ABSTRACT

Spa destination branding as a niche within health tourism has been comparatively little addressed in the relevant scientific literature at present. This is a gap in research, the need for positioning on highly competitive national and international health tourism markets is necessary to ensure continued existence and economic success. The COVID-19 crisis intensifies this pressure on destinations and spa operations. Five spa destinations, linked through public ownership structures, launched a joint brand development process. The first phase, under the guidance of leading consulting firm “BrandTrust”, accompanied by experts of Deggendorf Institute of Technology, was completed in 2021. The concept is now being rolled out in the destinations, for which three strategic projects have been defined. In the article, this participatory approach to the development of a tourist brand is presented and analysed. The importance of the orientation on common values through branding is showed on the example of the underlying case which is an ongoing process of development. The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

“Health is a resource for everyday life. It is a positive concept, emphasizing social and personal aspects, as well as physical capabilities” (Puczko & Stackpole, Citation2021). As one of the megatrends and aims in life, health shapes all areas of life, industries, and companies (Zukunftsinstitut GmbH, Citation2021). One such industry is (health) tourism, which comprises numerous companies. Health- and wellness-based products and services have become a crucial part of the product range in the tourism industry (Boga & Weiermair, Citation2011) and must be seen as important assets to shape the profile of destinations. Apart from the mentioned megatrends, the current COVID-19 pandemic has a tremendous impact on health tourism. The pandemic increased people's awareness concerning health and well-being (Choudhary & Qadir, Citation2021). Even before the pandemic started, the share of wellness tourism in the global wellness economy was immense (Choudhary & Qadir, Citation2021).

The first section of this case study discusses branding in the tourism and spa industry. It then funnels into a specific destination and a certain case. The case addressed here is divided into three parts. These begin with a description of the initial situation encountered at the five thermal spas in Lower Bavaria. This is then followed by an outline of the process comprising a brand concept development, after which focus is placed on the implementation of a spa strategy and lastly an outlook into its further development. On the basis of these practical experiences and observations throughout the process, assumptions and theses are formulated which can be a starting point for further structured research on the topic.

The authors of this paper have participated in the strategic realignment process of the five Lower Bavarian thermal baths and are part of the implementation. Therefore, the article is based on the experiences in course of participatory observation and represents the status quo after the first phase of the strategic realignment which is still ongoing work in progress.

Branding in tourism and spa industry

“Destination” expresses a new understanding of the limitations, function, and areas of responsibility of tourist destinations, according to which they are separate competitive units in the travel industry (Steinecke & Herntrei, Citation2017). Additionally, the term “destination” not only includes tourism per se, but also other areas such as business location, living space for locals, and their administrative and design unit in political terms (Fischer, Citation2018).

As there are countless destinations, it is important to draw distinctions between them. A key tool for doing so is branding: the development of a suitable brand and the consistent and systematic use of this brand. In Germany only, there are more than 350 health spas and health resorts (Deutsche Zentrale für Tourismus e.V., Citationn.d.) and this bare number shows the importance of distinguishing the destinations by more than their indication focus. A clear and distinguishing position is essential in order to be recognised as market participant.

According to Esch (Citation2014), branding includes all specific brand-building measures that are suitable for differentiating offerings and which are suitable for enabling offerings to be recognised as belonging to a specific brand. Branding aims to aid and enable identification with the brand and differentiation from the competition (Schmidt, Citation2015).

Engl (Citation2017) compares branding to an iceberg. The small, visible part of an iceberg inspires admiration, but the real power lies “hidden” (Engl, Citation2017). The brand strategy makes up 85% of the work, is the invisible part of the iceberg, and is responsible for the “cause” (Engl, Citation2017). The credibility, differentiation, attractiveness, and sustainability of the brand, are summarised in a so-called one-word value (Engl, Citation2017).

Additionally, brand management not only focuses on its effect to the outside, but Thilo (Citation2022) points out the importance of the inwards perspective of a brand which is also focused on in the strategic realignment process of the Lower Bavarian thermal baths.

The task and challenge for all involved is to manage, develop and present the brand in line with these core values; with all the possibilities that product development, experience design, and marketing offer in tourism destination management. Destination management is not only a managerial practice but more a multifaceted social phenomenon which needs to be considered a holistic approach consisting of three viewpoints namely stakeholder theory, ethical theory and branding theory (Botterill et al., Citation2013). Wang and Xiang (Citation2007) proposed a theoretical framework for destination management which is one part of destination management and which includes preconditions, motivations and processes as well as outcomes of destination marketing alliances and networks.

Particular challenges for tourist destinations arise from the fact that several providers exist within a given destination: the destination’s brand is often supplemented by numerous other brands belonging to the individual service providers. There are different ways of dealing with this: umbrella brand vs. family brand.

A family brand system, which is also referred to as a House of Brands (Engl, Citation2017) describes a strategy, in which products profit from family brands and their already developed image, e.g. Nivea (Esch, Citation2014).

An umbrella brand system is also referred to as a Branded House (Engl, Citation2017). In this strategy, all of a company’s products are led by one brand. The company’s profiling and competence are the main focus of this strategy, e.g. BMW (Esch, Citation2014).

Destination branding became a key tool for managing the experiences made by people who visit a destination (Almeyda-Ibáñez & Babu, Citation2017). Brand equity, which covers different approaches and dimensions, has become a crucial part of branding. For instance, performance, social image, price/value, trustworthiness, and identification/attachment are five dimensions which were recognised by Almeyda-Ibáñez and Babu (Citation2017).

These theoretical considerations led to two challenges that the partners had to face in the specific project being addressed: first, the development of a common value system as the basis of a brand, and second, the question of how cooperation between the various partners can be organised and how the individual brands can be brought into harmony.

A successful example for destination branding is the Allgäu GmbH which was founded in 2011 (Wezel & Weizenegger, Citation2016). This company consists of many different stakeholders of the region and any company which fulfils four of six commonly defined criteria, e.g. certain quality standards, can become a member and use the Allgäu brand (Wezel & Weizenegger, Citation2016). The present case consists of several stakeholders but still is mainly limited to the district administration which could be extended in the future. Another example for successful destination branding is South Tyrol. This destination brand exists since 2003 and keeps developing ever since (Autonome Provinz Bozen, Citation2022). The development of the touristic region and the challenges of destination management, especially in the named region, are scientifically accompanied and researched by a local research centre for decades (Pechlaner, Citation2019). An identity model for the destination in order to implement the local stakeholders cooperation is applied in South Tyrol (Philipp et al., Citation2022).

The initial situation – five thermal spas in Lower Bavaria

The five Lower Bavarian health and thermal baths, namely Bad Birnbach, Bad Griesbach, Bad Füssing, Bad Abbach, and Bad Gögging, in which the district of Lower Bavaria has a 60% stake each, have undergone considerable change in the bathing industry over the past 30 years. Health resorts and spas in Germany are traditionally focused on medical wellness although health tourism in general ranges from spa tourism to medical tourism. One of the changes in this branch is the shift from the first to the so-called second health care market which is described as the consumption of health-related products and services which is privately financed (Pforr & Locher, Citation2012). While, at the beginning of the 1990s, the water areas in almost all pools had to be greatly enlarged due to increasing demand for outpatient spa treatments, around 10 years later the prescribed baths and medical services began to decline. As a result, the thermal baths had to be retrofitted with additional facilities such as sauna and wellness areas (Bezirk Niederbayern, Citation2020).

The loyal bathers are becoming fewer and fewer. Leisure time behaviour is changing, resulting in declining visitor numbers and thus declining income (Bezirk Niederbayern, Citation2020).

Added to this, competition in the markets has increased in recent decades due to the emergence of numerous new offerings in wellness tourism, the professionalisation of such offerings, and an increasingly difficult market situation (Allied Market Research, Citation2022; GlobeNewswire, Inc., Citation2022; Yeung & Johnston, Citation2018). Moreover, changes in demand have forced providers to widen their offers to an extent which goes beyond the use of medicinal mineral water (Pinos Navarrete & Shaw, Citation2021). Additionally, there were significant changes in the health care and health tourism market in the past two decades which is why health resorts and spas were forced transform dramatically (Pillmayer et al., Citation2021). This makes cooperation and staying competitive all-the-more essential because not cooperating with others means that potential synergies are not exploited, and important resources are wasted. Therefore, the district authority of Lower Bavaria (Bezirk Niederbayern) decided to commission the strategic realignment process with the help of external company BrandTrust.

Following targets were defined for this process:

Finding beneficial similarities (focal points/strengths/offerings) within the group (including within the individual region),

successfully positioning and marketing them and,

enhancing the individual profiles to attract defined target groups,

increasing the attractiveness of the offers for guests and their well-being and to bind them to the region long-term (Gietl et al., Citation2021d).

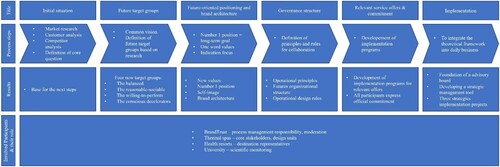

In order to reach these goals, a team consisting of members of the district authority, the five Lower Bavarian thermal spas, the spa directors, and a university expert had to complete four work packages: (1) future target groups, (2) future-oriented positioning and brand architecture, (3) governance structure, and (4) relevant range of services. The process was performed over a period of six months in 2021.

As a starting point of the process a common vision, which is the number 1 position at the same time, was formulated: The spa community (Thermengemeinschaft) aims to become Europe's leading association for holistic health for the improvement of quality of life.

In order to successfully (re-)position the five thermal spas on the market, it is necessary to define the future target groups as well as attractive offers. Those defined target groups shall be bound to the region for a long period of time by creating a relationship. The definition of the future target groups will be described in the next chapter. After the target groups are defined, the next step is to clarify the positioning.

In course of the realignment process, the positioning for all five thermal spas as well as for the spa community was defined as a so-called number 1 position. This number 1 position is a phrase which represents the brand or company and is a long-term goal at the same time. The number 1 position includes the branch in which the company is located, the geographical frame in which it acts or wants to reach the goal and the purpose, respectively the added value it wants to provide.

The number 1 positions of the five thermal spas are illustrated in . This table also shows the one-word value of the five thermal spas. The one-word value is the compaction of the number 1 position into one word/phrase, e.g. for the spa community it is quality of life (Gietl et al., Citation2021c). The table additionally shows the possible indication focus and the effects which results from a stay in the according thermal spa in order to highlight the holistic approach and to create a harmonious impression for the guests. That is important for the credibility and attractivity of the thermal spas as well as for the differentiation from competitors which was mentioned previously (Gietl et al., Citation2021b; Philipp et al., Citation2022).

Table 1. No. 1 positions, one-word values and their respective indications and effects by BrandTrust (Gietl et al., Citation2021d).

The process – developing a brand concept

According to Koch (Citation2017), the integration, in terms of coordination and communication of all stakeholders within destinations is essential for the creation of a long-term, binding relationship. As stakeholders have different interests and roles in the destination, it is therefore impossible to summarise all stakeholder interests into one indicator (Kozak & Kozak, Citation2016). Consequently, one aim of the strategic realignment process was to bundle the interests of all stakeholders of the five Lower Bavarian thermal spas and to find a path towards more togetherness going forward. In addition, branding supports destinations to create and communicate a unique identification in order to differentiate from competitors and to attract tourists (Molinillo et al., Citation2022), which was another aim of the realignment process.

Branding process

The strategic realignment process consisted of four work packages over a six-month period. The group of managers of the thermal baths, the spa administration managers, a mayor and an expert of a Bavarian University developed the future target groups of the spa community.

The market and competitor analysis

The market analysis can be divided into four parts: the area, market potential, the size and volume of the market, and the growth and dynamics of the market (Hommer, Citation2020). BrandTrust developed a market analysis based on sound research: Germany has some 3000 thermal spas and baths. More than 200 of these are located in the approx. 350 health spas and health resorts. In Bavaria, 5.72 million arrivals and 24.3 million overnight stays account for an annual revenue of 4.5 billion euros. Accordingly, every fifth overnight stay takes place in the Lower Bavarian health resorts. Given that the trend towards outpatient treatments at public health providers is constantly decreasing, it is essential that independent products and services are offered in order to ensure that the health resorts remain part of the health infrastructure. The health resorts need to establish which of the 12.9 million people, who are interested in health vacation, can be attracted to the five Lower Bavarian thermal spas.

With this in mind, it is necessary to determine what orientation and position the five thermal spas should adopt for the future. In recent years, the conditions for operating the thermal spas have changed for already mentioned reasons. Guest behaviour has also changed. Lengths of stay have decreased, for example. Added to this, it has become more difficult and less possible to process settlement of payment for treatments with healthcare providers. Coping with the existing and occurring challenges and staying competitive necessitates a strategic realignment process (Gietl et al., Citation2021d).

Customer analysis and target groups

As a conceptual basis for the definition of target groups, societal trends on different levels and in different fields were analysed: megatrends, socio-cultural trends, travel trends, and health trends (Gietl et al., Citation2021c).

Based on sound analyses, four future target groups were developed and described. The first target group, “the balanced”, comprises approx. 5.1 million people, aged 48 years on average. The “balanced” see the harmony of mind and body as the basis for health and prefer activities that affect mind and body alike. They want to feel good, and health is a question of consciousness for them. Also, sustainability is very important to them.

The second target group, “the reasonable-sociable”, consists of about 7.7 million people, aged 40 years on average. They exercise for their health, both as a balance to work, but also because they value the aspect of sociability within a group. They also do activities as a family or in order to socialise with friends. They are open to many health offerings in the field of nutrition, nutritional supplements, apps, and online fitness. They consciously allow themselves time-outs from everyday life, e.g. by making use of stress-reducing prevention.

The third target group, “the willing-to-perform”, comprises some 5.6 million people, aged 47 years on average. Health is a prerequisite for performance for this target group, which is why they want to continuously improve in the areas of sport, fitness, and health. They see themselves as role models. For them, self-optimisation and health go hand in hand. Every aspect is well-coordinated: their environment, their equipment, and their optimised diet. This target group consists of networkers who also like to be guided by professionals and seeks out the competitive aspect in sports.

The fourth future target group comprises about 5.2 million people, aged 47 years on average. For them, fitness and wellness go hand in hand. They are looking to keep their body healthy and have a clear head. They attach great importance to these goals. This group likes physical activities such as yoga and qi gong, but also going to the gym, hiking and swimming. They have a need to enjoy themselves and are aware of high-quality nutrition.

It is notable that age and demographic data are not the only parameters for defining target groups. They also differ greatly in terms of their travel and health demands and needs. All of the above-mentioned target groups can be attracted by all five thermal spas (Gietl et al., Citation2021d).

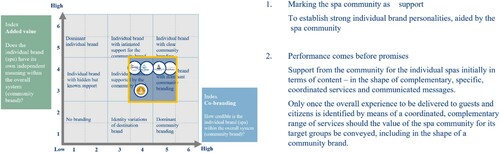

In the further process, the brand architecture is analysed. illustrates the outcome of the categorisation of the thermal spas in the context of single brands and community brand. The thermal baths are classified on a matrix with two axes which are the added-value axis and the matching values axis. All of them are located in a relatively close area. In this area, companies are characterised as single brands with community brand support and as community brand dominated single brands.

Figure 1. Consequences from the brand architecture analysis by BrandTrust (Gietl et al., Citation2021d).

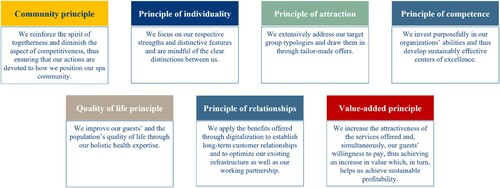

In the next step in the realignment process, seven operational principles for future cooperation between the spas and destinations involved were developed. Those principles, shown and described in , serve as framework of interaction in order to reach the common goals and to attract the future target groups which were defined earlier.

Figure 2. Operational principles by BrandTrust (Gietl et al., Citation2021d).

All the above-described steps led to the last step: this ultimately gave rise to the operational design rules namely quality of life, health competence, relationship, attraction, appreciation and recognition.

The last component of the theoretical part of the strategic realignment process involved acquiring the commitment of all participants to the strategic realignment and its implementation. The achievements committed to cover the four aspects: (1) the definition of the spa community; (2) the goals and direction of the spa community; (3) summary of the self-image; (4) definition of design rules. The six design rules determine the direction that further development should take.

The status quo – implementing a spa strategy

The status quo of the described strategic realignment process of the five Lower Bavarian thermal spas is as follows. The theoretical component has been accomplished. It comprised the above-mentioned aspects of a branding process. The implementation of the theoretical work started in September 2021. The first steps involve founding the strategic advisory board and developing a strategic management tool.

In addition to these measures, which relate to the creation of an appropriate structure to organise and manage the common brand, projects for the implementation of the brand have also been defined. The participants jointly developed three strategic projects:

Competence centre for health and tourism

The competence centre is a cooperative project between the participating spas, destinations and the regional campus of the Bavarian university. In this competence centre, projects are to be developed and implemented that strengthen the positioning of health tourism providers in the participating destinations. The development, staging and marketing of competitive offers and the development of a quality management system are among the focal points to be advanced in this cooperation project. This project is intended to strengthen the competence of the individual brands and also of the joint brand and to enhance the profile and positioning on the health tourism markets.

Digitisation project

This is a lead project that is intended to drive forward the digitisation of the partners involved. The entire service chain is to be digitised and backed up by appropriate processes. The aim is to increase service quality and thus customer loyalty. Digitisation in the destinations is also a prerequisite for more efficient and effective joint marketing of the five destinations under a common brand. In addition, digital data tracking can be used to better understand customers (Scuttari et al., Citation2022).

BGM Lower Bavaria

The focus of the involved spas and health service providers is to be on the health management in companies (“BGM”). In addition to private guests, this will serve a market niche. For this purpose, different indication-based health offers are to be developed in the five destinations of the spa community, which can present themselves under the joint brand as an attractive overall offer for health promotion in companies.

The significance and importance of these initial projects defined in the process of developing the common brand cannot be underestimated: In addition to the specific benefits for the destinations and businesses that these projects will bring, they also strengthen the cohesive power between the brand partners involved.

Beyond the brand concept, the “Thermengemeinschaft” (spa community) is thus also given specific tasks from the very beginning and is brought to life through those. In this way, a common bond is created not only through the values of the brand and the commitment to this umbrella brand, but also through specific, tangible and plannable tasks that are connected with corresponding responsibilities for the partners involved.

This ensures the establishment of the brand especially in the difficult initial phase, in which the partners still have to find themselves in their role as part of the common brand and further companies in the destinations still have to be convinced and motivated. The concrete projects unite the partners not only under mutual values but also through precise common goals and tasks.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that the strategic realignment process of the five Lower Bavarian thermal spas aims to be an umbrella brand without being a geographic destination brand. This conclusion also contains an outlook and shows the importance of bundling competencies. Moreover, summarises the strategic realignment process which can serve as a blueprint for other destinations.

Theses and learnings from the strategic realignment process:

Common Values: According to Engl (Citation2017), the basis of a brand are common values which are summarised in a so-called one-word value. Common values are crucial for the holistic approach and the harmonious impression for the guests which is essential for the credibility and the attractivity of the destination (Gietl et al., Citation2021b).

Cooperation: According to Smith (Citation2016), the development of health tourism collaborations which focus on at least one health dimension is a current trend. That supports the strategic realignment process and the further development of the spa community in Lower Bavaria. The necessity of stakeholder integration and a deep anchoring of the brand in the destination are crucial.

Sharing of knowledge and resources: the spa community creates competence centres. The first competence centre in creation is HR and it consists of roles, functions, tasks, processes and rituals (Gietl et al., Citation2021a), which will be valid for the spa community and all competence centres to come.

Ongoing process of further development: branding is a process which is never completed (Steinecke & Herntrei, Citation2017) and as the spa community committed to change, the wealth of potential can be implemented step by step. The three previously named strategic projects are the firsts steps of implementation. It is essential to keep this process going and it is even more important to bring it to life after the realignment.

Staying competitive: as the wellness tourism industry is said to further grow in the next years (Statista, Citation2021), it is more important than ever to stay competitive.

It is crucial not to forget that this process is constantly going on and changes often cannot be seen immediately. Therefore, it is important to keep the motivation and willingness to participate alive.

Those learnings can be seen as implications and can be applied to other destinations with similar issues in order to further develop and improve them as not only the national competitiveness is present in health tourism but also the international competitiveness could be focused on more intensely in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Corinna Pippirs

Corinna Pippirs, MA, establishes a competence centre for health and tourism with and for practitioners and therefore researches in health tourism, especially in the field of benchmarking and destination branding.

Georg Christian Steckenbauer

Prof. Dr. Georg Christian Steckenbauer is an Austrian social scientist and university lecturer in Bavaria. Steckenbauer has been Professor of Economy in Tourism Management at the Deggendorf Institute of Technology since 2017 and Dean of the Faculty at the European Campus Rottal-Inn, the first campus of a public university in Bavaria with exclusively English-language study programmes.

References

- Allied Market Research (Ed.). (2022). AlliedMarketResearch: Latest reports [Wellness Tourism Market]. https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/wellness-tourism-market

- Almeyda-Ibáñez, M., & Babu, P. G. (2017). The evolution of destination branding: A review of branding literature in tourism. Journal of Tourism, Hertiage & Services Marketing, 3, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.401370

- Autonome Provinz Bozen. (2022). Dachmarke Südtirol: Markenentwicklung. https://www.dachmarke-suedtirol.it/markenstrategie

- Bezirk Niederbayern. (2020). Mögliche Auftragsgestaltung zur Neuausrichtung der Niederbayerischen Heil- und Thermalbäder

- Boga, T. C., & Weiermair, K. (2011). Branding new services in health tourism. Tourism Review, 66(1/2), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371111127260

- Botterill, D., Pennings, G., & Mainil, T. (Eds.). (2013). Medical tourism and transnational health care. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137338495

- Choudhary, B., & Qadir, A. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on wellness and spa industry. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 4(2–3), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2021.1986970

- Deutsche Zentrale für Tourismus e.V. (n.d.). Heilbäder und Kurorte – kleine Auszeiten. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://www.germany.travel/de/erleben-geniessen/heilbaeder-kurorte.html

- Engl, C. (2017). Destination Branding: Von der Geografie zur Bedeutung (1. Auflage). UVK Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Esch, F.-R. (2014). Strategie und Technik der Markenführung (8. vollst. überarb. und erw. Aufl.). Vahlen.

- Fischer, E. (2018). Produktentwicklung im strategischen Destinationsmanagement. Studien zur Freizeit- und Tourismusforschung: Band 13. Verlag MetaGIS-Systems.

- Gietl, J., Dorfner, A., & Kubanek, N. (2021a). Erstes Kompetenzzentrum der Thermengemeinschaft: Entwicklungswerkstatt.

- Gietl, J., Dorfner, A., & Rauschl, N. (2021b). Stragetische Neuausrichtung der Heil- und Thermalbäder in Niederbayern: Stufe 2: Nr. 1-Positionierung und Markenarchitektur.

- Gietl, J., Dorfner, A., & Rauschl, N. (2021c). Strategische Neuausrichtung der Heil- und Thermalbäder in Niederbayern: Dokumentation Stufe 1: Künftige Zielgruppen.

- Gietl, J., Dorfner, A., & Rauschl, N. (2021d). Strategische Neuausrichtung der Heil- und Thermalbäder in Niederbayern: Schlussdokumentation.

- GlobeNewswire, Inc. (Ed.). (2022). GlobeNewswire by notified: Research and markets. The world´s largest market research store [global wellness tourism market (2021 to 2030)]. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2021/11/16/2335022/28124/en/Global-Wellness-Tourism-Market-2021-to-2030-Featuring-Accor-Canyon-Ranch-and-Four-Seasons-Hotels-Among-Others.html

- Hommer, A. (2020). Marke³: Ein praktischer Leitfaden zum ganzheitlichen Markenaufbau (1. Auflage). Haufe Group.

- Koch, A. (2017). Markenbildung von Destinationen. Ein wichtiges Instrument im Angebotsdschungel. In B. Eisenstein, R. Schmudde, J. Reif, & C. Eilzer (Eds.), Tourismusatlas Deutschland (pp. 110–111). UVK. https://doi.org/10.24053/9783739801766-111

- Kozak, M., & Kozak, N. (Eds.). (2016). Routledge advances in tourism: Vol. 36. Destination marketing: An international perspective. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315720050

- Molinillo, S., Japutra, A., & Ekinci, Y. (2022). Building brand credibility: The role of involvement, identification, reputation and attachment. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 64, Article 102819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102819

- Pechlaner, H. (Ed.). (2019). Entrepreneurial Management und Standortentwicklung Ser. Destination und Lebensraum: Perspektiven Touristischer Entwicklung. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH.

- Pforr, C., & Locher, C. (2012). The German spa and health resort industry in the light of health care system reforms. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 29(3), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2012.666175

- Philipp, J., Thess, H., & Olbrich, N. (2022). Towards common ground: Integrating destination, location and living space. In H. Pechlaner, N. Olbrich, J. Philipp, & H. Thess (Eds.), Towards an ecosystem of hospitality: Location, city, destination (pp. 32–41). Graffeg.

- Pillmayer, M., Scherle, N., Pforr, C., Locher, C., & Herntrei, M. (2021). Transformation processes in Germany’s health resorts and spas – a three case analysis. Annals of Leisure Research, 24(3), 310–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2020.1765399

- Pinos Navarrete, A., & Shaw, G. (2021). Spa tourism opportunities as strategic sector in aiding recovery from Covid-19: The Spanish model. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 21(2), 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358420970626

- Puczko, L., & Stackpole, I. (2021). Marketing handbook for health tourism. Stackpole & Associates.

- Schmidt, H. J. (2015). Markenführung. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-07165-3

- Scuttari, A., Ferraretto, V., & Isetti, G. (2022). Bolzano-Bozen: Living and visited spaces. In H. Pechlaner, N. Olbrich, J. Philipp, & H. Thess (Eds.), Towards an ecosystem of hospitality: Location, city, destination (pp. 170–175). Graffeg.

- Smith, M. K. (2016). The Routledge handbook of health tourism. Routledge international handbooks Ser. Taylor and Francis. http://gbv.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=4741313.

- Statista (Ed.). (2021). Global market size of the wellness tourism industry in 2020 and 2027 (in billion U.S. dollars). https://www.statista.com/statistics/1018497/global-market-size-of-the-wellness-tourism-industry/

- Steinecke, A., & Herntrei, M. (2017). Destinationsmanagement (2., überarbeitete Auflage; UTB Tourismus: Nr. 3972). UVK Verlagsgesellschaft mbH; UVK/Lucius.

- Thilo, I. (2022). Identitätsorientierte Markenführung von Destinationen: Vom Image zur identitätsbasierten Marke. In K. Scherhag & B. Eisenstein (Eds.), Images, Branding und Reputation von Destinationen: Herausforderungen erfolgreicher Markenentwicklung (1st ed.; pp. 51–63). Erich Schmidt Verlag.

- Wang, Y., & Xiang, Z. (2007). Toward a theoretical framework of collaborative destination marketing. Journal of Travel Research, 46(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507302384

- Wezel, A., & Weizenegger, S. (2016). Rural agricultural regions and sustainable development: A case study of the Allgäu region in Germany. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 18(3), 717–737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9674-6

- Yeung, O., & Johnston, K. (2018). Global wellness tourism economy: November 2018.

- Zukunftsinstitut GmbH. (2021). Zukunftsinstitut: Megatrend Gesundheit. https://www.zukunftsinstitut.de/dossier/megatrend-gesundheit/