Abstract

The declaration of the Anthropocene reflects the magnitude of human-caused planetary violence, but it also risks disguising the inequitable geographies of responsibility and sacrifice that underlie its designation. Similarly, many existing strategies for climate change mitigation, including the development of low-carbon energy, are critical to reducing carbon emissions and yet simultaneously risk deepening extractive violence against marginalized communities. If the uneven distribution of historical and contemporary climate violence is not recognized and redressed, climate change solutions may increase the burdens borne by the very people, places, and environments expected to experience some of the worst effects of climate change itself. To aid in identifying and analyzing the distributive geographies of geo-power capable of facilitating this perverse outcome, this article develops a theoretical framework –climate necropolitics –for revealing the multiscalar processes, practices, discourses, and logics through which Anthropocenic imaginaries can be used to render extractive violence legitimate in the name of climate change response. Drawing on field work using multiple methods, I illustrate the applied value of climate necropolitics through a case study of the Chinese Communist Party's Ecological Civilization. The analysis reveals how the utopian “green” vision of Ecological Civilization, as promoted by both Chinese and Namibian state actors, has been used to legitimate intensified extractive violence against minority communities living near uranium mines in Namibia. I conclude by discussing how geographers can use multiscalar frameworks like climate necropolitics to develop integrated analyses of the uneven distribution of both social and environmental violence in the Anthropocene.

人类世的提出, 反映了人类损害地球的程度, 但也可能掩盖了责任和付出在地理分布上的不平等。类似的, 许多缓解气候变化的战略(包括低碳能源开发)对于降低碳排放很重要, 同时也可能会加剧冶炼对边缘化社区的损害。如果我们没有意识到、不重新考虑历史和当代气候损害的不均衡分布, 那么, 对于那些面临着气候变化最恶劣后果的人群、地点和环境, 环境变化的解决方案可能会增加其负担。针对产生这种结果的地理作用, 为了发现和分析其空间分布, 基于本文研制的一个理论框架(气候死亡政治学)。气候死亡政治学可以用于揭示多尺度的过程、事件、描述和思考, 并以响应气候变化的名义, 通过人类世假想去对冶炼损害进行合法化。本文通过多种方法开展了实地考察, 以中国共产党的生态文明为案例, 描述了气候死亡政治学的应用价值。分析显示, 中国和纳米比亚政府推动的乌托邦式绿色生态文明观念, 如何被用来合法化密集型冶炼对纳米比亚铀矿周边少数族裔社区的损害。最后, 讨论了地理学者如何利用多尺度框架(如气候死亡政治学), 去综合分析人类世里的社会和环境损害的不平等分布。

La declaración del Antropoceno es un reflejo de la magnitud de la violencia planetaria de origen humano, aunque también arriesga disfrazar las geografías inequitativas de responsabilidad y sacrificio que subrayan su designación. Similarmente, muchas de las estrategias existentes de mitigación del cambio climático, incluso el desarrollo de energía baja en carbono, son críticas para reducir las emisiones de carbono pero que simultáneamente arriesgan profundizar la violencia extractiva contra comunidades marginadas. Si la distribución desigual de la violencia climática histórica y contemporánea no es reconocida y rectificada, las soluciones de cambio climático pueden incrementar las cargas soportadas por los propios pueblos, lugares y entornos geográficos de los que se espera experimenten algunos de los peores efectos del propio cambio climático. Para ayudar a identificar y analizar las geografías distributivas del geo-poder, capaz de facilitar tan perverso resultado, este artículo desarrolla un marco teórico ––necropolítica climática–– para revelar los procesos multiescalares, las prácticas, discursos y lógica a través de los cuales los imaginarios antropocénicos pueden usarse para volver legítima la violencia extractiva a nombre de una respuesta al cambio climático. Con base en trabajo de campo en el que se usaron múltiples métodos, ilustro el valor aplicado de la necropolítica climática por medio de un estudio de caso de la Civilización Ecológica del Partido Comunista Chino. El análisis revela cómo la visión utópica “verde” de la Civilización Ecológica, según se promueve por actores estatales chinos y namibios, ha sido usada para legitimar la violencia extractiva intensificada contra comunidades minoritarias que viven cerca de las minas de uranio de Namibia. Concluyo con una discusión sobre cómo pueden los geógrafos usar marcos multiescalares como la necropolítica climática para desarrollar análisis integrados de la desigual distribución de violencia social y ambiental en el Antropoceno.

Epochal declarations like that of the Anthropocene have transformative potential. In acknowledging humans as a climatic, biotic, and geologic force (Crutzen and Stoermer Citation2000), the Anthropocene recognizes the magnitude of human-caused environmental violence—manifesting most notably as climate change—that has become so banal as to be rendered nearly invisible. Understanding and mitigating this violence will require geophysical and environmental research as well as technical and practical innovation across a wide range of fields and professions. Such approaches alone, however, are not sufficient to rewrite the entrenched geographies of violence that have impelled the declaration of this new epoch. Beyond calling attention to the violence enacted by humans upon the Earth, the Anthropocene’s declaration prompts the interrogation of the social relations –including racial capitalism (Robinson Citation[2000] 1983; Gilmore Citation2007), statist geopolitics (Grove Citation2019), and the human-environment binary (Swyngedouw Citation2015) –through which humans enact violence not only against the planet, but also against one another.

History suggests that the realization of lasting transformation from formal declarations of epochal change is far from guaranteed. The formal end of colonialism, for example, signaled both the emergence of a new era and the continuation of violence by other means and new (as well as old) actors. Like the human-driven violence that has caused fundamental changes to the Earth’s ecosystems and atmosphere, human-embodied climate violence is unlikely to be resolved by the mere declaration of the Anthropocene. To the contrary, by lumping all of humanity together as a “singular undifferentiated force” (Yusoff Citation2013, 782), the Anthropocene risks enabling collective amnesia about the uneven historical responsibilities for climate change (Chakrabarty Citation2012) and obscuring its uneven implications. Its planetary declaration can also promote the false assumption that “all men are potentially homines sacri” (Agamben Citation[1995] 1998, 84), ignoring the reality that not all of humanity is likely to be branded as equally sacrificial in the name of righting past and present planetary wrongs.

The Anthropocene’s possibilities and pitfalls as a scalar project have received significant attention from geographers (McKittrick Citation2013; Castree 2014; Braun et al. 2015; Derickson and MacKinnon Citation2015; H. Davis and Todd Citation2017; Pulido Citation2018; J. Davis et al. Citation2019; Yusoff Citation2019; Dalby Citation2020). There has been less attention to how more specific imaginaries associated with the Anthropocene’s declaration might affect existing distributions of violence associated with resource extraction. From the mining of rare earth elements for solar panels and electric vehicles (Klinger Citation2017) to the enclosure of land for biofuel plantations (Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2013), climate change mitigation strategies often rely on existing geographies of extractive violence and marginalization (Sultana Citation2014). Many of those most affected by climate change are also among the most affected by intensified demands for the raw materials of “green” energy. Far from facilitating an end to socioenvironmental violence, “anthropocenic imaginaries”—a term I use here, in an extension of the term’s introduction by Reszitnyk (Citation2015) and development by Mostafanezhad and Norum (Citation2019), to refer not only to visions of environmental apocalypse but also to visions of environmental salvation—could be used to justify such violence as long as it facilitates reduced carbon emissions.

This article introduces climate necropolitics as a theoretical framework for analyzing the implications of Anthropocenic imaginaries for the distribution of climate change–related violence and for identifying the multiscalar processes, practices, discourses, and logics through which such imaginaries can be used to render violence legitimate in the name of climate change response. Climate necropolitics integrates Mbembe’s (Citation2003, Citation2019) concept of necropower, the capacity to “make die and let live,” with geographic scholarship on the spatiality of violence (Pratt Citation2005; Gilmore Citation2007; Yates Citation2011; Tyner Citation2019) and the scalar (geo)politics of the Anthropocene (O’Lear and Dalby Citation2015; Mann and Wainwright Citation2018). Although I have focused this article on climate change mitigation broadly and nuclear energy in particular, I anticipate that climate necropolitics could also be applied to analyze the distributive geographies and legitimation strategies of other forms of climate violence, including those associated with “climate security” (O’Lear and Dalby Citation2015), “green” militarization (Bigger and Neimark Citation2017), adaptation (Thomas and Warner Citation2019), and vulnerability (Ribot Citation2014). I illustrate the applied value of climate necropolitics through a case study of Chinese state-based investments in uranium mining in Namibia. This analysis reveals both the sacrificial geographies that underlie the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) utopian Anthropocenic imaginary of Ecological Civilization and the logics and discourses through which such sacrificial violence is rendered legitimate in the name of climate change mitigation. Before turning to theory and the case study, I begin with a discussion of the broader, intertwined geographies of climate change and extractive violence in Africa.

Climate Change and Extractive Violence in Africa

Nowhere is the possibility that responses to climate change might reinforce rather than redress the violent social relations underlying the declaration of the Anthropocene clearer than in Africa. Although there is no singular “African Anthropocene” (Hecht Citation2018), it is possible to speak to patterns. A historical sacrifice zone par excellence, the continent is a site of simultaneous climate crisis and solution. Africans contributed just 4 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions in 2018, a figure that declines to roughly 1.5 percent after excluding South Africa and the six countries of North Africa (Global Carbon Project Citation2018). Despite the miniscule contributions of the vast majority of Africans to climate change, Africans are expected to experience some of its worst effects. Fears that “climate wars” will engulf the continent often stray into environmental determinism, but the high levels of inequality and poverty, rapid population growth, political characteristics, and reliance on food imports, among other factors, that characterize many African countries are certainly likely to increase the socioecological strains posed by climate change in the coming years (Raleigh, Linke, and O’Loughlin Citation2014; Abrahams and Carr Citation2017).

The climate strains faced by Africans are not limited to vulnerability, adaptation, and conflict. Many of the largest sources of raw materials essential to current climate change mitigation strategies are also located in Africa. The Democratic Republic of the Congo represents roughly 60 percent of global production of cobalt, a key component in electric vehicle batteries (Frankel Citation2016). Globally significant sources of additional battery components, including coltan, graphite, and lithium, are located in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ivory Coast, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, and Zimbabwe. Six countries—Botswana, Gabon, Namibia, Niger, South Africa, and Tanzania—together constitute roughly 20 percent of global uranium resources (World Nuclear Association [WNA] Citation2019a). Even Malawi, a relatively mineral-poor country by African standards, is expected to become a major producer of neodymium and praseodymium, two rare earth elements used in wind turbines and electric vehicles (Scheyder and Shabalala Citation2019). Beyond minerals, carbon sequestration and biofuels plantations exist across the continent, most notably in Ghana, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe (Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2013). Almost all of these projects—sometimes characterized as “green grabbing” (Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2013) or “carbon colonialism” (Lyons and Westoby Citation2014)—capitalize on the relatively low cost of land, mineral, and water rights in African countries to reduce carbon emissions and ensure a continued supply of cheap but “green” energy beyond the continent.

There is both continuity and change in these distributive geographies. Extractive projects that undermine the sustainability of African political economies for the benefit of outside actors continue a long history of wealthier people and places outsourcing the negative externalities of accumulation and consumption to poorer people and places. Yet whereas “dirty” extractive endeavors have been rendered legitimate in the name of colonialism, nationalism, racial capitalism, or energy security, among other justifications, “green” extractive projects are often justified in the name of universal climate salvation, including for the very populations most likely to bear their costs. Indeed, instead of the clichéd “starving African child” used as motivation for Western children to finish their dinners, there is now the “climate change–besieged African child” used as motivation to buy a new electric car—a car with a battery, as documented by O’Driscoll (Citation2017), containing ten to twenty pounds of cobalt perhaps mined by several such African children. Making sense of this perverse outcome, in which many of the greatest climate sacrifices are borne by the very populations on whose behalf they are claimed to be made, requires attending to the uneven geographies of violence that are too easily hidden beneath Anthropocenic imaginaries and the multiscalar logics and processes through which such violence is rendered legitimate.

Necropolitics for the Anthropocene: Death-Worlds in the Name of Planetary Life

Identifying and explaining how and why violence against whom is rendered legitimate by whom is a topic of significant interest in political theory (Fanon Citation1963; Arendt Citation1968; Agamben Citation[1995] 1998) as well as in geography (Pratt Citation2005; Gilmore Citation2007; Yates Citation2011; McKittrick Citation2013; Tyner Citation2019). Among geographers, Mbembe’s (Citation2003, Citation2019) necropolitics has emerged as a particularly useful approach to studying the spatiality and justification of violence (Wright Citation2011; Cavanagh and Himmelfarb Citation2015; Davies Citation2018; Alexis-Martin Citation2019; Margulies Citation2019). Necropolitics draws its name from the concept of necropower, defined by Mbembe (Citation2003) as “the power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die” (11). Like biopower (“the power to ‘make’ live and ‘let’ die”; Foucault Citation[1976] 2003), the target of necropower is the population rather than the individual. Necropower is distinguished from biopower, however, by the relationship between the targeted population and the sovereign. Whereas sovereigns justify biopower in the name of protecting life for the population on which biopower is imposed, necropower is enacted against “them” in the name of protecting life for “us.” Biopower, in other words, is a tool to govern the sovereign’s “subjects.” Necropower, by contrast, is a tool to control and render disposable “savage” (Mbembe Citation2019, 92) populations that might otherwise endanger (or be perceived to endanger) the sovereign’s subjects or authority.

The suitability of necropolitics for analyzing the distribution and legitimation of violence is enhanced by Mbembe’s attention to where necropolitical violence is enacted as well as against whom. His work here builds on that of Fanon (Citation1963), who in Wretched of the Earth described the colonizer’s perspective on colonized neighborhoods as follows: “[t]hey are born there, it matters little where or how; they die there, it matters not where, nor how” (38, italics added). Similarly, for Mbembe (Citation2003), colonized territories are “the zone where the violence of the state of exception is deemed to operate in the service of ‘civilization’” (24). Contemporary iterations of these spaces—“death-worlds” in Mbembe’s (Citation2019, 92) terminology—are a spatial strategy through which sovereigns render violence legitimate without outright colonization, because such necropower is exercised not against subjects “here”, but rather against “savage” populations (the “living dead”) “there”. In addition to immobilization (“the camp”), sovereigns can exercise necropower through the spatial strategy of “scattering” (Mbembe Citation2019, 86), as exemplified by the violence endured by refugees and displaced persons (Davies, Isakjee, and Dhesi Citation2017). In contrast to classical sovereign violence, which entails immediate death for the individual, the disposability experienced by those relegated to the status of the living dead rarely entails a quick demise. Rather than immediate death for individuals at the hands of the sovereign, death-worlds subject entire populations to extended conditions of death-in-life.

Climate violence might be diffuse, but it is not randomly distributed. Whether through adaptation (K. J. Grove Citation2010; Thomas and Warner Citation2019), conflict (Raleigh, Linke, and O’Loughlin Citation2014), or mitigation (Curley Citation2018; Mulvaney Citation2019; Riofrancos Citation2019), climate change often manifests as violence against populations that have already been violently marginalized (Sultana Citation2014). Geographers have illustrated the value of necropolitics for analyzing the uneven geographies of violence associated with colonial dispossession by conservation (Cavanagh and Himmelfarb Citation2015), chemical exposure (Davies Citation2018), nuclear imperialism (Alexis-Martin Citation2019), and human–wildlife relations (Margulies Citation2019), among other environmental topics. In these cases, state actors exercised or allowed the exercise of necropower within the state’s territorial boundaries in the name of protecting the state’s chosen subject population. The planetary declaration of the Anthropocene, however, challenges conceptualizations of environmental sovereignty limited to territorial states (O’Lear and Dalby Citation2015). How might this scalar shift affect the legitimation of necropolitical violence and the geographies of its distribution?

Mann and Wainwright (Citation2018) propose that climate change could provoke the emergence of planetary sovereignty: a state of exception “proclaimed in the name of preserving life on Earth” (15). The promise of planetary salvation is a powerful justification, one that a sovereign could seemingly use to legitimate an extensive range of action, including violence. Indeed, although Mann and Wainwright (Citation2018) do not engage explicitly with Mbembe’s necropolitics, they anticipate that planetary sovereignty would entail the determination of “what measures are necessary and what and who must be sacrificed in the interests of life on Earth” (15). By explaining how climate change could be used to justify the rescaling of sovereignty, Mann and Wainwright have identified a pathway through which climate change could be used to legitimate the borderless exercise of climate necropower, rendering some populations sacrificial so that others—and the planet—might live. My argument builds on this pathway by developing a framework, climate necropolitics, for identifying and analyzing the processes, practices, discourses, and logics through which Anthropocenic imaginaries can be used to render extractive violence legitimate within and beyond the borders of the territorialized state in the name of planetary salvation. In the next section, I apply climate necropolitics to the case study of Ecological Civilization to reveal how Chinese and Namibian officials have leveraged this imaginary to justify intensified necropolitical violence and, in so doing, have magnified the unevenly distributed violence of climate change itself.

Placing Climate Necropolitics: The Extractive Violence of Ecological Civilization in Namibia

Methods

The case study that follows draws on over two cumulative years of research on uranium mining in Namibia between 2011 and 2019, with a focus on Chinese state investments. Although I conducted research across the country, most of the empirical data presented here were collected in Namibia’s uranium mining region of Erongo or in Windhoek, Namibia’s capital city. I used a multimethod approach consisting of participant observation, interviews, focus groups, and textual analysis.1 My participant observation entailed data collection at more than sixty events, including government and community meetings, public forums, industry conferences, and protests. I also made four visits to uranium mines, which allowed me to observe mining operations, albeit under the close supervision of mine representatives. My interviews involved 102 Namibians, including residents of mining-proximate communities, government officials (local, regional, and national), mine employees, and mining industry representatives. These interviews were semistructured with the exception of interviews with government officials, who often required a list of questions in advance. I also conducted seventeen focus groups, which included similar participants to the interviews. To enhance participant comfort in the cultural context of Namibia, I organized each focus group on the basis of previous alignment, such as members of a community organization or miners employed at the same pay grade. Finally, I analyzed more than 800 documents related to mining policies and licenses, environmental regulations and conditions, and minority communities in Namibia. These documents included reports by government, mining industry stakeholders, and civil society groups; speeches by political leaders; and media coverage of mining, the environment, China, and the specific communities where I conducted research.

Ecological Civilization and Chinese State Investments in Uranium Mining

Despite its domestic deployment of necropower against minority populations (Alexis-Martin Citation2019), the CCP’s historical defense of state-defined sovereignty makes it seemingly an unlikely candidate for extraterritorial climate necropolitics. As I have argued elsewhere though (DeBoom Citation2020a), the CCP has become more assertive in exercising extraterritorial sovereignty in recent years, including in the environmental realm. This shift is reflected in the rising prominence of Ecological Civilization (Yeh Citation2009; Hansen, Li, and Svarverud Citation2018; Pow Citation2018), a CCP-promoted Anthropocenic imaginary that envisions a global transition, led by China, from “Western industrial civilization” to “socialist ecological civilization” (Geall and Ely Citation2018). Like the Anthropocene, Ecological Civilization recognizes that the well-being of humanity depends on the well-being of the planet. President Xi (Citation2017) characterized it as a “global endeavor” that “will benefit generations to come” through the implementation of a “new model of modernization with humans developing in harmony with nature” (47). The aim of Ecological Civilization, in other words, is to rectify the environmental wrongs recognized by the declaration of the Anthropocene.

Fittingly, the same energy source that fueled the 1945 Trinity test in New Mexico—one proposed starting date for the Anthropocene—is also a foundational fuel for Ecological Civilization: nuclear energy. Despite connecting its first nuclear reactor to the grid only in 1991—a year in which the United States had 112 operating reactors—China is the world’s fastest growing generator of nuclear energy (International Energy Agency Citation2018). It is expected to surpass the United States as the largest nuclear energy producer by 2040 (International Energy Agency Citation2018). The CCP’s current nuclear energy plans suggest that its annual uranium consumption by 2050 might rival the world’s total uranium consumption in 2015. This is not an immediate impediment: China has the world’s eighth-largest uranium reserves (Zhang Citation2015). Yet instead of primarily pursuing intensified domestic extraction, the CCP is sourcing most of its uranium from abroad. China’s uranium imports have grown faster than those of any other country over the past decade (WNA Citation2020). Rather than relying solely on international market purchases to source this uranium, China’s two nuclear state-owned enterprises (SOEs)—China General Nuclear Power Corporation (CGN) and China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC)—have purchased ownership stakes in foreign uranium mines since 2006, the first year in which the country’s domestic demand outpaced supply (WNA Citation2020). The overseas uranium holdings of Chinese SOEs accounted for roughly 80 percent of global foreign investments in uranium between 2005 and 2015 and are estimated to be three times the size of China’s domestic proven reserves (WNA Citation2020).

As shown in , most of the foreign uranium production controlled by Chinese SOEs is located in Namibia. These investments have catalyzed significant changes in Namibia’s uranium mining sector over the past fifteen years (DeBoom Citation2020b). Between 1976 and 2006, Namibia had only one operational uranium mine: Rössing, then owned by Rio Tinto. In 2006, the global uranium rush catalyzed the development of Namibia’s first new uranium mine in thirty years (Conde and Kallis Citation2012). By early 2012, however, the Fukushima nuclear disaster had precipitated a crash in global uranium prices that has persisted into early 2020. All of Namibia’s active and under-development uranium mines have subsequently either been mothballed or sold (in part or in whole) to Chinese SOEs, which have leveraged low global prices to enhance China’s uranium supply security. In 2012, CGN purchased a 90 percent stake in Husab, the world’s second largest operating uranium mine. CGN’s intra-state competitor CNNC followed suit in 2014, when it purchased a 25 percent stake in Langer Heinrich. Most recently, in 2019, CNNC purchased a 90 percent ownership stake in Rössing, the world’s longest running open pit uranium mine. This last purchase prompted significant controversy in Namibia, because it means that Chinese SOEs now have at least a 25 percent ownership in each of Namibia’s active uranium mines. Together, these three mines account for 12 percent of global uranium production and more than 90 percent of production from foreign mines in which Chinese SOEs have ownership stakes (WNA Citation2020).

Table 1. Chinese SOE ownership in uranium mines located overseas

Radioactive and Socioenvironmental Violence in Namibia

For most residents of the rural, agricultural communities located near Chinese SOE-owned uranium mines in Namibia’s Namib desert, the lived experience of Ecological Civilization is a far cry from the CCP’s green utopian vision. Namibia is the world’s second-least densely populated country, and few places in Namibia are more sparsely populated than rural Erongo. Despite having two of Namibia’s four largest cities, Erongo’s population density is 6.1 people per square mile (Erongo Regional Council Citation2011). With the exception of the occasional tourist bound for an exclusive campsite or ecoreserve, the villages of rural Erongo lie distant from major roadways and attract few visitors. My interviews with Namibians living elsewhere, including in urban Erongo, suggested that many Namibians are unaware that these communities even exist. Their invisibility reflects not only their physical isolation but also their demographic composition and socioeconomic status.2 Most residents of rural, agricultural communities rely on subsistence livelihoods, including subsistence farming, goat herding, and artisanal mining, all of which are relatively low-status livelihoods in the local and national contexts. Most residents also identify as members of the Nama and Damara minority groups, which respectively comprise roughly 5 and 7 percent of Namibia’s population.3

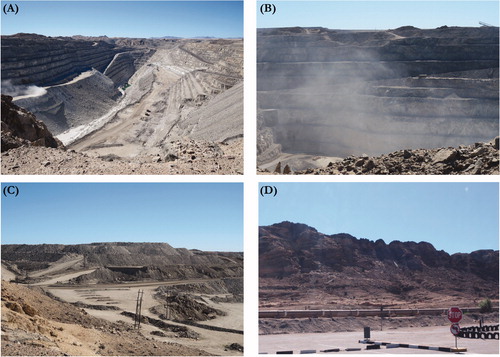

It is fitting that one of the earliest uses of the term sacrifice zone was to describe the radioactive landscapes created through nuclear weapons testing (Kirsch Citation2005; Pitkanen and Farish Citation2018). From the South African state’s pursuit of nuclear weapons to the CCP’s nuclear energy strategy, rural communities near uranium mines in Namibia have been rendered sacrificial in the name of outside actors’ geopolitical and political ambitions. Unlike most mine employees, who live in the provided housing of company towns or distant from the mines in Erongo’s coastal cities, residents of rural, minority communities largely live in unsealed homes. Their outdoor livelihoods involve daily, direct interactions with soil, exposing them to the pervasive dusty winds of the Namib desert. The open-pit design of each of Namibia’s uranium mines () aggravates this situation. Given the dry, windswept character of the desert environment and the heavy equipment used in mining—and despite significant water usage, as detailed later—dust control at these mines is nearly impossible (). In addition to transporting dust from the open pit to downwind communities, the Namib’s intense winds can dislodge radioactive particles from the expansive deposits of mine tailings (unused material remaining after uranium extraction) stored around the edges of Namibia’s mines (). These tailings, which retain most of the radioactivity of uranium itself (National Research Council Citation2011) are particularly profuse in Namibia due to the low grades of its granite-housed uranium deposits; many more tons of host ore body must be detonated and removed to extract the same volume of uranium when compared with higher grade mines such as those in Canada, Kazakhstan, and even China (DeBoom Citation2020b).

Figure 1 The Rössing uranium mine in Namibia. (A) A view of the open pit from the mine’s southern edge. (B) Dust from the movements of mining equipment. There was no active blasting, which would have created far more extensive dust, at the time of this photograph. (C) Mine tailings deposits large enough to be traversed by several roads. (D) A pipeline transporting water to the mine. Photos by author.

Yet due to the logics of what Hecht (Citation2009) has termed “nuclearity,” or the “apparently immutable ontology [that] has long distinguished nuclear things from non-nuclear things” (897), many government authorities and industry leaders treat the radioactive risks faced by residents of uranium mining–proximate communities as if wholly separate from the risks associated with nuclear energy. This distinction is reflected in the scientific and regulatory radiation exposure threshold of 100 millisieverts (mSv) per year, which distinguishes “man-made” nuclear weapons and energy-based exposures from “natural” uranium-based exposures (Hecht Citation2012). Despite this distinction, the likelihood of negative health outcomes, including cancer, rises in association with increasing cumulative radiation exposure (National Research Council Citation2011). These health outcomes can take decades—or, in the case of hereditary disorders, generations—to emerge (Kreuzer et al. Citation2008). The “slow violence” (Nixon Citation2013, 2) of long-term, low-level radiation exposure is rendered even more invisible by the compounding risk factors faced by residents of local minority communities, including their inherent exposure to environmental dust, inadequate access to preventative care, and low socioeconomic status. These characteristics make it difficult to definitively attribute negative health outcomes to uranium mining (DeBoom Citation2020b).

The violence of uranium mining extends beyond radioactivity to the intertwined environmental and sociocultural violence of water scarcity. Because the Namib receives only five to ten inches of annual rainfall, rural communities rely on aquifers and ephemeral rivers—filtered through the potentially contaminated sand of the Namib desert—for their water supply. The combination of intensified uranium mining and climate change–attributed drought, which has affected southwestern Africa since 2013, has depleted those water sources. One herder reflected on his community’s future with frustration during a focus group in late 2015. The mines build desalination plants and pipelines () when they need water, he explained, but his community cannot afford to buy water, let alone pipe water in. “Water belongs to our culture,” he explained. “What happens to us when the water here is no more?” The man’s village signed an emergency contract with NamWater, the Namibian government’s water utility, for a water “loan” roughly one year later. The community has not yet been able to repay this loan and, as of my last contact with the community, there was little hope that it would be able to do so. Other communities owe NamWater upwards of $6,500, a nearly insurmountable debt in the local context. NamWater has threatened to close the taps of “debtor” villages it deems unable to pay, escalating intragroup tensions in communities already under tremendous strain.

The conditions faced by these rural Erongo communities exemplify what Mbembe (Citation2003) characterized as “death-in-life”; it is being “kept alive but in a state of injury” (21). Residents face an agonizing choice. They can continue to reside in the death-world, or they can “scatter,” abandoning their livelihoods, communities, and identities in the process. A young man who had relocated to look for work in a nearby city told me that, as a farmer, he “could not see a future there [in his home community]. … We wonder where the water disappears? Husab [uranium mine] takes from the Swakop River. It never reaches my community.” His anger was echoed in interviews and focus groups with minority Namibians across the region. Although most of the relocated individuals I interviewed maintained at least sporadic contact with their home communities in the Namib, many indicated that they felt a fundamental part of their identity had been lost.

Legitimating Violence: Climate Necropower

Although surely a sign of geopolitical change, the embodied violence of uranium mining for minority communities in Namibia casts doubt on whether Ecological Civilization departs from the extractive violence that has facilitated the Anthropocene. Chinese leaders have carefully contrasted their Anthropocenic imaginary with colonization by linking Ecological Civilization to the CCP’s geopolitical emphasis on “south-south solidarity.” “China is a socialist country,” then-Vice Minister of Environmental Protection Pan Yue argued in 2006, “and cannot engage in environmental colonialism, nor act as a hegemony, so it must move towards a new type of civilization” (Zhou Citation2006). Yet the CCP’s promotion of Ecological Civilization as China’s “global duty and mission” (Pan Yue, quoted in Zhou Citation2006) is reminiscent of the “civilizing” missions used to justify the necropolitical violence of colonization. Like those colonial projects, Ecological Civilization is far from self-sacrificing. Its carbon benefits might be globally significant, but its most concentrated benefit is likely to be the enhancement of the CCP’s geopolitical reputation. Its costs, meanwhile, appear likely to borne disproportionately by marginalized communities for whom the violence of uranium mining in the name of climate change mitigation is rivaled only by the violence of climate change itself.

The necropolitical benefits of intensified uranium mining in Namibia are not limited to China. Indeed, it was life rather than death, or even exploitation, that featured most prominently in my interviews with Namibian officials as well as in my analysis of political leaders’ speeches and government press releases. Mining is the largest contributor to the Namibian government’s annual revenue, and Chinese investments have increased that contribution. One mine alone—Husab—is expected to generate between $170 million and $200 million in annual government revenues at full production, an amount roughly equivalent to 5 percent of the Namibian government’s annual revenues prior to its opening. Beyond revenues, Namibian officials argue that intensified uranium mining will benefit minority communities. One official described mining as a “lifeline” for a region he characterized as “jobless.” Bemoaning the fact that I had spent time in such “hamlets,” he asked “Is that [what you saw] a life?” He shook his head, answering his own question before I could. Namibian President Hage Geingob expressed similar sentiments in a 2015 speech, when he described the Husab mine as follows: “The mine was opened in a desolate area characterized by barren hills and mountains amongst which a modern highway has been built, leading to life” (italics added). Chinese diplomats and mine executives expressed similar sentiments. At an event commemorating the Husab uranium mine’s first yellowcake in 2016, for example, a Chinese SOE representative stated, “We can now proudly declare that the Husab mine is in production, bringing new vigor and vitality to the ancient Namib desert.”

The violence associated with uranium extraction in Namibia presdates Chinese investments. The profitability of Namibia’s first uranium mine—Rössing, then owned by Rio Tinto—was facilitated by South Africa’s imposition of apartheid in Namibia prior to its 1990 independence (Hecht Citation2012). Today, however, this violence is rendered legitimate not in the explicit name of racial capitalism, as espoused by the apartheid South African state, but rather in the name of Ecological Civilization and its promise of planetary salvation. Several Namibian officials even adopted the language of Ecological Civilization in my interviews, expressing hope that high-profile Chinese investments will attract other “eco-minded” investors to Namibia’s “green” uranium mines. Government officials have subsequently taken this rhetoric on the road, using the slogan of “green” uranium to solicit interest among other would-be nuclear investors at events like the Abu Dhabi Sustainability Week.

The statements just described suggest that the minority communities of rural Erongo are not the subjects of Ecological Civilization but rather its “savages,” the “living dead” (Mbembe Citation2019, 92) against whom the exercise of necropower can be rendered legitimate “in the service of ‘civilization’” (Mbembe Citation2003, 24). For representatives of the Chinese and Namibian states, intensified uranium mining is not life-taking; it is life-giving. Namibian officials in particular often described minority communities to me as if they were “part of nature … ‘natural’ human beings who lacked the specifically human character” (Arendt Citation1968, 192). Reflecting the definition of “slow violence” developed by Nixon (Citation2013), the radioactive violence embodied by these communities “occurs gradually and out of sight … dispersed across time and space” (2) from the lofty Anthropocenic imaginary of Ecological Civilization. Local Namibians’ understandings of Ecological Civilization reflect not the transcendence of extractive violence but rather its entrenchment through “green” energy manifesting as violence against those already bearing the violence of climate change itself.

Conclusion

Will the declaration of the Anthropocene catalyze a radical revision of the violent geographies that have facilitated climate change? Or will it usher in a “status quo utopia”—a “green” future that is merely a “thinly disguised version of the present” (Günel Citation2019, 13)? Epochal moments can sow transformative possibilities, but reaping their potential requires more than declarations. The violence of colonialism did not “magically disappear after the ceremony of trooping the national colors” (Fanon Citation1963, 60). Likewise, the necropolitical violence that preceded the Anthropocene’s declaration has not magically disappeared upon its introduction. Like the iterations of necropower that have come before, the violence of climate necropower is accumulative. Existing strategies of social debridement—of protecting “us” from “them” while extracting climate solutions from “them” as has been done historically—might reduce carbon emissions, but they are also likely to reinforce rather than rectify existing geographies of violence. Left to fester too long, such sacrificial necrosis risks inciting an endless cycle of inversion—a planet of ever-expanding, diffuse death-worlds created in the name of planetary life.

The distributive geographies of climate change and its associated Anthropocenic imaginaries—including which strategies for mitigation are pursued, where, and based on which priorities decided by whom—are likely to set the foundational conditions for the transformative potential or lack thereof of the Anthropocene’s declaration. Understanding these geographies necessitates a multiscalar approach that does not lose sight of the uneven distribution of Anthropocenic violence in the pursuit of existential, technical, and geophysical understanding of the Anthropocene itself. Geographers can contribute to this task by disaggregating the Anthropocene and asking “what is being secured and for whom” through climate change response strategies and, of course, where (O’Lear and Dalby Citation2015, 207). Trained in approaches that transcend both scale and traditional disciplinary boundaries between the social and the physical or the environmental and the cultural, geographers are well-suited to holding “the planet and a place on the planet on the same analytic plane” (Hecht Citation2018, 112, italics in original). Such strategies can reconcile the Anthropocene as both a much-needed recognition of human-induced violence on a planetary scale and a scalar project that risks obscuring not only “who pays the price for humanity’s planetary footprints” (Hecht Citation2018, 135) but also who pays the price for mitigating those footprints.

Toward that end, this article introduced climate necropolitics as a theoretical framework for analyzing the multiscalar processes, practices, discourses, and logics through which Anthropocenic imaginaries like Ecological Civilization can be used to render intensified extractive violence legitimate in the name of climate change response. I illustrated the applied value of this approach through a case study of investments by Chinese SOEs in uranium mining in Namibia. Applying climate necropolitics to this case study revealed the logics through which socioenvironmental violence, as embodied by minority communities in Namibia, is reinforced and rendered legitimate by both Chinese and Namibian state actors through the Anthropocenic imaginary of Ecological Civilization. Although my analysis focused on climate change mitigation—namely, nuclear energy—I anticipate that climate necropolitics could also be applied to analyze the distributive geographies and legitimation strategies associated with other forms of climate violence, including in the realms of climate security (O’Lear and Dalby Citation2015) and “green” militarization (Bigger and Neimark Citation2017) as well as adaptation (Thomas and Warner Citation2019) and vulnerability (Ribot Citation2014).

The argument presented here should not be interpreted as a call to abandon either the Anthropocene or pursuits of climate change mitigation. Indeed, my argument is to the contrary. The framework of climate necropolitics is a call not to abandon mitigation but rather to expand our definition of mitigation to include the mitigation of violent social relations. It is a call not to abandon the Anthropocene but rather to investigate and seek to rectify its violent manifestations at scales beyond the planetary. As a framework for understanding how and why current strategies for climate change mitigation risk legitimating sacrificial violence against marginalized communities in the name of preserving planetary life, climate necropolitics echoes Ruddick’s (Citation2015) call for an Anthropocene that “renders neither people nor the planet as disposable” (1126). I hope it will prompt my fellow geographers—whether self-identified as physical or human, cultural or environmental, or, like most, some combination thereof—to attend not only to the practical questions of what must be done to ensure planetary life but also to the ethical questions of what should be done and by whom.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the individuals and communities in Namibia who shared their experiences of and insights about uranium mining, climate change, violence, and the state with me. I also extend my thanks to Natalie Koch, the members of the Critical Ecologies Lab at the University of South Carolina, and the participants of panels at the 2019 and 2020 American Association of Geographers annual meetings as well as the 2020 Dimensions of Political Ecology conference for their suggestions on previous iterations of this article. Finally, thank you to two anonymous referees for their constructive suggestions and to David Butler for his thoughtful editorial insights. Any errors or omissions are mine alone.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Meredith J. DeBoom

MEREDITH J. DeBOOM is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29201. E-mail: [email protected]. She is a political geographer whose research focuses on debates over development, distribution, extraction, and (geo)politics in southern Africa. Her current work examines how Africans are engaging with geopolitical and environmental changes to pursue their own political goals.

Notes

1 Details on the demographic and geographic composition of focus group and interview participants are available in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 of DeBoom (Citation2018), which is publicly available via the University of Colorado’s open access research repository (CU Scholar).

2 This section focuses on nonmining communities in rural Erongo. It is important to distinguish these communities from mining company towns like Arandis, because the two types of communities have distinct cultural, socioeconomic, and demographic characteristics. For an analysis of the risks faced by mine employees and residents of company towns in Erongo, see DeBoom (Citation2020b).

3 Namibia’s current president, Hage Geingob, belongs to the Damara group. He is, however, an exception in the upper echelon of Namibian national politics, which are dominated by the SWAPO political party and its base of support in the Owambo majority group.

References

- Abrahams, D., and E. R. Carr. 2017. Understanding the connections between climate change and conflict: Contributions from geography and political ecology. Current Climate Change Reports 3 (4):233–42.

- Agamben, G. [1995] 1998. Homo sacer: Sovereign power and bare life. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Alexis-Martin, B. 2019. The nuclear imperialism-necropolitics nexus: Contextualizing Chinese–Uyghur oppression in our nuclear age. Eurasian Geography and Economics 60 (2):152–76.

- Arendt, H. 1968. The origins of totalitarianism. Orlando, FL: Harcourt.

- Bigger, P., and B. D. Neimark. 2017. Weaponizing nature: The geopolitical ecology of the U.S. Navy’s biofuel program. Political Geography 60:13–22.

- Braun, B., M. Coleman, M. Thomas, and K. Yusoff. 2015. Grounding the Anthropocene: Sites, subjects, struggles in the Bakken oil fields. Antipode Foundation, November 3. Accessed December 1, 2019. https://antipodefoundation.org/2015/11/03/grounding-the-anthropocene.

- Castree, N. 2014. The Anthropocene and geography I: The back story. Geography Compass 8 (7):436–449.

- Cavanagh, C. J., and D. Himmelfarb. 2015. “Much in blood and money”: Necropolitical ecology on the margins of the Uganda protectorate. Antipode 47 (1):55–73. doi: 10.1111/anti.12093.

- Chakrabarty, D. 2012. Postcolonial studies and the challenge of climate change. New Literary History 43 (1):1–18.

- Conde, M., and G. Kallis. 2012. The global uranium rush and its Africa frontier: Effects, reactions and social movements in Namibia. Global Environmental Change 22 (3):596–610.

- Crutzen, P., and F. Stoermer. 2000. Have we entered the Anthropocene? International Geosphere-Biosphere Program Newsletter 41:17–18.

- Curley, A. 2018. A failed green future: Navajo green jobs and energy “transition” in the Navajo Nation. Geoforum 88:57–65.

- Dalby, S. 2020. Anthropocene geopolitics: Globalization, security, sustainability. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

- Davies, T. 2018. Toxic space and time: Slow violence, necropolitics, and petrochemical pollution. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (6):1537–53.

- Davies, T., A. Isakjee, and S. Dhesi. 2017. Violent inaction: The necropolitical experience of refugees in Europe. Antipode 49 (5):1263–84.

- Davis, H., and Z. Todd. 2017. On the importance of a date, or decolonizing the Anthropocene. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 16 (4):761–80.

- Davis, J., A. A. Moulton, L. Van Sant, and B. Williams. 2019. Anthropocene, Capitalocene, … Plantationocene?: A manifesto for ecological justice in an age of global crises. Geography Compass 13 (5):e12438. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12438.

- DeBoom, M. J. 2018. Developmental fusion: Chinese investment, resource nationalism, and the distributive politics of uranium mining in Namibia. PhD diss., University of Colorado-Boulder. https://scholar.colorado.edu/concern/graduate_thesis_or_dissertations/hd76s013x.

- DeBoom, M. J. 2020a. Sovereignty and climate necropolitics: The tragedy of the state system goes “green.” In Handbook on the changing geographies of the state: New spaces of geopolitics, ed. S. Moisio, A. Jonas, N. Koch, C. Lizotte, and J. Luukkonen, 276–286. Northampton, UK: Edward Elgar.

- DeBoom, M. J. 2020b. Toward a more sustainable energy transition: Lessons from Chinese investments in Namibian uranium. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 62 (1):4–14.

- Derickson, K. D., and D. MacKinnon. 2015. Toward an interim politics of resourcefulness for the Anthropocene. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 105 (2):304–12.

- Erongo Regional Council. 2011. Demographics. Accessed July 12, 2020. http://www.erc.com.na/erongo-region/demographics/.

- Fairhead, J., M. Leach, and I. Scoones, eds. 2013. Green grabbing: A new appropriation of nature? London and New York: Routledge.

- Fanon, F. 1963. The wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove.

- Frankel, T. D. 2016. The cobalt pipeline. Washington Post, September 30. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/business/batteries/congo-cobalt-mining-for-lithium-ion-battery/.

- Foucault, M. [1976] 2003. Society must be defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–1976. London: Allen Lane.

- Geall, S., and A. Ely. 2018. Narratives and pathways towards an Ecological Civilization in contemporary China. The China Quarterly 236:1175–96.

- Gilmore, R. W. 2007. Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus and crisis in globalizing California. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Global Carbon Project. 2018. Supplemental data of global carbon budget 2018. https://www.icos-cp.eu/global-carbon-budget-2018.

- Grove, J. V. 2019. Savage ecology: War and geopolitics at the end of the world. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Grove, K. J. 2010. Insuring “our common future”? Dangerous climate change and the biopolitics of environmental security. Geopolitics 15 (3):536–63.

- Günel, G. 2019. Spaceship in the desert: Energy, climate change, and urban design in Abu Dhabi. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hansen, M. E., H. Li, and R. Svarverud. 2018. “Ecological Civilization”: Interpreting the Chinese past, projecting the global future. Global Environmental Change 53:195–203.

- Hecht, G. 2009. Africa and the nuclear world: Labor, occupational health, and the transnational production of uranium. Comparative Studies in Society and History 51 (4):896–926.

- Hecht, G. 2012. Being nuclear: Africans and the global uranium trade. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hecht, G. 2018. Interscalar vehicles for an African Anthropocene. Cultural Anthropology 33 (1):109–41.

- International Energy Agency. 2018. World energy outlook 2018. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2018.

- Kirsch, S. 2005. Proving grounds: Project Plowshare and the unrealized dream of nuclear earthmoving. Newark, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Klinger, J. M. 2017. Rare earth frontiers: From terrestrial subsoils to lunar landscapes. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Kreuzer, M., L. Walsh, M. Schnelzer, A. Tschense, and B. Grosche. 2008. Radon and risk of extrapulmonary cancers: Results of the German uranium miners’ cohort study, 1960–2003. British Journal of Cancer 99 (11):1946–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604776.

- Lyons, K., and P. Westoby. 2014. Carbon colonialism and the new land grab: Plantation forestry in Uganda and its livelihood impacts. Journal of Rural Studies 36:13–21.

- Mann, G., and J. Wainwright. 2018. Climate Leviathan: A political theory of our planetary future. London: Verso.

- Margulies, J. D. 2019. Making the “man-eater”: Tiger conservation as necropolitics. Political Geography 69:150–61.

- Mbembe, A. 2003. Necropolitics. Public Culture 15 (1):11–40.

- Mbembe, A. 2019. Necropolitics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- McKittrick, K. 2013. Plantation futures. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17 (3):1–15.

- Mostafanezhad, M., and R. Norum. 2019. The Anthropocenic imaginary: Political ecologies of tourism in a geological epoch. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 27 (4):421–35.

- Mulvaney, D. 2019. Solar power: Innovation, sustainability, and environmental justice. Oakland: University of California Press.

- National Research Council. 2011. Scientific, technical, environmental, human health and safety, and regulatory aspects of uranium mining. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

- Nixon, R. 2013. Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- O’Driscoll, D. 2017. Overview of child labour in the artisanal and small-scale mining sector. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a5f34feed915d7dfb57d02f/209-213-Child-labour-in-mining.pdf.

- O’Lear, S., and S. Dalby, eds. 2015. Reframing climate change: Constructing ecological geopolitics. London and New York: Routledge.

- Pitkanen, L., and M. Farish. 2018. Nuclear landscapes. Progress in Human Geography 42 (6):862–80. doi: 10.1177/0309132517725808.

- Pow, C. P. 2018. Building a harmonious society through greening: Ecological Civilization and aesthetic governmentality in China. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (3):864–83.

- Pratt, G. 2005. Abandoned women and spaces of the exception. Antipode 37 (5):1052–78.

- Pulido, L. 2018. Racism and the Anthropocene. In Future remains: A cabinet of curiosities for the Anthropocene, ed. G. Mitman, M. Armiero, and R. S. Emmett, 116–28. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Raleigh, C., A. Linke, and J. O’Loughlin. 2014. Extreme temperatures and violence. Nature Climate Change 4 (2):76–77.

- Reszitnyk, A. 2015. Uncovering the Anthropocenic imaginary: The metabolization of disaster in contemporary American culture. PhD dissertation, McMaster University.

- Ribot, J. 2014. Cause and response: Vulnerability and climate in the Anthropocene. The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (5):667–705.

- Riofrancos, T. 2019. What green costs. Logic, December 9. https://logicmag.io/nature/what-green-costs/.

- Robinson, C. 1983 [2000]. Black Marxism: The making of the black radical tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Ruddick, S. 2015. Situating the Anthropocene: Planetary urbanization and the anthropological machine. Urban Geography 36 (8):1113–30.

- Scheyder, E., and Z. Shabalala. 2019. Pentagon eyes rare earth supplies in Africa. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-rareearths-pentagon-exclusive/exclusive-pentagon-eyes-rare-earth-supplies-in-africa-in-push-away-from-china-idUSKCN1T62S4.

- Sultana, F. 2014. Gendering climate change: Geographical insights. The Professional Geographer 66 (3):372–81.

- Swyngedouw, E. 2015. Depoliticized environments and the Anthropocene. In The international handbook of political ecology, ed. R. L. Bryant, 131–46. Northampton, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Thomas, K. A., and B. P. Warner. 2019. Weaponizing vulnerability to climate change. Global Environmental Change 57:101928.

- Tyner, J. A. 2019. Dead labor: Toward a political economy of premature death. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- World Nuclear Association. 2019a. Supply of uranium. Accessed February 20, 2020. https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/uranium-resources/supply-of-uranium.aspx.

- World Nuclear Association. 2019b. Uranium mining. Accessed February 20, 2020. https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/uranium-resources/supply-of-uranium.aspx.

- World Nuclear Association. 2020. China’s nuclear fuel cycle. Accessed February 26, 2020. https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-a-f/china-nuclear-fuel-cycle.aspx.

- Wright, M. W. 2011. Necropolitics, narcopolitics, and femicide: Gendered violence on the Mexico–U.S. border. Signs 36 (3):707–31. doi: 10.1086/657496.

- Xi, J. 2017. Secure a decisive victory in building a moderately prosperous society. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/download/Xi_Jinping's_report_at_19th_CPC_National_Congress.pdf.

- Yates, M. 2011. The human-as-waste, the labor theory of value and disposability in contemporary capitalism. Antipode 43 (5):1679–95.

- Yeh, E. 2009. Greening western China: A critical view. Geoforum 40 (5):884–94.

- Yusoff, K. 2013. Geologic life: Prehistory, climate, futures in the Anthropocene. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 31 (5):779–95.

- Yusoff, K. 2019. A billion black Anthropocenes or none. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Zhang, H. 2015. Uranium supplies: A hitch to China’s nuclear energy plans? Or not? Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 71 (3):58–66.

- Zhou, J. 2006. The rich consume and the poor suffer the pollution. ChinaDialogue, October 27.