ABSTRACT

The majority of the global terrestrial biodiversity occurs on indigenous lands, and biodiversity decline on these lands is relatively slower. Yet, robust understanding of indigenous governance systems for biodiversity and ecosystem services remains a key knowledge gap. We used the socio-ecological systems framework to study the governance of ecosystem services (ES) by an indigenous community in the Village of Kibber in the Trans-Himalayan Mountains of India. Focusing on plant-biomass removal from communal pastures, we identified the main factors shaping local governance using in-depth focal and deliberative group discussions with community members. Notwithstanding inequities of caste and gender, we found that Kibber had a well-functioning, complex, relatively democratic and inclusive system, with all households of the village involved in decision-making related to ES governance. Robust systems of information sharing, monitoring, conflict resolution, and self-organization played an important role. We found the role of institutional memory sustained by the oracle to be critical in maintaining governance structures. Our work underscores the potential resilience and importance of indigenous systems for the governance of ecosystem services.

Edited By:

Introduction

Indigenous people own, manage, or use approximately 22% of the global land area, on which almost 80% of the total global biodiversity occurs (UNEP-WCMC and IUCN Citation2016). Although biodiversity on indigenous lands is under increasing pressure, it is declining less rapidly than on other lands (IPBES Citation2019). This underlies the potential importance of indigenous worldviews, values, perspectives, knowledge, and institutions in the governance of biodiversity and ecosystem services (ES). While knowledge gaps related to ES governance were highlighted by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) in 2005, and continue to be recognized as being crucial (Mastrángelo et al. Citation2019), information about indigenous governance is particularly lacking (Winkler et al. Citation2021). There is increasing recognition that involving indigenous communities is essential for effective governance of biodiversity and ES due to their long-standing relationship with their surrounding environment, their knowledge of socio-ecological systems accumulated over time, and their ability to deal with changes and crises (Brondizio and Le Tourneau Citation2016; Berkes Citation2018).

Indigenous community governance can have positive outcomes for biodiversity and ES (Dawson et al. Citation2021), but this need not always be the case (Balvanera et al. Citation2019). Several factors determine the outcomes of governance systems, and while this has not been extensively studied in the context of ES, there is a substantial body of work examining local environmental governance in relation to common pool resources (Agrawal and Gupta Citation2005; Ostrom Citation1994; Agrawal Citation2014). Since many ES share properties with CPR, the approaches in understanding local governance of CPR could be applied to the governance of ES (Rodela et al. Citation2019).

The effectiveness of community governance structures is reliant on formulating and implementing collective rules (Ostrom Citation2015). These rules are context specific and depend on both the characteristics of the user and the ecosystem (Ostrom Citation2009). The ability of communities to self-organize and mobilize collective action is crucial for creating governance structures (Poteete et al. Citation2010; Hausner et al. Citation2012). Trust, reciprocity, and communication are key factors for enabling self-organization and collective action (Ostrom Citation1998). Ostrom proposed a set of eight design principles (Appendix 1), founded on North’s (Citation1990) conception of institutions, as conditions that build trust, reciprocity, and communication to maintain and sustain collective action (Agarwal Citation2014). These factors were further elaborated in the socio-ecological systems (SES) framework that can be used to describe community governance structures (McGinnis and Ostrom Citation2014).

We used Ostrom’s SES framework to describe an indigenous governance system for an ES, plant-biomass removal (McGinnis and Ostrom Citation2014). We aimed to describe the ES governance structures, and to identify key socio-economic and ecological variables and interactions that enabled the maintenance of the governance system. The focus of our study was a local institution involved in the governance of pasture-related ES in an indigenous agro-pastoral community in the high altitude Spiti Valley, Indian trans-Himalaya. The local institution has been managed intergenerationally and users continue to benefit from the resource. While the age of the local institution is difficult to determine, the earliest written records in Spiti date back to 630 AD and pastoralism was traditionally the main sustenance activity (Handa Citation1994). This is an especially important system for studying ES management as continued provisioning of services indicates potential management of ES trade-offs to prevent over-use and exploitation. Our work identifies the important factors that determine the robustness of the institution for indigenous ES governance.

Methods

Study area

Our study was conducted in Kibber, an agro-pastoral village located at an altitude of 4200 m above mean sea level in Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India. Spiti Valley is a mountainous cold desert with altitude ranging from 3350 m to 6700 m (Anonymous Citation2011). Temperatures range from −30°C in peak winter to 13°C in peak summer. Precipitation is received mainly in the form of snow in winter, which starts to melt in late March. The landscape is rocky, with steep slopes largely dominated by grasses and shrubs. The indigenous people of Spiti primarily practice Tibetan Buddhism. Buddhism is thought to have entered Spiti Valley around the seventh century when they were annexed by the Tibetan Empire (Tashi Citation2014). The present day religious and cultural practices have a strong influence from Tibet, as well as Bon, the group of animalist religions practiced in the region before Buddhism.

The indigenous people of Spiti Valley are notified as Schedule Tribe as per Article 342 of the Indian constitution (Tribal Development Department Citation2021). In India, Scheduled Tribes, also referred to as Adivasis, are officially recognized as original inhabitants of a land. Spiti Valley was also declared a Schedule Area under the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution by the President of India through an order in 1975 (Tribal Development Department Citation2021). Schedule Areas are areas which have more than 50% of the population belonging to a Schedule Tribe.

Administratively, each village in Spiti Valley falls under a Gram Panchayat which is the lowest level of official self-government in India, whose legal authority comes from the 73rd Constitutional Amendment, 1992 (Singh Citation1994). Multiple neighboring villages are part of the same Gram Panchayat. There are ~92 villages in Spiti Valley and 13 Gram Panchayats. The Provisions of the Panchayats (Extension to Schedule Areas) Act, 1996 or PESA ensures self-governance through the Gram Sabha (the general assembly of all the people in a village) for people living in Schedule Areas, legally recognizing the capacity of indigenous communities to strengthen their own systems of governance (Ananth and Kalaivanan Citation2017). The act recognizes traditional rights of indigenous communities over different natural resources which includes land, water, and forests and provides a legislative framework to preserve their identity and culture in a participatory manner through the Gram Sabha (Choubey Citation2015).

While the local community has these rights, an area of c. 7000 sq.km. covering all Spiti was brought under the jurisdiction of the Forest Department in 2008, by designating it as the ‘Spiti Wildlife Division’.

In December 2021, Kibber became the first village in Spiti Valley to claim rights under the Forest Right’s Act (FRA), which can further strengthen private and community rights (Thakur Citation2021). However, their claims have not yet been approved.

The Village Kibber has c. 80 agro-pastoral households. Significant cash income comes from the sale of green pea Pisum sativum. A few people are employed by local government offices or as daily wage laborers (Mishra, Prins, and Wieren Citation2003). Some people also work as tourist guides or run guesthouses or homestays, while some work as civil work contractors and taxi drivers. Families own agricultural land while most of the grazing land is common to the village (Mishra et al. Citation2003). Black pea (a local variety grown mainly for fodder) is also grown in small quantities (Revenue department, Kaza, Spiti Valley, Citation2014). Agricultural production is largely dependent on snowmelt, brought to the fields by long irrigation channels (Mishra et al. Citation2003).

The livestock reared are sheep (Ovis aries), goat (Capra hircus), donkey (Equus asinus), yak (Bos grunniens), cattle (Bos indicus), dzomo (a yak-cattle hybrid), and horses (Equus caballus). Livestock are occasionally used for meat and other products such as milk, manure, and wool. The community has access to grazing pastures near the village over an area of approximately 70–100 km2 with traditional grazing and collection rights in the pastures, where cultivation is not permitted. Relatively smaller-bodied livestock such as goats, sheep, donkeys, cows and dzomo are taken grazing every day during the summer months. The herding responsibilities are divided amongst all the households in the village, with four households responsible on any given day (Singh et al. Citation2015). Larger bodied livestock such as yak and horses are left to free-graze over most of the year except for a few weeks during extreme winter. All livestock are stall fed during the winter months. Fodder is collected from the pastures and crop fields and stored as winter forage. While livestock holdings in Kibber fluctuate based on a range of socio-economic and ecological conditions, over the last 20 years the overall livestock holdings have remained the same (Singh et al. Citation2015, Citation2020).

The nambardar or the village head is chosen from the 21 households whose ancestors were believed to be the original inhabitants of the village, on a rotation basis, with a one-year tenure. As in other villages in the valley, there is an oracle in the village considered the vassal of god.

Theoretical framework

We used the SES framework built on Ostrom’s eight design principles for self-organization and collective action in the commons (McGinnis and Ostrom Citation2014). The eight design principles are further elaborated in appendix 1.

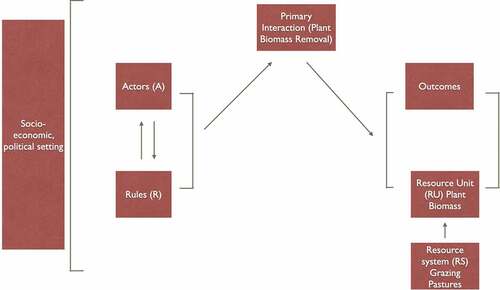

We used this framework to understand the interplay between different variables such as the roles of leadership and history, monitoring and sanctioning rules, and collective-choice rules that enable collective action for ES management. The framework has been developed as an ontologically organized, integrative set of nested, multi-tiered variables spanning multiple conceptual categories – resource system (RS), resource units (RU), governance systems (GS), and actors (A) ().

Figure 1. Diagrammatic representation of the first-tier variables of the SES framework used to study the governance system for pasture plant-biomass removal from communal pastures in Kibber village, a high-altitude agro-pastoral system in the Indian trans-Himalaya. The Resource System (RS), which is the grazing pastures, gives rise to the Resource Unit (RU), plant-biomass. The interplay between Actors and Rules leads to the Primary Interaction, plant-biomass removal, which leads to Outcomes in the resource system. The socio-economic and political setting impacts the resource system. Adapted from McGinnis and Ostrom (Citation2014)

These categories constitute the first-tier variables that are in turn comprised of second-tier variables (which can be expanded to further tiers) to help achieve greater conceptual and descriptive detail necessary for specific applications (). The main framework is the focal action situation where interactions (I) among the variables from the above categories take place to produce outcomes (O) related to the resource unit embedded within a resource system. Actors in the system make rules, and both actors and rules influence interactions. In addition, the first-tier components also interact with the broader social, economic, and political settings (S) and with other related ecosystems (ECO) (). For this case study, we focused on the actors, rules, and interactions in the system.

Table 1. First- and second-tier variables of the SES framework (McGinnis and Ostrom Citation2014) used to describe the social-ecological system for the governance of forage in the pastures in the high altitude village of Kibber, Spiti Valley, Indian Trans-Himalaya. The situation in Kibber for each of the second-tier variables is described. The variable number corresponds to the variable number in the SES framework (McGinnis and Ostrom Citation2014)

In our study system, the interaction of interest or the primary interaction was the harvest of the ES, plant biomass from the grazing pasture. Plant biomass removal occurred through livestock grazing and manual harvest for forage and wild plants for consumption and roofing.

The other interactions in the SES framework were labeled as secondary interactions. They were information sharing, conflict resolution, monitoring activities, self-organization, investment, lobbying, and networking activities. We used the secondary interactions, to understand the governance systems created for the primary interaction, plant-biomass harvest. Each of these secondary interactions was then described by the second-tier variables listed in the framework ().

Data collection

We used deliberative group discussions to collect information on ES governance. Deliberative group discussion techniques implicitly recognize the subjective element and adopt a particular strategy for dealing with subjectivity (Stern Citation2005). Free and open discussions among community members who may have different perspectives and areas of expertise are encouraged as a way to uncover bias and error in the views and conclusions of individuals. Our data and information were co-produced through extensive discussions and 10, 8-hour workshops held over 12 days with 11 participants, involving (i) 6 key informants from Kibber and (ii) 5 people who had extensive participant observation experience in the village at various times over the previous 25 years. Most of them had spent two or more years immersed in the community. The six community members are familiar with the governance structure of the community. The six community members were all men and included a mix of different castes, class, and age in the village. Women were not part of the discussion as they are unfamiliar with the governance system for plant-biomass removal. Women are more involved with water management for agriculture in Kibber (Murali et al. Citation2021). One of them was the current nambardar and one was assistant to the nambardar. Both were closely involved with the activities of the village, monastery, and the oracle.

In the workshops, the SES concepts and the variables were carefully described and discussed so that all participants had a common understanding of them. Each of the SES variables was then collectively populated based on discussions during the workshops (). The workshop was facilitated by two of the co-authors of this paper.

During the workshop the primary interaction plant-biomass removal, and the secondary interactions information sharing, monitoring, inter and intra conflict resolution, and self-organization were described using the first and second-tier variables from . The different governance structures (formal and informal) that contributed to maintaining the interaction were discussed and quantified based on their knowledge. For example, in the case of the interaction ‘information sharing’, we first enumerated the different information sharing mechanisms within the system. Second, the strength of each of these interactions was ranked by the village members, individually, on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being the lowest and 5 being the highest. Following this, they ranked the interactions again as a group. The individual and group ranks were considered similar if the average of the individual rankings varied by up to 2 points from the group rankings, and different if they varied by more. The average individual and group rankings were similar for information sharing (average individual rank: 4, group rank: 5), inter-community conflict resolution (average individual rank: 4, group rank: 4), monitoring (average individual rank: 4, group rank: 4), and self-organization activity (average individual rank: 3, group rank: 4). Individual rankings for intra-community conflict resolution (average individual rank: 1, group rank: 4) varied from the group rank. Inter-community conflict resolution in the individual ranks was considered low, however after the group deliberation, it was considered high (but lower than intra-community conflict resolution). This was because during the individual rankings, for intra-community conflict resolution, the number of conflicts in the village were considered. However, during the group discussion, it was discussed that although there were a few conflicts within the community, these were quickly resolved especially as there was a strong mechanism in place for conflict resolution. As a result, the group ranking was higher than the individual ranking. The final rankings obtained from group discussions were used.

The modes of each of these interactions were comprehensively described during the workshop and related and contextualized with respect to the secondary interactions in the SES framework. This helped us describe each interaction using the second-tier variables.

Results

Information sharing

The strength of information sharing mechanisms was categorized as 5 (highest) in the deliberative group discussions (). Collective-choice rules (GS 6) and operational choice rules (GS 5) together determined the structure of the information sharing mechanism in the system. The collective choice rules (GS 6) established the formal and informal structures that enabled information sharing (), while the operational choice rules (GS 5) were responsible for the everyday functioning of the collective choice rules. Formally, the collective choice rules enabled information sharing through meetings held among representatives of all households of the community. Operationally, these meetings were held on an average of 1–2 times a week (). The constitutional choice rules (GS 7) determine who could attend these meetings and who would have the decision-making powers at the meetings. In Kibber, men had decision-making power, and they attended all meetings, while women were allowed to only attend the meetings where information was shared.

Table 2. Secondary interactions from the SES framework (McGinnis and Ostrom Citation2014) used to describe the primary interaction, plant-biomass removal in Kibber, a high-altitude agro-pastoral village. The secondary interactions were described by the mechanisms in the system that facilitated these interactions. The presence/absence and the frequency of the mechanisms are given in column 3. The strength of the secondary interactions was quantified through deliberative group discussions with key informants and the scores are given in column 4. The scores range from 1 to 5, with 1 valued low and 5 valued high. Information sharing, monitoring, conflict resolution, and self-organization scored high, while investment activity, networking activity, and lobbying activities scored low

The role of the leader (A 5) was important in information sharing. When individuals wanted to share information such as knowledge of a potential new development in the pasture with the rest of the village, they would approach the nambardar who was responsible for calling the meetings. The legal documents, including historical documents on land rights and community rights, were also under the custody of the nambardar, which would be accessed in case information from these documents was needed.

Information on the state of the pastures, including the presence of predators, was exchanged when the household members brought their livestock to the herders for the day at a central place in the village each morning to be taken to the pastures for grazing, and in the evening when livestock were collected by the owners and brought back home from the same central place. Based on this, decisions about pastures to be grazed next were made. Here, operational choice rules were used for these informal interactions (GS 5). Kinship created strong social capital (A 6), enabling frequent informal meetings that resulted in information sharing.

The oracle, considered the spokesperson for the local deity, was a powerful influence and provided information and guidance to the community members. For example, in a recent incident, an effort to create a crop field in the pasture area by the government was stopped by the community on the instruction of the oracle.

The collective choice rules and the operational choice rules were created based on history and past experience of the actors (A 3). Kibber has traditionally been an agro-pastoral society. The constitutional choice rules (GS 7), collective choice rules (GS 6), and the operational choice rules (GS 5), have presumably been in use for generations, and the respondents at the workshop said that these rules had been passed down from the generation before theirs.

Conflict resolution

Intra-community conflict resolution mechanisms were reported to be strong, active and in use (). Livestock from the village were collectively-grazed. The rules for plant-biomass removal were traditional, based on history or past experience (A 3). The community possessed traditional grazing rights over the pasture, as recognized by the state government under the Provisions of the Panchayats (Extension to Schedule Areas) Act, 1996. Documents for these were present with the nambardar. Clear grazing rules and clarity of the resource system boundaries (RS 2), both of the village pastures and clearly defined actors, presumably reduced the chances of conflicts to arise.

Collective choice rules determined the kinds of conflict resolution mechanisms through conversation in the presence of different mediators (GS 6). Conflicts between individuals or an individual and the community were first attempted to be resolved through meetings convened by the nambardar (A 5). In case a conflict remained unresolved, discussions would take place between the actors involved in the conflict and a few selected elders of the village (A 5). As the last resort, the oracle would help resolve disagreements. The operational choice rules (GS 5) ensured the current and day-to-day functioning of the collective choice rules (GS 6).

Inter-community conflicts, mostly with neighbouring villages, included disagreements over boundaries and ownership of the grazing pastures. These were also low but higher than intra-community conflicts. Inter-community conflict resolution mechanisms were present, active and in use (). Conflicts were first resolved through dialogue between nambardars of the two communities (A 5). If this did not work, the elders from the communities (A 5) would try to resolve them, failing which the local monastery would be approached, where disagreements would be resolved by monks acting as intermediaries. The final option in conflict resolution would typically be the oracle. History or past experience (A 3) was often evoked in conflict resolution.

Monitoring

Monitoring systems were present, active, and in use (). It was scored relatively high, with a group deliberative score of 4. There were both formal and informal monitoring mechanisms which were determined by the collective choice rules (GS 6) and their everyday function by the operational choice rules (GS 5). Formal monitoring mechanisms involved a designated person sent to the pastures once a week to locate where the free-ranging livestock were and assess the state of the pasture, in order to determine if the free-ranging livestock had to be moved to other pastures. The actors’ knowledge of the resource system (A 8) enabled them to assess the availability of forage for livestock.

The state of the pastures was monitored informally frequently, as people from the community would go to the pastures to collect dung, firewood, or fodder. The herders themselves monitored the state of the pastures everyday and made daily decisions on grazing based on those assessments. The daily decision-making was enabled by the operational choice rules (GS 5) in use.

The community collectively monitored each other’s actions informally. The socio-economic characteristics of the village such as the relatively small size of the village (c. 80 HH), their proximity to each other, and kinship (A 2) enabled easy collective monitoring. Violators were reported to the nambardar or the village elders (A 5). There were sanctions (GS 8) present for rule breakers, typically in the form of monetary fines, and, at the extreme, social exclusion, which could mean exclusion from meetings and social gatherings. Constitutional choice rules determined who could make decisions on sanctions and monitoring rules (GS 7).

The oracle monitored the state of the pastures through information reportedly provided by the local deity. For example, the oracle was thought to be aware of unseasonal snow or rainfall, the locations where livestock predation was likely to occur, or if there were unauthorized users using the pastures (such as from the neighbouring village, tourists, or government designs on the pasture).

History or past experience (A 6) had a strong role to play as the structure of the monitoring system and the sanctioning rules were established traditionally.

Self-organization

Mechanisms for self-organization were present, active and in use (). Collective choice rules (GS 6) determined the structure of these mechanisms while operational choice rules (GS 5) determined the day-to-day functioning. Information was shared during the meetings and activities were then organized accordingly. The nambardar (A 5) was responsible for leading these activities by assigning roles and responsibilities to different members of the community. For example, during a drought year in 2017, when the fodder availability for livestock was low, information was first shared about the state of the pasture, following which it was decided that village representatives ask the relevant government department in the nearby urban centre, Kaza, to provide additional fodder for the livestock. Social capital (A 6) and the socio-economic attributes of the actors (A 2) such as the proximity of the households, village size, and kinship between the actors facilitated communication and self-organization.

The daily grazing of the pastures was self-organized based on the traditional grazing system. Further, this was adapted everyday based on available information (operational choice rules GS 5). Vaccination for the yaks was organized once a year (). During this period the actors self-organized to collect the yaks from the pastures (yaks are free ranging for most of the year), vaccinate them in the village, and herd them collectively back to the pastures.

The system of self-organization was based on history or past experience (A 6) of the actors in the system. The role of the oracle was limited in self-organization. However, in case of extreme or unexpected events, the oracle would encourage self-organization for action, or the actors would ask him for advice on how to act under certain situations. For example, in 2013, a government-run horse-breeding farm management located elsewhere in the valley had decided to graze their horses in Kibber’s pastures. The oracle encouraged the community members to protest the initiative and have it discontinued.

The importance of investment, networking and lobbying activities appeared to be minimal in the Kibber SES system.

Discussion

In the description of the indigenous governance system in Kibber, while some of the interactions and variables for maintaining the governance system that we found to be important have been described before in the commons literature, two important variables emerged in our system – the role of institutional memory and the role of the Oracle – that have not been commonly reported.

History, i.e the governance system has persisted through time and passed on intergenerationally, seems to have played a crucial role in maintaining the interactions in the governance system in Kibber as it was a variable listed under all four interactions. History influences the rules, norms and strategies used by communities over time; referred to as ‘institutional memory’ (Folke et al. Citation2003). In Kibber, institutional memory has been preserved through multiple channels. Official government records and documentation are kept with the nambardar or village head. User knowledge of the present day rules-in-use has been transmitted orally from the village elders to the community. The oracle is another route of transmission and holder of historical knowledge. Institutional memory is valuable in two aspects of governance: to encourage users to sustain and undertake collective action and as a basis to support knowledge to design new policies (Vázquez Citation2020). In indigenous communities, institutional memory is often based on practice and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations (Gadgil et al. Citation1993).

It is commonly acknowledged that there is a ‘poverty of history’ in the resource management literature (Johnson Citation2004, pg. 1). Fujiie et al. (Citation2005) postulated that a high level of collective action is less likely when the history of a system is short. Historical accounts help in documenting the use of the commons and establish rules based on past experience that are applicable to the local context (Unnikrishnan and Nagendra Citation2015). We saw this in Kibber where institutional memory was crucial for maintaining the governance structures. This is likely the case for most long enduring indigenous governance systems as the present day structures are based on knowledge accumulated over time.

The oracle was a recurring variable in the four interactions described. An oracle is considered a religious specialist with the power to forecast the future or answer questions through communication with or manipulation of supernatural forces (Frankle and Stein Citation2017). The oracle’s consultative and conflict-mediating functions are seen in different societies (Vernon Citation1980), and we recorded its importance in Kibber. Traditionally, SES and ES literature has not explored the role of the oracle in maintaining governance structures, though in anthropological literature, there are many in-depth studies about the role of the oracle and their importance in tribal institutions (Vernon Citation1980; Frankle and Stein Citation2017). These studies report the central role of the oracle in conflict resolution (Gluckman and Moore Citation2017), as a chronicler of history (Eno Citation1996), as religious and spiritual leader (Moreman Citation2017), and as a healer (Bates Citation1981). The remarkably influential role of the oracle in our study points to the importance of this institution in understanding indigenous ES governance.

Ostrom’s SES framework has been used extensively to describe governance structures. However, few studies have expanded on the second-tier variables. We found that second-tier variables were essential for describing the governance system. In addition to the oracle and history, we found three other second-tier variables to be important: collective choice rules, operational choice rules, and leadership.

Individuals engage in collective and operational choice rules in their every day activities (Kiser and Ostrom Citation2000). Operational activities, such as daily grazing as in the case of Kibber, are made predictable by the operational rules (Schlager and Ostrom Citation1992) that are structured and changed by collective-choice rules (Schlager and Ostrom Citation1992). Collective and operational choice rules exist in all societies in all situations, as they determine our everyday interactions with each other, and with the environment (Vatn Citation2005). In Kibber, the users created the collective and operational choice rules. In common pool resources literature, community governance is reported to be more effective when the collective choice and operational choice rules are made by the users themselves, as local knowledge about the system improves the efficiency of these rules (Agrawal and Ostrom Citation2001).

In Kibber, the nambardar (village head) was chosen on a rotation basis among a given set of households with tenure of one year. The role of the leader was central for information sharing, conflict resolution, self-organization, and monitoring. The leader was the key point of contact between the users and the larger community. Leadership is seen as crucial for maintenance of governance systems as the existence of leaders can facilitate collective action through coordination and conflict resolution (Krishna Citation2002; Olsson et al. Citation2004; Pretty and Smith Citation2004; Ostrom Citation2005).

Information sharing appeared to form the basis of other interactions such as self-organization and monitoring activities in our study system. The frequent meetings (1–2 times a week on average) created deliberative spaces, where meaningful dialogue and debate could occur (Parkins and Mitchell Citation2005). Such spaces play a crucial role in accessing a wide range of information, discussing, and debating common concerns, and revising actors’ understanding of issues (Dryzek Citation1990; Dryzek and Braithwaite Citation2000). In Kibber, the community collectively undertook monitoring. Such collective monitoring can ensure that traditional procedures are followed, provide controls on unauthorized use, favoritism, and other forms of corruption (Trawick Citation2001; Kaplan-Hallum and Bennett Citation2018). The long-term sustainability of rules depends on users’ willingness and ability to monitor each other’s harvesting practices (Quinn et al. Citation2007). A recent analysis of 130 forests located in several countries found that when local forest users were recognized as having a right of harvesting, they were more likely to monitor patterns of harvesting by other users (Coleman and Steed Citation2009). Low cost, easy to access conflict resolution mechanisms, as was present in Kibber, are considered to be key to successful local community governance (Ostrom Citation2005, Citation2008).

Conclusions

We explored a long-enduring governance structure of an indigenous community by focusing on a specific ES. Our results showed that the focal community, while having inequities related to caste and gender, represented a well-functioning, relatively democratic, and inclusive system, with all households involved in decision-making process. Our focus was on understanding the resource governance system, and we did not assess the state of the resource itself. Assessing the impact of governance structures on the state of ES is important for sustaining ecosystem health and human well-being and should be a subject for future studies.

Using Ostrom and McGinnes (Citation2014) SES framework, especially by expanding on the second-tier variables, we were able to identify important interactions and variables including unexpected ones such as the role of the oracle that contributed to collective action and ES governance. We were also able to quantify the strength of interactions, which could enable comparative analysis with other systems. The relationship between ES and human well-being is ultimately mediated by governance systems and relevant institutions that determine how decisions are taken over what issues and by whom (Huang et al. Citation2018).

Indigenous governance systems are often based on place-based experience, knowledge, and worldviews. While these maybe locally relevant, and not possible to scale-up, they offer alternatives to centralized management (Balvanera et al. Citation2019). It is important that spaces are created for the recognition and perpetuation of indigenous governance such as through the formal recognition of local rights, and inclusion of indigenous worldviews and practices, even if they might differ from the mainstream.

Ethics information

This project received ethics clearance from the NCF Research Ethics Committee from the Nature Conservation Foundation.

Appendix

Download PDF (507.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Suri Venkatachalam for encouraging us to view this system using this lens and for the numerous discussions that resulted in this paper. We would also like to thank Dr. Antonio Castro for reading the manuscript in it's early stages and providing useful comments that improved it. We are thankful to the Wildlife Conservation Network, Whitley Fund for Nature, Cholamandalam Investment and Finance committee Limited and Foundation Segré for supporting our work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agrawal A. 2014. Studying the commons, governing common-pool resource outcomes: Some concluding thoughts. Environmental Science & Policy. 36:86–91. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2013.08.012.

- Agrawal A, Gupta K. 2005. Decentralization and participation: the governance of common pool resources in Nepal’s Terai. World Development. 33(7):1101–1114. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.04.009.

- Agrawal A, Ostrom E. 2001. Collective action, property rights, and decentralization in resource use in India and Nepal. Politics & Society. 29(4):485–514. doi:10.1177/0032329201029004002.

- Ananth P, Kalaivanan S. 2017. Grassroots governance in scheduled areas in India: the way forward of PESA act. International Journal of Innovative Research and Advanced Studies (IJIRAS). 4(1):18–21.

- Anonymous. 2011. Management plan for the upper spiti landscape including the kibber wildlife sanctuary. Mysore:Wildlife Wing, Himachal Pradesh Forest Department & Nature Conservation Foundation.

- Balvanera P, Pfaff A, Viña A, García-Frapolli E, Merino L, Minang PA, Nagabhatla N, Hussain SA, Sidorovich AA. 2019. Chapter 2.1. Status and trends – drivers of change. In: Brondízio ES, Settele J, Díaz S, Ngo HT, editors. Global assessment report of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn (Germany): IPBES secretariat; p. 54–138. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3831881.

- Bates RH. 1981. The centralization of african tribal societies. In: Social science working paper. Vol. 400. Pasadena, CA: California Institute of Technology; p. 1–54.

- Berkes F, Nayak PK. 2018. Role of communities in fisheries management:“one would first need to imagine it”. Maritime Studies. 17(3):241–251. doi:10.1007/s40152-018-0120-x.

- Brondizio ES, Le Tourneau FM. 2016. Environmental governance for all. Science. 352(6291):1272–1273. doi:10.1126/science.aaf5122.

- Choubey KN. 2015. Enhancing PESA: The unfinished agenda. Economic and Political Weekly. 50(8):21–23.

- Coleman EA, Steed BC. 2009. Monitoring and sanctioning in the commons: An application to forestry. Ecological Economics. 68(7):2106–2113. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.02.006.

- Dawson N, Coolsaet B, Sterling E, Loveridge R, Gross-Camp N, Wongbusarakum S, Sangha K. 2021. The role of Indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecology and Society. 26(3). doi:10.5751/ES-12625-260319.

- Dryzek JS. 1990. Green reason: communicative ethics for the biosphere. Environmental Ethics. 12(3):195–210. doi:10.5840/enviroethics19901231.

- Dryzek JS, Braithwaite V. 2000. On the prospects for democratic deliberation: values analysis applied to australian politics. Political Psychology. 21(2):241–266. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00186.

- Eno R. 1996. Deities and ancestors in early oracle inscriptions. In: Lopez DSJ, editor. Religions of China in practice. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Princeton; p. 41–51.

- Folke C, Colding J, Berkes F. 2003. Synthesis: building resilience and adaptive capacity in social-ecological systems. In: Berkes F, Colding, J J, Folke C, editors. Navigating social-ecological systems: building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; p. 352–387.

- Frankle RLS, Stein PL. 2017. Anthropology of religion, magic, and witchcraft. 4th. Boston MA: Routledge.

- Fujiie M, Hayami Y, Kikuchi M. 2005. The conditions of collective action for local commons management: the case of irrigation in the Philippines. Agricultural Economics. 33(2):179–189. doi:10.1111/j.1574-0862.2005.00351.x.

- Gadgil M, Berkes F, Folke C. 1993. Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio. 22:151–156.

- Gluckman M, Moore SF. 2017. Politics, law and ritual in tribal society. New York: Routledge.

- Handa OC. 1994. Tabo monastery and Buddhism in the TransHimalaya: Thousand years of existence of the Tabo Chos-Khor. New Delhi (India): Indus Publishing Company; p. 167.

- Hausner VH, Fauchald P, Jernsletten JL. 2012. Community-based management: under what conditions do Sámi pastoralists manage pastures sustainably? PloS one. 7(12):51187. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051187.

- Huang NC, Kung SF, Hu SC. 2018. The relationship between urbanization, the built environment, and physical activity among older adults in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15(5):836. doi:10.3390/ijerph15050836.

- IPBES. 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. In: Díaz S, Settele J, Brondízio ES, Ngo HT, Guèze M, Agard J, Arneth A, Balvanera P, Brauman KA, Butchart SHM, et al., eds. IPBES secretariat: Bonn (Germany). 10.5281/zenodo.3553579

- Johnson C. 2004. Uncommon ground: the ‘poverty of history’in common property discourse. Development and Change. 35(3):407–434. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2004.00359.x.

- Kaplan‐Hallam M, Bennett NJ. 2018. Adaptive social impact management for conservation and environmental management. Conservation Biology. 32(2):304–314. doi:10.1111/cobi.12985.

- Kiser LL, Ostrom E. 2000. Synthesis of institutional approaches. In: McGinnis MD, editor. Polycentric games and institutions: Readings from the workshop in political theory and policy analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; p. 56.

- Kohli M, Mijiddorj TN, Suryawanshi KR, Mishra C, Boldgiv B, Sankaran M. 2021. Grazing and climate change have site‐dependent interactive effects on vegetation in Asian montane rangelands. Journal of Applied Ecology. 58(3):539–549. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13781.

- Krishna A. 2002. Active social capital: Tracing the roots of development and democracy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Mastrángelo ME, Pérez-Harguindeguy N, Enrico L, Bennett E, Lavorel S, Cumming GS, Abeygunawardane D, Amarilla LD, Burkhard B, Egoh BN, et al. 2019. Key knowledge gaps to achieve global sustainability goals. Nature Sustainability. 2(12):1115–1121. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0412-1.

- McGinnis M, Ostrom E. 2014. Social-ecological system framework: initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecology and Society. 19(2). doi:10.5751/ES-06387-190230.

- Mishra C, Prins HH, Van Wieren SE. 2003. Diversity, risk mediation, and change in a Trans-Himalayan agropastoral system. Human Ecology. 31(4):595–609. doi:10.1023/B:HUEC.0000005515.91576.8f.

- Moreman CM. 2017. Rehabilitating the spirituality of Pre‐Islamic Arabia: On the importance of the Kahin, the Jinn, and the Tribal Ancestral Cult. Journal of Religious History. 41(2):137–157. doi:10.1111/1467-9809.12383.

- Murali R, Bijoor A, Mishra C. 2021. Gender and the commons: Water management in Trans-Himalayan spiti valley, India. Ecology, Economy and society-the INSEE Journal. 4(1):113–122. doi:10.37773/ees.v4i1.378.

- North D,C. 1990. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Olsson P, Folke C, Hahn T. 2004. Social-ecological transformation for ecosystem management: the development of adaptive co-management of a wetland landscape in southern Sweden. Ecology and Society. 9(4). doi:10.5751/ES-00683-090402.

- Ostrom E. 1994. Neither market nor state: Governance of common-pool resources in the twenty-first century. Washington (DC): International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Ostrom E. 1998. A behavioral approach to the rational choice theory of collective action: Presidential address, American political science association, 1997. American Political Science Review. 92(1):1–22. doi:10.2307/2585925.

- Ostrom E. 2005. Self-governance and forest resources. In terracotta reader: a market approach to the environment. eds, Shah P, Maitri V. New Delhi: Academic Foundation; p. 131.

- Ostrom E. 2008. The challenge of common-pool resources. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 50(4):8–21. doi:10.3200/ENVT.50.4.8-21.

- Ostrom E. 2009. Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton New Jersey: Princeton university press.

- Ostrom E. 2015. Governing the commons. Cambridge university. press.

- Parkins JR, Mitchell RE. 2005. Public participation as public debate: a deliberative turn in natural resource management. Society and Natural Resources. 18(6):529–540. doi:10.1080/08941920590947977.

- Poteete AR, Janssen MA, Ostrom E. 2010. Working together: collective action, the commons, and multiple methods in practice. Princeton New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Pretty J, Smith D. 2004. Social capital in biodiversity conservation and management. Conservation Biology. 18(3):631–638. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00126.x.

- Quinn CH, Huby M, Kiwasila H, Lovett JC. 2007. Design principles and common pool resource management: An institutional approach to evaluating community management in semi-arid Tanzania. Journal of Environmental Management. 84(1):100–113. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.05.008.

- Revenue Department of Kaza, Spiti Valley., 2014. Unpublished raw data.

- Rodela R, Tucker CM, Šmid-Hribar M, Sigura M, Bogataj N, Urbanc M, Gunya A. 2019. Intersections of ecosystem services and common-pool resources literature: An interdisciplinary encounter. Environmental Science & Policy. 94:72–81. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.12.021.

- Schlager E, Ostrom E. 1992. Property-rights regimes and natural resources: a conceptual analysis. Land Economics. 68(3):249–262. doi:10.2307/3146375.

- Singh H. 1994. Constitutional base for Panchayati Raj in India: the 73rd amendment act. Asian Survey. 34(9):818–827. doi:10.2307/2645168.

- Singh R, Sharma RK, Babu S. 2015. Pastoralism in transition: Livestock abundance and herd composition in spiti, Trans-Himalaya. Human Ecology. 43(6):99–810. doi:10.1007/s10745-015-9789-2.

- Singh R, Sharma RK, Babu S, Bhatnagar YV. 2020. Traditional ecological knowledge and contemporary changes in the agro-pastoral system of upper spiti landscape, Indian Trans-Himalayas. Pastoralism. 10(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s13570-020-00169-y.

- Stern PC. 2005. Deliberative methods for understanding environmental systems. BioScience. 55(11):976–982. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0976:DMFUES]2.0.CO;2.

- Tashi T. 2014. On the unknown history of a Himalayan Buddhist enclave: Spiti valley before the 10th century. Journal of Research Institute: Historical Development of the Tibetan Languages. 51:523–551.

- Thakur NK 2021. Kibber first village in spiti village to file forest rights claims. Hindustan Times. [accessed 2022 Jan 19]. https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/chandigarh-news/kibber-first-village-in-spiti-village-to-file-forest-rights-claims-101640293155025.html

- Trawick PB. 2001. Successfully governing the commons: Principles of social organization in an andean irrigation system. Human Ecology. 29(1):1–25. doi:10.1023/A:1007199304395.

- Tribal Development Department, 2021. Tribal Areas. Accessed 2022 Jan 25. (http://himachalservices.nic.in/tribal/en-IN/tribal-areas.html)

- UNEP-WCMC and IUCN, 2016. Protected planet report 2016. UNEP-WCMC and IUCN: Cambridge UK and Gland (Switzerland).

- Unnikrishnan H, Nagendra H. 2015. Privatizing the commons: impact on ecosystem services in Bangalore’s lakes. Urban Ecosystems. 18(2):613–632. doi:10.1007/s11252-014-0401-0.

- Vatn A. 2005. Rationality, institutions and environmental policy. Ecological Economics. 55(2):203–217. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.12.001.

- Vázquez I. 2020. Toward an integrated history to govern the commons: using the archive to enhance local knowledge. International Journal of the Commons. 14(1):154. doi:10.5334/ijc.989.

- Vernon D. 1980. Bakuu: possessing spirits of witchcraft on the Tapanahony. Nieuwe West-Indische Gids/New West Indian Guide. 54(1):1–38. doi:10.1163/22134360-90002127.

- Winkler KJ, Garcia Rodrigues J, Albrecht E, Crockett ET. 2021. Governance of ecosystem services: a review of empirical literature. Ecosystems and People. 17(1):306–319. doi:10.1080/26395916.2021.1938235.