Abstract

Abstract: Verbal abuse during childbirth constitutes a violation of women’s human rights and indicates poor maternal health care. The aim of the study was to investigate experiences and drivers of verbal abuse among women in Ndola and Kitwe health facilities. The study adopted a cross-sectional survey. Qualitative and quantitative data using questionnaires and focus group interviews were employed. The study was done in the Ndola and Kitwe districts of Zambia. The target population were women attending postnatal services who had a live birth within 28 days of delivery. Twenty clinics were randomly selected and a total of 306 women were recruited using convenient sampling. Eleven percent of the study population experienced verbal abuse during intrapartum care. A 1-year increase in age reduced the odds of experiencing verbal abuse (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] 0.89, 95% CI: 0.80–0.99). Women who consumed alcohol more frequently experienced verbal abuse than women who never consumed alcohol (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 5.91, 99% CI 2.12–16.51), and women with bleached skin color more often experienced verbal abuse than women with natural skin tone (AOR = 3.95, 95% CI 1.13–13.83). Further, women with a medium skin tone were less likely (AOR = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.03–0.84) to experience verbal abuse. Other key drivers of verbal abuse include language barriers, laziness, vomiting, lack of seriousness, crying, lack of cooperation, and moving around during labour. We conclude that women experience various forms of verbal abuse. Therefore, there is a need to implement interventions that tackle the multiplicity of factors that drive verbal abuse at the individual, structural, and policy level. Further, there is a need to enhance training in respectful maternity care among service providers.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Respectful maternal care (RMC) is pivotal to improving birth and maternal outcomes of women globally. In the recent past, the government of Zambia through the ministry of health rolled out strategies to improve the number of women delivering at health facilities in an effort to reduce maternal and infant mortality rates which now stand at 183 deaths per 100,000 live births and 43.107 deaths per 1000 live births, respectively. However, recent evidence in Zambia suggests that health-care workers habitually fail to provide respectful maternal care in most birthing facilities. In this regard, verbal abuse has been found to be the most prevalent form of disrespect and abuse among women during labour and delivery in Zambia. However, it is important to note that respectful maternal care is a universal right of each woman and hence mistreating women during labour and delivery is a breach of this right. It was against this background that the researchers explored and examined the drivers of verbal abuse among women during labour and delivery.

1. Introduction

Respectful maternal care (RMC) has emerged as a vital strategy in improving the maternal care of women during labour and delivery. This is in line with global concerted efforts to reduce maternal and infant mortality rates and increase universal access to reproductive and maternal health services among women (Amole et al., Citation2019). RMC is a universal right of each woman regardless of their gender, socio-economic status, and education level, hence mistreatment of women during childbirth through disrespect and abuse is a breach of this important right (Dwekat et al., Citation2020).

Enhanced quality interaction between women and their health-care providers is central to the promotion of RMC and has been known to contribute to positive outcomes of childbirth (Moridi et al., Citation2020). This entails preserving women’s respect and providing essential information and emotional maternal services during labor and childbirth (WHO, Citation2017). Ishola and colleagues have defined RMC as a universal human right that encompasses the principles of ethics and respect for women’s feelings, dignity, choices, and preferences during labour and delivery (Ishola et al., Citation2017). RMC also requires the adoption of safe and respectful care practices, health maintenance for all, regardless of the socioeconomic status and preservation and support of the physiological process that unfolds during pregnancy and birth (Morton & Simkin, Citation2019). While universal access to maternal health care is central to primary health care, recognition of the unique needs and preferences of women and their newborns remains key in ensuring RMC (Moridi et al., Citation2020). However, despite the global recognition of RMC as one of the key strategies in reducing maternal and infant mortality rates, there is still a global concern regarding the high prevalence of disrespect and abuse (D&A) among birthing women during delivery and labour (Hajizadeh et al., Citation2020; Lukasse et al., Citation2015).

Further, evidence in Africa has revealed considerable reports of maternal abuse and disrespect with reports of about 23.7–98% of women reporting at least one form of maternal abuse (Orpin et al., Citation2018). For instance, in Zambia, a previous study among women during labour reported women experiencing verbal abuse and being abandoned during the labour process, thereby deterring some from delivering in health facilities during subsequent pregnancies (Sialubanje et al., Citation2015; Smith et al., Citation2020). In Tanzania, women also reported verbal abuse, discriminatory treatment, and being ignored after being interviewed about their post-childbirth experiences (McMahon et al., Citation2014). Other forms of maternal abuse include physical abuse (such as being slapped by health-care providers), abandonment to deliver a child alone, and being detained for a long time in a health facility (Chadwick et al., Citation2014; Kruk et al., Citation2018; McMahon et al., Citation2014; Orpin et al., Citation2018). In their 2010 landscape analysis, Bowser and Hill described these forms of abuse and disrespect under seven categories, which include: physical abuse, non-consensual care, non-confidential care, undignified care, discrimination, abandonment of care, and detention in health facilities (Nawab et al., Citation2019).

The most common form of disrespect and abuse in most low- and middle-income countries is verbal abuse. For instance, in a Lancet study by Bohren and colleagues, 41.6% (n = 838) of women reported that they had experienced various forms of verbal abuse such as being shouted at and use of strong language during labor observations (Bohren et al., Citation2019). Studies have highlighted a link between verbal abuse and socio-economic factors (Bohren et al., Citation2019; Nawab et al., Citation2019). Age and education level and socio-economic status have been known to be significantly associated with verbal abuse among women during labor and delivery (Bohren et al., Citation2019). Similarly, women who are younger and less educated have a higher risk of experiencing verbal and physical abuse than those who are more educated. These highlight an array of inequalities in how women are treated during childbirth. Maya and colleagues found similar results in a qualitative study on women’s perspective of mistreatment during childbirth at the health facilities in Ghana such as the use of derogatory words, scolding, and use of sarcastic words by health-care providers (Maya et al., Citation2018). Despite evidence of verbal abuse in most facilities, there is a paucity of studies that have highlighted the drivers of verbal abuse among women in most birthing facilities globally (Oluoch-Aridi et al., Citation2018). Previous studies have revealed that scolding is the most prevalent form of verbal abuse, especially among women of lower socioeconomic status; in most cases, women are usually scolded about how they enjoy sexual intercourse but fail to push during labour and delivery (Jewkes & Penn-Kekana, Citation2015; Okafor et al., Citation2015; Zacher Dixon, Citation2015). Invariably, verbal abuse is a consequence of an unbalanced relationship between health-care providers and birthing women which is driven by the socioeconomic status of women and institutional norms that normalise mistreatment acts by health-care workers. It is also intertwined with discriminatory practices which are based on age, parity, socio-economic status, and ethnicity (Perry et al., Citation2013). The consequences of lack of respectful maternity care in birth settings are dire; firstly, lack of RMC creates an environment that is devoid of support and respect for birthing mothers (Rosen et al., Citation2015). Also, women who experience verbal abuse are more likely to seek maternal care elsewhere rather than in hospital-based facilities, a situation which poses a greater risk of maternal and infant death and is, therefore, a threat to global concerted efforts which are aimed at reducing maternal, neonatal, and child mortality rates (Sethi et al., Citation2017).

In the past decade, Zambia has been striving to improve maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) indicators by ensuring universal access to family planning, antenatal services, skilled attendance at birth, and basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care (MOH, Citation2011). Despite a substantial increase in facility-based childbirth (MOH, Citation2017), evidence suggests that maternal health providers habitually fail to provide RMC in most facilities which have consequently contributed to a rise in poor birth outcomes as well as infant and maternal mortality rates in the country (Smith et al., Citation2020). Further, various forms of disrespect and abuse such as abandonment, detention in health facilities, physical abuse such as slapping, verbal abuse, and assertive power are prevalent in Zambia which has caused some women not to deliver in health facilities in their subsequent pregnancies (Tato Nyirenda et al., Citation2018). The most prevalent of all forms of disrespect and abuse is verbal abuse (Smith et al., Citation2020), which constitutes scolding, use of derogative language, use of assertive power, and being shouted at. Therefore, exploring the experiences of women during labour and delivery and examining the drivers of verbal abuse may provide baseline information which is essential in devising interventions aimed at improving the maternal outcomes in birthing facilities (Oluoch-Aridi et al., Citation2018). Despite evidence suggesting verbal abuse of women in Zambia, little is known about the experiences and drivers of verbal abuse among birthing women in Zambia. Understanding the experiences and drivers of verbal abuse during labour and delivery among women may aid in the formulation of appropriate strategies that address underlying factors that contribute to an increase in verbal abuse among health-care providers. This study was aimed at investigating the experiences and drivers of verbal abuse among women during labour and delivery in Ndola and Kitwe districts of Zambia.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and sampling

A cross-sectional study which utilized both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods was employed. The study was conducted in the Copperbelt Province of Zambia specifically in Ndola and Kitwe districts. The target population for the study were women attending postnatal services and had a live birth within 28 days of delivery. A two (2) stage sampling technique was used. First, a random sample of 20 clinics in Ndola and Kitwe was selected from a list of all health facilities that conduct deliveries and postnatal services. A total of 306 women with a neonate were conveniently selected and included in the sample as they came for postnatal care.

2.2. Data collection

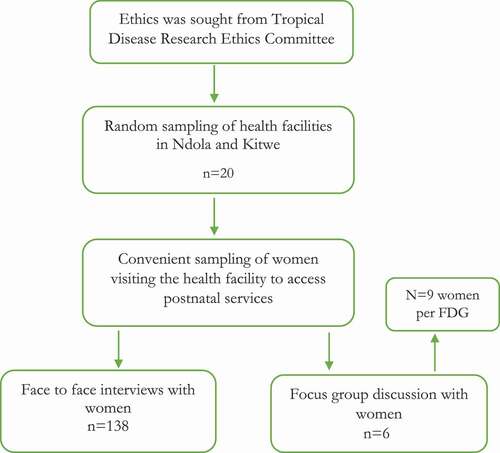

The assessment conducted face-to-face interviews with women after accessing postnatal care. The assessment used a structured interview questionnaire on performance Standards for Respectful Maternity Care developed by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (USAID & MCHIP, 2011) and was pre-coded and programmed on the Open Data Kit (ODK) software for data collection and hard copy questionnaires were used only for back-up. The questionnaire had closed (quantitative)-ended questions. Health facility focus group interviews were conducted with mothers who had a live birth within 28 days of delivery during or after receiving postnatal service from the sampled health facilities. Focus group interviews were conducted to explore the experiences of women on verbal abuse. Skin tone was measured using the Munsell color charts. At least two trained rater independently checked and assessed the skin color on the forearm midway between wrist and elbow. The flow of the selection and data collection is shown in .

2.3. Flow chart

2.4. Data analysis

Quantitative data were pre-coded and entered on the Open Data Kit (ODK). The quantitative data was thus analyzed using Stata version 13. Univariate and bivariate analysis were conducted to provide descriptive statistics. A chi-square analysis was performed to assess associations between independent and dependent variables. Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with verbal abuse. We first conducted univariable analysis and then run a multivariable model. We ran multivariable model with factors associated with verbal abuse with P ≤ 0.10 in univariable analysis. We adjusted for age as a continuous variable (1-year increase in age). We considered P value ≤0.05 as statistically significant.

2.5. Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was sought and granted by the Tropical Disease Research Center to conduct the study. Approval to conduct the study was granted by the National Health Research Authority. Permission to visit health facilities was sought from Ministry of Health. All research assistants underwent extensive training to equip them with knowledge, skills, and the ethics to uphold during the assessment. All participants were informed about the assessment through a comprehensive information participant’s sheet that was read to the participants. Participants were informed about the objectives of the study and that participation in the assessment was voluntary. Participants were at liberty not to answer questions they did not wish to and could withdraw from the study at any time if they so wished. Participants were assured that the information they provided was confidential and that none of their names would be collected. Participants did not receive any financial or other material benefits for participating in the assessment. Consent to take part in the study was only sought after informing potential participants about all facets of the study and all questions about the study were addressed. For adolescent women below the legal age (below 18 years), consent was sought from parents/guardians/caregivers/spouse before assent was sought from potential participants. Therefore, participants who consented and assented to take part in the study were required to sign or thumb print the consent forms.

3. Results

3.1. Background characteristics of participants

presents background findings of participants in Ndola and Kitwe districts of the Copperbelt. A third (32.7%) of the participants were aged 20–24, 26.4% were aged 25–29 and 14.4% were aged 15–19. The majority (84.3%) of the respondents were married and two-thirds (66.6%) had attained secondary education. More than half (59.8%) of the respondents were not working (housewife) and 1 in 10 were in formal employment. The results further show that over three-quarters (83.3%) of the respondents were from a high-density area, two-thirds (63.1%) were protestants, over half (51%) had a dark brown skin tone and 90.2%of the respondents had a natural skin tone. Nearly all (99%) respondents were nonsmokers, and over three-quarters (81%) did not drink alcohol.

Table 1. Participant’s characteristics/profile by districts

Table 2. Determinants of verbal abuse among women

3.2. Women’s experiences and drivers of verbal abuse from service providers

The study reveals that 11% of women experienced verbal abuse during intrapartum care. The participants had different experiences of verbal abuse during their encounters with service providers. The participants indicated they were verbally abused as they were scolded, shouted at and told hurtful words as well as displeasing statements and remarks. The verbal abuse was as a result of perceived actions such as language barrier, laziness, vomiting, and lack of seriousness, crying and moving around during labour. Emerged themes from focus group discussions that signified verbal abuse among women include: use of derogative words by providers, women being shouted at, women being belittled and mocked, being scolded and insulted. Below are some of the excerpts from focus group discussions and interviews at Ndola and Kitwe Health facilities

“I was told to be serious and not be stupid”. (Participants 1, FGI 1, Ndola)

“I was told that I was acting crazy, as if I had never given birth before”(Participant 2, FGI 1, Ndola)

“When being called the provider would say I was lying about the pain I was going through. I was called a liar and pretender”. (Participant 3, FGI 2, Kitwe)

“He was shouting that he was going to leave anyone misbehaving because they were not his relatives”.(Participant 3, FGI 2, Kitwe)

“I was told not to sit on the chair because I was going to put blood and mess on the sit, so I just stood and didn’t have anywhere to sit” (Participant 5, FGI 1, Ndola)

“No, she said I shouldn’t touch her because I was going to give her rash when she was stitching me after labor” (Participant 6, FGI 1, Ndola)

“Constantly shouting telling me that I should be serious during delivery and that was a fool” (Participant 7)

“I was being denied water to drink because I could accuse the nurse of poisoning me, but I was feeling thirsty” (Participant 8, FGI 1, Kitwe)

“Scolded at me because I vomited on the floor” (Participant 9, FGI 2, Kitwe)

“I was told to be serious and not be stupid”. (Participants 10, FGI 2, Kitwe)

“The nurse Insulted me because I was not able to communicate in local language (Bemba)(Participant 11, FGI 1, Ndola)

“I was scolded because I was in pain and crying. I was told harshly to stop crying” (Participant 12, FGI 1, Ndola)

“I was shouted at for asking and insisting to go to the toilet. I was told to defecate just where I was” (Participant 13, FGI 1, Kitwe)

3.3. Determinants of verbal abuse among women

A chi-square (chi2) analysis was conducted to assess whether socioeconomic and demographic characteristics are associated with verbal abuse. Findings show a statistical significant association between women’s age (p = 0.038), religion (p = 0.017), status of the skin tone (p = 0.025), drinking alcohol status (p = 0.002), and verbal abuse.

A multivariate logistic regression was conducted to assess the determinants of verbal abuse after controlling for other socioeconomics and demographic factors. A 1-year increase in age reduced the odds (AOR 0.89, 95% CI: 0.80–0.99) of experiencing verbal abuse after controlling for other socio-economic and demographic factors. Women with a medium skin tone were less likely (AOR = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.03–0.84) to experience verbal abuse compared to women with a dark skin tone after controlling for other socio-economic and demographic factors.

Women who consumed alcohol more frequently experienced verbal abuse than women who never consumed alcohol (AOR = 5.91, 99% CI 2.12–16.51), while women with bleached skin color more often experienced verbal abuse than women with natural skin tone (AOR = 3.95, 95% CI 1.13–13.83). We used the Pearson goodness-of-fit test or the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. The results show Hosmer-Lemeshow chi2 (8) of 11.37 and the Probability > chi2 of 0.1817. Therefore, because the test is not significant, we are satisfied with the fit of our model.

4. Discussion

Findings of the study revealed that 11% of women experienced verbal abuse during intrapartum care. This is lower than findings in a previous study done in India among females of urban slums in which more than half of females (54.7%) reported having experienced mistreatment during delivery, with verbal abuse being the most common (28.6%) form of mistreatment (Sudhinaraset et al., Citation2016). Similarly, other studies have reported a high prevalence of verbal abuse in maternal settings (Bohren et al., Citation2015; Jewkes & Penn-Kekana, Citation2015; Miller et al., Citation2016). The observed differences in prevalence could be due to inherent differences in institutional and system values, which dictate the nature and type of practices held by health care providers (Nawab et al., Citation2019), with some institutions normalizing verbal abuse and regarding it as essential in helping women to push during delivery (Sando et al., Citation2016). We identified various forms of verbal abuse which include; scolding, being shouted at, use of strong language, and mocking of women for falling pregnant. Similar results were found in a qualitative study done in Kenya which revealed scolding, derogative words, women being silenced when they ask about their care, provider’s assertive powers by using sarcastic words. Arguably, these patterns are most prevalent in low-income countries with poor health systems and high levels of social inequalities, which signify the obvious influence of the health system values and socio-economic factors on the behavioral outcome of health care workers (Oluoch-Aridi et al., Citation2018).In this regard, some institutions have normalized the mistreatment of women during labour and regard it as a potent strategy in helping women push during labour. The statistically significant relationship between socio-demographic factors such as age, religion, the status of the skin tone, and drinking alcohol status has been documented in most settings globally (Bohren et al., Citation2019; Oluoch-Aridi et al., Citation2018). Similarly, in our study, age (p = 0.038), religion (p = 0.017), the status of the skin tone (p = 0.025), and drinking alcohol status (p = 0.002), were all significantly associated with verbal abuse among women. Conversely, Okafor et al, and Diamond-Smith et al, found no association between verbal abuse and age, religion, education, and parity (Diamond-Smith et al., Citation2017; Okafor et al., Citation2015). Similarly, in our study, we found no statistically significant association between education level and verbal abuse. Inherent differences in the quality and nature of institutional setup which usually dictate the behavioral outcome of health workers could explain the observed differences. Further, demographic factors and place of residence would also explain the observed difference in the association between education and verbal abuse among women. As above, socio-economic status is a major influence on access to quality health care in most countries. Likewise, this influences the quality of care women receive during labour and delivery. In our study, we found a statistically significant association between socio-economic status and verbal abuse, with women of low socio-economic status more likely to be verbally abused during labour and delivery compared to women with a high socio-economic status (Nawab et al., Citation2019; Oluoch-Aridi et al., Citation2018). This could be because women with lower socio-economic status are less likely to report any form of mistreatment or even reply when being scolded or shouted at. And as noted by Diamond-Smith and others, birthing women with higher socio-economic status may have more expectations from the facility and are more aware of their needs and any behavior meted out to them (Diamond-Smith et al., Citation2017). In commensurate with these findings, a study by Afulani and others reported that providers with higher socio-economic status are more likely to be conscious of their actions when they meet someone who challenges their social standing, leading to more respectful treatment of women of higher socio-economic status (Afulani et al., Citation2020). However, verbal abuse may also be driven by policy and structural factors. For instance, in their framework, Freedman and kruk, postulate that drivers of mistreatment of birthing women by providers may be expressed at the individual, structural and policy level. At the individual level, verbal abuse can be due to the need for healthcare workers to promote abusive behavior as a way of asserting control of the women during labor and delivery. At the structural level, health facilities may promote a culture that normalize mistreatment and abusive actions as strategies to manage birthing women during labour and delivery, verbal abuse may also be due to burnout among healthcare providers, who may be overworked due to shortages of the workforce (Bohren et al., Citation2014; Bradley et al., Citation2016). At the policy level, factors such as poor enumerations and other conditions of services and provision of free maternal services have been known to contribute to abusive behavior among health care providers (Freedman & Kruk, Citation2014). Paralleling this, a recent study in Palestine has shown that verbal abuse could be due to limitations of resources and staff in childbirth facilities (Dwekat et al., Citation2020).

In our study, discriminatory practices among health-care providers were influenced by the age of a woman, older women were less likely to be verbally abused during labour and delivery as compared to younger women (AOR = 0.13, CI = 0.01–1.33). In most settings, young women usually suffer stigma and judgment due to conservative cultural values and are usually denied access to essential reproductive and sexual health services by health-care providers (Mbeba et al., Citation2012). Also, we found a statistically significant association between place of residence and verbal abuse during labour and delivery. Birthing women from medium dense areas were less likely (AOR = 0.21, CI = 0.04–1.03) to experience verbal abuse compared to women from low-density areas. Inherent differences in socioeconomic status could play a huge role in the link between residence and verbal abuse. Thus, women from medium residential areas are more likely to be vested with information about their reproductive and sexual health rights compared to women from low medium density; hence, they are more likely to be aware of their reproductive and sexual health rights and could easily report any form of abuse meted to them (Oluoch-Aridi et al., Citation2018). As a demographic factor, the status of skin tone was significantly associated with verbal abuse. Women with bleached skin color were four times more likely (AOR = 4.2, CI = 1.28–13.73) to experience verbal abuse. Women with bleached skin face stigma and judgment in most societies. Skin bleaching has also been associated with people of the lower socioeconomic class (Benn et al., Citation2019). As noted by Afulani and others, implicit bias plays a role in the disparities regarding the status of the skin tone (Afulani et al., Citation2020). Health-care provider’s actions are therefore influenced by women’s skin tone, these biases could be a usual reflection of broader societal norms and behaviors shaped by cultural values and norms (Filby et al., Citation2016). Further, alcohol drinking status also influenced how women were treated during labor and delivery. Women that indicated not taking alcohol were less likely (AOR = 0.21, CI = 0.08–0.53) to experience verbal abuse compared to women that drink alcohol after controlling for other factors. Other key drivers of verbal abuse identified through thick description during focus group interviews include: perceived actions such as language barrier, laziness, vomiting, lack of seriousness, crying, and moving around during labour.

5. Limitations

Self-reporting of abuse made it difficult to identify underreporting and exaggerations considering the sensitivity of the subject of mistreatment. This could subject our study to Hawthorne effect. Due to the moderately smaller sample size; the power of the study could not be enhanced. However, sampling from a wide geographical locations might ensure a more representative sample suitable for inferring. FGIs also enabled thick and rich data description because participants were able to openly share their experiences (Cresswell et al., Citation2016). Further, there was less chance of recall bias considering the fact that interviews were conducted within 28 days post-delivery.

6. Conclusion

Our findings suggest that verbal abuse is prevalent among women during labuor and delivery in most health facilities in Kitwe and Ndola districts. Key drivers of verbal abuse identified include: age of a woman, residence, alcohol drinking status, residential place and status of the skin tone. Other key drivers of verbal abuse were as a result of perceived actions such as language barrier, laziness, vomiting, lack of seriousness, crying and moving around during labour. Therefore, interventions that tackle the multiplicity of factors that drive verbal abuse need to be implemented. Institutional structural changes are needed that can motivate workers and prevent burnout among health-care providers. Further, providers should be empowered with skills to be able to manage difficult situations and their biases.

Authors’ contributions

The authors in this paper were responsible for all the aspects of the study. The authors read, reviewed and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Availability of data and materials

The data is readily available upon request and meets the requirements from Amref Health Africa Zambia.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Amref Health Africa for the support rendered during the assessment. We also wish to thank all the participants who took time to voluntarily take part in the assessment.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bright Mukanga

Bright Mukanga is a lecturer and researcher at the Copperbelt University, Department of Public Health, Michael Chilufya Sata School of Medicine in Ndola, Zambia. He is a PhD Fellow in Global Health at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa. He also holds a Master’s Degree in Public Health from the University of Sheffield in the UK, Master’s Degree in Climate Change with the focus on climate change influence on the epidemiology of infections and non-infectious diseases, Postgraduate Diploma in Health Promotion and, a BSc in Medical Radiology. He is currently engaged in teaching Public Health and Health Promotion at undergraduate and postgraduate level, research supervision in the said areas and levels and community engagement, among others. His major research areas include adolescent sexual and reproductive health, maternal and child health, socio-cultural determinants of HIV/AIDS transmission, influence of climate change on the epidemiology of infectious and non-infectious diseases and epidemiology of infectious and non-infectious diseases.

References

- Afulani, P. A., Afulani, P. A., Buback, L., Kelly, A. M., Kirumbi, L., Cohen, C. R., Cohen, C. R., & Lyndon, A. (2020). Providers’ perceptions of communication and women’s autonomy during childbirth: A mixed methods study in Kenya (Vol. 17, pp. 85). Reproductive Health. BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-0909-0

- Amole, T., Tukur, M., Farouk, S., & Ashimi, A. (2019). Disrespect and abuse during facility based childbirth: The experience of mothers in Kano, Northern Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 36(1), 21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4103/tjog.tjog_77_18

- Benn, E. K. T., Deshpande, R., Dotson-Newman, O., Gordon, S., Scott, M., Amarasiriwardena, C., Khan, I. A., Wang, Y.-H., Alexis, A., Kaufman, B., Moran, H., Wen, C., Charles, C. A. D., Younger, N. O. M., Mohamed, N., & Liu, B. (2019, June 1). Skin bleaching among African and Afro-Caribbean women in New York City: Primary findings from a P30 pilot study. Dermatology and Therapy, 9(2), 355–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-019-0297-y

- Bohren, M. A., Hunter, E. C., Munthe-Kaas, H. M., Souza, J. P., Vogel, J. P., & Gülmezoglu, A. M. (2014). Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low- and middle-income countries: A qualitative evidence synthesis (Vol. 11, pp. 71). Reproductive Health. BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-11-71

- Bohren, M. A., Mehrtash, H., Fawole, B., Maung, T. M., Balde, M. D., Maya, E., Thwin, S. S., Aderoba, A. K., Vogel, J. P., Irinyenikan, T. A., Adeyanju, A. O., Mon, N. O., Adu-Bonsaffoh, K., Landoulsi, S., Guure, C., Adanu, R., Diallo, B. A., Gülmezoglu, A. M., Soumah, A. M., Sall, A. O., & Tunçalp, Ö. (2019, November 9). How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: A cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys. The Lancet, 394(10210), 1750–1763. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31992-0

- Bohren, M. A., Vogel, J. P., Hunter, E. C., Lutsiv, O., Makh, S. K., Souza, J. P., Aguiar, C., Saraiva Coneglian, F., Diniz, A. L. A., Tunçalp, Ö., Javadi, D., Oladapo, O. T., Khosla, R., Hindin, M. J., Gülmezoglu, A. M., & Jewkes, R. (2015, June 30). The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. Jewkes R, editor. PLOS Medicine, 12(6), e1001847. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847

- Bradley, S., McCourt, C., Rayment, J., & Parmar, D. (2016). Disrespectful intrapartum care during facility-based delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis of women’s perceptions and experiences (Vol. 169, pp. 157–170). Social Science and Medicine. Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.039

- Chadwick, R. J., Cooper, D., & Harries, J. (2014). Narratives of distress about birth in South African public maternity settings: A qualitative study. Midwifery, 30(7), 862–868. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.12.014

- Cresswell, J. A., Schroeder, R., Dennis, M., Owolabi, O., Vwalika, B., Musheke, M., Campbell, O., & Filippi, V. (2016, March 1). Women’s knowledge and attitudes surrounding abortion in Zambia: A cross-sectional survey across three provinces. BMJ Open, 6(3), e010076. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010076

- Diamond-Smith, N., Treleaven, E., Murthy, N., & Sudhinaraset, M. (2017, November 8). Women’s empowerment and experiences of mistreatment during childbirth in facilities in Lucknow, India: Results from a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(S2), 335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1501-7

- Dwekat, I. M. M., Tengku Ismail, T. A., Ibrahim, M. I., & Ghrayeb, F. (2020). Exploring factors contributing to mistreatment of women during childbirth in West Bank, Palestine. Women and Birth. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.07.004

- Filby, A., McConville, F., Portela, A., & Kumar, S. (2016, May 2). What prevents quality midwifery care? A systematic mapping of barriers in low and middle income countries from the provider perspective. Kumar S, editor. PLoS One, 11(5), e0153391. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153391

- Freedman, L. P., & Kruk, M. E. (2014). Disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth: Challenging the global quality and accountability agendas. The Lancet, 384(9948), e42–4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60859-X

- Hajizadeh, K., Vaezi, M., Meedya, S., Mohammad Alizadeh Charandabi, S., & Mirghafourvand, M. (2020, January 20). Respectful maternity care and its related factors in maternal units of public and private hospitals in Tabriz: A sequential explanatory mixed method study protocol. Reproductive Health, 17(1), 9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-0863-x

- Ishola, F., Owolabi, O., Filippi, V., & Fernandez-Reyes, D. (2017, March 21). Disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth in Nigeria: A systematic review. Fernandez-Reyes D, editor. PLoS One, 12(3), e0174084. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174084

- Jewkes, R., & Penn-Kekana, L. (2015, June 1). Mistreatment of women in childbirth: Time for action on this important dimension of violence against women. PLOS Medicine, 12(6), 1001849. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0643-z

- Kruk, M. E., Kujawski, S., Mbaruku, G., Ramsey, K., Moyo, W., & Freedman, L. P. (2018, January 1). Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: A facility and community survey. Health Policy and Planning, 33(1), e26–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czu079

- Lukasse, M., Schroll, A.-M., Karro, H., Schei, B., Steingrimsdottir, T., Van Parys, A.-S., Ryding, E. L., & Tabor, A. (2015, May 1). Prevalence of experienced abuse in healthcare and associated obstetric characteristics in six European countries. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 94(5), 508–517. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12593

- Maya, E. T., Adu-Bonsaffoh, K., Dako-Gyeke, P., Badzi, C., Vogel, J. P., Bohren, M. A., & Adanu, R. (2018, August 27). Women’s perspectives of mistreatment during childbirth at health facilities in Ghana: Findings from a qualitative study. Reproductive Health Matters, 26(53), 70–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1502020

- Mbeba, R. M., Mkuye, M. S., Magembe, G. E., Yotham, W. L., Mellah, A. O., & Mkuwa, S. B. (2012). Barriers to sexual reproductive health services and rights among young people in Mtwara district, Tanzania: A qualitative study. The Pan African Medical Journal, 13(Suppl 1), 13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.supp.2012.13.1.2085

- McMahon, S. A., George, A. S., Chebet, J. J., Mosha, I. H., Mpembeni, R. N. M., & Winch, P. J. (2014, August 12). Experiences of and responses to disrespectful maternity care and abuse during childbirth; a qualitative study with women and men in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1), 268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-268

- Miller, S., Abalos, E., Chamillard, M., Ciapponi, A., Colaci, D., Comandé, D., Diaz, V., Geller, S., Hanson, C., Langer, A., Manuelli, V., Millar, K., Morhason-Bello, I., Castro, C. P., Pileggi, V. N., Robinson, N., Skaer, M., Souza, J. P., Vogel, J. P., & Althabe, F. (2016). Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: A pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide (Vol. 388, pp. 2176–2192). The Lancet. Lancet Publishing Group. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31472-6

- MOH. The Zambia national strategic plan (2011-2015). 2011 [ cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.zm/?wpfb_dl=68

- MOH. The Zambia national strategic plan (2017-2021). 2017 [ cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.zm/?wpfb_dl=68

- Moridi, M., Pazandeh, F., Hajian, S., Potrata, B., & Gurgel, R. Q. (2020, March 9). Midwives’ perspectives of respectful maternity care during childbirth: A qualitative study. Gurgel RQ, editor. PLoS One, 15(3), e0229941. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229941

- Morton, C. H., & Simkin, P. (2019). Can respectful maternity care save and improve lives? (Vol. 46, Birth, 391–395). Blackwell Publishing Inc.. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12444

- Nawab, T., Erum, U., Amir, A., Khalique, N., Ansari, M., & Chauhan, A. (2019). Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth and its sociodemographic determinants – A barrier to healthcare utilization in rural population. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(1), 239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_247_18

- Okafor, I. I., Ugwu, E. O., & Obi, S. N. (2015). Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in a low-income country. In International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics (pp. 110–113). Elsevier Ireland Ltd.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.08.015

- Oluoch-Aridi, J., Smith-Oka, V., Milan, E., & Dowd, R. (2018, December 17). Exploring mistreatment of women during childbirth in a peri-urban setting in Kenya: Experiences and perceptions of women and healthcare providers. Reproductive Health, 15(1), 209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0643-z

- Orpin, J., Puthussery, S., Davidson, R., & Burden, B. (2018, June 7). Women’s experiences of disrespect and abuse in maternity care facilities in Benue State, Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1847-5

- Perry, B. L., Harp, K. L. H., & Oser, C. B. (2013, March). Racial and gender discrimination in the stress process: Implications for African American women’s health and well-being. Sociological Perspectives, 56(1), 25–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2012.56.1.25

- Rosen, H. E., Lynam, P. F., Carr, C., Reis, V., Ricca, J., Bazant, E. S., & Bartlett, L. A. (2015, November 23). Direct observation of respectful maternity care in five countries: A cross-sectional study of health facilities in East and Southern Africa. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2012.56.1.25

- Sando, D., Ratcliffe, H., McDonald, K., Spiegelman, D., Lyatuu, G., Mwanyika-Sando, M., Emil, F., Wegner, M. N., Chalamilla, G., & Langer, A. (2016, August 19). The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16(1), 236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1019-4

- Sethi, R., Gupta, S., Oseni, L., Mtimuni, A., Rashidi, T., & Kachale, F. (2017, September 6). The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based maternity care in Malawi: Evidence from direct observations of labor and delivery. Reproductive Health, 14(1), 111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0370-x

- Sialubanje, C., Massar, K., Hamer, D. H., & Ruiter, R. A. C. (2015, September 11). Reasons for home delivery and use of traditional birth attendants in rural Zambia: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0652-7

- Smith, J., Banay, R., Zimmerman, E., Caetano, V., Musheke, M., & Kamanga, A. (2020, January 9). Barriers to provision of respectful maternity care in Zambia: Results from a qualitative study through the lens of behavioral science. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2579-x

- Sudhinaraset, M., Treleaven, E., Melo, J., Singh, K., & Diamond-Smith, N. (2016, Oct 28). Women’s status and experiences of mistreatment during childbirth in Uttar Pradesh: A mixed methods study using cultural health capital theory. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16(1), 332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1124-4

- Tato Nyirenda, H., Mulenga, D., Nyirenda, T., Choka, N., Agina, P., Mubita, B., Chengo, R., Kuria, S., & Nyirenda, H. B. (2018, July 16). Status of respectful maternal care in Ndola and Kitwe districts of Zambia. Clinics in Mother and Child Health, 15(2), 297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4172/2090-7214.1000297

- WHO. The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth – Healthy Newborn Network. 2017 [ cited 2020 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/resource/prevention-elimination-disrespect-abuse-facility-based-childbirth/

- Zacher Dixon, L. (2015, December 1). Obstetrics in a time of violence: Mexican Midwives critique routine hospital practices. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 29(4), 437–454. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12174