Abstract

Access to abortion throughout much of Mexico has been restricted. Fondo Maria is an abortion accompaniment fund that provides informational, logistical, financial, and emotional support to people seeking abortion care in Mexico. This cross-sectional study examines the factors that influenced decision-making and contributed to delays in accessing care and explores experiences with Fondo Maria’s support among women living outside Mexico City (CDMX). We describe and compare the experiences of women across the sample (n = 103) who were either supported by Fondo Maria to travel to CDMX to obtain an abortion (n = 60), or self-managed a medical abortion in their home state (n = 43). Data were collected between January 2017 and July 2018. Seventy-seven percent of participants reported that it was difficult to access abortion care in their home state and 34% of participants indicated they were delayed in accessing care, primarily due to a lack of financial support. The majority of participants (58%) who travelled to CDMX for their abortion did so because it seemed safer. The money/cost of the trip was the most commonly cited reason (33%) why participants who self-managed stayed in their home state. Eighty-seven percent of participants said Fondo Maria’s services met or exceeded their expectations. Our data suggest that people seeking abortion and living outside CDMX face multiple and overlapping barriers that can delay care-seeking and influence decision-making. Abortion accompaniment networks, such as Fondo Maria, offer a well-received model of support for people seeking abortion in restrictive states across Mexico.

Résumé

L’accès à l’avortement dans une grande partie du Mexique est retreint. Fondo MARIA est un fonds d’accompagnement de l’avortement qui prodigue un soutien informatif, logistique, financier et psychologique aux personnes souhaitant interrompre une grossesse au Mexique. Cette étude transversale examine les facteurs qui ont influencé la prise de décision et contribué à des retards dans l’accès aux soins, et elle explore l’expérience du soutien de Fondo MARIA chez des femmes vivant hors de l’agglomération de Mexico. Nous décrivons et comparons les expériences des femmes dans l’échantillon (n = 103) qui ont été soutenues par Fondo MARIA pour se rendre à Mexico afin d’y avorter (n = 60) ou qui ont pris en charge elles-mêmes un avortement médicamenteux dans leur État de résidence (n = 43). Les données ont été recueillies de janvier 2017 à juillet 2018. Soixante-dix-sept pour cent des participantes ont indiqué qu’il était difficile d’avoir accès à un avortement dans leur État de résidence et 34% des participantes ont fait état de retards dans l’accès aux soins, principalement en raison d’un manque de soutien financier. La majorité des participantes (58%) qui se sont rendues à Mexico pour y avorter l’ont fait car cela semblait plus sûr. L’argent/le coût du voyage était la raison la plus fréquemment citée (33%) pour laquelle les participantes qui ont pris en charge elles-mêmes leur avortement sont restées dans leur État de résidence. Quatre-vingt-sept pour cent des participantes ont affirmé que les services de Fondo MARIA correspondaient à leurs attentes ou les dépassaient. À en juger par nos données, les personnes souhaitant avorter et vivant en dehors de Mexico font face à un ensemble d’obstacles multiples et imbriqués qui peuvent retarder la demande de soins et influencer la prise de décision. Les réseaux d’accompagnement de l’avortement, comme Fondo MARIA, offrent un modèle de soutien bien accepté pour les personnes souhaitant interrompre leur grossesse dans des États restrictifs du Mexique.

Resumen

En gran parte de México, se ha restringido el acceso a los servicios de aborto. El Fondo MARIA es un fondo de acompañamiento durante el aborto que brinda apoyo informativo, logístico, financiero y emocional a las personas que buscan servicios de aborto en México. Este estudio transversal examina los factores que influyeron en la toma de decisiones y contribuyeron a retrasos en acceder a los servicios, y explora las experiencias de mujeres que viven fuera de la Ciudad de México (CDMX) con el apoyo brindado por el Fondo MARIA. Describimos y comparamos las experiencias de las mujeres en la muestra (n = 103) que fueron apoyadas por el Fondo MARIA para viajar a CDMX para obtener un aborto (n = 60) o que autogestionaron un aborto con medicamentos en su estado de residencia (n = 43). Se recolectaron datos entre enero de 2017 y julio de 2018. El 77% de las participantes informaron que les resultó difícil acceder a servicios de aborto en su estado de residencia y el 34% de las participantes indicaron que tuvieron retrasos para acceder a los servicios, principalmente por falta de apoyo financiero. La mayoría de las participantes (58%) que viajaron a CDMX para tener un aborto lo hicieron porque les pareció ser más seguro. El dinero/gasto del viaje fue la razón más citada (33%) por la cual las participantes que autogestionaron el aborto permanecieron en su estado de residencia. El 87% de las participantes dijeron que los servicios del Fondo MARIA cumplieron o superaron sus expectativas. Nuestros datos indican que las personas que buscan servicios de aborto y viven fuera de CDMX enfrentan barreras múltiples y coincidentes que pueden retrasar la búsqueda de servicios e influir en la toma de decisiones. Las redes de acompañamiento durante el aborto, tales como el Fondo MARIA, ofrecen un modelo de apoyo bien recibido para las personas que buscan servicios de aborto en estados restrictivos en todo México.

Introduction

In April 2007, lawmakers in Mexico City (CDMX) passed legislation that decriminalised abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy within the jurisdiction.Citation1 Recently, legislators in Oaxaca and Hidalgo and the Supreme Court of Mexico voted to decriminalise abortion, but substantial obstacles to implementation remain.Citation2,Citation3 Prior to these legal changes, abortion was highly restricted outside of CDMX.Citation2 In 2018, rape was the only circumstance for which abortion was legal in all 31 states outside of CDMX.Citation4,Citation5 Twenty-three states allowed abortion when the life of a womanFootnote* was at risk, 15 in the case of severe fetal malformations, and 15 when the health of the woman was at risk.Citation4,Citation5 Even when women living outside of CDMX have pregnancies that fall under the legal circumstances permitting abortion in their state, they may be unable to access a legal abortion locally due to a lack of information, restrictive legal interpretations, a lack of willing providers, and a limited history of affirming jurisprudence.Citation6

As such, people in Mexico, particularly those who live outside of CDMX, continue to face a number of barriers that limit their access to abortion services. Barriers include the financial and logistical burdens of travelling to CDMX, which have the greatest impact on women with less formal education, unmarried women, and women who live further from the capital.Citation7 Abortion stigma, which contributes to and perpetuates a culture of silence around abortion, may also act as a barrier to care.Citation3–5 In Mexico specifically, research has documented widespread stigmatising attitudes towards abortion irrespective of legality.Citation8,Citation9 Research has also identified partner or family member opposition as a barrier to obtaining care, particularly for those living outside of CDMX, where stigmatising attitudes appear to be more prevalent.Citation7,Citation10

In this context, services that are person-centred, support self-care, empower people to make autonomous decisions, and offer practical support to help people overcome barriers, may improve access to safe, high-quality abortion inside or outside of the formal sector.Citation11 In Mexico, as well as in other restrictive contexts globally, community-oriented feminist organisations committed to defending and promoting sexual and reproductive rights have pioneered offering such services, using a model of abortion support referred to as abortion accompaniment.Citation12,Citation13 Using the accompaniment model, these organisations provide support and evidence-based information, and often help people to safely access and use medications for abortion outside of the formal health sector.Citation12,Citation14 Accompaniment organisations differ in the methods they use to connect with people seeking abortions (phone, text, in-person) and the types of support they provide (e.g. financial, logistical, emotional, etc.), but they share the common goals of decreasing barriers to safe abortion services, empowering individuals with the information and support they need to make informed decisions, and ultimately realising their choices.

The MARIA Abortion Fund for Social Justice (Fondo Maria) is an abortion accompaniment fund operated by Balance, an organisation based in CDMX dedicated to promoting and defending the reproductive and sexual rights of women and young people.Citation15 Using an “accompany to empower” model, Fondo Maria provides callers with detailed information about their options to travel to CDMX and seek abortion services in a clinic or obtain medications for abortion and self-manage an abortion in their home state, and supports them in making the decision that is best for them. That said, in accordance with clinical guidelines,Citation16 callers beyond 10 weeks of pregnancy are only offered the option to travel to CDMX. Once callers have made a decision, Fondo Maria supports them to make plans to travel or self-manage. They offer those who travel the option of being accompanied to the abortion clinic in CDMX and provide those who stay in their home state with the option to receive support and information over the phone or via text-message throughout the medical abortion process. To the extent possible, Fondo Maria also offers financial support based on the specific needs of their caller, which may include support to cover the costs of the procedure, travel, medications, accommodations, and food. Between May 2009 and May 2020, Fondo Maria helped over 10,500 people in Mexico access abortion services.

Evidence has suggested that the increased use of medications for abortion in contexts where abortion is legally restricted has lowered the incidence of unsafe abortionCitation17 and preliminary findings suggest that abortion accompaniment networks may increase access to safe abortion care in restrictive contexts and improve women’s abortion experiences, increasing their feelings of support and giving them a sense of control over the process.Citation12,Citation13,Citation18–22 Control over the abortion decision and process is a key component of reproductive autonomy, which has been linked to women’s empowerment and wellbeing, and is a foundational component of self-care interventions.Citation11,Citation23 Previous research has explored the foundations, orientations, and potential of accompaniment networks and similar models, documented the experiences of accompaniers, and provided a general profile of users.Citation12,Citation14,Citation18,Citation21,Citation21,Citation24–27 However, little is known about the abortion-seeking experiences of people living outside of CDMX who obtained abortions with the support of an accompaniment network. In this study, we explored the contexts in which women sought abortions, the factors that influenced decision-making and contributed to delays in accessing care, and the experiences women had with Fondo Maria. By exploring these factors, this analysis aims to improve our understanding of the types of obstacles people from outside CDMX face when seeking abortions and the role abortion accompaniment may play in addressing barriers and supporting people from restrictive contexts seeking abortion in Mexico.

Methods

The cross-sectional analysis presented in this article draws on data from a broader six-month longitudinal study of abortion experiences in Mexico. In the context of an existing partnership, staff at Fondo Maria and Ibis Reproductive Health collaboratively designed and executed the study. Analyses were conducted by the co-authors from Ibis Reproductive Health and shared and interpreted with the co-authors from Fondo Maria.

Women who contacted Fondo Maria for abortion accompaniment support and consented to participate in the study were enrolled between January and December of 2017. We surveyed participants before they received accompaniment support and obtained an abortion, one month after their abortion (midline), and six months after their abortion (endline). In this paper, we descriptively analyse women’s self-reported experiences accessing abortion care and receiving support from Fondo Maria using data collected primarily at midline. We focus on the midline given that the majority of the variables presented in this paper were only collected at this time point.

Study procedures, recruitment, and ethics

Participants were eligible for inclusion in this study if they were over 18 years of age, could provide informed consent, resided outside of CDMXFootnote†, were in the first trimester of pregnancy, and sought abortion care with the support of Fondo Maria. Fondo Maria counsellors provided study information to all callers when they first contacted the hotline. Callers who expressed interest in participating were transferred to a study administrator before receiving accompaniment support. The study administrator described the study, answered questions, obtained informed consent to both collect baseline data (including sociodemographic data routinely collected by Fondo Maria staff) and contact participants to complete follow-up surveys one and six months after the baseline survey. The study administrator completed the consent process and administered the baseline survey via telephone and the caller was reconnected with a counsellor to receive accompaniment support. Because the baseline survey was administered before participants received accompaniment support, women had not yet made the decision to travel to CDMX or stay in their home state at the time that they completed the baseline survey. Thus, participants were categorised as having either travelled to seek an abortion at one of seven clinics in CDMX with the support of Fondo Maria (FM Clinic) or having been supported by Fondo Maria to self-manage a medical abortion in their home state (FM State), based on records kept by Fondo Maria staff which were linked to surveys through the participant’s study ID prior to the administration of the midline survey.

Study administrators sent participants links to complete follow-up surveys on Qualtrics at midline and endline via their preferred follow-up method (text, email, or WhatsApp) and sent up to three reminders to complete each survey. Participants were compensated with $50 pesos in cell-phone credit or cash for each survey they completed. This study was approved by Allendale Investigational Review Board in October of 2016 (Study: IBISCA 102016) and the research was conducted in accordance with national and local guidelines and regulatory procedures in Mexico. We did not seek ethical approval from a Mexican IRB due to concerns about potential negative consequences for Fondo Maria’s work outside of CDMX.

Measures

The instrument utilised for this study, including the specific questions and response options offered, was developed based on a pilot study conducted with Fondo Maria. The instrument also drew from other studies that focused on abortion travel,Citation28 stigma,Citation29,Citation30, and delays.Citation31 Most questions presented in this analysis were multiple response options and some, as noted below, included an “Other” option with a space for participants to write in a response.

Sociodemographic data were collected at baseline, but sociodemographic results are only presented for those participants who completed the midline survey, as this is the timepoint that we draw all remaining data from for this analysis. Sociodemographic data included age, parity, employment status, income, education level, marital and relationship status at the time of pregnancy, religious affiliation, prior abortion, and gestational age at the time of recruitment. We categorised participants as either living above or below the urban poverty line, as defined by El Consejo Nacional de Evaluacion de la Politica de Desarrollo Social,Citation32 by calculating each participant’s maximum per person household income. This measure was calculated by dividing the highest number in the income range participants selected as representing their monthly income by the number of people they reported were living in their household.

We asked a series of questions to understand the context in which participants sought abortion care and the factors that influenced their decisions and experiences. Participants were asked to rate on a Likert scale how difficult they perceived it was to access abortion in their home state; to share whether they got an abortion as early as they wanted to, and why, if applicable, they were delayed; to select their primary reason for travelling to CDMX (FM Clinic) or staying at home for their abortion (FM State); and in the case of FM Clinic, to rate how difficult their travel to CDMX was and provide details on why, if applicable, it was difficult.

To examine experiences with Fondo Maria’s services, we asked participants to rate the support they received from Fondo Maria (on a scale from 1-10), to share how easy or difficult it was to contact Fondo Maria (Likert scale), whether they felt like the accompanier gave them clear information (yes or no), and whether they felt the services they received from Fondo Maria met, exceeded, or did not meet their expectations. FM Clinic participants were also asked whether they felt emotionally supported by Fondo Maria.

Analysis

One hundred and three participants completed the midline survey. Midline participants represent 64% (103 out of 162) of all of those who completed the baseline survey (75% of the baseline FM Clinic group and 53% of the baseline FM State group, χ2 test, p = .001). The distribution of sociodemographic characteristics at midline was, for the most part, not statistically significantly different from the distribution of the full sample surveyed at baseline, with the exception of age and education level. Those with higher levels of education were more likely to be retained at midline compared to those with lower education levels and those aged 30–34 had lower levels of retention in the study at midline.

We present the distribution of responses for these measures across the full sample and by FM Clinic and FM State groups. We tested whether there were statistically significant sociodemographic differences between groups (FM State & FM Clinic) and statistically significant differences in difficulty accessing abortion care, and delays by group (FM State & FM Clinic) or sociodemographic characteristics using Chi-squared tests and Fisher exact tests with an alpha level of p ≤ .05. Due to small sample sizes, we found few statistically significant differences among the groups. However, we highlight where we saw substantive descriptive differences in experiences by group, as these could be illustrative of notable differences, even in the absence of statistical significance. We also stratified delays to care by sociodemographic characteristics in order to identify whether specific characteristics were associated with being delayed. Analysis was carried out using Stata 15 SE (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas) and R statistical software (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Sociodemographics

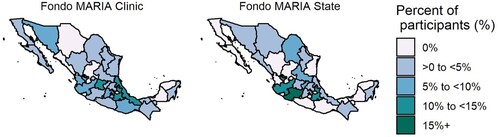

This analysis includes data from 103 Fondo Maria callers who completed the midline survey, including 60 participants who travelled from their home states to CDMX for abortion care (FM Clinic group) and 43 participants who self-managed a medical abortion in their home state (FM State group). The majority of participants were between 18 and 24 years old (61%), were single (72%), did not have children (65%), and had never had an abortion prior to participating in the study (81%) (). Seventy-three percent of participants were working at the time they were surveyed, 59% had some tertiary education or more, and 68% had a household income that classified them as living above the urban federal poverty level in Mexico. The greatest proportion of participants identified as Catholic (48%). shows the state of residence of participants in each group. The majority of participants in the FM clinic group lived in Puebla, Veracruz, and Guanajuato. The majority of participants in the FM State Group resided in Michoacán, Jalisco, and Puebla. Only 6% of participants had previously contacted Fondo Maria for abortion accompaniment services. With the exception of gestational age at the time of recruitment, no sociodemographic characteristics were statistically significantly different between the FM Clinic and FM State groups.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics

Difficulty accessing abortion and factors influencing decision-making

The majority of participants indicated that they perceived services to be either very difficult (55%) or somewhat difficult (22%) to access (). The FM Clinic group had a significantly higher proportion of participants who believed abortion care was very difficult to access compared to the FM State group (68% vs. 37%, p = .006).

Table 2. Participants’ perceived difficulty accessing abortion in home state

A majority of FM Clinic participants reported travelling to CDMX for an abortion because they thought it was safer (58%; n = 36) (). Other reasons FM Clinic participants travelled to CDMX were because they wanted to obtain a legal abortion (13%; n = 8), because they did not have confidence in the medication (13%; n = 8), or because they did not know medications could be used (3%: n = 2). Thirty-seven percent (n = 22) of participants in the FM Clinic group reported that it was somewhat or very difficult to make the trip, with 55% of those who said they had difficulty citing the cost associated with travel (data not shown). Worrying that others would find out (18%; n = 4) or finding the time for the trip (17%; n = 4) were other reasons participants found the trip difficult (data not shown).

Table 3. Participants’ reasons for selecting travel to CDMX or self-administration/staying in their home state

Participants in the FM State group reported making the decision to stay at home because of financial reasons or the cost of the trip to CDMX (33%; n = 14), not having the time or ability to take time off from work to travel (23%; n = 10), or worrying that someone would find out (14%; n = 6). Notably, 19% (n = 8) of participants who had an abortion in their state of residence indicated that they did so because they preferred to have an abortion at home ().

Delays and actors influencing delays

Thirty-four percent (n = 35) of all participants indicated that they would have preferred to have had an abortion earlier in their pregnancy. The FM Clinic group had a higher proportion of participants who indicated they would have preferred to have obtained the abortion earlier compared to the FM State group (39%; n = 23 vs, 28%; n = 12), although these differences were not statistically significant. We did find significant differences in the proportion of participants who indicated they were delayed by gestational age categories (p = 0.003). Eighty-nine percent of participants (all FM Clinic) who had pregnancies at 11–12 weeks of gestation when they contacted Fondo Maria indicated that they would have preferred to have obtained their abortion earlier, compared to 35% of those 7–10 weeks of gestation, and 15% of those who called at 1–6 weeks of gestation.

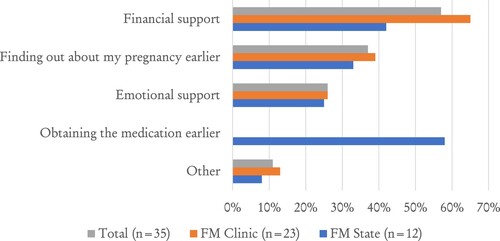

Across both groups, those who said they would have preferred to obtain an abortion earlier indicated that financial support (57%; n = 20), emotional support (26%; n = 9), discovering their pregnancy sooner (37%; n = 13), and/or something else (11%; n = 4) would have helped them obtain the care they wanted earlier (). Fifty-eight percent (n = 7) of FM State participants who would have preferred to obtain an abortion earlier indicated that obtaining the medication sooner would have helped them have an abortion earlier.

Experiences with Fondo Maria

Eighty-seven percent (87%; n = 52) of FM Clinic and 89% (n = 38) of FM State participants reported that the services they received from Fondo Maria exceeded or met their expectations, and the remaining participants reported that Fondo Maria could not have met or exceeded their expectations because they had not known what to expect. Across the sample, most participants said it was very easy (56%; n = 58) or somewhat easy (36%; n = 36) to contact Fondo Maria for support (). Ninety-three percent of FM Clinic (n = 56) and 91% of FM State participants (n = 39) felt that the Fondo Maria accompanier gave them all the information they needed in a clear way. On a scale from 1 to 10, participants rated the support they received from Fondo Maria at 9.8 on average, with 88% (n = 91) of participants rating the support to be very good (i.e. a 10). Eighty-eight percent (n = 53) of FM Clinic participants felt that the accompanier supported them emotionally.

Table 4. Participant experiences with Fondo MARIA’s services

Discussion

This analysis provides insight into the contexts in which women sought abortion, the factors that influenced decision-making and delays, and experiences with the abortion accompaniment model of care among women living in restrictive abortion settings in Mexico. The majority of women in this study perceived abortion to be very difficult to access in their home state and their experiences and choices were influenced by costs associated with obtaining abortion, a lack of time, perceptions about the safety of medical abortion outside of the clinic setting, and worries about disclosure. Participants had positive experiences with Fondo Maria, adding to the existing evidence that abortion accompaniment is a well-received model of support for people seeking care in contexts with limited availability of legal abortion services.Citation18,Citation26,Citation33,Citation34

The factors that women cited as influencing their choices, contributing to delays, and shaping their experiences with travel demonstrate the types of obstacles that women living outside of CDMX face to obtaining abortion care. In exploring these factors, it is important to note that we collected data on factors influencing decisions and delays at the midline survey only, one month after participants had their abortion. We did not ask questions about how Fondo Maria’s support may have shifted participants’ experiences and calculations or how it may have helped participants overcome barriers to care. As such, it is challenging to tease apart whether the barriers that emerged in the data represent participants’ baseline needs, or obstacles that remained even with Fondo Maria’s accompaniment support. That said, regardless of whether they represent baseline needs or persistent obstacles, these barriers provide important insights into the environment people outside of CDMX navigate to seek abortion care. These insights will be instructive for accompaniment networks and other organisations who seek to offer services and design interventions to increase access to options for safe abortion in Mexico.

The costs associated with travelling emerged as a primary barrier for participants. Even with the support of Fondo Maria, the financial burden of travelling made the trip difficult for some who travelled. For those who self-managed, cost also factored into their decision to stay in their home state and self-induce an abortion. While Fondo Maria endeavours to offer financial support to all who need it, expenses participants incur may go beyond what Fondo Maria can offer, or could include costs Fondo Maria does not cover, like lost wages and childcare. These findings add to research conducted in other contexts that have shown that the costs associated with travelling to seek a legal abortion are burdensome and can act as a considerable barrier to accessing wanted care.Citation35–40 They also highlight the importance of making additional investments into accompaniment organisations to enable them to provide more financial support or remote support when travel costs remain a barrier. That said, a majority of participants who did not get an abortion as early as they wanted to, reported that financial support would have helped them obtain care earlier. This support may have been particularly critical for people past 10 weeks of gestation who had to travel to CDMX for their abortion as many of these participants reported delays in accessing care and likely presented for care very close to the legal limit. Given that all participants received their abortion shortly after taking the baseline survey, this data point likely reflects participants’ levels of financial support prior to working with Fondo Maria, showing that, despite the financial barriers, all participants were ultimately able to get the care they wanted with the support of Fondo Maria. Future research could explore the extent to which Fondo Maria’s financial support enables people to access abortion services which they might otherwise find to be inaccessible and/or explore how to further reduce delays, which may be particularly important for those who wish to travel to CDMX and risk presenting past the legal limit.Citation41

A number of participants made choices about their abortion experience based on concerns about the relative safety and effectiveness of clinic-based care compared to self-management. Approximately 75% of the participants who travelled to CDMX for their abortion did so primarily because they thought it was safer, or because they did not know how to use the medications or did not trust that the medications would work. These findings may indicate that, though some people might have a preference for one procedure or another for personal reasons, fears or scepticism about the safety and effectiveness of medical abortion broadly, and self-management specifically, may persist despite Fondo Maria’s efforts to provide clear and accurate information to people seeking an abortion.Citation21,Citation24,Citation25,Citation42–45 These data align with findings from recently published qualitative studies of women seeking abortion care in Mexico,Citation46,Citation47 which have documented that the legality associated with clinic-based abortion care may make it feel safer for participants from both a clinical and legal standpoint. It is critical for people to have improved information about and access to all forms of care, but broader dissemination of reliable and accurate information about medical abortion by organisations like Fondo Maria may enable more people to make fully informed choices based on individual preference and circumstance. This could potentially allow people to circumvent other barriers like cost and time associated with travel if self-management is right for them. Reliable information about and access to home-based self-care may be particularly important given the recent restrictions imposed on movement and a potential preference to avoid travel during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.Citation48

Our findings also highlight the role fear of disclosure and a desire for secrecy can play in influencing women’s decision-making processes and delaying access to care, particularly among women in the FM State group. Preferring to have an abortion at home was the third most commonly cited reason for self-managing an abortion at home, followed by being worried someone would find out. For some in the FM Clinic group, this fear made travelling to CDMX more burdensome. These worries may be linked to abortion stigma, which, in addition to creating barriers to care, may influence the decisions people make about their pregnancies and abortions including whether they carry an unwanted pregnancy to term, what methods they use to terminate their pregnancy, and who they tell and rely on for support.Citation49–51 Previous evidence has found that the desire for privacy, comfort, and autonomy motivates people to self-manage their abortion.Citation52–54

Taken together, our results point to the barriers that remain for people seeking abortion care in Mexico, even with the support of organisations like Fondo Maria. Recent judicial and legislative shifts suggest that more widespread access to abortion care may be on the horizon, but issues related to provider/facility objection and bringing national and state-wide laws into alignment raise questions about how sweeping this shift will be.Citation3 In the meantime, a need for the type of services Fondo Maria provides persists and as legislators and activists work to translate the decriminalisation of abortion in the first trimester into practice, particular attention must be paid to building a coordinated ecosystem in which laws, policies, organisations, and communities support people in seeking and obtaining abortion care and decreasing barriers to care. Such an ecosystem must support people to access the type of care they want – whether that is a clinic or self-managed at home. Organisations, advocates, and policymakers should look to organisations like Fondo Maria who have prioritiesd supportive feminist principles in accompanying people to seek abortion.

Our sample was comprised primarily of young women, who were predominately single, did not have children, and had relatively high educational attainment and socioeconomic status. A recent comparative analysis of women who sought abortions in CMDX found that those who had travelled to CDMX from outside the city were better educated on average than both CDMX locals who sought services and residents of their own communities.Citation55 Additional evidence shows that those travelling to CDMX for legal abortion services travelled from less marginalised municipalities.Citation56 When compared to the sample of travellers presented in this paper and overall statistics on women seeking abortions in Mexico, our participants appeared to have even higher educational attainment, and a larger proportion was single and nulliparous.Citation55,Citation57 These sociodemographic findings suggest that those who call Fondo Maria for support may have more access to information, time, and resources than other people seeking abortion in Mexico. It is thus possible that the types of barriers encountered by women in our sample may have an even greater impact on women who do not access Fondo Maria’s services. In light of these findings, Fondo Maria and other accompaniment networks may want to explore strategies to increase awareness about the services they offer to reach a wider range of people in Mexico, some of whom may be in the greatest need of their support.

Participants from our study rated the services they received from Fondo Maria highly, reported that the network was easy to contact, and felt that the information they were provided was clear. FM Clinic participants also felt emotionally supported by their accompanier. It is important to note that reports of positive experiences are not necessarily unique in the context of abortion services in Mexico or among abortion clients broadly.Citation58–60 Additionally, prior research has noted the limitations of commonly used measures of satisfaction, positing that high levels of satisfaction among abortion clients may be more linked to the achievement of the desired outcome of pregnancy terminationCitation60–62 rather than an evaluation of the service provision. That said, as part of our larger study, we recruited a sub-sample of participants who travelled to CDMX without Fondo Maria’s support (data for this group is not included in this analysis), and participants from this group reported that greater emotional support may have helped them obtain abortion care earlier at a higher rate than participants in both FM groups.Citation63 This suggests that Fondo Maria’s services may meet a particular need among individuals seeking abortions, and may help people get the care they want when they want it. Further research should incorporate nuanced explorations of users’ experiences with accompaniment services to provide additional insights about their experiences.

Our study has a number of limitations. We are drawing conclusions from a relatively small sample. Additionally, the response rate for the midline survey was lower for the FM State group than for the FM Clinic group, and fairly low overall. As such, our sample may not be representative of all people who obtained support from Fondo Maria, particularly those who stayed in their home state or had lower educational attainment or were older. Likewise, the sociodemographic profile of included participants suggests that our sample may not be representative of all people in Mexico seeking abortions. Our sample also only includes women who were ultimately able to access abortion care. Our data do not account for the experiences of, or the barriers faced by, people living outside CDMX who needed abortions but were ultimately unable to obtain them.

Additionally, as previously discussed, we are limited in our ability to determine how and when certain factors influenced women’s decisions, and the role Fondo Maria played in mitigating the impact of some of those factors. Similarly, we cannot know if participants who got care when they wanted it were able to do so because of Fondo Maria’s services, or if participants who said their travel was easy would attribute the ease of their experience to Fondo Maria’s support. Further research is needed to explicitly explore abortion-seekers’ baseline needs and document the role that accompaniment networks like Fondo Maria play in meeting them. Despite these limitations, our findings provide novel insight into the experiences of women from restrictive contexts in Mexico who sought abortion with accompaniment support, and also uniquely allow us to consider the distinct experiences of those who travel for clinic-based care and those who self-manage locally.

Conclusion

Our research adds to a growing body of evidence on abortion accompaniment. Our data documents the contexts in which women sought care and the factors that influenced their decisions and experiences. The positive experiences participants had with Fondo Maria services suggest that the accompaniment model is well received by participants. These data will be instructive for accompaniment organisations who wish to support people in obtaining autonomous, person-centred abortion care.

Fondo Maria understands abortion accompaniment as having the potential to strengthen people’s ability to make decisions and exercise their reproductive rights. They centre the individual circumstances of each person seeking an abortion in their support services. In doing this work in this way, Fondo Maria and other accompaniment organisations connect individuals to safe care and important information and also contribute to a growing movement in abortion care that seeks to centre the needs and autonomy of people seeking care and provide services in empowering, supportive settings that meet people where they are. Such an approach has positive implications for the safety and accessibility of abortion services, and the experiences of those seeking care.Citation64,Citation65 Increasing the visibility and accessibility of accompaniment organisations like Fondo Maria may enable more people to access safe services in a timely manner, make choices based on individual preference, navigate financial and logistical burdens, and help even more people get the abortions they need. However, even with organisations like Fondo Maria, barriers remain for people seeking abortion care in Mexico. Looking forward, it is critical that the perspectives and needs of people seeking abortion guide efforts to implement the decriminalisation of abortion to ensure that existing barriers to care are addressed and compassionate, person-centred care is available to all people.

Author contributions

SG, OU, SB and BKO conceptualised and designed the study protocol and data collection instruments. SG, BKO, and CG were involved in data collection. AW and CG conducted data analysis. CG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version for journal submission.

Data availability statement

Due to our commitment to protect the confidentiality and anonymity of those requesting support from Fondo Maria, we cannot make the data used for this study available for download. We are happy to answer any inquiries related to the data used for the manuscript and provide additional information, where possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

* We acknowledge that not all people who seek and receive abortion care identify as women. However, much of the existing research we cite on this topic specifically refers to women, and our study utilised the word “women” in our recruitment process. To be both accurate and inclusive, we use the words “woman/women” and the pronouns “she/her” when discussing our own data as well as when citing studies that specified that they recruited women. We use the more gender-inclusive term “people” in all other instances.

† In this study, participants living “outside of CDMX” include all participants who live outside the administrative unit of Mexico City, including those who live in the State of Mexico and Morales.

References

- Becker D, Díaz Olavarrieta C. Decriminalization of abortion in Mexico City: the effects on women’s reproductive rights. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:590–593.

- Hidalgo becomes third Mexican state to allow abortion Reuters. [Cited 2 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/hidalgo-becomes-third-mexican-state-allow-abortion-2021-06-30/.

- Kitroeff N, Lopez O. Abortion is no longer a crime in Mexico. But will doctors object? The New York Times. 13 September 2021. [Cited 20 September 2021]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/13/world/americas/mexico-abortion-objectors.html.

- El aborto en los códigos penales. Gire. [Cited 20 September 2021]. Available from: https://gire.org.mx/plataforma/causales-de-aborto-en-codigos-penales/.

- Fact Sheet. Causales Legales Para El Aborto [Internet]. Ipas Mexico, 2019.

- Küng SA, Darney BG, Saavedra-Avendaño B, et al. Access to abortion under the heath exception: a comparative analysis in three countries. Reprod Health. 2018;15:107.

- Becker D, Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Juarez C, et al. Sociodemographic factors associated with obstacles to abortion care: findings from a survey of abortion patients in Mexico City. Womens Health Issues Off Publ Jacobs Inst Womens Health. 2011;21:S16–S20.

- Lamas M. Entre el estigma y la ley: la interrupción legal del embarazo en el DF. Salud Pública México. 2014;56:56–62.

- Krauss A. Luisa’s ghosts: haunted legality and collective expressions of pain. Med Anthropol. 2018;37:688–702.

- Sorhaindo AM, Juárez-Ramírez C, Olavarrieta CD, et al. Qualitative evidence on abortion stigma from Mexico City and five states in Mexico. Women Health. 2014;54:622–640.

- Narasimhan M, Logie CH, Gauntley A, et al. Self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights for advancing universal health coverage. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28:1778610.

- Drovetta RI. Safe abortion information hotlines: An effective strategy for increasing women’s access to safe abortions in Latin America. Reprod Health Matters. 2015;23:47–57.

- Gerdts C, Hudaya I. Quality of care in a safe-abortion hotline in Indonesia: beyond harm reduction. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:2071–2075.

- Erdman JN, Jelinska K, Yanow S. Understandings of self-managed abortion as health inequity, harm reduction and social change. Reprod Health Matters. 2018;26:13–19.

- Fondo MARIA. Fondo Maria. [Cited 23 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.fondomaria.org/.

- Centro Nacional de Equidad de Género y Salud Reproductiva. Técnico para la atención del Aborto Seguro en México. 14 June 2021.

- Miller S, Lehman T, Campbell M, et al. Misoprostol and declining abortion-related morbidity in Santo Domingo. Dominican Republic: a temporal association. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112:1291–1296.

- Zurbriggen R, Keefe-Oates B, Gerdts C. Accompaniment of second-trimester abortions: the model of the feminist Socorrista network of Argentina. Contraception. 2018;97:108–115.

- Lafaurie MM, Grossman D, Troncoso E, et al. Women’s perspectives on medical abortion in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru: a qualitative study. Reprod Health Matters. 2005;13:75–83.

- Dzuba IG, Winikoff B, Peña M. Medical abortion: a path to safe, high-quality abortion care in Latin America and the Caribbean. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2013;18:441–450.

- Gerdts C, Jayaweera RT, Baum SE, et al. Second-trimester medication abortion outside the clinic setting: an analysis of electronic client records from a safe abortion hotline in Indonesia. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2018;44:286–291.

- Zamberlin N, Romero M, Ramos S. Latin American women’s experiences with medical abortion in settings where abortion is legally restricted. Reprod Health. 2012;9:34.

- Upadhyay UD, Dworkin SL, Weitz TA, et al. Development and validation of a reproductive autonomy scale. Stud Fam Plann. 2014;45:19–41.

- Moseson H, Bullard KA, Cisternas C, et al. Effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion between 13 and 24 weeks gestation: a retrospective review of case records from accompaniment groups in Argentina, Chile, and Ecuador. Contraception.

- Grossman D, Baum SE, Andjelic D, et al. A harm-reduction model of abortion counseling about misoprostol use in Peru with telephone and in-person follow-up: a cohort study. PloS One; 13.

- Gerdts C, Jayaweera RT, Kristianingrum IA, et al. Effect of a smartphone intervention on self-managed medication abortion experiences among safe-abortion hotline clients in Indonesia: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;149:48–55.

- Jelinska K, Yanow S. Putting abortion pills into women’s hands: realizing the full potential of medical abortion. Contraception. 2018;97:86–89.

- De Zordo S, Zanini G, Mishtal J, et al. Gestational age limits for abortion and cross-border reproductive care in Europe: a mixed-methods study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol.

- Makleff S, Labandera A, Chiribao F, et al. Experience obtaining legal abortion in Uruguay: knowledge, attitudes, and stigma among abortion clients. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19:155.

- Cockrill K, Upadhyay UD, Turan J, et al. The stigma of having an abortion: development of a scale and characteristics of women experiencing abortion stigma. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2013;45:79–88.

- Foster DG, Jackson RA, Cosby K, et al. Predictors of delay in each step leading to an abortion. Contraception. 2008;77:289–293.

- Proyecciones de la Población 2010-2050. Consejo Nacional de Población CONAPO. [Cited 15 June 2018]. Available from: http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/proyecciones.

- Bercu C, Fillipa S, Ramirez AM, et al. Perspectives on interpersonal care among people who obtain abortions through clinical and accompaniment models in Argentina. Epub ahead of print 23 September 2021. DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-391415/v1.

- Tousaw E, Moo SNHG, Arnott G, et al. “It is just like having a period with back pain”: exploring women’s experiences with community-based distribution of misoprostol for early abortion on the Thailand–Burma border. Contraception. 2018;97:122–129.

- Brown RW, Jewell RT, Rous JJ. Provider availability, race, and abortion demand. South Econ J. 2001: 656–671.

- Aiken AR, Gomperts R, Trussell J. Experiences and characteristics of women seeking and completing at-home medical termination of pregnancy through online telemedicine in Ireland and Northern Ireland: a population-based analysis. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;124:1208–1215.

- Foster DG, Kimport K. Who seeks abortions at or after 20 weeks? Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2013;45:210–218.

- Grossman D, Garcia SG, Kingston J, et al. Mexican women seeking safe abortion services in San Diego, California. Health Care Women Int. 2012;33:1060–1069.

- Karasek D, Roberts SC, Weitz TA. Abortion patients’ experience and perceptions of waiting periods: survey evidence before Arizona’s two-visit 24-hour mandatory waiting period law. Womens Health Issues. 2016;26:60–66.

- Upadhyay UD, Weitz TA, Jones RK, et al. Denial of abortion because of provider gestational age limits in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1687–1694.

- Saavedra-Avendano B, Schiavon R, Sanhueza P, et al. Who presents past the gestational age limit for first trimester abortion in the public sector in Mexico City? PloS One. 2018;13:e0192547.

- Conti J, Cahill EP. Self-managed abortion. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;31:435–440.

- Ngo TD, Park MH, Shakur H, et al. Comparative effectiveness, safety and acceptability of medical abortion at home and in a clinic: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:360–370.

- Aiken AR, Digol I, Trussell J, et al. Self reported outcomes and adverse events after medical abortion through online telemedicine: population based study in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Br Med J; 357.

- Foster AM, Arnott G, Hobstetter M. Community-based distribution of misoprostol for early abortion: evaluation of a program along the Thailand–Burma border. Contraception. 2017;96:242–247.

- Keefe-Oates B, Makleff S, Sa E, et al. Experiences with abortion counselling in Mexico City and Colombia: addressing women’s fears and concerns. Cult Health Sex. 2020;22:413–428.

- Juarez F, Bankole A, Palma JL. Women’s abortion seeking behavior under restrictive abortion laws in Mexico. PLOS ONE. 2019;14:e0226522.

- Mexico to restrict mobility to areas less affected by virus. AP NEWS. [Cited 29 June 2021]. Available from: https://apnews.com/article/9e5bb61c8bb22aba3fe0557aa82f592e. 2020.

- Hanschmidt F, Linde K, Hilbert A, et al. Abortion stigma: a systematic review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48:169–177.

- McMurtrie SM, García SG, Wilson KS, et al. Public opinion about abortion-related stigma among Mexican Catholics and implications for unsafe abortion. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;118:S160–S166.

- Cockrill K, Nack A. “I’m not that type of person”: managing the stigma of having an abortion. Deviant Behav. 2013;34:973–990.

- Moseson H, Herold S, Filippa S, et al. Self-managed abortion: a systematic scoping review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;63:87–110.

- Aiken ARA, Starling JE, Gomperts R. Factors associated with use of an online telemedicine service to access self-managed medical abortion in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2111852.

- Aiken ARA, Broussard K, Johnson DM, et al. Motivations and experiences of people seeking medication abortion online in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2018;50:157–163.

- Senderowicz L, Sanhueza P, Langer A. Education, place of residence and utilization of legal abortion services in Mexico City, 2013–2015. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2018;44:43–50.

- Jacobson LE, Saavedra-Avendano B, Fuentes-Rivera E, et al. Travelling for abortion services in Mexico 2016–2019: community-level contexts of Mexico City public abortion clients. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. Epub ahead of print. 28 July 2021. DOI:10.1136/bmjsrh-2021-201079.

- Darney BG, Fuentes-Rivera E, Saavedra-Avendaño B, et al. Contraceptive receipt among first-trimester abortion clients and postpartum women in urban Mexico. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;46:35–43.

- Olavarrieta CD, Garcia SG, Arangure A, et al. Women’s experiences of and perspectives on abortion at public facilities in Mexico City three years following decriminalization. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;118:S15–S20.

- Becker D, Díaz-Olavarrieta C, Juárez C, et al. Clients’ perceptions of the quality of care in Mexico City’s public-sector legal abortion program. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;37:191.

- McLemore MR, Desai S, Freedman L, et al. Women know best – findings from a thematic analysis of 5,214 surveys of abortion care experience. Women39s Health Issues; 24:594–599.

- Taylor D, Postlethwaite D, Desai S, et al. Multiple determinants of the abortion care experience: from the patient’s perspective. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28:510–518.

- McLemore MR, Desai S, James EA, et al. Letter to the editor, re: article “factors influencing women’s satisfaction with surgical abortion” by Tilles, Denny, Cansino and Creinin. Contraception. 2016;93:372.

- Wollum A, Garnsey C, Baum S, et al. El acceso al aborto y su impacto en las nociones de estigma para las mujeres: evaluación del modelo de acompañamiento del Fondo de Aborto para Justicia Social. Ibis Reproductive Health. In Press.

- Sudhinaraset M, Afulani P, Diamond-Smith N, et al. Advancing a conceptual model to improve maternal health quality: the person-centered care framework for reproductive health equity. Gates Open Res; 1.

- Altshuler AL, Whaley NS. The patient perspective: perceptions of the quality of the abortion experience. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:407–413.