Why a special issue on LA?

Learning Analytics (LA) is both a growing trend and an increasingly prominent feature of contemporary twenty-first century teaching and learning that has captured the attention and imaginations of educators, researchers, policymakers, learning designers, and technologists alike. In this age of big data and smart cities, LA brings exciting new possibilities for more agentic, engaging, and equitable educational landscapes – or is at least perceived by many to bear such promise. As the use of computers and networked technologies become progressively ubiquitous alongside myriad forms of computer-mediated educational tools and data sources, LA may indeed offer much potential for enhancing learning agency and effectiveness, pedagogical reflexivity and adaptivity, socio-institutional efficiency and innovativeness. Yet, the challenges ahead are substantial.

In response to the broader educational community’s growing curiosity and interest in LA and its potential affordances for improving teaching and learning across diverse educational contexts, an inaugural International Symposium and Roundtable on LA was held recently by the National Institute of Education (NIE) with key institutional partners in Singapore. The event brought together four leading international LA scientists and more than a 100 local educational researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to dialogue and debate current advancements and conundrums in the field. Keynote speakers and presenters shared concrete examples and learnings gleaned from a range of LA innovations in tertiary and K-12 educational settings across Australia, North America, Europe, and Singapore.Footnote 1 Critical views and provocations were raised around a number of key questions perplexing the field. Specifically, what types of data, reflecting what forms of learning, to what ends, and for whose purposes, agenda, and gains? Issues of taken-for-granted epistemological and methodological assumptions and approaches, ethics, ownership, governance, as well as the opportunities (or lack thereof) for individual sense-making and collective meaning-making by students and teachers at the educational coalface, and how these might reciprocally inform the iterative (re)design and (re)deployment of LA tools and solutions for diverse communities of learners and educators were also contemplated.

While definitive answers remain far from reach, this special issue features a small collection of research papers and letters that directly engage with a number of these pertinent issues.

With this journal’s broader readership of educational researchers, policymakers, and pedagogues beyond the immediate Learning Sciences and Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) community in mind, we first draw attention to some notable milestones in the emergence of the LA field, highlight common definitional understandings, and outline some key challenges ahead. Then, we briefly set out an ecological pedagogic lens through which to situate LA and the papers featured in this special issue.

LA: the emergence of a nascent field, definitions, and challenges ahead

An evolving research-practice domain with rich interdisciplinary roots and connections

There is general consensus that the dawn of this millennium saw the emergence of LA as a distinct field from the applied disciplines of Machine Learning, Data Mining, and Intelligent Tutoring Systems, which in turn evolved in large part from the fields of Applied Statistics, Computational Linguistics, and Cognitive Science (Rosé et al., Citation2016). Since then, LA’s prominence and influence have been steadily growing within the interdisciplinary field of the Learning Sciences as a whole, and in particular, the CSCL community. In 2005, Machine Learning was explicitly acknowledged as constituting an integral component of the CSCL vision and work for the next decade. The next five years saw the area of automated and semi-automated analysis of collaborative processes to support and scaffold learning, in particular conversation analysis and social networks analysis, being increasingly featured. These were initially subsumed within more established topics such as Argumentation and Interactivity but gradually burgeoned into increasing numbers of standalone keynotes, plenary sessions, and workshops featuring Intelligent Support for CSCL, Interaction Analysis and Visualisation, Scripts and Adaptation, Data Mining and Process Analysis. There is also a clear reflection in recent LA work of the intentions and efforts in the field to incorporate more expansive and systemic perspectives of LA across diverse educational settings and stakeholders. The dedicated symposium foregrounding Analytics of Social Processes in Learning Contexts: A Multi-Level Perspective (Rosé et al., Citation2016) at the 2016 International Conference of Learning Sciences serves as one recent example.

Parallel to this proliferation of LA scholarship, the Society for Learning Analytics Research (SoLAR) was founded at the turn of this decade by an international and interdisciplinary network of researchers committed to exploring the role and impact of LA on learning and development. Through SoLAR-organised events such as the annual international conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge since 2011 and the Learning Analytics Summer Institute since 2013, the field has seen much growth in both rigour and representation from multiple disciplines and perspectives.

Defining LA

Understandably, the rich interdisciplinary theories and methodologies that characterise the field of LA also bring forth contested understandings, definitions, and foci of what counts as LA. Several definitions are more commonly referenced than others. For instance, the NMC Horizon Report 2016 defined LA as “an educational application of web analytics aimed at learner profiling, a process of gathering and analysing details of individual student interactions in online learning activities” (Johnson et al., Citation2016, p. 38). This definition highlights the analytics component but has been critiqued for its weak foregrounding of the learning element.

Agudo-Peregrina, Iglesias-Pradas, Conde-González, and Hernández-García (2014, p. 542) offered another conceptualisation of LA as the “analysis of electronic learning data allowing teachers, course designers and virtual learning environment administrators to investigate the unobservable patterns and the information underlying the learning process”. This definition emphasises the defining attribute of LA as that of making visible what is normally unseen. It also focuses the lens on learning processes rather than outcomes. The specificity of this definition lends clarity. However, it also sets excessive constraints on what constitutes LA – in terms of the forms of data, the modes and contexts of learning, the categories of stakeholders/users, and for what purposes. Many in the field recognise that these core elements of LA should ideally be more encompassing.

To this end, SoLAR’s definition of LA as “the measurement, collection, analysis and reporting of data about learners and their contexts, for purposes of understanding and optimizing learning and the environments in which it occurs” (http://www.solaresearch.org/: cited in Siemens & Gašević, Citation2012., p. 1) remains one of the most widely appropriated to date. This definition also underpins our understandings of, and approach to LA in this special issue, in that both the “seen” and “unseen” of learning processes, interactions, and outcomes need to be considered, with particular sensitivity to individual learners within situated learning contexts, and for the purposeful intent of generating new knowledge about learning and improving the educational endeavour.

Some key challenges confounding the field

LA has steadily matured over the past two decades as an applied field that can add value to the complex venture of learning and teaching. Such growth necessarily entails the field’s ongoing wrestle with a number of key challenges, both conceptual and instrumental. These include, among others:

a general lack of clarity around what constitutes LA – its definitional specificities, theoretical and methodological underpinnings, infrastructural necessities, practical applications and affordances, and the productive alignments across these components – especially among the wider educational community of policymakers, administrators, and teachers;

uncertainties around LA’s pedagogical relevance and value-add in contextualised learning and teaching settings across different disciplinary domains (e.g., STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics), Humanities, Language & Literacies, etc.), educational phases and modalities (e.g., tertiary, K-12, virtual, blended, etc.), cultures (e.g., ways of being, thinking, acting, and feeling) and over time;

the relative lack of rigorous documentation, characterisation and impact evaluation of LA “use-cases” and the extent to which these may (or may not) have improved learning and teaching interactions, processes, and outcomes for individuals and groups of students and teachers, and in what ways;

the scarcity of concrete examples of LA-enriched “powerful classrooms” that provides “equitable and robust learning environments in which all students are supported in becoming knowledgeable, flexible and resourceful disciplinary thinkers” (Schoenfeld & the Teaching for Robust Understanding Project, Citation2016, p. 1); and

few theory-practice models of wider socio-institutional adoption and diffusion, that make explicit the mechanisms that enable and/or impede the productive uptake of LA at scale, including those related to issues of data privacy, ownership, and ethics.

In the face of these complexities, the sustained growth trajectory of LA and the realisation of its transformative potential for contemporary education require a combination of “leadership, openness, collaboration and a willingness for researchers to approach LA as a holistic process that encompasses both technical and social domains” (Siemens & Gašević, Citation2012, p. 1). While there are no simple solutions nor easy resolutions at hand, we make the case here that several of the foregrounded challenges outlined above arguably converge on a recognised knowledge gap in the field – that of situating LA pedagogically.

The need for more explicit and deeper engagement with pedagogic theory in LA has been observed in extant literature (Ferguson, Citation2012; Koh, Shibani, Tan, & Hong, Citation2016). Much of LA work tend to subtly embed or vaguely point to pedagogical models, while others even claim pedagogical neutrality. LA pedagogical frameworks have been proposed. For instance, Wise (Citation2014) put forth a framework designing LA pedagogical interventions that is underpinned by constructivism, meta-cognition, and self-regulated learning theories, and built around four key learning principles (integration, agency, reference frame, and dialogue) and three learning processes (grounding, goal-setting, and reflection). Clearly explicated LA pedagogical models such as these, however, tend to remain few and far between.

Consequently, we suggest that a greater cognisance of the integrative interplay between LA and pedagogy may serve as one productive pathway forward in the field. In the next section, we set out an ecological pedagogic lens through which the interdependencies of LA and pedagogy – both productive and paradoxical – can be more clearly understood.

Towards an ecological lens for situating LA pedagogically

Learning, and by implication LA, cannot be divorced from pedagogy. Rather, learning and pedagogy are conjoined endeavours that need to be theorised, understood, studied, and designed in concert.

Pedagogy is concerned with the specific and cumulative relationships and interactions among learners, educators, the content, and the environment. It is inexorably a contested social construct and very much a “work in progress” (Alexander, Citation2008, p. 46). One of the most cogent and widely referenced definitions of pedagogy that have emerged amidst ongoing contestations in the field is that put forth by leading pedagogue Robin Alexander in his influential work Essays in Pedagogy (Citation2008):

[Pedagogy is] the act of teaching together with its attendance discourse of educational theories, values, evidence and justifications. It is what one needs to know, and the skills one needs to command, in order to make and justify the many different kinds of decision of which teaching is constituted. (p. 47)

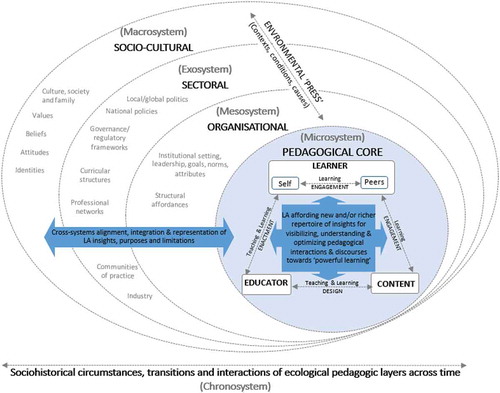

Defined this way, pedagogy – and by association, learning and LA – is a sociocultural phenomenon that is multifarious and ecological in nature. represents our attempt to coalesce and visually represent these understandings.

Through this lens, we underscore that pedagogy, learning, and LA are influenced by, and in turn influence multiple environmental systems (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1994) that comprise different stakeholders, agendas, structures, principles, and practices.

The pedagogical core

At the heart of the pedagogic ecology sits the pedagogical core – a term we use to refer to the dynamic and in-situ interactions amongst the learner, educator, and content that are most proximate to everyday educational practices in classrooms – both physical and virtual. The Learner, Educator, and Content constitute three “nucleus components” of the pedagogical core, and the interactions among these components can be further explicated as follows:

Interactions among the Learner-and-Content are broadly characterised as “engagement in learning”. These draw attention to students’ engagement in the learning experiences and with the learning content, as designed and facilitated by the educator (e.g., teacher) in the learning environment (e.g., classroom). Our conceptualisation of the Learner component here also takes into account the interactional engagements between individual students (self) and their peers when the learning experiences are group-based or collaborative in nature.

Interactions between the Learner-and-Educator are broadly characterised as the “enactment of teaching and learning”. These draw attention to the actual enactment or conduct of the educator’s planned teaching and learning activities in the classroom, and the actual responses of the learners to the educator as they reciprocally engage (or not) with one another throughout these activities.

Interactions between the Educator-and-Content are broadly characterised as the “design of teaching and learning”. These refer to the process by which the educator weaves together content knowledge (the “what” of teaching), pedagogical knowledge (the “how” of teaching), and pedagogical content knowledge (the blending of “how” and “what”) to design the content that best facilitates student learning.

Our conceptualisation of the pedagogical core as explicated above builds on recent articulations of Richard Elmore’s work on the “core of educational practice”, or sometimes referred to as the “instructional core” (City, Elmore, Fiarman, & Teitel, Citation2009; Office of Education Research, Citation2016). According to Elmore (Citation1996, p. 21), the “core of educational practice” refers to “how teachers understand the nature of knowledge and the student’s role in learning, and how these ideas about knowledge and learning are manifested in teaching and classwork… [which] includes structural arrangements of schools, such as the physical layout of classrooms, student grouping practices, teachers’ responsibilities for groups of students, and relations among teachers in their work with students, as well as processes for assessing student learning and communicating it to students, teachers, parents, administrators, and other interested parties” (p. 2).

On this front, LA bear particular potential for generating a richer repertoire of insights into these multifaceted pedagogic interactions and their attendant discursive practices – all of which are highly fluid and protean in nature (e.g., Buckingham Shum & Deakin Crick, Citation2016; Lockyer, Heathcote, & Dawson, Citation2013). The hope here is that LA can afford more accurate, timely, and meaningful evidence of learning and teaching interactions at the pedagogical core – such that learners, educators, and content designers can become more aware and have more agency to “optimise” the conditions for which “powerful learning” can be experienced. By “powerful learning”, we mean the extent to which classroom activity structures (1) provide opportunities for learners to become knowledgeable, flexible, and resourceful disciplinary thinkers (i.e., mastery); (2) invite and support the active engagement – cognitive, affective, and discursive – of all of the learners in the classroom/learning context (i.e., equitable access and agency), and (3) elicit student thinking and promote subsequent interactions that are responsive to students’ ideas and starting points, that address misconceptions and deepen understandings (i.e., formative assessment) (Schoenfeld & the Teaching for Robust Understanding Project, Citation2016).

One of the main upshots of the pedagogical core that we would like to stress here is that these proximate in-situ interactions among the learner, educator, and content – which constitutes the primary focus (and rightly so) of much LA work – do not occur in isolation. Rather these are being constantly shaped, reshaped, and reinforced through a succession of “communicative acts” by significant others – both human and machine – within wider encompassing organisational, sectoral, cultural, and teleological spheres.

Wider ecological influences beyond the pedagogical core

In other words, the pedagogical core (microsystem) is situated within broader ecological layers of the organisation (mesosystem), the sector (exosystem), society and culture (macrosystem), and time (chronosystem). These multiple layers constitute the environmental “press” that influences, and is reciprocally influenced by the contexts, conditions, and experiences of learning and teaching.

At the level of the mesosystem, organisational influences include the institutional setting and norms, leadership culture and practices, organisational goals, appraisal structures, and key performance indicators, among others. Influences exerted at the exosystem are wrought by pertinent groups or collectives that are more distal yet no less pertinent to the education sector as a whole. These include, for instance, local and global political pressures, national policies and policymaking processes, regulatory frameworks and curricular structures, as well as the salience and reach of professional networks, communities of practice, and industry at large. The macrosystem broadly encompasses the deep-seated prevailing values, beliefs, attitudes, identities, even myths (Inayatullah, Citation1998) that are produced and reproduced daily within and through families, communities, societies, and cultural groups. Last but not the least, the chronosystem recognises that these various “systems” are cumulative in nature. That is, they respond to and reflect sociohistorical circumstances, transitions, and interactions within and across the various ecological influences across time. Two points are worth noting here:

We explicitly articulate “values, beliefs, attitudes and identities” as macrosystem influences to signal the shared socio-cultural “commonsense” of societies and cultures. These are, however, not limited to the macrosystem of culture and society. Rather, these constitute deeply entrenched “cultural imperatives” (Tan, Citation2009) or shared cultural logics, norms and practices that are often least observable yet most powerful in driving collective behaviour that either reinforce pedagogical traditions or encourage innovation and change.

Each “system” comprises primary members or stakeholders whose driving agendas, principles, and practices may not easily align or complement one another across the various ecological layers. In fact, the best intentions of differing stakeholders across the multiple systems often result in paradoxical tensions played out and experienced by learners and educators at the pedagogical core. Some of these age-old pedagogical dilemmas include the strife for teaching efficiency versus learning effectiveness, standardisation versus personalisation, collaboration versus competition, performance versus mastery, among others.

To qualify, we do not posit these pedagogical dilemmas as dichotomous binary formulations that cannot both be accommodated or achieved at the one time. Rather, our point here is that advocating for one position or the other about learning and pedagogy might seem an easy affair. In fact, at a rhetorical or litany level (Inayatullah, Citation1998), these might even seem aligned and shared by multiple stakeholders across systems. However, it is only when the “rubber” of LA pedagogical initiatives “hit the road” of existing values, beliefs, principles, and practices at the levels of classrooms, organisations, sectors, and societies that seemingly insurmountable issues of cross-systems alignment and integration towards shared educational aspirations and goals come to the fore.

Our hope is that the ecological pedagogic lens proposed here may offer one perspective through which the confluence of pedagogical synergies as well as misalignments across systems/stakeholders, and over time, may be better understood, recognised, articulated, and deliberated. We would argue that the appropriation of such an ecological pedagogic lens by LA researchers and practitioners may go some length to augmenting the quality, relevance, and impact of LA on fostering richer and more meaningful educational experiences for our learners and teachers alike.

Papers in this special issue

Using the proposed ecological pedagogic lens as a frame, we now briefly introduce the five papers featured in this special issue. The first three empirical papers featured here can be primarily situated within the pedagogical core, in that they each document specific research-based LA methodologies and applications in practice that bear particular affordances for generating new or richer insights for visibilising, understanding, and optimising pedagogical interactions and discourses in authentic educational contexts.

Lee and Tan describe an LA application that has the potential to shed new and richer insights into students’ idea development and flow in discourse. Drawing from an online knowledge building discourse community comprising graduate students and teachers in a Singapore tertiary education context, the authors developed and tested a method for analysing and representing idea flow that was novel in its combination of a suite of text mining and network analytics, as well as visualisation techniques. The research monitored and tracked idea movement that occurred throughout the discursive interactions of learners and educators as they engaged with disciplinary content. They argue that these can help teachers better gauge levels of student understandings, uncover possible underlying misconceptions, and identify overly-dominant or disruptive cognitive patterns in the learning process. These can in turn aid the improvement of pedagogical design and enactment in ways that are more targeted and responsive to diverse student needs.

Hu’s paper describes WikiGlass, an automated assessment tool for students’ collaborative writing online. Implemented in several secondary schools in Hong Kong, WikiGlass automatically recognises, aggregates, and visualises students’ thinking levels based on their Chinese language writing in real-time over the length of the writing assignment. The real-time categorisation of this LA tool is a significant achievement in that it affords teachers greater opportunities to promptly evaluate their students’ writing standards throughout the writing process, to provide timely formative feedback and targeted scaffolding to slower-progressing students where needed. The author also makes the case that such an LA tool can aid in fostering self-directed learning among students, as well as inform the design and refinement of content, assessment rubrics, and teaching materials in productive ways.

Van Leeuwen, van Wermeskerken, Erkens, and Rummel’s paper foregrounds the importance of the educator’s role by presenting a case study that explicates the ways that a teacher construed and appropriated an LA tool to make specific pedagogical decisions. The study used a combination of novel data sources and approaches, such as mouse-clicks, eye-tracking, and cued retrospective reporting, to provide a fine-grained analysis of the teacher’s sensemaking strategies and collaborative classroom orchestration. By turning the spotlight on the educator, this paper addresses an important gap in LA extant literature. While nascent, this work raises important questions about taken-for-granted (albeit deeply mistaken) assumptions around the ease and linearity of translating LA data into productive pedagogical choices and practices in classrooms.

In a letter to the editor, Rosé further expounds on this imperative research problem in LA of expediting the cycle from the generation of LA data to the analysis of student needs to the consequent informed design of productive pedagogical interventions for better student learning experiences and outcomes. Simply put, the road from LA data to actionable insights is neither straightforward nor certain. Such pedagogical endeavours are necessarily complicated, but they do not have to be chaotic. Rosé outlines one case in which such complex pedagogical work can be approached in principled ways. She discusses how DiscourseDB – a publicly available data infrastructure – employs an analytic approach that enables the translation of data from multiple streams into a common, integrated representation, which in turn allows the application of common modelling tools to identify opportunities for pedagogical interventions that may help improve student learning trajectories.

Last but not least, Gašević, Kovanović, and Joksimović provide a commentary that offers a synthetic overview of the field, then propose a consolidated model of LA research and practice that comprises three interconnected dimensions – theory, design, and data science. Their paper closes by emphasising the importance of multi-perspective approaches to LA for the field’s sustained growth and impact on scholarship and practice. In many ways, this paper resonates with, substantiates, and complements the ecological pedagogic lens we set out in this editorial for theorising LA and its incumbent educational affordances and conundrums.

This special issue constitutes our modest contribution to the field’s ongoing research and collective deliberations – theoretical, empirical, and practical – associated with the design, use, and impact of LA in diverse educational contexts. To close, we appropriate renowned statistician George Box’s famous assertion: “Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful” (Box & Draper, Citation1987, p. 424).

In the same spirit, we invite our readers to join us in exploring, critiquing, and building upon the ideas, discoveries, and opinions about LA put forth in this special issue – and while doing so, to hang a healthy question mark on the things we may have long taken for granted about the compelling venture of learning and pedagogy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Phillip Towndrow for his suggestion of the term “situating LA pedagogically” and his feedback on the ecological pedagogic model proposed in this editorial letter. We also thank Miss Tee Yi Huan for her editorial assistance in this special issue.

Notes

1. Interested readers may wish to view the videos of the keynotes and presentations on the Office of Educational Research’s YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL9HaqFfbs1mR5X_Kg9AGyWXrEdusHbm1r. Keynote speakers and topics presented at the inaugural international LA symposium hosted by NIE included:

Key Lessons Learnt in Learning Analytics, by Dragan Gasevic (President, Society for Learning Analytics Research; Professor of LA and Informatics at the University of Edinburgh)

From discourse analytics to design for team-based learning in online education, by Carolyn Rose (President, International Society of learning Sciences, Professor, Language Technologies and Human Computer Interaction at Carnegie Mellon University)

Insights into Learning: The Application of Video and Social Analytics for Promoting Student Learning by Shane Dawson (Professor of Learning Analytics and Director, Teaching Innovation Unit at the University of South Australia)

The Silent Analytics Driven Transformation of Medical Education, by Nabil Zary (Director of LET, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, Visiting Professor at Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University)

Fostering 21st century literacies through a collaborative critical reading and learning analytics environment: Learner-perceived benefits and problematics, by Jennifer Pei-Ling Tan (Assistant Dean, Knowledge Mobilisation and Senior Research Scientist, NIE Singapore)

Dispositional and Discourse Analytics in My Groupwork Buddy: Possibilities, Paradoxes and Pathways, by Elizabeth Koh (Assistant Dean, Research Translation and Research Scientist, NIE Singapore)

References

- Agudo-Peregrina, Á. F. , Iglesias-Pradas, S. , Conde-González, M. Á. , & Hernández-García, Á. (2014). Can we predict success from log data in VLEs? Classification of interactions for learning analytics and their relation with performance in VLE-supported F2F and online learning. Computers in Human Behavior , 31, 542–550. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.031

- Alexander, R. (2008). Essays on pedagogy . New York: Routledge.

- Box, G. E. , & Draper, N. R. (1987). Empirical model-building and response surfaces (Vol. 424). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. Readings on the Development of Children , 2(1), 37–43.

- Buckingham Shum, S. , & Deakin Crick, R. (2016). Learning analytics for 21st century competencies. Journal of Learning Analytics , 3(2), 6–21. doi:10.18608/jla.2016.32.2

- City, E.A., Elmore, R. F. , Fiarman, S. E. , & Teitel, L. (2009). Instructional rounds in education: A network approach to improving teaching and learning . Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Elmore, R. (1996). Getting to scale with good educational practice. Harvard Educational Review , 66(1), 1–27. doi:10.17763/haer.66.1.g73266758j348t33

- Ferguson, R. (2012). Learning analytics: Drivers, developments and challenges. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning , 4(5/6), 304–317. doi:10.1504/IJTEL.2012.051816

- Inayatullah, S. (1998). Causal layered analysis: Poststructuralism as method. Futures , 30(8), 815–829. doi:10.1016/S0016-3287(98)00086-X

- Johnson, L. , Adams Becker, S. , Cummins, M. , Estrada, V. , Freeman, A. , & Hall, C. (2016). NMC horizon report: 2016 higher education edition . Austin, TX: The New Media Consortium.

- Koh, E. , Shibani, A. , Tan, J. P. L. , & Hong, H. (2016). A pedagogical framework for learning analytics in collaborative inquiry tasks: An example from a teamwork competency awareness program. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge, Edinburgh, United Kingdom (pp. 74–83). New York: ACM. doi:10.1145/2883851.2883914

- Lockyer, L. , Heathcote, E. , & Dawson, S. (2013). Informing pedagogical action: Aligning learning analytics with learning design. American Behavioral Scientist , 57(10), 1439–1459. doi:10.1177/0002764213479367

- Office of Education Research . (2016). 17th request for proposals: School improvement and core research program . Singapore: National Institute of Education. Unpublished document.

- Rosé, C. P. , Gašević, D. , Dillenbourg., P. , Jo, Y. , Tomar, G. , Ferschke, O. , … Yang, S. (2016). Analytics of social processes in learning contexts: A multi-level perspective. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS) 2016, (Vol. 1, pp. 24–31). Invited Symposium. Singapore: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

- Schoenfeld, A. H. , & the Teaching for Robust Understanding Project . (2016). An introduction to the Teaching for Robust Understanding (TRU) framework . Berkeley, CA: Graduate School of Education. Retrieved from http://tru.berkeley.edu

- Siemens, G. , & Gašević, D. (2012). Guest editorial: Learning and knowledge analytics. Educational Technology & Society , 15(3), 1–2.

- Tan, J. P-L. (2009). Digital kids, analogue students: A mixed methods study of students’ engagement with a school-based Web 2.0 learning innovation (Doctoral dissertation). Queensland University of Technology.

- Wise, A. F. (2014). Designing pedagogical interventions to support student use of learning analytics. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge,Indianapolis, IN, USA (pp. 203–211). New York: ACM. doi:10.1145/2567574.2567588