Abstract

The Indian national health policy encourages partnerships with private providers as a means to achieve universal health coverage. One of these was the Chiranjeevi Yojana (CY), a partnership since 2006 with private obstetricians to increase access to institutional births in the state of Gujarat. More than a million births have occurred under this programme. We studied women’s perceptions of quality of care in the private CY facilities, conducting 30 narrative interviews between June 2012 and April 2013 with mothers who had birthed in 10 CY facilities within the last month. The commonly agreed upon characteristics of a “good (sari) delivery” were: giving birth vaginally, to a male child, with the shortest period of pain, and preferably free of charge. But all this mattered only after the primary outcome of being “saved” was satisfied. Women ensured this by choosing a competent provider, a “good doctor”. They wanted a quick delivery by manipulating “heat” (intensifying contractions) through oxytocics. There were instances of inadequate clinical care for serious morbidities although the few women who experienced poor quality of care still expressed satisfaction with their overall care. Mothers’ experiences during birth are more accurate indicators of the quality of care received by them, than the satisfaction they report at discharge. Improving health literacy of communities regarding the common causes of severe maternal morbidity and mortality must be addressed urgently. It is essential that cashless CY services be ensured to achieve the goal of 100% institutional births.

Résumé

La politique nationale de santé indienne encourage les partenariats avec des prestataires privés comme moyen de parvenir à une couverture santé universelle. L’un d’eux était le Chiranjeevi Yojana (CY), un partenariat instauré depuis 2006 avec des obstétriciens privés pour élargir l’accès aux accouchements dans des structures médicales de l’État du Gujarat. Plus d’un million de naissances ont été encadrées par ce programme. Nous avons étudié comment les femmes jugeaient la qualité des soins prodigués dans les établissements privés du CY et mené 30 entretiens narratifs entre juin 2012 et avril 2013 avec des mères qui avaient accouché dans dix centres du CY au cours du mois précédent. Les caractéristiques généralement acceptées d’un « bon (sari) accouchement » étaient : de donner naissance par voie vaginale, à un garçon, avec des douleurs aussi courtes que possible, et de préférence gratuitement. Mais tout cela comptait uniquement après que le premier résultat d’être « sauvée » était obtenu. Les femmes s’en assuraient en choisissant un prestataire compétent, un « bon docteur ». Elles voulaient un accouchement rapide en manipulant la « chaleur » (la force des contractions) avec des ocytociques. Des cas de soins cliniques inadaptés pour de graves morbidités ont été signalés même si les quelques femmes qui ont reçu des soins de qualité médiocre ont quand même exprimé leur satisfaction pour l’ensemble des soins. L’expérience des mères pendant l’accouchement est un indicateur plus précis de la qualité des soins qu’elles ont reçus que la satisfaction dont elles font état lorsqu’elles quittent la maternité. Il faut améliorer de toute urgence les connaissances sanitaires élémentaires des communautés concernant les causes fréquentes de morbidité et mortalité maternelles graves. Il est essentiel d’assurer des services sans paiement initial des patientes pour parvenir à l’objectif de 100% de naissances en milieu médical.

Resumen

La política sanitaria nacional de India fomenta alianzas con prestadores de servicios privados como un medio para lograr cobertura universal de salud. Una de éstas fue la Chiranjeevi Yojana (CY), alianza establecida en el 2006 con obstetras particulares para ampliar el acceso al parto institucional en el estado de Gujarat. Más de un millón de nacimientos han ocurrido bajo este programa. Estudiamos las percepciones de las mujeres de la calidad de la atención en los establecimientos de salud privados de CY por medio de 30 entrevistas narrativas realizadas entre junio de 2012 y abril de 2013 con madres que habían dado a luz en 10 establecimientos de salud de CY en el último mes. Las características comúnmente acordadas de un “buen (sari) parto” eran: dar a luz vaginalmente a un hijo varón, con el período de dolor más corto y, de preferencia, gratuitamente. Pero todo esto tenía importancia solo después de satisfacer el resultado principal de ser “salvada”. Las mujeres aseguraban esto eligiendo a un/a prestador/a de servicios competente, un/a “buen/a doctor/a”. Ellas querían un parto rápido manipulando el “calor” (es decir, las contracciones) con oxitocina. Hubo casos en que las mujeres recibieron atención clínica inadecuada por morbilidades graves, aunque las pocas mujeres que recibieron atención de mala calidad expresaron satisfacción con la atención general recibida. Las experiencias de las madres durante el parto son indicadores más precisos de la calidad de la atención que recibieron, que la satisfacción que informaron al ser dadas de alta. Es imperativo abordar con urgencia el mejoramiento de los conocimientos de las comunidades sobre salud, en particular sobre las causas comunes de morbimortalidad materna grave. Para lograr el objetivo de 100% de partos institucionales, es esencial eliminar los pagos adelantados en efectivo por los servicios.

Introduction

Most maternal deaths cannot be foreseen because maternal complications can arise at any time. The WHO estimates that 295,000 maternal deaths occurred across the globe in 2017; approximately 12% of these deaths occurred in India.Citation1 Maternal mortality and morbidity can be prevented by assured availability of skilled personnel in an enabled environment. In lower-middle income countries (LMICs) such ready availability can be best assured to all birthing mothers in institutions.Citation2 Therefore, ensuring very high levels of institutional births has been recommended as a strategy to reduce maternal mortality.Citation3 This would require universal coverage for institutional births for all women. To achieve this, during the last decade, the Indian government invested in numerous programs to actively promote institutional births and thereby reduce maternal mortality. This has led to an increase of institutional births from 43% in 2004 to 83% in 2014.Citation4

India has a very large private health sector.Citation5 In 2012–2013, while the Government of India required 5,187 obstetricians for its Community Health Centres, only 1,959 (38%) were in position.Citation6 In the same year, the Federation of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of India had a membership of 27,000 obstetricians; at least 23,000 (85%) were in the private sector.Citation7 The weak oversight of the private health sector by both regulatory agencies and professional associations in India is known.Citation8 However, due to the lack of capacity and quality in the public health sector, state governments have been encouraged during the last decade to explore public-private-partnership models wherever private facilities are availableCitation9 to facilitate universal health coverage. Numerous state governments have partnered with these private providers in order to rapidly increase the access of poorer populations to institutional births.Citation10 One such public-private-partnership (PPP) was begun in 2006 in the state of Gujarat in western India, called Chiranjeevi Yojana (CY). Under this scheme, mothers from the most vulnerable households, defined as those belonging to Below-Poverty-Line (BPL) or Scheduled Tribe (ST) households, were declared eligible for free services in partnering private facilities.Citation11 The National Sample Survey conducted in 2014 showed that institutional births in private facilities constituted 59% of all births in rural Gujarat, nearly double the national average of 30%.Citation12 One possible reason proposed was the easier access to private facilities enabled by the CY programme.Citation13 At the height of the CY programme, 865 providers participated in it and more than a million mothers have birthed under this programme.Citation11

The ambitious Ayushman Bharat programme was instituted by the Government of India in May 2018, with the aim of achieving universal health coverage.Citation14 This programme envisages the provision of secondary and tertiary care services for the poorest 40% of the country’s population through partnerships with private providers. It proposes to increase financial access to quality care through an insurance-based approach.Citation15 Increasing numbers of public and private facilities are being assessed, certified and accredited in line with standards laid out by national quality control bodies as a pre-condition of the PPP process.Citation16,Citation17 A mechanism for recording patients’ responses, “Mera Aspataal” (My Hospital), has also been created recently.Citation18 Given the importance of partnerships with private providers for achieving universal health coverage in India, it is key that the quality of care provided not only complies with standards of clinical care, and it must also be perceived by mothers to be of high quality. Care must also be respectful, an increasingly important dimension of quality of childbirth care recorded in the global evidence of mistreatment.Citation19

A recent systematic review by Bohren et al.Citation20 has created a typology of seven domains of mistreatment of women during childbirth across the globe. These include the range of reasons for poor maternity care outcomes – from physical and verbal abuse, to poor clinical standards of care, to larger health system constraints.Citation20 Although availability of facilities and awareness of the need for obstetric care are crucial to reduce maternal mortality, these alone do not ensure facility utilisation by women.Citation21 Women’s perceptions of quality of care are known to influence their service utilisation patterns. In one systematic review, provider behaviour, in terms of courtesy and non-abuse, was the most widely reported determinant of satisfaction.Citation22 Women are reluctant to use maternity care when there are high costs and poorly attuned services.Citation23 There is also evidence, mostly from African countries, to indicate that poorer women experience poorer quality of care and that this affects their utilisation of services.Citation24,Citation25

Qualitative approaches are particularly well-suited to researching these issues of mistreatment, especially when the aim is to understand mothers’ subjective perceptions and experiences in their particular social context. Perceptions of quality of care have been explored through qualitative methods in a variety of settings and have resulted in a deeper understanding of the diverse perceptions of quality of care in institutions. These have then been used to inform policies for intra-partum care.Citation19,Citation26

There is some literature reporting Indian mothers' perspectives of intra-natal care, mostly in public facilities.Citation27–30 Common findings in these studies included lack of privacy and infrastructure, disrespect, abuse and mistreatment. One recent mixed-method study that examined women’s experiences of intra-natal care in Uttar Pradesh found that overall prevalence of mistreatment was nearly 100% in both private and public facilities.Citation30 However, there are no in-depth qualitative studies of mothers’ experiences of birthing in private facilities in India, particularly at facilities participating in a partnership with the state to provide obstetric care to poor women. As pointed out earlier, the private sector provides a considerable proportion of urban and rural institutional births in India, and partnerships with these facilities are scheduled to increase. A qualitative approach can provide insights which can be used to inform the evolving policy setting for the country-wide PPPs under the Ayushman Bharat programme.

The objective of this study was to qualitatively explore the perception of quality of care during childbirth among mothers who had recently given birth in CY partnering private facilities.

Methods

Personal accounts of lived experiences are recognised as authoritative expressions of perceptions.Citation31 It is therefore methodologically appropriate to explore mothers’ perceptions through narrative interviews with mothers themselves.

We created the initial Topic Guide based on our literature review of quality of maternity care. The topics planned for the interviews were antenatal care, choice of facility to birth, description of the mother’s experiences from the beginning of labour pain till she left the facility, and her experiences regarding her preparation for obtaining the CY benefit. We conducted two pilot interviews with mothers who had birthed in CY facilities in Surendranagar town. We found that the mothers and families provided a predominantly positive picture of the birth experience. Other than their protestations about expenditure, they did not articulate any emotions regarding negative experiences in the facilities. We revised the Topic Guide to add topics of conceptualisation of an ideal birthing environment, and expectations during birthing from providers and facilities, so that mothers and families would be able to frame their actual experience with regard to these ideals and expectations. We expanded our section on mothers’ and families’ preconceptions regarding quality, mothers’ earlier personal experiences with birthing and complications, self-perception of end-point of treatment and sense of wellness/recuperation from the birth experience. We also improved the prompts for the domains set in our topic guide.

During pilot interviews with mothers, we also observed that they were not directly approachable. Gender and age-related power differentials in rural areas with low literacy, as in our study area, often meant that young women were expected to defer to male or elder family members, as has been encountered in similar settings in Africa.Citation32 We therefore involved the men in questions about overall perceptions of facility care for birthing, and views regarding expenditure. When prompted, they left the room and allowed women to answer more private questions regarding the process of care during birthing; however, the mother would often be surrounded by one or two female relatives, and sometimes neighbours. The interviewers encouraged the female relatives to speak about their perceptions of the care received by their daughter/daughter-in-law. After this, they would be more willing to leave the room and let the mother speak privately to the interviewers of her own perceptions regarding her birth experience. Thus, we recorded detailed descriptions of perceptions from family members as well as the mother in dyad or triad interviews. We were able to speak to all mothers alone for a quarter to half an hour. We took care to elicit the mother’s account of her experiences and were mostly successful in getting to these. Data collected from approximately one male and one female family member for each mother, as well as from the mothers themselves, were analysed for this paper. Whilst lack of sustained private discussion with mothers alone may be seen as a limitation, this approach reflects the social reality of the highly patriarchal context within which women’s experiences are located.

Study sites

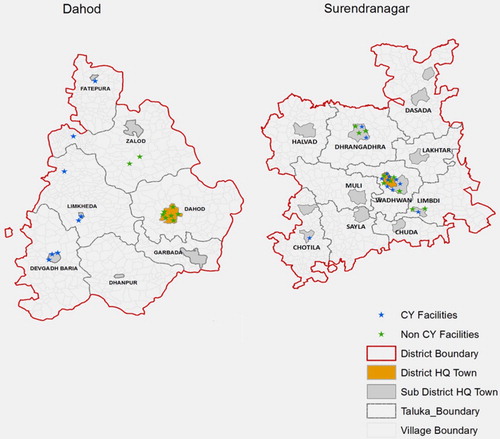

This qualitative study was nested within a larger cross-sectional facility survey conducted in three districts of Gujarat between June 2012 and April 2013 under the MATIND project ().Citation33,Citation34 This included a detailed survey of 118 private facilities which had conducted more than 30 births in the past three months and a survey of all mothers who delivered in each of these facilities during the five consecutive working days of the week. Eighty-five of these facilities were eligible to participate in the CY programme, of which 13 and 19 were located in Dahod and Surendranagar districts. Of these, five and 11 actually participated in the CY programme. Ten facilities participating in the CY programme were selected towards the end of the facility survey for this qualitative study. These were all single-owner maternity homes and had been CY participants for 2–4 years. In Dahod, none of the facilities in the district capital participated in the CY programme. All five facilities from which participating mothers were selected, were located in small sub-district towns. In Surendranagar, two facilities were from the district capital of Wadhwan, and three were from sub-district towns.

Study participants

Women who gave birth in 10 CY participating facilities (five each in Dahod and Surendranagar districts) were asked at the end of their survey whether they would consent to be interviewed at their home regarding their birth experiences within a month’s time. Nearly all women consented. There were 5–15 births at each of these facilities. We selected three mothers from each CY facility, one eligible who received CY benefit (ElgB), one eligible who did not receive CY benefit (ElgNB) and one ineligible (Inelg). We selected mothers purposively, such that we did not choose mothers from the same village, and if possible the same sub-district. Our final sample consisted of 10 mothers from each category, five each from each study district. In total, 30 mothers, 15 from Dahod (Dahod Mother – DM 1 to 15) and 15 from Surendranagar (Surendranagar Mother – SM1 to 15), and their family members were interviewed.

More than three-quarters of our 30 interviewees were above 20 years of age with some education (see ). Four of these mothers had undergone a caesarean section. Twenty of the mothers’ families had borrowed money to meet the expenditure on this birth. Additionally, one ElgB had pawned some gold and one Inelg had sold a goat. There were no discernible differences in these background characteristics between the three groups of mothers. However, the average expenditure on childbirth borne by the three groups showed a distinct gradation, the CY beneficiaries paying the least, and the ineligible (above-poverty-line) families paying the highest charges.

Table 1. Characteristics of interviewees

Data collection

Data collection happened between December 2012 and April 2013. Interviews were planned with the mothers in the third or fourth week after the birth of their babies, at their homes. We contacted the selected mother’s relative by telephone a week earlier, and again on the evening before the interview to confirm our arrival for the interview. We arrived at the homes of the mothers in the morning. We explained to the mothers, elder women and, where applicable, male members of the family that we were conducting a research study to understand women’s and families’ perceptions of health care during the recent birth in the private hospital, with the aim of analysing their experiences and their expectations from providers and facilities, which would help to improve systems in future. The woman and at least two family members/elders/neighbours were present at the beginning of every interview. The women and their family members were mostly illiterate and may have been hesitant to provide written consent for participation because they would not see any immediate benefit or protection in it for themselves; therefore, in order to avoid undermining their trust, verbal consent was obtained from all participants, as per the approved study protocol. Family members, elders and/or neighbours acted as witnesses for each verbal consent obtained. We audio-recorded our explanation and the verbal consent of the mothers, elders and, where applicable, male family members at the beginning of every interview.

The first author (medically qualified) and an assistant conducted interviews in the local language, Gujarati. The assistant conducted the interview while the first author probed and took notes. The semi-structured interviews explored mothers’ and families’ conceptualisation of quality of care, their perceptions about the quality of care received during birth, inter-personal interactions with providers, and the birth environment. Each interview lasted about an hour and half.

In-depth interview guide

The topic guide was designed to let the interviewees describe the chronology of events with regard to their birth experience. As an initial warm-up, mothers and family members were asked for a short description of their birth experience, and then were encouraged to discuss details regarding the family’s travel and expenditure during the recent birth. The mother and female relatives were then guided through the following domains: early perceptions about pregnancy, birthing, labour pain; plan and expectations for this birth; antenatal care and experiences, initiation of labour; travel to hospital; experiences in the hospital; discharge; post-natal period. Finally, mothers were gently probed to reflect on their actual experiences in light of the expectations they had mentioned early in the interview. They were urged to compare their experience with other women in the hospital and with their own past birth experiences. In these final stages of the interview, the mothers were questioned regarding the CY benefit, their expenditure, and their feeling of satisfaction with the care they had received.

Data analysis

Individual interviews were transcribed into Gujarati, and translated into English by a professional transcriber-translator. Ten-minute segments of every recording were randomly selected and reviewed for the fidelity of transcription, and a different segment for translation. Additionally, in 10 recordings, the same segment was reviewed, to cross check both transcription and translation.

The steps of a framework analysis were followed.Citation36 Three members of the research team went through seven of the transcripts and coded them independently. The final list of codes and their categorisation was decided through a consultation between all team members. After agreeing on the coding framework, all transcripts were indexed according to the codes. More codes were added or collapsed during the process using the constant comparison method. Indexing was done using Open Code 4.02 software. Twelve categories were created of which eight were extensively used to develop the themes for this paper: (a) expectations of birthing care; (b) reasons for choice of place of birth; (c) perceptions of quality; (d) experiences of care at hospital in present birth; (e) experiences of the CY programme; (f) antenatal and post-natal care; (g) expenditures on birthing; and (h) complications during birthing. The pieces of text produced by Open Code in each category were read and summarised (with useful quotations) and charted in MS Excel. Further readings and discussion of the data led to the development of themes.

This data analysis and writing was done after analysis and publication of quantitative data that were collected from facilities and mothers during the survey.Citation33,Citation34,Citation37 The analysis and discussion in this study builds on the learnings from these studies.

Ethical approval for procedures followed in this study was obtained from the institutional review board at the Indian Institute of Public Health Gandhinagar (TRC-IEC No. 23/2012). We also received ethical approval from Karolinska Institutet (2010/1671–31/5.I.) and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (2011/3/24-10.8).

Results

Although most mothers struggled to define quality of care a priori, they revealed their preferences and dislikes as they narrated and reflected on their experiences during the birthing process. These fell into five key dimensions of perceptions of quality: concept of a “good delivery”; timely attention; competence and capacity of providers; interpersonal emotional support; physical environment.

Most of the mothers and families had perceived their own care to have been very satisfactory across most of these dimensions. Many compared their experiences with their perceptions of poor quality in the public health system and expressed satisfaction with the care they received.

A good delivery

When asked for their overall evaluation of their recent birth experience, all participants stated that their experience was good because mother and child were “saved”. They used “saved” to indicate that not only were the mother and baby “alive and well”, they had also “survived” the birthing event.

“Our (my) delivery was nice, child is nice, lady is saved; it means everything was complete … [there was] no other problem, that’s how we (mothers) think.” (DM4-Inelg)

“My life was saved. It made my soul happy.” (DM1-ElgNB)

“ … I initially thought that now I might survive or might not survive … now this bleeding has started … (I) felt like that … now treatment is done, so it will be cured, I thought.” (DM3-ElgB)

“[A good delivery] means … we became free (of the pain/suffering) soon.” (SM2-ElgNB)

“ … So we (the family) told sir (the doctor) that even if you give [us] ten thousand rupees, I don’t want [a caesarean].” (DM9-ElgNB)

“Good delivery is when no stitches are taken. Now that it is done … then what can I say? I have to say it is done well. The doctor saved me so I feel well. I have no objection about stitches.” (DM10-ElgNB)

Five mothers volunteered that the birth of a male child was a “good delivery”, attributing this to providence (“god’s wish” or “luck”). This was particularly apparent in the joyful accounts of two mothers who had delivered a male child after three or four female children. One mother had changed hospital after delivering her four daughters in the same institution, in the belief that this would turn her luck, and was very satisfied with her overall delivery experience due to the birth of a boy. A mother who had delivered her third daughter was scolded by her mother-in-law in front of the interviewers. She felt that she had not been given adequate care at the hospital and that her money ought to be returned. Another mother-in-law stated that although they had to spend a lot of money on a caesarean for her daughter-in-law, “at least she bore a son!” She contrasted this with her other daughter-in-law who had incurred the expense of a caesarean and then had given birth to a female child. Even for the first child, a boy was explicitly seen as more welcome by some, because, as a father said, “a daughter may bring shame to the family”.

Finally, quite a few participants stated that if they didn’t have to spend money on the birth, they would count it as good. It was customary at all private hospitals to take a cash deposit along with the documentary proof of poverty in the prescribed CY form at the time of admission from all eligible mothers. Those mothers who were later approved by the state to receive the CY benefit were contacted by telephone and a relative would go to the hospital where he would be reimbursed Rs 2400 (US$ 40) towards birth costs and Rs 200 (US$ 3.3) towards travel costs.Citation23 Thus, the CY programme was perceived as one in which they may get money back from the private hospital, not as a cashless programme.

The six eligible families that had received the benefit in this manner had already spent more than this amount on the birth. None reported better perceived quality because of this reimbursement. However, there were eligible families who did not satisfy the criteria to receive CY benefit. The importance of a free delivery was a common refrain among these families.

“Delivery should be normal; and it should be free. That is a good delivery.” (DM9-ElgNB)

Timely attention

A second dimension of quality expressed by most women was that providers’ responses should be timely and prompt, in terms of “making a case paper”, “doing check-ups” and “starting treatment”. This dimension cohered with the desired outcome of a “quick” birth. They wished to be quickly relieved of the “hairaani/takleef” i.e. the “harassment/suffering” of labour pains.

“She (the nurse) made case papers as soon as we reached hospital; they checked baby’s status and they did delivery after putting me on bottle (intravenous drip).” (DM1-ElgNB)

“Starting treatment”, meant quick initiation of medical intervention. They expected that an intravenous drip, a “bottle”, should be administered immediately on arrival. Most women reported that an IV drip had been started on arrival during their recent birth. They conceptualised labour as a process of increasing “heat” culminating in birth which should be hastened by medical intervention for a quick “good delivery”. Most mothers did experience quick deliveries, but they were unable to confirm for certain whether they had been administered any drug for this purpose.

“That (I) do not know, about medicine in bottle … pain increases after the bottle … [which is] given for [increasing] hotness. This is given to all. If hotness persists, then pain will start early. If not, the pain will get cold … so delivery will not happen.” (DM3-NonElg’s mother-in-law)

Finally, timely attention also included attention and responsiveness to problems during labour by “frequently checking and giving strength”.

Perceived competence of providers

The third dimension of quality expressed by mothers and their families was their perception of providers’ competence, expressed as “a good ‘sara’ doctor”. This assured them of their primary desired outcome of “saving lives” of mother and child.

Most of the women were very satisfied with the competence of the provider who had provided them care. Stories of instances when doctors had “saved” mothers and babies during complicated deliveries were shared widely through social networks, and attracted mothers to these facilities. One mother whose baby was horizontally placed in the womb went through a lot of pain as the doctor internally turned the baby and delivered her. The baby was “so silent” after being born that everyone was very scared. She and her family were very grateful that the doctor had saved her and her baby. The CY partnership status of a facility was not widely known, nor a reason for its selection for birthing.

In our sample, four mothers had needed a caesarean section, and although all of them were displeased about it, they had reasoned with themselves about the need for it. Even the mother-in-law who was displeased with the physical effects of the caesarean and its high cost reasoned,

“My daughter in law’s treatment was done well, what else to be thought? … She had a lot of leakage of water so the baby had gone dry. … The doctor tried very well … .caesarean was a compulsion.” (SM7-ElgB Mother-in-law)

“If we go to public hospital, it is big, so it is better equipped to manage conditions like convulsions. But there they don’t examine you properly. Here, in private, you get intelligent and clever doctors, like [name of the provider who treated his daughter-in-law].” (DM3-ElgBen father-in-law [village headman])

The family members of a mother whose blood report showed haemoglobin of 7 g did not understand the risk to the mother’s health, and consequently reported refusing treatment.

“After the delivery, she was feeling giddiness; so she was told to be given a bottle of blood … No, we didn’t want that bottle.” (DM10-ElgB)

Interpersonal emotional support

Most mothers reported positive experiences of caring attitudes and behaviour by providers. Caring behaviour took the form of endearments, holding hands, rubbing the back or abdomen, or words of encouragement. One mother said the doctor cracked jokes to make everyone in the labour room, including her, laugh. Another remarked that she wasn’t made to feel guilty when her vomit went out of the bucket, and the attendant kindly assured her that she would clean it up.

A few mothers reported episodes of both abusive and indifferent behaviour from staff during birthing. In one case, where such behaviour by a nurse was noticed by the doctor, she was reproached for it.

“When I felt the pain … so I shouted … I was scolded by the nurse, she said … ‘keep your mouth shut’. She spoke such abusive language, that I cannot tell you. Doctor scolded her [the nurse] for this.” (DM10-ElgB)

“She didn’t let me groan. She didn’t let me shout. She did not even put her hand on me. Delivery happened on its own. [She] only caught the boy directly.” (DM7-ElgB)

The mother who was not touched at all during her birthing pains and who was repeatedly told not to shout summarised her birth experience as “My treatment was ‘asal’ [meaning perfect, just as it should be].” (DM7-ElgBen)

Physical environment

Comfort, cleanliness, and emergency care infrastructure and equipment were important features of good quality of care to mothers and their families. Women expressed the importance of a “proper place” for delivery with privacy, clean rooms and clean toilets.

“The things like the machine for the baby [incubators], the bottles, the rooms, bed sheet and the bed also, everything was good there. The fan was there, they used to mop [the floor] three and four times daily with phenyl so all those facilities were good. Only, there was nothing to kill the mosquitoes.” (SM12-Inelg)

A minority of patients and families expressed dissatisfaction due to lack of water and mosquitoes. One mother was left on the labour table all through the night because there was no empty bed in the ward. She could not sleep due to the bad smell and had a headache. One family was disconcerted about the lack of neonatal services, and another about laboratory services within the hospital. Although they recognised deficiencies, they would not describe them as poor quality of care, even when prompted to reflect back on overall quality of care. The mother who did not sleep through the night was happy that “they admitted us, quickly, we [I] became free, delivery became, we were [I was] getting harassed [by labour pains], it got cured … ” The mothers and families who felt that laboratory and neo-natal services should be available within the hospital expressed satisfaction with overall care because they got providers’ attention, timely medicines and injections and mother and baby were saved.

Regardless of their CY eligibility status, women in our study reported similar experiences. None of them voluntarily reported being differentially treated because of belonging to an economically or socially vulnerable group, not even when prompted regarding the same. When they were specifically asked towards the end of the interview whether they had experienced or seen any differential treatment of mothers who were eligible for CY benefit, they dismissed the notion as non-existent.

“ … so, we know, that if she (any woman) fills the form, she will get some financial benefit. Treatment, she will get equal, whether she pays the money or not.” (SM15-ElgBen)

Discussion

Irrespective of their poverty or tribal status, there were some common themes in mothers’ and families’ perceptions of a good quality birth. A key concern overriding all others was the importance of the outcome, that is, the need for mother and baby to be “saved” (survive the risky process of childbirth). Other common dimensions of the ideal birthing experience were birthing a male child vaginally, with the shortest possible period of pain, and preferably free of charge. This perfect outcome was wished for within the larger uncertain territory of fears such as the mother’s or baby’s death, a caesarean section, and an episiotomy, which would qualify as poor quality care. They feared caesareans and episiotomies because they believed these would interfere with their future ability to perform physical labour. These uncertainties were addressed by choosing a “good” doctor and facility. They also wanted timely attention, responsiveness, caring attitudes and behaviour. Although the ideal birthing experience was desirable, exiting the hospital with a healthy mother and baby resulted in mothers and families overlooking any negative experiences and reflecting back on their experience as a “good (sari) delivery”.

The overriding need for mother and baby to survive was fundamental to all the characteristics of an ideal birth experience. In Madhya Pradesh too, poor rural mothers who birthed in public facilities declared that in the case that they perceived any risk to themselves or their unborn babies, they would go to a private hospital to ensure a safe birth.Citation29 This centrality of survival of the mother and the newborn to the perception of quality of maternity care has been established in studies from many LMICs.Citation38–40

Birth of a male child was an important component of an ideal birthing experience. Although no other studies report this as a feature of perceived quality of maternity care, it is hardly surprising, since there is strong evidence for its opposite. Studies from India, Nigeria, and Turkey have reported a significant association between the birth of a girl and post-natal depression.Citation41–43 This has been attributed to son preference in traditionally patriarchal societies. Thus, a family’s perceptions of the quality of care received are also likely to be swayed by the gender of the newborn. Our study indicates that women and their families are generally more satisfied when they have a son.

A number of women and families in our study from all categories stated that a free of charge (no expense) childbirth would be a “good delivery”. Most of these mothers had borrowed money and had spent $US 17–107 on this birth.Citation23 A systematic review of 14 studies of four publicly financed health insurance schemes across India reported in 2017 that out-of-pocket and catastrophic expenditure actually increased despite these schemes.Citation44 This suggests that the absence of cashless services in the CY programme of Gujarat was a reflection of practices in other parts of the country in similarly financed schemes. The CY programme was intended to provide childbirth services, with no out of pocket expense from the user, particularly as the users targeted by the programme were vulnerable women from tribal communities or women living below the poverty line. However, the administration of the programme has resulted in all eligible women (ultimate beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries) paying out of pocket upfront, and receiving their cash deposits back only after their papers are deemed eligible to receive the CY benefit by public health officials. Such a system protects the private facility, but does not offer any relief to the vulnerable women, who will likely need to borrow or sell assets to finance a down payment, as was the case for 20 of the 30 mothers in our sample. Assured cashless services for childbirth would go a long way towards alleviating economic hardships for vulnerable women, and help bring these poor and vulnerable women under the ambit of universal health coverage, a stated objective of national health policy. Inefficiencies in the programme that create uncertainty for families need to be identified and removed if universal health coverage is to be achieved. The uncertainty of the extent of additional out-of-pocket expenditure can deter mothers from institutional births, as seen among poor communities from Vietnam, Cambodia and Gambia.Citation23,Citation38,Citation45 Therefore, it is important that any programme designed to increase institutional births must also ensure cashless services. Otherwise, the objective of universal institutional birthing would be defeated.

In both districts, mothers and families characterised the physiological driver of birthing as “heat”. The women believed that medical manipulation of “heat” to hasten birthing had been employed during their childbirths and this was an important characteristic of good quality care. However, episiotomy and caesarean sections, also medicalised birthing procedures, were feared. These procedures were believed to compromise the future capacity for physical work. The desire to shorten the period of labour is a recurring theme in Indian qualitative studies, although the reasoning underlying this has not been adequately explored.Citation27,Citation29,Citation46,Citation47 In China, fear of labour pain has been one of the factors driving the increased demand for caesarean sections.Citation40 On the contrary, in South India, the intense labour pain due to oxytocics is considered valorous and a spiritual experience.Citation48 Irrespective of the reasons for this demand, the widespread practice of administering oxytocin to home and public hospital births in India is well documented.Citation49,Citation50 There is a need to study the prevalence of this practice in the private sector, particularly in light of recent studies in suburban New Delhi and Haryana which showed how commercial interests contribute to both high caesarean rates and oxytocin use for accelerated labour in private practices.Citation51,Citation52 There is a need to specifically institute mechanisms in labour wards and waiting rooms to encourage responsible and timely communication from providers to women and their families, regarding clinically indicated practices.

Mothers and families desired competent and compassionate providers and well equipped facilities. They were satisfied with these aspects in their recently concluded births. Given their lack of biomedical knowledge, people used knowledge from social networks across broad criteria such as deaths and level of intervention during emergencies to decide on a provider’s reputation as a “good doctor”. We did not find any evidence that people perceived a CY partnering provider as grounds for being a “good doctor”. They did not select a facility to give birth in based on its CY status.

Our study came across occurrences of poor clinical care by providers and lack of compliance with clinical advice by users in CY facilities. The “good doctor” yardstick was limited by information asymmetry for high-risk mothers. Thus the reliance on doctors’ and facilities’ “reputations” fell short of satisfying their desired goal of competent providers for “saving” mother and child. A study in Uttar Pradesh has shown that clinical maternal care is compromised by harmful practices adopted by private providers, as much as by public providers.Citation30 Commercial interests also influence clinical decision in the private system.Citation52 This highlights the need for empowering people to engage better with the health system. Not only do people need factual information, “functional health literacy”, regarding common pathologies that can lead to maternal deaths; over time, they need to develop personal and community skills, “interactive and critical health literacy”, to initiate individual and social actions to participate in the organisation of health systems around them.Citation53

Literature indicates that poor women experience poorer quality of care.Citation24,Citation54 But CY eligible (beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries) and ineligible mothers in our sample did not report any discrimination. Since our study site was located in remote small towns in poor districts, the private facilities in our sample were serving a relatively socio-economically homogenous population, where there was not much perceptible difference between households. Also, only eligible mothers whose papers were in order received benefit retrospectively. This may have resulted in delivery of a uniform quality of care to all patients. Possibly, mothers did not stay in facilities long enough to compare the care they received with that of others. However, another study of two community health insurance schemes also found no difference in patient satisfaction among insured and uninsured clients of the same health facilities. Dissatisfaction was due to poor outcomes such as death or persistent symptoms despite treatment.Citation55 A recent study in Uttar Pradesh detected mistreatment of mothers to be very high, nearly 100%, and that it was as high in private as public facilities.Citation30 This indicates that private facilities in public-private-partnerships may provide the same perceived quality of care to paying and non-paying clients.

Whilst women and families identified issues that they disapproved of during their care (e.g. rudeness and lack of cleanliness), they did not judge these as poor quality of care, when the birth outcome was favourable. This was observed in Andhra Pradesh too, where patients recognised poor services in private facilities, but were not dissatisfied. They would repeatedly contrast the government sector where doctors and facilities were sparse, with private facilities where doctors were always available.Citation56 Numerous researchers have established that patients’ perceptions of their experiences cannot be equated with their satisfaction,Citation57,Citation58 particularly in maternity care.Citation59 High satisfaction can obscure negative experiences, perhaps due to low expectations, which are in part set by poor quality in the public sector.Citation60 Therefore, qualitative indicators of experience, rather than crude indicators of “satisfaction”, need to be collected in order to truly assess clients’ experience of care and to steer the quality of care provided by these facilities. In our setting, there is a need to explore satisfaction and experience in light of the possibility that women undergo maternity care as a collective experience with their families.

We found in our study that women’s core definition of good quality care – survival of mother and baby – was common across cultures.Citation23,Citation27,Citation29,Citation38,Citation40 Furthermore, our key findings, the expectation of being administered “medicines” to reduce the period of pain, the identification of “good” doctors and facilities based on reputation, lack of information about necessary treatment protocols and facility standards to be able to address risks to maternal life, and acceptance of a “deposit” payment system in lieu of receiving the CY benefit, are deeply rooted in the beliefs, values and social relations of the people and the nature of the private health system. Although our data were collected in 2013, our study collects these diverse issues and sheds fresh light on the underlying processes that must be addressed in a newer systematic way within the format of the recently instituted Ayushman Bharat programme. The intervening years would be unlikely to change the enduring beliefs, values and social relationships that are largely responsible for our findings on the ground, especially in the absence of any recent structural changes in the public and private health sector. Since the Ayushman Bharat has been launched across the country in 2018, our findings provide insights that can inform better designing and implementation of relevant parts of this national enterprise to attain universal health coverage for maternal health.

Methodological considerations

We had planned to conduct in-depth interviews with the mothers, but these turned into small family group interviews before we could interview the mothers alone. We established a rapport with the families and mothers in the safety of their homes, and then created a relatively private space for mothers to express their perceptions. However, it is possible that despite our attempts, mothers were unable to express their true perceptions. For example, rural and tribal mothers and families could have downplayed their negative feelings because they were faced with urban, educated interviewers who were likely associated in their minds with service providers.Citation61 In addition, mothers- (and grand-mothers) -in-law were often present, which may have set expectations on mothers not to complain. However, we did interview all the mothers alone for a quarter to half an hour, and were able to record their perceptions regarding their birth experiences. We recorded two mothers’ disappointment with the lack of support from their family members during labour.

We interviewed women relatively soon after they had given birth. Our participants were very satisfied with the care they had received. There is a possibility that the relief of survival masked some of their negative experiences. Mothers have been shown to change their assessment of their birth experiences from positive to less positive after a year.Citation62

The authors involved in the study are from biomedical and social sciences disciplines. This has allowed for triangulation during analysis of the data, enabling us to recognise the larger socio-economic processes relevant to perceptions of clinical care. Our findings would be typical of populations in socio-economically and developmentally similar districts in India.

Conclusion

The overriding importance of a safe birth outcome – healthy mother and child – without surgical interventions was the key characteristic of “good quality care”. This outcome allowed women and their families to overlook negative experiences they may have encountered in the facility they birthed in. The frame of reference when evaluating their present experiences in private facilities, was the widespread perception, based on collective experience, of the unresponsive care in the public health system. In contrast, in the private sector, the women had received prompt attention, intravenous drips and generally caring behaviour. However, there were instances which revealed poor standards of clinical and respectful care by providers and misconceptions regarding medical induction of labour among mothers and families. Birthing in a CY facility did not provide relief from out-of-pocket expenditure. Inefficiencies in the programme have resulted in a deposit payment system which creates uncertainty for families regarding expenditure. As a result, the CY programme was perceived as one in which beneficiaries may receive back some or all of their deposit, not as a cashless service.

As the world’s largest state-sponsored health insurance programme, the Ayushman Bharat, recruits private obstetricians across the country as a quicker way to achieve universal health coverage, three key takeaways from this study are of relevance for maternity care. First, monitoring mothers’ experiences, rather than satisfaction, at these facilities, such as through the MyHospital application, is more valuable for assessing quality of care. Qualitative indicators to measure experience of birthing by the mother and her family need to be developed. Second, health literacy of communities should be improved so that skills can be built to allow people to participate better in the health system around them. Third, the need to ensure cashless services cannot be emphasised enough. In order that public-private-partnerships achieve their goal of providing universal health coverage, it is essential that the most vulnerable families are assured of the cashless nature of these services.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the study participants. This research was funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program under grant agreement no [261304].

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA WBG and the UNPD. Trends in maternal mortality : 2000 to 2017. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division; 2019.

- Campbell OM, Graham WJ. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. The lancet. 2006; 368(9543):1284–1299.

- World Health Organization. Department of reproductive health and research. Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant. A joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2004.

- Joe W, Perkins JM, Kumar S, et al. Institutional delivery in India, 2004-14: unravelling the equity-enhancing contributions of the public sector. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(5):645–653.

- Sengupta A, Nundy S. The private health sector in India. Br Med J. 2005; 331:1157–1158.

- GoI M. Rural health statistics 2014–15 [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2020 Jun 20]. Available from: https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/RHS_1.pdf.

- FOGSI. The federation of obstetric and gynaecological societies of India – 53rd annual report and statement of accounts [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2020 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.fogsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/pdf/FOGSI_Annual_Report_2012_13.pdf.

- Kane S, Calnan M. Erosion of trust in the medical profession in India: time for doctors to act. Int J Heal Policy Manag [Internet]. 2017;6(1):5–8. [cited 2020 Jun 27]. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5193507/?report = abstract.

- GoI M. National program implementation plan RCH phase II – program document. New Delhi; 2008.

- Rao P. The private health sector in India: a framework for improving the quality of care. ASCI J Manag. 2012;41(2):14–39.

- Mavalankar D, Singh A, Patel SR, et al. Saving mothers and newborns through an innovative partnership with private sector obstetricians: Chiranjeevi scheme of Gujarat, India. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009; 107:271–276.

- NSSO, MoS&PI G. Health in India. NSS 71st round. Jan–Jun 2014 [Internet]. New Delhi: MoSPI; 2016; 53 p. Available from: http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/nss_rep574.pdf.

- Jain N, Kumar A, Nandraj S, et al. NSSO 71st round same data, multiple interpretations. Econ Polit Wkly [Internet]. 2015;1(46 &47):84–87. [cited 2020 Jun 24]. Available from: https://niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-01/NSSO_71st_Round _Final.pdf.

- GoI NHA. Home | Ayushman Bharat | National Health Authority | GoI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 15]. Available from: https://www.pmjay.gov.in/.

- Angell BJ, Prinja S, Gupt A, et al. The Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana and the path to universal health coverage in India: overcoming the challenges of stewardship and governance. PLoS Med. 2019;16(3):e1002759.

- Mohanan M, Hay K, Mor N. Quality of health care in India: challenges, priorities, and the road ahead. Health Affairs. 2016 ;35(10):1753–1758.

- Sharma KD. Implementing quality process in public sector hospitals in India: the journey begins. Indian J Community Med. 2012 ;37(3):150.

- GoI M. My Hospital [Internet]. Available from: https://meraaspataal.nhp.gov.in/.

- Jolivet RR. I169 the respectful maternity care charter: a collaborative work. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012;119(2012):S203–S203.

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. Jewkes R, editor. PLOS Med [Internet]. 2015 Jun 30;12(6):e1001847. [cited 2020 Jun 26]. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847.

- Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. The lancet. 2006; 368(9542):1189–1200.

- Srivastava A, Avan BI, Rajbangshi P, et al. Determinants of women’s satisfaction with maternal health care: a review of literature from developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2015 Dec 12;15(1):1–12. [cited 2020 Jun 26]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-015-0525-0.

- Duong DV, Binns CW, Lee AH. Utilization of delivery services at the primary health care level in rural Vietnam. Soc Sci Med. 2004; 59(12):2585–2595.

- Koblinsky M, Moyer CA, Calvert C, et al. Quality maternity care for every woman, everywhere: a call to action. The Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2307–2320.

- Kruk ME, Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, et al. Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: a facility and community survey. Health Policy Plan. 2018 ;33(1):e26–e33.

- Bohren MA, Hunter EC, Munthe-Kaas HM, et al. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health. 2014; 11(1):71.

- Bhattacharyya S, Srivastava A, Avan BI. Delivery should happen soon and my pain will be reduced: understanding women’s perception of good delivery care in India. Glob Health Action. 2013; 6(1):22635.

- Bhattacharyya S, Issac A, Rajbangshi P, et al. “Neither we are satisfied nor they” – users and provider’s perspective: a qualitative study of maternity care in secondary level public health facilities, Uttar Pradesh, India. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2015 Sep 27;15(1):421. [cited 2020 Jun 24]. Available from: http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-015-1077-8.

- Sidney K, Tolhurst R, Jehan K, et al. “The money is important but all women anyway go to hospital for childbirth nowadays” – a qualitative exploration of why women participate in a conditional cash transfer program to promote institutional deliveries in Madhya Pradesh, India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016; 16(1):47.

- Sharma G, Penn-Kekana L, Halder K, et al. An investigation into mistreatment of women during labour and childbirth in maternity care facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India: a mixed methods study. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2019 Jan 23;16(1):1–16. [cited 2020 Jun 25]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-019-0668-y.

- Levering B. Epistemological issues in phenomenological research: how authoritative are people’s accounts of their own perceptions? J Philos Educ. 2006; 40(4):451–462.

- Social Science Academy of Nigeria. Ethics for public health research in Africa Social Science Academy of Nigeria ethics for public health research in Africa. International Workshop in Collaboration with the special programme for research and training in tropical diseases of the World Health Organisation. 2008. 1–79 p.

- Iyer V, Sidney K, Mehta R, et al. Availability and provision of emergency obstetric care under a public–private partnership in three districts of Gujarat, India: lessons for universal health coverage. BMJ Glob Heal. 2016 ;1(1):e000019.

- Sidney K, Iyer V, Vora K, et al. Statewide program to promote institutional delivery in Gujarat, India: who participates and the degree of financial subsidy provided by the Chiranjeevi Yojana program. J Heal Popul Nutr. 2016; 35(1):2.

- Gordon EJ. When oral consent will do. Field Methods [Internet]. 2000 Aug 24;12(3):235–238. [cited 2020 Oct 24]. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1525822X0001200304.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013; 13(1):1–8.

- Iyer V, Sidney K, Mehta R, et al. Characteristics of private partners in Chiranjeevi Yojana, a public-private-partnership to promote institutional births in Gujarat, India – Lessons for universal health coverage. PLoS One. 2017;12(10): e0185739.

- Cham M, Sundby J, Vangen S. Availability and quality of emergency obstetric care in Gambia’s main referral hospital: women-users’ testimonies. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2009 Dec 14;6(1):5. [cited 2020 Jun 9]. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1742-4755-6-5.

- D’Ambruoso L, Abbey M, Hussein J. Please understand when I cry out in pain: women’s accounts of maternity services during labour and delivery in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2005; 5(1):140.

- Raven J, van den Broek N, Tao F, et al. The quality of childbirth care in China: women’s voices: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):1–8.

- Patel V, Rodrigues M, DeSouza N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: a study of mothers in Goa, India. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 ;159(1):43–47.

- Adewuya AO, Fatoye FO, Ola BA, et al. Sociodemographic and obstetric risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms in Nigerian women. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005; 11(5):353–358.

- Dindar I, Erdogan S. Screening of Turkish women for postpartum depression within the first postpartum year: the risk profile of a community sample: special features: practice concepts. Public Health Nurs. 2007 ;24(2):176–183.

- Prinja S, Chauhan AS, Karan A, et al. Impact of publicly financed health insurance schemes on healthcare utilization and financial risk protection in India: a systematic review [Internet]. PLoS ONE. 2017 ;12(2):e0170996. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.

- Ith P, Dawson A, Homer CSE. Women’s perspective of maternity care in Cambodia. Women Birth [Internet]. 2013 Mar 1;26(1):71–75. [cited 2020 Jun 9]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2012.05.002.

- Sharma B, Giri G, Christensson K, et al. The transition of childbirth practices among tribal women in Gujarat, India – a grounded theory approach. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013 ;13(1):1–15.

- Barnes L. Women’s experience of childbirth in rural Jharkhand. Econ Polit Wkly. 2007: 62–70.

- Van Hollen C. Invoking vali: painful technologies of modern birth in south India. Med Anthropol Q. 2003 ;(1):49–77.

- Flandermeyer D, Stanton C, Armbruster D. Uterotonic use at home births in low-income countries: a literature review. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010 Mar 1;108(3):269–275.

- Stanton CK, Deepak NN, Mallapur AA, et al. Direct observation of uterotonic drug use at public health facility-based deliveries in four districts in India. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014 Oct 1;127(1):25–30.

- Silan V, Kant S, Archana S, et al. Determinants of underutilisation of free delivery services in an area with high institutional delivery rate: a qualitative study. N Am J Med Sci. 2014 ;6(7):315.

- Peel A, Bhartia A, Spicer N, et al. “If I do 10–15 normal deliveries in a month I hardly ever sleep at home.” A qualitative study of health providers’ reasons for high rates of caesarean deliveries in private sector maternity care in Delhi, India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2018 Dec 3;18(1):1–11. [cited 2020 Jun 25]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-018-2095-4.

- Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000 ;15(3):259–267.

- Sharma J, Leslie HH, Kundu F, et al. Poor quality for poor women? Inequities in the quality of antenatal and delivery care in Kenya. PLoS One. 2017 ;12(1):e0171236.

- Devadasan N, Criel B, Van Damme W, et al. Community health insurance schemes & patient satisfaction – evidence from India. Indian J Med Res. 2011 ;133(1):40.

- George A. Quality of reproductive care in private hospitals in Andhra Pradesh. Econ Polit Wkly. 2002 :1686–1692.

- Haas M. The relationship between expectations and satisfaction: a qualitative study of patients’ experiences of surgery for gynaecological cancer. Heal Expect [Internet]. 1999 Mar 25;2(1):51–60. [cited 2020 Jun 19]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1369-6513.1999.00037.x.

- LaVela S, Gallan A. Evaluation and measurement of patient experience. Patient Exp J. 2014 ;(2):75–82.

- Van Teijlingen ER, Hundley V, Rennie AM, et al. Maternity satisfaction studies and their limitations: “What is, must still be best”. Birth. 2003; (2):75–82.

- Needham BR. The truth about patient experience: what we can learn from other industries, and how three Ps can improve health outcomes, strengthen brands, and delight customers. J Healthc Manag. 2012; 57(4):255–263.

- Kvale S. Dominance through interviews and dialogues. Qual Inq. 2006.

- Waldenström U. Why do some women change their opinion about childbirth over time? Birth. 2004; 31(2):102–107.