Abstract

The organizations are facing a problem to keep their employees satisfied and retain them in this era. This study investigates the influence of mindfulness to increase employee job satisfaction and reduce turnover intentions via mediating effect of work–family balance. This research also examines the moderating effect of work–family conflict between the relationship of mindfulness and work–family balance. The real-life organizational empirical data were collected from 306 nurses working in public and private hospitals of Lahore, Pakistan. Structural equation modeling analysis revealed that all hypotheses were supported. Practical implications, limitations, and future directions are also discussed in this study.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Employees are facing the issue of work–family balance in organizations. If employees manage work–family balance, then they feel satisfied with their job; otherwise, they feel depression and anxiety, even intent to join the organizations having opportunities to manage their work–family balance. In Asian context, where the concept of joint family system is prevailed, their work–family balance is a big issue. Employees adopt different strategies to cope with this problem. This research aimed to investigate the influence of employees’ trait mindfulness on their work–family balance. Mindfulness is trait, quality, or state of a person to being conscious or aware of something. The 306 nurses working in public and private sector hospitals of Pakistan participated in the survey. The results showed that trait mindfulness of employees enhances their work–family balance, which result in increased job satisfaction and decreased turnover intentions. Furthermore, organizations need to help employees to revitalize their energies and mindfulness ability during stressful workdays.

1. Introduction

Organizations are facing a challenge to satisfy and retain the experienced employees in the dynamic and competitive environment. Work–family balance is a critical issue for employees on workplace nowadays. Many studies have discussed the predictors of job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and work–family balance (Egan, Yang, & Bartlett, Citation2004; Fazio, Gong, Sims, & Yurova, Citation2017; Janssen & Van Yperen, Citation2004; Judge, Heller, & Mount, Citation2002; Saari & Judge, Citation2004). Currently, researchers have found that mindfulness predicts the employees job satisfaction and turnover intentions (Dane & Brummel, Citation2014; Hulsheger, Alberts, Feinholdt, & Lang, Citation2013; Wongtongkam, Krivokapic-Skoko, Duncan, & Bellio, Citation2017). Furthermore, Mesmer-Magnus, Manapragada, Viswesvaran, and Allen (Citation2017) explained that trait mindfulness provides both personal and professional advantages to the employees on workplace. For the personal advantage, trait mindfulness is linked positively to mental health, confidence, life satisfaction, and emotional regulation, while negatively correlated with negative emotions, anxiety, depression, and perceived life stress. Additionally, professional advantages include job performance, job satisfaction, and interpersonal relations. Mindfulness is also helpful in reducing work withdrawal and burnout among employees. The mindfulness has been defined as “a psychological state in which one focuses attention on events occurring in the present moment” (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003). Moreover, mindfulness means the quality or state of being conscious or aware of something. Simply, an employee is a mindful person, when he/she is present and understand every event occurring in front of him/her. This concept is derived from the Buddhism (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, Citation2007). Buddhist tried to enhance their awareness of the present moment by mindfulness meditation (Nyanaponika, Citation1949). Despite its origin, mindfulness has attracted the attention of different research scholars in this era as well. Research studies also reported that mindfulness is a different construct from other similar concepts like openness to experience and emotional intelligence (Dane, Citation2011; Weinstein, Brown, & Ryan, Citation2009).

Mindfulness expediency has been tested in different disciplines like social psychology, neuroscience, and medicine, etc. (Dane & Brummel, Citation2014). Mindfulness has been mostly tested on clinical samples as a cure for different psychological problems and behavioral disorders such as depression, chronic pain, or eating disorder (Hulsheger et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, many physicists have also used mindfulness to enhance physical well-being (Dane & Brummel, Citation2014). Due to these benefits, mindfulness has gained much attention even in recent studies (Glomb, Duffy, Bono, & Yang, Citation2011).

Globally, nursing is a profession for high-quality patient care. Mindfulness interventions increase job satisfaction in nurses (Mrayyan, Citation2007) and decreased absenteeism and retention (Davey, Cummings, Newburn, & Lo, Citation2009; Ritter, Citation2011). In nursing profession, job satisfaction is an important outcome which reduces the turnover rate and burnout (AbuAlRub, Omari, & Al-Zaru, Citation2009; Abushaikha & Saca—Hazboun, Citation2009).

Most of the researchers used meditation practices to enhance the mindfulness, and these meditation practices are known as mindfulness treatment (Jha, Morrison, Parker, & Stanley, Citation2017; Creswell & Lindsay, Citation2014; Hugh-Jones, Rose, Koutsopoulou, & Simms-Ellis, Citation2018; Lindsay & Creswell, Citation2017). Recently, many scholars have conceptualized mindfulness as psychological state which individuals experience in different situations even without mindfulness treatment. Studies have suggested that mindfulness varies from person to person (Allen & Kiburz, Citation2012; Brown & Ryan, Citation2003), which means that one can be more mindful than the other (Giluk, Citation2009). Therefore, level of mindfulness may be assessed as a psychological state or trait of individuals (Kabat-Zinn, Citation2005). Allen and Kiburz (Citation2012) argued that individual dispositional difference in mindfulness relates to different psychological diseases like psychological distress, anxiety, rumination, etc. (Carmody & Baer, Citation2008). The natural mindfulness which is not developed through any meditation practice is useful for behavior regulation and psychological health (Bowlin & Baer, Citation2012). The implementation of mindfulness-based practices improves employees’ mental health (Gregoire & Lachance, Citation2015; Virgili, Citation2015), work–life balance (Allen & Kiburz, Citation2012), work satisfaction (Hulsheger et al., Citation2013), work performance (Reb, Narayanan, & Ho, Citation2015), client satisfaction (Gregoire & Lachance, Citation2015), and decrease turnover intentions (Dane & Brummel, Citation2014; Reb et al., Citation2015).

The organizational scientists are investigating the benefits of mindfulness on the workplace. The studies have discussed mindfulness relationship with different variables like task performance, job satisfaction, and leadership (Dane, Citation2011; Glomb et al., Citation2011; Hulsheger et al., Citation2013; Reb, Narayanan, & Chaturvedi, Citation2014). Furthermore, researchers have discussed these relationships theoretically, and a few studies tried to investigate this phenomenon empirically (Reb et al., Citation2014; Wongtongkam et al., Citation2017). Further studies are needed to increase the understanding of researchers and practitioners about the mechanism through which mindfulness influences the employee’s well-being, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions in the workplace. Some of the researchers suggested some phenomena like surface acting as its mechanisms are still to be explored (Hulsheger et al., Citation2013).

This study aims to explore the underlying mechanism of association among trait mindfulness, turnover intentions, and job satisfaction. An employee usually has two major roles in his life: work life and family life. Research supported that trait mindfulness helps in enhancing personal and professional outcomes (Mesmer-Magnus et al., Citation2017). Trait mindfulness can improve the ability of a person to balance these two roles (work–family balance), because of his/her characteristics to remain mentally involved in workplace activities without thinking about other things. Consequently, the work–family balance will increase his/her job satisfaction and decrease turnover intentions. So, work–family balance can mediate the influence of trait mindfulness on job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Furthermore, if the requirements of the job and family have a conflict with each other (work–family conflict), then employees with mindfulness trait might be able to maintain this balance. Moreover, the presence of work–family conflict can weaken the association between trait mindfulness and work–family balance.

To keep the employee satisfied and to retain the competent employees are the primary issues faced by the organizations nowadays. Mindfulness is a good predictor of job satisfaction and keeps the turnover intentions low. This research focuses that how mindfulness is helpful for an organization to retain and satisfy its employees. The mechanism of salutary impacts of trait mindfulness on employee outcome at the workplace is studied in the research. This research focuses on only two employee outcomes at the workplace: job satisfaction and turnover intentions. This study explores the mediating effect of work–family balance in the relationship of trait mindfulness with job satisfaction and turnover intentions and the moderating influence of work–family conflict between the relationship of trait mindfulness and work–family balance. Hence, this research objectives are (1) to explore the relationship of trait mindfulness with job satisfaction and employee turnover intentions, (2) to examine the mediating role of work–family balance between trait mindfulness and the two employee’s outcomes, and (3) to observe the moderating role of work–family conflicts in the relationship of trait mindfulness and work–family balance.

2. Literature review

2.1. Mindfulness and job outcomes (job satisfaction and turnover intention)

Glomb et al. (Citation2011) theorized mindfulness as a “state of consciousness characterized by receptive attention to and awareness of present events and experiences without evaluation and judgment.” It has three essential characteristics. First, it is a psychological state which means that every person possesses it (Harvey, Citation2000). As a state, it is not something that one person has, and another does not (Dane, Citation2011). As argued by Kabat-Zinn (Citation2005), it is the inherent capacity of every human to achieve this state of mindfulness. But its level is different in different people as argued by Walach, Buchheld, Buttenmüller, Kleinknecht, and Schmidt (Citation2006), some people are consciousness more often in comparison with other people, so, it is considering an attribute. Many researchers have treated mindfulness as personality traits (Allen & Kiburz, Citation2012; Brown & Ryan, Citation2003).

Second, it is the state of conscientiousness, to be present in the current moment. As explained by Hulsheger et al. (Citation2013), mindfulness is presently oriented consciousness state, and it is also argued by Herndon (Citation2008) that for being mindful, a person should focus on “here and now.” A person with mindfulness should have a focus on presenting without thinking about the future or wandering in the past.

Third, it includes receptive attention and awareness without judgment. According to Brown et al. (Citation2007), mindfulness involves paying attention to the current situation without attributing any judgment to it. Similarly, Hulsheger et al. (Citation2013) argue that in the state of mindfulness, individual observes the current situation without evaluating or reacting upon it. So, it means that while in the state of mindfulness, a person does not respond to the event abruptly because this state restrains the person to attribute any meaning to the happening event. It includes receptive attention of both inner (emotions, thoughts, and feelings) and external events (Hulsheger et al., Citation2013).

This research used mindfulness at trait level (trait mindfulness). Many researchers have presented the evidence that it is not compulsory that only the person, who has gone through meditation practice, possess mindfulness. Mindfulness is the intrinsic people capacity (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003), it varies from person to person and moment to moment (Robbins & Judge, Citation2012), and this variation is linked to environmental situations and genes (Davidson, Citation2010). Trait mindfulness is linked with salutary effects in different fields (Bowlin & Baer, Citation2012; Dane, Citation2011; Glomb et al., Citation2011).

It is investigated that individual mentally present at work with full concentration will be satisfied with the job (Hulsheger et al., Citation2013). Individual variances show a significant role in job satisfaction with the mediation effect of job engagement; mindfulness is positively linked to job satisfaction (Hofmans, De Gieter, & Pepermans, Citation2013; Zivnuska, Kacmar, Ferguson, & Carlson, Citation2016). Individuals are having the quality of mindfulness, focus on the job, and get the benefit of job satisfaction (Mesmer-Magnus et al., Citation2017). Another recent study explains that individual with careful attention shows that they were more focused at work and were more satisfied with their jobs (Wongtongkam et al., Citation2017). Based on the literature, it is assumed that trait mindfulness has a positive impact on job satisfaction.

Weinstein et al. (Citation2009) describe in their research that mindfulness helps individuals to handle stress proactively and adapt themselves accordingly. Atkins and Parker (Citation2012) argue that mindfulness accelerates self-regulation. Furthermore, this enables individuals to react to stressed events with great calmness and deep cogitation (Carlson, Citation2013). In a dynamic workplace, mindfulness helps people to cope with challenging tasks and hence negatively associated with the turnover intention (Dane & Brummel, Citation2014). Based on the literature, this study proposes that mindfulness is negatively linked with turnover intention.

Hypothesis 1(a):

Trait mindfulness has the positive impact on job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 1(b):

Trait mindfulness has the negative impact on turnover intention.

2.2. Mediating role of work–family balance

Existing research investigated that mindfulness has a positive effect on work–family balance. Existing literature reveals that different authors define it differently. Despite these various conceptualizations in this research, work–family balance is taken as complete appraisal regarding person’s efficiency and satisfaction with work and family life. So, the work–family balance is referred to the person’s skill to keep a balance between his role at work and role in the household (Allen & Kiburz, Citation2012). Work–family balance is different from other related constructs in work–family literature like work–family conflict and work–family enhancement. The work–family balance was considered the absence of work–family conflict, but it is not true because if the lack of conflict is balanced, then we do not need two concepts (Carlson, Grzywacz, & Zivnuska, Citation2009). Other concepts are the relationship between work and family role requirements, but the balance is not any relationship or connecting system, it is considered as the person’s ability to balance the need for both characters (Carlson et al., Citation2009). Now, it is agreed that stability, conflict, and enrichment are three different concepts (Allen & Kiburz, Citation2012; Carlson et al., Citation2009; Jain & Nair, Citation2013).

Due to these confusions, not many researchers have attempted to explore predictors and consequences of work–family balance. But some predictors and outcomes are proposed like: long work hours are negatively linked to work–life balance. Job characteristics are also one of the predictors of work–life balance. Job complexity and control over time have a positive impact on work–life balance (Valcour, Citation2007). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, life satisfaction, and family functioning are presented as some of the outcomes of work–family balance (Carlson et al., Citation2009).

In this research, the hypotheses are established on the bases of role balance theory. According to this theory, trait mindfulness has a positive effect on work–family balance. Role balance is connected with one’s overall role while performing the individual role. It requires that regular role performed by the partner should have the behavior of attentiveness (Marks & MacDermid, Citation1996). This rehearsal of evenhanded vigilance sometimes stated as mindfulness. In light of this approach, if a person approaches the role at hand with alertness and attentiveness, then he/she can better balance the role. Attentiveness and sharpness to the present moment are the essential elements of trait mindfulness. Mindfulness enhances the self-determined behavior (Glomb et al., Citation2011) and prevents the automatic response, which means that a person with mindful ability can pay full attention to the present role without automatically thinking about another role. So, if a person has high trait mindfulness, he will be better at focusing on the only current role at hand without thinking the other role which in return will increase its ability to create the balance between roles which is a work–family balance. Based on above literature, it can be hypothesized that

Hypothesis 2:

Trait mindfulness has the positive impact on work–family balance.

There are six behavioral outcomes of an employee in the workplace which are studied in the field of organizational behavior (Robins, Keng, Ekblad, & Brantley, Citation2012). Three of them are positive outcomes (job satisfaction, job performance, and organizational citizenship) and three of them are negative results (absenteeism, turnover intentions, and deviance). From positive results, job satisfaction is taken because it is the most famous predictor of all other behaviors and from adverse consequences because of the organization, it is a very crucial issue to retain their employees. Job satisfaction and absenteeism are presented as the results of the work–family balance. These outcomes are tested before with different conceptualizations of work–family balance like Allen, Herst, Bruck, and Sutton (Citation2000), considered work–family balance as the opposite of work–family conflict. Moreover, they argued that if a person has less work–family conflict, it will have fewer turnover intentions. So, there is not much investigation on work–family balance given separate concept in the literature of work–family (Carlson et al., Citation2009).

So, we proposed that if the individual can balance both roles, then he will be more satisfied with his job and will have fewer intentions to turn over. Maintaining a balance between work–life was supported as one of the best practices that after adaptation reduced workplace stresses and increased job satisfaction (Aamir, Hamid, Haider, & Akhtar, Citation2016). The more satisfied employees are with their job, the lesser the turnover intentions. Based on a review of the literature, the hypothesis can be developed showing that work–family balance has a positive impact on the job satisfaction and negative impact on turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 3(a):

Work–family balance has a positive influence on job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3(b):

Work–family balance has a negative influence on turnover intentions.

Trait mindfulness enhances a person’s ability to maintain reasonable relation b/w family role and work which is known as work–family balance (Johnson, Kiburz, Dumani, Cho, & Allen, Citation2011). Work–family balance reduces turnover intentions and enhances the job satisfaction (Carlson et al., Citation2009). There is a mediation effect of work–family balance on work–family conflict and job satisfaction (Pattusamy & Jacob, Citation2017). So, collectively, it can be said that trait mindfulness being a positive attribute enhances the work–family balance which further improves the job satisfaction and decreases turnover intentions. So, work–family balance is a guiding mechanism for having trait mindfulness with its salutary effects at the workplace. Based on the literature, hypotheses are formed to depict that work–family balance mediates the relationships between trait mindfulness, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 4(a):

Work–family balance mediates the association between trait mindfulness and job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 4(b):

Work–family balance mediates the association between trait mindfulness and turnover intentions.

2.3. Moderating role of work–family conflict

Existing literature considered work–family conflict and the work–family balance as interrelated constructs. Work–family balance is mostly investigated from conflict viewpoint (Greenhaus & Beutell, Citation1985). But Carlson et al. (Citation2009) proved that work–family conflict is different from work–family balance. Work–family balance is a person’s ability to keep balance in work and family roles, but the work–family conflict is the extent to which one role negatively affects the other (Carlson et al., Citation2009). This conceptualization of work–family conflict was taken from Greenhaus and Beutell (Citation1985), which defined work–family conflict as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures of the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect.” Then, further Frone, Russell, and Cooper (Citation1992) argued that work–family conflict is a bi-directional concept. According to his definition of WFC given by Greenhaus and Beutell (Citation1985) unambiguously depicts the two directions of the idea. But only one path (work to family) of the concept is studied which limits the limitation of the notion. So, the work–family conflict has dual directions work to family conflict and family to work conflict. When work requirements are inconsistent with a family requirement or work interfere with family, it is perceived work to family conflict. Carlson et al. (Citation2009) explained that “when a lousy day at work spills over into the family and results in snappy parent-child interactions,” it is considered as work to family conflict. Another direction of the concept is family to work conflict which means that requirement of family role conflicts with the work requirements or family interferes with work (Frone et al., Citation1992).

This study proposes that work–family conflict moderates the association between trait mindfulness and work–family balance. If a person has low work–family conflict which means that a person’s both roles don’t interfere with each other, then he will quickly remain attentive at the present position, so he will be able to keep balance. But if a person facing the high work–family conflict which means that the individual’s both roles interfere with each other, then he or she will not be able to remain attentive or aware at present role, so it will be difficult for him to keep balance in both roles. As said by Carlson et al. (Citation2009), role conflict affects the person’s ability to maintain a balance between roles. In a nutshell, the high work–family conflict will lessen the association between trait mindfulness and work–family balance, and low work–family conflict will strengthen the association between trait mindfulness and work–family balance. Finally, this study hypothesizes that work–family conflict moderates the linkage between trait mindfulness and work–family balance.

Hypothesis 5: Work–family conflict moderates the linkage between trait mindfulness and work–family balance. Such that if the work–family conflict is high, it will weaken the linkage between trait mindfulness and work–family balance and vice versa. A conceptual framework is developed based on comprehensive literature review, which is depicted in Figure .

3. Methodology

3.1. Date collection procedure and sample

The real-life organizational data were collected from nurses working in different public-sector hospitals of Lahore, Pakistan. The population for this study was employees of interactive service jobs because mindfulness is very significant for service providing employees as suggested by Hulsheger et al. (Citation2013). Mahon, Mee, Brett, and Dowling (Citation2017) also conducted a study regarding trait mindfulness and job stress in the nursing profession. To stay focused and attentive is an integral part of the service industry because they directly face the customers. Trait mindfulness, work–family balance, and work–family conflict can best be studied in such an environment. It is a quantitative cross-sectional research study; its unit of analysis was individual and its data collected through self-reported questionnaires. Through a simple random sampling technique, the sample was taken from nursing profession from health sector where service provision is an integral part of their job. Nurses have to work in most dynamic and challenging environment because they have to focus on more than one task at a time (Byrne, Keuter, Voell, & Larson, Citation2000). This sampling technique was used to avoid prejudice and other undesirable effects from the respondents.

The survey methodology was used to distribute 500 questionnaires among nurses. The 306 questionnaires were received back from those surveyed; the response rate was 61.2%. The recommended item–respondent ratio applied for the present study was 1:5 (45:225) (Bentler & Chou, Citation1987); the 306 responses exceeded the required level of respondents. The questionnaires were translated from English to Urdu to make it understandable for respondents (Brislin, Citation1980).

The age of most of the respondents is ranging between 20 and 25 years. The mixed results have been got in the education, 47.4% respondents have an intermediate qualification, 32% have a bachelor qualification, and 15.7% respondents have a master qualification. Twenty-eight percent respondents have 1–5 years experience, 39.2% have 5–10 years, 18.3% have 10–15 years, 11.7% have 15–20 years, and 2.8% have 20–25 years experience. The data were collected from service providing industry.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Trait mindfulness

It is measured by 15-item questionnaire (Mindfulness Attention and Awareness Scale) developed by Brown and Ryan (Citation2003). Sample items are “I could be experiencing some emotion and not be conscious of it until sometime later” and “I break or spill things because of carelessness, not paying attention, or thinking of something else.” These items were responded on the 5-point scale ranging from 1 = almost always to 5 = almost never.

3.2.2. Work–family balance

It is measured by 6-item questionnaire created by Carlson et al. (Citation2009). Sample items are “I can negotiate and accomplish what is expected of me at work and in my family.” And “I do a good job of meeting the role expectations of critical people in my work and family life.” A Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree used to measure these items.

3.2.3. Work–family conflict

It is measured by 18-item questionnaire created by Carlson, Kacmar, and Williams (Citation2000). These nine items were used to measure work to family, and other nine items were used to measure family to work conflict. Sample items are “My work keeps me from my family activities more than I would like” and “The time I must devote to my job keeps me from participating equally in household responsibilities and activities.” A Likert scale range starting from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree used to measure these items.

3.2.4. Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction is measured by two items which are developed by work of Hackman and Oldham (Citation1975) and designed by Hofmans et al. (Citation2013). Items are “Generally speaking, I am satisfied with my job” and “I am generally satisfied with the kind of work I do in my job.” A 5-point scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree used to measure these items.

3.2.5. Turnover intention

It is measured by 4-item scale created by Kelloway, Gottlieb, and Barham (Citation1999). Sample items are “I am thinking about leaving this organization” and “I am planning to look for a new job.” A Likert scale range starting from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree used to measure these items.

4. Analysis strategy

The structural model was tested through structural equation modeling using SPSS Version 22 and AMOS. The measurement model was evaluated through assessing the reliability (through Cronbach alpha), convergent validity (through average variance extracted), and discriminant validity (through Fornell–Lacker Criterion) have been calculated. Confirmatory factor analysis, mediation analysis, and moderation analysis have been performed to get results. Structural equation model has been used to test the hypotheses.

4.1. Common method variance

We used difference scales between independent variable and dependent variable as a procedural remedy to reduce the common method variance. Second, Harman’s single factor test was used (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003), as statistical remedy to assess the common method bias. In this study, single factor showed only 29% of the total variance, which confirmed that there is no issue regarding common method variance. Mattila and Enz (Citation2002) described in their research study that method bias would issue when one factor explains more than 50% of the variance in the items.

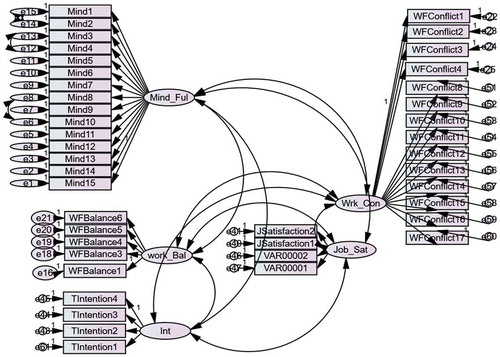

4.2. Confirmatory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis is a beneficial tool for measuring the validity of a construct. In the words of Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988), measurement model is a pre-requisite of confirmatory factor analysis to test structural model. Several CFAs are done until the model fit of the measurement model is achieved. In this regard, one item of construct “work–family balance” and four items of construct “work–family conflict” are deleted, because of issues in factor loadings and collinearity. The Figure shows the results of confirmatory factor anaylsis.

4.3. Measurement model

The measurement model has been evaluated through fit indices. In this research, study results showed good fit values (χ2 = 1,758.871, df = 806, χ2/df = 2.182, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.90, NNFI = 0.90) suitable to the suggested standard values (χ2/df < 3, RMSEA < 0.08, CFI > 0.95, NNFI > 0.95) (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988; Browne, Cudeck, Bollen, & Long, Citation1993; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). As suggested by Cheung and Rensvold (Citation2002), value equal to 0.90 is also acceptable for CFI and NNFI.

The parameter estimates have been used to measure the convergent validity of the constructs in the study. The estimates depict large values from (>0.66) and significant t-values (8–14) (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988), having AVE > 0.5 and having composite reliability >0.7 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). So, these results in Table show that convergent validity of all constructs is satisfied. As per Zait and Bertea (Citation2011), for discriminant validity, the square root of AVE should be greater than squared correlations of two constructs, so in Table , results show that the square root of AVE is greater from squared correlations of two construct. So, discriminant validity also satisfied. This table indicates that trait mindfulness, work–family balance, work–family conflict, job satisfaction, and turnover intention have mean values 3.8937, 3.7569, 2.6340, 3.9379 and 2.3325, respectively.

Table 1. Construct reliability and convergent validity of constructs

Table 2. Results of discriminant validity

4.4. Hypotheses testing

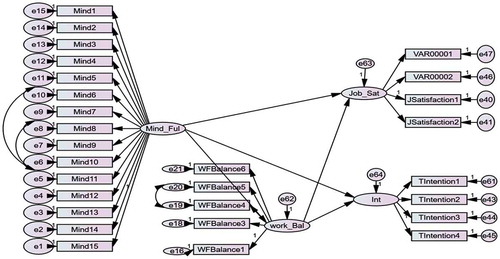

For testing of hypothesis, the structural model was developed. The result indicates that model has qualified the criteria of good fit as (χ2 = 1,005.64, df = 344, χ2/df = 2.92, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.90, NNFI = 0.90).

4.5. Structural model

The analysis reveals in Table that test statistics have supported all hypotheses. H1(a) posits that trait mindfulness has the positive impact on job satisfaction and it is supported with (β = 0.074, p < 0.05). H1(b) asserts that trait mindfulness has the negative impact on turnover intention and it is supported with (β = −0.321, p < 0.05). H2 posits that trait mindfulness has the positive impact on work–family balance, and it is supported by (β = 0.230, p < 0.05). H3(a) posits that work–family balance has the positive effect on job satisfaction, and it is supported with (β = 0.341, p < 0.001). H3(b) asserts that work–family balance has the negative impact on turnover intention and it is supported with (β = −0.548, p < 0.001). The Figure presents the results of structural model.

Table 3. Results of structural model

Table 4. Direct and indirect path coefficients of mediation model 1

Table 5. Direct and indirect path coefficients of mediation model 2

Two structural models were used for checking of mediation. The first structural model was used for testing of intervention with a direct path for trait mindfulness and job satisfaction and turnover intention, where the second structural model was used for checking of mediation with an indirect path via work–family balance as suggested Iacobucci, Saldanha, and Deng (Citation2007).

4.6. Role of work–family balance as mediator

4.6.1. Mediation model 1

The measurement model has been evaluated through fit indices. In this research, study results showed good fit values (χ2 = 1,056, df = 422, χ2/df = 2.503, RMSEA = 0.055, NNFI = 0.90, CFI = 0.90).

Table indicates that there is no significant relationship between trait mindfulness and job satisfaction with path coefficient which is used for direct effect, whereas trait mindfulness has a substantial impact on job satisfaction when the effect is indirect through work–family balance. To sum up, it is evident that there is a full mediation of work–family balance between trait mindfulness and job satisfaction as supported by hypothesis H4(a).

4.6.2. Mediation model 2

The measurement model has been evaluated through fit indices. In this research, study results showed good fit values (χ2 = 1,067, df = 366, χ2/df = 2.916, RMSEA = 0.056, NNFI = 0.90, CFI = 0.90).

Table depicts that there is a significant association between trait mindfulness and turnover intention as suggested by the path coefficient for direct effect. The results show that mindfulness has an impact on turnover intention. Further, the path coefficient for indirect work–family balance is also significant. Therefore, work–family balance mediates the association between trait mindfulness and turnover intention as supported by the hypothesis H4(b). To sum up, it is evident that there is a partial mediation of work–family balance between trait mindfulness and turnover intention.

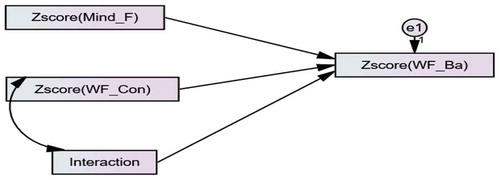

4.6.3. Moderation analysis

In this study, Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) method has been used to check the moderating impact of work–family conflict. The measurement model was evaluated through fit indices. In this research, study results showed good fit values (χ2 = 5.446, df = 2, χ2/df = 2.72, RMSEA = 0.07, NNFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.93).

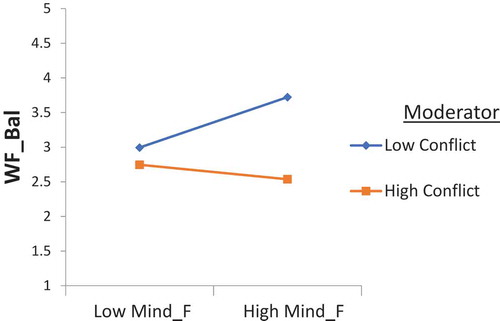

H2 posits that work–family conflict moderates the association between trait mindfulness and work–family balance. Such that if the work–family conflict is high, it will weaken the relationship between trait mindfulness and work–family balance and vice versa, and it is supported. Table shows that the standardized regression coefficients from interaction term are −0.234 which is significant with (t = −5.430, p < 0.001). The Figure presents the results of moderation analysis.

Table 6. Results of moderation analysis

The Figure indicates that the moderator(s) (low conflict, high conflict) impacts on the linkage between trait mindfulness and work–family balance. When there is high conflict, then low mindfulness and work–family balance have an inverse relationship, whereas when there is less conflict, there is a direct linkage between work–family balance and high mindfulness, which further support H2.

5. Discussion

In spite of flowing awareness in mindfulness across different areas of research, organizational researchers have given less contemplation to the employee’s level mindfulness and its outcomes at work environment. The existing literature on mindfulness shows that exercise regarding mindfulness on workplace provides beneficial results.

This study investigated an widely researched concept in the workplace, and the result indicates that psychological presence in the workplace with full concentration is significantly related to employee job satisfaction. These results are consistent with the study conducted by Hulsheger et al. (Citation2013) that trait mindfulness is positively associated with job satisfaction. Mindfulness approach added to relaxed feelings and calmness during one of an intervention study and enhanced in job satisfaction (Wongtongkam et al., Citation2017).

The results also shown that trait mindfulness is negatively associated with job turnover intentions and results are in line with the study (Reb, Narayanan, Chaturvedi, & Ekkirala, Citation2017). Reb et al. (Citation2017), in one of his mediation studies, investigated that mindfulness reduces the emotional exhaustion and, in this way, helps to reduce turnover intentions. This study also supported that mindfulness is significantly related to work–family balance. These results are in accordance with research study conducted with working parents who linked mindfulness with greater work–family balance (Allen & Kiburz, Citation2012); these results provide bases for our debate enriched self-regulation is the outcome of trait mindfulness may empower employees to practice satisfaction and efficiency in each character.

The hypothesis that association of work–family balance is negative with turnover intentions is also supported. Further, a study recommended that work to family spillover is positively associated with turnover intentions while family to work is negatively related to turnover intentions (Watanabe & Falci, Citation2016).

The last hypothesis that work–family conflict moderates the association between mindfulness and work–family balance is also supported. In case of low work–family conflict, trait mindfulness enhances work–family balance. This study also hypothesized that work–family balance is positively linked with job satisfaction and negatively with turnover intentions. Work–family balance increases job satisfaction, and results are in line with Aleksic et al. (Citation2017), which investigated the effect of work–family balance on job satisfaction and found positive outcomes.

This study examined the impact of trait mindfulness on work–family balance and employment consequences as well as mediating role of work–family balance and moderating role of work–family conflict. Before this study, work–family balance and work–family conflict were being considered two edges of the same variable, but moderation support of work–family conflict showed that these two are different variables and started a discussion differently. The researcher should investigate this relationship in future studies to support or refute this investigation. So, this study has a theoretical contribution in expanding the knowledge of work–family conflict and work–family balance.

6. Study implications

6.1. Theoretical implications

One important contribution made by the present study is the examination of moderated mediation model of relationships between trait mindfulness, work–family balance, and two potential outcomes (job satisfaction and turnover intentions), moderated by work–family conflict. Overall, our findings partially support the moderated mediation model (Figure ) tested in this research. Although past research has suggested that employee trait mindfulness plays a critical role in determining employee turnover intentions and job satisfaction (Dane & Brummel, Citation2014; Hulsheger et al., Citation2013; Wongtongkam et al., Citation2017), none of these previous studies examined the moderated mediation relationships between trait mindfulness and criterion variables. Trait mindfulness was related to work–family balance, which in turn was associated with reduced turnover intentions and higher level of job satisfaction for specific group of respondents.

These results are consistent with role balance theory that describes that individuals demonstrate equally positive commitments to different life roles; that is, they should hold a balanced orientation to multiple roles (Marks & MacDermid, Citation1996). So, this study validates and contributes the role balance theory by checking the mediating role of work–family balance between relationships of trait mindfulness with job satisfaction and turnover intentions and moderating role of work–family conflict. In light of this approach, if a person approaches the role at hand with alertness and attentiveness, then he/she can better balance the role and he will be better at focusing on the only current role at hand without thinking the other role which in return will increase its ability to create the balance between roles which is a work–family balance.

6.2. Practical implications

Mindfulness is a beneficial concept for organizations. This study has some practical implications. First, executive leadership should add some recruitment tests to check the applicant’s ability of mindfulness. Second, after hiring employees should be given the training to improve their concentration on work and enhance their capacity for mindfulness. To develop mindfulness in the organizations, HR practitioners should consider integrating mindfulness consideration as an employee development program that results in augmented empathy for others (Tischler, Biberman, & McKeage, Citation2002). Third, organizations should introduce some entertainment programs at the workplace to maintain the employee’s mindfulness ability at work. Mindfulness is the ability not related to any religion or faith, so people from all ethnic background, religion, or culture can practice it at the workplace to get its benefits (McGhee & Grant, Citation2015). Universities must also introduce courses in mindfulness to increase productivity at all levels. McGhee and Grant (Citation2015) advised that there must be room in organizations which would help employees to revitalize their energies and mindfulness ability during stressful workdays. The training of trait mindfulness will reduce the stress in employees (Jha et al., Citation2017; Creswell & Lindsay, Citation2014; Hugh-Jones et al., Citation2018; Lindsay & Creswell, Citation2017).

7. Limitations and future directions

Like all other studies, this study also used the self-reported questionnaire, cross-sectional study design, and data from one sector. So, generatability issue pertains to this study. Future research must be conducted in different industries. Mindfulness is a construct without massive empirical literature, so the content validity of this construct must be empirically tested to make it more valuable, so future research must concentrate on it. Future research must investigate the extent to which the linkage between mindfulness and professional outcomes like job satisfaction and turnout intentions are moderated by context or few other factors (Dane, Citation2011). Future research can investigate the impact of trait mindfulness on multitasking jobs also.

8. Conclusion

Research on mindfulness is widespread across several disciplines, but regarding workplace mindfulness, there is need to be studied. This study empirically investigated the effect of mindfulness on job satisfaction and turnover intentions in the dynamic workplace setting. This study added to the theoretical and empirical literature in mindfulness by mediating the role of work–family balance and via moderation of work–family conflict. The hypotheses of the study are confirmed. Trait mindfulness has a positive impact on job satisfaction, which is supported with empirically. Trait mindfulness has a negative impact on turnover intention also supported in this empirical study. Work–family balance mediates the relationship between trait mindfulness and job satisfaction and turnover intention; these hypotheses are accepted in this research. Furthermore, work–family conflict moderates the relationship of trait mindfulness and work–family balance, which is supported in this study. So, this study will help the organizations to implement the findings of this research study. The results of this study strongly recommend that organizations should provide training regarding mindfulness meditation, which will reduce the employee turnover intentions and increase job satisfaction through work–family balance and mindfulness training.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Basharat Raza

Basharat Raza is PhD student at National College of Business Administration and Economics, Lahore, Pakistan. Faculty Member at NCBA & E DHA Campus Lahore. His research interests are in HRM and organizational behavior. E-mail: [email protected].

Muhammad Ali

Dr. Muhammad Ali is an assistant professor in Department of Management Sciences, Lahore Garrison University, Lahore, Pakistan. His research interests are in organizational development, HRD, and organizational behavior. E-mail: [email protected].

Khalida Naseem

Khalida Naseem is PhD student at National College of Business Administration and Economics, Lahore, Pakistan. Her research interests are in organizational psychology. E-mail: [email protected].

Abdul Moeed

Abdul Moeed is PhD student at National College of Business Administration and Economics, Lahore, Pakistan. His research interests are in behavioral finance. E-mail: [email protected].

Jamil Ahmed

Jamil Ahmed is PhD student at National College of Business Administration and Economics, Lahore, Pakistan. His research interests are in HRM and behavioral finance. E-mail: [email protected].

Muhammad Hamid

Muhammad Hamid is lecturer at Department of Statistics and computer science, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan. His research interests are in project management. E-mail: [email protected].

References

- Aamir, A., Hamid, A. B. A., Haider, M., & Akhtar, C. S. (2016). Work-life balance, job satisfaction and nurses’ retention: The moderating role of work volition. International Journal of Business Excellence, 10(4), 488–501. doi:10.1504/IJBEX.2016.079257

- AbuAlRub, R. F., Omari, F. H., & Al-Zaru, I. M. (2009). Support, satisfaction and retention among Jordanian nurses in private and public hospitals. International Nursing Review, 56(3), 326–332. doi:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2009.00718.x

- Abushaikha, L., & Saca--Hazboun, H. (2009). Job satisfaction and burnout among Palestinian nurses. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 15(1), 190–197.

- Aleksic, D., Aleksc, D., Mihelic, K. K., Mihelic, K. K., Cerne, M., Cerne, M., … Skerlavaj, M. (2017). Interactive effects of perceived time pressure, satisfaction with work-family balance (SWFB), and leader-member exchange (LMX) on creativity. Personnel Review, 46(3), 662–679. doi:10.1108/PR-04-2015-0085

- Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 278–308.

- Allen, T. D., & Kiburz, K. M. (2012). Trait mindfulness and work-family balance among working parents: The mediating effects of vitality and sleep quality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 372–379. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.09.002

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Atkins, P. W., & Parker, S. K. (2012). Understanding individual compassion in organizations: The role of appraisals and psychological flexibility. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 524–546. doi:10.5465/amr.2010.0490

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. doi:10.1007/BF02723327

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods and Research, 16(1), 78–117. doi:10.1177/0049124187016001004

- Bowlin, S. L., & Baer, R. A. (2012). Relationships between mindfulness, self-control, and psychological functioning. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 411–415. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.050

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 2(2), 349–444.

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

- Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. doi:10.1080/10478400701598298

- Browne, M. W., Cudeck, R., Bollen, K. A., & Long, J. S. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage Focus Editions, 154, 136.

- Byrne, E., Keuter, K., Voell, J., & Larson, E. (2000). Nurses’ job satisfaction and organizational climate in a dynamic work environment. Applied Nursing Research, 13(1), 46–49.

- Carlson, D. S., Grzywacz, J. G., & Zivnuska, S. (2009). Is work—Family balance more than conflict and enrichment? Human Relations, 62(10), 1459–1486. doi:10.1177/0018726709336500

- Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(2), 249–276. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1999.1713

- Carlson, M. (2013). Performance: A critical introduction. UK: Routledge.

- Carmody, J., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(1), 23–33. doi:10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

- Creswell, J. D., & Lindsay, E. K. (2014). How does mindfulness training affect health? A mindfulness stress buffering account. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(6), 401–407. doi:10.1177/0963721414547415

- Dane, E. (2011). Paying attention to mindfulness and its effects on task performance in the workplace. Journal of Management, 37(4), 997–1018. doi:10.1177/0149206310367948

- Dane, E., & Brummel, B. J. (2014). Examining workplace mindfulness and its relations to job performance and turnover intention. Human Relations, 67(1), 105–128. doi:10.1177/0018726713487753

- Davey, M. M., Cummings, G., Newburn, C. V. C., & Lo, E. A. (2009). Predictors of nurse absenteeism in hospitals: A systematic review. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(3), 312–330. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00958.x

- Davidson, R. J. (2010). Empirical explorations of mindfulness: Conceptual and methodological conundrums. Emotion, 10, 8–11. doi:10.1037/a0018480

- Egan, T. M., Yang, B., & Bartlett, K. R. (2004). The effects of organizational learning culture and job satisfaction on motivation to transfer learning and turnover intention. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 15(3), 279–301. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1532-1096

- Fazio, J., Gong, B., Sims, R., & Yurova, Y. (2017). The role of affective commitment in the relationship between social support and turnover intention. Management Decision, 55(3), 512–525. doi:10.1108/MD-05-2016-0338

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

- Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65–78.

- Giluk, T. L. (2009). Mindfulness, big five personality, and affect: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 805–811. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.026

- Glomb, T. M., Duffy, M. K., Bono, J. E., & Yang, T. (2011). Mindfulness at work. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 30, 115–157.

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. doi:10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

- Gregoire, S., & Lachance, L. (2015). Evaluation of a brief mindfulness-based intervention to reduce psychological distress in the workplace. Mindfulness, 6(4), 836–847. doi:10.1007/s12671-014-0328-9

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 159–170. doi:10.1037/h0076546

- Harvey, P. (2000). An introduction to Buddhist ethics: Foundations, values, and issues. UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Herndon, F. (2008). Testing mindfulness with perceptual and cognitive factors: External vs. internal encoding, and the cognitive failures questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(1), 32–41. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.07.002

- Hofmans, J., De Gieter, S., & Pepermans, R. (2013). Individual differences in the relationship between satisfaction with job rewards and job satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 82(1), 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2012.06.007

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hugh-Jones, S., Rose, S., Koutsopoulou, G. Z., & Simms-Ellis, R. (2018). How is stress reduced by a workplace mindfulness intervention? A qualitative study conceptualizing experiences of change. Mindfulness, 9(2), 474–487. doi:10.1007/s12671-017-0790-2

- Hulsheger, U. R., Alberts, H. J., Feinholdt, A., & Lang, J. W. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: The role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 310–325. doi:10.1037/a0031313

- Iacobucci, D., Saldanha, N., & Deng, X. (2007). A meditation on mediation: Evidence that structural equations models perform better than regressions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2), 139–153. doi:10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70020-7

- Jain, S., & Nair, S. K. (2013). Research on work-family balance: A review. Business Perspectives and Research, 2(1), 43–58. doi:10.1177/2278533720130104

- Janssen, O., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2004). Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 368–384.

- Jha, A. P., Morrison, A. B., Parker, S. C., & Stanley, E. A. (2017). Practice is protective: Mindfulness training promotes cognitive resilience in high-stress cohorts. Mindfulness, 8(1), 46–58. doi:10.1007/s12671-015-0465-9

- Johnson, R. C., Kiburz, K. M., Dumani, S., Cho, E., & Allen, T. D. (2011). Work-family research: A broader view of impact. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 4(3), 389–392. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2011.01358.x

- Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002). Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 530–541.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Coming to our senses: Healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. UK: Hachette UK.

- Kelloway, E. K., Gottlieb, B. H., & Barham, L. (1999). The source, nature, and direction of work and family conflict: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4(4), 337–346.

- Lindsay, E. K., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mechanisms of mindfulness training: Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 48–59. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.011

- Mahon, M. A., Mee, L., Brett, D., & Dowling, M. (2017). Nurses’ perceived stress and compassion following a mindfulness meditation and self-compassion training. Journal of Research in Nursing, 22(8), 572–583. doi:10.1177/1744987117721596

- Marks, S. R., & MacDermid, S. M. (1996). Multiple roles and the self: A theory of role balance. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(2), 417–432. doi:10.2307/353506

- Mattila, A. S., & Enz, C. A. (2002). The role of emotions in service encounters. Journal of Service Research, 4(4), 268–277. doi:10.1177/1094670502004004004

- McGhee, P., & Grant, P. (2015). The influence of managers’ spiritual mindfulness on ethical behavior in organizations. Journal of Spirituality, Leadership and Management, 8(1), 12–33. doi:10.15183/slm2015.08.1113

- Mesmer-Magnus, J., Manapragada, A., Viswesvaran, C., & Allen, J. W. (2017). Trait mindfulness at work: A meta-analysis of the personal and professional correlates of trait mindfulness. Human Performance, 30(2), 1–20. doi:10.1080/08959285.2017.1307842

- Mrayyan, M. T. (2007). Jordanian nurses’ job satisfaction and intent to stay: Comparing teaching and non-teaching hospitals. Journal of Professional Nursing, 23(3), 125–136. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.12.006

- Nyanaponika. (1949). Abhidhamma Studies: Buddhist explorations of consciousness and time. Bodhi (Ed.). USA: Wisdom Publications Inc.

- Pattusamy, M., & Jacob, J. (2017). Testing the mediation of work-family balance in the relationship between work-family conflict and job and family satisfaction. South African Journal of Psychology, 46(2), 218–231. doi:10.1177/0081246315608527

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Reb, J., Narayanan, J., & Chaturvedi, S. (2014). Leading mindfully: Two studies on the influence of supervisor trait mindfulness on employee well-being and performance. Mindfulness, 5(1), 36–45. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0144-z

- Reb, J., Narayanan, J., Chaturvedi, S., & Ekkirala, S. (2017). The mediating role of emotional exhaustion in the relationship of mindfulness with turnover intentions and job performance. Mindfulness, 8(3), 707–716. doi:10.1007/s12671-016-0648-z

- Reb, J., Narayanan, J., & Ho, Z. W. (2015). Mindfulness at work: Antecedents and consequences of employee awareness and absent-mindedness. Mindfulness, 6(1), 111–122. doi:10.1007/s12671-013-0236-4

- Ritter, D. (2011). The relationship between healthy work environments and retention of nurses in a hospital setting. [Review]. Journal of Nursing Management, 19(1), 27–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01183.x

- Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2012). Organizational Behavior (15th ed.). USA: Prentice Hall.

- Robins, C. J., Keng, S. L., Ekblad, A. G., & Brantley, J. G. (2012). Effects of mindfulness‐based stress reduction on emotional experience and expression: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 117–131. doi:10.1002/jclp.20857

- Saari, L. M., & Judge, T. A. (2004). Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Human Resource Management, 43(4), 395–407. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-050X

- Tischler, L., Biberman, J., & McKeage, R. (2002). Linking emotional intelligence, spirituality and workplace performance: Definitions, models and ideas for research. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17(3), 203–218. doi:10.1108/02683940210423114

- Valcour, M. (2007). Work-based resources as moderators of the relationship between work hours and satisfaction with work-family balance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1512–1523. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1512

- Virgili, M. (2015). Mindfulness-based interventions reduce psychological distress in working adults: A meta-analysis of intervention studies. Mindfulness, 6(2), 326–337. doi:10.1007/s12671-013-0264-0

- Walach, H., Buchheld, N., Buttenmüller, V., Kleinknecht, N., & Schmidt, S. (2006). Measuring mindfulness—The Freiburg mindfulness inventory (FMI). Personality and Individual Differences, 40(8), 1543–1555. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025

- Watanabe, M., & Falci, C. D. (2016). A demands and resources approach to understanding faculty turnover intentions due to work-family balance. Journal of Family Issues, 37(3), 393–415. doi:10.1177/0192513X14530972

- Weinstein, N., Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). A multi-method examination of the effects of mindfulness on stress attribution, coping, and emotional well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 374–385. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.12.008

- Wongtongkam, N., Krivokapic-Skoko, B., Duncan, R., & Bellio, M. (2017). The influence of a mindfulness-based intervention on job satisfaction and work-related stress and anxiety. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 19(3), 134–143. doi:10.1080/14623730.2017.1316760

- Zait, A., & Bertea, P. S. P. E. (2011). Methods for testing discriminant validity. Management and Marketing Journal, 9(2), 217–224.

- Zivnuska, S., Kacmar, K. M., Ferguson, M., & Carlson, D. S. (2016). Mindfulness at work: Resource accumulation, well-being, and attitudes. Career Development International, 21(2), 106–124. doi:10.1108/CDI-06-2015-0086