities, flexible scheduling, and remote volunteering options.

Businesses have the opportunity to harness the outcomes of this research to promote corporate social responsibility through a fostering a culture of voluntarism among their employees.

In summary, this research serves as a catalyst for positive change in advancing the welfare of the Qatari society as a whole.

9. Limitations

Volunteering holds great importance in Qatar, particularly in the context of the country’s ambition to host numerous festivals and events. This research paper explores the significant factors related to the reasons for avoiding voluntary work. Understanding these factors is crucial, given Qatar’s history of hosting numerous events and festivals. Nevertheless, it is essential to acknowledge the study’s limitations. Firstly, due to the limited available funds, the study was conducted over the phone. It is advisable to consider conducting face-to-face interviews, as the phone survey was lengthy and posted challenges in assessing social desirability. Secondly, this research is part of a more extensive research relating to youth transitions, which lead to an age restriction between 18 and 29 years old. This age range aligns with the physical demands of events like the World Cup and the Asia Cup, where young volunteers are typically needed. However, for future studies expanding the age group is highly recommended, especially considering that Qatar may host events that do not specifically require a younger generation.

Authors’ contributions

Four authors were engaged in the project from its inception to its completion. Rima Charbaji El-Kassem, as the first author, assumed primary responsibility for drafting the manuscript, ensuring its clarity, coherence, and adherence to academic standards. Additionally, she played a pivotal role in analyzing and interpreting the results. Noora Lari, the second author and the project’s Principal Investigator (LPI), contributed significantly during the drafting phase, supervising the work and providing substantial input to enhance the manuscript’s clarity and coherence. Alya Al Maadeed and Amal Ali, the third and fourth authors respectively, also played integral roles, contributing notably to the review of literature and the discussion section of the manuscript.

Consent procedure

During the phone survey, interviewers follow a meticulous process to secure consent from respondents ensuring transparency, respect, and confidentiality. At the beginning of the call, interviewers introduce themselves, explain the survey’s purpose, and assure confidentiality. After that, interviewers provide a clear overview of the survey’s topics and duration, inviting any questions or concerns. Interviewers then ask for verbal consent to proceed, respecting respondents’ autonomy and right to decline.

Ethical approval

The Qatari Youth Project received IRB approval (QU-IRB 1700-EA/22) from Qatar University Review Board.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. The researchers would like to thank the research team from the project’s partners and stakeholders (Nama, Ministry of Administrative Development, Labour and Social Affairs, Qatar Finance and Business Academy, Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, and Ministry of Youth and Sports) for generously offering their time and those who took part in the panel discussion prior to the questionnaire design. The authors would also like to thank all the respondents who participated in the Qatari Youth Survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are accessible through the Social and Economic Survey Research Institute. However, we are unable to make the data available due to ethical considerations.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rima Charbaji El-Kassem

Rima Charbaji El-Kassem is a research project manager at the Social and Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI) of Qatar University. She has published numerous articles in Scopus-indexed journals. Her latest article Path analytic investigation of the intention to adopt open government data in Qatar (TAM revisited) is published Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy/ Emerald Library. She is involved in different projects related to education, technology, gender, blue-collar worker welfare, the environment, family, and work–life balance. Prior to working for SESRI, she worked for two credit rating agencies in London: Standard and Poor’s and Fitch Ratings. She has also worked as a research analyst for the investment management department at the European Arab Bank in London. Rima Charbaji El-Kassem was contacted at [email protected]

Noora Ahmed Lari

Dr. Noora Ahmed Lari is Manager of the Policy Department and Research Assistant Professor at the Social and Economic Survey Research Institute at Qatar University. She earned her PhD in Sociology and Social Policy in 2016 from the University of Durham in England. Dr. Lari is vice-chair of Qatar University’s Institutional Review Board (QU-IRB) and currently serves as Qatar’s National Representative to the World Association for Public Opinion Research (WAPOR). Her areas of interest include survey research projects related to the sociocultural development in the State of Qatar and the formulation of evidence-based social policies from survey data.

Alyaa Al Maadeed

Alyaa Al Maadeed holds a position as a Lecturer at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies. She possesses a wealth of expertise and a keen interest in volunteering and event management.

Amal Awadalla Mohamed Ali

Amal Awadalla Mohamed Ali is a Senior Research Assistant at Social and Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI), Qatar University.

References

- Al Mogaiseeb, N. (2022). Volunteer programme key information. In Supreme Committee for delivery and legacy. State of Qatar.

- Al Nabit. (2012). Third Human Development Report: Enhancing Qatari youth capabilities integration of youth into the development process. In General secretariat for development planning. State of Qatar.

- Al Olimat, H., Al Jamal, A., Jumaa, W., Al Kaabi, I., Hamad, S., Badeer, K., & AlEssa, M. (2019). Ways to develop youth work and its innovative role in pioneering social work: Reality, issues and solutions. In Nama youth for development center. State of Qatar.

- Al-Marri, S. H. (2023). How to sustain motivation among the youth in Qatar beyond hosting the FIFA World Cup 2022? QScience Connect, 2023(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5339/connect.2023.spt.1

- Barron, P., & Rihova, I. (2011). Motivation to volunteer: A case study of the Edinburgh International Magic Festival. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 2(3), 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1108/17582951111170281

- Bernstein, J. (2010). Well, he just lost man points in my book:” The absence of volunteerism among first-year college men. Honors College, 574. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/574

- Brauchli, R., & Wehner, T. (2015). Verbessert Freiwilligenarbeit die "Work-Life-Balance"? In Psychologie der Freiwilligenarbeit: Motivation, Gestaltung und Organisation (pp. 169–180). Springer.

- Caputo, R. (2009). Religious capital and intergenerational transmission of volunteering as correlates of civic engagement. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(6), 983–1002. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764008323990

- Carmichael, S. G. (2015). The research is clear: Long hours backfire for people and for companies. Harvard Business Review. August 19. https://hbr.org/2015/08/the-research-is-clear-long-hours-backfire-for-people-and-for-companies

- Cha, W., Abebe, M., & Dadanlar, H. (2019). The effect of CEO civic engagement on corporate social and environmental performance. Social Responsibility Journal, 15(8), 1054–1070. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-05-2018-0122

- Cho, J., Kim, B., Park, S., & Jang, J. (2018). Postretirement work and volunteering by poverty groups informed by role theory. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 61(3), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2017.1416719

- Choi, N. G., Burr, J. A., Mutchler, J. E., & Caro, F. G. (2007). Formal and informal volunteer activity and spousal caregiving among older adults. Research on Aging, 29(2), 99–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027506296759

- Claxton-Oldfield, S., & Claxton-Oldfield, J. (2012). Should I stay or should I go: A study of hospice palliative care volunteer satisfaction and retention. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 29(7), 525–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909111432622

- Cook, J., Burchell, J., Thiery, H., & Roy, T. (2022). “I’m not doing it for the company”: Examining employee volunteering through employees’ eyes. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 52(4), 1006–1028. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640221114309

- Diop, A., Jatić, Š., Holmes, J. L., Le Trung, K., El Maghraby, E., & Al Naimi, M. (2022). Interest in volunteering for the FIFA 2022 World Cup in Qatar: A nationally representative study of motivations. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2022.2090913

- Doha Guides. (2023). How to volunteer at Expo 2023 Doha: Benefits & eligibility. September 3. https://www.dohaguides.com/volunteer-at-expo-2023-doha/

- Dong, H. K. (2015). The effects of individual risk propensity on volunteering. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 26(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21139

- Eburn, M. (2015). Bushfires and Australian emergency management law and policy: Adapting to climate change and the new fire and emergency management environment. In Special issue Cassandra’s curse: The law and foreseeable future disasters (Studies in Law, Politics, and Society) (Vol. 68, pp. 155–188). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1059-433720150000068007

- Einolf, C. (2018). Parents’ charitable giving and volunteering: Are they influenced by their children’s ages and life transitions? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47(2), 395–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764017737870

- Einolf, C., & Chambré, S. M. (2011). Who volunteers? Constructing a hybrid theory. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 16(4), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.429

- Einolf, C., & Philbrick, D. (2014). Generous or greedy marriage? A longitudinal study of volunteering and charitable giving. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(3), e104–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12115

- El-Kassem, R. C. (2024). A path causal model of the effect of TQM practices on teachers’ job satisfaction in schools in Qatar. The TQM Journal, 36(4), 1145–1161. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-01-2023-0012

- Esra, K. (2013). Beyond the stated function: Showcasing, through everyday objects, social obstacles imposed on Qatari female youth [Master’s thesis]. Virginia Commonwealth University. https://doi.org/10.25772/55EC-RN72

- Fee, A., & Gray, S. J. (2022). Perceived organizational support and performance: The case of expatriate development volunteers in complex multi-stakeholder employment relationships. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(5), 965–1004. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1745864

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon. [Database].

- Government Communication Office. (2022). Qatar national vision 2030. Retrieved April 16, 2022, from https://www.gco.gov.qa/en/about-qatar/national-vision2030/

- Hamza, M. (2022). Is Qatar ready to host the World Cup 2022? News | Qatar World Cup 2022. Al Jazeera. November 11. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/11/16/is-qatar-is-ready-to-host-the-world-cup#:∼:text=Doha%2C%20Qatar%20%E2%80%93%20Fans%20and%20football,Gulf%20country%20during%20the%20tournament

- ICAO. (2019). 2022 FIFA World Cup Qatar™ (PDF). International Civil Aviation Organization. https://www.icao.int/MID/Documents/2019/FWC2022%20TF2/FWC2022%20TF2%20PPT2.pdf

- Index Mundi. (2022). Qatar demographics profile. Retrieved April 16, https://www.indexmundi.com/qatar/demographics_profile.html

- Ishac, W., & Swart, K. (2022). Social impact projections for Qatar youth residents from 2022: The case of the IAAF 2019. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 922997. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.922997

- Lockstone, L., & Baum, T. (2009). The public face of event volunteering at the 2006 Commonwealth Games: The media perspective. Managing Leisure, 14(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606710802551254

- Mair, J., & Weber, K. (2019). Event and festival research: A review and research directions. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 10(3), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-10-2019-080

- Manadili, T. (2023). Volunteers’ motivations to participate in the FIFA World Cup 2022: A cross-national study [Doctoral dissertation]. Hamad Bin Khalifa University.

- Meier, S., & Stutzer, A. (2008). Is volunteering rewarding in itself? Economica, 75(297), 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00597.x

- Moneim Elsaid, A., & Elsaid, E. (2012). Sex stereotyping managerial positions: A cross‐cultural comparison between Egypt and the USA. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 27(2), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542411211214149

- Moore, E., Warta, S., & Erichsen, K. (2014). College students’ volunteering: Factors related to current volunteering, volunteer settings, and motives for volunteering. College Student Journal, 48(3), 386–396.

- National Council for Voluntary Organizations. (2022). Volunteering. https://www.ncvo.org.uk/help-and-guidance/involving-volunteers/understanding-volunteering/what-is-volunteering/

- News Hub. (2022). Final call to become a FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ volunteer. https://www.qatar2022.qa/en/news/final-call-to-become-a-fifa-world-cup-qatar-2022-volunteer

- O’Reilly, D., Rosato, M., Ferry, F., Moriarty, J., & Leavy, G. (2017). Caregiving, volunteering or both? Comparing effects on health and mortality using census-based records from almost 250,000 people aged 65 and over. Age and Ageing, 46(5), 821–826. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx017

- Ocampo, L., Acedillo, V., Bacunador, A. M., Balo, C. C., Lagdameo, Y. J., & Tupa, N. S. (2018). A historical review of the development of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and its implications for the twenty-first century. Personnel Review, 47(4), 821–862. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2017-0136

- Pirani, D., Safi-Keykaleh, M., Farahi-Ashtiani, I., Safarpour, H., & Jahangiri, K. (2022). The challenges of health volunteers management in COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 36(7), 933–949. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-05-2022-0146

- Qvist, H. P. Y. (2021). Hours of paid work and volunteering: Evidence from Danish panel data. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 50(5), 983–1008. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764021991668

- Ramos, R., Brauchli, R., Bauer, G., Wehner, T., & Hämmig, O. (2015). Busy yet socially engaged. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 57(2), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000327

- Saidi, S. S., & Siew, N. M. (2019). Investigating the validity and reliability of survey attitude towards statistics instrument among rural secondary school students. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 5(4), 651–661. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijem.5.4.651

- Sharkey, S. (2018). May 24). Evolution or sexism: Why are so many female bosses ‘queen bees’? Metro. Retrieved November 26, 2022, from https://metro.co.uk/2018/05/24/evolution-or-sexism-why-are-so-many-female-bosses-queen-bees-7548191.

- Southby, K., South, J., & Bagnall, A. M. (2019). A rapid review of barriers to volunteering for potentially disadvantaged groups and implications for health inequalities. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(5), 907–920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00119-2

- Staetsky, L., & Mohan, P. (2011). Individual voluntary participation in the United Kingdom: An overview of survey information. Third Sector Research Centre Working Paper 6. London. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/189315/1/WP06_Individual_voluntary_participation_in_the_UK_-_Staetsky_May_2011.pdf.

- Stirling, C., Kilpatrick, S., & Orpin, P. (2011). A psychological contract perspective to the link between non-profit organizations’ management practices and volunteer sustainability. Human Resource Development International, 14(3), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2011.585066

- Stuart, J. (2019). The links between family and volunteering: A review of the evidence. The Pears Family Charitable Foundation. September. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://pearsfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/the_links_between_family_volunteering_summary_final_with_banner.pdf.

- The Peninsula. (2022). Over 500,000 sign up to volunteer ahead of Qatar 2022. The Peninsula. July 29. 6https://m.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/29/07/2022/over-500000-sign-up-to-volunteer-ahead-of-qatar-2022.

- Warburton, J., & Crosier, T. (2001). Are we too busy to volunteer? The relationship between time and volunteering using the 1997 ABS time use data. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 36(4), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2001.tb01104.x

- Warning, R., & Buchanan, F. R. (2009). An exploration of unspoken bias: Women who work for women. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 24(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542410910938817

- Wilson, J. (2012). Volunteerism research: A review essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(2), 176–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011434558

- Yotopoulos, A. (2022). Three reasons why people don’t volunteer and what can be done about it. The Stanford Center on Longevity. Retrieved November 26, https://longevity.stanford.edu/three-reasons-why-people-dont-volunteer-and-what-can-be-done-about-it.