Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study was to investigate to what extent time management skills are associated with general self-efficacy and parental sense of competence, and if there are any differences between individuals with and without cognitive disabilities in these aspects. Material and Methods: The study had a comparative cross-sectional design. Totally 86 individuals with cognitive disabilities (of whom 31 were parents), and 154 without disabilities (of whom 68 were parents) were included (N = 240). The Swedish versions of the Assessment of Time Management Skills (including time management, organisation & planning, and regulation of emotion subscales), General Self-Efficacy, and Parental Sense of Competence scale (including satisfaction, efficacy, and interest subscales) were used to collect data. Results: There were significant differences (p < .001) between individuals with and without cognitive disabilities in all three subscales of Assessment of Time Management Skills and in General Self-Efficacy. Overall, individuals with a cognitive disability scored lower than persons without cognitive disabilities.

A significant difference was observed between parents in all three subscales of time management skills after controlling for age and education (p < .0005). Parents with cognitive disabilities, compared to parents without cognitive disability, scored significantly lower in all measured scales, except for the interest subscale. In parents with a cognitive disability, there was a significant correlation between all three subscales of Time Management Skills and satisfaction. Among parents without a cognitive disability there was a significant correlation between time management; and organisation & planning subscales; and efficacy, and between General Self-Efficacy and time management. Conclusions: Poor time management, planning and organisational skills, as well as a deficit in regulation of emotions may have a negative impact on general self-efficacy and parental sense of competence.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

To handle time effectively is crucial in todays’ society. Successful time management, and planning and organisation skills are not only important at work, but also in family life. Parenthood too puts additional demands on effective time management. Deficiencies in time management skills are common among individuals with cognitive disabilities such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Autism Spectrum Disorder or intellectual disabilities. This might reduce individuals’ self-efficacy and make parenthood even more challenging for them. Despite this fact, the knowledge about the relation between time management skills, self-efficacy and parental competence is limited. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate whether there is any association between time management skills, general self-efficacy and parental sense of competence among individuals with and without cognitive disabilities. The knowledge can be usable in designing interventions for improving time management skill in daily life, and thereby more effective parenthood.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Introduction

Cognitive functions are crucial in individuals’ daily life, including managing a home, organising family life and maintaining employment (Barkley, Edwards, & Laneri et al., Citation2001; Janeslatt, Holmqvist, White, & Holmefur, Citation2018; Mokrova, O’Brien, Calkins, & Keane, Citation2010; Thomack, Citation2012, Valko et al., Citation2010). Being competent in these activities, requires organisational skills, flexible routines and effective use of time. These skills refer to higher-level of cognitive functions, such as self-awareness and executive functioning (Grieve, Citation2008), which in turn are dependent on basic cognitive functions such as visual perception, spatial relations and memory (Katz, Citation2005). Managing time (Thomack, Citation2012) and structuring daily activities are often more troublesome for individuals with cognitive disabilities than for people in general (Toner, O’Donoghue, & Houghton, Citation2006).

In literature, the concept of “time management” is frequently used in conjunction with both cognitive/mental functions, and in time management aspects of activity and participation in daily life. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (WHO. International, Citation2001) classifies time management as a part of executive functions, and defines it as mental functions of ordering events in chronological sequence; and allocating amounts of time to events and activities. Organisation and planning, also are included in executive functions, and defined as mental functions of coordinating parts into a whole, and the function involved in developing a method of proceeding or acting. The concept, managing one’s time in daily life at the activity and participation level, was defined only in ICF-CY (WHO. International, Citation2010) also used for adults. It is defined as managing the time required to complete usual or specific activities, such as preparing to depart from the home (WHO. International, Citation2010). In ICF this function is imbedded in “Carrying out a daily routine”, defined as carrying out simple or complex and coordinated actions, in order to plan, manage, and complete the requirements of day-to-day procedures or duties. For instance, budgeting time and making plans for separate activities throughout the day (WHO. International, Citation2010).

Regulation of emotion, in ICF is defined as a mental function that control the experience and display of affect . It is also described as cognitive and behavioural processes that influence the incident; intensity; duration; and expression of emotions. Regulation of emotion is best conceptualised as a continuum of regulation and organization, considering the complexity and multidimensional nature of the issue (Walcott & Landau, Citation2004; Wheeler Maedgen & Carlson, Citation2000).

People with cognitive limitations due to neurodevelopmental disorders such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism Spectrum Disorder, or intellectual disabilities often have impaired executive functions and poor time management, organisation and planning skills (Barkley et al., Citation2001; Bramham et al., Citation2009; Valko et al., Citation2010). They often experience difficulty in both the sense of time (Holmgren & Adler, Citation1999), how to use and manage their time in daily life (Eklund, Leufstadius, & Bejerholm, Citation2009), and have difficulty organising tasks or activities as well (McGough & Barkley, Citation2004). Furthermore, a number of studies have shown that difficulties in emotional regulation is common among adults with ADHD (Barkley & Murphy, Citation2010; Walcott & Landau, Citation2004; Wheeler Maedgen & Carlson, Citation2000).

Adulthood involves mulitple complex roles such as being a worker and/or a parent. According to the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Article 23:1 (FN, Citation2008; UN, Citation2006), people with disabilities have the right to establish a family and to become parents. However, parenthood places substantial additional cognitive; emotional; and physical demands on this population (Coleman & Karraker, Citation1998). Based on the literature, although individuals with cognitive disability can be just as good parents as everybody else, there is a risk for ineffective parenting among parents with disabilities because of multidimensional constructs of behavioural; affective; and cognitive factors needed for this role (Baumrind, Citation1991; Dix, Citation1991; Stoiber & Houghton, Citation1993; Teti & Gelfand, Citation1991; Teti, Gelfand, Messinger, & Isabella, Citation1995).

Parenting is one key area of interpersonal functioning that is impaired among adults with ADHD symptoms. ADHD often emerges with impairments in educational (Wolf, Citation2001), occupational (Barkley & Murphy, Citation2010; de Graaf et al., Citation2008), and interpersonal domains (Able, Johnston, Adler, & Swindle, Citation2007). Moreover, problems in emotional regulation may make it difficult for parents with ADHD to manage their affect and react calmly and consistently to their children. This might impact their ability to effectively parent (Miller, Gibson, Steeger, & Morrissey, Citation2017) and reduce their parental sense of competence. Parental sense of competence is also closely related to the construct of personal self-efficacy (de Haan, Prinzie, & Mothers’, Citation2009) and parental self-efficacy. Expanding Baundura’s general conceptualisation of self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1977, Citation1989, Citation1982) to the specific case of parenting resulted in defining parental self-efficacy as a potentially central element of a parental sense of competence. Parental self-efficacy is assumed to be parents’ perception of their competence in the parental role. It includes, i.e. ability to parent successfully, and influence the behaviour and environment of children in a manner that would benefit children’s development and success (Bandura, Citation1977; Coleman & Karraker, Citation2000). Low parental self-efficacy is presumed to be associated with negative affects, and feelings of helplessness in the parental role (Bugental & Cortez, Citation1988).

Altogether, the experiences of inconsistency, emotional dysregulation, and failure in time management may lead to decreased self-efficacy and parental sense of competence and finally affect the satisfaction derived from parenting.

Despite the fact that deficiency in time management skills are common among parents with cognitive disabilities, and that cognitive disabilities affect individuals’ perceived efficacy or competency in the parental role, there is limited knowledge on the relation between time management skills and parental competence for this population.

The aim of the current study was to investigate whether there is any association between time management skills, general self-efficacy and self-rated parental competence, and whether there are any differences between individuals with and without cognitive disabilities, affecting executive functioning, in these aspects.

2. Methods

The study had a comparative and cross-sectional design.Three standardised questionnaires were used to collect data: the Swedish versions of the Assessment of Time Management Skills (ATMS-S), Swedish version of General Self-efficacy (S-GSE), and Parental Sense of Competence scale (PSOC). In addition, a study-specific questionnaire was used to collect demographic variables such as sex, age, education level, employment, marital status, diagnosis and/or disability that affects time management skills.

The study was approved by The Regional Ethical Board in Uppsala, Sweden (Dnr 2013/323).

2.1. Outcome measures

Assessment of Time Management Skills (ATMS-S): is a 30-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess awareness and use of organisational skills and strategies, and cognitive adaptations (calendars and lists) to plan and manage daily life tasks. Each item has a four-graded rating scale ranging from never (Thomack, Citation2012) to always (Mokrova et al., Citation2010). The items are described in an earlier publication, evaluating the internal consistency (α = 0.86) in a norm population (n = 241) and test–retest reliability r = 0.89 (White, Riley, & Flom, Citation2013). The English version of the ATMS (White et al., Citation2013) was translated into Swedish, and recently validated in a Swedish sample of individuals with and without cognitive disabilities (Janeslatt et al., Citation2018). The ATMS-S has three subscales measuring three different constructs, time management skills (11) items, organisation & planning (11 items) and regulation of emotion (5 items).

Self-Efficacy was assessed using the Swedish version of General Self-Efficacy (S-GSE): a 10-item scale. The items are rated on a four-point Likert scale (from “not at all true” to “exactly true”). The questionnaire is designed to assess the strength of an individual’s belief in his/her own ability to cope with a variety of novel or difficult situations in life and to deal with any associated obstacles or setbacks. The German version of the questionnaire was developed in 1979 by Matthias Jerusalem and Ralf Schwarzer (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, Citation1995), and later revised and adapted to 26 other languages by various co-authors and has been used internationally (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, Citation1995).

Parental Sense of Competence scale (PSOC) was used to assess parental competence. It is a well-validated, extensively used, questionnaire developed to assess parents’ perception of their parental skills (Rogers & Matthews, Citation2004). The items are rated on a 6-point scale (from 1 = strongly agree to 6 = strongly disagree). Three factors: Satisfaction (an affective dimension reflecting the person’s comfort with the parental role), Efficacy (an instrumental dimension reflecting competence, problem-solving ability, and capability in the parental role) and Interest (level of engagement with the parental role), has been identified in one normative sample (Gilmore & Cuskelly, Citation2009). PSOC has previously been used in assessing parents with ADHD (Sonuga-Barke, Daley, & Thompson, Citation2002). The questionnaire was translated into Swedish and was tried with a small group of adults with cognitive disabilities.

2.2. Procedure

Individuals with cognitive disabilities affecting executive functioning (n = 86) were recruited from psychiatric outpatient, and/or habilitation clinics in Sweden between September 2013 and 2015 to participate in a pilot intervention study (Holmefur et al., Citation2019).Twelve professionals, 10 occupational therapists and two psychologists with extensive experience from clinical work and research with clients with cognitive disabilities, asked patients in their workload to participate. People who were willing to participate, filled out the questionnaires while at the clinic. Attendees were recruited from different parts of the country (both densely populated and rural areas).

Indivduals without cognitive disabilities consisted of a convenient sample of 154 individuals. They were recruited from the general population by the same professionals by asking 1) persons in their vicinity, 2) students at Örebro University who were approched at the start of a lecture, and 3) parents at a preschool.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for sociodemographic variables. To report results on time management and organisational skills, the ATMS-S scores for each subscale were transformed to mean ATMS units, ranging from 0 to 100 by means of Rasch analysis (Janeslatt et al., Citation2018). To determine whether there were any statistically significant differences between the individuals with and without cognitive disability in time management skills (ATMS-S), and general self-efficacy (S-GSE), having controlled for age and education, a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) were performed. The association between ATMS-S, S-GSE and parental sense of competence (PSOC) were calculated with a Pearson correlation coefficient. The alpha significance level was set at <.05 and all reported p-values were associated with two-tailed tests of significance. IBM SPSS (Statistical Package of the Social Science) statistical software, version 24.0. was used for all of the analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

In this study, a total of 240 individuals (86 with cognitive disabilities affecting executive functioning, and 154 without cognitive disability) were included in analyses. Overall, 42% of participants had children (53% had children living at home). Among the sample with cognitive disabilities, 36% were parents. Sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table . More than half of participants were female (62%), and the mean age of them was 33 years old (range 18–66 years). Over half of the attendees (62%) had a job, lived in a relationship (67%), and had higher education (59%) (Table ). However, data on all demographic variables is not available for all participants since some attendees left some questions unanswered, therefore different numbers of n are presented in Table .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

3.2. The correlation between time management skills; general self-efficacy and parental sense of competence in the whole group

The results indicated that there was a statistically significant correlation between general self-efficacy and all three subscales of ATMS-S, regardless of having a cognitive disability or not (Table ). There also was a significant correlation between all three subscales of ATMS-S and satisfaction and efficacy (subscales of PSOC) (Table ).

Table 2. The correlation between Time Management Skills, General Self-efficacy, and Parental Sense of Competence in the whole group

3.3. The correlation between time management skills; general self-efficacy and parental sense of competence among individuals with and without cognitive disabilities

According to the results a negative relation, but not significant correlation, existed between ATMS-S and general self-efficacy among participants with a cognitive disability. Amongst individuals without cognitive disability, a significant correlation was highlighted between time management (subscales of ATMS-S) and general self-efficacy (p < .001) (Table ).

Table 3. The correlation between Time Management Skills and General Self-efficacy based on cognitive disability

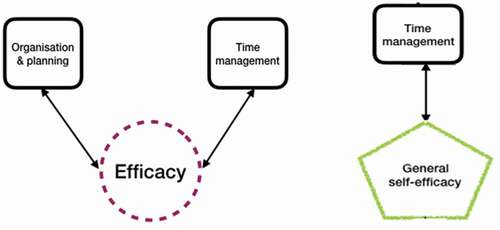

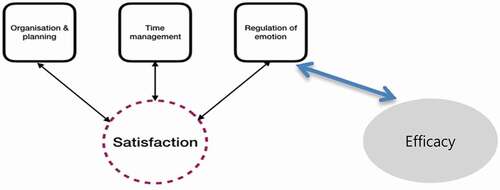

The results indicated that among parents with a cognitive disability there was a statistically significant correlation between all three subscales of ATMS-S and satisfaction (Figure ), and between regulation of emotions and two of PSOC subscales (efficacy and interest, Figure ). However, the association between the regulation of emotion and interest was negative (Table ).

Figure 1. The correlation between Time management skills (ATMS-S, in black boxes) and Parental sense of competence (PSOC, in a circle) in parents with cognitive disabilities.

Table 4. The correlation between Time Management Skills, General Self-efficacy, and Parenting Sense of Competence among parents with and without cognitive disabilities

Among parents without a cognitive disability, there was a statistically significant correlation between two subscales of ATMS-S (time management and organisation & planning, p < .01,) and efficacy (subscale of PSOC, p < .05, Figure ). Furthermore, a statistically significant association was observed between General Self-Efficacy (S-GSE) and time management (subscales of ATMS-S, Figure )

3.4. Differences in time management skills and general self-efficacy among individuals with and without cognitive disabilities

According to the results, there were significant differences (p < .001) between the two groups in all three subscales of self-rated time management skills and general self-efficacy. Participants with cognitive disabilities scored lower in all outcome measures compared to participants without a cognitive disability (Table ).

Table 5. Differences in Time Management Skills and General Self-efficacy among participants with and without cognitive disability

3.5. Differences in time management skills and general self-efficacy among individuals with and without cognitive disabilities with regard to being a parent

According to the results, there was a statistically significant difference between parents with and without cognitive disability in all three subscales of time management skills F (4, 192) = 31.093, p < .000, Wilks’ Λ = .607 after controlling for age, F (4, 192) = 1,276, p = .281, Wilks’ Λ = .974 and education, F(4, 192) = .151, p = .963, Wilks’ Λ = .997 (Table ). However, no statistically significant difference in general self-efficacy was observed between parents with and without cognitive disability (Table ).

Table 6. Differences in Time Management Skills and General Self-efficacy among participants with and without a cognitive disability with regard to having children

3.6. Differences in Parental Sence of Competence among parents with and without cognitive disabilities

Parents with cognitive disabilities compared to parents without cognitive disability scored lower in Parental Sence of Competence (PSOC) (Table ). Though, the differences in efficacy and interest (subscales of PSOC) was not significant after controlling for age and education, F(3, 76) = 1.921, p = 022, Wilks’ Λ = .921. A significant difference was observed in satisfaction between parents with and without disability, F(3, 76) = 3.441, p = 022, Wilks’ Λ = .866

Table 7. Differences in Parenting Sense of Competence, among parents with and without cognitive disability

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate to what extent time management skills are associated with general self-efficacy and parental sense of competence, and whether there are differences between participants with and without cognitive disabilities in these aspects. The results indicated that general self-efficacy was correlated to all three subscales of ATMS-S considering the whole group, regardless of having a cognitive disability or not. Furthermore, a significant correlation was found between satisfaction and efficacy (subscales of PSOC) in the whole group.

However, dividing participants into two groups, based on their cognitive disability, highlighted a negative association between general self-efficacy; time management; and organisation & planing (subscales of ATMS-S) among individuals with cognitive disabilities. This emphasizes the importance of possessing adequate time management and organisation and planning skills for believing in one’s own ability. Furthermore, the results underlined that participants with cognitive disabilities generally scored lower in all outcome measures compared to participants without a cognitive disability.

Our results are supported by earlier studies (Barkley et al., Citation2001; Bramham et al., Citation2009; Solanto et al., Citation2010; Valko et al., Citation2010). Nonetheless, those studies mostly focused on adults with ADHD. The current study also adds that people with a cognitive disability due to other disorders rate their time management skills significantly lower than people without disabilities. However, understanding the underlying reasons of the lower scores in general self-efficacy and time management skills in individuals with cognitive disabilities, and the relation between these constructs and poor time management skills needs closer discussion.

In parents with a cognitive disability, there was a strong significant association between ATMS-S and satisfaction, the subscale of PSOC. In a study by Johnston, Masch and Miller (Johnston, Mash, Miller, & Ninowski, Citation2012), a relation between time management and parental competence in adults with ADHD was found. In their study, they described the importance of organising the home, managing time for oneself and creating routines for the child (Johnston et al., Citation2012). The results of the present study correspond with Johnston and colleagues by adding the relation between time management skills and parental competence. The correlation was also found in this broader sample of persons with other mental disorders. The results demonstrated that parents with a cognitive disability, reported significantly less satisfaction and efficacy compared to parents without a cognitive disability. This might be due to the importance of time management and planning skills in feeling competency and efficiency in managing parental tasks.

In addition, according to our results, time management skills seem to be associated with both general self-efficacy, regardless of being a parent, and parental sense of efficacy regardless of having a cognitive disability or not. A conclusion might be that time management skills play an important role in whether or not people trust in their own ability to handle daily life challenges.

Competent functioning as a parent requires harmony between possessed skills on one hand and belief in one’s skills on the other hand. In parents without cognitive disabilities, associations were found between time management and organisation & planning skills (subscales of ATMS-S), and sense of efficacy as a parent (efficacy subscale of PSOC). No such statistically significant association was observed among parents with cognitive disabilities. A plausible possibility, which has not been investigated in earlier studies, might be that parents who fail to manage time and organise their children’s daily life probably experience a lower level of parental self-efficacy (de Haan et al., Citation2009) that is closely related to the parental sense of competence. Difficulties in parental planning, for instance getting to an appointment on time or planning and organising daily routines (Johnston et al., Citation2012), may affect these parents’ belief in their capability to effectively manage parental tasks. In this way, parents may end up in a vicious circle. Perhaps, a way of handling these complications is to reframe parental planning and concerns about being efficient. Instead, their focus might be placed on the affective dimension of parenthood where they have an opportunity to feel more successful. This result can add further explanations to how a parental sense of competence may be related to time management skills. Parents with poor time management skills have a hard time feeling efficient and living up to the expectations of a good parent; effective, structured and organised in helping a child to meet life’s daily demands. They might feel efficient if they can regulate their emotions, but for feeling satisfied they need to succeed in both managing time; organising and planning; and controlling their emotions.

Another noteworthy result was the negative relation between the regulation of emotion and interest (level of engagement with the parental role) in parents with a cognitive disability. This result is in line with Johnston, Mash and Millers’ (Johnston et al., Citation2012) statement. They claim that there is a relationship between symptoms of ADHD, and deficits in regulation of emotion and consequently reduced the sense of parental efficacy. Obviously, emotions and our ability to successfully regulate them play an important role in our behavioural responses. Parents who are emotionally stable, calm, relaxed and secure may feel that their parenting leads to desired outcomes and therefore feel more efficacious as parents. On the contrary, parents with deficiencies in emotion regulation might feel unsuccessful in their parenting tasks if they can not control their emotions. Deficiences in emotion regulation among parents with ADHD have shown to be one of the mechanisms behind unsupportive parental responses (Mazursky-Horowitz et al., Citation2015).

Earlier studies on parenting and emotion regulation have focused mostly on parents with ADHD (Johnston et al., Citation2012; Mazursky-Horowitz et al., Citation2015). The present study, also included parents with other disorders within the mental health spectrum which might indicate that emotion regulation also affects the parental sense of competence among other groups of parents with cognitive disabilities.

4.1. Methodological considerations

The current study had a broad representation of participants both with and without cognitive disabilities. The participants with cognitive disabilities represented different diagnoses within the mental health spectrum. On one hand, this can be seen as an advantage since the results can be generalized broadly to persons with cognitive deficits who experience poor time management skills. On the other hand, individuals with different disorders may differ in their cognitive deficit profile and insight, particularly individuals with mild intellectual disability, which might be considered as a limitation of the study. However, in the present study, only a few participants with mild intellectual disability (n = 9) were included.

There was also an overrepresentation of participants with a college or university degree. In Sweden, 42% of the general population have that educational level (Statistics_Sweden, Citation2016). In our sample, 69% of the participants without cognitive disabilities, and 41% of the participants with cognitive disabilities had a college or university degree. This could be due to the fact that data collection was performed in three different university cities and participants without a cognitive disability were partly recruited at a univeristy and this may have affected the results. In future studies, this needs to be addressed.

Another limitation of the study was the use of self-report measures exclusively which raises the question of response bias. There always exists a risk that the participants answer in a way that they consider to be more sufficient, or that items are misunderstood (Rosenman, Tennekoon, & Hill, Citation2011), or a limited self-awareness among some participants may lead to an over or underestimation of their own capability that may cause an inaccurate self-reporting. However, the aim of the study was to explore how individuals experienced their own skills and for this purpose, self-report was considered to be a suitable measure. In future studies, if possible, self-report measures should be complemented with objective measures which is an optimal solution to this limitation.

In earlier studies, emotion regulation have been described as an important component in parenting (Johnston et al., Citation2012; Mazursky-Horowitz et al., Citation2015). This was also indicated in this study. However, it is important to bear in mind that the regulation of emotions subscale in ATMS-S consists of only five items and the results must be interpreted with caution. This is an interesting area for further research.

Despite its limitations, the current study is one of the very few investigations that address the association between time management skills, self-efficacy and parental sense of competence in people with and without cognitive disabilities. The results showed that there are differences between the two groups in general, and between the parents with and without cognitive disabilities in particular. Time management skills seem to influence how parents estimate their own parental competence. Therefore, interventions directed to parents with reduced time management skills is needed in order to improve parental competence. Nevertheless, these results need to be confirmed in future studies.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the School of Health Sciences and University Health Care Research Centre, the Faculty of Medicine and Health, Örebro University, Sweden and from the Centre for Clinical Research in Dalarna, grant numbers CKFUU-312401, CKFUU-372541. The authors would like to thank the participants in the study as well as the occupational therapists that assisted with data collection.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hayat Roshanai Afsaneh

The authors are members of a larger research group. The key research activity of the group is development, implementation and evaluation of interventions for persons with poor time management skills due to cognitive disabilities. The group also evaluate instruments assessing different dimensions of executive functions related to managing time in daily life. This paper is a part of a wider project where parents with poor time management skills are studied. Another on-going study with focus on parents, is about evaluating the impact of a standardized occupational therapy group intervention, aiming at improving time management skills in daily life. The intervention is called “Let’s Get Organized (LGO)”.

References

- Able, S. L., Johnston, J. A., Adler, L. A., & Swindle, R. W. (2007, January). Functional and psychosocial impairment in adults with undiagnosed ADHD. Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 97–16. doi:10.1017/S0033291706008713

- Bandura, A. (1977, Mar). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

- Bandura, A. (1989, Sep). Human agency in social cognitive theory. The American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184.

- Barkley, R. A., Edwards, G., Laneri, M., Fletcher, K., Metevia, L. (2001). Executive functioning, temporal discounting, and sense of time in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29(6), 541–556.

- Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. R. (2010, May). Impairment in occupational functioning and adult ADHD: the predictive utility of executive function (EF) ratings versus EF tests. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology : The Official Journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists, 25(3), 157–173. doi:10.1093/arclin/acq014

- Baumrind, D. (1991). Parenting styles and adolescent development. In J. Brooks-Gunn, R. M. Lerner, & A. C. Petersen (Eds.), (pp. 746–758). New York: Garland Publishing.

- Bramham, J., Ambery, F., Morris, R., Morris, R., Russell, A., Xenitidis, K., … Murphy, D. (2009, May). Executive functioning differences between adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autistic spectrum disorder in initiation, planning and strategy formation. Autism, 13(3), 245–264. doi:10.1177/1362361309103790

- Bugental, D. B., & Cortez, V. L. (1988, Jun). Physiological reactivity to responsive and unresponsive children as moderated by perceived control. Child Development, 59(3), 686–693.

- Coleman, P., & Karraker, K. H. (1998). Self-efficacy and parenting quality: Findings and future applications. Developmental Review, 18, 1. doi:10.1006/drev.1997.0448

- Coleman, P. K., & Karraker, K. H. (2000). Parenting self‐efficacy among mothers of school‐age children: Conceptualization, measurement, and correlates. Family Relations, 49(1), 13–24. doi:10.1111/fare.2000.49.issue-1

- de Graaf, R., Kessler, R. C., Fayyad, J., Ten Have, M., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M., … Posada-Villa, J. (2008, Dec). The prevalence and effects of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the performance of workers: results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 65(12), 835–842. doi:10.1136/oem.2007.038448

- de Haan, A. D., Prinzie, P., & Mothers’, D. M. (2009, Nov). fathers’ personality and parenting: the mediating role of sense of competence. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1695–1707. doi:10.1037/a0016121

- Dix, T. (1991, Jul). The affective organization of parenting: adaptive and maladaptive processes. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 3–25.

- Eklund, M., Leufstadius, C., & Bejerholm, U. (2009, Win). Time use among people with psychiatric disabilities: Implications for practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 32(3), 177–191. doi:10.2975/32.3.2009.177.191

- FN. (2008). Konvention om rättigheter för personer med funktionsnedsättning. In Socialdepartementet, (Ed..), (pp. 1–44). Stokholm, Sverige: Edita Sverige AB.

- Gilmore, L., & Cuskelly, M. (2009, Jan). Factor structure of the parenting sense of competence scale using a normative sample. Child: Care, Health and Development, 35(1), 48–55. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00867.x

- Grieve, J. G. L. (2008, Mar 18). Neuropsychology for occupational therapists. Cognition in occupational performance (Revised ed), (pp. 248). Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons Ltd. English. (ed. T, editor.).

- Holmefur, M., Lidström-Holmqvist, K., Hayat Roshanay, A., Arvidsson, P., White, S., & Janeslätt, G. (2019). Pilot study of “Let’s get organized” - a group intervention for improving time management. American Journal of Occupational Therapy (In press).

- Holmgren, H., & Adler, B. (1999). Känslan för tiden rubbas vid psykiatrisk störning. Läkartidningen (pp. 68–70).

- Janeslatt, G. K., Holmqvist, K. L., White, S., & Holmefur, M. (2018, May). Assessment of time management skills: psychometric properties of the Swedish version. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 25(3), 153–161. doi:10.1080/11038128.2017.1375009

- Johnston, C., Mash, E. J., Miller, N., & Ninowski, J. E. (2012, Jun). Parenting in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Clinical Psychology Review, 32(4), 215–228. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.007

- Katz, N. (ed.). (2005). Cognition & occupation across the life span: models for intervention in occupational therapy (2nd ed.). Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association.

- Mazursky-Horowitz, H., Felton, J. W., MacPherson, L., Ehrlich, K. B., Cassidy, J., Lejuez, C. W., & Chronis-Tuscano, A. (2015, Jan). Maternal emotion regulation mediates the association between adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and parenting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(1), 121–131. doi:10.1007/s10802-014-9894-5

- McGough, J. J., & Barkley, R. A. (2004, Nov). Diagnostic controversies in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(11), 1948–1956. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1948

- Miller, R. W. G., Gibson, B. S., Steeger, C. M., & Morrissey, R. A. (2017). Contributions of maternal attention-deficit hyperactivity and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms to parenting. Parenting Science and Practice, 17(4), 281–300. doi:10.1080/15295192.2017.1369809

- Mokrova, I., O’Brien, M., Calkins, S., & Keane, S. (2010). Parental ADHD symptomology and ineffective parenting: The connecting link of home chaos. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(2), 119–135. doi:10.1080/15295190903212844

- Rogers, H., & Matthews, J. (2004, Mar). The parenting sense of competence scale: Investigation of the factor structure, reliability, and validity for an Australian sample. Australian Psychologist, 39(1), 88–96. doi:10.1080/00050060410001660380

- Rosenman, R., Tennekoon, V., & Hill, L. G. (2011, Oct). Measuring bias in self-reported data. International Journal of Behavioural & Healthcare Research, 2(4), 320–332. doi:10.1504/IJBHR.2011.043414

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In W. JW & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON.

- Solanto, M. V., Marks, D. J., Wasserstein, J., Mitchell, K., Abikoff, H., Alvir, J. M. J., & Kofman, M. D. (2010, Aug). Efficacy of meta-cognitive therapy for adult ADHD. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 958–968. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081123

- Sonuga-Barke, E. J., Daley, D., & Thompson, M. (2002, Jun). Does maternal ADHD reduce the effectiveness of parent training for preschool children’s ADHD? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(6), 696–702. doi:10.1097/00004583-200206000-00009

- Statistics_Sweden. Educational attainment of the population in 2016. 2016.

- Stoiber, K., & Houghton, T. G. (1993). The relationship of adolescent mothers’ expectations, knowledge, and beliefs to their young children’s coping behavior. Infant Mental Health Journal, 14(1), 61–79. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0355

- Teti, D. M., & Gelfand, D. M. (1991, Oct). Behavioral competence among mothers of infants in the first year: the mediational role of maternal self-efficacy. Child Development, 62(5), 918–929.

- Teti, D. M., Gelfand, D. M., Messinger, D. S., & Isabella, R. (1995). Maternal depression and the quality of early attachment: An examination of infants, preschoolers, and their mothers. Developmental Psychology, 31(3), 364–376. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.31.3.364

- Thomack, B. (2012, May). Time management for today’s workplace demands. Workplace Health & Safety, 60(5), 201–203. doi:10.1177/216507991206000503

- Toner, M., O’Donoghue, T., & Houghton, S. (2006). Living in chaos and striving for control: How adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder deal with their disorder. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 53(2), 247–261. doi:10.1080/10349120600716190

- United Nation. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Article 23, 1.

- Valko, L., Schneider, G., Doehnert, M., Müller, U., Brandeis, D., Steinhausen, H.-C., & Drechsler, R. (2010). Time processing in children and adults with ADHD. Journal of Neural Transmission, 117(10), 1213–1228. doi:10.1007/s00702-010-0473-9

- Walcott, C. M., & Landau, S. (2004). The relation between disinhibition and emotion regulation in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(4), 772–782. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_12

- Wheeler Maedgen, J., & Carlson, C. L. (2000). Social functioning and emotional regulation in the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder subtypes. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29(1), 30–42. doi:10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_4

- White, S. M., Riley, A., & Flom, P. (2013). Assessment of Time Management Skills (ATMS): A practice-based outcome questionnaire. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 29(3), 215–231.

- WHO. International. (2001). Classification of Functioning Disability, and Health (ICF). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO. International. (2010). Classification of functioning, disability and health, children & youth version (ICF-CY). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Wolf, L. E. (2001, Jun). College students with ADHD and other hidden disabilities. Outcomes and Interventions. Annual New York of Academy Science, 931, 385–395. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05792.x