Abstract

Hong Kong and mainland China’s socioeconomic transitions in the past few decades have led to changes in identity and intergroup attitudes among young adults. However, understanding such changes between local and mainland young adults in Hong Kong’s current social context is limited. This study explores whether local and mainland university students in Hong Kong have different intergroup knowledge, attitudes, and intended behaviors; whether these two groups of students respond to intergroup contact intervention differently; and whether and how has local students’ superior identity been influenced by Hong Kong’s economic, geopolitical, and sociocultural development. Our data came from an intergroup contact intervention among 72 university students in Hong Kong (including 32 local and 40 mainland students, 75% female, MAge = 23). Using a two-arm Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) design, participants were randomly assigned to either an intervention group (a 1-day workshop with incremental levels of contact intimacy) or a control group (a 1-day workshop with limited contact intimacy). Our findings indicate that local university students displayed relatively more negative attitudes toward mainland students and are less responsive to the intergroup contact intervention, which only enhanced local students’ outgroup knowledge but not their attitudes or intended behaviors. This result may suggest local young adults’ transition out of a superior social identity. Our findings call for more university activities to enhance local and mainland students’ mutual understanding and larger-sample research to explore both groups’ perspectives. Future intergroup interventions should address potential barriers such as varied intervention effectiveness by participants’ background.

Introduction

‘Hongkongese’ or ‘Chinese’

Hong Kong’s history had shaped the local residents’ distinctive identity. A long-time colony of the United Kingdom from 1841 to 1997, Hong Kong residents identified themselves more closely with the colonial Hong Kong due to the geographical, political, and cultural distance from mainland China (Carroll, Citation2005). After the Chinese government resumed the sovereignty of Hong Kong in 1997, Hong Kong people’s accessibility to mainland China increased, especially to the neighboring Canton region. Although close boarder does not always reinforce local identity, the fluidity of the boarders often reinforces local identity (Carroll, Citation2005). Despite its geographic proximity with mainland China, Hong Kong people identify ‘deeply with the locale and its urban outlook’ (Hamilton, Citation1999, p. 8).

On the other hand, research and media reports showed some Hong Kong residents’ sense of national attachment to China, which was particularly distinct during international tensions, such as the China-Japan disputes over Diaoyu Islands’ (referred as Senkaku Island by Japan) sovereignty in 1971 and Japan’s controversial education materials about the Nanjing massacre history in 2005, during which many Hong Kong people were feeling particularly nationalistic and self-identified as ‘Chinese’ (Eng, Citation2017; Kwok, Citation2005; Ma, Citation2013; Tam, Citation2007). In particular, many Hong Kong university students self-identified as a group of patriotic Hong Kong Chinese and organized protests and campaigns in both incidents. Through these movements, the participants expressed their empathy and benevolence toward their nation, as well as their anger toward these two incidents. These historical events suggest that the ‘Hongkongese’ and ‘Chinese’ identities coexisted among many Hong Kong people.

The coexisting identities were most visible during the 2008 Beijing Olympic Game, when Hong Kong’s public survey showed many people identified themselves as both ‘Hongkongese’ and ‘Chinese’ (HKU POP, Citation2008). In the same year during a major earthquake in China, volunteers from Hong Kong, including doctors, social workers, and others, joined the disaster relief work and provided medical and psychological support (Mingpao Daily News, Citation2008). The Hong Kong government and local nonprofits also built close partnerships with Sichuan Province and donated over HKD 23 billion to facilitate post-earthquake reconstruction (Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau, Citation2019).

However, a sentiment of resistance to Hong Kong–mainland China integration emerged in the past decade. Symbolic events included the 2012 ‘anti-Chinese tourists’ movement (a series of movements against cross-border traders monopolizing Hong Kong people’s living pace and mainland Chinese tourists competing for Hong Kong’s resources), the 2014 ‘Occupy Central’ movements (also called the Umbrella Revolution, a series of street protests against the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress’s decision on electoral reform), and the 2019 ‘anti-Extradition Bill’ protests. (Lai, Citation2012; Ng, Citation2014; Sum, Citation2019) From 2008 to 2017, Hong Kong people experienced an increasingly strong affiliation to the Hongkongese identity and a plummet Chinese identity (HKU POP, Citation2017). The interplay of social identity and social context seems unneglectable underneath these events. The Hongkongese versus Chinese identity appears to be increasingly inconclusive.

Hong Kong people’s attitudes toward mainland Chinese

These social transitions also contributed to Hong Kong residents’ everchanging attitudes toward their mainland counterparts. By reviewing the colonial history, economic development, and everyday nationhood from 1960 to 2000, local scholars argued that the Hong Kong locale identity was not matured until late-1970s (Ng et al., Citation2006). Due to China’s closed boarder before late-1970s, Hong Kong people rarely had contact with mainland Chinese. Therefore, Hong Kong people’s attitudes toward mainland Chinese were mostly shaped by indirect experiences, especially news media.

Media stereotyping effect suggested that people use stereotypic media content, such as a deliberately portrayed TV character, to form opinions across group affiliations (Ramasubramanian & Murphy, Citation2014). Such media stereotyping led people to overgeneralize feelings and formed prejudiced attitudes associated with the outgroup members, disregarding the individual differences (Allport, Citation1954; Brown, Citation2010). In Hong Kong, the TV drama character ‘Ah Chan (阿燦)’, a mainland stowaway who was countrified, uneducated, and indolent, was used as a stereotype to describe mainland Chinese and later became a vital element in Hong Kong people’s prejudiced attitudes toward mainland Chinese.

Whereas the 1960–70s generation had a more uncertain identity, Hong Kong people in the 1980–2000s began to clearly distinguish between ‘Hongkongese’ and ‘mainland Chinese’, manifesting a ‘self-protecting’ and an ‘exclusive attitude’ toward immigrants from mainland China (Lui, Citation1997, pp. 108–112). After 1997, the sudden increase in mainland tourists had a double-edged impact on Hong Kong people’s attitudes toward mainland Chinese. On the one hand, research consistently reported a superior ‘Hongkongese’ identity, seeing mainland Chinese as impolite, uneducated, and obsoleted. On the other hand, Hong Kong people positively welcomed the mainland tourists for the ensuing economic benefits (Chan, Citation1996; Leung, Citation1999; Shen et al., Citation2017; Yeung & Leung, Citation2007).

Since 2010, top mainland students started entering Hong Kong’s tertiary education, leading to increasing interpersonal contact between local and mainland university students. Different from the tourists, these students are a group of elites who ranked top in China’s university admission exams. Due to the lack of contact between the two group of students, a deep intergroup misunderstanding and stereotyped attitude exists (e.g., Lee & Chou, Citation2018). However, little is known about the attitude change in the current generation, especially among the young adults, who were the main force in the 2019 protests (SCMP, 2019). Given the historically superior Hongkongese identity, would Hong Kong students perceive a sense of inferiority as they interact more with this new generation of mainland elites? Are there group differences in Hong Kong and mainland students’ misunderstandings and stereotyped attitudes toward each other? When given the opportunity to interact with the other group, would Hong Kong students be open to change their attitudes and perceptions toward mainland Chinese students? How would their attitude change compare with mainland Chinese students’?

Additionally, research rarely explored mainland university students’ attitudes toward Hong Kong people. An earlier qualitative study suggested that mainland Chinese university students’ stereotypical attitudes toward Hong Kong students included less warmth and greater social cynicism, which is associated with Hong Kong people’s sense of superiority that is embedded in their westernized values and beliefs (Guan et al., Citation2010). However, whether these stereotypical attitudes remain unchanged today is unknown.

Social identity and attitude change

Previous research suggested that people’s outgroup misunderstandings, prejudiced attitudes and intended behaviors may be subjected to their social identity and group saliency. When contacting with outgroup members, how people perceive their group’s status and power could drive different intergroup attitude and behaviors (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979; Hornsey, 2008). When a person’s social category is salient, one may hold a superior social identity than the inferior group, generating sympathy yet negative attitude toward the inferior group. However, when one’s social category saliency is challenged, individuals may tend to selectively perceive the competing group members as negative to mentally guard their group saliency (Hewstone, Citation1990). Recent waves of impact from mainland China have constantly challenged Hong Kong people’s superior status, which could lead to local residents’ identity transitions, particularly among the younger generation. Will these Hongkong young generation people reduce their negative beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors toward their mainland peers with increased contact opportunities or they hold the long lasting superior Hongkongese group status which may impede Hong Kong students’ attitude change? One recent study identified an intertwined mentality among Hong Kong people that involves a sense of superiority as well as a feeling of deprivation (Chen et al., Citation2018). However, this study focused on the Hongkong local and mainland Chinese tourists where the contact level was low. The explanations for how such intertwined mentality may affect Hong Kong people’s attitudes toward mainland Chinese were also not yet discussed.

The current study

Despite the large amount of Chinese young adults studying and living in Hong Kong, research of their interacting experiences with local young adults is rare. Our study contributes to the literature by examining the mutual perceptions, attitudes, and behavioral tendencies between local and mainland university students in Hong Kong in a unique social context (i.e., after the protests in 2019). Given the sociocultural differences between Hong Kong and mainland China, we hypothesize that the two groups of students hold divergent knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral tendencies toward each other. Reviewing the economic, geopolitical, and sociocultural development, we hypothesize that Hong Kong university students’ superior group identity is changing in the current generation. Referring to social identity research, we will discuss the possible mechanisms of the attitude formation toward mainland Chinese, as well as the shift of Hong Kong people’s superior identity. Specifically, this research answers three questions:

Do local and mainland university students in Hong Kong have different levels of intergroup knowledge, attitudes, and intended behaviors?

Do local and mainland university students in Hong Kong respond differently to intergroup contact interventions?

Based on the differences between local and mainland university students’ responses, whether and how has Hong Kong university students’ superior identity been influenced by the local economic, geopolitical, and sociocultural development?

Materials and methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Human Ethics Research Committee from The University of Hong Hong to ensure research integrity and confidentiality. We recruited participants from The University of Hong Kong campus and online platform, one of the largest public universities in Hong Kong. Participants were informed of the study content and procedure (i.e. an intergroup contact workshop, as described below). Written informed consent were obtained before the study began.

Our data came from an intergroup contact intervention workshop that aimed to enhance the mutual understanding between local and mainland university students in Hong Kong (Ng et al., Citation2023). The one-day workshop included three intergroup contact activities, targeting cognitive, interpersonal, and emotional level of contact (see sections below for details). Data were collected through self-reported questionnaires before (T0), after the one-day intervention (T1), 2-week post intervention (T2), and 1-month (T3) after the intervention. The convenient sample included 32 local students and 40 mainland Chinese students (75% female; MAge = 23.22, SD = 3.80), who understand Mandarin and Cantonese (Hong Kong local dialect) and are currently registered university students in Hong Kong.

Measures

To ensure the cultural sensitivity of the study, measures of knowledge, attitude and intended behavior were constructed by the research team using an expert panel approach. The expert panel comprised social work and psychology professors who are experienced in working with university students in Hong Kong. Structure and items of the questionnaires were adapted from the Knowledge, Attitude, and Intended Behavior scales developed by Gao and Ng (Citation2021). The detailed process of questionnaire construction and sample scale items are described in the previous study (Ng et al., Citation2023).

The questionnaire battery included a 13-item Knowledge scale, a 10-item Attitude scale, and an 11-item Intended Behavior Likert scale that was rated on a scale of 1– 4 (Ng et al., Citation2023) (see Appendix 1). Knowledge and Attitude scales includes statements of misperceptions and prejudiced attitude statements towards the outgroup members. The answer ranged from ‘mostly agree’ to ‘mostly disagree’. Higher scores on the Knowledge and Attitude scales indicate more positive perceptions and less prejudiced attitudes toward the outgroup. Intended Behavior includes statements asking the participants how likely they might present positive behaviors towards the outgroup members. Following the same order of answer arrangement as the Knowledge and Attitude scales, higher scores on the Intended Behavior scale indicates more negative behavioral tendencies toward the outgroup members. Hence, it was reversely coded to ensure the consistency of interpretation and robustness (Sybing, Citation2023). The items were scripted in the same way for local and mainland university students. The internal reliability yielded 0.85, 0.94, and 0.93 for the three scales respectively, which suggested satisfactory reliability (Pallant, Citation2010). The Pearson product moment correlation analysis suggested satisfactory measurement validity. The test detected significant item-total correlations in all three scales. The Pearson’s r of each item was found larger than the r table product moment at a 5% significance level, with N = 70 (Chee, Citation2016).

Participants completed the survey in a classroom setting independently. The researcher welcomed participants and settled them down in the classroom with soft music played for mood regulation. To prevent external distractions, no communication or use of personal electronic devices were allowed during questionnaire administration. Participants’ knowledge, attitudes, and intended behaviors toward the outgroup were collected at baseline (T0), post-intervention (T1), 2-week post intervention (T2), and 1-month post intervention (T3). The intervals were chosen specifically to understand the trajectory of intervention effect. Regarding the maintenance of the intervention effect, research suggested the general short-term effects of the intergroup contact interventions last for one month (Lemmer & Wagner, Citation2015). Given this one-day intervention was designed for a short-term improvement of Knowledge, Attitude, and Intended Behavior, and to provide a more detailed trajectory of this short-term effect maintained, we performed assessment at 2-week post intervention (T2) and 1-month post intervention (T3).

Intervention

Using a two-arm Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) design, participants were randomly assigned to either an intervention group with incremental levels of contact intimacy or an active control group with limited level of contact intimacy. Due to the feasibility of the study, we incorporate an active control group to encourage more student participants to join our workshop. According to Allport (Citation1954), one of the key elements in an intergroup contact activity is to include the participants with mixed membership equally. The key ingredient of our intervention is intergroup contact instead of the workshop’s content itself. The control group mimicked the schedule of the intervention group, but the control group did not receive the essential intergroup contact component. In other words, the workshop itself is just a medium of delivering our intervention (which both groups shared), but more importantly, our intervention focus is actually the interaction with outgroup members during the workshop. Hence, during the one-day intergroup contact workshop, the intervention and the active control groups shares same activities yet only intervention group performed group reallocation after the first activity (cognition level of contact) (see Appendix 2 for detailed description). Four social work practitioners were trained by the principal investigator to use a standard rundown and instructions to facilitate the groups. The instructions including greeting message, guidance on each level of contact activities and group debriefing. Both intervention and control groups were built by using the same ice breaking activity. Clear instructions (e.g. let’s move to our next activity, which is to …) were given to the group members before altering to the following activity. The intervention and control group activities were facilitated by two social work practitioners who spoke Mandarin and Cantonese, respectively. This bilingual arrangement ensured transparent and smooth communication.

The intervention and the control group both began with the cognitive-level activity under the same group membership setting, which includes one group of local students and another group of mainland Chinese students. The cognitive-level activity requested each group to list what misunderstandings the outgroup members might pertain for them. Afterwards, the groups were reallocated in the interpersonal- and emotional-level activities. The reallocation was performed to meet the successful intergroup contact intervention criteria, where each group should be formed with a balanced number of ingroup and outgroup members (Allport, Citation1954). The intervention group then consisted of an equal number of local and mainland Chinese students, while the control group’s membership remained unchanged. The interpersonal-level activity required the students to clarify the misunderstandings generated by the outgroup members in the first session. Last, the emotional-level activity was a collaborative task, requesting the students to create a drama topic ‘integrating local and mainland university students’. More intervention details are reported elsewhere (Ng et al., Citation2023).

Data analysis

Data were handled in a confidential manner with personal information disguised. To ensure the reliability of the result, data cleaning was conducted following the steps of checking for errors and finding and correcting the errors in the data file (Pallant, Citation2010). The attrition rate was 2.7%. Missing data were handled using the last observation carried forward method (Pallant, Citation2010).

Chi-square analysis was conducted to compare the demographic characteristics between the local and mainland university students. Pearson correlation was conducted to present the research measure correlations overtime. To answer Research Question 1, the whole sample was used. Independent sample t-test was conducted to compare the difference in local and mainland students’ outgroup knowledge, attitudes, and intended behaviors. To answer Research Question 2, both intervention and control group was analyzed. The intervention group was our focus while the control group serves as ac comparison. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare how local, and mainland Chinese university students responded to the activities in the intervention and control groups overtime. Respectively, small, medium, and large effect sizes were indicated by ηp2=.01, ηp2=.06, and ηp2=.14 (Cohen, Citation1988). Additionally, paired sample t-test was conducted to examine the within-group changes in knowledge, attitudes and intended behaviors among local and mainland Chinese university students. We used Cohen’s d to denote effect sizes. By convention, d = 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 indicate small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, Citation1988). To answer Research Question 3, in addition to our quantitative analysis results, we also reviewed local documents and used previous qualitative research findings to gauge Hong Kong young adults’ underlying social identity transitions.

Results

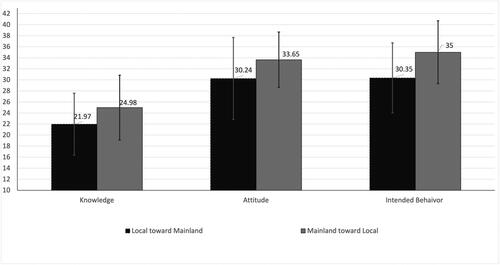

The demographic characteristics are described in Appendix 3. Means and standard deviations of the research measures are described in Appendix 4. Independent t-tests (see ) suggested significant pre-intervention (T0) group differences in intergroup Knowledge (F = 5.01, p = .03), Attitude (F = 5.51, p = .02) and Intended Behavior (F = 11.02, p < .001) between local and mainland Chinese university students in Hong Kong, with the largest group difference in the intended behavior domain. On average, the result suggested mainland Chinese university students held more positive Knowledge (M = 24.98, SD = 5.87), Attitude (M = 33.65, SD = 5.01), and Intended Behavior (M = 35.00, SD = 5.68) toward local university students. In contrast, local university students held more negative Knowledge (M = 21.97, SD = 5.62), Attitude (M = 30.24, SD = 7.43), and Intended Behavior (M = 30.35, SD = 6.36) toward mainland Chinese university students. This indicates Hong Kong university students had relatively more prejudiced attitudes toward mainland university students studying in Hong Kong.

Figure 1. Intergroup knowledge, attitude, and intended behavior means and standard deviation between local (LS) and mainland (ML) university students in Hong Kong pre-intervention (T0) (N = 72).

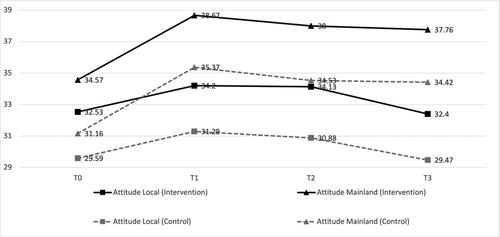

This result indicates the significant differences between the local and mainland university students regarding responsiveness to the intervention, especially on intergroup attitude change. The large effect size indicates the significant positive intervention effect on students’ attitudes lasted for one month.

Repeated measure ANOVA was conducted to compare the intergroup Knowledge (), Attitude () and Intended Behavior () change in local and mainland students over time between the intervention group and the control group. We found significant large-sized group × time effect on Attitude (F = 5.97, ηp2 = 0.149, p =.001). The control group revealed no significant overtime differences in Attitude between local and mainland Chinese university students. Between-group differences were detected in intergroup Attitude in intervention (F = 6.03, ηp2 = 0.151, p =.02) and control groups (F = 7.32, ηp2 = 0.177, p =.01); between-group differences were also detected in the intergroup Intended Behavior in the control group (F = 14.12, ηp2 = 0.293, p =.001). These results indicate the local and mainland students responded to the intergroup contact activities differently. Moreover, within-group difference of intergroup Knowledge and Attitude was detected in the intervention and control group, indicating significant changes in Knowledge and Attitude in local and mainland students independently in both intervention and control groups. These results may suggest local and mainland students responded differently to the intervention over time, specifically in intergroup Attitude.

Table 1. Between by within group comparisons in the intervention and control groups: Repeated measures ANOVA of Knowledge between local (LS) and mainland student (MS) in both intervention (N = 36) and control (N = 36) group.

Table 2. Between by within group comparisons in the intervention and control groups: Repeated measures ANOVA of Attitude between local (LS) and mainland student (MS) in both intervention (N = 36) and control (N = 36) group.

Table 3. Between by within group comparisons in the intervention and control groups: Repeated measures ANOVA of Intended Behavior between local (LS) and mainland student (MS) in both intervention (N = 36) and control (N = 36) group.

Paired-sample t-tests revealed significant within group differences of intergroup Attitude () students in both intervention and control groups. Only mainland Chinese university students showed significant improvements in Attitude overtime. No significant within group Attitude were revealed among local students (see Appendix 5a & 5b). Specifically, mainland students’ attitude improved with a large effect size observed after the intervention (T1) (Intervention group: d = 1.14, p < .001; Control group: d = 0.6, p = < .02), 2-week after workshop (T2) (Intervention group: d = 0.8, p = .002; Control group: d = 0.5, p = .04), and 1-month after workshop (T3) (Intervention group: d = 0.8, p = .002; Control group: d = 0.5, p = .05). Both local and mainland students’ Knowledge improved after the workshop (T1) (MLS = 28.93; MMS= 29.24), 2-week (T2) (MLS = 30.67; MMS= 28.90) and 1-month postintervention (T3) (MLS = 31.12; MMS= 31.62) in the intervention group. The maintenance effect of Knowledge changed was not observed in the control group. No within-group effect was revealed in the intervention and control group among either local or mainland students.

Figure 2. Trends in attitudes among local and mainland university students in Hong Kong in the intervention and control groups.

The result suggested that compared with the local students, the mainland university students were more responsive to the intervention. While the intergroup intervention increased local and mainland students’ knowledge of each other, the intervention further improved mainland students’ attitudes toward local students over time and their intended behaviors immediately after intervention.

Discussion

Prejudiced attitudes toward mainland Chinese students

Answering our first research question, we found that Hong Kong university students had relatively more prejudiced attitudes toward mainland university students studying in Hong Kong. Our finding is consistent with several previous studies that showed Hong Kong residents held negative attitudes toward mainland Chinese from a sociocultural perspective (Chan, Citation1996; Leung, Citation1999; Shen et al., Citation2017; Yeung & Leung, Citation2007). For instance, a qualitative study of 38 Hong Kong residents found cultural stereotype a significant contributing factor to their prejudiced attitudes. Although most of their study participants rarely directly witnessed mainland tourists’ uncivilized behaviors, they had a stereotypical image of discourteous and ill-mannered mainland Chinese individuals (Shen et al., Citation2017). That being said, Hong Kong’s economic transitions may have reshaped young people’s identity.

Our finding is also consistent with previous research on social identity that individuals strive for holding a sense of superiority for their in-group membership, especially when their identities are being challenged (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986). To maintain a superiority identity, people may either emphasize the similarities among in-group members or exaggerate their differences from the out-group. This may be achieved through the media stereotyping effect (Ramasubramanian & Murphy, Citation2014), which categorizes other groups by using stereotyped images that serve the in-group positively and the out-group negatively. Such effects could be long-term, cognitive, and affective (Bryant & Thompson, Citation2002). Hence, Hong Kong residents’ superior identity may have solidified their social categorization of Hongkongese and mainland Chinese. Through media, the mainland-Chinese stereotype was ingrained in Hong Kong people’s mind, which could reinforce their prejudiced attitudes.

Our finding was particularly interesting given that the local and mainland young adults shared the same living and study environments but showed different levels of prejudiced attitudes. This finding is contradictory to previous research, such as Ma’s (Citation2006) field study in Dongguan (a Chinese city adjacent to Hong Kong) that suggested the contact between Hong Kong and mainland people differed by people’s social class. Meeting mainland Chinese in different social classes (i.e., working class, middle class, and young elites) may expand local residents’ understanding of mainland Chinese, hence reducing locals’ stereotyped image of mainland Chinese.

Our finding has two possible explanations. First, our research population and contact level differed from Ma’s (Citation2006) previous study, which focused on Hong Kong businesspeople and white-collar working class who had their second homes in mainland China. Their deeper levels of daily contact with mainlanders hence may have brought them more diverse perspectives. In contrast, the local university students in our study rarely visited or lived in mainland China (see Appendix 3). Second, it takes time and effort to change individuals’ attitudes. Apart from the media stereotype effect on local residents’ prejudiced attitudes, the lack of contact between mainland and local students could further deepen their misunderstanding of each other.

Varied effects of intergroup contact on local and mainland students

Local students’ resistance to identity transitions

Our second finding was that local students were less responsive to the intergroup contact intervention, particularly in their attitudes and intended behaviors. Although we did not measure the underlying mechanisms directly, we conjecture there might be a mental resistance to transition out of a superior identity. Fielding and Hornsey (Citation2016) claimed that how people perceive their group status and power could drive different intergroup behaviors. In line with this argument, our study seems to suggest that when Hong Kong young adults’ group status alternated between Hongkongese and mainland Chinese, they might perceive a sense of deprivation that led to resistance in changing attitudes and intended behaviors toward their mainland counterpart.

Previous research in social identity suggested that when people identify themselves as certain social category, such as a social group or an ethnic group, their social identities are cognitively represented as group prototypes that determine their beliefs, attitudes, feelings, and behaviors (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986). People would also optimize a balance between minimizing in-group differences and maximizing intergroup differences (Terry et al., Citation1999). Therefore, local university students may identify themselves as Hongkongese, a social category that deeply influences their self-concept. Assimilation to the perceived in-group prototype might lead to their resistance in changing attitudes and intended behaviors toward outgroups.

Another possible explanation on this ‘mental resistance’ is the motivation of correcting cognitive dissonance. Festinger (Citation1957) suggested that individuals have the inner motive to harmonize beliefs with behaviors. When one’s beliefs are inconsistent with their behaviors, individuals will change either their beliefs or behaviors to eliminate such dissonance. It is possible that the intergroup contact intervention challenged the local university students’ preexisting belief in a superior identity. Thus, resisting changes in attitudes might be interpreted as a solution to reduce such cognitive dissonance.

Additionally, identity threat might also explain such mental resistance. Research suggested that threats to self-identity contributes to individuals’ resistance to change (Murtagh et al., Citation2012). This could also happen when a group is experiencing social identity threat. Social identity theory acknowledges that social groups generate social norms and facilitate emotional attachment among group members, which provides in-group characteristics for members to define their self-identity (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). Once individuals internalize their membership in a social group, their psychological boundary between self and group becomes blurred (Hogg et al., Citation1995). Considering the local university students’ Hongkongese social identity is likely intertwined with their self-identity, while experiencing a collective Hongkongese identity threat, they may internalize it as a self-identity threat, which may lead to their resistance in changing attitudes and behaviors.

Mainland students’ changing perceptions toward locals

The mainland students in our study showed relatively positive attitudes toward local students and were more responsive to the intergroup contact intervention. Multiple studies had argued that the nature of the out-group attitude is associated with the perceived threat from the out-group (Branscombe & Wann, Citation1994; Duckitt & Mphuthing, Citation1998; Grant & Brown, Citation1995; Struch & Schwartz, Citation1989). Therefore, the mainland students may be more prone to attitude and behavior changes because of their lessened identity threat.

The socioeconomic gap between local and mainland Chinese students has narrowed due to mainland’s rapid economic development in the past few decades. More recently, a young Chinese elite group is increasingly evident in Hong Kong’s daily life. Starting from 2010, Hong Kong universities have attracted a growing number of selective students from mainland China, who top-scored in the competitive national university admission exam (Cheng et al., Citation2010; Li, Citation2013). From 2002 to 2014, Hong Kong universities had almost ninefold enrollment growth of mainland undergraduate students, who account for over 70% of non-local students in Hong Kong (University Grants Committee, Citation2021). To the local students, some felt threat from the mainland ‘elite’ group’s academic and career achievements in Hong Kong (Feng, Citation2013). To the mainland students, many of them consider social and cultural experiences equally important as academic development (Li & Bray, Citation2007). A qualitative study with 25 mainland undergraduate students in Hong Kong found an ‘elite’ self-identity helped some participants confront the ‘anti-mainlanders’ discourse. Contrary to the locals’ accusation of mainlanders ‘exhausting public resource’, some mainland students believed that their study in Hong Kong brought ‘competitiveness and reputation to the universities’ (Xu, Citation2015).

In addition, mainland Chinese students may possess a more stable national identity. China has a long history of civilization and a continuous cultural impact on the region. The current-generation young adults from mainland therefore may develop a sense of superiority (Wu, Citation2000). China’s outstanding economic performance in the past 25 years has enhanced its global status and provided Chinese students studying overseas a strong cultural self-confidence (Inkster, Citation2018; Wu, Citation2000). With a stronger affiliation to their power-growing nation, mainland Chinese students might have more confidence as a Chinese compared with Hong Kong students. Thus, they may have a lower motivation to maintain the in-group self-esteem through negative attitudes toward outgroups. From a national identity perspective, mainland students see Hong Kong as a part of their own country with distinct culture and history (Ma & Holford, Citation2023). Categorizing Hong Kong students as in-group members could be another possible reason that mainland students hold more positive attitudes toward local students.

Transition out of a superior identity: where to land?

Our third finding was that the local university students in our sample appeared to experience a collective resistance to change prejudiced attitudes and behavior tendencies toward their mainland counterparts. Based on our finding, we speculate that Hong Kong’s young adults may be currently transitioning out of a superior identity, yet how such identity transition will develop remains undetermined.

One possibility is that local students may become less motivated to participate in joint activities with mainland students. In a larger picture, we speculate that local residents may interact with mainland immigrants less frequently and in a more conservative manner. As suggested by previous literature, when one’s category saliency is challenged, individuals tend to selectively experience the competing group members as overly negative (Hewstone, Citation1990). In our case, some local students may swing between holding a superior identity and feeling a sense of deprivation when encountering the growing number and quality of mainland Chinese students. It is possible that the diminishing Hongkongese group salience would lead to more protective behaviors in maintaining the superior identity.

Another possibility is that the fading group salience may make local residents perceive the Hongkongese and mainland Chinese identities as less mutually exclusive. As a result, they may gradually replace the superior identity with a more equal status when compared with mainland Chinese. This trend of identity equality has emerged in 2000s, when mainland Chinese began to describe Hong Kong people as ‘Kong Chan (港燦)’, who held false pride and superior mentality hence despising mainland Chinese groundlessly. This was a reversed stereotypical Hongkongese image corresponding to ‘Ah Chan’. Among many mainland residents, such stereotype may be reinforced by mainland’s economic development and its financial contribution to Hong Kong. For example, mainland China experienced rapid economic growths with an average quarterly GDP growth of 9.91% from 1979 until 2010 (Trading Economics, Citation2011). The mainland Chinese tourist industry in 2018 generated an added value of HKD 214.8 billion, which represents a sixfold growth since 2003 and equals to 7.6% of GDP in Hong Kong. Mainland Chinese tourism also created 621,100 jobs, or 16.3% of total employment in Hong Kong (Census and Statistics Department, Citation2019).

Our finding on the transition of Hong Kong people’s superior identity is consistent with previous research. As mentioned before, some residents perceived two intertwined mentalities when encountering mainland Chinese: a sense of superiority and a feeling of deprivation (Chen et al., Citation2018). Chen et al. (Citation2018) also concluded that under the Chinese tourist wave, many residents recognized the economic benefits but held negative attitudes toward mainland tourists. Similar findings were discovered in a previous survey with 228 hotel employees in Hong Kong, which found that participants had negative perceptions and attitudes about mainland tourists’ appearance, personalities, and behaviors (Yeung & Leung, Citation2007). In short, these studies inferred that local residents appear to continue holding a superior identity due to Hong Kong’s higher level of civilization while also sharing a sense of deprivation due to the economic impact brought by mainland Chinese visitors.

Limitations and implications for future research and practice

Our study has several limitations. First, given our small sample size and our study setting in one university, our findings may not be generalized to the general young adult population in Hong Kong. Given that our sample came from an intergroup contact intervention, the participants may also only represent students who are more interested in interacting with the outgroup, which may present a selection bias. Although the mainland and local students’ demographic background differs to certain extent (such as educational attainment and religious affiliation), we could not test potential moderation effects due to our small sample. Therefore, further research should include larger samples and test the replicability of our findings among other young adult populations.

Second, using a social identity theoretical framework, we speculate our findings to be a result of local young adults’ transitioning out of a superior identity. However, we acknowledge that this is only one of many possible explanations based on the literature and the region’s contemporary history. Although the locals’ prejudiced attitudes toward mainland Chinese seem sustained in the current generation, the underlying motivation of maintaining these attitudes could be different from previous generations. Thus, our study is explorative by nature, and our findings should be interpreted with caution. Future research should use qualitative interviews to understand both Hong Kong and mainland students’ attitudes and examine how their identities change over time. The future study may also consider incorporating other theories (e.g., modern economic and political theory) to explain the differentiated responses between local and mainland students to the same intergroup contact intervention.

Despite these limitations, our study updates the understanding of the current-generation Hong Kong young adults’ intergroup attitudes toward mainland Chinese students. This research responds to the calling in the current literature to shift the focus on one-way perception from Hong Kong to mainland Chinese to the mutual perception between these two groups. Given mainland tourists’ tremendous influence on Hong Kong’s economic, social, cultural, and community environments, much of previous research focused on Hong Kong residents’ perception toward mainland tourists (Chan, Citation1996; Leung, Citation1999; Shen et al., Citation2017; Yeung & Leung, Citation2007). However, as these two groups’ contact became more frequent and in-depth than the previous tourists-host relationship, more research is warranted to understanding the intergroup perception, attitude, and intended behavior. Our study is exploratory in nature and warrants further research to replicate our findings in order to inform social identity theory development.

We also note several recommendations for future intergroup interventions and university policies. Intervention studies should consider participants’ potentially different response to intergroup contact based on their personal background. Studies should also further examine to what extent participants’ resistance may influence study results when providing short-term interventions that aim to promote intergroup relationship between local and mainland residents in Hong Kong. Moreover, because the vast socio-political differences between mainland and Hong Kong have often led to misunderstanding and confusion, mainland students may not understand local students’ reasoning or had no opportunities to discuss or share their views (Ma & Holford, Citation2023). Future interventions may consider alternative activities, such as open discussion forums on current social issues, to increase mainland and local students’ understanding of each other’s perspectives. As suggested by our previous study, more interpersonal- and emotional-level contact should be facilitated in university life to enhance mutual understanding between the two groups (Li & Ng, Citation2024).

Conclusion

This study explored the intergroup perception, attitude, and behavior tendency between local and mainland university students in Hong Kong after the social unrest in 2019. Our results suggest significant differences in all the three domains of intergroup relationship between local and mainland students. We provided potential explanations for this phenomenon by reviewing the evolution of the Hongkongese identity, paralleled with the local residents’ everchanging perceptions toward mainland Chinese. In addition to the colonial history and economic development, media stereotyping effect may have played an essential role in forming the prejudiced attitudes toward mainland. Reviewing the economic, geopolitical, and sociocultural development, we conjecture the two groups of students’ different views reflect the unsettled mood of uneasiness among Hong Kong young people. We also speculate that some local university students are currently experiencing transitioning out of a superior identity when compared with their mainland counterparts. The sustained prejudiced attitudes and discriminative behaviors might be fueled by the conscious and unconscious motivations of maintaining a superior identity of the people in Hong Kong. We also found that local university students seem to bear resistance in changing their attitudes and intended behaviors toward their mainland counterparts as they gradually transition out of a superior identity

CP_Appendices_alttext clean.docx

Download MS Word (3 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All research data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hui Yun Li

Hui Yun Li is a PhD candidate in the Department of Social Work and Social Administration at The University of Hong Kong. Her research focuses on using art-based interventions to promote intergroup attitudes and relations among individuals from diverse social and cultural backgrounds. She is also an Australian Registered Music Therapist.

Siu-man Ng

Prof. Siu-man Ng has a dual professional background in mental health social work and Chinese medicine. His research theme is mental health, mental disorders and culture. His current research areas include (i) operationalization of the Chinese medicine stagnation syndrome as a psychological construct useful to all mental health practitioners; (ii) family expressed emotion of persons with schizophrenia and its impacts on the course of illness; (iii) critical re-examination of the conceptualization of mindfulness; and (iv) workplace well-being: a paradigm shift of focus from stress and burnout to meaning and engagement.

Amenda Man Wang

Ms. Amenda Man Wang, PhD student in the Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Registered Social Worker (RSW) in Hong Kong. Her research interests include 1) Development and Evaluation of Third-wave Interventions on Mental Health and Wellbeing 2) Gerontology, focusing on the communication between older adults and their caregivers.

Weiyi Xie

Dr. Weiyi Xie is a research assistant professor with over 10 years of extensive clinical counseling experience in the areas of parent-child dependent relationships, childhood adverse experiences, and family dynamics, with a particular interest in the developmental trajectories and adaptive states of children growing up in adversarial situations (e.g., low-income, rural areas, or traumatic experiences).

Shuang Lu

Shuang Lu, PhD, MSW, is an assistant professor in the School of Social Work, University of Central Florida. Her research focuses on the impact of migration and urbanization on youth development, community-based mental health interventions for disadvantaged children and families, and social service organizational capacity building.

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

- Branscombe, N., & Wann, D. (1994). Collective self-esteem consequences of outgroup derogation when a valued social identity is on trial. European Journal of Social Psychology, 24(6), 641–657. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420240603

- Brown, R. (2010). Prejudice: Its social psychology (2nd ed.). Whiley-Blackwell.

- Bryant, J. & Thompson, S. (Eds.) (2002). Fundamentals of media effects. McGraw-Hill.

- Carroll, J. M. (2005). Colonialism, nationalism, and bourgeois identity in colonial Hong Kong. Journal of Oriental Studies, 39(2), 146–164. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2350057

- Census and Statistics Department. (2019). Hong Kong annual digest of statistics (2019 Edition). Census and Statistics Department, The Hong Kong Government. https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/B1010003/att/B10100032019AN19B0100.pdf

- Chan, H. (1996). A study of Hong Kong residents’ perception toward visitors from China. [Unpublished final year project]. The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

- Chee, J. D. (2016). Pearson’s product-moment correlation: Sample analysis. University of Hawaii at Mānoa School of Nursing. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1856.2726

- Chen, N., Hsu, C., & Li, X. (. (2018). Feeling superior or deprived? Attitudes and underlying mentalities of residents toward Mainland Chinese tourists. Tourism Management (1982), 66, 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.11.007

- Cheng, Y., Cheung, A. C. K., & Yeun, T. W. W. (2010). Development of a regional education hub: The case of Hong Kong. International Journal of Educational Management, 25(5), 474–493. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513541111146378

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

- Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau. (2019). Rebuilding Sichuan – A Partnership of Hope when one suffers misfortune, aid comes from all sides. https://www.cmab.gov.hk/en/archives/recon_sichuan_overview.htm

- Duckitt, J., & Mphuthing, T. (1998). Group identification and intergroup attitudes: A longitudinal analysis in South Africa. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.80

- Eng, R. Y. (2017). The intractability of the Sino-Japanese Senkaku/Diaoyu territorial dispute: historical memory, people’s diplomacy and transnational activism, 1961-1978. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 15(22), 1–74. https://apjjf.org/-Robert-Y–Eng/5087/article.pdf

- Feng, V. (2013). Are mainland Chinese students ‘robbing Hong Kong locals of school places and jobs’? South China Morning Post. Jun 3. https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/1252540/are-mainland-chinese-students-robbing-hong-kong-locals

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Row, Peterson.

- Fielding, K. S., & Hornsey, M. J. (2016). A Social Identity Analysis of Climate Change and Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: Insights and Opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 171. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00121

- Gao, S., & Ng, S.-M. (2021). Reducing stigma among college students toward people with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial grounded on intergroup contact theory. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/schizbullopen/sgab008

- Grant, P., & Brown, R. (1995). From ethnocentrism to collective protest: Responses to relative deprivation and threats to social identity. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(3), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787042

- Guan, Y., Deng, H., & Bond, M. (2010). Examining Stereotype Content Model in a Chinese context: Inter-group structural relations and Mainland Chinese’s stereotypes toward Hong Kong Chinese. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(4), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.04.003

- Hamilton, G. (1999). Introduction. In Hamilton, G. G. (Ed), Cosmopolitan capitalist: Hong Kong and the Chinese diaspora at the end of the 20th century. University of Washington Press.

- Hewstone, M. (1990). The ‘ultimate attribution error’? A review of the literature on intergroup causal attribution. European Journal of Social Psychology, 20(4), 311–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420200404

- HKU POP. (2008). People’s ethnic identity. Public Opinion Program, University of Hong Kong (POP). https://www.hkupop.hku.hk/english/release/release628.html

- HKU POP. (2017). People’s ethnic identity. Public Opinion Program, University of Hong Kong (POP). https://www.hkupop.hku.hk/english/release/release1474.html

- Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., & White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(4), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787127

- Inkster, N. (2018). Chinese culture and soft power. Survival, 60(3), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2018.1470759

- Kwok, L. (2005). Anti-Japanese protests. Miss Kwok’s Secret Garden. April 19. http://www.louisakwok.blogspot.com

- Lai, A. (2012). Hong Kong newspaper ad rails against Chinese ‘invasion’. February 7, 2012. Cable News Network. https://edition.cnn.com/2012/02/01/world/asia/locust-mainlander-ad/index.html

- Lee, S-Y., & Chou, K-l (2018). Explaining attitudes towards immigrants from Mainland China in Hong Kong. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 27(3), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0117196818790572

- Lemmer, G., & Wagner, U. (2015). Can we really reduce ethnic prejudice outside the lab? A meta-analysis of direct and indirect contact interventions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(2), 152–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2079

- Leung, M. (1999). The study of Hong Kong residents’ perceptions toward tourists [Final year project]. The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

- Li, C. (2013). 陸16名高考狀元跨海念港大 (Lu shiliu ming gaokao zhuangyuan kuahai nian gangda, Sixteen Gaokao Top Scorers Cross the Harbour to Enter the University of Hong Kong), in: 旺報 (Wangbao, Want Daily), 17 July. https://www.chinatimes.com/cn/newspapers/20130712000965-260309?chdtv

- Li, M., & Bray, M. (2007). Cross-border flows of students for higher education: Push-pull factors and motivations of mainland Chinese students in Hong Kong and Macau. Higher Education, 53(6), 791–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-005-5423-3

- Li, H. Y., Ng, S., A. Wang, & S. Lu (2024, February 8-10). Enhancing Intergroup Relationship Between Local and Mainland College Students in Hong Kong – Randomized Controlled Trial of an Intensive One-Day Intervention Grounded in Intergroup Contact Theory [Poster Presentation]. SPSP Annual Convention 2024, San Diego, CA, United States. https://osf.io/nmcgu/

- Lui, T.-L. (1997). 呂大樂 唔該, 埋單! [Excuse me, check please!]. 香港: 閒人行有限公司 [Hong Kong]

- Ma, E. (2006). 市井國族主義: 重劃大陸與香港的文化版圖 [Everyday nationhood: Re-delineate the cultural map of Mainland and Hong Kong]. In C. H. Ng, K. W. Ma, , &, T-L. Lui (Ed.), 香港·文化·研究 [Hong Kong Style Cultural Studies]. Hong Kong University Press.

- Ma, A., & Holford, J. (2023). Mainland Chinese students in Hong Kong: Coping with the socio-political challenges of 2017 to 2020. Journal of Studies in International Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153231187142

- Ma, S. 馬淑君. (2013). “Xianggang Baodiao yundong licheng 香港保釣運動歷程,” Hong Kong In-Media 香港獨立媒體網, April 11, 2013. http://www.inmediahk.net/node/1018780

- Mingpao Daily News. (2008). 大地無情人有情, 我們都是汶川人[Nature is Heartless]. May 16. https://life.mingpao.com/eng/article?issue=20080516&nodeid=1507280141466

- Murtagh, N., Gatersleben, B., & Uzzell, D. (2012). Self-identity threat and resistance to change: Evidence from regular travel behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32(4), 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.05.008

- Ng, K. (2014). What is Occupy Central? 10 key facts about Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. September, 30, 2019. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/article/1604649/what-occupy-central-10-things-you-need-know

- Ng, C. H., Ma, E., & Lui, T. (2006). 香港·文化·研究 [Hong Kong style cultural studies]. Hong Kong University Press.

- Ng, S., Lu, S., Wang, A., Lo, K. C., Fok, H. K., Xie, W., & Li, H. Y. (2023). Enhancing intergroup relationship between local and mainland college students in Hong Kong – an intensive contact-based intervention. Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N.J.), 42(36), 32076–32096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04194-5

- Pallant, J. (2010). SPSS survival manual [electronic resource]: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS (4th ed.). Open University Press/McGraw-Hill.

- Ramasubramanian, S., & Murphy, C. (2014). Experimental studies of media stereotyping effects. In M. Webster, & J. Sell (Eds.), Laboratory experiments in the social sciences. (2nd ed., pp. 385–402). Academic Press.

- Shen, H., Luo, J., & Zhao, A. (2017). The sustainable tourism development in Hong Kong: An analysis of Hong Kong residents’ attitude toward mainland Chinese tourist. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 18(1), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2016.1167650

- Struch, N., & Schwartz, S. (1989). Intergroup aggression: Its predictors and distinctness from in-group bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(3), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.3.364

- Sum, L. (2019). Hong Kong extradition bill: thousands of protesters block city streets and prepare for worst as riot police gather nearby. June 12, 2019. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3014115/hong-kong-extradition-bill-thousands-protesters-start

- Sybing, R. (2023). Reverse coding: A proposed alternative methodology for identifying evidentiary warrants. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 26(3), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2022.2026133

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–37). Brooks/Cole.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 5, 7–24.

- Tam, Y. (2007). Who engineered the Anti-Japanese protests in 2005? Macalester International, 18(25), 281–299. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1352&context=macintl

- Terry, D. J., Hogg, M. A., & White, K. M. (1999). The theory of planned behavior: Self-identity, social identity and group norms. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 38 (Pt 3)(3), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466699164149

- Trading Economics. (2011). China GDP growth rate. Retrieved June 2, 2022, from http://www.tradingeconomics.com/Economics/GDP-Growth.aspx?Symbol=CNY

- University Grants Committee. (2021). Non-local student enrolment (headcount) of UGC-funded programmes by university, level of study, place of origin and mode of study. 2019/20 to 2020/21. https://cdcf.ugc.edu.hk/cdcf/searchStatSiteReport.action

- World Bank. (1993). The east Asian miracle: Economic and growth and public policy. Oxford University Press.

- Wu, N. (2000). Concept and tragedy – An analysis of the fate of the young children studying in the United States in the Late Qing dynasty. Shanghai People’s Publishing House.

- Xu, C. (2015). When the Hong Kong dream meets the anti-mainlandisation discourse: Mainland Chinese students in Hong Kong. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 44(3), 15–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810261504400302

- Yeung, S., & Leung, C. (2007). Perception and attitude of Hong Kong hotel guest-contact employees toward tourists from Mainland China. International Journal of Tourism Research, 9(6), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.611