Abstract

The Institutional Grammar Tool (IGT) is an important and relatively recent innovation in policy theory and analysis. It is conceptualized to empirically operationalize the insights of the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework. In the last decade, political scientists have offered a number of applications of the IGT, mainly focused on disclosing and scrutinizing in-depth the textual configurations of policy documents. These efforts, involving micro-level analyses of syntax as well as more general classifications of institutional statements according to rule types, have underpinned empirical projects mainly in the area of environmental and common-pool resources. Applications of IGT are still in their infancy, yet the growing momentum is sufficient for us to review what has been learned so far. We take stock of this recent, fast-growing literature, analyzing a corpus of 26 empirical articles employing IGTs published between 2008 and 2017. We examine them in terms of their empirical domain, hypotheses, and methods of selection and analysis of institutional statements. We find that the existing empirical applications do not add much to explanation, unless they are supported by research questions and hypotheses grounded in theory. We offer three conclusions. First, to exploit the IGT researchers need to go beyond the descriptive, computational approach that has dominated the field until now. Second, IGT studies grounded in explicit hypotheses have more explanatory leverage, and therefore, should be encouraged when adopting the tool outside the Western world. Third, by focusing on rules, researchers can capture findings that are more explanatory and less microscopic.

1. Introduction

Public policy research in Western scholarship is increasingly dominated by the use of free-standing analytical frameworks. Most obviously, the field is shaped by the vision of Paul Sabatier and his colleagues. Their Theories of the Policy Process text (now in its fourth edition1) and the US-based Policy Studies Journal have been at the forefront of this policy theories agenda. Despite individual differences, there is a good deal of vitality around these theories of the policy process, and studies deploying and revising them abound. This empirical activity has driven questions concerning the reach and purpose of these approaches.

Thinking about the state of play in policy theory from the perspective of their application outside the Western world, two points strike us. First, there is no reason to silence the debate on a policy theory simply because it does not feature in the main textbooks or it is ignored by US-based outlets. Paul Sabatier was the first to acknowledge the potential of the French school of réferéntiel2 in a footnote of the first edition of Theories (1999: 157n15). Second, regardless of how popular is a theory in the West, there is the question of how well these theories fare in polities which are not Western liberal democracies. This second question has stimulated, for example, the growing literature on applications of the advocacy coalition framework in non-Western countries (see Han et al., 2014; Henry et al.3).

The readers of this journal interested in the two questions need a map of the current theories. Not every theory has the same status, at least in the West. Among these types, we find what we would call the big explainers (most obviously, Advocacy Coalition Framework [ACF] and Punctuated Equilibrium Theory [PET]—see Jenkins-Smith et al.,4 and Baumgartner et al.,5 respectively). These are the main contenders for the status of dominant theory of the policy process. Then we have the rising stars like the Narrative Policy Framework ([NPF]—see Shanahan et al.,6). Next are the theories that are knocking at the door claiming status as part of the conceptual canon such as policy learning (see Dunlop and Radaelli, 20187). And then, there is yet another category we could add—that of sleeping giants. Arguably, this category best describes the subject of this contribution—the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework.8 Despite being a rare instance of a governance framework that led its creator to a Nobel prize in economics (in 2009), the IAD’s complexity may have made it too daunting for widespread world-wide use.

Yet, things are changing fast. In 2011, Policy Studies Journal published the first dedicated special issue to IAD9 and since then, in the policy and environmental sciences literature, there are signs that the IAD giant may be awakening. This is likely to be due to scholars’ enduring ambition to conquer fresh analytical ground but it may also reflect the thorny questions concerning analytical reach of policy theories beyond Western settings, and their prescriptive potential. In fact, among all the major theories of the policy process, IAD may make the strongest claims to universality. Its focus on rules—both as they are written and used—as shaping and being shaped by human interactions ensures IAD is applicable beyond Western democracies (for an application to Chinese governance see Zhang).10 A global outlook marks out this research program11—notably in the first edition of Theories of the Policy Process12 Ostrom’s IAD chapter was the only one to report a significant number of applications beyond the West13 (for this observation see Sabatier14). In this contribution, our aim is simple. Rather than taking on the totality of the IAD and the many sub-frameworks it has inspired, we outline and review the empirical applications of one of the most adaptable and policy-relevant aspects of IAD inspired work—the Institutional Grammar Tool (IGT). Before we get started, a few wider words of introduction to the IAD are in order.

Based on the work of Elinor and Vincent Ostrom,15 and developed over four decades with their various collaborators, IAD seeks to offer a common language of how actors’ behavior is framed, guided and constrained by institutions.16 Institutions in the IAD are rules, or governing arrangements, they form the ‘worlds of action’ (Kiser and Ostrom, 198217) which are the backdrop for political action. Although the approach has evolved, the original vision put forward by Ostrom was to contribute to institutional rational choice.18 It was this rational choice orientation that led her to examine collective action through the analysis of rules.

In ‘action situations’, individuals have roles and take decisions drawing on the information available to them. Concerned with collective action dilemmas, zooming-in on the action situation and its key decision points, IAD focuses on the ways in which rules—in-form or in-use—shape the alignment of individual and collective interests. Following the traditional approach to policy sciences marked by Lasswell’s prescriptive agenda,19 the IAD is motivated by a strong policy design imperative. By understanding the how and why of institutional design we can make adjustments to improve institutional performance.

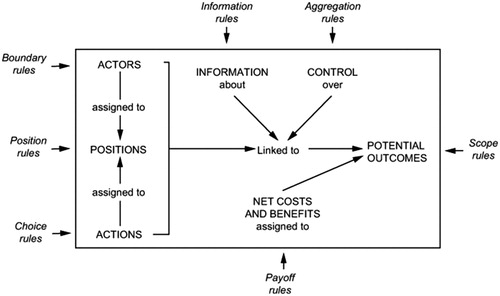

To understand why certain governing arrangements have come about, and how they shape political outcomes, we need tools to examine these action situations. This is what the so-called IGT was designed for and therefore it is our central focus. Specifically, we are interested in the conceptualization which breaks down the action situation into seven rule types—position, boundary, choice, aggregation, information, payoff and scope (see Figure ).20 Each rule marks a key moment of actor interaction and interdependence in a political setting (see Table 6.1).21 These are moments where authority is prescribed, and used by particular policy participants. The key promise of such universal rules, which can operate at various levels of abstraction (see Figure 6.3 in Schlager and Cox,22 and empirically Hardy and Kootnz, and Schlager and Heikkila),23 is comparability of cases across space and time. This approach to institutional rules has connections with Fritz Scharpf’s24 actor-centered institutionalism. But, while Scharpf was concerned with a limited number of games and ideal-types of interaction among purposeful actors, the IGT is wider and more forensic. To see this, we turn to the grammatical component of the IGT.

Figure 1. IGT rule types. Source: Crawford and Ostrom.64

The grammatical component is known by the acronym ADICO—which stands for Attributes, Deontic, aims, Conditions and Or else. Originally presented by Crawford and Ostrom,25 and later developed by Ostrom in her 2005 volume Understanding Institutional Diversity,26 ADICO is intimately connected to the structure of rules. In this schema,27 the content of the seven rules types can be identified using the ADICO grammatical components. Thus, each rule (should) tells us who carries an action (i.e. the actors involved in an institutional arrangement—A); whether the action is possible, permitted, mandatory, can or should happen (i.e. the degree of stringency of the action, typically expressed by the prescriptive operator added to a statement—D); the action itself available to the actors (I); under which conditions actions take place (i.e. annually, by date, after a vote, etc.—C); and finally what happens if what is prescribed, suggested, mandated or incentivized by the rule does not happen (i.e. citizens may go to court, or there are ways to file a complaint—O). The sentence below exemplifies how a given institutional statement can be dissected via ADICO:

An example of the application of this syntax is “You must stop your car at a red light or the police officer will give you a traffic ticket.” Attribute = “you”; deontic = “must”; aim = “stop your car”; condition = “at a red light”; or else = “the police officer will give you a traffic ticket”.28

Using this IGT—rule types and their grammar—we have both a universal language and toolkit to analyze the environment people operate in and ultimately get at the why and how of institutional design. Yet, IGT analysis is not for the faint-hearted. As the reader will gather, to reap the considerable rewards of comparability, we must be willing to conduct a forensic examination of the empirics. Proceed only if holding the hand of an experienced operative is the common refrain in the IAD state of the art pieces;29 so we must handle with care and all due humility. For it is becoming increasingly difficult to resist and increasing efforts are being made to de-mystify the IGT.30

This article is organized as follows. We introduce our research questions, methods and the corpus of articles selected for the task in Section 2. Section 3 presents the main findings, before we discuss their implications in Section 4 and provide three conclusions in Section 5.

2. Research questions, methods, corpus

The research questions that lead our analysis of the literature are:

What are the predominant journals, countries and empirical topics have they been answered so far?

How has the literature evolved over time?

How is the IGT aligned with the research design of the empirical study? IGT can be used to inform theory, to test rival alternative hypotheses, to measure, to describe, and so on.

To address these questions with a suitable corpus, we carried out a literature search for empirical articles using ISI Web of Science.31 Ultimately, we were left with a sample of 30 articles for our final sift from which a further four were rejected. Crawford and Ostrom32 is, of course, the main foundation of this literature. It is not empirical and so, notwithstanding its fundamental role, we do not include it in our corpus. The work by Smajgl et al.33 is frequently cited but it deals with agent-based simulations rather than empirical cases. The same holds true for Schulter and Theesfeld.34 We found McGinnis35 very instructive for definitions and conceptual clarifications—however, it does not contain empirics. During the preparation of this article, we came across a very interesting study on the semi-automated extraction of rules by Heikkila and Weible36—however, this article was not available in early view at the time we carried out our analysis, hence we did not use it here. In total, we ended up with a corpus of 26 articles (see Appendix 1).

3. Analysis of the literature

3.1. What are the predominant journals, countries and empirical topics have they been answered so far?

The importance of IGT analysis is shown by the fact that the corpus appears both in public policy/public administration (PP/PA) journals as well as in journals dedicated to specific sectors such as environment, urban affairs, water, and health (Table ). The PP/PA journals are more frequent in the distribution of the corpus than the journals dedicated to sectors. Seven authors are the most prolific—Basurto, Carter, Heikkila, Siddiki, Watkins, Weible and Westphal. They account for exactly half the papers in our corpus (13 articles). Notably, Policy Studies Journal, one of the top-ranked journals in the ISI’s Public Administration and Political Sciences rankings (10th out of 47 and 18th out of 169 respectively in the 2017 ISI [JRC, 2018]), stands out as the central outlet for this type of research (6 articles). The main research questions concern governance and more precisely common-pool-resource (CPR)-related puzzles. Consequently, the empirical topics in the domain of environmental policy, urban policy problems, and human geography dominate (Table ). Despite the portability of the approach beyond Western contexts, USA-focused cases still dominate comprising 18 of the 26 articles (with Weible’s location of Colorado the top state by far—5 studies). Yet, the presence of Mexico, Nicaragua, Nepal and Pakistan may be indicative of more global impact to come and reassures that IAD is suitable for ontological realities of non-Western systems.

Table 1. IGT outlets and authors.

Table 2. IGT countries and sectors.

3.2. How has the literature evolved over time?

The literature is obviously recent (recall our search runs from 2008 to 2017) yet the corpus may show the beginnings of some patterns. Crawford and Ostrom’s37 original propositions are clear in their conceptual depth, yet they provide limited operational guidance on the transition between rule grammars in the abstract and empirical applications. Part of the increase in IGT research is rooted in attempts to meet this challenge. Siddiki et al.,38 examining the aquaculture sector in Colorado, is one of the first manifestations of this transition. This example aims to be completely faithful to the theoretical claims put forward by Crawford and Ostrom.39 In fact, Siddiki et al.40 apply ADICO in a surgical way. For them, each statement—drawn from policy documents (N = 346 statements) and legislation (N = 35 statements)—is a data point. Hence, the operational guidance is to count the number of institutional statements that are present in a given rule or law. Then, each of these statements is dissected according to ADICO. The end result of this exercise is twofold: on the one hand, a frequency count and on the other hand a configurational analysis (2011: 92–93, 95–98). Though Siddiki et al.41 provide perhaps the most faithful operationalization of IGT, this first application has given way to a variety of approaches: from this disciplined computational approach to more eclectic strategies. This is a sure sign that the field is opening up, though one may argue that the most recent literature is missing the whole point of a disciplined, forensic approach to institutional statements.

In fact, the story of empirical IGT articles suggests that the most recent contributions (those published since the 2011 Policy Studies Journal special issue) have moved towards increasingly complex reconstructions of the action situation via the extraction of rules and their categorization according to rule types. Thus, we see more open approaches to IGT, and also a move away from examining ADICO as set of institutional statements to the meso-category of the action situation based on the categories of rules identified by Crawford and Ostrom.42

The early enthusiasm for the IGT was channeled via its core computational tools, ADICO. Arguably, this happened because it is conceptually easy to grasp ADICO and follow its instructions. But the IGT is wider—actually in our presentation above we started from rules and then we zoomed on ADICO, the opposite of what Ostrom did. For instance, the institutional edifice of the IGT contains also the distinction between norms, rules, and strategies. Yet, before the PSJ special issue (see, for instance, Basurto et al.43) and also in the context of the SI, ADICO is practically the only tool (in our corpus at least) deployed by the researchers and mainly computationally. Then, after the relative uptake of the methodology, the same authors that popularised IGT started enlarging their scope by complementing and enriching ADICO with rule types categorization, that in our view strengthens the explanatory potential of the analysis (Espinosa44 is a good example of the turn from ADICO as the only concern of empirical analysis to the analysis of rules via ADICO). In other words, the literature seems to have overcome its preoccupation with getting the instructions given by Ostrom and Crawford ‘right’ and applying ADICO in the ‘correct way’.

This evolution also shows up in the data types and methods being used by social scientists. In terms of data, what is important in the context of IGT is the mix between those articles analysing only rules-in-form—i.e. those codified words found in the formal policy documents—and those including rules-in-use—i.e. as norms that are perceived or understood by policy actors in practice (this, of course, echoes March and Olsen’s, ground-breaking distinction between old and new institutions [1984]). In our corpus we find a healthy mix—15 articles go for the rules-in-form, and the remaining 11 focus on those in-use either alone or in combination with those in-form (see Table ). On the methods front, we see the usual suspects of public policy research. Yet, what is missing is perhaps more interesting: IGT’s promise is to focus on multi-actor, multi-rule environments where the logic of action is contextual and configurational (i.e. the result of the rule mix in a particular place and time). And yet, so far, we observe only one use of configurational analyses.45 The configurational analysis draws on Boolean algebra. It identifies the combinations of necessary and sufficient conditions that are related to the outcome of interest, effectively drawing on the logic of case-oriented research.

Table 3. Data and method mixes.

3.3. How is the IGT aligned with the research design of the empirical study?

Theories. IAD is a conceptual vehicle for the operationalization of rule analysis. As such, it is compatible with many social science theories. The articles in our sample are a mix of a-theoretical types—aim only to develop a deep empirical understanding of an issue—and studies with theoretical ambitions. Of this latter category, we might reasonably expect many to reflect Ostrom’s economic approach and IAD’s focus on overcoming collective action dilemmas—Transaction Cost Analysis (TCA), game theory and common pool resources are all common theoretical partners.46 However, none of the articles restrict themselves to the rational model of human choice (beyond perhaps Novo and Garrido47 who use the Social-Ecological Systems [SES] framework with IGT). In fact, we observe theoretical pluralism in the literature with more than half (N = 14) of the articles going beyond economic-inspired approaches to more traditional public policy ideas—notably, theories of implementation and compliance; regulation; policy design; local autonomy; collaborative governance and conflict resolution.

Empirical/theoretical/normative focus. We can add a follow-up question to the previous remark—what do they do with these theories? (How) do they use theory to align IGT to the empirical study? When it comes to this question, an important distinction revolves around the empirical/theoretical divide. Nine of the articles work to specific hypotheses.48 One is an explicitly normative piece;49 this is a little surprising given the strong prescriptive vision of Ostrom. We might expect more to come with work evaluating the effectiveness, efficiency, and accountability dimensions of institutional arrangements. The rest of our corpus (N = 16) are what we term exploratory or descriptive accounts that forensically examine institutional design (usually comparative in a case study). Given the descriptive nature of the ADICO framework, especially if used in computational mode, the absence of hypotheses seems to mute the explanatory leverage of the empirical analysis.

That said, we should not assume that those contributions that fall into this second category are unsophisticated. An example is Basurto et al.,50 whose empirical analysis illustrates the concept of holons, that is, statements that work both as an entire system on their own and as part of a larger system. The two legislative policies studied in that article are not compared but used as parallel examples in the deployment of the claims and arguments. This article also aligns the IGT with the research design of nested analysis. The latter is explained as follows:

Given that the grammar of the policy partly determines the number of units coded, the next challenge is how to aggregate and analyze nested units in a way that conveys meaning and removes the artificiality from the coding scheme. The method of nesting might reflect a number of priorities, such as the research question(s) or the scale at which the researchers wish to draw conclusions. Once the institutional statements are nested and combined into a collection of institutional statements, those configurations are then analyzed and become the new units for analysis.51

The notion of nested analysis is promising for research design but only if there are explicit hypotheses about the nested structure—unfortunately, the article in question is not hypotheses-driven and does not provide suggestions.

Hypotheses. Espinosa52 captures an important point when he observes that the aim of IGT analysis should be to test ‘solid hypotheses about the connection between the syntax of a regulatory design and the response of the subjects that the regulation is targeting’.53 Arnold and Fleischman54 test the conventional hypothesis that an ambiguous mandate causes fragmented, fractured implementation—interestingly, the empirical analysis does not corroborate this proposition. Looking at irrigation systems in Nepal, Bastakoti and Shivatoki55 align their IGT analysis with three research questions that are characteristics of Ostrom’s approach to Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD). These questions are partly descriptive (question a) and partly explanatory—(a) how does rule formation vary across irrigation systems (b) is rule formation influenced by diversity in biophysical characteristics of the irrigation system and community attributes (c) how do rule enforcement mechanisms affect performance and collection action? Hardy and Koontz56 have a similar range of classic IAD hypotheses.

Setting of the studies. Another important distinction is that most of the empirical analyses are carried out in a given, often micro-setting, such as aquaculture in Colorado, certain features of tobacco legislation in Mexico, or irrigation systems in Nepal (see Table ). Within a carefully controlled context, IGT and ADICO, in particular, seem to perform well. The challenge is to scale up to comparative analysis. Possibly, one efficient option is to draw on explicit hypotheses and move from the micro-descriptive approach to ADICO to the meso-level of rules and action situations. This is a bold proposition and admittedly little more than a conjecture.

Findings. One final word on the ‘final product’ of these empirical analyses. What do the readers really get in terms of hard findings? In some cases, there is little more than frequencies, word-counts, and flowcharts to explain how the institutional grammar operates. To put it differently, the final product is an illustration of the design of a policy or a regulation. With a hint of skepticism, one could observe that any lawyer or practitioner active in the policy field has probably the same kind of flowchart-mapping in their mind, and does not need to count the frequency of, for example, deontics to draw conclusions about how an institutional arrangement fares in terms of stringency and obligations. In other more mature articles, the reader is offered design based on theories and findings that speak to a range of hypotheses, corroborating or rejecting them (see, crucially, Espinosa57). These are of course the more valuable findings that shed light on different explananda such as governance arrangements, regulatory compliance and implementation patterns.

4. Drawing lessons

As mentioned, the IGT literature is quite recent and, as far as we know, this is the first attempt to take stock and look at the empirical articles together. We have already mentioned that the articles with empirical content often adopt ADICO as the main analytical device, however, this drive towards ADICO and its variations is problematic. On the one hand, the most robust theoretical justification for the adoption of ADICO leads to the classification of all institutional statements contained in a document, rule or law. This, however, leads researchers to slice up the relevant text in the ADICO form, without having a sense of how the slices work together. The high number of statements analyzed this way directs scholars toward a computational or arithmetic approach to ADICO, where mere counting limits a deeper understanding of the grammar of institutional action. Even in the extremely limited case of different regulations/guidelines that govern the aquaculture sector in Colorado, the authors explicitly acknowledge that ‘[c]onditions were not included within this [frequency] analysis because this field contained a lot of information that varied significantly between statements’ and ‘[a] frequency count of aims was conducted, but due to the high amount of variability between statements, the results are not presented here’.58 Imagine trying to scale up to a comparative project. Here, the problem is not computational, rather it is interpretative: how to make sense of a very high number of ADICO statements beyond frequency distributions and descriptive analysis.

On the other hand, if we choose to follow ADICO as rationale and approach, and we select some key provisions in a text (imagine a law for example), we risk selection bias. We will have a more parsimonious number of data, but with the risk of censoring statements that may tell us something important. One possible way out of the paradox was already offered by Elinor Ostrom:59 it is the move from ADICO towards the extraction of rules. Rules are themselves empirically contained in institutional statements. Thus, for example, if we take a Freedom of Information Act, we need a limited number of articles and clauses to identify position, boundary, choice, aggregation, information, payoff and scope rules. If researchers are not simply interested in capturing the frequency of actors, aims, conditions and so on, the identification of rules is a relatively parsimonious way to articulate the action situation. And rules can then be decomposed in ADICO terms—recall that rules contain all the ADICO elements, in contrast to norms (ADIC) and shared strategies (AIC).

What lessons can we draw from the remark made above? Going back to the point about the evolution of the literature since the PSJ special issue, IGT-informed empirical research has moved toward the integration of the institutional grammar with the categorization of the seven rule types. This is because the analysis of rules captures the essence of the action-situation. Of course, rules are just special types of institutional statements—indeed if researchers extract rules they are extracting all the five elements of ADICO.60

5. Discussion and conclusions

Elinor Ostrom and her colleagues have provided a formidable actor-centered institutional approach, the IAD. It has an obvious appeal to researchers, like us, who are interested in regulation and governance, especially if we consider the empirical applications of the IGT. However, the literature on the empirical applications of the IGT is still in a nascent phase. Ours is an early attempt to take stock of what has been done in these empirical applications. Considering the audience of this journal, what are the main points to bear in mind in our discussion of how to use the IGT and what are the lessons learned from the literature?

We would not encourage an exclusive focus on ADICO. Our first conclusion of the literature review is that the corpus of empirical articles we have examined contains a good number of detailed, meticulous applications of the IGT informed by ADICO. The computational approach to ADICO fares well in terms of coherence with the aims and rigor of the IAD. However, it runs the risk of being rather low on explanatory leverage. This is possibly one reason why the empirical studies of the most recent years have scaled up on ambition, for example, looking at rules and rule typologies instead of simply computing all instances of attributes, deontics, and the other ADICO elements of the grammar. It makes sense to start with the grammar but only inasmuch it is used to capture the whole action situation—thus ADICO is absolutely fine, indeed necessary, in an empirical study if it supports an analytical framework where rules, norms and strategies have their place.

What about comparability? ADICO is mostly efficient as tool for in-depth, within-case investigation, and not for comparative analysis. A number of articles that use ADICO, whether for descriptive or comparative purposes, narrow down their scope to the D and O components as, admittedly, the degree of heterogeneity of Attributes, aIms (actions) and Conditions is too large across policy documents belonging to the same country and policy area to allow for meaningful comparisons.61 ADICO may be helpful in comparing legal stringency (D and O components), but only if a computational perspective is adopted (i.e. counting the prescriptive operators—see for example, Basurto et al., 2011).62 Yet, this computational approach applied to deontic operators seems to be of little relevance if we are dealing with hard laws in different countries. Imagine that we are comparing the Freedom of Information Act in the UK (a relatively long piece of legislation) and in Austria (a thin legislative act). What would we make of a long list of statements drawn by the UK and a short list for Austria? Moreover, deontics can simply refract different legislative traditions: lawmakers in one country prefer to use ‘shall’ and ‘must’, whilst in other countries, the tradition may well be to use ‘will’ or ‘can’. But, the meaning of the institutional grammar in practice may be the same.

The notion of applying IGT to administrative procedures is not visible in our corpus. This paves the way for a new phase of empirical applications of the IGT, given the important of administrative procedures for policy researchers. The non-Western world is a fabulous laboratory of administrative systems with different legal origins (some inspired by European models) and purposes (for example, to support a liberal democracy or other types of political systems). At the moment, however, most of the articles employing IGT-informed approaches deal with the governance of CPRs (in line with the research interests of Ostrom and her workshop). As a result, the texts to which ADICO/IGT is applied do not resemble legal acts (sometimes even informal/uncodified rules and interview data are dissected with ADICO). Even the application of the tool to full-blown regulations outside the scope of environmental regulations is rather rare,63 let alone its use for primary legislation (which is documented only once64). In short, there are a lot of intellectual rewards for policy researchers willing to extend this type of analysis to administrative procedures and even more widely legislation.

The second conclusion is that the articles that are more computational and frequencies-oriented do not tell us much beyond the particular, very specific issues posed by a given policy design in a certain, often micro, context. Without explicit hypotheses, the IGT tilts towards description. For us, this is a problem, especially if we wish to encourage the readership of this journal to extend IGT usage beyond the Western world.

There are also problems of interpretation and conceptual relevance of the data. To follow the ADICO protocol in its computational version means coding hundreds, at times thousands, of institutional statements. The identification of statements, particularly if we are working with one or more legal acts, does not provide a systematization and a more in-depth understanding.

Consider again the case of analyzing Freedom of Information Acts (FOIA) in a region like Europe through ADICO. In this case, ADICO generates a sort of ‘explosion’ of the individual legal acts rather than their systematization. In the UK FOIA, for instance, we have an appendix listing hundreds of attributes (i.e. public bodies subject to Freedom of Information discipline). Collecting them all into the ‘A’ column of an ADICO table is not informative, most of all if the purpose of the data collection is comparative across countries. Instead, it seems more useful to approach the Acts in terms of position and boundary rules, and then compare these rules structures across countries. This provides a sharper analytical snapshot, based on the myriad of ADICO pixels, yet capable of extracting patterns from these pixels.

In fact, to explain FOIAs comparatively, we need to know what public bodies are exempted from its discipline (boundary rules) rather than looking at a huge list of covered bodies. And for the sake of obtaining this crucial data on exempt bodies, ADICO may be silent. In fact, ADICO would lead us to attributes (who carries out the action) leaving to our imagination to figure out that we need to re-interpret ‘attributes’ as ‘who does not carry out the action’. Boundary rules are more straightforwardly sending us the right direction because they would rightly point us towards bodies exempted from FOIA. Hence, the problem today is not to compute high volumes of statements, but to extract meanings, interpretations, or simply patterns that make sense beyond the computational exercise.

Vis-à-vis this problem, we take comfort in our third conclusion, based on the observation that after an initial period the IGT studies seem to become more open, and consider the IGT is different ways. In particular, the move from the disciplined application of ADICO to the ‘meso-level’ of rules seems to increase the explanatory leverage—again, especially in the context of comparative analysis. One important lesson in this direction comes from the articles in the corpus that make a strong case for adopting explicit hypotheses that can be tested by comparing types of rule across different legal texts. We illustrate this point with one example from our own work in the Protego project.65 In Protego we have hypotheses about how different combinations of regulatory procedures trigger accountability towards different stakeholders and core interests, and the IGT provides a theory-informed way to collect data suitable for comparison according to a single template (based on rules types) that can travel across different countries, languages and legal cultures.

Our three conclusions question the utility of designing research based exclusively on the hard-core computational ADICO methodology, especially if we wish to examine constructs such as administrative procedure or legal texts covering a sector (for example, bans of tobacco smoking, or legislation of shale gas extraction). The IGT is a formidable approach, but if its purpose is to compare legislation or policies grounded in legislation across countries, it is inefficient to reduce it to a computational ADICO. To conclude, the challenge for researchers willing to adopt and extend IGT is to capture the meso level and to go beyond the description of policy design by formulating substantive, theory-driven conjectures.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.3 KB)Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this article were presented at: the European Consortium of Political Research (ECPR) Regulatory Governance 7th biennial conference, University of Lausanne 4–6 July 2018, the ECPR general conference, Hamburg University 22–25 August 2018, the International Workshop on New Theories of Governance as Governing, Zhejiang University 8–9 October 2018 and the Institutional Grammar Analytics Workshop, Syracuse University 19–20 October 2018. We are grateful to all the participants of these events for their criticisms and comments. We benefited from many colleagues’ insights and extend particular thanks to Peter John, B. Guy Peters, Liz Richardson, Yongdong Shen, Saba Siddiki, Veronique Wavre, Jianxing Yu, Chris Weible and Haoxin Zhou. Biggest thanks must go to our special issue editors—Sujian Guo and Gerry Stoker for bringing this volume together.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Claire A. Dunlop

Claire A. Dunlop is Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the University of Exeter, UK. A public policy and administration scholar, her main fields of interest include the politics of expertise and knowledge utilization; risk governance; policy learning and analysis; impact assessment; and policy narratives.

Jonathan C. Kamkhaji

Jonathan C. Kamkhaji is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Exeter, UK. His research interests include political economy, public and regulatory policy and European Union integration. He currently works as data steward for the advanced ERC project PROTEGO (Procedural tools for Effective Governance).

Claudio M. Radaelli

Claudio M. Radaelli is Professor of Public Policy at University College London (UCL), UK. His research interests lie in the field of policy learning, regulatory accountability, and the effects of regulatory reforms. He was awarded two advanced grants by the European Research Council, the most recent one on Procedural Tools for Effective Governance (PROTEGO, with Claire Dunlop as co-PI).

Notes

1 Weible and Sabatier, Theories of the Policy Process.

2 Jobert and Muller, L’Etat en Action.

3 Han and Unger, “Policy Advocacy Coalitions as Causes,” 313–334; Henry et al., “Policy Change in Comparative Contexts,” 299–312.

4 Jenkins-Smith et al., “The Advocacy Coalition Framework,” 135–172.

5 Baumgartner et al., “Punctuated Equilibrium Theory,” 55–102.

6 Shanahan et al., “The Narrative Policy Framework,” 173–214.

7 Dunlop and Radaelli, “Does Policy Learning Meet the Standards,” S48–S68.

8 Ostrom, “Institutional Rational Choice,” 35–72; Ostrom, Understanding Institutional Diversity.

9 Blomquist and deLeon, “The Design and Promise of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework,” 1–6.

10 Zhang, Governing the Commons in China.

11 Heikkila and Cairney, “Comparison of Theories of the Policy Process,” 301–328.

12 Sabatier, Theories of the Policy Process.

13 Ostrom, “Institutional Rational Choice,” 21–64.

14 See note 14 above, 11.

15 Ostrom and Ostrom, “Public Choice,” 203–216.

16 Schlager and Cox, “The IAD Framework and the SES Framework,” 215.

17 Ostrom, “Institutional Rational Choice.”

18 Kiser and Ostrom, “Does Policy Learning Meet the Standards,” 179–222.

19 Lasswell, “The Emerging Conception of the Policy Sciences,” 3–14.

20 Ostrom, Understanding Institutional Diversity; Ostrom, “Institutional Rational Choice,” 29–30.

21 See note 16 above, 219–220.

22 Ibid, 232.

23 Hardy and Koontz, “Rules for Collaboration,” 393–414; Schlager and Heikkila, “Resolving Water Conflicts,” 367–392.

24 Scharpf, Games Real Actors Play.

25 Crawford and Ostrom, “A Grammar of Institutions,” 582–600.

26 Ostrom, Understanding Institutional Diversity.

27 Ibid, chapter 7.

28 Basurto et al., “A Systematic Approach to Institutional Analysis,” 523–537.

29 Heikkila and Andersson, “Policy Design and the Added-Value of the Institutional Development Framework,” 309–324; Schlager and Cox, “The IAD Framework and the SES Framework,” 215–252.

30 Heikkila and Andersson, “Policy Design and the Added-Value of the Institutional Development Framework,” 309–324; McGinnis, “An Introduction to IAD and the Language of the Ostrom Workshop,” 169–183.

31 We conducted four searches in the ISI Social Science Citation index on 31 October 2017 for articles only using the following criteria: Topic = Institutional AND grammar AND tool = 16 articles, Topic = Institutional AND grammar = 100 articles, Topic = Adico = 8 articles, Topic = Institutional AND analysis AND development = 7702 articles, refined searching ‘grammar’ = 21 articles. This produced an initial sample of 145 articles. 115 were rejected from this sample as either duplicates (41), not relating to IAD in the political science sense, only name-checked IGT or Adico and / or were entirely non-empirical (74). See Appendix 1 for our final sample of 26 articles.

32 See note 25 above.

33 Smajgl et al., “Modeling Endogenous Rule Changes in an Institutional Context,” 199–215.

34 Schlüter and Theesfeld, “The Grammar of Institutions,” 445–475.

35 McGinnis, “An Introduction to IAD and the Language of the Ostrom Workshop,” 169–183.

36 Heikkila and Weible, “A Semiautomated Approach to Analyzing Polycentricity,” 308–318.

37 See note 25 above

38 Siddiki et al., “Dissecting Policy Designs,” 79–103.

39 See note 25 above.

40 See note 38 above.

41 Ibid.

42 See note 25 above.

43 Basurto et al., “A Systematic Approach to Institutional Analysis,” 523–537.

44 Espinosa, “Unveiling the Features of a Regulatory System,” 616–631.

45 Schlager and Heikkila, “Resolving Water Conflicts,” 367–392.

46 See note 16 above.

47 Novo and Garrido, “From Policy Design to Implementation,” 1009–1030.

48 Arnold and Fleischman, “The Influence of Organizations and Institutions on Wetland Policy Stability,” 343–364; Feiock et al., “Capturing Structural and Functional Diversity through Institutional Analysis,” 129–150; Hardy and Koontz, “Rules for Collaboration,” 393–414; Kamran and Shivakoti, “Comparative Institutional Analysis of Customary Rights and Colonial Law in Spate Irrigation Systems of Pakistani Punjab,” 601–619; Mattor and Cheng, “Contextual Factors Influencing Collaboration Levels and Outcomes in National Forest Stewardship Contracting,” 723–744; Schlager and Heikkila, “Resolving Water Conflicts,” 367–392; Siddiki, “Assessing Policy Design and Interpretation,” 281–303; Siddiki et al., “Using the Institutional Grammar Tool to Understand Regulatory Compliance,” 167–188; Weible and Carter, “The Composition of Policy Change,” 207–231.

49 Clement et al., “Authority, Responsibility and Process in Australian Biodiversity Policy,” 93–114.

50 See note 43 above.

51 Ibid., 528, 532, 535.

52 See note 44 above.

53 Ibid., 619.

54 Arnold and Fleischman, “The Influence of Organizations and Institutions on Wetland Policy Stability,” 343–364.

55 Bastakoti and Shivakoti, “Rules and Collective Action,” 225–246.

56 Hardy and Koontz, “Rules for Collaboration,” 393–414.

57 See note 44 above.

58 See note 38 above, 92, 94.

59 See note 26 above.

60 A corollary of this is that one should not do both ADICO and RULES, as one is perfectly suitable to give you the information contained in the other. But, the perspective changes with rules towards the action situation. In particular, rule types shed light on this aspect.

61 Carter et al., “Integrating Core Concepts from the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework for the Systematic Analysis of Policy Designs,” 159-185; Siddiki et al., “Dissecting Policy Designs,” 92–94.

62 See note 43 above.

63 Espinosa, “Unveiling the Features of a Regulatory System,” 616–631; Siddiki and Lupton, “Assessing Nonprofit Rule Interpretation and Compliance,” 156–174; Weible and Carter, “The Composition of Policy Change,” 207–231.

64 See note 38 above.

65 Our European Research Council (ERC) project on Procedural Tools for Effective Governance (PROTEGO) arises out of a fundamental claim: the design and combinations of procedural regulatory instruments have causal effects on the performance of political systems, specifically on trust in government, control of corruption, sustainability and ‘doing business’. The key mechanism in this causal relation is accountability to different types of stakeholders. PROTEGO provides a theoretical rationale to capture the accountability effects by adopting an extension of delegation theory that considers multiple stakeholders. The theoretical framework allows us to test the observable implications of the framework on outcomes that are crucial to the performance of political systems. Empirically, this research programme has generated data across the EU and its 28 Member States for the period 2000–2017 on administrative procedure acts, freedom of information, notice and comment, judicial review of rulemaking, regulatory impact assessment, and Ombudsman procedures.

66 See note 25 above.

References

- Arnold, G., and F. D. Fleischman. “The Influence of Organizations and Institutions on Wetland Policy Stability: The Rapanos Case.” Policy Studies Journal 41, no. 2 (2013): 343–364. doi:10.1111/psj.12020.

- Bastakoti, R. C., and G. P. Shivakoti. “Rules and Collective Action: An Institutional Analysis of the Performance of Irrigation Systems in Nepal.” Journal of Institutional Economics 8, no. 2 (2012): 225–246. doi:10.1017/S1744137411000452.

- Basurto, X., G. Kingsley, K. McQueen, M. Smith, and C. M. Weible. “A Systematic Approach to Institutional Analysis: Applying Crawford and Ostrom’s Grammar.” Political Research Quarterly 63, no. 3 (2010): 523–537. doi:10.1177/1065912909334430.

- Baumgartner, F. R., B. D. Jones and P. B. Mortensen. "Punctuated Equilibrium Theory: Explaining Stability and Change in Public Policymaking". In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Christopher M. Weible and Paul A. Sabatier, 55–102. 4th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2017.

- Blomquist, W., and P. deLeon. “The Design and Promise of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework.” Policy Studies Journal 39, no. 1 (2011): 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00402.x.

- Carter, D. P., C. M. Weible, S. N. Siddiki, and X. Basurto. “Integrating Core Concepts from the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework for the Systematic Analysis of Policy Designs: An Illustration from the Us National Organic Program Regulation.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 28, no. 1 (2016): 159–185. doi:10.1177/0951629815603494.

- Clement, S., S. A. Moore, and M. Lockwood. “Authority, Responsibility and Process in Australian Biodiversity Policy.” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 32, no. 2 (2015): 93–114.

- Crawford, S. E. S., and E. Ostrom. “A Grammar of Institutions.” American Political Science Review 89, no. 3 (1995): 582–600. doi:10.2307/2082975.

- Dunlop, C. A. and C. M. Radaelli. “Does Policy Learning Meet the Standards of an Analytical Framework of the Policy Process.” Policy Studies Journal 46, no. S1 (2018): S48–S68. doi: 10.1111/psj.12250.

- Espinosa, S. “Unveiling the Features of a Regulatory System: The Institutional Grammar of Tobacco Legislation in Mexico.” International Journal of Public Administration 38, no. 9 (2015): 616–631. doi:10.1080/01900692.2014.952822.

- Feiock, R. C., C. M. Weible, D. P. Carter, C. Curley, A. Deslatte, and T. Heikkila. “Capturing Structural and Functional Diversity through Institutional Analysis: The Mayor Position in City Charters.” Urban Affairs Review 52, no. 1 (2016): 129–150. doi:10.1177/1078087414555999.

- Han, H., Swedlow, B. and D. Unger. “Policy Advocacy Coalitions as Causes of Policy Change in China? Analyzing Evidence from Contemporary Environmental Politics.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 16, no. 4 (2014): 313–334. doi:10.1080/13876988.2013.857065.

- Hardy, S., and T. M. Koontz. “Rules for Collaboration: Institutional Analysis of Group Membership and Levels of Action in Watershed Partnerships.” Policy Studies Journal 37, no. 3 (2009): 393–414. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2009.00320.x.

- Heikkila, T. and C. M. Weible. "A Semiautomated Approach to Analyzing Polycentricity". Environmental Policy and Governance 28, no. 4 (2018): 308–328. doi:10.1002/eet.1817.

- Heikkila, T. and K. P. Andersson. “Policy Design and the Added-Value of the Institutional Development Framework.” Policy & Politics 46, no. 2 (2018): 309–324. doi:10.1332/030557318X15230060131727.

- Heikkila, T. and P. A. Cairney. "Comparison of Theories of the Policy Process." In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Christopher M. Weible and Paul A. Sabatier, 301–328. 4th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2017.

- Henry, A. D., K. Ingold, D. Nohrstedt, and C. M. Weible. “Policy Change in Comparative Contexts: Applying the Advocacy Coalition Framework Outside of Western Europe and North America.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 16, no. 4 (2014): 299–312. doi:10.1080/13876988.2014.941200.

- Jenkins-Smith, H. C., D. Nohrstedt, C. M. Weible, and K. Ingold. "The Advocacy Coalition Framework: An Overview of the Research Program". In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Christopher M. Weible and Paul A. Sabatier, 135–172. 4th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2017.

- Jobert, B., and P. Muller. L’Etat en Action. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1987.

- Kamran, M. A., and G. P. Shivakoti. “Comparative Institutional Analysis of Customary Rights and Colonial Law in Spate Irrigation Systems of Pakistani Punjab.” Water International 38, no. 5 (2013): 601–619. doi:10.1080/02508060.2013.828584.

- Kiser, L. L. and E. Ostrom. “The Three Worlds of Action: A Metatheoretical Synthesis of Institutional Approaches.” In Strategies of Political Inquiry, edited by Elinor Ostrom, 179–222. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1982.

- Lasswell, H. D. “The Emerging Conception of the Policy Sciences.” Policy Sciences 1, no. 1 (1970): 3–14. doi:10.1007/BF00145189.

- Mattor, K. M., and A. S. Cheng. “Contextual Factors Influencing Collaboration Levels and Outcomes in National Forest Stewardship Contracting.” Review of Policy Research 32, no. 6 (2015): 723–744. doi:10.1111/ropr.12151.

- McGinnis, M. D. “An Introduction to IAD and the Language of the Ostrom Workshop: A Simple Guide to a Complex Framework”. Policy Studies Journal 39, no. 1 (2011): 169–183. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00401.x.

- Novo, P., and A. Garrido. “From Policy Design to Implementation: An Institutional Analysis of the New Nicaraguan Water Law.” Water Policy 16, no. 6 (2014): 1009–1030. doi:10.2166/wp.2014.188.

- Ostrom, E. “Institutional Rational Choice: An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Paul A. Sabatier, 35–72. 1st ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1999.

- Ostrom, E. "Institutional Rational Choice: An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework." In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Paul A. Sabatier, 21–64. 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2007.

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Ostrom, V. and E. Ostrom. “Public Choice: A Different Approach to the Study of Public Administration.” Public Administration Review 31, no. 3/4 (1971): 203–216. doi:10.2307/974676.

- Sabatier, P. A. Theories of the Policy Process. 1st ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1999.

- Sabatier, P. A. Theories of the Policy Process. 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2007.

- Scharpf, F. Games Real Actors Play. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997.

- Schlager, E., and M. Cox. “The IAD Framework and the SES Framework.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Christopher M. Weible and Paul A. Sabatier, 215–252. 4th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2017.

- Schlager, E., and T. Heikkila. “Resolving Water Conflicts: A Comparative Analysis of Interstate River Compacts.” Policy Studies Journal 37, no. 3 (2009): 367–392. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2009.00319.x.

- Schlüter, A. and I. Theesfeld. “The Grammar of Institutions”. Rationality and Society 22, no. 4 (2010): 445–475. doi:10.1177/1043463110377299.

- Shanahan, E. A., M. D. Jones, M. K. McBeth, and C. M. Radaelli. "The Narrative Policy Framework." In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Christopher M. Weible and Paul A. Sabatier, 173–214. 4th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2017.

- Siddiki, S. “Assessing Policy Design and Interpretation: An Institutions‐Based Analysis in the Context of Aquaculture in Florida and Virginia, United States.” Review of Policy Research 31, no. 4 (2014): 281–303. doi:10.1111/ropr.12075.

- Siddiki, S., and S. Lupton. “Assessing Nonprofit Rule Interpretation and Compliance.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45, no. 4 (2016): 156–174. doi:10.1177/0899764016643608.

- Siddiki, S., C. M. Weible, X. Basurto, and J. Calanni. “Dissecting Policy Designs: An Application of the Institutional Grammar Tool.” Policy Studies Journal 39, no. 1 (2011): 79–103. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00397.x.

- Siddiki, S., X. Basurto, and C. M. Weible. “Using the Institutional Grammar Tool to Understand Regulatory Compliance: The Case of Colorado Aquaculture.” Regulation & Governance 6, no. 2 (2012): 167–188. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5991.2012.01132.x.

- Smajgl, A., L. R. Izquierdo, and M. Huigen. “Modeling Endogenous Rule Changes in an Institutional Context: The Adico Sequence.” Advances in Complex Systems 11, no. 2 (2008): 199–215. doi:10.1142/S021952590800157X.

- Weible, C. M., and D. P. Carter. “The Composition of Policy Change: Comparing Colorado’s 1977 and 2006 Smoking Bans.” Policy Sciences 48, no. 2 (2015): 207–231. doi:10.1007/s11077-015-9217-x.

- Weible, C. M. and P. A. Sabatier, eds. Theories of the Policy Process. 4th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2017.

- Zhang, Y. Governing the Commons in China. London: Routledge, 2017.