Abstract

We conducted a scoping review to map the extent, range and nature of the scientific research literature on the reproductive health (RH) of transgender and gender diverse assigned female at birth and assigned male at birth persons. A research librarian conducted literature searches in Ovid MEDLINE®, Ovid Embase, the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Google Scholar, Gender Studies Database, Gender Watch, and Web of Science Core Collection. The results were limited to peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2000 and 2018 involving human participants, written in English, pertaining to RH, and including disaggregated data for transgender and gender diverse people. A total of 2197 unique citations with abstracts were identified and entered into Covidence. Two independent screeners performed a title and abstract review and selected 75 records for full-text review. The two screeners independently extracted data from 37 eligible articles, which were reviewed, collated, summarised, and analysed using a numerical summary and thematic analysis approach. The existing scientific research literature was limited in terms of RH topics, geographic locations, study designs, sampling and analytical strategies, and populations studied. Research is needed that: focuses on the full range of RH issues; includes transgender and gender diverse people from the Global South and understudied and multiply marginalised subpopulations; is guided by intersectionality; and uses intervention, implementation science, and community-based participatory research approaches. Further, programmes, practices, and policies that address the multilevel barriers to RH among transgender and gender diverse people addressed in the existing scientific literature are warranted.

Résumé

Nous avons réalisé une étude bibliographique pour répertorier l’étendue, la portée et la nature des publications sur la recherche scientifique relative à la santé reproductive des personnes transgenres ou de genre divers désignées de genre féminin à la naissance (AFAB) et désignées de genre masculin à la naissance (AMAB). Une bibliothécaire a mené des recherches documentaires sur Ovid MEDLINE®, Ovid Embase, la Cochrane Library, PubMed, Google Scholar, Gender Studies Database, Gender Watch et Web of Science – Core Collection. Les résultats étaient limités aux articles de revues à comité de lecture publiés entre 2000 et 2018 avec des participants humains, rédigés en anglais, en rapport avec la santé reproductive et qui comprenaient des données ventilées pour les personnes transgenres et de genre divers. Un total de 2197 documents avec des résumés ont été identifiés et enregistrés dans Covidence. Deux personnes indépendantes chargées de la sélection ont analysé les titres et les résumés et 75 entrées ont été retenues pour un examen du texte intégral. Les deux sélectionneurs ont extrait de manière indépendante des données de 37 articles éligibles, qui ont été examinées, compilées, résumées et analysées à l’aide d’une méthode de synthèse numérique et d’analyse thématique. Les publications disponibles sur des recherches scientifiques étaient limitées du point de vue des thèmes de santé reproductive, des lieux géographiques, des conceptions des études, des échantillons et des stratégies d’analyse, ainsi que des populations étudiées. Nous avons besoin de recherches qui se concentrent sur tout l’éventail des questions de santé reproductive, qui comprennent les populations transgenres et de genre divers originaires des pays du Sud ainsi que des sous-populations sous-étudiées et marginalisées à plus d’un titre, des recherches qui soient guidées par l’intersectionnalité et aient recours à l’intervention, aux sciences de l’implémentation et à des approches de recherche participative à assise communautaire. Des programmes, des pratiques et des politiques portant sur les obstacles à la santé reproductive sur plusieurs niveaux parmi les personnes transgenres et de genre divers qui sont traités dans les publications scientifiques existantes sont aussi justifiés.

Resumen

Realizamos una revisión de alcance para mapear el alcance, la extensión y la naturaleza de la literatura de investigaciones científicas sobre la salud reproductiva de personas transgénero y de género diverso asignadas el género femenino al nacer (AFAB) y asignadas el género masculino al nacer (AMAB). Una bibliotecaria de investigación realizó búsquedas de la literatura en Ovid MEDLINE®, Ovid Embase, la Biblioteca de Cochrane, PubMed, Google Scholar, la Base de Datos de Estudios de Género, Gender Watch y en la Colección Principal de Web of Science. Los resultados fueron limitados a artículos en revistas revisadas por pares, publicados entre los años 2000 y 2018, con participantes humanos, redactados en inglés, relativos a la salud reproductiva, y que incluían datos desagregados para personas transgénero y de género diverso. Un total de 2,197 citas únicas con resúmenes fueron identificadas e ingresadas en Covidence. Dos examinadores independientes realizaron la revisión de títulos y resúmenes, y 75 registros fueron seleccionados para la revisión del texto completo. Los dos examinadores extrajeron independientemente datos de 37 artículos elegibles, que fueron revisados, compilados, resumidos y analizados utilizando un resumen numérico y el enfoque de análisis temático. La literatura existente de investigaciones científicas estuvo limitada con relación a los temas de salud reproductiva, lugares geográficos, diseños de estudio, muestreo, estrategias analíticas y poblaciones estudiadas. Se necesitan investigaciones enfocadas en la gama completa de temas de salud reproductiva, que incluyan a personas transgénero y de género diverso del Sur Global, así como a subpoblaciones poco estudiadas y múltiples subpoblaciones marginadas, que estén guiadas por la interseccionalidad, y que utilicen enfoques de intervención, de ciencia de la implementación y de investigación participativa comunitaria. Además, se necesitan programas, prácticas y políticas que aborden las barreras multinivel a la salud reproductiva entre personas transgénero y de género diverso tratadas en la literatura científica existente.

Introduction

In 1994, the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) defined reproductive health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relating to the reproductive system and to its functions and processes”.Citation1 The ICPD agreed on a broad definition of reproductive health that includes a quality and safe sex life, the opportunity to reproduce, and the autonomy to decide if, when, and how to pursue reproduction.Citation2,Citation3 While some progress has been made, the reproductive health and rights of all groups – especially those who are socially and economically marginalised as a result of structural and interpersonal discrimination – have yet to be actualised.Citation4–6 In particular, transgender and gender diverse people – namely, people whose gender identity differs from social expectations based on their sex assigned at birth (e.g. transgender women, transgender men, non-binary, gender non-conforming, genderqueer, gender fluid, Two Spirit, and agender individuals) – experience pronounced barriers to reproductive health and rights as a result of bias, stigma, and discrimination within political, economic, social, education and healthcare structures and institutions.Citation7–9

Research shows that transgender and gender diverse assigned female at birth (AFAB) people (i.e. people assigned female at birth who identify as men, transgender men, masculine, transmasculine, non-binary, gender non-conforming, genderqueer, gender fluid, Two Spirit, and/or agender, among other identities) have various unmet reproductive health needs.Citation10,Citation11 For instance, although transgender and gender diverse AFAB people can experience pregnancy,Citation12–14 they face notable barriers to contraception, including limited access to high-quality health care, a lack of healthcare provider training and competence in transgender health, cis- and hetero-normative healthcare provider assumptions, and gender identity-related bias, stigma, and discrimination in healthcare settings in particular, and society in general.Citation15–17 Similarly, research shows that transgender and gender diverse AFAB people are also less likely to obtain regular Pap tests compared to cisgender women (i.e. AFAB individuals who identify as women in terms of gender identity) as a result of institutional discrimination in healthcare systems, a lack of healthcare provider knowledge and training, and limited access to gender-affirming care.Citation18

Additionally, although many transgender and gender diverse AFAB people have expressed an interest in pregnancy, childbearing, and parenthood,Citation19–21 studies indicate that they also face notable challenges in these areas, including limited access to gender-affirming fertility preservation and assisted reproduction services and erasure, stigma, and discrimination in the reproductive healthcare system in particular and society in general.Citation5,Citation7,Citation9,Citation22 Similarly, transgender and gender diverse assigned male at birth (AMAB) individuals (i.e. people assigned male at birth who identify as women, transgender women, feminine, transfeminine, non-binary, gender non-conforming, genderqueer, gender fluid, Two Spirit, and/or agender, among other identities) also experience notable challenges to becoming parents. Indeed, although many transgender and gender diverse AMAB people report a desire to have children,Citation21,Citation23,Citation24 they experience significant barriers in accessing and utilising fertility preservation and assisted reproduction services, including a lack of gender-affirming healthcare providers and organisations that competently and respectfully address their fertility intentions and desires and reproductive health needs and concerns.Citation23–25

To our knowledge, the extent, scope, and nature of research on the reproductive health of transgender and gender diverse AFAB and AMAB people has yet to be characterised. Therefore, we conducted a scoping review to systematically identify, ascertain, and summarise the research literature on the reproductive health of transgender and gender diverse AFAB and AMAB individuals.Citation26–28 The results of this scoping review will allow us to make recommendations for future research, practice, and policy on reproductive health among transgender and gender diverse people, with the goal of advancing the reproductive health and rights of this structurally marginalised and medically underserved population.

Methods

Scoping reviews are an approach to knowledge synthesis that incorporates a range of study designs and uses rigorous, systematic, and transparent methods to map the extent, range, and nature of the research literature on a given topic, summarise research findings on this topic, and identify research gaps in the existing literature with the goal of informing future research, policy, and practice.Citation27,Citation28 The purpose of our scoping review was to determine the range and nature of and identify research gaps in the scientific literature on transgender and gender diverse individuals’ reproductive health. We sought to answer the following research question: What is known and what is not known from the scientific literature about the reproductive health needs and experiences of transgender and gender diverse AFAB and AMAB people? We then identified, selected, charted, and summarised relevant studies using the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley.Citation27 Our approach also incorporated Levac et al.’sCitation26 adaptations to the Arksey and O’MalleyCitation27 framework, including linking the scoping review purpose and research question, using an iterative team-based approach to study selection and data extraction with multiple reviewers, and incorporating both a numerical summary and thematic analysis in the summary and reporting of research findings.

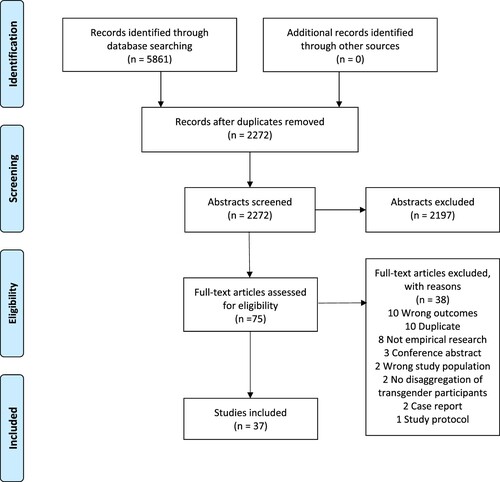

Specifically, a research librarian conducted literature searches for relevant articles in Ovid MEDLINE®, Ovid Embase, the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Google Scholar, Gender Studies Database, Gender Watch, and Web of Science Core Collection. Final searches were performed in all databases on November 7, 2018. Databases were searched using a combination of controlled vocabulary and free text terms (Appendix A). The Yale MeSH Analyzer (http://mesh.med.yale.edu) was used in the initial stages of strategy formulation to harvest controlled vocabulary and keyword terms from relevant known articles included in the MEDLINE database. The results were limited to peer-reviewed journal articles; case reports, commentaries, editorials, newspaper articles, literature or systematic reviews, reports, committee opinions, clinical guidelines, and letters were filtered out. Peer-reviewed journal articles were included if they were published between 2000 and 2018, involved human participants, were written in English, pertained to a reproductive health topic, and disaggregated data for transgender and gender diverse people (rather than, for example, presenting aggregate data for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer [LGBTQ] individuals combined). Only studies pertaining to transgender and gender diverse people’s own reproductive health experiences, preferences, concerns, needs, or priorities were included. In contrast, papers that focused on others’ (e.g. health care providers’, family members’) views and experiences pertaining to the reproductive health of transgender and gender diverse people or on transgender and gender diverse people’s reproductive organs or cells rather than their reproductive health outcomes or experiences, were excluded ().

Table 1. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Citations from all databases were imported into an EndNote X9 library. Duplicate citations were removed in Endnote, and final citations and their abstracts were entered into Covidence, a screening and data extraction tool.Citation29 Two independent screeners performed a title and abstract review on all citations based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (). The first author resolved any disagreement on study inclusion (e.g. whether a study had disaggregated data for transgender and gender diverse people, whether a study addressed transgender and gender diverse people’s own reproductive health views and experiences vs. others’ such as their parents) between the screeners. Through this process, the screeners and first author selected records for full-text review, from which the two screeners independently extracted data on study characteristics (i.e. year, country, study design, methodology, methods, and sampling strategy), sample characteristics (i.e. number of transgender and gender diverse study participants and distributions of sex assigned at birth, gender identity, age, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment) and reproductive health topic.

The data extraction form was developed collaboratively by the screeners and first author, tested independently by the two screeners using a subset of the articles, and revised iteratively during the data extraction process. The standard data extraction form in Covidence was supplemented to capture additional study characteristics of interest to the research team, including study samples’ gender identity, racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and age composition. The two independent screeners and the first author reviewed all the extracted data, and all discrepancies (mostly related to study type, sample size, and participant demographic characteristics) between the screeners were resolved by discussion and consensus. The agreed upon extracted data were reviewed, collated, and analysed by the first author in collaboration with the screeners and served as the basis for the results presented in this article. Specifically, they grouped the studies by reproductive health topic, characterised the study population, study design, and sample characteristics for each one, identified research gaps in the scientific literature, and summarised the studies’ main findings using both a numerical summary and thematic analysis approach.Citation26,Citation27 Of note, our scoping review did not include a formal quality assessment of each study, which is not a required component of this approach. However, we globally ascertained to what extent the existing literature provided valid, generalisable, and actionable information on the reproductive health of transgender and gender diverse people.Citation26–28

Results

Our search strategy generated a total of 5861 citations. Duplicate citations were removed, reducing the total number of citations to 2197. The title and abstract review of these citations yielded 75 records for full-text review. A total of 38 articles were excluded from full-text review for not being empirical research (n = 11), having the wrong outcomes (n = 10), being duplicates (n = 7), conference abstracts (n = 3), study protocols (n = 2), or case reports (n = 1), and not disaggregating data for transgender and gender diverse individuals (n = 4; ).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart. Adapted from Moher et al.Citation55

Of the 37 articles included in the full-text review (Appendix B), shows that the vast majority (n = 34, 91.9%) were published after 2013, with a steady increase in the number of articles published between 2014 (n = 4, 10.8%) and 2018 (n = 10, 27.0%). Moreover, most studies were conducted in the United States (n = 25, 67.6%), followed by Canada (n = 6, 16.2%), Australia (n = 2, 5.4%), Belgium (n = 2, 5.4%), Sweden (n = 1, 2.7%) and Germany (n = 1, 2.7%). Further, almost all (n = 36, 97.3%) studies were observational and relied on convenience or purposive sampling strategies (n = 36, 97.3%). Of note, we only identified one (2.7%) intervention research study and one (2.7%) study that utilised a (sub-national) probability sample. Additionally, most studies used quantitative (n = 15, 40.5%), followed by qualitative (n = 13, 35.1%), research methodologies. Approximately one quarter (n = 9, 24.3%) used a mixed-methods research approach that combined both quantitative and qualitative data and two (5.4%) adopted a participatory research methodology. In terms of methods, the majority of studies utilised cross-sectional surveys (n = 17, 46.0%) and/or in-depth interviews (n = 17, 45.9%), followed by clinical chart reviews (n = 7, 18.9%; ).

Table 2. Study characteristics of included articles (N = 37)

shows that the majority (n = 27, 73.0%) of studies relied on samples including fewer than 125 transgender and gender diverse participants. Additionally, most (n = 23, 62.2%) articles included in the full text review solely pertained to the reproductive health of AFAB individuals, including transgender men, transmasculine individuals, and gender diverse AFAB people. Approximately one third (n = 13, 35.1%) included both transgender and gender diverse AFAB and AMAB participants (of which only n = 5, 13.5% included disaggregated study results), while only one (2.7%) study exclusively focused on the reproductive health needs and experiences of AMAB participants. Further, none of the studies included in the full-text review solely pertained to non-binary and other gender diverse individuals, whose needs and experiences were addressed in conjunction with (n = 20, 54.1%) and rarely disaggregated from (n = 2, 5.4%) those of transgender individuals with binary gender identities. Moreover, the vast majority (n = 31, 83.8%) of articles pertained to young and midlife adults, with only three (8.1%) addressing adolescent reproductive health and none addressing the reproductive health concerns of older adults. Almost all studies that specified their sample’s racial/ethnic (n = 24, 64.9%) and educational (n = 17, 45.9%) composition included a majority of White (n = 24/24, 100%) and college-educated (n = 16/17, 94.1%) transgender and gender diverse participants, with no disaggregation of study findings by race/ethnicity or educational attainment in any study (). Moreover, of the studies that reported the racial/ethnic breakdown of participants at all or beyond the proportion of White participants (n = 23, 62%), most included only small numbers of Black, Latinx, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and multiracial individuals. Of note, only four (17%) studies reported including Native, Indigenous, or Aboriginal people (data not shown).

Table 3. Sample characteristics of included articles (N = 37)

Further, we found that the articles included in the full-text review addressed a variety of reproductive health topics and sub-topics (). The topic addressed in the largest number of studies was cervical cancer screening (n = 14, 37.8%), including cervical cancer screening results (n = 2, 5.4%), frequency (n = 6, 16.2%), perceptions, attitudes and preferences (n = 6, 16.2%), experiences (n = 4, 10.8%), and performance (n = 1, 2.7%). Other commonly examined topics were fertility, (n = 10, 27.0%) including fertility desires, intentions, and attitudes (n = 8, 21.6%) and fertility services use and experiences (n = 2, 5.4%); and fertility preservation (n = 8, 21.6%) namely, fertility preservation counselling or consultation (n = 3, 8.1%), fertility preservation services use and experiences (n = 5, 13.5%), and fertility preservation knowledge and attitudes (n = 4, 10.8%). Other less commonly studied topics were pregnancy (n = 7, 18.9%), reproductive health care (in general; n = 2, 5.4%), contraceptive use (n = 3, 8.1%), birth (n = 5, 13.5%), cervical cancer risk perceptions and treatment experiences (n = 2, 5.4%), parenthood experiences (n = 1, 2.7%), and chest feeding experiences (n = 1, 2.7%; ).

Table 4. Reproductive health topic of included articles (N = 37)

In general, researchers found that transgender and gender diverse AFAB and AMAB people faced notable barriers to achieving their fertility intentions and desires due to a lack of access to reproductive health services, including fertility preservation, reproduction assistance, pregnancy-related care, and contraception, that addressed their unique and specific needs. Additionally, when utilising reproductive health services pertaining to pregnancy, birth, contraception and cervical cancer screening, transgender and gender diverse individuals experienced several barriers to obtaining high-quality care, including cost,Citation25,Citation30,Citation31 a lack of health care provider knowledge of and training in transgender reproductive health,Citation5,Citation11,Citation30 non-inclusive and non-affirming clinical environments and practices,Citation5,Citation6,Citation12,Citation32 and gender identity bias, stigma, and discrimination in reproductive healthcare settings and in patient–provider interactions.Citation7,Citation12,Citation15,Citation19,Citation30 Moreover, several studies found that gender dysphoria (i.e. distress due to persistent feelings of conflict between one’s gender identity and sex assigned at birth) also posed a challenge to accessing and utilising reproductive health care,Citation10,Citation13,Citation32 which is often branded as “women’s health care”, among many transgender and gender diverse AFAB individuals.

Discussion

The results of this scoping review suggest several significant gaps in the scientific research literature addressing the reproductive health of transgender and gender diverse AFAB and AMAB people. Although we found that the number of studies focusing on this topic increased between 2010 and 2018, the scientific literature on the reproductive health needs and experiences of transgender and gender diverse people was heavily weighted towards particular countries, study designs, study populations, reproductive health topics, and sampling and analytical strategies. Of note, the majority of studies were conducted in the Global North, especially the United States, and were observational and cross-sectional in nature. In terms of study population, most studies pertained to transgender and gender diverse AFAB individuals, with few articles devoted to or inclusive of transgender and gender diverse AMAB people. Similarly, no study exclusively focused on gender diverse (e.g. non-binary, gender fluid, gender non-conforming, genderqueer, agender) people and almost all of those that included both transgender and gender diverse participants aggregated the data for these distinct gender identity groups.

Further, the scientific literature on the reproductive health of transgender and gender diverse individuals has focused on a small number of topics, especially cervical cancer screening but also pregnancy, fertility preservation, and fertility intentions, desires, and attitudes. In contrast, topics such as contraceptive use and birth have received much less attention, and no study pertained to abortion care among transgender and gender diverse people. In terms of sampling and analytical strategies, the vast majority of studies relied on small, convenience or purposive samples of predominately White, college-educated, and young and midlife adult transgender and gender diverse people. Additionally, among the studies that included both transgender and gender diverse people, very few presented results disaggregated by gender identity, and no study disaggregated their research findings by age, race/ethnicity, or socioeconomic position. Therefore, the existing literature does not address the full range of reproductive health topics relevant to transgender and gender diverse people or accurately reflect the reproductive health concerns and experiences of AMAB people, gender diverse people, Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian/Pacific Islander people, poor or low-income people, or adolescents.

To continue expanding the small but growing scientific literature on the reproductive health of transgender and gender diverse people, researchers should broaden the reproductive health topics and populations included. Specifically, future studies should address the full range of reproductive health issues relevant to transgender and gender diverse people, including contraceptive use, abortion care, and birth. Further, additional reproductive health studies should be conducted among not only AFAB but also AMAB transgender and gender diverse people from across the globe, including the Global South, with data disaggregated by gender identity and other social categories as feasible. Further, studies that adopt longitudinal and probability sampling research approaches are needed to facilitate causal inference, capture reproductive health concerns across the life course, and promote the generalisability of research findings to transgender and gender diverse people overall.Citation33 Of note, existing cross-sectional (e.g. National Survey of Family Growth, Demographic Health Surveys) and longitudinal (e.g. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health) national probability sample surveys that address reproductive health topics should include validated gender identity measures and oversample transgender and gender diverse people.Citation34,Citation35 Additionally, population-based transgender health studies (e.g. TransPOP Study) should collect detailed information on various reproductive health outcomes over time.

To adequately reflect the reproductive health needs, preferences, and experiences of multiply marginalised transgender and gender diverse people – including but not limited to gender diverse people, Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian/Pacific Islander people, adolescents, and poor and low-income individuals – scientific research on the reproductive health of transgender and gender diverse people should be guided by intersectionality. Intersectionality is an analytical framework rooted in Black feminist theory and practice that posits that the lived experiences of individuals and social groups are simultaneously shaped by multiple and mutually constitutive forms of discrimination and oppression, including but not limited to racism, sexism, transphobia and cisgenderism, heterosexism, and classism as linked to White supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism, and capitalism.Citation36–39 Of note, intersectionality suggests that multiply marginalised transgender and gender diverse people have different and unique health needs and experiences from those who occupy privileged social, economic, and political positions.Citation40 Similarly, empirical research has identified disparities in various health and health care outcomes among transgender and gender diverse people by gender identity, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic position, sexual orientation, and age.Citation7,Citation41,Citation42 Health disparities related to nativity, disability, and other social determinants of health are also likely among transgender and gender diverse people,Citation43 although they have not yet been documented in the scientific literature. Thus, research that is guided by intersectionality is urgently needed to promote the reproductive health and rights of all transgender and gender diverse people, including those who are multiply marginalised as a result of not only transphobia and cisgenderism but also racism, classism, heterosexism, age, xenophobia, and ableism, among other dimensions of social stratification and inequality.

Despite the need for probability sample surveys that generate generalisable estimates of reproductive health outcomes among transgender and gender diverse people, quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods research studies that rely on purposive sampling strategies will continue to be necessary to ensure the generation of meaningful research findings for multiply marginalised transgender and gender diverse people. In line with an intersectional approach, researchers can use various purposive sampling strategies, including quota sampling and respondent driven, participant referral, or snowball sampling, to ensure that their reproductive health studies include multiply marginalised transgender and gender diverse populations, who are underrepresented in the general population, in sufficient numbers to generate meaningful results for these subpopulations.Citation44,Citation45 Investigators can also use intersectionality throughout the research process to ensure that their research teams, research questions, and data collection, analysis, and interpretation efforts centre the lived experiences of diverse groups of transgender and gender diverse people at the intersection of multiple forms of social inequality.Citation40,Citation45–47 In particular, future studies should include transgender and gender diverse individuals from diverse social backgrounds on their research teams, measure multiple dimensions of not only social identity (e.g. gender identity, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation) but also discrimination (e.g. transphobia, racism, heterosexism) at both the interpersonal and structural level, analyse study results in relation to multiple dimensions of social identity and inequality, both within and across subpopulations, and interpret research findings in their social and historical context.Citation40,Citation45–47

Intersectionality can also guide researchers not only to generate research findings to increase knowledge but also to develop, test, implement, and disseminate interventions that promote the reproductive health and rights of transgender and gender diverse people using intervention research, implementation science, and community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches. In particular, researchers should develop and test interventions that address barriers to and facilitators of reproductive health among transgender and gender diverse people, including those who are multiply marginalised, at multiple levels of influence, including the individual (e.g. knowledge, risk perceptions), interpersonal (e.g. patient–provider communication), institutional (e.g. gender-affirming procedures and protocols), community (e.g. community norms), and societal (e.g. health and social policies) levels.Citation48 Further, implementation science can help scientists identify and address the factors that influence both the implementation and dissemination of these interventions to ensure that they are tailored to and address the specific and unique needs of transgender and gender diverse people from various social backgrounds and geographic locations.Citation49 Finally, CBPR, which provides a collaborative approach to research that equitably involves community members in all phases of the process to inform action on a given population health issue and its social determinants,Citation50 is particularly well aligned with intersectionality, which seeks to advance social justice by linking both theory and practice and addressing power imbalances.Citation47 Studies that use this collaborative and equitable approach are needed to ensure that research informs programmes, practices, and policies that address the reproductive health needs of transgender and gender diverse people, including those who are multiply marginalised, as they define them for themselves.Citation50

The studies included in our scoping review have important implications for not only research but also practice and policy. Specifically, healthcare providers should receive ongoing training in transgender and gender diverse reproductive health, person-centered care, gender-affirming care, transphobia, cisgenderism, and other forms of bias, stigma and discrimination in health care, structural competence, and shared decision-making in order to facilitate access to and utilisation of high-quality reproductive health care that is inclusive and respectful of transgender and gender diverse people’s lived experiences and reproductive health needs. Further, reproductive healthcare settings can be more welcoming to transgender and gender diverse people by avoiding branding reproductive health as “women’s health care,” ensuring that facilities are visibly inclusive and affirming of transgender and gender diverse people, providing educational materials that are inclusive of transgender and gender diverse individuals, designing intake forms that use gender-affirming language and response options, training all front desk and health care staff to use patients’ correct names and pronouns, and providing patients with opportunities to report (and then addressing) biased, stigmatising, or discriminatory treatment.Citation17,Citation51–53 Additionally, because transgender and gender diverse people may prefer receiving reproductive health care in community settings that are especially tailored to their needs, community-based organisations that serve transgender and gender diverse people should receive the funding, support, and technical assistance they need from state and local health departments and health care institutions to deliver reproductive health services.Citation54

The results and implications of our scoping review should be understood in the context of several limitations. First, our findings only pertain to empirical research studies written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals. As such, they may not be applicable to studies published in other languages and in other formats or venues (e.g. reports, briefs, theses, dissertations, websites), which may differ in important ways from the English-language scientific research literature. Additionally, the results of our scoping review findings only apply to the 2000–2018 period. As such, they may not reflect the scientific literature published before 2000 or after 2018. Therefore, future scoping reviews pertaining to transgender and gender diverse people’s reproductive health should seek to include studies written in languages other than English, include both the scientific and grey literature, and consider a longer time period, as feasible given available resources.

The existing scientific literature represents an important first step in describing the reproductive health of transgender and gender diverse people. However, our scoping review shows that this literature is limited in terms of geographic regions represented, reproductive health topics addressed, methods used, and populations included. As a result, existing scientific research does not reflect the full range of reproductive health issues that are relevant to transgender and gender diverse people and may not be generalisable to those who are multiply marginalised or living in the Global South. Moreover, research that uses an intersectional approach is needed to promote our understanding of how multiple forms of social inequality influence the reproductive health of transgender and gender diverse people from various social backgrounds, both within and across subpopulations defined in relation to race/ethnicity, gender identity, socioeconomic position, age, nativity and disability, among other social categories. Lastly, investigators should conduct studies that use intervention research, implementation science, and CBPR approaches to develop, test, implement, and disseminate programmes, practices, and policies that collaboratively address transgender and gender diverse people’s reproductive health concerns as they define them for themselves. Together, these efforts will help ensure that the reproductive health and rights of all transgender and gender diverse people are understood and addressed with dignity and respect.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- United Nations (UN), Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2017). Reproductive health policies 2017: data booklet (ST/ESA/ SER.A/396). [cited 2020 May 15]. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/policy/reproductive_health_policies_2017_data_booklet.pdf.

- Spielberg LA. Reproductive health part 1: introduction to reproductive health & safe motherhood. Global health education consortium and collaborating partners. Dartmouth Medical School; 2007.

- Inter-Agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises. (2010). Inter-agency field manual on reproductive health in humanitarian settings: 2010 revision for field review. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305149/.

- Espey E, Dennis A, Landy U. The importance of access to comprehensive reproductive health care, including abortion: a statement from women’s health professional organizations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):67–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.008.

- Hoffkling A, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius J. From erasure to opportunity: a qualitative study of the experiences of transgender men around pregnancy and recommendations for providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(2):332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1491-5.

- James-Abra S, Tarasoff LA, Green D, et al. Trans people’s experiences with assisted reproduction services: a qualitative study. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(6):1365–1374. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev087.

- Grant J, Mottet L, Tanis J, et al. Injustice at every turn: a report of the national transgender discrimination survey. National Center for Transgender Equality, National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011. Available from: http://www.ncgs.org/research/database/injustice-at-every-turn-a-report-of-the-national-transgender-discrimination-survey/

- Nixon L. (2013). The right to (trans) parent: a reproductive justice approach to reproductive rights, fertility, and family-building issues facing transgender people, 20 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 73. Available from: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol20/iss1/5.

- Poteat T, German D, Kerrigan D. Managing uncertainty: a grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84(1):22–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019.

- Dutton L, Koenig K, Fennie K. Gynecologic care of the female-to-male transgender man. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2008;53(4):331–337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.02.003.

- Agénor M, Peitzmeier SM, Bernstein IM, et al. Perceptions of cervical cancer risk and screening among transmasculine individuals: patient and provider perspectives. Cult Health Sex. 2016;18(10):1192–1206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2016.1177203.

- Ellis SA, Wojnar DM, Pettinato M. Conception, pregnancy, and birth experiences of male and gender variant gestational parents: it’s how we could have a family. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2015;60(1):62–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12213.

- Light AD, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius JM, et al. Transgender men who experienced pregnancy after female-to-male gender transitioning. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1120–1127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000540.

- Obedin-Maliver J, Makadon HJ. Transgender men and pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016;9(1):4–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1753495X15612658.

- Agénor M, Cottrill AA, Kay E, et al. Contraceptive beliefs, decision making and care experiences among transmasculine young adults: a qualitative analysis. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;52(1):7–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1363/psrh.12128.

- Krempasky C, Harris M, Abern L, et al. Contraception across the transmasculine spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(2):134–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.07.043.

- Klein DA, Berry-Bibee EN, Keglovitz Baker K, et al. Providing quality family planning services to LGBTQIA individuals: a systematic review. Contraception. 2018;97(5):378–391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2017.12.016.

- Peitzmeier SM, Khullar K, Reisner SL, et al. Pap test use is lower among female-to-male patients than non-transgender women. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(6):808–812. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.031.

- Charter R, Ussher JM, Perz J, et al. The transgender parent: experiences and constructions of pregnancy and parenthood for transgender men in Australia. Int J Transgenderism. 2018;19(1):64–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1399496.

- Wierckx K, Van Caenegem E, Pennings G, et al. Reproductive wish in transsexual men. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(2):483–487. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/der406.

- Tornello SL, Bos H. Parenting intentions among transgender individuals. LGBT Health. 2017;4(2):115–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2016.0153.

- Armuand G, Dhejne C, Olofsson JI, et al. Transgender men’s experiences of fertility preservation: a qualitative study. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(2):383–390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew323.

- Auer MK, Fuss J, Nieder TO, et al. Desire to have children among transgender people in Germany: a cross-sectional multi-center study. J Sex Med. 2018;15(5):757–767. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.03.083.

- De Sutter P, Verschoor A, Hotimsky A, et al. The desire to have children and the preservation of fertility in transsexual women: a survey. Int J Transgenderism. 2002;6(3). [cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://cdn.atria.nl/ezines/web/IJT/97-03/numbers/symposion/index-2.htm.

- Jones CA, Reiter L, Greenblatt E. Fertility preservation in transgender patients. Int J Transgenderism. 2016;17(2):76–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1153992.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci: IS. 2010;5(69). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013.

- Covidence. (2020). About. [cited 2020 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.covidence.org/about-us/.

- Porsch LM, Dayananda I, Dean G. An exploratory study of transgender New Yorkers’ use of sexual health services and interest in receiving services at planned parenthood of New York city. Transgender Health. 2016;1(1):231–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2016.0032.

- Seay J, Ranck A, Weiss R, et al. Understanding transgender men’s experiences with and preferences for cervical cancer screening: a rapid assessment survey. LGBT Health. 2017;4(4):304–309. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2016.0143.

- Peitzmeier SM, Agénor M, Bernstein IM, et al. “It can promote an existential crisis”: factors influencing pap test acceptability and utilization among transmasculine individuals. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(14):2138–2149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317725513.

- Aschengrau A, Seage GR. Essentials of epidemiology in public health. Burlington (MA): Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2014.

- Deutsch MB, Buchholz D. Electronic health records and transgender patients – practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):843–847. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3148-7.

- Reisner SL, Conron KJ, Tardiff LA, et al. Monitoring the health of transgender and other gender minority populations: validity of natal sex and gender identity survey items in a U.S. national cohort of young adults. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1224.

- Combahee River Collective. (1977). The Combahee river collective statement. [cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://americanstudies.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Keyword%20Coalition_Readings.pdf.

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum. 1989;1989, Article 8. [cited 2020 Dec 16]. Available from: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

- Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43(6):1241–1299. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

- Hill Collins P, Bilge S. Intersectionality. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley; 2016.

- Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality – an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–1273. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750.

- Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Guzman R, et al. HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, health care use, and mental health status of transgender persons: implications for public health intervention. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):915–921. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.6.915.

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, et al. The report of the 2015 US transgender survey. Washington (DC): National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. [cited 2020 Apr]. Available from: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf.

- Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social determinants of health discussion paper 2 (policy and practice). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [cited 2020 Dec16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/corner/SDHDP2.pdf?ua=1.

- Henderson ER, Blosnich JR, Herman JL, et al. Considerations on sampling in transgender health disparities research. LGBT Health. 2019;6(6):267–270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2019.0069.

- Abrams JA, Tabaac A, Jung S, et al. Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Soc Sci Med. 2020;258: 113138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113138.

- Bowleg L, Bauer GR. Invited reflection: quantifying intersectionality. Psychol Women Q. 2016;40(3):337–341.

- Agénor M. Future directions for incorporating intersectionality into quantitative population health research. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(6):803–806. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305610.

- Paskett E, Thompson B, Ammerman AS, et al. Multilevel interventions to address health disparities show promise in improving population health. Health Aff. 2016;35(8):1429–1434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1360.

- Lobb R, Colditz GA. Implementation science and its application to population health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:235–251.

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: advancing social and health equity. 3rd ed. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2018. p. 31–44.

- Cook SC, Gunter KE, Lopez FY. Establishing effective health care partnerships with sexual and gender minority patients: recommendations for obstetrician gynecologists. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35(5):397–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1604464.

- Keuroghlian AS, Ard KL, Makadon HJ. Advancing health equity for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people through sexual health education and LGBT-affirming health care environments. Sex Health. 2017;14(1):119–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1071/SH16145.

- Kattari SK, Brittain DR, Markus AR, et al. Expanding women’s health practitioners’ and researchers’ understanding of transgender/nonbinary health issues. Women’s Health Issues. 2020;30(1):3–6.

- Seelman KL, Poteat T. Strategies used by transmasculine and non-binary adults assigned female at birth to resist transgender stigma in healthcare. Int J Transgender Health. 2020;21:350–365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1781017.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Appendices

Appendix A. Search strategy

Search for Ovid MEDLINE®

Searches for additional databases available upon request ([email protected])

(trans$gender* or trans$sex* or trans$women or trans$woman or trans$men or trans$man or trans$feminine or trans$masculine or trans$person* or trans$girl or trans$boy or trans$girls or trans$boys or transex* or trans$spectrum).mp.

(koti or hijra or mahuvahine or mahu or waria or katoey or bantut or nadleehi or berdache or xanith).mp.

(two spirit* or third gender* or third sex or gender variant* or gender queer or blended spirit or non$binary or gender diverse or sex* divers* or gender expansive or gender cross* or cross gender or gender incongruen* or gender dysphor*).mp.

(male-to-female and MtF).mp.

(female-to-male and FtM).mp.

(gender adj3 non$conform*).mp.

exp transgender persons/ or exp health services for transgender persons/ or exp transsexualism/ or exp gender dysphoria/

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7

exp Reproductive Health Services/ or exp Reproductive Health/ or exp Women’s Health/ or exp Reproductive Rights/ or exp Fertility Preservation/ or exp Reproductive Techniques/ or exp Infertility/ or exp Fertility/ or exp Genital Neoplasms, Female/

exp oocyte retrieval/ or exp embryo transfer/ or exp ovulation induction/ or exp cryopreservation/ or exp Semen preservation/

exp Fertilization in Vitro/ or exp Pregnancy/ or exp Pregnancy Outcome/ or exp Pregnancy Complications/

(reproductive health or reproductive service* or women’s health or women’s service* or women’s care or gynecologic care).mp.

(fertil* or contraception* or abort* or pregnan* or family plan* or assisted reproduction or IVF or surrog* or prenatal care or postnatal care or preconception care or delivery or miscarr* or egg* freez* or sperm freez* or egg preserv* or sperm preserv* or in vitro fertilization or cytopreserv* or uterine transplant*).mp.

((endomet* or cervical or uterus or uterine or gynecolog*) and (cancer* or neoplasm* or carinoma*)).mp.

9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14

8 and 15

limit 16 to english language

limit 17 to yr=“2000 – Current”

limit 18 to (case reports or comment or editorial or letter)

18 not 19

exp animals/

exp animals/ and exp humans/

21 not 22

20 not 23