ABSTRACT

This project aimed to explore staff and student opinions on the introduction of choice in assessment, drawing upon the principles of Inclusive Pedagogy, Disability Studies and Universal Design. The mixed methods research explored the possibility that students may feel more positively supported during the assessment and feedback process if a range of methods of assessment are available.

There was overall support for the proposal, but with some reservations, for example, parity between the different modes of assessment, and student access to different forms of assessment to develop employability skills would need to be planned. Inclusive assessment and feedback processes in Higher Education are essential if the diversity of our students is to be recognised. However, this needs to be balanced with the need to develop a range of life skills. Therefore, choice in assessment methods needs to be designed with clear strategies for skills development, and targeted individualised support.

1. Introduction

This case-study paper is based on a university research project, ‘Suggesting Choice: Inclusive Assessment Processes’, which aimed to explore staff and student opinions on the introduction of choice in assessment methods, drawing upon the principles of Inclusive Pedagogy and Universal Design, in a School of Social Sciences in a Russell Group University. Hockings’ review of the literature (Citation2010, p. 21) suggests that having choice in assessment mode enables students to deliver evidence of their learning in a medium that suits their needs, rather than in a predetermined and prescribed format which may disadvantage an individual or group of students in the cohort. The impact of having choice is an under-researched area, although O’Neil’s (Citation2017) recent study examines the procedures and outcomes of students’ choice of assessment methods and suggests that whilst there is significant complexity needing consideration, the impact of limited choice is positive for students, and can result in higher grade attainment. This project investigated whether students would feel that equality of access and flexibility in learning was supported during the assessment and feedback process if a range of methods of assessment (presentation, oral examination, written assignment or exam) were available. The research also explored the challenges of such a process for students and staff in terms of parity, workload, and future employability.

In recent times the quality, nature and processes surrounding assessment and feedback in Higher Education have received much attention (Evans, Citation2013; HEA, Citation2017b). Sambell (Citation2016) argues ‘assessment exerts a major influence on students’ approaches to study in Higher education’ (Sambell, Citation2016, p. 1) and underlines the importance of Boud’s claim, ‘Students … cannot (by definition if they want to graduate) escape the effects of poor assessment’ (Citation1995, p. 35) which was based on concerns that poor practices, understandings and interpretations in relation to assessment were widespread. Worryingly, despite Boud’s assertion being more than twenty years ago, students continue to report their experiences are rarely positive and as Mann (Citation2001) argued poor assessment and feedback experiences can negatively impact students’ experience of university leading to disaffection and distress.

Consequently, there has been a focus on measures to ensure the quality of assessment and feedback and promote its relationship to improving student learning. This has intensified with the National Student Survey (NSS) data – containing a dedicated question set on assessment – impacting Higher Education league tables and the more recent introduction of the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF). Key themes or areas of interest have emerged in the literature which include: assessment for learning, alignment of assessment tasks with learning outcomes, teaching and developing assessment literacy; feedback and feedforward; and encouraging peer and self-assessment (HEA, Citation2017b). Evans (Citation2016) highlights that in order to enhance assessment and feedback practices there should be an interrelationship of the three ‘core’ elements – assessment literacy (the specific requirements of assessment), assessment feedback (giving, receiving, understanding, interpreting and acting on feedback) and assessment design (including authenticity of assessment task, volume and nature of assessment and collaborative development to support shared understandings).

Another dimension which Sambell (Citation2011) argues is critical to the debate around assessment is the importance of ‘authentic assessment’ – tasks which are meaningful and relevant and of potential benefit beyond university (e.g. in employment). When the assessment is positioned in ‘real’ or authentic contexts students have opportunities to rehearse, develop and refine their intellectual understanding and skills and apply them to bring about deeper level learning. As Entwhistle (Citation2000, p. 1) argues, deep learning involves ‘the intention to extract meaning produces active learning processes’. Therefore, a rich assessment diet becomes especially important to enable students to practise and rehearse skills and attributes that will be vital for their future lives and continued learning. Fung (Citation2017) showcases an increasing evidence base of examples of authentic, ‘outward-facing’ assessments and the positive impacts they can have on both learners and staff.

In addition to the recent focus on assessment in the literature, the project was also shaped by disability studies literature and research into inclusive education. The principles of inclusion are now supported and promoted globally by UNESCO:

Inclusive education is a process that involves the transformation of schools and other centres of learning to cater for all … Its aim is to eliminate exclusion that is a consequence of negative attitudes and a lack of response to diversity

(UNESCO, Citation2009, p. 4).

They are further supported by the anticipatory duties of the Equality Act 2010 in relation to the protected characteristic of disability (EHRC, Citation2015). Similarly, the Welsh Government suggests that ‘Inclusive education is an ongoing process concerned with ensuring equality of educational opportunity by accounting for and addressing the diversity present.’ (Welsh Government [WG], Citation2014). Ainscow (Citation1995) distinguishes between integration, that is, making a limited number of additional arrangements for individual students, and inclusion, which requires the introduction of a more radical set of changes through which educational institutions redesign their processes and provisions so as to be able to embrace all learners (Frederickson & Cline, Citation2002, p. 75).

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) (Barajas & Higbee, Citation2003; Hockings, Citation2010; Johnson & Fox, Citation2003; Waring & Evans, Citation2015) is one such pedagogical principle, arising from inclusive education and disability studies aiming to foster inclusion. It arose initially from environmental design, and was developed through the lens of inclusive education and disability studies. Hockings state that research in Universal Design suggests that, when considering pedagogy, rather than making reasonable adjustments for particular students with additional learning needs (ALN), such dyslexia, or a speech impairment, ‘an alternative approach is to design curricula that learners can customise to suit themselves, thus minimising the need for last minute (or individual) adjustments and avoiding the need for students to disclose hidden differences.’ (Hockings, Citation2010, p. 26)

Similarly, the HEA (Citation2012) suggests that in order for HE institutions to comply with the Equalities Act 2010, when considering assessment, institutions should design assessments that are both anticipatory and inclusive. Norwich (Citation2002, p. 496) recognises the dilemmas facing the teaching profession between the acknowledgement of difference and the need for group provision and equity, making individual adjustments for students undertaking assessments does not provide an inclusive educational experience. Inclusive assessment processes provide for all students whilst also meeting the needs of specific groups. This might include using a variety of assessment methods, providing adequate preparation for assessment and assessment information, giving a choice of tasks, and using formative strategies (HEA, Citation2012, p. 13). Specifically in relation to student choice in assessment methods, studies by Waterfield and West (Citation2006) and Craddock and Mathias (Citation2009) and most recently O’Neil (Citation2017) highlight the complexity of issues surrounding the implementation of student choice in relation to: equity, perception of staff and students, careful and transparent alignment and impact on outcomes. Despite these complexities O’Neil (Citation2017) also highlights the positive impact of limited choice for students, with the attainment of higher grades than those achieved by previous student cohorts who did not experience choice.

It was a combination of the theoretical critique of discriminatory social and institutional processes highlighted by the social model of disability (Oliver, Citation1990), and equality and Universal Design principles, together with evidence from these studies that gave impetus for this small-scale case study. The research question was framed as: ‘Do staff and students perceive that a choice in assessment methods following the principles of Universal Design would improve their experience of learning and teaching and improve equality of opportunity in assessment?’

2. Methods

Hammersley (Citation1995, p. 148) argues that the researcher must acknowledge the politics of positionality, and that research reflects ‘perspectives from particular angles’, open to criticism and re-interpretation. As a participant researcher in the school, the researcher is part of the tradition of action research, defined by Kemmis and McTaggart (Citation1988, p. 5) as ‘a form of collective self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants … to improve the rationality and justice of their social or educational practices’. The research conformed to BERA Ethical Guidelines (Citation2011), and received the approval of the School ethics committee before commencement. Thus, the information sheet informed students and colleagues that all data would remain anonymous and securely stored, and that no data would be used in training or publications without prior approval.

Using the definitions suggested by Stake (Citation2005, p. 445), the project is an ‘intrinsic case study’ in that the contexts, activities and viewpoints are from a bounded case, that is one School in a University, and are examined in order to facilitate understanding of a broader issue, in this case the practices of assessment in HE, within the philosophy of action research. The limitations of a case study are widely recognised, as reliability and generalisability are central concerns (Gomm, Hammersley, & Foster, Citation2000). However, there are alternative interpretations of generalisability. Generalisability as ‘fittingness’, promotes good design which enables clear and detailed description, allowing for ‘comparability’ and ‘translatability’, which allows for components of the study to be used as the basis for generalisation through future comparison (Gomm et al., Citation2000, p. 75). In order to eliminate bias and improve validity, two researchers independently examined and analysed the data (Seale & Silverman, Citation1997). As (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, Citation2018, p. 253) argue, case studies ‘observe effects in real contexts, recognizing that context is a powerful determinant of both causes and effects’. Ethical considerations included thoughtfulness to the issues being explored for people with additional learning needs. Based on personal expertise, the issues were discussed sensitively, and where necessary interviewees were signposted to ongoing support services. Validity was enhanced through the anonymous distribution of the survey via administration services, and the selection of interview participants who were neither students of the researchers or close colleagues.

The format of the semi-structured interview enabled the researcher to explore and develop emerging themes, and allowed respondents ‘to answer more on their own terms’ (May, Citation2001, p. 123). As recommended by Charmaz (Citation2002), the questions were open-ended to encourage the generation of rich material, and to enable the participants to give emphasis to their own subjective meanings. The survey was distributed to the whole teaching staff and an undergraduate student population of the school, which was the boundary of the case study (Cohen et al., Citation2018), via a link to the online survey. Different online questionnaires were designed for staff and students, and in each case, at the end of the survey the option to participate in an interview was offered. An ordinal five-point scale was adopted to enable the assessment of subjective meaning (Saris & Galhofer, Citation2007, p. 104).

A total of 111 undergraduate student responses and 60 staff responses were received. Of the 111 student responses, 12% self-identified as having an additional learning need (ALN) (this is representative of the cohort numbers for ALN in the school, as identified through University Support Service assessments received by the School). No members of staff identified as having an ALN. Twenty-five students and 10 members of staff volunteered for interviews at the end of the survey, and five members of staff and five students were selected for an interview. The interview sample was chosen to be representative of the cross-section of the population of the school; in the student cases representation of ALN and non-ALN sections of the population were selected, and for staff, representatives of the job roles were selected, across different programmes in the case of lecturers.

Quantitative analysis of the survey responses was limited to descriptive statistics, to enable an interrogation of the weight of feeling on the topics for simple presentation of data. The descriptive data chosen were examined for their ability to address the question, in order to ‘arrive at a better understanding of the operation of social processes’ (Rose & Sullivan, Citation1996). This was a limited approach to descriptive statistical analysis, but within the bounds of the project produced some striking and useful results. Similarly, analyses of qualitative responses to the survey and the interview data were completed using inductive thematic coding (Charmaz, Citation2002), with themes emerging from the data. Repeated themes of consistency, barriers to learning, positive responses to choice, considerations of fairness and equity, employability, and assessment design were highlighted, identified by ‘frequency of certain phenomena or powerful, unusual comments’ (Pine, Citation2009, p. 257), which formed the basis of the discussion below.

3. Results

3.1. Current practices in the school

In order to understand the impetus for change, it was important to understand opinion on the current situation. Responses to the survey indicated significant differences in student satisfaction with assessment and feedback methods in the school, between those self-classifying as having an additional learning need, and those without.

Over a third (38%) of all students who self-identified as having an Additional Learning Need (ALN) stated that they were either ‘not at all satisfied’ or ‘not very satisfied’ with current methods of assessment. Comparatively, for those who did not self-identify as having an ALN, just over a fifth (21%) expressed this view. In addition, a lower level of satisfaction – either ‘a little satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ – was reported by those who self-identified as having an ALN (21%) when compared to their non-ALN counterparts (55%). This suggests those who have a disability, dyslexia or other ALN were more likely to feel dissatisfied with current assessment methods. This may provide an additional layer of explanation to current national themes of low National Student Survey (NSS) satisfaction with Higher Education assessment and feedback processes in the UK (HEA, Citation2012, p. 7).

Satisfaction with feedback mechanisms also varied by ALN, although the differences were much less pronounced. Just over 30% of all self-identified students with ALN stated that they were either ‘not at all satisfied’ or ‘not very satisfied’ with current feedback mechanisms. This compared to 25% of those who did not self-identify as ALN, expressing this view. Conversely, a slightly higher level of satisfaction with feedback – either ‘a little satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ – was evident amongst those self-identified as ALN (61.5%) when compared to their non-disabled counterparts (59.5%). Further analysis of the qualitative responses to the feedback question suggested that those with ALN who were dissatisfied felt that their feedback did not acknowledge or address their needs, whilst those without ALN are most dissatisfied with limited exam feedback processes.

The data from staff indicated a much greater satisfaction with methods of assessment, with just over 42% either ‘a little satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’, and only 20% either ‘not at all satisfied’ or ‘not very satisfied’. Similarly, for feedback mechanisms, nearly 63% of staff were ‘a little satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’, with only 13% ‘not at all satisfied’ or ‘not very satisfied’. This suggests that in general, staff are far more satisfied with the current assessment and feedback processes than students. However, it is interesting that some staff were not happy with the assessment and feedback mechanisms. This may be due to a number of early career staff working on modules with assessments designed by others, or due to School and University policies on assessments, for example, in standard word counts for assignments. Further research could explore this in more depth.

Thematic analysis of qualitative data from the online questionnaire responses and interviews provided some explanation for this data and coalesced around two prominent themes: consistency and barriers to learning, which are examined further below. However, it is important to note that some positive comments were received from 15 of the 111 respondents, with indicative responses including:

‘Good range of assessments throughout different modules’ (student without ALN)

‘I actually do think the support is really good here compared to what a lot of my friends say at other unis and on other courses.’ (student without ALN)

3.1.1. Consistency

Issues inconsistency in assessment and feedback processes was a recurrent theme in many responses and interview discussions. Fifty-two responses to the survey specifically mentioned the lack of consistency in feedback.

‘It’s really mixed. Sometimes I get feedback and staff will actually talk through it in lectures and in seminars really clearly. And other times like, I’ve literally had nothing, not even comments on the sidebar.’ (student with ALN)

3.1.2. Barriers to learning

All students with an ALN, but particularly those with dyslexia, felt that assessment frequently focussed on testing skills in the mode of assessment, rather than knowledge and comprehension of the topic. In current practice, students with ‘problems with written expression’ are noted in anonymised spreadsheets given to the markers, however no further detail on the needs of the individual is passed on:

‘The marker should know [that the student has dyslexia], but that is never represented in it [feedback] … they still highlight words saying you’ve got the wrong word there. Saying that the structure’s not right and they’re constantly on about the structuring in the feedback, one even said if the structuring was better I could have given you more marks. I never get feedback on the content, it is just the words and the structure.’ (student with ALN)

Three students, with ALNs associated with social interaction, felt that the design of class-based tests could create barriers for them:

‘Class tests in [one module] are unfair as you are allowed to confer with friends, but not everyone may feel comfortable doing this/may not have friends/be talkative and thus will suffer marks wise.’ (student with ALN)

Whilst student responses focussed on the design of the assessment and the feedback received, staff responses indicated that they believed issues related to ALN were the responsibility of other bodies within the University. Eight staff respondents felt that the students’ school experiences and the link to the Disability and Dyslexia service should have removed the barriers to learning:

‘I’m guessing they’ve had to deal with it [their ALN] throughout their school lives so they can do it. We rely heavily on student support to give us the advice on what the student needs.’ (Professional Services staff member)

However, problems in communication across university services were identified as problematic by six members of staff and three students:

‘They can be waiting months. I think processes and communication are clunky, inflexible, and refuse to build upon what is already known about the student’. (Senior Lecturer)

‘It’s [the assessment process for support] excessively procedural and I think for students who have a fairly standard set of needs, your standard dyslexic student who has no other kind of complicating issues, the procedure works very well. Um but outside of that its very messy.’ (Lecturer)

These links to a number of responses by staff and students on the identification and support of a range of students with additional learning needs who do not fit within the Disability and Dyslexia service remit. These included home students with English as an Additional Language (EAL), young carers, and those with anxiety and social phobias. Respondents identified the lack of provision for these groups, and lack of options for support beyond extenuating circumstances, leading to an increased burden for the extenuating circumstances committee.

3.2 Introducing choice

Anecdotal evidence from discussions with students and staff, together with a personal interest in inclusion had been the catalyst for this project, with many suggesting that lack of choice in fixed assessment methods impacted on student behaviour and achievement, particularly for those with ALN. When asked to rank the reasons for their module choices, the overwhelming majority of student respondents ranked ‘subject content’ in first or second place (91%). However, assessment mode was ranked the next highest, with 42% ranking assessment mode in first or second place (38% for those with ALN), above ‘lecturer’, ‘method of delivery’ and ‘relevance to future plans’. This suggests that in many cases for students the assessment mode is a strong influencing factor in the selection of modules.

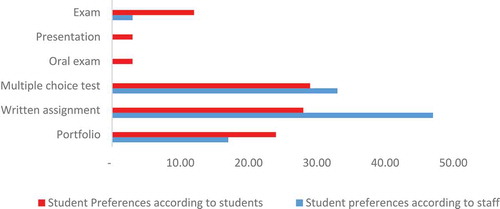

In comparing staff perceptions with students’ stated preferences for the types of assessment they preferred, it was evident that students favoured a wider range of assessment types () than currently perceived by staff.

In the survey, students were given an explanation of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles for assessment, and asked to rate their level of support for such a change. Overall 76% of students were in favour of such a change, either ‘quite supportive’ or ‘very supportive’, with only 8% ‘not at all supportive’ or ‘not very supportive’. The comparison between students with and without an ALN is particularly distinct, as no students with an ALN expressed a negative response.

In comparison, only 43% of staff were ‘very supportive’ or ‘quite supportive’, with 29% ‘neutral’ and 27% ‘not very supportive’ or ‘not at all supportive’. It is of particular interest that all four professional services staff who responded to this question were either not very supportive or neutral, suggesting the administrative challenges of enabling choice could be of particular concern. The implications of this are considerable when administrative staff can be seen as the ‘gatekeepers’ to enabling changes in practices, in terms of process, and was explained in qualitative responses, where concerns about capacity and administrative online systems were raised:

‘From an admin point-of-view, the system, the online system that we use now is really rigid. So I can’t see how we would do it, even I don’t know. We can’t make some other things work in it because it’s just not up to it.’ (Professional Services staff member)

3.2.1. Positive responses

Themes emerging from qualitative survey data and interviews were both positive and negative. There were 42 positive responses from students overall. Some stated that such a choice would allow students to choose modules by subject and relevance to future plans, rather than assessment method:

‘Students would be able to choose the modes of assessment that best suit them, meaning they should be able to achieve a higher grade. More autonomy and choice. More of a say when we are paying huge tuition fees is good.’ (student without ALN)

There was a great deal of support for being able to ‘play to strengths’:

‘I believe it accommodates every learning style. I think students would be happier and less stressed if they could choose assessment tasks.’ (student with ALN)

This was particularly noted for students with ALN, by students with and without ALN, and by staff:

‘Would create less pressure on those who may struggle with certain assessment methods, whilst allowing those who have a preferred one to flourish and use their skills.’ (student without ALN)

‘I would love the chance to take an oral exam as I have always had written communication issues. (student not identifying as having an ALN)’

Staff members also identified positives for students with an ALN:

‘If you think in terms of ALN and in terms of students with different needs, so obviously someone with dyslexia may often do much better in an oral presentation but then again someone with a stammer or a speech impediment or whatever will prefer to do a written assessment so I think pedagogically I think it’s fine, in terms of inclusion I think it’s fine, my only concern would be process.’ (Senior Lecturer)

3.2.2. Fairness

However, despite the positive responses statistically, a large number of the qualitative responses had reservations about a straightforward choice. Students were most concerned about ‘fairness’, as they perceived some forms of assessment to be easier than others:

‘If I was going to do an assignment, how do you make that the same weighting as someone who does a presentation or someone who does an exam. It’s very difficult, if not impossible, to, especially if you threw in there multiple choice answers.’ (student without ALN)

Interestingly, there was wide variation in which mode of assessment students felt was the most challenging, with the four suggestions (presentation, oral examination, written assignment or exam), being equally weighted as challenging, in the responses.

3.2.3. Employability

A second concern related to future employability, and whether being able to choose would result in students not gaining a range of skills, particularly in the presentation. There was concern expressed that students may not develop the standards of competence required in key skills in the social sciences. This view is supported by the Equality Act 2010, which states that exceptions to reasonable adjustments can be made on the basis of competence requirements of the qualification. However, the definition of what constitutes a ‘competence standard’ for any qualification must be developed carefully, to ensure the assessment expectations are not discriminatory (EHRC, Citation2015, p. 98). Thus, some staff and students suggested scaffolding and support for the development of skills could be preferable to enabling students to opt out of certain modes of assessment altogether:

‘However … it may not stretch or challenge people to improve on unfamiliar skills e.g. choosing multiple choice all the time over presentation – does that reflect working environments? Not really.’ (Lecturer)

3.2.4. Confidence in assessment design

Staff identified two key challenges to the proposed changes: confidence in designing varied assessment modes and workload pressures. Some responses raised the question as to whether staff possess the capacity to design a diverse set of assessment modes. Whilst 77% of respondents claimed that they were either ‘quite confident’ or ‘very confident’ in teaching a diverse range of learners, this figure fell to just over half (51%) for the level of ‘confidence in designing assessment for a diverse range of learners’. Twenty-nine percent of respondents felt that they were ‘not confident in designing assessment for a diverse range of learners’, meaning that there are a large proportion of staff members who would require additional training to facilitate the approach in practice. Staff (and some sympathetic students) were also concerned about additional work:

‘The weakness of that approach might be related to staffing in relation to increasing workloads for certain staff in terms of if you’ve got 4 types of assessment and how you actually come up with assessment criteria for each one.’ (Lecturer)

‘I don’t think we have procedures, policies, or protocols in place to deal with even what are relatively common additional needs.’ (Senior Lecturer)

4. Discussion

The theoretical frame of the social model of disability has enabled an examination of assessment from the perspective of barriers to learning. Rather than being an individual impairment issue, it has been identified in this study that it is the social organisation of HE institutions in terms of the processes, regulation and administration of assessment that creates significant barriers to the design and implementation of creative inclusive assessments and feedback. As Oliver and Barnes suggest, ‘Identifying institutional barriers to participation in education – in terms, for example, of the organisation and nature of the system of provision, the curriculum, pedagogy and assessment practice – is an urgent and crucial task demanding serious and systematic attention’.

There is increasing concern about the assessment and feedback processes in HE institutions in the UK (HEA, Citation2012; Sambell, Citation2016). Whilst general frameworks and guidelines can obviously support improvements across the sector, there is also a need to investigate further which students are dissatisfied and excluded from the traditional assessment processes employed in higher education institutions. In this study, some significant barriers to attainment in assessments for students with ALN were raised. Notably in the feedback students received which related to issues caused by their condition, such as dyslexic students receiving comments on structure, thus focusing more on the mode of delivery rather than the knowledge and comprehension of subject material.

In terms of the proposed change to assessment processes, there was overall support, particularly from students with an ALN, but with some reservations that would need to be addressed. Parity between the different modes of assessment would need to be proved to reassure students (and staff) that assessment processes were fair. This would involve bespoke marking criteria outlining the grade-level skills to be demonstrated. To enable this, further staff training on designing assessment would be required, to include designing for a diverse range of learners, rated poorly by staff in the survey. Student access to different modes of assessment to develop employability skills would also need to be systematically planned, and support provided for students in developing skills for each mode of assessment. This would be essential in ensuring that across a degree programme, students would get the opportunity to have both choices in assessment modes, and the opportunity to practice the required skills and competencies, receiving appropriate support and feedback to develop their potential. As Hockings (Citation2010) suggests, co-construction of the curriculum and assessment structure, involving staff and students, would support the development of individualised learning for all students, and would create an assessment process which was inclusive, designed for the ‘universal’ diversity of students, and in keeping with the social model of disability interpretation of education, and the Equality Act 2010.

In conclusion, inclusive assessment and feedback processes in Higher Education are essential if the diversity of our students is to be recognised, valued and supported. However, this needs to be balanced with the opportunity for students to develop a range of key skills and to be assured of fairness and equity. Within this context, pilots will be instigated at the programme level, co-constructed with students and with strong moderation processes. Two types of assessment will be offered within modules which are mapped to carefully designed learning outcomes, and designed to ensure that scaffolded completion of a range of types of assessment are assured. Therefore, choice in assessment methods will be designed with clear strategies for skills development, and appropriate levels of support within the school to enable students and staff to become confident and familiar with this approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the students and staff who participated enthusiastically in the project, and Cardiff University Centre for Education Support and Innovation for their keen support for the project and the potential inclusive outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ainscow, M. (1995). Education for all: Making it happen. Support for Learning, 10(2), 147–157. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9604.1995.tb00031.x

- Barajas, H., & Higbee, J. (2003). Where do we go from here? Universal design as a model for multicultural education. In J. Higbee (Ed.), Curriculum transformation and disability: Implementing universal design in higher education (pp. 285–292). Minnesota: Center for Research on Developmental Education and Urban Literacy, University of Minnesota.

- BERA. (2011). Ethical guidelines for educational research. London: Author.

- Boud, D. (1995). Assessment and learning: Contradictory or complementary? In P. Knight. (Ed.), Assessment for learning in higher education (pp. 35–48). London: Kogan Page.

- Charmaz, K. (2002). Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. In J.F. Gubrium & J.A. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research: Context and method (pp. 675–693). London: Sage.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Craddock, D., & Mathias, H. (2009). Assessment options in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(2), 127–140. doi:10.1080/02602930801956026

- EHRC. (2015). Equality Act 2010: Technical guidance on further and higher education. (Online). Retrieved from https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/equalityact2010-technicalguidance-feandhe-2015.pdf

- Entwhistle, N. (2000, November). Promoting deep learning through teaching and assessment: Conceptual frameworks and educational contexts. Conference Paper. Leicester: University of Leicester.

- Evans, C. (2013). Making sense of assessment feedback in higher education. Review of Educational Research, 83(1), 70–120. doi:10.3102/0034654312474350

- Evans, C. (2016). Evans Assessment Tool (EAT). Southampton: University of Southampton.

- Frederickson, N., & Cline, T. (2002). Special educational needs, inclusion, and diversity. Buckingham: OUP.

- Fung, D. (2017). A connected curriculum for higher education. London: UCL Press.

- Gomm, R., Hammersley, M., & Foster, P. (2000). Case study method. London: Sage.

- Hammersley, M. (1995). The politics of social research. London: Sage.

- HEA. (2012). A marked improvement: Transforming assessment in higher education. New York: Author.

- HEA. (2017a). Assessment and feedback in higher education. York: Author.

- HEA. (2017b). Assessment and feedback in higher education: A literature review for the higher education academy. (Online). Retrieved from https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/assessment-and-feedback-higher-education-1

- Hockings, C. (2010). Inclusive learning and teaching in higher education: A synthesis of research. (Online). Retrieved from https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/inclusive_teaching_and_learning_in_he_synthesis_200410_0.pdf

- Johnson, D.M., & Fox, J.A. (2003). Creating curb cuts in the classroom: Adapting universal design principles to education. In D.M. Johnson & J.A. Fox (Eds.), Curriculum transformation and disability: Implementing universal design in higher education (pp. 7–21). Minneapolis: Center for Research on Developmental Education and Urban Literacy, General College, University of Minnesota.

- Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research planner (3rd ed.). Geelong: Deakin University Press.

- Mann, S.J. (2001). Alternative perspectives on the student experience: Alienation and engagement. Studies in Higher Education, 26(1), 7–19. doi:10.1080/03075070020030689

- May, T. (2001). Social research: Issues, methods and process (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Open University.

- Norwich, B. (2002). Education, inclusion and individual differences: Recognising and resolving dilemmas. British Journal of Educational Studies, 50(4), 482–502. doi:10.1111/1467-8527.t01-1-00215

- O’Neil, G. (2017). It’s not fair! Students and staff views on the equity of the procedures and outcomes of students’ choice of assessment methods. Irish Educational Studies, 36(2), 221–236. doi:10.1080/03323315.2017.1324805

- Oliver, M. (1990). The politics of disablement. London: Macmillan Education.

- Pine, G. (2009). Teacher action research: Building knowledge democracies. London: Sage.

- Rose, D., & Sullivan, O. (1996). Introducing data analysis for social scientists (2nd ed.). Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Sambell, K. (2011). Rethinking feedback in higher education: An assessment for learning perspective. Bristol: ESCalate.

- Sambell, K. (2016). Assessment and feedback in higher education: Considerable room for improvement? Student Engagement in Higher Education, 1(1), 1–18.

- Saris, W.E., & Galhofer, I.N. (2007). Design, evaluation and analysis of questionnaires for survey research. New Jersey, NJ: Wiley and Sons.

- Seale, C., & Silverman, D. (1997). Ensuring rigour in qualitative research. The European Journal of Public Health, 7(4), 379–384. doi:10.1093/eurpub/7.4.379

- Stake, R.E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 443–454). London: Sage.

- UNESCO. (2009). Policy guidelines on inclusion in education. Paris: Author.

- Waring, M., & Evans, C. (2015). Understanding Pedagogy: Developing a critical approach to teaching and learning. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Waterfield, J., & West, B. (2006). Inclusive assessment in higher education: A resource for change. University of Plymouth. Retrieved from https://www.plymouth.ac.uk/uploads/production/document/path/3/3026/Space_toolkit.pdf

- Welsh Government. (2014). Inclusion and pupil support. (online). Retrieved from http://gov.wales/topics/educationandskills/schoolshome/pupilsupport/?lang=en