ABSTRACT

European Parliament elections are frequently held to be insufficient for conferring democratic legitimacy on the EU’s policy process. This has led a growing number of actors to suggest that deriving legitimacy from national parliaments offers a suitable remedy for the EU’s democratic deficit, following the principles of ‘democratic intergovernmentalism’. Yet little attention has been paid to the effect such reforms might have on representation in practice. This article presents a novel way of visualising the problem by recalibrating the balance of power in the European Parliament between 2009 and 2024 to reflect the composition of national parliaments and the results of national elections. It finds that actors within the Greens/EFA group would be particularly vulnerable to a loss of influence. This raises important questions about the potential representative costs associated with democratic intergovernmentalist approaches.

Introduction

The European Parliament has been assigned a privileged role in efforts aimed at tackling the European Union’s (EU) ‘democratic deficit’. In the early years of its existence, the Parliament largely performed a consultative and supervisory function, with national governments retaining authority over legislative decisions (Roos, Citation2020). Motivated in part by a drive to enhance the legitimacy of the integration process, this situation has changed substantially since the introduction of direct European elections in 1979, notably through the extension of the principle of co-decision, now called the EU’s ‘ordinary legislative procedure’ (Héritier et al. Citation2015).

However, increasing the powers assigned to the Parliament is only one part of the equation when it comes to improving EU democracy. To be capable of providing sufficient legitimacy, most scholars contend that the Parliament must also be genuinely representative of the views of citizens (Hix, Citation1998). This typically entails at least two components: first, that sufficient numbers of citizens choose to participate in European elections, and second, that they vote with a view to the Parliament’s policy responsibilities rather than merely using the opportunity to register their views on domestic politics (Follesdal & Hix, Citation2006). In short, it is necessary that European elections become more than mere ‘second-order national contests’ (Reif & Schmitt, Citation1980).

Despite the substantial increase in the Parliament’s powers, turnout dropped in every European election between 1979 and the 2014 European elections, rising only in the most recent contest in 2019 (Fiorino et al., Citation2019; Franklin & Hobolt, Citation2015). When voters do participate, previous studies have found little evidence that they ‘think European’ (Hix & Marsh, Citation2011). These deficiencies have added weight to alternative strategies for improving EU democracy founded on the principles of ‘democratic intergovernmentalism’ (Bellamy, Citation2013; Patberg, Citation2016).Footnote1 Such approaches reason that if European elections are ‘second-order’ and therefore incapable of conferring genuine legitimacy on the policy process, legitimacy should instead be derived from elections that are ‘first-order’, namely elections to national parliaments.

The most significant step in this direction has been the EU’s Early Warning Mechanism, established via the Lisbon Treaty, which assigns national parliaments the right to raise objections to a Commission proposal if they believe it is inconsistent with the principle of subsidiarity (Kiiver, Citation2012). Democratic intergovernmentalism has also found an expression in a series of alternative reforms put forward by academics and political stakeholders. Some of the more radical options include abolishing the European Parliament altogether or returning to the previous ‘dual mandate’ system under which representatives could be selected from national legislatures. Menon and Peet (Citation2011), for instance, contend that the introduction of direct elections to the European Parliament and the removal of dual mandates broke the ‘organic link’ that existed between national parliaments and the European level, leading to a direct loss of legitimacy. Lelieveldt (Citation2014) argues that a return to the dual mandate system would increase the Parliament’s leverage and standing relative to the other EU institutions and emphasise the interconnectedness of EU and national politics. These ideas touch on the notion that in the absence of a single European ‘people’, we are better served by conceiving of the EU as a demoicracy of multiple peoples (Nicolaïdis, Citation2013). For Bellamy and Castiglione (Citation2013), the European Parliament has failed to provide legitimacy precisely because the social conditions required for it to represent the collective interests of a European people are lacking – a problem that may be remedied by introducing European issues into the national channel of representation.

Yet, in spite of the influence this strand of thought has had on the trajectory of European integration, relatively little attention has been paid to the practical implications for representation. As Wolkenstein (Citation2019) notes, contributions are typically framed in strictly conceptual or normative terms, with a focus on inputs rather than outputs. This is a curious oversight when one considers that the associated reforms are unlikely to be free from distributive consequences. Alongside normative justifications, it is important to capture these consequences if we are to acquire a full picture of the likely effects.

This paper constitutes a first attempt to fill this gap. The analysis is structured as follows. The first section draws on the existing integration literature to emphasise the importance of distributive consequences to the democratic deficit debate. The second section builds on this discussion to focus on methods for capturing the distributive consequences of democratic intergovernmentalism, using the dual mandate as a case study and outlining a novel approach for measuring how the balance of power in the European Parliament would have changed between 2009 and 2024 if it reflected the composition of national parliaments and the outcomes of national elections. This exercise uncovers a notable reduction in the visibility of politicians from the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) group, which raises some important questions about the potential representative costs associated with democratic intergovernmentalist approaches.

Distributive consequences and the democratic deficit

Adopting the terms of Tsebelis (Citation1990), we can classify reforms aimed at tackling the democratic deficit as either ‘efficient’ or ‘distributive’. A reform that is ‘efficient’ is one that produces outcomes that are Pareto-optimal: it improves the conditions of relevant stakeholders without damaging the interests of other actors. A ‘distributive’ reform produces outcomes that are redistributive or value-allocative: it improves conditions for one set of actors, but at a cost for others who may be disadvantaged. It can be expected that few reforms will be entirely efficient or distributive and that most will lie at some point on a scale between these two extremes.

Distributive consequences may be inter-institutional, such as a reform that boosts the influence of one institution over another, or intra-institutional, where reforms affect the balance of power within an institution. Kreppel (Citation2002), for instance, has documented how the growth in the European Parliament’s exogenous power since the 1970s has affected the institution’s internal development. The analysis finds that internal reform processes have been far from neutral, highlighting a ‘consistent trend of power and influence flowing toward … the two largest party groups’ (Kreppel, Citation2002, p. 8). This serves to underline that modifying the inter-institutional balance between the EU’s key decision-making bodies can trigger corresponding changes to the intra-institutional balance of power within these institutions (Farrell & Héritier, Citation2007; Naurin & Rasmussen, Citation2011).

If all democratic intergovernmentalist reforms could be classified as ‘efficient’ in nature, there would be questionable utility in examining their distributive consequences. However, in practice, the application of democratic intergovernmentalist principles to the EU’s legislative process is unlikely to be free from distributive implications. Some democratic-intergovernmentalist approaches are openly distributive in nature: there can be little doubt that abolishing the European Parliament or bringing back the dual mandate would generate clear winners and losers. Those parties and political actors currently present in the European Parliament would effectively have their responsibilities reassigned to political actors present in national parliaments. Even in the unlikely scenario that the composition of the European Parliament had directly mirrored the balance of power in national parliaments prior to the reform, there would be indirect distributive consequences. Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) may behave differently from members of national parliaments in their relations with their party leadership given they are obliged to balance the wishes of national parties alongside those of the European parliamentary group to which they belong (Hix, Citation2002; Mühlböck, Citation2012). This implies that some interests would be less visible than before.

The picture is less clear in the case of other reforms. The Early Warning Mechanism was never presented as a vehicle for curtailing the power of the European Parliament or national governments. As Cooper (Citation2012) explains, the new powers assigned to national parliaments were envisaged as being ancillary to those of the Council and Parliament. Considering the overall impact of the system to date, it would be difficult to argue against this perspective. The Early Warning Mechanism has thus far only been triggered on three occasions and in only one of these cases was the relevant legislation withdrawn (Huysmans, Citation2019).

There are nevertheless two important caveats that should be made in relation to this reading of the Early Warning Mechanism and the involvement of national parliaments in the EU policy process more broadly. The first is that, as yet, the principle remains underdeveloped. There have been frequent calls to expand the scope of the Early Warning Mechanism by assigning national parliaments the right to veto proposals directly, most notably in the context of David Cameron’s renegotiation prior to the United Kingdom’s referendum on EU membership in 2016 (Smith, Citation2016). It is debateable whether the Early Warning Mechanism’s limited impact is reflective of its status of an ‘efficient’ reform, or whether this is simply a by-product of the relatively weak nature of the framework that has been implemented.

Second, while national parliaments have so far had little success in using the Early Warning Mechanism to block proposals outright, there is some evidence they have found new avenues to enter into a policy dialogue with the EU’s institutions and thereby shape legislative outcomes (Cooper, Citation2019). Other studies have emphasised the potential signalling role the system plays in Commission decisions to withdraw proposals (Van Gruisen & Huysmans, Citation2020). Cooper (Citation2013) goes as far as to characterise the reform as a lasting shift from a ‘bicameral’ to a ‘tricameral’ legislative model, with national parliaments joining the Council and the European Parliament as a de facto third chamber at the EU level. This might ultimately set the EU on a trajectory that ‘is likely to produce final legislative outcomes different from those … in the pre-Lisbon ‘bicameral’ system’ (Cooper, Citation2012, p. 443).

More importantly, even if we accept that it is possible for a given democratic intergovernmentalist reform to be classified as ‘efficient’, it is worth underlining that the starting point for contributions is a diagnosis that the European Parliament has failed to provide sufficient legitimacy to the policy process and that actors at the national level offer a better conduit through which the views of citizens can be represented (Wolkenstein, Citation2019). If properly implemented, it would be unusual for this principle not to produce distributive consequences, whether through a reduction of the powers of the European Parliament, a shift in the influence of particular actors within the Parliament and the visibility of particular interests, or via a wider alteration to the EU’s institutional balance. Although it is natural for authors to place emphasis on the normative benefits of reforms when proposing remedies for the democratic deficit, without adequately taking on board the potential representative costs associated with their implementation, any evaluation is likely to be incomplete.

One objection that might be raised to the argument made in this paper is that while democratic intergovernmentalism may well carry distributive implications, these consequences simply lack salience in comparison to the normative concerns associated with the democratic deficit. We might reason that if European Parliament elections are a substandard democratic process, the loss of influence for parties and interests empowered by that process would be a small price to pay for improved legitimacy. Similarly, if certain parties and interests with a stronger presence in national parliaments are inhibited from exercising greater authority at the European level, we might in principle welcome any reform that can redress this balance. While this paper does not seek to dispute the notion that normative concerns should be afforded the greatest weight in analyses, there are at least three observations that can be put forward to justify the relevance of distributive consequences to the integration literature.

The first is that legitimacy is not only concerned with inputs, but also with the outputs of a policy process. As Scharpf (Citation2017:, p. 315) explains, ‘democratic legitimacy presupposes effective governing and problem-solving capacity’. For Mair (Citation2009:, p. 5), this distinction is of particular importance in modern democracies because parties have increasingly ‘moved from representing interests of the citizens to the state to representing interests of the state to the citizens’, while ‘the representation of the citizens … is given over to other, nongoverning organisations and practices’ such as interest groups and social movements.

In the electoral reform literature at the national level, this is evident in debates over electoral systems such as first-past-the-post, which are typically justified not on the basis that they offer the purest expression of citizens’ views, but on the grounds that they promote stable majority governments (Blau, Citation2004). At the European level, authors such as Majone (Citation2002) have argued that greater democratic involvement for citizens in the EU policy process might paradoxically damage the legitimacy of institutions like the European Commission if it undermines their capacity to perform the core functions assigned to them. Scharpf (Citation2015) contends that while critics of EU democracy have tended to focus on input-oriented deficiencies in EU political processes, the relatively high levels of public trust invested in the EU throughout most of its history suggests that citizens are more concerned with standards of output-oriented legitimacy. He highlights that the crisis in Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union that began in 2010 undermined this trust, leading the EU to experience a ‘significant decline of output-oriented political support on which it could rely prior to the crisis, but also with the increased political salience of its input-oriented democratic deficit’ (Scharpf, Citation2015, p. 20).

This distinction between inputs and outputs has been further refined by Schmidt (Citation2013), who conceives of a third category of throughput legitimacy. Throughput legitimacy essentially captures the quality of the processes that link inputs to outputs, with factors such as the accountability of key actors and the transparency of decision-making also playing a role in the overall legitimacy of EU policymaking. It is important to note that while many of the democratic intergovernmentalist reforms that have been proposed are focused on inputs, they also have relevance for throughput legitimacy. However, as Schmidt and Wood (Citation2017) acknowledge, neither input-oriented nor throughput legitimacy negate the need for output-oriented legitimacy. Throughput legitimacy is best understood as a necessary but insufficient condition. The absence of throughput legitimacy is problematic, but its presence alone cannot compensate for deficiencies in inputs and outputs.

All of this underlines that EU legitimacy cannot be understood without also accounting for outputs. Upgrading the Early Warning Mechanism by assigning national parliaments the right to veto proposals, for example, might well meet all of the input-oriented legitimacy standards of democratic intergovernmentalism, but if it came at the cost of paralysing the EU’s legislative process it might have the net effect of reducing legitimacy overall. For democratic intergovernmentalism to provide a convincing remedy for the democratic deficit, it must account for all three categories of legitimacy – input, output, and throughput – and the distributive consequences of a reform are likely to be highly relevant to this equation.

The second reason why scholars should be interested in the distributive consequences of democratic intergovernmentalism is that they are important empirically, even if we reject their relevance to questions of legitimacy. This is readily apparent in the context of electoral reform at the national level. While proposed changes to electoral systems are often justified by political actors on the basis of their capacity to improve democracy or produce more representative electoral outcomes, most studies of electoral system change emphasise the role of partisan interests (Nunez & Jacobs, Citation2016). As Benoit (Citation2004) states, we can expect electoral reform to be pursued when a coalition of parties holding sufficient power to implement a change anticipates that it will acquire electoral gains under an alternative system. Indeed, the fact that major changes to electoral systems are a relatively rare phenomenon in Europe underlines the role of self-interest. As Renwick (Citation2010) explains, the interests of politicians who hold a majority can typically be served by maintaining the status quo. This barrier can only be overcome under specific circumstances, notably when a high level of citizen disengagement strengthens the position of reformers through an ‘elite-mass interaction’ process (Renwick, Citation2011). In contrast, values and abstract conceptions of legitimacy are rarely assigned a privileged position in explanations (for an exception, see Bol, Citation2016). Much like electoral reform agendas at the national level, EU reform processes are unlikely to be properly understood without an appreciation of the distributive implications of proposals.

Third, the distributive consequences of democratic intergovernmentalism have a potential policy impact which is worthy of attention in its own right. Consider, for instance, the European Parliament’s role in ratifying EU trade deals (Servent, Citation2014). In June 2019, the EU reached a trade agreement with the Southern Common Market (Mercosur). One of the key features of the discussions surrounding ratification since the conclusion of negotiations has been strong criticism expressed by MEPs within the Greens/EFA political group, which had been considerably strengthened in the 2019 European Parliament elections (Karatepe et al., Citation2020). Given Green parties had a less visible presence in national parliaments at the time of the 2019 European Parliament elections, it is not unreasonable to suggest the ratification process may have been conducted very differently if national representatives, rather than MEPs, were assigned sole responsibility for overseeing ratification. Reforms aimed at tackling the democratic deficit are thus not only important for EU legitimacy, but potentially for policy outcomes across the full breadth of the EU’s competences.

Capturing the distributive consequences of democratic intergovernmentalism: the dual mandate

A potential explanation for why the proponents of democratic intergovernmentalism have tended to focus on inputs rather than the outputs of proposals is that capturing distributive consequences is an undeniably complex undertaking. It would be beyond the scope of any analysis to account for the possible distributive consequences in all of the reforms that have been put forward given the diverse nature of what has been proposed. Yet the fact this task is challenging makes it no less important. This paper seeks to make a first step by focusing on one model: the return of a dual mandate system to the European Parliament as a substitute for direct elections.

There are two convincing reasons to start with the dual mandate. First, the system itself is relatively clear in its scope. A key weakness of the democratic intergovernmentalist literature is its lack of concrete institutional design proposals. The dual mandate system not only represents a tangible model for making the EU more intergovernmental, but is also a system that has previously been implemented at the European level. There are a number of possible variants when it comes to the proportion of dual mandate representatives that might be allowed in the chamber and the mechanisms for assigning national representatives, but we can anticipate that irrespective of the precise nature of the system, it would ultimately be reflective of the balance of power within national parliaments and the popular support of parties at the national level. This allows for a broad assessment of how representation might differ following the reform.

Second, examining the case of the dual mandate serves a twin purpose. Aside from illustrating how the balance of power would shift in the European Parliament under a dual mandate system, the exercise also gives a general indication of the differences that exist between representation at the national and European levels. This is a fundamental issue when it comes to measuring the distributive consequences of democratic intergovernmentalism. While previous studies have compared the performance of parties in national and European elections to establish second-order effects (Hix & Marsh, Citation2011; Marsh, Citation1998), there has yet to be a systematic assessment of how representation differs overall between national parliaments and the European Parliament. In examining the implications of returning to a dual mandate system, the analysis presented below also fills this gap.

Methodology

To assess how a dual mandate system might alter representation within the European Parliament, I construct two alternative parliaments for the 2009-14, 2014–19 and 2019–24 parliamentary terms using national election data.Footnote2 The first parliament is constructed using the percentage vote share of parties in the national election immediately preceding the start of the parliamentary term, while the second parliament is based on the share of seats won by parties in the relevant national election. As an example, for the 2019–24 parliamentary term, national election data from the 2017 German federal elections was used to calculate the distribution of German representatives as this was the national election that immediately preceded the 2019 European Parliament election. The logic here is that if a dual mandate system were to be implemented, it would reflect the balance of power in national parliaments at the beginning of the parliamentary term.Footnote3

In several countries, there is more than one parliamentary chamber for which seat shares could be used. This was treated on a case-by-case basis, but the principle was largely to use seat totals from lower chambers as these typically carry the most salience. For instance, if a dual mandate system were implemented, it would likely be the balance of power within the Italian Chamber of Deputies, rather than the Senate of the Republic, that would dictate the relative composition of the bloc of representatives sent to Brussels and Strasbourg.

The parliament constructed using vote share data offers an alternative measure of how representation might shift under a dual mandate system. In certain member states, the use of vote shares is complicated by the fact citizens cast more than one vote in national elections. Germany’s mixed-member proportional electoral system, for instance, includes both a constituency and a party list vote. In France, the two-round electoral system produces two different vote share figures for each round. Again, this was treated on a case-by-case basis and convention was largely followed in selecting the figure that is most commonly cited as a party’s ‘vote share’ in a relevant election. In Germany, the party list vote was selected, while in France, the first round was used. This necessitated a degree of subjectivity and there is scope for arguing that the figures may have differed if different approaches had been adopted.

Neither of the two constructed parliaments should be afforded more weight than the other as they effectively capture different dynamics. Vote shares are likely to overlook support for parties that are only active in a limited geographic area, but which hold relatively large numbers of seats in their national parliament, such as the Scottish National Party (SNP) in the 2017 general election in the United Kingdom. Alternatively, due to the particular features of national electoral systems, parties might receive high vote shares, but relatively few seats in national parliaments. The Front National in the 2012 French legislative elections offers an example, recording 13.6% of the vote in the first round of the election, yet only securing 2 seats in the French National Assembly. In several countries that use proportional representation systems, the parliaments constructed using vote shares and seat totals were similar or identical. However, in others, including the UK and France, the two figures were very different. Providing both estimates allows for a broader picture of support for parties at the national level.

Having gathered the data, I then assigned seats in the two alternative parliaments to parties using the D’Hondt method, while identifying the European affiliation of each party at the time of the relevant European Parliament election. In cases where a party was assigned a seat in the two hypothetical European Parliament chambers but did not hold a seat in the actual European Parliament, either the party’s stated European affiliation at the time of the opening session was recorded, the party’s affiliation in the previous parliament was used, an imputed affiliation was determined, or the seats were assigned to the ‘non-attached members’ (NI) group. In cases where a party had previously belonged to one political group in the European Parliament, but subsequently changed this affiliation by the time of the opening session of the European Parliament in 2009, 2014 and 2019, the affiliation at the time of the opening session was used.

There are a number of further considerations that are worth highlighting. First, it should be noted that although most member states distribute seats in the European Parliament using a proportional representation system with a single constituency, other states, such as the United Kingdom (with the exception of Northern Ireland, where the single transferable vote system was adopted), have used regional closed list systems that divide the country into different constituencies. This analysis nevertheless treats every state as a single unit in calculating the representatives assigned to the two hypothetical parliaments. Alternatively, it is likely that certain autonomous or semi-autonomous territories, such as South Tyrol in Italy, would be afforded representation under a dual mandate system, irrespective of the number of seats or votes secured by parties from these territories in national elections. It is impossible to systematically account for all of these cases in the calculation, but it can be anticipated that the impact on the two constructed parliaments will be relatively small overall.

Second, if the dual mandate system were to be implemented, there may be special provisions made for independent members of national parliaments to become representatives. For this reason, where states had large vote shares in national elections for independent members, these were treated as if they were a single party in the calculation. In practice, this was only relevant in the case of Ireland, which has a substantial presence of independent members of parliament. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that as the calculation relies on the vote shares and seat totals for parties in national elections, it may downplay the presence of independent members.

Third, it is not uncommon for parties to contest a national election as part of an alliance with other parties. This made the calculation complicated in cases where a joint vote share was recorded for an alliance, but the member parties of this alliance held different European affiliations. For instance, in the 2007 Belgian federal election, the Christian Democratic & Flemish (CD&V) party contested the election in alliance with the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA). However, following the 2009 European elections, these two parties sat in different political groups in the European Parliament – the CD&V was a member of the group of the European People’s Party (EPP), while the N-VA was a member of the Greens/EFA group. The CD&V/N-VA alliance received 5 seats in both of the constructed European Parliament chambers based on their seat totals and vote shares in the 2007 Belgian federal election, raising the question of how these seats should be apportioned between each of the two parties. This issue was solved by assigning seats proportionally based on the number of seats won by each party in the relevant national election – in this case, the CD&V held 25 of the alliance’s 30 seats in 2007, while the N-VA held 5 seats, resulting in the CD&V receiving 4 of the assigned 5 seats in the dual mandate parliaments and the N-VA being assigned 1 seat. This approach was used for all cases in which European affiliations were split within alliances.

Finally, several parties that were assigned seats on the basis of their performance in national elections had ceased to exist by the time of the following European Parliament election. Each of these cases required careful consideration. Judgements were based on factors such as previous affiliations held by the party or the affiliations of successor parties which had incorporated members of the disbanded party.

Results

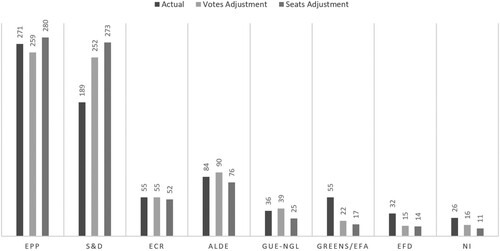

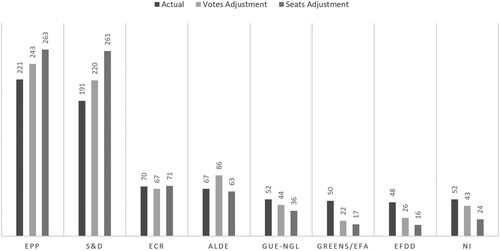

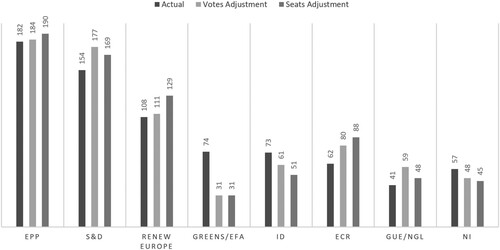

below present an overview of the three parliaments. They indicate how the share of seats held by each of the political groups in the European Parliament would have changed in the 2009-14, 2014–19 and 2019–24 parliamentary terms from the actual seat totals if a dual mandate system had been implemented that reflected the vote share secured by parties at the previous national election and the number of seats held by parties in national parliaments.

Figure 1. Composition of the 2009–14 European Parliament using hypothetical dual mandate systems based on vote shares and seat totals in national elections.

Figure 2. Composition of the 2014–19 European Parliament using hypothetical dual mandate systems based on vote shares and seat totals in national elections.

Figure 3. Composition of the 2019–24 European Parliament using hypothetical dual mandate systems based on vote shares and seat totals in national elections.

The figures indicate several features that merit attention. The first is that the S&D group increases its share of European Parliament seats in every calculation. In the 2009–14 and 2014–19 parliaments, this increase is particularly large: rising by 84 and 63 seats in the two dual mandate parliaments covering the 2009–14 term, and by 70 and 29 seats in the two dual mandate parliaments covering the 2014–19 term. The increase is smaller in the 2019–24 parliamentary term, but the S&D group still qualifies as the largest ‘winner’ of any group in the 2019–24 parliament calculated using national vote shares and has the third largest increase in the parliament calculated using national seat totals. The EPP group also tends to gain representatives in these calculations, but to a smaller extent than the S&D group and in one case (the 2009–14 parliament calculated using national vote shares) the EPP group actually loses representatives. In every calculation, the S&D group gained a larger number of seats than the EPP group.

The Greens/EFA group and the EFD/EFDD/ID groups, in contrast, lose seats in every calculation. The Greens/EFA group was the biggest ‘loser’ in every dual mandate parliament, losing over 50% of its seats in every case. The reduction in representatives for the EFD/EFDD/ID groups was also considerable, qualifying as the second biggest loss of representatives in every parliament. There was also a reduction in NI members in every parliament, which is potentially expected if second-order effects are assumed – smaller parties with no representation in national parliaments may be more likely to lack European affiliations.

The picture for the ALDE/RE, ECR and GUE/NGL groups is more mixed. The large increase in the 2019–24 seat-total parliament for the RE group is largely attributable to the substantial majority secured by Emmanuel Macron’s La République En Marche! at the 2017 French legislative elections. Similarly, the Liberal Democrats’ performance in the 2010 UK general election accounted for an extra 17 representatives for the ALDE group in the 2014–19 European Parliament calculated using national vote share data. The ECR group is relatively unaffected in the 2009–14 and 2014–19 parliaments, but experiences a large increase for the 2019–24 parliaments, which is primarily a reflection of the governing Conservative Party in the UK only securing four seats in the 2019 European Parliament elections. The increase in representatives for the GUE/NGL group in the 2019–24 dual mandate parliaments derives from several different parties, including La France insoumise in France, Die Linke in Germany, and the Unidas Podemos alliance in Spain.

This raises the question of whether these differences are significant and if we can expect them to be sustained over time. As a starting point, I opted to treat each political group in each parliament as a distinct unit and used a two-tailed paired sample t-test to compare the share of representatives in the three European Parliaments in the dataset (the actual European Parliament, the European Parliament constructed using seat totals in the preceding national election, and the European Parliament constructed using the vote share from the relevant national election). This indicated four significant results (p < 0.05) for the 2009–14 parliaments: the S&D gaining representatives in both the dual mandate parliaments and the Greens/EFA losing representatives in both dual mandate parliaments. For the 2014–19 parliament, there were three significant results: the S&D gaining representatives in the dual mandate parliament reflecting seat totals at the national level and the Greens/EFA losing representatives in both dual mandate parliaments. Finally, in the 2019–24 parliament, there were also three significant results: the Greens/EFA losing representatives in both dual mandate parliaments and the GUE/NGL gaining representatives in the dual mandate parliament constructed using vote shares from national elections.

Given the relatively large reduction in representatives for the EFD/EFDD groups, it might seem surprising that these effects were not significant. The reason for this is the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) accounted for a very high percentage of the lost representatives in the 2009–14 and 2014–19 parliaments. The party lost 13 representatives in the 2009–14 parliament constructed using national seat totals (out of the 18 the EFD group lost overall) and 12 representatives in the 2009–14 parliament constructed using national vote shares (out of the 17 the EFD group lost overall). In the 2014–19 parliament, UKIP lost 24 seats in the parliament constructed using national seat totals (out of 32 representatives lost by the EFDD group overall) and 22 seats in the parliament constructed using national vote shares (accounting for all 22 of the representatives lost by the EFDD group). While these effects are not deemed to be statistically significant for the political group overall, they would have nevertheless had a real impact at the individual party level if the 2009–14 and 2014–19 parliamentary terms had been based on a dual mandate system reflecting national seat totals or vote shares. It is an open question as to whether UKIP would have been capable of building its profile to the extent it did under such a system – and indeed whether the UK’s subsequent exit from the European Union may have played out differently as a result.

Discussion

The above exercise serves to illustrate that a dual mandate system would likely have created distinct winners and losers over the 2009-14, 2014–19 and 2019–24 parliamentary terms. While centre-left parties in the S&D group would have potentially seen their influence increase, alongside other actors such as members of the GUE/NGL group in the 2019–24 parliament, the visibility of members of the Greens/EFA group would have likely been substantially reduced, as well as individual parties with a high level of visibility such as UKIP. Whatever might be concluded about the normative benefits of returning to a dual mandate system, these distributive consequences would have significance for the EU’s legitimacy and policy outcomes.

Moreover, given the alternative parliaments detailed above are not simply relevant to the dual mandate, but act as a general proxy for the differences between national and European election results, they provide a broad indication of the kind of distributive consequences that might be expected from applying democratic intergovernmentalist principles to the EU’s policy process overall. While democratic intergovernmentalism may well offer a route toward increasing the legitimacy of the EU’s policy process, it seems unlikely this can be realised without generating distributive consequences. These consequences clearly merit inclusion in analyses.

With this stated, assessing the dual mandate alone cannot cover the full implications of democratic intergovernmentalism. Indeed, for many democratic intergovernmentalist scholars, reforming the allocation of representatives within the European Parliament would not go far enough. More radical approaches, such as abolishing the Parliament and returning to a decision-making process rooted in the actions of national executives may produce entirely different outcomes. It is vital to recognise that the dual mandate system assessed above is reflective of the balance of power in national parliaments and that this may differ substantially from the actions of national governments. The analysis above essentially provides insights on the kinds of distributive consequences that may arise from reforming the current EU policy process using democratic intergovernmentalist principles. A complete reshaping of the policy process would produce different results.

As a final exercise, it is worth considering how these insights might be situated within the wider democratic deficit debate. Although this paper does not seek to answer the question of whether the above representative costs would be worth bearing for the sake of greater EU legitimacy, it is possible to anticipate how this debate might be structured in future studies to take account of distributive consequences. For instance, how might we conceptualise the finding that actors from the Greens/EFA group would be particularly at risk from a dual mandate system when judging the capacity of this reform to tackle the democratic deficit?

It should perhaps not be surprising that Green parties perform better in European elections than they do at the national level.Footnote4 It has been widely argued that environmental problems such as climate change are best tackled at the supranational level (Wurzel et al., Citation2019). Moreover, the EU has sought to position itself as a global leader on environmental issues and has been an active player in international efforts such as the negotiations that led to the 2015 Paris climate agreement (Parker et al., Citation2017). This speaks to the longstanding question of whether voters are more likely to back certain parties in European Parliament elections as a result of second-order effects, or whether, for a certain percentage of voters at least, this choice reflects a perception that certain issues are simply more ‘European’ (Hix & Marsh, Citation2011). The answer to this question will determine, to a greater or lesser extent, normative conclusions about the merits of democratic intergovernmentalism. While all democratic intergovernmentalist contributions operate from the standpoint that European Parliament elections are insufficient for conferring legitimacy on the EU’s policy process, the degree to which this is held to be true will have a substantial impact on whether the representative costs of pursuing a reform are worth enduring.

Conclusion

This paper has attempted to add some empirical weight to the long-running debate over the democratic deficit and the capacity for national parliaments to confer legitimacy on the EU’s legislative process. The empirical analysis offers a clear demonstration of why democratic reforms cannot be approached solely from a normative standpoint, given a recalibration of representation toward the national level implies substantial distributive consequences. It is vital that future contributions actively capture these dynamics to ensure that a suitable evaluation of reforms can be made: one that takes account not only of the inputs of EU democratic processes, but also the practical implications of new systems of representation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 ‘Democratic intergovernmentalism’ has no standard definition in the context of European integration. I follow Wolkenstein’s (Citation2019:, p. 2) use of the term as a normative standpoint that states ‘rather than shifting more authority to the supranational level, we ought to strengthen the role in EU decision-making of those arenas where democracy is (comparatively) functional or even vibrant, namely, national parliaments and national public spheres’.

2 Where possible, national election data was taken from the Political Data Yearbook published by the European Journal of Political Research. European Parliament election data was sourced from the website of the European Parliament.

3 Croatia joined the EU in 2013, but was included in the 2009–14 parliament for the sake of this exercise. The United Kingdom is included in the 2019–24 parliamentary term because it was still a member of the European Union at the beginning of the term. For the same reason, the dual mandate parliaments do not take account of the redistribution of seats in the European Parliament that took place following the UK’s exit on 31 January 2020.

4 It should be noted here that the Greens/EFA group is not only made up of Green parties, but also regionalist parties in the European Free Alliance.

References

- Bellamy, R. (2013). ‘An ever closer union among the peoples of Europe’: Republican intergovernmentalism and demoicratic representation within the EU. Journal of European Integration, 35(5), 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.799936

- Bellamy, R., & Castiglione, D. (2013). Three models of democracy, political community and representation in the EU. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(2), 206–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.746118

- Benoit, K. (2004). Models of electoral system change. Electoral Studies, 23(3), 363–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3794(03)00020-9

- Blau, A. (2004). Fairness and electoral reform. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 6(2), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856X.2004.00132.x

- Bol, D. (2016). Electoral reform, values and party self-interest. Party Politics, 22(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068813511590

- Cooper, I. (2012). A ‘virtual third chamber’ for the European Union? National parliaments after the treaty of Lisbon. West European Politics, 35(3), 441–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665735

- Cooper, I. (2013). Bicameral or tricameral? National parliaments and representative democracy in the European Union. Journal of European Integration, 35(5), 531–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.799939

- Cooper, I. (2019). National parliaments in the democratic politics of the EU: The subsidiarity early warning mechanism, 2009–2017. Comparative European Politics, 17(6), 919–939. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-018-0137-y

- Farrell, H., & Héritier, A. (2007). Introduction: Contested competences in the European Union. West European Politics, 30(2), 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380701238741

- Fiorino, N., Pontarollo, N., & Ricciuti, R. (2019). Supranational, national and local dimensions of voter turnout in European parliament elections. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(4), 877–893. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12851

- Follesdal, A., & Hix, S. (2006). Why there is a democratic deficit in the EU: A response to majone and moravcsik. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(3), 533–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2006.00650.x

- Franklin, M., & Hobolt, S. B. (2015). European elections and the European voter. In J. Richardson, & S. Mazey (Eds.), European Union: power and policy-making (pp. 399–418). Routledge.

- Héritier, A., Moury, C., Schoeller, M. G., Meissner, K. L., & Mota, I. (2015). The European parliament as a driving force of constitutionalisation. European Parliament.

- Hix, S. (1998). Elections, parties and institutional design: A comparative perspective on European Union democracy. West European Politics, 21(3), 19–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389808425256

- Hix, S. (2002). Parliamentary behavior with two principals: Preferences, parties, and voting in the European parliament. American Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 688–698. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088408

- Hix, S., & Marsh, M. (2011). Second-order effects plus pan-European political swings: An analysis of European parliament elections across time. Electoral Studies, 30(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2010.09.017

- Huysmans, M. (2019). Euroscepticism and the early warning system. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(3), 431–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12809

- Karatepe, I. D., Scherrer, C., & Tizzot, H. (2020). Das mercosur-EU-abkommen: Freihandel zu lasten von umwelt, klima und bauern. Greens/EFA Group in the European Parliament.

- Kiiver, P. (2012). The early warning system for the principle of subsidiarity: Constitutional theory and empirical reality. Routledge.

- Kreppel, A. (2002). The European parliament and supranational party system: A study in institutional development. Cambridge University Press.

- Lelieveldt, H. (2014). The European Parliament should return to a ‘dual mandate’ system which uses national politicians as representatives instead of directly elected MEPs. LSE European Politics and Policy – EUROPP blog.

- Mair, P. (2009). Representative versus responsible government (MPIFG Working Paper).

- Majone, G. (2002). The European commission: The limits of centralization and the perils of parliamentarization. Governance, 15(3), 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00193

- Marsh, M. (1998). Testing the second-order election model after four European elections. British Journal of Political Science, 28(4), 591–607. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712349800026X

- Menon, A., & Peet, J. (2011). Beyond the European parliament: Rethinking the EU’s democratic legitimacy. Centre for European Reform.

- Mühlböck, M. (2012). National versus European: Party control over members of the European parliament. West European Politics, 35(3), 607–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665743

- Naurin, D., & Rasmussen, A. (2011). New external rules, new internal games: How the EU institutions respond when inter-institutional rules change. West European Politics, 34(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2011.523540

- Nicolaïdis, K. (2013). European demoicracy and its crisis. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 51(2), 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12006

- Nunez, L., & Jacobs, K. T. E. (2016). Catalysts and barriers: Explaining electoral reform in Western Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 55(3), 454–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12138

- Parker, C. F., Karlsson, C., & Hjerpe, M. (2017). Assessing the European union’s global climate change leadership: From Copenhagen to the Paris agreement’. Journal of European Integration, 39(2), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1275608

- Patberg, M. (2016). Against democratic intergovernmentalism: The case for a theory of constituent power in the global realm. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 14(3), 622–638. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mow040

- Reif, K., & Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine second-order national elections - a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results. European Journal of Political Research, 8(1), 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x

- Renwick, A. (2010). The politics of electoral reform: Changing the rules of democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Renwick, A. (2011). Electoral reform in Europe since 1945. West European Politics, 34(3), 456–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2011.555975

- Roos, M. (2020). Becoming Europe’s parliament: Europeanization through MEPs’ supranational activism, 1952–79. Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(6), 1413–1432. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13045

- Scharpf, F. W. (2015). Political legitimacy in a non-optimal currency area. In O. Cramme, & S. B. Hobolt (Eds.), Democratic politics in a European Union under stress (19-47). Oxford University Press.

- Scharpf, F. W. (2017). De-constitutionalisation and majority rule: A democratic vision for Europe. European Law Journal, 23(5), 315–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12232

- Schmidt, V. A. (2013). Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: Input, output and ‘throughput’. Political Studies, 61(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x

- Schmidt, V. A., & Wood, M. (2017). Conceptualizing throughput legitimacy: Procedural mechanisms of accountability, transparency, inclusiveness and openness in EU governance. Public Administration, 97(4), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12615

- Servent, A. R. (2014). The role of the European parliament in international negotiations after Lisbon. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(4), 568–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.886614

- Smith, J. (2016). David cameron’s eu renegotiation and referendum pledge: A case of déjà vu?’. British Politics, 11(3), 324–346. https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2016.11

- Tsebelis, G. (1990). Nested games: Rational choice in comparative politics. University of California Press.

- Van Gruisen, P., & Huysmans, M. (2020). The early warning system and policymaking in the European Union. European Union Politics, 21(3), 451–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520923752

- Wolkenstein, F. (2019). The revival of democratic intergovernmentalism, first principles and the case for a contest-based account of democracy in the European Union. Political Studies, 68(2), 408–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719850690

- Wurzel, R. K. W., Liefferink, D., & Di Lullo, M. (2019). The European council, the council and the member states: Changing environmental leadership dynamics in the European Union. Environmental Politics, 28(2), 248–270. doi:10.1080/09644016.2019.1549783

Appendix 1

– Explanation of methodology and data.

There were two main sources of data used in the analysis. First, I sourced the results of the 2009, 2014, and 2019 European Parliament elections (seat totals and vote shares) from the European Parliament website. Second, where possible I used the Political Data Yearbook published by the European Journal of Political Research to source the seat totals and vote share figures for the most recent national election to have taken place before the 2009, 2014 and 2019 European Parliament elections. These figures were then crosschecked with official election results reported by election agencies in each of the EU member states.

Using this data, I then created tables for each EU member state with the three national election results and the European affiliations of each party in the subsequent European Parliament election. I used the D’Hondt method to assign seats to these parties using the national election results, with the total number of seats in each country matching the number of MEPs each state was assigned in the following European Parliament election (also sourced from the European Parliament website). I then merged all of the data for each member state with the actual distribution of MEPs in the 2009, 2014, and 2019 European Parliaments.