Abstract

This article presents career development concepts, tools, and exercises used in courses I teach to college dance majors. The focus is to introduce sustainable practices that withstand the inevitable internal and external influences shaping a dance career. Educators are encouraged to incorporate the applicable exercises into existing coursework to support their students’ transitions into the professional workforce.

I attended a dance conservatory program for college, but at that time there was no course in career development. Fortunately, many dance programs now offer this type of dedicated course or provide similar information within other courses. In this article, I introduce tools and exercises originated for use in the career development courses I teach, taking as a jumping-off point my what if attitude to surviving a forty-year career dotted with both highs and missteps. I encourage educators to select the applicable tools and exercises I discuss in this article to enhance students’ proficiencies in existing coursework such as dance production, senior project, directed or independent study, project-related dance courses, or even better, to institute a career development course.

My time in the dance conservatory program was followed by working for several dance companies. I then returned to university and obtained a bachelor’s degree in liberal studies in dance, psychology, and education and a masters of fine arts degree in dance. This background helped me survive twelve transitions, including a paralegal job when the dance field could not financially support me. My career low was spine fusion surgery in 2006. It took two months to learn to walk again. The temporary loss of physical mobility brought stress and depression in pondering what a future in dance could be for me as I was then in my mid-fifties. My emotional recovery turned a corner when I began a therapeutic what if exercise. The result was my seminar Surviving a Career in Dance presented to dance majors at several colleges and universities starting in 2008. Over time, the seminar expanded into full courses at two universities in California.

My courses and career development workshops aggregate my diverse work as a dancer, artistic director, producer, educator, author, curator, and arts funder. The framework of my courses introduces skill sets in segments of artistic identity, business practices, and grantsmanship. The overall learning objective is for students to acquire practices guiding their career development, management, and entrepreneurship to survive the new normal of a dance ecosystem, particularly as it is now altered by COVID-19.

ACTION PLAN FOR CAPACITY BUILDING, STRATEGIC PLANNING, AND INFRASTRUCTURE

The “C, S, I” concepts that Professor Homsey taught gave me the organizational structure and management skills to mobilize my artistic endeavors and academic career. Recently, I was accepted to the USC Masters of Arts in Teaching as a third-year undergraduate, and I am grateful for the tools gained through her course.

—Aurora Vaughan, USC Glorya Kaufman School of Dance, Class of 2021

The core theory, as the platform of my seminar and courses, is a framework I call C, S, I—capacity building, strategic planning, and infrastructure. This three-pronged theory grew from exposure to observing best practices during service as a board member of a theater, a municipal art park, and a hospital foundation, as well as leading my dance company for ten years. Additionally, I served on national, state, and local grant panels including the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) panel for the grant, Arts Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. It was a sobering moment as the number of dance companies that were turned upside down from the recession and were applying for help far exceeded the NEA’s ceiling of available funds. What I noted from the NEA’s rigorous review process was that the companies that were ultimately recommended for funding had articulated strong case statements with clear strategic planning and infrastructure narratives that detailed their plans to get back on track in advancing their organizational mission. Strategic planning and infrastructure represent two elements of the framework. I begin by offering a definition of each term in C, S, I.

C = Capacity Building: To acquire and verify the necessary information to proceed to the strategic planning to complete a project and achieve its goals.

S = Strategic Planning: To conceive a well-designed plan delineating the phases, tasks, and persons necessary to complete the project on time and on budget. This should include a Plan B for unexpected circumstances.

I = Infrastructure: To assemble the systems, resources, networks, and assets to manage the operational day-to-day activities of a project as well as the more complex multiyear services and programs.

S = Strategic Planning

A designer friend once told me, “Measure three times, and cut once!” This advice is my mantra in leading the dance company: Triple-check elements in my planning process before locking in the commitment to artists, engagement, or projects. Here is the bottom line: There is no shortcut to developing a well-conceived strategic plan that keeps to the timeline and stays on budget. In fact, a comprehensive multistep approach is necessary to developing a measured, triple-checked strategic plan.

As my dance company projects began to take shape, I would invite my inner circle of advisors and collaborators to join the conceptual process. Diverse input leaves no stone unturned in defining the complex elements of what, how, who, when, and how much. The collective perspective also adds invaluable checks and balances, including a Plan B consideration to handle unexpected circumstances.

I caution my students not to adopt a cut-and-paste approach in creating a strategic plan. Each project has a unique inquiry, purpose, rhythm, goal, collaborators, and so on. I encourage educators to instruct students to apply the following strategic planning tips as a general framework from which they can distinguish and individualize a project’s strategic plan.

Begin a 360-degree examination of the project and goal(s), articulating the starting point elements of participants, timeframe, and budget.

Define primary phases, specific tasks, and who is responsible. A spreadsheet format helps to view the project framework.

Confirm elements including venue, rehearsal space, artists, collaborators, community partners, required permits, copyright licensing, insurance, and other regulatory items as noted on the timeline.

Create a project budget based on accurate estimates of inflow (income) and outflow (expenses). A cash flow budget helps chart timing of inflow against the outflow of payments.

I = Infrastructure

As it relates to dance companies and arts organizations, infrastructure categories are the systems, resources, networks, and assets to manage and operationalize everything from daily activities to multiyear projects and services. I further delineate infrastructure with examples of three categories: administrative, marketing, and financial. The value of infrastructure for students is learning how to manage and organize their day-to-day activities. Once the infrastructure categories are determined, I remind students that over time their resources, networks, and assets will change as people leave positions, professional relationships shift, and donors reach their limit of support. A refresh of infrastructure will be needed from time to time.

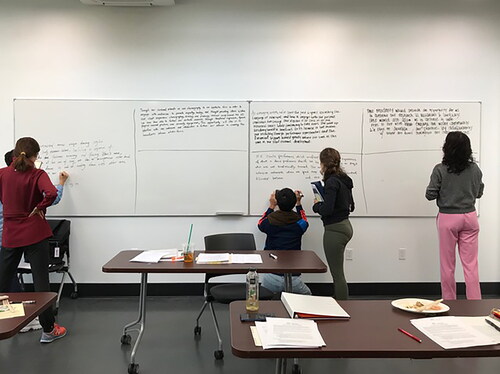

With my infrastructure activity, I first ask students to work in two groups and have them choose two categories and write those categories on the whiteboard. Second, each group adds a few subsets under each of their categories. For example, the administrative category might have subsets of filing, calendar systems, and contracts. This exercise is a fun, collaborative learning experience for students to grasp what infrastructure can mean to managing and operating their activities. The following is the “Infrastructure Categories and Subsets” outline that I created, showing examples of categories and subsets that are personal to the way that I organize and manage my day-to-day activities.

Infrastructure Categories and Subsets Exercise

Administrative

Filing system

Calendar system

Contracts or letter of agreements

Marketing

Website

Work samples

Digitized photographs, flyers, programs, reviews

Financial

Bookkeeping software

System for tax filings and reports

Budgets: Annual operating, cash flow, project, etc.

Educators might encourage students to consider adding an infrastructure category of wellness or self-care. More than ever, students need mechanisms to deal with the stress and pressures affecting their physical, emotional, and mental states. The inclusion of wellness or self-care builds practice in students to recognize these needs and not to be ashamed of prioritizing them to be self-sustaining for the long haul.

As an emerging Artistic Director of my own dance company, it was extremely helpful to hear Bonnie’s breadth of experiences, along with her logistical concepts and strategies. I now feel I have a greater set of skills to build a sustainable infrastructure for my dance company.

—Mitsuko Clarke-Verdery, MICHIYAYA Dance

C = Capacity Building Tools and Exercises: The Mission Statement

There can be personal and professional mission statements. For this article, the mission statement describes the student’s professional artistic identity, which will ultimately guide the spectrum of decision making. It is not unusual for students to initially feel blocked from writing a mission statement. Reasons run the gamut: too many skills, interests, or goals to choose from; undecided on a career direction; or unsure if dance is what they want to pursue.

To alleviate this stress, I focus on the exercise purpose: acquiring the skills to write a mission statement, with the understanding that the mission statement will change over time. The goal is for students to learn the mission statement writing process. The purpose is to generate a mission statement that is carved in stone. My mission statement exercise was conceived after decades of service on grant panels and experience conducting interviews and auditions. I learned that the strongest mission statements are written in an active voice, and they articulate the unique and distinct elements of the artist or company. Further, I personally adapted my mission statement into a one-sentence conversational “elevator” pitch to use whenever I was asked, “So, tell me about yourself.” Educators might address these considerations when presenting the mission statement exercise to students.

The following exercise helps students experience the synergy between the mission statement and how it guides career choices, big and small, from marketing choices that visually represent the mission statement to strategically pursuing the work opportunities that advance it.

Mission Statement Exercise

Articulate the why, how, and perhaps for whom in two sentences.

The first sentence is written in the active voice beginning with, “To …” to describe the why and perhaps for whom.

The second sentence describes the what and how of the student’s distinct elements that might include discipline or aesthetic references, cultures, stories, or performative or creative inquiry practices.

Bonnie’s approach to crafting mission statements helped me write a statement to stand out as an artist. It was also helpful to learn that I can create a mission statement for different career roles and projects in life.

—Marissa Brown, MFA California Institute for the Arts, Lone King Projects dancer, choreographer, director, West Side Story Broadway cast

Bonnie’s approach helps dancers get to the core of their identity and intent in dance. She expresses her high expectations for you and does not take lightly her responsibility to guide students to their mission statement.

—Kristin Tims, BFA, California Institute for the Arts

SWOT: STRENGTH, WEAKNESS, OPPORTUNITY, THREAT

The next artistic identity tool is called SWOT, an acronym for strength, weakness, opportunity, threat. Although SWOT is sometimes credited to Albert Humphrey as a business analysis tool in the 1960s, there is no universally accepted creator. My introduction to SWOT came via a facilitator for my dance company’s 1995 board retreat. She used SWOT as the starting point in the board of directors’ task to update our company’s mission statement.

To relate the value of SWOT to students, I ask them to list one-word characteristics on a blank paper. The four areas on the blank paper are labeled as follows:

Top left: STRENGTH Top right: WEAKNESS

Bottom left: OPPORTUNITY Bottom right: THREAT

Here are some examples of the SWOT internal and external characteristics.

Strength and weakness = Internal Attributes and Characteristics:

Strength examples: Communicator, problem solver, self-directed.

Weakness examples: Procrastinates, self-doubt, lazy

Opportunity and Threat=External or Work-related Actions, Behavior Features:

Opportunity examples: Networked, technology proficient, multilingual

Threat examples: Debt, resists change, defensive

At the board retreat, I saw the immediate benefit of applying the identified strengths and opportunities to revising the dance company’s mission. Afterward, I wondered about the application to me. What if I could establish a process to improve on my personal weakness and threats to my career ambitions? The investigation helped me to create an actionable exercise addressing my weakness through three steps, which transformed my behavior, action, and responses.

The back story is that one weakness I avoided confronting was communication, specifically an extreme anxiety when speaking in public settings. Despite touring around the world with the Martha Graham Dance Company, I literally became invisible at meetings and conferences, and functioning in interviews was a nightmare. My B.A.R. Analysis is an artistic identity exercise that I use in all my courses to help students ramp up their employment readiness. Here are the three steps of the B.A.R. Analysis for students to follow.

Identify one weakness or threat to improve on.

List the symptoms experienced when it occurs—physical, emotional, intellectual.

Focusing on the symptoms, create a sequence of small actionable steps that incrementally begin to alter the symptoms to the desired behavior, action, or response.

I share my first B.A.R. Analysis addressing my weakness of communication: anxiety and fear to speak in public settings.

My Personal B.A.R. Analysis Example

Area to improve: Communication: Anxiety and fear to speak in public settings.

Symptoms: Racing heartbeat, feeling faint, erratic breathing, profuse perspiration, throat tightening, blurry mental state

Sequence of small actionable “next steps”

Measured breathing to calm physical symptoms.

Practice “mission pitch” and prepare two questions.

Make eye contact before speaking.

Practice my “neutral stance” exercise before the event.

Enroll in voice lessons to learn proper voice projection technique.

Note: Repeat the first “next step” until the desired outcome is felt. Do not add additional “next steps” until each outcome has begun to shift the particular symptom. Be patient and consistent in practicing the sequence to change ingrained behavior, action, and response.

In reflecting on my communication problem, I realized it probably stemmed from being a third-generation Japanese-American woman culturally and generationally taught to be seen and not heard. The behavior was further embedded through early dance training and learning to use movement as a substitute medium of self-expression. This a-ha moment explained why I could perform in front of thousands, but speaking in a public setting raised a host of debilitating symptoms.

My “before” snapshot is extreme fear and anxiety symptoms rendering me barely able to think or speak in meetings and interviews. The “after” is the post B.A.R. Analysis experience of me at a California Confederation for the Arts Town Hall walking down the aisle to the microphone, then speaking in front of the large crowd about the lack of critical support for independent artists and small-budget dance organizations in Southern California. The B.A.R. Analysis slowly changed my weakness to a strength that resulted in an invitation to serve on the Bay Area Dance Coalition grant panel, which marked the beginning of thirty-five years of service as a panelist for national, state, and local government agencies, as well as private foundations.

The Behavior, Action, Response analysis has become a tool that I will keep coming back to as an artist. The exercise offered me a realistic understanding of my strengths and weaknesses as a working artist, which in turn has motivated me to start creating at my fullest potential.

—Taylor Donofrio, MFA Candidate, California Institute for the Arts

7 EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS

During my transition from dancer to artistic director, it became abundantly clear that I needed to develop stronger practices to effectively function in new leadership roles. Over time, I began to rely more on certain executive functions that improved my learning and processing abilities both in career and life. These executive functions became my list of what I call the 7 Executive Functions (7EFs) document. I use this document in my courses as another artistic identity tool guiding students’ self-reflection on the effective skills needed to be a valued team member and to step into leadership functions.

EMPLOYMENT TOOLBOX

The final artistic identity framework to introduce in this article is the Employment Toolbox Checklist. I compiled the Employment Toolbox Checklist to assist students in their employment preparation. My hope is that educators will share the checklist with students as a tool to develop their artistic identity action plan in the transition to the professional workforce.

Employment Toolbox Checklist

Mission statement, mission pitch

Resume or curriculum vitae, Applicant Tracking System format resume

Employment wish list

Marketing portfolio (digitized photographs, programs, reviews)

Work samples

Performance history document

Technical requirements document (for companies and choreographers)

The mission statement was already introduced in this article. Other Employment Toolbox items like resumes, marketing portfolio, and work samples are generically familiar. Educators might be less familiar with the employment wish list, performance history, and technical requirement documents. What follows are brief descriptions of these items.

An employment wish list is best done in a spreadsheet format. The document lists the student’s potential employers with specifics that can include contact information, job title, skill proficiency matches, and relevant audition and interview notes.

Performance history is often a spreadsheet-type document used by choreographers and companies to show activities typically for a three-year period. It provides funders and presenters the ability to gain a historical overview of the commissions, performance and touring, outreach, and educational activities. The formatting of the document can include columns specifically noting the presenter and venue, type of activity, dates of engagement, and attendance data.

The technical requirements document is important for choreographers and company directors. Presenters review this document to calculate their costs in generating the fee amount to book the choreographer or company. In my courses, I show students examples of dance company technical requirements from load-in to load-out. For the graduate students, one of my course assignments is creating a technical needs list to start the process of itemizing technical requirements. The technical needs list becomes a bridge document to share with a technical director who will draft the formal technical requirements document for presenters.

The Employment Toolbox helped identify my strengths and the intersectionality of dance and other professions to market myself to top companies and plan a career in dance and beyond.

—Paulo F. Hernandez-Farella, USC BFA Dance/Master of Public Administration, Ballet Hispánico, Company Dancer

IN CONCLUSION

In 2019, I presented workshops for emerging and midcareer professionals at Gibney in New York City. The feedback from the workshop participants inspired me to write this article. Testimonials from students and workshop participants are shared throughout this article to personalize the impact and benefit of my concepts, tools, and exercises.

The workshop offered a wealth of information that I am still digesting. I am struck by how I was able to express my mission in one sentence and how Bonnie’s reminding us how things can constantly be changing allowed me to commit fully in the moment because in the very next, I could be open to how I was changing as a person and as an artist.

—Bianca Paige Smith, dancer, choreographer, consultant, neuroscientist

The calling of artistic and creative passion cannot be diminished, even in the face of the new normal of COVID-19 in the dance ecosystem. I hope this article supports teachers in using applicable exercises to expand their students’ practices in the transition from the campus to professional opportunities. As readers, you should feel free to pick and choose what concepts, tools, and exercises can strengthen and fortify your students’ ambitions and career pathways. We all have the same objective: to prepare students to step into employment opportunities and even into future positions that do not currently exist. There is no time like the present to consider what if to boost the next generation of artists and innovators in realizing their unique purpose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I wish to acknowledge participants from my career development courses who gave me permission to share their comments regarding their experiences.