Abstract

AIDS-related stigma is a major hurdle to care and it hinders people from accessing HIV prevention methods, such as post-exposure prophylaxis. This study was designed to explore how AIDS-related stigma impacts the experience of using non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (nPEP) for HIV after sexual contact. Data were gathered in in-depth interviews with 59 people who voluntarily sought out nPEP in five public healthcare facilities in Brazil between 2015 and 2016. Data were analysed into three thematic categories: fear of being mistaken for a person living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA); desire to hide particular features of one’s sexual life; and experiences of stigmatising behaviour due to nPEP use. Based on the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework, predominant manifestations of AIDS-related stigma in each category were analysed, as well as their intersections with gender- and sexuality-related stigmas. Results show that experiences of using nPEP are permeated by AIDS-related stigma, intersecting with sexuality- and gender-related stigmas. Stigma experiences are mainly perceived, anticipated and internalised; stigma practices include prejudice and stigmatising behaviours. Taking antiretrovirals (ARVs) led participants to the fear of being discriminated against as a PLWHA and having particular features of their sexual identities disclosed. Thus, hiding nPEP was strategic to protect from stigmatising behaviour. As ARV-based prevention technologies are scaled-up, interventions designed to tackle AIDS- and sexuality-related stigmas must be expanded in Brazil. Required interventions include public campaigns about nPEP, educational programmes in healthcare settings to offer adequate support to nPEP users and investments in stigma research and monitoring.

Résumé

La stigmatisation relative au sida est un obstacle majeur aux soins et elle empêche les personnes d’avoir accès aux méthodes de prévention comme la prophylaxie post-exposition. Cette étude souhaitait explorer comment la stigmatisation relative au sida influence l’expérience de l’emploi de la prophylaxie post-exposition (PPE) non professionnelle pour prévenir l’infection par le VIH après contact sexuel. Des données ont été recueillies au cours d’entretiens approfondis avec 59 personnes qui ont demandé de leur plein gré une PPE non professionnelle dans cinq centres publics de soins de santé au Brésil entre 2015 et 2016. Les données ont été analysées dans trois catégories thématiques: crainte d’être prise pour une personne vivant avec le VIH et le sida; désir de cacher des caractéristiques particulières de la vie sexuelle; et expériences de comportements stigmatisants en raison du recours à la PPE. Sur la base du Cadre sur la stigmatisation et la discrimination dans la santé, les manifestations prédominantes de stigmatisation relatives au sida dans chaque catégorie ont été analysées, ainsi que leurs intersections avec la stigmatisation relative au genre et à la sexualité. Les résultats montrent que les expériences de l’utilisation de la PPE non professionnelle sont influencées par la stigmatisation relative au sida, qui recoupe la stigmatisation relative à la sexualité et au genre. Les expériences de la stigmatisation sont surtout perçues, anticipées et internalisées; les pratiques de stigmatisation comprennent les préjugés et les comportements stigmatisants. La prise d’antirétroviraux (ARV) a conduit les participants à craindre de souffrir de discrimination comme personnes vivant avec le VIH et le sida, et les a incités à redouter une révélation de caractéristiques particulières de leur identité sexuelle. Par conséquent, cacher la PPE non professionnelle était logique pour se protéger du comportement stigmatisant. À mesure du déploiement des technologies de prévention fondées sur les ARV, les interventions destinées à lutter contre la stigmatisation relative au sida et à la sexualité doivent être élargies au Brésil. Les mesures nécessaires incluent des campagnes publiques sur la PPE non professionnelle, des programmes éducatifs dans les établissements de soins de santé pour offrir un appui adapté aux usagers de la PPE non professionnelle et des investissements dans la recherche et le suivi de la stigmatisation.

Resumen

El estigma relacionado con el SIDA es una gran barrera para los servicios de salud y obstaculiza el acceso de las personas a métodos de prevención del VIH, tales como profilaxis postexposición. Este estudio fue creado para explorar cómo el estigma relacionado con el SIDA afecta la experiencia de utilizar profilaxis postexposición no ocupacional para el VIH después de contacto sexual (nPEP). Se recolectaron datos en entrevistas a profundidad con 59 personas que buscaron nPEP voluntariamente en cinco unidades de salud pública en Brasil entre 2015 y 2016. Se analizaron los datos en tres categorías temáticas: miedo a ser confundido con una persona que vive con VIH y SIDA (PVVS); deseo de ocultar características específicas de su vida sexual; y experiencias de comportamiento estigmatizante debido al uso de nPEP. A raíz del Marco de estigma y discriminación con relación a la salud, se analizaron las manifestaciones predominantes de estigma relacionado con el SIDA en cada categoría, así como sus intersecciones con estigmas relacionados con género y sexualidad. Los resultados muestran que las experiencias de utilizar nPEP están permeadas por el estigma relacionado con el SIDA, en intersección con los estigmas relacionados con sexualidad y género. Las experiencias de estigma, en su mayoría, son percibidas, previstas e internalizadas; entre las prácticas de estigma figuran prejuicios y comportamientos estigmatizantes. Por tomar antirretrovirales (ARV), las personas participantes tenían miedo de ser discriminadas como PVVS y de que características específicas de su identidad sexual fueran reveladas. Por ello, ocultar la nPEP era estratégico para protegerlas de comportamientos estigmatizantes. A medida que se amplían las tecnologías de prevención basadas en ARV, es imperativo ampliar las intervenciones diseñadas para combatir los estigmas relacionados con el SIDA y la sexualidad en Brasil. Entre las intervenciones necesarias figuran campañas públicas sobre nPEP, programas educativos en establecimientos de salud para ofrecer apoyo adecuado a usuarios de nPEP, e inversiones en investigaciones y monitoreo del estigma.

Introduction

The recent resurgence of the HIV and AIDS epidemic in Brazil and other high- and middle-income countries has been marked by increased numbers of HIV infections in groups that are marginalised and severely discriminated against.Citation1 In Brazil, in 2017 the number of new HIV infections exceeded 42,000, with an annual increase of approximately 5% in the past three years.Citation2 While HIV prevalence in the general population is estimated to be 0.6% in the country,Citation2 it reaches 4.8% among female sex workers,Citation3 4.9% among people who use drugsCitation4 and 18.4% among men who have sex with men (MSM).Citation5

Combination prevention approachCitation6 is considered a promising means to reverse this situation. This approach recommends that HIV prevention programmes implement complementary behavioural, biomedical and structural prevention strategies, offering all preventive methods that are proved to be efficient. This includes methods based on the use of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs), like those used by non-infected individuals before (pre-exposure prophylaxis – PrEP) or after sex (non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis - nPEP).

The estimated potential of ARV-based prevention methods to control the epidemicCitation6 has led to declarations of the possibility of ending AIDS by 2030.Citation7 Based on that assumption, a major shift has taken place in HIV-infection prevention policies, characterised by growing investments in the implementation of ARV-based prevention methods.Citation8 As funding for AIDS programmes has decreased globallyCitation9 and there is increasing conservatism in many parts of the world, including in Brazil,Citation10 such a shift may result in diminished investment in structural interventions, meaning those aiming to address socio-cultural, political, legal and economic factors that enhance vulnerability to HIV infection.Citation8,Citation11 In light of this, critical views have emphasised the need to continue investing in structural interventions, as cultural, political, legal and economic barriers may result in underutilisation of preventive methods.Citation8,Citation11,Citation12 As with any other HIV prevention method available, the effectiveness of methods based on the use of ARVs depends on people engaging with them, and such engagement is dependent on the broader environment in which those methods are made available.Citation12 Stigmas associated with living with HIV, with belonging to a sexual minority,Citation13 and with sex workCitation14 are recognised as playing a major role in the engagement process.

Intersections of AIDS-related stigma

GoffmanCitation15 defines stigma as a special kind of relationship between an attribute and a stereotype that is deeply discrediting of the individual. He notes that individuals manage the dissemination of information that may lead to stigmatisation, choosing to whom and under which circumstances to reveal certain aspects or experiences of their lives. This is related to the visual conspicuousness of the stigmatised: when an individual has a stigmatising feature that is known or immediately evident (e.g. race or skin colour), they have a discredited identity; when such a feature is unknown or can be concealed in social contacts (e.g. sexual orientation, drug use), the individual’s identity is considered discreditable, i.e. liable to be discredited. Maluwa, Parker & AggletonCitation16 add that stigmatisation is the social process by which the discourses and structures that underpin the circumstances of discrimination are produced and reiterated. In that sense, stigma expresses the relationships of power and domination based on gender, sexuality, class and race under which a society is organised. Thus, stigma is a broad social process that is expressed in individual, structural, and institutional relations in terms of power, privilege, and oppression.Citation16,Citation17

While sociology has provided an original and substantial contribution to stigma by focusing on a variety of socialisation processes and intersections that form a particular identity of “social discredit”,Citation15 health literature has pointed out the importance of examining the different constituent domains of health-related stigmas and how they intersect with other forms of stigma, affecting healthcare access and outcomes.Citation18,Citation19 The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework (HSDF),Citation18 for instance, “articulates the stigmatisation process as it unfolds across the socio-ecological spectrum in the context of health” (p. 2). This framework proposes breaking down stigma into its drivers, facilitators and manifestations, as well as its main outcomes and impact on health. By doing so, it helps to elucidate how the stigmatisation process operates, thus allowing identifying which multilevel interventions (considering research, programming and policy) are needed to meaningfully intervene in this process.Citation18

AIDS-related stigma often operates at the intersection of multiple stigmas. With the disease being associated initially with gay men and later with casual and commercial sex, AIDS-related stigma relies strongly on sexuality-related stigmas, based on what RubinCitation20 called the sex hierarchy. It incorporates gender-based stigmatisation, from which certain sexual behaviours are judged to be appropriate or not according to gender norms. Thus, AIDS-related stigma results in the labelling of people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA) as dangerous not only because they risk transmitting HIV, but also because the disease has been associated with previously morally condemned behaviours and identities.Citation17,Citation21 Furthermore, it affects those who have been infected with HIV, as well as those perceived as “possibly infected” or “infectious”.Citation22 As a social process, AIDS-related stigma is context-driven, and can intersect also with other forms of social marginalisation, such as those based on class, race and drug use.Citation22

AIDS-related stigma is recognised as a major hurdle to HIV prevention and care. Studies evaluating the impacts of AIDS-related stigma in the health of PLWHA show that it contributes to poorer mental health, particularly to higher rates of depression and anxiety.Citation23 It also impacts access to and use of HIV care, contributing to delaying HIV diagnosis and treatment uptake,Citation24 lowering levels of adherence to ARVs,Citation23,Citation24 and diminishing social support and usage of health and social services.Citation23 Stigma is also a major barrier to sexual communication and self-disclosure of HIV-status from HIV-positive individuals to their sexual partners, families and communities.Citation25–28

In Brazil, the social response to the epidemic – organised by governments, social movements and academia – has recognised stigma as a major challenge to be addressed, since the beginning of the epidemic.Citation29 This resulted in many campaigns and legal provisions aiming to tackle stigma and discrimination and favoured the organisation of groups in defence of the rights of PLWHA and of other groups severely affected by the epidemic. However, with increasing conservatism in the last decade, initiatives to fight stigma have lost strength. Non-discrimination campaigns have been censored by the federal government and attempts to ban debates on sexuality and gender have become frequent.Citation10,Citation30,Citation31 Meanwhile, recent studies indicate the persistence of AIDS-, sexuality-, and gender-related stigmas. A survey among members of the National Network of PLWHA found that 45% of the respondents had been discriminated against due to HIV.Citation32 In one national study, one out of four persons declared prejudice against the LGBT community, with self-declared prejudice being highest against the transgender community (one out of three).Citation33 Homophobic and transphobic violence are a major problem in Brazil, which is the country with the highest absolute number of violent murders of transgender people worldwide.Citation34 In addition, women who infringe gender norms regarding sexuality and reproduction, such as those who do sex work, who have had abortions or who live with HIV and AIDS, are severely stigmatised, which results in negative consequences for their health.Citation35

Stigma and use of ARVs for preventing HIV-infection

Concerning the effects of stigma when ARVs are used by HIV-negative individuals, there is growing literature focusing on PrEP use. Some of these studies show that marginalised groups – precisely those who would most benefit from PrEP – may not adopt the method partially due to fear of being stigmatised.Citation6,Citation36,Citation37 Possible reduced adherence due to stigmaCitation38,Citation39 and cases of discrimination against PrEP usersCitation37 are also discussed. Stigma also limits people’s willingness to demand the prophylaxis from their medical providers, as they fear that disclosing risky sexual behaviours may lead to judgmental responses and harsh treatment from providers.Citation40 Stigma also contributes to resistance by physicians to prescribing the prophylaxis, frequently on the grounds that it may stimulate risky sexual behaviours.Citation37

Although nPEP is the most widespread ARV-based prevention method and has been available the longest, there are few studies discussing the relationship between its use and different forms of stigma. nPEP consists of a 28-day ARV regimen to be started within 72 hours of exposure to HIV in order to prevent the virus from infecting the body. In Brazil, it has been available in the public health system since 2010. The existing studies on nPEP and stigma focus on how AIDS-related stigma affects access to the prophylaxis, stressing the negative attitudes of healthcare providers,Citation41 and on the association of low demand for preventive ARVs with the fear of being discriminated against or of having to disclose one’s sexual identity.Citation42 Studies on the concrete experiences of using nPEP could help shed light on how AIDS-related stigma permeates the daily lives of its users and how it affects access to and compliance with the drug regimen. This could help build on existing knowledge about preventive strategies based on ARVs, thereby providing input for the combination of prevention policies.

The analyses reported here were designed to explore how stigmatisation affects the experience of nPEP users in Brazil. We aim to better understand how AIDS-related stigma contributes to constructing conceptions about nPEP among its users and how it influences the search for and the use of this prophylaxis.

Materials and methods

We invited men and women to be interviewed who were aged 18 years or more, and who sought out nPEP at public healthcare facilities of five Brazilian cities between 2015 and 2016. Participants were recruited in the healthcare facilities where they accessed nPEP, mostly when they were attending follow-up visits at those facilities. Data were obtained as part of the Combina! Study,Citation43 a pragmatic clinical trial that analyses the effectiveness of HIV preventive methods, including nPEP. Qualitative methods were employed in the trial in order to investigate the experiences of nPEP users with ARVs in their daily lives. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Medicine, University of São Paulo (number 251/14). All participants were informed of the research aims and signed an informed consent form.

A total of 59 HIV-negative men and women accepted to be interviewed. Semi-structured interviews covered the following topics: previous knowledge about nPEP; circumstances leading to its use; impacts of ARV use on social and family relations; and perceptions about the interactions with healthcare workers at the healthcare facilities during nPEP follow-up. Stigma was addressed in all four topics with questions on: participant's previous knowledge on who could access nPEP; features from sexual partners that made them feel exposed to HIV; participants’ willingness to talk to family and colleagues about nPEP use or, otherwise, the means they applied to hide it; and their expectations on how healthcare workers would react to their demand for nPEP and to the circumstances that led them to the prophylaxis.

Interviews were conducted in Portuguese, in private rooms, by trained researchers, and lasted 40 min on average. They were audio-recorded, transcribed and loaded into NVivo 11. The accuracy of the transcripts was assessed by a researcher from the coordinating team of the study, who reviewed selected interviews comparing the audio and the transcripts. Quotes presented in this paper were translated into English by a professional translator and were reviewed by the authors. Data analysis covered the following stages: reading of the transcripts in detail; definition of thematic categories based on topics that emerged most frequently in the narratives as well as in the scientific literature on the subject; extraction of the content of the interviews according to the categories; and analysis of each category in dialogue with current literature and theoretical references on stigma and discrimination. For purposes of anonymisation, interviewees’ names were changed.

Thematic analysis involves working with how cultural models are expressed in social representations,Citation44 here comprehended as systems of knowledge, beliefs and opinions shared within a specific culture regarding a subject in the social world.Citation45 So, to perform the thematic analysis of our empirical data, we analysed how the perceptions that emerged from the experience of feeling exposed to HIV and using ARVs expressed the social representations of AIDS. Three categories on how stigma shaped participants’ experiences with nPEP emerged from this analysis: fear of being mistaken as a PLWHA; desire to keep particular features of sexual life secret; and concrete experiences of stigmatising behaviour due to the use of nPEP. Based on the HSDFCitation18, each category was then analysed in terms of drivers (e.g. fear of infection, concerns about health, social/moral judgement) and facilitators (cultural norms, legal environment, health policy) that will determine stigma “marking” (i.e. the process in which a stigma is applied to an individual). Manifestations of stigma were regarded as stigma experiences and practices. Following the HSDF, stigma experiences were analysed in terms of: experienced discrimination (i.e. one’s suffering stigmatising behaviours); internalised stigma (i.e. when stigmatised group members adopt the negative societal beliefs and feelings associated with their stigmatised status); perceived stigma (i.e. perceptions about how stigmatised groups are treated in a given society); and anticipated stigma (i.e. one’s expectations of being stigmatised by others if their health condition is disclosed). Stigma practices, in their turn, were analysed in terms of: stereotypes (i.e. beliefs about characteristics associated with a given group); prejudice (i.e. one’s negative evaluation of a group and its members); stigmatising behaviour (exclusion from social events, avoidance behaviours, gossip); and discriminatory attitudes (i.e. belief that people with a specific health condition should not be allowed to participate fully in society). Lastly, we analysed how stigma manifestations can influence outcomes for nPEP users (such as access to healthcare, adherence to treatment, and quality of life) and for organisations (e.g. laws, health policies, quality of healthcare) as well as their possible health and social impacts.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

Participants were mostly between the ages of 35 and 58 years old (43/59), self-identified as white (31/59) and Christian (37/59). The majority of men (42/59) self-identified as gayFootnote1 (25/42) or heterosexual (17/42). Women (17/59) nearly all self-identified as heterosexual (16/17), six were sex workers and eight had an HIV-positive partner. None of the participants self-identified as a transgender ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of nPEP users participating in the study, Brazil, 2019

Fear of being mistaken as a PLWHA

Perceived and anticipated stigmas were predominant in this category as participants feared being mistaken for someone living with HIV and accordingly discriminated against. Using nPEP and being uncertain about their own HIV status after being exposed to HIV made them wonder what it would be like to live with HIV and to face the stigma associated with AIDS on a daily basis. This situation made them experience the social dimension of AIDS in their personal lives:

“I don’t want to get HIV because I know it’s a real hassle. I’d have to spend the rest of my life taking these pills /…/. And then there’s the stigma from other people. I think it would be harder for me to be in a relationship, to have a partner, because people tend to stigmatize it.” (Roberto, white gay man, age 32)

Anticipated stigma, illustrated by the fear of being discriminated against as someone living with HIV, led the interviewees to avoid telling other people that they were on nPEP. It intersected with perceived stigma, when participants’ fears were based on their perceptions of how PLWHA are perceived in Brazil. “Frightened,” “embarrassed,” “ashamed,” and “scared” were words that repeatedly occurred in the explanations given for keeping the use of nPEP secret or for only disclosing it to people they felt they could trust the most.

“I was afraid. Ashamed too, you know? I only told myself, I kept it all in secret. [It was] really bad. I’m still not well. I’m really frightened, really scared, you see? But now I’ve got some psychological help.” (Aislan, white gay man, age 30)

The main outcome resulting from anticipated and perceived stigma in this category was participants taking ARVs with anxiety feelings such as worry, fear and stress, which, in turn, impacts negatively on their quality of life. Participants actively engaged in hiding their use of nPEP by: keeping the medications “well hidden” (in a purse, in a closet); taking the medication somewhere private, like a bathroom, or in public yet anonymous places such as a subway; and removing the labels from the bottles. Hiding the ARVs from family members was a major concern.

“[Taking nPEP] was really hard in the beginning. [I was] really irritated, I kept arguing with my mother, then I thought ‘but she doesn’t know what I’m going through. And she can’t know.’” (Eleonora, brown heterosexual woman, age 38)

Desire to hide particular features of sexual life

Hiding the use of nPEP also represented for participants a way to avoid revealing certain features of their sexual life, which were usually part of the motivations that led them to search for the prophylaxis in the first place. It is worth noting, on the one hand, how internalised and perceived stigmas predominate in this category, once participants had internalised negative societal beliefs associated with their sexual identities and practices. On the other hand, in this category stigmas related to sexuality, gender and AIDS intersected, resulting in different sexual features to be hidden according to participants’ gender and sexual identities. Among women, the conditions to be kept secret were sex work or their partner’s HIV-positive status. Among men, the secrets mostly concerned being gay or bisexual; heterosexual men worried about being seen as “promiscuous” or “careless” for having had sex with casual partners, with sex workers, or with women other than their wives.

“My family has no idea [that my partner has HIV]. My family is really close-minded. They’d never accept me being with someone that is HIV-positive.” (Manuela, yellow heterosexual woman, age 42)

“Nobody at home knows I'm gay. I can't tell them. I live with my parents and have to take the ARVs secretly.” (Alexandre, white gay man, age 22)

The narratives show that AIDS- and sexuality-related stigmas are both a reason for seeking out nPEP and a cause of shame associated with the conditions that led to needing the prophylaxis. nPEP was mostly sought out because of sexual encounters deemed illegitimate for not involving emotional or marital ties, such as casual or commercial sex. The exceptions were the exposures that occurred among serodifferent couples. In addition, the perception that certain sexual encounters were risky was based on the prejudices according to which participants judged their sexual partners’ behaviour:

“After my friends heard I went out with him, they told me he has condomless sex with a lot of people. Even with transgender women. So I was worried.” (Bertha, brown heterosexual woman, age 47)

The interviews revealed that partners labelled as risky were people who agreed to have unprotected sex or who were not worried if a condom broke; exchanged sex for money; used drugs; seemed to have many sexual partners; or simply people who “someone else said” used to have unprotected sex with transgender women. In this sense, seeking out nPEP overlaps not only internalised and perceived stigmas, but also prejudice, and the combination of these stigma experiences and practices results in individuals struggling with the need to use nPEP and rationalising it as a result from having done “something wrong” or with “the wrong person”.

Experiences of stigmatising behaviour due to the use of nPEP

Most participants did not report having experienced stigmatising behaviour during their nPEP use, which might have been a result of their success in keeping both nPEP and discrediting information about themselves undisclosed to others.Citation15 However, when the management of discrediting information failed, i.e. when the use of nPEP was involuntarily disclosed, situations of stigmatising behaviour were observed. One sex worker reported facing stigmatising behaviour in her workplace due to the use of nPEP. She was accused of having HIV by her colleagues when they saw her taking the ARVs and this situation forced her to find a new place to work:

“I was at the nightclub where I worked, it was nighttime, and I was taking the pills, and the girls started saying I had HIV. Because one even said, ‘oh, my mother takes that medicine.’ /…/ So the next day I left. Because I said, ‘I don’t have it, I’m just taking ARVs.’ But then, [if I stayed there], like, if one girl was mad at me, she’d go to the room with the client and say, ‘Hey, don’t do it with her because she’s…,’ you know? Like ‘I can prove she has HIV because she’s taking the pills.’” (Rosa, white heterosexual woman, sex worker, age 39)

In healthcare facilities, managing discrediting information on the sexual experiences that led to nPEP is undesirable because it may compromise access to the prophylaxis. In these settings, participants generally reported positive and non-stigmatising experiences. Most sex workers, gay men and women who had seropositive partners did not report feeling judged for their sexual practices, but rather welcomed and cared for the healthcare workers:

“I get kind of embarrassed to talk about my work. But, you know, here people treat you really well. Like, there's no prejudice, ’cause you know some people discriminate, right? But not here, no way, nobody discriminated against me at all.” (Simone, black heterosexual woman, sex worker, age 27)

However, stigmatising behaviour emerged occasionally from healthcare workers at four of the five healthcare facilities investigated:

“You’re going through all that and it’s really hard! If I made the effort to come [to the healthcare facility] and get treatment, it’s because I’m worried, I know it’s serious. So, it wasn’t fair for the nurse to say ‘you do the wrong thing and then you come here to get the medication.’” (Eusébio, white gay man, age 31)

Despite the fact that only a small number of participants reported facing stigmatising behaviours at the healthcare centres where they accessed nPEP, it is worrisome that this arose at all.

Discussion

Breaking down the constituent domains of AIDS- and sexuality-related stigmas among nPEP users

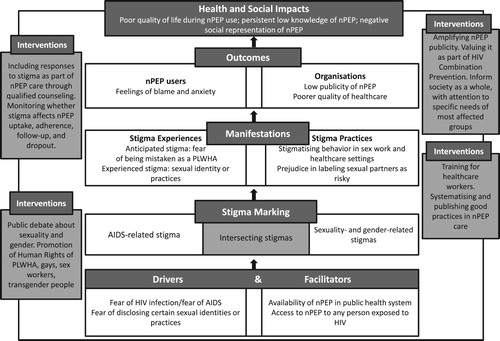

is an adaptation of the Health Stigma and Discrimination FrameworkCitation18 proposed by Stangl et al (2019) and synthesises our findings.

Figure 1. Application of the Health and Stigma Discrimination Framework (Stangl et al., 2019) to the analysis of AIDS- and sexuality-related stigmas in the experiences of nPEP users in Brazil.

Our findings show that the daily experiences of people using nPEP are permeated by AIDS-related stigma, which, in its turn, is deeply rooted in cultural norms regarding sexuality and gender. AIDS-related stigma becomes a part of their decision-making and use of nPEP and is mainly experienced as perceived, anticipated and internalised stigmas.Citation18 Regarding stigma practices, prejudice and stigmatising behaviours are also manifestationsCitation18 of AIDS-related stigma among nPEP users in Brazil.

Using nPEP led participants to reflect on what it might be like to be HIV positive. Because they recognised that PLWHA are socially discredited, meaning that they occupy a lower rank in the social hierarchyCitation15 (perceived stigma), participants’ greatest fear was to be mistaken as someone living with HIV and accordingly discriminated against (anticipated stigma). This indicates that the social attributes of AIDSCitation29 were transferred onto the uninfected individuals when they started using nPEP, causing them considerable suffering and anxiety.

Acting on internalised stigma, participants also worried that nPEP use could lead to disclosure of certain features of their sexual practices and identities. In that sense, controlling information about their use of nPEP expressed their perception of having a discreditable identityCitation15 – i.e. particular sexual features that should be kept hidden in order to avoid being stigmatised. When participants already portrayed themselves as discreditable even before searching for nPEP, the feeling of shame when they arrived at the healthcare facility (even for those who did not experience any kind of stigmatising behaviour there) and the projection of a future with HIV (anticipated and perceived stigmas), resulted in symbolising the quest for nPEP as the result of their socially rejected practices or identities.

In order to protect themselves from stigmatising behaviours and discriminatory attitudes, participants managed the dissemination of potentially damaging information (i.e. ARV use). They either hid or selectively disclosed their use of nPEP, similarly to what has been observed among HIV-positive people when it comes to the disclosure of HIV status.Citation25,Citation28 Occasions on which the strategies to hide the use of the prophylaxis failed did indeed result in stigmatising behaviours, as seen in the case of the sex worker Rosa.

Looking at the outcomes of stigma manifestations, the main individual cost of keeping the balance between adherence to nPEP and dealing with stigma manifestations is a negative impact on the quality of life of nPEP users. Not disclosing the use of nPEP made it harder for participants to sustain the prophylactic treatment for nearly a month and could result also in low adherence or loss to nPEP follow-up. We did not find direct reports of how hiding nPEP use to protect from stigmatising behaviours affects adherence, which could be due to our methodological choice of interviewing people who were attending follow-up consultations. Once we know that AIDS-related stigma hinders HIV treatment uptake and adherence,Citation46 we can argue that it could affect uptake and adherence of ARV-based prevention methods in similar ways, as fear of discrimination by family members and work colleagues could lead, for instance, to skipping doses or even to interrupting ARV use.

In terms of organisational outcomes, the predominance of positive reports in healthcare settings suggests that even though internalised, perceived and anticipated stigmas may contribute to lowering uptake of nPEP services, the occurrence of stigmatising behaviours in these settings is rare. We must consider, though, that reports of stigmatising behaviour could have been minimised due to methodological limitations, as people who have faced stigmatising behaviour in healthcare settings may have more readily abandoned their follow-up visits and, therefore, were not reached by our study. Furthermore, it is worrisome that stigmatising behaviours happened at all in healthcare settings. Considering that participants reported already feeling ashamed, tense, and anxious when they first arrived at the facilities, we understand that any incidence of stigmatising behaviours in those settings may contribute to limiting access to nPEP and to hampering the quality of care.

Lastly, regarding the health and social impacts, we note how AIDS-related stigma informs the social representation of nPEP as a prevention method that is used by people who “failed” to protect themselves, instead of simply being the most appropriate method to be used when exposure to HIV-infection has already happened. Rather than a precautionary measure of one seeking care, nPEP was represented as the result of a “bad” behaviour that should be shunned, which contributed to reinforce feelings of embarrassment, shame, and guilt among participants. This negative portrayal may have been reinforced by the conditions under which nPEP was implemented and scaled up in Brazil. nPEP implementation was late in comparison to other countries and it took place in a context of reluctance to debate ARV-based prevention methods publicly. The National AIDS Programme (NAP) included the prophylaxis in its official guidelines only after some local AIDS programmes had implemented it and after NGOs had disseminated information about it. Until 2013, dissemination of information about nPEP was limited, and almost exclusively targeted at gay men. From that year on, the NAP shifted to a stronger focus on the implementation of ARV-based prevention methods, which contributed to a wider dissemination of information about nPEP.

Key interventions to tackle stigma

The analysis of the constituent domains of AIDS- and sexuality-related stigmas in the experiences of nPEP users allows us to identify multi-level interventions that can contribute to tackling the stigmatisation process.Citation18 These interventions are also shown in .

Considering the domain of facilitators and drivers, the main facilitator to nPEP use in Brazil is its availability in the public health system, free of charge. Even though the availability has increased in recent years, efforts are needed to accelerate nPEP scale-up, reaching all regions of the country. It is also necessary to publicise nPEP, with strategies both to inform the general population and to reach the most affected groups. Having identified that the main drivers of stigma in our study were fear of HIV infection, fear of AIDS and fear of disclosing certain sexual identities reinforces the need for HIV Combination Prevention Programmes to invest in interventions aiming to change the social, political and cultural conditions that make people more vulnerable to HIV infection.Citation12,Citation47 Promoting public debate about sexuality and gender and creating strategies to defend and promote the human rights of PLWHA, gays, sex workers and transgender people are key interventions in this domain.

The predominance of anticipated, perceived and internalised stigma in the participants’ experiences with nPEP indicates that responses to AIDS- and sexuality-related stigmas must be part of nPEP care routine. Such experiences may lead to outcomes of poorer mental health and possibly of difficulties in sustaining adherence and follow-up. As these last outcomes remain to be further understood, programme monitoring must investigate whether stigma affects uptake, adherence, follow-up, and dropout of nPEP. With regard to mental health outcomes, healthcare providers can play a strategic role in providing counselling to help individuals cope with stigma during the use of nPEP. A key intervention in this domain, therefore, is offering continued educational programmes for providers to improve their counselling skills. As we found stigma practices in certain healthcare settings, such educational programmes should be human rights-oriented and aim to assure non-discriminatory practices in all healthcare facilities.

Disseminating the positive experiences that people have when looking for HIV prevention in healthcare settings may contribute to reducing anticipated stigma and to improving nPEP uptake. As the literature on interventions to mitigate stigma in healthcare settings is sparse, it is likely that local and successful experiences are not given proper documentation, analysis and dissemination. Developing a research agenda on AIDS-related stigma in Brazil can, therefore, be strategic to systematising and disseminating such experiences.

Finally, regarding the health and social impacts of AIDS- and sexuality-related stigmas on nPEP use, investments are needed to build a positive social representation of nPEP. Condoms, for instance, were widely adopted as a preventive method since the first decade of the AIDS epidemic because they were valued as a synonym of care (for oneself, one's partners, and the community), of pleasure and of the possibility to freely express one's sexuality.Citation48,Citation49 A similar process is necessary regarding nPEP in order to assure that its uptake and prescription are based on people's health needs rather than on prejudices and stereotypes around sexuality. This would also be coherent with the more comprehensive definitions of HIV Combination Prevention, which are those committed to addressing the multiple needs of protection that people may have throughout their sexual lives.Citation50,Citation51 In that sense, investments should be made to inform the public about nPEP effectiveness and to reduce the anxiety and suffering of people who have engaged in sexual intercourse with a high risk of HIV infection. Public campaigns framing nPEP as a part of prevention policy inclusive of health and sexual rights might contribute to reversing negative social representation of the prophylaxis.

Concluding remarks

Our findings illustrate how AIDS- and sexuality- related stigmas interact and impact on the experiences of HIV-negative individuals who use ARVs for prevention. Therefore, our data reinforce that, even though ARV-based prevention technologies may play an important role in HIV prevention, effective responses to HIV in Brazil depend on investments in interventions to transform the social, cultural and political conditions that make people more vulnerable to HIV-infection. This includes implementing policies that promote and protect the human rights of PLWHA and sexual minorities; offering continuous, human rights-oriented education programmes for healthcare workers; adequately monitoring impacts of stigma in health outcomes; funding research on stigma and ARV-based prevention methods; and implementing Combination Prevention programmes that are comprehensive and human rights-oriented. In order to do so, the country needs to overcome the restrictions that conservative agents have repeatedly tried to impose on HIV prevention programmes in the past decade, which have hindered HIV prevention efforts.

Using the HSDF helped us to identify and explain how AIDS- and sexuality-related stigmas operate and intersect. The analytical process of breaking it down in different domains contributed to a more precise identification of areas for intervention. Yet, as it focuses on the broader social, cultural and political constituents of stigma,Citation18 the framework helped to demonstrate that the boundaries between being “stigmatised” and being “a stigmatiser” are not precisely defined. Thus, we consider that the HSDF offers enriching analytical tools that should be further explored in future research on AIDS-related stigma.

Finally, intersections of AIDS-related stigma with other systems of oppression remain to be investigated. Studies exploring intersection of AIDS-related stigma and structural racism, for instance, could be relevant in the Brazilian context and they might benefit from the analytical tools offered by the HSDF.

Acknowledgements

The researchers thank the teams and managers of the healthcare facilities participating in the Combina! Study, and especially the participants who voluntarily agreed to be interviewed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Dulce Ferraz http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0443-3183

Marcia Thereza Couto http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5233-4190

Eliana Miura Zucchi http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6234-1490

Gabriela Junqueira Calazans http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2414-1281

Lorruan Alves dos Santos http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6169-9455

Augusto Mathias http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5896-9223

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As interviews were conducted in Portuguese, participants who were attracted to same-sex partners mostly used the term homossexual to define their sexual orientation. We translated it as gay, considering that the term “homosexual”, in English, can be considered offensive. We note, however, that homossexual, in Portuguese from Brazil, is a respectful way of defining one’s sexual orientation. What is regarded as offensive is the term homossexualismo, as the suffix “ismo” (just like “ism” in English) is associated with a deviant condition or pathology.

References

- Beyrer C, Sullivan P, Sanchez J, et al. The increase in global HIV epidemics in MSM. AIDS [Internet]. 2013 Nov;27(17):2665–2678. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00002030-201311130-00001.

- BRASIL. Boletim Epidemiológico HIV/AIDS 2018. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2018;1–66.

- Szwarcwald CL, de Souza Júnior PRB, Damacena GN, et al. Analysis of data collected by RDS among sex workers in 10 Brazilian cities, 2009: Estimation of the prevalence of HIV, variance, and design effect. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet]. 2011 Aug [cited 2019 Jun 17];57:S129–35. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00126334-201108153-00002.

- Bastos FIPM, Bertoni N. Pesquisa Nacional sobre o uso de crack: quem são os usuários de crack e/ou similares do Brasil? quantos são nas capitais brasileiras? [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: ICICT/FIOCRUZ; 2014 [cited 2019 Jun 17]. Available from: https://repositorio.observatoriodocuidado.org/handle/handle/562.

- Kerr L, Kendall C, Guimarães MDC, et al. HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Brazil. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 May;97:S9–15.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Combination HIV prevention: tailoring and coordinating biomedical, behavioural and structural strategies to reduce new HIV infections. AIDS. 2010.

- United Nations General Assembly. Political declaration on HIV and AIDS: On the fast-track to accelerate the fight against HIV and to End the AIDS Epidemic by 2030. New York. 2016.

- Monteiro S, Brigeiro M, Mora C, et al. A review of HIV testing strategies among MSM (2005–2015): Changes and continuities due to the biomedicalisation of responses to AIDS. Glob Public Health [Internet]. 2019 May 4;14(5):764–776. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17441692.2018.1545038.

- Gruskin S, Hussein J. The AIDS conference 2018: a critical moment. Reprod Health Matters. 2018;26:1510602.

- Seffner F, Parker R. Desperdício da experiência e precarização da vida: Momento político contemporâneo da resposta brasileira à aids. Interface Commun Heal Educ [Internet]. 2016;20(57):293–304. Available from: http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1414-32832016000200293&lang=pt.

- Parker R, Garcia J, Muñoz-Laboy M, et al. Community mobilisation as an HIV prevention strategy: the political challenges of confronting the AIDS epidemic in Brazil. In: Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, editor. Structural interventions for HIV prevention: Optimizing strategies for reducing new infections and improving care. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018.

- Kippax S, Stephenson N. Beyond the Distinction between biomedical and social dimensions of HIV prevention through the lens of a social public health. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2012 May;102(5):789–799. Available from: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300594.

- Gamarel KE, Nelson KM, Stephenson R, et al. Anticipated HIV stigma and delays in regular HIV testing behaviours among sexually-active young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men and transgender women. AIDS Behav [Internet]. 2018 Feb 6;22(2):522–530. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10461-017-2005-1.

- King EJ, Maman S, Bowling JM, et al. The influence of Stigma and discrimination on female Sex workers’ access to HIV services in St. Petersburg. Russia. AIDS Behav [Internet]. 2013 Oct 23;;17(8):2597–2603. [cited 2019 Mar 14]; Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10461-013-0447-7.

- Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: A Touchstone B Publ by Simon Schuster Inc.; 1963.

- Maluwa M, Aggleton P, Parker R. HIV- and AIDS-related stigma, discrimination, and human rights: A critical overview. Health Hum Rights [Internet]. 2001;6(1):1–20. [cited 2019 Mar 14] Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4065311?origin=crossref.

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2003 Jul;57(1):13–24. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953602003040.

- Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, et al. The health stigma and discrimination framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med [Internet]. 2019 Dec 15;17(1):31, Available from: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3.

- Turan JM, Elafros MA, Logie CH, et al. Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Med. 2019.

- Rubin GS. Thinking sex: notes for a radical theory of the politics of sexuality. In: Vance CS, editor. Social perspectives in Lesbian and Gay studies: a reader. London: Routledge London; 1984. p. 100–133.

- Parker R. Interseções entre estigma, preconceito e discriminação na saúde pública mundial. In: Monteiro S, Villela W, editor. Estigma e saúde. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz; 2013. p. 25–46.

- Parker R, Aggleton P. Estigma, discriminação e AIDS. Rio de Janeiro: Associação Brasileira Interdisciplinar de Aids; 2001; 1–45.

- Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2016 Jul 13;6(7):e011453, Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011453.

- Mey A, Plummer D, Dukie S, et al. Motivations and barriers to treatment uptake and adherence among people living with HIV in Australia: a mixed-methods systematic review. AIDS Behav [Internet. 2017 Feb 8;21(2):352–385. [cited 2019 Mar 14] Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10461-016-1598-0.

- Bird JDP, Voisin DR. “You’re an open target to be abused”: A qualitative study of stigma and HIV self-disclosure among black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013.

- Bird JDP, Voisin DR. A conceptual model of HIV disclosure in casual sexual encounters among men who have sex with men. J Health Psychol [Internet]. 2011 Mar 7;16(2):365–373. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1359105310379064.

- Jeffries WL, Townsend ES, Gelaude DJ, et al. HIV stigma experienced by young men who have sex with men (MSM) living with HIV infection. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015.

- Bird JDP, Eversman M, Voisin DR. “You just can’t trust everybody”: the impact of sexual risk, partner type and perceived partner trustworthiness on HIV-status disclosure decisions among HIV-positive black gay and bisexual men. Cult Heal Sex. 2017.

- Paiva V, Zucchi E. Estigma, discriminação e saúde: Aprendizado de conceitos e práticas no contexto da epidemia de HIV/Aids. In: Vulnerabilidade e direitos humanos: prevenção e promoção da saúde: da doença à cidadania-Livro I. Curitiba, Paraná; 2012. p. 111–43.

- Zucchi EM, Grangeiro A, Ferraz D, et al. Da evidência à ação: desafios do Sistema Único de Saúde para ofertar a profilaxia pré-exposição sexual (PrEP) ao HIV às pessoas em maior vulnerabilidade. Cad Saude Publica [Internet]. 2018;34(7):e00206617, Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-311X2018000703001&lng=pt&tlng=pt.

- Ferraz D, Sex PV. Human rights and AIDS: an analysis of new technologies for HIV prevention in the Brazilian context. Rev Bras Epidemiol [Internet]. 2015 Sep;18(suppl 1):89–103. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1415-790X2015000500089&lng=en&tlng=en.

- Beloqui J. Violência e discriminação na RNP+ Brasil. Relatório preliminar. São Paulo; 2019.

- Venturi G, Bokany V. Diversidade sexual e homofobia no Brasil. São Paulo. Ed Fundação Perseu Abramo. 2011;190–260.

- Transrespect versus Transphobia Worldwide (TvT) Team. Trans Murder Monitoring (TMM) Update Trans Day of Remembrance 2018. Press Release. 369 reported murders of trans and gender-diverse people in the last year. [internet] Accessed 05 Jul, 2019 at: https://transrespect.org/en/tmm-update-trans-day-of-remembrance-2018/.

- Villela WV, Monteiro S. Gênero, estigma e saúde: reflexões a partir da prostituição, do aborto e do HIV/aids entre mulheres. Epidemiol e Serviços Saúde [Internet]. 2015 Sep;24(3):531–540. [cited 2019 Jan 10] Available from: http://www.iec.pa.gov.br/template_doi_ess.php?doi=10.5123/S1679-49742015000300019&scielo=S2237-96222015000300531.

- Tangmunkongvorakul A, Chariyalertsak S, Rivet Amico K, et al. Facilitators and barriers to medication adherence in an HIV prevention study among men who have sex with men in the iPrEx study in Chiang Mai. Thailand. AIDS Care - Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV [Internet]. 2013 Aug;25(8):961–967. [cited 2019 Mar 14] Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09540121.2012.748871.

- Golub SA. PrEP stigma: Implicit and Explicit drivers of Disparity. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep [Internet]. 2018 Apr 19;15(2):190–197. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11904-018-0385-0.

- Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. State-level structural sexual stigma and HIV prevention in a national online sample of HIV-uninfected MSM in the United States. Aids [Internet]. 2015 May 3. 2015 Apr 24;29(7):837–845. [cited 2019 Mar 14] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25730508.

- Keogh P. Morality, responsibility and risk: negative gay men’s perceived proximity to HIV. AIDS Care [Internet]. 2008 May 16;20(5):576–581. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09540120701867123.

- Goparaju L, Praschan NC, Jeanpiere LW, et al. Partners, providers and Costs: potential barriers to PrEP uptake among US women. J AIDS Clin Res [Internet]. 2017 Sep 25;08(09):1–8. [cited 2019 Jun 2] Available from: https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/stigma-partners-providers-and-costs-potential-barriers-to-prep-uptakeamong-us-women-2155-6113-1000730.php?aid=93928.

- Stringer KL, Turan B, McCormick L, et al. HIV-Related Stigma Among healthcare providers in the Deep South. AIDS Behav [Internet]. 2016 Jan 9;20(1):115–125. [cited 2019 Mar 14] Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10461-015-1256-y.

- Wanyenze RK, Musinguzi G, Kiguli J, et al. “When they know that you are a sex worker, you will be the last person to be treated”: perceptions and experiences of female sex workers in accessing HIV services in Uganda. BMC Int Health Hum Rights [Internet]. 2017 Dec 5;17(1):11. [cited 2019 Mar 14] Available from: http://bmcinthealthhumrights.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12914-017-0119-1.

- Grangeiro A, Couto MT, Peres MF, et al. Pre-exposure and postexposure prophylaxes and the combination HIV prevention methods (The Combine! study): protocol for a pragmatic clinical trial at public healthcare clinics in Brazil. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):1–11.

- Moscovici S. Notes towards a description of social representations. Eur J Soc Psychol [Internet]. 1988 Jul;18(3):211–250. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ejsp.2420180303.

- Rateau P, Moliner P, Guimelli C, et al. Social representation theory. Handb Theor Soc Psychol. 2011;2:477–497.

- Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc [Internet]. 2013 Nov;16:18640, Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640.

- Monteiro S, Brigeiro M. Experiências de acesso de mulheres trans/travestis aos serviços de saúde: avanços, limites e tensões. Cad Saude Publica [Internet]. 2019 Apr 8;35(4). [cited 2019 May 29] Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-311X2019000400504&lng=pt&tlng=pt.

- Treichler PA. How to use a condom. In: Disciplinarity and dissent in cultural studies. New York: Psychology Press; 1996.

- Pinheiro TF. Camisinha, homoerotismo e os discursos da prevenção de HIV/aids [Internet]. [São Paulo]: Universidade de São Paulo; 2015; Available from: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/5/5137/tde-14092015-092808/.

- Grangeiro A, Ferraz D, Calazans G, et al. The effect of prevention methods on reducing sexual risk for HIV and their potential impact on a large-scale: a literature review. Rev Bras Epidemiol [Internet]. 2015 Sep;18(suppl 1):43–62. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1415-790X2015000500043&lng=en&tlng=en.

- Ferraz D. Prevenção Combinada baseada nos Direitos Humanos: por uma ampliação dos significados e da ação no Brasil. Bol ABIA-Associação Bras Interdiscip aids. Rio Janeiro. 2016;61:9–12.