Abstract

Pandemic mitigation measures can have a negative impact on access and provision of essential healthcare services including sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. This rapid review looked at the literature on the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on SRH and gender-based violence (GBV) on women in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) using WHO rapid review guidance. We looked at relevant literature published in the English language from January 2020 to October 2021 from LMICs using WHO rapid review methods. A total of 114 articles were obtained from PubMed, Google Scholar and grey literature of which 20 met the eligible criteria. Our review found that there was an overall reduction in; (a) uptake of services as shown by lower antenatal, postnatal and family planning clinic attendance, (b) service delivery as shown by reduced health facility deliveries, and post abortion care services and (c) reproductive health outcomes as shown by an increase in incidence of GBV especially intimate partner violence. COVID-19 mitigation measures negatively impact SRH of women in LMICs. Findings from this review could inform policy makers in the health sector to recognise the potential adverse effects of COVID-19 responses on SRH in the country, and therefore implement mitigation measures.

Résumé

Les mesures d’atténuation des pandémies peuvent avoir des répercussions négatives sur l’accès aux services de santé essentiels et la prestation de ces soins, notamment en matière de santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR). Cet examen rapide a porté sur les publications relatives aux conséquences des mesures d’atténuation de la COVID-19 sur la SSR et les violences sexistes chez les femmes des pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire; il a été mené à l’aide du guide de l’OMS sur les examens rapides. Nous avons analysé les publications pertinentes parues en langue anglaise de janvier 2020 à octobre 2021 dans les pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire en utilisant les méthodes d’examen rapide de l’OMS. Au total, 114 articles ont été obtenus dans PubMed, Google Scholar et la littérature grise dont 20 réunissaient les critères de sélection. Notre examen a révélé une réduction d’ensemble: (a) du recours aux services ainsi que montré par une diminution de la fréquentation des centres de santé prénatale, postnatale et de planification familiale, (b) de la prestation des services ainsi que montré par la réduction des accouchements pratiqués dans les établissements de santé et des services de soins post-avortement, etc) de l’état de santé reproductive ainsi que montré par l’augmentation de l’incidence des violences sexistes et spécialement des violences infligées par un partenaire intime. Les mesures d’atténuation de la COVID-19 ont eu des conséquences négatives sur la santé sexuelle et reproductive des femmes vivant dans des pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire. Les résultats de cet examen pourraient informer les décideurs du secteur de la santé des effets néfastes des ripostes à la COVID-19 sur la SSR dans leur pays et par conséquent les aider à prendre des mesures susceptibles de les atténuer.

Resumen

Las medidas para mitigar la pandemia pueden tener un impacto negativo en la accesibilidad y prestación de servicios de salud esenciales, incluidos los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR). Esta revisión rápida examinó la literatura sobre el impacto de las medidas de mitigación de COVID-19 en SSR y violencia de género (VG) en mujeres en países de bajos y medianos ingresos (PBMI) utilizando la guía de revisión rápida de la OMS. Estudiamos la literatura pertinente publicada en inglés entre enero de 2020 y octubre de 2021 de PBMI que utilizan los métodos de revisión rápida de la OMS. Obtuvimos un total de 114 artículos de PubMed, Google Scholar y la literatura gris, de los cuales 20 reunían los criterios elegibles. Nuestra revisión encontró que hubo una reducción general en; (a) la aceptación de servicios, mostrada por una asistencia reducida a clínicas de atención prenatal, posnatal y de planificación familiar, (b) la prestación de servicios, mostrada por el número reducido de partos en establecimientos de salud y servicios de atención postaborto y (c) los resultados de salud reproductiva, como muestra el aumento en la incidencia de violencia de género, especialmente la violencia de pareja íntima. Las medidas de mitigación de COVID-19 tienen un impacto negativo en la salud sexual y reproductiva de las mujeres en PBMI. Los hallazgos de esta revisión podrían informar a formuladores de políticas en el sector salud para que reconozcan los posibles efectos adversos de las respuestas a COVID-19 en SSR en el país, y por tanto apliquen medidas de mitigación.

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic and countries around the world responded by instituting various mitigation measures such as nationwide curfews and lockdown, social distancing, closure of institutions such as schools and worship areas, respiratory etiquette, hand hygiene, and modifications of public transport use, among others. These measures were put in place quickly to protect health and health services from being overwhelmed (“flattening the curve”) but they had indirect and unintended effects too, leading to the creation of essential care packages, online and outreach services to ensure a minimum was accessible to those in need.

However, these measures can negatively impact on access to and provision of essential health care services, especially sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. These services include maternal and child health care, family planning, post abortion care (PAC) and gender-based violence (GBV) and recovery services. In addition, SRH is often an indirect victim of pandemics as healthcare services and resources are redirected towards handling the direct effects of the pandemic.Citation1 Evidence of this has been seen during the Ebola virus outbreak in 2013–2016 in West Africa.Citation2 Riley et al (2020) estimated the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SRH in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and projected that a disruption in essential primary health care would lead to a 10% decline in use of contraceptives and maternity service coverage, and a 10% shift in abortions from safe to unsafe.Citation3 Isolation, lockdown and stay-at-home orders also result in increased GBV.Citation1 This was thought to be due to loss of income, closure of businesses, overall financial hardship leading to GBV.

Whereas most studies have been conducted in high-income countries (HICs), this rapid review discusses the current literature on the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on SRH of women of reproductive age in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with a view to informing policy and practice for better preparedness in future. LMICs differ significantly from HICs in terms of the structure and organisation of healthcare services, capacity of the authorities to effectively respond and ensure effective mitigation measures, the socio-economic status of the population and their health-seeking behaviour. This makes them more vulnerable to health crises, particularly SRH crises. This rapid review will help inform policies on mitigation measures employed to ensure SRH care is not neglected in future, to help any vulnerable groups and improve equity.

Materials and methods

This rapid review assessed the literature on the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on SRH in women of reproductive age in LMICs published in English between January 2020 and October 2021. This included uptake and access to healthcare services, availability of these services and whether there was a change in the number of women affected by GBV. Rapid reviews provide more timely information for decision making which is helpful for policymakers who require a short deadline for synthesising data. This review was done to inform a larger study commissioned by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

Literature search, data extraction, analysis and synthesis

For this rapid review, we used best practice methods recommended by the World Health Organisation.Citation4,Citation5 This involved identifying a clear research question and objective (what is the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on SRH among women of reproductive age in LMICs?), identifying relevant articles, selection of articles, data extraction, charting, organising, summarising, analysing and reporting of data. The research question included the impact on groups, access to and uptake of services, and service activity and outcomes.

The literature searched was from PubMed and Google Scholar, published in the English language between January 2020 and October 2021. Medical subject headings (MeSH) were searched using Boolean operators “OR/AND”. The search terms used were: (“women” OR “females” OR “adolescents” OR “young”) AND (“covid” OR “covid-19” OR “coronavirus”) AND (“sexual health” OR “reproductive health” OR “contraception” OR “family planning” OR “antenatal” OR “postnatal” OR “prenatal” OR “postpartum” OR “abortion” OR “rape” OR “genital mutilation” OR “harmful practices” OR “gender-based violence” OR “domestic violence” OR “sexual abuse” OR “health-seeking behaviour” OR “youth friendly services” OR “labour” OR “delivery” OR “intimate partner violence”) AND (“low and middle-income countries” OR “developing countries” OR “LMIC” OR “rural” OR “resource-limited”) AND (“lockdown” OR “mitigation” OR “prevention” OR “isolation” OR “restrictions” OR “shutdown”). Hand searching and exploration of grey literature including editorial opinions and news articles were also conducted.

Inclusion criteria

We included literature that interrogated the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on SRH of women of reproductive age, in LMIC, published in the English language from January 2020 to October 2021. This included quantitative and qualitative literature.

Exclusion criteria

Most of the remaining articles and literature were excluded because they assessed the direct impact of COVID-19 on SRH and not mitigation measures. Other articles looked at the effect of mitigation measures on vulnerable populations but not related to SRH.

Quality appraisal method/risk of bias assessment

Screening of abstracts was done by a single reviewer, with full-text screening, data abstraction and quality appraisal done by a single reviewer with verification by a second.

This was assessed by looking at the quality of evidence applied to the outcome of each study. The GRADE method could not be employed in this review as there was a mix of quantitative and qualitative studies, making it difficult to look at and compare the risk of bias and imprecision of studies. The evidence-based medicine pyramid was used, looking at hierarchy of studies with randomised controlled trials considered high quality and case series considered low quality.Citation6 This is summarised in .

Table 1. Summary of the impact of mitigation measures on different aspects of SRH.

Results

Study characteristics

The literature search found publications on access and uptake of services, service delivery, groups affected and outcomes.

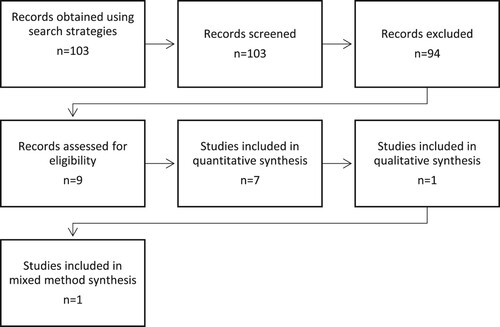

A total of 114 articles were obtained from PubMed (79), Google Scholar (31) and grey literature (4). Those eligible from these were 11 articles from PubMed, seven from Google Scholar and two articles from grey literature. shows the search and selection process of the relevant literature. Most of the remaining articles and literature were excluded because they assessed the direct impact of COVID-19 on SRH and not the mitigation measures themselves. This included avoidance of healthcare facilities due to fear of infection, or the effect of the infection itself on women of reproductive age. Other studies assessed the impact of mitigation measures on other vulnerable populations in LMICs such as migrants, students and rural settlement areas but unrelated to SRH.

Research domains

Among the 20 studies included in this review, 11 studies explored the impact on family planning, postnatal care and abortion care services; five looked at the impact on GBV; eight explored the impact on antenatal care and facility deliveries, and two assessed the impact on birth outcomes. In terms of study design, two were interrupted time series analyses, 11 were cross-sectional studies, two were qualitative studies based on interviews, two were systematic reviews of literature and news, two made estimations based on existing official data and the remaining one was a comparative case study. These findings are summarised in greater detail in .

Antenatal care and deliveries at health facilities

A qualitative study using telephone interviews conducted in Embakasi, Kenya, with women who received services for childbirth in any healthcare facility, (public, private or non-governmental), showed reduced access to both outpatient and inpatient services between May and June 2020.Citation6 This was a result of lockdown which resulted in income reduction thus rendering the women unable to afford health care. Another cross-sectional study conducted in Kenya comparing the attendance for RMNCAH (Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health) services over a 4-month period in 2019 (pre-COVID period of March–June) to (March 2020–June 2020), showed disrupted access to antenatal and skilled birth services due to interrupted transport and support systems as a result of dawn-to-dusk curfews and lockdown.Citation7 In 2019, 298,211 pregnant women completed the minimum four antenatal visits compared to 261,444 women in 2020. Similarly, a study in Nigeria found that among 1241 women of reproductive age, 32% reported challenges in access to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (RMNCH) services due to the lockdown order and unavailability of transport (18%).Citation8

In Southwest Ethiopia, Kassie et al. (2021) found that the mean utilisation of antenatal care decreased by 27.4% comparing March–June 2019 (943.25 visits) with the same period in 2020 (694.75 visits)Citation9 mainly due to lockdown and travel restrictions. Another qualitative study examining maternal and neonatal health (MNH) care services at 17 facilities involving 68 indigenous communities in remote Peruvian Amazon between March and May 2020 revealed restricted access to routine MNH care due to community isolation.Citation10 An analysis of focus group discussions with pregnant women in Southwest Ethiopia found that the primary reason for not attending antenatal care is the perception of poor quality of care during the pandemic.Citation11 This was due to the temporary reallocation of health workers from reproductive health services to COVID-related work stations. Overall, an analysis of eight sub-Saharan African countries found significant declines in antenatal care in seven though they were context-specific with five seeing declines in deliveries.Citation12

With the unmet need for family planning services, the number of unintended pregnancies also increased. A cross-sectional study in Ethiopia found that 47% of women (n = 424) attending antenatal care experienced unintended pregnancies from November 2020 to December 2020.Citation13 Stay-at-home orders were seen to have played a role in these findings.Citation14.

Due to a similar COVID-19 mitigation strategy, a comparative case study conducted in a tertiary facility in Ethiopia found that the number of hospital deliveries from March to May 2020 was 1970 as compared to 2720 deliveries over the same period in 2019, showing a reduction of 27.6%.Citation14 The cross-sectional study in Southwest Ethiopia also found a decrease in facility deliveries of 23.5% during March-June 2020.Citation10 However, in-depth analysis on specific maternal sociodemographic differences was not reported.

Family planning and postnatal services

Overall, the studies demonstrated a decrease in uptake of Family Planning (FP). Additional results from the Belay et al. (2020) study conducted in Ethiopia, comparing March–May 2019 to the same period in 2020, showed a 27.3% reduction in the uptake of interval FP (from 368 to 268 clients); a 40.6% reduction in the uptake of FP after safe abortion care provided at the facility (from 318 to 189 clients); a 39.7% reduction in FP provision to clients who presented for post-abortion care (275 clients between March–May 2020 compared to 456 clients for the same period in 2019); and a 66.7% reduction in uptake of FP among immediate post-partum women (from 609 to 203 clients).Citation14 This was due to nationwide travel restrictions imposed in that period. Another study conducted in Southwest Ethiopia also found a consistent decline in utilisation of family planning of 16%.Citation10 An analysis of interviews with staff from 307 primary health centres in Nigeria by Adelekan et al (2021) also suggested a decline in offering family planning services (from 97.7% to 95.8%) during the lockdown and 92.5% after lockdown.Citation15 A study of sex workers in Kenya employing qualitative methodologies revealed a disruption of supply of family planning commodities and lack of transport to access FP clinics.Citation16 Another cross-sectional study on refugees in Jordan showed an overall 10–20% increase in women who were unable to access FP services, with variation among the different age groups.Citation17 Before the lockdown, 61% of women aged 25–29 years always had access to FP services and counselling, as compared to 15% after the lockdown. These figures were 24% and 17%, respectively, for girls aged 10–17 years. A UNFPA report based on global data suggested that 41% of countries (n = 30) reported disrupted services in family planning, which is expected to result in 1.4 million unintended pregnancies across 115 Low/Middle-Income Countries.Citation18 However, an interrupted time series study in rural South Africa showed no difference in FP visits before (February–March 2020) and after the lockdown (the month of April 2020).Citation19

Abortion care

Results from the study in Ethiopia by Belay (2020) showed a 16.4% reduction in attendance at safe abortion care (SAC)Citation14 after travel restrictions were imposed. Only 270 clients accessed SAC care in March–May 2020 compared to 323 during the same period in 2019. Similarly, a reduction of 20.3% was seen among clients attending post-abortion care (PAC) services with 404 patients between March–May 2020 compared to 507 patients over the same period in 2019. In Nepal, 47% fewer women visited safe abortion services during the lockdown than after the lifting of the order (18 vs 34).Citation20 An in-depth review with public health experts in Pakistan revealed that the disruption of safe abortion care would lead to an increase in unsafe abortionsCitation21 due to lockdown as a COVID-19 mitigation strategy.

Adolescent reproductive health

After lockdown measures and subsequent closure of schools, results from a study by Shikuku et al (2020) in an urban informal setting in Kenya showed an increasing trend in the proportion of adolescent pregnancies from 7.0 to 7.6 between March and June 2020, as compared to a relatively steady trend from 8.8 to 8.9 in 2019.Citation7 There was an increase in adolescent maternal deaths (6.2–10.9%), increased uptake of FP (127,684 in 2019 compared to 133,173 in 2020) and reduced uptake of PAC services by adolescents (2793 in 2019 compared to 2464 in 2020). Similar patterns were also found in Southwest Ethiopia, with an increase in teenage pregnancy rate (7.5–13.1%) and adolescent abortion care (21.3–28.5%) during the specific time between March and June 2020.Citation10 This was attributed to the reallocation of staff from reproductive health services.

Gender-based violence

An interrupted time series analysis of 3000 mothers in Bangladesh showed that 2174 (72.46%) experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) in life.Citation22 During the lockdown, 68.4% reported an increase in insults, 66.0% reported an increase in humiliation, 68.7% reported an increase in intimidation, 56.0% reported an increase in physical violence such as being slapped or having something thrown at them, and 50.8% reported an increase in sexual violence. The study conducted by Plan International in Jordan showed that of the 397 women surveyed, 69% experienced an increase in emotional and physical violenceCitation17 after movement restrictions were imposed. The most prevalent form of violence among women aged 18–49 years was emotional (73%), followed by physical violence at 54%. Other forms of violence included sexual harassment (17%), cyberbullying (18%), sexual violence (14%) and rape (8%). Similar results were noted among girls aged 10–17 years.

A review of newspapers from India suggested that lockdown increased the exposure to domestic violence for women, and there was a lack of socio-legal support.Citation23 Examining peer-reviewed journals and grey literature in Nigeria, Allen (2021) also noted increased numbers of rapes, GBV, and domestic violence, which contributed to unintended pregnancies and increased demand for abortion.Citation24 In addition, general violence against women was found to be increasing in Pakistan as an indirect impact of the pandemicCitation21 due to lockdown and reduced access to healthcare services.

Birth outcomes

The study by Shikuku et al (2020) in Kenya demonstrated a significant increase in fresh stillbirths (those that happen shortly before labour) over the 4-month period of April 2020 to July 2020 (0.9%–1.0%)Citation7 after lockdown measures were imposed. In contrast, a modest reduction in adverse birth outcomes was seen in a cross-sectional quantitative comparison study using data from an ongoing nationwide birth outcomes surveillance study to evaluate adverse outcomes (stillbirth, preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age foetuses, and neonatal death) in Botswana.Citation25 The study recorded findings for pre-lockdown (1 January 2020–2 April 2020), during lockdown (3 April 2020–7 May 2020), and post-lockdown (8 May 2020–20 July 2020) periods. It then compared the net change in each outcome from the pre-lockdown to lockdown periods in 2020 compared to the same two periods in 2017–2019 and similarly for the pre-lockdown to post-lockdown periods in 2020. The lockdown period was associated with a 0.81% reduction (95% CI, −2.95% to 1.30%) in the risk of any adverse outcome (3% relative reduction). The post-lockdown period was associated with a 1.72% point reduction (95% CI, −3.42% to 0.02%) in the risk of any adverse outcome (5% relative reduction). Reductions in adverse outcomes were largest among women with HIV and among women delivering at urban delivery sites, mainly due to reductions in preterm birth and small-for-gestational-age.

The Kassie et al. (2021) study in Southwest Ethiopia also found a 7.8% increase in stillbirth (14–21.8%) and a 13% increase in neonatal death (33.1–46.2%) during the period between March to June 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.Citation10 This was after the travel restrictions occurred in the region.

Discussion

Most of the papers included in this review suggest an overall disruption in access to and provision of SRH services, and a negative impact on the well-being of women of reproductive age due to COVID-19 mitigation measures.

Health facility deliveries were reduced due to travel restrictions, forcing pregnant women to give birth at home.Citation14 Loss of income and employment opportunities due to lockdown led to the inability to afford cost of health care and hence reduced access. De-prioritisation of services in an attempt to mitigate the pandemic also led to reduced access to maternal healthcare services.Citation15,Citation26 Entry restrictions among communities limited access to maternal healthcare services to women of the same community, therefore restricting access to women from neighbouring communities. Community isolation, lack of public transport also discouraged facility births and early care seeking for obstetric emergencies.Citation8,Citation9 This could have led to an increase in preventable maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality among women of child-bearing age, as demonstrated by a Kenyan study which showed increased fresh stillbirths and adolescent maternal deaths. Dawn-to-dusk curfews, fear of police enforcers of the curfews and lockdowns led to possible delays in accessing skilled health services, further complicating pregnancies, which could have contributed to the rise in stillbirths. Falling standards of quality of care for labour and childbirth during the pandemic was also thought to have contributed to an increase in adverse birth outcomes.Citation7

However, this was contradicted by a study in Botswana which, though having fewer women reporting at facilities, showed a reduction in adverse outcomes especially among women delivering at urban delivery sites, women with HIV and women with salaried employment, suggesting that the lockdown could have impacted the daily lives of these women to a larger extent, unlike their rural counterparts. It was suggested that the shelter-in-place order led to more people staying put, which could have reduced physical labour, exposure to infections and air pollution and other sources of stress. The same order may have increased stress, anxiety and undernutrition, especially among those who were food-insecure and economically disadvantaged in rural areas.Citation25 A review of rates of preterm birth during lockdown, that examined 11 studies, mostly from HICs, showed inconsistent results where some studies showed a significant reduction in preterm birth while others showed no difference. The studies had several methodological differences – inconsistently-defined outcomes, different lockdown periods, different lengths of study, among others – and hence it may be too soon to conclude the effect of the lockdown on preterm birth.Citation7

Movement restrictions also led to difficulty in access to family planning services. Social distancing measures imposed by healthcare facilities led to an increase in waiting time and delay in access to FP services, causing inconvenience and resultant decrease in uptake of the same. A disruption in supply of FP commodities due to the lockdown also resulted in shortage of some FP methods. Kumar et al (2020) also observed that closure of large pharmaceutical companies that usually supply low- and middle-income countries led to disruption of production and supply of FP products.Citation27 This could have led to an increase in unmet need for contraception and millions of unplanned pregnancies. Conversely, in areas with unrestricted access to reproductive health services, an increase in uptake of FP among adolescents was seen, and thought to be due to closure of schools.Citation7 Similarly, no difference in attendance at postnatal clinics and family planning visits was seen when these services were considered to be part of essential primary healthcare services i.e. uninterrupted by mitigation measures.Citation28

The literature in this rapid review did not explain how mitigation measures led to a reduction in attendance of post-abortion care services but travel restrictions and lockdown measures were likely culprits. Lack of access to appropriate abortion care services could lead to increased morbidity and mortality because of complications from lack of or inadequate care and counselling.

Adolescents appear to be a vulnerable group with a higher maternal death rate and access to abortion care. The findings suggestive of an increase in teenage pregnancy from early on in the pandemic may in part reflect conceptions from the pre-pandemic so more insight is needed here.

The increase in GBV was mainly due to the economic situation, lack of privacy, movement restriction and crowding at home. Precipitating factors for the perpetrators of GBV were stress of losing work and income because of lockdown on business. The impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) cases was noted in the media in general and in Kenya a study evidenced this, showing an increase in reports of SGBV with the lockdown (including closure of schools and confinement to the home) and the economic repercussions of the mitigation measures most frequently reported as the causes.Citation20, Citation24

This rapid review has shown that mitigation measures during pandemics can negatively affect the SRH of women and girls, especially stay-at-home orders. SRH services should remain accessible to women even during lockdown. This can be achieved through 24-hour availability of emergency helplines and shelters for victims of violence and rape, emergency ambulance services for pregnant women in labour or other pregnancy-related complications, anticipatory stockpiling of contraceptives and virtual counselling for family planning to minimise delays in access to care.

Of the measures looked at, lockdown was the most common one which had significantly associated reductions in hospital deliveries, attendance of family planning and safe abortion services and postpartum clinic attendance. It also had an indirect impact as it caused a negative economic effect which in turn led to the inability of patients to afford healthcare and thus reduced access to services. Another negative economic effect was seen in the populations where IPV was reported to have increased substantially. In general, the use of health impact assessments of any proposed policy relating to mitigation should be done to try and pre-empt and mitigate unintended effects.

The nearly one-year time period that these studies cover provides a chance to see how dynamic and resilient services were in responding to the pandemic. However, in the main, it has been difficult to do so as the studies have a lag in getting published. That said the UNFPA Technical Note reported smaller and shorter impacts in family planning services than expected. Further work including qualitative studies will shed more light on this aspect. This being a rapid review, the available literature had significant methodological differences and hence the impact on birth outcomes was inconclusive, and there is a need for further research in this area.

Strengths and limitations

This rapid review examined the impact of mitigation measures on SRH of women of reproductive age in LMIC. The review looked at English language publications so may have missed studies in other languages. The studies obtained had variable methods which likely reflected the need for convenient and quick study designs albeit lower in the evidence hierarchy. The appraisal done was limited to study design and its place in the evidence hierarchy rather than formal use of critical appraisal tools but the WHO rapid review methods acknowledge that the need for speed may necessitate this. This also may have meant that more detailed analysis, e.g. of subgroups, was limited though adolescents and female sex workers were looked at. Whilst this review covered a diverse group of countries, which may limit generalisability, there was some consistency in the findings. Future work could use formal severity of COVID-19 mitigation measures to more closely compare countries.

Conclusion

COVID-19 mitigation measures have mostly had a negative impact on the SRH of women by restricting movement including stay-at-home orders and limiting access to care, with lockdowns appearing to have the most impact. This will help to identify those particularly at risk and therefore reduce effects and inequalities among women of reproductive age.

Author contributions

AM, MT and FO conceived and designed the study. MA, EO and PS conducted the literature search, reviewed the articles, extracted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and edited the subsequent drafts of the manuscript and approved the final submission. MT is the guarantor.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank UNFPA for the opportunity to do this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Tang K, Gaoshan J, Ahonsi B, et al. Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH): a key issue in the emergency response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Outbreak. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):59. doi:10.1186/s12978-020-0900-9.

- Sochas L, Channon AA, Nam S. Counting indirect crisis-related deaths in the context of a low-resilience health system: the case of maternal and neonatal health during the ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(suppl_3):iii32–iii39. doi:10.1093/heapol/czx108.

- Riley T, Sully E, Ahmed Z, et al. Estimates of the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;46:73–76. doi:10.1363/46e9020.

- Langlois EV, Straus SE, Antony J, et al. Using rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems and progress towards universal health coverage. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(1):e001178. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001178.

- Tricco AC, Langlois EV, Straus SE, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research & World Health Organization. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Sackett DL, Strauss SE, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

- Oluoch-Aridi J, Chelagat T, Nyikuri MM, et al. COVID-19 effect on access to maternal health services in Kenya. Front Glob Womens Health. 2020: 599267. doi:10.3389/fgwh.2020.599267.

- Shikuku D, Nyaoke I, Gichuru S, et al. Early indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilization and outcomes of reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health services in Kenya. MedRxiv. September 9, 2020: 2020.09.09.20191247. doi:10.1101/2020.09.09.20191247.

- Balogun M, Banke-Thomas A, Sekoni A, et al. Challenges in access and satisfaction with reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services in Nigeria during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. PloS One. 2021;16(5):e0251382. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0251382.

- Reinders S, Alva A, Huicho L, et al. Indigenous communities’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and consequences for maternal and neonatal health in remote Peruvian Amazon: a qualitative study based on routine programme supervision. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e044197. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044197.

- Kassie A, Wale A, Yismaw W. Impact of coronavirus diseases-2019 (COVID-19) on utilization and outcome of reproductive, maternal, and newborn health services at governmental health facilities in south west Ethiopia, 2020: comparative cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Health. 2021;13:479–488. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S309096.

- Hailemariam S, Agegnehu W, Derese M. Exploring COVID-19 related factors influencing antenatal care services uptake: a qualitative study among women in a rural community in southwest Ethiopia. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:2150132721996892. doi:10.1177/2150132721996892.

- Shapira G, Ahmed T, Drouard SHP, et al. Disruptions in maternal and child health service utilization during COVID-19: analysis from eight Sub-saharan African countries. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36(7):1140–1151. doi:10.1093/heapol/czab064.

- Hunie Asratie M. Unintended pregnancy during COVID-19 pandemic among women attending antenatal care in northwest Ethiopia: magnitude and associated factors. Int J Womens Health. 2021;13:461–466. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S304540.

- Tolu LB, Hurisa T, Abas F, et al. Effect of covid-19 pandemic on safe abortion and contraceptive services and mitigation measures: a case study from a tertiary facility in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Reprod Health. 2020;12(3):6–6.

- Adelekan B, Goldson E, Abubakar Z, et al. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on provision of sexual and reproductive health services in primary health facilities in Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):166. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01217-5.

- Gichuna S, Hassan R, Sanders T, et al. Access to healthcare in a time of COVID-19: sex workers in crisis in Nairobi, Kenya. Glob Public Health. 2020;15(10):1430–1442. doi:10.1080/17441692.2020.1810298.

- Daring to ask, listen and act: a snapshot of the impacts of COVID on women’s and girl’s rights and sexual and reproductive health. UNFPA Jordan. [cited 2021-12-27]. https://jordan.unfpa.org/en/resources/daring-ask-listen-and-act-snapshot-impacts-covid-womens-and-girls-rights-and-sexual-and.

- Impact of COVID-19 on family planning: what we know one year into the pandemic | United Nations Population Fund. [cited 2021-12-27]. https://www.unfpa.org/resources/impact-covid-19-family-planning-what-we-know-one-year-pandemic.

- Siedner MJ, Kraemer JD, Meyer MJ, et al. Access to primary healthcare during lockdown measures for COVID-19 in rural South Africa: an interrupted time series analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e043763. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043763.

- Aryal S, Nepal S, Ballav Pant S. Safe abortion services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study from a tertiary center in Nepal. F1000Res. 2021;10:112. doi:10.12688/f1000research.50977.1.

- Shah N, Musharraf M, Khan F, et al. Exploring reproductive health impact of COVID 19 pandemic: in depth interviews with key stakeholders in Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2021;37(4):1069–1074. doi:10.12669/pjms.37.4.3877.

- Hamadani JD, Hasan MI, Baldi AJ, et al. Immediate impact of stay-at-home orders to control COVID-19 transmission on socioeconomic conditions, food insecurity, mental health, and intimate partner violence in Bangladeshi women and their families: an interrupted time series. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(11):e1380–e1389. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30366-1.

- Maji S, Bansod S, Singh T. Domestic violence during COVID-19 pandemic: the case for Indian women. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2021. doi:10.1002/casp.2501.

- Allen F. COVID-19 and sexual and reproductive health of women and girls in Nigeria. Cosmop Civ Soc Interdiscip J. 2021;13(2). doi:10.5130/ccs.v13.i2.7549.

- Caniglia EC, Magosi LE, Zash R, et al. Modest reduction in adverse birth outcomes following the COVID-19 lockdown. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(6):615.e1–615.e12. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.12.1198.

- Goldenberg RL, McClure EM. Have coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) community lockdowns reduced preterm birth rates? Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(3):399–402. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004302.

- Kumar N. COVID 19 Era: a beginning of upsurge in unwanted pregnancies, unmet need for contraception and other women related issues. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care Off J Eur Soc Contracept. 2020;25(4):323–325. doi:10.1080/13625187.2020.1777398.