Abstract

We undertook a reproductive health study on young formerly trafficked women in Nepal using a new research method – the Clay Embodiment Research Method – designed with their vulnerability and the cultural context in mind. Following a two-month period of participant observation, six formerly trafficked women participated in a series of seven themed (clay embodiment/three-dimensional body mapping) workshops and, afterward, a group interview using photoethnography. We discovered that these women are subject to cultural stigmas other than those related to sex trafficking, such as menstrual stigma, stigma related to pre-marital sex, stigma related to pregnancy before marriage and stigma for having a female child. These can have a deep impact across the entire reproductive lives of women. As a cultural force, the stigmatisation is generated by both men and women, and has roots that lie in Hinduism and the patriarchal value system in Nepal. Nepal is attempting to address some of these issues and we recommend a public health campaign to eliminate the practice of the menstruation and other stigmatising traditions.

Résumé

Nous avons entrepris une étude de la santé reproductive auprès de jeunes femmes ayant précédemment fait l'objet de la traite au Népal avec une nouvelle méthode de recherche qui utilise la personnification par l’argile (Clay Embodiment Research Method), conçue en tenant compte de leur vulnérabilité et du contexte culturel. Après une période de deux mois d’observation des participantes, six anciennes victimes de la traite ont participé à une série de sept ateliers à thème (personnification avec l’argile/cartographie corporelle en trois dimensions) et, par la suite, à un entretien de groupe utilisant la photoethnographie. Nous avons découvert que ces femmes sont soumises à une stigmatisation culturelle autre que celle qui se rapporte à la traite sexuelle, comme la stigmatisation menstruelle, la stigmatisation relative aux relations sexuelles préconjugales, la stigmatisation en cas de grossesse avant le mariage et la stigmatisation pour avoir donné naissance à une fille. Ces pratiques peuvent avoir des conséquences profondes tout au long de la vie reproductive des femmes. Comme force culturelle, la stigmatisation est créée par les hommes et les femmes, et prend ses racines dans l’hindouisme et le système de valeurs patriarchales au Népal. Le Népal tente de s’attaquer à certains de ces problèmes et nous recommandons une campagne de santé publique visant à éliminer la pratique de la menstruation et d’autres traditions stigmatisantes.

Resumen

Emprendimos un estudio de salud reproductiva con mujeres jóvenes traficadas anteriormente en Nepal, utilizando un nuevo método de investigación, el Método de Investigación de Encarnación en Arcilla, diseñado teniendo en cuenta su vulnerabilidad y el contexto cultural. Después de un período de dos meses de observación de participantes, seis jóvenes traficadas anteriormente participaron en una serie de siete talleres temáticos (encarnación en arcilla/mapeo corporal tridimensional) y, después, en una entrevista en grupo utilizando foto-etnografía. Descubrimos que estas mujeres están sujetas a estigmas culturales además de aquellos relacionados con el tráfico sexual, tales como estigma menstrual, estigma relacionado con sexo prematrimonial, estigma relacionado con embarazo antes del matrimonio y estigma por tener una hija. Estos pueden tener un profundo impacto durante toda la vida reproductiva de las mujeres. Como fuerza cultural, la estigmatización es generada por hombres y mujeres, y está arraigada en el hinduismo y en el sistema de valor patriarcal de Nepal. Nepal está intentando abordar algunos de estos asuntos; recomendamos una campana de salud pública con la finalidad de eliminar la práctica de la menstruación y otras tradiciones estigmatizantes.

Introduction

This paper focuses on the stigma associated with reproductive health as experienced by young women who have been trafficked into the sex industry in Nepal. This group of women is highly marginalised due to the stigma they face for their involvement in the sex industry, regardless of whether they have engaged in sex work or not. However, the women also face other types of stigmatisation which this study aims to highlight. In order to contextualise the study reported, it is first necessary to consider the historical and cultural background to gender relations in Nepal, as well as the nature of trafficking and the sex industry.

Hinduism and Nepali culture

Although it is considered to be one of the most ethnically, religiously and linguistically diverse countries in the world for its small land area,Citation1 Nepal is a predominantly Hindu country, with a history of Hinduism dating back to 12.C.E. when the Liccavis from northern India invaded the country. Hinduism was entrenched in Nepali culture during the autocratic rule of Jang Bahadur Rana (1846–1877) who envisioned a pure Hindu landCitation1 and embedded Hinduism, its patriarchal value system and the caste system into the legal code, the Muluki Ain of 1854 (MA of 1854). Sharma (cited in HöferCitation2) says that the MA of 1854 is unique in that there “is no other instance of caste validation accorded to a legal document of a state like this from anywhere else in the subcontinent” (p.xvi)Footnote*, referring to the South Asia subcontinent.

The MA of 1854 shaped present-day Nepali culture. It remained largely unchanged during the long rule of the Rana Family (1845–1951). It is a complex document that set up controls over the hierarchy of people of different ethnicities (including foreigners), touchability/untouchability of people, purity/impurity rituals, sexual relations, temporal-personal impurity (menstruation, childbirth and mourning), division of labour across the hierarchy, mobility (within the hierarchy), the role of the state (Nepal) with India, and so on.Citation2 A large part of the MA of 1854 is focussed on sexual relations. For example, it contains “Six Rules of Forbidden Sexual Intercourse”, with Rule 5 largely denying women the right to have sex. In Hinduism, women’s sexuality is believed to endanger and affect men’s sexualityCitation3,Citation4 because it is viewed as a source of pollution for men. Sex work is considered as particularly polluting, and women who engage in sex work in Nepal – by free choice or coercion – are reduced to “low caste”, “Dalit” or “untouchable” on the caste hierarchy, regardless of their ethnicity. Further, the MA of 1854 codifies a woman who has slept with three men in her life as “wesyā” or “besyā” [whore],Citation2,Citation5 a particular source of stigma for trafficked women.Citation6,Citation7 This stigma affects the women, their families and village communities, including in an intergenerational way, which is a particularly problematic issue in South Asia.Citation8

Stigmas of trafficked women

In conceptualising stigma, we defer to a framework developed by Link and PainCitation10 which acknowledges stigma from a sociological perspective and focuses on the psychological and structural pathways of stigma which influence health. Notably, stigma is also asserted to be a driver of population health.Citation11 Hatzenbuehler, Phelan and Link state (p.813):

“In this conceptualization, stigma is defined as the cooccurrence of labelling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination in a context in which power is exercised.”Citation11

The sex industry in Nepal

In Nepal, the sex industry is female-dominated.Citation12 It operates under the guise of an entertainment industry and embraces a complex infrastructure of industries such as cabin restaurants (crude constructions with private seating areas separated by plywood or curtains), including street and bhatti pasals (wine shops), massage parlours, dance bars, dohori sanjh (restaurants where traditional male and female duets are performed) and also guest houses/lodges.Citation7 Cabin restaurants, dance bars and dohoris are considered to be the “access points” for sex.Citation7 Some researchers have reported that all pathways lead to sex workCitation12 but there seems insufficient evidence for this – not enough is known about the industry because of limited research. However, the sex industry is not reported to be brothel-based.Citation7 The young age of the girls working in the industry – under 18 – is suggestive of trafficking.Citation13 While some research has been conducted with Nepal’s sex workers,Citation14,Citation15 reproductive health research is limited. Frederick et al. (p.49),Citation7 who undertook research related to the entertainment industry, argue that:

“Although comparative research has not been conducted, informal observations indicate that violence against women and girls in Nepal’s entertainment industry exceeds that of similar entertainment industries in many parts of the world, including Thailand, Hong Kong, Malaysia, United Arab Emirates, India and Western Europe.”

In our study, using a culturally sensitive research method, we explored the reproductive health knowledge of young women who have been trafficked into the sex industry in Nepal. In particular, we hoped to find out about the young women’s perceptions and experiences of their reproductive bodies; their hopes and fears associated with reproduction; and how these factors influence reproductive decision-making. Using this information, we eventually intend to develop a set of recommendations for reproductive health support and reproductive health education for young trafficked women in Nepal for relevant agencies in Nepal. We discuss four stigmas that the trafficked women revealed in the course of discussing their reproductive health knowledge: menstrual stigma, stigma related to pre-marital sex, stigma related to pregnancy before marriage and stigma related to having a girl child. We argue that each of these is rooted in Hinduism and its patriarchal norms, and demonstrate how, as Fikree and Pasha (p.823)Citation9 have reported in other South Asian contexts, such stigma has significant consequences such as:

“Gender discrimination at each stage of the female life cycle contributes to health disparity, sex-selective abortions, neglect of girl children, reproductive mortality, and poor access to health care for girls and women.”

Methods

Study setting

Our study was undertaken between February 2014 and January 2018. Data were collected between November 2015 and April 2016 in Kathmandu. Data collection was time-limited due to funding and visa constraints. For the study we partnered with Asha Nepal and the Centre for Awareness and Promotion (CAP) Nepal, local non-government organisations (NGOs) which both work with women and girls who have been sexually abused or trafficked for sexual exploitation. Data collection occurred on the premises of these organisations because of their familiarity for the women, and their accessibility by public transport for those participants who were living away in the community. Counsellors and psychologists were available to the women at these settings.

Study participants

Women were recruited to this study by purposive sampling. The selection criteria were that the women were born in Nepal, had been but were no longer working in the sex industry, and had entered the reproductive life stage (i.e. begun menstruating). No exclusions were placed on the women’s ethnicity, religion, district of origin, educational status, marital status, whether they had been pregnant or had children, or their pathways into the sex industry via trafficking. However, women who were pregnant, had severe psychological issues or had Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) were excluded from participating because they were deemed too vulnerable.

The six women selected were from rural regions of Nepal, had impoverished backgrounds and had been trafficked into the sex industry in Kathmandu, which is the hub of the nation’s sex industry. However, they were no longer engaged in the sex industry. summarises the demographics of the women and their pathways into trafficking.

Table 1. Demographics of study participants and their pathways into trafficking

Data collection

Our research study employed a new research method – the Clay Embodiment Research Method (CERM) – designed for the cultural context, and comprising ethnographic and (adapted) Participatory Action Research methods. The CERM is a multimethod approach which consists of three research methods: (1) a critical stage of ethnographic participant observation; (2) a series of seven participatory (clay body mapping/three-dimensional body mapping) workshops; and (3) a group interview using photoethnography. Each participatory workshop involved study participants and facilitators (namely the corresponding author of this paper [TO] and the third author [SC], a research assistant cum interpreter) and had a specific theme related to the reproductive body. The group interview involved the same people.

A pilot of the clay body mapping method and photography was undertaken prior to the study using Nepali volunteers. The menstruation workshop was used as the basis for the pilot because it was considered the most difficult for study participants to undertake using clay. lists the workshop themes and provides a brief outline of the aims of each workshop.

Table 2. Clay embodiment research method workshop themes

Participant observation took place throughout the five-month data collection period. Active participant observation of the ordinary daily activities of the study participants (in their abode and other places where they normally gathered) was made over a period of approximately two months prior to the clay workshops and the group interview being undertaken. This enabled TO and SC, a native Nepali, to gain entrée to the field, to establish trust with potential research participants, and to observe group dynamics between the young women in their living environments or shelter homes the women came to for life skills training, social support and counselling. During this time, the staff from our partner organisations and women were also introduced to the clay and all women were given an opportunity to participate in clay workshops. The audio recording process was also introduced to ensure it would be comfortable for the potential participants to be involved in. Participant observation also occurred during the clay workshops. This process was important for assessing the women’s emotional states (i.e. tones of voice and body language), responses to us and other group participants and the clay work. We noted these responses in our transcriptions, aided by information from the audio recordings. We noted significant emotional responses in text in the documentation of our findings.

The participatory workshops and group interviews were conducted over an eight-week schedule that catered to the women’s domestic, school and other obligations and routines. Due to travel unpredictability caused by a fuel shortage crisis in the country at the time, the study participants were divided into two groups: one comprising the unmarried women who resided at the study site, and the other comprising the married women for whom travel was necessary but unpredictable. One of these married women subsequently withdrew from the study after the menstruation workshop.

Each workshop and group interview lasted between 30 and 60 minutes depending on how tired the women appeared on the day. Flexible interview questions were used in both and were framed around the first three study objectives of exploring the women’s knowledge and ideas related to (1) their perceptions and experiences of the reproductive body (female and male); (2) their hopes and fears associated with reproduction; and (3) how these factors influence reproductive decision-making.

The workshops and interviews were audio-recorded. The recordings were transcribed into Roman Nepali by SC and then translated into English by her with English language support from TO. The already long transcription and translation work was repeatedly disrupted by significant electricity outages in Nepal at the time, the workaround to which (i.e. working during pre-dawn hours when power was more reliably available) resulted in fatigue for the research assistant.

All workshops and group interviews were conducted in Nepali. The contextual meaning was described to the interviewer (TO) in English in the course of the workshops and interview by SC, which may have affected the data. However, SC is female, bilingual and Nepali, close to the age of the research participants, and has a reproductive health background. She was also trained in the workshops/clay/interview process prior to the research being conducted. TO also has a basic understanding of Nepali and a significant knowledge of Nepali culture (from the Nepalese community in Australia and Nepal) and had previously worked with trafficked women in a reproductive health context in Nepal. Both interviewer and interviewees were involved in the translation of the transcripts, and the data were cross-checked by another female bilingual Nepali who also has reproductive health expertise.

Clay works produced in the workshops were photographed by the women or the facilitators, and subsequently used as the focus of the group interview. Women were given the opportunity to engage in the photography process. Some wanted to, some did not.

The transcriptions and photographs were subsequently assessed for cultural ambiguities by a second native Nepali research assistant and TO.

Analysis

The study analysed three sets of data: audio recordings of the workshop and interviews; their transcriptions and corresponding translation into English; and photographs of all clay work. Guest et al.’sCitation16 Applied Thematic Analysis was used to analyse the data, including content analysis for the photographs of the clay work. The data were analysed through the lens of intersectionality theory. We described the four dominant themes that emerged as the physical body; emotional body, cultural body and the benefits of the workshops undertaken during the research. Findings emerged from all seven participatory (clay embodiment/three-dimensional body mapping) workshops and the group interview using photoethnography. In this paper, we report on the stigmas experienced, feared or learned from others, in relation to the first three themes.

Ethics approval

This study received ethics approval from the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (DUHREC) (2015-030) and the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) (776). We received organisational consent from Asha Nepal and CAP Nepal, consent from guardians and consent from the women. Verbal and visual methods (i.e. posters and dolls) were used to gain the women’s consent to audio-record the workshops, take photographs and use the data for publication. The NHRC also required the women’s thumbprints on consent forms. Pseudonyms are used to protect the identities/anonymise the women.

Results

In our study, four stigmas associated with the reproductive health knowledge of the young trafficked women emerged as we worked through the study’s themes of physical body, cultural body and emotional body, namely: menstrual stigma (physical/cultural); stigma related to pre-marital sex (emotional/cultural); stigma related to pregnancy before marriage (cultural); and stigma related to having a female child (emotional/cultural).

Menstrual stigma

Untouchability

All the study participants described stigmatising menstruation traditions and practices carried out in their villages by women (i.e. mothers and sisters) and men (i.e. uncles, fathers and brothers) in active or, equally, passive ways. They also described attempting to resist engaging in some of the practices.

Three menstruation traditions and practices were mentioned: chaupadi [chau meaning “menstruation” and padi meaning “women”], gupha [sitting in a cave] and guniyo cholo [related to “coming of age”]. All study participants regardless of their ethnic group or religion had either experienced some aspects of the traditions or had been exposed to them by women of other ethnic groups in Nepal. Some study participants learned about the harshness of the traditions practised in other village communities. All study participants shared information about one or more aspects of menstruation traditions and practices and their related menstrual stigma – even those who were not consciously aware that they practised any traditions.

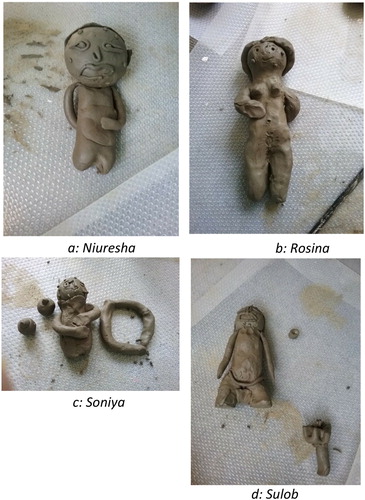

Although the study participants experienced variable menstruation practices, they seemed to hold an unconscious belief that women are untouchable at menstruation. In the menstruation workshop after the young unmarried study participants had made their menstruation clay works (see ), Sulob, from a Tamang community, made a striking statement about this issue in a group conversation in which Soniya, from a Brahmin community, talked about the harsh restrictions she had faced: “You are dirty when you are on your periods.” Notably, Sulob did not believe she had experienced any menstrual stigma. However, later in this same discussion, when describing what she knew about the process of ovulation and menstruation, Sulob then illuminated exactly what was “dirty”: “When the eggs burst, the blood comes, so our new blood develops after the dirty (blood) is gotten rid of.”

Figure 1. Clay figures made by participants conceptualising menstruation (a) Niuresha (b) Rosina (c) Soniya (d) Sulob

This concept of “dirty blood” was also mentioned later by Soniya: “It’s similar, but then our veins throw the dirty blood, then we have new blood. The eggs burst and then we have periods. I don’t know a lot about it.” Soniya’s use of “it” suggests that she was referring to not knowing about the menstrual cycle or about the process of menstruation and ovulation.

Seclusion

For three of the women in our study, the practice of seclusion at menstruation was enforced. Most poignantly, Soniya, who was with a friend in the village when she got her first period, shared how she went to her mother for support and the instructions she received: “I went to my Mum and told my Mum and she asked me to go to some other place (different house)”.

Her experience of seclusion was particularly harsh, and when describing it, she talked about other restrictions faced by women in her village community at menstruation. This is described in the following discussion between the study’s research assistant cum interpreter Sabrina Chettri (Sabrina), Niuresha, from a Tamang community, Soniya, from a Brahmin community, Rosina from a Magar community and Sulob, also from a Tamang community. In the discussion, Niuresha, having just learned about such practices for the very first time, expresses shock at the harshness of the menstruation traditions practised in Soniya’s village community:

Sabrina: What about you Soniya, since you are Brahmin? Don't you have anything?

Soniya: They hide us … You are not allowed to see in the direction of your home, no one like your brother, or any male member of the family … You call it that (“gupha”).

Niuresha: “Gupha” is where you have to stay inside the house only.

Soniya: If you have your own sister, you stay in their house, if not, in someone else’s house.

Sabrina: Do you have different places to sleep too?

Soniya: You are not allowed to sleep in a bed … On the fifth day, you are to wash all the clothes. If you were to have menstruated for the first time, you would have to wash all your clothes after 21 and then 14 and then after seven days.

Sabrina: You are sent out three times?

Soniya: Yes.

Niuresha: Baa. (She shows a shocked expression on her face)

Niuresha: Twenty one, you are sent for twenty one days outside? (referring to being in a separate house)

Soniya: I couldn’t stay so I ran away for the seventh day.

Sabrina: Nothing happens in your culture Rosina?

Rosina: No, nothing happens.

Niuresha (to Soniya): Are you allowed to go outside the room or do you have to stay inside?

Soniya: You are expected to do everything the house. People like you are to cut the grass and everything. You should not carry big loads, when you have your periods, but you are expected to carry big loads.

Sulob: What do you expect when you stay in other peoples’ house?

Soniya: You have to wake up early in the morning and bathe with cold water.

While Soniya describes the menstruation traditions as gupha, given the severe practices she described, we think it was chaupadi, which is usually the type of tradition practised in Brahmin communities. Her resistance to the practice of seclusion is evident as she said that she ran away after several days. In the discussions on seclusion practices, “sisters” – a collective term used to describe “blood sisters” and/or other women and girls in Nepalese culture – are implicated in several roles at menstruation. Aisha, from a Chettri community, illuminated an important support role played by mothers and “sisters” during seclusion rituals (noting here also a restriction related to men): “We are not allowed to see the faces of the male member of the family. Our mothers and sister used to come during the night to sit with us.”

In other words, women support each other through this period of social exclusion. At a later time, Aisha also told us that she too played this sisterly support role in her village: “I used to go and sit with my sisters when they used to menstruate.”

Soniya described another role for sisters regarding whose house a woman might be secluded to at menstruation: “If you have your own sister, you stay in their house, if not, in someone else’s house.”

So we see that women play paradoxical roles; as enforcers of traditions and as support for women. As for men, Aisha reported that while women are secluded at menstruation, men, in particular, her father, had complete freedom of mobility at this time: “Fathers can go to any place they want for seven days.” She talked about the issue in quite an acerbic manner, indicating that it angered her.

Touch and sight restrictions: people

Indira, from a Magar community, and Aisha, from a Chettri community, faced touch and/or sight restrictions at menstruation. Aisha reported being severely scolded by her sister for touching a male member of the family when she was menstruating. This prohibition does not seem to be practised in Kathmandu where some urban families are restricted to living in a one-room home. For Indira, touch restrictions related to women and men were specifically enforced in her village at first menstruation (i.e. “guniyo cholo”). She described sight restriction as related to looking at specific family members:

“So when you menstruate for the first time, they send you. We are not allowed to see our parents’ face. They keep you in a room. After the periods stop, they bring you new clothes and take you home.”

In other words, the sight restriction was not just limited to looking at men in the immediate proximity of the women, but also men from afar.

Touch restrictions: kitchen, kitchen utensils and food

Touch restrictions not only related to people. Soniya, Indira and Sulob all indicated that women were expected to go to different places to cook during menstruation and/or to use different kitchen utensils while cooking. Although Sulob said that women in her Tamang community were not secluded to other houses at menstruation, kitchen restrictions applied. Her mother instructed her at her first menstruation: “ … many people are sent to another house, but you do not have to go anywhere, you can stay in the house. Just don’t touch anything that’s in the kitchen.” Interestingly, Sulob had previously said that she did not practise any menstruation traditions. Yet, the kitchen restriction appeared to be very significant.

Soniya, from a Brahmin community, said she faced restrictions regarding the use of different kitchen utensils, but only in her father’s home in the village: “There are two houses. If I go to the place where my father stays, then I would have different things (kitchen utensils) for everything, but where I stay there is nothing.” Soniya’s description indicates that she does not practise any traditions in the hostel where she now lives in Kathmandu, which is the result of a concerted effort on behalf of the anti-trafficking organisation involved in her care to stop the practices.

Restrictions also affected the women’s ability to touch fruit and flowers and to go to temples during menstruation, as described in the following conversation between Rosina, Niuresha and Sulob, from Magar, Tamang and Tamang communities, respectively. Notably, while Rosina and Niuresha had previously stated that they practised no menstruation traditions in their communities, they appeared to be knowledgeable about some of the touch restrictions practised at menstruation from elsewhere. Rosina said that she knew about the restriction for women to be excluded from entering temples at menstruation, which we think she observed, while Niuresha illuminated a belief regarding what purportedly occurs when you touch fruit if you are menstruating:

Rosina: We were not restricted to do or go anywhere. (Indicating to Sabrina about the practice of restricting women to go to kitchen or to temples)

Niuresha (to Sabrina, the study’s research assistant cum interpreter): We are also not restricted. What about you didi?

Sabrina: There is no restriction.

Niuresha: Same here.

Sulob: I’m not allowed to go to the kitchen.

Niuresha: I’m not allowed to touch fruits.

Rosina (to Niuresha): You are not allowed to touch fruits?

Niuresha: The fruits decay. You shouldn’t touch.

Soniya, who (as mentioned previously) ran away during seclusion at menstruation in her Brahmin community, then debunked one of the myths on touch restrictions for fruit: “The fruits decay, but then I touched it once and nothing happened.” Evidently, Soniya was challenging some of the harsh restrictions and practices.

In opposition to this, Niuresha also told us she had a personal belief around touch restrictions: “If our hearts are pure, we can touch anything.” While this statement indicates that she does not believe in touch restrictions, it is interesting to note that she said earlier you should not touch fruit. This suggests that she may not be fully aware of the issue of touching some food being a stigmatising issue for women at menstruation.

“Tikka”

The notion that women cannot partake in religious rituals while menstruating was raised by Rosina, from a Magar community, by the mention of being restricted from entering temples. In a conversation between Niuresha, Rosina and Soniya on the touch restrictions at menstruation, Rosina referred to a very specific religious ritual: “You are not allowed to wear tikka.” In other words, women are not allowed to receive tikka – blessings on their forehead – during holy rituals and are equally likely to be prohibited from participating in holy rituals at menstruation. In dialogue with one another, Niuresha, Rosina, Soniya and Sulob also spoke about different practices of menstruation traditions and tikka rituals in other village communities. Niuresha noted:

“One of my friends was a Magar, she had a ritual where she was given “guniyo chulo” and they were given tikka without showing their face to the brothers.”

Stigma for having a daughter

One of the trafficked women in our study had given birth to a daughter and had experienced stigmatisation over it from her husband and her mother-in-law. Aisha, from a Chettri community, first spoke about this issue when she looked at a photograph of her clay-modelled uterus in the group interview (, see also discussion). She recalled her experience of miscarrying twin boys in violent circumstances in a dance bar. After the miscarriage, her husband had accused her of “ … having the medicine and throwing the babies.” In other words, he believed she aborted them because they were boys.

At the subsequent birth of her daughter, Laxmi, Aisha experienced pressure from her husband to give birth to a boy, and soon after, from her mother-in-law. Moreover: “On the sixth day for a name-taking ritual, my mother-in-law came and pressed Laxmi’s throat just because she was a girl child.” Notably, the physical threat from Aisha’s mother-in-law (i.e. a female figurehead) for bearing female offspring made a strong impression. Aisha said she was afraid of giving birth to another girl in the future because of such issues. This fear also appeared to be related to an event she learnt about where a female family member was murdered in her husband’s village in Far Western Nepal because she gave birth to two female offspring:

“In the eastern part in Mahendranagar Dhangadi people wish for a boy more than a girl. My sister-in-law, my husband’s brother’s wife was killed (burned with kerosene) because she had two daughters … that’s the reason I don’t go to the village … Whenever, he would ask me to go to the village, I find an excuse.”

It is important to note that Aisha is illiterate, so we believe that radio and television is an important source of knowledge for her. Aisha further believes that the issue of valuing sons was prevalent in the village (Mahendranagar Dhangadi) but not in Kathmandu: “There’s some kind of fate there.”

Aisha said she tried to tell her husband about her inability to determine the sex of a child (as had been explained to her, but we do not know by whom), but that he was not convinced. She then obtained contraception without his knowledge and helped her friends who were experiencing son-preference issues to do the same. They did so under the guise of going to medical clinics for general check-ups. Aisha said she would not care if her husband found out: “I don’t care. I don’t care. He would get angry and then talk to me after a few seconds.” In other words, she knew his anger would simmer, but she felt it was her right to decide. Her reasons for the decision also related to economic instability and, closely related, birth spacing.

Stigma related to pre-marital sex

The stigma for having pre-marital sex emerged when discussing aspects of the male reproductive body. Niuresha, reflecting on what could happen to a vagina in a situation of forced sex (rape), asked Sabrina (the study’s research assistant cum interpreter): “So if you have sex for the first time, is it really painful?” Sabrina replied: “I also don’t know the answer to it.”

This issue then ignited a conversation in the group of the young unmarried trafficked women on the breaking of virginity. Sulob related fear of being stigmatised for losing virginity and, subsequently, who instils that stigma:

“So, there is a stigma that when you have sex for the first time after marriage and you don’t bleed. The boy would ask you whether you have done it before … if you don’t bleed, they actually ask you if you have had sex before.”

Stigma related to pregnancy before marriage

A stigma related to becoming pregnant before marriage emerged in a discussion on why unmarried women “throw” (abandon) or abort babies. Rosina thought that they did this “ … because of the fear of society and their parents.” In other words, women carry a fear of being stigmatised. This comment was interesting because it was made by the youngest of our study participants, suggesting that this stigma is widely felt – and perhaps discussed – among women. In this discussion, Soniya spoke about a young woman she knew who fell pregnant to a boy she had fallen in love with. Niuresha related a story about how her aunt had raised the daughter of a mentally ill girl who became pregnant after being raped by a group of boys. In both scenarios, the boys had abandoned or taken no responsibility for the pregnant girls or their babies. Soniya also described how she and a friend had rescued an abandoned male baby in the jungle. Rosina added that female and male babies are sometimes abandoned or aborted, even by couples, for reasons other than stigma: out of economic necessity. The discussion made clear, however, that women are stigmatised for being pregnant outside of marriage.

Discussion

In Nepal, young women who have been trafficked into the sex industry experience particular cultural stigmas, which can have a lifelong impact and make their reproductive lives particularly difficult.

In relation to the methodology used, we were cognisant of the varied outcomes of the clay workshops. Sometimes the women made clay sculptures that they did not necessarily discuss (possibly because the process was too emotional), and sometimes they made clay work that facilitated dynamic discussion, but the clay work itself did not reflect any aspects of the issues discussed. For example, in the menstruation workshop, the women only created clay sculptures of themselves experiencing pain at menstruation or such things as pimples that appeared on their faces in their individual body sculptures. Yet, the discussion ignited issues of menstrual stigma (particularly after the women told us at what age they first menstruated) but the women did not represent any aspect of the menstrual stigma issues, such as being secluded to another house, in clay. The clay sculptures themselves were quite simple, so the content was generally self-evident.

However, when many of the clay works were reflected upon in photographic form, they raised significant emotional issues for the women. One such example is the photographs of the clay images the women made of male reproductive body parts which raised negative experiences of men in Nepalese culture and society. These photographs also enabled the women to discuss these issues in ways in which they might otherwise have been unable to. An example is the photograph of a uterus made in clay by one of the women (), which triggered a traumatic memory of reproductive loss, recalling the miscarriage of twin boys in a dance bar after taking a violent knock to her abdomen in a scuffle. We believe this memory was ignited when she looked at her “anatomically incorrect” representation of a uterus and realised that if it was open in the way she had depicted, a baby would fall out during pregnancy. Reflections over some of the clay sculptures in the photographic form of other women and girls in Nepalese culture and society (i.e. mothers/grandmothers) also triggered memories of their own mothers who they were separated from because of trafficking. This was the most emotional issue to arise over the series of seven participatory workshops and group interview and the researcher and research assistant cum interpreter made a joint decision in the group interview not to probe into this issue because it was too sensitive (as indicated through the tones of voice and body language) for the young women involved.

Menstrual stigma

Little research has been conducted on attitudes to menstruation In South Asia “ … despite religiously-based menstrual restrictions imposed on women” (p.1).Citation17 Menstruation pollution beliefs are widespread in Nepal, particularly in Hindu communitiesCitation3,Citation17,Citation18 and vary among different religions, class, social status and castes. Traditionally women are viewed as polluting during menstruation and childbirth regardless of their caste.Citation15 The stigma for untouchability at menstruation can be traced back to the MA of 1854.Citation2 Taboos surrounding menstruation are particularly prevalent in rural regions.Citation19,Citation20,Citation21 While in some Buddhist communities menstruation is considered to be a natural and normal physiological process,Citation22,Citation23 it is not commonly so in Nepal “because of the influence Hinduism has had on Buddhism” (p.524).Citation24 The trafficked women in this study were subjected to restrictive practices, with the Brahmin Hindu practice of chaupadi appearing to be the harshest, though gupha and guniyo cholo seem to have comparable elements.

According to Robinson,Citation25 chaupadi is taken from two Hindu words, chau meaning “menstruation” and padi meaning “women”. During chaupadi women usually go to a goth (house) (p.193).Citation25 In some Hindu communities, menarche is marked with the custom of gupha basne (which literally means “staying in a cave”) and a girl must stay in a darkened room for up to 12 days.Citation17,Citation26 Religious rules forbid a menstruating woman from sharing a bed with her husband, entering a temple or kitchen, preparing food or touching a male relative.Citation15 It has also been reported that women cannot participate in religious activities such as worship and the lighting of holy lamps,Citation27 or go to temples or do household chores.Citation21 In some communities, women must refrain from looking at their reflections at menstruation or using public water supplies.Citation28 These traditions are implemented from menarche and for all menstrual periods until menopause.Citation29 To date, guniyo cholo has not been mentioned in academic literature, but it appears to be drawn from the Hindu concept of three gunas, which roughly translates to the qualities that determine a personCitation29 and appears to be related to “coming of age”. In Nepal, it is usually marked with a ceremony for girls with gifts of new clothes and a religious tikka ceremony. In our study, it appeared to have a relationship with menarche and chaupadi and gupha traditions and practices, such as being secluded in a dark house during the first period.

This study also revealed that some Brahmin women cannot even look in the direction of the father’s home. KondosCitation29 also mentions this in relation to ParbatiyaFootnote† communities, noting that menstruating women should not look at the rooftop of a family home and that a kinship system is involved in who can be “polluted” by menstruating women. The unmarried trafficked women in our study said that all menstruation traditions are practised in the villages, but they did not practise them in their hostel in Kathmandu. This suggests that the active education effort there is having an effect.

In contrast, the married trafficked women (who do not live at the hostel) said they would continue the practices if circumstances permitted: they lived in one-room homes and so do not have another home to be secluded to and because, as one of them said: “It’s our culture, we have to practise it.” This was especially felt by the married trafficked woman who had a daughter. Moreover, the discussions suggested that picking up the practices on return to their villages appears to be without choice.

In a study on adolescent girls from a variety of different areas across Nepal, Archarya et al.Citation27 note that menstruation practices vary between districts, but many girls they interviewed felt compelled to practise the traditions because it was part of their culture and moreover “ … disobedience to the mothers/elders is a sin” (p.118).Citation27 Indeed, menstruation practices are deeply ingrained in the culture.Citation17,Citation25 The practice of chaupadi was supposedly outlawed in Nepal in 2005, but government regulations were not implemented in remote western regions and have continued in some regions, such as the Accham district.Citation25

It is clear from our study that harsh menstruation traditions and practices, particularly seclusion, do not merely occur in the Far Western region of Nepal, but also in some Brahmin-Chettri or Magar communities in Mid-Western Nepal (such as some parts of the Myagdi district) and Central regions (particularly in the Lalitpur and Sankhu districts near Kathmandu).

The enforcers of the traditions are generally women.Citation17,Citation19,Citation25 Our study concurs with the view that mothers and sisters are strict “enforcers of menstrual rituals” (17, p.8). In addition, we found that men, at least in some communities in Nepal, are actively involved in the implementation of menstruation traditions. This is also reported by Crawford, Menger and KaufmanCitation17 who note women commenting on the strictness of their husbands, fathers and sons in enforcing the traditions. Our study revealed that men have complete freedom of social mobility while women are secluded at menstruation. To date, no study in Nepal has also reported on any significant resistance to the traditions. Yet, as was shown, one of the Brahmin women who faced the harshest menstruation traditions actively challenged the Hindu practices and related myths. Another, a Tamang woman, held a personal belief of being “pure” at menstruation, and so women could touch anything while menstruating. It may be that this comes from a Buddhist belief system although touch restrictions related to food appear to be of Hindu origin. Furthermore, she comes from a part of the Nuwachot district where menstruation traditions and practices may be more loosely enforced. In any case, she may not have internalised the stigmatising traditions as the other women have because her early experiences were different.

Nevertheless, it is unknown whether those who challenged the traditional views would feel compelled to practise the menstruation traditions if they moved back to their village districts, especially to those Brahmin-Chettri or Magar communities where the traditions seemed to be deeply entrenched.

In relation to untouchability outside menstruation, one of the women in our study referred to her birthing water as being “dirty” when she delivered her daughter. We were not sure if she meant dirty by means of colour or untouchability, but note that the issue of secretions associated with childbirth being untouchable is reported by Sharma et al.Citation30 and that secretions associated with menstruation and childbirth are viewed as “polluting” according to purity and impurity rituals in the MA of 1854.Citation2

Stigma related to pre-marital sex

In Nepal, discussion of women’s and adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health, and literature on sexual practices, is limited due to cultural taboos on engaging in societal discourse on such matters,Citation17 including pre-marital sex. The “Six Rules of Forbidden Sexual Intercourse” of the MA of 1854 prohibit pre-marital sex for women.Citation2 In contrast, Eller and MahatCitation31 have reported that “attitudes toward pre-marital sex and extramarital sex for men are permissive” (p.55). In addition, having sex with a commercial sex worker, according to Hannum (cited in Eller & Mahat (p.55)Citation31 “ … is not considered to affect a single man’s virginity, and the belief that sex with a sex worker is not really sex also permits adultery with CSWs (Commercial Sex Workers)”. This has also been poignantly depicted in a study of sexual and reproductive health of young people in Nepal in which young women reported on the incidence of pre-marital sex: “boys sleep with many girls but boys remain prestigious, but girls become (regarded as) prostitutes” (p.63)Citation32. A women’s marriageability is reduced because she is seen to be “impure” or, bigriyo [ruined] (p.266),Citation5 according to purity and impurity rituals of the MA of 1854.Citation2 Thus, as a consequence, her ijjat (family honour and prestige) is lost (p.270).Citation5

There does not appear to be academic literature on who instils the stigma on pre-marital sex in Nepal. In this study, one of the young unmarried trafficked woman of Tamang origin revealed that it is the husband who will expect his wife to bleed at their first sexual encounter after marriage and it is he who instils the stigma. As a cultural backdrop, note that Rule 5 of the MA of 1854s “Six Rules of Forbidden Sexual Intercourse” forbids women the right to have sex, and hence to seek sex.Citation2 In Hinduism, women’s sexuality is said to endanger and affect men’s sexuality.Citation4 However, the rules do not provide any prohibitions for men.Citation2

Stigma related to pregnancy before marriage

In Nepal, the stigma associated with pregnancy before marriage is largely undocumented. However, one of the unmarried trafficked women of Magar origin suggested that the stigma is societal. This is consistent with the findings of a study undertaken in a rural Magar community in Nepal by AhearnCitation33 which concluded that the social stigma attached to pregnancy before marriage was instilled by villagers.Citation33 The young age at which our Magar participant knew about this stigma (14 years) suggests it must be widely known by women and girls. In our study, the trafficked women also said that men/boys take no responsibility for pre-marital sex which results in pregnancy, leaving women largely to suffer the societal consequences. However, AhearnCitation33 has reported that pregnancy before marriage does not always result in shame – it largely depends on neighbours and families – and sometimes men do take responsibility. One of the Tamang women in our study also mentioned that her aunt had cared for a girl who had been gang-raped and that the girl and child grew up in a supported environment. This suggests that some Tamang communities are accepting of women who become pregnant before marriage, but it appears to be the women of those communities, rather than the men, who provide support for unmarried mothers.

Stigma related to having a daughter

Despite the rates of fertility declining in Nepal, son-preference is still pervasive in the patrilineal and patrilocal society.Citation34 In Hinduism, sons are expected to look after their parents as they age, and they are the only ones who can perform funeral ritesCitation4,Citation35 making it a practical necessity and a religious duty to have a son.Citation4 This issue contributes to female infanticide, sex selection via ultrasound, and illegal and forced abortion of girls, though these practices are reported to be declining in Nepal.Citation36 Yet, if women do not give birth to a son to fulfil such expectations,Citation4 they will continue to have children until they do.Citation37

In our study, one of the married trafficked women was stigmatised for having a female child – as was her daughter. She said that “son-preference” (as it is culturally articulated) is a strongly held value of her husband, his broader family and their village community of Mahendranagar Dhangadi. The instance of wife-burning for having two daughters in this village demonstrates that valuing boys above girls is strongly entrenched in this district. Notably, the reason underlying the burning of this woman to death was a perceived right to attain property after marriage. In Nepal, despite the increasing role of women in agriculture, not many own land.Citation38 However, some women do gain rights to land through kinship or marriage relationships with men.Citation39 AllendorfCitation38 notes that, “In Nepal, the main means of gaining land is through inheritance, which is largely patrilineal” (p.1976).Citation38 As Nepal is primarily an agrarian society, the land is an important source of economic livelihood and hence of power and status.Citation38 So it is that the women of Mahendranagar Dhangadi are stigmatised for having female children and are considered dispensable if they threaten the status of men through land attainment. Interestingly, it appears that Mahendranagar Dhangadi is also a village that, in relation to “son-preference”, condones violence against women perpetrated by both men and women.

There is little academic literature about the role women in Nepal play in “son-preference” or instilling stigmas against other women for having female offspring. Our study revealed an issue of women’s violence against women (i.e. Aisha’s mother-in-law pressing Aisha’s daughter’s throat at her naming ceremony), which we learned from our fieldwork is a sensitive issue and is not openly spoken about. Indeed, using the word “violence” to name women’s violence against women of itself appeared to be extremely sensitive.

Strengths and limitations

Our study was the first of its kind in Nepal. The trafficked women engaged in a series of seven themed participatory workshops using clay/three-dimensional body mapping and a group interview using photography. Due to the small sample size, the findings are not generalisable. As the methodological process was also new, it is not known whether women would have revealed more if the process had been undertaken individually. However, the group process was designed with the collective culture and the vulnerable group of study participants in mind. In this study, this approach appeared to be successful as we observed significant group cohesion and positive engagement from the women. For reasons related to time, resource and accessibility issues, the trafficked women were grouped for data collection into those who had no children and those who had been pregnant and had children. This proved beneficial as women in each group were of a similar age (though with different trafficking histories) and had similar reproductive life stage experiences.

Undertaken over eight weeks, the workshops enabled the women to get to know one another and feel comfortable to share experiences. Importantly, the workshops were not framed through a western biomedical lens, but rather enabled the women to illuminate their own experiential understandings of their bodies. The multisensoriality of the methods enhanced this process and the participatory nature of the workshops enabled us to acknowledge power differentials. However, we recommend that research should be conducted in relation to the implementation of this method in other reproductive health contexts, especially with vulnerable populations. Although the method was efficient for producing rich data quickly, the process was also dangerous: it often elicited unexpected emotions and may not be suitable for use with some groups of people. We recommended that facilitators be trained in the use of the method to understand the properties of clay, the potential for emotional release through clay, the pace of the clay process and how the process of working with clay works over an extended time frame. We also identified the need for a facilitator to have strategies to manage individual/group emotion with clay in the research milieu. The researcher has a professional background in creative arts therapy and experience with using clay/photography in a reproductive health context with women in Australia and trafficked women in Nepal. The research assistant cum interpreter was also trained in the methods. It is also important to understand the dimension that photography adds to the CERM because the CERM as a whole makes up more than the individual parts.

Recommendations

There have been attempts to address the various stigma on trafficked women in NepalCitation40, but changing attitudes is a slow process.Citation7 The change processes themselves have sometimes led to further stigmatisation. Past government initiatives to stop the practice of menstruation traditions, in particular, the practice of chaupadi, have not been effective (notably the 2005 failure to implement regulations in remote western regions.)Citation25 Laws were introduced in 2018 prohibiting the seclusion of women at menstruation, breaches of which attract up to a three-month jail term or a considerable fine of 3,000 rupees ($US30).Citation41 Yet it is evident that much work still needs to be done given the 2019 death of a mother and child in a chaupadi hut in the Bajura districtCitation42 and another woman suffocating in another such windowless hut (after she lit a fire to keep warm) in the Doti district.Citation43

We recommend that a public health campaign be developed to address menstrual stigma, stigma related to pre-marital sex, stigma related to pregnancy before marriage and stigma related to having female children, because of the potential of these stigma to impact on the “whole of life” and have an intergenerational effect on women. The message delivered should highlight the physical, emotional, cultural, social and other long-term harms that can result. While the target of such campaigns should largely be men, we also recommend that women need to be included in the conversations as they are actively involved in the implementation of menstruation traditions, for example, through action and language. In Nepal, while much relevant activism is taking place at present,Citation44 more needs to be done to protect the most marginalised and stigmatised groups of women, such as young women who have been trafficked into the sex industry, as they are highly vulnerable to further harm.

Conclusion

In Nepal, women who have been trafficked in the sex industry are severely stigmatised as a result of their trafficking experiences. Already one of the most marginalised populations of women in Nepal, they are further subject to reproductive health stigmas. The stigmas can be traced back to Hinduism, its patriarchal norms and the caste system as is practised in Nepal. Despite political changes since the end of the Rana Rule (1951), the stigmas persist and affect trafficked women, their families, their villages and the generation of women that follow. As Link and PhelanCitation10 hypothesised, “ … stigmatization probably has a dramatic bearing on the distribution of life chances in areas such as earnings, housing, criminal involvement, health and life itself” (p.363).Citation10

Authorship

TO and DM conceived and designed the study and were involved in analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the article for important intellectual content and approving the final publication version. SC played a key role in the refining the conceptualisation and design of the study, particularly related to cultural concerns and also assisted in ensuring that the data were analysed and interpreted with cultural considerations in mind. She also played an important role in the revision of the article from its first draft for intellectual and cultural context. She also approved the final version for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank Asha Nepal and CAP Nepal for their support in enabling us to complete this study in Nepal. We also thank, Nirmala Prajapati, Saru Shilpakar and Kamal Kafle for their Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health expertise as their cultural knowledge was seminal to the outcomes of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

* Höfer’sCitation2 analysis is only one of several interpretations of the MA of 1854/caste system in Nepal.

† Brahmins from hill districts.

References

- Pradhan R. Ethnicity, caste and a pluralist society. In: Visweswaran K, editor. Perspectives on modern South Asia: a reader in culture, history, and representation. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. p. 100–111.

- Höfer A. The caste hierarchy and the state in Nepal: a study of the Muluki Ain of 1854. Kathmandu: Himal Books; 2004.

- Bennett L. Dangerous wives and sacred sisters: social and symbolic roles of high-caste women in Nepal. 2nd ed. Kathmandu: Mandala Publications; 2002.

- Crawford M. International sex trafficking. Women Ther. 2017;40(1–2):101–122. doi: 10.1080/02703149.2016.1206784

- Pike L. Sex work and socialisation in a moral world: conflict and change in bādī communities in Western Nepal. In: Manderson L, Liamputtong P, editor. Coming of age in South and South East Asia: youth, courtship and sexuality. Richmond: Curzon Press; 2002. p. 228–248.

- Dhungel R. “You are a besya”: microagressions experienced by trafficking survivors exploited in the sex trade. J Ethnic Cult Divers Soc Work. 2017;22(1–2):126–138. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2016.1272519

- Frederick J, Basynet M, Aguettant L. Trafficking and exploitation in the entertainment and sex industries in Nepal: a handbook for decision-makers. Kathmandu: Terres des hommes; 2010. Available from: https://www.tdh.ch/sites/default/files/study_trafficking_tdhl_2010.pdf.

- Blanchet T. Lost innocence, stolen childhoods. Dhaka: University Press Limited; 1996.

- Fikree F, Pasha O. Role of gender in health disparity: the South Asian context. BMJ [Internet]. 2004;328(7443):823–826. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC383384/. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.823

- Link B, Phelan J. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):363–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

- Hatzenbuehler M, Phelan J, Link B. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Pub Health. 2013;103(5):813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069

- Subedi G. Trafficking in girls and women in Nepal for commercial sexual exploitation: emerging gaps and concerns. Pak J Women’s Stud. 2009;16(1-2):121–146.

- National Human Rights Commission. (2016). Trafficking in persons: national report 2013-2015, NHRC [Internet]. 2016. Available from: <http://www.nhrcnepal.org/nhrc_new/doc/newsletter/TIP_National_Report_2015_2016.pdf>.

- Ghimire L, van Teijlingen E. Barriers to utilisation of sexual health services by female sex workers in Nepal. Glob J Health Sci. 2009;1(1):12–22. Available from: <http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/9833/1/Laxmi_Ghimire_%26_EvT_2009_Global_J_Health_Sci.pdf>. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v1n1p12

- Ghimire L, van Teijlingen E, Cairns W, et al. Utilisation of sexual health services by female sex workers in Nepal. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:79–86. Available from: <https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6963-11-79>.

- Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E. Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2012.

- Crawford M, Menger L, Kaufman M. This is a natural process: managing menstrual stigma in Nepal. Cult Health Sex. 2014;16(4):426–439. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.887147

- Cameron M. On the edge of the auspicious: gender and caste in Nepal. Kathmandu: Mandala; 1998.

- Standing K, Parker S. Girl’s and women’s rights to menstrual health in Nepal. In: Mahtab, N, Barsha I, Islam M, Binte Wahid I, editors. Handbook of research on women’s issues and rights in the developing world. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, Information Science Reference, 2017, p. 156–168.

- Adhikari P, Kadel B, Dhungel S, et al. Knowledge and practice regarding menstrual hygiene in rural adolescent girls of Nepal. Kathmandu Med Coll J. 2007;5(3) iss. 19:382–386.

- Sapkota D, Sharma D, Pokharel H,V, et al. Knowledge and practices regarding menstruation among school going adolescents of rural Nepal. J Kathmandu Med Coll. 2013;2(3)(5):122–128.

- Jnanavira D. A mirror for women? Reflections of the feminine in Japanese Buddhism. J West Buddh Rev. [Internet]. 2006;4:1–11. Available from: <http://www.westernbuddhistreview.com/vol4/mirror_for_women.html>.

- Ranabhat C, Kim C, Choi E, et al. Chhaupadi culture and reproductive health of women in Nepal. Asia Pac J Publ Health. 2015;27(7):785–795. doi: 10.1177/1010539515602743

- Bhartiya A. Menstruation, religion and society. Int J Soc Sci Human. 2013;3(6):523–527. doi: 10.7763/IJSSH.2013.V3.296

- Robinson H. Chaupadi: the affliction of menses in Nepal. Int J Women’s Dermatol. 2015;1(4):193–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.10.002

- Bennett L. The wives of the rishis: an analysis of the Tij Rishi Panchami woman’s festival. University of Cambridge [Internet], 1976. Available from: <https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/227264/kailash_04_02_04.pdf?sequence=2>.

- Acharya I, Shakya M, Sthapit S. Menstrual knowledge and forbidden activities among the Rural Adolescent Girls. Educ Dev. (Special Issue) [Internet], 2011, p. 107–125.

- Mahon T, Fernandes M. Menstrual hygiene in South Asia: a neglected issue for WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) programmes. Gend Dev. 2010;18(1):99–113. doi: 10.1080/13552071003600083

- Kondos V. On the ethos of Hindu women: issues, taboos and forms of expression. Kathmandu: Mandala; 2004.

- Sharma S, van Teijlingen E, Hundley V, et al. Dirty and 40 days in the wilderness: eliciting childbirth and postnatal cultural practices and beliefs in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(4):147–158. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0938-4

- Eller L, Mahat G. Psychological factors in Nepali former commercial sex workers with HIV. J Nurs Scholar. 2003;35(1):53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00053.x

- Regmi P, Simkhada P, van Teijlingen E. Boys remain prestigious, girls become prostitutes’: socio-cultural context of relationships and sex among young people in Nepal. Glob J Health Sci. 2010;2(1):60–72. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v2n1p60

- Ahern L. Invitations to love: literacy, love letters and social change in Nepal. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2001.

- Brunson J. Son preference in the context of fertility decline: limits to new constructions of gender and kinship in Nepal. Stud Fam Plan. 2010;41(2):89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00229.x

- Yue K, O’Donnell C, Sparks P. The effect of spousal communication on contraceptive use in Central Terai, Nepal. Patient Ed Couns. 2010;81(3):402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.018

- Solotaroff J, Pande R. Violence against women and girls: lessons from South Asia. World Bank Group, 2014, Available from: <https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/20153/9781464801716.pdf>.

- Paudel S. Women’s concerns within Nepal’s patriarchal justice system. Ethics Action. 2011;5(6). Available from: <http://www.ethicsinaction.asia/archive/2011-ethics-in-action/vol.-5-no.-6-december-2011/womens-concerns-within-nepal2019s-patriarchal/>.

- Allendorf K. Do women’s land rights promote empowerment and child health in Nepal? World Dev. 2007;35(11):1975–1988. Available from: <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3657746/>. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.12.005

- Pandey S. Rising property ownership among women in Kathmandu, Nepal: an exploration of causes and consequences. Int J Soc Welf. 2010;19(3):281–292. Available from: < https://library.pcw.gov.ph/sites/default/files/rising%20property%20ownership%20among%20women.pdf>. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2009.00663.x

- Frederick J. The status of care, support, social reintegration of trafficked persons in Nepal, as of December 2005. Tulane J Int Compliance Law. 2005;14:316–330. Available from: <https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/tulicl14&div=18&id=&page=&t=1557209453>.

- Lamsal P. In Nepal, women are still banished to ‘menstrual huts’ during their periods. It’s time to end this dangerous tradition. Independent [Internet]. 2017 May 24 [cited 2019 Feb 5]. Available from: <http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/world-menstrual-hygiene-day-first-hand-account-nepal-menstrual-huts-death-confinement-a7752951.html>.

- BBC News. Nepal woman and children die in banned ‘menstruation hut’. BBC News [Internet], 2019 10 January [cited 2019 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-46823289.

- BBC News. Nepal woman suffocates in banned ‘menstruation hut’. BBC News [Internet]. 2019 4 February [cited 2019 Feb 5]. Available from: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-47112769>.

- Parker S, Standing K. Nepal’s menstrual huts: what can be done about this practice of confining women to cow sheds? The Conversation [Internet], 2019 Jan 23 [cited 2019 Feb 5]. Available from: <https://theconversation.com/nepals-menstrual-huts-what-can-be-done-about-this-practice-of-confining-women-to-cow-sheds-109904#comment_1834733>.