Abstract

Loyalty programmes are not a neglected research topic. Much of this research is in the context of developed economies and within the product/service domains of marketing, and has not included loyalty programmes for fuel purchases. The purpose of this study was to determine the factors that contribute to effective loyalty programmes at fuel retailers in an emerging economy and tested an established model within this context and used literature grounding within Relationship Marketing Theory. This study used a qualitative approach and conducted nine in-depth interviews. The analyses were done using inductive content analysis. It explored areas such as the customer’s view on the structure of the loyalty programme and rewards, and the customer’s role in its design. Many new findings emerged, such as the participants’ indifference to tier progression. The main findings indicate that theories/models developed in advanced economies do not necessarily work in emerging economies and this resulted in the construction of a new model. This study contributed to new academic knowledge within the South African context, as well as in the way that fuel loyalty programmes operate at a fundamental level and the management thereof.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Loyalty programmes are not a neglected research topic. However, much of this research is done within developed economies like the USA, and within the product/service domains like grocery purchases and has not included loyalty programmes for fuel purchases. This study tested USA academic theories within a South African context. It interviewed loyalty card holders for a specific fuel retailer to determine what the South African consumers think on issues such as the structure of the loyalty programme, rewards, and the consumer’s role in the design of the loyalty programme. Many new findings emerged, such as the participants’ indifference to tier rewards and tier progression. The most significant contributions of this research is that theories developed in advanced economies do not necessarily work in emerging economies and lead to the development of theories that are applicable in South African context. It also contributed in the way that fuel loyalty programmes operate at a fundamental level and the management thereof.

1. Introduction

Loyalty programmes in the fuel industry in South Africa—an emerging economy—are a very recent development, as the industry has been regulated by the government, and any form of promotion in this sector has been disallowed. The term “emerging economy” was created in 1981 (Brinkman et al., Citation2015) and is described as giving businesses the opportunity to act responsibly and “do good”. Emerging economies are generally seen to be countries exhibiting high growth and market potential with rapid industrialisation; but they are also risky and volatile in that they are still underdeveloped and in the process of becoming developed economies (Munro et al., Citation2018; Park & Ungson, Citation2019). South Africa is one of the leading emerging economies in Africa in terms of being a potential investment destination. It was also the only African country to be ranked in the top 15 emerging economies worldwide (Integrate Immigration, Citationn.d.). South Africa has a relatively high GDP per capita (US$11,035); financial systems are sophisticated, robust and well-regulated; the banking sector has long been rated among the top 10 globally; and the country has world-class information and communications technology (Grant Thornton, Citation2012).

Loyalty programmes are defined as programmes that boost repeat buying, thereby advancing retention rates by providing incentives for customers to buy more frequently and in larger volumes (Wang et al., Citation2016). Kang et al. (Citation2015) reported that these benefits or rewards can be either financial/economic or non-financial/social. By the very nature of this definition, loyalty programmes have to embrace the concept of relationship marketing, which can take many forms. Relationship marketing theory (RMT) has the potential to increase customers’ understanding of many business aspects, such as loyalty programmes (Hunt et al., Citation2006). The South African market is significantly involved in loyalty programmes, and customers tend to stay with loyalty programmes for several years. According to Norkfolk and Camp (Citation2015), 57 per cent of South Africans will stay committed to a loyalty programme for at least three years before they consider switching. The industries that have shown high customer retention are banks, supermarkets, clothing shops, medical aid service providers, and mobile phone companies. Despite the popularity of loyalty programmes and the belief that such initiatives help to enhance customer loyalty, there are arguments that these are ineffective. Meyer-Waarden (Citation2015) reported that less than half of loyalty programme members find the scheme to be value-adding, and that the impact on customer patronage is often lower than most companies’ expectations. Voorhees et al. (Citation2015) argued that, despite the substantial investments that companies make in loyalty programmes, these companies and marketers are given little indication of the overall efficacy of their loyalty programmes in driving customers’ spending and overall customer retention. Despite recent studies on the future of loyalty programmes (Gereffi & Wyman, Citation2014; McCall & McMahon, Citation2016; Nielsen, Citation2016), there is still a lack of evidence about the effectiveness of loyalty programmes in the fuel industry overall.

As a first step towards determining the factors that contribute to effective loyalty programmes at fuel retailers in an emerging economy, this study is rooted in the work done by McCall and Voorhees (Citation2010) and their model of loyalty programme effectiveness, as well as in RMT. To achieve this aim, the following areas are explored:

the customers’ view on the structure of the loyalty programme;

the customers’ view on how the loyalty rewards are structured; and

the customers’ role in the design of loyalty programmes.

This study contributes on two levels. Theoretically, it contributes to the body of knowledge determining the factors that add to the effectiveness of fuel loyalty programmes in an emerging economy—a much-neglected research area for South African academia. The theoretical underpinning of this research is based on a USA developed model and therefore the development of a merging market model will contribute to the enhancement of academic literature. On a managerial/practical level the findings provides suggestions for an effective practical implementation of fuel loyalty programmes and adds to the successful management thereof.

The study begins with a review of the literature on the South African fuel market, followed by a discussion of relationship marketing and of loyalty programmes. The nature of the study’s objectives called for a qualitative research approach, as it also endeavours to develop a revised model that is detailed in the methodology section. There after follows a discussion of the results and findings, managerial implications, limitations, avenues for future research, and the conclusion.

2. Literature review

The literature review section endeavours to create a feel for the current fuel industry in South Africa, an emerging economy. It highlights the main players with their corresponding loyalty programmes. Next, relationship marketing is discussed and how it links to loyalty programmes. The section on loyalty programmes discusses the McCall and Voorhees model (McCall & Voorhees, Citation2010), which underpins this study. It is worth mentioning that this model was developed in the USA.

2.1. The South African fuel market

In 2018, the South African oil and gas industry reached a value of 11.5 USD billion (ZAR 252 billion), which was 239.9 million barrels of oil. This represented 0.5 per cent of the global market. It is forecast that this market will grow to 12.8 USD billion (ZAR 169.3 billion) by 2023. There are two multinational oil and gas companies that supply fuel to retailers operating in South Africa (SA), of which Royal Dutch Shell is the largest. BP PLC is the second largest multinational company. Sasol Ltd is the third largest oil and gas company operating in SA, but is locally owned, with its head office in Johannesburg. PetroSA, the fourth largest oil and gas company in South Africa, is wholly owned by the government of South Africa, and is based in Cape Town (Marketline, Citation2019). The Fuel Retailers Association (FRA) lists many fuel retailers as members of their association, including Shell, Total, Ener-gi, BP, Engen, Sasol, and Caltex (www.fuelretailers.co.za). According to Nel (Citation2018), many of these fuel retailers have loyalty programmes and loyalty partners. Some fuel retailers have more than one loyalty programme, as shown in Table below.

Table 1. Fuel reward system in South Africa

Although the websites of the fuel retailers and their corresponding reward partners are freely available, the amount of information is overwhelming, and can be confusing. The programmes are very varied, and are difficult to understand. The customer is rewarded with loyalty-specific points on fuel purchases, but this varies with the amount spent. The conversion of points back to rand value in order to make other purchases is often lacking in the information.

2.2. Relationship marketing

Relationship marketing changed the marketing paradigm from a transactional to a relational perspective, which in turn led to understanding the lifetime value (LTV) of customers. It is therefore well-suited to developing loyal customers (Seth, Citation2017). Hunt et al. (Citation2006) listed 10 different forms of relationship marketing, including: “The long‐term exchanges between firms and ultimate customers, as implemented in ‘customer relationship marketing’ programs, affinity programs, loyalty programs, and as particularly recommended in the services marketing area”, which places any form of loyalty programme within the relationship marketing domain. Various authors have tried to describe relationship marketing; these definitions tend to vary slightly (Grönroos, Citation1996; Mulki & Stock, Citation2003; Sheth & Parvatiyar, Citation1995). In a nutshell, RMT maintains that customers enter into relational exchanges with firms when they believe that the benefits derived from such relational exchanges exceed the costs. The benefits include: the belief that a particular partner can be trusted reliably, competently, and non‐opportunistically to provide quality market offerings; the partnering firm shares values with the customer; the customer experiences decreases in search costs; the customer perceives that the risk associated with the market offering is reduced; the exchange is consistent with moral obligations; and the exchange allows for customisation that better satisfies the customer’s needs, wants, tastes, and preferences. Furthermore, Hunt et al. (Citation2006) stated that a major drawback of marketing relationship theories and their various models is that they are all developed in advanced economies.

2.3. Loyalty programmes

In the emerging economy of South Africa, it is also encouraging to know that a study by Nielsen (Citation2016) suggests that South Africans are extremely loyalty programme-oriented. This study also concluded that about 62 per cent of South Africans are part of two to five loyalty programmes, while six per cent are members of six to 10 loyalty schemes. The interaction between these customers and their respective loyalty programmes is 82 per cent in-store, where loyalty cards are scanned after a service/product purchase. This is said to represent one of the highest physical uses of loyalty cards in the world (Nielsen, Citation2016). Loyalty programmes are defined as programmes that boost repeat buying, thereby advancing retention rates by providing incentives for customers to buy more frequently and in larger volumes (Wang et al., Citation2016). Earlier studies have provided several definitions of customer loyalty (Parasuraman et al., Citation1991; Woodside et al., Citation1989; Zeithaml et al., Citation1996), describing customer loyalty as a behavioural approach: customers are loyal if they continue to buy and use a product or service. More recent studies have demonstrated some similarities and contrasts with the earlier research.

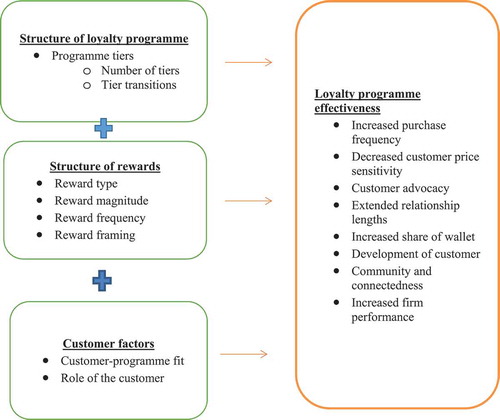

Based on Figure , there are three main categories that drive loyalty programme effectiveness: the structure of the loyalty programme; the structure of the rewards; and the customer factors. The structure of a loyalty programme can be explained as the number of tiers and tier transition. It is important for loyalty programmes to offer different tiers and to enable transition from one tier to the next. Tiers provide customers with a sense of identity, as they understand which tier group they belong to. Customers can also form relationships with other customers who belong to the same tier group. Tier transition is a loyalty customer’s ability to change tiers based on their behaviour, allowing the customer to change the frequency and magnitude of their consumption (McCall & Voorhees, Citation2010).

Tanford (Citation2013) suggested that the tier rewards system is often used, and that it provides customers with feelings of status when they reach a higher tier level than others who are in the lower tier levels. Steinhoff and Palmatier (Citation2014) agree, stating that tier rewards are beneficial to a loyalty programme, as they will create a perception of status among the target markets and bystanders. Customers are often delighted by rewards, viewing them as an additional currency that can be used to make further purchases. This means that the frequency and magnitude of the rewards programme directly impacts customers’ attitudes and participation in the loyalty programme (McCall & Voorhees, Citation2010).

With customer factors, it is important to remember that the customer is at the centre of any loyalty programme, as is the maintenance of this relationship. Kandampully et al. (Citation2015) argued that, to create loyal customers, marketers must be able first to create a sense of commitment between the business and its customers. This means that the more a business is committed to nurturing its customer relationship, the better the chances of the customer becoming loyal to the business over time. Customer participation must be at the core of a loyalty programme; the more customers participate and become a part of the process, the more open they become to sharing credit and blame with the firm (Kandampully et al., Citation2015).

In summarising the literature, many different kinds of loyalty programmes are operational in the South African fuel industry. McCall and Voorhees (Citation2010) proposed that, for a loyalty programme to be effective, it needs to be structured on three levels, each with its own requirements. The customer drives this loyalty system. Thus an important relationship exists between them and the business or loyalty programme. Whether this works in a booming and emerging economy like South Africa is what this study wants to determine. The methodology decribed below was used to obtain an answer.

3. Research methodology

An exploratory research design was employed to secure customers’ input via in-depth interviews. The study aimed to generate qualitative data to provide results, and flowed from NP Lekhuleni’s master’s dissertation (Lekhuleni, Citation2020), The impact of loyalty programmes on customer retention, published at the University of Johannesburg (the co-author of this article was the supervisor of the dissertation). Inductive reasoning was used for this study, as it aimed to uncover the factors that drive customers in the fuel business to use loyalty programmes. The main reason for using inductive approach was because this study’s contribution also lies in building new theories/models for the fuel industry in an emerging market. Tumele (Citation2015) stated that the inductive approach allows for new theories to be generated out of data. Bryman (Citation2012) agrees with this and states that inductive reasoning is used when theories or models are developed after the empirical research and findings are presented.

3.1. Target group and sample decision

Kemparaj and Chavan (Citation2013) stated that there are no established rules for the sample size in qualitative studies. Most qualitative studies tend to use non-probability sampling, because the participants are deliberately sampled to reflect certain characteristics and features of the target population (Mokoena, Citation2017; Vehovar et al., Citation2016). A good sample number is between six and 12, especially when researching hard-to-access populations (Mokoena, Citation2017). Initially twelve interviews were planned, but only nine were completed, as the participants provided similar information. According to Fusch and Ness (Citation2015), data saturation is reached when the researcher has gathered enough information to replicate the study and when no new information is forthcoming. The nine interviews were done on three different sites of a single fuel retailer, with a mixture of males and females; no age restrictions were imposed. The only inclusion criterion was that of being an active user of the fuel retailer’s loyalty programme. The interview protocol was guided by the McCall and Voorhees (Citation2010) model. Bryman (Citation2012) mentions that in making our questions selection, we should be guided by the principle that the research questions we choose should be related to one another. If they are not, our research will probably lack focus and we may not make as clear a contribution.

3.2. Data analysis

This study employed the inductive procedural model of Mayring (Citation2014) to guide the research, as illustrated in Figure .

Step 1—Research questions. Formulate a clear research question that fits an inductive logic, which means that it must be exploratory. The aim of this study was to determine the factors that contribute to effective loyalty programmes at a fuel retailer in an emerging economy. The theoretical background must be described using the literature and previous studies. This section of the study has been covered in the literature review section.

Step 2—Category definition and level of abstraction. The category definition, which has to be explicit, serves as a selection criterion to determine the relevant material from the texts. The level of abstraction defines how specific or general categories have to be formulated, which is central to inductive category formation. For the purposes of this study, the areas of exploration were operationalised into the following category definitions: exploring the customer’s view on the structure of the loyalty programme; exploring the customer’s view on how the loyalty rewards are structured; and exploring the customer’s role in the design of loyalty programmes. This step has been covered in the introduction, literature review, and participants’ feedback from the interviews. The transcribed interviews served as the unit of analysis.

Step 3—Coding the text. Qualitative data coding decisions should be based on the paradigm and theoretical approach of the study. Attribute coding was used to log the essential descriptive information about the participants. To tap into the participants’ experience, in vivo coding was used to honour their voice and to ground the data analysis from their perspective. In vivo coding is also very effective for developing new theories (Saldana, Citation2009). Steps 3 to 7 were carried out on the transcriptions, with each step improving on the last.

Step 4—Revision. A revision in the sense of a pilot loop is necessary when the category system seems to stabilise. A check is done to see whether the category system fits the research question; if it does not, a revision of the category definition is necessary. A check is also done to see whether the degree of generalisation is sufficient. If there are only a few categories, then the level of abstraction is too general; and if there are many, then the level of abstraction is too specific.

Step 5—Final coding. All the material (in this case, the transcribed interviews) had to be worked through with the same rules—that is, category definition and level of abstraction.

Step 6—A list of categories emerged at the end of this process. They were grouped together to build themes, keeping in line with the research aim.

Step 7—Intra- or inter-coder check. The text was coded from the beginning to match the categories.

Step 8—Findings. Initially the findings were the list of categories. If categories have to be found for several text passages, a frequency analysis of the categories’ occurrence could be useful. The categories and the frequencies have to be interpreted in the direction of the research aim. Step 8 revealed the findings of this study, which are presented below.

4. Findings and discussion

The findings were derived from the answers provided in the in-depth interviews, and were formulated to reflect the main themes that emerged. Participants were anonymised, apart from identifying the site where they were interviewed, as per the attribute coding in Table . It was not the purpose of this study to differentiate on any demographics. Direct quotations were distinguished by referring to them as P1 to P9.

Table 2. Details of the participants

On exploring the customers’ view on the structure of the loyalty programme, it was revealed that the programme does not have any form of tiers or tier progression. This programme is single-levelled, and customers are only rewarded based on the amount of fuel they purchase. This did not seem to have a negative effect on the participants,

“And so far, I have never been disappointed” (P4).

The participants were more concerned with getting their due rewards when buying fuel.

“I would have to say that the most important factor is earning all my points every time I fill up” (P1).

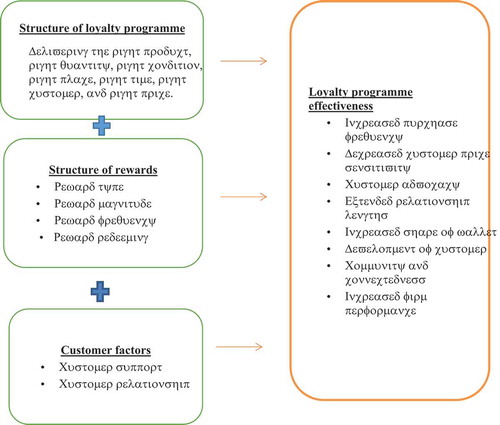

This finding is in stark contrast to the model of McCall and Voorhees (Citation2010), which stipulates that loyalty programmes should provide different numbers of tiers and the opportunity for tier transitions. However, the finding ties in with the seven “rights” of logistics: delivering the right product, in the right quantity and the right condition, to the right place at the right time for the right customer at the right price (Lai & Cheng, Citation2016; Porter & Kramer, Citation2019). This shows that, to succeed and to continue capturing customers’ attention, loyalty offers should always be reliable, and customers should always earn their rewards as promised to them by the loyalty programme.

Exploring the structure of loyalty programmes—specifically referring to the type of reward, magnitude of the reward, reward frequency, and reward framing—the following themes emerged. On the issue of magnitude and frequency, the customers disclosed a high level of excitement about earning rewards. This created an expectation that needed always to be met.

“I must always have my card with me to make sure that I don’t miss out on earning points” (P2).

“They make it a point that you never forget to swipe your … card; that is the first thing they ask for” (P6).

When participants were probed on the issue of reward types, most of them expressed a positive attitude towards having these rewards available to use, especially during periods of great financial difficulty.

“The highlight is just having the points readily available for rainy days” (P3).

“When times are really rough, these points do assist” (P9).

When the issue of reward framing was discussed, the customers felt that they were never involved in any framing of the reward.

“I do not believe that customers are or were involved in the framing of the loyalty programme” (P1).

“I have never been included in any discussions around the loyalty reward, be it through surveys or as a customer feedback” (P4).

The structure of reward findings is confirming—when dealing with the magnitude of reward and reward frequency—and in contrast when dealing with reward framing as per McCall et al.’s model. Chang and Taylor (Citation2016) also reported that firms should involve customers at various phases of the development of new offerings, given the notion that firms can improve their overall innovation performance by tapping into customers’ knowledge of needs and solutions. Customer value co-creation is defined by Ansari et al. (Citation2017) as “the benefit realised from the integration of resources through activities and interactions with collaborators in the customer’s service network”. Although the literature advocates the involvement of the customer in the creation of loyalty programmes, the participants were apathetic about this.

On exploring the customer factors and the participants’ knowledge of the level of support available, the findings were positive overall. The majority of the feedback demonstrated that a great level of support was available to customers, and the participants were aware of the support structures. Acquiring new customers is a critical component of any loyalty programme’s strategy, and it is key to create as much “buzz” as possible about the programme’s key benefits as well as about the support that comes with it when there are system failures (Nielsen, Citation2016).

“There is so much information readily available online regarding the programme” (P1).

“I had to call the (…) customer helpline to get assistance” (P2).

When the participants were asked to explain the factors that were most important to them, one overriding theme emerged: they expressed their excitement about earning loyalty points in the right quantities each time they fill their car with fuel.

“The highlight is just having the points readily available for rainy days” (P3).

“When times are really rough, these points do assist” (P9).

When asked to identify the least important factor to consider in the structure of the loyalty programme, site location came up. Most participants said that, because these points can be earned at almost every retailer of this brand, they often do not have a specific site they frequent.

“The location of the … site is not really important to me” (P8).

“As long as it’s a … site, and I know I will be getting points when I fill up” (P2).

From the above responses, it is evident that convenience is quite an important feature. Customers are only interested in getting their points in the most convenient manner, which explains their reluctance to commit to using only one specific site.

“I don’t have a specific site that I use” (P2).

This finding ties in with the research of Sundström and Radon (Citation2015) who stated that, for loyalty programmes to be successful and drive customers’ purchasing behaviour, they must be convenient.

Two other themes that were brought up throughout the interviews were the relationship with the retailer’s fuel attendants and the level of support provided by the staff on the ground. The participants valued the level of support that they got from the fuel attendants, and these attendants have proven to be quite helpful and knowledgeable in resolving queries.

“All my transactions and communication around the loyalty rewards has been with the fuel attendants” (P4).

“The fuel attendants are extremely helpful” (P3).

Most of the participants expressed great satisfaction with their dealings with the attendants, or the other support channels, when it came to query resolution. This finding ties in with the findings of Hunt et al. (Citation2006) that customers engage in relationships to achieve greater efficiency in their decision-making in order to reduce the task of information processing.

When it came to the lowlights of using the loyalty programme, the feedback was quite negative, as many of the participants had similar grievances. The strongest theme that emerged was dissatisfaction with the method of redeeming these points: the majority of the participants were unhappy with the fact that these points can only be used at a specific store.

“The fact that you can only redeem the points at a … store” (P1).

“They can try and broaden their offering like other companies have” (P3).

From the above, it is evident that many participants would prefer wider options when it comes to redeeming their rewards. Most of these participants alluded to the fact that other providers in similar industries were offering options such as financial returns, or using the points to pay for household utilities such as electricity and airtime.

In summary, the participants’ feedback reflected a positive outlook. The participants valued the overall benefits provided by loyalty rewards and, most importantly, the level of support that comes with it. The participants were not troubled with the issues of levels of tiers nor with customer involvement in the creation of this programme. It is evident that most customers value a loyalty programme that is easy to use, and one that does not take too much time. These findings led to the development of a revised model, illustrated in Figure .

5. Managerial implications

Managers should pay attention to convenience and reliability when developing fuel loyalty programmes in an emerging economy. This includes factors such as delivering the right product in the right quantity, in the right condition at the right place and at the right time. The loyalty programme should be easy to understand and easy to use.

Managers should also look at providing customers with more options in redeeming gathered rewards, and not restrict the participants’ choice. Customers also like to have product support and information from fuel attendants and from websites where they can get information on the programme. Therefore fuel attendants and websites should be well-informed and up to date to serve as information hubs. It is also vital that managers understand that relationship marketing requires distinguishing between loyalty programme transactions, which have a beginning, a short duration, and a sharp ending, and the relationship aspect of loyalty programmes, which necessitates an engagement and traces to previous agreements, and is longer in duration, reflective in nature, and ongoing. Many of the loyalty programmes are operated by third parties, which can create confusion. Managers should consider operating their own loyalty programme with its own website information.

6. Limitations and future research

This study was conducted in a major economically active province in South Africa, an emerging economy, and with one fuel retail brand. Therefore the results cannot be generalised. The study aimed, rather, to serve as a first step towards determining the factors needed for an effective fuel loyalty programme. Further studies could be carried out on other fuel retailers to expand on the model, and to conduct research in developed economies to determine whether similar results are obtained. Another study could use this newly developed model and test it in an emerging economy. It would also be interesting to explore a quantitative study in a similar scenario. A major contribution to the field of loyalty programmes could be to determine whether customers actually understand their programme’s reward structure. In other words, does the customer know how many points are earned when Rx fuel is purchased, and how that translates back into rand value. A comparative study could also determine whether there is a difference between loyalty partner programmes and fuel retailer-owned programmes.

7. Conclusion

This study was a first step towards determining the factors that contribute to effective loyalty programmes at fuel retailers in an emerging economy. It was rooted in the work done by McCall and Voorhees (Citation2010) and their model of loyalty programme effectiveness, and also explored the model’s factors. Different findings arose from this study from what was expected, especially in the structure of the loyalty programme model. This can be attributed to the emerging economy environment in which the model was tested, as this model was developed in the USA, a developed economy. Another factor could be that this model was tested in the fuel retailing industry. Nevertheless, this study’s contribution is extremely important within a South African context.

8. Ethical clearance

The proper ethical procedures were followed in line with the university’s structures and policies, and an ethical clearance certificate was issued for this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marius Wait

Marius Wait is an Associate Professor and the Head of Department: Marketing Management at the University of Johannesburg. He has supervised numerous M and PhD students and has a keen interest in the education of Sales and Direct Selling, the topic of his PhD. Apart from these research interests, he has also published numerous articles on Work Integrated Learning. This study “Exploring fuel loyalty programmes within a South African context” is the result of a Masters student thesis, wherein a previously disallowed concept is tested.

References

- (2019, November 19). https://www.discovery.co.za/reward-partners/bp

- (2019, November 19). https://www.bp.com/en_za/south-frica/home/products-and-services/strategic-partners/loyalty.htm

- (2019, November 19). https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/companies/shell-launches-their-own-loyalty-card-after-ending-partnership-with-clicks-39129189

- (2019, November 19). https://ucount.standardbank.co.za/personal/caltex/

- (2019, November 19). https://www.absa.co.za/personal/bank/absa-rewards/explore/

- (2019, November 19). https://www.edgars.co.za/edgars-club-members-get-more-when-they-fill-up-with-fuel-from-engen

- (2019, November 19). www.fuelretailers.co.za

- Ansari, A., Cowgill, G. A., Nicholls, L. E., Ramayya, J. P., Masina, R., McQuarters, A. R., & Raissyan, A. (2017) System and method for providing network support services and premises gateway support infrastructure (U.S. Patent Application 15/357,847).

- Brinkman, D. J., Tichelaar, J., van Agtmael, M. A., de Vries, T. P., & Richir, M. C. (2015). Self‐reported confidence in prescribing skills correlates poorly with assessed competence in fourth‐year medical students. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 55(7), 825,830. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.474

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Chang, W., & Taylor, S. A. (2016). The effectiveness of customer participation in new product development: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing, 80(1), 47–15. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.14.0057

- Fusch, P. I., & Ness, L. R. (2015). Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 20(9), 1408–1416.

- Gereffi, G., & Wyman, D. L. (Eds.). (2014). Manufacturing miracles: Paths of industrialization in Latin America and East Asia. Princeton University Press.

- Grönroos, C. (1996). Relationship marketing: Strategic and tactical implications. Management Decision, 34(3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251749610113613

- Hunt, S. D., Arnett, D. B., & Madhavaram, S. (2006). The explanatory foundations of relationship marketing theory. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 21(2), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420610651296

- Immigration, I. (n.d.) South Africa shines as emerging economy [Blog post]. retrieved August 20, 2019, from https://www.intergate-immigration.com/blog/south-africa-shines-as-emerging-economy/

- Kandampully, J., Zhang, T., & Bilgihan, A. (2015). Customer loyalty: A review and future directions with a special focus on the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(3), 379–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2014-0151

- Kang, J., Alejandro, T. B., & Groza, M. D. (2015). Customer-company identification and the effectiveness of loyalty programs. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 464–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.002

- Kemparaj, U., & Chavan, S. (2013). Qualitative research: A brief description. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, 67(3–4), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5359.121127

- Lai, K. H., & Cheng, T. E. (2016). Just-in-time logistics. Routledge. Hong Kong.

- Lekhuleni, N. P. (2020) The impact of loyalty programmes on customer retention [Master’s thesis]. University of Johannesburg.

- Marketline (2019, December) Industry profile oil & gas in South Africa. retrieved March 26, 2020, from https://0-advantage-marketline-com.ujlink.uj.ac.za/Analysis/ViewasPDF/south-africa-oil-gas-89068

- Mayring, P. (2014) Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solutions. [retrieved August 20, 2019, from https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

- McCall, M., & McMahon, D. (2016). Customer loyalty program management: What matters to the customer. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 57(1), 111–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965515614099

- McCall, M., & Voorhees, C. (2010). The drivers of loyalty program success: An organizing framework and research agenda. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 51(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965509355395

- Meyer-Waarden, L. (2015). Effects of loyalty program rewards on store loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 24, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.01.001

- Mokoena, N. (2017) Hindrances of digital music sales in South Africa: The perspective of recording label companies in Gauteng [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Johannesburg.

- Mulki, J. P., & Stock, J. (2003, May 15‐18) Evolution of relationship marketing. In H. S. Eric (Ed). Proceedings of Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing (CHARM), (pp. 52–59). East Lansing, MI Boca Raton, FL: Association for Historical Research in Marketing.

- Munro, V., Arli, D., & Rundle-Thiele, S. (2018). CSR engagement and values in a pre-emerging and emerging context. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 13(5), 1251–1272. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-04-2018-0163

- Nel, L. (2018, March 14) Where you can earn fuel rewards in South Africa and which loyalty cards to use [blog].Retrieved March 16, 2020, from https://louisnel.co.za/blog/where-you-can-earn-fuel-rewards-in-south-africa-and-which-loyalty-cards-to-use/

- Nielsen, R. W. (2016). Growth of the world population in the past 12,000 years and its link to the economic growth. Journal of Economics Bibliography, 3(1), 1–12.

- Norkfolk, K., & Camp, R. (2015) Customer loyalty (Project op5579). Opinium.

- Parasuraman, A., Berry, L. L., & Zeithaml, V. A. (1991). Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale. Journal of Retailing, 67(4), 420.

- Park, S. H., & Ungson, G. R. (2019). Rough diamonds in emerging markets: Legacy, competitiveness, and sustained high performance. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 26(3), 363-386. https://doi.org/10.1108CCSM-03-2019-0057

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2019). Creating shared value. In Managing sustainable business (pp. 323–346). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Saldana, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE Publications.

- Seth, J. (2017). Revitalizing relationship marketing. Journal of Services Marketing, 31(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-11-2016-0397

- Sheth, J. N., & Parvatiyar, A. (1995). Relationship marketing in consumer markets: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(4), 255‐271. https://doi.org/10.1177/009207039502300405

- Steinhoff, L., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Three perspectives for making loyalty programs more effective. Customer and Service Systems, 1(1), 147–153.

- Sundström, M., & Radon, A. (2015). Utilizing the concept of convenience as a business opportunity in emerging markets. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 6(2), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2015.6.2.14219

- Tanford, S. (2013). The impact of tier level on attitudinal and behavioral loyalty of hotel reward program members. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 34, 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.04.006

- Thornton, G. (2012) Emerging markets opportunity index: High growth economies. Retrieved August 15, 2019, from http://www.gtturkey.com/UD_OBJS/PDF/RPRARS/Emerging_Markets_Opportunity_Index2012.pdf

- Tumele, S. (2015). Case study research. International Journal of Sales, Retailing & Marketing, 4(9), 68–78.

- Vehovar, V., Toepoel, V., & Steinmetz, S. (2016). Non-probability sampling. In C. Wolf, D. Joye, T. W. Smith, & Yang-chih, F. (Eds.), The sage handbook of survey methods (pp. 329–345). Sage.

- Voorhees, C. M., White, R. C., McCall, M., & Randhawa, P. (2015). Fool’s gold? Assessing the impact of the value of airline loyalty programs on brand equity perceptions and share of wallet. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 56(2), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965514564213

- Wang, Y., Lewis, M., Cryder, C., & Sprigg, J. (2016). Enduring effects of goal achievement and failure within customer loyalty programs: A large-scale field experiment. Marketing Science, 35(4), 565–575. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2015.0966

- Woodside, A. G., Frey, L. L., & Daly, R. T. (1989). Linking service quality, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intention. Journal of Health Care Marketing, 9(4), 5–17.

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251929