?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Self-control emerges in early childhood and is shown to be strongly related to poor adulthood outcomes. The development of self-control was long believed to be homogeneous among individuals and stable in rank. The purpose of the current study was to (1) examine if multiple growth trajectories of self-control existed in early childhood by using growth mixture modeling approach, (2) investigate if growth trajectories of self-control were the function of child, family, and school characteristics. Using data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort of 2011 (ECLS-K:2011), we found (1) three distinct growth trajectories of self-control existed in the ECLS-K sample, namely, the high, medium, and low level of self-control; (2) self-control levels in all groups were relatively stable during early childhood; (3) teacher expectation and teacher-student relationship significantly predicted growth trajectories of self-control above and beyond certain child and family characteristics.

IMPACT AND IMPLICATION STATEMENT

The current findings add to the understanding of self-control development during early childhood. The multiple and relatively stable growth trajectories of self-control supported the heterogeneity of self-control development as well as the relative stability theory during eraly childhood. The child, family, and school factors that predicted membership of each trajectory allows for the early identification of children who are at-risk for low self-control. Environmental factors that could be possible areas of intervention are also identified.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Many researches have demonstrated that self-control in early childhood can predict later outcomes, such as academic achievement, physical and mental health, income, etc. This study aimed to describe the development growth of self-control in early childhood as well as to investigate factors that could influence it. We found three distinct growth trajectories of self-control in early childhood (from kindergarten to second grade), namely the high, medium, and low level of self-control. More importantly, the current study found that the teacher-student relationship and teacher expectation were significantly related to the growth of self-control above and beyond some background variables (e.g., gender, race, SES, etc). Therefore, we recommend that educators maintain high levels of expectation of their students and cultivate good relationships with them to facilitate the growth of self-control in early childhood.

1. Introduction

Self-control refers to an individual’s ability to control his/her current desires to achieve more valued long-term goals. It entails regulating one’s actions, thoughts, and emotions to work toward longer-term rewards at the expense of immediate gratification (Duckworth & Steinberg, Citation2015). Self-controlled behaviors have been found to emerge in early childhood and continue to develop till adulthood. Low levels of self-control at early stages were found to be associated with both concurrent problems, such as poor concentration (Howse, Lange, Farran, & Boyles, Citation2003), lower academic achievement (Cooper, Moore, Powers, Cleveland, & Greenberg, Citation2014; Ng-Knight et al., Citation2016; Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, Citation2004), lower subjective well-being (Ronen, Hamama, Rosenbaum, & Mishely-Yarlap, Citation2016), and more externalizing problems (Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, Citation2013), as well as poor adulthood outcomes, such as poor physical and mental health, low income, and high rates of crime (Daly, Delaney, Egan, & Baumeister, Citation2015; Daly, Egan, Quigley, Delaney, & Baumeister, Citation2016; Moffitt et al., Citation2011). In the developmental psychology literature, self-control and self-regulation are used roughly interchangeable (Vohs & Baumeister, Citation2016, p. 3), in the current study, we adopted “self-control” to keep the consistency with the measures we used. Also, following the convention, we defined the early childhood from birth to 8-year old (The Center for High Impact Philanthropy, Citation2015).

2. Developmental trajectory of self-control

In the field of development of self-control, it is a long-standing belief that children’s self-control develops dynamically till the ages of 8–10, from which point on it remains relatively stable across the lifespan (i.e., higher levels remain higher, lower levels remain lower) (Gottfredson & Hirschi, Citation1990). Only few studies examined the development of self-control during early childhood. Using data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class (ECLS-K), Beaver and Wright (Citation2007) tested the stability of self-control from kindergarten through first grade in over 17,000 children via a structural equation modeling approach. The findings suggested that self-control was a stable trait with high stability coefficients (0.84 to 0.96) during this age range. Different from Beaver et al.’s (Citation2007) study which assumed a homogeneous developmental trajectory of self-control, Coyne, Vaske, Boisvert, and Wright (Citation2015), Coyne & Wright (Citation2014) hypothesized that heterogeneous developmental trends might exist. They employed a Latent Growth Class Modeling approach to analyze the growth trajectories of twins (N = 360) and paired singletons (N = 423) from kindergarten to fifth-grade also using the ECLS-K data. Results showed two growth trajectories existed: consistently high and consistently low, which also supported the stability hypothesis. In the follow-up study, Coyne et al. (Citation2015) found self-control was relatively stable in both male and female populations of the same ECLS-K sample.

However, other studies have found self-control exhibited rank changes in certain samples. Hay and Forrest (Citation2006) analyzed five waves of a national sample of US children aged 7–15. Using a semiparametric group-based method, they found that in a small subsample (less than 10%) self-control lacked relative stability. Diamond, Morris, and Piquero (Citation2015) applied the Growth Mixture Modeling approach and analyzed self-control in a community-based sample of children aged 5 to 26. They found four growth trajectories of self-control, all of which changed rank orders across the 20 years period. Results of these studies failed to support the relative stability hypothesis and indicated the development of self-control was heterogenous and varied by the group.

3. Risk factors associated with low self-control

Several risk factors were found to be associated with low self-control in early childhood, including genetic factors (Beaver, Wright, DeLisi, & Vaughn, Citation2008; Boutwell & Beaver, Citation2010), family factors, school factors, and social contexts (Buker, Citation2011). Using a sample of 452 dizygotic and 289 monozygotic twin pairs who were middle and high school students at the time, Beaver et al. (Citation2008) found genetic factors accounted for 52%–64% of the variance in self-control. Gender differences were also commonly found in self-control literature, such that females usually had a higher level of self-control than males (Chapple, Hope, & Whiteford, Citation2005; Gibbs, Giever, & Martin, Citation1998; Gibson, Sullivan, Jones, & Piquero, Citation2010). Moreover, some studies found race could predict self-control even when controlling parenting and other social factors (Chapple et al., Citation2005; Lynskey, Winfree, Esbensen, & Clason, Citation2000; Perrone, Sullivan, Pratt, & Margaryan, Citation2004; Pratt, Turner, & Piquero, Citation2004).

Family factors were widely related to the level of self-control with parenting practices the most researched factors. Past research contended that parental socialization, management, and parent-child relationships play a major role in determining the level of children’s self-control (Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, Citation2010; Gottfredson & Hirschi, Citation1990; Li-Grining, Citation2007). Moreover, family income, maternal education, and mental health could also influence the development of self-control of young children (Sektnan, McClelland, Acock, & Morrison, Citation2010). For example, single parenthood, low SES, and high family stress were related to lower self-control. (Bennett, Elliott, & Peters, Citation2005; Brannigan, Gemmell, Pevalin, & Wade Terrance, Citation2002; Chapple et al., Citation2005; Sarsour et al., Citation2011; Vaughn, DeLisi, Beaver, & Wright, Citation2009). Influence of family factors might also increase over time. For example, Gajos and Beaver (Citation2016) found the impact of home adversity became a stronger predictor of self-control levels after ages 8 or 9.

School factors, such as teacher-student closeness and teacher support have been found to be related to higher levels of self-control for students (Turner, Piquero, & Pratt, Citation2005). Social contexts, including neighborhood environment, peer group affiliation, were also related to children’s self-control development (Bennett et al., Citation2005).

4. Motivation for the current study

Gottfredson and Hirschi (Citation1990) argued levels of self-control become relatively stable after age 10. The majority of previous research on the development of self-control focused on older children or adolescents (older than 10) and partially supported Gottfredson et al.’s theory in that self-control exhibited rank stability in for the majority population during early childhood, though their rank orders did change in a small number of samples and over a wider age range. Also implied in Gottfredson et al.’s theory (Gottfredson & Hirschi, Citation1990) is that children’s self-control develops dynamically before age 8, and therefore, may be more susceptible to intervention. However, few studies examined the development of self-control during early childhood, and the existing few all analyzed the same dataset (Beaver & Wright, Citation2007; Coyne et al., Citation2015; Coyne & Wright, Citation2014). Given that mixture growth modeling is a data-driven approach (Abenavoli, Greenberg, & Bierman, Citation2017), further studies using other samples are needed to validate previous results.

Moreover, if different growth trajectories of self-control exist during early childhood, it is important for educators and researchers to understand what factors may predict membership of each trajectory during early childhood. Although past studies have identified risk factors related to low self-control, few of these studies examined these risk factors in the context of multiple growth trajectories of self-control. Therefore, the characteristics of children who exhibit different patterns of self-control growth early on are still unclear.

The purpose of the current study was to (1) examine if multiple growth trajectories of self-control existed in early childhood using a newly released national representative sample, and (2) investigate which child, family, and school characteristics could predict growth trajectories of self-control.

Research questions:

Do heterogeneous growth trajectories of self-control exist during early childhood among current US children?

What is the developmental trajectory of self-control among current US children?

What child, family, and school characteristics could predict growth trajectories of self-control for the current US children?

5. Method

5.1. Dataset

This study used data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort of 2011 (ECLS-K:2011). The ECLS-K:2011 used a multistage probability sample design to select a nationally representative sample of US children who attended kindergarten during the 2010–2011 school year. A total of six waves of data have been released to the public (K-fall, K-spring, Grade 1—fall, Grade 1-spring, Grade 2-fall, and Grade 2-spring). The ECLS: K:2011 provides nationwide representative data on children’s development, learning, and performance at school. Background variables including family, school, and community characteristics were also included, which could provide opportunity to investigate the relationship between these variables and the development of self-control. The ECLS database was also commonly used in the current literature of self-control development (e.g., Coyne et al., Citation2015; Coyne & Wright, Citation2014; Vaughn et al., Citation2009). Therefore, using the ECLS: K:2011 dataset allows more readily comparison between the findings in the current and previous studies.

5.2. Samples

All six waves of data from the ECLS-K:2011 public-use database was used. Children were excluded from the sample if scale scores of any sub-constructs were missing at all measurement occasions. One of the twins were also excluded to remove the dependency in the family. Of 17,322 children (8,845 males, 8,443 females, and 35 missing) were included in the current study. The age of entering kindergarten ranged from 44.81 months to 93.90 months (mean = 67.47 months). The racial/ethnic distribution of the sample is: Whites (47.3%), African-Americans (13.2%), Asians (8.0%), Hispanics (25.2%), and others (6.12%). Descriptive statistics of other key demographic variables are shown in Table .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (N = 17,322)

5.3. Measures

5.3.1. Self-control

The ECLS used a modified version of the Social Skills Rating System (SRSS; Gresham & Elliot, Citation1990). The SRSS is a standardized multi-rater, multi-scale measure where parents and teachers rate children’s behaviors on a 4-point scale (1 = never; 4 = very often). Using different cohorts of the ECLS dataset, Coyne and Wright (Citation2014) conducted a factor analysis on the modified SSRS and found four scales on it reflect one underlying construct of self-control. The four scales are: self-control (ability to regulate one’s behaviors in social situations, 4 items), interpersonal skill (ability to interact appropriately with others, 5 items), externalizing problem behavior (acting out or rule-breaking behaviors, 5 items), and approaches to learning (positive learning behaviors such as being organized and following classroom rules, 7 items). The externalizing problem behavior scale was reverse scored. Scores on these four scales were found to be highly reliable across waves (see Appendix 2). Therefore, in the current study, these four scales are included as sub-constructs to model the overall self-control of children. To differentiate between the self-control sub-construct and the overall self-control, the former is hereby referred to as SC. Also, since only teacher reports are available on all four scales, only teacher ratings are used in the current study.

5.3.2. Child, family, and school variables

Several child, family, and variables were selected as possible predictors of the development of self-control. These variables are: child race/ethnicity, age at the kindergarten entry, gender, family structure, parent education, parent expectation, and student-teacher relationship. Student-Teacher relationship was measured using The Student-Teacher Relationship Scale (Pianta & Steinberg, Citation1992), which measured closeness and conflict between the teacher and student using 15 items. Only two scale scores were available in the public database. Higher scale score on the closeness scale means the closer relationship between the teacher and student; vice versa. Higher scale score on the conflict scale means more conflicts between the teacher and student; vice versa. Further details about measures used in the current study could be found in Appendix 1.

5.4. Growth mixture models

As discussed before, multiple growth trajectories are not uncommon in the development of self-control in the early childhood (Coyne & Wright, Citation2014; Diamond et al., Citation2015). Therefore, to account for the possible heterogeneity of the growth trajectory of self-control, growth mixture models (GMMs; e.g., B. Muthén & Shedden, Citation1999) could be utilized, which incorporates one categorical latent variable, often called the latent class, which classifies individuals into different groups with distinct growth trajectories.

5.5. Analytic plan

Analysis proceeded in three steps. First, a curve-of-factors Latent Growth Curve Model (COF-LGCM) was specified to model the overall developmental trajectory of self-control. In the current study, we tested the COF-LGCM with both a linear and a quadratic slope. The robust maximum likelihood (MLR) method was used as the model estimator. Model testing procedures were carried out using package lavaan (Rosseel, Citation2012) in the programming environment R (R Development Core Team, Citation2017). Full information maximum likelihood estimator (FIML) was used to handle missing data. Guidelines of good model fit include a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) value greater than .90 and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) value less than .09 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) was used to compare nested LGCM.

Second, Latent Class Growth Analysis (LCGA) (a type of GMMs) was utilized to explore multiple developmental trajectories of self-control. The same form of growth was specified for all latent classes. Variances of latent factors were constrained to zero, indicating within-class homogeneity—that is, all individuals within the same class have the same growth trajectory (Feldman, Masyn, & Conger, Citation2009). Expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm was used for parameter estimation. Bayesian information criteria (BIC) value and Lo, Mendell, and Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT) were used to compare models and to determine the number of latent classes. The analysis was completed in Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2015).

Third, the impact of child, family, and school variables on the growth trajectories of self-control was investigated. To account for this uncertainty of classification, the weighted multinomial logistic regression was adopted to explore the relationship between the latent growth trajectory membership and the predicting variables, where the probability of belonging to each possible trajectory was used as the weights in the regression analysis. Maximum likelihood (ML) was used as the model estimators. The models were estimated using package nnet (Venables & Ripley, Citation2002) in R (R Development Core Team, Citation2017).

6. Results

6.1. Forms of self-control developmental trajectory

When looking at the overall sample, both the linear and the quadratic COF-LGCM achieved acceptable model fit according to the criteria above (Table ). However, a likelihood ratio test revealed the quadratic COF-LGCM fit significantly better (), indicating a non-linear developmental trajectory of self-control for the overall sample. Therefore, the quadratic COF-LGCM was adopted when further exploring possible multiple growth trajectories in the following analysis. The means and standard deviations of the four scale scores used to model the overall self-control is reported in Table .

Table 2. Mean and standard deviation of the four scale scores at each time point (N = 17,322)

Table 3. Model comparison statistics for latent class analysis

6.2. Heterogeneity of self-control development

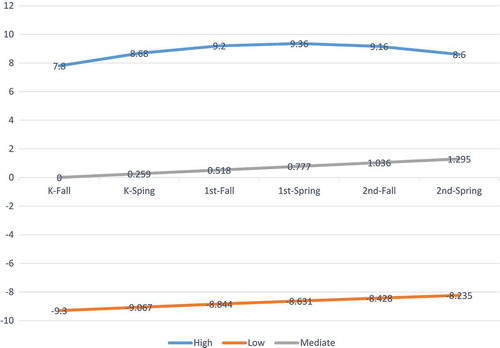

Table displays model comparison statistics from three growth mixture models. As can be seen, the 3-class model fit significantly better than the 2-class model, whereas the 4-class model did not improve model fit. Furthermore, the 3-class model had higher certainty in classification than the 4-class model (). Therefore, in the current sample, three distinct growth trajectories of self-control were found from kindergarten to second grade.

These three growth trajectories can be classified as high, medium, and low levels of self-control (Figure ). As shown in Table , the medium self-control class makes up 33.07% of the whole sample. It was used as a reference group with the initial level of self-control fixed at 0 when entering kindergarten. From kindergarten to second grade, children’s self-control increased linearly by .26 per semester in this group. As shown in Table and Described in Figure , the high-level group (52.89%) entered kindergarten with the initial self-control level at 7.89 (), from which point on children’s self-control developed non-linearly, increasing till spring of first grade and then gradually declining through second grade. The low level group (14.04%) entered kindergarten with the initial self-control level at −9.31 (

). Both the linear (

) and quadratic slopes (

were nonsignificant for this group, indicating children in this group maintained a stable level of self-control from kindergarten to second grade.

Table 4. Growth factor estimates for each latent class

Overall, the results indicate that children enter kindergarten with significantly different levels of self-control, and the differences between latent classes maintained through second grade. In other words, the current study found that self-control exhibited relative stability during early childhood.

6.3. Impact of child, family, and school variables

To investigate the impact of different child, family, and school variables on the development of self-control, two weighted multinomial logistic regressions were conducted, one with the medium-level class as the reference group, and one with the low-level class as the reference group. This way comparison among all three groups could be made. As shown in Table , among the child variables, being black was significantly associated with higher probability of being in the relatively lower level self-control classes (i.e., more likely to be in the medium level than high-level class, and in the low level than the medium-level class). Other ethnicities were not significant predictors. Moreover, being a boy and having a disability were also associated with higher probability of being in the relatively lower level classes. Interestingly, older children were found to be more likely in the high instead of medium-level self-control class. However, age was not a significnat predictor when comparing high vs low or medium vs low-level classes. This indicates that age partly explains the differences in self-control levels between the high and medium-level classes, but may not be significant enough to explain the differences between the high and low or medium and low-level classes. Poverty level was also not a significant predictor of class membership.

Table 5. Estimates from multinomial logistic regression

Only one family variable, single parent household, was a signifiant predictor of membership class, where children with single parents were more likely to be in the lower level self-control classes.

Among the school variables, higher teacher expectation and less teacher-student conflict were both associated with higher probability of being in the higher level self-control classes. Higher levels of teacher-student closeness was also associated with higher probability of being in the high instead of medium or low-level classes. However, when comparing medium and low-level classes, it did not significantly predict class membership.

7. Discussion

7.1. Development of self-control

The current study found three distinct growth trajectories of self-control from kindergarten to second grade among US children, namely, the high, medium, and low-level classes. This finding is consistent with previous studies suggesting heterogeneous growth trajectories of self-control during childhood (e.g., Coyne et al., Citation2015; Coyne & Wright, Citation2014; Diamond et al., Citation2015). Specifically, Coyne et al. (Citation2015) also identified three growth trajectories of self-control using the ECLS-K:1998 sample and looking at children from kindergarten to fifth grade. The three groups also exhibited similar growth patterns, with the high- and medium-level groups demonstrating substantively minor changes and the low-level group remaining stable. Moreover, the three trajectories were relatively stable across time, indicating children entered kindergarten with different rank orders of self-control and that these rank orders maintained during early childhood. This finding is consistent with the relative stability hypothesis that has also been supported by other studies of self-control during this age range (e.g., Beaver & Wright, Citation2007; Coyne & Wright, Citation2014; Gottfredson & Hirschi, Citation1990; Turner & Piquero, Citation2002).

Some researchers have found different numbers of growth trajectories when studying self-control. For example, when dividing the ECLS-K:1998 sample into twins and singletons, Coyne and Wright (Citation2014)found a two-group solution fit the data best: the high-stable and low-stable groups. Vaughn et al. (Citation2009) looked at children from kindergarten to fourth grade in the ECLS-K:1998 sample and found five distinct trajectories. The difference in the number of identified trajectories is not surprising, first, given the different measures of self-control used across studies. The current study used an expanded measure of self-control that included four subscales on the SSRS, whereas other researchers have used the SSRS self-control subscale alone (Vaughn et al. (Citation2009); Vazsonyi & Huang, Citation2010) or some other measures (Diamond et al., Citation2015; Turner & Piquero, Citation2002). Since different measures might tap into slightly different dimensions of self-control, researchers are encouraged to consider how self-control is defined in their own context when applying the results from different studies. Furthermore, the current study followed children from kindergarten to second grade while other studies had different age ranges. Given that childhood through adolescence may be the time when self-control develops most dynamically (Gottfredson and Hirschi (Citation1990), it is reasonable to expect that its developmental trajectories will take on different forms when researchers look at different age ranges. Last but not least, mixture growth model is an exploratory method where the criteria to determine the number of latent classes are subjective and often varied by studies. The current study used the LMR-LRT and BIC values as did some before (Coyne et al. (Citation2015). Other researchers have used the BIC alone (Hay & Forrest, Citation2006) or other criteria such as the AIC (Vaughn et al. (Citation2009) and posterior probabilities (Burt, Sweeten, & Simons, Citation2014; Diamond, Citation2016). Abenavoli et al. (Citation2017) have argued that results of mixture growth models depend heavily on the sample and criteria used by the authors, and therefore, researchers should use caution when generalizing results from different models. In sum, different numbers of developmental trajectories of self-control have been identified across studies using different measures, samples, and analytic methods. However, the consistent finding is that self-control does not develop uniformly. Resutls from the current study also suggest that the different groups are distinguishable early on in childhood. Therefore, it will not be appropriate to use a common growth trajectory to describe the development of self-control for all children.

7.2. Implications for practice

The current study found some child, family, and school variables were significantly associated with different growth trajectories of self-control. More specifically, black children, male children, children with disabilities, and children from single-parent household were less likely to be in the relatively higher level self-control groups. This is consistent with previous findings (e.g., Bennett et al., Citation2005; Chapple et al., Citation2005; Gibbs et al., Citation1998; Lynskey et al., Citation2000) that children with these characteristics tend to be at a higher risk of having low self-control. Moreover, the current study found age was a significant predictor of class membership when comparing the high- and medium-level groups, but not these groups and the low-level group. This indicates that being younger may increase one’s probability of being in the medium versus the high-level group, but it does not contribute to one’s probability of being in the low-level group versus the other two. In other words, the difference between the low-level group and the other two might be due to a real deficit in self-control beyond age difference. Future researchers are encouraged to test this hypothesis.

Above and beyond these child and family background variables, the current study showed teacher-student relationship was also significantly associated with children’s self-control. Like Turner et al. (Citation2005) who suggested higher teacher closeness and more teacher support were related to higher self-control in students, this study revealed that children who had higher teacher expectation, closer relationship with teachers, and less teacher-student conflict were more likely to have relatively higher levels of self-control. While it is unclear whether lower teacher expectation and poorer teacher-student relationship hindered the development of self-control in children or vice versa, the pattern is that children with lower self-control tend to experience these negative school factors more often than their higher self-control counterparts. Since researchers (Barbarin & Aikens, Citation2015) have emphasized the importance of teacher expectation and support in students’ academic and social-emotional development, educators are advised to pay special attention to students with lower self-control and to conveying a high expectation to and cultivating good relationship with these students in order to offset the challenges they already face.

7.3. Limitations and future study

The current study is not without limitations. First, although the ECLS:K-2011 database has a large sample that is nationally representative, we could only access the public database that provided only the scale scores of the self-control measures rather than the original item responses. Even though all these measures had high reliability, we cannot exclude measurement error when applying mixture growth modeling. Future studies should analyze the item responses directly to get measurement error-free estimates.

Also restricted by the database is the number of background variables available. Although the current analysis included a number of important predictors of self-control, other factors such as parents’ levels of self-control, exposure to trauma, earlier education experiences, and early interventions, may also have an impact on children’s self-control development after they enter kindergarten. Including these factors may provide a better understanding of how children’s self-control develop in their social and educational environment.

Moreover, the current study used teacher ratings of self-control. Even though teacher-report is considered more reliable than parent-report and self-report in young children, it is a single source of information and may not capture children’s self-control in other settings. Furthermore, several school variables used to predict group membership reflect teachers’ attitude towards the students (e.g., teacher-student relationship, etc.), and therefore, may be correlated with the teacher-reported self-control. Future researchers are encouraged to replicate the findings with multiple sources of information such as parents or other care providers.

Impact and Implication Statement

The current findings add to the understanding of self-control development during early childhood. The multiple and relatively stable growth trajectories of self-control supported the heterogeneity of self-control development as well as the relative stability theory during eraly childhood. The child, family, and school factors that predicted membership of each trajectory allows for the early identification of children who are at-risk for low self-control. Environmental factors that could be possible areas of intervention are also identified.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Qianqian Pan

Qianqian Pan recently received her Ph.D. from the Research, Evaluation, Measurement, and Statistics program at the University of Kansas. She has been trained in the psychometrics and quantitative methodology with research interests in academic achievement assessments and growth modeling.

Qingqing Zhu

Qingqing Zhu is a school psychology doctoral candidate at the University of Kansas. She has been trained in the cognitive, behavioral, and social emotional assessment and intervention for school age children. Her research interests include social emotional learning and provision of mental health services in the school setting.

The current study is within a larger scope of applying novel quantitative methodology in studying the social emotional development of school age children.

References

- Abenavoli, R. M., Greenberg, M. T., & Bierman, K. L. (2017). Identification and validation of school readiness profiles among high-risk kindergartners. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38, 33–43. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.09.001

- Barbarin, O. A., & Aikens, N. (2015). Overcoming the educational disadvantages of poor children: How much do teacher preparation, workload, and expectations matter. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(2), 101. doi:10.1037/ort0000060

- Beaver, K. M., & Wright, J. P. (2007). The stability of low self-control from kindergarten through first grade. Journal of Crime and Justice, 30(1), 63–86. doi:10.1080/0735648X.2007.9721227

- Beaver, K. M., Wright, J. P., DeLisi, M., & Vaughn, M. G. (2008). Genetic influences on the stability of low self-control: Results from a longitudinal sample of twins. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(6), 478–485. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2008.09.006

- Bennett, P., Elliott, M., & Peters, D. (2005). Classroom and family effects on children’s social and behavioral problems. The Elementary School Journal, 105(5), 461–480. doi:10.1086/431887

- Bernier, A., Carlson, S. M., & Whipple, N. (2010). From external regulation to self-regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children’s executive functioning. Child Development, 81(1), 326–339. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x

- Boutwell, B. B., & Beaver, K. M. (2010). The intergenerational transmission of low self-control. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47(2), 174–209. doi:10.1177/0022427809357715

- Brannigan, A., Gemmell, W., Pevalin, D. J., & Wade Terrance, J. (2002). Self-control and social control in childhood misconduct and aggression: The role of family structure, hyperactivity, and hostile parenting. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 44, 119.

- Buker, H. (2011). Formation of self-control: Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime and beyond. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16(3), 265–276. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2011.03.005

- Burt, C.H, Sweeten, G, & Simons, R. L. (2014). Self-control through emerging adulthood: instability, multidimensionality, and criminological significance. Criminology, 52, 450-487. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12045

- Chapple, C. L., Hope, T. L., & Whiteford, S. W. (2005). The direct and indirect effects of parental bonds, parental drug use, and self-control on adolescent substance use. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 14(3), 17–38. doi:10.1300/J029v14n03_02

- Cooper, B. R., Moore, J. E., Powers, C., Cleveland, M., & Greenberg, M. T. (2014). Patterns of early reading and social skills associated with academic success in elementary school. Early Education and Development, 25(8), 1248–1264. doi:10.1080/10409289.2014.932236

- Coyne, M. A., Vaske, J. C., Boisvert, D. L., & Wright, J. P. (2015). Sex differences in the stability of self-regulation across childhood. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 1(1), 4–20. doi:10.1007/s40865-015-0001-6

- Coyne, M. A., & Wright, J. P. (2014). The stability of self-control across childhood. Personality and Individual Differences, 69, 144–149. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.05.026

- Daly, M., Delaney, L., Egan, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2015). Childhood self-control and unemployment throughout the life span: Evidence from two British cohort studies. Psychol Sci, 26(6), 709–723. doi:10.1177/0956797615569001

- Daly, M., Egan, M., Quigley, J., Delaney, L., & Baumeister, R. F. (2016). Childhood self-control predicts smoking throughout life: Evidence from 21,000 cohort study participants. Health Psychology. doi:10.1037/hea0000393

- Diamond, B. (2016). Assessing the determinants and stability of self-control into adulthood. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(7), 951–968. doi:10.1177/0093854815626950

- Diamond, B., Morris, R. G., & Piquero, A. R. (2015). Stability in the underlying constructs of self-control. Crime & Delinquency. doi:10.1177/0011128715603721

- Duckworth, A., & Steinberg, L. (2015). Unpacking self-control. Child Development Perspect, 9(1), 32–37. doi:10.1111/cdep.12107

- Feldman, B. J., Masyn, K. E., & Conger, R. D. (2009). New approaches to studying problem behaviors: A comparison of methods for modeling longitudinal, categorical adolescent drinking data. Developmental Psychology, 45(3), 652–676. doi:10.1037/a0014851

- Fergusson, D. M., Boden, J. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2013). Childhood self-control and adult outcomes: Results from a 30-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(7), 709–717 e701. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.008

- Gajos, J. M., & Beaver, K. M. (2016). The development of self-control from kindergarten to fifth grade: The effects of neuropsychological functioning and adversity. Early Child Development and Care, 186(10), 1571–1583. doi:10.1080/03004430.2015.1111881

- Gibbs, J. J., Giever, D., & Martin, J. S. (1998). Parental management and self-control: An empirical test of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 35(1), 40–70. doi:10.1177/0022427898035001002

- Gibson, C. L., Sullivan, C. J., Jones, S., & Piquero, A. R. (2010). “Does it take a village?” Assessing neighborhood influences on children’s self-control. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47(1), 31–62. doi:10.1177/0022427809348903

- Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gresham, F. M, & Elliott, S. N. (1990). Social skills rating system: manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

- Hay, C., & Forrest, W. (2006). The development of self‐control: Examining self‐control theory’s stability thesis. Criminology, 44(4), 739–774. doi:10.1111/crim.2006.44.issue-4

- Howse, R. B., Lange, G., Farran, D. C., & Boyles, C. D. (2003). Motivation and self-regulation as predictors of achievement in economically disadvantaged young children. The Journal of Experimental Education, 71(2), 151–174. doi:10.1080/00220970309602061

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

- Li-Grining, C. P. (2007). Effortful control among low-income preschoolers in three cities: Stability, change, and individual differences. Developmental Psychology, 43(1), 208. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.208

- Lynskey, D. P., Winfree, L. T., Esbensen, F. A., & Clason, D. L. (2000). Linking gender, minority group status and family matters to self‐control theory: A multivariate analysis of key self‐control concepts in a youth‐gang context. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 51(3), 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6988.2000.tb00022.x

- Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., … Caspi, A. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Roceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 2693–2698. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010076108

- Muthén, B., & Shedden, K. (1999). Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics, 55(2), 463–469. doi:10.1111/j.0006-341X.1999.00463.x

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (1998–2015). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables [Version 7.4]. (Computer software).

- Ng-Knight, T., Shelton, K. H., Riglin, L., McManus, I. C., Frederickson, N., & Rice, F. (2016). A longitudinal study of self-control at the transition to secondary school: Considering the role of pubertal status and parenting. Journal of Adolescence, 50, 44–55. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.04.006

- Perrone, D., Sullivan, C. J., Pratt, T. C., & Margaryan, S. (2004). Parental efficacy, self-control, and delinquency: A test of a general theory of crime on a nationally representative sample of youth. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 48(3), 298–312. doi:10.1177/0306624X03262513

- Pianta, R. C., & Steinberg, M. S. (1992). Teacher–child relationships and the process of adjusting to school. In R. C. Pianta (Ed.), Beyond the parent: The role of other adults in children’s live (pp. 61–80). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Pratt, T. C., Turner, M. G., & Piquero, A. R. (2004). Parental socialization and community context: A longitudinal analysis of the structural sources of low self-control. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 41(3), 219–243. doi:10.1177/0022427803260270

- R Development Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/

- Ronen, T., Hamama, L., Rosenbaum, M., & Mishely-Yarlap, A. (2016). Subjective well-being in adolescence: The role of self-control, social support, age, gender, and familial crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 81–104. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9585-5

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. doi:10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Sarsour, K., Sheridan, M., Jutte, D., Nuru-Jeter, A., Hinshaw, S., & Boyce, W. T. (2011). Family socioeconomic status and child executive functions: The roles of language, home environment, and single parenthood. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 17(1), 120–132. doi:10.1017/S1355617710001335

- Sektnan, M., McClelland, M. M., Acock, A., & Morrison, F. J. (2010). Relations between early family risk, children’s behavioral regulation, and academic achievement. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25(4), 464–479. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.02.005

- Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self‐control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324.

- The Center for High Impact Philanthropy. (2015). What is early childhood? Early childhood toolkit. Retrieved from https://www.impact.upenn.edu/our-analysis/opportunities-to-achieve-impact/early-childhood-toolkit/what-is-early-childhood/

- Turner, M. G., & Piquero, A. R. (2002). The stability of self-control. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(6), 457–471. doi:10.1016/S0047-2352(02)00169-1

- Turner, M. G., Piquero, A. R., & Pratt, T. C. (2005). The school context as a source of self-control. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(4), 327–339. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2005.04.003

- Vaughn, M. G., DeLisi, M., Beaver, K. M., & Wright, J. P. (2009). Identifying latent classes of behavioral risk based on early childhood: Manifestations of self-control. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 7(1), 16–31. doi:10.1177/1541204008324911

- Vazsonyi, A. T., & Huang, L. (2010). Where self-control comes from: On the development of self-control and its relationship to deviance over time. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 245. doi:10.1037/a0016538

- Venables, W. N., & Ripley, B. D. (2002). Random and mixed effects. In W. N. Venables, B. D. Ripley (Eds.),Modern applied statistics with S (pp. 271–300). Springer, New York, NY.

- Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2016). Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory. and applications: Guilford Publications, New York, NY.

Appendix

Appendix 1. Variable names, data source, original coding, and recoding rules

Appendix 2. Reliability of four measures for the overall self-control