Abstract

Value co-creation has become an essential strategy in business that encourages customer involvement in creating products that meet customer demands and have superior value. Brand image and e-service quality are still important factors that influence customer decision making in purchasing products online. The purpose of this study is to identify the role of value co-creation, brand image, and e-service quality toward patronage intentions in the online Muslim fashion industry with a moderating effect of religiosity and mediated by customer perceived value and customer satisfaction. This study was designed using a purposive sampling method involving 301 online customers from several Muslim fashion brands in Indonesia. Data were analyzed utilizing Structural Equation Model (SEM) with SmartPLS 3.0. The main point of our findings in this study is that value co-creation, brand image, and e-service quality have an indirect effect on patronage intentions through customer perceived value and customer satisfaction. In contrast, the moderating effect of religiosity has no significant effect on patronage intentions. This research provides academic contributions and adds value to existing theories where value co-creation can be applied online in non-service sectors such as the fashion industry that is not much analyzed. Furthermore, the managerial implication of this research for industrial practitioners is to implement value co-creation within the company, improve the e-service quality, and develop products that have a strong brand image that can increase sales value, leading to the company’s competitive advantage.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The largest Muslim population in the world is Indonesia, with 87% of the population being Muslim. Therefore, the need for Muslim fashion products in Indonesia continues to increase. Since the global COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a change in retail, where customers are accustomed to meeting Muslim fashion needs by shopping online. Customers want Muslim fashion products that have superior value in quality and benefits. Meanwhile, marketers want consumers to return to online stores to buy their products. This study accommodates the interests of each party by identifying the role of value co-creation, brand image, and e-service quality that can enhance patronage intentions through customer perceived value and customer satisfaction.

1. Introduction

One of the primary objectives of a business substance is to obtain a competitive advantage by creating superior customer value through the products or services offered. Companies should build strategic plans to create value according to customer preferences to stay competitive. In contrast to the past, where customers were passive value recipients, today’s dynamic market growth has made customers part of value co-creation. Value co-creation has become a significant subject in marketing, where there are numerous actors involved in value creation, including the value recipients themselves, namely customers (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2016).

The relationship and dynamic process between the involvement of numerous actors, especially customers in the value co-creation framework, has attracted the attention of researchers to be explored. With customer participation in value co-creation, customers will feel a part of the company, thereby creating social and economic value (Thomas et al., Citation2020). Value co-creation can increase satisfaction for actively participating customers compared to passive customers (Navarro et al., Citation2016). The significance of value co-creation supported by social media can also encourage the development of new products and services in the fashion industry, which leads to greater corporate profits (Scuotto et al., Citation2017).

In addition to value co-creation, e-service quality is also one of the crucial elements that can contribute to marketing success in the digital era. Since the global COVID-19 pandemic, the most important thing has resulted in changes in the retail world, where customers are accustomed to new ways of shopping online (Roggeveen & Sethuraman, Citation2020). When online shopping has become the primary consumption method, the customer demand for e-services quality is increasing. E-services quality, such as information quality and service interaction quality, is a new marketing strategy implemented by e-retailers to increase customer purchase intention online (M. Zhang et al., Citation2020). By improving the e-services quality, success in online business is easier to obtain (Tsao et al., Citation2016).

Another crucial factor that strongly influences purchasing decisions is brand image. In online marketing using social media platforms, a positive brand image strengthens emotional bonds with customers, so they are willing to buy the brand and pay a premium price (Barreda et al., Citation2020). Brand image can also provide relevant information about the brand’s position in the market by showing the strength, preference, and uniqueness compared to other brands through the customer perceived value (Gensler et al., Citation2015). This customer perceived value is an essential component that can drive the success of a business because customer perceived value can affect customer satisfaction which leads to patronage intentions (Kusumawati et al., Citation2020).

While in the Muslim fashion industry, the level of religiosity owned by customers also has a role in influencing purchasing decisions, so that this variable is also important to study. Religiosity can influence individual attitudes, values, and purchasing decisions (Agarwala et al., Citation2019). Religiosity strongly correlates with the type of clothing worn by Muslim customers, so marketers can design marketing strategies that suit their target market (Aruan & Wirdania, Citation2020). The right marketing strategy will increase patronage intentions, which is related to the long-term success of the retail business because it can generate loyal customers (Southworth, Citation2019).

Previous research on value co-creation, brand image, e-services quality, and religiosity has been done. Where value co-creation increases customer perceived value (González-Mansilla et al., Citation2019; Xie et al., Citation2020) and customer satisfaction (Kim et al., Citation2019a; Opata et al., Citation2021). Brand image has a positive influence on customer perceived value (Huang et al., Citation2019; Lien et al., Citation2015) and customer satisfaction (Mohammed & Rashid, Citation2018; Song et al., Citation2019; Rahi et al., Citation2020). The e-services quality affects the customer perceived value (Jiang et al., Citation2016; Li & Shang, Citation2020) and customer satisfaction (Khan et al., Citation2019; Rita et al., Citation2019). Religiosity affects patronage intentions (Jamal & Sharifuddin, Citation2015; Deb et al., Citation2020; Kusumawati et al., Citation2020).

Exploration related to patronage intentions in the Muslim fashion industry has been carried out by Kusumawati et al. (Citation2020). However, the study only looked at religiosity, customer perceived value, and satisfaction. This study added value co-creation, brand image, and e-services quality variables. Value co-creation can be applied to new product development and other types of innovation in the fashion industry (Thomas et al., Citation2020) that lead to patronage intentions but are still rarely studied. Brand image is added because of its association with customer perceived value, affecting patronage intentions. In contrast, the e-services quality is added based on the recommendations of previous researchers (Kusumawati et al., Citation2020). In addition, in this study, religiosity is used as a moderator that strengthens the relationship between customer perceived value and patronage intentions and strengthens the relationship between customer satisfaction and patronage intentions. Value Co-creation exploration that has been carried out previously by González-Mansilla et al. (Citation2019) and Xie et al. (Citation2020) has concentrated more on the service sector, such as hospitality and tourism, while in this study it was carried out in the non-service sector, namely the fashion industry.

The purpose of this study is to fill the existing knowledge gap by exploring the effect of value co-creation, brand image, and e-services quality on patronage intentions by mediating customer perceived value and customer satisfaction, also moderation of religiosity. This study contributes to the scientific level of marketing management by developing a better theoretical understanding of value co-creation that can be applied online to the non-service sector. This study holistically offers useful information on how value co-creation, brand image, and e-service quality can empirically increase online patronage intentions.

The structure of the paper proceeds follows: The literature review contains an in-depth definition of the variables used based on the currently available literature, followed by the development of hypotheses and research model. The methodology contains data collection, measurement of each variable, and statistical data analysis methods. The results section presents the statistical results and evaluation of the structural model. Then proceed with a discussion on the obtained research findings. The last section is a conclusion that contains managerial implications, limitations, and suggestions for further research.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Value co-creation

One of the essential premises in the concept of Service-Dominant Logic formulated by Lusch and Vargo (Citation2006) is that the customer is always the co-creator of value. The value co-creation process always involves the participation of the customer. Value co-creation is a collaborative process between customers and companies to create value to improve customer satisfaction and experience (González-Mansilla et al., Citation2019). Customers are no longer passive recipients of value but act as co-creators in creating benefits for customers.

According to Ranjan and Read (Citation2016), value co-creation can be divided into two main activities: co-production and value in use. In co-production, customers share information and knowledge with the company during the product design stage (Chen et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, in value in use, customers use the product and inform their evaluation (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004). Meanwhile, according to Yi and Gong (Citation2013), value co-creation involves customers as active partners in relational exchanges for the entire chain of value creation through information seeking, information sharing, and responsible behaviour, as well as feedback, advocacy, helping, and tolerance. The basis of the interactions between customers and companies in the value co-creation are dialogue, access, risk-benefit, and transparency (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004).

2.2. Brand image

According to Keller (Citation2009), brand image is the customer’s perception and preference for a brand stored in the customer’s memory. Nisar and Whitehead (Citation2016) describe the brand image as the overall image that customers receive from a brand, including identification or differentiation of other brands, brand personality, and the benefits of brand selection. In a competitive business world, a brand image that can give a different impression in the eyes of customers can help companies differentiate themselves from competitors to gain a competitive advantage.

This brand image is a customer response to product characteristics obtained from observations and consumption. Mitra and Jenamani (Citation2020) defines brand image as a perception in the customer’s memory formed from the strength and uniqueness of brand associations. While in economic terms, brand image is the utility that customers get from consuming a brand, which reflects an evaluation of brand associations embedded in customers (Hofmann et al., Citation2019).

2.3. E-Service quality

In their study, Parasuraman et al. (Citation2005) claim that e-service quality broadly covers all phases of customer interaction with online sites, which is described by the extent to which the site facilitates all shopping, purchasing, and delivery activities. The e-services that customers encounter during online shopping consist of information retrieval services, transaction services, fulfilment services, and after-sales services (Xu et al., Citation2017). The e-service quality describes the level of service that customers get when shopping online from before the purchase, during the purchase, and after the purchase ends.

Blut (Citation2016) conceptualizes e-service quality into 4 main dimensions: online site design, fulfilment, customer service, and customer privacy, which ultimately affect the overall perception of e-service quality. Meanwhile, Rowley (Citation2006) describes e-services as actions or businesses whose delivery is mediated by information technology. In internet-based business, the quality of this e-service is one of the important elements that determine success or failure. Rita et al. (Citation2019) states that the quality of electronic services is an overall advantage or service excellence in an online business, which in turn can create customer satisfaction and trust.

2.4. Customer perceived value

Customer perceived value can be portrayed from financial, quality, benefit, social, and emotional perspectives. According to a financial viewpoint, customer perceived value is the distinction between the most exorbitant cost a customer will pay for a product and the actual cost (Kuo et al., Citation2009). Meanwhile, from a quality perspective, the customer perceived value can The benefits perspective shows the customer’s overall assessment of the product’s benefits to be received and what is given or sacrificed (Zeithaml, Citation1988). From a social perspective, the perceived value lies in the product’s ability to enhance self-concept or social image in the community (Sweeney & Soutar, Citation2001). Meanwhile, the perception of emotional value is obtained from customer interactions with the products offered (Kusumawati et al., Citation2020).

Mustak (Citation2019) classifies perceived value resulting from customer participation into four distinct, interrelated categories: functional, economic, relational, and strategic. From the customer’s perspective, perceived value is the trade-off between what customers get in terms of benefits and quality with what they incur in costs and sacrifices (El-Adly & Eid, Citation2017). In an online shopping situation, the customer perceived value is obtained at pre-purchase, where the customer explores the perceived benefits with the costs incurred (Chen & Dubinsky, Citation2003).

2.5. Customer satisfaction

In essence, according to Kotler et al. (Citation2018), customer satisfaction refers to feelings of pleasure or individual satisfaction related to the suitability between product performance and expectations. As an undimensional construct, customer satisfaction is often used to measure overall satisfaction with the store and after purchase through affective and cognitive evaluations (Fuentes-Blasco et al., Citation2017). Customer satisfaction is a response to the accumulation of shopping and consumption experiences made by customers on a brand.

In the fashion industry, customer satisfaction is closely related to the quality of products and services based on the purchase experience (Wang et al., Citation2019). In line with that, Baker and Crompton (Citation2000) suggested that customer satisfaction is the emotional and psychological result of the customer experience. So that customer satisfaction is seen as a positive state of mind that tends to affect patronage intentions (Söderlund & Colliander, Citation2015).

2.6. Religiosity

Religiosity shows the degree to which people are committed to their religion and lessons, with demeanors and practices that reflect the values and standards of the religion they hold (Delener, Citation1990). Religiosity can influence customer decision making through the cognitive influence and behaviour of individuals who adapt to their religious teachings. Religiosity plays a vital role in customer acceptance of opinions and values per their beliefs, thereby influencing customer attitudes towards religious products and economic shopping behaviour (Agarwala et al., Citation2019).

According to Aruan and Wirdania (Citation2020), religiosity refers to the level of individual faith/obedience in believing and carrying out the religious teachings they adhere to. This religiosity has two dimensions, namely, religious beliefs and religious practices. These are important social factors that can influence customer behaviour from a religious point of view and religious values that are believed to be (Zamani-Farahani & Musa, Citation2012). Since religiosity is a factor that can influence individual behaviour (Eid & El-Gohary, Citation2015), religiosity can be a significant factor related to consumption patterns (Cleveland et al., Citation2013). Religiosity shapes brand perceptions, influence customer preferences for a product and influence customer consumption status in purchasing behaviour (O’Cass et al., Citation2013).

2.7. Patronage intention

Patronage intention is defined as a customer’s willingness to interact, buy, recommend, and revisit an online store (Baker et al., Citation2002). This patronage intention is an indicator that determines whether a customer will return to visit a store or move to another store. Mathwick et al. (Citation2001) explain the same thing, where a patronage intention is a form of customer willingness to consider, recommend, or repurchase from the same marketer in the future.

Patronage intentions can strongly predict buying behaviour, whether customers will revisit the store and make repeat purchases. This patronage intention is influenced by previous shopping experiences, store atmosphere, and customer hedonic values (Afaq et al., Citation2020). The visual design of online sites, the quality of information, entertaining and educational content can also influence patronage intentions (Zhang et al., Citation2020).

2.8. Hypotheses development

In value co-creation, there is high customer involvement through the exchange of knowledge and information (Opata et al., Citation2019) so that no value is obtained until customer information and ideas are used (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2006). The value of co-creation results depends on the situation and the individual who does it (Prebensen & Foss, Citation2011). Value co-creation will occur in the fashion industry if manufacturers provide a conducive environment for customer participation. Customer perceived value is a cognitive consequence of value co-creation (Yi & Gong, Citation2013). Chiu et al. (Citation2019), González-Mansilla et al. (Citation2019), and Xie et al. (Citation2020) has proven the effect of value co-creation on customer perceived value. Furthermore, value co-creation will create a final product that follows customer needs, thereby increasing customer satisfaction with the products offered. Customer satisfaction comes from a feeling of belonging to a co-created product (Hunt et al., Citation2012). The development of customer behaviour during value co-creation can also increase customer satisfaction (Vega-Vazquez et al., Citation2013; Assiouras et al., Citation2019). This is supported by previous research regarding the relationship between value co-creation and customer satisfaction (Grissemann & Stokburger-Sauer, Citation2012; Navarro et al., Citation2016; Kim, Tang et al., Citation2019; and. Yang et al., Citation2019). Based on the existing arguments and research, the authors formulate the following hypotheses:

H1: Value co-creation has a positive effect on customer perceived value.

H2: There is a positive influence of value co-creation on customer satisfaction.

The brand image formed due to customer interactions with products affects customer attitudes and beliefs that shape customer behaviour. According to (Hsieh et al., Citation2004), a successful brand image allows customers to recognize their needs in a brand and differentiate the brand from its competitors. Brand image builds product character that encourages a positive mindset when thinking about a brand (Dewi et al., Citation2020). Brand image affects customer perceived value functionally, hedonic, socially and financially (Kim et al., Citation2019), where customers match a brand’s image with their self-image (Chae et al., Citation2020). Previous research found that brand image is an antecedent of customer perceived value (Cretu & Brodie, Citation2007; Lai et al., Citation2009; Ryu et al., Citation2012; Lien et al., Citation2015; Huang et al., Citation2019). In practice, image captured by customers is not the same depending on the expected impression, experience, and contact with the brand, so the level of satisfaction is also different. Customers believe that a brand with a positive image guarantees product quality so that it does not cause post-purchase disappointment. Knowing product quality through brand image will minimize purchase risk, thereby increasing satisfaction (Pranata et al., Citation2020). Previous research has proven that brand image influences customer satisfaction (Martenson, Citation2007; Lai et al., Citation2009; Mohammed & Rashid, Citation2018; song et al., Citation2019; Rahi et al., Citation2020). Based on the theoretical logic and empirical results above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Brand image has a positive influence on customer perceived value.

H4: There is a positive influence of Brand Image on Customer Satisfaction.

According to (Tsao & Tseng, Citation2011), an important aspect in the quality of the e-services is meeting customer needs. E-retailers provide information on products sold, delivery times, and product returns (Tsao et al., Citation2016). Improving the quality of the e-services by providing complete information will meet customer perceived value. The quality of e-services is judged by the services provided, responses to questions asked, and post-purchase problem solving (Parasuraman et al., Citation2005). Service quality has a close relationship with customer perceived value in terms of service and product sales (Parasuraman & Grewal, Citation2000; Hu et al., Citation2009). Empirical studies have been carried out by several analysts regarding the effect of e-service quality on customer perceived value (Chen & Dubinsky, Citation2003; Bauer et al., Citation2006; Kuo et al., Citation2009; Jiang et al., Citation2016; Tsao et al., Citation2016; Li & Shang, Citation2020). On the other hand, the success of Business to Consumer (B2C) is strongly influenced by customer satisfaction with the services provided by e-retailers (Shin et al., Citation2013; Khan et al., Citation2019). Customer satisfaction arises because of the cognitive evaluation of the performance of e-service attributes that can meet customer expectations. The level of customer satisfaction is influenced by the ease of access and speed of e-services, customer experience, frequency of service use, and disconfirmation of the time required to select services (Shankar et al., Citation2003; Aryati & Syah, Citation2018). Several researchers have explored the relationship between e-service quality and customer satisfaction (Chang et al., Citation2009; Gounaris et al., Citation2010; Vos et al., Citation2014; Xiao, Citation2016; Rita et al., Citation2019; Zarei et al., Citation2019). In line with the arguments above, the following hypothesis is established:

H5: E-service quality has a positive effect on customer perceived value.

H6: E-service quality has a positive influence on customer satisfaction.

The customer perceived value is seen from several aspects such as money, quality, benefits, and social psychology (Kuo et al., Citation2009; Gallarza et al., Citation2011). Where obtaining value or benefit is a substantial consumption goal to be obtained in a successful purchase transaction (Davis & Hodges, Citation2012). The value of the products offered is to satisfy customers by meeting their needs. The perceived value is the customer’s cognitive response before and after the purchase of the product. At the same time, satisfaction is a follow-up affective response after the purchase or use of the product. So that the customer perceived value is an antecedent of customer satisfaction (El-Adly, Citation2019). In the service and retail sector, the customer perceived value has been shown to have a positive impact on customer satisfaction (Cronin et al., Citation2000; Eggert & Ulaga, Citation2002; Yang & Peterson, Citation2004; Chen & Tsai, Citation2008; El-Adly & Eid, Citation2016; Slack et al., Citation2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected customer perceived value, customer value co-creation behavior, and purchasing decisions with respect to brand image and e-services quality (Graessley et al., Citation2019; Meilhan, Citation2019; Vătămănescu et al., Citation2021; Watson & Popescu, Citation2021). Value is reflected through customer consumption behaviour, so perceived value can be used to predict patronage intentions (Chen & Dubinsky, Citation2003). A study by Drugău-Constantin (Citation2019), Mirica (Citation2019), and Rydell and Kučera (Citation2021) revealed that there is a relationship between consumer preferences, cognitive attitudes, and buying habits. A repurchase is carried out if the perceived value exceeds the expected, including monetary and non-monetary costs incurred (Liu et al., Citation2009). Previous researchers have proven a correlation between customer perceived value and patronage intentions (Hsin Chang & Wang, Citation2011; Jamal & Sharifuddin, Citation2015; Rahman et al., Citation2016; Mathur & Gupta, Citation2019; Kusumawati et al., Citation2020). According to Lin (Citation2019), customer satisfaction can motivate positive behaviour towards a store. Kim (Citation2012) conceptualizes customer satisfaction as a result of expectations of previous use, while repurchase is the implication of satisfaction and benefits derived from previous use. Customers who are satisfied with previous purchases or satisfied with using a product tend to make purchases at the same store and repurchase the same product. Previous research shows similar results where customer satisfaction is directly proportional to patronage intentions (Bae et al., Citation2018; Nair, Citation2018; Hu et al., Citation2019; Deb et al., Citation2020; Kusumawati et al., Citation2020). From this study review, the researcher proposes a hypothesis:

H7: There is a positive influence of customer perceived value on customer satisfaction.

H8: Customer perceived value has a positive effect on patronage intention.

H9: Customer satisfaction has a positive effect on patronage intentions.

Shyan Fam et al. (Citation2004) revealed that religiosity influences customer attitudes and behaviour towards products or services. The level of individual religiosity will affect the customer’s judgment in receiving product information, which affects the purchasing decision-making process. Religiosity shapes customer attitudes and decisions through ethical judgments provided by customers in the context of consumption (Arli et al., Citation2020). Customers buy products that have the same characteristics as the values they believe in (Kusumawati et al., Citation2020) and are in line with their religion (Notodisurjo et al., Citation2019). Customers with high religiosity will commit to their beliefs by risk-averse behaviour, so they have a more positive attitude towards religious products (Agarwala et al., Citation2019). If the product has characteristics and benefits per one’s religiosity, a positive feeling will arise in satisfaction with the product, which increases patronage intentions. Religiosity affects the way individuals shop (Choi et al., Citation2013; Essoo & Dibb, Citation2004), where customers with high religiosity have greater patronage intentions (Jamal & Sharifuddin, Citation2015; Rahman et al., Citation2018; Deb et al., Citation2020; Kusumawati et al., Citation2020). With the correlation of the variables mentioned above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H10: Religiosity strengthens the relationship between customer perceived value and patronage intention.

H11: Religiosity strengthens the relationship between customer satisfaction and patronage intentions.

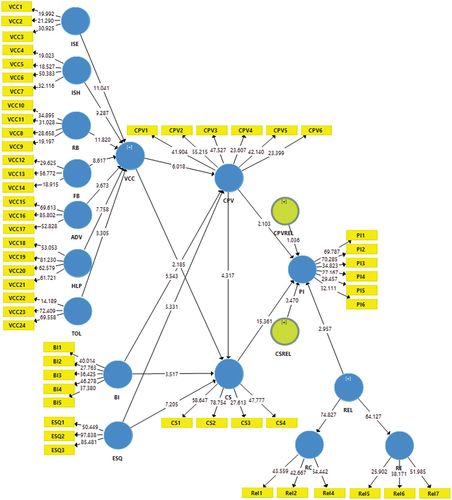

Based on the theoretical framework above, the research model can be described as shown in Figure below:

3. Methods

3.1. Data collection

Data collection in this study used a survey method by distributing online questionnaires through the Google Form application. The sample of this study was selected using a purposive sampling method on several Muslim fashion online shops with social commerce platforms that implement Value Co-creation in their business, namely Mamanda, Shafeeya, RH, Michan and Falova. The respondent’s criteria are customers who have purchased Muslim fashion products at least 2 times during the last 6 months and have participated in providing ideas or input on products to be marketed through the direct chat with the seller. Data were collected for 3 months, from May to July 2021. The sample was obtained from customers of the 5 brands spread throughout Indonesia with sociodemographic characteristics in this study, including gender, residence, age, occupation, education, and allocation of fashion spending in a month.

3.2. Measurements

In this study, measurements related to the variables studied were adopted from previous studies. The value co-creation variable is measured by 24 questions adapted from Yi and Gong (Citation2013). The brand image variable was measured using 6 questions adopted from Ansary and Nik Hashim (Citation2018). The e-service quality variable was adopted from Rita et al. (Citation2019), consisting of 3 questions. The religiosity variable was measured using 11 questions adapted from Kusumawati et al. (Citation2020). The customer perceived value variable was measured using 7 questions adapted from Kusumawati et al. (Citation2020). The customer satisfaction variable was measured using 4 questions from Kusumawati et al. (Citation2020). Finally, the variable of Patronage Intention was measured using 6 questions adapted from Kusumawati et al. (Citation2020). All items were measured employing a Likert scale with 5 scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The researcher conducted a pilot study by sending a questionnaire to 30 respondents of online Muslim fashion. Data processing and analysis using SPSS 26. Researchers tested the validity and reliability with factor analysis using SPSS. A validity test was carried out by looking at the measurement values of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA). KMO and MSA values above 0.5 indicate that the factor analysis is appropriate (Williams et al., Citation2010). Reliability test using Cronbach’s Alpha measurement. Cronbach’s Alpha value close to 1 indicates the reliability test is getting better (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2014). After analyzing the results of the pilot study, value co-creation, e-service quality, customer satisfaction, and patronage intention are all declared valid. Meanwhile, the brand image variable from 6 questions leaves 5 valid questions. The customer perceived value variable from 7 questions is 6, which is declared valid. The religiosity variable from 11 questions only 7 questions is valid. Thus the number of questions in this study amounted to 55 items. Table shows measurement items and sources.

Table 1. Measurement items and sources

3.3. Data analysis

This study is a quantitative study using the Structural Equation Model (SEM) method, with data processing and analysis using SmartPLS 3.0 software. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was chosen because this study has a second order variable with a reflective-formative relationship. In this study, the value co-creation variable with dimensions of information seeking, information sharing, responsible behavior, feedback, advocacy, helping, and tolerance is a second order construct with a reflective-formative type. The model which is complex and has hierarchical latent variable type 2, which is reflective-formative, is very suitable for using PLS-SEM (Becker et al., Citation2012). The researcher uses the (extended) repeated indicators approach to evaluate the results of high-level construction in PLS-SEM because it produces the smallest bias compared to the two-stage approach (Sarstedt et al., Citation2019).

Data analysis in PLS-SEM is carried out in 2 stages, namely the evaluation of the measurement model and the evaluation of the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2017). The first step is to analyze the measurement model to assess the validity and reliability of the constructs. In the reflective measurement model, convergent validity was tested using Loading Factor (LF), Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). According to Hair et al. (Citation2017), the threshold values are LF 0.70, CR 0.70, and AVE 0.50. Meanwhile, discriminant validity was tested using the Fornell-Larcker Criterion method by comparing the square root of the AVE of each variable with other latent variables. Discriminant validity can be accepted if the square root of AVE is higher than the correlation between other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Discriminant validity ensures that a given construct differs from the other constructs of a model (Henseler et al., Citation2015). The evaluation of the formative measurement model is carried out by looking at the size and significance of indicator weights and the indicator multicollinearity test (Hair et al., Citation2020). According to Garson (Citation2016), if the weight is not significant (p < 0.01) but has a loading factor 0.5, it can still be included in the model.

The steps in the assessment of the structural model are evaluating the collinearity of the structural model, examining the size and significance of the path coefficients, and evaluating the quality of the model based on the R-square adjusted. The multicollinearity test on the structural model uses the inner Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) with a threshold value of VIF below 3.3 (Kock, Citation2017). The bootstrap method is used to test the hypothesis based on the significance of the path coefficients. For a significance level of 5%, the T-statistic value is at least 1.96 for the hypothesis to be supported (Hair et al., Citation2017). Finally, the researcher evaluated the quality of the model based on the adjusted R-square with a substantial R-square value of 0.67 or higher (Chin, Citation1998).

4. Result

4.1. Respondent profiles

Respondents of this research are Muslim fashion customers of Mamanda, Shafeeya, RH, Michan, and Falova brands, with a total of 301 respondents. The majority of respondents were women (85.7%), 36–44 years old (48.8%), most of whom resided on the Island of Java (72.1%), with a housewife occupation (51.8%) and undergraduate education (59.5%). Most of the respondents spent < Rp 500,000 per month (55.5%) for Muslim fashion with a frequency of purchases within 6 months as much as 2x (40.2%). The sociodemographic profile of respondents has been displayed in Table .

Table 2. Sociodemographic profile of respondent (n = 301)

4.2. Measurement model

The construct validity and reliability test on the reflective measurement model were carried out based on recommendations from Hair et al. (Citation2017), where the loading factor value required in SmartPLS 3.0 is 0.70 and cronbach’s alpha is 0.60. The measurement of construct validity in this study can be accepted and declared valid because most indicators in each variable have a loading factor value above 0.70, and only the REL3 indicator has a loading factor of less than 0.70, namely 0.64 (therefore eliminated). The value of Cronbach’s alpha obtained in this study ranged from 0.702 to 0.918, which indicates is reliable.

The calculation results of Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) in this study can be said to meet the overall requirements. According to Hair et al. (Citation2017), the threshold values are CR 0.70 and AVE 0.50. Calculation results for CR and AVE for information seeking (CR = 0.834; AVE = 0.626), information sharing (CR = 0.857; AVE = 0.602), responsible behavior (CR = 0.855; AVE = 0.597), feedback (CR = 0.843; AVE = 0.643), advocacy (CR = 0.931; AVE = 0.818), helping (CR = 0.942; AVE = 0.802), tolerance (CR = 0.887; AVE = 0.725), brand image (CR = 0.917; AVE = 0.688), e-service quality (CR = 0.941; AVE = 0.841), customer perceived value (CR = 0.927; AVE = 0.681), customer satisfaction (CR = 0.922; AVE = 0.748), religiosity (CR = 0.890; AVE = 0.573), and patronage intention (CR = 0.930; AVE = 0.690). Table shows construct reliability and convergent validity. The Discriminant Validity test using the Fornell-Larcker Criterion method is declared valid because the AVE root of each latent variable is higher than the correlation with other latent variables (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The results of the discriminant validity test can be seen in Table .

Table 3. Construct Reliability and Convergent Validity

Table 4. Discriminant validity (Fornell-Larcker Criterion)

In this study, value co-creation is the second-order construct with reflective-formative type. First-order constructs were reflective, and the relationships between value co-creation dimension (first-order constructs) and value co-creation variable (second-order constructs) were formative. Therefore the measurement model was scrutinized through significance weight and multicollinearity test. The weights were significant (p < 0.01) except for VCC16, VCC19, and VCC20. According to Garson (Citation2016), if the weight is not significant but has a loading factor ≥ 0.5, it can still be included in the model. Value co-creation as a formative model is declared valid because there is no multicollinearity between indicators (VIF<5). Table shows formative measurement model evaluation.

Table 5. Formative measurement model evaluation (repeated indicator approach)

4.3. Structural model evaluation

After the measurement model test is declared valid and reliable, the structural model evaluation is carried out to test the proposed hypothesis. First, we perform a multicollinearity test to ensure no Common Method Bias (CMB) in PLS-SEM. The multicollinearity test on the structural model uses the inner Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) with a tolerance value of VIF below 3.3 (Kock, Citation2017). VIF values range from 1.701 to 3.050, so there is no problem with multicollinearity (Table ).

Table 6. Construct Collinearity Evaluation (Inner VIF)

Hypothesis testing using the bootstrap method based on the significance of the path coefficient (Figure ). For the 5% significance level, the T-statistic value should be 1.96 or higher so that the hypothesis is supported (Hair et al., Citation2017). Based on the hypothesis test, nine hypotheses (H1-H9) were supported, while two hypotheses (H10 and H11) were below the threshold of 1.96 is rejected. The results show significant positive influence of value co-creation on customer perceived value (t = 6.018, p < 0.05), value co-creation on customer satisfaction (t = 2.185, p < 0.05), brand image on customer perceived value (t = 6.543, p < 0.05), brand image on customer satisfaction (t = 3.517, p < 0.05), e-service quality on customer perceived value (t = 5.331, p < 0.05), e-service quality on customer satisfaction (t = 7.205, p < 0.05), customer perceived value on customer satisfaction (t = 4.317, p < 0.05), customer perceived value on patronage intention (t = 2.103, p < 0.05), and customer satisfaction on patronage intention (t = 15.361, p < 0.05). Meanwhile, the results showed that religiosity did not have a significant effect as a moderating relationship between customer perceived value on patronage intentions (t = 1.036, p > 0.05)and moderating the relationship between customer satisfaction on patronage intentions (t = 0.470, p > 0.05). Table shows the results of hypothesis testing.

Table 7. The results of hypothesis testing

Evaluation of model quality based on R-square adjusted. The value of R2 adjusted shows how much the independent variable can explain the dependent variable. According to Chin (Citation1998), a substantial R2 value is 0.67 or higher. Customer Perceived Value (CPV) has an R2 value of 0.672. Thus it can be interpreted that 67.2% of the variance of Customer Perceived Value (CPV) can be explained by Value Co-Creation (VCC), Brand Image (BI), and E-Service Quality (ESQ). In comparison, the remaining 32.8% can be explained by other variables not included in this study. The adjusted R2 value obtained from the customer perceived value is substantial. Similarly, 2 dependent variables shows R-square substantial: Customer Satisfaction (CS) 0.692 and patronage intention (PI) 0.736. Table shows the test of R-square.

Table 8. Test of R-Square

5. Discussion

This study explores and empirically examines the effect of value co-creation, brand image, and e-service quality on patronage intentions, with the mediation of customer perceived value and customer satisfaction moderated by religiosity. The relationship between value co-creation that positively affects customer perceived value is examined more deeply through this study. Several previous studies have shown that customer participation in the value co-creation process will make customers part of the company so that in addition to adding value to the company, it also provides benefits for customers in the form of value and experience gained during the value co-creation process (Vega-Vazquez et al., Citation2013; Chiu et al., Citation2015). The collaborativeprocess of value co-creation in the Muslim fashion industry will prompt additional value that customers will get in item quality and item details that take after customer wishes. When customers exchange information, provide ideas and input to the company, the suitability of the perceived value obtained will be better because the customer has a clear reference value regarding the Muslim fashion product created. The higher the involvement of customers in value co-creation, the higher the customer perceived value in terms of the compatibility between the quality of the product received and the price paid. The results of this study have validated that value co-creation has a positive effect on customer perceived value. This is consistent with the study conducted by Chiu et al. (Citation2019) which explains that when customers benefit from value co-creation, customers will get a higher perceived value.

This study also found a positive effect of value co-creation on customer satisfaction. When customers provide ideas and information about Muslim fashion products that match their needs and desires, satisfaction will arise in themselves when customers get these products. Satisfaction occurs because the customer is part of the creation of the product, thus creating a feeling of pride and satisfaction in the customer for using Muslim fashion products that come from their ideas. This is in line with Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer (Citation2012) statement where more customers are satisfied with the results of their value co-creation compared to customers who are dissatisfied with their creations. These findings are also supported by several previous researchers where customer participation in value co-creation positively and significantly affect customer satisfaction (Navarro et al., Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2019; Opata et al., Citation2019; Yang et al., Citation2019).

The next result found in this exploration is that brand image positively influences customer perceived value. A better brand image with its strength and uniqueness will increase the customer perceived value of Muslim fashion products. Significantly when the Muslim fashion business grows rapidly, products that only follow trends are not enough. Fashion products with unique characteristics will be more attractive to customers because they give a deep impression. This brand image plays an essential role in influencing the customer’s mindset, including assessing whether the attributes in Muslim fashion products follow the existing values in customer perceptions. Muslim fashion customers view the brand image more towards functionality or utilitarian value, not an egocentric image that can show their identity or hedonic value. According to Lien et al. (Citation2015) and Afriani et al. (Citation2019), brands with an attractive image can increase customer trust and perceptions of products that will encourage purchase intentions. The finding that brand image has a significant effect on customer perceived value contributes to corroborating several similar (Abu Elsamen, Citation2015; Kim et al., Citation2017; Huang et al., Citation2019).

The brand image also has a positive effect on customer satisfaction. Where brand image affects customer decision making through cognitive influence, if customers make purchases based on decisions based on the belief that the products purchased are of high quality and have advantages, the customers will feel satisfied. Differences in perceptions and preferences of customers towards a Muslim fashion brand will make a difference in the level of satisfaction received. Customers who see a brand as having a good image and according to their preferences will like the product. If the product received turns out to be less attractive, customer satisfaction would be reduced. These findings can provide scientific contributions and strengthen previous findings that brand image has a positive correlation with customer satisfaction (Song et al., Citation2019; Jung et al., Citation2020; Rahi et al., Citation2020).

This study also found that the e-services quality has a positive relationship with the customer perceived value. E-services play an essential role in shaping customer perceptions, especially in providing information about the product to be purchased. The better the quality of e-services owned by the online store, the more competent it will be to facilitate information search activities and purchase transactions. With the complete fulfilment of the information needed by the customer, the customer will get a better perception of the value of Muslim fashion products being marketed. This will affect customer decisions in buying Muslim fashion products online, often based on good quality e-services that can meet customer perceived product value in terms of economy, benefits, and quality. These findings follow the study conducted by Jiang et al. (Citation2016), Tsao et al. (Citation2016), and Rodríguez et al. (Citation2020) regarding the positive influence of e-service quality on customer perceived value.

The e-services quality also has a positive influence on customer satisfaction. With the e-services quality provided by e-retailers in the form of easy access for customers to obtain product information, a pleasant online shopping experience, and ease of transaction will provide a positive emotional response in the form of satisfaction in the customer. The frequency of customers visiting Muslim fashion online shops and the customer’s shopping experience while interacting online will affect the level of satisfaction obtained by customers. The level of customer satisfaction will be different from one another. According to Rita et al. (Citation2019), the online store must have a visually attractive design, easy to understand and provide relevant information about the product to provide satisfaction for customers who visit it. The results of this study strengthen empirical studies that have also been carried out by several analysts regarding the effect of e-service quality on customer satisfaction (Kundu & Datta, Citation2015; Kim, Citation2019; Zarei et al., Citation2019).

The results of this study offer a scientific contribution to the positive influence of customer perceived value on customer satisfaction. This is because providing functional value to customers in the form of benefits and good quality Muslim fashion products can lead to satisfaction in customers. Because basically, the key to customer satisfaction lies in the way marketers identify and market products that match what customers need (Karani et al., Citation2019). So retailers need to provide superior value in their products to produce customer satisfaction (Kesari & Atulkar, Citation2016). In addition, the customer perceived value is a cognitive evaluation, while customer satisfaction is a form of emotional response. The majority of cognitive evaluation precedes emotional response, this is evidenced in this study where the customer perceived value is a positive antecedent of customer satisfaction. This finding reinforces previous research on the positive impact of customer perceived value on customer satisfaction (Yang & Peterson, Citation2004; Chen & Tsai, Citation2008; El-Adly & Eid, Citation2016; Slack et al., Citation2020).

Another thing explored in this study is that the customer perceived value positively affects patronage intentions. The perceived value of each customer will be different depending on the information obtained when evaluating a product. The desire to repurchase will also be different for each individual. When Muslim fashion products have a positive value in terms of quality and benefits, customers will be willing to buy products, visit stores, and recommend products to others. Customers will tend to repurchase in the future if the customer’s perception exceeds what is expected (Liu et al., Citation2009), in addition to the convenience and trust of customers in the store (Punuindoong & Anindita, Citation2020). The findings in this study corroborate what several researchers have done in providing similar evidence, namely that there is a correlation between customer perceived value and patronage intentions (Jamal & Sharifuddin, Citation2015; Rahman et al., Citation2016; Mathur & Gupta, Citation2019; Kusumawati et al., Citation2020).

On the other hand, customer satisfaction also positively influences patronage intentions. Customers who are satisfied with previous purchases or satisfied with using a Muslim fashion product tend to repurchase at the same online store and make purchases of the same product or different products with the same brand. Even customers who are satisfied with the product’s performance, apart from buying and revisiting the store, will be willing to recommend the product to others (Elizar et al., Citation2020). Store and product attributes also influence customer satisfaction, which will affect patronage intentions (Nair, Citation2018). This study corroborates the similar results obtained by previous researchers where customer satisfaction is directly proportional to patronage intentions (Hu et al., Citation2019; Deb et al., Citation2020; Kusumawati et al., Citation2020).

In the context of religiosity as moderation, it was found that religiosity did not significantly strengthen the relationship between customer perceived value and patronage intentions. This is because Muslim fashion is no longer synonymous with fulfilling the need for clothing per Islamic law but shifting to fulfilling the need to look trendy and stylish. According to Blommaert and Varis (Citation2015), the phenomenon of “hijabistas”, or the use of Muslim fashion, has become the identity and lifestyle of Muslims by following existing fashion trends. So that religious and non-religious customers will use Muslim fashion products as part of their lifestyle.

In Indonesia, where 87% of the population is Muslim, fashion companies have designed their products according to the provisions of Islamic law. Religious customers no longer base purchasing decisions on the Shari’a provisions but the benefits and quality of Muslim fashion products. Likewise, customers who are not religious will revisit online stores to buy Muslim fashion products based on product designs that follow trends and product advantages that match their perceived value. This is in accordance with the discoveries of Kusumawati et al. (Citation2019), which observed that the level of customer religiosity did not influence patronage intention. Customers who already have a high perception of value for Muslim fashion products will continue to buy products and visit online stores without being influenced by customer religiosity.

Another result of this study shows that religiosity does not strengthen the relationship between customer satisfaction and patronage intentions. In Indonesia, the increasing number of Muslim fashion users is influenced by modern fashion and design in products, and religiosity is no longer the primary determinant of purchasing decisions for Muslim fashion products (Arifah et al., Citation2017). Modern designs that follow growing fashion trends make Muslim fashion products can be used by anyone, young or old, religious or not, and used in various events. The majority of Muslim fashion companies in Indonesia currently provide a variety of Muslim fashion choices that can facilitate customers who have different preferences.

Customers with a high level of religiosity like Muslim fashion products with simple designs, dark colours, and emphasize functionality. Meanwhile, customers with a low level of religiosity like Muslim fashion products with fashionable designs, bright colors, and various motifs that can support their appearance and follow existing trends. The availability of a choice of Muslim fashion models according to customer preferences makes customers who are satisfied with the products purchased return to visit the online store without any influence from the level of religiosity owned by the customer. This interesting finding supports previous research conducted by Farrag and Hassan (Citation2015), where religiosity does not have a significant effect on patronage intentions on Muslim fashion products.

6. Conclusion

The majority of the hypotheses developed in this study have been successfully proven, where value co-creation, brand image, and e-service quality indirectly affect patronage intentions mediated by customer perceived value and customer satisfaction. The higher the participation of Muslim fashion customers in value co-creation, the higher the customer perceived value and customer satisfaction that will encourage patronage intentions. Customers will repurchase Muslim fashion products at the same online store if the manufacturer succeeds in providing unique and different attributes to their products and improving the quality of their e-services. On the other hand, the level of patronage intention is not influenced by the level of religiosity owned by Muslim fashion customers. Meanwhile, religiosity does not have a significant effect in strengthening the relationship between customer perceived value and patronage intentions and the relationship between customer satisfaction and patronage intentions.

6.1. Theoretical implications

Value co-creation emerged as an important subject in marketing since the development of the concept of Service-Dominant Logic. Vargo and Lusch (Citation2016) develop the basic premise in value co-creation, where value is created jointly by many factors, including customers as beneficiaries of the value itself. This study enriches the marketing literature by showing how customers in online platforms actively participate during the value co-creation process by considering customer perceived value and customer satisfaction. Understanding of value co-creation through online social platforms is still limited due to changes in customer shopping behavior from visiting stores to online shopping since the COVID-19 pandemic. This research is empirical evidence of the modified Service-Dominant Logic concept where customers can offer a value proposition and engage in the value creation process (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2016). Our research delves deeper into the value co-creation that drives the development of new products in the fashion industry so as to increase customer patronage intentions. Our findings can expand the value co-creation literature, which has been mostly researched in the service sector and has not focused much on the non-service sector such as the fashion industry.

This research has vast theoretical implications. This study also increases knowledge about online patronage intentions by identifying factors that influence it such as value co-creation, brand image, and e-services quality. Holistically, these three factors play an important role in increasing customer patronage intentions through the perception of customer value and customer satisfaction which has been proven in our findings. In a previous limited study, researchers explored how the COVID-19 pandemic is changing purchasing decisions and habits including purchasing patterns related to customer cognitive attitudes (Rydell & Kučera, Citation2021; Watson & Popescu, Citation2021). This study has succeeded in identifying parameters of the quality of electronic services such as information retrieval services, transaction services, fulfillment services, and after-sales services that can affect customers’ cognitive attitudes in deciding to purchase online during this pandemic. This point confirms Xu et al. (Citation2017) statement that e-service offerings in the form of accessibility, convenience, and availability of information are sources of customer satisfaction in online shopping that affect customer buying behavior. The empirical findings in this study also show that customer satisfaction has a greater influence on online patronage intentions than customer value perceptions. According to Mitra and Jenamani (Citation2020) online brand image through strength, uniqueness, and brand preference can be used as a benchmark for customer perception. Furthermore, our findings support the use of brand image through the characteristics of fashion products that can be distinguished from other brands, have brand personality, and have benefits for customers that are proven to increase customer value perceptions.

6.2. Managerial implications

This study provides several managerial implications. First, value co-creation can be applied to the non-service sector industry, which in this study is represented by the Muslim fashion industry, where customers are involved in creating and innovating Muslim fashion products that can generate more value and benefits for customers. Companies need to provide a conducive environment to feel comfortable sharing information, ideas, and input about the products to be created. The value co-creation process must also be supported by a good information system where customers can access information regarding the types and specifications of raw materials to be used. Transparency and communication are needed during the value co-creation process to maximize the exchange of information between the company and customers regarding the Muslim fashion products that will be created. Customers’ ideas and creativity will be integrated with the company’s resources to produce Muslim fashion products with superior value. Companies that implement value co-creation will have a sustainable competitive advantage compared to companies that still use a company-centric or product-centric paradigm. The company will have more ideas regarding the design of Muslim fashion products and can strengthen marketing relationships with customers.

Second, e-services play an important role in the digital marketing era. Companies need to create applications or websites, or other types of e-services that are easily accessible to customers. So that customers can easily find information and share information that can increase customer perceptions of product value and increase customer intentions to purchase Muslim fashion products online. The information provided by the company regarding Muslim fashion products must be complete, accurate, and updated, as well as provide room for customers to give reviews of the products offered. So that customers can make purchasing decisions through the Zero Moment of Truth that customers get when interacting with e-services owned by online stores. Apart from product information, the e-services quality provides a pleasant shopping experience for Muslim fashion customers by providing aesthetic value to the website in the form of typography, placement and selection of product images, as well as providing easy-to-access menu navigation for customers. A good e-service must also be able to provide information about the stages of purchasing, the delivery process, handling problems, and returning Muslim fashion products if they are damaged during shipping.

The third managerial implication is that this research can be input for Muslim fashion designers or entrepreneurs to produce fashion products that look at trends and consider quality and benefits that can improve product image in customer perception. Because Muslim fashion customers see products from utilitarian values, product designs must have functionality that follows customers’ needs. The need for early identification of customer needs for Muslim fashion products in order to create quality products that can satisfy customers and have a better image than competitors.

6.3. Limitations and future research

This research still has several limitations that require to be improved. First, this research was conducted in the Muslim fashion industry, which does not necessarily describe the condition of the non-service industry as a whole. So that future research can be focused on different non-service industries to gain a broader insight into customer participation in value co-creation for the non-service sector. Second, this study only looks at customer participation in value co-creation without considering its antecedents. Therefore, future research can enrich this literature by adding antecedents to value co-creation. Third, this research stops at the intention of patronage, which is the ultimate goal of the study. Furthermore, the researcher recommends further research by adding the consequences of patronage intentions such as customer loyalty. Fourth, the research was conducted by involving customers without classifying the customers involved. So that future research can add moderating variables such as fashion involvement for high-involvement and low-involvement customers. In this study, religiosity was measured using measurements that were generally not specific to Islam. In the future, the Islamic religiosity measurement scale can be used if the respondents involved are Muslims. The final suggestion for further researchers is that the measurement of religiosity is not only seen from the questionnaire, which only reflects the level of individual obedience to their religion, but also looks at the preferences of Muslim fashion products that customers buy, which can reflect customer behavior towards religious products.

Acknowledgements

The authors show appreciation our respondents, to be specific online Muslim fashion customers in Indonesia who have participated in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tantri Yanuar Rahmat Syah

Tantri Yanuar Rahmat Syah is a senior lecturer and dean of the faculty of economics and business at Esa Unggul University, Indonesia. His research areas include strategic management, marketing, and management research.

Dora Olivia

Dora Olivia is the owner of an online Muslim fashion business in Indonesia that houses several brands and currently studying magister of management at Esa Unggul University, Indonesia. Her research interest is digital marketing.

References

- Abu Elsamen, A. A. (2015). Online service quality and brand equity: The mediational roles of perceived value and customer satisfaction. Journal of Internet Commerce, 14(4), 509–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2015.1109987

- Afaq, Z., Gulzar, A., & Aziz, S. (2020). The effect of atmospheric harmony on re-patronage intention among mall consumers: The mediating role of hedonic value and the moderating role of past experience. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 37(5), 547–557. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-09-2018-2847

- Afriani, R., Indradewa, R., & Syah, T. Y. R. (2019). Brand communications effect, brand images, and brand trust over loyalty brand building at PT Sanko material Indonesia. Journal of Multidisciplinary Academic, 3(3), 44–50 https://www.kemalapublisher.com/index.php/JoMA/article/view/386.

- Agarwala, R., Mishra, P., & Singh, R. (2019). Religiosity and consumer behavior: A summarizing review. Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion, 16(1), 32–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2018.1495098

- Ansary, A., & Nik Hashim, N. M. H. (2018). Brand image and equity: The mediating role of brand equity drivers and moderating effects of product type and word of mouth. Review of Managerial Science, 12(4), 969–1002. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0235-2

- Arifah, L., Sobari, N., & Usman, H. (2017). Hijab phenomenon in Indonesia: Does religiosity matter? In Competition and cooperation in economics and business (1st ed., pp. 179–186). Routledge.

- Arli, D., Septianto, F., & Chowdhury, R. M. M. I. (2020). Religious but not ethical: the effects of extrinsic religiosity, ethnocentrism and self-righteousness on consumers’ ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 171(3), 295–316 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04414-2 .

- Aruan, D. T. H., & Wirdania, I. (2020). You are what you wear: Examining the multidimensionality of religiosity and its influence on attitudes and intention to buy Muslim fashion clothing. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 24(1), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-04-2019-0069

- Aryati, T. E., & Syah, T. Y. R. (2018). The effect of service quality on patient loyalty mediated by patient satisfaction (a case study on health clinic in Indonesia). IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 20(7), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-2007010108

- Assiouras, I., Skourtis, G., Giannopoulos, A., Buhalis, D., & Koniordos, M. (2019). Value co-creation and customer citizenship behavior. Annals of Tourism Research 78 , 102742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102742

- Bae, S., Slevitch, L., & Tomas, S. (2018). The effects of restaurant attributes on satisfaction and return patronage intentions: Evidence from solo diners’ experiences in the United States. Cogent Business and Management, 5(1), 1493903. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2018.1493903

- Baker, D. A., & Crompton, J. L. (2000). Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(3), 785–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00108-5

- Baker, J., Parasuraman, A., Grewal, D., & Voss, G. B. (2002). The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. Journal of Marketing, 66(2), 120–141. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.66.2.120.18470

- Barreda, A. A., Nusair, K., Wang, Y., Okumus, F., & Bilgihan, A. (2020). The impact of social media activities on brand image and emotional attachment: A case in the travel context. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 11(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-02-2018-0016

- Bauer, H. H., Falk, T., & Hammerschmidt, M. (2006). eTransQual: A transaction process-based approach for capturing service quality in online shopping. Journal of Business Research, 59(7), 866–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.01.021

- Becker, J., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM : guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 359–394 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2012.10.001.

- Blommaert, J., & Varis, P. (2015). Culture as accent: The cultural logic of hijabistas. Semiotica, 2015(203), 153–177. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2014-0067

- Blut, M. (2016). E-Service Quality: Development of a hierarchical model. Journal of Retailing, 92(4), 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2016.09.002

- Chae, H., Kim, S., Lee, J., & Park, K. (2020). Impact of product characteristics of limited edition shoes on perceived value, brand trust, and purchase intention; focused on the scarcity message frequency. Journal of Business Research, 120 November 2020 , 398–406. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.040

- Chang, H. H., Wang, Y. H., & Yang, W. Y. (2009). The impact of e-service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty on e-marketing: Moderating effect of perceived value. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 20(4), 423–443 https://doi.org/10.1080/14783360902781923.

- Chen, Y., Cottam, E., & Lin, Z. (December 2020). The effect of resident-tourist value co-creation on residents’ well-being. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 44 September 2020 , 2019. 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.05.009

- Chen, Z., & Dubinsky, A. J. (2003). A conceptual model of perceived customer value in E-Commerce: A Preliminary Investigation. Psychology and Marketing, 20(4), 323–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10076

- Chen, C. F., & Tsai, M. H. (2008). Perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty of TV travel product shopping: Involvement as a moderator. Tourism Management, 29(6), 1166–1171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.02.019

- Chin, W. W. (1998 The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling Marcoulides, G. A.). Modern Methods for Business Research (Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates) , 295–336.

- Chiu, W., Kwag, M. S., & Bae, J. S. (2015). Customers as partial employees: The influences of satisfaction and commitment on customer citizenship behavior in fitness centers. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 15(4), 627–633. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2015.04095

- Chiu, W., Won, D., & Bae, J. S. (2019). Customer value co-creation behaviour in fitness centres: How does it influence customers’ value, satisfaction, and repatronage intention? Managing Sport and Leisure, 24(1–3), 32–44 https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2019.1579666.

- Choi, Y., Paulraj, A., & Shin, J. (2013). Religion or religiosity: which is the culprit for consumer switching behavior? Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 25(4), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2013.803901

- Cleveland, M., Laroche, M., & Hallab, R. (2013). Globalization, culture, religion, and values: Comparing consumption patterns of Lebanese Muslims and Christians. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 958–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.12.018

- Cretu, A. E., & Brodie, R. J. (2007). The influence of brand image and company reputation where manufacturers market to small firms: A customer value perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.08.013

- Cronin, J. J., Brady, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00028-2

- Davis, L., & Hodges, N. (2012). Consumer shopping value: An investigation of shopping trip value, in-store shopping value and retail format. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19(2), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.01.004

- Deb, M., Sharma, V. K., & Amawate, V. (2020). CRM, Skepticism and Patronage Intention—the mediating and moderating role of satisfaction and religiosity. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 29(4), 316–336 https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2020.1733048.

- Delener, N. (1990). The effects of religious factors on perceived risk in durable goods purchase decisions. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 7(3), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000002580

- Dewi, A. C., Syah, T. Y. R., & Kusumapradja, R. (2020). The impact of social media brand communication and word-of-mouth over brand image and brand equity. Journal of Multidisciplinary Academic, 4(5), 276–282 https://www.kemalapublisher.com/index.php/JoMA/article/view/488.

- Drugău-Constantin, A. L. (2019). Is consumer cognition reducible to neurophysiological functioning? Economics, Management, and Financial Markets, 14(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.22381/EMFM14120191

- Eggert, A., & Ulaga, W. (2002). Customer perceived value: A substitute for satisfaction in business markets? Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 17(2–3), 107–118 https://doi.org/10.1108/08858620210419754.

- Eid, R., & El-Gohary, H. (2015). The role of Islamic religiosity on the relationship between perceived value and tourist satisfaction. Tourism Management, 46 February 2015 , 477–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.003

- El-Adly, M. I. (2019). Modelling the relationship between hotel perceived value, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50 September 2019 , 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.07.007

- El-Adly, M. I., & Eid, R. (2016). An empirical study of the relationship between shopping environment, customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty in the UAE malls context. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31 July 2016 , 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.04.002

- El-Adly, M. I., & Eid, R. (2017). Dimensions of the perceived value of malls: Muslim shoppers’ perspective. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 45(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-12-2015-0188

- Elizar, C., Indrawati, R., & Syah, T. Y. R. (2020). Service quality, customer satisfaction, customer trust, and customer loyalty in the service of pediatric polyclinic (case study at private h hospital of East Jakarta, Indonesia). Journal of Multidisciplinary Academic, 4(2), 105–111 https://www.kemalapublisher.com/index.php/JoMA/article/view/442.

- Essoo, N., & Dibb, S. (2004). Religious influences on shopping behaviour: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(7–8), 683–712. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257041838728

- Farrag, D. A., & Hassan, M. (2015). The influence of religiosity on Egyptian Muslim youths’ attitude towards fashion. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 6(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-04-2014-0030

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Fuentes-Blasco, M., Moliner-Velázquez, B., & Gil-Saura, I. (2017). Analyzing heterogeneity on the value, satisfaction, word-of-mouth relationship in retailing. Management Decision, 55(7), 1558–1577. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2016-0138

- Gallarza, M. G., Gil-Saura, I., & Holbrook, M. B. (2011). The value of value: Further excursions on the meaning and role of customer value. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10(4), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.328

- Garson, G. D. (2016). Partial Least squares: regression and structural equation models. Statistical Associates Publishers.

- Gensler, S., Völckner, F., Egger, M., Fischbach, K., & Schoder, D. (2015). Listen to your customers: Insights into brand image using online consumer-generated product reviews. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 20(1), 112–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10864415.2016.1061792

- González-Mansilla, Ó., Berenguer-Contrí, G., & Serra-Cantallops, A. (2019). The impact of value co-creation on hotel brand equity and customer satisfaction. Tourism Management, 75 December 2019 , 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.04.024

- Gounaris, S., Dimitriadis, S., & Stathakopoulos, V. (2010). An examination of the effects of service quality and satisfaction on customers’ behavioral intentions in e-shopping. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(2), 142–156 https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041011031118.

- Graessley, S., Horák, J., Kováčová, M., Valášková, K., & Poliak, M. (2019). Consumer attitudes and behaviors in the technology-driven sharing economy: motivations for participating in collaborative consumption. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 7(1), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.22381/JSME7120194

- Grissemann, U. S., & Stokburger-Sauer, N. E. (2012). Customer co-creation of travel services: The role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1483–1492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.002

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. 2014. Multivariate Data Analysis. Pearson New International Edition, 7th. Pearson Education Limited 89–149.

- Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109(August 2019), 101–110 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hofmann, J., Schnittka, O., Johnen, M., & Kottemann, P. (2019). Talent or popularity: What drives market value and brand image for human brands? Journal of Business Research, 124 January 2021 , 748–758 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.045.

- Hsieh, M., Pan, S., & Setiono, R. (2004). Product-, corporate-, and country-image dimensions and purchase behavior: A multicountry analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070304264262

- Hsin Chang, H., & Wang, H. W. (2011). The moderating effect of customer perceived value on online shopping behaviour. Online Information Review, 35 3 333–359 . https://doi.org/10.1108/1468452111115141

- Hu, H. H., Kandampully, J., & Juwaheer, D. D. (2009). Relationships and impacts of service quality, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and image: An empirical study. Service Industries Journal, 29(2), 111–125 https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060802292932.